Abstract

The reliable and early detection of promising research directions is of great practical importance, especially in cases of limited resources. It enables researchers, funding experts, and science authorities to focus their efforts effectively. Although citation analysis has been commonly considered the primary tool to detect directions for a long time, it lacks responsiveness, as it requires time for citations to emerge. In this paper, we propose a conceptual framework that detects new research directions with a contextual Top2Vec model, collects and analyzes reviews for those directions via Transformer-based classifiers, ranks them, and generates short summaries for the highest-scoring ones with a BART model. Averaging review scores for a whole topic helps mitigate the review bias problem. Experiments on past ICLR open reviews show that the highly ranked directions detected are significantly better cited; additionally, in most cases, they exhibit better publication dynamics.

1. Introduction

Researchers use terms “promising research directions”, “research front”, and “frontier” as synonyms to define the latest and most advanced knowledge and research directions in a field, and they mark the forefront of scientific and technological development [1]. Identifying the directions is essential for guiding scientific progress and allocating resources effectively. A common way to reveal promising research directions is to quantitatively analyze recent citation and publication trends with modern text mining and statistical tools in large research paper and patent databases [2]. Although this approach is very objective and free from expert bias, it has several disadvantages.

- Scientometric analysis relies on accurate, manually curated international citation databases, which can be costly to maintain and use. However, these databases often fail to capture local trends and needs. For instance, research in region-specific agriculture may hold significant practical value, yet these related papers are frequently not indexed or well-cited in international databases.

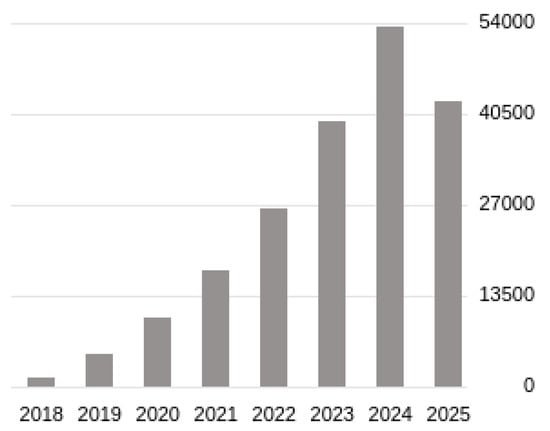

- There is a substantial gap between publishing the first innovative results and presenting the first robust signals of a new frontier in citation databases. For example, the preprint of the Vaswani et al. “Attention is all you need” paper [3] was published first in June 2017 (Figure 1), but even in 2018, citation databases could not reliably detect this new frontier (because all citation information for 2018 was available only in 2019).

Figure 1. Citation dynamic for Vaswani et al. “Attention is all you need” paper [3] in Google Scholar (screenshot).

Figure 1. Citation dynamic for Vaswani et al. “Attention is all you need” paper [3] in Google Scholar (screenshot).

We tackle these problems by collecting and analyzing open reviews. The main contributions of this paper are the following.

- We have proposed and tested an end-to-end conceptual framework that combines several ideas in review-based ranking and text mining: use topic-level assessment to tackle reviewing bias [4], apply pre-trained classifiers to extract relevant fragments from the reviews, and employ the classifiers to obtain unified review scores [5]; therefore, scores from different sources can be considered together. This framework builds and detects novel research directions on preprint databases with Contextual Top2Vec [6], summarizes them with a Transformer-based sequence-to-sequence model, and automatically ranks them based on the related open reviews with a Transformer-based encoder model. This integrated framework enables the early identification and ranking of novel research directions without relying on citation databases, reducing bias and accelerating discovery.

- We have validated this end-to-end framework through experiments on retrospective data from the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2017–2019) [4] and arXiv.org (2017–2021) [7]. Results show that high-ranked research directions identified by our method achieve significantly better citation performance than others.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the detection of research directions, topic modeling, and summarization. Section 3 describes the proposed framework and the method we use to summarize the directions. Section 4 briefly discusses the dataset we utilized in the experiments. Section 5 presents the results of the experiments on the ICLR datasets. Finally, Section 6 and Section 7 provide a discussion and conclusion regarding the results obtained.

2. Related Work

2.1. Detection of Promising Research Directions

Most research in promising research direction detection reveals outbursts in publication or citation activity, or the growing usage of particular keywords, and considers related papers as frontiers. For example, paper [8] utilizes the high-ranked conference papers provided by Google Scholar Metrics. They first investigate the annual publication dynamics in a particular area, and then they use the paper’s keywords to detect the promising directions. They study frequency, betweenness centrality, clustering of keywords, and detect rapidly growing keywords. Ye G. and colleagues highlight the problem that the utilization of paper or patent databases as the initial data to reveal frontiers may lead to outdated results [9]. They propose an adapted method that uses research grant data to identify research front topics and forecast trends. First, they apply a topic model to detect research directions, and then relate them to funded projects and cross-domain categories. Finally, they study the evolution of the obtained directions to predict development trends. Although experiments show that the method is effective in research direction identification, many research funds still do not publish project reviews and do not provide references to related papers. Quantitative publication activity analysis is also a frequently used technique to detect promising directions in particular areas. For example, paper [10] uses Top2Vec to build topics from arXiv.org and analyze their dynamics. Another way to tackle the gap when using the databases is to create predictive models. Paper [11] proposes a global graph ranking model that utilizes node embedding. They propose a cost function that solves the ranking problem with a probabilistic regression. The proposed model has been tested on an arXiv paper citation network using standard information retrieval-based metrics. The results show that the proposed model outperforms, on average, other state-of-the-art static models as well as dynamic node ranking models.

We rely on review scores to identify promising directions. The natural question that arises, though, is whether there is any reliable relationship between the review score and novelty and demand of the reviewed work [4]. Paper [12] studies relationships between novelty and the acceptance of manuscripts submitted to scientific journals. They use the unusualness of reference combinations in their citation lists as a measure of novelty and conventionality. Experiments show that both novelty and conventionality are related to acceptance. They also show that papers with novel results are cited better. Paper [13] concludes that peer review in journals with higher impact factors tends to be more thorough. Similarly, paper [14] uses data from the National Institutes of Health fund to study how peer reviews can predict the future quality of proposed research. They show that higher peer-review scores are associated with better research citations. Wang and colleagues [4] apply the Ward clustering algorithm to obtain journal submission clusters. They show that the clusters with higher review scores are cited better. It is worth noting that they could not detect a similar pattern for individual papers, because many rejected papers may be accepted later at other conferences or journals and gain many citations. Paper [15] proposed an approach to predict a paper’s citations. The approach utilizes a heterogeneous publication network of nodes, including papers, authors, venues, and terms. Then, it applies a graph neural network to jointly embed all types of nodes and links to model the paper’s impact. The experiments confirm that the proposed method overcomes others in citation prediction with publication networks.

Despite the recent rise in open-review resources, obtaining labeled corpora for different tasks remains a problem [16]. Study [17] describes the review score prediction and the paper decision prediction on two datasets with ICLR submissions; a similar dataset is also proposed in the paper [18]. Paper [5] proposes the PEERAssist framework to predict review scores. This framework outperforms similar approaches, which utilize sentiment analysis. Ribeiro and colleagues propose a dataset to perform review sentiment analysis and investigate polarities [19]. The CiteTracked [20] dataset combines reviews from the NeurIPS conference with the paper’s citations, which helps study paper citations based on the reviews. Paper [21] introduces the Open Review-Based dataset that includes a list of more than 36 K papers, and more than 89 K reviews, together with decisions gathered from OpenReview.net and SciPost.org. However, in this work, we still rely on a smaller ICLR dataset from [4] because it also provides citation information about reviewed papers.

2.2. Topical Vector Models

Many recent studies in topic modeling are devoted to marrying topic models and dense word/sentence embeddings. The Embedded Topic Model [22] is one of the first approaches that combine a probabilistic topic model with word embeddings. This approach uses word embeddings to represent lexis in a document to tackle the drawbacks of the bag-of-words models. However, it still ignores the syntax of words and requires the number of topics to be determined. The paper [23] proposes Top2Vec that utilizes joint document and word embeddings to find topic vectors. Top2Vec combines syntactic features from document embeddings with the semantic ones from word embeddings. It also automatically estimates the number of topics. The BERTopic approach [24] utilizes contextual token-level embeddings from BERT [25], which combine syntax and semantic features out of the box. However, this approach does not assign topics to all documents, and it only sets one topic for a document. Paper [6] extends the Top2Vec approach with contextual document embeddings from SentenceBERT. They show that the approach outperforms others on a set of topic model evaluation metrics and supports hierarchical topic reduction. Therefore, we shall use ContextualTop2Vec in our experiments.

2.3. Topic Summarization

A common approach in text summarization is to use text-to-text Transformer models like T5 [26] or BART [27]. For example, paper [28] uses T5 trained on the UCI drug reviews dataset. Similarly, paper [29] studies Transformer-based models for summarization, with a focus on BART. They evaluate the variants of BART with the BERTScore [30]. They also claim that BART’s encoder captures richer contextual relationships, which makes it well-suited for abstractive summarization. In contrast, T5 follows a standard text-to-text approach, which simplifies adaptation to multiple tasks but complicates training for summarization. These differences in the models allow one to pick between processing speed, memory consumption, and summary quality. There are also open pre-trained models for scientific text summarization, for example, T5 trained on arXiv.org [31].

Topic summarization brings additional questions on how to extract and combine information-rich and topic-related fragments from the topic’s papers. Onan et al. [32] propose the FuzzyTP-BERT framework for extractive text summarization. It combines Fuzzy Topic Modeling with BERT. FuzzyTP-BERT integrates fuzzy logic to refine topic modeling, enhancing the semantic sensitivity of summaries by allowing a more nuanced representation of word–topic relationships. Paper [33] proposes a topic summarization framework that is compatible with various Transformers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Framework

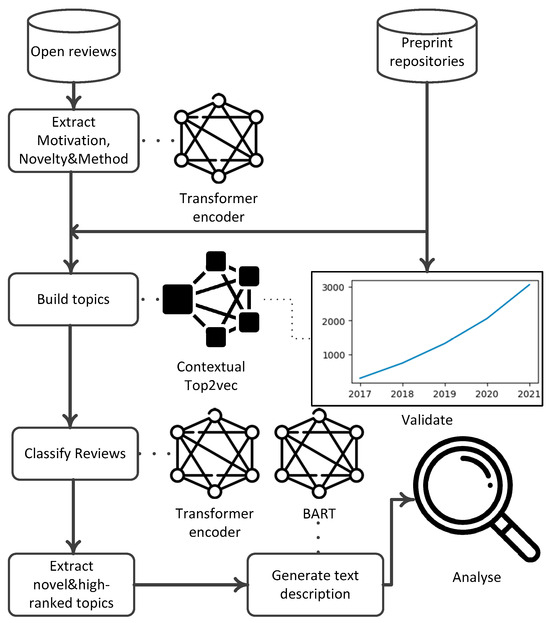

Figure 2 shows the general schema of our framework. First, it collects open reviews from high-ranked conferences (CORE A/A* [34]) and open research journals from a particular research field for a given year y (in this research, we limited ourselves to ICLR reviews only). It collects the full texts of relevant research papers from preprint repositories as well. Second, it extracts the fragments from the reviews, which are potentially related to the prospects of the analyzed piece of research, neglecting other parts related to the quality of submission text, number of experiments, etc. Namely, it extracts the fragments related to motivation, novelty of work, and the description of the proposed method/approach. We tackle the fragment extraction problem as a sequence labeling task and solve it at the sentence level with a Transformer-based encoder model (xlm-roberta [35]). Further, we shall refer to this subtask as “Review segmentation”.

Figure 2.

Schema of the approach to detect and describe novel research directions based on open reviews. Solid arrows depict data flows, and dotted lines link the approach steps to the utilized models.

Third, it uses the collected preprint full texts and a contextual Top2Vec model to build topics (research directions). We use SentenceBERT’s all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model as the encoder to generate phrase and document embeddings for the Top2Vec because it works fast on CPU, keeping competitive performance.

Fourth, it detects novel research directions. Top2Vec cannot provide probability estimations for the topic terms; therefore, straightforward approaches to compare topics, like Kullback–Leibler divergence, cannot be applied. We decided to neglect topic term weights and to use Spearman’s correlation between term ranks. Thus, a research direction is considered to be novel if its ranked term list has a negative correlation with the previous year’s topics’ ranked term lists, and this correlation is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05).

Fifth, it applies another Transformer-based encoder to predict the reviewer’s score of the papers in the novel research directions. We refer to this subtask as “Review classification”. We utilize a simple ternary classification setting, which distinguishes the “accept” overall score from “borderline” and “decline”. The motivation here is two-fold:

- –

- We cannot rely on the explicit score given by the reviewer, because different conferences, journals, and research funds use different scoring systems.

- –

- This rough (“accept”/”borderline”/”decline”) scoring leads to lower classification error; in addition, combining these scores for a whole topic would provide more versatile information anyway.

In addition to the pure text of reviews, we tested a couple of heuristic features to gain classification scores. The first one is whether a review has more than one question. Too many questions in a review might be a sign that a reviewer perceives the submission skeptically. The second one is whether the reviewer explicitly declares that the submission results are novel (we shall further refer to this subtask as “Review classification”). We trained and applied an additional Transformer-based classifier to detect such reviews and split them from those in which “novelty” words are not related to the results.

Finally, we utilize a lightweight text generation model to build descriptions for the novel high-rated research directions (we shall refer to this subtask as “Topic summarization”). In short, the description approach has the following steps: 1. Extract top-n documents that mostly relate to the direction. 2. Extract sentences that contain the directions’ terms from the documents. 3. Use the generative model (BART) to form a fluent, coherent description of this set of sentences. Section 3.3 describes these steps in more detail.

In this research, we have also applied the following additional validation steps to be sure the extracted topics actually reflect the perspective research directions.

1. Check on retrospective data if there is more significant paper publication growth for the high-ranked research directions than for the low-ranked ones. The motivation behind this is that writing publications requires organizational and financial efforts that are unlikely to be spent on dead-end projects. We use the following score to estimate the growth (Equation (1)).

where is a number of the direction’s publications at starting year y, and is number of the direction’s publications at year y + i.

2. Check on retrospective data if there are more citations for the high-ranked directions than for the low-ranked ones.

All the sources implementing those steps are openly available in the COntext TOp2vec Frontiers (COTOF) repository [36].

3.2. Phrase Generation for the Contextual Top2Vec

Contextual Top2Vec uses standard statistical approaches to build topic phrases. Namely, they use pointwise mutual information (PMI) [37] to detect word collocations in texts and utilize them to build the model’s dictionary. However, this approach may not perform well on small texts like reviews or submission abstracts. In this study, we tested several alternatives to this approach to tackle this.

In the first approach, we use a linguistic parser [38] to explicitly extract syntactically related word pairs. The second approach is to consider internal attention from the encoder model used in the Contextual Top2Vec. In this approach, we just find word pairs with high absolute attention values (see Equation (2)).

where N is the number of layers in the encoder, H is the number of heads in the encoder, is the attention weights between words i and j in the layer layer and the head head. In our experiments, we have empirically derived the following rule: we leave the word pairs if their AttnRelScore is higher than the mean AttnRelScore for all the pairs in the text. An advantage of this approach is that it does not need any third-party tool to extract phrases.

In all the approaches, we filter out non-frequent pairs, which appear less than four times in the text corpus.

3.3. Research Direction Summarization

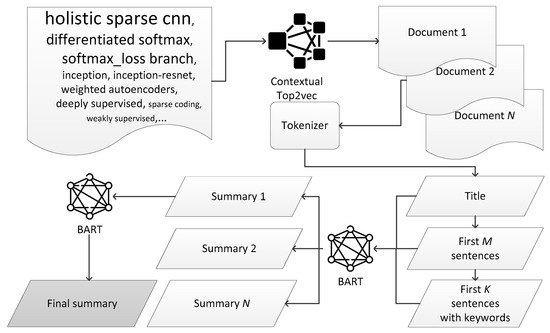

Our framework uses a two-stage summarization procedure that allows us to use small generative models with limited context size (Figure 3). In the first stage, we summarize each direction’s paper independently, and then we summarize all the paper summarizations. Namely, the procedure includes the following steps.

- Get the most relevant direction’s documents with the Contextual Top2vec model. In our experiments, we obtained the 10 most relevant papers for each direction.

- From each document’s text extract title, select the first M = 5 sentences (they are likely to be from the document’s abstract), and top K = 5 (as they follow in the paper’s text) sentences containing top keywords or key phrases from the topic.

- Use the extracted sentences as a prompt and summarize each paper with an LLM.

- Concatenate all the paper summarizations and use it as a prompt to summarize the whole direction.

Figure 3.

Schema of the research direction summarization.

4. Datasets

We have picked the ICLR dataset from [4] as the primary one for three reasons. First, preprints of the most reviewed papers from this dataset are openly available on arXiv.org. Second, the provided reviews are pretty historical, covering conferences from 2017 to 2019; therefore, there is room to track the detected frontiers on retrospective data. Third, it contains Google Scholar citations of the reviewed papers, which are essential to check the success of the detected directions. We also collected all the arXiv.org preprints from 2017 to 2021 via the provided open API (778.5 K preprints) to track publication dynamics GR for the directions. The major limitation of the ICLR dataset is that it contains data from a single scientific area. Although our methods do not use any area-specific dictionaries or thesauri, the results still might differ for other fields of research. In the future, we shall extend the datasets with examples from various scientific areas to tackle this problem.

In this study, we also created a tiny dataset (82 samples) for the “Novelty detection” task [39]. It provides sentences from various reviews; half of them claim that the overall reviewed research results are new, and other half just contain a novelty-related lexis (“new”, “novel”, etc.), which is not related to the submission results. This dataset is used to generate an additional feature (IS NEW) for review scoring.

We have also tested several techniques to build phrases for Top2Vec. Two commonly used datasets have been utilized to perform this task: 20 news groups (20NG) and Yahoo, which were highlighted as the most suitable ones in paper [6]. We were also curious how the techniques would help in datasets with short texts. To this end, we utilized a part of the ICLR dataset, containing only review texts from ICLR 2017, which are considerably shorter than the texts from 20NG or Yahoo.

Finally, we have created another dataset for scientific text summarization [40]. The dataset provides about 1K snippets of research papers for 99 search queries with their short summaries of the snippets for each query generated with ChatGPT-4o mini. After the generation, we manually filtered out all the samples that seemed to contain hallucinations.

5. Experiment Results

First, we tested the techniques for building phrases for the Contextual Top2Vec. In our experiments, we use standard hyperparameters for the Top2Vec: embedding size 384 (as all-MiniLM-L6-v2 provides), UMAP’s number of neighbors 50, UMAP reduction to 5, and Hdbscan’s min_cluster_size 15. We use standard coherence scores and tools to obtain them [41] but estimate them separately at the phrase and word levels. Table 1 shows that all the approaches show very close performance in terms of topic coherence. Phrasal-based scores seem to be stricter than the word-based ones in almost all cases. The syntax-based approach is slightly better on the ICLR dataset. This result can be related to shorter texts in this corpus compared to others. The attention-based approach achieves better CBERTScore in all the datasets.

Table 1.

Topic coherence scores for different approaches to build phrases.

The next section of the experiments is devoted to testing Transformer-based models for various text classification subtasks. We utilized the Huggingface Transformers library to perform the experiments. For all the subtasks, we applied similar training hyperparameters: learning rate 2 × 10−5, batch size 8, weight_decay 0.01, and warmup_ratio 0.15. We used standard optimizers and losses provided by Transformer’s Trainer for the sequence classification class. We repeated all the classification experiments three times with different random seeds and train/test splits and obtained mean scores with their standard deviations.

We started with the review segmentation classifiers. These sentence-level models filter out all review fragments that are not directly related to the novelty, motivation, or technical details of the analyzed research. According to Table 2, xlm-roberta shows the best results for this task; therefore, we selected this model for further experiments. The dataset we used for this experiment contains non-open-access reviews. Thus, we keep it private and provide access to the best model [42].

Table 2.

Classification metrics for the ‘’Review segmentation”.

For the novelty detection, we use the distilbert-base-uncased model (see Table 3), which is one of the smallest models. It achieves the second-best result with a reasonable standard deviation, since the size of the dataset for this task is small. The relatively high standard deviation in the classification scores indicates that this dataset is too small to support robust training; therefore, it should be extended in the future.

Table 3.

Classification metrics for the ‘’Novelty detection”.

Finally, we have tested the models to classify reviews into three classes (reject, borderline, accept). Table 4 shows the obtained scores. The “TEXT” column provides results for the case where we classify a pure review of text fragments. In the “TEXT + QUESTION TAG” case, we added a special tag word if there is more than one question in the review. Column “TEXT + QUESTION TAG + IS NEW” provides results for the case when we also add another special tag if the novelty classifier concludes that the research is novel. According to Table 4, the roberta-base model shows the best results in the case “TEXT + QUESTION TAG”. This means that the novelty classifier does not provide helpful information for the task, but the question tags do.

Table 4.

Classification metrics for the “Review classification”.

After the high-ranked research directions are revealed, we then build short text annotations for them. For this task, we have tested several models with full-Transformer (T5 and BART) and decoder-only (GPT-based) architectures. Although the mistralai/Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 shows the best scores on this task, the much smaller and faster BART-based model philschmid/bart-large-cnn-samsum obtains results which are nearly as good, so we choose it for the following experiments (Table 5). We used the same strict hyperparameters for all the generative models: temperature 0.2, top_p 0.3, top_k 3, repetition_penalty 1.5 to reduce hallucinations.

Table 5.

Metrics for the topic summarization.

We also limit input text (left context size) to 2048 tokens, document-level annotations to 64 tokens, and overall annotations to 300 tokens; therefore, even models with small context windows, such as T5, can operate with these settings.

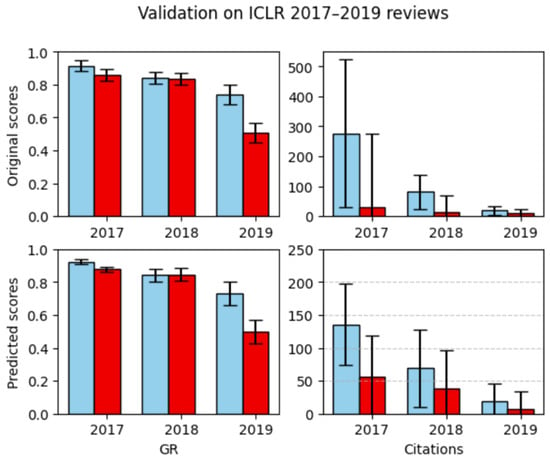

We have validated our framework on the open reviews from ICLR 2017–2019. Specifically, we detected the 10 best- and 10 worst-ranked research directions, and then we used retrospective arXiv.org data and citation information to compare these two groups. We collected related preprints for each direction with the same SentenceBERT model (all-MiniLM-L6-v2) as used in the Contextual Top2Vec, estimating cosine similarity between topic and preprint vectors. We selected a strict similarity threshold of 0.6 to ensure that the preprints were very close to the topics. After obtaining the topic’s GR scores for the 2017–2021 interval and their Google Scholar citations for 2021 (Figure 4), we estimated Mann–Whitney statistics for the best- and worst-ranked topics.

Figure 4.

GR and citation number (mean and standard deviations) for the top- (blue) and low-ranked (red) directions in ICLR2017–2019. The top row shows results for the original reviewers’ scores, and the bottom row presents results for predicted scores.

Table 6 shows the obtained results for two cases: (1) we use the original reviewer’s scores to neglect potential review classification errors when we rank topics, and (2) we use the predicted classification results to rank topics. According to Table 6, there is no qualitative difference between predicted and original review scores, i.e., our classifier is suitable for the promising direction detection task. Citation scores for the best-ranked direction are statistically higher than those of the worst-ranked ones in all cases.

Table 6.

Mann–Whitney U statistics and p-values to show contrast between top- and low-ranked directions in GR and average citation number.

Regarding the GR score, the same results are obtained for two of the three conferences. We believe that this is because of a limitation of the GR score, which is insensitive to the research direction size (i.e., it produces the same score for growth from 1 paper to 10 as for growth from 100 papers to 1000).

6. Discussion

The experiment results show that the proposed framework can detect promising research directions based on open peer reviews. Our results support previous theoretical [43] and experimental findings [4], showing that diversifying peers by adding independent concurrent panels (which we simulate by averaging review scores for a whole direction) leads to an improvement in the reproducibility of analysis. Automatic peer-review score assignment makes it possible to apply the framework to any conference or journal regardless of their internal scoring system. Of course, the ICLR dataset is helpful only to illustrate the framework’s idea, because it is narrow-focused and (despite the high rank of the conference) may still be biased. In order to make a working framework, we need to collect and combine all the reviews from different sources. Moreover, since there is a very limited number of high-ranked venues, we need to test less-ranked conferences and journals to check if our findings hold for them. Another problem is that we use arXiv.org as the single source of preprints to build topics. However, it is a limited source in terms of research area variety and number of preprints; therefore, we need to broaden the list of preprints and open-access paper databases.

We also found that although the applied cumulative growth ratio (GR) score can be estimated without any citation database, it may not be the best option to validate the success of a direction because it is insensitive to the direction’s size. In the future, we will test other publication activity-based scores, which would also consider the size of the topic.

7. Conclusions

The proposed conceptual framework uses open reviews to detect novel research directions, rank them, and describe them. This framework mitigates the time gap between the appearance of new promising directions and their detection; in addition, it does not need any additional citation databases. The cornerstone of the framework is the contextual Top2Vec model, which we preferred over others, since it automatically adjusts the number of topics, supports phrases to describe the topics, and builds topics’ centroids in the document’s vector space, which makes it possible to track the revealed research directions on open research paper databases. The framework generates review scores based on the review texts and averages the scores for the whole topic, which helps tackle reviewing bias. The statistical analysis on the retrospective data from ICLR 2017–2019 conferences has shown that the detected high-ranked directions outperform the low-ranked ones in citations. The high-ranked topics also achieved up to twice the citation growth as the low-ranked ones.

In the future, we shall broaden the list of considered open reviews by adding alphaXiv, PCI Peer Community, SciPost.org, openly available reviews from research journals, and funds. This would further smooth out the reviewing bias and make the ranks more balanced from different points of view. We will also keep testing our framework at other conferences to strengthen the statistical results obtained. Ultimately, the proposed framework would enable scientific authorities, funding agencies, and research institutions to create analytical tools for planning or adjusting their activity structures, thereby ensuring that promising directions receive sufficient organizational and budgetary support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D. and O.G.; methodology, I.V.S.; software, A.R., D.P. and F.A.; validation, I.V.S., D.Z. and O.G.; investigation, D.D.; resources, D.Z.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.; writing—review and editing, D.D.; supervision, O.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, project No. 075-15-2024-544.

Data Availability Statement

The original data and sources presented in the study are openly available in Github: https://github.com/masterdoors/COTOF (accessed on 21 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Du, S.; Sanmugam, M. A Bibliometric Review of Studies on the Application of Augmented Reality to Cultural Heritage by Using Biblioshiny and CiteSpace. In Embracing Cutting-Edge Technology in Modern Educational Settings; Chee, K.N., Sanmugam, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 184–213. [Google Scholar]

- Park, I.; Yoon, B. Identifying Promising Research Frontiers of Pattern Recognition through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 30th Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 7–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. What have we learned from OpenReview? World Wide Web 2023, 26, 683–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.B.; Ranjan, S.; Ghosal, T.; Agrawal, M.; Ekbal, A. PEERAssist: Leveraging on paper-review interactions to predict peer review decisions. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference Towards Open and Trustworthy Digital Societies, Virtual Event, 1–3 December 2021; pp. 421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Angelov, D.; Inkpen, D. Topic modeling: Contextual token embeddings are all you need. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 13528–13539. [Google Scholar]

- ArXiv.org. Open-Access Archive. Available online: https://arxiv.org (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Pan, J. Identification of data mining research frontier based on conference papers. Int. J. Crowd Sci. 2021, 5, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Wang, C.; Wu, C.; Peng, Z.; Wei, J.; Song, X.; Tan, Q.; Wu, L. Research frontier detection and analysis based on research grants information: A case study on health informatics in the US. J. Informetr. 2023, 17, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrekht, V.; Mukhamediev, R.I.; Popova, Y.; Muhamedijeva, E.; Botaibekov, A. Top2Vec Topic Modeling to Analyze the Dynamics of Publication Activity Related to Environmental Monitoring Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Publications 2025, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Hasan, M.K.; Abbasi, A.; Mokhtar, U.A.; Khan, A.; Abdullah, S.N.H.S.; Ahmed, F.R.A. Predicting the future popularity of academic publications using deep learning by considering it as temporal citation networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83052–83068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplitskiy, M.; Peng, H.; Blasco, A.; Lakhani, K.R. Is novel research worth doing? Evidence from peer review at 49 journals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118046119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severin, A.; Strinzel, M.; Egger, M.; Barros, T.; Sokolov, A.; Mouatt, J.V.; Müller, S. Relationship between journal impact factor and the thoroughness and helpfulness of peer reviews. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielle, L.; Agha, L. Big names or big ideas: Do peer-review panels select the best science proposals? Science 2015, 348, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Han, J. Revisiting citation prediction with cluster-aware text-enhanced heterogeneous graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE 2023), Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–7 April 2023; pp. 682–695. [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger, M.; Kusa, W.; Piroi, F.; Hanbury, A. An analysis of tasks and datasets in peer reviewing. In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Scholarly Document Processing (SDP 2024), Bangkok, Thailand, 16 August 2024; pp. 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.L.; Vaz-de Melo, P.O.S. Enhancing the examination of obstacles in an automated peer review system. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2023, 25, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Ammar, W.; Dalvi, B.; Van Zuylen, M.; Kohlmeier, S.; Hovy, E.; Schwartz, R. A dataset of peer reviews (PeerRead): Collection, insights and NLP applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; pp. 1647–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.C.; Sizo, A.; Cardoso, H.L.; Reis, L.P. Acceptance decision prediction in peer review through sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 20th EPIA Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 7–9 September 2021; pp. 766–777. [Google Scholar]

- Plank, B.; Van Dalen, R. CiteTracked: A Longitudinal Dataset of Peer Reviews and Citations. In Proceedings of the Joint Workshop on Bibliometric-Enhanced Information Retrieval and Natural Language Processing for Digital Libraries (ACM BIRNDL SIGIR), Paris, France, 25 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Szumega, J.; Bougueroua, L.; Gkotse, B.; Jouvelot, P.; Ravotti, F. The open review-based (ORB) dataset: Towards automatic assessment of scientific papers and experiment proposals in high-energy physics. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.04576. [Google Scholar]

- Dieng, A.B.; Ruiz, F.J.; Blei, D.M. Topic modeling in embedding spaces. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, D. Top2vec: Distributed representations of topics. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2008.09470. [Google Scholar]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 7871–7880. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, J.; Abuka, G. Text Summarization using Transformer Model. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), Milan, Italy, 29 November–1 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premnath, P.; Yenumulapalli, V.O.; Mohankumar, P.; Sivanaiah, R. TechSSN at SemEval-2025 Task 10: A Comparative Analysis of Transformer Models for Dominant Narrative-Based News Summarization. In Proceedings of the 19th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2025), Vienna, Austria, 31 July–1 August 2025; pp. 2205–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, 26 April–1 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gilhuly, C.; Shahzad, H. Consistency Evaluation of News Article Summaries Generated by Large (and Small) Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.20647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onan, A.; Alhumyani, H.A. FuzzyTP-BERT: Enhancing extractive text summarization with fuzzy topic modeling and transformer networks. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Tian, L.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M. Friendly topic assistant for transformer based abstractive summarization. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 485–497. [Google Scholar]

- ICORE Conference Portal. Available online: https://portal.core.edu.au/conf-ranks (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 8440–8451. [Google Scholar]

- COntext TOp2Vec Frontiers. Available online: https://github.com/masterdoors/COTOF/tree/main (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Bouma, G. Normalized (pointwise) mutual information in collocation extraction. In Proceedings of the Biennial GSCL Conference; Gunter Narr Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2009; Volume 30, pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- ISA-NLP Linguistic Parser. Available online: https://github.com/IINemo/isanlp (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Novel or Not Dataset. Available online: https://github.com/masterdoors/COTOF/blob/main/notebooks/new_or_not_eng.ipynb (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Summarization Dataset. Available online: https://github.com/masterdoors/COTOF/tree/main/datasets/summarization (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- OCTIS. Available online: https://github.com/MIND-Lab/OCTIS (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Review Segmentation Model. Available online: https://huggingface.co/Ryzhik22/rev-classif-twolangs (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Kirman, C.R.; Simon, T.W.; Hays, S.M. Science peer review for the 21st century: Assessing scientific consensus for decision-making while managing conflict of interests, reviewer and process bias. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 103, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).