Abstract

This paper presents a reduced-order Legendre–Galerkin extrapolation (ROLGE) method combined with the scalar auxiliary variable (SAV) approach (ROLGE-SAV) to numerically solve the time-fractional Allen–Cahn equation (tFAC). First, the nonlinear term is linearized via the SAV method, and the linearized system derived from this SAV-based linearization is time-discretized using the shifted fractional trapezoidal rule (SFTR), resulting in a semi-discrete unconditionally stable scheme (SFTR-SAV). The scheme is then fully discretized by incorporating Legendre–Galerkin (LG) spatial discretization. To enhance computational efficiency, a proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) basis is constructed from a small set of snapshots of the fully discrete solutions on an initial short time interval. A reduced-order LG extrapolation SFTR-SAV model (ROLGE-SFTR-SAV) is then implemented over a subsequent extended time interval, thereby avoiding redundant computations. Theoretical analysis establishes the stability of the reduced-order scheme and provides its error estimates. Numerical experiments validate the effectiveness of the proposed method and the correctness of the theoretical results.

1. Introduction

The Allen–Cahn (AC) equation stands as one of the core phase-field models for describing phenomena such as phase separation and interface evolution, and it finds extensive applications in fields such as materials science, fluid mechanics, and biological modeling. It is essentially a gradient flow driven by a double-well potential and nonlinear terms. In the AC equation, replacing the first-order time derivative with a fractional derivative (such as the Caputo or Riemann–Liouville derivative) leverages the memory (non-locality) and heredity properties inherent to fractional derivatives, which enable the description of physical processes characterized by anomalous diffusion, memory effects, and viscoelasticity, for example, in describing more complex phase separation dynamics and interface roughening in certain polymer materials [1,2], amorphous materials [3], and porous media [4,5], and in characterizing the viscoelastic interface behaviors in some non-Newtonian fluids [6,7]. In this work, we are interested in the tFAC equation [8]

where and the Caputo derivative is defined by

with denoting the Gamma function. Here, the constant represents the interfacial thickness, represents the nonlinear bulk force. It is well-known that this problem satisfies the following energy law:

where

The tFAC equation has attracted extensive research in both theoretical and numerical fields, and numerous methods have been proposed for its numerical solution. The main concerns in designing numerical methods are computational complexity and stability. Currently, a great deal of research effort has been devoted to the development of stable, low-cost, and efficient time-stepping schemes. Broadly, the existing numerical techniques can be categorized into fully implicit methods [9,10], semi-implicit methods [11,12,13], stabilized linearly implicit methods [14], exponential time discretization methods [15], and SAV methods [16,17,18].

To linearize the nonlinear terms, Jie Shen proposed the SAV approach for gradient flows in [19]. In [8], by introducing some auxiliary constants and variables, the energy functional (3) is reformulated into the following form

where is a constant. The SAV method is a powerful tool for handling nonlinear terms in gradient flows and ensuring unconditional energy stability, which has achieved great success in integer-order equations. In recent years, the SAV framework has been systematically extended to the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Ref. [16] proposes a high-order and efficient scheme for the time-fractional AC equation, which is based on the L1 discretization method for the time-fractional derivative and the SAV method. This scheme is more robust than existing methods, and its efficiency is not restricted by the specific form of the nonlinear potential. In [17], the authors consider a class of time-fractional phase-field models including the AC equation and the Cahn–Hilliard (CH) equation. Based on the exponential scalar auxiliary variable (ESAV) approach, two explicit time-stepping schemes are constructed, where the fractional derivatives are discretized via the and formulas, respectively. Finally, the accuracy and efficiency of the proposed methods are verified through several numerical experiments. For the numerical solution of time-fractional phase-field models, a second-order numerical scheme is proposed in [18]. This scheme employs the fractional backward difference formula to approximate the time-fractional derivative and utilizes the extended SAV method to handle the nonlinear terms therein. The authors have proven that this numerical scheme possesses the energy dissipation property, and the relevant discussion covers the time-fractional AC equation, time-fractional CH equation, and time-fractional molecular beam epitaxy model. Similarly, we can linearize Equation (1) using the SAV method. It is straightforward to verify that the reformulated free energy (4) is mathematically equivalent to the original definition (3) for any constant a. The gradient flow corresponding to the free energy (4), along with the equation for the auxiliary function, is expressed as

with

and the initial conditions

Thus, problem (5) constitutes a reformulation of (1) and is mathematically equivalent to it. We will work with this reformulated system (5) because it facilitates the derivation of an unconditionally energy-stable and computationally efficient scheme.

Although the SAV method successfully converts nonlinear terms into a linear system, the discretization of tFAC remains an independent and critical challenge, whose difficulty is not eliminated by the application of the SAV method. To discretize the resulting linearized system (5), we adopt the fractional trapezoidal rule with a special shift (SFTR ) (i.e., SFTR with the shift parameter as ) scheme [20,21,22] in the temporal direction to handle the fractional derivative, thereby obtaining the SFTR-SAV formulation. This SFTR-SAV discretization scheme not only has unconditional stability but, more importantly, its mathematical structure facilitates the subsequent rigorous error analysis. Among them, SFTR can effectively deal with the nonlocal historical dependence caused by the time-fractional derivative, while ensuring that the discrete scheme can preserve the energy decay law and maximum principle of the original problem during long-time integration. In [20], the authors propose a second-order accurate formula for the SFTR, reveal its unique characteristics that most other second-order formulas do not possess, and finally investigate high-order methods on uniform grids that can simultaneously preserve the two intrinsic properties of the tFAC equation, namely energy decay and the maximum principle. Spatially, the tFAC equation can become highly stiff due to the small interfacial parameter and the nonlinearity, leading to extremely high computational costs, particularly in high dimensions. To overcome this challenge and significantly enhance computational efficiency, the reduced-order method (ROM) can be adopted. Its goal is to reduce the total number of unknowns in the temporal-spatial discretization of the tFAC equation while ensuring theoretical accuracy. The motivation for this study stems from the success of ROMs as powerful tools for numerical simulation in modern engineering [23,24,25,26,27,28]. It is particularly worth noting that this method entails redundant computations, as it constructs a POD basis from classical approximate solutions across the entire time interval and subsequently performs iterative calculations to obtain reduced-order approximate solutions over the very same interval . To reduce redundant computations and save storage space, thereby further improving computational efficiency, Luo and colleagues proposed the reduced-order extrapolation (ROE) method based on POD.

Since 2013, Luo and colleagues proposed a series of ROE methods based on POD numerical methods, including ROE finite element method, ROE finite difference method, ROE finite volume element method, and ROE natural boundary element method. These methods effectively reduce the computational load by eliminating redundancy while preserving the properties of the original solution space, and have been successfully applied to solve various partial differential equations such as parabolic equation [29], Stokes equation [30], heat equations [31], viscoelastic wave equations [32,33], hyperbolic equations [34,35], Sobolev equations [36], Boussinesq equations [37], and Navier–Stokes equations [38]. The core idea is to construct a POD basis using the classical solutions from a short initial time interval (with ), and then compute the ROE solution on the remaining interval , thereby eliminating redundant computations.

The numerical solution of the tFAC equation poses multiple challenges: the inherent nonlocality of fractional derivatives leads to high storage and computational complexity; the nonlinear double-well potential term induces strong nonlinear coupling; the initial weak singularity of the solution impairs numerical accuracy; and the phase separation interface requires high spatial resolution. All these factors result in extremely high computational costs for simulating the full-order model. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has investigated the application of the POD-based ROE method to the tFAC equation.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this work makes the following key contributions:

- We propose, for the first time, a ROLGE-SAV method for the tFAC equation. The framework integrates:

- –

- The SAV method for linearizing the nonlinear term and ensuring unconditional energy stability.

- –

- A LG spectral method for high-resolution spatial discretization.

- We develop a computationally efficient POD-based reduced-order algorithm that fundamentally avoids the redundancy common in conventional approaches. Instead of collecting snapshots over the entire time domain , our algorithm constructs the POD basis using solutions from only a short initial interval (with ). The ROLGE-SFTR-SAV is then employed to extrapolate the solution efficiently over the extended interval , leading to significant savings in both computation time and storage.

- We establish a complete theoretical foundation, including:

- –

- Proofs of unconditional energy stability for both SFTR-SAV and the LG-SFTR-SAV schemes.

- –

- Detailed error estimates for the SFTR-SAV, LG-SFTR-SAV, and ROLGE-SFTR-SAV models. These estimates provide practical guidance for selecting critical parameters such as the POD basis rank d and the snapshot interval length .

- Extensive experiments are conducted to validate the theory and demonstrate efficiency.

- –

- The scheme achieves second-order temporal convergence and spectral spatial convergence.

- –

- The POD eigenvalues exhibit rapid exponential decay, justifying the low-dimensional approximation.

- –

- The ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme achieves a significant reduction in CPU time compared to the full-order model, while maintaining comparable numerical accuracy.

The structure of the remaining paper is as follows. In Section 2, we present the SFTR-SAV schemes for temporal discretization. For the reformulated tFAC equation, we also derive the property that the energy of the SAV scheme is monotonically non-increasing over time. In Section 3, we introduce the full discretization of the tFAC equation and establish the error estimates for the LG-SFTR-SAV scheme. In Section 4, we construct the reduced-order model, derive its stability properties, and perform the error analysis of the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV model. We present several numerical examples to validate the theoretical findings in Section 5. Finally, we summarize the key conclusions in Section 6.

We adopt the following notations throughout this paper. The standard Sobolev spaces and their norms are denoted by and (), respectively [39]. Specifically, for the space , we use for its norm and for its inner product. Additionally, the norm of the space is denoted by .

In the temporal direction, we will adopt the SFTR scheme to discretize Equation (5), resulting in the SFTR-SAV scheme. On this basis, we will further provide a rigorous proof for the energy non-increasing property and error estimation of this scheme.

2. SFTR-SAV Scheme and Error Estimate

2.1. Kernel Properties of the SFTR Formula

Consider a uniform temporal grid on with mesh size , defined by nodal points for . Let denote the solution at time . The SFTR approximation to the Caputo fractional derivative at intermediate time takes the form [20,21,22]

where the coefficients are defined via the generating function

or can be computed directly using the recurrence formula

Lemma 1

([20]). For weights defined in (7), the following properties hold

- (i)

- and for all .

- (ii)

- for all .

- (iii)

- for any .

Discretizing the continuous-time system (5) using the SFTR scheme (7) yields the following time-discrete system.

Problem 1.

For , find satisfying the following equations

where

The following sequence plays a fundamental role in establishing the energy decay property and subsequent error estimates. In [20], the sequence is defined as

Lemma 2

([20]). The sequence , defined in (9), can be computed via the following recurrence relation

initialized by

Lemma 3

([20]). For weights defined in (9), the following properties hold

- (i)

- and for all ,

- (ii)

- for any .

In [20], another sequence is defined as,

2.2. Discrete Energy Dissipation Law of the SFTR-SAV Scheme

Define .

Lemma 4.

The SFTR-SAV scheme (8) is unconditionally stable and satisfies the following discrete energy dissipation law

where

Proof.

Rewrite Equation (8a) as

Multiplying Equation (14) by , summing over , and then applying an index transformation yields,

where which corresponds to the m-th coefficient in the series expansion of the product . From Equation (9), the convolution coefficients satisfy

We then have

Taking in (17), we obtain

Multiplying both sides of (8b) by yields,

Combining (18) and (19) gives,

From the relation established in (12), where for and , it follows that

□

Lemma 5.

For the solution of the discrete problem (8), there exists a positive constant C such that

Proof.

The convolution quadrature theory [40] guarantees approximates with second-order accuracy under mild conditions. Let

Equation (17) can be rewritten in the following form

Taking the difference of (23) for n and , we have

Similarly, it follows from (8b)

Taking in (24) and using (25), we obtain

Omitting the positive third and fourth terms on the left-hand side, we obtain

Summing (27) for and applying the discrete Grönwall inequality yields the desired bound. □

2.3. Temporal Error Estimate

In this section, we define the error terms as

Taking the inner product of Equation (28), we obtain

Subtracting (29) from (8), we have

Theorem 1.

For the solutions of (8) and of (5), the following error estimate is valid

Proof.

Following [8], we note that, similar to other nonlinear equations, the boundedness of the numerical solution is vital for deriving the error estimate. Specifically, the boundedness of is a straightforward result of the stability inequality (13) and the norm equivalence in finite-dimensional spaces. Therefore, we denote

Define . Then, Equation (30a) can be written as

Multiplying Equation (33) by , summing over , and applying an index substitution yields

Upon rearranging the terms in the left-hand side of (34), we have

Since and for we get

Setting in (36), we obtain

Similarly to Equation (21), we deduce that

Substituting Equation (38) into Equation (37) yields,

Multiplying both sides of (30b) by , we get

Substituting (40) into (39), we get

where

According to [8], we estimate as

Therefore,

where

In [41], the proof of has been introduced. Hence,

By applying Lemma 5, we have

Using Equation (44), Young inequality and Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, we derive

Given that and all achieve second-order temporal accuracy, it can be concluded that

Expanding the term through Equation (42) leads to the following estimate

Incorporating the above inequalities into (41), we obtain

The summation for yields,

Through the application of Taylor’s theorem, we can easily deduce that

Applying the above inequality, we obtain

Applying Gronwall’s inequality, we deduce

for sufficiently small , which completes the proof of the theorem. □

By applying the LG method to spatially discretize the semi-discrete SFTR-SAV scheme (LG-SFTR-SAV), the following fully discrete LG-SFTR-SAV scheme is obtained.

3. The LG-SFTR-SAV Scheme

For spatial discretization, we employ Legendre–Gauss–Lobatto (LGL) interpolation points [42] as computational nodes. Specifically, we define discrete nodal sets along the x-axis. The exact solution is approximated by its spectral projection , the space of polynomials of degree at most N, expressed as

where the basis functions is defined as association of Legendre polynomials

constructed specifically to enforce homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions [42]. The approximation space is then defined as

To ensure spectral accuracy, we introduce the orthogonal projection operator characterized by the variational formulation

which satisfies the following optimal approximation property.

Lemma 6

([42]). For any with ,

Problem 2.

Given , find such that

We introduce the approximation errors

where , denote semi-discrete solutions and , represent their fully discrete solutions.

Error Analysis of LG-SFTR-SAV Solutions

Theorem 2.

Let be the solution of the (62). Then the following energy stability holds

where

For , the following error estimate holds

Proof.

The approach developed in Lemma 4 extends directly to prove energy decay for the fully discrete system (63). By a method similar to that of Lemma 5, it can be proven that is bounded. In [8], for any nonlinear equations, ensuring the boundedness of the numerical solution is crucial for establishing the error estimate. The boundedness of is a direct consequence of the stability Lemma 4 and the equivalence of norms in finite-dimensional spaces. For the sake of notational simplicity, we define

By subtracting Equation (62) from Equation (8), we obtain

Set ,

Performing the index shift in Equation (67), we operate on (67) via multiplication by and execute the summation over to n to derive

Upon rearranging the terms in the left-hand side of (68), we have

Equation (68) is rewritten as

In (71), , we have

Multiply both sides of (66b) by , we get

The left-hand side of Equation (72) is rearranged into the following form

The first term on the right-hand side of (72) is rewritten as

The second term on the right-hand side of (72) satisfies

Upon substituting equations (73)–(76) into Equation (72), it follows that

where

We provide the following norm bounds for ,

where .

Similarly, for , we can derive

A term-by-term analysis is conducted for the fifth, and sixth, terms of Equation (77),

Substituting the above expressions into Equation (77), , and applying Lemma 6, we obtain

Summing the above inequalities for , we have

By applying Gronwall’s lemma, we deduce that

□

Corollary 1.

For the solutions of Equation (5) and to Equation (62), respectively, under the conditions of Theorem 2, the following error estimate holds

4. The ROLGE-SFTR-SAV Scheme

In this section, the concept introduced in [29,43] is adopted to construct a POD basis and develop the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV formulation for the tFAC equation.

4.1. Construct the POD Basis and Establish ROLGE-SFTR-SAV Formulation

Consider the snapshot solutions defined in Section 3. The space spanned by these snapshots is denoted as

The existence of at least one non-zero snapshot function is assumed. Let denote an orthonormal basis for , where . Consequently, any snapshot vector admits the expansion

Definition 1

([29]). The POD method seeks a standard orthonormal basis that minimizes the projection error

The basis of rank d optimally captures the dominant features of the snapshot ensemble while reducing dimensionality. A set of solutions of (87) is termed a POD basis of rank d.

We construct the correlation matrix with entries

As is positive semidefinite with rank l. This construction yields the following fundamental result.

Proposition 1

([31]). Let with denote the positive eigenvalues of the correlation matrix B, and their corresponding orthonormal eigenvectors. A rank-d POD basis () is then constructed as

where denotes the k-th component of eigenvector . Moreover, the optimal approximation error satisfies

Define the reduced-order subspace

For , a Ritz operator is denoted by

Then, by functional analysis, there exists an extension of such that and . This projection is defined variationally by

where . The variational formulation (91) ensures is uniquely determined and satisfies the stability bound

Lemma 7

([44]). For each integer d , the projection operator fulfills the inequality:

Problem 3.

Find such that

Remark 1.

Problem 3 demonstrates the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV solutions for the tFAC equation. Specifically, the initial L ROLGE-SFTR-SAV solutions are constructed by projecting the first L classical LG solutions onto a POD basis, and subsequent solutions are generated through extrapolation and iterative solution of equations. This hybrid approach fundamentally differentiates Problem 3 from conventional POD-based reduced-order models [8,28], particularly in how it integrates projection with extrapolation and iteration steps.

We define the approximation errors

where denote the fully discrete solutions obtained from Problem 2 and represent the ROLGE solutions computed in Probelm 3. These error metrics will be analyzed in Section 4.

4.2. Error Estimates of the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV Solution for tFAC Equation

Theorem 3.

The solution to Problem 3 satisfies

where

When , the following error estimate holds

where is the solution of Problem 3, ,

Proof.

The method established in Lemma 4 can be directly extended to establish the energy decay property of the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme (97). Following an approach analogous to that employed in Lemma 5, one can show that is bounded. As noted in [8], with respect to arbitrary nonlinear equations, guaranteeing the boundedness of the numerical solution plays a vital role in establishing the error estimate. The boundedness of and follows directly from the stability result presented in Equation (97) and the equivalence of norms in finite-dimensional spaces. For the sake of notational simplicity, we define

By subtracting Equation (62) from Equation (96), we obtain

For , by Lemma 7 and Equation (101), we have

Set

Multiply both sides of (104) by after replacing n with j in, and sum the index j from 1 to n to obtain

Upon rearranging the terms in the left-hand side of (105), we obtain

where is the m-th coefficient of the series of the product which by Lemma (3) yields and for We then have

In (108), , we have

Multiply both sides of (102b) by , we get

The left-hand side of Equation (109) is rearranged into the following form

The first term on the right-hand side of (109) is rewritten as

The second term on the right-hand side of (109) satisfies

Upon substituting Equations (110)–(113) into Equation (109), it follows that

where

We decompose into the following components

The terms can be bounded separately by

Let , we have

Similarly, for , we can derive

Using Equation (116) and Lemma 7, we have

For using Lemma 6 and Theorem 1, we obtain

Using Equations (117) and (119), Lemma 6, we have

If , upon substituting Equations (118)–(120) into Equation (114), we obtain

By summing (121) for , using Lemma 7 and Equations (103) and (119), we have

Employing the Gronwall lemma, we derive

□

Corollary 2.

is the solution of the (96), we deduce the error estimate

where for , and for .

Remark 2.

The error bounds derived in Theorem 3 and Corollary 2 inform the choice of the number of POD modes d. Specifically, d should satisfy

where denotes the POD eigenvalues. The iterative error, quantified by , dictates the need for POD basis updates during extrapolation. Specifically, a POD basis update is required when

Remark 3.

We remark that while the numerical scheme and the accompanying analysis presented in this work are developed directly for the one-dimensional spatial case, they can be naturally extended to higher-dimensional settings. In fact, the efficiency gain of the reduced-order algorithm, when compared to its non-reduced counterpart, becomes even more pronounced in multi-dimensional problems. The one-dimensional framework is adopted primarily for clarity of exposition, as it allows for a more transparent illustration of the algorithmic construction and a streamlined theoretical analysis, without loss of generality.

5. Numerical Tests

In this section, we verify the convergence rates of the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme and demonstrate its superior efficiency relative to the LG-SFTR-SAV scheme. The temporal convergence rate for the variable u is obtained by the formula

by which the rates for and s can also be derived similarly. Since the explicit form of the solution of (1) is unknown, we assume the solution as where and rewrite (1) by adding the source term

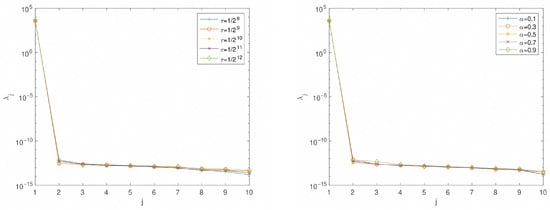

We illustrate the fast decay property of the eigenvalues in Figure 1 (left) for different with fixed and in Figure 1 (right) for different with fixed , under the setting . It is clear that only the first several are sufficient to capture the essential properties. For the following test, we set . While smaller values of d can yield acceptable results, the choice of provides a more robust solution.

Figure 1.

The fast decay of the eigenvalues for different with fixed (left) and for different with fixed (right), under the setting .

In Table 1 and Table 2, we set and fixing . Both tables present the temporal convergence behavior and computational efficiency of the LG-SFTR-SAV and ROLGE-SFTR-SAV schemes, respectively, for varying values of the fractional order parameter . The time step is successively refined as , and the corresponding errors in the -norm of the solution, its gradient, and the auxiliary variable s are reported, along with their convergence rates and CPU times.

Table 1.

The temporal convergence rates and CPU time of the LG-SFTR-SAV scheme.

Table 2.

The temporal convergence rates and CPU time of the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme.

Both schemes exhibit a clear second-order temporal convergence across all error measures, as indicated by the consistent rate value of 2.00. In terms of computational cost, the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme shows a significant reduction in CPU time compared to the LG-SFTR-SAV scheme, while maintaining nearly identical accuracy and convergence rates. For instance, at , the CPU time for the ROLGE variant is approximately 2.5 s, compared to about 4.3 s for the LG variant—a reduction of over . This efficiency gain is consistent across all time steps and values of , underscoring the advantage of the reduced-order approach.

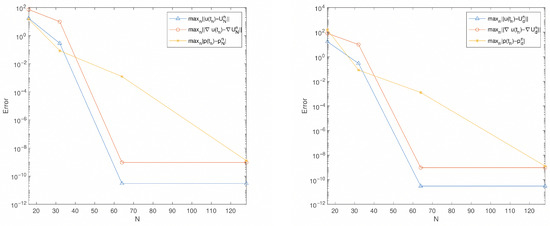

In Figure 2 we investigate the spatial discretization errors under the setting , . Clearly, the errors for both LG-SFTR-SAV and ROLGE-SFTR-SAV schemes demonstrate spectral accuracy, as the errors decrease rapidly with increasing spatial resolution N. Both schemes exhibit nearly identical error levels and convergence rates, confirming that the reduced-order approach preserves the excellent spatial accuracy of the spectral method while maintaining computational efficiency.

Figure 2.

The spectral accuracy of the LG-SFTR-SAV scheme (left) and the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme (right), under the setting .

These results confirm that the ROLGE-SFTR-SAV scheme preserves the high-order accuracy of the original LG-SFTR-SAV method while offering enhanced computational efficiency, making it a preferable choice for long-time simulations or problems requiring repeated evaluations.

6. Conclusions

This study has presented a novel and efficient numerical framework for solving the tFAC equation. By combining the SAV method for linearization, the SFTR for temporal discretization, and a LG spectral method in space, we developed a fully discrete scheme that is both energy-stable and computationally efficient. To further reduce the computational cost, a ROE model based on POD was introduced, effectively minimizing redundant computations while preserving numerical accuracy. Theoretical proofs of stability and error estimates were provided, confirming the reliability of the proposed approach. Numerical experiments demonstrated the validity of the method and aligned well with the theoretical predictions. This work offers a practical and theoretical foundation for simulating time-fractional phase-field models over long time intervals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H. and H.L.; methodology, C.H.; numerical simulation, B.Y. and C.H.; formal analysis, C.H. and B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H.; validation, C.H. and B.Y.; writing—review, B.Y. and H.L.; supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12561068 to H.L. and No. 12201322 to B.Y.), Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (No. 2025ZD036 to H.L.), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Program Project (No. 2025KYPT0098 to H.L.) and the Autonomous Region Level High-Level Talent Introduction Research Support Program in 2022 (No. 12000-15042224 to B.Y.).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editors for their invaluable comments, which greatly refined the content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| POD | proper orthogonal decomposition |

| ROLGE | reduced-order Legendre–Galerkin extrapolation |

| ROLGE-SFTR-SAV | reduced-order LG extrapolation SFTR-SAV model |

References

- Sasso, M.; Palmieri, G.; Amodio, D. Application of fractional derivative models in linear viscoelastic problems. Mech. Time-Depend. Mat. 2011, 15, 367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Xie, Z.; Gu, J.; Sun, H. A 1D thermomechanical network transition constitutive model coupled with multiple structural relaxation for shape memory polymers. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 035024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.-K.; Long, Z.; Xu, F.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Yang, M. Investigation on the viscoelastic behavior of an fe-base bulk amorphous alloys based on the fractional order rheological model. Acta Phys. Sin. 2015, 64, 136101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, S. Fractional derivative approach to non-Darcian flow in porous media. J. Hydrol. 2018, 566, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linchao, L.; Xiao, Y. Analysis of vertical vibrations of a pile in saturated soil described by fractional derivative model. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 526–532. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Liu, F. Boundary layer flows of viscoelastic fluids over a non-uniform permeable surface. Comput. Math. Appl. 2020, 79, 2376–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Leng, J.; Gu, J.; Yin, C.; Sun, H. Modeling the strain rate-, hold time-, and temperature-dependent cyclic behaviors of amorphous shape memory polymers. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 075050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Azaïez, M.; Xu, C. Error analysis of a reduced order method for the Allen-Cahn equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 2024, 203, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, G.; Bersetche, F.M. Numerical approximations for a fully fractional Allen–Cahn equation. Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2021, 55, S3–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z. Time-fractional Allen–Cahn equations: Analysis and numerical methods. J. Sci. Comput. 2020, 85, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, N.; Abbas, M.; Iqbal, M.K.; Baleanu, D. A numerical investigation of Caputo time fractional Allen–Cahn equation using redefined cubic B-spline functions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B.; Liao, H.l.; Zhang, L. Simple maximum principle preserving time-stepping methods for time-fractional Allen-Cahn equation. Adv. Comput. Math. 2020, 46, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.l.; Tang, T.; Zhou, T. An energy stable and maximum bound preserving scheme with variable time steps for time fractional Allen–Cahn equation. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 43, A3503–A3526. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, D.; Huang, H.; Liu, H. Linearly Implicit Schemes Preserve the Maximum Bound Principle and Energy Dissipation for the Time-fractional Allen–Cahn Equation. J. Sci. Comput. 2024, 101, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Sun, H.W. A dimensional splitting exponential time differencing scheme for multidimensional fractional Allen-Cahn equations. J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 87, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Zhu, H.; Xu, C. Highly efficient schemes for time-fractional Allen-Cahn equation using extended SAV approach. Numer. Algorithms 2021, 88, 1077–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qin, R. The exponential SAV approach for the time-fractional Allen–Cahn and Cahn–Hilliard phase-field models. J. Sci. Comput. 2023, 94, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, X. A high-efficiency second-order numerical scheme for time-fractional phase field models by using extended SAV method. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 102, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, J. The scalar auxiliary variable (SAV) approach for gradient flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 353, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Huang, C.; Alikhanov, A.A.; Yin, B. A high-order discrete energy decay and maximum-principle preserving scheme for time fractional Allen–Cahn equation. J. Sci. Comput. 2023, 96, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z. Efficient shifted fractional trapezoidal rule for subdiffusion problems with nonsmooth solutions on uniform meshes. Bit Numer. Math. 2022, 62, 631–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Necessity of introducing non-integer shifted parameters by constructing high accuracy finite difference algorithms for a two-sided space-fractional advection–diffusion model. Appl. Math. Lett. 2020, 105, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkwein, S. Proper Orthogonal Decomposition: Theory and Reduced-Order Modelling; Lecture Notes; University of Konstanz: Konstanz, Germany, 2013; Volume 4, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Song, Z. A reduced-order energy-stability-preserving finite difference iterative scheme based on POD for the Allen-Cahn equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020, 491, 124245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, Z. A reduced-order finite element method based on proper orthogonal decomposition for the Allen-Cahn model. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2021, 500, 125103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, D.; Song, Z.; Zhang, F. Numerical analysis of an unconditionally energy-stable reduced-order finite element method for the Allen-Cahn phase field model. Comput. Math. Appl. 2021, 96, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Jiang, L.; Li, Q. A reduced order method for Allen–Cahn equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2016, 292, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Azaiez, M.; Xu, C. Reduced-order modelling for the Allen-Cahn equation based on scalar auxiliary variable approaches. J. Math. Study 2019, 52, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Chen, G. Proper Orthogonal Decomposition Methods for Partial Differential Equations; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z. A reduced-order extrapolation algorithm based on SFVE method and POD technique for non-stationary Stokes equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 247, 976–995. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z. A POD-based reduced-order TSCFE extrapolation iterative format for two-dimensional heat equations. Bound. Value Probl. 2015, 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H.; Luo, Z. An optimized finite element extrapolating method for 2D viscoelastic wave equation. J. Inequal. Appl. 2017, 2017, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Teng, F. An optimized SPDMFE extrapolation approach based on the POD technique for 2D viscoelastic wave equation. Bound. Value Probl. 2017, 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Teng, F. Reduced-order proper orthogonal decomposition extrapolating finite volume element format for two-dimensional hyperbolic equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2017, 38, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Luo, Z.; Yang, J. A reduced-order extrapolated natural boundary element method based on POD for the 2D hyperbolic equation in unbounded domain. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2019, 42, 4273–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Teng, F.; Chen, J. A POD-based reduced-order Crank–Nicolson finite volume element extrapolating algorithm for 2D Sobolev equations. Math. Comput. Simul. 2018, 146, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Proper orthogonal decomposition-based reduced-order stabilized mixed finite volume element extrapolating model for the nonstationary incompressible Boussinesq equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2015, 425, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunzburger, M.; Jiang, N.; Schneier, M. An ensemble-proper orthogonal decomposition method for the nonstationary Navier–Stokes equations. J. Numer. Anal. 2017, 55, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Fournier, J.J. Sobolev Spaces; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 140. [Google Scholar]

- Lubich, C. Discretized fractional calculus. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1986, 17, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xu, J. Convergence and error analysis for the scalar auxiliary variable (SAV) schemes to gradient flows. J. Numer. Anal. 2018, 56, 2895–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, L.L. Spectral Methods: Algorithms, Analysis and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Kunisch, K.; Volkwein, S. Galerkin proper orthogonal decomposition methods for a general equation in fluid dynamics. J. Numer. Anal. 2002, 40, 492–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, H.; Yin, B. Reduced-order Legendre-Galerkin extrapolation method based on proper orthogonal decomposition for Allen-Cahn equation. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025. submitted. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.