Abstract

Human filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi continues to circulate within Northern and Central Thailand and Southern Thailand, respectively. Major clinical presentations comprise lymphedema of extremities, hydrocele, funiculitis, orchitis, and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Microfilaria in other organs is rare. We report an unusual case of a 48-year-old woman from Southern Thailand with parotid filariasis presenting with chronic parotid gland enlargement. Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaria was observed within cytologic smear samples from the swollen left parotid gland and subsequently confirmed via a positive filaria immunoblot. The patient’s condition was successfully resolved through administration of a triple regimen consisting of three antiparasitic medications.

1. Introduction

Human filariasis remains classified as a neglected tropical disease. Instigated by the mosquito-borne filarial nematodes, Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori, this infection persists as a public health burden with an estimated 51 million people infected as of 2018, in addition to the 657 million people from 39 countries requiring preventive chemotherapy [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates the implementation of surveillance programs within all endemic countries by 2030 as a means to maintain 80% disease elimination; 35 countries have yet to achieve this benchmark in 2024 [2]. Lymphatic filariasis is endemic in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Pacific regions, and some parts of South America. In Thailand, only Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi are endemic to Northern and Central Thailand and Southern Thailand, respectively. The geographic distribution of Wuchereria bancrofti consists of Mae Hong Son, Chiangmai, Lumphoon, Tak, Kanchanaburi, Ratchaburi, and Ranong provinces [3]. Meanwhile, Brugia malayi is mainly found in the southern provinces, especially Narathiwat, Surat Thani, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Phatthalung, and Pattani [4,5]. However, both species are infrequently reported in other provinces within the mentioned regions of Thailand [6].

An infected individual may present with asymptomatic microfilaremia, acute adenolymphangitis, or acute filarial fever without lymphatic inflammation. Repeated episodes of acute filarial infection progress to a chronic lymphatic disease state with pathological presentations, including but not limited to lymphedema of the legs, arms, breasts, and male genitalia. Common complications include secondary bacterial infections and overlying sclerotic skin alterations. Due to lymphatic system impairment, infected patients can experience pain and develop dysfunctionality of the affected organs, causing mental and physical debilitation, financial loss, and social stigma. The estimated cost of the economic burden of chronic filariasis was US $115 per case, with a total economic burden of US $5.8 billion annually prior to the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) initiation [7,8]. We report an atypical case of human filariasis from Southern Thailand and review other unusual presentations of the disease, highlighting the diagnostic and control challenges in Thailand, an upper-middle-income country, to enhance early clinical recognition and diagnosis, treatment, and prevention education for filariasis.

2. Case Presentation

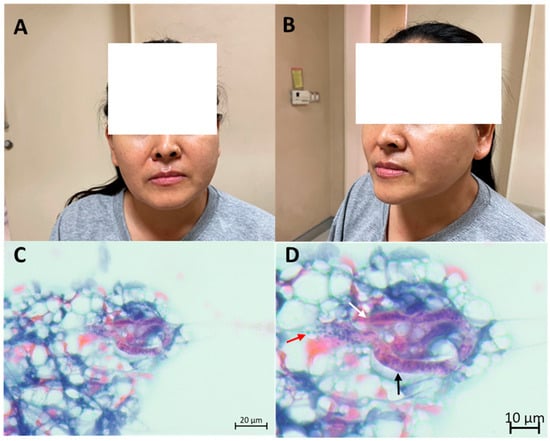

A 48-year-old Thai woman who resides in Surat Thani Province, upper Southern Thailand, presented with a 6-month history of left-sided facial swelling. She was afebrile and denied any additional symptoms or recent travel. She owns a dog, and her residence was located near a rubber forest, where she experienced frequent mosquito bites. Physical examination revealed a 4 × 5 cm non-tender soft enlargement of the left parotid gland (Figure 1A,B). Other findings were within normal limits. Laboratory results showed a normal white blood cell count of 7430 cells/mm3 with eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count 891 cells/mm3). Other laboratory findings were within normal limits.

Figure 1.

Patient’s presentation and fine-needle aspiration cytological findings, which confirm filariasis: left parotid gland enlargement as observed from the front view (A) and side view (B), cytological examination depicting suspected microfilaria in low magnification (C), and high magnification (D) exhibiting nuclei packed densely in a column running along the length of the organism (black arrow), blunt anterior end (white arrow) and nuclei which extends caudally (red arrow).

The initial differential diagnoses included parotid tumor and parotid tuberculosis. She underwent a CT scan of the chest. The CT scan revealed a 2.2 × 1.2 cm well-defined oval-shaped non-enhanced lesion in the prevascular space, which was later found to be a thymoma by surgery. Fine-needle aspiration cytologic smear of the left parotid gland revealed lymphoid cells of various maturation and a few polymorphonuclear cells. Large cells mimicking acinar cells and fibrovascular strands were included. One curved worm was detected (Figure 1C,D). The blunt anterior end was vaguely discernible. The sheath was not clear. Discrete nuclei were seen within the interior of the worm and extended caudally. The microscopic findings were highly suggestive of Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaria based on morphology. No malignancy was detected. The Knott’s concentration test, utilized to analyze nighttime blood samples, which were sent at 10 p.m. for 3 days, revealed negative results. An in-house IgG-immunoblot for filaria incorporated with an IgG4-rapid test kit produced positive results. Parotid filariasis was confirmed by immunoblot and fine-needle aspiration cytologic results. Blood smear was not performed. The patient was treated with a triple regimen of diethylcarbamazine 6 mg/kg, ivermectin 200 mcg/kg, and albendazole 400 mg single dose, and the specified regimen was repeated in the following year. The parotid gland swelling substantially decreased in volume, and the patient continued to appear well throughout a year of follow-ups. Both immunoblot and filariasis rapid test kit results were negative 1-year post-treatment.

3. Discussion

Human filariasis remains a significant neglected tropical disease, causing physical disability, psychological, and economic burden. Typical presentations, such as acute adenolymphangitis, acute fever with lymphadenitis, tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, hydrocele, and elephantiasis, usually lead to an accurate diagnosis and treatment. However, unusual presentations may hinder diagnosis and cause physical and psychological consequences.

The presence of microfilaria within unusual sites is an incidental finding with a limited number of cases reported due to underrecognition. Previously reported detection sites include the cervicovaginal area, thyroid, pericardial effusion, lungs, breast cyst or mass, metastatic lymph nodes or lymph nodes at various sites, ascites, scrotal fluid, within abscess, and bone marrow [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Most cases were incidental findings reported in India, whereby filariasis was not initially suspected. The exact pathophysiological mechanism remains unclear, although a feasible theory entails how microfilaremia causes lymphatic and vascular obstruction, which subsequently leads to microfilaria extravasation in various organs [14].

Challenges in labeling microfilaria as a differential diagnosis or official diagnosis inherently exist due to potential presentations in atypical locations and conditions that mimic other organ-specific pathologies. However, microfilaria will likely be present upon careful examination of pathological sites [15]. Species identification mainly relies on morphological features, with fine-needle aspiration cytological smears as the main diagnostic method. Adult stage worm specimens can be further identified through integrating histopathological evaluations and molecular analysis [16]. A summary of previously reported microfilaria from cytologic smears is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of previously reported microfilaria from cytological smears.

Decades ago, Southern Thailand was considered an endemic area for lymphatic filariasis, especially B. malayi. Upon successful implementation of disease elimination initiatives comprising mass drug administration (MDA) and surveys (both Stop-MDA and transmission assessment surveys) in 11 lymphatic filariasis endemic provinces [5], Thailand attained the WHO criteria for the elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health burden in 2017. Recent post-validation surveillance showed transmission limited to a single province, Narathiwat, where microfilaria prevalence remains below the WHO’s provisional transmission threshold of 1% [4]. Sporadic cases and clusters were reported, whereby some cases were associated with cross-border migrations, and concerns of benzimidazole-resistant W. bancrofti population were reported [3]. These findings highlight the importance of continuing vigilant disease surveillance both in previously implemented units within lymphatic-filariasis-endemic provinces and among units monitoring migrant populations or populations within lymphatic filariasis receptive areas.

Some potential limitations associated with this report can be declared. First, molecular diagnosis was not performed since microfilaria was detected only in fine-needle aspiration cytologic smear samples. Second, the patient’s dog’s blood sample was not obtained, and thus, the following parasites could not be confirmed or ruled out: Dirofilaria immitis infection, which causes heartworm disease in animals; B. malayi, which causes filariasis in both animals and humans; and emerging Brugia pahangi, which was reported to cause zoonotic infection among children in Thailand and adults in Malaysia [18,19]. We, however, report a case of atypical presentation of human filariasis, which caused organ enlargement, and emphasize how enhanced clinical recognition should be confirmed via fine-needle biopsy and histopathology to enable early treatment and prevent unfavorable consequences.

4. Conclusions

We reported a case of parotid filariasis confirmed by histopathology and serology from Southern Thailand. The report suggested that lymphatic filariasis remains present within the area despite attaining a microfilaria prevalence level below the WHO’s provisional transmission threshold of 1%. Early clinical recognition and continued vigilance in regard to disease surveillance were emphasized as a means to control transmission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and study design, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; clinical data collection and interpretation, T.S. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, All authors; supervision, review, and approval, P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was exempted from review by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained for the publication of clinical results and findings under anonymous conditions.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our patient for consenting to allow the use of medical records and photos, and for information dissemination presented herein in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CT | Computerized tomography |

| MDA | Mass drug administration |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Lymphatic Filariasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lymphatic-filariasis (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: Progress Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer10040-439-449 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Bhumiratana, A.; Intarapuk, A.; Koyadun, S.; Maneekan, P.; Sorosjinda-Nunthawarasilp, P. Current Bancroftian Filariasis Elimination on Thailand-Myanmar Border: Public Health Challenges toward Postgenomic MDA Evaluation. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2013, 2013, 857935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meetham, P.; Kumlert, R.; Gopinath, D.; Yongchaitrakul, S.; Tootong, T.; Rojanapanus, S.; Padungtod, C. Five years of post-validation surveillance of lymphatic filariasis in Thailand. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojanapanus, S.; Toothong, T.; Boondej, P.; Thammapalo, S.; Khuanyoung, N.; Santabutr, W.; Prempree, P.; Gopinath, D.; Ramaiah, K.D. How Thailand eliminated lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2019, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Disease Control. Filariasis. Available online: https://www.ddc.moph.go.th/disease_detail.php?d=85 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Mathew, C.G.; Bettis, A.A.; Chu, B.K.; English, M.; Ottesen, E.A.; Bradley, M.H.; Turner, H.C. The Health and Economic Burdens of Lymphatic Filariasis Prior to Mass Drug Administration Programs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 2561–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconez-Gonzalez, J.; Miño, C.; Noboa, M.d.L.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Ortiz-Prado, E. The psychosocial and emotional burden of lymphatic filariasis: A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, M.; Pruthi, S.K.; Gupta, R.; Khare, P. Unusual presentation of filariasis as an abscess: A case report. J. Cytol. 2016, 33, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanya, C.S.; Jayaprakash, H.T. Microfilariae, a Common Parasite in an Unusual Site: A Case Report with Literature Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, Ed08–Ed09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolte, S.S.; Satarkar, R.N.; Mane, P.M. Microfilaria concomitant with metastatic deposits of adenocarcinoma in lymph node fine needle aspiration cytology: A chance finding. J. Cytol. 2010, 27, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakra, P.S.; Sinha, J.K.; Khurana, U.; Tandon, A.; Joshi, R. An Unusual Encounter: Microfilaria Incidentally Detected in the Bone Marrow Aspirate of a Chronic Kidney Disease Patient. Cureus 2024, 16, e59808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Gupta, P.; Bhardwaj, M.; Durga, C.K. Isolated Epitrochlear Filarial Lymphadenopathy: Cytomorphological Diagnosis of an Unusual Presentation. Turk. Patoloji Derg. 2020, 36, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, T.R.; Raghuveer, C.V.; Pai, M.R.; Bansal, R. Microfilariae in Cytologic Smears: A Report of Six Cases. Acta Cytol. 2011, 40, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantola, C.; Kala, S.; Agarwal, A.; Khan, L. Microfilaria in cytological smears at rare sites coexisting with unusual pathology: A series of seven cases. Trop. Parasitol. 2012, 2, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarasombath, P.T.; Sitthinamsuwan, P.; Wijit, S.; Panyasu, K.; Roongruanchai, K.; Silpa-Archa, S.; Suwansirikul, M.; Chortrakarnkij, P.; Ruenchit, P.; Preativatanyou, K.; et al. Integrated Histological and Molecular Analysis of Filarial Species and Associated Wolbachia Endosymbionts in Human Filariasis Cases Presenting Atypically in Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 111, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Pujani, M.; Pujani, M. Microfilaria in malignant pleural effusion: An unusual association. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 28, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhumiratana, A.; Nunthawarasilp, P.; Intarapuk, A.; Pimnon, S.; Ritthison, W. Emergence of zoonotic Brugia pahangi parasite in Thailand. Vet. World 2023, 16, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamyingkird, K.; Junsiri, W.; Chimnoi, W.; Kengradomkij, C.; Saengow, S.; Sangchuto, K.; Kajeerum, W.; Pangjai, D.; Nimsuphan, B.; Inpankeaw, T.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with Dirofilaria immitis infection in dogs and cats in Songkhla and Satun provinces, Thailand. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2017, 51, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).