Abstract

Background: Coinfection with bacteria, fungi, and respiratory viruses has been described as a factor associated with more severe clinical outcomes in children with COVID-19. Such coinfections in children with COVID-19 have been reported to increase morbidity and mortality. Objectives: To identify the type and proportion of coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 and bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses, and investigate the severity of COVID-19 in children. Methods: For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched ProQuest, Medline, Embase, PubMed, CINAHL, Wiley online library, Scopus, and Nature through the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for studies on the incidence of COVID-19 in children with bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory coinfections, published from 1 December 2019 to 1 October 2022, with English language restriction. Results: Of the 169 papers that were identified, 130 articles were included in the systematic review (57 cohort, 52 case report, and 21 case series studies) and 34 articles (23 cohort, eight case series, and three case report studies) were included in the meta-analysis. Of the 17,588 COVID-19 children who were tested for co-pathogens, bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections were reported (n = 1633, 9.3%). The median patient age ranged from 1.4 months to 144 months across studies. There was an increased male predominance in pediatric COVID-19 patients diagnosed with bacterial, fungal, and/or viral coinfections in most of the studies (male gender: n = 204, 59.1% compared to female gender: n = 141, 40.9%). The majority of the cases belonged to White (Caucasian) (n = 441, 53.3%), Asian (n = 205, 24.8%), Indian (n = 71, 8.6%), and Black (n = 51, 6.2%) ethnicities. The overall pooled proportions of children with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 who had bacterial, fungal, and respiratory viral coinfections were 4.73% (95% CI 3.86 to 5.60, n = 445, 34 studies, I2 85%, p < 0.01), 0.98% (95% CI 0.13 to 1.83, n = 17, six studies, I2 49%, p < 0.08), and 5.41% (95% CI 4.48 to 6.34, n = 441, 32 studies, I2 87%, p < 0.01), respectively. Children with COVID-19 in the ICU had higher coinfections compared to ICU and non-ICU patients, as follows: respiratory viral (6.61%, 95% CI 5.06–8.17, I2 = 0% versus 5.31%, 95% CI 4.31–6.30, I2 = 88%) and fungal (1.72%, 95% CI 0.45–2.99, I2 = 0% versus 0.62%, 95% CI 0.00–1.55, I2 = 54%); however, COVID-19 children admitted to the ICU had a lower bacterial coinfection compared to the COVID-19 children in the ICU and non-ICU group (3.02%, 95% CI 1.70–4.34, I2 = 0% versus 4.91%, 95% CI 3.97–5.84, I2 = 87%). The most common identified virus and bacterium in children with COVID-19 were RSV (n = 342, 31.4%) and Mycoplasma pneumonia (n = 120, 23.1%). Conclusion: Children with COVID-19 seem to have distinctly lower rates of bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections than adults. RSV and Mycoplasma pneumonia were the most common identified virus and bacterium in children infected with SARS-CoV-2. Knowledge of bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral confections has potential diagnostic and treatment implications in COVID-19 children.

Keywords:

bacterial; children; co-infection; coinfection; concurrent; COVID-19; fungal; meta-analysis; pediatric; SARS-CoV-2; viral; systematic review 1. Introduction

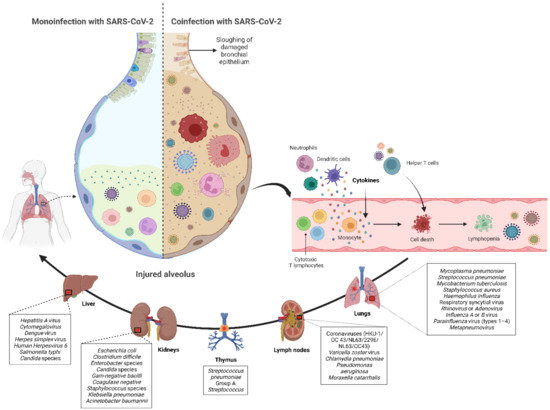

Although most cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in pediatric populations are mild or asymptomatic [1], the clinical spectrum of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children ranges from asymptomatic to life-threatening [2,3]. Similar to adults, coinfection with bacteria, fungi, and respiratory viruses has been described as a factor associated with more severe clinical outcomes in children with COVID-19 [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Such coinfections have been reported to increase morbidity and mortality, therefore, knowledge of bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral confections has potential diagnostic and treatment implications in children infected with SARS-CoV-2. Many studies have shown that COVID-19 children may develop severe diseases, requiring intensive care admission and/or mechanical ventilation because patients rapidly develop acute respiratory distress syndrome and sepsis, leading to death from multiple organ failure [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. SARS-CoV-2 is hypothesized to weaken the bodies of children to bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections [24], yet the mechanism of coinfection has not been fully established, but represents a threat to the respiratory epithelium favoring bacteremia, fungaemia, and/or viraemia (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Monoinfection with SARS-CoV-2 results in less severe form of COVID-19 and better prognosis. In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 coinfection with bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses may intensify the severity of COVID-19 and increase the expression of macrophages, T and B defensive cells that may cause the elevation of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 in the infected organs, leading to a hyperinflammatory response by recruiting immune cells.

There is a lack of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the type and frequency of coinfection by bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral infections and associated clinical outcomes among COVID-19 children. We aimed to identify the type and proportion of coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 and bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses, and investigate the severity of COVID-19 in these patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) in conducting this systematic review and meta-analysis [25]. The following electronic databases were searched: PROQUEST, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PUBMED, CINAHL, WILEY ONLINE LIBRARY, SCOPUS, and NATURE with Full Text. We used the following keywords: (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “Severe acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2” OR “Coronavirus Disease 2019” OR “2019 novel coronavirus”) AND (“children” OR “child” OR “paediatric” OR “pediatric” OR “infant” OR “toddler” OR “adolescent” OR “newborn”) AND (“coinfection” OR “co-infection” OR “cocirculation” OR “co-circulation” OR “coinfected” OR “co-infected” OR “co-circulated” OR “mixed” OR “concurrent” OR “concomitant”). The search was limited to papers published in English between 1 December 2019 and 1 October 2022. Based on the title and abstract of each selected article, we selected those discussing and reporting the occurrence of bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfection in children with COVID-19.

2.2. Inclusion–Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) published case reports, case series, and cohort studies that focused on children infected with SARS-CoV-2 and bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses; (2) studies of experimental or observational design reporting the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric patients with other co-pathogens; (3) language restricted to English. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) editorials, commentaries, case and animal studies, reviews, and meta-analyses; (2) studies that did not report data on COVID-19 in coinfected patients; (3) studies that never reported details on identified coinfected cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection; (4) studies that reported coinfection in adult COVID-19 patients; (5) studies that reported coinfection in patients with negative SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests; (6) duplicate publications.

2.3. Data Extraction

Six authors (Saad Alhumaid, Muneera Alabdulqader, Nourah Al Dossary, Zainab Al Alawi, Abdulrahman A. Alnaim, and Koblan M. Al mutared) critically reviewed all of the studies retrieved and selected those judged to be the most relevant. Data were carefully extracted from the relevant research studies independently. Articles were categorized as case report, case series, or cohort studies. The following data were extracted from selected studies: authors; publication year; study location; study design and setting; number of SARS-CoV-2 children tested for co-pathogens; number of coinfected children; age; proportion of male children; patient ethnicity; number of children with bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections; total organisms identified; antimicrobials prescribed; laboratory techniques for co-pathogen detection; number of children admitted to intensive care unit (ICU), placed on mechanical ventilation, and/or suffered acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); assessment of study risk of bias; and final treatment outcome (survived or died). These data are noted in Table 1.

2.4. Quality Assessment

For many selected cohort studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was used to assess the risk of bias, a tool which measures quality in the three parameters of selection, comparability, and exposure/outcome, and allocates a maximum of 4, 2, and 3 points, respectively [26]. High-quality studies are scored greater than 7 on this scale, and moderate-quality studies between 5 and 7 [26]. Otherwise, quality assessment of the selected case report and case series studies was undertaken based on the modified NOS [27]. Items related to the comparability and adjustment were removed from the NOS, and items which focused on selection and representativeness of cases, and the ascertainment of outcomes and exposure, were kept [27]. Modified NOS consists of five items, each of which requires a yes or no response to indicate whether bias is likely, and these items were applied to single-arm studies [27]. Quality of the study was considered good if all five criteria were met, moderate when four were met, and poor when three or less were met. Quality assessment was performed by six authors (Khalid Al Noaim, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi, Suha Jafar Albahrani, Abdulaziz A. Alahmari, Sarah Mahmoud Al HajjiMohammed, and Yameen Ali Almatawah) independently, with any disagreement to be resolved by consensus.

2.5. Data Analysis

The proportion of confirmed COVID-19 children with bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfection were examined. This proportion was further classified based on initial presentation or during the course of the illness. A random effects DerSimonian–Laird model was used, which produces wider confidence intervals (Cis) than a fixed effect model [28]. Results are illustrated using a forest plot. The Cochran’s chi-square (χ2) and the I2 statistic provided the tools for examining statistical heterogeneity [29]. An I2 value of >50% suggested significant heterogeneity [30]. To lower the source of heterogeneity, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on children’s admission to the ICU. To estimate publication bias, funnel plots and Egger’s correlation were used, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All p-values were based on two-sided tests and significance was set at a p-value less than 0.05. R version 4.1.0 with the packages finalfit and forestplot was used for all statistical analyses. Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com (agreement no. NX24IV1VNB) (accessed on 14 October 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Quality

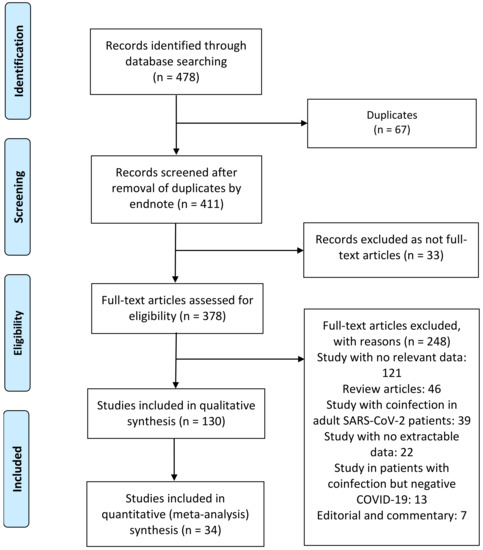

A total of 130 publications were identified (Figure 2). After scanning titles and abstracts, 67 duplicate articles were discarded. Another 33 irrelevant articles were excluded based on the titles and abstracts. The full texts of the 378 remaining articles were reviewed, and 248 irrelevant articles were excluded. As a result, we identified 130 studies that met our inclusion criteria and reported SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric patients with bacterial, fungal, and viral coinfection [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140]. The detailed characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Among these, two articles were preprint versions [64,89]. There were 57 cohort [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,17,31,32,34,35,36,37,39,41,42,44,49,53,58,66,69,71,73,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,89,90,95,98,99,102,105,108,109,115,116,118,119,123,125,127,129,131,133,134,137,138,139], 52 case report [13,14,15,16,18,19,21,22,23,33,38,40,43,45,46,48,50,51,52,55,56,59,64,65,67,68,70,72,74,75,76,77,86,87,91,93,94,97,104,106,107,110,111,113,114,121,122,124,126,128,130,140], and 21 case series [20,47,54,57,60,61,62,63,85,88,92,96,100,101,103,112,117,120,132,135,136] studies. These studies were conducted in the United States (n = 23), China (n = 21), India (n = 9), Italy (n = 7), Iran (n = 7), France (n = 6), Turkey (n = 6), Spain (n = 5), Mexico (n = 4), Brazil (n = 4), Indonesia (n = 4), South Africa (n = 3), Switzerland (n = 3), Poland (n = 3), United Kingdom (n = 3), Argentina (n = 2), Saudi Arabia (n = 2), United Arab Emirates (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 1), Thailand (n = 1), Bulgaria (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Lebanon (n = 1), Botswana (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Russia (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Bangladesh (n = 1), Japan (n = 1), Greece (n = 1), and Canada (n = 1). Only four studies were conducted within multiple countries (n = 4) [53,109,118,127]. The majority of the studies were single-center [4,6,11,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,21,22,23,32,33,34,35,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,120,121,122,124,126,128,130,132,133,134,138,139,140] and only 33 studies were multicenter [5,7,8,9,10,17,20,31,36,37,42,47,53,54,58,63,71,84,95,96,108,109,110,118,119,123,125,127,129,131,135,136,137]. In some studies, concurrent infection of SARS-CoV-2 with other bacterial, fungal, and/or viral pathogens was investigated in pediatric and adult patients as the population of interest (19/130, 14.6%) [10,17,31,37,47,54,57,62,71,79,82,90,96,102,108,112,118,123,139]. The majority (n = 128) of the studies included any hospitalized patient, except for two studies that investigated potential of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in a cluster and genomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in a family [47,62], and two studies included only critically ill COVID-19 patients [9,18]. Eleven, four, and one studies exclusively reported on respiratory viral [10,18,31,35,61,71,73,89,101,125,140], bacterial [11,96,100,112], and fungal [90] coinfections, respectively; the remaining 114 studies reported on bacterial, fungal, and respiratory viral coinfections [4,5,6,7,8,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,91,92,93,94,95,97,98,99,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139]. Few studies investigated the existence of COVID-19 with influenza virus type A and B only [31,101,140], Mycobacterium tuberculosis only [11,96,112], respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) only [35,61], Rhinovirus only [10,125], pneumovirus only [18], herpes simplex virus only [71], human coronavirus OC43 only [73], adenovirus only [89], Mycoplasma pneumonia only [100], and Candida species only [90]. Laboratory techniques for co-pathogen detection within studies included 52 that used real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests for multiple respiratory viruses [9,10,17,18,31,34,37,41,43,44,46,47,48,49,61,65,66,68,69,71,73,76,79,80,81,82,83,89,91,92,95,99,101,102,110,113,115,116,117,119,123,125,127,129,130,131,132,135,136,137,138,139], 23 that used antibody tests (immunoglobulins M and/or G) [5,8,22,23,45,52,54,56,70,72,77,78,81,85,98,100,104,108,111,120,122,133,140], 42 that used cultures (blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, tracheal, nasal discharge, pharyngeal swabs, wound, respiratory secretions, bronchoalveolar lavage, alveolar fluid, sputum, and pleural fluid) [5,6,11,12,13,15,16,20,21,23,38,40,42,50,51,53,55,60,63,64,74,75,84,85,87,88,90,93,96,97,105,106,107,109,112,114,118,121,124,126,128,134], 29 that used two or more laboratory methods (RT-PCR, antibody tests, and/or culture) [4,5,6,7,8,12,20,23,36,39,42,50,52,53,57,58,63,72,77,78,81,84,85,98,105,109,124,126,133], and two that did not specify their testing method [32,33]. Among the 130 included studies, 57 cohort studies were assessed using the NOS: 52 studies were found to be moderate-quality studies (i.e., NOS scores were between 5 and 7) and five studies demonstrated a relatively high quality (i.e., NOS scores > 7). All case reports and case series studies were assessed for bias using the modified NOS. Forty-nine studies were deemed to have high methodological quality, and three exhibited moderate methodological quality; Table 1.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of literature search and data extraction from studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies with evidence on SARS-CoV-2 and bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections in children (n = 130), 2020–2022.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies with evidence on SARS-CoV-2 and bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections in children (n = 130), 2020–2022.

| Author, Year, Study Location | Study Design, Setting | Number of SARS-CoV-2 Patients Tested for Co-Pathogens, n | Coinfected Patients, n | Age (Months) a | Male, n (%) AND Ethnicity, n b | Bacterial Coinfection, n | Fungal Coinfection, n | Respiratory Viral Coinfection, n | Total Organisms, n | Antimicrobials Used, n | Laboratory Techniques for Co-Pathogen Detection | Admitted to ICU, n | Mechanical Ventilation, n | ARDS, n | Assessment of Study Risk of Bias (Tool Used, Finding) and Treatment Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al. 2022 [31], India | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 770 | 4 | 12, 18, 96, and 72 | 3 (75) AND 4 Indian | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 Influenza A virus 3 Influenza B virus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 4 survived |

| Al Mansoori et al. 2021 [32], United Arab Emirates | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 17 | 7 | Median (IQR), 84 (0–192) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 Rhinovirus 2 Group A Streptococcus 1 Enterovirus 1 Adenovirus | 7 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Not reported (Group A Streptococcus) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Allen-Manzur et al. 2020 [33], Mexico | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 (0) AND 1 Hispanic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium bovis | 1 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Not reported (Mycobacterium bovis) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, moderate) 1 survived |

| Alrayes et al. 2022 [34], United States | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 13 | 13 | Age group 0–2: 270 (71.3%) patients (RSV coinfection) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 0 | 0 | 15 | 13 RSV 1 Rhinovirus 1 Adenovirus | 13 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 13 survived |

| Alvares 2021 [35], Brazil | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 32 | 6 | Median (IQR), 6 | 2 (33.3) AND 6 Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 RSV | 1 Not reported | Chemiluminescence for RSV | 1 | 1 | 1 Not reported | (NOS, 6) 6 survived |

| Anderson et al. 2021 [4], United States | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 29 | 10 | Age group 168 (42–198): 10 (34.4%) patients Age group 192 (168–204): 9 (31%) patients Age group 102 (72–168): 10 (34.4%) patients | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 5 | 0 | 6 | 2 Staphylococcus aureus 2 Escherichia coli 1 Salmonella enteritis 1 Enterovirus 1 Adenovirus 2 Rhinovirus 1 Parainfluenza virus 1 EBV | 10 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c PCR assays (bacteria) | 7 | 2 | 3 | (NOS, 8) 7 survived 3 died |

| Andina-Martinez et al. 2022 [36], Spain | Prospective cohort, multicenter | 9 | 2 | 1.3 and 1.8 | 1 (50) AND 2 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 Bordetella pertussis 1 Metapneumovirus | 2 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c PCR assays (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis) | 1 | 1 | 2 Not reported | (NOS, 7) 2 survived |

| Aragón-Nogales et al. 2022 [12], Mexico | Prospective cohort, single-center | 181 | 2 | 12 and 24 | 0 (0) AND 2 Hispanic | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 EBV | 1 Cefotaxime 1 Ceftriaxone | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood culture (bacteria) | 2 | 2 | 2 | (NOS, 7) 2 died |

| Arguni et al. 2022 [37], Indonesia | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 125 | 59 | Two patients: <12 months to <60 months Six patients: <60 months to <216 months | Gender (not reported) AND 8 Asian | 0 | 0 | 59 | 32 Influenza A virus 10 Adenovirus 16 Influenza B virus 1 Metapneumovirus | 59 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 59 Not reported | 59 Not reported | 59 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Arslan et al. 2021 [38], Turkey | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 MSSA | 1 Clindamycin 1 Ceftriaxone | Blood culture (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Aykac et al. 2021 [39], Turkey | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 115 | 37 | Median (IQR), 48 (12–132) | Gender (not reported) AND 37 White (Caucasian) | 37 | 0 | 4 | 37 Streptococcus pneumoniae 2 Bocavirus 1 Rhinovirus 1 Parechovirus | 7 Ceftriaxone 7 Azithromycin 7 Ampicillin/sulbactam | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c PCR assays (Streptococcus pneumoniae) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Ayoubzadeh et al. 2021 [40], Canada | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 168 | 1 (100) AND 1 Pakistani | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Gram-negative bacilli 1 Salmonella Typhi | 1 Meropenem 1 Ampicillin 1 Amoxicillin | Blood culture (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Berksoy et al. 2021 [41], Turkey | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 128 | 21 | 1 patient: 5 Other patients: not reported | Gender (not reported) AND 21 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 23 | 9 Rhinovirus 5 Metapneumovirus 4 RSV 3 Adenovirus 2 Bocavirus | 21 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 21 Not reported | 0 | 21 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Blázquez-Gamero et al. 2021 [42], Spain | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 27 | 2 | 1 and 3 | Gender (not reported) AND 27 White (Caucasian) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 Streptococcus mitis 1 Escherichia coli 1 Enterobacter cloacae | 2 Ampicillin 1 Gentamycin 1 3rd -generation cephalosporin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood culture (bacteria) Urine culture (bacteria) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 2 survived |

| Borocco et al. 2021 [43], France | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 156 | 0 (0) AND 1 Arab | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 EBV | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Brothers et al. 2021 [13], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 144 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 MSSA 1 Candida glabrata | 1 Clindamycin 1 Vancomycin 1 Cefepime 1 Fluconazole 1 Micafungin | Tracheal culture (bacteria) Urine culture (urine) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Cason et al. 2022 [44], Italy | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 64 | 17 | Age group <24 was the most frequent) | Gender (not reported) AND 17 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 19 | 1 Other coronaviruses (229E, NL63, and OC43) 12 Rhinovirus 4 Bocavirus 2 Adenovirus | 17 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 17 Not reported | 17 Not reported | 17 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Chacón-Cruz et al. 2022 [14], Mexico | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 84 | 1 (100) AND 1 Hispanic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Neisseria meningitidis | 1 Amoxicillin 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Doxycycline | PCR assays (Neisseria meningitidis) | 1 Not reported | 1 Not reported | 1 Not reported | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Chen et al. 2020 [45], China | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 144 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycoplasma pneumonia 1 Chlamydia pneumoniae | 1 Mezlocillin 1 Ceftizoxime 1 Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Serum antibody tests (IgM, IgG) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Choudhary et al. 2022 [5], United States | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 947 | 235 | Age group <60: 101 (33.9%) patients (viral coinfection) Age group <60: 50 (16.8%) patients (bacterial coinfection) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 123 | 7 | 113 | 75 RSV 113 Viral 123 Bacterial 7 Fungal | 123 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood culture (bacteria) Serum antibody tests (IgM, IgG) | 33 | 14 | 235 Not reported | (NOS, 8) 233 survived 2 died |

| Ciuca et al. 2021 [46], Italy | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 72 | 1 (100) AND 1 Black | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Parvovirus B19 | 1 Antibiotics | PCR assays (Parvovirus B19) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Danis et al. 2020 [47], France | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 12 | 1 | 108 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 Influenza A virus 1 Rhinovirus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Danley and Kent 2020 [48], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Adenovirus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| DeBiasi et al. 2020 [49], United States | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 63 | 4 | Median, 115.2 | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 Rhinovirus 2 RSV 1 Other coronaviruses (229E, NL63, and OC43) | 4 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 4 Not reported | 4 Not reported | 4 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Demirkan and Yavuz 2021 [50], Turkey | Retrospective case reports, single-center | 2 | 2 | 84 and 156 | 0 (0) AND 2 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 Fungal bezoars | 1 Meropenem 2 Fluconazole | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood culture (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 2 survived |

| Dhanawade et al. 2021 [51], India | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 48 | 0 (0) AND 1 Indian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Antibiotics 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | CSF culture (bacteria) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Di Nora et al. 2022 [52], Italy | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 24 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Human Herpesvirus 6 | 1 Acyclovir 1 Ceftriaxone | CSF PCR assays (viruses) Serum antibody test (IgM) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Dikranian et al. 2022 [53], Multi-country | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 922 | 31 | Age group ≤6: 136/820 (16.6%) Age group >120 to 180: 182/820 (22.2%) Age group >180 to 216: 189/820 (23%) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 0 | 0 | 30 | 10 Rhinovirus 5 RSV 2 Adenovirus 1 Coronavirus NL63 1 Parainfluenza-2 1 Parainfluenza-3 1 Parainfluenza-4 1 Metapneumovirus 8 Unspecified viruses | 31 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood culture (bacteria) Sputum (bacteria) | 22 | 31 Not reported | 31 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Diorio et al. 2020 [6], United States | Prospective cohort, single-center | 24 | 7 | Median (IQR), 60 (30–192) | 5 (71.4) AND 3 White (Caucasian) 1 Hispanic 3 Black | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 Parainfluenza 3 1 Parainfluenza 4 2 Escherichia coli 1 Enterovirus 1 Adenovirus 1 Rhinovirus 1 MRSA 1 Salmonella typhi | 7 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood culture (bacteria) Urine (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 8) 6 survived 1 died |

| Dong et al. 2020 [54], China | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 11 | 1 | 28 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Cytomegalovirus | 0 | Serum antibody test (IgM) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Essajee et al. 2020 [55], South Africa | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 31 | 0 (0) AND 1 Black | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Antibiotics 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | Blood culture (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Ferdous et al. 2021 [56], Bangladesh | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 96 | 0 (0) AND 1 Bangladeshi | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 1 Antibiotics | Dengue NS1 antigen | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Freij et al. 2020 [15], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 60 | 0 (0) AND 1 Black | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis 1 Group A Streptococcus | 1 Amoxicillin 1 Azithromycin | CSF culture (bacteria) | 1 | 1 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Frost et al. 2022 [57], United States | Retrospective case series, single-center | 7 | 6 | Median (IQR), 16 (7–30) | 5 (83.3) AND 5 Hispanic | 14 | 0 | 5 | 1 Adenovirus 1 Metapneumovirus 2 Rhinovirus 1 Enterovirus 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae 5 Haemophilus influenza 3 Moraxella catarrhalis 2 Staphylococcus aureus | 7 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c PCR assays (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 6 survived |

| Garazzino et al. 2021 [7], Italy | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 515 | 69 | Median (IQR), 87 (17–149) | Gender (not reported) AND 69 White (Caucasian) | 32 | 0 | 45 | 45 Unspecified viruses 32 Unspecified bacteria | 69 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c PCR assays (bacteria) | 3 | 3 | 2 | (NOS, 7) 67 survived 2 died |

| Garazzino et al. 2020 [58], Italy | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 168 | 10 | Median (IQR), 28 (4–115) | Gender (not reported) AND 10 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 10 | 3 RSV 3 Rhinovirus 2 EBV 1 Influenza A virus 1 Other coronaviruses (229E, NL63, and OC43) 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae | 10 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c PCR assays (bacteria) | 2 | 2 | 2 | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Goussard et al. 2020 [59], South Africa | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 29 | 1 (100)AND 1 Black | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Rifampicin-sensitive Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Antibiotics 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide 1 Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | PCR assay for gastric aspirate (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Guy et al. 2022 [60], United States | Retrospective case series, single-center | 6 | 6 | Median (IQR), 144 (42–168) | 5 (83.3) AND 5 Black 1 White (Caucasian) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 Streptococcus intermedius 2 Prevotella species 2 Streptococcus constellatus | 4 Ceftriaxone 3 Clindamycin 2 Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1 Penicillin 2 Metronidazole 1 Ampicillin/sulbactam 2 Vancomycin 1 Cefdinir | Nasal discharge (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 6 survived |

| Halabi et al. 2022 [61], United States | Retrospective and prospective case series, single-center | 18 | 18 | Median (IQR), 6 (2–36) | 11 (61.1) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 0 | 0 | 22 | 18 RSV 3 Rhinovirus 1 Parainfluenza virus | 18 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 9 | 2 | 2 | (Modified NOS, high) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Hamzavi et al. 2020 [16], Iran | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 168 | 1 (100) AND 1 Persian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Staphylococcus aureus | 1 Vancomycin 1 Meropenem | Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Hare et al. 2021 [62], United Kingdom | Retrospective case series, single-center | 7 | 1 | 22 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Rhinovirus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Hashemi et al. 2021 (17], Iran | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 105 | 5 | Age group 0 to 168: 5 (4.8%) patients (viral coinfection) | 4 (80) AND 5 Persian | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 Metapneumovirus 1 Bocavirus 1 Influenza A virus | 5 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 5 | 5 | 5 | (NOS, 7) 5 died |

| Hashemi et al. 2021 [18], Iran | Retrospective case reports, single-center | 3 | 3 | 13, 72, and 72 | 2 (66.6) AND 3 Persian | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 Metapneumovirus | 3 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 3 | 3 | 3 | (Modified NOS, high) 3 died |

| Hassoun et al. 2021 [63], United States | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 8 | 6 | Median (IQR), 1.4 (0.5–1.6) | 5 (83.3) AND 2 Black 2 White (Caucasian) 1 Hispanic 1 Indian | 1 | 0 | 6 | 5 RSV 1 Rhinovirus 1 Escherichia coli | 6 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Urine (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 6 survived |

| He et al. 2020 [8], China | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 15 | 4 | Median (IQR), 72 (36–84) | 3 (75) AND 4 Asian | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 Unspecified bacteria 2 Unspecified fungi | 4 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Sputum (bacteria) G assay and GM assay (fungi) Serum antibody test (IgM) | 2 | 2 | 2 | (NOS, 7) 2 survived 2 died |

| Hertzberg et al. 2020 [64], United States | Retrospective case reports, single-center | 3 | 3 | 2, 24 and 60 | 2 (66.7) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 Rhinovirus 1 Bordetella pertussis | 1 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood (culture) | 1 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, moderate) 3 survived |

| Jarmoliński et al. 2021 [65], Poland | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 108 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 Metapneumovirus 1 RSV | 1 Piperacillin/tazobactam 1 Amikacin 1 Azithromycin 1 Cefepime 1 Micafungin 1 Acyclovir | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Jiang et al. 2020 [66], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 161 | 2 | 80 and 42 | 0 (0) AND 2 Asian | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 RSV 2 Metapneumovirus 1 Mycoplasma pneumonia | 2 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 0 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 2 survived |

| Jose et al. 2021 [67], Mexico | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 84 | 1 (100) AND 1 Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 1 Amoxicillin 1 Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 1 Clindamycin 1 3rd -generation cephalosporin 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Acyclovir | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c DENV RTqPCR (dengue) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Kakuya et al. 2020 [68], Japan | Retrospective case report, single-center | 3 | 2 | 132 and 60 | 2 (100) AND 2 Asian | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 Influenza A virus 1 Metapneumovirus | 1 Ceftriaxone | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 2 survived |

| Kanthimathinathan et al. 2021 [9], United Kingdom | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 73 | 17 | Median (IQR), 120 (12–156) | Gender (not reported) AND 6 White (Caucasian) 5 Asian 4 Black | 6 | 4 | 14 | 3 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 2 Klebsiella pneumoniae 1 Acinetobacter baumannii 2 Adenovirus 2 Influenza 2 Parainfluenza 2 Rhinovirus 1 Metapneumovirus 1 RSV 4 Cytomegalovirus 4 Unspecified fungi | 3 Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1 Azithromycin 2 Clarithromycin 1 Piperacillin/tazobactam 1 Gentamicin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 17 | 7 | 10 | (NOS, 8) 16 survived 1 died |

| Karaaslan et al. 2021 [69], Turkey | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 93 | 7 | Mean ± SD, 10.99 ± 6.44 | 5 (71.4) AND 7 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 7 | 2 Rhinovirus 2 Coronavirus NL63 1 Adenovirus 1 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 1 Rhinovirus 1 Adenovirus | 7 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 7 survived |

| Karimi et al. 2020 [70], Iran | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 144 | 1 (100) AND 1 Persian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Varicella zoster virus | 1 Azithromycin | Serum antibody tests (IgM and IgG) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Katz et al. 2022 [71], United States | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 16 | 2 | 72 and 120 | 1 (50) AND 2 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 Herpes simplex virus | 2 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 2 Not reported | 2 Not reported | 2 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Kazi et al. 2021 [72], India | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 9 | 0 (0) AND 1 Indian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Vancomycin 1 Doxycycline | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c DENV RTqPCR (dengue) IgM antibody test from CSF (dengue) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Keshavarz Valian et al. 2022 [73], Iran | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 25 | 2 | Mean ± SD, 58.8 ± 51.6 | Gender (not reported) AND 2 Persian | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 Human coronavirus OC43 | 2 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 2 Not reported | 2 Not reported | 2 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Khataniar et al. 2022 [74], India | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 168 | 1 (100) AND 1 Indian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Meropenem 1 Vancomycin 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Amikacin 1 Levofloxacin 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | CSF culture (bacteria) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Lambrou et al. 2022 [75], Greece | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 36 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Escherichia hermannii | 1 Piperacillin/tazobactam 1 Amikacin 1 Teicoplanin 1 Meropenem 1 Micafungin | Blood (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Le Glass et al. 2021 [10], France | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 2159 | 58 | Age group <180: 25 (43.1%) patients (rhinovirus coinfection) | 33 (56.9) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 58 Not reported | 58 Not reported | 58 | 58 Rhinovirus | 93 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 58 Not reported | 58 Not reported | 58 Not reported | (NOS, 6) 57 survived 1 died |

| Le Roux et al. 2020 [76], France | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 Varicella zoster virus 1 Rotavirus | 1 Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1 Azithromycin 1 Acyclovir | PCR | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Leclercq et al. 2021 [77], Switzerland | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 96 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 EBV 1 Group A Streptococcus | 1 Amoxicillin 1 Cephalosporin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Serum antibody tests (IgM, IgG) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Lee et al. 2022 [78], United States | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 1625 | 92 | Not reported | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 0 | 0 | 111 | 56 RSV 38 Influenza A virus 11 Rhinovirus 2 Influenza B virus 2 Adenovirus 2 Parainfluenza virus | Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Serum antibody tests (IgM, IgG) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Leuzinger et al. 2020 [79], Switzerland | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 16 | 4 | Age group ≤60: 2 (14.3%) patients (viral coinfection) Age group ≤192: 2 (14.3%) patients (viral coinfection) | Gender (not reported) AND 4 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 Rhinovirus 2 RSV 2 Parainfluenza virus (types 1–4) | 4 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 4 Not reported | 4 Not reported | 4 Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Li et al. 2020 [80], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 40 | 15 | Mean ± SD, 61 ± 56 | Gender (not reported) AND 15 Asian | 14 | 0 | 4 | 13 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 3 Influenza A or B virus 1 Adenovirus 1 Streptococcus pneumonia | 13 Azithromycin 1 Meropenem 1 Piperacillin/tazobactam | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 15 survived |

| Li et al. 2021 [81], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 81 | 27 | Mean ± SD, 76.5 ± 9.6 | 15 (55.6) AND 27 Asian | 24 | 0 | 6 | 20 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 1 Influenza A virus 2 Influenza B virus 1 RSV 1 Adenovirus 1 Parainfluenza virus 2 3 Moraxella catarrhalis 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae | 27 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Sputum (bacteria) Serum antibody tests (IgM, IgG) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 27 survived |

| Lin et al. 2020 [82], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 92 | 1 | 36 | 0 (0) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Metapneumovirus | 1 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 Not reported | 1 Not reported | 1 Not reported | (Modified NOS, high) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Ma et al. 2020 [83], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 45 | 4 | 4 Not reported | Gender (not reported) AND 4 Asian | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 Mycoplasma pneumonia 2 Parainfluenza virus 1 Adenovirus | 4 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 3 | 3 | 3 | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Mania et al. 2022 [84], Poland | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 1283 | 135 | Median (IQR), 72 (12–156) | Gender (not reported) AND 135 White (Caucasian) | 15 | 0 | 37 | 11 Streptococcus pneumoniae 2 Influenza A virus 2 Escherichia coli 1 Adenovirus 1 Rhinovirus 1 Bocavirus 1 RSV 1 Parainfluenza 1 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 1 Klebsiella oxytoca 2 Varicella zoster virus 3 Herpes simplex virus 25 Rotavirus, adenovirus, and norovirus | 135 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood, urine, and pharyngeal swabs (culture) | 3 | 0 | 2 | (NOS, 7) 135 survived |

| Mannheim et al. 2020 [85], United States | Retrospective case series, single-center | 10 | 4 | Median (IQR), 132 (84–192) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 2 Adenovirus 1 Rhinovirus 1 Escherichia coli 1 Rotavirus | 4 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Serum antibody test (IgM) Urine (culture) | 4 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 4 survived |

| Mansour et al. 2020 [86], Lebanon | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 16 | 0 (0) AND 1 Arab | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Metronidazole | Blood (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Marsico et al. 2022 [87], Italy | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | <1 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Multidrug-resistant Enterobacter asburiae | 1 Azithromycin 1 Vancomycin 1 Ceftazidime 1 Gentamycin 1 Meropenem 1 Aztreonam 1 Ceftazidime/avibactam 1 Fosfomycin | Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Mathur et al. 2022 [11], India | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 327 | 17 | Mean (SD), 137 (32) | 9 (52.9) AND 17 Indian | 17 | 0 | 0 | 17 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 17 Not reported | Blood culture (bacteria) | 6 | 2 | 7 | (NOS, 7) 13 survived 4 died |

| Mithal et al. 2020 [88], United States | Retrospective case series, single-center | 18 | 2 | <3 | 1 (50) AND 2 Hispanic | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 RSV 1 Streptococcus agalactiae 1 Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Urine (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 2 survived |

| Mohammadi et al. 2022 [89], Iran | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 45 | 4 | 1, 36, 72, and 120 | 2 (50) AND 4 Persian | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 Adenovirus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 5) 4 survived |

| Moin et al. 2021 [90], Pakistan | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 4238 | 4 | ≤ 180 (10–180) | 4 (100) AND 4 Pakistani | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 Candida auris 1 Candida albicans 1 Candida tropicalis 1 Candida rugosa | 4 Antibiotics 4 Antifungals | Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 3 survived 1 died |

| Morand et al. 2020 [91], France | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 55 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 EBV | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Mulale et al. 2021 [19], Botswana | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 (100) AND 1 Black | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Rifampin-sensitive Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Ampicillin 1 Gentamicin 1 Rifampicin 1 Isoniazid 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethambutol | PCR assay for gastric lavage (bacteria) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Ng et al. 2020 [92], United Kingdom | Retrospective case series, single-center | 8 | 3 | 12, 0.5, and 10 | 1 (33.3) AND 3 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 Adenovirus 2 Rhinovirus 1 Other coronaviruses (229E, NL63, and OC43) | 1 Amoxicillin 1 Cefotaxime 1 Gentamicin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 3 survived |

| Nieto-Moro et al. 2020 [93], Spain | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 Azithromycin 1 Clindamycin 1 Meropenem 1 Linezolid | Blood (culture) | 1 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Nygaard et al. 2022 [20], Denmark | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 2 | 2 | 24 and 132 | 1 (50) AND 2 White (Caucasian) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus 1 Parainfluenza 1 Rhinovirus | 1 Meropenem 1 Clindamycin 1 Amoxicillin | Blood PCR assays (viruses) Blood, lung biopsy and CSF (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 2 died |

| Oba et al. 2020 [94], Brazil | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 (0) AND 1 Hispanic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Clostridium difficile | 0 | Fecal PCR assays (bacteria) | 1 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Ogunbayo et al. 2022 [95], South Africa | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 36 | 31 | Median (IQR), 16 (5–29) | 19 (61.3) AND 31 Black | 0 | 0 | 53 | 23 Rhinovirus 16 RSV 6 Adenovirus 8 Parainfluenza virus 3 | 31 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 2 | 31 Not reported | 31 Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Palmero et al. 2020 [96], Argentina | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 4 | 4 | Range (60–192) | Gender (not reported) AND 4 Hispanic | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 4 Isoniazid 4 Rifampicin 4 Pyrazinamide 4 Ethionamide | Blood culture (bacteria) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 3 survived 1 died |

| Patek et al. 2020 [97], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 MSSA | 1 Antibiotic 1 Acyclovir | Wound (culture) | 1 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Peng et al. 2020 [98], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 75 | 42 | Mean ± SD, 72.7 ± 57.4 | Gender (not reported) AND 42 Asian | 31 | 0 | 8 | 28 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 1 Moraxella catarrhalis 1 Staphylococcus aureus 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae 3 Influenza B virus 1 Influenza A virus 2 Adenoviridae 1 Cytomegalovirus 1 RSV | 37 1st- or 2nd-generation cephalosporins 28 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Serum antibody test (IgM) for Mycoplasma pneumoniae (only) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 42 survived |

| Pigny et al. 2021 [99], Switzerland | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 51 | 7 | Median (IQR), 50.4 (20.4–87.6) | Gender (not reported) AND 7 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4 Rhinovirus 2 Other coronaviruses (NL63) 2 Adenovirus 1 Metapneumovirus | 7 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 7 Not reported | 7 Not reported | 7 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Plebani et al. 2020 [100], Italy | Retrospective case series, single-center | 9 | 4 | 36, 120, 168, and 120 | 2 (50) AND 4 White (Caucasian) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 Mycoplasma pneumonia | 3 Ceftriaxone 1 Cefotaxime 2 Azithromycin 1 Ampicilline/sulbactam 1 Clindamycin | Serum antibody test (IgM) | 4 Not reported | 4 Not reported | 4 Not reported | (Modified NOS, high) 4 survived |

| Pokorska-Śpiewak et al. 2021 [101], Poland | Prospective case series, single-center | 15 | 1 | 1 Not reported | Gender (not reported) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Influenza A virus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Pucarelli-Lebreiro et al. 2022 [102], Brazil | Prospective cohort, single-center | 105 | 9 | Median, 45 | Gender (not reported) AND 9 Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 10 | 6 RSV 1 Influenza 2 Rhinovirus 1 Norovirus | 9 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 9 survived |

| Rastogi et al. 2022 [103], India | Retrospective case series, single-center | 19 | 1 | 108 | 0 (0) AND 1 Indian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | PCR assay of bronchoalveolar lavage (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Ratageri et al. 2021 [104], India | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 96 | 1 (100) AND1 Indian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 0 | IgM antibody test (dengue) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Raychaudhuri et al. 2021 [105], India | Prospective cohort, single-center | 102 | 43 | Median (IQR), 54 (4.8–90) | 23 (53.4) AND 43 Indian | 26 | 0 | 12 | 4 MRSA 5 MSSA 3 CONS 3 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 Klebsiella pneumonia 7 Scrub typhus 5 Dengue 3 Salmonella typhi 1 Hepatitis A 1 EBV 2 RSV 1 Influenza A virus 1 Adenovirus 1 Rhinovirus | 38 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood, respiratory secretions, and CSF (culture) | 27 | 15 | 14 | (NOS, 8) 39 survived 4 died |

| Rebelo et al. 2022 [21], Portugal | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 168 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Meropenem 1 Vancomycin | Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Said et al. 2022 [106], Saudi Arabia | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 10 | Gender (not reported) AND 1 Arab | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Escherichia coli | 1 Antibiotic | Urine (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 6) 1 survived |

| Sanchez Solano and Sharma 2022 [107], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 192 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 MRSA | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Vancomycin 1 Clindamycin | Bronchoalveolar lavage (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Santoso et al. 2021 [108], Indonesia | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 90 | 1 | 1 Not reported | Gender (not reported) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 1 Not reported | Dengue NS1 antigen IgM and IgG antibody tests (dengue) | 1 Not reported | 1 Not reported | 1 Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Schober et al. 2022 [109], Multi-country | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 403 | 54 | 45.4 (6.4–129.2) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 24 | 0 | 32 | 24 Bacterial 32 Viral | 3 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood (culture) | 10 | 4 | 4 | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| See et al. 2020 [110], Malaysia | Retrospective case reports, multicenter | 4 | 1 | 48 | 0 (0) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Influenza A virus | 1 Phenoxymethylpenicillin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses)c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Serrano et al. 2020 [111], Spain | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 96 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycoplasma pneumonia | 1 Not reported | IgM and IgG antibody tests (Mycoplasma pneumonia) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Shabrawishi et al. 2021 [112], Saudi Arabia | Retrospective case series, single-center | 7 | 1 | 168 | 0 (0) AND 1 Arab | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Azithromycin 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | Blood culture (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Shi et al. 2020 [113], China | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 RSV | 1 Ceftizoxime | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Sibulo et al. 2021 [114], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 36 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 Vancomycin 1 Clindamycin 1 Piperacillin/tazobactam | Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Şık et al. 2022 [115], Turkey | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 14 | 1 | 3 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Rhinovirus | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 1 survived | |

| Somasetia et al. 2020 [22], Indonesia | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 72 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 1 Antibiotics | IgM antibody test (dengue) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Sun et al. 2020 [116], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 36 | 23 | Mean (range), 6.43 (2–12) | Gender (not reported) AND 23 Asian | 23 Not reported | 23 Not reported | 23 Not reported | Unspecified number of Cytomegalovirus, EBV and Mycoplasma pneumonia | 15 Cefmetazole 15 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 22 survived 1 died |

| Sun et al. 2020 [117], China | Retrospective case series, single-center | 8 | 1 | 96 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Influenza A virus | 1 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 Remained in ICU |

| Tadolini et al. 2020 [118], Multi-country | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 49 | 1 | 3 | 1 (100) AND 1 Black | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Antibiotics 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | Blood culture (bacteria) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Tagarro et al. 2021 [119], Spain | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 41 | 2 | Median (IQR), 36 (10.8–72) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (Not reported) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 Influenza B virus | 2 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 2 survived |

| Tan et al. 2020 [120], China | Retrospective case series, single-center | 10 | 3 | 24, 105, and 111 | 1 (33.3) AND 3 Asian | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 Mycoplasma pneumonia 1 Chlamydia pneumonia | 1 Antibiotics | Serum antibody test (IgM) | 3 Not reported | 3 Not reported | 3 Not reported | (Modified NOS, high) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Taweevisit et al. 2022 [23], Thailand | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 67 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 Aspergillus species 1 Cytomegalovirus 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 Acinetobacter baumannii 1 Adenovirus 1 EBV 1 Herpes virus 4 | 1 Antibiotics | Alveolar fluid (culture) RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Serum antibody tests (IgM and IgG) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 died |

| Tchidjou et al. 2021 [121], France | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Citrobacter koseri | 1 Cefotaxime 1 Gentamycin 1 Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Urine (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Tiwari et al. 2020 [122], India | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 168 | 0 (0) AND 1 Indian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Dengue virus | 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Azithromycin | Dengue NS1 antigen IgM antibody test (dengue) | 1 | 0 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Trifonova et al. 2022 [123], Bulgaria | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 242 | 16 | All patients were <192 156 (n = 1) 36 (n = 1) | Gender (not reported) AND 16 White (Caucasian) | 16 Not reported | 16 Not reported | 2 | 2 Influenza A virus | 16 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 16 survived |

| Vanzetti et al. 2020 [124], Argentina | Retrospective, case reports, single-center | 1 | 1 | 204 | 1 (100) AND 1 Hispanic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 Isoniazid 1 Rifampicin 1 Pyrazinamide 1 Ethionamide | PCR assay (bacteria) Sputum (culture) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, moderate) 1 survived |

| Varela et al. 2022 [125], Brazil | Prospective cohort, multicenter | 92 | 31 | Median (IQR), 64.8 (24–122.4) | Gender (not reported) AND 31 Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 30 | 29 Rhinovirus 1 Enterovirus | 5 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 4 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 31 survived |

| Verheijen et al. 2022 [126], The Netherlands | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 0.03 | 0 (0) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Staphylococcus aureus | 1 Flucloxacillin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Vidal et al. 2022 [127], Multi-country | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 29 | 12 | Median, 36 | Gender (not reported) AND 12 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 12 | 12 Adenovirus | 12 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 2 | 12 Not reported | 12 Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Vu et al. 2021 [128], United States | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 48 | 1 (100) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Streptococcus pneumonia | 1 Cefepime 1 Vancomycin 1 Ceftriaxone 1 Amoxicillin | Pleural fluid (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Wanga et al. 2021 [129], United States | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 713 | 113 | Age group <12: 37 (32.4%) patients (viral coinfection) Age group 12–48: 41 (36.1%) patients (viral coinfection) | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 113 Not reported | 113 Not reported | 113 | 113 RSV | 113 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 113 Not reported | 113 Not reported | 113 Not reported | (NOS, 6) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Wehl et al. 2020 [130], Germany | Retrospective case report, single-center | 1 | 1 | 4 | Gender (not reported) AND 1 White (Caucasian) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Influenza A virus | 0 | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 1 survived |

| Wu et al. 2020 [131], China | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 34 | 19 | 72 (1.2–180.9) | Gender (not reported) AND 19 Asian | 16 | 0 | 10 | 16 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 3 RSV 3 EBV 3 Cytomegalovirus 1 Influenza A and B virus | 15 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 0 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 19 survived |

| Xia et al. 2020 [132], China | Retrospective case series, single-center | 20 | 8 | Median, 24 | Gender (not reported) AND 8 Asian | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 Cytomegalovirus 2 Influenza B virus 1 Influenza A virus 4 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 1 RSV | 8 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 8 survived |

| Yakovlev et al. 2022 [133], Russia | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 287 | 32 | Median (IQR), 12 (8.4–30) (viral coinfection) Median (IQR), 144 (90–180) (bacterial coinfection) | Gender (not reported) AND 32 White (Caucasian) | 16 | 0 | 34 | 11 Rhinovirus 11 Other coronaviruses (HKU-1/OC 43) 9 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 7 Chlamydia pneumoniae 4 Metapneumovirus 4 Parainfluenza virus 3 4 Parainfluenza virus 4 | 32 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c Serum antibody tests (IgM and IgG) | 6 | 32 Not reported | 32 Not reported | (NOS, 7) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Zeng et al. 2020 [134], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 3 | 1 | 7.75 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 Enterobacter | 1 Antibiotics | Blood (culture) | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Zhang et al. 2020 [135], China | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 34 | 16 | Median (IQR), 33 (10–94.2) | Gender (not reported) AND 16 Asian | 9 | 0 | 15 | 9 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 6 Influenza B virus 3 Influenza A virus 2 RSV 2 EBV 1 Parainfluenza virus 1 Adenovirus | 11 Antibiotics 9 Azithromycin | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 16 survived |

| Zhang et al. 2021 [136], United States | Retrospective case series, multicenter | 16 | 2 | Mean ± SD, 204 ± 61.3 | Gender (not reported) AND Ethnicity (not reported) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 Rhinovirus 1 Adenovirus 1 RSV 1 Influenza A virus | 2 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 2 Not reported | 2 Not reported | 2 Not reported | (Modified NOS, high) Treatment outcome (not reported) |

| Zheng et al. 2020 [137], China | Retrospective cohort, multicenter | 25 | 3 | Median (IQR), 36 (24–108) | 2 (66.7) AND 3 Asian | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 Mycoplasma pneumoniae 2 Influenza B virus 1 Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 Meropenem 1 Linezolid | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 1 | 1 | 1 | (NOS, 7) 3 survived |

| Zheng et al. 2020 [138], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 4 | 1 | 180 | 1 (100) AND 1 Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 Influenza B virus | 1 Antibiotics | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 1 survived |

| Zhu et al. 2020 [139], China | Retrospective cohort, single-center | 257 | 11 | <180 | Gender (not reported) AND 11 Asian | 20 | 2 | 3 | 6 Streptococcus pneumoniae 5 Haemophilus influenzae 3 Klebsiella pneumoniae 3 Staphylococcus aureus 2 Aspergillus 1 Metapneumovirus 1 Cytomegalovirus 1 Mycoplasma pneumonia 1 Adenovirus 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 Escherichia coli | 11 Not reported | RT-PCR for respiratory specimens (viruses) c | 0 | 0 | 0 | (NOS, 7) 11 survived |

| Zou et al. 2020 [140], China | Retrospective case report, single-center | 2 | 2 | 28 and 156 | 1 (50) AND 2 Asian | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 Influenza A virus | 1 Cefaclor | Serum antibody tests (IgM and IgG) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Modified NOS, high) 2 survived |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CONS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; ICU, intensive care unit; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; RT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SD, standard deviation. a Data are presented as median (25th–75th percentiles), or mean ± SD. b Patients of black ethnicity include African-American, Black African, African, and Afro-Caribbean patients. c PCR assay for multiple respiratory viruses (including influenza virus types A and B, respiratory syncytial virus type A/B, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus types 1–4, other coronaviruses (229E, NL63, and OC43), metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, parechovirus, and bocavirus).

3.2. Demographic, Clinical Characteristics, and Treatment Outcomes of Children with COVID-19 and Bacterial, Fungal, and/or Respiratory Viral Coinfection

The included studies comprised a total of 17,588 children with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were tested for co-pathogens, as detailed in Table 1. Among these 17,588 COVID-19 patients, bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections were reported (n = 1633, 9.3%). The median patient age ranged from 1.4 months to 144 months across studies. There was an increased male predominance in pediatric COVID-19 patients diagnosed with bacterial, fungal, and/or viral coinfections in most of the studies (male gender: n = 204, 59.1% compared to female gender: n = 141, 40.9%) [6,8,10,11,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,31,35,38,40,45,46,47,48,52,54,57,59,60,61,63,64,67,68,69,70,71,74,76,77,81,90,93,95,97,104,105,107,111,113,114,117,118,121,124,128,134,137,138]. The majority of the cases belonged to White (Caucasian) (n = 441, 53.3%) [6,7,9,13,20,21,36,38,39,41,42,44,47,48,50,52,58,60,62,63,65,69,71,75,76,77,79,84,87,91,93,97,99,100,101,107,111,114,115,121,123,126,127,128,130,133], Asian (n = 205, 24.8%) [8,9,22,23,37,45,54,65,66,68,80,81,82,83,98,108,110,113,116,117,120,131,132,134,135,137,138,139,140], Indian (n = 71, 8.6%) [11,31,51,63,72,74,103,104,105,122], and Black (n = 51, 6.2%) [6,9,15,19,46,55,59,60,63,95,118] ethnicities.

COVID-19 children coinfected with bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses were reported to have received antibiotics in 77 studies [5,8,9,12,13,14,15,16,19,20,21,22,23,36,38,39,40,42,45,46,50,51,52,55,56,59,60,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,74,75,76,77,80,86,87,88,90,92,93,96,97,98,100,103,105,106,107,109,110,112,113,114,116,117,118,120,121,122,124,125,126,128,131,134,135,136,137,138,140]. The most prescribed antibiotics were azithromycin (n = 109) [9,15,36,39,64,65,70,76,80,87,93,98,100,109,112,116,122,125,131,135], 1st/2nd/3rd generation of cephalosporins (n = 66) [12,13,42,45,60,65,67,77,87,98,100,113,116,121,128,140], ceftriaxone (n = 29) [12,14,21,38,39,51,52,60,67,68,72,74,86,100,107,112,122,128], isoniazid (n = 13) [19,51,55,59,74,96,103,112,118,124], pyrazinamide (n = 13) [19,51,55,59,74,96,103,112,118,124], rifampicin (n = 13) [19,51,55,59,74,96,103,112,118,124], ethionamide (n = 12) [51,55,59,74,96,103,112,118,124], meropenem (n = 11) [16,20,21,40,50,74,75,80,87,93,137], vancomycin (n = 11) [13,16,21,60,72,74,87,107,114,128], amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (n = 9) [9,45,59,60,76,121], amoxicillin (n = 8) [14,15,20,40,67,77,92,128], clindamycin (n = 8) [13,20,38,60,67,93,100,107,114], ampicillin/sulbactam (n = 7) [39,60,100], and gentamycin (n = 6) [9,19,42,87,92,121]. There were children who were admitted to the intensive care unit (n = 214, 18.6%) [4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,15,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,35,36,39,42,46,51,53,56,58,61,63,64,66,67,72,74,80,81,83,84,85,87,90,92,93,94,95,96,97,105,107,109,113,114,116,117,122,123,125,126,127,128,131,133,134,137], intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation (n = 98, 9.2%) [4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,35,36,39,42,46,51,56,58,61,67,72,74,80,81,83,87,90,96,105,107,109,114,116,117,126,128,134,137], and suffered acute respiratory distress syndrome (n = 100, 12.5%) [4,6,7,8,9,11,12,13,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,39,42,45,46,48,51,55,56,58,61,66,67,72,74,80,81,83,84,87,90,93,96,97,98,105,107,109,113,115,116,117,122,126,128,131,134,137].

Clinical treatment outcomes for the COVID-19 children who were coinfected with bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses and died was documented in 43 (4.4%) cases [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,90,96,105,116], while 931 (95.6%) of the COVID-19 cases recovered [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,31,33,34,35,36,38,40,42,43,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,74,75,76,77,80,81,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,118,119,121,122,123,124,125,126,128,130,131,132,134,135,137,138,139,140], and final treatment outcome was reported in one patient who remained in the intensive care unit (n = 1, %) [117].

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Bacterial, Fungal, and Respiratory Viral Coinfections in Children with SARS-CoV-2

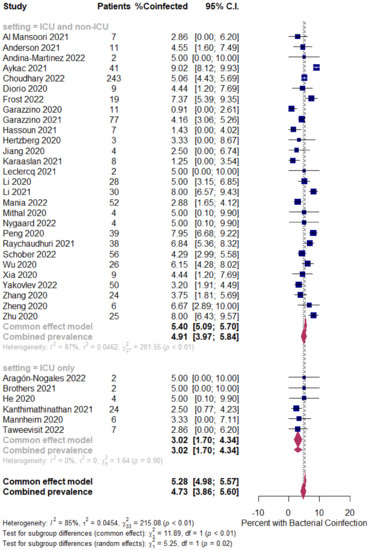

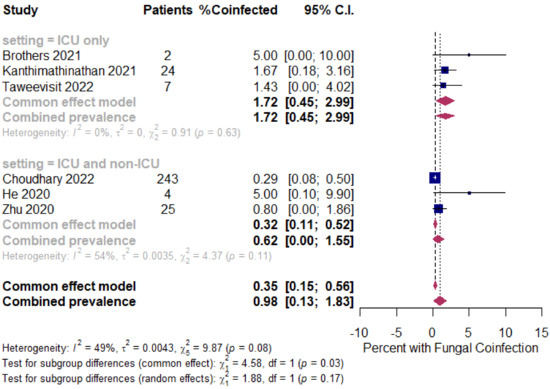

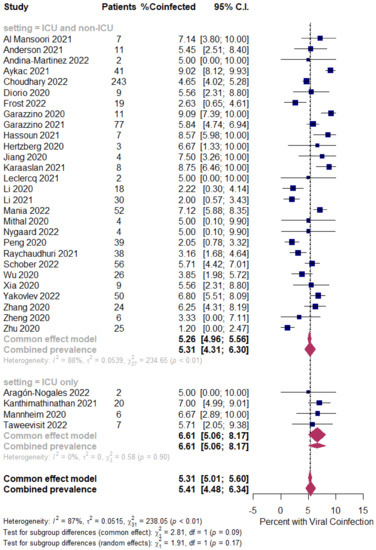

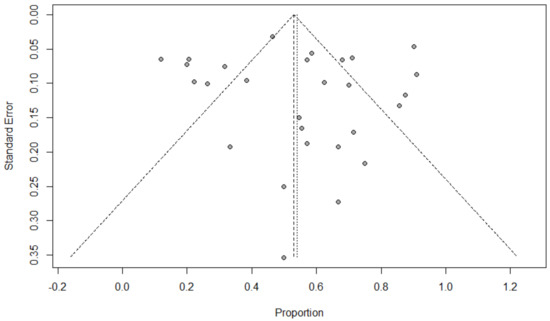

The overall pooled proportions of COVID-19 children who had laboratory-confirmed bacterial, fungal, and respiratory viral coinfections were 4.73% (95% CI 3.86 to 5.60, n = 445, 34 studies, I2 85%, p < 0.01), 0.98% (95% CI 0.13 to 1.83, n = 17, six studies, I2 49%, p < 0.08), and 5.41% (95% CI 4.48 to 6.34, n = 441, 32 studies, I2 87%, p < 0.01), respectively; (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Pooled estimate for the prevalence of bacterial coinfections in children with COVID-19 stratified by the ICU admission (ICU and non-ICU compared to ICU only). [4,5,6,7,8,9,12,13,20,23,32,36,39,57,58,63,64,66,69,77,80,81,84,85,88,98,105,109,131,132,133,135,137,139].

Figure 4.

Pooled estimate for the prevalence of fungal coinfections in children with COVID-19 stratified by the ICU admission (ICU and non-ICU compared to ICU only). [5,8,9,13,23,139].

Figure 5.

Pooled estimate for the prevalence of respiratory viral coinfections in children with COVID-19 stratified by the ICU admission (ICU and non-ICU compared to ICU only). [4,5,6,7,9,12,20,23,32,36,39,57,58,63,64,66,69,77,80,81,84,85,88,98,105,109,131,132,133,135,137,139].

In bacterial coinfected COVID-19 children, subgroup analysis showed some difference in the rates between all patients (patients in the ICU and non-ICU group or ICU only group); the ICU and non-ICU group showed a prevalence of 4.91% (95% CI 3.97 to 5.84, n = 431, 28 studies, I2 87%, p < 0.01), while the ICU only group showed a prevalence of 3.02% (95% CI 1.70 to 4.34, n = 14, six studies, I2 0%, p = 0.90), respectively; Figure 3.

In fungal coinfected COVID-19 children, subgroup analysis showed almost a threefold increase in the rates between all patients (patients in the ICU and non-ICU group or ICU only group); the ICU only group showed a prevalence of 1.72% (95% CI 0.45 to 2.99, n = 11, three studies, I2 0%, p = 0.63), while the ICU and non-ICU group showed a prevalence of 0.62% (95% CI 0.00 to 1.55, n = 6, three studies, I2 54%, p = 0.11), respectively; Figure 4.

However, in the respiratory viral coinfected COVID-19 children, subgroup analysis showed a slight difference in the rates between all patients (patients in the ICU and non-ICU group or ICU only group); the ICU and non-ICU group showed a prevalence of 5.31% (95% CI 4.31 to 6.30, n = 418, 28 studies, I2 88%, p < 0.01), while the ICU only group showed a prevalence of 6.61% (95% CI 5.06 to 8.17, n = 23, four studies, I2 0%, p = 0.90), respectively; Figure 5.

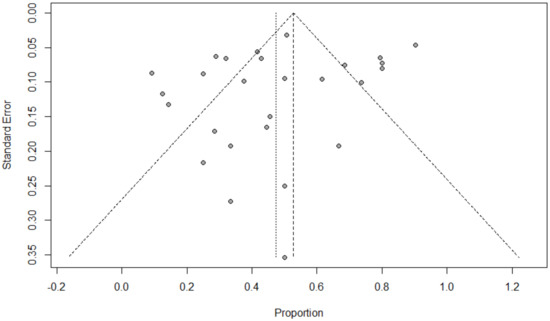

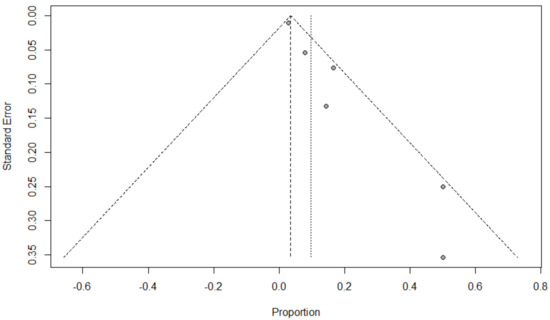

Funnel plots for possible publication bias for the pooled effect size to determine the prevalence of bacterial, fungal, and/or fungal coinfections in children with COVID-19 appeared asymmetrical on visual inspection, and Egger’s tests confirmed asymmetry with p-values < 0.05; Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias for the pooled effect size to estimate the prevalence of bacterial coinfections in children with COVID-19 based on ICU admission.

Figure 7.

Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias for the pooled effect size to estimate the prevalence of fungal coinfections in children with COVID-19 based on ICU admission.

Figure 8.

Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias for the pooled effect size to estimate the prevalence of respiratory viral coinfections in children with COVID-19 based on ICU admission.

3.4. Bacterial, Fungal, and Respiratory Viral Co-Pathogens in COVID-19 Children

Specific bacterial co-pathogens were reported in 71/130 (54.6%) studies, which is about 31.8% of the reported coinfections. The most common bacteria were Mycoplasma pneumoniae (n = 120), Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 65), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (n = 31), Staphylococcus aureus (n = 12), Escherichia coli (n = 11), Haemophilus influenza (n = 10), Chlamydia pneumoniae (n = 9), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 9) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of all identified bacterial co-pathogens in children with COVID-19 (N = 520).

Fungal co-pathogens were reported in 8/130 (6.1%) studies, which is equal to only 1.4% of the reported coinfections. The most common fungal organisms were Aspergillus species (n = 3), fungal bezoars (n = 2), Candida albicans (n = 1), Candida auris (n = 1), Candida glabrata (n = 1), Candida rugosa (n = 1), and Candida tropicalis (n = 1) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Proportion of all identified fungal co-pathogens in children with COVID-19 (N = 23).

Respiratory viral co-pathogens were reported in 88/130 (67.7%) studies, representing about 66.8% of the reported coinfections. The most common respiratory viruses were RSV (n = 342), Rhinovirus (n = 209), Influenza A virus (n = 80), Adenovirus (n = 60), Parainfluenza virus (types 1–4) (n = 29), Influenza B virus (n = 28), Metapneumovirus (n = 27), EBV (n = 14), Cytomegalovirus (n = 12), Dengue virus (n = 12), Coronaviruses (HKU-1/OC 43) (n = 11), and Bocavirus (n = 10) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Proportion of all identified respiratory viral co-pathogens in children with COVID-19 (N = 1090).

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 17,588 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 children from 130 observational studies to estimate the prevalence of coinfections with bacteria, fungi, and/or respiratory viruses. Children with SARS-CoV-2 infection had the following prevalence of pathogen coinfections: bacterial (4.7%, 95% CI 3.8–5.6), fungal (0.9%, 95% CI 0.1–1.8), and respiratory viral (5.4%, 95% CI 4.4–6.3). COVID-19 children had higher fungal and respiratory viral coinfections in ICU units (1.7%, 95% CI 0.4–2.9 and 6.6%, 95% CI 5–8.1, respectively) than mixed ICU and non-ICU patients. However, bacterial coinfection was lower in children infected with SARS-CoV-2 in ICU group (3%, 95% CI 1.7–4.3). Children with COVID-19 seem to have a distinctly lower susceptibility to bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfections than adults. Our study documents that 4.7% (bacteria), 0.9% (fungal), and 5.4% (viral) of the pediatric COVID-19 population harbor microbiologically confirmed coinfections, which is much lower than the recent systematic review and meta-analysis, including 72 studies, conducted from 1 December 2019 to 31 March 2021, portraying coinfection rates of 15.9% (bacterial), 3.7% (fungal), and 6.6% (viral) in the adult COVID-19 population [141]. Lower rates of bacterial, fungal, and/or respiratory viral coinfection in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to the adult COVID-19 population may have different explanations. Immunologically, children seem to have an immature receptor system, immune-system-specific regulatory mechanisms, and possible cross-protection from other common bacterial, fungal, and viral infections occurring in children [142,143]. A growing body of evidence suggests that children’s immune systems can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 because their T cells are relatively naïve and mostly untrained, and thus might have a greater capacity to respond to new viruses and eliminate SARS-CoV-2 before it replicates in large numbers [144,145,146]. Children are also the main reservoir for seasonal coronaviruses, and some researchers have suggested that antibodies for these coronaviruses might confer some protection against SARS-CoV-2 [143,146]. Moreover, children are more protected at the cellular level, as the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which is the receptor that SARS-CoV-2 uses for host entry, is less frequently expressed in the epithelial cells of the nasal passages and lungs of younger children [147]. Otherwise, differences can be explained by the numerous different study designs to a large extent, as well as selection bias, consideration of respiratory and extra-respiratory pathogens, microbiological investigations employed, use of culture and non-culture methods, time of specimen collection, exclusion/inclusion of contaminants, climate, temporal variations in microbial epidemiology and the study population itself.