Abstract

In wireless communication, information security, and anti-interference technology, modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals has always been a key technique. Its widespread application in satellite communications, military communications, and drone communications holds broad prospects. Traditional modulation recognition techniques often rely on expert experience to construct likelihood functions or manually extract relevant features, involving cumbersome steps and low efficiency. In contrast, deep learning-based modulation recognition replaces manual feature extraction with an end-to-end feature extraction and recognition integrated architecture, where neural networks automatically extract signal features, significantly enhancing recognition efficiency. Current deep learning-based modulation recognition research primarily focuses on conventional fixed-frequency signals, leaving gaps in intelligent modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals. This paper aims to summarise the current research progress in intelligent modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals. It categorises intelligent modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals into two mainstream approaches, analyses them in conjunction with the development of intelligent modulation recognition, and explores the close relationship between intelligent modulation recognition and parameter estimation for frequency-hopping signals. Finally, the paper summarises and outlines future research directions and challenges in the field of intelligent modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals.

1. Introduction

As the electromagnetic spectrum becomes increasingly crowded and complex, the high-density, dynamic nature, and intense adversarial characteristics of spectrum resources are becoming increasingly apparent. Modern wireless communication systems face severe interference, interception, and deception threats [1], this also imposes more stringent requirements on the anti-interception capability, stability, and security of communication signals [2]. These requirements are particularly prominent in the field of military communications, effectively preventing communication signals from being intercepted or stolen by non-cooperative parties due to the broadcast characteristics of wireless channels has become a critical component within military operational systems [3]. To address these challenges, frequency-hopping spread-spectrum (FHSS) technology stands out for its exceptional interference resistance [4], anti-interception capability [5], and the advantage of low detection probability [6]. It has been widely adopted in various wireless communication systems, including military communications, satellite communications, and drone communications [7,8]. It is one of the key technologies for safeguarding communication security and ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and reliability of information transmission [9]. Therefore, frequency-hopping spread-spectrum technology plays an indispensable pivotal role in current and future military communication security systems, providing robust technical assurance for the secure transmission of wartime information and the stable operation of combat systems [10].

Frequency-hopping signals, as a key technology of significant strategic value in modern communications, operate through a core mechanism that dynamically switches carrier frequencies using a set of pseudo-random sequences [11], thereby achieving spread-spectrum transmission [12]. Unlike the traditional fixed-frequency communication method, frequency-hopping systems generate the carrier frequency, which is switched at high speed on a broader bandwidth range, based on the preset frequency-hopping pattern [13]. This mechanism significantly enhances the system’s interference resistance while improving the concealment and security of communication links. As it originates from spread-spectrum communication, it inherently inherits advantages such as resistance to multipath fading, high anti-interception capability, and excellent confidentiality [14]. Frequency-hopping communication could achieve highly efficient multi-carrier transmission because of its high-speed switching in multiple carriers. It has not only enhanced the spectrum utilisation rate and the system capacity but also made the frequency-hopping communication demonstrate the great potential of alleviating bandwidth congestion under conditions of spectrum resource scarcity, such as cellular communications [15]. Simultaneously, the highly random frequency changes of frequency-hopping signals make it difficult for adversaries to track and suppress all hopping points in real time. Traditional detection, interception, location, and jamming methods often prove ineffective, endowing frequency-hopping communication systems with outstanding anti-jamming capabilities and low interceptability [16,17]. Thanks to the above characteristics, frequency-hopping technology has been widely used in the field of military communication and electronic countermeasures since World War II, and it has gradually become the core technology of anti-interference technology, such as radar systems and cryptographic communication. With the development of the technology of frequency hopping, the superior performance of frequency-hopping communication has progressively driven its rapid development in civilian applications, and it is now widely used in scenarios with complex or constrained spectrum resources, such as drone communications, Bluetooth protocols, television broadcasting, satellite navigation systems, and indoor wireless communications [18].

However, due to the exceptional anti-jamming characteristics of frequency-hopping signals, intercepting and decrypting them has always been an extremely challenging task in electronic warfare [19]. In modern military electronic warfare, control over battlefield communications is central to the overall combat system, exerting a decisive influence on the course and outcome of warfare. Therefore, detecting and cracking the frequency-hopping signal of the enemy has essential research significance and strategic value [20]. The complete interception process of frequency-hopping signals typically involves three critical stages: detection, identification, and decryption [21]. Among these, the core task of the identification stage is modulation recognition. As the middle link between detection and demodulation of the signal, modulation recognition could accurately identify the modulation scheme of the signal under a priori parameters of the communication system scarcity [22].

Traditional Automatic Modulation Recognition (AMR) methods can be broadly categorised into two main types: Likelihood-Based Methods (LB) and Feature-Based Methods (FB) [23]. The core idea of the former is to construct a probability model for the received signal based on different modulation type hypotheses, compute the corresponding likelihood function values, and select the modulation type corresponding to the maximum likelihood value as the recognition result. Although these ways have high recognition accuracy in theory, their calculations are so complicated that it is too strict on the hardware resources, and it is too difficult to meet the requirements for real-time performance and processing efficiency, that the application scenarios are being significantly constrained [24]. In contrast, Feature-Based Methods primarily adopt the way that extracts statistical characteristics or physical features from the signal, converts these features into feature vectors, and then distinguishes between different modulation methods by utilizing a classification algorithm [25]. This approach emphasises effective signal feature representation and is often combined with traditional machine learning models (such as decision trees and support vector machines (SVMs)) to achieve modulation type identification [26]. With the rapid development of the deep learning technology, Feature-Based Methods have gained new momentum for development. Recently, researchers have applied various neural network models to modulation recognition tasks, such as convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. There are so many experimental results that demonstrate that deep learning-based modulation recognition algorithms generally outperform traditional methods in recognition accuracy and system robustness, showcasing broad application prospects [27].

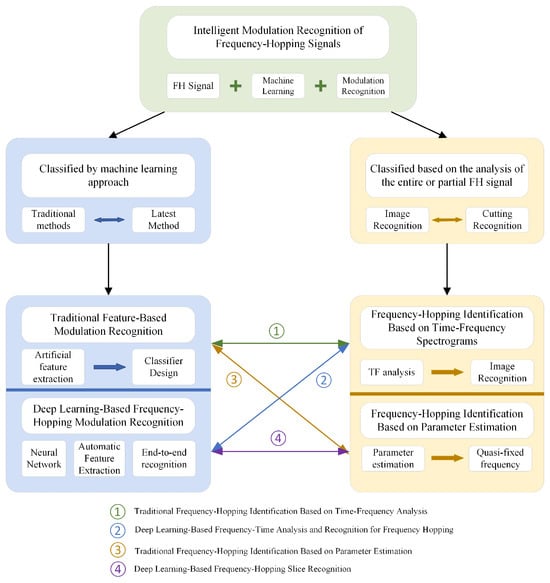

Current intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals could be broadly categorised into two types: the first one is to analyse and transform the entire frequency-hopping signal, extracting features or performing preprocessing before submitting it to a classifier for recognition; the second one is consists of segmenting the signal based on the hopping period or employing de-hopping techniques to convert it into quasi-fixed-frequency signals, thereby enabling the application of traditional fixed-frequency signal modulation recognition methods. Essentially, both methods fall under feature-based modulation recognition techniques.

Due to the non-stationary nature of frequency-hopping signals, significant gaps remain in the intelligent modulation recognition of such signals. The primary challenges encountered include the following aspects:

- The inherently non-stationary nature of frequency-hopping signals makes it difficult for single-domain features in either the time or frequency domain to characterise their signal properties fully. Therefore, to recognise the modulation ways of the frequency-hopping signal successfully, it is necessary to search for richer and multidimensional features to demonstrate the dynamic changes of the frequency-hopping signal in the fields of time and frequency.

- Frequency-hopping signals are primarily employed in military communication environments, where they frequently encounter complex and intense noise interference. Although their spread-spectrum characteristics confer a degree of noise resistance, under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, the relevant features of frequency-hopping signals—such as their time–frequency spectrum—remain susceptible to masking by noise, significantly increasing the difficulty of modulation identification.

- Frequency-hopping communication systems are usually categorised into fast-hopping and slow-hopping types. Fast-hopping systems undergo multiple frequency-hopping cycles within each symbol period, resulting in a more discrete and complex distribution of modulation characteristics across the frequency dimension. This significantly increases the difficulties of feature extraction and modulation recognition. In contrast, slow-hopping systems have become the primary focus of current modulation recognition research due to the relative stability of their modulation characteristics in both the time and frequency domains. However, to maintain the excellent anti-interference performance of frequency-hopping signals, the number of bits is limited in a single hopping cycle, even in a slow-hopping system. So, the rare message of the limited bits becomes the challenge of recognizing the way of the modulation of the frequency-hopping signal.

Based on a systematic review of the existing literature and methods in the field of intelligent modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals, this paper systematically reviews and organises the research progress in intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals over the past decade. It categorises and summarises the primary existing methods, and, combined with the mathematical characteristics of frequency-hopping signals, conducts an in-depth analysis of the applicability and performance differences of various techniques in different application scenarios. The main contributions of this paper can be summarised as follows:

- This paper systematically organises intelligent modulation recognition techniques for frequency-hopping signals from two research perspectives: First, it compares traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches based on the adopted learning paradigm. Second, it distinguishes between two technical routes based on signal processing methods—whether frequency-hopping point slicing is performed or not.

- This paper prospectively outlines future development directions for intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals. It proposes a series of potential research paths likely to drive continuous progress in this field.

- This research partially fills the gap in systematic reviews within this field, providing valuable reference and research support for subsequent theoretical exploration and engineering implementation of intelligent modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 investigates the principles of frequency-hopping communication systems and frequency-hopping signal models, introducing several commonly used time–frequency analysis methods. Section 3 discusses the applications and limitations of traditional intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals. Section 4 explores deep learning-based intelligent modulation recognition techniques for frequency-hopping signals. Section 5 describes the primary parameter estimation methods for frequency-hopping signals. Section 6 outlines the challenges of modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals and future research directions. Finally, Section 7 provides a summary of this paper. The structure of this paper is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure and layout of this article.

2. Fundamental Theory of Frequency-Hopping Communication

2.1. Frequency-Hopping Communication System Model

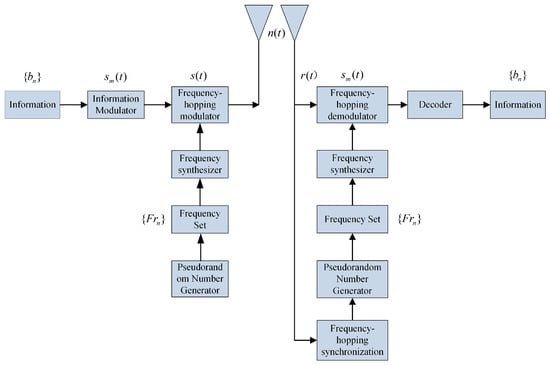

Frequency-hopping signals are second-order modulated signals, where the carrier frequency jumps between multiple preset frequencies according to a specific pattern controlled by a pseudo-random sequence. To achieve effective transmission and reception of frequency-hopping signals, the transmitter and receiver in a communication system must share the same pseudo-random frequency-hopping sequence and maintain precise time synchronisation. The strict synchronisation requirement significantly enhances the anti-interference and anti-interception capabilities of frequency-hopping communication systems, which makes them particularly effective in high-threat environments such as battlefield communications. Consequently, they are widely adopted. The basic structure of a frequency-hopping communication system is illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Basic structure of frequency-hopping communication systems.

As shown in Figure 2, at the transmitter, the original information sequence first undergoes baseband modulation by the modulator to generate the transmission-ready signal , where is the modulation amplitude and is the pulse shaping function. Simultaneously, the pseudo-random code generator produces the frequency-hopping set , which controls the frequency synthesiser to rapidly switch the carrier frequency based on the preset frequency set. The frequency-hopping modulator mixes the baseband signal with the dynamically varying carrier to generate the RF signal , which pseudo-randomly hops between multiple frequency points. At the receiver, the system receives the signal , where represents the noise interference encountered during transmission. The frequency-hopping synchronisation module captures and tracks the transmitter’s frequency-hopping sequence and timing information, ensuring strict synchronisation between the local pseudo-random code and the transmitter. This synchronisation sequence drives the local frequency synthesiser to generate a matched local oscillator signal in real time, enabling de-hopping processing of the received signal. This restores it to an intermediate frequency or baseband signal . Subsequently, the demodulator demodulates and decodes the signal, recovering the original information .

As shown in Equation (1), Shannon’s formula indicates that if the capacity of the channel remains unchanged, the communication system can transmit signal at a lower SINR by increasing the width of the transmission signal. Therefore, increasing the bandwidth of the transmitted signal could enhance the reliability and robustness of the communication system. As shown in Figure 3, owing to its outstanding anti-interference and anti-interception capabilities, frequency-hopping signals are widely employed in communication scenarios demanding high confidentiality, such as military communications, drone communications, and satellite communications. This approach not only enhances system security and stability but also provides robust assurance for information transmission in complex environments. As shown in Figure 4, the modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals exhibit complex and diverse characteristics, making it difficult for a single classification dimension to comprehensively summarise their intelligent modulation recognition features. Based on this, this paper discusses intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals from two distinct classification perspectives, aiming to reveal their underlying patterns more systematically.

Figure 3.

Frequency-hopping communication system scenario diagram.

Figure 4.

Conceptual Diagram of Frequency-Hopping Modulation Recognition Technology.

2.2. Frequency-Hopping Communication Signal Model

Since the carrier frequency of the frequency-hopping signal switches over time according to a predetermined pseudo-random sequence, this frequency-switching behaviour causes it to demonstrate different frequency characteristics at different moments, with its spectral structure dynamically changing over time. Consequently, the autocorrelation function of a frequency-hopping signal depends not only on the time difference but also significantly on absolute time. From the perspective of time–frequency analysis, frequency-hopping signals are typical examples of non-stationary signals. Their mathematical model is as follows:

Here, A represents the amplitude of the frequency-hopping signal, denotes the carrier frequency of the i-th hopping signal, is the signal’s frequency-hopping period, and is Gaussian white noise with mean zero and variance . represents the frequency-hopping rate, serving as a key metric for evaluating signal speed. denotes a rectangular pulse with width . is the phase function, typically encoding the modulation information of the frequency-hopping signal; different modulation schemes correspond to distinct phase variation characteristics.

The single-hop frequency-hopping periodic signal is

Let use different frequencies at different times and , then its autocorrelation function is

As shown in Equation (5), its autocorrelation function varies with absolute time, demonstrating the characteristic non-stationarity of frequency-hopping signals.

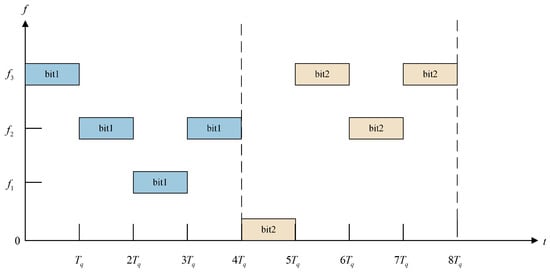

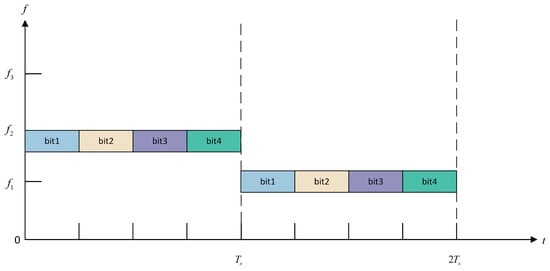

Based on the ratio between the frequency-hopping period and the code symbol period, frequency-hopping signals can be categorised into fast and slow frequency hopping. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show that represents the frequency-hopping period in fast frequency-hopping systems, while denotes the frequency-hopping period in slow frequency-hopping systems. The signal will be called a fast frequency-hopping signal when its frequency-hopping cycle is shorter than the code cycle. In this mode, a single code element often spans multiple frequency-hopping cycles and undergoes repeated frequency changes, significantly enhancing anti-interference capabilities. However, the rapid frequency changes also pose significant challenges for receivers in terms of high-frequency estimation accuracy requirements and increased processing complexity when receiving information. Therefore, despite the strong anti-interference capabilities of fast frequency-hopping signals, their modulation identification remains a major technical hurdle, with relatively scarce research in this area.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of time–frequency characteristics during fast frequency-hopping signal transmission.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of time–frequency characteristics during slow frequency-hopping signal transmission.

Relatively speaking, when the frequency-hopping cycle is longer than the code symbol period (i.e., the ratio is greater than 1), it is referred to as a slow frequency-hopping signal. Such signals can carry multiple code symbols within each frequency-hopping cycle, typically around a dozen. Although the interference resistance of the slow frequency-hopping signal is not as good as that of the fast frequency-hopping signal, it could operate in inferior receiving and transmitting hardware. They offer advantages such as lower implementation complexity, reduced cost, and lower power consumption, making them more widely adopted in practical communication systems. Since a single frequency-hopping cycle contains multiple code symbols, it satisfies the minimum number of symbols required for modulation recognition. Early research typically analysed a segment of a single frequency-hopping cycle to accomplish modulation recognition tasks.

2.3. Common Time–Frequency Analysis Methods

As mentioned earlier, it would not comprehensively reveal the modulation characteristics if we only analysed the frequency-hopping signal in the time or frequency domain, and it would lose a lot of information. Time–frequency analysis, however, simultaneously captures the energy distribution features across both time and frequency dimensions, making it well suited for non-stationary signals.

Typical time–frequency analysis techniques include the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), Wigner–Ville Distribution (WVD), and Choi–Williams Distribution (CWD). These will be briefly introduced below.

(1) Short-Time Fourier Transform

The Short-Time Fourier Transform is a classic time–frequency analysis method. Its fundamental principle is to split the signal into multiple short-time segments and then perform a Fourier transform on each segment. By adding a time-sliding window function, the STFT could demonstrate the whole dynamic frequency variations of a signal over time. It addresses the deficiency of the traditional Fourier transforms, which have lacked temporal resolution when analysing non-stationary signals, so that STFT could achieve a joint characterisation of the signal’s characteristics of time and frequency. The formula is as follows:

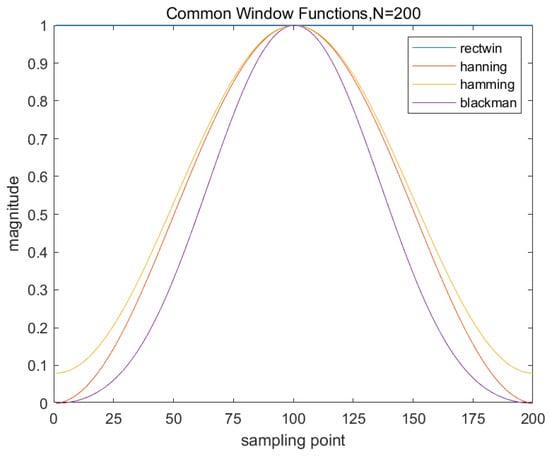

In the Equation (6), represents the frequency-hopping signal, and denotes the complex conjugate of the window function. The primary function of window functions is to constrain the analysis range of the signal before the Fourier transform and optimise its spectral characteristics. Common window functions include the rectangular window, Hanning window, Hamming window, and Blackman window. As shown in Figure 7, we compared the time-domain waveforms of different window functions. Each window function exhibits distinct characteristics in frequency resolution and side-lobe suppression performance. The main lobe width and side-lobe height directly influence frequency resolution and spectral leakage suppression effectiveness. Therefore, window functions should be selected appropriately based on specific application requirements to achieve the optimal balance between resolution and suppression performance.

Figure 7.

Comparison chart of different window function waveforms.

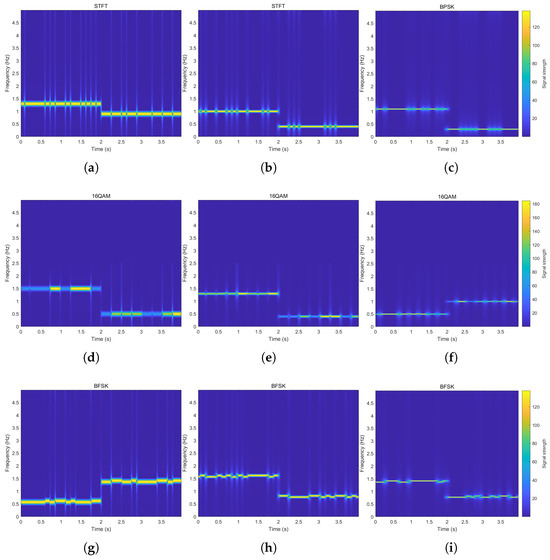

The width of the window function plays a decisive role in determining the time–frequency resolution of the resulting time–frequency spectrum plot. As shown in Figure 8, a longer window function could enhance the frequency domain resolution, but it will lose time domain resolution; conversely, a shorter window function improves time domain resolution at the expense of frequency domain resolution. This trade-off stems from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle constrains the relationship between a function (or signal) and its Fourier transform, essentially embodying the non-simultaneity of point and wave properties. Because the STFT employs a fixed window function, performing Fourier analysis on local segments as the window function slides, it inevitably adheres to the uncertainty principle—time and frequency resolution cannot be achieved simultaneously. Therefore, in practical applications, the window function length must be selected judiciously based on signal characteristics to achieve an appropriate balance between time and frequency resolution.

Figure 8.

Time–frequency plots of frequency-hopping signals with different window lengths. (a) BPSK window length 64; (b) BPSK window length 128; (c) BPSK window length 256; (d) 16QAM window length 64; (e) 16QAM window length 128; (f) 16QAM window length 256; (g) BFSK window length 64; (h) BFSK window length 128; (i) BFSK window length 256.

Jiacheng Wu [28] proposed a method based on STFT spectrograms and CNNs for modulated signal recognition in frequency-hopping systems. This approach first converts the intra-pulse sequence of the signal into a greyscale spectrogram via STFT, thereby transforming the modulation recognition problem into an image recognition task. Subsequently, the spectrogram is directly fed into the CNN, which automatically learns and extracts features from the spectrogram for classification. Anshul Tailor et al. [29] proposed a method based on STFT spectrograms and deep convolutional neural networks to address the challenge of modulating complex multi-carrier signals in non-cooperative communication scenarios. After obtaining spectrograms via STFT, the method sequentially employs four CNN models for classification, and it was trained and tested on a dataset comprising 10 modulation schemes, including FBCM_QAM16 and FOFDM_QAM16. Results demonstrate that it maintains approximately 90% recognition accuracy even at a signal-to-noise ratio of −10dB, exhibiting strong robustness.

Suqin Wu et al. [30] combined the STFT with unsupervised feature learning networks. By introducing two distinct STFT computation mechanisms, they constructed unsupervised feature learning networks based on convolutional restricted Boltzmann machines (CRBMs) and restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs), respectively. These networks extract the time–frequency features of the signal to achieve intelligent modulation recognition. Sidra Ghayour Bhatti et al. [31] proposed a novel phase-based radar signal modulation recognition method. By integrating the STFT with a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network and analysing phase spectral features, they solved the low recognition rate of phase-encoded signals under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions. Jie Yang et al. [32] integrated a convolutional denoising autoencoder with a convolutional neural network. The autoencoder restores key features from the STFT-derived time–frequency map under low SINR, enabling classification via the CNN.

As can be seen, although the Short-Time Fourier Transform has relatively low frequency resolution and poor time–frequency concentration, its computational complexity is low, making it well suited for real-time signal processing.

(2) Wigner–Ville distribution

WVD is a typical quadratic time–frequency distribution method, first proposed by Wigner in 1932 within the field of quantum mechanics. Subsequently introduced into signal processing by Ville in 1948, it has driven its widespread application and continuous development in time–frequency analysis. Compared to the STFT, the WVD theoretically achieves optimal time–frequency resolution. Its energy distribution is concentrated along the instantaneous frequency trajectory of the signal, which has overcome the limitations imposed by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle on time–frequency resolution. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

It can be seen that the WVD transform does not employ a windowing strategy. Instead, it obtains the time–frequency characteristics by performing a Fourier transform on the autocorrelation function of the signal’s time delay function . Although WVD theoretically achieves optimal time–frequency resolution because of its energy distribution closely following the signal’s instantaneous frequency trajectory, it tends to generate numerous cross terms when processing multiple signal quantities. It severely damaged the clarity and interpretability of the time–frequency representation, posing substantial challenges for subsequent analysis. Suppose a signal consists of multiple component signals.

Its WVD transformation is

Compared to single-signal WVD, multi-component signals introduce additional cross-term transformations that interfere with the results:

To suppress these cross-term interferences, researchers applied windowing to the time domain of the WVD, thereby obtaining

By applying windowing, the PWVD transform smooths multiple quantity signals. Although it loses some time–frequency resolution, the adverse effects of cross-term interference are effectively reduced. Researchers have proposed simultaneous windowing in both the time and frequency domains to further suppress the impact of cross-term interference. Smoothing the signal using two window functions achieves superior performance in eliminating cross-term interference. Its expression is

Here, represents the time-domain window function, and denotes the frequency-domain window function. Compared to PWVD, SPWVD involves more complex computations and is suitable for large-scale algorithmic research. Due to its high spatio-temporal resolution and strong resistance to cross-term interference, many scholars have chosen SPWVD for spatio-temporal analysis of frequency-hopping signals. The resulting spatio-temporal spectrograms are then used as inputs for neural networks to perform modulation classification [33,34,35], yielding favorable results.

Kuixian Li et al. [36] proposed a digital communication signal modulation recognition method based on convolutional neural networks and feature fusion. They classified the signal by extracting image features transformed by the SPWVD transform for fusion. Zilong Wu et al. [37] proposed a radar signal modulation recognition algorithm based on doubly cubic interpolated Wigner–Ville distributions. The algorithm directly trains a convolutional neural network on square matrices obtained by doubly cubic interpolation of WVD matrices, thereby avoiding numerical changes that may occur during automatic storage and retrieval. Experimental results demonstrate strong recognition capabilities under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions.

(3) Choi–Williams distribution

CWD is one of the functions in the Cohen-Kries distribution series, and it is also a smoothed form of the WVD. Proposed by Hyung-Ill Choi and William J. Williams in 1989 [38], it suppresses cross-terms by introducing an exponential kernel function while maintaining high time–frequency resolution. Its formula is as follows:

As a smoothing variant of WVD, CWD inherits its nonlinear quadratic representation, theoretically offering extremely high time–frequency resolution without the constraints of fixed windows. Its parameter controls the degree of smoothing: larger values preserve more of WVD’s high-resolution characteristics, while smaller values enhance smoothing to suppress cross terms. However, similar to SPWVD, CWD may still exhibit residual cross-terms for multi-component signals, particularly when signal components have closely spaced or overlapping frequencies. This can introduce artifacts in the time–frequency plot. Furthermore, CWD’s high-resolution properties are highly dependent on the kernel parameter. Its time–frequency resolution and cross-term suppression performance exhibit varying degrees of bias and skewness as this parameter is adjusted. This trade-off limits the effectiveness of CWD in analysing certain complex signals, such as those with strong noise or rapid variations.

Xiaodi Tian et al. [39] proposed a method based on fractional low-order Choi–Williams distribution (FLO-CWD) and CNN to address the problem of identifying modulation schemes for communication signals in non-Gaussian impulse noise environments. This approach uses the time–frequency map obtained via FLO-CWD as image input to the designed CNN for automatic feature extraction and classification recognition. However, the experimental validation of this method was limited to 2ASK, 2FSK, and 2PSK signals, representing a relatively restricted range of modulation types.

Borong Zou et al. [40] proposed a convolutional neural network method based on the Choi–Williams time–frequency distribution spectrum and the Inception module to address the low accuracy of traditional radar signal recognition methods in complex electromagnetic environments. They use the time–frequency spectrum, which is transformed by the CWD transformation, as the input to the CNN model, which involves two asymmetric four-channel Inception structures. Parallel multi-scale convolutions enable coordinated feature extraction across network depth and width, with signal recognition achieved through global average pooling and a Softmax classifier. Shitong Li et al. [41] converted radar signals into time–frequency images using the Choi–Williams distribution and the Averaged Fuzzy Contour Line (AFCL). They extracted fused texture features using the Grey-Level Gradient Co-occurrence Matrix (GLGCM). Then, they combined this with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier to achieve modulation recognition of LPI radar signals in low signal-to-noise ratio environments. Siqin Ning et al. [42] enhanced time–frequency features obtained via bicubic interpolation, threshold segmentation, and linear stretching of CWD transforms. These features were fed into the RA-CNN network, which has residual attention modules. This method resolved the challenge of identifying mixed-modulation signals in Joint Communication Radar (JCR) systems under small-sample conditions.

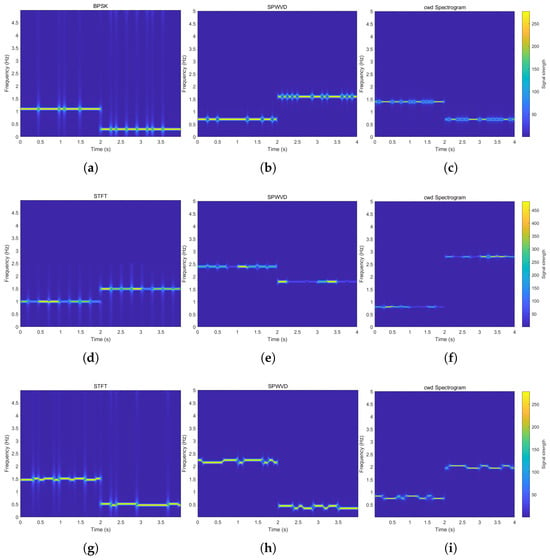

The core challenge of the time–frequency analysis lies in balancing between cross-term suppression, time–frequency resolution, and computational complexity. As shown in Figure 9, we simulated and compared three time–frequency analysis methods: STFT, CWD, and SPWVD. The STFT effectively avoids cross-term interference by adding the window function. Still, its resolution is constrained by the fixed window length. The Wigner–Ville distribution offers superior time–frequency resolution but is prone to generating significant cross-terms. Conversely, the Smooth Pseudo-Wigner–Ville distribution and CWD sacrifice resolution to some extent to achieve effective cross-term suppression, reflecting a trade-off between practicality and precision. The selection of specific methods should comprehensively consider signal characteristics and the actual requirements of the analysis task. Table 1 summarises the advantages and disadvantages of mainstream time–frequency analysis methods.

Figure 9.

Comparison of several time–frequency analysis methods for frequency-hopping signals. (a) STFT_BPSK; (b) SPWVD_BPSK; (c) CWD_BPSK; (d) STFT_16QAM; (e) SPWVD_16QAM; (f) CWD_16QAM; (g) STFT_ BFSK; (h) SPWVD_ BFSK; (i) CWD_ BFSK.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of several time–frequency analysis methods.

3. Traditional Intelligent Modulation Recognition Methods for Frequency-Hopping Signals

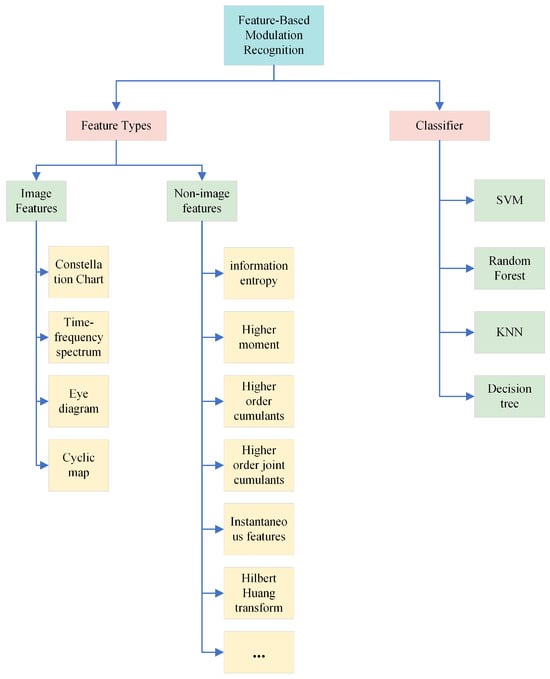

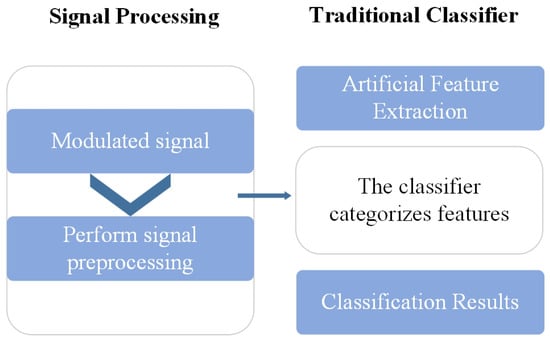

With the continuous advancement of science and technology, signal modulation recognition is progressively moving toward intelligent solutions. Its core task is to automatically determine the modulation scheme employed in a received signal without requiring human intervention or predefined conditions. To achieve this goal, it is typically necessary to conduct an in-depth analysis of the signal’s time domain, frequency domain, and other higher-order statistical features. This analysis is combined with advanced technologies, including machine learning, deep learning, and pattern recognition, to enable the autonomous and highly accurate identification of modulation types. To date, intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals can be broadly categorised into two main types: traditional intelligent modulation recognition methods and deep learning-based intelligent modulation recognition methods. Traditional intelligent modulation recognition methods are primarily divided into two kinds: likelihood-based approaches and feature extraction-based approaches. Due to the rapid frequency changes and high uncertainty inherent in frequency-hopping signals, the computational complexity of Likelihood-Based Methods is significantly increased. Consequently, researchers often favour feature extraction techniques, which simplify the problem and enhance recognition efficiency by extracting key signal characteristics. Feature-based modulation recognition does not require complex, rigorous likelihood functions. Instead, it focuses on extracting representative features of the signal to be identified—such as I/Q sequences, amplitude, phase, higher-order moments, and constellation diagrams—and then classifying the signal using specific classifiers based on different feature information. Standard classifiers include decision trees, k-nearest neighbors, and support vector machines (SVMs). We summarise the commonly used signal features and classifiers in Figure 10. These methods are used widely due to their low computational complexity and high recognition accuracy, which improve the efficiency of the operation in modulation recognition. The algorithmic flow for feature-based modulation recognition is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Feature-based modulation recognition algorithm flowchart.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of fast frequency-hopping signal.

Guo Zhaoyi et al. [43] proposed a frequency-hopping signal estimation and classification method that is based on improved connected region labelling. This method adopts the local window-based energy thresholding technique for denoising the signal’s time–frequency domain, utilises an improved connected region labelling graph for parameter extraction, and applies a clustering algorithm for signal classification and identification. Yang Ruijing et al. [44] designed a spectrum-based reception method that is based on the signal’s hopping pattern for frequency-hopping communications. It performs preliminary classification of received signals using their time–frequency spectra, converts them into complex sequences, and identifies their internal structures using fourth-order cumulants.

The intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals can be categorised into two types based on whether slicing processing is applied, as follows: time–frequency analysis-based frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition methods and parameter estimation-based frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition methods.

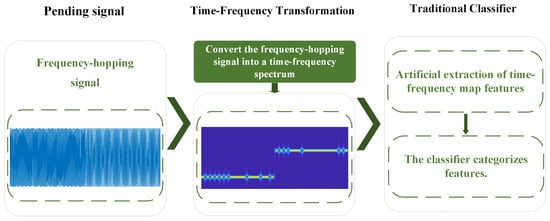

3.1. Traditional Intelligent Modulation Recognition Methods for Frequency-Hopping Signals Based on Time–Frequency Analysis

Currently, the purpose of frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition methods based on time–frequency analysis is to transform one-dimensional signal processing problems into two-dimensional image recognition tasks. In early research, scholars usually completed the modulation recognition by artificially extracting the features from time–frequency plots and then combining them with traditional machine learning classifiers. The workflow is illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Traditional intelligent modulation recognition algorithm flow for frequency-hopping signals based on time–frequency analysis.

Li Hongguang et al. [45] proposed a frequency-hopping modulation scheme identification method based on time–frequency energy spectrum texture features to address the identification problem of frequency-hopping communication modulation schemes. This method utilised the manual to calculate the histogram statistical characteristics of the frequency-time energy spectrum greyscale image of the frequency-hopping signal, which is transformed by the WVD transformation, and then combined it with greyscale symbiotic matrix features to form a 22-dimensional feature vector. Subsequently, they achieved the modulation recognition of the frequency-hopping signal by utilising the SVM to train and classify the extracted features. Building upon this, Gu Zhigang et al. [46] constructed a 20-dimensional raw feature set by extracting geometric invariant moments, pseudo-Zernike moments, and Rayleigh entropy from the time–frequency energy map. They then utilised an improved Q-learning algorithm to build a Markov decision model, integrating reinforcement learning features to accomplish frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition. However, this approach exhibits high computational complexity during feature selection, requiring multiple iterations of SVM training and feedback updates, which limits its real-time applicability.

Wang Guan et al. [47] proposed a frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition method based on Gabor texture features and support vector machines. Gabor filters extracted texture features from the time–frequency spectrum obtained via CWD transformation. Subsequently, they achieved the modulation recognition of six frequency-hopping signals by utilising the texture feature vector, which is dimension-reduced by PCA, to input into the SVM. This method achieves a recognition rate of 90.67% even at a low signal-to-noise ratio of −8 dB, demonstrating high robustness.

However, time–frequency analysis-based intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals often rely on the resolution of time–frequency images and the recognition capabilities of classifiers. In practical applications, it is still a significant challenge to obtain sufficient and high-quality time–frequency plots of frequency-hopping signals in the complex and ever-changing environment of military confrontation; the lack of training data samples always constrains the application of this method. Simultaneously, for frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition, current research primarily focuses on reducing the noise of the time–frequency image obtained in low signal-to-noise ratio environments, with no more profound breakthroughs achieved thus far.

In summary, although recognition methods based on time–frequency analysis demonstrate significant potential, they still face challenges such as data scarcity and low signal-to-noise ratio, necessitating further technological innovation and breakthroughs.

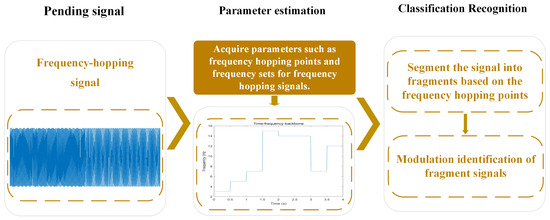

3.2. Traditional Intelligent Modulation Recognition Methods for Frequency-Hopping Signals Based on Parameter Estimation

Each hopping signal can be approximated as a fixed-frequency signal with a constant carrier frequency over time for slow-hopping frequency systems. Therefore, researchers proposed another method for identifying frequency-hopping signal modulation, the original modulation identification approach for frequency-hopping signals. They first obtained the hopping points of the frequency-hopping signal by parameter estimation, then they sliced the frequency-hopping signal at these hopping points to obtain the segments of conventional fixed-frequency signals with stable carrier frequencies. These sliced signals could be analysed by the method of modulation recognition of the standard fixed-frequency signal because of the sufficient quantity of bits that they have. The defining characteristic of these methods is their requirement for knowledge of the frequency-hopping signal’s switching points to enable precise slicing. Consequently, this method heavily relies on the accuracy of parameter estimation and the number of code elements contained within a single hopping cycle. In frequency-hopping signals with high symbol density during single-hop cycles, this method preserves information most completely, minimizing data loss during signal processing. Consequently, it has gained widespread favor among researchers and finds extensive application in slow-hopping frequency-hopping systems. Similarly, this method is also divided into traditional intelligent modulation recognition approaches and deep learning-based methods. This section primarily focuses on introducing traditional frequency-hopping intelligent modulation recognition. The general workflow is illustrated in Figure 13:

Figure 13.

Traditional intelligent modulation recognition algorithm flow for frequency-hopping signals based on parameter estimation.

Early researchers typically achieved preliminary classification of frequency-hopping signals by slicing them into segments. They manually designed feature extraction methods based on the differences in characteristics between various modulation schemes within a single hop cycle, set corresponding thresholds, and combined multiple threshold decisions. However, poor robustness under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions and low recognition rates limited their practicality and widespread application. Feng Li et al. [48] proposed a novel algorithm for fast frequency-hopping systems that combines the Short-Time Fourier Transform with the augmented Lagrange multiplier (ALM) method, achieving relatively satisfactory classification results for fast frequency-hopping signals modulated using FFH-BPSK and FFH-BFSK. Building upon this foundation, Deng Ke et al. [49] further expanded artificially extracted modulation features to construct a tree classifier, achieving effective recognition of seven modulation types: 2ASK, 4ASK, 2FSK, 4FSK, 2PSK, 4PSK, and 16QAM.

However, this method has several disavantages, such as high algorithmic complexity with the algorithm, and it needs to extract different features multiple times in the classification process, which makes it difficult to classify the frequency-hopping signal rapidly and effectively. Jixiang Wu et al. [50] proposed a frequency-hopping signal feature extraction method based on fuzzy function theory to address this issue. The authors extracted global features from AFMR slices, which include information on the fields of time and frequency within single-hop signals to form feature vectors. They then classified frequency-hopping signals using the FCM clustering algorithm.

To address the issue of limited information carried by code symbols during single-hop periods in frequency-hopping signals, Chen Bozhe et al. [51] proposed a method utilising support vector machines (SVMs) to process three features of single-hop signals that are less susceptible to small sample sizes for frequency-hopping signal recognition. The authors analysed features suitable for recognising small-sample frequency-hopping slice signals and those less affected by multipath interference. They constructed two-dimensional feature parameters by combining them in pairs and employed SVMs for classification. Simulation results demonstrate that BPSK, QPSK, and MSK signals achieve recognition rates exceeding 90% at signal-to-noise ratios ranging from −5 to 5 dB. This approach exhibits enhanced robustness under low SINR and multipath channel conditions, opening broader application possibilities.

As shown in Table 2, we summarise the advantages and disadvantages of traditional frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition techniques and deep learning-based frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition techniques. In Table 3, we summarise the traditional modulation recognition methods employed in some of the literature.

Table 2.

Comparison of traditional frequency-hopping modulation recognition and deep learning-based frequency-hopping modulation recognition.

Table 3.

Conventional frequency-hopping signal modulation identification methods.

4. Deep Learning-Based Intelligent Modulation Recognition Method for Frequency-Hopping Signals

4.1. Advances in Deep Learning-Based Intelligent Modulation Recognition for Frequency-Hopping Signals

Recently, with the advantages that the deep learning technology has with learning characteristics automatically and smart sorting from the raw data, it has made significant progress in multiple fields such as computer vision, speech recognition, and natural language processing. This highly efficient automated feature extraction and processing capability has gradually positioned deep learning as a key direction in modulation recognition research. In deep learning-based modulation recognition for communication signals, the mainstream approach feeds the signal’s I/Q sequence into a neural network. The network then extracts features from the I/Q sequence automatically for classification. It has made a significant increase in computational efficiency and accuracy because the process of artificial feature extraction of traditional intelligent modulation recognition is completed by the neural network, which has enhanced performance. Y. Zhang et al. [52] employed a one-dimensional residual network to extract temporal features from I/Q signals, and they introduced the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanism, combining with an extended short-term memory network to adaptively enhance key feature expression capabilities and uncover temporal correlation characteristics; however, this method only analyses the time-domain characteristics of the signal, leading to misclassification when processing similar signal sources such as WBFM and AM-DSB, and making it difficult to effectively distinguish between the two. M. Zuo et al. [53] transformed the I/Q components of the received signal into amplitude-phase separated polar coordinates. They extracted features through multi-layer 1D convolutions, finding the key characteristics by the attention mechanism to adjust the weight of the network dynamically. The method suppressed noise, effectively achieving the modulation recognition of the I/Q sequences. However, when the noise intensity exceeds the signal intensity, the recognition rate of this method drops significantly.

To address the scarcity of signal samples, Z. Wang et al. [54] employed a conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) framework. They reconstructed the signal by incorporating the deconvolution layers in the generator, complete end-to-end identification by combining the CNN and CLDNN classifiers, and achieved highly accurate modulation recognition in the small sample condition.

Zhang Xueqin et al. [55] integrated signal detection with modulation recognition, proposing a joint method based on time-convolutional long short-term memory (TLNet). Experimental results demonstrate that TLNet exhibits higher efficiency and performance in both signal detection and modulation recognition tasks than traditional neural network approaches.

Lu Weidong et al. [56] proposed an automatic modulation recognition method based on feature fusion. They first utilise an Atrial Space Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module, which is combined with channel attention and spatial attention mechanisms to extract and enhance the expressive capability of key spatial features across multiple scales. Finally, they achieved modulation recognition of the low SINR signals by fusing the shallow-layer features with the deep-layer features extracted from long short-term memory (LSTM) networks for modulation type classification.

However, because the frequency-hopping signals possess typical non-stationarity, the modulation information of the frequency-hopping signal cannot be demonstrated entirely by a conventional I/Q sequence. To address this, researchers propose performing time–frequency analysis on frequency-hopping signals to simultaneously capture their energy distribution characteristics across both time and frequency dimensions. This method clearly reveals the trajectory of frequency changes over time in frequency-hopping signals and demonstrates excellent adaptability to non-stationary signals. Furthermore, the difficulties of the modulation recognition could be converted from the field of one-dimensional sequence analysis into the field of two-dimensional image recognition by inputting the time–frequency plot as the characteristics into the modulation recognition network model. This method demonstrates superior recognition performance compared to traditional methods in practical applications.

Juan Zhang et al. [57] employed the WVD transform to convert five frequency-modulated signals (Const, LFM, SFM, PFM, and FSK) into time–frequency images. These were then directly input into a CNN for end-to-end modulation recognition. Results demonstrated an overall error rate below 7.2% across signal-to-noise ratios ranging from −4 dB to 15 dB, addressing the limitations of traditional manual feature design—namely, its strong dependency on manual selection and low recognition rates under low SINR conditions. Li Yuqian et al. [58] employed SPWVD to transform signals into colour time–frequency maps. They combined convolutional neural networks to extract deep features and integrated Local Binary Pattern (LBP) texture features. Finally, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce the dimensionality of the high-dimensional fused features, enabling recognition of 10 modulation signals. Results show this method achieves an average recognition rate of 84.5% at 0 dB signal-to-noise ratio, demonstrating strong robustness under low signal-to-noise conditions.

Weinan Wang et al. [59] proposed a modulation recognition method based on SPWVD time–frequency analysis and ResNet. They suppressed noise and crosstalk interference by SPWVD, which converted the signal into a high-resolution greyscale time–frequency map. It fine-tunes a pre-trained ResNet34 network through transfer learning to learn time–frequency features and perform classification. The experimental results show that the accuracy rate of the recognition of the whole signals has reached 94% at a low signal-to-noise ratio of 0 dB, and demonstrate that they have already overcome the issue of degraded recognition performance in traditional methods under low signal-to-noise ratios and complex modulation signals, particularly frequency-hopping signals. Daying Quan et al. [60] employed the CWD transform to convert low probability of intercept (LPI) radar signals into two-dimensional time–frequency images. An asymmetric dual-channel convolutional neural network was used to extract the images’ low-level HOG contour features and deep CNN semantic features. These features were then fused via a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) and fed into a Softmax classifier, enabling recognition of 12 LPI radar signals. Results demonstrated an overall recognition rate of 97% at −6 dB, exhibiting excellent robustness.

Shuai Chen et al. [61] proposed the ACSF-TMAE generative self-supervised learning framework to address signal modulation recognition in partially missing scenarios. It utilises PWVD to capture the instantaneous frequency characteristics of non-stationary signals, employs MIM to extract high-level spectral features masked by noise from strong/weakly enhanced samples, and leverages the AC-SF module to automatically focus on regions with concentrated time–frequency energy, significantly enhancing recognition robustness under few-shot conditions.

Due to its ability to analyse signals simultaneously in both the time and frequency domains, the time–frequency spectrum has gained widespread application in the modulation recognition of non-stationary signals. It is particularly well suited for the intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals, which is also the approach currently adopted by most researchers. However, this method relies on the quality and quantity of the time–frequency spectrum of frequency-hopping signals. Consequently, it is difficult to achieve effective application in specific scenarios such as battlefield communications where data samples are scarce. Furthermore, the time–frequency spectrum has limitations in distinguishing between certain modulation types, resulting in current research being confined to only a few specific modulation types. This makes it challenging to effectively extend the method to a broader range of modulation types.

4.2. Intelligent Modulation Recognition of Frequency-Hopping Signals Using Common Neural Network Models

Deep learning encompasses numerous outstanding neural networks, each demonstrating optimal adaptability in application scenarios. The following section will detail the application of intelligent modulation recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals across several neural network architectures.

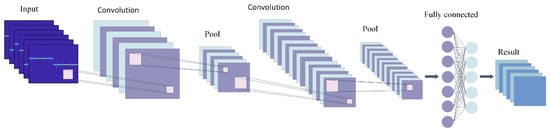

(1) Convolutional Neural Network

Convolutional neural network (CNN) represents one of the most widely applied and successful architectures today. They exhibit exceptional performance in analysing and processing data across two or more dimensions. For intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals, their outstanding capability in handling two-dimensional data makes them the preferred architecture for analysing the time–frequency spectrum of such signals. Therefore, CNN-based intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals fundamentally falls under the category of time–frequency analysis-based recognition. The fundamental structure of CNNs bears a striking resemblance to that of MLPs. However, unlike MLPs, CNNs represent a distinct category of neural networks designed explicitly for spatial data. Their use of local connections and weight sharing reduces model complexity and minimises the risk of overfitting. Structurally, CNNs combine multiple convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers to analyse input data layer by layer, continuously updating weight parameters to achieve optimal classification results. Specifically, the convolutional layer primarily extracts data features; the pooling layer further compresses these extracted features to enhance computational efficiency; and the fully connected layer integrates the extracted local features into global feature parameters to complete classification. The basic architecture of CNN is shown in Figure 14:

Figure 14.

Basic structure of CNN.

Li Hongguang et al. [62] combined the advantages of STFT and WVD to propose a frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition method based on a combined time–frequency transformation. They converted the frequency-hopping signal identification problem into an image recognition problem by extracting and classifying the time–frequency image with a CNN, overcoming the difficulties of the inadequate capabilities of the traditional manual feature extraction, limited applicability to specific modulation types, and degraded performance under low signal-to-noise ratios. At a low signal-to-noise ratio of −4 dB, this method achieved an average recognition rate of 92.54% for eight modulation schemes, including BPSK and QPSK, demonstrating excellent robustness.

Bo Qian et al. [63] obtained the time–frequency distribution map of frequency-hopping signals via the Short-Time Fourier Transform. They employed the Fast Non-Local Mean (FNLM) algorithm to enhance features for noise reduction, greyscaling, and image compression. Subsequently, they designed a five-layer convolutional neural network (including a global pooling layer) for classification, addressing the issue of low classification accuracy for frequency-hopping signals under low signal-to-noise ratios. However, the model requires an excessive number of parameters and involves substantial computational demands, making its practical application quite challenging. Liu Cong et al. [64] obtained the time–frequency image of the signal through the wavelet transform. Subsequently, they input the time–frequency image into a convolutional neural network for classification and recognition. This approach effectively resolved the problem that traditional frequency-hopping signal classification methods based on signal feature extraction are highly susceptible to SINR and cannot achieve effective classification and recognition under low SINR conditions. However, this method only classifies the broad category of frequency-hopping signals alongside other fixed-frequency signals, without investigating the modulation characteristics of frequency-hopping signals themselves.

Lü Guopei et al. [65] extracted two-dimensional time–frequency spectrum contour features from frequency-hopping signals obtained via STFT. They then constructed three-dimensional matrix contour plots for input into a convolutional neural network for training and testing, thereby achieving classification and recognition.

Beyond time–frequency analysis-based intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals, researchers have also applied CNNs to parameter estimation-based intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals. To achieve recognition, CNNs are employed to extract features from individual frequency-hopping cycles of the signal. Li Mingdi et al. [66] proposed an intelligent recognition technique based on multidimensional feature fusion and deep convolutional networks for feature extraction. This method extracts dual spectra, constellation diagrams, and Hilbert–Huang transform (HHT) time–frequency spectra for feature fusion. Compared to traditional intelligent recognition methods for frequency-hopping signals, this approach requires lower computational complexity while improving recognition accuracy across various signal-to-noise ratios.

(2) Residual Neural Network

Residual neural networks (ResNet) is a special architecture of CNN. Typically, as network depth increases, recognition performance improves. However, once network depth reaches a certain threshold, performance declines—primarily caused by the vanishing gradient problem. Therefore, addressing the vanishing gradient issue is essential while deepening the network. ResNet mitigates the vanishing or exploding gradient problem in deep neural networks by introducing unique residual modules, while maintaining strong generalisation capabilities.

Yongjiang Mao et al. [67] combined adaptive filtering and morphological processing to enhance and denoise the time–frequency images of radar signals extracted via the complex Morlet wavelet transform (CMWT). They designed a channel-separated residual network (Sep-ResNet) to classify the enhanced time–frequency images. However, this method exhibits high computational complexity and may confuse signals with similar time–frequency features under low signal-to-noise ratios, limiting its application scenarios. Li Bin et al. [68] proposed an algorithm (DRN-UAV) utilising residual neural networks for identifying and monitoring UAV remote control signals’ time–frequency spectra. This approach performs preprocessing operations such as binarisation and interference removal on the time–frequency spectrum to construct the target spectrum. A large dataset comprising actual test spectra from various UAV remote control signals was used to train and test the residual neural network, ultimately achieving intelligent identification of frequency-hopping signals.

MingDi Li et al. [69] improved existing RFF extraction methods by integrating deep learning recognition techniques based on deep residual networks (ResNet), achieving effective feature fusion. Ultimately, they accomplished frequency-hopping signal classification and recognition on ResNet.

(3) Image Convolutional Neural Network

Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) are a variant of CNNs to some extent. They process graph data by leveraging structural information within the data, extracting node information through weighted averages of adjacency matrices and feature vectors. GCNs treat each frequency-hopping cycle as a node in the intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals. They construct an adjacency matrix using the correlations between the mixed features of each signal at each frequency point as the edges, which serves as the input to the GCN.

Frequency-hopping signals consist of multiple short-duration segments across carrier frequencies, exhibiting transient fluctuations in the time domain and discrete spectral components in the frequency domain. Simultaneously, successive hopping cycles typically differ only in carrier frequency, maintaining a degree of correlation that suggests inherent temporal interdependencies within the signal. Traditional research predominantly employs CNNs to analyse and train the time–frequency spectrogram of frequency-hopping signals. However, during this process, CNNs primarily extract spatial or temporal neighborhood features within local regions of the time–frequency spectrogram using fixed convolutional kernels, making it challenging to effectively model global relationships between different frequency-hopping segments. In contrast, GCNs explicitly model relationships between frequency-hopping segments through graph structures. By performing convolution operations on adjacency matrices and feature matrices to aggregate neighboring node features, they progressively obtain representations of individual nodes and the entire graph. This mechanism effectively captures global dependencies across time and frequency, enabling GCNs to capture the global correlation features of frequency-hopping signals more effectively than traditional CNN approaches.

For example, in the GCN-based frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition method, Shi et al. [70] proposed a novel GCN-based method for identifying frequency-hopping signal modulation. The authors segmented the frequency-hopping signal into multiple time segments (hopping segments) based on the carrier frequency-hopping pattern. They extracted hybrid features for each segment and calculated the Spearman rank correlation coefficient between node features. Edges in the adjacency matrix (AM) were constructed using these coefficients. Finally, a GCN was designed to extract signal features further and complete the modulation identification. Experimental results demonstrate that this method achieves an 81.8% recognition rate even at a signal-to-noise ratio of −10 dB. Compared to mainstream time–frequency transformation methods, this represents a significant performance improvement. Building upon this foundation, Zhang Jing et al. [71] proposed a frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition method integrating multimodal deep learning. The authors utilised both CNN and GCN neural network models to extract time–frequency and topological map features from frequency-hopping signals for fusion. Support vector machines were then employed for modulation recognition of the frequency-hopping signals. The feasibility of this approach was validated on a dataset comprising six frequency-hopping modulation signals: 2ASK, 2FSK, 4ASK, 4FSK, BPSK, and 64QAM.

(4) Other neural networks

In addition to the commonly used neural networks mentioned above, researchers have also applied numerous other neural networks to the intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals, such as deep neural networks (DNNs), YOLO, and Swin Transformers. This section will introduce the applications of these neural networks in the intelligent modulation recognition of frequency-hopping signals.

Due to CNNs’ superior performance in image recognition, many researchers have developed new models based on them. In 2015, Joseph Redmon, Ali Farhadi, and others pioneered a single-neural-network-based object detection system named YOLO. This neural network demonstrated outstanding performance in image recognition, leading to its extensive application in feature extraction from the time–frequency spectrum of frequency-hopping signals. Zhou Kai et al. [72] obtained time–frequency spectra by applying Gabor features to signals for time–frequency transformation, then trained and classified these spectra using an improved YoloV5 model. Jing Chen et al. [73] transformed the modulation detection and recognition problem of frequency-hopping signals into an image object detection classification task, employing available deep learning algorithms like YoloV3 to detect and recognise time–frequency spectra obtained via STFT. Zhang Haibin et al. [74] addressed the issue of interference signals severely degrading the detection and recognition performance of frequency-hopping signals in complex electromagnetic environments. They constructed a dataset featuring combined “frequency-hopping signal + interference signal” patterns. By employing a deep separable convolution module to extract background information near the signal’s time–frequency spectrum, they utilised a gated aggregation mechanism to weight and aggregate background information with signal features. This composite feature set was then processed through an improved YoloV5s model for recognition. Additionally, some researchers have developed advanced Swin Transformer models for object detection and recognition tasks. Zhao Mingyu et al. [75] pioneered the application of the Transformer algorithm in modulation recognition, employing the window attention and sliding window attention mechanisms of the Swin Transformer to capture local features and cross-window correlations in time–frequency images, thereby significantly improving recognition accuracy. Zhanxiong Li et al. [76] addressed the challenges of insufficient feature extraction in traditional CNN models and scattered attention in Transformers for frequency-hopping signals. By introducing a sliding window attention mechanism to process the time–frequency images of frequency-hopping signals, and adding Fast-NLM denoising and variable attention mechanisms tailored to the characteristics of frequency-hopping signals, they successfully achieved modulation recognition for frequency-hopping signals.

Deep neural networks are among the earliest applied deep learning models, demonstrating formidable feature learning and extraction capabilities when processing data and making decisions under unsupervised conditions. Yi Qu et al. [77] addressed the issue of manually adjusting sorting thresholds for traditional frequency-hopping signals by proposing Faster-RCNN and clustering algorithms. This method first utilises Faster-RCNN to identify and locate all frequency-hopping points of the time–frequency spectrum. Subsequently, they achieved the classification recognition of the frequency-hopping signal by AlexNet, which obtained the number of the frequency-hopping signal. In contrast, Jusung Kang et al. [78] converted the fingerprints that were extracted from frequency-hopping signals into time–frequency characteristics of fingerprints that were characterised by a spectrogram, and then utilised them to train a classifier based on a deep initial network, ultimately achieving classification and recognition.

When the single-hop period contains few code elements, slicing the frequency-hopping signal according to the hopping period fails to extract practical features due to insufficient code information. As shown in Equation (2), a frequency-hopping signal is essentially a secondary modulated signal of an already modulated signal using MFSK modulation. Once the frequency set and hopping points of the frequency-hopping signal are extracted through parameter estimation, de-hopping processing can be applied to convert the frequency-hopping signal into a conventional fixed-frequency signal for processing. W. Xie et al. [79] proposed a novel frequency-hopping modulation recognition method to address issues such as strong carrier frequency offset sensitivity and insufficient timing error resistance in traditional recognition approaches under complex environments. This method first extracts the frequency set and hopping points through parameter estimation to perform de-hopping processing on the signal; then, it calculates the High-Order Cyclostationarity (HOC) to analyse its statistical characteristics deeply; finally, it employs a well-trained neural network classifier to achieve accurate recognition of multiple modulation formats, including BPSK, QPSK, 8PSK, and 16QAM. As shown in Table 4, this study lists recent deep learning applications for modulation recognition in frequency-hopping signals.

Table 4.

Deep learning-based frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition.

5. Frequency-Hopping Signal Parameter Estimation

Introduction

As discussed in Section 3, the frequency-hopping signal modulation recognition method based on parameter estimation is highly dependent on the accuracy of parameter estimation. Therefore, this section will introduce the current state of research on frequency-hopping signal parameter estimation.

Current frequency-hopping signal parameter estimation algorithms are primarily categorised into two types: time–frequency analysis methods and non-time–frequency analysis methods.

Non-time–frequency analysis methods include compressed sensing (CS) and sparse Bayesian learning (SBL). Although these methods demonstrate potential in sparse feature extraction and modelling, they generally suffer from high computational complexity and strong dependence on hardware resources, making it challenging to meet the real-time requirements of high-speed communication systems. L. Zhao et al. [80] employed a hierarchical Bayesian modelling approach within the sparse Bayesian learning framework to introduce spectral sparsity and incorporate time-aware clustering constraints for parameter estimation of frequency-hopping signals. However, this method suffers from excessive computational demands and extreme dependence on frequency grid models, rendering it unsuitable for dynamic and complex scenarios. Wang, F et al. [81] combined maximum likelihood (ML) theory and compressed sensing (CS) to estimate the frequency-hopping points and frequency sets of frequency-hopping signals, respectively. However, this method is prone to confusion when processing multi-hop signals and struggles to handle complex, dynamic communication scenarios, thus retaining certain practical limitations.

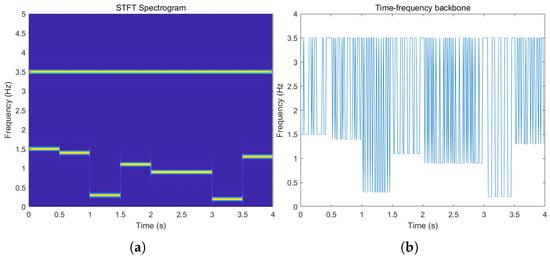

Since parameter estimation for frequency-hopping signals primarily targets frequency sets and hopping points, time–frequency analysis methods—which simultaneously capture both time-domain and frequency-domain information—are more widely applied in this field. These methods demonstrate outstanding performance when processing time-varying signals, making them difficult to replace with alternative approaches. They primarily fall into two categories: parameter estimation based on the time–frequency backbone (TF-B) and coordinate localisation based on the time–frequency spectrogram.

Let the time–frequency energy spectrum matrix of the frequency-hopping signal be denoted as . By partitioning this matrix according to its time-domain sampling points, we obtain

Among these, is the time–frequency matrix slice corresponding to the i-th sampling point, expressed as

By traversing each slice along the frequency axis, the maximum frequency index corresponding to the strongest energy at each sampling point can be obtained, i.e.,

In the spectrum of a pure frequency-hopping signal, represents the energy concentration point of the signal. By arranging in the order of sampling points, the time–frequency ridge line can be obtained.

However, as shown in Figure 15, when the frequency-hopping signal is mixed with the fixed-frequency signal, the presence of the fixed-frequency signal causes significant interference at the energy concentration points in the time–frequency spectrum. Therefore, researchers have been dedicated to eliminating the interference from the fixed-frequency signal.

Figure 15.

Time–frequency plot of fixed-frequency signal mixed with frequency-hopping signal and corresponding time–frequency ridge. (a) Frequency-hopping mixed signal time–frequency plot; (b) time–frequency ridge for frequency-hopping mixed signals.

Zhang Shengkui et al. [82] proposed an improved blind estimation algorithm for frequency-hopping parameters to address the issue of fixed-frequency signals interfering with the extraction of time–frequency ridges in mixed frequency-hopping and fixed-frequency signals. This algorithm utilises k-means clustering to separate and eliminate fixed-frequency interference based on differences in signal residence time, thereby extracting pure time–frequency ridges. Subsequently, the Haar wavelet transform is applied to detect frequency-hopping singularities along the ridge, enabling estimation of the hopping period, start time, and frequency. Zuo Xinhui et al. [83] employed time–frequency energy cancellation techniques to eliminate fixed-frequency interference signals. They separated the interference by analysing row-wise difference features of the frequency-hopping signal in the time–frequency matrix. Subsequently, they used genetic algorithm (GA) optimisation to adaptively determine the optimal segmentation threshold for image segmentation, employing image entropy as the fitness function to enhance target-background discrimination. Finally, they estimated the hopping rate and frequency set parameters through connected component labelling and cluster analysis. Liu Lianzhao et al. [84] employed morphological filtering and time–frequency spectrum cancellation techniques to filter out sweep, fixed-frequency, and pulse interference signals while preserving the time–frequency characteristics of frequency-hopping signals through structural element design. Finally, they extracted parameters such as hopping sequences and hopping rates from the purified time–frequency map using the peak sequence method. Simulations demonstrated that this method effectively suppresses composite interference and achieves high-precision parameter estimation at 0 dB signal-to-noise ratio. Building upon this, Wan et al. [85] integrated energy cancellation techniques with the OTSU algorithm adaptive thresholding to remove fixed-frequency signals and their residual interference. They then employed least-squares fitting to extract hopping points from the clarified time–frequency ridges, achieving high-precision estimation of hopping period, start time, and frequency.