Large Language Models in Mechanical Engineering: A Scoping Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Multi-Modal Applications

1.1.2. Data Challenges in LLM Enhanced Mechanical Engineering

1.2. Practical Implementation Examples

1.3. Rationale and Objectives

1.4. Related Work

1.4.1. CAD-GPT: Synthesising CAD Construction Sequences with Enhanced Spatial Reasoning (Based on Wang et al. [25])

1.4.2. CAD-MLLM: Unifying Multimodality-Conditioned Parametric CAD Generation (Xu et al. [18])

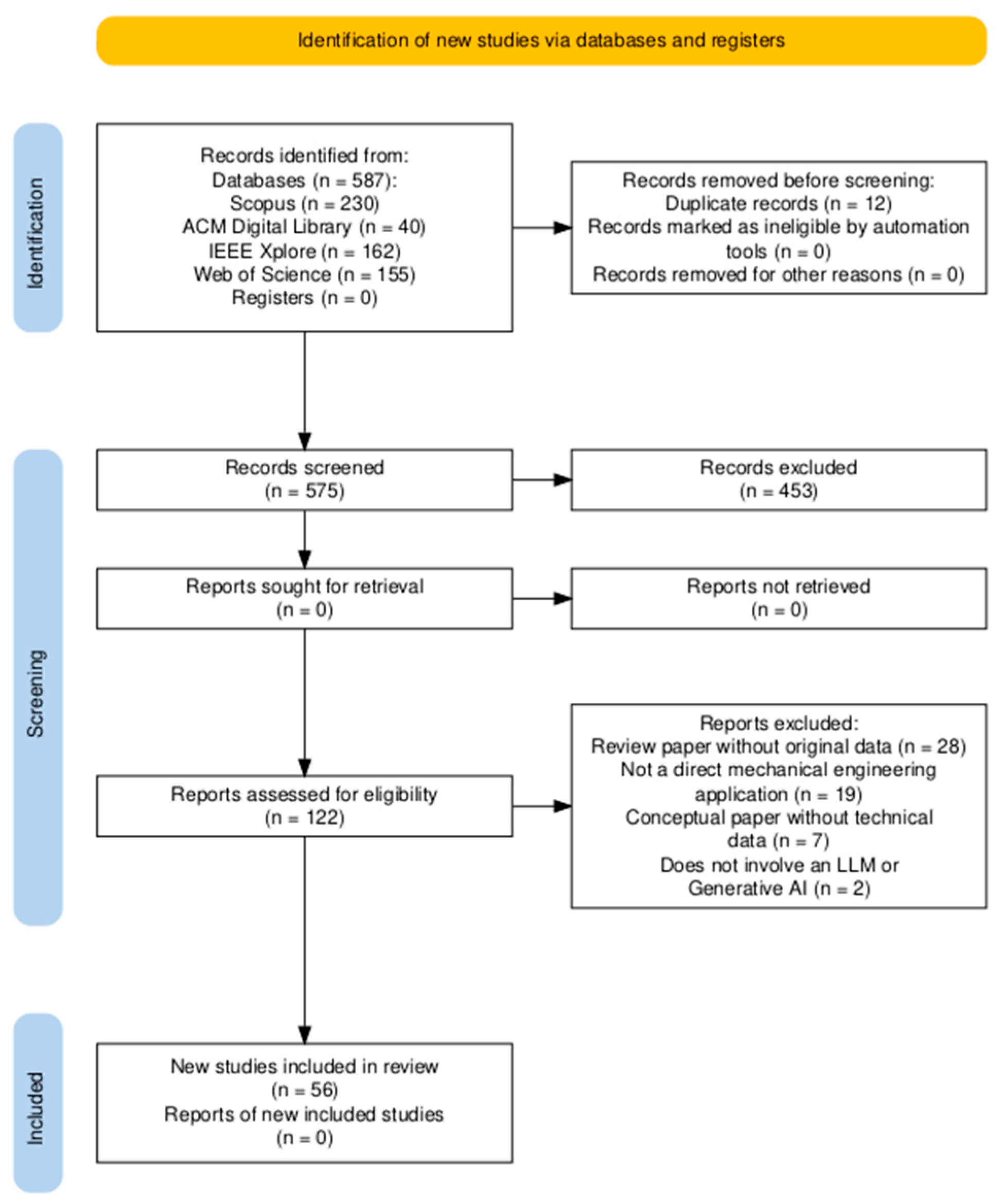

2. Methods

2.1. Research Questions

- What are the current applications of LLMs in mechanical engineering?

- What are the key challenges and limitations in implementing LLMs in this domain?

- How do LLMs complement or replace traditional computational approaches in mechanical engineering?

- What are the emerging trends and future directions for research at the intersection of LLMs and mechanical engineering?

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Source Selection and Screening

- The study describes a direct application, framework, or analysis of an LLM within a mechanical engineering context (design, analysis, manufacturing, knowledge management).

- The publication is a peer-reviewed journal article or conference paper.

- The study was published between January 2020 and the date of the search.

- The article is written in English.

- Studies where LLMs are only mentioned in passing (e.g., in future work sections).

- Editorials, opinion pieces, or non-technical articles.

- Review papers not containing original data or applications.

- Studies not available in full-text.

2.4. Data Charting

2.4.1. Purpose and Approach

2.4.2. Data Charting Form Categories

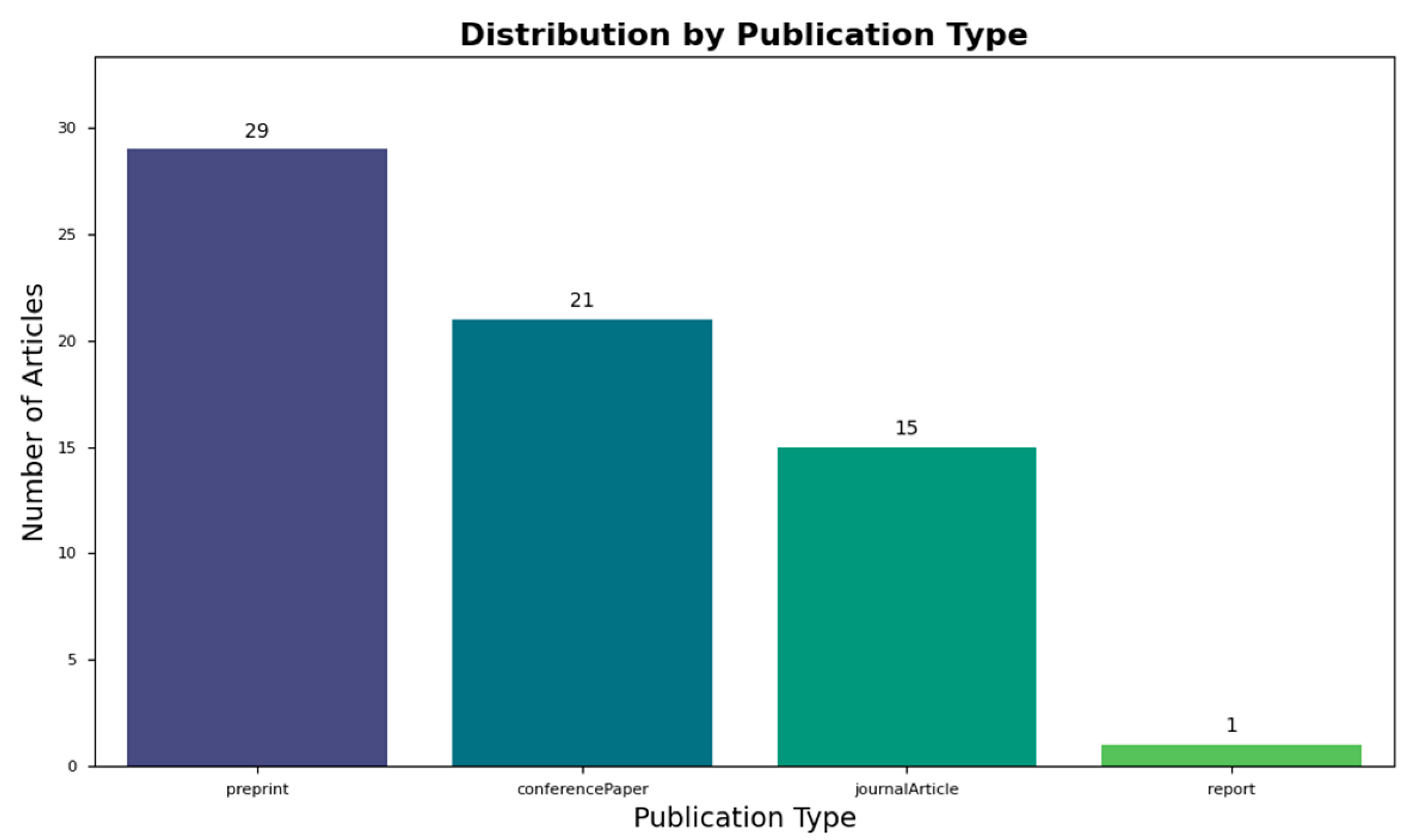

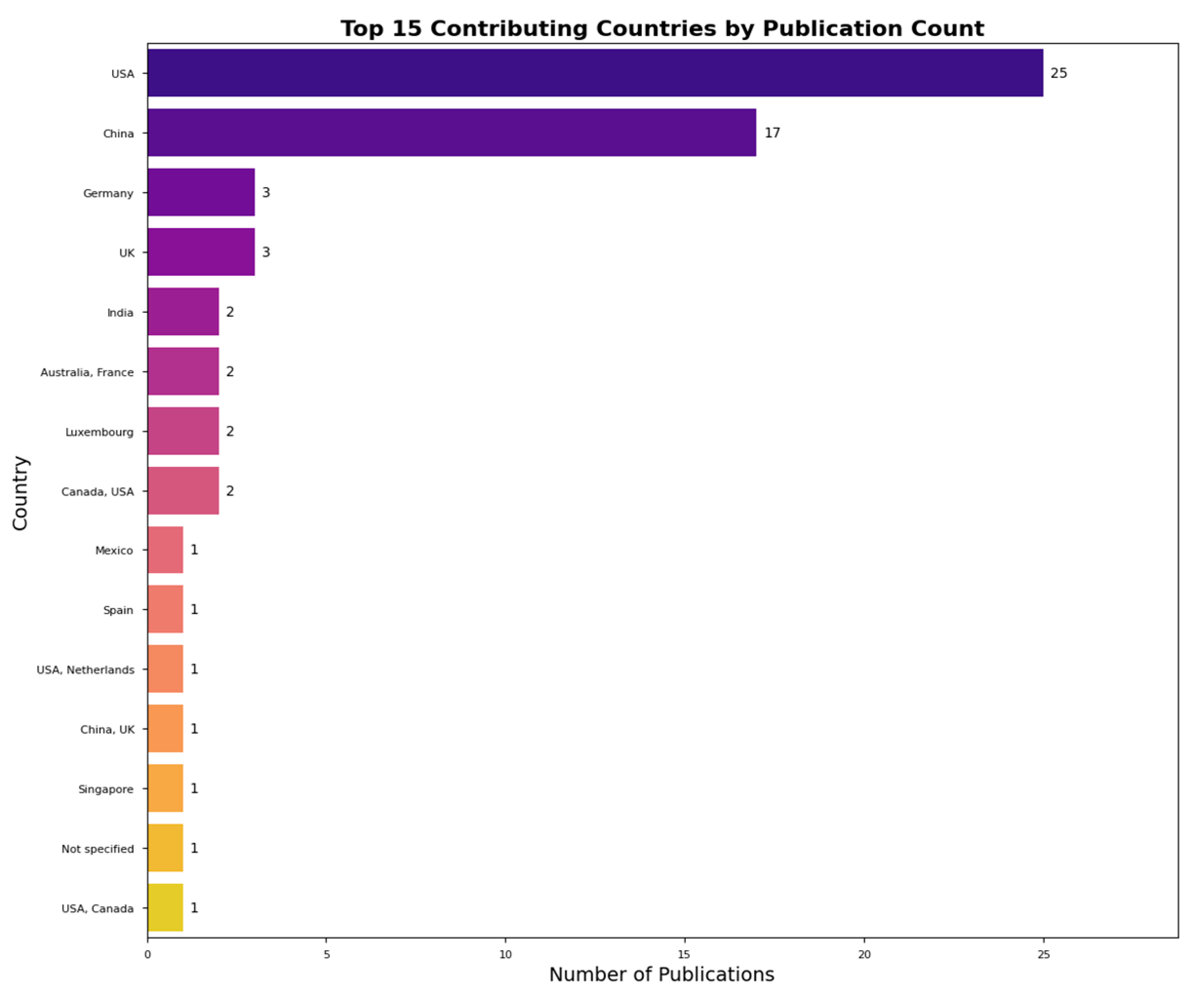

- Source Characteristics: Publication type (e.g., journal article, conference paper), year of publication, country of origin, and the specific engineering domain focus.

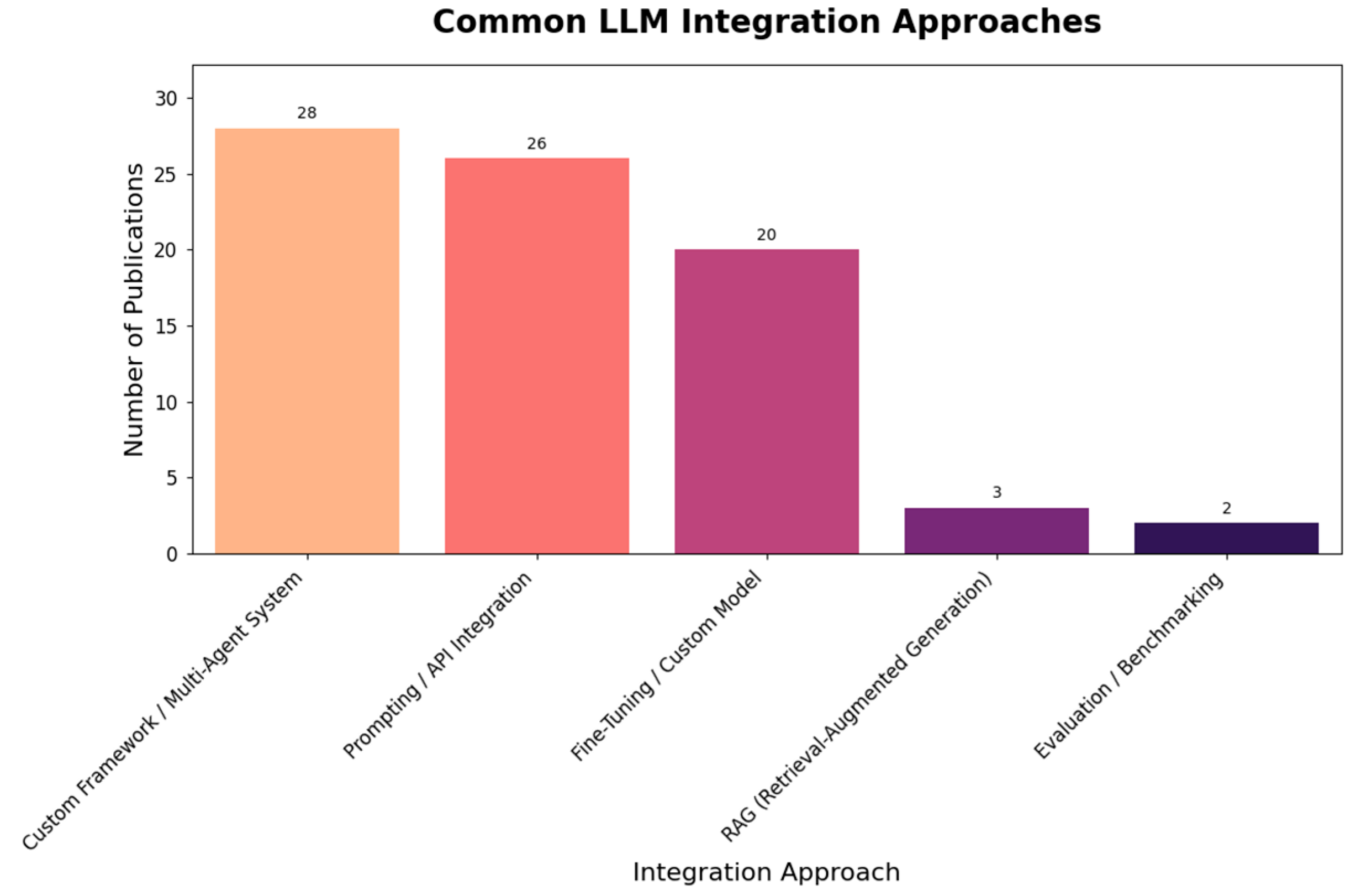

- LLM Implementation Details: The type of LLM used (e.g., GPT-4, Llama 2), the primary application area (design, manufacturing, analysis, knowledge management), the integration approach (e.g., API-based, fine-tuned), and the specific tools or frameworks mentioned.

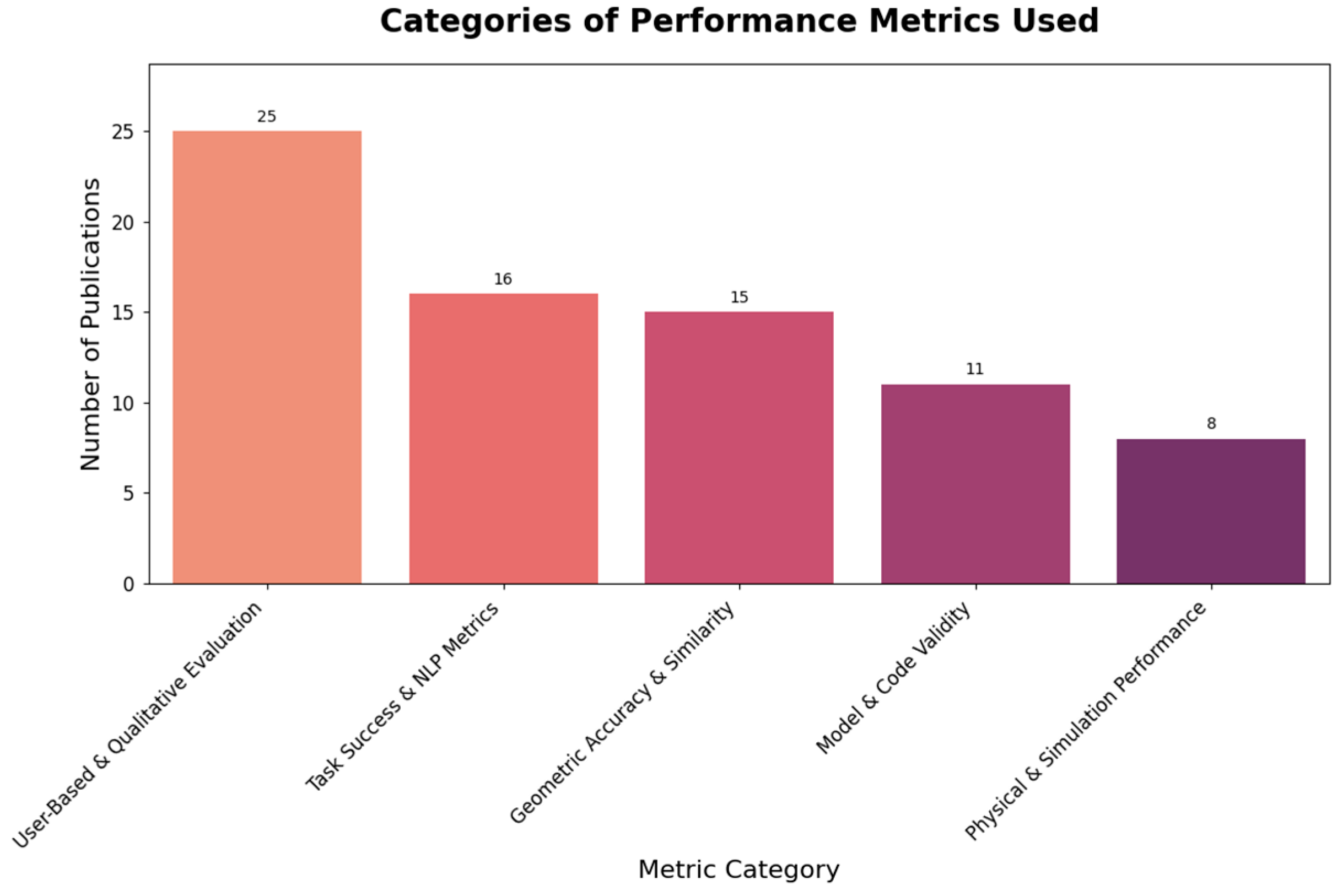

- Engineering Applications: The specific engineering tasks addressed, any traditional methods being augmented or replaced, the performance metrics used for evaluation, and the reported outcomes or key findings.

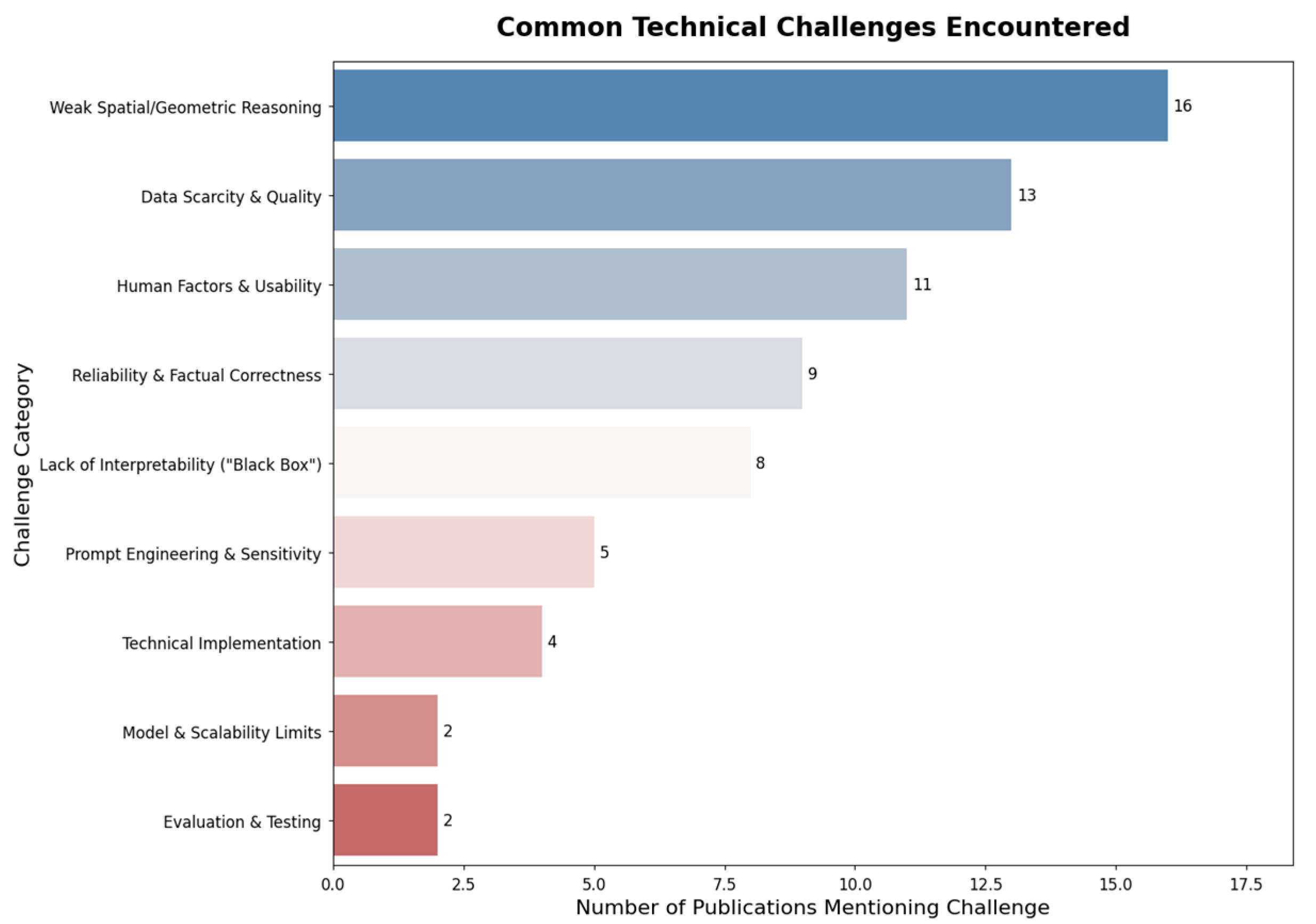

- Implementation Considerations: Any technical challenges encountered, solutions or workarounds that were developed, specific integration methods, and any discussion of safety or validation approaches.

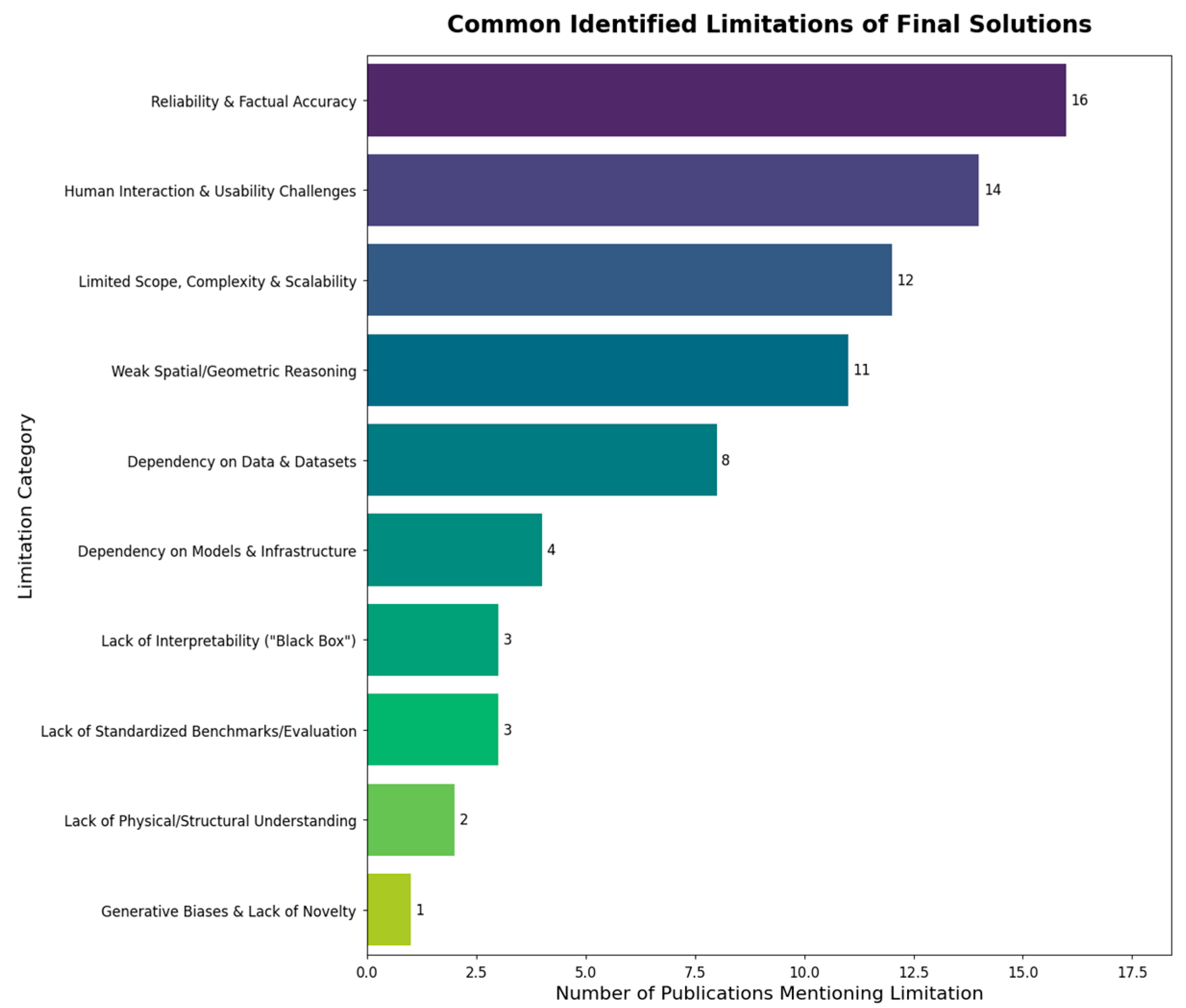

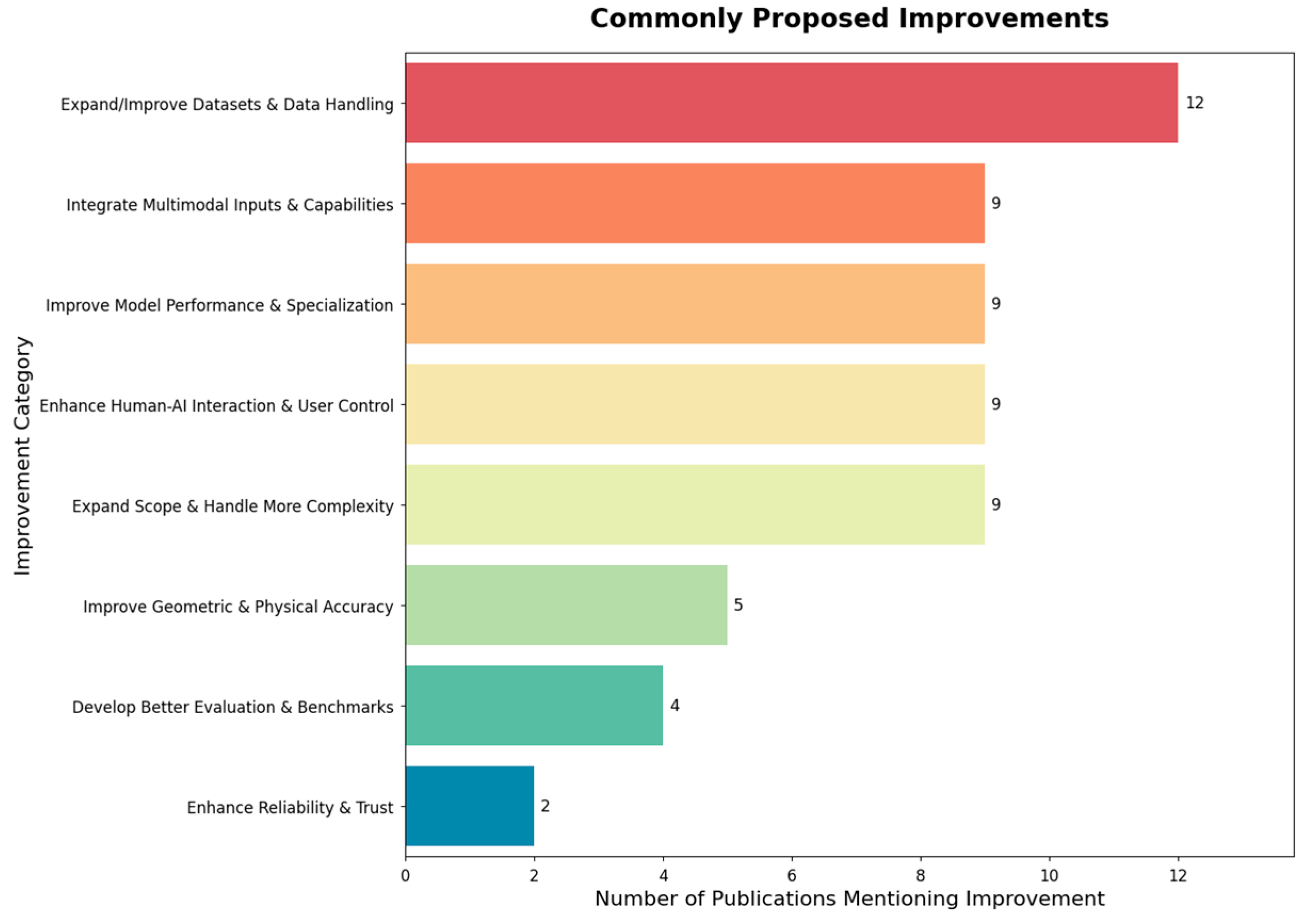

- Future Directions: Any identified limitations of the described approach, proposed improvements, stated research gaps, and identified needs for future development.

2.4.3. Charting Process

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Evidence

3.2. LLM Implementation Details

3.3. Engineering Applications and Evaluation

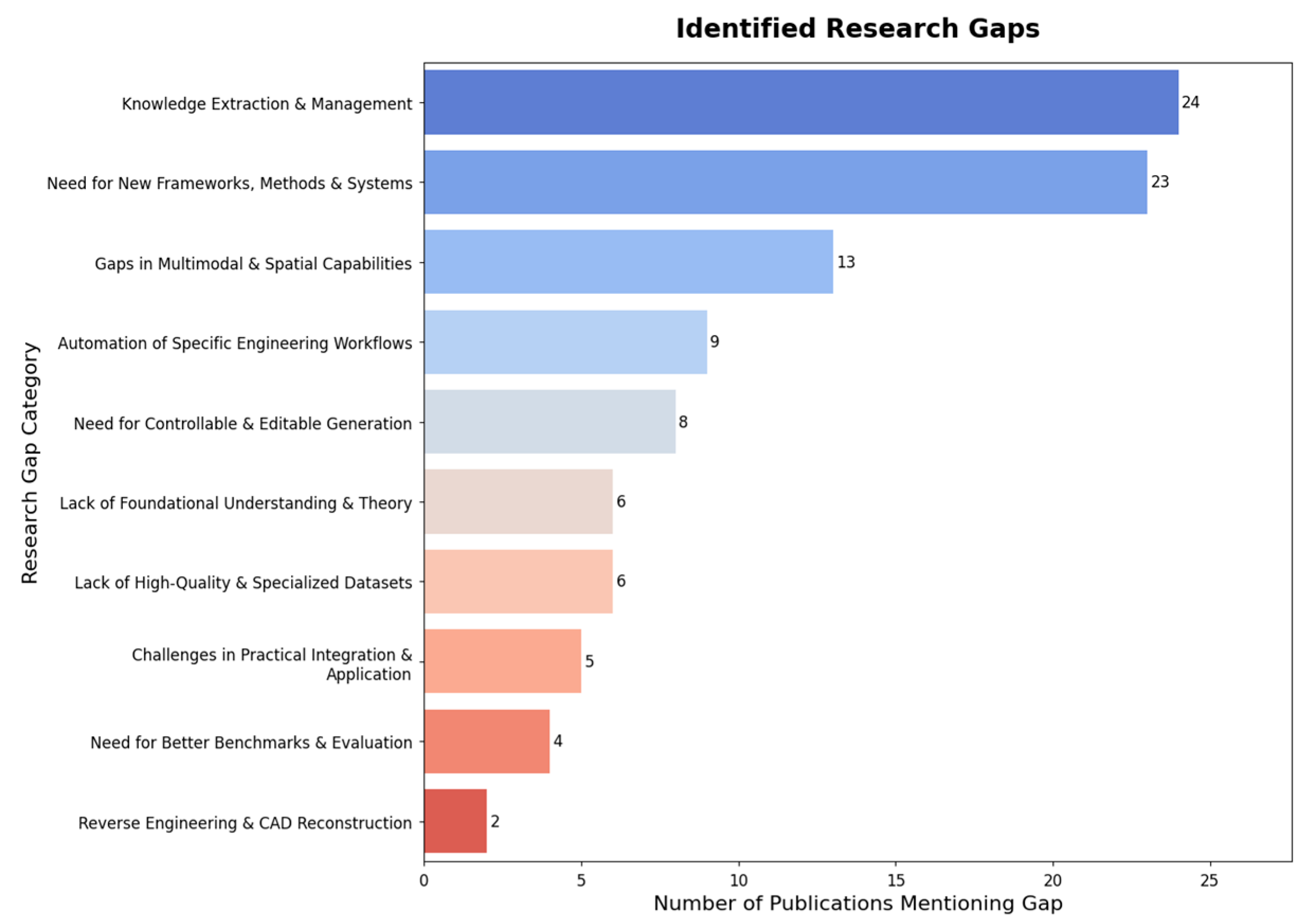

3.4. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Future Directions

4.2.1. Research Needs

4.2.2. Technical Development Priorities

4.2.3. Implementation Challenges

4.3. Implications

- For the Research Community: This review provides a clear, data-driven roadmap for future research priorities. The identified gaps—particularly the need for robust benchmarks, specialized datasets, and solutions to the persistent challenge of spatial reasoning—highlight the most critical areas where innovation is required. The current homogeneity in the field, with its heavy reliance on a few specific models and a concentration of research in limited geographical areas, signals a clear opportunity for diversification. Researchers can contribute by exploring alternative model architectures, developing open-source tools and datasets, and fostering broader international collaboration to enrich the field with new perspectives and approaches.

- For Practicing Engineers and Industry: The current state of the art, as mapped in this review, suggests that LLMs should be viewed as powerful “co-pilots” or “intelligent assistants” rather than autonomous experts. Their demonstrated strengths lie in augmenting the early stages of the design workflow, such as accelerating conceptual ideation, automating the generation of initial CAD models, and assisting in knowledge management tasks. However, the prevalent issues of reliability, factual accuracy, and weak geometric control mean that these tools are not yet suitable for detailed, safety-critical design or analysis without rigorous human oversight. The primary implication for industry is that the value of LLMs can be unlocked today by integrating them into workflows to enhance creativity and efficiency, but this must be coupled with robust validation and verification processes managed by domain experts.

- For Engineering Education: The rapid emergence of LLMs as tools for engineering design signals a necessary evolution in engineering curricula. The findings imply a potential shift in focus from traditional, manual software operation skills towards a new set of competencies centred on human-AI collaboration. Future engineering education will need to incorporate training on “AI literacy,” including the principles of prompt engineering, understanding the inherent limitations and biases of generative models, and developing the critical thinking skills required to validate and critique AI-generated outputs. The ability to effectively leverage these tools as part of the engineering toolkit will be a critical skill for the next generation of mechanical engineers.

4.4. Limitations of This Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ASReview | Active learning for Systematic Reviews |

| CAx | Computer-Aided Technologies (referring generally to CAD, CAM, CAE, etc.) |

| DSL | Domain Specific Language |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MMLM | Multi-Modal Large Language Model |

| PRISMA-SCR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

Appendix A. Search Strategy Details

Appendix A.1. Scopus

Appendix A.2. IEEE Xplore

Appendix A.3. ACM Digital Library

Appendix A.4. Web of Science

Appendix B. Data Charting Form

- LLM Mechanical Engineering Scoping Review.xlsx

Appendix C. Included Sources

- J. Kaplan et al., “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models,” Jan. 23, 2020, arXiv: arXiv:2001.08361. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2001.08361.

- W. Li, G. Mac, N. G. Tsoutsos, N. Gupta, and R. Karri, “Computer aided design (CAD) model search and retrieval using frequency domain file conversion,” Additive Manufacturing, vol. 36, p. 101554, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2020.101554.

- W. Tao, M. C. Leu, and Z. Yin, “Multi-modal recognition of worker activity for human-centered intelligent manufacturing,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, vol. 95, p. 103868, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103868.

- A. Chernyavskiy, D. Ilvovsky, and P. Nakov, “Transformers: ‘The End of History’ for Natural Language Processing?,” in Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Research Track, N. Oliver, F. Pérez-Cruz, S. Kramer, J. Read, and J. A. Lozano, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, pp. 677–693. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-86523-8_41.

- D. Fuchs, R. Bartz, S. Kuschmitz, and T. Vietor, “Necessary advances in computer-aided design to leverage on additive manufacturing design freedom,” Int J Interact Des Manuf, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 1633–1651, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12008-022-00888-z.

- L. Mandelli and S. Berretti, “CAD 3D Model classification by Graph Neural Networks: A new approach based on STEP format,” Oct. 30, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2210.16815. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2210.16815.

- M. C. May, J. Neidhöfer, T. Körner, L. Schäfer, and G. Lanza, “Applying Natural Language Processing in Manufacturing,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 115, pp. 184–189, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2022.10.071.

- B. Regassa Hunde and A. Debebe Woldeyohannes, “Future prospects of computer-aided design (CAD)—A review from the perspective of artificial intelligence (AI), extended reality, and 3D printing,” Results in Engineering, vol. 14, p. 100478, June 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100478.

- L. Regenwetter, A. H. Nobari, and F. Ahmed, “Deep Generative Models in Engineering Design: A Review,” Journal of Mechanical Design, vol. 144, no. 7, p. 071704, July 2022, doi: 10.1115/1.4053859.

- H. Strobelt et al., “Interactive and Visual Prompt Engineering for Ad-hoc Task Adaptation With Large Language Models,” IEEE Trans. Visual. Comput. Graphics, pp. 1–11, 2022, doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2022.3209479.

- S. Zhang et al., “OPT: Open Pre-trained Transformer Language Models,” June 21, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2205.01068. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2205.01068.

- A. A. Chien, L. Lin, H. Nguyen, V. Rao, T. Sharma, and R. Wijayawardana, “Reducing the Carbon Impact of Generative AI Inference (today and in 2035),” in Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Computer Systems, in HotCarbon ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Aug. 2023, pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1145/3604930.3605705.

- P. Christiano, J. Leike, T. B. Brown, M. Martic, S. Legg, and D. Amodei, “Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences,” Feb. 17, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:1706.03741. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.03741.

- J. A. De La Tejera, R. A. Ramirez-Mendoza, M. R. Bustamante-Bello, P. Orta-Castañón, and L. A. Arce-Saenz, “Overview of an AI-Based Methodology for Design: Case Study of a High Efficiency Electric Vehicle Chassis for the Shell Eco-Marathon,” presented at the 2023 International Symposium on Electromobility, ISEM 2023, 2023. doi: 10.1109/ISEM59023.2023.10334852.

- F. Gmeiner, H. Yang, L. Yao, K. Holstein, and N. Martelaro, “Exploring Challenges and Opportunities to Support Designers in Learning to Co-create with AI-based Manufacturing Design Tools,” in Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2023. doi: 10.1145/3544548.3580999.

- H. Jobczyk and H. Homann, “Automatic Reverse Engineering: Creating computer-aided design (CAD) models from multi-view images,” Sept. 2023, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2309.13281.

- J. Kaddour, J. Harris, M. Mozes, H. Bradley, R. Raileanu, and R. McHardy, “Challenges and Applications of Large Language Models,” July 19, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2307.10169. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.10169.

- O. Khattab et al., “DSPy: Compiling Declarative Language Model Calls into Self-Improving Pipelines,” Oct. 05, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2310.03714. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2310.03714.

- M. Kodnongbua, B. Jones, M. B. S. Ahmad, V. Kim, and A. Schulz, “ReparamCAD: Zero-shot CAD Re-Parameterization for Interactive Manipulation,” in SIGGRAPH Asia 2023 Conference Papers, in SA ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2023. doi: 10.1145/3610548.3618219.

- V. Liu, “Beyond Text-to-Image: Multimodal Prompts to Explore Generative AI,” in Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI EA ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2023. doi: 10.1145/3544549.3577043.

- V. Liu, J. Vermeulen, G. Fitzmaurice, and J. Matejka, “3DALL-E: Integrating Text-to-Image AI in 3D Design Workflows,” in Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, in DIS ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2023, pp. 1955–1977. doi: 10.1145/3563657.3596098.

- Y. Liu, A. Obukhov, J. D. Wegner, and K. Schindler, “Point2CAD: Reverse Engineering CAD Models from 3D Point Clouds,” Dec. 07, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2312.04962. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2312.04962.

- Y. Lou, X. Li, H. Chen, and X. Zhou, “BRep-BERT: Pre-training Boundary Representation BERT with Sub-graph Node Contrastive Learning,” in Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham United Kingdom: ACM, Oct. 2023, pp. 1657–1666. doi: 10.1145/3583780.3614795.

- L. Makatura et al., “How Can Large Language Models Help Humans in Design and Manufacturing?,” July 25, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2307.14377. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.14377.

- G. Penedo et al., “The RefinedWeb Dataset for Falcon LLM: Outperforming Curated Corpora with Web Data, and Web Data Only,” June 01, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2306.01116. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2306.01116.

- T. Rios, S. Menzel, and B. Sendhoff, “Large Language and Text-to-3D Models for Engineering Design Optimization,” presented at the 2023 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence, SSCI 2023, 2023, pp. 1704–1711. doi: 10.1109/SSCI52147.2023.10371898.

- E. Ruiz, M. I. Torres, and A. Del Pozo, “Question answering models for human–machine interaction in the manufacturing industry,” Computers in Industry, vol. 151, p. 103988, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.compind.2023.103988.

- S. Ding, X. Chen, Y. Fang, W. Liu, Y. Qiu, and C. Chai, “DesignGPT: Multi-Agent Collaboration in Design,” in 2023 16th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID), Dec. 2023, pp. 204–208. doi: 10.1109/ISCID59865.2023.00056.

- S. Samsi et al., “From Words to Watts: Benchmarking the Energy Costs of Large Language Model Inference,” Oct. 04, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2310.03003. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2310.03003.

- B. Song, R. Zhou, and F. Ahmed, “Multi-modal Machine Learning in Engineering Design: A Review and Future Directions,” July 28, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2302.10909. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2302.10909.

- D. Tas and D. Chatzinikolis, “TeamCAD -- A Multimodal Interface for Remote Computer Aided Design,” Dec. 2023, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2312.12309.

- X. Wang, N. Anwer, Y. Dai, and A. Liu, “ChatGPT for design, manufacturing, and education,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 119, pp. 7–14, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2023.04.001.

- J. Wei et al., “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,” Jan. 10, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2201.11903. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2201.11903.

- S. Wu et al., “BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance,” Dec. 21, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2303.17564. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2303.17564.

- X. Xu, P. K. Jayaraman, J. G. Lambourne, K. D. D. Willis, and Y. Furukawa, “Hierarchical Neural Coding for Controllable CAD Model Generation,” June 30, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2307.00149. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.00149.

- H. Yang, X.-Y. Liu, and C. D. Wang, “FinGPT: Open-Source Financial Large Language Models,” June 09, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2306.06031. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2306.06031.

- B. Zhang and H. Soh, “Large Language Models as Zero-Shot Human Models for Human-Robot Interaction,” in 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Oct. 2023, pp. 7961–7968. doi: 10.1109/IROS55552.2023.10341488.

- S. Zhang, Z. Guan, H. Jiang, T. Ning, X. Wang, and P. Tan, “Brep2Seq: a dataset and hierarchical deep learning network for reconstruction and generation of computer-aided design models,” Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 110–134, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1093/jcde/qwae005.

- M. F. Alam et al., “From Automation to Augmentation: Redefining Engineering Design and Manufacturing in the Age of NextGen-AI,” An MIT Exploration of Generative AI, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.21428/e4baedd9.e39b392d.

- K. Alrashedy, P. Tambwekar, Z. Zaidi, M. Langwasser, W. Xu, and M. Gombolay, “Generating CAD Code with Vision-Language Models for 3D Designs,” Oct. 07, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2410.05340. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2410.05340.

- A. Badagabettu, S. S. Yarlagadda, and A. B. Farimani, “Query2CAD: Generating CAD models using natural language queries,” May 31, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2406.00144. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2406.00144.

- G. Bai et al., “Beyond Efficiency: A Systematic Survey of Resource-Efficient Large Language Models,” Dec. 29, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2401.00625. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.00625.

- Y. Cao, A. Taghvaie Nakhjiri, and M. Ghadiri, “Different applications of machine learning approaches in materials science and engineering: Comprehensive review,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, vol. 135, p. 108783, Sept. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108783.

- L. Chen et al., “Toward Controllable Generative Design: A Conceptual Design Generation Approach Leveraging the Function–Behavior–Structure Ontology and Large Language Models,” Journal of Mechanical Design, vol. 146, no. 12, p. 121401, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1115/1.4065562.

- S. Chen, J. Ding, Z. Shao, Z. Shi, and J. Lin, “Neural surrogate-driven modelling, optimisation, and generation of engineering designs: A concise review,” presented at the Materials Research Proceedings, 2024, pp. 493–502. doi: 10.21741/9781644903254-53.

- V. Chheang et al., “A Virtual Environment for Collaborative Inspection in Additive Manufacturing,” in Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI EA ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3613905.3650730.

- L. Chong, J. Rayan, S. Dow, I. Lykourentzou, and F. Ahmed, “CAD-PROMPTED GENERATIVE MODELS: A PATHWAY TO FEASIBLE AND NOVEL ENGINEERING DESIGNS,” presented at the Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conference, 2024. doi: 10.1115/DETC2024-146325.

- S. Colabianchi, F. Costantino, and N. Sabetta, “Assessment of a large language model based digital intelligent assistant in assembly manufacturing,” Computers in Industry, vol. 162, p. 104129, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.compind.2024.104129.

- A. C. Doris, D. Grandi, R. Tomich, M. F. Alam, H. Cheong, and F. Ahmed, “DesignQA: BENCHMARKING MULTIMODAL LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS ON QUESTIONS GROUNDED IN ENGINEERING DOCUMENTATION,” presented at the Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conference, 2024. doi: 10.1115/DETC2024-139024.

- Y. Du et al., “BlenderLLM: Training Large Language Models for Computer-Aided Design with Self-improvement,” Dec. 2024, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.14203.

- A. Ganeshan, R. Huang, X. Xu, R. K. Jones, and D. Ritchie, “ParSEL: Parameterized Shape Editing with Language,” ACM Trans. Graph., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1–14, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1145/3687922.

- J. Göpfert, J. M. Weinand, P. Kuckertz, and D. Stolten, “Opportunities for large language models and discourse in engineering design,” Energy and AI, vol. 17, p. 100383, Sept. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.egyai.2024.100383.

- D. Grandi, Y. P. Jain, A. Groom, B. Cramer, and C. McComb, “Evaluating Large Language Models for Material Selection,” Apr. 23, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2405.03695. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2405.03695.

- M. U. Hadi et al., “Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Survey of its Applications, Challenges, Limitations, and Future Prospects,” Aug. 12, 2024, Preprints. doi: 10.36227/techrxiv.23589741.v6.

- Y. Huang et al., “TrustLLM: Trustworthiness in Large Language Models,” Sept. 30, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2401.05561. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.05561.

- Y. Jang and K. H. Hyun, “Advancing 3D CAD with Workflow Graph-Driven Bayesian Command Inferences,” in Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in CHI EA ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3613905.3650895.

- A. Jignasu, K. Marshall, B. Ganapathysubramanian, A. Balu, C. Hegde, and A. Krishnamurthy, “Evaluating Large Language Models for G-Code Debugging, Manipulation, and Comprehension,” in 2024 IEEE LLM Aided Design Workshop (LAD), San Jose, CA, USA: IEEE, June 2024, pp. 1–5. doi: 10.1109/LAD62341.2024.10691700.

- M. Jung, M. Kim, and J. Kim, “ContrastCAD: Contrastive Learning-based Representation Learning for Computer-Aided Design Models,” Apr. 2024, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2404.01645.

- T. Kapsalis, “CADgpt: Harnessing Natural Language Processing for 3D Modelling to Enhance Computer-Aided Design Workflows,” Jan. 2024, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.05476.

- R. Kasar and T. Kumar, “Digital Twin and Generative AI for Product Development,” presented at the Procedia CIRP, 2024, pp. 905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2024.06.043.

- M. S. Khan, S. Sinha, T. U. Sheikh, D. Stricker, S. A. Ali, and M. Z. Afzal, “Text2CAD: Generating Sequential CAD Models from Beginner-to-Expert Level Text Prompts,” Sept. 25, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2409.17106. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2409.17106.

- P. Krus, “LARGE LANGUAGE MODEL IN AIRCRAFT SYSTEM DESIGN,” presented at the ICAS Proceedings, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85208784130&partnerID=40&md5=fe0b7c9e9020fd5bd4be3770e62aef59.

- S. Lambert, C. Mathews, and A. Jaddoa, “CONCEPT TO PRODUCTION WITH A GEN AI DESIGN ASSISTANT: AIDA,” presented at the Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education: Rise of the Machines: Design Education in the Generative AI Era, E and PDE 2024, 2024, pp. 235–240. doi: 10.35199/epde.2024.40.

- K. Li, A. K. Hopkins, D. Bau, F. Viégas, H. Pfister, and M. Wattenberg, “Emergent World Representations: Exploring a Sequence Model Trained on a Synthetic Task,” June 26, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2210.13382. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2210.13382.

- X. Li, Y. Sun, and Z. Sha, “LLM4CAD: Multi-Modal Large Language Models for 3D Computer-Aided Design Generation,” in Volume 6: 36th International Conference on Design Theory and Methodology (DTM), Washington, DC, USA: American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Aug. 2024, p. V006T06A015. doi: 10.1115/DETC2024-143740.

- Y. Li et al., “Large Language Models for Manufacturing,” Oct. 28, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2410.21418. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2410.21418.

- Y. Liu et al., “Understanding LLMs: A Comprehensive Overview from Training to Inference,” Jan. 06, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2401.02038. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.02038.

- Y. Liu, J. Chen, S. Pan, D. Cohen-Or, H. Zhang, and H. Huang, “Split-and-Fit: Learning B-Reps via Structure-Aware Voronoi Partitioning,” June 07, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2406.05261. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2406.05261.

- L. Makatura et al., “Large Language Models for Design and Manufacturing,” An MIT Exploration of Generative AI, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.21428/e4baedd9.745b62fa.

- D. Mallis et al., “CAD-Assistant: Tool-Augmented VLLMs as Generic CAD Task Solvers?,” Dec. 18, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2412.13810. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.13810.

- B. Murugadoss et al., Evaluating the Evaluator: Measuring LLMs’ Adherence to Task Evaluation Instructions. 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2408.08781.

- N. Widulle, F. Meyer, and O. Niggemann, “Generating Assembly Instructions Using Reinforcement Learning in Combination with Large Language Models,” in 2024 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Aug. 2024, pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1109/INDIN58382.2024.10774545.

- D. Nath, Ankit, D. R. Neog, and S. S. Gautam, “Application of Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Finite Element Analysis: A Comprehensive Review,” Arch Computat Methods Eng, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 2945–2984, July 2024, doi: 10.1007/s11831-024-10063-0.

- H. Naveed et al., “A Comprehensive Overview of Large Language Models,” Oct. 17, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2307.06435. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.06435.

- K. C. Pierson and M. J. Ha, “Usage of ChatGPT for Engineering Design and Analysis Tool Development,” presented at the AIAA SciTech Forum and Exposition, 2024, 2024. doi: 10.2514/6.2024-0914.

- A. Ray, “Smart Design Evolution with GenAI and 3D Printing,” presented at the 2024 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference, ISEC 2024, 2024. doi: 10.1109/ISEC61299.2024.10665095.

- D. Rukhovich, E. Dupont, D. Mallis, K. Cherenkova, A. Kacem, and D. Aouada, “CAD-Recode: Reverse Engineering CAD Code from Point Clouds,” Dec. 18, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2412.14042. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.14042.

- S. Wang et al., “CAD-GPT: Synthesising CAD Construction Sequence with Spatial Reasoning-Enhanced Multimodal LLMs,” Dec. 27, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2412.19663. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.19663.

- X. Wang, J. Zheng, Y. Hu, H. Zhu, Q. Yu, and Z. Zhou, “From 2D CAD Drawings to 3D Parametric Models: A Vision-Language Approach,” Dec. 17, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2412.11892. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.11892.

- Z. Wang et al., “LLaMA-Mesh: Unifying 3D Mesh Generation with Language Models,” Nov. 14, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2411.09595. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2411.09595.

- M. Wong, T. Rios, S. Menzel, and Y. S. Ong, “Prompt Evolutionary Design Optimization with Generative Shape and Vision-Language models,” presented at the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, CEC 2024—Proceedings, 2024. doi: 10.1109/CEC60901.2024.10611898.

- S. Wu et al., “CadVLM: Bridging Language and Vision in the Generation of Parametric CAD Sketches,” Sept. 26, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2409.17457. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2409.17457.

- L. Xia, C. Li, C. Zhang, S. Liu, and P. Zheng, “Leveraging error-assisted fine-tuning large language models for manufacturing excellence,” Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, vol. 88, p. 102728, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.rcim.2024.102728.

- J. Xu, C. Wang, Z. Zhao, W. Liu, Y. Ma, and S. Gao, “CAD-MLLM: Unifying Multimodality-Conditioned CAD Generation With MLLM,” Nov. 07, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2411.04954. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2411.04954.

- X. Xu, J. G. Lambourne, P. K. Jayaraman, Z. Wang, K. D. D. Willis, and Y. Furukawa, “BrepGen: A B-rep Generative Diffusion Model with Structured Latent Geometry,” Nov. 03, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2401.15563. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.15563.

- Z. Yuan, J. Shi, and Y. Huang, “OpenECAD: An efficient visual language model for editable 3D-CAD design,” Computers & Graphics, vol. 124, p. 104048, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.cag.2024.104048.

- S. Zarghami, H. Kouchaki, L. Yangand, and P. M. Rodriguez, “EXPLAINABLE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN GENERATIVE DESIGN FOR CONSTRUCTION,” presented at the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computing in Construction, 2024, pp. 556–563. doi: 10.35490/EC3.2024.277.

- H. Zhang, P. Chen, X. Xie, Z. Jiang, Z. Zhou, and L. Sun, “A Hybrid Prototype Method Combining Physical Models and Generative Artificial Intelligence to Support Creativity in Conceptual Design,” ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact., vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 1–34, Oct. 2024, doi: 10.1145/3689433.

- Z. Zhang, S. Sun, W. Wang, D. Cai, and J. Bian, “FlexCAD: Unified and Versatile Controllable CAD Generation with Fine-tuned Large Language Models,” Nov. 05, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2411.05823. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2411.05823.

- Z. Zhao et al., “ChatCAD+: Towards a Universal and Reliable Interactive CAD using LLMs,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 43, no. 11, pp. 3755–3766, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2024.3398350.

- Y. Zhu, G. Zhao, H. Liu, D. Sun, and Y. He, “Refining Bridge Engineering-based Construction Scheme Compliance Review with Advanced Large Language Model Integration,” in Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Big Data and Internet of Things, in BDIOT ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, pp. 297–305. doi: 10.1145/3697355.3697404.

- Q. Zou, Y. Wu, Z. Liu, W. Xu, and S. Gao, “Intelligent CAD 2.0,” Visual Informatics, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 1–12, 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.visinf.2024.10.001.

- M. F. Alam and F. Ahmed, “GenCAD: Image-Conditioned Computer-Aided Design Generation with Transformer-Based Contrastive Representation and Diffusion Priors,” Apr. 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2409.16294.

- Y. Ao, S. Li, and H. Duan, “Artificial Intelligence-Aided Design (AIAD) for Structures and Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Perspectives,” Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 2025, doi: 10.1007/s11831-025-10264-1.

- O. Bleisinger and M. Eigner, “AI Applications in Engineering New Technologies, New Opportunities?,” ZWF Zeitschrift fuer Wirtschaftlichen Fabrikbetrieb, vol. 120, no. s1, pp. 39–43, 2025, doi: 10.1515/zwf-2024-0173.

- D. Byrne, V. Hargaden, and N. Papakostas, “Application of generative AI technologies to engineering design,” presented at the Procedia Computer Science, 2025, pp. 147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2025.01.025.

- R. P. Cardoso Coelho, A. F. Carvalho Alves, T. M. Nogueira Pires, and F. M. Andrade Pires, “A composite Bayesian optimisation framework for material and structural design,” Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, vol. 434, p. 117516, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.cma.2024.117516.

- C. Chen et al., “CADCrafter: Generating Computer-Aided Design Models from Unconstrained Images,” Apr. 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2504.04753.

- A. Daareyni, A. Martikkala, H. Mokhtarian, and I. F. Ituarte, “Generative AI meets CAD: enhancing engineering design to manufacturing processes with large language models,” International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2025, doi: 10.1007/s00170-025-15830-2.

- A. C. Doris et al., “DesignQA: A Multimodal Benchmark for Evaluating Large Language Models’ Understanding of Engineering Documentation,” Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering, vol. 25, no. 2, 2025, doi: 10.1115/1.4067333.

- A. C. Doris, M. F. Alam, A. H. Nobari, and F. Ahmed, “CAD-Coder: An Open-Source Vision-Language Model for Computer-Aided Design Code Generation,” May 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2505.14646.

- Y. Etesam, H. Cheong, M. Ataei, and P. K. Jayaraman, “Deep Generative Model for Mechanical System Configuration Design,” presented at the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, pp. 16496–16504. doi: 10.1609/aaai.v39i16.33812.

- N. Heidari and A. Iosifidis, “Geometric Deep Learning for Computer-Aided Design: A Survey,” July 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2402.17695.

- B. T. Jones, F. Hähnlein, Z. Zhang, M. Ahmad, V. Kim, and A. Schulz, “A Solver-Aided Hierarchical Language for LLM-Driven CAD Design,” Feb. 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2502.09819.

- J. Kim, “On Transdisciplinary Research through Data Science and Engineering Education,” in Proceedings of the 2024 16th International Conference on Education Technology and Computers, in ICETC ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2025, pp. 523–528. doi: 10.1145/3702163.3702465.

- J. Li, W. Ma, X. Li, Y. Lou, G. Zhou, and X. Zhou, “CAD-Llama: Leveraging Large Language Models for Computer-Aided Design Parametric 3D Model Generation,” June 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2505.04481.

- K.-Y. Li, C.-K. Huang, Q.-W. Chen, H.-C. Zhang, and T.-T. Tang, “Generative AI and CAD automation for diverse and novel mechanical component designs under data constraints,” Discover Applied Sciences, vol. 7, no. 4, 2025, doi: 10.1007/s42452-025-06833-5.

- X. Li, Y. Sun, and Z. Sha, “LLM4CAD: Multimodal Large Language Models for Three-Dimensional Computer-Aided Design Generation,” Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering, vol. 25, no. 2, 2025, doi: 10.1115/1.4067085.

- X. Li and Z. Sha, “Image2CADSeq: Computer-Aided Design Sequence and Knowledge Inference from Product Images,” Jan. 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2501.04928.

- X. Liu, J. A. Erkoyuncu, J. Y. H. Fuh, W. F. Lu, and B. Li, “Knowledge extraction for additive manufacturing process via named entity recognition with LLMs,” Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, vol. 93, p. 102900, June 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.rcim.2024.102900.

- Z. Liu, Y. Chai, and J. Li, “Toward Automated Simulation Research Workflow through LLM Prompt Engineering Design,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 114–124, 2025, doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c01653.

- T. Mao, S. Yang, and B. Fu, “A Multi-Agent Framework for Multi-Source Manufacturing Knowledge Integration and Question Answering,” in Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, in WWW ’25. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2025, pp. 1687–1695. doi: 10.1145/3701716.3716884.

- W. P. McCarthy et al., “mrCAD: Multimodal Refinement of Computer-aided Designs,” Apr. 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2504.20294.

- A. Murphy et al., “An Analysis of Decoding Methods for LLM-based Agents for Faithful Multi-Hop Question Answering,” Mar. 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.23415.

- K. J. Offor, “Leveraging Generative AI to Simulate Stakeholder Involvement in the Engineering Design Process: A Case Study of MSc Team-Based Projects,” presented at the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, 2025. doi: 10.1109/EDUCON62633.2025.11016557.

- C. Picard et al., “From concept to manufacturing: evaluating vision-language models for engineering design,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 58, no. 9, 2025, doi: 10.1007/s10462-025-11290-y.

- U. L. Roncoroni, V. Crousse de Vallongue, and O. Centurion Bolaños, “Computational creativity issues in generative design and digital fabrication of complex 3D meshes,” International Journal of Architectural Computing, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 582–600, 2025, doi: 10.1177/14780771241260850.

- S. Wang et al., “CAD-GPT: Synthesising CAD Construction Sequence with Spatial Reasoning-Enhanced Multimodal LLMs,” AAAI, vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 7880–7888, Apr. 2025, doi: 10.1609/aaai.v39i8.32849.

- B. Yang, J. J. Dudley, and P. O. Kristensson, “Design Activity Simulation: Opportunities and Challenges in Using Multiple Communicative AI Agents to Tackle Design Problems,” in Proceedings of the 7th ACM Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, in CUI ’25. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2025. doi: 10.1145/3719160.3736609.

- C. Zhang et al., “A survey on potentials, pathways and challenges of large language models in new-generation intelligent manufacturing,” Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, vol. 92, p. 102883, Apr. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.rcim.2024.102883.

- L. Zhang, B. Le, N. Akhtar, S.-K. Lam, and T. Ngo, “Large Language Models for Computer-Aided Design: A Survey,” May 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2505.08137.

- J. Zhou and J. D. Camba, “The status, evolution, and future challenges of multimodal large language models (LLMs) in parametric CAD,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 282, 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127520.

References

- Wang, A.; Pruksachatkun, Y.; Nangia, N.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S. SuperGLUE: A Stickier Benchmark for General-Purpose Language Understanding Systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.00537. [Google Scholar]

- Chernyavskiy, A.; Ilvovsky, D.; Nakov, P. Transformers: “The End of History” for Natural Language Processing? In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Research Track; Oliver, N., Pérez-Cruz, F., Kramer, S., Read, J., Lozano, J.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedo, G.; Malartic, Q.; Hesslow, D.; Cojocaru, R.; Cappelli, A.; Alobeidli, H.; Pannier, B.; Almazrouei, E.; Launay, J. The RefinedWeb Dataset for Falcon LLM: Outperforming Curated Corpora with Web Data, and Web Data Only. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Soh, H. Large Language Models as Zero-Shot Human Models for Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; pp. 7961–7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, X.-Y.; Wang, C.D. FinGPT: Open-Source Financial Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.06031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Irsoy, O.; Lu, S.; Dabravolski, V.; Dredze, M.; Gehrmann, S.; Kambadur, P.; Rosenberg, D.; Mann, G. BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsi, S.; Zhao, D.; McDonald, J.; Li, B.; Michaleas, A.; Jones, M.; Bergeron, W.; Kepner, J.; Tiwari, D.; Gadepally, V. From Words to Watts: Benchmarking the Energy Costs of Large Language Model Inference. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, A.A.; Lin, L.; Nguyen, H.; Rao, V.; Sharma, T.; Wijayawardana, R. Reducing the Carbon Impact of Generative AI Inference (today and in 2035). In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Computer Systems, HotCarbon ’23, Boston, MA, USA, 9 July 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, J.; Harris, J.; Mozes, M.; Bradley, H.; Raileanu, R.; McHardy, R. Challenges and Applications of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makatura, L.; Foshey, M.; Wang, B.; Hähnlein, F.; Ma, P.; Deng, B.; Tjandrasuwita, M.; Spielberg, A.; Owens, C.E.; Chen, P.Y.; et al. Large Language Models for Design and Manufacturing. MIT Explor. Gener. AI 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Shu, P.; Tian, J.; Yang, T.; Xu, S.; et al. Large Language Models for Manufacturing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zeng, K.; Chang, F.; Ding, K. A survey on potentials, pathways and challenges of large language models in new-generation intelligent manufacturing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasik, D.; Buxton, W.; Ferguson, D. Ten CAD challenges. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2005, 25, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, T.; Johansson, J.; Elgh, F. Review of CAD-model capabilities and restrictions for multidisciplinary use. Comput.-Aided Des. Appl. 2018, 15, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, A.; Baaklini, G.Y.; Zagidulin, D.; Rauser, R.W. Challenges in integrating nondestructive evaluation and finite-element methods for realistic structural analysis. In Proceedings of the Nondestructive Evaluation of Aging Materials and Composites IV, SPIE, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 13 May 2000; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, K.; Hopkins, A.K.; Bau, D.; Viégas, F.; Pfister, H.; Wattenberg, M. Emergent World Representations: Exploring a Sequence Model Trained on a Synthetic Task. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2210.13382. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zheng, P. Leveraging error-assisted fine-tuning large language models for manufacturing excellence. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 88, 102728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y.; Gao, S. CAD-MLLM: Unifying Multimodality-Conditioned CAD Generation with MLLM. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.04954. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zuo, H.; Cai, Z.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Childs, P.; Wang, B. Toward Controllable Generative Design: A Conceptual Design Generation Approach Leveraging the Function–Behavior–Structure Ontology and Large Language Models. J. Mech. Des. 2024, 146, 121401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshan, A.; Huang, R.; Xu, X.; Jones, R.K.; Ritchie, D. ParSEL: Parameterized Shape Editing with Language. ACM Trans. Graph. 2024, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2201.11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, T.; Lanfermann, F.; Menzel, S. Large Language Model-assisted Surrogate Modelling for Engineering Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), Singapore, 25–27 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alrashedy, K.; Tambwekar, P.; Zaidi, Z.; Langwasser, M.; Xu, W.; Gombolay, M. Generating CAD Code with Vision-Language Models for 3D Designs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Sha, Z. LLM4CAD: Multi-Modal Large Language Models for 3D Computer-Aided Design Generation. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Design Theory and Methodology (DTM), Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 August 2024; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Volume 6, p. V006T06A015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, C.; Le, X.; Xu, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J. CAD-GPT: Synthesising CAD Construction Sequence with Spatial Reasoning-Enhanced Multimodal LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.19663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhou, R.; Ahmed, F. Multi-modal Machine Learning in Engineering Design: A Review and Future Directions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Obukhov, A.; Wegner, J.D.; Schindler, K. Point2CAD: Reverse Engineering CAD Models from 3D Point Clouds. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.04962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Pan, S.; Cohen-Or, D.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H. Split-and-Fit: Learning B-Reps via Structure-Aware Voronoi Partitioning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.05261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Nakhjiri, A.T.; Ghadiri, M. Different applications of machine learning approaches in materials science and engineering: Comprehensive review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 135, 108783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frome, A.; Corrado, G.S.; Shlens, J.; Bengio, S.; Dean, J.; Ranzato, M.A.; Mikolov, T. DeViSE: A Deep Visual-Semantic Embedding Model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2013, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.-H.H.; Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.-P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Learning Factorized Multimodal Representations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1806.06176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Akata, Z.; Schiele, B.; Lee, H. Learning Deep Representations of Fine-grained Visual Descriptions. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.05395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracewell, R.; Wallace, K.; Moss, M.; Knott, D. Capturing design rationale. Comput.-Aided Des. 2009, 41, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, K.; Hajda, M.; Borgman, J. Challenges with product data exchange in product development networks. In Proceedings of the 10th International Design Conference, DESIGN 2008, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 19–22 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Mac, G.; Tsoutsos, N.G.; Gupta, N.; Karri, R. Computer aided design (CAD) model search and retrieval using frequency domain file conversion. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayathullah, S.; Buddala, R. Review of machine learning applications in additive manufacturing. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| A: LLM Technologies | “large language model” OR “LLM” OR “generative AI” OR “foundation model” |

| B: Engineering Domain | “mechanical engineering” OR “engineering design” OR “product design” |

| C: Specific Applications & Tools | “computer-aided design” OR “CAD” OR “generative design” OR “finite element” OR “FEA” OR “simulation” OR “CAx” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baker, C.; Rafferty, K.; Price, M. Large Language Models in Mechanical Engineering: A Scoping Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9120305

Baker C, Rafferty K, Price M. Large Language Models in Mechanical Engineering: A Scoping Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2025; 9(12):305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9120305

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaker, Christopher, Karen Rafferty, and Mark Price. 2025. "Large Language Models in Mechanical Engineering: A Scoping Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 9, no. 12: 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9120305

APA StyleBaker, C., Rafferty, K., & Price, M. (2025). Large Language Models in Mechanical Engineering: A Scoping Review of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 9(12), 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9120305