Abstract

In plateau and high-altitude areas, freeze-thaw cycles often alter the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of rock, thereby impacting the stability of geotechnical engineering. Acquiring rock samples in these areas for UCS testing is often time-consuming and labor-intensive. This study developed a hybrid model based on the XGBoost algorithm to predict the UCS of rock under freeze-thaw conditions. First, a database was created containing longitudinal wave velocity (Vp), rock porosity (P), rock density (D), freezing temperature (T), number of freeze-thaw cycles (FTCs), and UCS. Four swarm intelligence optimization algorithms—artificial bee colony, Newton–Raphson, particle swarm optimization, and dung beetle optimization—were used to optimize the maximum iterations, depth, and learning rate of the XGBoost model, thereby enhancing model accuracy and developing four hybrid models. The four hybrid models were compared to a single XGBoost model and a random forest (RF) model to evaluate overall performance, and the optimal model was selected. The results demonstrate that all hybrid models outperform the single models. The XGBoost model optimized by the sparrow algorithm (R2 = 0.94, RMSE = 10.10, MAPE = 0.095, MAE = 7.22) performed best in predicting UCS. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were used to assess the marginal contribution of each input variable to the UCS prediction of freeze-thawed rock. This study is expected to provide a reference for predicting the UCS of freeze-thawed rock using machine learning.

1. Introduction

As global climate change intensifies, the freeze-thaw cycle phenomenon is becoming increasingly significant in both nature and engineering practices. Freeze-thawed rock, as a unique geological medium, plays a crucial role in glacier melting, disaster warning, and engineering construction in cold regions. The UCS of freeze-thawed rock is a key parameter reflecting the rock’s mechanical properties, forming the basis for geotechnical engineering design and construction in cold regions. Rapid and accurate determination of UCS in freeze-thawed rock is critical for geotechnical engineering. The traditional method for determining UCS involves conducting uniaxial compression tests in a laboratory [1]. This method must adhere to strict standards, with specific requirements for sampling, specimen processing, and transportation [2]. While highly accurate, this method requires advanced facilities and skilled personnel, and it is economically inefficient and time-consuming.

To overcome the limitations of conventional techniques, researchers have sought to identify the factors affecting the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of freeze-thawed rocks and the specific impacts of these factors on UCS. Momeni and his team investigated the effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the physical and mechanical properties of Alwan granite from western Iran. They found that as the number of freeze-thaw cycles increased, uniaxial compressive strength, tensile strength, dry density, and P-wave velocity decreased [3], while water absorption and porosity increased. They also identified P-wave velocity and tensile strength as key indicators for assessing the effects of freeze-thaw cycles on the physical and mechanical properties of the granite. Kai Si et al. conducted a series of uniaxial compression tests on sandstone subjected to freeze-thaw treatment. The results indicate that FTCs and the lowest freeze-thaw temperature significantly affect rock damage and characteristic stress [4], with FTCs having a more pronounced effect. As the number of FTCs increases and the lowest freeze-thaw temperature decreases, rock damage and characteristic stress also increase [5]. Deng Xiaoping Wang et al. simulated freeze-thaw cycle tests at varying temperature differences (−10 to 10 °C, −15 to 25 °C, −20 to 40 °C) and different cycle times (0, 10, 20, 30). The mechanical parameters of freeze-thawed unloading marble were obtained through uniaxial and triaxial compression tests, and the effects of temperature range, freeze-thaw cycles, and confining pressure on these mechanical properties were analyzed [6]. Another study conducted indoor freeze-thaw cycle and uniaxial compression experiments on yellow sandstone. The results indicate that as the number of FTCs increases, the elastic modulus, peak strength, and wave velocity of yellow sandstone gradually decrease, while peak strain and average porosity increase. Based on the relative change in the energy consumption ratio before and after freeze-thaw, a freeze-thaw failure model was developed [7].

As machine learning and artificial intelligence advance, these technologies are becoming integral to various industries. An intriguing development has emerged in applying machine learning to predict the mechanical properties of rocks subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. In their study, Shengtao Zhou and his colleagues employed five population-based optimization algorithms to fine-tune the kernel size, penalty factor, and insensitive loss coefficient in a support vector regression framework [8]. This approach resulted in the development of five hybrid models designed to predict the uniaxial compressive strength of rock specimens [9]. Jan Kleine Deters et al. proposed a machine learning approach based on data analysis [10]. Mohamed Abdelhedi et al. collected data from freeze-thaw rock research in 16 countries and applied machine learning models, such as random forest, support vector regression, and XGBoost, to predict the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of carbonate rocks. The results indicate that XGBoost performs the best. Mohamed. [11]. Niaz Muhammad Shahani et al. used wet density, saturation (%), dry density, and Brazilian tensile strength (BTS) as inputs and developed six new machine learning (ML) regression models, including mild gradient boosting, support vector machine (SVM), CatBoost [12], random forest (RF) [13], and XGBoost, to predict the elastic modulus of freeze-thawed rock. The results indicate that the XGBoost model outperforms the other developed models in accuracy [14]. Amit Jaiswal et al. collected and prepared 32 rock samples from eight distinct loess hills in the northwestern Himalayas. The researchers performed lithofacies analysis and laboratory tests on each sample to determine its uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) and Brazilian tensile strength (BTS). They also developed machine learning (ML) sequence models—recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [15], gated recurrent units (GRUs) [16], and bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM)—to predict UCS and BTS under freeze-thaw (FT) conditions [17,18]. Table 1 lists some previous studies on machine learning-based UCS prediction, which generally suffer from issues such as limited datasets, single prediction methods, single evaluation metrics, and low prediction accuracy. Although existing research has established the context of ‘algorithm optimization, data expansion, and model innovation’, two key limitations remain. First, there is insufficient focus on characteristic variables. Most studies focus on either rock physical and mechanical parameters (e.g., density and BTS) or freeze-thaw environmental factors. The two core dimensions of ‘freeze-thaw environment and rock physical properties’ have not been systematically integrated, limiting the model’s adaptability to complex freeze-thaw scenarios. Second, the optimization potential of the XGBoost model remains underexplored [19]. Although existing studies confirm its accuracy advantages, most rely on default or simple adjusted parameters without leveraging the global optimization capabilities of swarm intelligence algorithms to enhance model stability. This limits its ability to handle prediction variations under different lithologies and freeze-thaw conditions. In summary, this study uses freezing temperature (°C), freeze-thaw cycles, density (g/cm3), porosity (%), and longitudinal wave velocity (km/s) as features to construct a hybrid model combining XGBoost and a population optimization algorithm to predict the USC of rock.

Table 1.

Existing research finding.

2. Methodology and Indicator

2.1. Data Description

In this study, data from published papers were collected, including 463 sets of freeze-thaw experimental data from different lithologies [27,28,29]. Table 2 provides the detailed sources of the dataset. The relevant characteristics of the data were statistically analyzed, as shown in Table 3. The data are raw experimental results without digital processing, ensuring that changes in loading conditions do not affect the reliability of this study. The dataset is split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Additionally, rigorous five-fold cross-validation (CV) was employed to evaluate the model’s performance and reliability [30,31,32]. This paper synthesizes multiple research efforts that explore the factors influencing the compressive strength of rocks exposed to freeze-thaw conditions. The study focuses on two main factors, namely ‘freeze-thaw environmental conditions’ and ‘intrinsic rock properties’. Key input parameters include longitudinal wave velocity (Vp), rock porosity (P), rock density (D), freezing temperature (T), and the number of freeze-thaw cycles (FTCs). The target outcome of the model is the UCS of rocks subjected to alternating freeze-thaw conditions.

Table 2.

Data source.

Table 3.

Dataset characteristics.

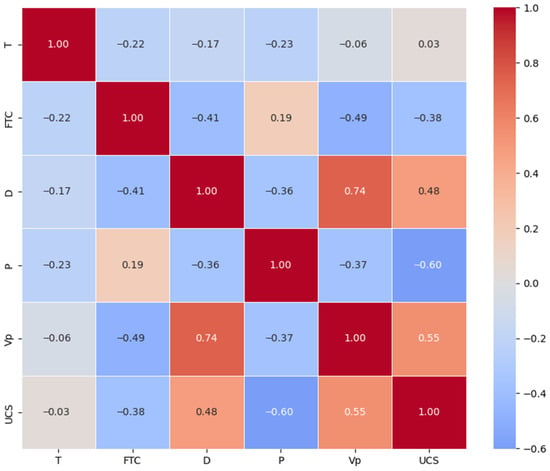

The Pearson correlation coefficient is a key tool for assessing the relationship between variables and is a fundamental measure in statistical analysis [34]. It provides a robust method for quantifying the strength of a linear relationship between two variables, ensuring an accurate measurement of monotonicity. As shown in Figure 1, each input variable exhibits a high correlation with uniaxial compressive strength, supporting their suitability as model inputs. The data were normalized to eliminate the adverse effects of outlier samples.

Figure 1.

Pearson correlation coefficient matrix.

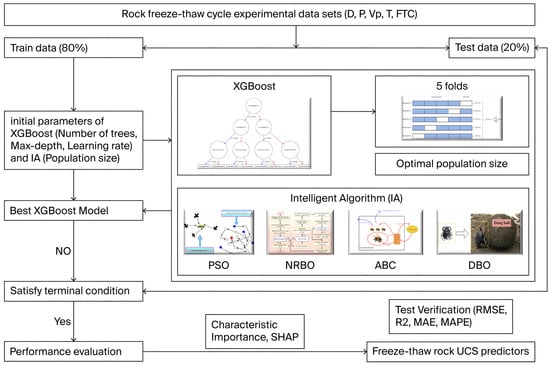

2.2. Workflow

The study used machine learning algorithms to predict the uniaxial compressive strength of freeze-thawed rock based on available data. The process and sequence are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Freeze-thaw rock prediction flowchart.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

R2 is the coefficient of determination (goodness of fit), with values ranging from 0 to 1. A larger value indicates a better fit. RMSE stands for root mean square error [35]. Smaller RMSE values indicate better model prediction performance and greater sensitivity to outliers. The MAPE (mean absolute percentage error) ranges from 0 to +. A MAPE of 0% represents a perfect model, while a MAPE greater than 100% indicates a poor model [36]. The MAE (mean absolute error) represents the average of the model’s prediction errors. Smaller MAE values indicate better model prediction accuracy. The calculation methods for the evaluation indices are as follows [37]:

In the formula above, represents the predicted value, represents the true value, represents the average of the true values, and is the number of samples.

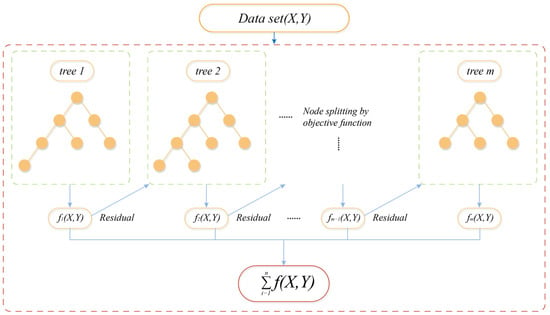

2.4. Extreme Gradient Boosting Model

XGBoost is a widely used decision tree algorithm in machine learning. It is commonly used for both classification and regression tasks because it is computationally efficient, produces interpretable results, and handles missing data effectively. However, like any tool, it has its limitations. It is known to be inconsistent, sensitive to data distribution, and prone to overfitting, and may not generalize well, limiting its practical applications [38]. The details of the algorithm are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

XGBoost schematic diagram.

XGBoost combines multiple weak predictors into a powerful predictive model that utilizes parallel processing capabilities. Due to its excellent performance in both classification and regression tasks, XGBoost has become a key tool in data mining and predictive analytics. The model is additive and constructed from multiple base models [39]. Let the tree model being refined during the t-th iteration be denoted as , structured as follows:

denotes the predicted value for sample after the -th iteration; represents the number of decision trees; denotes the input data for the -th sample; denotes the -th decision tree; and represents the sample space of the regression tree.

A model’s predictive performance depends on the balance between its bias and variance. The loss function quantifies the discrepancy between the model’s predictions and the actual values. If the variance is too high, a regularization term is added to the objective function to prevent overfitting. The objective function combines the loss function and regularization term to control the model’s complexity. The objective function is mathematically expressed as

In the formula, represents the loss function, where is the actual value of the -th sample and is the predicted value. Overall, it represents the model complexity of trees (regularization term). The number of leaf nodes is represented by , which denotes the L2 norm of the leaf weights, and and represent the penalty coefficients.

2.5. Optimistic Algorithm

This study combines XGBoost with 10 novel optimization algorithms, including the Newton–Raphson optimization algorithm (NRBO), gray wolf optimization algorithm (GWO) [40], artificial bee colony optimization algorithm (ABC), particle swarm optimization algorithm (PSO), goose optimization algorithm (GOOSE), and crown porcupine optimization algorithm (CPO), to predict the USC of freeze-thaw rock using MATLAB 2023a. Table 4 presents the prediction performance of the various optimization algorithms. Based on the performance of each algorithm, the particle swarm optimization algorithm (PSO), artificial bee colony optimization algorithm (ABC), Newton–Raphson optimization algorithm (NRBO), and dung beetle optimization algorithm (DBO) were selected as the optimization algorithms for this prediction.

Table 4.

Optimization algorithm performance.

2.5.1. Newton–Raphson Optimization Algorithm

NRBO is a novel metaheuristic algorithm. NRBO explores the search domain using multiple vector sets and two operators (NRSR and TAO) and applies NRM to identify the search region, thereby defining the search path. The core algorithm consists of three components, namely (1) population initialization (generating a random population), (2) the Newton–Raphson search rule (NRSR) (enhancing the population’s precision in exploring the feasible area and pinpointing optimal locations), and (3) a trap avoidance operation (TAO) (enhancing the effectiveness of NRBO in solving real-world problems) [41].

Here, denotes the position in the -th dimension of the -th population, and randn represents a random number drawn from a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and variance of 1.

2.5.2. Particle Swarm Optimization

PSO represents an optimization approach leveraging swarm intelligence through avian and aquatic foraging patterns. PSO finds the optimal solution by moving a set of ‘particles’ (representing potential solutions) through the multidimensional search space. Each particle has its own position and velocity, gradually moving towards the optimal solution. PSO is commonly used to solve complex optimization problems, offering global search capabilities and high computational efficiency. The following formula can be used to update each particle’s velocity and position during iteration:

Here, denotes the particle’s velocity in dimension , denotes the particle’s position in dimension , represents the inertia weight, and are the weights for individual and global optimization learning, respectively, and and are random numbers uniformly distributed in the interval [1, 2].

2.5.3. Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm

ABC is an innovative global optimization technique based on swarm intelligence, inspired by the honey-gathering behavior of bee colonies. The algorithm mirrors the natural division of labor in a beehive, consisting of three groups of bees, including employed bees, observing bees, and reconnaissance bees. In search optimization, the algorithm’s pursuit of the global solution is akin to a bee colony’s search for the most abundant nectar-rich flower patch [42].

Here, represents the position of forage source in the -th dimension, and denote the upper and lower bounds of the search space, is a new nectar source generated near the hired forage source through a local search, and is a random number in the range [−1, 1].

2.5.4. Dung Beetle Optimization Algorithm

The dung beetle optimizer (DBO) is an innovative swarm intelligence technique inspired by the behavioral patterns of dung beetles, including ball-rolling, dancing, foraging, stealing, and reproduction. This algorithm strikes a balance between global exploration and local refinement, ensuring rapid convergence, high precision, and effectiveness in solving complex optimization problems. Similarly to how dung beetles use the sun for navigation, we hypothesize that the intensity of their light source influences their trajectory [43]. As the dung beetle rolls its ball, its position is updated continuously, as represented by the following equation:

When the troll encounters obstacles and cannot proceed, its position is updated by simulating the dancing behavior using the tangent function to find a new route. The location update of the thorn beetle along the new route is given by

Here, denotes the iteration count, represents the position of the i-th dung beetle at the -th iteration, is the perturbation coefficient, is a random number in the range (0, 1), takes values of −1 or 1, denotes the global worst position, and simulates changes in light intensity. The other term is the deflection angle, which belongs to the range [0, ]. Additionally, there is a variable that represents the difference between the position of the i-th beetle at iteration and its position at iteration .

2.6. Hyperparameter Tuning of the Model

This study employs a population-based optimization technique to fine-tune three key parameters of the XGBoost model, namely the number of trees, tree depth, and learning rate. Although increasing the number of iterations generally improves model performance, it can also lead to overfitting. Increasing tree depth adds complexity to the model. The learning rate controls the size of each adjustment during the iterative process. A learning rate that is too low may lead to overfitting, while one that is too high can prevent convergence. The algorithm efficiently searches for optimal solutions within the model’s solution space, avoiding the time-consuming and inefficient drawbacks of traditional grid search methods [44,45]. The dimensions of the search space are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hyperparameter search range and optimal combination.

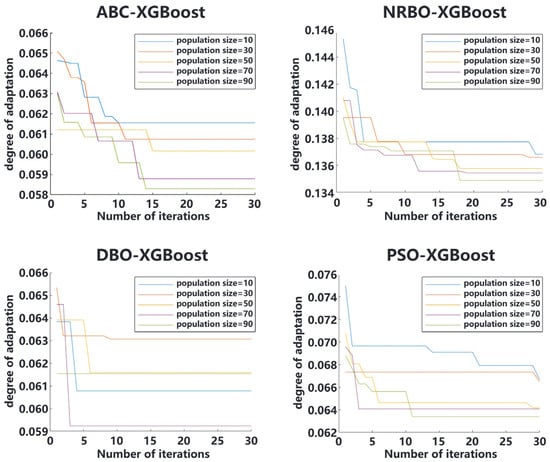

The population size of the optimization algorithm influences the model’s performance.

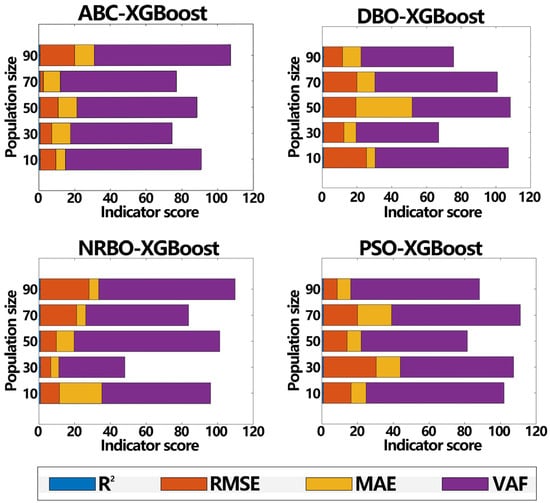

A narrow population may impede convergence to the optimal solution [46]. Conversely, expanding the population may not always improve predictive accuracy. In this study, populations of sizes 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90 were tested, and each mixed model was evaluated for these population sizes. The adaptability curve (Figure 4) and performance score (Figure 5) for each population size were then obtained. The optimal population size for each model was determined. The optimal population sizes for the ABC-XGBoost, NRBO-XGBoost, DBO-XGBoost, and PSO-XGBoost hybrid models are 70, 30, 30, and 50, respectively.

Figure 4.

Hyperparameter optimization curves of each composite model under different population numbers.

Figure 5.

The performance of each hybrid model under different population numbers.

3. Results and Discussion

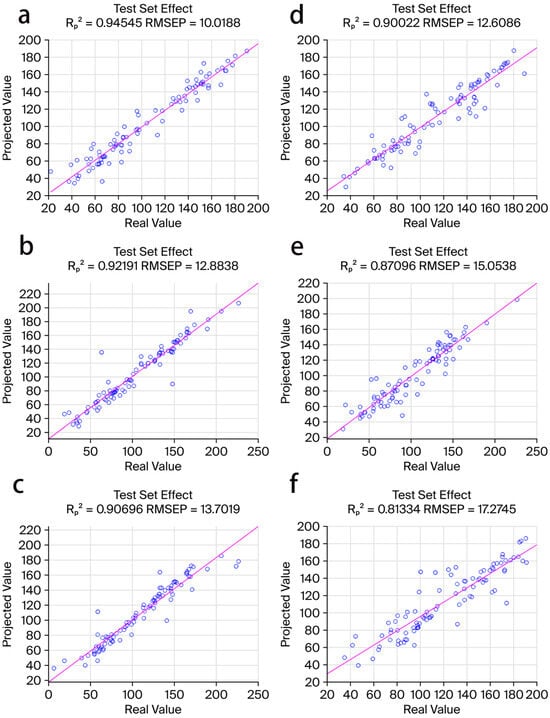

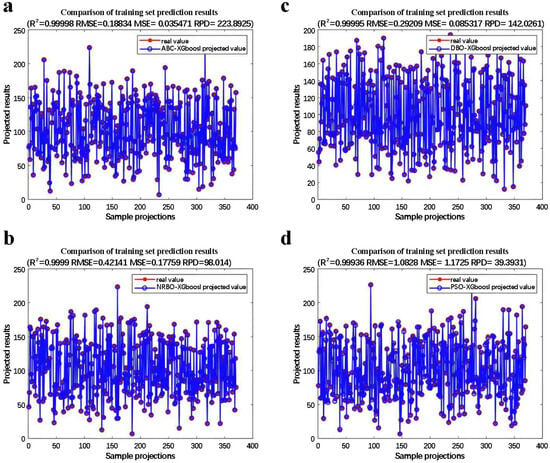

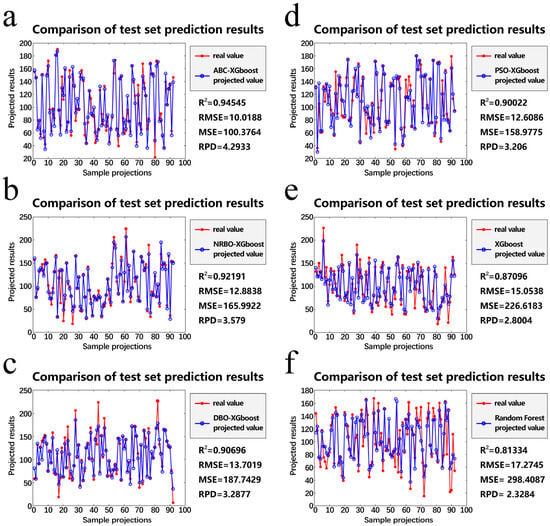

This study uses the training set to train the prediction model and the test set to evaluate its performance. Figure 6 illustrates the performance of the single model versus the hybrid model on the test set. Figure 7 presents a comparison of the prediction results for each hybrid model on the training set. Figure 8 shows a comparison of the prediction results between single and hybrid models on the test set. Comparing the performance of the four hybrid models on both the training and test sets, the prediction results on the training set are excellent, with reaching 0.99 and RMSE values between 10 and 20. On the test set, although there is a gap between the prediction results of the four hybrid models, they all perform well. The four hybrid models perform excellently on both the test and training sets, demonstrating high generalization ability and robustness. Although the hybrid models combine optimization algorithms and the XGBoost model, common failure modes may still arise. Overfitting is prone to occur when model complexity (such as the number of trees, depth, etc.) is too high and the training data is insufficient. When extreme conditions in the dataset (such as extremely high freeze-thaw cycles or temperatures) are not supported by enough training samples, the model struggles to learn the underlying patterns, leading to significant prediction errors.

Figure 6.

Single and mixed model test set performance. (a): ABC-XGBoost; (b): NRBO-XGBoost; (c): DBO-XGBoost; (d): PSO-XGBoost; (e): XGBoost; (f): RF.

Figure 7.

The prediction results of the hybrid model on the training set. (a): ABC-XGBoost; (b): NRBO-XGBoost; (c): DBO-XGBoost; (d): PSO-XGBoost.

Figure 8.

Comparison of prediction results of single and mixed models. (a): ABC-XGBoost; (b): NRBO-XGBoost; (c): DBO-XGBoost; (d): PSO-XGBoost; (e): XGBoost; (f): RF.

To further compare and analyze the superiority of the hybrid model’s performance, we compare the predicted values of the hybrid models with those of the single XGBoost and RF models. Figure 7 presents the prediction results and real value bar charts for the hybrid and single models. In the four hybrid models, most of the red dots (true values) are very close to the blue dots (predicted values), while the points for the two single models are more scattered. The diagram clearly shows that the prediction accuracy of RF is the lowest. The primary reason may be that noise in the data causes overfitting. The prediction results of the single machine learning models are unsatisfactory. The model has not been optimized, limiting its predictive capability. The hybrid model performs better. This demonstrates that using intelligent algorithms to optimize machine learning models can improve prediction accuracy. Table 6 presents the evaluation metrics for both single and hybrid models based on the prediction results from the test set (Figure 6) and ranks each model according to its running time and performance metrics. The study draws the following conclusions: 1. The prediction performance of the hybrid model is superior to that of the single model. 2. Among the four hybrid models, ABC-XGBoost (R2 = 0.94; RMSE = 10.10; MAPE = 0.095; MAE = 7.22) performs the best. The models are ranked by prediction performance from highest to lowest as follows: ABC-XGBoost > NRBO-XGBoost > PSO-XGBoost > DBO-XGBoost > XGBoost > RF.

Table 6.

Model performance scores.

4. Sensitivity Analysis

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation) can interpret the outcomes of any machine learning model. It links optimal credit allocation with local interpretation, explaining the ‘black box model’ at both the global and local levels. It is currently the most effective method for interpreting machine learning models. To evaluate the sensitivity of various freeze-thaw factors and rock properties in predicting the UCS of freeze-thaw rock, this study uses SHAP interpretation model results to analyze the contribution of different features to the predictions.

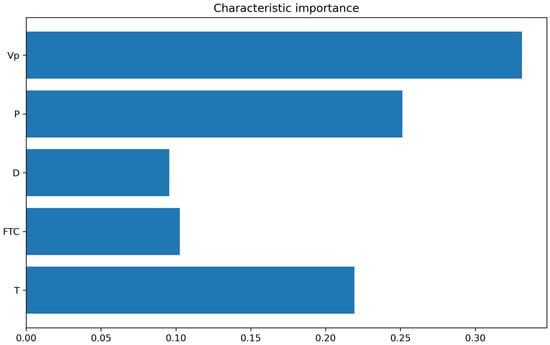

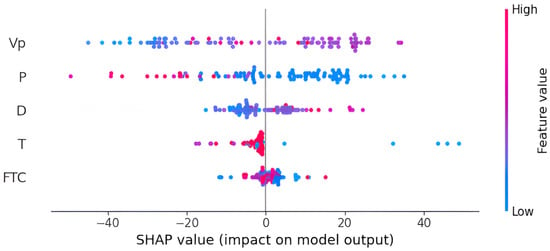

From the global importance diagram (Figure 9) and the model’s global interpretation diagram (Figure 10), the sensitivity indices of each input variable ranked in descending order are as follows: longitudinal wave velocity > porosity > freezing temperature > density > number of freeze-thaw cycles. Higher and values are associated with positive SHAP values, indicating a positive impact on UCS. Higher values indicate that the rock is relatively hard. Higher values suggest that the rock contains more minerals or has fewer pores, enabling it to withstand greater pressure. High values of P, T, and FTC are in the negative SHAP value region, while low values are in the positive SHAP value region, indicating a negative influence on UCS. Higher P values typically indicate more voids in the rock, leading to a looser structure. Higher T values cause greater damage to UCS. As FTC increases, the rock undergoes repeated expansion and contraction, leading to structural damage.

Figure 9.

Global feature importance map.

Figure 10.

Global interpretation of the model.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically analyzes the prediction mechanism of rock uniaxial compressive strength under freeze-thaw cycles by constructing a hybrid model combining XGBoost with intelligent optimization algorithms (ABC, PSO, DBO, NRBO). The main conclusions are as follows: the hybrid model significantly improves prediction accuracy. Among these, ABC-XGBoost performs best (R2 = 0.94, RMSE = 10.10), with higher fitting accuracy and generalization ability than the single XGBoost model (R2 = 0.88, RMSE = 13.85 MPa) and the random forest (RF) model (R2 = 0.81, RMSE = 17.27). The intelligent optimization algorithm effectively balances model bias and variance through global search, demonstrating the feasibility of the algorithm combination.

The hybrid model proposed in this study offers an efficient and cost-effective UCS prediction method for cold region projects, such as freeze-thaw disaster warning and rock engineering design. By integrating the model into a field monitoring system, engineers can obtain the UCS value of rock under freeze-thaw conditions in real time, enabling disaster prediction. In the absence of sufficient experimental data, the simulation of various freeze-thaw conditions and lithology changes, combined with UCS prediction model results and on-site experimental data, allow for the optimization of engineering design, improving safety and efficiency.

However, there are also some limitations. The model’s performance may be limited by the training data, especially when environmental conditions change, potentially leading to performance degradation. To improve model robustness and generalization, the dataset can be expanded in the future by collecting more experimental data from different regions, rock types, and freeze-thaw cycles. As a tree-based ensemble learning method, XGBoost effectively handles nonlinear relationships between features, but it has limitations when addressing more complex problems. Combining deep learning architectures such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) can enhance performance, particularly for time series data or complex nonlinear relationships. The focus has been on the impact of a single variable (such as FTC or D), neglecting the multi-factor interactions in the freeze-thaw process. In the future, more complex multi-field coupling experiments can be designed to simulate the mechanical properties of rock under various freeze-thaw environments. These experiments would simultaneously consider factors such as freeze-thaw cycles, temperature gradients, rock moisture content, and stress conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.; Methodology, S.G. and X.X.; Investigation, S.G.; Data curation, S.G. and X.X.; Writing—original draft, S.G.; Writing—review and editing, C.W.; Supervision, Z.G.; Funding acquisition, Z.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jilin Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 20250203150SF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hou, C.; Jin, X.; He, J.; Li, H. Experimental studies on the pore structure and mechanical properties of anhydrite rock under freeze-thaw cycles. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, A.; Abdilor, Y.; Khanlari, G.R.; Heidari, M.; Sepahi, A.A. The effect of freeze-thaw cycles on physical and mechanical properties of granitoid hard rocks. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2016, 75, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.T.; Jing, H.W.; Su, H.J.; Yin, Q.; Du, M.R.; Han, G.S. Physical and mechanical properties of sandstone containing a single fissure after exposure to high temperatures. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.R., Jr.; Boult, T.E.; Wainer, J.; Rocha, A. Open-Set Support Vector Machines. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Syst. 2022, 52, 3785–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, K.; Cui, Z.D.; Peng, R.D.; Zhao, L.L.; Zhao, Y. Crack Propagation Process and Seismogenic Mechanisms of Rock Due to the Influence of Freezing and Thawing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.P.; Wang, L.H.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, H.B.; Fu, Y.T.; Qin, S.F. Mechanical properties and damage modeling of unloaded marble under freezing and thawing with different temperature ranges. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 218, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Jin, J.C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, W.W.; Yang, X.X.; Li, W.T. Study on a Damage Model and Uniaxial Compression Simulation Method of Frozen-Thawed Rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Wang, X.L.; Lei, F. Data-driven multinomial random forest: A new random forest variant with strong consistency. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.T.; Zhang, Z.X.; Luo, X.D.; Huang, Y.F.; Yu, Z.; Yang, X.W. Predicting dynamic compressive strength of frozen-thawed rocks by characteristic impedance and data-driven methods. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 2591–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine Deters, J.; Zalakeviciute, R.; Gonzalez, M.; Rybarczyk, Y. Modeling PM2.5 Urban Pollution Using Machine Learning and Selected Meteorological Parameters. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2017, 2017, 5106045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhedi, M.; Jabbar, R.; Ben Said, A.; Fetais, N.; Abbes, C. Machine learning for prediction of the uniaxial compressive strength within carbonate rocks. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, F.E.; Xu, Y.; Iqbal, M.; Javed, M.F.; Jamhiri, B. Predictive modeling of swell-strength of expansive soils using artificial intelligence approaches: ANN, ANFIS and GEP. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsekler, M.C.E.; Qazi, A.; Alalami, M.A.; Ellahham, S.; Al, O. Evaluation of patient safety culture using a random forest algorithm. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 204, 107186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahani, N.M.; Zheng, X.G.; Guo, X.W.; Wei, X. Machine Learning-Based Intelligent Prediction of Elastic Modulus of Rocks at Thar Coalfield. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šíma, J. Subrecursive neural networks. Neural Netw. 2019, 116, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Y.J.; Yagiz, S.; Laouafa, F. An intelligent procedure for updating deformation prediction of braced excavation in clay using gated recurrent unit neural networks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 1485–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Sabri, M.S.; Verma, A.K.; Sardana, S.; Singh, T.N. Prediction of UCS and BTS under freeze-thaw conditions in the NW himalayan rock mass using petrographic analysis and laboratory testing. Quat. Sci. Adv. 2024, 15, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N.E.; Bansal, R.C.; Ismail, A.A.A.; Elnady, A.; Hasan, S. A cohesive structure of Bi-directional long-short-term memory (BiLSTM)—GRU for predicting hourly solar radiation. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y. State-of-the-art review of machine learning and optimization algorithms applications in environmental effects of blasting. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceryan, N.; Samui, P. Application of soft computing methods in predicting uniaxial compressive strength of the volcanic rocks with different weathering degree. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Sy, T. Optimized gradient boosting models and reliability analysis for rock stiffness C13. J. Appl. Geophys. 2024, 230, 105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowida, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Gamal, H. Unconfined compressive strength (UCS) prediction in real-time while drilling using artificial intelligence tools. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 8043–8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, B.; Mohammadi, S.D. Prediction of Uniaxial Compressive Strength and Elastic Modulus of Migmatites by Microstructural Characteristics Using Artificial Neural Networks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 5617–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Mohamad, E.T.; Faradonbeh, R.S.; Jahed Armaghani, D.; Ghoraba, S. Rock strength assessment based on regression tree technique. Eng. Comput. 2016, 32, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhedi, M. Prediction of uniaxial compressive strength of carbonate rocks and cement mortar using artificial neural network and multiple linear regressions. Acta Geodyn. Et Geomater. 2020, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymen, A.; Mengüç, E.C. Comparative evaluation of different statistical tools for the prediction of uniaxial compressive strength of rocks. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wu, S.; Song, J. Pore characteristics and constitutive model of constrained granite under freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C. Research on the predictability of rock strength under freeze-thaw cycles—A hybrid model of SHAP-IPOA-XGBoost. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Sardana, S.; Jaiswal, A. Study of Freeze-thaw Induced Damage Characteristic for Himalayan Schist. J. Geol. Soc. India 2023, 99, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J.F.; Fong, M.H.; Roh, J.; Tu, Z.K.; Bradshaw, J.; Coley, C.W. Reproducing Reaction Mechanisms with Machine-Learning Models Trained on a Large-Scale Mechanistic Dataset. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202411296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, F.; van Rijn, J.N. Fast and Informative Model Selection Using Learning Curve Cross-Validation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 9669–9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, C.; Dai, X.G.; Xiong, X. Research on mining land subsidence by intelligent hybrid model based on gradient boosting with categorical features support algorithm. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Influence of Freeze–Thaw Weathering on the Mechanical Properties of Huashan Granite Strength. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 4741–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Zheng, N.N. A Novel Fractal Image Compression Scheme with Block Classification and Sorting Based on Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 3690–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsangou, J.C.; Kenfack, J.; Nzotcha, U.; Ekam, P.S.N.; Voufo, J.; Tamo, T.T. Explaining household electricity consumption using quantile regression, decision tree and artificial neural network. Energy 2022, 250, 123856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugume, I.; Basalirwa, C.; Waiswa, D.; Reuder, J.; Mesquita, M.D.S.; Tao, S.L.; Ngailo, T.J. Comparison of Parametric and Nonparametric Methods for Analyzing the Bias of a Numerical Model. Model. Simul. Eng. 2016, 2016, 7530759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, N.M.; Zain, A.M.; Sallehuddin, R.; Shayfull, Z.; Yusoff, Y. Recent studies on optimisation method of Grey Wolf Optimiser (GWO): A review (2014–2017). Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 2651–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Q.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Fathipour-Azar, H. Data-driven estimation of joint roughness coefficient. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Jolai, F. Lion Optimization Algorithm (LOA): A nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2016, 3, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, R.; Premkumar, M.; Jangir, P. Newton-Raphson-based optimizer: A new population-based metaheuristic algorithm for continuous optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajevic, I.; Tuba, M. An upgraded artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm for constrained optimization problems. J. Intell. Manuf. 2013, 24, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.K.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, Z.H.; Wang, Y. Relationship between rock uniaxial compressive strength and digital core drilling parameters and its forecast method. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezoulas, V.; Nowakowska, K.; Kazmierski, J.; Fotiadis, D.; Sakellarios, A. Prediction of depression among patients with cardiovascular disease scheduled cardiac surgery using an Al-empowered pipeline. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cai, D.; Gu, S.; Jiang, N.; Li, S. Compressive strength prediction of sleeve grouting materials in prefabricated structures using hybrid optimized XGBoost models. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 476, 141319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agushaka, J.O.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Alharbi, S.K.; Khalifa, H.A. Efficient Initialization Methods for Population-Based Metaheuristic Algorithms: A Comparative Study. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 1727–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).