Abstract

Driving safety education remains a critical societal priority, and understanding traffic rules is essential for reducing road accidents and improving driver awareness. This study presents the development and evaluation of a virtual simulator for learning traffic rules, incorporating spherical video technology and interactive training scenarios. The primary objective was to enhance the accessibility and effectiveness of traffic rule education by utilizing modern virtual reality approaches without the need for specialized equipment. A key research component is using Petri net-based models to study the simulator’s dynamic states, enabling the analysis and optimization of system behavior. The developed simulator employs large language models for the automated generation of educational content and test questions, supporting personalized learning experiences. Additionally, a model for determining the camera rotation angle was proposed, ensuring a realistic and immersive presentation of training scenarios within the simulator. The system’s cloud-based, modular software architecture and cross-platform algorithms ensure flexibility, scalability, and compatibility across devices. The simulator allows users to practice traffic rules in realistic road environments with the aid of spherical videos and receive immediate feedback through contextual prompts. The developed system stands out from existing traffic rule learning platforms by combining spherical video technology, large language model-based content generation, and cloud architecture to create a more interactive, adaptive, and realistic learning experience. The experimental results confirm the simulator’s high efficiency in improving users’ knowledge of traffic rules and practical decision-making skills.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the use of virtual and augmented reality technologies in education and various other domains has grown significantly [,,]. Integrating these tools into the learning process creates an engaging and flexible environment that captures students’ attention and motivates them to explore new knowledge. At the same time, this method enables learning without the need for specialized equipment or materials, thus increasing accessibility. Such accessibility helps educational institutions optimize resource utilization and minimize expenses related to organizing the educational process.

This study demonstrates how spherical video technology can be effectively integrated into a virtual simulator to enhance the learning of traffic rules without requiring specialized equipment. It examines the role of large language models in automating the generation of educational and testing materials, ensuring adaptability and personalization of the learning process. The research also explores the application of Petri net-based modeling to analyze and optimize user interactions and simulator dynamics. Additionally, the study evaluates how cloud-based modular architecture enhances the scalability, accessibility, and flexibility of the proposed learning platform.

The article demonstrates the effectiveness of using spherical video technology [,] in teaching traffic regulations and developing driving skills, highlighting its advantages over conventional driving instruction methods. Additionally, it describes the implementation of a virtual training simulator designed for studying traffic regulations and enhancing vehicle operation skills. A spherical video streaming learning model was developed to master traffic rules. The outcomes of this study are highly relevant to improving road safety and shaping effective driving education programs. The findings confirm that the proposed model operates as intended and successfully enhances the process of acquiring driving skills.

In the contemporary world, cutting-edge technologies are increasingly being applied in education. Specifically, video materials have become one of the most widespread and effective means of knowledge transmission []. Videos can teach a virtually unlimited range of topics, from history to mathematics. They assist students in comprehending complex concepts and terminologies, demonstrate real-life examples, and render the learning experience more engaging and comprehensible. One of the key advantages of utilizing video content is its accessibility at any time and from any location. This flexibility allows students to view videos at their own pace and at a convenient time. Moreover, videos can be revisited multiple times, enabling students to review the material until they fully grasp it. Video content is also beneficial for teaching practical skills; for example, videos can instruct students on cooking, sewing, or repairing items by demonstrating step-by-step procedures and outlining the necessary tools and materials. Additionally, video content can facilitate the organization of remote courses, helping students acquire essential knowledge and skills, regardless of their geographical location. A significant advantage of using video content is its interactivity. Videos can incorporate visual effects, animations, audio, and other elements to create engaging and captivating lessons. Furthermore, video materials can include quizzes and surveys, allowing instructors to assess students’ understanding of the material. While two-dimensional videos are valuable educational tools, they can have limitations that reduce their effectiveness for specific subjects. While video materials may help teach foundational concepts, they may not provide sufficient information for students to understand more complex topics fully. Moreover, traditional two-dimensional videos often lack interactive elements, such as the ability to ask questions or engage with the material, which could diminish their effectiveness as teaching tools for specific subjects [].

The solution to overcome these limitations is to propose the implementation of spherical videos within the educational process to create a virtual reality learning environment. Additionally, it is essential to develop an interactive overlay on the video stream that integrates virtual prompts and questions, allowing users to engage with these virtual elements. This approach aims to enhance the learning experience by promoting active participation and facilitating a more effective comprehension of the material.

Spherical videos, also known as 360-degree videos, provide the opportunity to create an immersive learning environment, allowing for complete or partial immersion in a virtual world or various forms of mixed reality, where students can explore, observe, and study concepts in a more detailed and realistic format. In spherical videos, users can move and look in any direction, making them feel at the center of the action. This level of engagement promotes more profound understanding and retention of information, making it an effective pedagogical tool in the educational process.

One of the critical themes that requires practical and realistic material transmission is the process of learning traffic rules. Knowledge of these regulations is essential for the safe and efficient use of vehicles and for ensuring road safety. Spherical videos can serve as an effective medium for imparting educational content related to traffic rules and facilitating driving skill development. The primary advantage of using spherical videos to instruct traffic rules is creating a realistic and immersive learning environment. Students can experience and explore various road situations more authentically and in detail. Another benefit of employing spherical videos is the capacity for dynamic learning. Students can navigate and investigate different road scenarios in real time, which aids in understanding how to respond appropriately to various situations and apply traffic rules effectively while driving a vehicle. Additionally, spherical videos can be instrumental in teaching fundamental concepts and terminologies associated with traffic regulations. For example, video materials can illustrate how to execute maneuvers correctly, explain the meanings of different traffic signs and markings, and demonstrate how to react to traffic signals and sign combinations. This engaging format enhances comprehension and equips students with the essential skills for safe driving.

An additional advantage of using spherical videos is their accessibility. They can be easily downloaded via the internet and played on various devices, such as computers, smartphones, and tablets, making them convenient for use in schools and driving courses. Another benefit of spherical videos lies in the potential for personalized learning, allowing students to explore different road scenarios at their own pace and at times convenient for them. This flexibility enhances the learning experience and accommodates diverse learning styles and schedules, further promoting effective skill acquisition in traffic regulation and driving.

The article’s structure includes five sections. The first section introduces the motivation and context for developing a virtual simulator for traffic rule training, emphasizing how spherical video and virtual reality technologies can make driving education more engaging, accessible, and cost-effective while improving learners’ understanding and practical application of traffic regulations. The second section outlines the algorithm for the system’s functionality and models based on Petri net theory, which facilitates the investigation of the operational dynamics of the proposed program. The third section contains information about the developed structure of the designed system, which is based on a modular organization, as well as the software architecture, which is cross-platform. Additionally, this section presents the developed model for camera rotation angles and the structural diagram of the cloud architecture of the virtual simulator. The fourth section discusses the specifics of user interface design. Finally, the conclusions summarize the studies’ key scientific and practical results.

2. Background

Recent research on the use of spherical videos in teaching traffic regulations and developing driving skills has drawn increasing attention []. Several studies have shown that spherical videos offer learners a more immersive educational experience, improving understanding and retention of knowledge [,]. This technique also enables the simulation of real-life driving situations in a safe and controlled setting, supporting skill development. However, some researchers point out technical limitations related to spherical video, such as the need for specialized equipment and high-resolution cameras, which can raise the overall training costs. In addition, the lack of standardized guidelines and best practices for integrating spherical videos into driver education may influence the overall effectiveness of such programs [,,]. Overall, while the potential benefits of spherical videos in traffic education are promising, addressing these challenges is essential for maximizing its effectiveness and accessibility in driving instruction.

Based on the key findings from the analyzed studies, it can be concluded that the methods of augmented and virtual reality, as well as their application within the educational process, are positively received by the public. Most individuals express confidence in this new approach to information acquisition and provide positive feedback regarding the high effectiveness of using augmented and virtual reality in education []. However, the reviewed research also reflects the challenges associated with integrating augmented and virtual reality methods into the educational framework, particularly due to a lack of knowledge in this area among the teaching staff of educational institutions [,]. Many educators are unfamiliar with the concept of spherical videos or any popular augmented and virtual reality techniques, and they often lack the necessary technical skills to develop instructional materials that incorporate these technologies or to include them effectively in the learning process. Addressing these gaps in knowledge and skills is crucial for maximizing the potential of augmented and virtual reality in education, thereby enhancing the learning experience and outcome for students.

Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies have seen rapidly growing adoption in education and training over the past few years [,,]. These immersive tools can create engaging, realistic learning environments, and studies report that learners generally respond positively to VR/AR-based instruction, finding it more interesting and motivating than traditional methods []. In driver education specifically, spherical 360-degree video has gained particular attention as an accessible form of VR for teaching traffic rules []. Recent research indicates that 360° video content provides a more immersive and memorable learning experience than standard 2D videos [,]. Trainees can virtually explore real-life road scenarios from a first-person perspective, which helps them better retain information and practice decision-making skills in a safe setting []. This approach effectively simulates real-life driving situations (intersections, road hazards, weather conditions, etc.) in a controlled environment, thereby building practical knowledge and reflexes without putting learners at physical risk [].

However, implementing spherical video-based training at scale comes with certain challenges. High-quality 360° video production requires specialized cameras and significant data streaming capacity, which can raise the cost and complexity of the learning setup []. There is also a lack of standardized pedagogical guidelines on how to integrate 360° videos into driver training curricula []. Many driving instructors are not yet trained in using VR/AR tools and may be unfamiliar with designing effective interactive content for them [,]. Without sufficient support and best practices, the effectiveness of these technologies can vary widely. In fact, while most learners enjoy VR/AR learning, a persistent barrier is the limited technical expertise among some educators to confidently employ these methods [,]. In prior surveys, instructors have reported uncertainty about the pedagogical use of spherical videos or AR enhancements in their classes and noted difficulties in operating the equipment []. This gap in educator readiness underscores the need for professional development and clear implementation frameworks—successful adoption of VR in teaching will require training teachers in the necessary technical and instructional competencies [,]. Addressing these issues of cost, equipment, and teacher preparedness is crucial for maximizing the benefits of immersive learning experiences in driver education.

Notwithstanding these challenges, a growing body of recent literature demonstrates the strong educational potential of VR and AR when they are applied thoughtfully. Meta-analyses of immersive learning initiatives have generally found positive effects on learner outcomes. For example, VR-based training often outperforms traditional training in terms of knowledge acquisition and retention. A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis on safety training showed that VR training led to significantly higher knowledge gains and longer information retention than conventional methods []. In the context of teacher education, a recent meta-analysis reported a moderate overall improvement in teaching skills for VR-supported instruction compared to control groups, highlighting VR’s effectiveness across domains []. In traffic safety and driver training, experimental studies have found that fully immersive scenarios can boost learner engagement and understanding. One study comparing device types reported that a headset-based VR lesson on traffic rules was more effective than a standard mobile app, resulting in greater learner interest and less confusion for both novice and experienced drivers [].

AR solutions have likewise shown benefits in training simulations. A 2024 meta-review of AR-based safety training found that augmented reality interventions produced a significant positive impact on learners’ safety behavior and outcomes []. However, that review also noted that in some cases AR training achieved knowledge test scores comparable to those of traditional training, rather than dramatically higher []. This suggests AR’s main advantages may lie in engagement and practical skill transfer more than in short-term factual recall. Overall, these findings across domains illustrate that—when implemented under the right conditions—VR and AR can substantially enhance the effectiveness of skills training and make learning more engaging. The evidence is increasingly supportive that immersive simulations help learners practice desired behaviors (whether classroom management or safe driving) in ways that translate to better real-world performance [,,].

In parallel with the rise in VR/AR, researchers have begun integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into driving simulators to create smarter, more adaptive training platforms. AI-based driving simulators leverage techniques like machine vision, natural language processing, and user modeling to provide real-time feedback and personalized instruction to learners. A recent survey of driver training simulation technologies observes that AI enhancements—such as intelligent tutoring systems and adaptive scenario generation—are increasingly used to improve training effectiveness []. For example, researchers developed a low-cost simulator for driver’s education that incorporates a generative AI assistant to coach the user during practice scenarios []. In their system, the AI monitored the driver’s actions and delivered pre-generated corrective feedback messages (via a speech or text interface) whenever the learner made an error. This approach yielded promising results, as trainees guided by the AI assistant reported better understanding of their mistakes and felt more engaged in the simulator-based lessons [].

Another research introduced a “virtual driving instructor” system powered by AI that can evaluate a learner’s performance and provide feedback on par with human instructors []. In controlled trials, the AI-driven instructor was able to assess driving maneuvers (such as lane changes and braking response) with accuracy comparable to expert driving teachers, and provide neutral, consistent feedback in real time []. These developments align with broader trends in educational technology, where AI is used to personalize learning. Within driving simulators, AI-driven modules can dynamically adjust the difficulty of scenarios, focus training on a student’s weak areas, and present an almost unlimited range of traffic situations (including rare or dangerous scenarios that cannot be easily practiced on real roads) [,]. Early studies suggest that learners benefit from this tailored, data-driven approach—for instance, an AI tutor can instantly point out a missed mirror check or rolling stop, allowing the student to correct habits on the fly. Overall, the incorporation of AI into vehicle simulators appears to enhance the training experience by making it more interactive and individualized. It is an area of active research, and preliminary results are encouraging, though further evaluation is needed as these intelligent systems become more sophisticated.

Another cutting-edge technological development influencing modern educational systems is the advent of large language models (LLMs). LLMs such as OpenAI’s GPT-3 and GPT-4 are advanced AI models trained on vast text datasets, enabling them to generate human-like responses and to perform a variety of language and reasoning tasks. In recent years, researchers have begun to explore the use of LLMs as educational tools [,]. One major application is in automating the generation of learning content. LLMs can be prompted to create quiz questions, explanations, summaries, and other instructional materials on virtually any topic []. For example, an LLM can instantly produce a set of traffic-rule questions based on a given driving scenario, along with detailed explanations of the correct answers. This capability is highly relevant to our traffic rule training platform, which leverages an LLM to generate contextual questions and answers tied to the 360° video scenes. By doing so, the system supports on-demand content creation and regular updates (e.g., if regulations change, the LLM can generate new questions reflecting the updated rules).

Recent studies in the education field have demonstrated several potential benefits of integrating LLMs. This studies discuss that LLM-powered tools can personalize learning by adapting to each student’s inputs—for instance, by rephrasing explanations until the student understands, or by providing hints tailored to the student’s current knowledge level []. Other work has shown LLMs can serve as conversational tutors or chatbots that help students through problem-solving steps, which can improve engagement and interactivity in online learning environments []. Early empirical evidence on LLM-assisted learning is beginning to emerge. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies found that incorporating ChatGPT-5 into educational activities produced modest but significant improvements in students’ academic performance and higher-order thinking skills []. Students using ChatGPT-based support also reported lower cognitive load and frustration, indicating that the AI assistance made learning more efficient in some cases [,,].

In domain-specific contexts, LLMs are being tested as well—for example, in medical training, LLMs have been used to simulate virtual patients for students to diagnose or to generate clinical scenarios, and researchers note that the models have potential to enhance clinical decision-making exercises for trainees []. Despite these advantages, the literature also emphasizes important challenges and ethical considerations when using LLMs in education. One concern is the accuracy and correctness of the content generated by an LLM [,]. Without careful oversight, an LLM might produce explanations that sound plausible but contain errors or “hallucinated” facts. Bias is another issue: LLM outputs can reflect biases present in their training data, which could lead to problematic or unbalanced content in an educational setting [,]. There are also questions regarding academic integrity (for instance, ensuring students use LLM assistance as a learning tool rather than for cheating) and the need to teach students critical thinking when interacting with AI-generated information [,]. Researchers have proposed frameworks to address these issues—such as guidelines for teachers on how to integrate AI chatbots responsibly, and strategies like verifying LLM answers against trusted sources [,].

Overall, the consensus in recent studies is that LLMs, if used judiciously, can be powerful aids in education, automating routine tasks and providing scalable personalized support [,]. In developed traffic rule training platform, the inclusion of an LLM component exemplifies this emerging synergy: the model automatically generates relevant questions for each traffic scenario and even adapts explanations from the official rulebook into learner-friendly language. This illustrates how LLMs can enhance traditional e-learning systems by making them more responsive and tailored to individual learners’ needs—in our case, giving each user a virtual “tutor” that accompanies the immersive driving simulation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview of the Virtual Simulator

The use of a virtual simulator for learning traffic rules provides several key benefits during the early stages of training compared to conventional methods that involve driving real vehicles. It allows learners to experience realistic traffic situations through spherical videos while maintaining complete safety, as no physical road participation is required. The combination of video playback and detailed explanations of different road scenarios enables students to practice and develop their skills in conditions that closely mirror real-world experiences. This immersive experience can reduce the frequency of mistakes that may occur during actual driving, often driven by anxiety associated with the responsibilities of operating a vehicle in real conditions. The virtual simulator helps learners build confidence and competence before transitioning to practical driving experiences by providing a secure learning environment. Moreover, the feedback mechanisms integrated within the simulator can enhance learning by helping students identify and rectify errors in their understanding and application of traffic rules. As a result, the virtual simulator proves to be a valuable tool in preparing novice drivers for safe and responsible driving practices.

3.2. Structure of Traffic Scenarios and Learning Process

Examples of traffic scenarios incorporated into the developed virtual simulator for learning traffic rules include making turns at intersections, exiting parking areas, stopping on the roadway, approaching railway crossings, passing through intersections on a green light, and safely navigating pedestrian crossings. These scenarios are critical for teaching essential driving skills, as they enable students to practice managing various driving conditions and understand the corresponding rules and regulations. By simulating these situations, learners can develop their decision-making abilities, enhance their situational awareness, and cultivate safe driving habits in a controlled, risk-free environment. This comprehensive approach to traffic education ensures students are better prepared for real-world driving challenges.

3.3. Interactive Learning Mechanism and Contextual Prompts

To improve the effectiveness of the learning process, virtual elements in the form of contextual prompts have been integrated into specific points within the spherical video. These prompts provide relevant information about the traffic rules associated with the situations shown in the footage. When a prompt appears, the video playback automatically pauses, allowing learners sufficient time to study the information and achieve a clearer understanding of the scenario. The video stream resumes after a predetermined period allocated for processing the situation. This overlay mechanism is also utilized in the simulator’s testing mode, where questions and potential actions related to the depicted traffic scenario are displayed at specific moments during video playback. During the display of a question, the video stream is paused, allowing users to read the question and select an answer using either the computer keyboard or controllers connected to the virtual reality headset. The correct answer is highlighted upon the user’s selection, and the video playback continues. At the end of the video playback, users are presented with a results table summarizing their scores on the test. This interactive approach reinforces learning and enables users to actively engage with the material actively, thereby improving retention and understanding of traffic rules and driving skills.

3.4. Algorithmic Framework and Petri Net Modeling

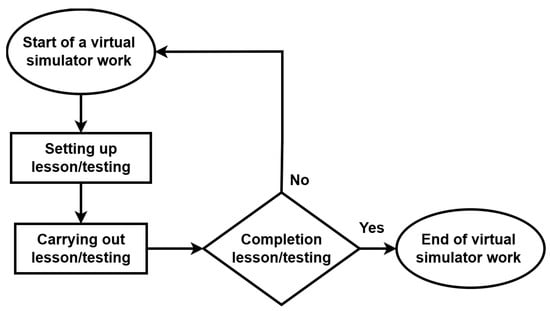

The developed algorithms for the operation of the virtual simulator aimed at acquiring driving skills and learning traffic rules are illustrated in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The workflow of the virtual simulator begins with system initialization and configuration of lesson or testing parameters, followed by the execution of the selected learning or test session. Upon completion, a conditional check determines whether additional lessons or tests are required; if not, the simulator concludes its operation and terminates the session.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the Operation of the Virtual Simulator for Acquiring Driving Skills and Learning Traffic Rules.

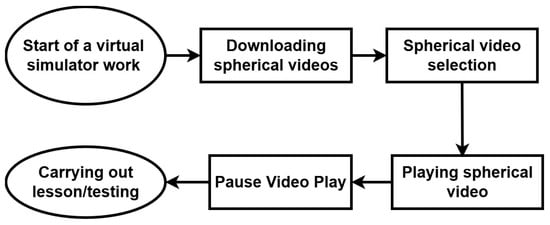

Figure 2.

Algorithm for Configuring Lesson Conduct and Testing.

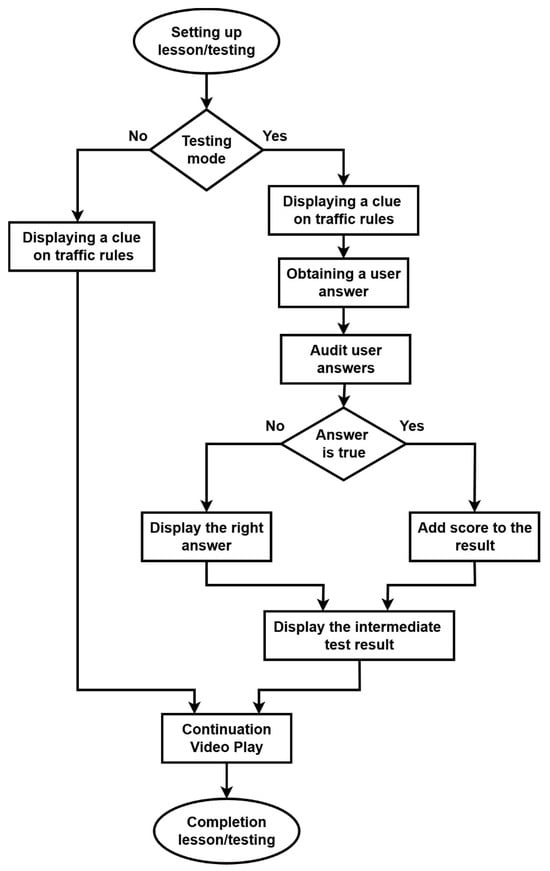

Figure 3.

Algorithm for Conducting Lessons and Testing.

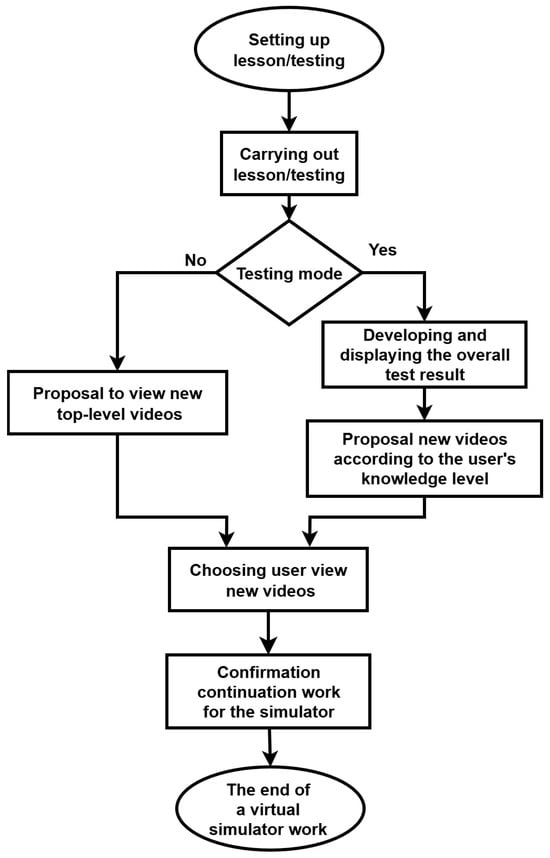

Figure 4.

Algorithm for continuous learning workflow.

Once a lesson is chosen, it is running within the training environment, with automatic pauses at predefined moments to deliver instructional content or initiate testing tasks as part of the interactive learning process.

When the simulator switches to the lesson or testing phase, it determines whether the current mode is for instruction or assessment. In testing mode, the system displays a clue on traffic rules, collects and evaluates the user’s answer, shows the correct response along with the intermediate results, and then resumes video playback until the lesson or testing session is completed.

After completing the lesson or testing session, the simulator analyzes the user’s results and proposes new spherical videos that match their knowledge level or suggests advanced content for further improvement. The user then selects the next videos to view, confirms the continuation of the simulator’s operation, and the workflow concludes when the training cycle is finished.

In the developed virtual training simulator for learning traffic rules using spherical video display, hierarchical Petri nets [,] have been implemented to model user behavior, specifically their actions and reactions to various traffic situations.

To model the operational states of the virtual simulator, models have been developed using Petri net theory: a high-level Petri net for modeling the logic of the simulator and the user’s interaction with the virtual simulator interface, as well as a nested Petri net for modeling user actions during the lesson. This nested model includes states corresponding to user decisions and actions in specific traffic situations. For example, the user may perform actions such as stopping the vehicle or changing the direction of movement when faced with a complex traffic scenario.

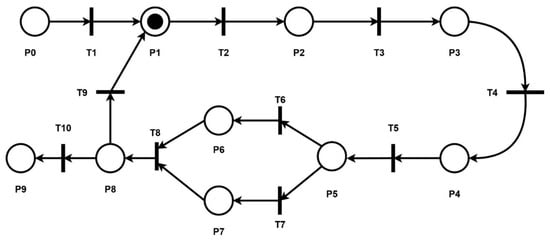

The schematic form of the high-level Petri net model for simulating the logic of the simulator and user interaction with the interface is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

High-Level Petri Net for Modeling the Logic of the Simulator and User Interaction with the Interface Petri Net states that models the logic of the simulator and user interactions with the.

Table 1 illustrates the logical progression of the simulator’s states, where the flow moves sequentially through user engagement, scenario observation, decision formulation, and system evaluation.

Table 1.

Table of the Petri Net States Modeling the Logic of the Simulator and User Interaction with the Interface.

The process begins with the user entering the simulator environment and progresses through phases of interaction, where each transition represents an event that advances the simulations such as moving from passive observation to active decision-making or from executing an action to receiving system feedback. Depending on the outcome, the flow diverges into either a corrective path or a continuation toward new scenarios, ultimately concluding when the learning session ends. This structure ensures that the simulator maintains a continuous learning loop in which user actions directly influence subsequent events and feedback cycles.

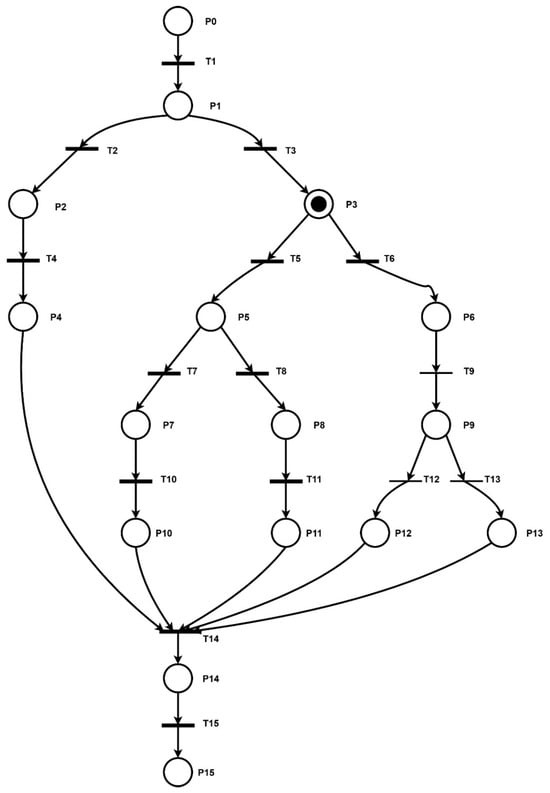

The nested Petri net model, which simulates user actions during the lesson, reflects the state of “Decision making” of the high-level Petri net. This nested Petri net is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Petri Net Modeling User Actions During the Lesson.

The sequence begins with the visualization of a traffic event and progresses through user evaluation and selection of potential maneuvers such as braking, steering, or overtaking. Each action leads to a new state, reflecting how users adapt their behavior based on real-time system cues and rule-based reasoning. The flow concludes when all possible actions have been executed or evaluated, signaling the end of the traffic scenario and preparing the system to return control to the higher-level simulator logic for the next sequence. Petri Net states that model the logic of the simulator and user actions during the lesson are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Table of the Petri Net States Modeling User Actions During the Lesson.

3.5. Automated Generation of Educational Content Using LLMs

Implementing an effective virtual simulator for learning and assessing knowledge of traffic rules is an exceptionally complex task that requires careful preparation of educational content and test tasks. This stage requires a thorough analysis of relevant regulatory acts, particularly the Traffic Rules, which are regularly updated [,]. The educational materials must cover all aspects of traffic rules, including traffic signs, road markings, maneuvering, intersection passing rules, stopping and parking, and behavior in special conditions. In addition to theoretical content, it is essential to incorporate various illustrations, animations, and interactive elements that simplify the comprehension of complex information.

Developing test tasks requires accurate phrasing and thoughtful consideration of answer options to avoid ambiguities. The tasks should be structured into thematic blocks corresponding to different difficulty levels. Creating a large question bank that comprehensively covers all topics is necessary to ensure a practical knowledge assessment. Additionally, avoiding the templated nature of questions is essential, which can lead to mechanical memorization of answers.

Another challenge is ensuring the materials’ relevance and alignment with the latest legislative changes. This requires ongoing collaboration with professionals in transport, law, and driving school instructors. Test tasks must undergo verification for logical consistency, accuracy, and compliance with methodological recommendations. Equally important is considering pedagogical aspects, including the sequence of material presentation, the principle of advancing from simple to complex concepts, and reinforcing knowledge through repetition.

A complete cycle of educational content preparation has been implemented within the framework of the developed virtual simulator for learning and assessing knowledge of traffic rules. This cycle includes the analysis of current regulatory acts, forming a structured knowledge base, and creating thematically grouped tests of varying difficulty levels. The content displayed in the VR environment is based on pre-recorded or simulated video episodes of traffic situations, to which relevant questions and explanations are linked. A distinctive feature of the developed system is the use of LLMs [] for the automated generation of educational and assessment materials based on video fragments. The model is employed to conduct preliminary semantic analysis of the video file content (based on their descriptions, scripts, and event time codes), identifying key elements of the situations (traffic signs, traffic lights, maneuvers, road participants, weather conditions) and forming contextual tasks in line with the video content [,].

The developed system employs a visual LLM to generate a wide range of test questions, including multiple-choice questions with single or multiple correct answers, as well as situational problems that require user analysis of actions in a simulated traffic scenario. All tasks are automatically classified by difficulty level and topic according to a classifier aligned with the driver training program. Thanks to the capabilities of the LLM, the system also generates explanations for correct answers, which are presented in the form of excerpts from traffic rules adapted for better user comprehension. Additionally, the system supports regular content updates, and in the event of legislative changes, LLM automatically forms updated versions of questions, educational blocks, and explanations.

Equation (1) presents a formalized model of the process for creating educational and assessment content within the developed system, which outlines the key stages of transforming multimodal content into structured learning tasks.

where —video fragment of a traffic situation (driving scene),

—a function for extracting key frames or scenes from the video,

—visual encoder that transforms key frames into feature vectors (recognized objects, actions, signs),

—metadata about the video (time codes, scripts, event comments),

—encoding metadata into vector representation,

—linear mapping of visual and semantic features into a space of interpretable textual tokens LLM,

—additional textual sources (parts of traffic rules, explanations, instructions),

—text encoder that transforms textual sources into vectors,

—an LLM that generates textual tasks from the obtained features,

—generated educational or assessment task (questions, answers, explanations).

The variables described represent the main stages of multimodal content processing in the virtual simulator. The interaction between the visual encoder, metadata, and textual sources enables the LLM to generate contextually relevant educational tasks. This approach ensures a high level of content adaptation to specific traffic situations and pedagogical objectives.

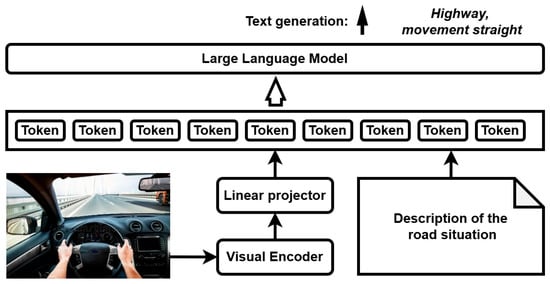

The visual language model combines visual understanding and text generation by connecting the visual encoder with the LLM. The visual encoder, typically a neural network, processes input images or video frames into vector representations of features. These visual features are vectors that capture key aspects of the visual input, such as objects, actions, and spatial relationships. A linear projector transforms these features into a space corresponding to the tokens used by the LLM, effectively translating visual information into a format understandable by it. The projected visual features are treated as special tokens and added to the input sequence of the LLM alongside regular text tokens. This enables the LLM to interpret and make logical inferences based on visual data, just as it does with textual data. During training, the visual language model learns to correlate visual patterns with their corresponding linguistic descriptions, questions, or instructions. This training allows the model to generate coherent, contextually rich textual outputs based on visual input, such as captions, explanations, or questions. While operating, the visual language model receives new images through the encoder, projects them, and generates responses that combine visual and linguistic understanding.

The workflow of the Visual Language Model is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Workflow of the Visual Language Model.

Despite the high quality of text generation, contextual understanding, and broad linguistic capabilities, publicly available LLM developed by leading companies (such as OpenAI, Google, Meta, Anthropic, etc.) [] have several limitations in the context of their use for creating educational VR systems focused on a specific regulatory domain—specifically, learning traffic rules.

One of the main issues is the relevance of knowledge in specialized domains not covered by the mass sources used during the training of LLMs. Most open models are trained on general-purpose corpora, including encyclopedias, technical documentation, news, forums, etc. However, the detailed content of national traffic regulations, local legal nuances, specific language formulations of standards, and concrete traffic situation scenarios remain outside the training corpus of such models []. Many documents are presented in formats that have not been systematically included in public corpora or have low representation in open data sources. This creates risks for generating outdated or legally inaccurate content.

Furthermore, the input formats on which trained models operate often do not align with the data structure required for the mass generation educational content. In the case of a VR simulator for learning traffic rules, the structure of the academic material must adhere to clearly defined templates. For example, there should be a linkage of test tasks to specific time codes of video episodes, thematic classification based on types of traffic situations, compliance with the current edition of traffic rules, and the inclusion of concise yet accurate explanations tailored to the user’s level. In contrast, publicly available LLMs typically work with unstructured queries and often fail to provide consistent output formatting that can be directly integrated into the system.

Another practical issue lies in the scalability of content generation for many video scenarios. Given the need for multi-level educational content—ranging from simple questions about recognizing signs to complex cases involving predicting participants’ behavior—there arises a necessity to generate hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of tasks, each of which must be unique, accurate, and structured. In this context, publicly available models that generate one question per call and lack an understanding of the global context of the system are not practical tools for large-scale automated development of the educational package.

To address these limitations, it is advisable to apply local fine-tuning of LLMs on specialized datasets that include: official texts of traffic rules in their current edition, traffic scenario scripts developed by experts, templates for formatting educational materials, and examples of typical answers, explanations, and prompt options.

To ensure the integration of educational content into the VR simulator with pre-loaded spherical video fragments, a standardized format for generating outcomes is crucial. This format enables the automatic processing, storage, and display of generated data during virtual lessons. The educational elements generated by the LLM should have a strictly defined structure that includes:

- Video Fragment ID: a unique identifier for the episode or situation.

- Timecode: the exact moment in the video to which the task is linked.

- Situation Category: for example, “roundabout intersection,” “pedestrian crossing,” “priority sign,” etc.

- Question Text: formulated clearly and concisely.

- Answer Options List: four items, with only one being correct.

- Explanation of the Correct Answer: a brief rationale based on a specific traffic rule.

- Task Difficulty: defined according to pre-established criteria (e.g., “beginner,” “intermediate,” “advanced”).

This format allows for adapting content to different levels of student preparation and the flexible construction of training sessions that align with the chosen interaction scenario with the VR simulator. To achieve the targeted format of the generated materials, a structured query system is used, which specifies:

- Context of the Learning Situation: description of the video, type of scenario, user role;

- Generation Instructions: tasks for the LLM;

- Output Format Requirements: structure in JSON, YAML, or tables;

- Example of Expected Outcome: to demonstrate the generation template.

This ensures the stability of the output format, reduces errors, and facilitates the automated verification of results. An example of a typical request to the LLM is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example of a Typical Request to the LLM.

The model receives a straightforward instructional task, a description of the situation, and a format sample, significantly reducing the likelihood of hallucinations, structural violations, or incorrect responses. By systematically applying such prompts, large tasks can be automatically generated, covering typical, critical, and rare traffic situations while considering the pedagogical objectives.

Using the “prompt-as-program” approach [], queries can include embedded logic that considers the difficulty level, type of educational goal (testing, learning, review), or the presence of hints. This enables the organization of an automated content creation process for each spherical video included in the VR simulator, ensuring complete autonomy in generating the educational package before the session begins.

Given the limitations of publicly available LLMs, which typically do not specialize in domain knowledge such as the traffic rules of a specific country [] or the specifics of visual interpretation of traffic situations, the model needs targeted fine-tuning. This approach significantly enhances the accuracy, relevance, and pedagogical correctness of the VR environment’s educational content and test tasks.

The basis of the fine-tuning process is a structured database of training examples, which contains 295 annotated situations presented in a specific format. The description of the fields in the training dataset is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structure of the Training Dataset.

The training dataset serves as a source of qualitatively annotated examples that enable the adaptation of the LLM to the specifics of visual traffic scenarios, the logic of traffic rules, and the formatting of educational content and test tasks in a consistent style.

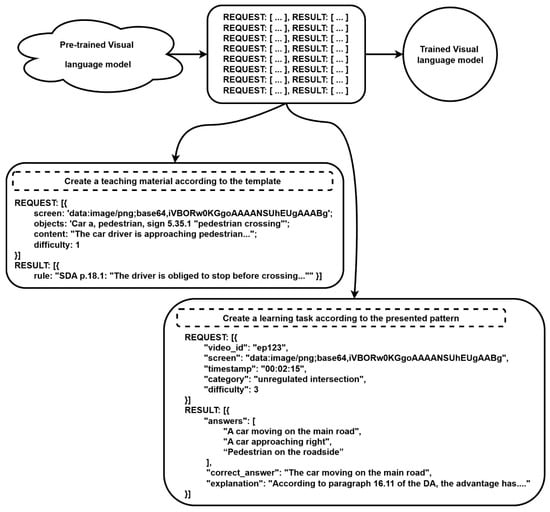

The fine-tuning scheme for the visual language model is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Fine-Tuning Scheme for the Visual Language Model.

Since publicly available LLMs do not contain sufficient knowledge about specific national traffic regulations or the detailed interpretation of visual driving situations, the model undergoes targeted fine-tuning using a structured and annotated dataset. Each training example combines visual input (a static image or video frame) with textual descriptions, identified road objects, and references to relevant traffic rules. During training, the model receives these paired requests and results, allowing it to learn how to associate visual patterns with rule-based explanations and educational logic.

Also, after fine-tuning, the LLM can interpret the situations described in the table and automatically generate educational explanations (informational content) and test tasks. For example, for an image depicting a car approaching a pedestrian crossing without traffic lights, the model will generate a brief educational description of the situation along with an explanation of the rules, a question with multiple answer choices related to the potential behavior of the driver, and an explanation of the correct answer with reference to the regulatory framework. This approach enables the automated generation of content for various scenarios, tailored to the user’s level and learning context. Additionally, this method allows for effective scaling of educational content without requiring human involvement for the manual creation of each task. An example entry of the training dataset for fine-tuning the LLM is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Example Table of Training Samples for Fine-Tuning the LLM.

Using the presented format, a unified database of examples can be maintained, serving not only as a training dataset for the LLM but also as a source for generating new variations of scenarios with different difficulty levels. This is particularly important in cases where the simulator needs to adapt to the user’s progress, providing adaptive learning based on the history of responses.

3.6. Retrieval-Augmented Generation Integration for Traffic Data

Regular data updating regarding legislation and local specifics of traffic rules arises in developing a VR simulator for learning rules using an LLM. This challenge is critically important for both the accuracy of the generated educational content and for ensuring alignment with the real conditions of the traffic environment in which user training or testing will take place.

Most publicly available LLMs (such as GPT, Claude, Gemini, etc.) are trained on large datasets from open sources that cover a wide range of topics but do not always contain the latest versions of local laws or specific traffic rules, which are periodically updated. In the case of traffic rules, even a slight change in the wording of a traffic regulation can significantly alter the context of a task, affecting the correct answer and the content’s compliance with current legislation. For example, regular updates pertain to changes in priority at specific types of intersections, new traffic signs, their interpretations and images, and updates regarding speed limits in particular areas and regional initiatives or experimental traffic solutions in large cities. These changes may remain unknown to the LLM if it has not explicitly been fine-tuned on current regulatory documents or does not have access to regularly updated knowledge bases.

Additionally, a significant challenge is the localization of content. Traffic rules may share a standard structure across many countries but often differ substantially in detail. For example, regulations regarding roundabouts or stopping and parking rules may have different implementations in Ukraine, Poland, Germany, and the USA. Therefore, the language model must be aware of general rules and adapt responses to the specific jurisdictional environment in which the simulator will be used. Without such adaptation, there is a risk of generating false, inappropriate, or potentially dangerous educational content that contradicts current regulations.

In the context of addressing the issue of regularly updating the knowledge of the LLMs regarding traffic rules and local regulatory frameworks, one of the approaches is using the RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) architecture []. This approach effectively overcomes the limitations of traditional language models, which operate solely based on pre-training and cannot dynamically update their knowledge after the training phase.

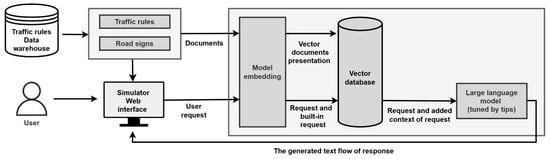

Before formulating a response, the model searches for relevant information in an external database (for example, using vector search) and then integrates the retrieved fragments into the response context, generating logically structured and factually accurate content. The scheme for generating educational information and test questions with retrieval-augmented generation is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Scheme for Generating Educational Information and Test Questions with Retrieval-Augmented Generation.

The system begins by sourcing structured data on traffic rules and road signs from a dedicated data warehouse, which are transformed into vector representations through model embedding. These vectors are stored in a vector database that supports semantic search, allowing the simulator to retrieve contextually relevant information when a user submits a request via the web interface. The LLM, fine-tuned with domain-specific prompts, uses the retrieved context to generate accurate and adaptive textual responses that enhance the educational experience within the simulator.

Two key sets of structured data were formed to implement the RAG approach in the VR simulator system: current traffic rules and signs. These datasets contain all necessary attributes for semantic search: point number, category, description of the situation, or content of the rule. They are updated following official sources. They are automatically imported into the vector index used by the retrieval component of the system. Examples of the dataset for current traffic rules and the dataset for current traffic signs are presented in Table 6 and Table 7. Table 6 illustrates the structured dataset of national traffic regulations used as a primary knowledge base for the retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) component. These records ensure that the simulator’s educational content remains legally accurate and continuously synchronized with current legislative updates.

Table 6.

Examples of current traffic rules.

Table 7.

Examples of current traffic signs.

Table 7 presents the dataset of standardized traffic signs integrated into the semantic search index to support visual recognition and contextual reasoning. This information enables LLM to generate precise descriptions, questions, and explanations that accurately reflect the meaning and application of each sign in simulated driving scenarios.

Several typical informational blocks and test tasks have been produced in fine-tuning the LLMs and their application for generating educational content for the VR simulator on traffic rules. The generated informational blocks describe situations on the road, explain the logic of driver behavior according to traffic rules, and are classified by difficulty level. Test tasks are formed based on visual scenes and educational content, containing multiple answer options, and are accompanied by a precise formulation of the correct answer. Generation occurs through structured queries to the LLM, which specify the format, expected style of material presentation, number of answer options, and explanation logic. This approach ensures consistency, adaptability to specific traffic situations, and scalability for generating new educational scenarios. Examples of the educational informational blocks and test questions generated by the LLM are presented in Table 8 and Table 9. Table 8 demonstrates how the fine-tuned large language model produces educational informational blocks linked to specific timestamps in the spherical video stream. These blocks serve as adaptive learning prompts that explain real traffic situations and reinforce the correct interpretation of driving rules through contextual guidance.

Table 8.

Examples of Educational Informational Blocks Generated by the LLM.

Table 9.

Examples of Test Questions Generated by the LLM.

Table 9 provides examples of automatically generated test questions derived from the same visual and textual data used in the instructional blocks. The inclusion of multiple-choice questions with verified answers ensures objective assessment, allowing the simulator to evaluate user understanding and dynamically adjust the training complexity based on performance.

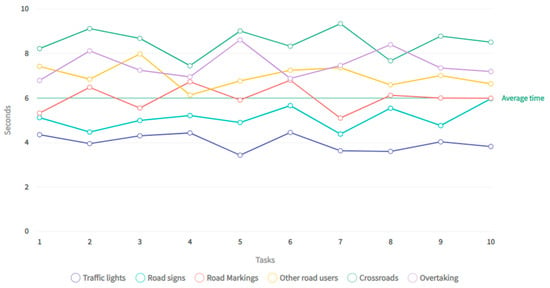

3.7. Data Structures and Performance Evaluation

To effectively compare the generation time of tasks by the LLM across different categories of test tasks, it is essential to account for the specifics of each category and the characteristics of question phrasing. Tasks related to various aspects of traffic rules, such as traffic lights, road signs, intersections, overtaking, markings, and other road users, can significantly differ in complexity regarding the automatic formulation of tasks. This is due to the varying number of elements to be considered when creating questions and the variability of scenarios associated with these categories. To ensure the accuracy of the comparison in task generation time, restrictions were placed on the length of questions and answers included in the queries to the LLM. Questions are limited to 150–200 characters, while each of the four answer options must be within 50–80 characters. This helps to create equal conditions for task generation across all categories, keeping time comparisons representative for similar text volumes. Figure 10 illustrates the average generation time for tasks in each category, allowing a clear view of how the type of situation affects the efficiency of the generation process.

Figure 10.

Chart Representing the Average Generation Time of Tasks by Categories.

Comparing the generation time of tasks across different categories provides insights for optimizing the performance of the LLM within the educational simulator for learning traffic rules. This comparison allows for identifying the most effective strategies for automating the creation of test tasks, considering each category’s specific characteristics [,]. The differences in generation time between categories may indicate the need for further model tuning, particularly in optimizing algorithms for particular situations.

The time values on the chart represent the average generation time for a single task in each category. These data are based on the history of task generation with text length restrictions applied. Generation time varies depending on the complexity and specificity of the situation. Categories related to traffic lights and road signs have the shortest generation time, as these situations typically require fewer details and simpler descriptions. The Markings and Other Road Users categories demand more time to describe the rules and scenarios associated with the traffic situation. Intersections are the most complex category, as they involve the interaction of multiple road users, traffic signs, and lights, requiring more careful task generation. The Overtaking category also requires additional effort to create realistic and contextual situations, increasing the generation time. The average task generation time for all categories is 6.35 s. This figure accounts for the total time spent creating tasks for various situations. It reflects the effectiveness of the generation under uniform constraints on the text length of questions and answers.

Integrating LLMs into generating educational content and test tasks in the VR simulator for learning traffic rules has significantly improved learning quality, adaptability, and scalability. The LLM reduces the workload on content developers and contributes to forming a personalized, interactive, and motivationally appealing educational ecosystem that can adapt to changes in legislation and new pedagogical approaches.

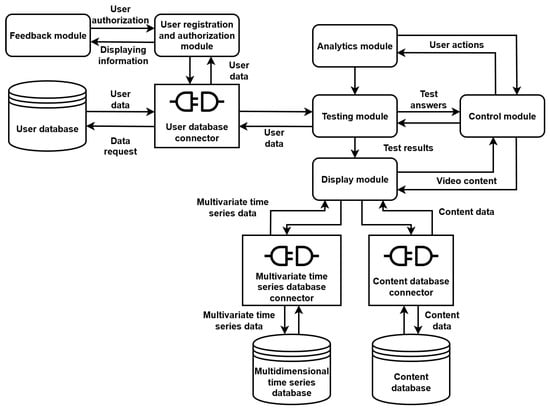

4. Features of the Virtual Simulator Implementation

The software implementation of the developed virtual simulator is based on a client–server architecture [,], which enables the distribution of data processing tasks between the server and the client (web browser). This approach enhances the system’s scalability and ensures efficient performance across different usage scenarios. This architecture facilitates efficient resource management, enabling the simulator to handle multiple users and large datasets effectively while maintaining a responsive user experience.

The client side is implemented as a web-based application that provides the simulator’s user interface and supports integration with virtual reality devices for displaying spherical video streams. The application is developed using HTML for markup, CSS for design and styling, and JavaScript libraries to enable interactivity and dynamic functionality. The idea of using JavaScript libraries to implement the virtual simulator, utilizing spherical video playback for learning traffic rules and acquiring driving skills, lies in leveraging VR technologies [] to create a more engaging and practical learning experience. The use of JavaScript libraries provides flexibility and customization in the design and structure of the simulator, which can enhance its effectiveness in the educational process.

The server side of the virtual simulator is developed using Node.js technology []. It manages user registration and authentication, storage and streaming of spherical videos, implementation of user testing logic, and analysis of test results. The server-side software architecture of the virtual simulator designed for learning traffic rules through spherical video playback includes the following key components:

- 1.

- User Registration and Authentication Module: This module creates new users and identifies existing simulator users.

- 2.

- User Database Connector: This module facilitates communication with the database that stores user data, personal settings, history of completed tasks, and testing results.

- 3.

- Content Database Connector: This module communicates with the database containing content, consisting of spherical videos depicting real traffic situations.

- 4.

- Multidimensional Time Series Database Connector: This module interacts with the database that stores information about camera rotation coordinates, questions for assessing users’ knowledge of traffic rules, and possible answer options.

- 5.

- Display Module: This module plays panoramic videos for users, allowing them to observe real traffic situations, virtual graphic elements with prompts and explanations, or questions and answer options.

- 6.

- Testing Module: This module is responsible for timing and positioning questions related to traffic rules, displaying to users the current traffic situation depicted in the still frame of the panoramic video, and storing their response results.

- 7.

- Analytics Module: This module collects user data and their response outcomes to help improve the virtual simulator and develop more effective test tasks.

- 8.

- Management Module: This module allows system administrators to configure settings for the virtual simulator, add new content, and manage user access.

- 9.

- Feedback Module: This module enables users to seek assistance and receive feedback about the virtual simulator.

The scheme of the structure of the software modules of the server part of the virtual simulator is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Structure Diagram of Software Modules for the Server Side of the Virtual Simulator.

The virtual simulator creates a strong sense of presence, allowing users to perceive a 360-degree environment as if they were inside a real vehicle. This immersive experience motivates learners to participate more actively in the training process, fostering a sense of responsibility in decision-making. The feeling of presence is achieved by dynamically adjusting the displayed spherical image based on the user’s head movements when wearing a virtual reality headset. A distinctive aspect of spherical video playback is that the camera’s viewing angle changes in response to the headset’s orientation relative to the initial playback position. To maintain realism, this initial camera angle must correspond to the vehicle’s turning angle depicted in the video.

To record camera rotation data at every specific moment of the video and to manage information about questions and answer options displayed at designated timestamps, a multidimensional time series structure is employed. Each entry in this structure, identified by a timestamp, stores data on the vehicle’s current turning coordinates, display parameters, and the associated question block, which includes the question text, available answer choices, and the correct response.

The camera rotation angle value (visualizationAngle) is calculated as the sum of the vehicle’s rotation angle, retrieved from the database for the corresponding video playback interval, and the current rotation angle of the virtual reality headset. Equation (2) presents the calculation which ensures that the displayed perspective is accurately aligned with the user’s head movements, enhancing the immersive experience in the virtual environment.

where currentAngle represents the vehicle’s rotation angle at the current moment of video playback, while userAngle denotes the current rotation angle of the virtual reality headset.

The structure of the multidimensional time row is shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Structure of Multidimensional Time Series Data.

To minimize data redundancy in the database, timestamps and their corresponding vehicle rotation angles are stored at variable time intervals, which depend on the degree of rotational activity—the smaller the angle changes, the longer the interval between timestamps. To achieve smooth visualization of camera rotation between stored data points, an interpolation method is applied to compute the rotation angle for each second of video playback. The interpolation process begins by locating two consecutive database records of the vehicle’s rotation angles (angle1, angle2) with their respective timestamps (time1, time2), between which the current playback time (currentTime) lies. Equation (3) and Equation (4) present the determination of the interpolation interval duration (timeDiff) and the change in rotation angle over that period (angleDiff).

Equation (5) presents the change in rotation angle per second for the specified interval (angleStep).

Equation (6) presents the current playback time within the interpolation interval (interpolationTime) which determined by subtracting the timestamp at the start of the interval (time1) from the current playback time (currentTime).

Equation (7) presents the interpolated value of the vehicle’s rotation angle at the current moment of video playback (currentAngle).

The obtained interpolated value of the vehicle’s rotation angle is used to calculate the camera rotation angle (Equation (2)).

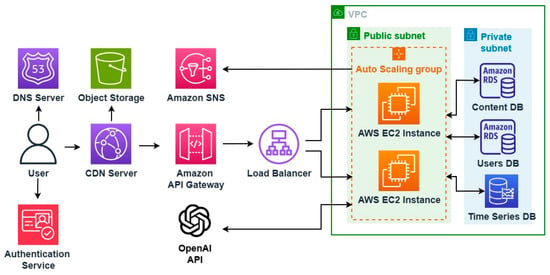

Cloud services can provide computational power, high data transfer speeds, and scalability, crucial for implementing a virtual simulator for learning traffic rules using spherical video playback. Cloud services offer several advantages for streaming spherical videos used in the virtual simulator for learning traffic rules:

- High Availability: Cloud services offer high availability, ensuring that learning materials are accessible to users at any time, regardless of location.

- Scalability: Cloud services can scale, allowing more users to access learning resources simultaneously, reducing server load and improving video content streaming speed.

- Cost Savings: Utilizing cloud services can help lower infrastructure costs, eliminating the need to build and maintain storage and streaming infrastructure for videos.

- High Speed: Cloud services provide high communication speeds, enabling users to access videos, facilitating the effective learning of traffic rules quickly.

- Data Security: Cloud services offer high data security, ensuring that videos and users’ personal information are protected from unauthorized access and data theft.

- Ease of Use: Cloud services allow for easy and rapid addition of new video materials and updates to prompts and test questions, making the learning process more flexible. This includes the ability to implement new traffic rules and update prompts in line with legislative changes, ensuring the relevance of the educational material.

The scheme of cloud architecture of a virtual simulator is presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Cloud Architecture Diagram of the Virtual Simulator.

To implement the virtual simulator for learning traffic rules using spherical video playback, Amazon Web Services [,] was used, including Route53, CloudFront, API Gateway, EC2, S3, Amazon Timestream, RDS, and SNS.

Route53 directs user requests to web applications operating in the cloud environment. CloudFront distributes content to users with minimal latency and high data transfer speed. API Gateway is designed to create, publish, maintain, monitor, and secure API requests for accessing data and the simulator’s logic. EC2 is used for performing computational tasks. S3 stores spherical video files of vehicle movement. Amazon Timestream stores multidimensional time series information about camera rotation coordinates at the current time, display coordinates, and content blocks of questions. RDS stores user data, personal settings, history of completed tasks, and testing results. SNS is used to communicate with users and gather feedback and suggestions regarding the simulator’s work via email.

Additionally, the OpenAI API is used to access the OpenAI LLM’s API, allowing the usage of its features and the fine-tuning process.

5. Results

Starting with the virtual simulator, the user enters their email address and password (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

User Login Screen.

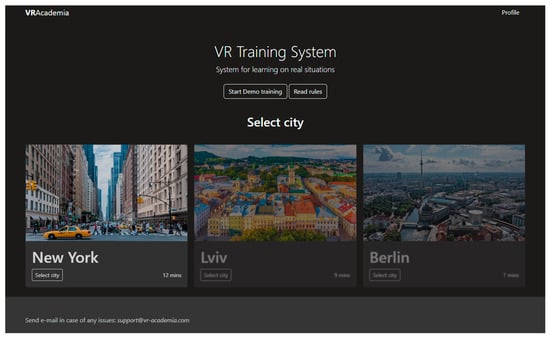

After entering the correct password, the user is presented with the main page of the virtual simulator, displaying a list of all available training sessions. These sessions feature video footage from different cities, showcasing various traffic intersections, road markings, intersection types, and the complexity of the traffic situations depicted in the videos. The main page of the virtual simulator is illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Training Selection Screen.

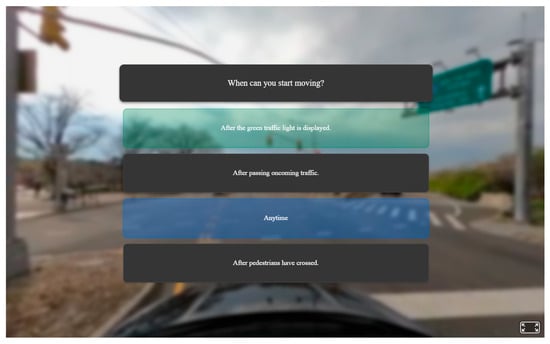

After the user selects a training session, the spherical video content for the session is loaded and begins to display (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Spherical Video Content Display Screen.

At specified time intervals, the video playback pauses, and a question with answer options related to the depicted traffic situation appears on the screen. An example of the screen displaying a test question is illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Test Question Display Screen.

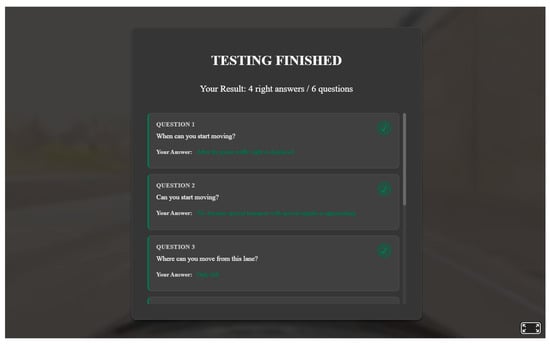

After completing the training session, the user is presented with a table showing the results of their answers to the test questions, the correct answers, and an overall test score (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Test Results Display Screen.

Before testing the virtual simulator, participants underwent traditional video-based instruction that included two-dimensional educational videos and multiple-choice quizzes. While this method provided basic theoretical knowledge, it lacked interactivity and real-world contextualization, limiting learners’ ability to apply traffic rules in dynamic situations. To evaluate the improvement achieved through the proposed system, a study was conducted with 30 university students enrolled in a traffic rule training course who completed both traditional and simulator-based learning modules. The results demonstrated a 27% improvement in test accuracy after completing the simulator-based lessons compared to traditional video-based instruction. Participants also reported a 32% increase in engagement and confidence when learning through the spherical video interface. These findings confirm the simulator’s capacity to enhance both theoretical understanding and practical application of traffic rules.

6. Discussion

The scientific novelty of using spherical videos in developing the virtual simulator model for learning traffic rules lies in the ability to create a highly realistic virtual environment for driving education, thereby enhancing road safety. Spherical videos provide a panoramic view of the virtual road and an authentic depiction of traffic situations, enabling simulator users to feel as if they are on the road, considering all contextual details such as weather conditions, lighting, and the behavior of other drivers and pedestrians. Additionally, the developed virtual simulator can be integrated with different technologies, such as artificial intelligence, to generate diverse and adaptive training scenarios. This capability supports the creation of additional modules for complex driving conditions, traffic emergencies, or situational awareness enhancement. The simulator is particularly beneficial for novice drivers who lack on-road experience or those who struggle with specific traffic rules. Furthermore, it can be employed to assess the knowledge and skills of active drivers, helping reinforce best practices and ultimately contributing to improved road safety at a societal level.

The positive learning outcomes observed in this research align with previous studies emphasizing the pedagogical benefits of immersive learning technologies. Prior investigations into virtual and augmented reality systems have consistently demonstrated increased learner motivation, attention, and material retention when immersive visualization techniques are applied. Similarly, studies on 360° and spherical video education have confirmed their capacity to create authentic, context-rich environments that mimic real-world experiences. The present work extends these findings by integrating Petri net–based behavioral modeling with AI-driven automated content generation, which together establish both pedagogical structure and scalable adaptability. This combination not only reinforces realism and interactivity but also enables efficient expansion of the simulator’s content base.

A major innovation of this study lies in employing LLMs and visual language models (VLMs) for generating educational materials and testing content automatically. Earlier approaches to virtual driver education required extensive manual preparation of question banks, annotations, and video metadata, which often resulted in limited adaptability and time-consuming updates. The proposed system automates these processes, enabling real-time synthesis of contextual test questions, answer explanations, and scenario-based feedback. The introduction of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) further ensures factual consistency with current editions of national traffic regulations, addressing a long-standing limitation of general-purpose models trained on non-specialized corpora. Thus, the integration of LLMs and RAG architectures represents a substantial methodological advancement in educational content automation.

From a technological standpoint, the cloud-based architecture implemented through Amazon Web Services (AWS) components ensures high availability, scalability, and security of both multimedia and analytical data. This infrastructure allows for the seamless distribution of spherical videos, adaptive testing modules, and user performance analytics across multiple platforms. These findings are consistent with established literature on the benefits of cloud-based virtual learning systems, which highlight their efficiency, accessibility, and resilience in multi-user educational contexts. The simulator’s modular architecture and web-based client interface also facilitate deployment across heterogeneous environments, ranging from standard browsers to VR headsets, enhancing inclusivity and usability.

Despite these advantages, the research presents certain limitations. The current evaluation primarily addresses short-term learning improvements and has not yet established a direct correlation between simulator performance and real-world driving outcomes. Future longitudinal studies should explore knowledge retention, behavioral adaptation, and long-term safety impacts. Additionally, while the fine-tuning of the LLM on traffic-rule-specific datasets improved contextual precision, its effectiveness remains dependent on the completeness and accuracy of regulatory data. Periodic legislative updates may require continuous retraining or integration with dynamic retrieval systems. Furthermore, although spherical videos offer high realism, they restrict interactive freedom compared to 3D-rendered environments. Expanding the system toward hybrid or fully simulated 3D environments could enhance scenario diversity and user agency.

Looking ahead, future research may explore several promising directions. Incorporating adaptive learning analytics could allow the simulator to dynamically adjust scenario difficulty based on user performance, thus personalizing the learning trajectory. Expanding the model’s multilingual and jurisdiction-specific capabilities would also enable broader international adoption. Moreover, coupling the simulator with biometric feedback systems (such as eye tracking or EEG) could yield valuable data on cognitive load, stress levels, and attention distribution during training. Finally, integrating reinforcement learning–based behavioral agents could allow the simulator to reproduce complex interactions among multiple virtual drivers, pedestrians, and vehicles, further increasing realism and unpredictability in advanced training scenarios.

7. Conclusions

Models for studying the states of the virtual simulator were developed based on Petri net theory, allowing for the exploration of the designed system’s dynamics. The use of a Petri net allows for precise modeling of concurrent processes and user-system interactions within the simulator, clearly representing the flow of actions, decisions, and feedback. This ensures accurate analysis of system behavior, synchronization of learning events, and validation of logical consistency in traffic scenario simulations.

A method for the automated synthesis of educational material and test questions for learning traffic rules using visual LLMs was established. The automated synthesis of educational materials and test questions using visual LLMs represents a novel approach that integrates AI-driven content generation directly into traffic rule training.

A model for determining the camera rotation angle was developed, ensuring realistic content display within the virtual simulator. The model for calculating camera rotation angles is a technical contribution that enables accurate and smooth visualization of real-world driving perspectives within the simulator.

The cloud software architecture of the virtual simulator, based on a modular principle, was designed. Key algorithms for operating the system and software, characterized by cross-platform compatibility, were constructed. The modular cloud-based software architecture is a design that ensures scalability, cross-platform functionality, and efficient operation of the virtual simulator system.

The developed virtual simulator is an effective tool for learning traffic rules and can be recommended for use in schools and other organizations engaged in driver training. Using spherical video, the simulator allows users to practice traffic rules in realistic scenarios. Through contextual prompts in specific situations, users can select appropriate actions and receive feedback on the correctness of their execution. The study results demonstrate the simulator’s high effectiveness in enhancing users’ knowledge of traffic rules. The creation of a realistic, feedback-driven virtual simulator based on spherical video technology constitutes a practical and validated innovation that improves the effectiveness of traffic rule education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and V.T.; Formal analysis, O.B.; Investigation, O.P.; Methodology, A.K.; Project administration, A.K.; Resources, O.P.; Software, A.K.; Supervision, V.T.; Validation, V.T., O.B. and O.P.; Visualization, A.K.; Writing—original draft, O.B.; Writing—review and editing, V.T. and O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| VLM | Visual Language Model |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

References