Abstract

This study addresses the problem of automatic attack detection targeting Linux-based machines and web applications through the analysis of system logs, with a particular focus on reducing the computational requirements of existing solutions. The aim of the research is to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of machine learning models capable of classifying system events as benign or malicious, while also identifying the type of attack under resource-constrained conditions. The Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 was employed as the primary source of data. To mitigate the challenge of high computational complexity, model optimization techniques such as parameter quantization, knowledge distillation, and architectural simplifications were applied. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approaches significantly reduce computational overhead and hardware requirements while maintaining high classification accuracy. The findings highlight the potential of optimized machine learning algorithms for the development of practical early threat detection systems in Linux environments with limited resources, which is particularly relevant for deployment in IoT devices and edge computing systems.

1. Introduction

The Linux command line provides extensive capabilities for system administration; however, in most cases, it is exploited by adversaries to execute malicious actions such as downloading and launching malware, escalating privileges, or exfiltration data. Similarly, web applications are a frequent target of attacks, with approximately 80% of web-based intrusions being carried out through HTTP/HTTPS requests, according to OWASP []. Such activities often leave traces both in operating system logs and in application logs, making them a primary source of information for attack detection.

Properly configured event auditing, combined with traditional signature- and rule-based detection systems, can identify malicious activity even at its earliest stages. However, this approach often proves ineffective against modern attacks, where an adversary may remain undetected within the infrastructure for extended periods while performing minimal actions. Moreover, rule-based methods are frequently unable to detect malicious payloads embedded within obfuscated commands.

To address this problem, researchers have begun applying machine learning and natural language processing techniques to analyze system events and identify anomalies. For example, in ref. [], a novel approach to classifying Security Operation Center (SOC) events is presented, which involves defining a set of new features through graph-based analysis and performing classification using a deep neural network model.

Another approach to analyzing Linux shell commands is discussed in ref. [], where the authors employ the ShellCore neural network. They compiled a large dataset containing both benign and malicious commands extracted from various Internet of Things malware samples. The proposed method demonstrated high accuracy.

On the other hand, the author of ref. [] explores the application of natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning techniques for analyzing command-line inputs collected through the audited tool. Particular attention is given to shell command tokenization, their transformation into numerical vectors using Hashing Vectorizer, and the training of models for detecting malicious commands.

Modern methods for detecting malicious activity in Linux systems face two key limitations. First, high-accuracy log analysis models based on deep architectures typically require significant computational resources, which complicates their use in environments with limited processing capabilities []. Second, traditional signature-based and heuristic approaches are often insufficient for identifying new or modified attack variants, since they rely on predefined rules and are frequently unable to adapt to changing adversary behavior. An additional challenge is posed by the structure of system logs: events contain a large number of variables and parameters, which can lead to model overfitting on insignificant details or artificial patterns present in synthetic datasets. Therefore, there is a need to develop a resource-efficient approach for detecting and classifying malicious activity in system events, combining optimized event preprocessing and the use of compact models in such a way that high accuracy and performance are maintained under limited computational constraints.

Despite significant progress in applying machine learning models to security log analysis, most existing research is oriented toward server or cloud computing environments, where resources are not a critical constraint []. Such models often assume the availability of powerful GPUs, large amounts of RAM, and constant network connectivity. However, in real infrastructures—including IoT devices, industrial controllers, remote branch servers, and edge systems—these capabilities are often unavailable. As a result, high-accuracy algorithms become practically unusable in environments with limited computational capacity []. Therefore, the problem of effectively transferring threat detection models to low-resource environments remains insufficiently explored and requires the development of specialized optimization techniques and data preprocessing methods.

In this work, we propose an approach for detecting malicious commands within Linux events using optimized transformer architectures. The primary emphasis is on developing a resource-efficient solution by employing the BERT-base-uncased model and its variants in combination with optimization procedures such as knowledge distillation and parameter quantization. We investigate model compression techniques, including quantization and distillation, to produce lightweight threat-detection systems that achieve accuracy levels close to the baseline while significantly reducing resource consumption. Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We have developed models to detect and classify malicious security events at the tactical level.

- We developed a lightweight detector that, using parameter quantization and knowledge extraction, achieves 99% accuracy and is approximately 5 times faster than a baseline BERT-based deep learning model.

- We implemented a classifier that assigns detected malicious events to MITRE ATT&CK tactics with an overall accuracy of 99% and an average inference time of 0.0017 s per event.

- We demonstrated that the resulting system can rapidly and accurately identify malicious activity in Linux environments, showcasing the potential of optimized machine learning models for early threat detection in resource-constrained settings.

This paper is organized as follows. We formulate the problem and objectives and highlight the main contributions of the study in Section 1. In Section 2, we’ll look at algorithms for detecting malicious commands in Linux. In Section 3, we describe the research methodology. In Section 4, we present the architecture of the proposed solution and describe its properties. In Section 5, we describe the data preparation procedure. In Section 6, we present simulation results for the proposed solution to detect malicious commands in Linux. The conclusions and future work are discussed in Section 7.

2. Review of Existing Approaches

We reviewed some of the most recent and highly cited studies addressing the detection of malicious commands in Linux systems. For instance, in ref. [], the authors present the LOLAL platform, which is capable of detecting Living-Off-The-Land attacks and is based on representing command-line text using word vectorization techniques to enhance the efficiency of the employed ensemble.

In another study [], an intrusion detection system is presented that leverages large-scale pretraining of a language model on tens of millions of command-line entries to enhance the effectiveness of attack detection.

On the other hand, the authors of ref. [] propose a transformer-based command classification system that leverages the generalization capabilities of large language models (LLMs) to achieve accurate classification and efficiently detect rare dangerous commands through transfer learning.

Given the critical importance of real-time ransomware protection, ref. [] proposes the use of the extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF) to collect information on system calls related to active processes and to derive insights directly at the kernel level. In this study, two machine learning models—a decision tree and a multilayer perceptron—are implemented within eBPF.

However, these approaches have certain limitations. Transformer- and neural network-based models (e.g., ShellCore, LOLAL) require large amounts of labeled commands for training, which can be challenging given limited access to malicious scenarios. Integrating models into the Linux kernel or deploying transformers demands substantial computational resources, making them impractical for some systems. Furthermore, many solutions are tailored to specific scenarios (e.g., IoT, containers, or virtualization) and do not adapt well to general Linux environments.

Particular attention should be given to the Digraph-MMB study [], which employs directed graphs to construct a multimodal model for multi-stage (APT) attacks in Linux environments. A key advantage of Digraph-MMB is its use of graph neural networks (GNNs) to effectively model complex relationships and interactions between commands, enabling more accurate detection of sophisticated multi-stage attacks and achieving high classification accuracy. Moreover, the model demonstrates exceptional recognition performance, with an F1-score of approximately 99.9%, representing one of the best results on the Linux-APT-Dataset-2024. However, a significant drawback of this approach is its high resource consumption: the use of GNNs and multi-stage analysis demands substantial computational power and memory, making it challenging to deploy this mechanism in resource-constrained systems, such as edge devices or IoT infrastructures.

Unlike Digraph-MMB, our solution operates more efficiently on less powerful hardware by foregoing computationally expensive GNNs and utilizing optimized transformer models, including the bert-base-uncased and the lightweight TinyBERT with knowledge distillation and quantization. At the same time, we maintain comparable classification accuracy, ensuring practicality and scalability across a wide range of Linux environments and resource-constrained devices.

As the core component of our solution, we employed the BERT model (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), which is designed for pretraining deep bidirectional representations on unlabeled text, taking into account both left and right context at all layers. This architecture allows fine-tuning with just a single additional output layer [], enabling the construction of highly accurate classifiers—with minimal architectural modifications—as demonstrated in our experiments. These classifiers are specifically tailored for our task: detecting malicious activity within SIEM security events and classifying it according to the MITRE framework.

Unlike Digraph-MMB, we relied solely on this transformer and did not employ Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for several reasons.

First, constructing APT attack chains requires precise knowledge of how the APT scanner operated during dataset generation. Due to the absence of detailed information about its behavior, correlating individual events even on a single host within a short time window is difficult, since the tool may have executed attacks using multiple, unrelated tactics concurrently.

Secondly, the classification of individual events alone enables SOC analysts to promptly detect discrete stages of an APT attack and, crucially, to prevent its further progression.

Another study [] presents an intrusion detection system based on a large language model (CLLM) trained on tens of millions of command lines in a cloud production environment. Despite its high scalability and accuracy, the unoptimized BERT-based model requires substantial resources for deployment.

A similar situation is observed in []. The proposed model is based on Llama, which typically has more parameters than BERT-family models, also resulting in high resource requirements without additional optimization. While this approach significantly improves accuracy and reduces false positives compared to baseline models, the number of missed attacks remains relatively high, with overall accuracy around 81%.

Table 1 presents the results of the comparative analysis of the works described above.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of existing approache.

The described models are not ideal for very low-power devices (e.g., IoT or edge devices with extremely limited CPUs); however, CLLM and LlamaIDS can be deployed in enterprise infrastructures, especially after undergoing optimization.

The study [] advances graph-based approaches for detecting attacks on web applications. The core idea involves constructing a Web Attack Behavior Graph (WABG) from log data and using Graph Attention Network (GAT) models to identify attacker tactic-behavior patterns. As part of feature extraction, language models such as BERT are employed to highlight and aggregate important features from raw HTTP request logs and other web application events. The resulting graph represents the sequence and interconnections of various attacker actions, enabling analysis not only of individual requests but also of entire activity chains. The GAT model integrates information from neighboring nodes in the graph, emphasizing the most significant relationships between events, which improves accuracy compared to traditional methods based on analyzing individual commands or requests. Consequently, the system can detect standard attacks (e.g., XSS, SQLi) and identify complex attacker interactions with the application, including bypass maneuvers and multi-step attacks. Test results indicate that PWAGAT achieves high accuracy and accelerates feature construction, making it practically applicable for real-time streaming log analysis.

The study [] focuses on advancing methods for detecting attacks on web applications, particularly XSS (cross-site scripting) and SQL injection attacks, which remain among the most common threats to web resources. The researchers proposed an approach based on deep neural networks (CNN and LSTM) for automatic classification and interpretation of incoming HTTP requests and payloads. The model uses Word2Vec to extract semantic features from textual data, as well as a decoder to convert various attack variants into a standardized format, facilitating the detection of even modified malicious payloads. In experiments, the neural network approach was tested on several public datasets—SQL-XSS Payload, Testbed, and HTTP CSIC 2010—achieving high accuracy ranging from 99.23% to 99.84%, depending on the dataset. Additionally, a BERT-based text classifier was evaluated for certain tests and performed particularly well in analyzing complex and modified requests, reaching accuracy close to 99.9%. The article emphasizes adapting the method to handle real-world query structure violations and attempts to bypass signature-based defenses, ensuring robustness against novel attack techniques.

The study [] employs contrastive learning for the automatic generation of features from PE (Portable Executable) malware samples. Similar to ACKD, the method focuses on creating discriminative data representations by maximizing similarity between similar examples and differences between dissimilar ones. CrowdStrike extended the triplet loss concept by applying a contrastive approach to construct a separated feature space. A key achievement is the development of a novel hybrid loss function capable of generating well-separated representations even on highly imbalanced datasets—a common challenge in cybersecurity, where malicious samples constitute a minority.

Another relevant study [] uses deep learning-based data compression for malware classification while ensuring security. Similar to how ACKD adaptively reweights challenging samples to improve student model training, CSMC applies compression combined with feature extraction of malware families, achieving high classification accuracy while significantly reducing data size (down to 10% of the original). Both approaches combine efficiency and security, making the models more practical for deployment in resource-constrained or sensitive environments.

3. Methodology

We the methodology of this study is based on the development and evaluation of malicious activity detection systems using transformer-based language models from the BERT family and their compact derivatives. The Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 was used as the primary data source—a large synthetic dataset that models the operation of five different Linux hosts and includes both benign and malicious actions aligned with MITRE ATT&CK tactics.

The study began with a systematic data preprocessing pipeline aimed at eliminating environment-specific artifacts, reducing input sequence length, removing host-dependent attributes, and converting events into a unified representation. Unicode normalization (NFKC), whitespace collapsing, anonymization, label encoding, and masking of audit parameters were applied. After transformation, each log entry was represented as an invariant string that minimizes dependence on a particular system environment.

A key component of the methodology was tokenization using the BERT WordPiece tokenizer with a fixed vocabulary. All log events were converted into a standardized text format and transformed into sequences of up to 512 tokens. The tokenization process remained identical for both the binary classification task and the ATT&CK tactic classification task, with only the size of the model’s output layer differing.

Model training followed a teacher–student framework. The full-sized bert-base-uncased model with 12 layers served as the teacher, providing the highest predictive quality but requiring substantial computational resources. The student model was the reduced TinyBERT architecture (4 layers), trained using logit-based knowledge distillation, where the loss function combined cross-entropy with ground-truth labels and KL-divergence between the teacher’s and student’s output distributions. Additionally, an 8-bit post-training quantized variant was explored using Post-Training Dynamic Quantization, where all torch.nn.Linear layers were converted to qint8. This reduced model size and improved CPU performance without requiring retraining. Dynamic quantization changes the internal representation of linear-layer weights from 32-bit floating-point values to 8-bit integers, while matrix multiplications are executed in INT8 with subsequent conversion to float32.

To evaluate cross-host generalization, data from each host were used as a complete test set while the remaining hosts formed the training set. This resulted in five independent teacher models and eliminated leakage of host-specific patterns, allowing us to assess whether the model learns general behavioral profiles rather than memorizing characteristics of a single machine. Student models were trained accordingly using the distilled knowledge from their corresponding teacher.

Inference was performed on both GPU and CPU, with measurements collected for execution time, model size, and peak RAM usage. Evaluation metrics included accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, confusion matrices, ROC-AUC, and PR-AUC, providing a comprehensive assessment of model performance on highly imbalanced data.

4. Architecture of the Proposed Solution

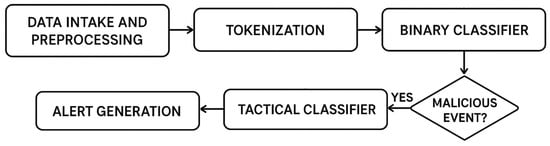

Figure 1 presents the overall architecture of the proposed system.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the proposed system.

The system operates as a sequential processing pipeline consisting of several interconnected stages.

At the first stage, raw system and application logs are collected from Linux audit subsystems or user-space services. These logs may contain diverse event types, including process executions, file accesses, and privilege changes. The data input module ensures unified log ingestion and forwards events for further analysis.

The second stage performs tokenization, transforming each log entry into a structured sequence of tokens using a pretrained BERT tokenizer. During this step, logs are preprocessed and normalized: redundant fields and environment-specific attributes are removed, while semantic elements such as domains, paths, and IP-addresses are preserved in a normalized form. This ensures consistency and reduces noise before model inference.

Next, the binary classifier determines whether a given event corresponds to benign system activity or a potentially malicious action. This stage serves as a filter that separates ordinary operations from those requiring deeper inspection.

If the classifier identifies a log as malicious, it is forwarded to the tactical classifier, which assigns one or more MITRE ATT&CK tactics. This enables not only detection but also contextual understanding of the attack stage within the adversarial kill-chain.

Finally, the results of both classifiers are aggregated in the alert generation module, which produces structured reports or sends notifications to a monitoring system. These alerts contain the original log, its classification label, the detected tactic, and confidence scores.

The proposed architecture uses two classifiers: a binary classifier for detecting malicious content in an event, and a multi-label classifier for determining the attack tactic of a detected malicious event according to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

In the first case, tokenization is applied to the complete textual representation of the event, combining the audit message and related parameters. In the second case, a similar tokenization process is used at the level of preprocessed logs, where each example corresponds to one or more binary indicators of tactics. In both cases, tokenization provides a consistent representation of the data and serves as a link between textual system events and the neural model inputs, enabling effective analysis of context and semantic dependencies within the logs.

Both classifiers are implemented using knowledge distillation, with tokenization performed for both the teacher model (BERT) and the student model (TinyBERT). To ensure identical input representations, both tokenizers were initialized with the same vocabulary.

After completing all stages, the detected malicious events can be forwarded to information security specialists for further analysis and the implementation of appropriate countermeasures.

5. Data Preparation

We used the Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 [] as the data source. The dataset was collected in a test environment that emulated a real infrastructure, enabling the capture of representative system activities and logs. Malicious behavior was simulated by the dataset author using a specialized APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) tool. The modeled attacks encompass privilege-escalation payloads for Linux, recently disclosed vulnerabilities, keyboard-spy emulation, and APT campaigns such as APT41, APT28, APT29, and Turla. All event types were aggregated into a unified dataset by the Wazuh security incident monitoring system [].

The authors of ref. [] conducted a study comparing this dataset with other similar datasets in terms of the presence of various APT strategies. Their result is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Datasets in Terms of APT Attack Strategies.

The tactics included in the Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 are key to the task of detecting and classifying malicious events, as they cover the full spectrum of an attack—from the initial actions of an adversary to the final implementation stage. At the early stages of compromise, the system must detect attempts at unauthorized access, including reconnaissance of the target infrastructure, obtaining initial access, and execution of malicious code. Detection of privilege escalation plays a critical role, as this phase marks the transition from limited access to a level of control sufficient for deep system infiltration and more destructive operations.

In the intermediate phases of the attack, the system must track attempts to establish persistence within the system, lateral movement across network segments, and information gathering about the environment for planning subsequent actions. In the later stages of the attack, when the adversary has already secured their position, it is important to detect credential extraction, the establishment of remote command-and-control channels, data collection, and attempts to cause damage to systems or infrastructure.

Such a multi-layered approach to classifying malicious events enables the model not only to detect individual incidents but also to understand the strategic context of attacks, which is critically important for effective real-time security monitoring on devices with limited resources.

Table 2 shows that the most diverse datasets in terms of the number of attack tactics are Unraveled [] and Linux-APT-Dataset-2024. Despite the former’s growing popularity due to the variety of attack scenarios it contains, it is not yet used in intrusion detection systems (IDS) and is not considered a benchmark dataset. It is also important to note that events related to command execution are described by only a few attributes—session and process identifiers, the process working directory, terminal number, invoked filename, and user identifier—which together are insufficient for solving the task at hand. Therefore, in this work we selected the Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 for testing our approaches.

The dataset is available in two formats: “combine.csv” and “Processed Version.xlsx”, each containing all the fields necessary for the current task. In this work, we focused on the latter.

The primary source of maliciousness criteria is the “FullLog” field, which contains system events indicating an attempted (successful or unsuccessful) attack. Other important fields include “Malicious/General”, which stores a label for malicious (value 1) or benign (value 0) activity and which we subsequently renamed “label” for simplicity, and “rule.mitre.tactic”, which contains a list of all MITRE ATT&CK tactics associated with the event (if it describes malicious activity) and which we renamed “tactic” for convenience. Using these parameters, we performed additional filtering to obtain a list of unique events. A small number of rows were discarded due to empty “FullLog” or “label” fields (i.e., untagged or missing values).

Due to the potential for data leakage between events originating from different machines, the dataset was partitioned into five subsets based on the hostname. Since the dataset is imbalanced both in terms of the number of benign versus malicious events and in the distribution of attack tactics, stratified splitting was applied to ensure proportional representation of each attack tactic in both the training and test sets.

After the initial data acquisition, the preprocessing stage begins. It includes converting text to lowercase, removing extra whitespace (whitespace collapse), handling ASCII characters, and filtering out non-informative or semantically duplicate parameters and variables.

During the ASCII character processing stage, the Normalization Form KC (NFKC) was used. It includes two processes: Compatibility Decomposition, in which each character is replaced with its compatible form, and Canonical Composition, in which possible sequences of characters are re-combined into composed forms.

During this step, blocks with type = NORMAL, type = PROCTITLE, parameters msg = audit(), AUID, UID, GID, EUID, SUID, FSUID, EGID, SGID, FSGID, comm=, and exe= are removed. Process identifiers, IP addresses, hashes, and domains are masked as static tokens of the form <pid>, <ip>, <domain>, and <hash>. File paths are handled separately: during training, label encoding is applied, converting each path into the format <path_N>, where N is its unique identifier. As a result, a mapping dictionary is constructed and later reused during model inference. If the model encounters a path that is not present in the dictionary during testing, it is still transformed in the same manner and appended to the dictionary.

The described data preprocessing procedure was applied both during training and during testing.

This process allows the length of most events to be reduced by more than half without losing the core semantic content. Table 3 presents a statistical comparison of the number of tokens per row in the dataset with and without the proposed data preprocessing method.

Table 3.

Impact of preprocessing on the number of tokens.

Since logs are unstructured text data containing a large number of control characters, parameters, and identifiers, they need to be converted into a unified representation. In this study, tokenization was performed using standard tokenizers from the BERT family architectures, implemented in the HuggingFace Transformers library (using the bert-base-uncased model). Tokenization was carried out using the WordPiece method, which splits text into subwords based on vocabularies containing approximately 30,000 units. Each log was standardized to a fixed length and truncated to 512 tokens, in accordance with BERT’s architectural limitations. As shown in Table 3, a length of 512 tokens is sufficient to process over 99% of events. However, the dataset contains events with a large number of command arguments that are critical for event analysis, which can cause tokenization to exceed the set limit. Such rows were truncated.

6. Model Training

In this study, we used PyCharm v.2024.1.2 running on a computer with Windows 11, an AMD Ryzen 7 5700X (8-core) processor, 32 GB of RAM, and a Gigabyte GeForce RTX 4070 OC 12 GB GPU. The following libraries were used: scikit-learn v1.7.0, transformers v4.53.2, torch v2.7.1+cu118, numpy v2.3.1, seaborn v0.13.2, tqdm v4.67.1, matplotlib v3.10.3, pandas v2.3.1, datasets v4.0.0, and iterative-stratification v0.1.9.

6.1. BERT Variants

Since, in addition to model accuracy, performance indicators such as execution time and resource consumption are equally important for our task, we considered several BERT variants, namely the baseline BERT [], TinyBERT [], MobileBERT [], and DistilBERT []. Each of these models was trained and tested on the previously prepared dataset, followed by measurements of classification accuracy and inference time. The aggregated results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of BERT Variants.

For this task, the data presented in Table 4 show that the baseline BERT, MobileBERT, and DistilBERT achieve nearly identical accuracy. The differences are observed primarily in model inference time. Since the MobileBERT-based approach proved to be the slowest, we excluded it from further consideration.

DistilBERT demonstrated nearly twice the speed of the bert-base-uncased while maintaining identical accuracy.

However, the four-layer TinyBERT shows a significant advantage in inference time: it is 3.8 times faster than the standard BERT and twice as fast as the compressed versions. The drawback of using TinyBERT is a substantial drop in classification performance on malicious samples: based on the obtained Recall (Malicious) metric, the model misses approximately 67% of malicious events, which is unacceptable for real-world SOC operations.

We did not limit ourselves to the speed advantage offered by DistilBERT and sought to improve the accuracy of TinyBERT through knowledge distillation from slower but more accurate models, while retaining a substantial inference-time benefit.

6.2. Knowledge Distillation and Quantization

Model distillation (Knowledge Distillation) is a machine learning technique that involves transferring knowledge from a large, complex model (referred to as the teacher model) to a smaller, more efficient model (referred to as the student model) [].

Instead of relying on hard targets represented by one-hot class encodings, distillation employs soft targets—probability distributions over all possible classes. These soft labels provide richer information about uncertainty and ambiguity in the teacher model’s predictions [,].

The key parameter that controls the softness of the teacher’s predictions and directly influences the student’s training process is the temperature (t).

During distillation, the student’s training process reduces to minimizing a combined loss function L [], calculated as shown in Equation (1):

where LKL is the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the student and teacher predictions, LCE is the cross-entropy loss between the student predictions and the true labels, and is the weighting coefficient.

We used the most common training scheme, in which the pretrained teacher model remains frozen during the student’s training [].

The optimal values of the weighting coefficient (α = 0.5) and the number of training epochs (3) were determined empirically, allowing us to preserve the highest accuracy while minimizing the model’s runtime.

An equally important factor in training is the value of the maximum token sequence length (π), into which the input text is split during tokenization. The maximum value of π for each of the models under study is 512 tokens. We analyzed the lengths of all events collected in the dataset and found that a value of 128 is sufficient to cover more than 99% of the data. Less than 1% of the data have a considerable length, which requires π = 512 for processing. However, it was also found that increasing π significantly raises the time needed for the model to make predictions. The data presented in Table 5 show that when π is increased by a factor of 4, the model’s runtime increases threefold.

Table 5.

Impact of π on Runtime.

It can also be observed that despite the significant speed gain, the classification metric for malicious commands, Recall (Malicious), decreases only slightly—by approximately 2%. Therefore, we subsequently limited π to 128 to cover the 99th percentile of all data.

The standard BERT model was chosen as the training model. For comparison, in addition to the four-layer TinyBERT, its six-layer variant, TinyBERT-6L [], was also used. The performance metrics of both distilled models are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of Distilled TinyBERT Models.

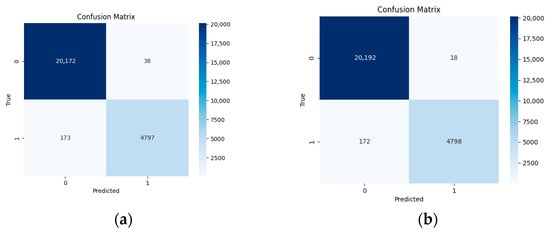

Despite both models achieving nearly identical high classification accuracy, the addition of two extra layers resulted in a significant slowdown (1.43 times). Appendix A contains all the ROC curves and confusion matrices obtained during the experiments presented in this study. Figure A1 show the confusion matrices for the student model and the teacher model, respectively.

Since the dataset is originally imbalanced in terms of the number of benign and malicious events, the analysis of the PR AUC metric plays a crucial role in evaluating the malicious activity detection system. In such conditions, ROC curves may create an illusion of high performance even when the number of false positives is significant, whereas PR curves directly reflect the model’s ability to maintain high precision at a fixed level of recall. The obtained value of PR AUC = 0.990 demonstrates that the model is capable of effectively identifying malicious actions even under severe class imbalance, while maintaining high precision and minimizing the number of missed attacks—a property that is critically important for practical security monitoring systems.

Thus, through distillation, a model was obtained that demonstrates high classification accuracy in detecting malicious activity within events, while significantly accelerating the classification process.

For the teacher model, the following settings were used: the maximum token length was set to 512, the batch size to 8, the AdamW optimizer was applied with a weight decay of 0.01, the warmup ratio was 0.1, and the loss function used was CrossEntropyLoss.

For the distilled model, we additionally applied 8-bit post-training quantization (PTQ). Only the layers of type torch.nn.Linear were quantized, while embedding layers, layer normalization, activation functions, and attention softmax remained unchanged. These transformations reduced the model size by approximately 10 MB while preserving the same classification accuracy, and resulted in roughly a twofold improvement in inference time. Table 7 presents a comparison of the models with 32-bit and 8-bit PTQ quantization.

Table 7.

Comparison of Model Quantization Approaches.

The final size of the binary classification model was 41.48 MB. When processing the entire dataset, peak RAM usage reached 0.97 MB, and the inference time was 639.45 s (approximately 11 min) on a CPU-only machine.

Table 8 presents the attack detection performance across different machines. The consistently high precision, recall, and F1-score values demonstrate the strong stability of the model regardless of the evaluated host.

Table 8.

Accuracy of Attack Stage Detection on Each Machine.

However, the high average accuracy of the model does not eliminate the need to further reduce the proportion of false negatives, as these errors determine the omission of hidden stages in the APT chain and may lead to the execution of subsequent MITRE ATT&CK tactics without detection. It is observed that some malicious events are classified as normal. This can be explained by the fact that certain commands and action sequences in the Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 closely resemble typical administrative behavior, as well as by the tendency of APT operators to use low-profile, slow-moving tactics, which are syntactically and parametrically difficult to distinguish from legitimate actions. These issues may be exacerbated in cases of rare or previously unseen attack patterns (as demonstrated later in experiments with the Command and Control, Collection, and Credential Access tactics), as well as by high variability in command parameters.

Nonetheless, because attackers often need to employ specific techniques and tactics that do not align with legitimate user behavior to achieve their objectives, such actions can still be detected with a high probability at other stages of the attack.

6.3. Attack Classification by Tactics

The dataset under study contains 12 attack tactics described using MITRE terminology: Defense Evasion, Privilege Escalation, Discovery, Initial Access, Execution, Persistence, Lateral Movement, Impact, Collection, Credential Access, Command and Control, and Reconnaissance. Table 9 presents the distribution of these tactics in the dataset after removing duplicates and cleaning rows with empty values.

Table 9.

Distribution of Events by Tactics.

The fully processed dataset contains 114,851 rows, of which 91,804 are benign events and 23,046 are malicious. Table 9 shows that the number of tactics is significantly higher than the number of malicious events. This is because a single attack event can correspond to multiple tactics simultaneously (ranging from 1 to 6).

For the subsequent classification of all detected events with malicious activity according to the listed tactics, we also used the baseline BERT model with 3 training epochs and a maximum sequence length of 128.

The inference time on the entire dataset was 39.02 s (0.0017 s per event). Since the model works exclusively on data that had already been classified as attack events, this result can be considered quite acceptable and not requiring significant improvement. Table 10 presents the results of classifying malicious activity events by tactics.

Table 10.

Learning outcomes.

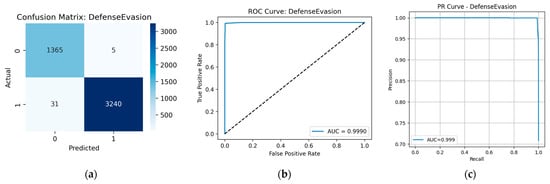

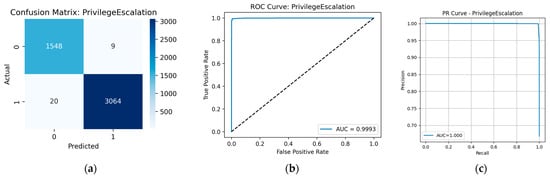

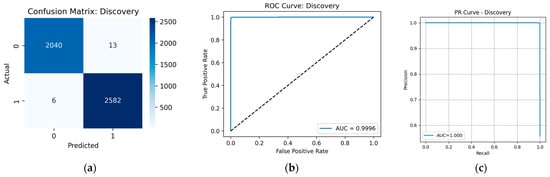

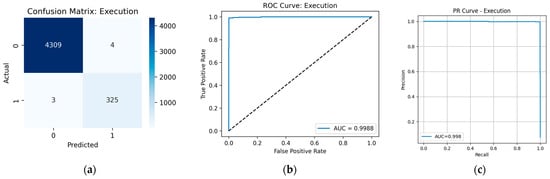

The model demonstrated high reliability across almost all tactics. The highest quality indicators were observed for Defense Evasion, Privilege Escalation, Discovery, and Execution, where the values of precision, recall, and F1-score exceed 0.99. Indeed, from the data presented in the Confusion Matrix (Figure A2a, Figure A3a, Figure A4a and Figure A5a, respectively), only minor classification errors can be seen. ROC and PR analysis also confirms the high quality of the model with respect to these tactics: the area under the curve (AUC) is within 0.999, which is very close to the ideal value. Figure A2b, Figure A3b, Figure A4b and Figure A5b show the ROC curves, illustrating the high sensitivity and specificity of the model at different threshold values. Figure A2c, Figure A3c, Figure A4c and Figure A5c show the PR curves.

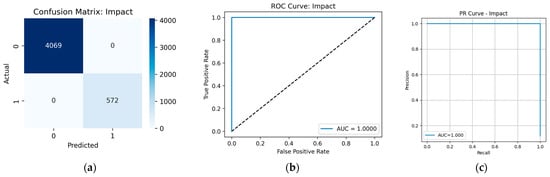

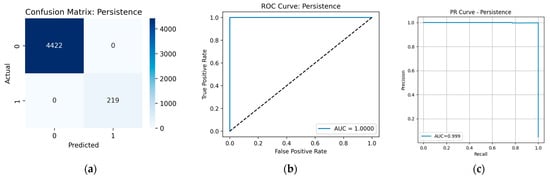

Perfect accuracy was achieved for the classification of the Impact and Persistence tactics: Figure A6 and Figure A7 show the confusion matrices, PR curves and ROC curves. However, it should be noted that events of the Impact tactic have a specific, unique format inherent only to them. Therefore, once maliciousness is confirmed, it is straightforward to assign an event to this tactic.

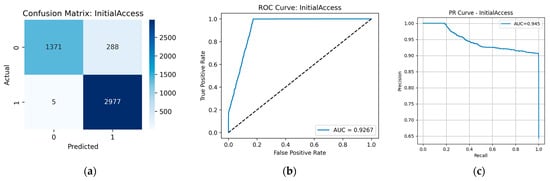

Also, Table 9 shows a high recall value of 0.9977 for the Initial Access tactic, indicating that the model virtually does not miss true instances of this tactic. However, the precision is notably lower at 0.9120. Indeed, Figure A8 demonstrates that approximately 9% of the predictions were false positives.

Referring to Table 9, this tactic appears in roughly 65% of all malicious events. Therefore, the predominance of this tactic and the overlap of its characteristic malicious-event patterns with those of other tactics together lead to the reduction in precision.

It is worth noting that only for 2149 events (about 9%) Initial Access is the sole tactic. For the remaining 12,756 events, this tactic appears together with one or more of Discovery, Defense Evasion, Persistence, and Privilege Escalation. At the same time, as described above, the classification accuracy for each of these tactics exceeds 99%.

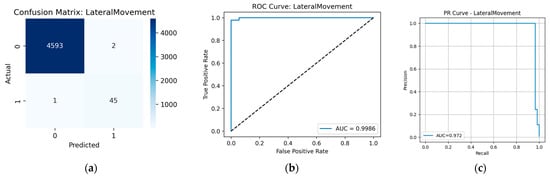

The opposite situation is observed with Lateral Movement: the model confused other events with this category, as indicated by the precision value of 0.98. However, the number of errors for this tactic amounted to less than 3% (see Figure A9), which is a good result despite the relatively small size of this attack class (see Table 9).

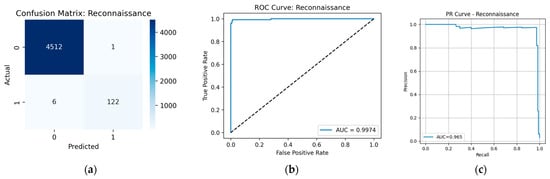

It is worth highlighting the high reliability of the model in detecting Reconnaissance attacks. Although the format of events belonging to this tactic is very similar to that of most other predominant attack types (represented as web logs), and the total number of events for this tactic is less than 3% (see Table 10) with none overlapping with other tactics, the model was still able to classify this type of attack with high reliability. Indeed, Figure A10 shows that the model made both false positive and false negative errors in approximately 4% of cases.

The model failed to classify attack types such as Collection, Credential Access, and Command and Control. This is due to their extremely small sample size in the entire dataset (a total of 39 events, which is less than 0.2% of the whole dataset). Such a quantity does not allow for proper model training. Nonetheless, it was found that the accuracy of classifying these events as malicious was approximately 80% (all of which belong to Credential Access), although the attack type itself was not identified correctly. This relatively low accuracy is explained by the nature of each event individually: upon closer examination, it becomes clear that the detected activity does not exhibit pronounced attack patterns as observed for other tactics, and could be performed by either an attacker, an administrator, or even an ordinary user. However, since the attack process is not limited to such activity alone, the resulting models are able—based on other events within the sequence—to very likely identify both individual stages of an attack’s progression and classify them according to MITRE ATT&CK, as demonstrated for other, more prevalent tactics.

The average metrics across all tactics (including the less represented Credential Access, Command and Control, and Collection) are: precision—0.7991, recall—0.7781, and F1-score—0.7848.

The final size of the multi-label classification model was 41.48 MB. When processing the entire dataset, peak RAM usage reached 0.99 MB, and the inference time was 486.25 s (approximately 8 min) on a CPU-only machine.

7. Conclusions

In this study, models were developed for the detection and classification of malicious events according to attack tactics. When designing the system, the primary focus was on reducing computational requirements while maintaining competitive accuracy. As a result of applying optimization techniques such as parameter quantization and knowledge distillation, a model was obtained that can detect malicious activity with 99% accuracy while operating approximately five times faster than the baseline deep learning BERT model.

A model was also developed that is capable of classifying previously detected malicious activity according to MITRE ATT&CK tactics with high accuracy (overall accuracy of 99%) and high performance (inference time per event of approximately 0.0017 s).

Overall, the resulting system is capable of rapidly and accurately classifying security events for the presence of malicious activity, demonstrating the potential of optimized machine learning algorithms for developing practical early threat detection systems even in resource-constrained environments.

In future work, we plan to broaden the spectrum of malicious activity by increasing the number of attack tactics and augmenting the overall number of malicious examples. Additionally, we intend to investigate other language models and neural network architectures to identify the most optimal configuration in terms of classification accuracy and inference time. We also plan to conduct a study to evaluate the robustness of the proposed system against adversarial attacks.

Author Contributions

M.R.—Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, research, manuscript—writing; M.B.—Methodology, research, manuscript—writing, supervision; M.L.—Conceptualization, methodology, research, manuscript—draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant provided by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation in accordance with the subsidy agreement (agreement identifier 000000C313925P4G0002) and the agreement with the Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences dated 20 June 2025, No. 139-15-2025-011.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10685642 (accessed on 6 October 2025)., Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10685642 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Comparison of distilled TinyBERT models: (a) confusion matrix for the student model; (b) confusion matrix for the teacher.

Figure A2.

Prediction results for the Defense Evasion tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A3.

Prediction results for the Privilege Escalation tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A4.

Prediction results for the Discovery tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A5.

Prediction results for the Execution tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A6.

Prediction results for the Impact tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A7.

Prediction results for the Persistence tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A8.

Prediction results for the Initial Access tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A9.

Prediction results for the Lateral Movement tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

Figure A10.

Prediction results for the Reconnaissance tactic: (a) confusion matrix; (b) ROC curve; (c) PR curve.

References

- Alma, T.; Das, M.L. Web Application Attack Detection using Deep Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.03181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Traore, I.; Quinan, P.M.F. Automated Event Prioritization for Security Operation Center using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmary, H.; Anwar, A.; Abusnaina, A.; Alabduljabbar, A.; Abuhamad, M.; Wang, A.; Nyang, D.; Awad, A.; Mohaisen, D. ShellCore: Automating Malicious IoT Software Detection by Using Shell Commands Representation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 2485–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizna, D. Shell Language Processing: Unix command parsing for Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Conference on Applied Machine Learning for Information Security (CAMLIS), Arlington, VA, USA, 4–5 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amgbara, S.; Akwiwu-Uzoma, C.; David, O. Exploring lightweight machine learning models for personal internet of things (IOT) device security. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 24, 1116–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.K.; Sahu, D.; Prakash, S.; Rathore, R.S.; Dixit, P.; Hunko, I. A lightweight framework to secure IoT devices with limited resources in cloud environments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N.C.; Greenewald, K.; Lee, K.; Manso, G.F. The Computational Limits of Deep Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.05558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongun, T.; Stokes, J.W.; Bar Or, J.; Tian, K.; Tajaddodianfar, F.; Neil, J.; Seifert, C.; Oprea, A.; Platt, J.C. Living-Off-The-Land Command Detection Using Active Learning. In Proceedings of the RAID’21: 24th International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses, San Sebastian, Spain, 6–8 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H. Intrusion Detection at Scale with the Assistance of a Command-line Language Model. In Proceedings of the Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), Brisbane, Australia, 24–27 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, P.; Haeri, S.; Cardoso, J.; Gerndt, M. Command-line Risk Classification using Transformer-based Neural Architectures. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodzik, A.; Malec-Kruszyński, T.; Niewolski, W.; Tkaczyk, M.; Bocianiak, K.; Loui, S.-Y. Ransomware Detection Using Machine Learning in the Linux Kernel. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.06452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, P.; An, Z. Digraph-Mmb: A Directed Graph-Based Multimodal Model for Multi-Stage Apt Attack Detection. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5226068 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Alomari, Z. LlamaIDS: Real-Time Detection Model of Zero-Day Intrusions Using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–29 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q. PWAGAT: Potential Web attacker detection based on graph attention network. Neurocomputing 2023, 557, 126725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadhani, J.R.; Vekariya, V.; Sorathiya, V.; Alshathri, S.; El-Shafai, W. Securing Web Applications Against XSS and SQLi Attacks Using a Neural Decoding and Standardization Model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Gong, R.; Xu, K.; Liu, X. Adaptive Contrastive Knowledge Distillation for BERT Compression; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 8941–8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Peng, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, D. CSMC: A Secure and Efficient Visualized Malware Classification Method Inspired by Compressed Sensing. Sensors 2024, 24, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, S. Linux-APT-Dataset-2024 [Data Set], Version 2. 2024. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/5x68fv63sh/2 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Myneni, S.; Jha, K.; Sabur, A.; Agrawal, G.; Deng, Y.; Chowdhary, A.; Huang, D. Unraveled—A semi-synthetic dataset for Advanced Persistent Threats. Comput. Netw. 2023, 227, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.A.M.; Ferrahi, K.S. Building a Novel Graph Neural Networks-Based Model for Efficient Detection of Advanced Persistent Threats. Master’s Thesis, Institut National de Formation en Informatique, Oued Smar, Algeria, July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hugging Face: Bert-Base-Uncased. Available online: https://huggingface.co/google-bert/bert-base-uncased (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hugging Face: TinyBERT_General_4L_312D. Available online: https://huggingface.co/huawei-noah/TinyBERT_General_4L_312D (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hugging Face: Mobilebert-Uncased. Available online: https://huggingface.co/google/mobilebert-uncased (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hugging Face: Distilbert-Base-Uncased. Available online: https://huggingface.co/distilbert/distilbert-base-uncased (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- IBM: What Is Knowledge Distillation? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/knowledge-distillation (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- What Is Knowledge Distillation? A Deep Dive. Available online: https://blog.roboflow.com/what-is-knowledge-distillation/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- From Teacher to Student: Model Distillation for Cost-Effective LLM Deployment. Available online: https://blog.marvik.ai/2025/01/28/from-teacher-to-student-model-distillation-for-cost-effective-llm-deployment/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Xu, C.; Gao, W.; Li, T.; Bai, N. Teacher-student collaborative knowledge distillation for image classification. Appl. Intell. 2022, 53, 1997–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is Model Distillation? Available online: https://builtin.com/artificial-intelligence/model-distillation (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hugging Face: TinyBERT_General_6L_768D. Available online: https://huggingface.co/huawei-noah/TinyBERT_General_6L_768D (accessed on 30 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).