Abstract

This study introduces a nonlinear fractional bi-susceptible model for COVID-19 using the Atangana–Baleanu derivative in Caputo sense (ABC). The fractional framework captures nonlocal effects and temporal decay, offering a realistic presentation of persistent infection cycles and delayed recovery. Within this setting, we investigate multiple transmission modes, determine the major risk factors, and analyze the long-term dynamics of the disease. Analytical results are obtained at equilibrium states, and fundamental properties of the model are validated. Numerical simulations based on the Toufik–Atangana method further endorse the theoretical results and emphasize the effectiveness of the ABC derivative. Bifurcation analysis illustrates that adjusting time-invariant treatment and awareness efforts can accelerate pandemic control. Sensitivity analysis identifies the most significant parameters, which are used to construct an optimal control problem to determine effective disease control strategies. The numerical results reveal that the proposed control interventions minimize both infection levels and associated costs. Overall, this research work demonstrates the modeling strength of the ABC derivative by integrating fractional calculus, bifurcation theory, and optimal control for efficient epidemic management.

1. Introduction

COVID-19, which results from infection with the Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is an exceptionally contagious disease that has resulted in millions of deaths globally. The pandemic has had a profound impact on personal lives and has caused major disruptions to economies and GDP even in the most advanced countries. The virus spreads primarily through direct or indirect physical contact between people [1]. Transmission usually happens when an individual breathes in or comes into contact with droplets of saliva or mucus from someone who is infected, particularly when they cough or sneeze. This mode of spread puts healthy people at considerable risk. Initially identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, the virus rapidly spread across China and eventually reached more than 223 countries across Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Australia [2]. The incubation period, which refers to the time between viral exposure and symptom onset, generally ranges from 2 to 14 days. During this phase, humans can transmit the virus even without showing symptoms. Most COVID-19 cases present mild to moderate symptoms, including fever, fatigue, muscle aches, cough, severe headaches, diarrhea, vomiting, insomnia, nasal congestion, and a sore throat. However, in some instances, the disease can progress to severe complications, such as difficulty breathing, confusion, chest pain, or loss of speech or movement, necessitating immediate medical intervention. Those experiencing severe symptoms should seek immediate emergency care [3]. The highest risk of severe disease is among individuals with preexisting health conditions like respiratory infections, compromised immune systems, hypertension, diabetes, and those over the age of 60. It is essential for these individuals to take additional precautions to safeguard themselves from infection [4].

Globally, between 20 November and 17 December 2023, there was a increase in new COVID-19 cases compared to the previous 28-day period, with more than 850,000 new infections recorded. In contrast, new deaths decreased by , amounting to more than 3000 fatalities. By 17 December 2023, the global totals had reached over 772 million confirmed cases and nearly 7 million deaths. During the period from 13 November to 10 December 2023, there was a significant uptick in COVID-19 hospitalizations and ICU admissions, with increases of and , respectively, among countries consistently reporting data [5]. This period saw over 118,000 new hospitalizations and more than 1600 new ICU admissions. As of 18 December 2023, the JN.1 sub-lineage of the BA.2.86 Omicron variant has been designated as a separate variant of interest (VOI) due to its rapid rise in prevalence [5,6]. JN.1, a descendant of the BA.2.86 lineage, has developed additional mutations that enhance its transmissibility while maintaining the immune evasion properties of its parent variant. Globally, the EG.5 variant remains the most commonly reported VOI and is closely related to the XBB variants observed in the U.S. over the past six months. Notably, EG.5 features a mutation that can partially evade immunity conferred by previous infections or vaccinations [7].

During the fall and winter months, respiratory viruses often see a significant increase in cases. With the emergence of COVID-19 in 2020, it joined the ranks of common respiratory viruses like the flu and RSV, which typically surge in colder weather. Although COVID-19 has evolved from a pandemic to an endemic status, it continues to exhibit a pattern of heightened activity twice a year. As of August 2024, COVID-19 continues to pose a significant challenge worldwide, with recent data indicating a resurgence in cases across multiple regions [7]. This summertime surge, observed in areas like Europe, the Americas, and the Western Pacific, has raised concerns among health experts and organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO). The increase in cases is attributed to several factors, including waning immunity, increased travel, and the emergence of new, more transmissible variants such as the FLiRT group, which are subvariants of the Omicron strain [8,9]. Interestingly, this resurgence is happening during the summer months, a period typically less associated with respiratory virus transmission. However, COVID-19’s ability to circulate year-round and its continuous mutation have made such atypical patterns more common. WHO reports have shown a rise in hospitalizations and ICU admissions, though these remain below the peak levels seen earlier in the pandemic. Nonetheless, the persistence of the virus and its potential to evolve into more severe variants have led to renewed calls for vigilance, especially in maintaining vaccination efforts among high-risk groups with new vaccines on the way [10]. The current situation underscores the need for ongoing public health measures and personal precautions. Although the overall severity of infections appears to be lower than in previous waves, the threat of long COVID remains, particularly for older and vulnerable populations. As we navigate this latest phase of the pandemic, it is clear that COVID-19 will continue to be a part of our lives for the foreseeable future [11].

Mathematical modeling is a vital tool in combating infectious diseases, helping to understand, predict, and manage their spread [12,13,14]. By integrating mathematical methods with epidemiological data, researchers can simulate scenarios and assess several precautionary measure, providing crucial insights for public health decisions. These models are essential for policymakers, enabling them to develop strategies that mitigate the impact of diseases and protect public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous models were created to study the virus’s transmission dynamics, evolution, and the effectiveness of various measures. Predictive models have been particularly valuable in forecasting infection rates and evaluating interventions like vaccination and social distancing [15]. They also help estimate outcomes such as case numbers, hospitalizations, and fatalities, while identifying vulnerable populations and potential hotspots. Further research has expanded these models to include factors like immunity waning and the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions. These models provide insights into how such factors influence the pandemic’s course, offering powerful tools for designing and implementing control measures [16]. By developing these models, public health authorities are better equipped to make informed decisions and take proactive actions, improving our capacity to manage and address threats from infectious diseases.

Fractional-order derivatives extend classical differentiation to non-integer orders, allowing memory and hereditary effects to be embedded within dynamical systems [17,18]. This feature is particularly relevant for biological and epidemiological modeling, where standard integer-order models often struggle to represent time-dependent delays, immune memory, and cumulative exposure accurately [19,20]. By incorporating these effects, fractional derivatives improve both stability and biological realism, offering a more refined description of disease dynamics, as supported by several studies demonstrating their superiority over conventional integer-order models [21,22,23]. Additionally, fractional models can represent anomalous diffusion and complex transmission dynamics more accurately, reflecting real-world phenomena where individuals do not interact or move at constant rates [24].

Among the various fractional operators used in epidemic modeling, such as Riemann–Liouville (RL), Caputo, and Caputo–Fabrizio (CF), the ABC operator has emerged as a particularly powerful tool [25,26,27]. While the RL, Caputo, and RL operators have been used extensively, they each come with limitations that can hinder accurate modeling of real-world phenomena. The RL operator, for instance, often requires fractional initial conditions that are not always practical or well-defined in real-world scenarios. The Caputo derivative, although more practical with classical initial conditions, still has limitations in accurately modeling abrupt changes or complex memory effects [25]. The RL operator, despite its advantage of avoiding singularities, does not fully capture the diverse range of memory effects in systems with more complex behaviors. In contrast, the ABC operator offers superior modeling capabilities by addressing these limitations [28]. It uniquely combines non-local, non-singular properties with a more realistic representation of memory effects. This operator avoids the singularity issues present in the RL and CF derivatives and offers a more comprehensive framework for incorporating complex memory and hereditary effects without the restrictive assumptions required by the Caputo and RL operators [29,30]. This makes the ABC operator particularly effective for capturing the full spectrum of epidemic dynamics, leading to more accurate predictions and robust control strategies [31]. Therefore, although earlier models used RL, Caputo, and CF derivatives to improve our understanding, the ABC operator offers a more realistic and effective way to model and control epidemic outbreaks [32,33,34,35].

Optimal control analysis of epidemics involves designing strategies to mitigate the impact of infectious diseases on individuals while considering constraints and costs. This analysis typically uses mathematical models to simulate the spread of an epidemic and evaluates various control measures, such as quarantine, vaccination, and treatment strategies, to identify the most effective interventions [36,37]. The goal is to balance the cost of implementing these measures with their benefits, such as reducing infection rates and mitigating the burden on healthcare systems. Techniques from optimization theory, including dynamic programming and Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle, are often employed to derive control policies that optimize specific objectives, like minimizing the infected individuals or reducing the overall cost of interventions [38,39]. These models also account for factors like the variability in individual responses to treatments and the heterogeneity in population structure, providing a framework to assess how different control strategies can influence the trajectory of an epidemic. By incorporating real-time data and adapting to changing conditions, optimal control analysis can guide public health decision-making, enhance preparedness, and improve response strategies to better manage and eventually contain epidemic outbreaks [40].

In this research, we extend a recent COVID-19 model [41] with the inclusion of two susceptibility compartments, introducing the concept of awareness among susceptible individuals. We investigate the model’s global behavior, perform a sensitivity analysis, and examine the impact of constant treatment and awareness interventions. To formulate effective time-dependent disease control strategies, we establish an optimal control problem, apply Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle, and approximate it using the Toufik–Atangana method [42]. Numerical simulations demonstrate that our proposed approach accurately captures the dynamics of the model and effectively addresses the control problem.

The manuscript consists of seven sections. In Section 2, the compartmental model for COVID-19 is developed, including its dimensionless fractional representation. Section 3 addresses the aspects of existence, uniqueness, positivity, boundedness, equilibrium states, the threshold parameter, and stability analysis. Section 4 and Section 5 present numerical analyses using the Toufik–Atangana method, along with discussions, graphs, sensitivity analysis, bifurcation studies, and the impacts of constant treatment and awareness. Section 6 formulates an optimal control problem considering time-varying interventions and assesses the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the optimal strategies. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the main findings and offers recommendations.

3. Analytical Results with Discussions

This section presents theoretical results such as the existence and uniqueness of solutions, positivity and boundedness, the calculation of the reproductive number, and the evaluation of local and global stability at steady state points [45]. Each of these topics will be explored in the subsequent subsections.

3.1. Existence of a Unique Solution

Lemma 1 provides the conditions under which solutions to system (7) are unique and exist.

Lemma 1

([46]). For the fractional-order system (7) with , a unique solution exists on the interval if the function meets the Lipschitz condition with respect to the second argument.

Theorem 2.

For an initial point , there exists a unique solution satisfying system (7) .

Proof.

Let where and . Next, consider mapping where , with

For any Y, Z in , we have

where . Therefore, the function satisfies the Lipschitz condition. Consequently, the system (7) has a unique solution in . This completes the proof. □

3.2. Essential Model Characteristics

Now, we demonstrate the non-negativity and boundedness of the solution of system (7) for .

Theorem 3.

The system (7) has a positive and bounded solution provided that the initial conditions are non-negative .

Proof.

With , the dynamics of the total population is given as

After extensive computations, we conclude that

Since and , it follows that

Hence, originating in remains bounded for all . Thus, all other states of (7) also stay bounded over time [28].

To verify the non-negativity of solutions, we write the first equation of model (7) as follows:

Since the solutions remain bounded, Equation (9) simplifies to

where is defined as a constant.

Applying the Laplace transform to inequality (10) gives

After some manipulations, we obtain the following:

Using the inverse Laplace transform, the inequality becomes

The solution is always positive for , because it exceeds the product of positive terms. Similarly, all other solutions remain positive for . Thus, any solution in will asymptotically enter and stay within the feasible region provided initial conditions are non-negative.

Hence, the region is positively invariant under system (7). □

3.3. Equilibrium Points and Threshold Parameter

The disease-free equilibrium (DFE) signifies a state of the Corona model in which the disease is completely absent from the human community. Mathematically, this is the state where infectivity is zero. Therefore, the model (7) has a DFE point , with coordinates

In infectious disease modeling, the reproductive number indicates whether an outbreak will cease or continue to spread. This is commonly denoted by , representing the new infections induced by an infected human in a susceptible population. When , each infected person spreads the disease to more than one other human, possibly causing an epidemic. Conversely, if , each infected individual, on average, passes the disease to less than one individual, implying that the disease will vanish over time [43].

For model (7), we implement the next-generation matrix approach that focuses on the dynamics of compartments I and T, using sensitivity matrices for new infection and transition rates. These matrices are

The Jacobian of the matrices and , evaluated at the point , are

Hence, the number

as the spectral radius of the matrix

specifies the threshold parameter value for the model (7).

The model (7) has a unique equilibrium for the disease-present case, occurring at , where

The third equation of the model (7) simplifies to

At the Corona present state, where , it follows that

Plugging in and values in the above equation, we have

By Descartes’ rule of signs, polynomial (14) exhibits one sign change in its coefficients, given that and when . Therefore, for , it has precisely one positive real root, denoted as I, which justifies the existence of the equilibrium .

3.4. Stability Investigations

To prove that our problem is well posed, we investigate the stability of the model (7) at equilibrium points. To justify global stability, we implement the theory of Lyapunov functions [47] along with the LaSalle Invariance Principle (LIP) [48].

3.4.1. Analysis of Local Dynamics

Local stability is explored by linearizing the system at the equilibrium points and evaluating the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix. If the real parts of the eigenvalues are less than zero, the equilibrium points are stable.

Theorem 4.

Corona-free equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable (LAS) when . Conversely, if , the equilibrium becomes unstable.

Proof.

The Jacobian for the system (3), when computed at , is given by

Then has the following eigenvalues:

The real parts of the eigenvalues are negative, while the real part of the eigenvalue is negative provided . This establishes the result that is LAS if . □

Theorem 5.

Corona-present equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable (LAS) whenever . Whenever , the point is unstable.

Proof.

The Jacobian for the system (7) at can be expressed as

To obtain eigenvalues of , we set , which is

Incorporation of , , , and in above expression leads to

This can also be written as

Clearly, the first two eigenvalues of are

The remaining eigenvalues are obtained as the roots of the equation

We apply the Routh–Hurwitz method. We need to prove that the polynomial (15) is a Hurwitz polynomial. For this, we have to show that , , and are positive and that . We verify these properties as follows. On comparison with (15), we have

Also,

which is clear greater than . Consequently, . This implies that the expression given in (15) is a Hurwitz polynomial. Hence, by Routh–Hurwitz criterion, the eigenvalues of the polynomial (15) are negative. Thus, the point of system (7) is LAS, which completes the proof. Once the dynamical system (7) achieves stability at , the Coronavirus will remain in individuals, validating the claim. □

3.4.2. Analysis of Global Dynamics

Global stability is generally established using techniques such as Lyapunov functions to demonstrate that all trajectories converge to the equilibrium.

Theorem 6.

The equilibrium state is globally asymptotically stable (GAS) when .

Proof.

Define a candidate Lyapunov function, given by the expression

Taking the fractional derivative of both sides with respect to time yields

Substitution of derivatives leads to

Performing some computations along with substitutions, we obtain the following expression:

Clearly, , when . Specifically, if , , . Thus, all trajectories originating from the initial condition ultimately reach a set where , which is

where the largest invariant subset reduces to the equilibrium point . Thus, the point is GAS. □

Theorem 7.

The steady-state point is globally asymptotically stable (GAS) if .

Proof.

Assume a candidate Lyapunov function, defined by the expression

Fractional differentiation of both sides gives

The inclusion of derivatives leads to

This can be written as

Applying the Arithmetic–Geometric Inequality, we verify that

Therefore, . In particular, iff and . Thus, all solution curves originating from non-negative ICs will eventually converge to a set where , i.e.:

Thus, the largest invariant set in is the endemic equilibrium , indicating that is GAS [48]. □

4. Computational Analysis-I

In this segment, we study the numerical stability of the model (7) using the Toufik–Atangana method [42]. This method transforms system (7) into its discrete form as follows:

At each time step , the system variables are updated iteratively based on the initial conditions and a discrete summation process. The general update formula for each variable X (where X represents , , I, T, R) is given by

where the summation term is defined as

The coefficients and in (19) capture the influence of past states on the current state and are given by

Specifically, weights the contribution of the function , reflecting the influence of the state at the previous time level on the current update, while accounts for the correction associated with the previous step , ensuring numerical consistency and stability in the fractional scheme. These coefficients decay as increases, indicating that more recent states exert a stronger influence than older ones, but past states are never completely neglected.

Thus, each state variable follows the same iterative structure, with the function determining the system (7) dynamics. Using the scheme (18), we evaluate the effect of a uniform treatment strategy at varying coverage levels. A detailed discretization of the Toufik–Atangana numerical scheme for the equation of type (7) is given in [42,49].

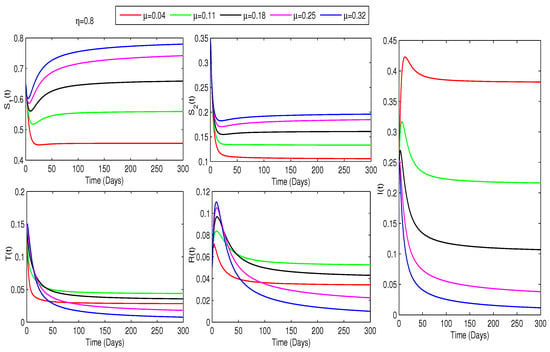

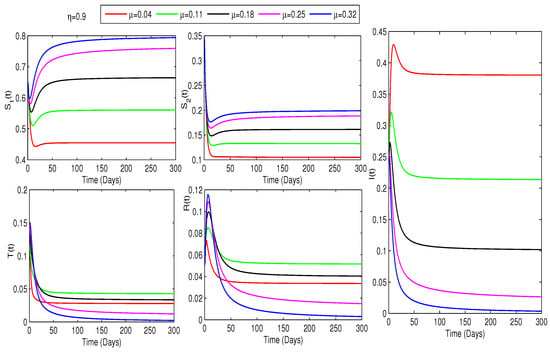

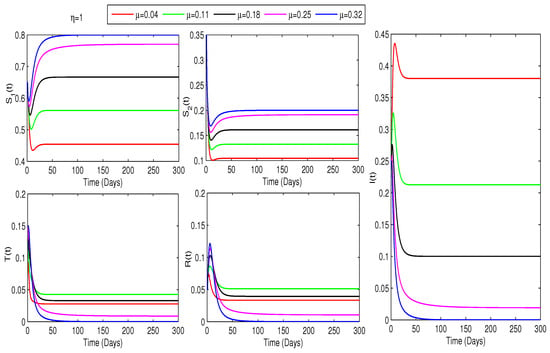

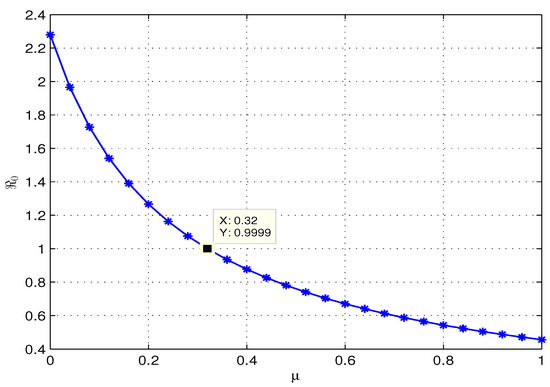

Impact of Time-Invariant Treatment

This study investigates how treatment coverage affects the population dynamics, as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. Higher treatment rates () and fractional orders () significantly reduce infections while increasing recovery. Greater treatment coverage also raises the susceptible populations and . Notably, Figure 4 suggests that controlling COVID-19 is feasible if infected cases go through treatment as rises. Additionally, determining at varying treatment levels is essential for assessing COVID-19 control. Figure 5 shows that higher treatment rates reduce transmission, but the virus persists until at least of cases are treated. Below this threshold, , indicating continued spread, while at or more, , ensuring disease control. Therefore, Figure 4 and Figure 5 confirm that treating at least of infected individuals is essential for eradicating COVID-19.

Figure 2.

Impact of treatment on COVID-19 dynamics for : Higher and increase and communities while reducing infections.

Figure 3.

Effect of treatment on COVID-19 dynamics for : An increase in and boosts and populations while lowering infections.

Figure 4.

Impact of treatment on COVID-19 dynamics for : Higher and increase and communities while reducing infections. Infectivity becomes zero when and .

Figure 5.

Effect of treatment on . At a treatment level, falls below 1.

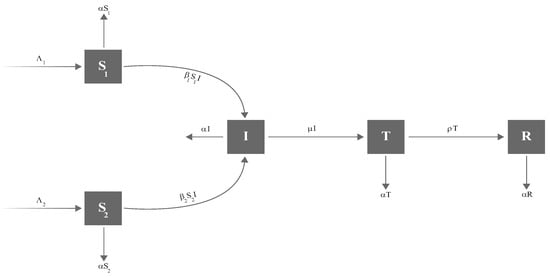

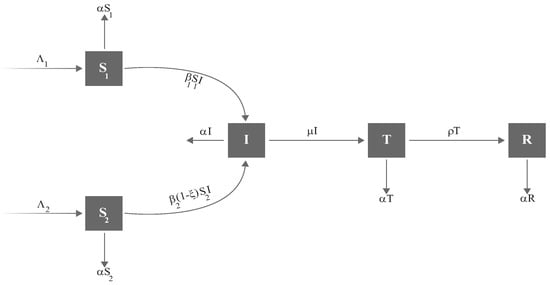

5. Refined Model for Disease Control

We now introduce a parameter in the model to capture the effect of awareness sessions in lowering the transmission rate from susceptible individuals () to infected individuals (I). These sessions address key topics such as hand hygiene, mask-wearing, social distancing, vaccination, symptom recognition, testing procedures, isolation, travel recommendations, protection of vulnerable groups, and managing mental health. These sessions can be organized through community gatherings, social media platforms, educational resources, or healthcare facilities. By increasing awareness, the parameter may help to slow the transition from to I, thereby restricting the virus spread. Considering these factors, the revised dynamics of the model, illustrated in Figure 6, is described as follows:

with the initial conditions (6). In the revised model (20), represents the susceptible who have not gone through any awareness sessions, whereas represents the susceptible who have attended awareness sessions.

Figure 6.

Updated Corona model with the addition of awareness rate .

5.1. Analytical Results for Revised Model

The disease-free equilibrium of the revised model (20) has the following coordinates:

The reproduction number of the model (20) is computed to give the following number:

The Corona-present equilibrium of the model (20) has the following coordinates:

The polynomial (21) exhibits a single sign change in its coefficients, indicating the presence of one positive real root, denoted by . Hence, the equilibrium point exists when .

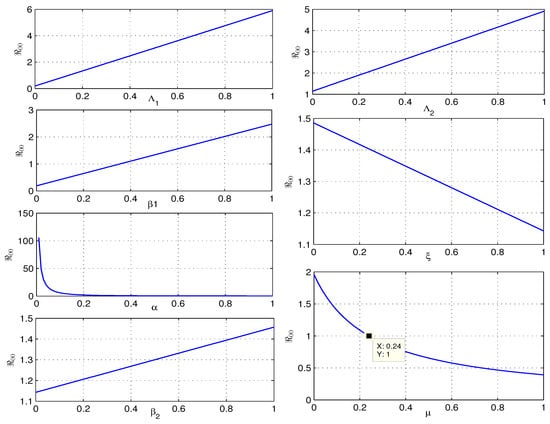

5.2. Sensitivity of Parameters

Sensitivity analysis [50,51] evaluates the robustness of a model by identifying which parameters have the greatest impact on outcomes, particularly the threshold in system (20). The normalized forward sensitivity index [50] for a parameter p is defined as follows:

which shows how variations in p affect . Parameters with the highest absolute sensitivity indices are the most significant, offering critical insights for accurate epidemic predictions.

The following are the computed sensitivity indices:

Table 2 shows that , , , and increase : a 10% increase in these model parameters leads to proportional changes of 8.584%, 1.416%, 8.584%, and 1.416%, respectively. In contrast, , , and reduce . A 10% increase in these parameters will decrease by 1.159%, 2.857%, and 91.298%, respectively (see Figure 7). Ignoring and , is most sensitive to , followed by , then , , and . Given that the natural death rate is difficult to manage, efforts should focus on decreasing through measures like mask-wearing, hygiene practices, and social distancing, followed by .

Table 2.

Computed sensitivities for when .

Figure 7.

Graph of and the related sensitive parameters.

This analysis emphasizes the key parameters for controlling COVID-19, suggesting that preventive strategies such as wearing masks, maintaining social distancing, practicing good hygiene, and raising awareness are more effective than treatment procedures.

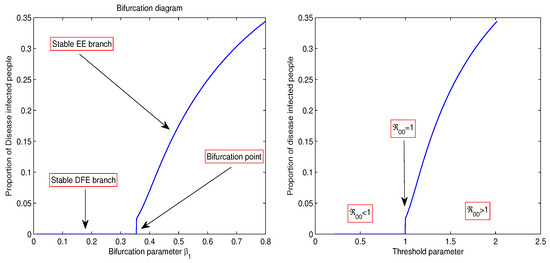

5.3. Forward Bifurcation

In this section, we examine the bifurcation behavior of system (20). We perform bifurcation analysis numerically by varying a key transmission parameter while keeping all other parameters constant. For each parameter value, the fractional-order system (20) was solved using the Toufik–Atangana numerical scheme. After eliminating transient dynamics, the asymptotic value of the infected population was recorded and plotted against the bifurcation parameter.

As shown in Figure 8, when , there are no infected individuals, and the disease-free equilibrium is stable, signifying the elimination of the disease. Conversely, when , the system undergoes a forward transcritical bifurcation at , resulting in a shift in stability from to the endemic equilibrium , where the disease remains present in the community. In this case, both equilibria coexist, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Bifurcation diagram showing the bifurcation point at which Corona model (20) experiences a transcritical bifurcation.

6. Optimal Control Setup and Analysis

The objective of analyzing treatment and awareness interventions is to formulate an optimal strategy for controlling COVID-19. This strategy is designed to minimize infections while increasing susceptible and recovered populations at minimal cost. Using Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle (PMP) [14], we establish the necessary conditions for optimal controls. Two control variables, and , modulate treatment () and awareness () rates, enabling dynamic adjustments to effectively reduce infection while managing resources [37,51], thereby supporting well-informed public health decisions.

Therefore, the model adjusted with control variables and is described as

with the initial conditions given in (4).

We define the following cost functional:

The weights are non-negative constants associated with states and controls. The space of controls is given by

We seek the best controls and for treatment and awareness within the control set , to minimize the functional cost (23), i.e.,

For optimality conditions, we construct the Hamiltonian as follows:

where is a column vector of state variables, and , , , , and are the corresponding adjoint variables.

From (25), we derive the following system of adjoint equations:

along with the transversality conditions

State equations (22) are derived from the Hamiltonian by computing the following derivatives:

Equations define optimal characterizations for the controls and , stated as

6.1. Simulations and Results

We provide the numerical results of the control problem (22) and provide a discussion of the corresponding results in this subsection. We implement the Toufik–Atangana scheme (18) in the forward direction with two controls to approximate the state equations (22), while the adjoint system (26) is solved backward in time. The control functions are iteratively updated in discrete time steps . The procedure for approximating the necessary optimality conditions is described as follows:

- Set the control for .

- Determine using Equation (29).

- Improve using .

- Terminate the iterations when for ; otherwise, increase index k by 1 and go to Step 2.

The tolerance level is set to achieve the desired precision.

We discuss the control problem (24) for the following three different cases:

- Implementation of the treatment strategy only.

- Implementation of the awareness strategy only.

- Implementation of treatment () and awareness () as a combined strategy.

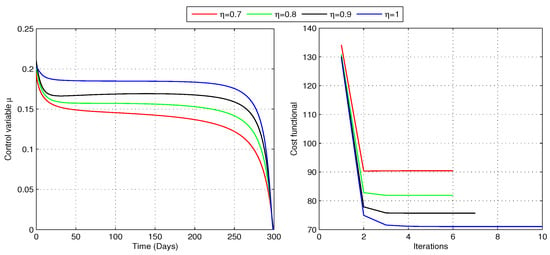

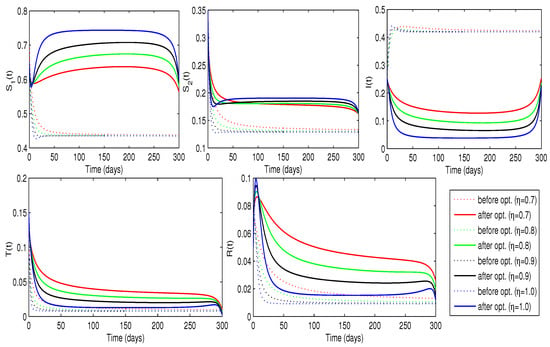

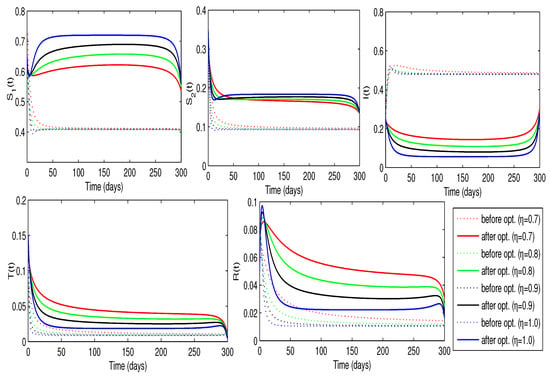

6.1.1. Case-1: Implementation of Treatment Only Strategy

To determine the optimal treatment rate for problem (24), we analyze the cost functional (23) with and , while maintaining a constant awareness rate . The non-zero weighting coefficients reflect the relative importance of disease burden and treatment expenses, with a higher value of placing more emphasis on reducing the number of individuals in the I compartment. As illustrated in Figure 9, the optimizer and the cost functional vary across different fractional orders. The iteration counts for the optimal controls and the associated implementation costs are described in Table 3. The results suggest that during the initial stage of the pandemic, approximately 15–21% of infected individuals require treatment, after which the percentage gradually declines. The optimal treatment control minimizes the cost functional for each fractional order, achieving the lowest overall cost at . Table 3 highlights that computations require more iterations as increases. This optimal treatment approach not only decreases the number of infections but also increases the susceptible population for all values of (as shown in Figure 10), signifying its effectiveness in controlling the spread of COVID-19. Additionally, as the number of infectious people declines, the number of people in the treatment class reaches its peak, leading to an increase in recoveries, as shown in Figure 10. Therefore, the strategy successfully decreases the rate of infection and boosts the number of people who recover.

Figure 9.

Optimal control for treatment of infectious individuals and the corresponding cost (Case-1).

Table 3.

Number of iterations required to achieve the minimum cost in case 1 for different fractional-order values of .

Figure 10.

Trajectories of the disease model with and without optimized treatment rate for infected individuals (Case-1).

6.1.2. Case-2: COVID-19 Control Through the Awareness-Only Approach

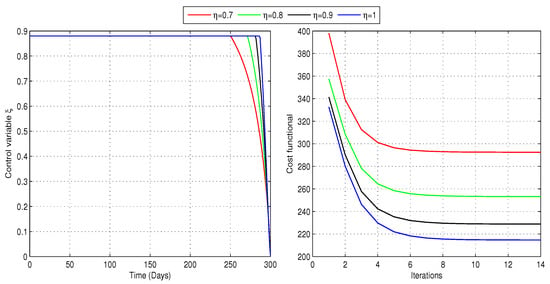

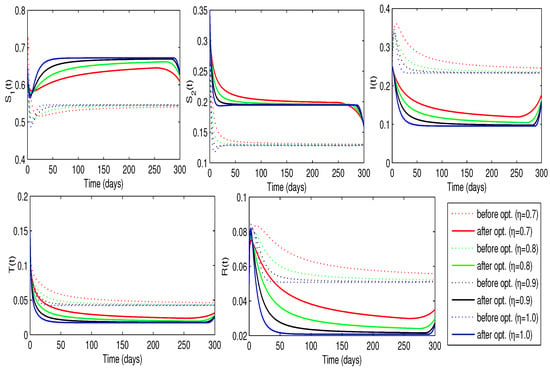

In the second scenario, we address problem (24) to determine the optimal awareness rate while considering the treatment rate as a constant over time. Specifically, we evaluate the cost functional (23) with , , , and . This configuration aims to minimize the number of infected individuals while keeping the cost associated with the control as low as possible. Figure 11 illustrates the solution trajectories for the best awareness rate and the related cost functional for different fractional-order values. We can conclude that raising awareness among nearly of the individuals is essential for achieving optimal disease control. Additionally, the vaccination rate may decrease just after 250 days. The lowest of all the minimum costs was observed when . These results are further summarized in Table 4, which demonstrates that MATLAB R2024a requires between seven and nine iterations to attain the desired tolerance for the selected values of . The optimal value of minimizes the cost functional, leading to a significant decline in the number of infected individuals and an increase in the number of susceptible individuals, as shown in Figure 12. Additionally, the decline in infected cases leads to a slight reduction in the number of individuals receiving treatment.

Figure 11.

Optimal control for the awareness campaigns for people and the associated cost (Case-2). The study recommends maintaining an awareness rate for approximately 250 days, with possible adjustments thereafter.

Table 4.

Number of iterations required to achieve the minimum cost in case-2 for different fractional-order values of .

Figure 12.

Trajectories of the disease model with and without optimized awareness rate for people (Case-2).

6.1.3. Case-3: Implementation of Treatment and Awareness as a Combined Strategy

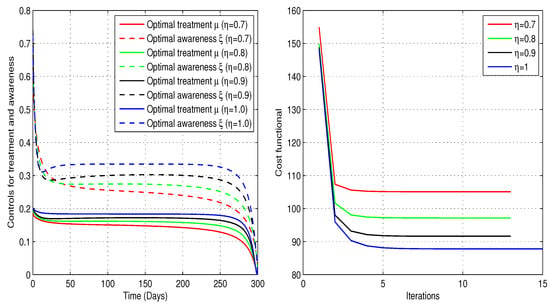

Now, we approximate the optimal treatment rate, , and awareness rate, , that optimize the control problem. By assigning positive values to the weights , the objective is to minimize the number of infected individuals while keeping the overall implementation cost as low as possible. The results, shown in Figure 13, demonstrate that the combined implementation of controls significantly reduces the total cost. We observe a clear need for awareness sessions. Initially, around to of individuals in the group require education at the beginning, but this level of awareness may decline over time. At the same time, only to of the infected individuals require treatment, and this percentage gradually decreases over time. These profiles are illustrated in Table 5. As usual, the smallest minimum cost occurred when . Moreover, implementing both controls simultaneously contributes to reducing the number of infected individuals while increasing the susceptible population, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Fractional optimal controls for the treatment and awareness campaigns, respectively, for infected and individuals alongside corresponding costs (Case-3).

Table 5.

Number of iterations required to achieve the minimum cost in case-3 for different fractional-order values of .

Figure 14.

Trajectories of the disease model with and without optimized treatment and awareness rates (Case-3).

The comparative analysis of the three control strategies demonstrates that implementing early and combined interventions is more effective at suppressing peak infection rates and reducing long-term disease burden than using isolated measures. This finding reflects real-world COVID-19 outcomes, where layered interventions proved more effective than single-policy approaches.

6.1.4. Analysis of Cost Efficacy

To further enhance the analysis, we may include additional explanations and supportive remarks emphasizing the significance of the above findings, their implications, and the reasons behind the observed cost variations. The implementation of optimal treatment and awareness controls, and , notably decreased infection levels and improved recovery outcomes at a lower overall cost in all cases. The iteration counts for the optimal controls and the associated implementation costs are described in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. For each fractional order , Case-1 yields a lower minimum cost for employing the optimal treatment control compared to Case-2 and Case-3, and it also requires fewer optimization iterations, thereby reducing the overall computational cost. Moreover, the reduction in infected cases is greater in Case-1 and Case-3 than in Case-2 for every fractional order. The higher cost of the awareness-based intervention indicates that it requires greater resources to sustain, likely due to the ongoing need for public engagement and information dissemination efforts. Case-3, which combines treatment and awareness strategies, leverages the strengths of both approaches for more comprehensive infection control. In Case-3, the number of iterations required to achieve the combined optimal treatment and awareness controls is almost the same as in Case-2, but overall, it is smaller than in Case-1, indicating a reduced computational effort. Additionally, the implementation costs for different fractional-order values in Case-3 are slightly higher than in Case-1, but significantly lower than in Case-2.

For the proposed model, our findings suggest that using optimal awareness control alone results in an elevated cost compared to considering only treatment or combining both treatment and awareness controls. This higher cost of awareness-based strategy arises from the extensive efforts required to influence public behavior, in contrast to the more direct and immediate effects of treatment interventions. Thus, we conclude that better results can be achieved by using treatment alone or by combining optimal vaccination with treatment, leading to a significant decline in infections at a lower cost. This underscores the value of a multifaceted approach to public health, where integrating multiple strategies not only improves health outcomes but also maximizes cost-effectiveness.

7. Conclusions

In this work, we formulated a fractional-order COVID-19 model utilizing the Atangana-Baleanu derivative to capture complex disease dynamics. Analytical results demonstrated the model’s well-posedness, confirming the existence, uniqueness, positivity, and boundedness of solutions. Additionally, we derived a threshold parameter to describe the equilibrium behavior. We conducted a thorough stability analysis, establishing local and global stability by imposing suitable conditions on the threshold parameter.

Numerical simulations showed that increasing treatment rates and the fractional order significantly reduced infections, with full elimination achievable at treatment coverage for . Incorporating awareness control further reduced infections and treatment needs, with just treatment coverage sufficient to eradicate the disease under high awareness levels. Sensitivity analysis identified contact rates between susceptible and infected individuals as the most influential factors, emphasizing the significance of public engagement, preventive measures, and vaccination promotion.

Optimal control analysis demonstrated that combining time-dependent treatment and awareness strategies is the most effective and cost-efficient strategy for reducing infections. Although awareness efforts alone contribute to controlling the disease, incorporating direct treatment interventions leads to improved health outcomes and more efficient use of resources. These findings underscore the importance of multifaceted intervention strategies in addressing COVID-19 threats and offer actionable insights for public health planning. Furthermore, the cost–efficacy analysis demonstrates that optimal allocation of limited resources can significantly impact outbreak outcomes, offering practical insights for public-health decision-making during pandemic scenarios. These findings emphasize that both timing and intensity of interventions are crucial in controlling COVID-19 transmission.

Although the study has its strengths, it also has certain limitations. The model assumes homogeneous mixing of the population and does not explicitly take into account spatial heterogeneity, demographic variations, or delays in behavior. In addition, the parameter values used in simulations were adopted from previously published studies, which may not fully reflect local or regional dynamics. Future research will address these limitations by extending the model to incorporate delays, stochastic effects, and data-driven parameterization to improve the robustness and applicability of the suggested control strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A., A.I.K.B. and M.R.; Methodology, W.A., M.R. and A.H.M.; Software, A.I.K.B., W.A. and F.H.H.A.M.; Validation, M.R., F.H.H.A.M. and W.A.; Formal analysis, A.I.K.B., A.S.A.E. and W.A.; Investigation, A.I.K.B., M.R. and A.S.A.E.; Resources, W.A.; Writing—original draft preparation, W.A. and A.H.M.; Writing—review and editing, A.I.K.B., W.A., F.H.H.A.M. and M.R.; Visualization, W.A. and A.S.A.E.; Supervision, A.I.K.B., W.A. and M.R.; Project administration, A.I.K.B. and A.S.A.E.; Funding acquisition, A.I.K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU254639].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we do not have commercial or associative and competing interests in connection with the work submitted.

References

- Ivorra, B.; Ferrndez, M.R.; Vela-Prez, M.; Ramos, A. Mathematical modeling of the spread of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) taking into account the undetected infections, The case of China. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2020, 88, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.S.; Azhar, E.I.; Madani, T.A.; Ntoumi, F.; Koch, R.; Dar, O.; Ippolito, G.; McHugh, T.D.; Memish, Z.A.; Drosten, C.; et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel Corona viruses to global health: The latest 2019 novel Coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. 2020, 91, 264–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ndaïrou, F.; Area, I.; Nieto, J.J.; Torres, D.F.M. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of Wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 135, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggriani, N.; Ndii, M.Z.; Amelia, R.; Suryaningrat, W.; Pratama, M.A. A mathematical COVID-19 model considering asymptomatic and symptomatic classes with waning immunity. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVID-19 Epidemiological Update; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: Are we seeing a summer wave? BMJ 2024, 386, q1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, A. Why COVID Surges in the Summer; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Özküse, F.; Yavuz, M.; Şenel, M.T.; Habbireeh, R. Fractional order modelling of omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant containing heart attack effect using real data from the United Kingdom. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 157, 111954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, A.S.; Shaikh, I.N.; Nisar, K.S. A mathematical model of COVID-19 using fractional derivative: Outbreak in India with dynamics of transmission and control. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, S.; Gomersall, C.D.; Fowler, R.A. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 1499–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T. Handbook of COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment; Compiled According to Clinical Experience; The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine: Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Habenom, H.; Aychluh, M.; Suthar, D.; Al-Mdallal, Q.; Purohit, S. Modeling and analysis on the transmission of COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 5323–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, S.; Yatim, S.A.M.; Rafiq, M.; Ahmad, W.; Kamran, A.; Karim, M.F. Treatment and delay control strategy for a nonlinear rift valley fever epidemic model. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 115104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.I.K. Optimal control strategies for sustainable management of Bayoud disease in date palm trees: The role of resistant varieties and treatment. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2026, 477, 117209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, S.; Ackora-Prah, J. A mathematical model of transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) with an underlying condition of diabetes. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2022, 2022, 7984818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, D.; Piazza, F. Analysis and forecast of COVID-19 spreading in China, Italy and France. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 134, 109761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajarmi, A.; Baleanu, D.; Vahid, K.Z.; Mobayen, S. A general fractional formulation and tracking control for immunogenic tumor dynamics. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022, 45, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özköse, F.; Yilmaz, S.; Yavuz, M.; Öztürk, I.; Şenel, M.T.; Bağcı, B.Ş.; Doğan, M.; Önal, Ö. A fractional modeling of tumor-immune system interaction related to lung cancer with real data. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umarov, S. Fractional Calculus and Fractional order operators. In Introduction to Fractional and Pseudo-Differential Equations with Singular Symbols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 121–168. [Google Scholar]

- Magin, R. Fractional calculus in bioengineering. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 32, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, S.M.; Baleanu, D.; Mohammadi, H.; Rezapour, S. On the mathematical model of Rabies by using the fractional Caputo-Fabrizio derivative. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazman, I.; Mishra, M.N.; Alkahtani, B.S.; Goswami, P. Computational analysis of rabies and its solution by applying fractional operator. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 2024, 32, 2340607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndendya, J.Z.; Mwasunda, J.A.; Edward, S.; Shaban, N. A Caputo–Fabrizio fractional-order model with MCMC estimation for rabies transmission dynamics in a multi-host population. Sci. Afr. 2025, 29, e02885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samko, S.G.; Kilbas, A.A.; Marichev, O.I. Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: Theory and Applications; Gordon and Breach: Yverdon, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tassaddiq, A.; Qureshi, S.; Soomro, A.; Arqub, O.A.; Senol, M. Comparative analysis of classical and Caputo models for COVID-19 spread: Vaccination and stability assessment. Fixed Point Theory Algorithms Sci. Eng. 2024, 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleanu, D.; Jajarmi, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Rezapour, S. A new study on the mathematical modelling of human liver with Caputo-Fabrizio fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 134, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Butt, A.I.K.; McKinney, B.A.; Al Nuwairan, M.; Al Mukahal, F.H.H.; Batool, S. A Comparative Analysis of Different Fractional Optimal Control Strategies to Eradicate Bayoud Disease in Date Palm Trees. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: Theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Ullah, R.; Zaman, G.; Alzabut, J. A mathematical model for the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 virus using the Caputo-Fabrizio operator. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 6095–6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uçar, S. Existence and uniqueness results for a smoking model with determination and education in the frame of non-singular derivatives. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. S 2021, 14, 2571–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintunavarat, W.; Turab, A. Mathematical analysis of an extended SEIR model of COVID-19 using the ABC-fractional operator. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 198, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyaha, E.; Jugab, M.L.; Matsebulab, L.M.; Chukwuc, C.W. On the modeling of COVID-19 spread via fractional derivative: A stochastic approach. Math. Model. Comput. Simul. 2023, 15, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, C.T.; Duressa, G.F. Analysis of Atangana-Baleanu fractional-order SEAIR epidemic model with optimal control. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 2021, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçar, E.; Uçar, S.; Evirgen, F.; Özdemir, N. A Fractional SAIDR Model in the Frame of Atangana-Baleanu Derivative. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.M.; Yassen, M.F.; Ahmad, I.; Sunthrayuth, P.; Khan, M.A. A fractional SARS-COV-2 model with Atangana-Baleanu derivative: Application to fourth wave. Fractals 2022, 30, 2240210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Khan, M.A. Modeling the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the dynamics of novel Coronavirus with optimal control analysis with a case study. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, S.; Prah, J.A.; Darkwah, K.F.; Oduro, F.T.; Bonyah, E. Fractional optimal control model of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) disease in Ghana. J. Math. 2023, 2023, 3308529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, B.A.; Bilgehan, B. Optimal control of a fractional order model for the COVID-19 pandemic. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 2021, 144, 110678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Zarin, R.; Humphries, U.W.; Akgül, A.; Saeed, A.; Gul, T. Fractional optimal control of COVID-19 pandemic model with generalized Mittag-Leffler function. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 2021, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, K.N.; Kumar, P.; Erturk, V.S. Projections and fractional dynamics of COVID-19 with optimal control strategies. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Ali, J.; Riaz, M.B.; Awrejcewicz, J. Numerical analysis of a bi-modal COVID-19 SITR model. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufik, M.; Atangana, A. New numerical approximation of fractional derivative with non-local and non-singular kernel: Application to chaotic models. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2017, 132, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Rafiq, M.; Butt, A.I.K.; Ahmad, N.; Ismaeel, T.; Malik, S.; Rabbani, H.G.; Asif, Z. Analytical and numerical explorations of optimal control techniques for the bi-modal dynamics of COVID-19. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 3977–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aychluh, M.; Purohit, S.D.; Agarwal, P.; Suthar, D.L. Atangana–Baleanu derivative-based fractional model of COVID-19 dynamics in Ethiopia. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 2022, 30, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Santra, P.K.; Mahapatra, G.S.; Elsonbaty, A.; Elsadany, A.A. A discrete-time epidemic model for the analysis of transmission of COVID-19 based upon data of epidemiological parameters. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Topics 2022, 231, 3461–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Podlubny, I. Stability of fractional-order nonlinear dynamic systems: Lyapunov direct method and generalized Mittag-Leffler stability. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 59, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleanu, D.; Shekari, P.; Torkzadeh, L.; Ranjbar, H.; Jajarmi, A.; Nouri, K. Stability analysis and system properties of Nipah virus transmission: A fractional calculus case study. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 166, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, J.P. The Stability of Dynamical Systems; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, A.I.K. Atangana-Baleanu Fractional Dynamics of Predictive Whooping Cough Model with Optimal Control Analysis. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumara, R.P.; Santrac, P.K.; Mahapatraa, G.S. Global stability and analysing the sensitivity of parameters of a multiple-susceptible population model of SARS-CoV-2 emphasising vaccination drive. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 203, 741–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, C.T.; Mussa, Y.O.; Duressa, G.F. Optimal control and sensitivity analysis for transmission dynamics of Coronavirus. Results Phys. 2020, 19, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.