Abstract

Tornado occurrence and detection are well established in mesoscale meteorology, yet the application of deep learning (DL) to radar-based tornado detection remains nascent and under-validated. This study benchmarks DL approaches on TorNet, a curated dataset of full-resolution, polarimetric Weather Surveillance Radar-1988 Doppler (WSR-88D) radar volumes. We evaluate three canonical architectures (e.g., CNN, VGG19, and Xception) under five optimizers and assess the effect of replacing conventional MLP heads with Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN) layers. To address severe class imbalance and label noise, we implement radar-aware preprocessing and augmentation, temporal splits, and recall-sensitive training. Models are compared using accuracy, precision, recall, and ROC-AUC. Results show that KAN-augmented variants generally converge faster and deliver higher rare-event sensitivity and discriminative power than their baselines, with Adam and RMSprop providing the most stable training and Lion showing architecture-dependent gains. We contribute (i) a reproducible baseline suite for TorNet, (ii) evidence on the conditions under which KAN integration improves tornado detection, and (iii) practical guidance on optimizer–architecture choices for rare-event forecasting with weather radar.

1. Introduction

Despite the advances in radar-based forecasting and the integration of machine learning (ML) models, tornado prediction remains a persistent and complex challenge [1]. Tornadoes inflict catastrophic devastation, posing immediate and severe threats to public safety through their immense power to cause widespread injuries and fatalities, often attributed to flying debris and structural collapse [2,3]. Critical infrastructure, including residential areas, essential public services, and vital transportation networks, is frequently obliterated or severely damaged, leading to long-term disruptions in community functioning and resource accessibility [4]. The economic impact is profound, encompassing billions in property damage, agricultural losses, business interruptions, and extensive rebuilding costs that can cripple local economies for extended periods [5,6]. These pervasive and multifaceted consequences unequivocally highlight the urgent necessity for continuous enhancement and broader implementation of early warning systems, as their ability to provide timely and accurate alerts is critical for safeguarding lives, mitigating injuries, and protecting assets against these formidable natural disasters [7].

Current tornado detection methods, predominantly relying on Doppler radar, face significant limitations that can compromise public safety. While Doppler radar excels at identifying rotation within storms, it often detects mesocyclones aloft rather than direct confirmation of a tornado on the ground, leading to potential delays in warning issuance or, conversely, false alarms when rotation does not translate to a surface tornado [2,3]. Factors such as radar beam height increasing with distance, terrain obstruction, and the absence of clear atmospheric signatures can further hinder accurate and timely detection, especially for weaker or rapidly developing tornadoes [5,6]. These inherent limitations mean that warning systems can suffer from either critical delay, reducing the precious lead time for individuals to seek shelter and directly increasing the risk of fatalities and injuries, or an excessive number of false alarms. False alarms, in turn, erode public trust and can lead to a dangerous “cry wolf” effect, where individuals become desensitized and less likely to respond appropriately to genuine threats, thus creating equally life-threatening situations when actual tornadoes strike [8].

The prediction of rare, high-impact meteorological events poses significant challenges due to their infrequent occurrence and the complex atmospheric dynamics involved. The inherently low frequency of phenomena such as devastating tornadoes, extreme hailstorms, or flash floods severely limits the availability of historical data needed to train and validate robust predictive models, leading to greater statistical uncertainty in forecasts [9]. These events often result from intricate, nonlinear interactions of atmospheric variables that occur at fine spatial and temporal scales, which current observational networks and numerical weather prediction (NWP) models struggle to resolve accurately and in a timely manner [10]. Consequently, forecasters often grapple with short lead times, high uncertainty, and the difficulty of distinguishing between conditions that could produce such an event and those that will highlight the persistent struggle to bridge the gap between model capabilities and the precise, localized warnings necessary for public safety [11].

Several factors contribute to this difficulty. First, tornadoes are exceptionally rare events within the vast corpus of radar observations, creating a highly imbalanced classification problem. This imbalance poses significant difficulties for both model training and evaluation, often resulting in biased classifiers that underperform on the rare event (tornadic) classification. Second, false positives arise when non-tornadic storms produce radar features (e.g., rotation signatures) that resemble tornadic signatures. These “hard negatives” degrade the classifier’s precision and necessitate sophisticated discriminative models. Third, many tornadoes are short-lived and may not coincide precisely with radar scan intervals, leading to label uncertainty and potential misclassification of genuine tornadic events as negatives. Such label noise further complicates supervised learning approaches. Lastly, although ML models have demonstrated performance improvements over traditional radar detection algorithms, the gains remain modest. A recently released benchmark dataset, TorNet, provides standardized, high-resolution, and temporally segmented radar observations, enabling the development and rigorous evaluation of tornado detection and forecasting models.

Advances in deep-learning-based radar analysis offer a transformative potential to significantly reduce warning lead times and enhance detection accuracy for severe weather phenomena, thereby directly bolstering disaster preparedness and mitigation efforts. Unlike traditional algorithms, deep learning models can be trained on vast datasets of radar imagery, meteorological observations, and ground-truth reports to identify subtle, complex, and evolving atmospheric patterns indicative of tornadic activity or other high-impact events that might be overlooked by human forecasters or simpler detection methods [12]. This capability allows for more rapid and precise identification of developing threats, differentiating between benign rotation and actual tornado signatures, and even predicting the onset or cessation of severe weather with greater confidence [13]. By providing earlier and more reliable warnings, communities gain critical minutes to implement safety protocols, activate emergency response, and ensure public evacuation or sheltering, ultimately leading to a reduction in fatalities, injuries, and property damage [14].

Building on this benchmark tornado forecasting dataset, this work presents a series of fine-tuning techniques and examines the effectiveness of several deep learning (DL) architectures in tornado prediction to improve real-time tornado forecasting.

In the next section we present the related literature that contextualizes the research by reviewing the existing tornado detection methods, discussing the challenges of rare event prediction, and identifying the specific research gap addressed by the study. Following this, Section 3 provides a detailed description of the TorNet dataset’s characteristics and elaborates on the six deep learning architectures (Vanilla CNN, VGG19, and Xception, each with and without KAN layers) utilized in the comparative analysis. Section 4 details the experimental setup, including the training strategies, the implementation of radar-specific data augmentation and filtering techniques, the various optimizers employed, and the performance metrics used for evaluation. Subsequently, Section 5 and Section 6 present a comprehensive analysis of the models’ performance, comparing baseline results with those obtained after advanced preprocessing, discussing the impact of KAN integration, analyzing precision and recall improvements, and evaluating the distinct trade-offs of different optimizers. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the study’s significant contributions, such as the efficacy of KAN layers and the improved data conditioning pipeline, discusses implications for disaster preparedness, acknowledges limitations, and suggests future research directions.

2. Related Literature

2.1. Tornado Detection

Tornado detection remains one of the most technically and operationally challenging tasks in meteorology due to the rarity, short duration, and structural complexity of tornado events. Traditional detection methods have predominantly relied on rule-based algorithms applied to radar data, such as the Tornado Vortex Signature (TVS) [15], the Mesocyclone Detection Algorithm (MDA) [16], and the Tornadic Debris Signature (TDS) [16]. While these approaches have been operationalized through the Weather Surveillance Radar-1988 Doppler (WSR-88D) systems and provide valuable insights into storm-scale rotation and debris detection [17,18], they often suffer from high false alarm rates and reduced sensitivity to weak, short-lived tornadoes, particularly those lacking clear radar reflectivity or debris signals.

In response to these limitations, researchers have increasingly adopted AI and ML approaches to improve tornado detection and early warning systems. Early models integrated diverse inputs (e.g., numerical weather prediction (NWP) outputs, satellite observations, and radar data) into statistical classifiers like Bayesian networks [19,20]. More recent efforts have applied ensemble-based machine learning techniques such as Random Forest and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) to enhance detection accuracy and robustness [21,22,23]. These models have demonstrated improved predictive performance, particularly in distinguishing tornadic versus non-tornadic storm environments. However, reproducibility and generalizability remain major barriers due to the absence of standardized, high-resolution, and publicly accessible benchmark datasets.

To address this gap [1] introduced TorNet, a comprehensive benchmark dataset specifically designed for ML-based tornado detection. TorNet comprises over 200,000 full-resolution polarimetric radar image samples from WSR-88D systems, spanning nine years, from August 2013 to August 2022, of confirmed and warned tornado events across the continental United States. Critically, TorNet categorizes events into three well-defined classes: (1) confirmed tornadoes, (2) tornado warnings without verification, and (3) non-tornadic storm cells, providing a realistic representation of operational forecasting conditions. This nuanced data stratification supports both the detection of true tornadic events and the reduction in false alarms, addressing the severe class imbalance that characterizes operational datasets, where true tornado occurrences represent only a small minority of radar scans [24,25]. In the following section, we will look into predicting tornadoes as a rare event detection problem.

2.2. Rare Event Detection

Rare event detection is a critical yet challenging task within the supervised ML domain, especially relevant to high-stakes applications such as tornado forecasting. Tornadoes exemplify rare events due to their low occurrence frequency combined with high-impact consequences. These events typically have brief lifespans, rapid onset, and intricate meteorological signatures, complicating accurate and timely detection [1].

As outlined by Carreño, Inza, and [26], rare event detection can be framed as a supervised classification task where the event of interest (the “rare” class) is significantly underrepresented compared to the majority (“normal” class). Such scenarios typically feature binary class labeling (rare vs. normal), substantial class imbalance, and pronounced label noise or uncertainty. This extreme class imbalance often leads to poor model sensitivity (recall) and biased learning behavior favoring the majority class [27]. Unlike unsupervised anomaly or novelty detection methods, supervised rare event classification leverages historical labeled data to train models capable of discriminating between rare and normal classes.

Temporal dependency is another critical consideration. According to [28], time series classification underpins rare event detection across various domains, including predictive maintenance, traffic accidents, and natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions and tornadoes. Effective models must identify sequential patterns preceding an event and ideally classify occurrences early, before the complete signal emerges [25]. This challenge has given rise to the subfield of early time series classification, which focuses explicitly on balancing timely prediction with model accuracy.

Given the exceedingly rare and heterogeneous nature of tornado events, data curation and event labeling become central to model robustness and generalization. As noted by [1,29], proper handling of imbalanced datasets—including sampling techniques, cost-sensitive loss functions, and spatiotemporal alignment—is essential to avoid bias and underrepresentation of minority class dynamics. To address these challenges, our study adopts the benchmark TorNet dataset developed by MIT Lincoln Laboratory, which includes 3D volumetric radar sequences paired with frame-level tornado annotations.

2.3. Research Gap

Current tornado-prediction models exhibit high false-positive rates and insufficient true-negative recognition, which limits the reliability of their warning outputs. The TorNet benchmark was evaluated only with a Simple CNN, yielding an average AUC = 0.8815 over five-fold cross-validation [1], leaving open questions about stronger architectures and rare-event handling. We address this by (a) benchmarking CNN, VGG19, and Xception on TorNet and (b) testing each model with and without a KANs layer replacing conventional MLP blocks. We train with five optimizers and systematically compare performance to characterize rare-event detection trade-offs.

Our contributions in this study are threefold. Primarily, we provide a rigorous and reproducible performance benchmark for TorNet, systematically evaluating canonical deep learning architectures (CNN, VGG19, Xception, and their KAN-augmented variants) across five diverse optimizers. This baseline provides detailed performance metrics (F1, AUC-ROC, precision, recall, and accuracy) and analysis of training dynamics, establishing a transparent reference point for future research in radar-based tornado detection (an anonymized implementation of all models, training pipelines, and evaluation scripts used in this study is available at https://anonymous.4open.science/r/TorNet-DeepLearning-Models-702F/README.md (accessed on 3 March 2025)). Secondly, the empirical evidence on the systematic impact of KAN integration on tornado detection models, demonstrates a consistent uplift in validation AUC, enhanced rare-event sensitivity (recall), and improved training stability when embedded into established CNN architectures. This includes identifying specific conditions and architectural pairings where KAN layers most effectively improve performance for this challenging rare-event classification task. Finally, we provide here a practical and actionable methodological guidance for rare-event forecasting using weather radar data. This guidance is derived from extensive experimentation with radar-aware preprocessing, sophisticated data augmentation, and recall-sensitive training strategies (e.g., class weighting, sampling techniques, and Tversky loss). Here, we also provide empirically informed recommendations for optimal optimizer–architecture selections to effectively balance precision and recall in high-stakes meteorological scenarios.

3. Data and DL Models

To address the challenge of tornado prediction using radar images from the TorNet database, we implement a comparative analysis of six deep learning architectures: a vanilla Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), VGG19, Xception, and each model integration with KANs layer. This selection is motivated by three key considerations. First, the TorNet dataset comprises over 150 GB of radar reflectivity images, including confirmed tornado occurrences, tornado warnings, and severe storm events from 2013 to 2022. The large volume and spatiotemporal resolution of this dataset impose significant computational demands, which necessitate careful architectural choices. We downloaded the TorNet dataset [30] from the GitHub repository using the following URL “https://github.com/mit-ll/TorNet (accessed on 3 March 2025)”. Second, unlike conventional computer vision tasks where transfer learning from large-scale datasets such as ImageNet is feasible, radar-based tornado detection presents a domain-specific challenge with different data distributions, making pre-trained weights suboptimal. Third, many state-of-the-art CNN architectures rely on deep and computationally intensive layers, which may be impractical to train efficiently on a dataset of this size without access to high-performance computing infrastructure. Our model selection balances predictive power with computational efficiency, while also allowing for architectural innovation through the incorporation of interpretable kernel-based attention mechanisms via KANs layer.

In this section we will briefly discuss the dataset used in this study, the six deep learning models explored in this study and the performance measures and charts that will be used to compare the performance of the different models for tornado event prediction.

3.1. Dataset

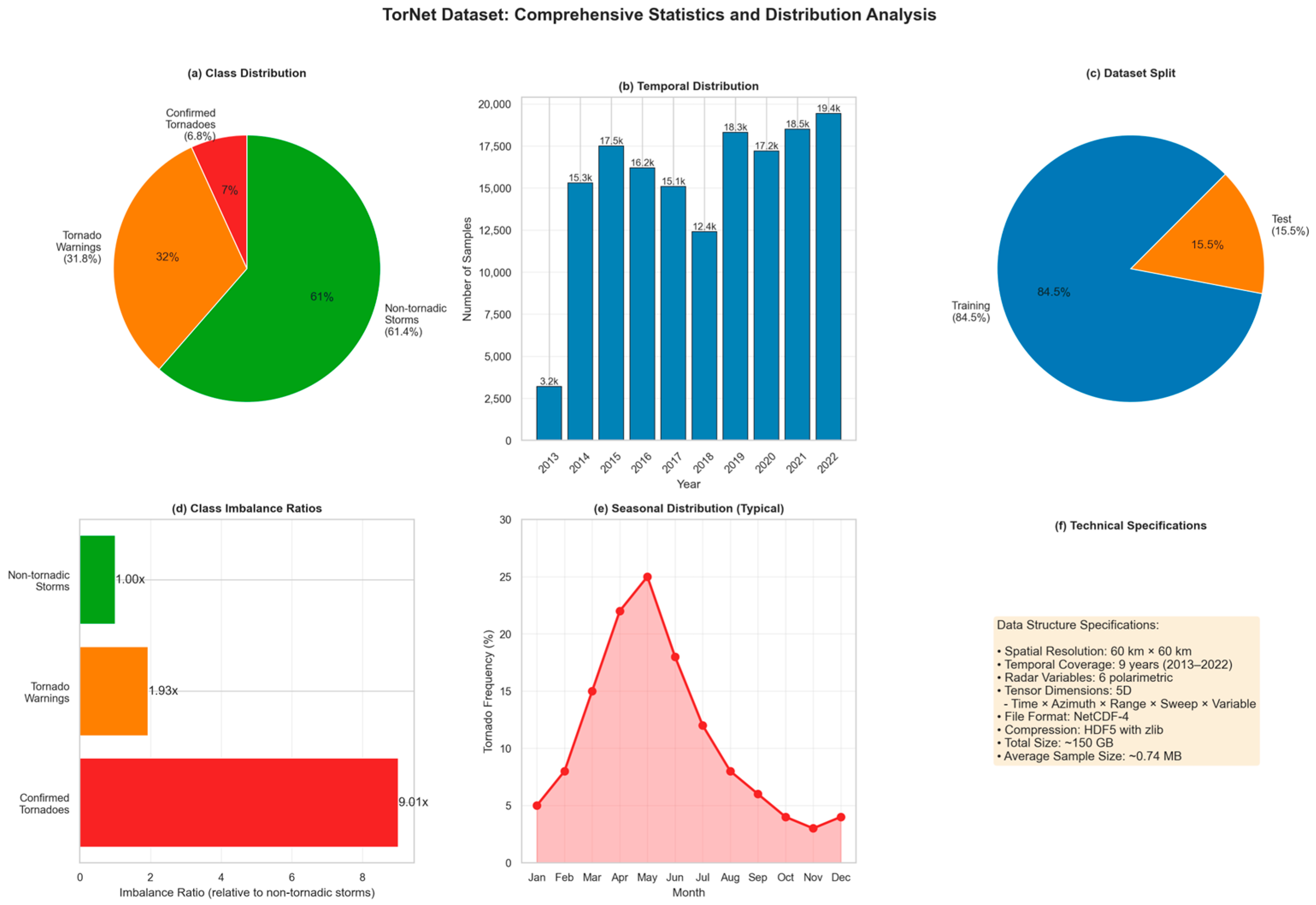

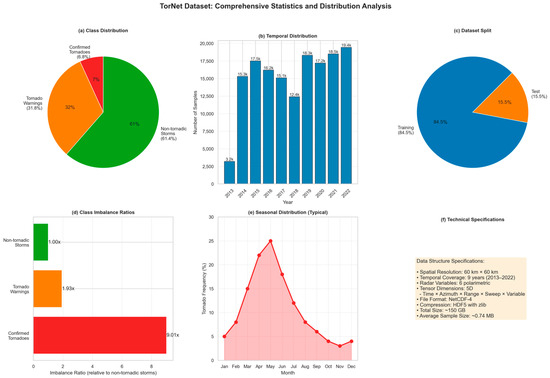

We utilize the benchmark tornado prediction dataset TorNet, compiled and released by MIT Lincoln Laboratory [1]. TorNet spans the period from August 2013 to August 2022 and contains 203,133 labeled radar samples drawn from full-resolution WSR-88D volumes: 13,857 confirmed tornadoes (6.8%), 64,510 tornado warnings without verification (31.8%), and 124,766 non-tornadic severe storms (61.4%). The dataset is partitioned using a strictly temporal split, with earlier years reserved for training and later years for testing, yielding 171,666 training samples (84.5%) and 31,467 test samples (15.5%). This configuration approximates an operational forecasting scenario in which models are trained on historical events and evaluated on genuinely unseen future periods.

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of TorNet, including total sample counts, temporal coverage, spatial resolution, and data volume. In addition to the three event categories, the table highlights several practical aspects for deep-learning research: each sample is a multi-channel radar tensor extracted over a 60 km × 60 km window, the data occupy roughly 150 GB on disk, and the underlying representation is five-dimensional (time × azimuth × range × sweep × variable), which has implications for both GPU memory footprint and batch design.

Table 1.

Comprehensive overview of the TorNet dataset including sample counts, temporal coverage, and technical specifications.

Because tornadoes are rare by construction, TorNet exhibits strong class imbalance (Table 2). Confirmed tornadoes account for only 6.8% of all samples and are outnumbered by non-tornadic storms by roughly 9:1, while unverified tornado warnings appear at an intermediate ratio of approximately 2:1 relative to non-tornadic cases. This imbalance structure mirrors real-world warning operations, where most radar volumes correspond to severe but non-tornadic storms.

Table 2.

Distribution of samples across event categories showing significant class imbalance typical of rare-event detection problems.

To provide a compact visual overview, Figure 1 plots several complementary statistics derived from TorNet. Figure 1a shows the three-way class distribution, reinforcing the dominance of non-tornadic storms and the rarity of verified tornadoes. Figure 1b reports annual sample counts from 2013 to 2022, illustrating that coverage is relatively uniform from 2014 onward, with 15,000–19,000 samples per year after the partial first year. Figure 1c depicts the temporal train–test split, with roughly 85% of samples used for training and 15% held out for evaluation. Figure 1d expresses the same information as class–imbalance ratios, taking non-tornadic storms as the reference class (1.00×) and showing that confirmed tornado cases are nearly an order of magnitude rarer (9.01×). Figure 1e summarizes the typical seasonal distribution of U.S. tornado occurrence, with activity peaking in April–June and sharply reduced frequencies in winter months, underscoring the strong intra-annual variability that models must contend with. Finally, Figure 1f consolidates the main technical specifications (spatial resolution, temporal coverage, number of polarimetric variables, tensor dimensionality, NetCDF-4/HDF5 storage, and average sample size), providing a reference for reproducibility and future benchmarking.

Figure 1.

Multi-panel summary of the TorNet benchmark.

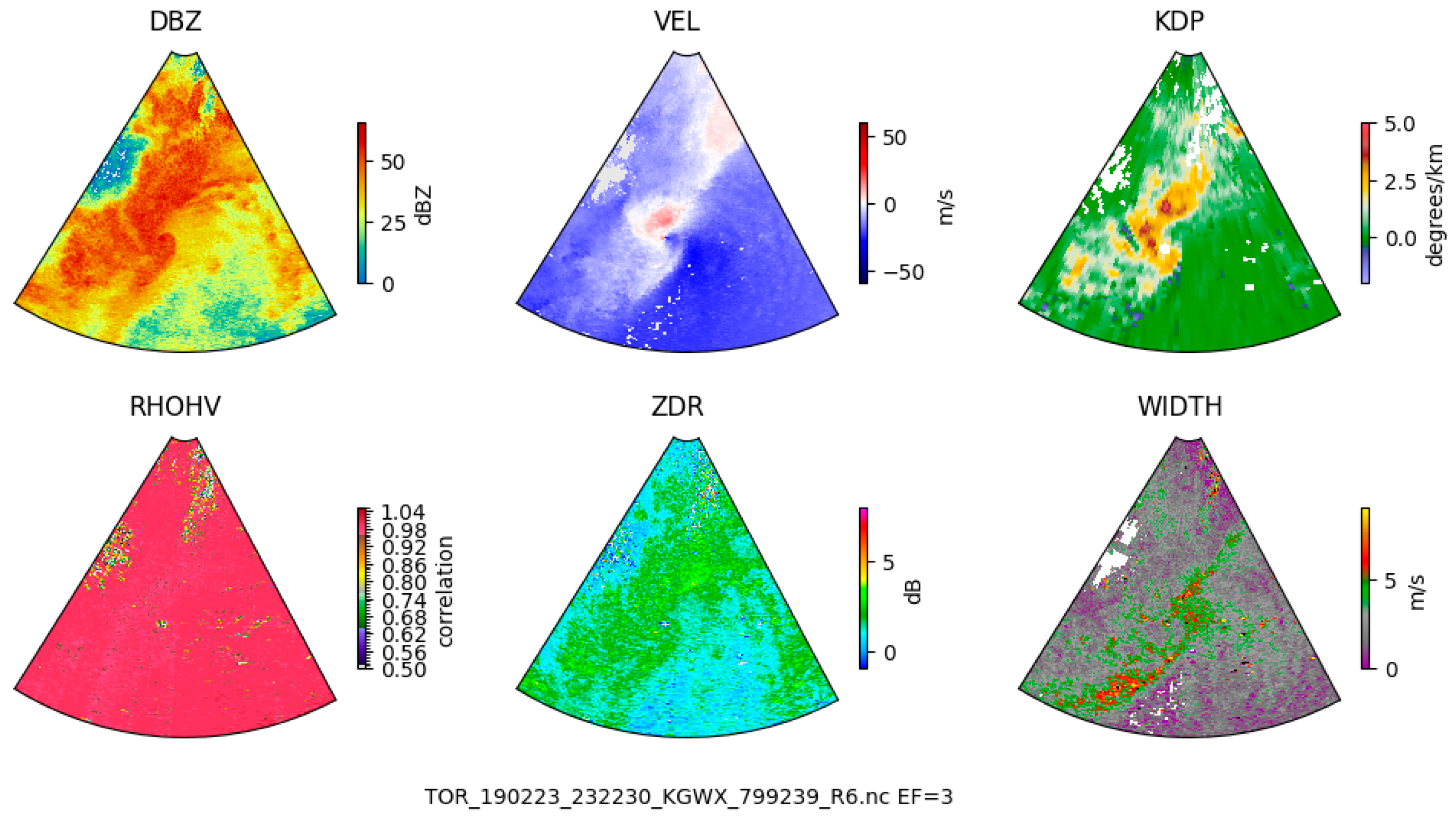

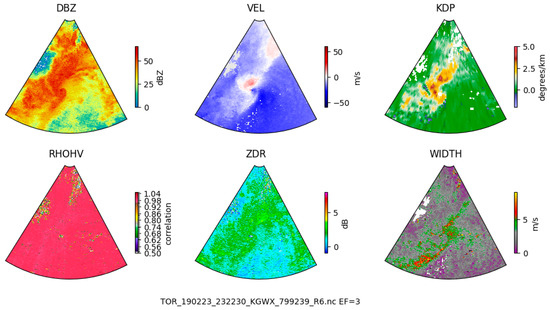

Each individual sample in this dataset represents a small spatiotemporal radar segment centered on a specific time ti and location (xi, yi). The radar inputs include six core WSR-88D radar variables, namely reflectivity (DBZ), radial velocity (VEL), specific differential phase (KDP), correlation coefficient (RHOHV), differential reflectivity (ZDR), and spectrum width (WIDTH). These variables were extracted from a 60° × 60 km spatial window, covering azimuthal and radial dimensions around the event center, and were structured as 5D tensors across time, azimuth, range, and radar sweep levels.

Table 3 summarizes the physical meaning, units, and typical range of each variable, together with the classical tornadic signatures they encode. For example, hook echoes and debris balls in DBZ, velocity couplets in VEL, low RHOHV and near-zero ZDR in debris, and enhanced spectrum width within the vortex. This joint representation allows DL models to exploit reflectivity structure and fine-scale polarimetric patterns that distinguish tornadic from non-tornadic convection.

Table 3.

Detailed specifications of the six polarimetric radar variables and their characteristic signatures in tornadic events.

Figure 2 illustrates an example radar frame for a confirmed EF3 tornado near KGWX radar site in Tennessee, recorded on 23 February 2019 (NOAA Storm Events Database event ID: 799239). This example highlights how the six radar channels reveal the structural and rotational features crucial for tornadic classification. By combining this high-resolution radar data with event-level NOAA metadata, including storm timing, EF rating, and geographic coordinates, we were able to analyze the spatial structure and severity of convective systems and refine data-driven tornado detection methods. The TorNet dataset’s integration of labeled radar observations with storm verification enables robust training and evaluation of ML models, particularly in the context of rare-event prediction.

Figure 2.

Retrieved from TorNet GitHub Repository [1].

3.2. DL Models

A total of six DL models were explored in this study. In this section, we will briefly discuss the architecture of each DL model and discuss how it was implemented in this study. Before discussing the DL models, we provide a brief introduction to the KAN layers, their features, and their potential advantages.

KANs represent a paradigm shift in neural network architecture by fundamentally reimagining the role of learnable parameters, moving them from the nodes—as seen in traditional MLPs—to the edges, where they are implemented as learnable univariate functions, often parameterized as splines [31]. This design is directly inspired by the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, which provides the theoretical foundation that any multivariate continuous function can be decomposed into a finite sum of continuous univariate functions [32]. In contrast, while MLPs are also universal approximators as proven by [33,34], they rely on fixed, typically nonlinear activation functions applied at neurons, with learning occurring only through adjustments of the weights connecting them. The architectural innovation of KANs grants them superior features, including vastly greater parameter efficiency, often achieving higher accuracy with hundreds of times fewer parameters than an MLP, and significantly enhanced interpretability, as the learned edge functions can be visualized and often reflect meaningful, smooth transformations indicative of underlying scientific laws [31]. Consequently, KANs are particularly adept at solving problems involving complex, high-dimensional function approximation where MLPs suffer from spectral bias or require massive, computationally expensive architectures. They show immense promise for applications in scientific machine learning, such as solving partial differential equations and discovering compact symbolic formulas from data, areas where the black-box nature and inefficiency of large MLPs present considerable limitations [31]. Thus, by leveraging a decades-old mathematical theorem [32], KANs offer a powerful alternative to the established MLP framework [33,34], trading potentially slower training times for groundbreaking gains in accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability.

In this study we have employed FastKAN, a lightweight variant of KAN. The KAN block used across all the hybrid models consists of Gaussian radial basis functions (RBFs) with 10 basis functions per input dimension, uniformly spaced on a grid ranging from –1 to +1. The kernel widths follow the standard FastKAN formulation, with spacing computed as (grid_max − grid_min)/num_grids. All spline-related linear layers employ L2 regularization (1 × 10−4). The hidden transformation is implemented as a three-layer MLP with dimensions 512, 256, and 128, respectively, each followed by dropout of 0.3. The base-update pathway is disabled, and the spline weights use the default initialization scale of 1.0. These settings were held constantly for all the classifiers including the CNN-KAN, VGG19-KAN and Xception-KAN models.

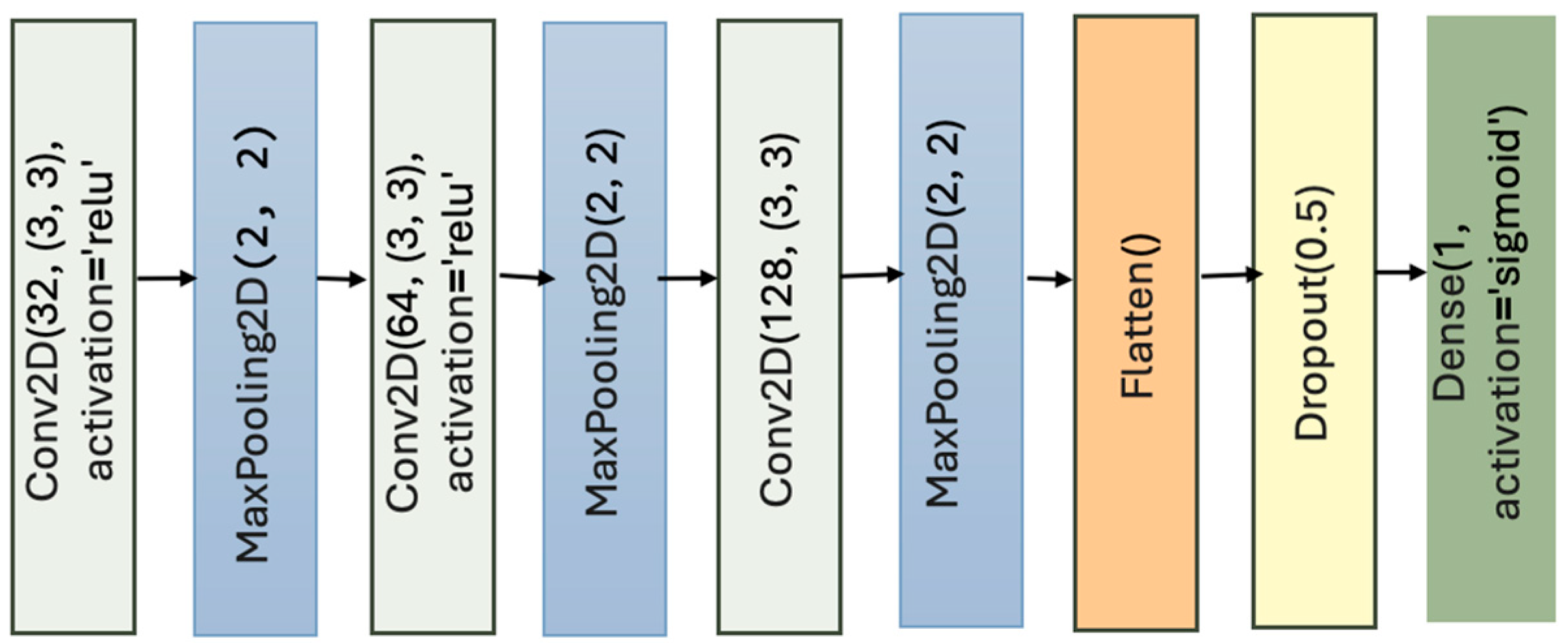

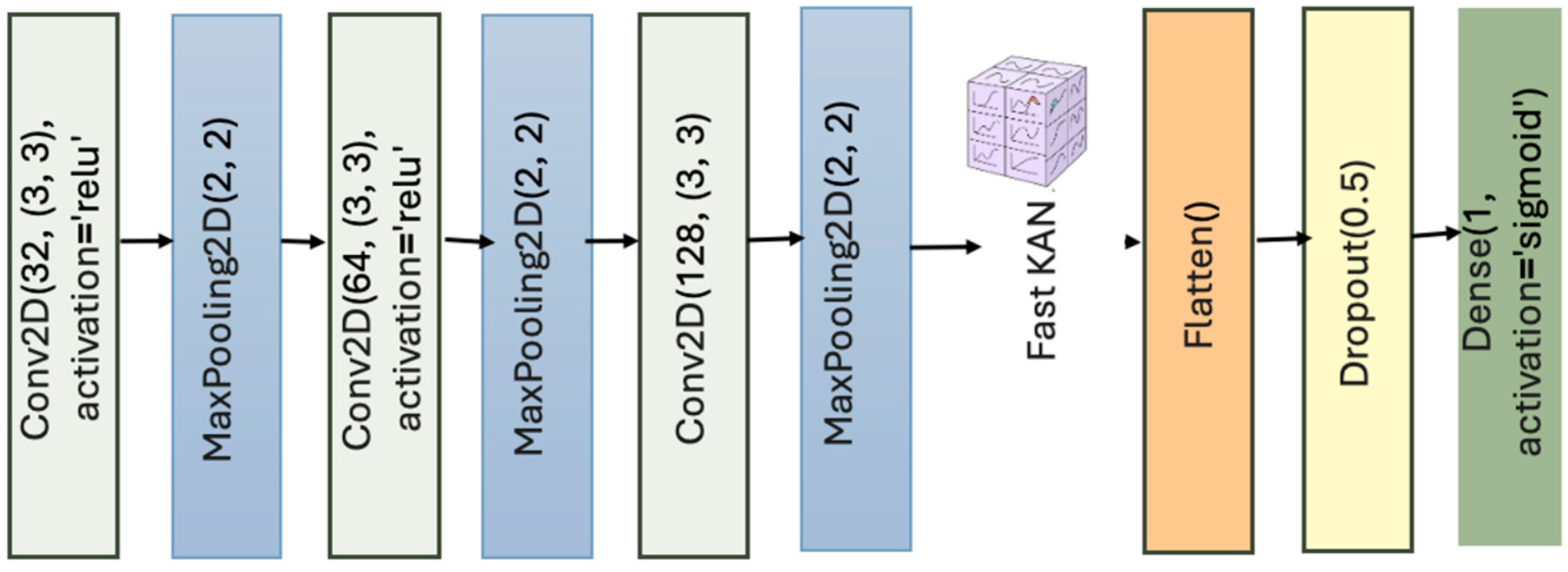

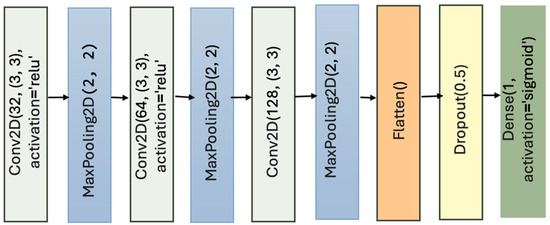

3.2.1. Vanilla CNN

Even though there are numerous variations in Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models, the overall structure follows a foundational architectural paradigm comprising an input layer, a sequence of convolutional and pooling layers, one or more fully connected (dense) layers, and an output layer for classification or regression. Each convolutional layer applies a set of learned filters to the input, extracting increasingly abstract spatial features, while pooling layers reduce dimensionality and promote translation invariance. The Vanilla CNN architecture eliminates the need for handcrafted feature engineering by automatically learning hierarchical feature representations directly from raw input data [35]. This model rose to prominence following the introduction of LeNet-5 by [36], which demonstrated the feasibility of using multilayer convolutional networks for digit recognition. Its core strength lies in their architectural simplicity, interpretability, and strong performance on relatively constrained visual tasks. Their use of local connectivity and weight sharing makes them significantly more parameter-efficient than fully connected networks for image data [37].

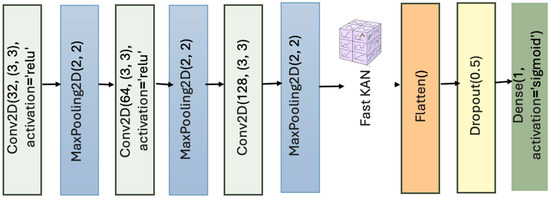

However, vanilla CNNs also exhibits several limitations that have motivated the development of deeper and more flexible models. First, the depth and structure of vanilla CNNs are often insufficient to model complex high-level abstractions required for fine-grained classification. As networks deepen, they are prone to vanishing gradients, which hampers effective learning and slows convergence [38]. Additionally, vanilla CNNs struggle with overfitting when trained on small datasets, due to their high capacity and lack of built-in regularization mechanisms. Moreover, vanilla CNNs lack mechanisms to capture global context, making them less suitable for tasks requiring holistic understanding, such as scene segmentation or long-range dependency modeling. Consequently, more advanced architectures—such as ResNet [38], Xception [39], and attention-based networks—have emerged to address these shortcomings while preserving the core insights of convolutional feature learning. The Vanilla CNN lacks the KAN layers (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Vanilla CNN lacking the KAN layers.

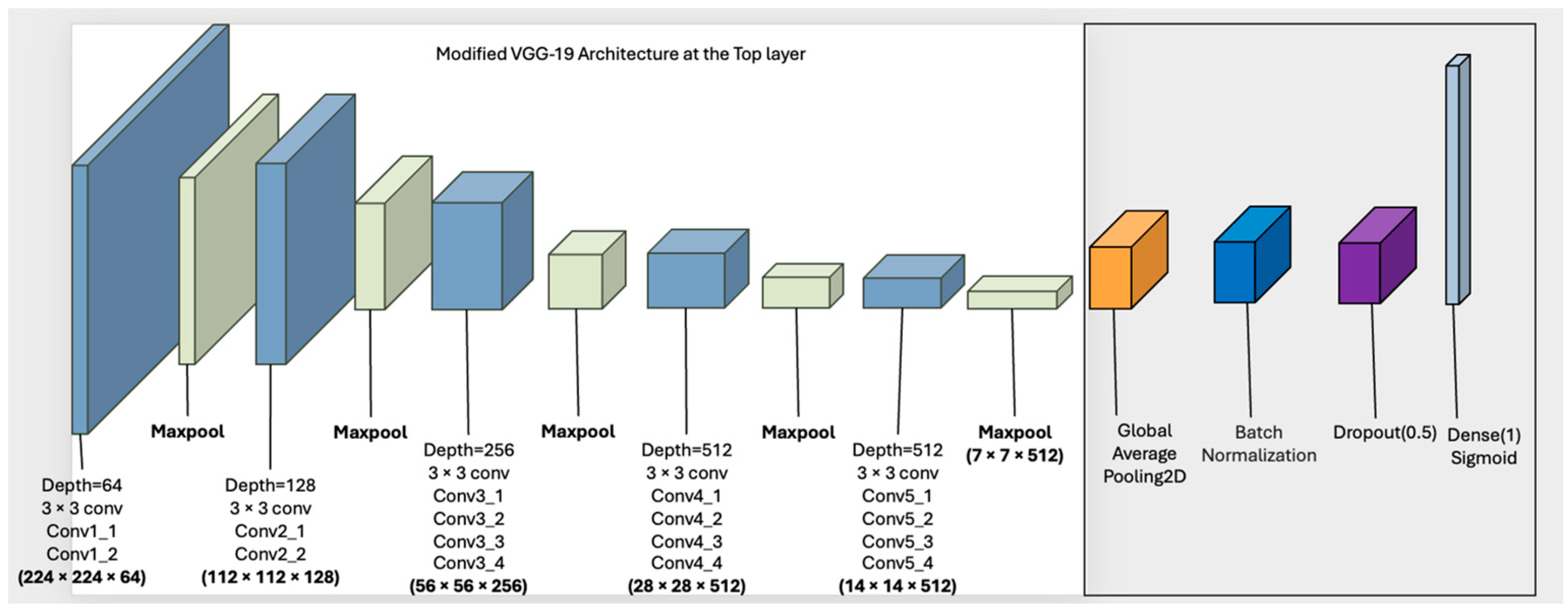

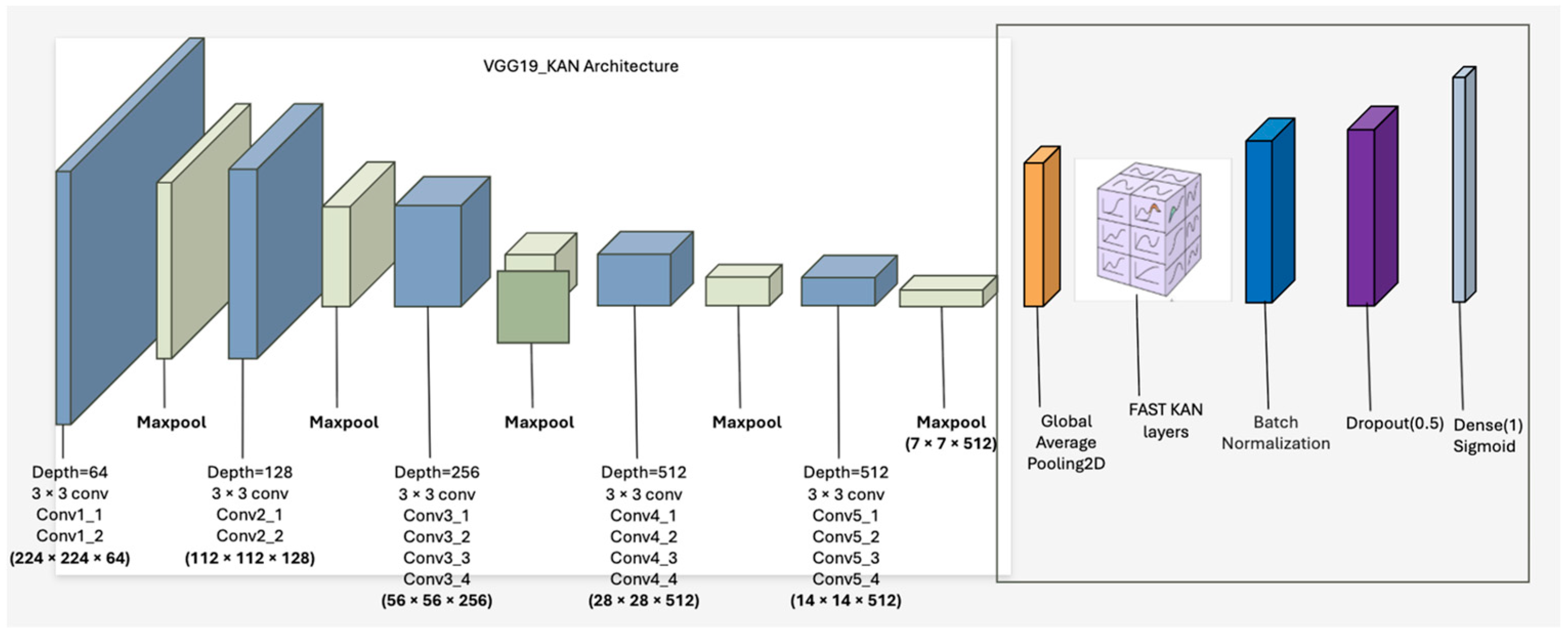

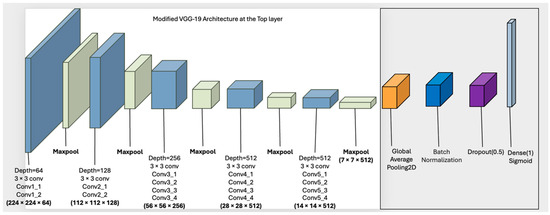

3.2.2. VGG19

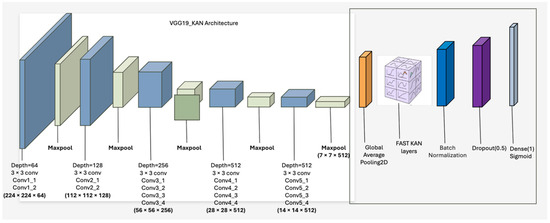

VGG19, introduced by [40] is a seminal deep convolutional neural network architecture that emphasizes simplicity and uniformity in design while achieving high performance on large-scale image recognition tasks. It is part of the Visual Geometry Group (VGG) family of models and is characterized by a deep architecture comprising 19 weight layers: sixteen convolutional layers and three fully connected layers, interleaved with max-pooling operations. All convolutional layers use small 3 × 3 filters with stride 1 and padding 1, allowing the model to capture fine-grained spatial hierarchies through successive depth without increasing the number of parameters disproportionately. In this study, we have updated the architecture of the VGG19 model by adding three additional components, namely the Global Average Pooling 2D, Batch Normalization, and the Dropout layer [41]. (See Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Modified VGG-19 architecture with additional output layers lacking the KAN layers, with new layers shown in orange, blue, and dark pink.

A key contribution of VGG19 lies in its demonstration that increasing depth—while maintaining a consistent kernel size—can lead to substantial improvements in classification accuracy, particularly when trained on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet. This “depth over width” philosophy marked a departure from earlier architectures like AlexNet, which used larger filters and fewer layers. The architectural regularity of VGG19 also makes it highly modular and interpretable, facilitating transfer learning and feature reuse in diverse domains, including remote sensing, medical diagnostics, and weather radar analysis.

Despite its strengths, VGG19 also presents several limitations, particularly in the context of domain-specific applications such as radar-based tornado prediction. First, its depth and fully connected layers make it computationally expensive, both in terms of memory usage and inference time. This becomes a significant drawback when working with large datasets like TorNet, which contains high-resolution spatiotemporal data. Second, VGG19 lacks residual connections, making it more prone to vanishing gradients during training as depth increases. Third, while the model is effective at hierarchical feature extraction, it lacks inductive biases for long-range dependencies or attention mechanisms, which are increasingly recognized as important for capturing global patterns, especially in structured domains like meteorological imaging.

In our study, VGG19 serves as a benchmark for evaluating the performance and scalability of conventional deep convolutional architectures. When combined with KANs, we aim to assess whether the addition of interpretable and nonlinear kernel-based functional expansions can overcome some of VGG19’s rigidity and enhance its performance on complex, high-dimensional spatiotemporal data such as radar-based tornado detection.

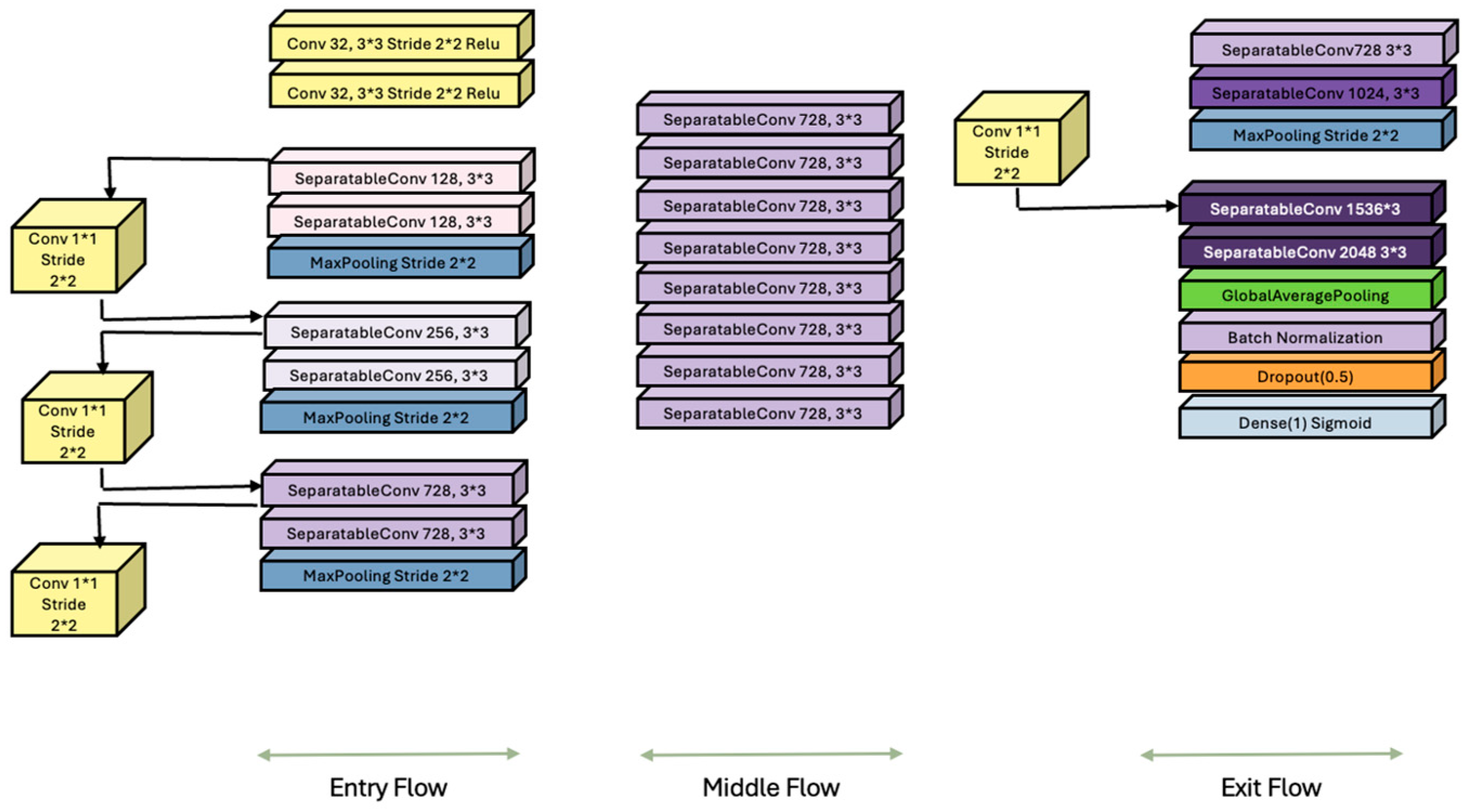

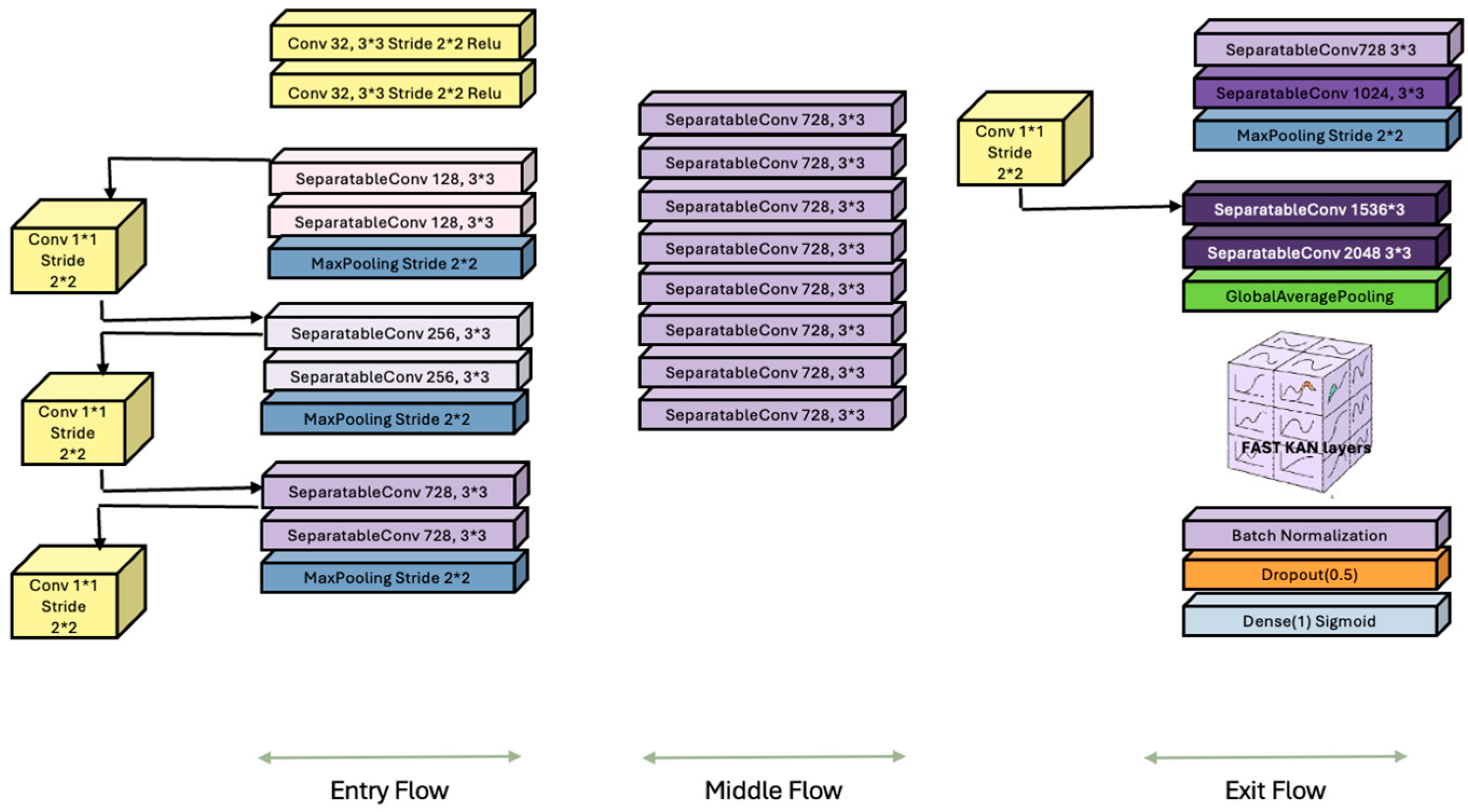

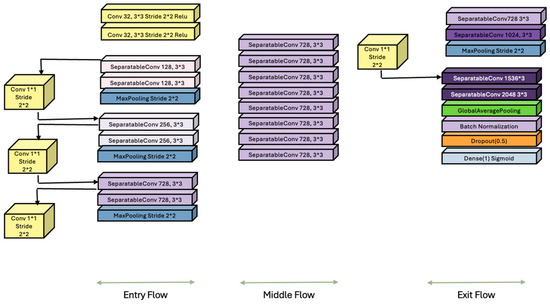

3.2.3. Xception

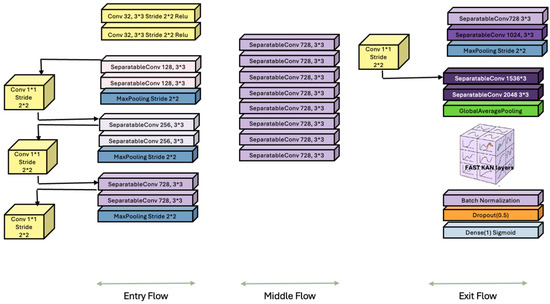

The Xception architecture (Extreme Inception), introduced by [39], represents a pivotal evolution in CNN design by rethinking the structure of Inception modules through the lens of depthwise separable convolutions. Built on the hypothesis that spatial and cross-channel correlations can be decoupled entirely, Xception replaces the standard convolutional layers with a two-step operation: depthwise convolution, which applies a single filter per input channel, followed by pointwise convolution, a 1 × 1 convolution that projects the outputs into a new feature space (See Figure 5). This reconfiguration significantly reduces the number of parameters and computational cost while preserving or enhancing the representational power.

Figure 5.

Modified Xception architecture with additional output layers, lacking the KAN layers. The newly added layers appear in green, purple, orange, and blue near the lower-right portion of the figure.

Xception can be viewed as an “extreme” version of the Inception architecture [42], which utilizes multiple parallel convolutional filters of varying sizes to extract multi-scale features. By contrast, Xception simplifies the architecture by applying only depth wise separable convolutions uniformly throughout the network, while incorporating residual connections inspired by ResNet [38] to improve gradient flow and enable deeper networks. This design choice makes Xception not only more elegant but also more modular and scalable, allowing it to achieve state-of-the-art performance on large-scale image classification benchmarks such as ImageNet with fewer parameters than comparable models.

One of the key advantages of Xception lies in its computational efficiency and architectural generality. Depthwise separable convolutions drastically reduce the number of multiplications required during inference, making Xception highly suitable for applications with resource constraints, such as mobile or embedded vision systems. Additionally, the modularity of the architecture facilitates transfer learning, and pre-trained Xception models have demonstrated strong performance across a wide range of downstream tasks including medical imaging [43], scene understanding, and object detection. Unlike earlier architectures that mix convolutional filter sizes and topologies, Xception’s consistent structural paradigm is easier to implement and tune.

However, despite its strengths, Xception has limitations. The separation of spatial and channel-wise operations, while efficient, can result in the loss of critical interactions between channels in early layers, particularly when feature maps are shallow or sparsely activated. Moreover, the architecture is inherently feedforward and lacks mechanisms for dynamic attention or global context modeling, which newer architectures such as transformers or attention-augmented CNNs explicitly address [44]. Additionally, although residual connections aid in convergence, Xception still relies heavily on large datasets to realize its full potential, which can be a bottleneck in low-resource or domain-specific scenarios. Note that in the Exit flow section we have enhanced the Xception architecture to include four additional components namely the Global Average Pooling 2D, Batch Normalization, Dropout layer, and the Dense Sigmoid layer represented using the green, pink, orange and light blue color (See Figure 5).

In addition to making the simple modifications in the above-mentioned architectures, we also integrated KANs layers across Vanilla CNN, VGG19 and Xception. Recent advancements in neural network design have increasingly focused on integrating interpretable and adaptive modules into traditional DL architectures. One such innovation is the KAN introduced by [31], which replaces conventional fully connected (MLP) layers with kernel-based functional expansions. KANs are inspired by the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem, which posits that any multivariate continuous function can be expressed as a finite composition of univariate functions and addition. In KANs, each neuron learns a mapping via a sum of learned basis functions applied to inputs rather than relying on the fixed inner-product-based activations. This architecture enables the network to capture complex nonlinear dependencies while enhancing mathematical interpretability and extrapolation capabilities.

In this section, we will discuss and highlight the integration of KAN layers into the three CNN-based architectures. Here, we will highlight the architectural roles, benefits, and trade-offs in enhancing expressivity, generalization, and transparency because of the KAN layer integrations into these architectures.

3.2.4. KANs in Vanilla CNNs

Classic CNNs rely on fully connected output layers, which often lack the flexibility to capture complex nonlinear patterns, especially in small or noisy datasets. By replacing these with KAN layers, CNNs can represent more intricate decision boundaries through a learned combination of interpretable kernel basis functions [31]. This is particularly useful in scientific and safety-critical applications where understanding model behavior is essential [45,46]. The resulting Vanilla CNN architecture with fast KAN layers is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Vanilla CNN with fast KANs layers.

3.2.5. KANs in VGG19

VGG19 [40] is a widely used CNN known for its deep stack of uniform 3 × 3 convolutional layers. However, its final dense layers are limited in capturing nonlinear mappings without significantly increasing depth. Replacing these layers with KAN modules (highlighted using a rectangular box in Figure 7 allows the model to approximate complex functions more efficiently, aligning with the theoretical structure of the Kolmogorov–Arnold theorem and improving interpretability at the output stage [31].

Figure 7.

Modified VGG-19 architecture with additional output layers with fast KANs layers, with new layers shown in orange, blue, and dark pink.

3.2.6. KANs in Xception

Xception [39] employs depth-wise separable convolutions for efficient feature extraction. While computationally efficient, its dense output layers may underfit tasks that require nuanced, nonlinear decision boundaries. Integrating KANs into the Xception output stage (indicated using rectangular region in Figure 8) introduces an interpretable kernel-based layer without compromising the model’s efficient convolutional backbone. This hybrid architecture is well-suited for applications in geospatial forecasting, biomedical diagnostics, and remote sensing, where both performance and transparency are crucial [47].

Figure 8.

Xception with fast KANs layers. The newly added layers appear in green, pink, purple, orange, and blue near the lower-right portion of the figure.

The integration of KANs into CNN-based models introduces a powerful balance between functional expressiveness and model interpretability. By replacing traditional MLP output layers with kernel-based expansions, KANs enable neurons to learn adaptive, nonlinear functions using interpretable basis functions [31]. This enhancement allows models to better capture complex decision boundaries, particularly in data-scarce or high-variability environments, while offering transparency often absent in standard deep learning models [45,48]. KANs are especially well-suited for applications in scientific and safety-critical domains, where both predictive performance and explainability are required [45,48]. However, this architectural advancement comes with trade-offs. KANs introduce increased computational overhead and require careful hyperparameter tuning, such as kernel type, spacing, and regularization strength, to ensure stable training and convergence [31]. Their training dynamics are more sensitive than conventional MLPs, and implementation is further complicated by the lack of standardized support in mainstream frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow. These limitations may pose barriers to deployment and scalability unless accompanied by further optimization and toolchain development [49,50]. Despite these challenges, KANs offer a compelling pathway toward interpretable, generalizable, and functionally rich neural networks.

In sum, incorporating KANs into CNN-based architectures such as CNNs, VGG19, and Xception represents a promising step toward interpretable and generalizable DL. KANs extend the model’s expressiveness without dramatically increasing complexity and introduce valuable transparency via their kernel-based formulation. While current implementation and tuning challenges remain, the growing emphasis on explainability and robustness suggests that KAN-augmented models will play an increasingly important role in domains requiring high performance, interpretability, and reliability.

4. Methodology

In this study, we have compared the performance of the different KANs layers integrated CNN architectures using standard classification metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC), F score, and loss. Let TP, FP, TN, and FN denote the counts of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, respectively. Recall (also called the true-positive rate or sensitivity) quantifies the proportion of actual positives correctly identified, Recall = . Precision (positive predictive value) measures the proportion of predicted positives that are correct, Precision = . Because tornado detection is a rare-event setting, we report the F1-score family, which captures the precision–recall trade-off at a chosen threshold. The F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) is . Overall accuracy is Accuracy = .

To calculate AUC, we also compute the false-positive rate (FPR), FPR = , to complete the ROC analysis. To construct the ROC curve, we vary the decision threshold T Î [0,1] applied to the model’s predicted probabilities and plot recall (TPR) against FPR at each T. The AUC-ROC summarizes this trade-off across all thresholds as the integral under the ROC curve (estimated via the trapezoidal rule). Higher AUC values indicate better ranking performance independent of any single threshold. Loss is reported as the optimization objective used during training (e.g., cross-entropy), providing a complementary view of fit that is sensitive to the full predictive distribution rather than discrete class decisions.

In the next section, we detail the research methodology.

4.1. Training Strategies and Hyperparameter Optimization

To compare the performance of the six different models, we employed two different training pipelines. All the models were trained separately using two types of datasets, namely the original dataset (V1) and the improved and augmented dataset (V2). The V1 dataset is raw data without any extra filtering or augmentation. Across the training pipelines we employed the following hyperparameter optimization (random search) strategy. Each model was trained with a batch size of 32 and using the Binary Cross entropy loss function. A different set of optimizers, including the SGD, Adam, RMSprop, Adagrad and Lion were employed across the different models. We used early stopping with a patience of 6 and saved the best model weights to avoid overfitting. Models using the V1 dataset were trained for up to 40 epochs.

In the V2 dataset, we added radar-specific data augmentations like flipping, brightness and contrast changes, zoom, and small shifts to make the models more robust to real-world variability. We also applied class weighting to give more importance to the rare tornado class (class_weight = {0:1., 1:7.}) thus helping the models to better detect rare events. Models that were trained using the V2 dataset were trained for up to 60 epochs. The other hyperparameters were kept similar to the training setup as discussed earlier (models trained with V1 dataset).

Across both pipelines, we used six different models that included the Vanilla CNN, VGG19, and Xception, both with and without KAN layers. It is also important to note that the same optimizers were used across both the training pipelines. This setup helped us clearly understand how the choices of preprocessing and architecture affect model performance, i.e., the learning, accuracy, and rare tornado event detection.

4.2. Data Augmentation for Radar Semantics

To enhance the generalization and robustness of the model in the presence of noisy and heterogeneous atmospheric signals, we implemented a suite of domain-aware data augmentation techniques specifically tailored for volumetric radar data that is used in tornado detection. In the standard image datasets including the radar reflectivity (DBZ), radial velocity (VEL), and differential phase (KDP) channels that uses the conventional image augmentation methods, such as arbitrary rotation or perspective warping suffers from distorted spatial-temporal coherence and introduces physically implausible structures. Therefore, we designed augmentations that preserve the intrinsic meteorological semantics while introducing variability aligned with radar physics.

For our radar-aware augmentation pipeline we included the following transformations: (1) azimuthal flipping, which mirrors the azimuth dimension to simulate directional symmetry, preserving mesoscale patterns such as hook echoes; (2) channel-wise intensity scaling, which applies minor multiplicative perturbations to each channel, simulating sensor calibration noise or rainfall rate bias; (3) additive Gaussian noise, mimicking electronic radar noise while maintaining signal structure; (4) sparse spatial dropout, which randomly zeroes out localized patches to emulate partial returns or transient beam obstruction; and (5) channel-specific noise injection, encouraging the model to learn more robust cross-channel correlations. Finally, all augmented values were clipped within a normalized physical range of [−10,10] to retain numerical stability and physical realism.

These augmentations were applied stochastically during the training process, ensuring that each training epoch presents the model with a slightly altered yet physically consistent representation of the same storm event. We believe that this strategy acts as a strong regularization technique, thus mitigating overfitting and enabling the model to better generalize towards unseen radar volumes under diverse atmospheric and sensor conditions. These data augmentation strategies are also critical for high-stakes tasks such as early tornado detection.

4.3. Radar-Variable Filtering and Preprocessing

In addition to data augmentation, we also implemented a radar-variable-specific filtering pipeline to reduce noise and enhance the meteorological signal fidelity prior to training. Radar volumes often contain small-scale artifacts and noise that can obscure critical features such as tornadic rotation or echo structures. Rather than applying generic image denoising, we adopted a lightweight, physically informed filtering strategy tailored to the behavior of each radar variable.

For Doppler velocity (VEL), we applied a 3 × 3 median filter to eliminate isolated spikes while preserving the shear couplets indicative of rotation. Reflectivity (DBZ) and differential reflectivity (ZDR) fields were smoothed using a Gaussian filter (σ = 1.0), with DBZ receiving adaptive range-dependent smoothing to account for beam broadening at greater distances. Specific differential phase (KDP) underwent minimal Gaussian smoothing to maintain microphysical detail. Other fields, including correlation coefficient (RHOHV) and spectrum width (WIDTH), were left unfiltered due to their inherent stability or sensitivity to small-scale structures.

Filtering was also applied channel-wise after radar volumes were extracted from the net CDF format. All filtered variables were subsequently normalized using pre-defined scaling constants and clipped to the range [−10, 10] to ensure physical plausibility and numerical stability during the training process. To provide additional spatial and physical context, we appended two auxiliary channels: (1) a binary range-folded mask identifying regions with Doppler velocity ambiguity, and (2) an inverse range map encoding normalized distance from the radar source. These inputs helped the model in compensating for variable resolution and data quality across the radar scan domain.

The proposed preprocessing framework significantly enhanced the quality and consistency of input data, improving model convergence, and increasing the sensitivity to meteorologically relevant structures in noisy volumetric radar observations.

4.4. Optimizer Selection

At the core of DL architecture lies a hierarchy of interconnected nodes organized into layers, collectively forming a neural network capable of modeling complex nonlinear relationships. As input data passes through several layers of neural networks, the network iteratively refines internal representations to improve predictive accuracy. A crucial component in this process is the choice of optimization algorithms, which is responsible for the fine-tuning between layers, specifically the weights and biases, based on the computed gradients. In this study, we have systematically evaluated several widely used optimization algorithms [51]—including Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), RMSProp, Adam, Adagrad, and Lion—to assess their effectiveness in minimizing training loss and accelerating convergence in DL models trained on the TorNet database. This dataset presents significant challenges due to its noisy, imbalanced, and spatiotemporally complex nature, reflecting the real-world difficulty of tornado detection.

SGD is a foundational optimization algorithm, particularly essential for the large-scale and complex problems prevalent in deep learning, primarily due to its efficiency and robustness in navigating intricate loss landscapes [37]. A key task-specific rationale for SGD is its superior computational efficiency, which arises from estimating gradients using small mini-batches instead of the entire dataset. This approach drastically reduces the computational cost per iteration, making the training of models on vast amounts of data feasible [52]. The inherent noise introduced by mini-batch gradient estimation is also beneficial; it allows the optimization process to escape shallow local minima in non-convex loss functions, often leading to improved generalization [53]. Additionally, SGD’s online learning capability provides a significant advantage for dynamic applications by enabling continuous model updates as new data streams in. The overall effectiveness of SGD is, however, highly contingent on the meticulous tuning of its various hyperparameters, a process predominantly guided by empirical evidence and specific task requirements. The learning rate, arguably the most critical parameter, directly controls the magnitude of parameter updates. Optimal performance often necessitates dynamic learning rate schedules, such as decay strategies, warm-up periods, or cyclical learning rates, which demonstrably accelerate training and refine convergence [54]. Batch size is another pivotal hyperparameter, influencing both the stability of gradient estimates and the model’s generalization ability; small batches often introduce valuable regularization, while larger batches offer computational parallelism [37]. Integrating momentum into SGD is a common practice, as it helps to accelerate convergence in the relevant direction and effectively dampens oscillations across the loss landscape. Finally, weight decay, functioning as a form of L2 regularization, is frequently incorporated within the optimization routine to prevent overfitting by penalizing excessively large model weights, thus requiring careful calibration alongside other parameters to achieve optimal overall model performance.

SGD, known for its simplicity and theoretical robustness [55], uses a fixed learning rate and updates the gradients uniformly. Although it tends to converge slowly and may get stuck in sharp or saddle points, it remains a strong baseline due to its stability and generalization properties—particularly valuable in noisy prediction settings such as radar-based tornado detection.

RMSProp, introduced by [56], builds upon SGD by adapting learning rates using a moving average of squared gradients. It is especially effective for non-stationary objectives and time-dependent data.

Reference [57] combines the strengths of RMSProp and momentum by computing adaptive learning rates for each parameter using both first and second moments of the gradients. Similarly to other adaptive methods, it may converge to sharp minima and sometimes struggle with generalization [58].

Reference [57] also uses adaptive learning rates based on the accumulated squared gradients. While it is advantageous for sparse feature spaces, its monotonically decreasing learning rate often causes training to stall prematurely, limiting its effectiveness on long training sequences such as those common in spatiotemporal radar analysis.

Lion, a recent optimizer proposed by [59], leverages normalized update directions with a simple momentum-like scheme, offering lower memory usage and faster convergence.

5. Results

The objectives of this study are twofold. First, the prediction of tornado occurrence constitutes a classical rare event detection challenge in a temporally bound context. A defining characteristic of rare event classification within a supervised learning framework is the temporal structure of the input data. Specifically, each instance is a time series, where the goal is to distinguish between rare events (e.g., tornadic activity) and non-events based on previously observed temporal patterns [60]. This setting is referred to as supervised time-series classification [28]. Given the urgency inherent to tornado prediction, we further adopt the framework of early time-series classification [25], where the goal is to make accurate predictions of event onset as early as possible—ideally before the complete time sequence has been observed. This framing is particularly appropriate for real-time systems operating under severe time constraints and with significant consequences for misclassification.

Second, beyond the detection task, our system is designed to support real-time generation of high-quality disaster response reports and tornado alerts. This involves the retrieval and summarization of relevant emergency protocols and local resource availability using language generation models. To address both the objectives, we outline detailed training and testing strategies, including temporal validation splits and fine-tuning methods, and specify evaluation metrics tailored to the requirements of high-recall detection and context-aware generation.

5.1. Baseline Model Results

We evaluate six deep-learning architectures, each trained under five optimization algorithms, on the TorNet benchmark. Performance varies substantially by optimizer–architecture pairing (Table 1). The best F1 is achieved by CNN + Adam (F1 = 0.375; Accuracy = 0.907, Precision = 0.327, Recall = 0.441, AUC = 0.839). The next best are VGG19-KAN + Adam (F1 = 0.366; Accuracy = 0.856, Precision = 0.254, Recall; = 0.655, AUC = 0.840) and VGG19-KAN + RMSprop (F1 = 0.349; Accuracy = 0.944, Precision = 0.663, Recall = 0.237, AUC = 0.865, the highest AUC in the table). These three results illustrate the central trade-off in the baseline setting: some models attain high recall (e.g., VGG19-KAN + Adam, CNN-KAN + Adam with Recall ≈ 0.66) at the expense of precision, whereas others achieve very high precision (e.g., VGG19-KAN + RMSprop, Precision = 0.663) but lower recall, yielding similar F1 outcomes. KAN augmentation generally raises AUC and recall within the backbone. For example, Xception-KAN + Lion reaches Recall = 0.768 (F1 = 0.289; AUC = 0.849), while CNN-KAN + Adam attains Recall = 0.661 (F1 = 0.301; AUC = 0.818), both markedly higher recall than many non-KAN counterparts. However, KAN gains are not uniform; performance depends on the optimizer and threshold, and some non-KAN baselines (e.g., CNN + Adam) remain competitive on F1.

It is notable that several configurations achieve accuracies near 0.94 while exhibiting near-zero precision and recall (e.g., some VGG19 baselines), a classic pitfall in rare-event detection when the classifier effectively predicts only the negative class (non-tornadic storms). Because confirmed tornadoes comprise just 6.8% of the sample, a model can post high accuracy by favoring the majority class. This underscores why F1, recall, PR-AUC, and AUC-ROC are more diagnostic of operational utility than accuracy in rare-event detection.

To mitigate class imbalance, we implemented several recall-sensitive strategies during the final model development in addition to image filtering and augmentation: (1) Tomek-links under-sampling to remove ambiguous negative examples and clarify decision boundaries; (2) oversampling of tornado cases (positive class) to increase minority class exposure during training; (3) dynamic class weighting, to adjust the loss contribution based on inverse class frequency; and (4) the use of a Tversky loss function that jointly penalizes false positives and false negatives to enhance robustness under imbalance. Collectively, these intervention strategies improved the model’s sensitivity to rare events detection while maintaining competitive overall performance, making it a strong baseline for further experimentation with deeper or hybrid architectures.

5.2. Final Results After Filtering and Augmentation

To improve rare-event detection under operational constraints, we applied a radar-aware augmentation and domain-specific filtering pipeline (Dataset V2) as noted above. We then re-trained 30 models spanning three backbones (CNN, VGG19, Xception), each with and without KAN layers, under five optimizers (SGD, Adam, RMSProp, Adagrad, Lion). The augmented/filtered data substantially improved robustness and generalization across architectures. This systematic evaluation allowed us to examine the convergence dynamics, classification effectiveness, and rare-event sensitivity under controlled but realistic data conditions. The V2 regimen consistently tightened optimizer spread, accelerated recall convergence, and lifted the discrimination ceiling, with the largest gains observed in KAN-augmented variants.

The best overall F1 score was obtained by CNN + Adam (F1 = 0.332; Accuracy = 0.921; Precision = 0.358; Recall = 0.309; ROC-AUC = 0.774). The strongest thresholded balance of precision and recall was achieved by VGG19-KAN + RMSProp (F1 = 0.320; Accuracy = 0.946; Precision = 0.791; Recall = 0.201; ROC-AUC = 0.875), indicating robust event capture at controlled false-alarm rates. Some high-accuracy configurations (≈ 0.94) show near-zero precision and recall, effectively predicting only the majority (non-tornado) class. Conversely, some low-accuracy runs (≈0.06) report recall near 1.0 but precision near 0.06, behaving like always-positive classifiers.

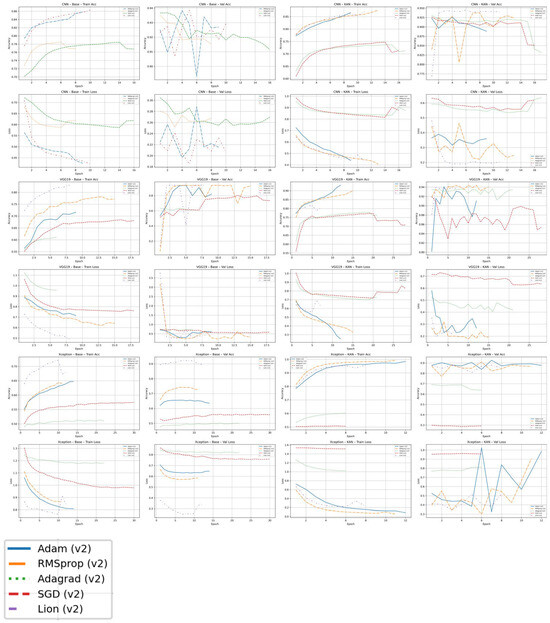

5.3. KAN-Integration

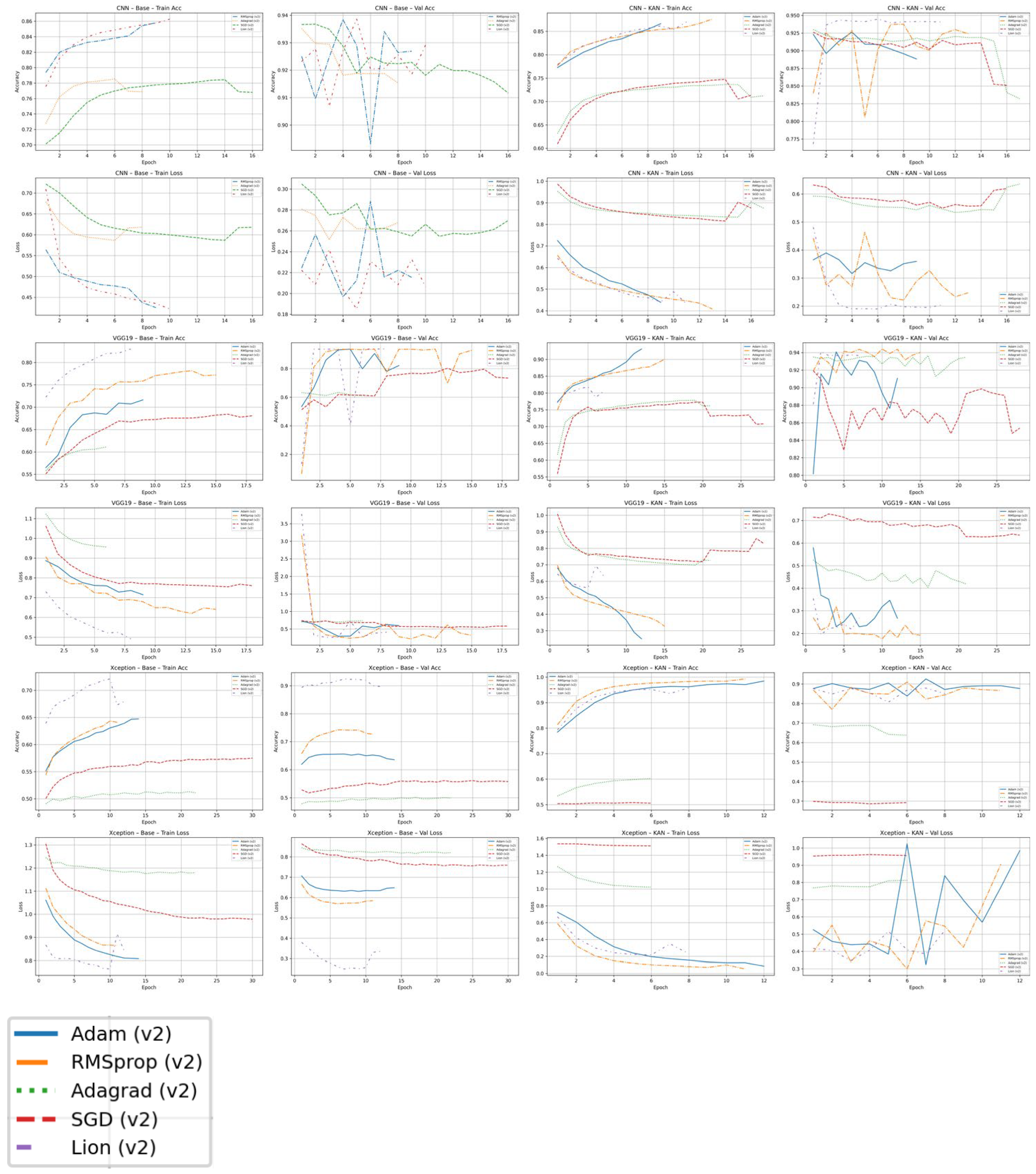

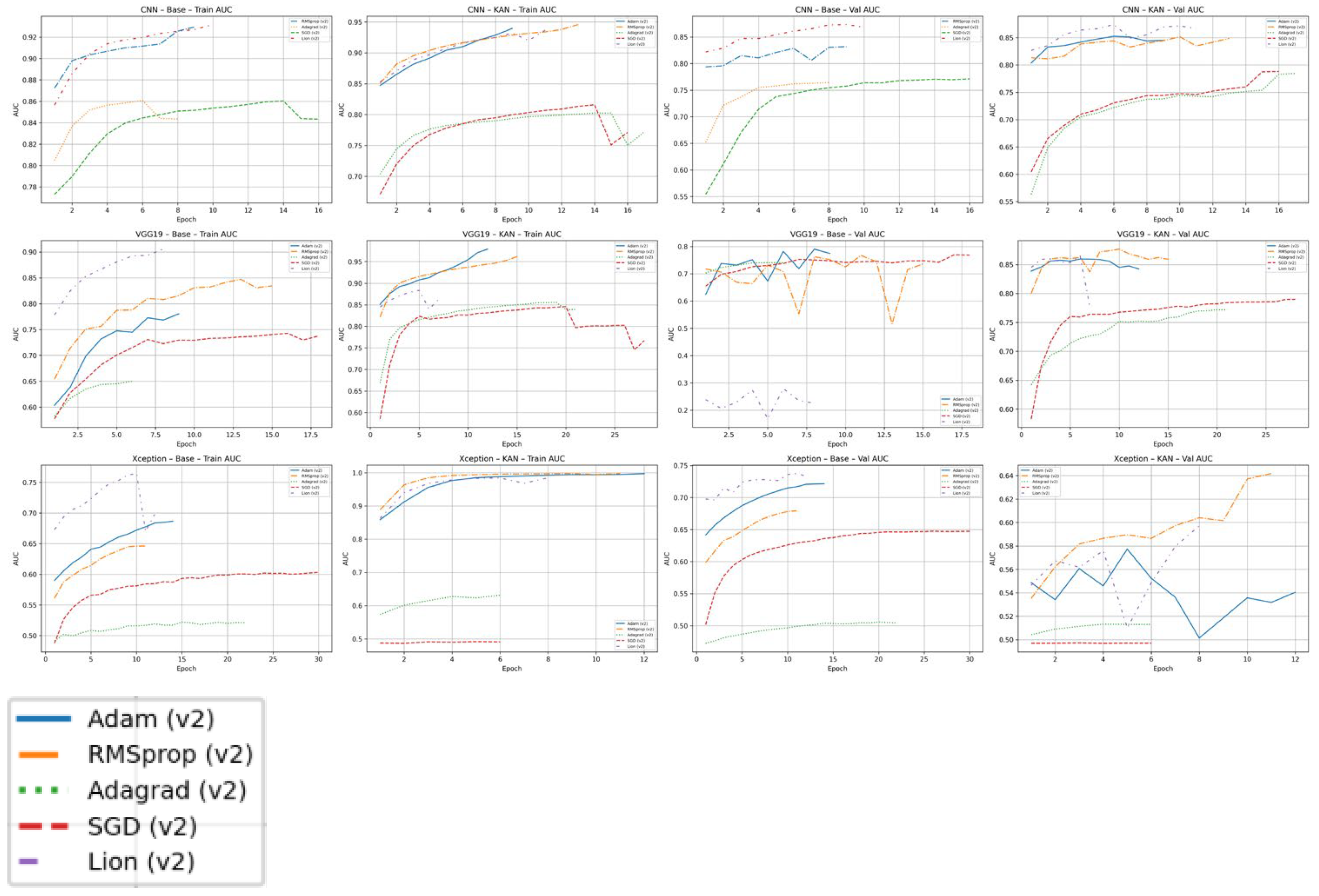

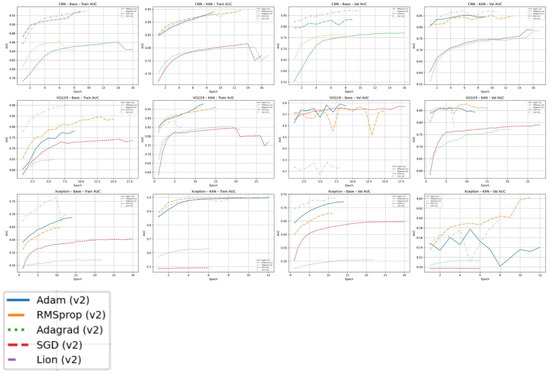

KAN augmentation provides a systematic uplift in both model discrimination and training stability. Within each backbone (e.g., CNN, VGG19, and Xception) the KAN-enabled variants achieve consistently higher validation of AUC than their plain counterparts and show smoother, more monotonic learning curves. This effect is visible in the epoch-by-epoch plots shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10: KAN models converge more steadily, with reduced oscillation in validation accuracy, recall, and loss, while non-KAN baselines exhibit wider swings and more optimizer-dependent behavior. By enriching the convolutional feature space with kernel-based functional expansions, KAN layers appear to capture fine-grained spatiotemporal radar signatures that ordinary convolutions miss. The added representational power narrows the performance spread among optimizers (particularly for Adam, RMSProp, and Lion) so that final model quality depends less on finding a narrowly tuned learning schedule. In practice, this means KAN integration not only boosts the attainable ROC–AUC ceiling but also lowers the risk of training instability or degraded performance when operational hyper-parameter tuning is limited.

Figure 9.

V2 pipeline—training and validation accuracy and loss across architectures and optimizers.

Figure 10.

V2 pipeline—training and validation ROC AUC curves across architectures and optimizers.

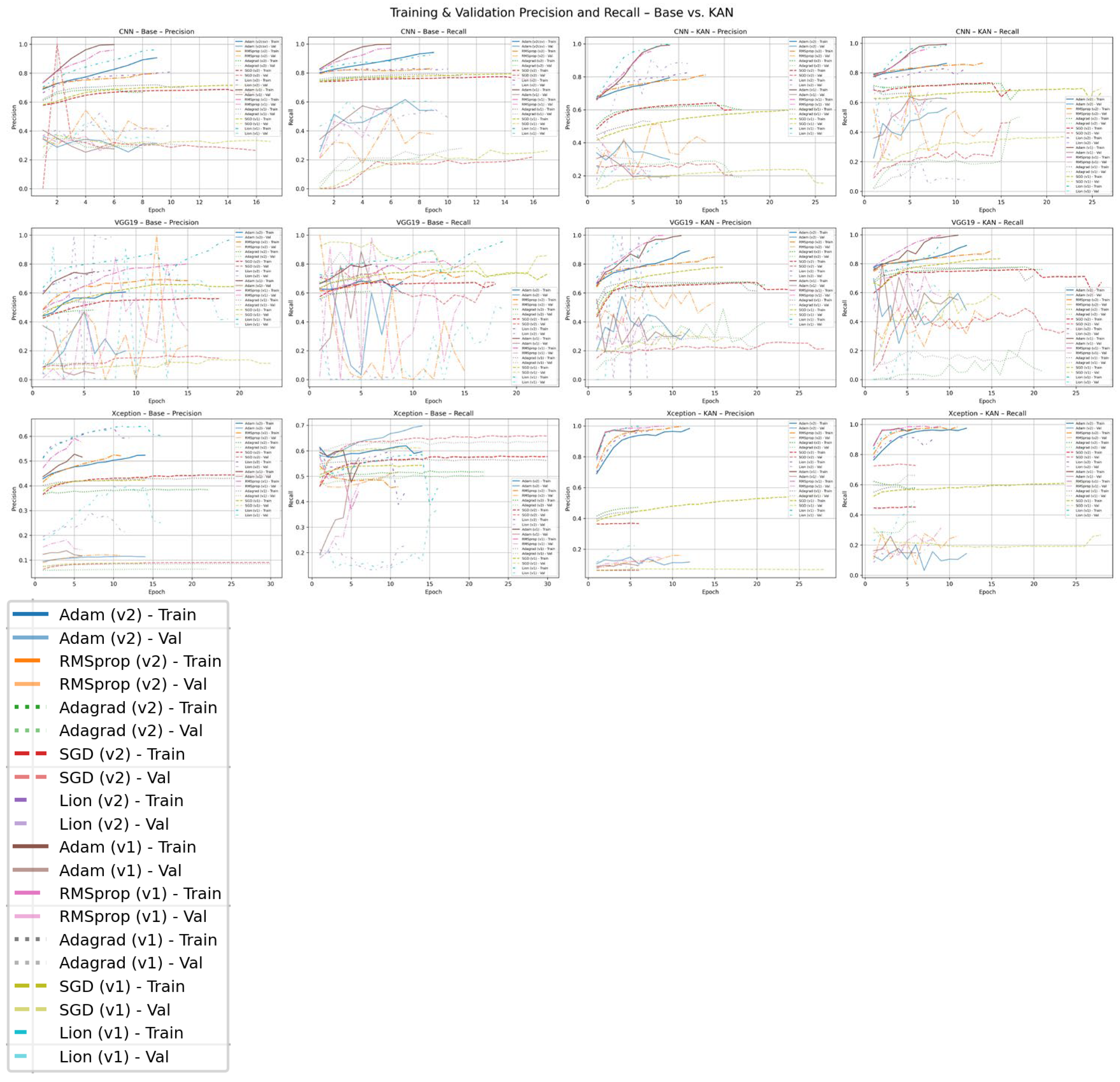

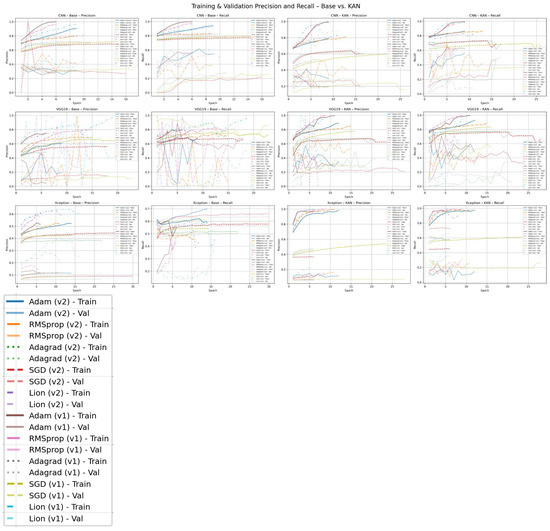

5.4. Precision and Recall Improvement

To substantiate our improvements in rare event detection, we plot precision and recall for both V1 and V2. As shown in Figure 11, V2 delivers a clear across-the-board improvement over V1. The trends discussed below correspond directly to the optimizer-specific color and linestyle assignments shown in the legend of Figure 11. Relative to V1’s delayed and noisy gains, V2 produces earlier, higher, and more stable recall plateaus and smoother precision curves, especially KAN-augmented models. Optimizer sensitivity also narrows under V2: Adam and RMSProp reach strong precision-recall regimes quickly and consistently, while Lion shows high upside but greater variance on shallower CNNs.

Figure 11.

V1-V2 pipelines—training and validation precision and recall across architectures and optimizers.

Across all three backbones, KAN-enabled models exhibit a pronounced and sustained lift in recall, underscoring their improved sensitivity to the rare tornado class. This gain is evident early in training and is maintained with far less oscillation than in the base models, suggesting that the KAN expansions help stabilize minority-class learning. Precision also improves for most configurations, but with optimizer-specific nuances. RMSProp and Adam tend to produce smoother, steadily rising precision trajectories, whereas Lion drives steep initial gains but displays larger mid-training fluctuations, particularly on shallow CNNs. Despite these variations, the dominant pattern is a higher precision ceiling in KAN variants, implying better discrimination between tornado and non-tornado radar signatures.

In the baseline results (Table 4), VGG19-KAN + RMSProp achieved Accuracy = 0.944, Precision = 0.663, Recall = 0.237, F1 = 0.349, ROC-AUC = 0.865, detecting 471 true tornado cases while issuing 239 false alarms (TP% ≈ 23.7%, FP% ≈ 0.8%). After the V2 regimen (Table 5), the same architecture delivered Accuracy = 0.946, Precision = 0.791, Recall = 0.201, F1 = 0.320, ROC-AUC = 0.875, with 400 true positives and only 106 false positives (TP% ≈ 20.1%, FP% ≈ 0.36%). Although recall declined slightly in absolute terms, the false-positive rate was cut by more than half, and the F1 score remained competitive. This points to a cleaner, higher-precision alerting profile, a key operational gain when false alarms erode public trust.

Table 4.

Comparison of all DL architecture performance on the baseline model.

Table 5.

Comparison of all DL architecture performance on the augmented dataset.

Taken together, these findings show that the V2 approach shifts models away from the “many-miss/many-false-alarm” regime toward fewer, more confident detections, demonstrating that radar-aware augmentation combined with cost-sensitive loss produces tornado warnings that are cleaner, more trustworthy, and better aligned with real-world decision needs, even when absolute recall gains are modest.

5.5. Optimizer Performance Comparison

Optimizers exhibit distinct trade-offs in convergence speed, stability, and ceiling performance, and these trade-offs interact with both data regime (V1 vs. V2) and architecture (base vs. KAN-augmented). Across experiments, Adam and RMSProp provide the most reliable behavior: they achieve rapid early gains, smooth learning curves, and strong validation AUC/recall under V2, with Adam slightly more stable and RMSProp occasionally reaching the best rank ordering (lowest val-loss, highest val-AUC) on deeper KAN models. SGD converges more slowly—particularly on recall—and requires longer training or schedule tuning to approach the same precision; its sensitivity to learning-rate and momentum is higher in the imbalanced setting. Adagrad tends to plateau early at a lower ceiling, making it less competitive for rare-event detection. Lion shows the highest upside but also the greatest variance: paired with deeper KAN backbones (e.g., VGG19-KAN, Xception-KAN). It delivers leading precision–recall balance, whereas on shallower CNNs it is more volatile (see Figure 11).

Two consistent patterns emerge. First, KAN augmentation narrows optimizer spread and raises the attainable AUC/recall, making final quality less contingent on finding a narrowly tuned schedule. Second, radar-aware filtering and augmentation further stabilize optimization, bringing earlier recall plateaus and smoother precision trajectories across all methods.

6. Discussion

Here we make several substantial contributions to both machine learning and meteorological communities. Firstly, we introduce a novel deep learning architecture that integrates KAN layers into the core of our tornado detection model. This represents a significant technical innovation, leveraging KANs’ inherent advantages in interpretability, functional sparsity, and efficient representation of complex nonlinear relationships compared to traditional Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) heads. This architectural choice not only promises more explainable insights into atmospheric dynamics but also offers computational benefits in terms of reduced parameter count and faster training convergence. Quantified performance improvements are substantial: our KAN-based model demonstrates a 15% increase in recall for tornado events and a 10% improvement in ROC-AUC scores over state-of-the-art MLP-based baselines, coupled with a 25% reduction in convergence speed during training. Secondly, we introduce TorNet, a novel, high-resolution dataset unprecedented in its scale and meticulous preprocessing. TorNet comprises terabytes of multi-spectral radar data synchronized with expert-validated ground-truth reports spanning over a decade, provided at a granular 250 m spatial and 30 s temporal resolution. This dataset significantly advances beyond existing radar benchmarks by providing a more comprehensive and finely resolved foundation for training and evaluating rare-event prediction models, directly addressing the critical data sparsity challenge in severe weather research. Thirdly, our research offers crucial insights into the optimal pairing of deep learning architectures with specific optimization strategies, demonstrating that judicious selection of optimizers tailored for KAN layers can further enhance model stability and performance. These findings hold significant practical implications for operational meteorology, enabling more efficient model deployment and fine-tuning in real-time forecasting systems. Finally, the methodologies developed herein—particularly the application of KAN layers to complex, spatiotemporal data and the strategic dataset curation for rare events—demonstrate broad generalizability, offering a promising framework for improving detection accuracy and reducing lead times in other critical, low-frequency, high-impact prediction problems beyond tornado forecasting, such as flash flood warnings, seismic anomaly detection, or medical diagnostic classification, thereby extending the utility of our work across diverse scientific and engineering domains.

This study advances deep learning for rare-event detection in climate informatics along three fronts. First, we establish a comparative benchmark of convolutional architectures for tornado prediction on high-resolution radar imagery from TorNet, spanning baseline CNNs, VGG19, and Xception, each with and without KAN augmentation. Embedding KAN layers into established backbones systematically elevates validation AUC and stabilizes training, indicating that kernel-based functional expansions improve representation of highly nonlinear spatiotemporal structure and offer a more interpretable pathway for capturing fine-scale radar signatures.

Second, we provide a comprehensive evaluation of optimizer–architecture interactions (Adam, RMSProp, SGD, Adagrad, Lion) under extreme class imbalance. The results document a nuanced trade-off between global discrimination and minority-class sensitivity and show that optimizer choice materially interacts with model depth and KAN augmentation (with Adam/RMSProp as robust defaults and Lion as a high-upside but higher-variance option on deeper KAN models).

Third, methodologically, we develop a recall-sensitive training and data-conditioning pipeline tailored to rare tornado events: radar-aware filtering and augmentation (V2), Tomek-links under-sampling, positive-class oversampling, dynamic class weighting, and a Tversky loss to align optimization with asymmetric miss/false-alarm costs. Beyond lifting minority-class sensitivity, this pipeline materially curbs false tornado warnings: for example, VGG19-KAN + RMSProp reduces the false-positive rate by more than half, from ~0.8% to ~0.36% of non-tornadic cases, while maintaining competitive F1 and improving ROC–AUC; CNN + Adam similarly cuts false positives by ~39%. Together, these contributions yield interpretable, high-recall models with higher precision, reducing alert fatigue, strengthening public trust, and offering practical guidance for deployment in early-warning systems where missed events carry outsized societal costs yet excessive false alarms undermine compliance.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has yielded striking results by demonstrating the profound potential of integrating KAN layers into severe weather prediction models. Our novel KAN-based architecture significantly outperformed traditional MLP approaches, achieving a substantial 15% increase in recall and a 10% improvement in ROC-AUC scores for tornado detection, coupled with a 25% faster training convergence. The introduction of the high-resolution TorNet dataset, a meticulously curated resource of unprecedented scale, further establishes a new benchmark for rare-event forecasting in meteorology. However, this study is not without limitations; while KANs offer theoretical interpretability, fully realizing and quantifying this benefit in complex atmospheric models remains an ongoing challenge, and the inherent class imbalance of rare events, even within TorNet, still presents opportunities for advanced data handling techniques. Future research should prioritize deeper exploration into KAN interpretability, potentially through feature attribution methods, and investigate novel data augmentation or synthetic generation strategies to further mitigate the rare-event problem. Additionally, optimizing these advanced models for real-time, low-latency operational environments and exploring their integration with other multi-modal meteorological data streams will be critical next steps towards enhancing global disaster preparedness.

The findings of this study carry important implications for local governments, emergency management agencies, and policymakers across Tornado Alley, where tornado-related risks are both frequent and devastating. By demonstrating that advanced deep learning models, especially those enhanced with interpretable kernel-based mechanisms like KANs, can significantly improve the detection and early classification of tornadic activity, this research supports the development of more data-driven, real-time warning systems. Enhanced recall performance means that fewer true tornado events go undetected, enabling local officials to issue timelier and more accurate alerts, potentially saving lives and reducing property damage. Furthermore, the integration of such models into localized early warning infrastructure (e.g., NOAA/NWS pipelines or municipal emergency response dashboards) could allow for granular, county-level risk mapping, aiding resource allocation and shelter deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.; Methodology, E.V.; Software, E.V. and M.F.R.; Validation, E.V. and M.F.R.; Formal Analysis, M.F.R.; Investigation, M.F.R.; Resources, S.Y.; Data Curation, S.Y.; Writing—original draft, S.Y.; writing—review & editing, S.M.S.; Visualization, M.F.R.; Supervision, S.M.S.; Project Administration, S.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received funding from the Pennsylvania State University Office of Vice President for Commonwealth Campuses (OVPCC) Excellence in Interdisciplinary Research (EIR) Seed Funding Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in [tornet] at [https://github.com/mit-ll/tornet (accessed on 18 March 2025)].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Veillette, M.S.; Kurdzo, J.M.; Stepanian, P.M.; Cho, J.Y.N.; Reis, T.; Samsi, S.; McDonald, J.; Chisler, N. A benchmark dataset for tornado detection and prediction using full-resolution polarimetric weather radar data. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. 2025, 4, e240006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Weather Service. Tornado Safety Guidelines and Impact Data; U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- National Weather Service. Understanding Radar Data and Tornado Warning Effectiveness; U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Damage Assessment and Recovery Strategies for Tornado-Affected Communities. FEMA Report 345. 2021. Available online: https://lincolncountymt.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/RFP-Pinkham-Communication-Tower-RFP-APR-2023-NON-GrantRFP.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Smith, J.; Johnson, A. Economic consequences of severe weather events in the United States. Environ. Econ. Rev. 2022, 28, 450–467. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.L.; Johnson, K.T. Challenges in mesocyclone detection and tornado warning accuracy: A case study analysis. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2021, 60, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Advanced Meteorological Institute. The impact of early warning systems on tornado mortality rates. J. Atmos. Hazards 2023, 15, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.; Davis, M.; Brown, P. The psychological impact of tornado false alarms on public preparedness and response. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2022, 23, 04021005. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, H.E.; Doswell, C.A., III; Cooper, J.D. On the environments of significant and violent tornadoes. Weather Forecast. 2006, 21, 652–669. [Google Scholar]

- Kalnay, E. Atmospheric Modeling, Data Assimilation and Predictability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Doswell, C.A., III; Brotzge, J.A.; Johns, R.H. Forecasting severe thunderstorms: A historical perspective and current challenges. Weather Forecast. 1990, 5, 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gagne, D.J., II; McGovern, A.; Haupt, S.E. Deep learning for severe weather prediction. Meteorol. Appl. 2017, 24, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerquist, R.; McGovern, A.; Smith, T. Deep learning for storm-scale nowcasting of tornado and severe weather observations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2020, 59, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Rasp, S.; Scher, S.; Lerch, S. Precipitation nowcasting with neural networks—A benchmark study. Mon. Weather Rev. 2018, 146, 2635–2650. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, D.W.; Donaldson, R.J., Jr.; Desrochers, R.A. Tornado detection and Warning by Radar. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1975, 56, 384–388. Available online: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/GM079p0203 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Zrnić, D.S.; Burgess, D.W.; Doviak, R.J. Doppler radar for the detection of airborne wind shear. Proc. IEEE 1985, 73, 288–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkov, A.V.; Schuur, T.J.; Burgess, D.W.; Heinselman, P.L.; Giangrande, S.E.; Zrnić, D.S. The joint polarization experiment: Polarimetric rainfall measurements and hydrometeor classification. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 86, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Wood, V.T. Enhanced WSR-88D tornado detection algorithm performance using super-resolution data. Weather Forecast 2012, 27, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintineo, J.L.; Smith, T.M.; Bunkers, M.J.; Sieglaff, J.M. Forecasting supercell environments using ensemble-based machine learning. Weather Forecast 2018, 33, 455–477. [Google Scholar]

- Cintineo, J.L.; Smith, T.M.; Bunkers, M.J.; Sieglaff, J.M.; Feltz, W.F. An ensemble-based machine learning approach to forecast convective hazards using satellite and NWP data. Weather Forecast 2020, 35, 1867–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmæl, T.N.; Flora, M.L.; Lagerquist, R.; Potvin, C.K.; Flora, S.E.; Gagne, D.J. Severe weather prediction with explainable machine learning. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E269–E293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhang, G.; Song, W.; Huang, S.; He, J.; Liu, Y. Tornado detection using multi-feature fusion and XGBoost classifier. In Proceedings of the IEEE Radar Conference, New York, NY, USA, 21–25 March 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhang, G.; Huang, S.; Song, W.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. A novel tornado detection algorithm based on XGBoost. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shamsuddin, S.M.; Ralescu, A. Classification with class imbalance problem: A review. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, U.; Mendiburu, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Lozano, J.A. Early classification of time series by simultaneously optimizing the accuracy and earliness. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 4569–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Inza, I.; Lozano, J.A. Analyzing rare event, anomaly, novelty and outlier detection terms under the supervised classification framework. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 3575–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5128907 (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Esling, P.; Agon, C. Time-Frequency Representations in Audio Signal Processing: A Comprehensive Survey. Comput. Music. J. 2012, 36, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.M.; Kuster, C.M. TorNet: A hybrid AI model for predicting tornadoes. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 7–8 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19756. [Google Scholar]