Abstract

With the advancement of haptic technology, the use of pseudo-haptics to provide tactile feedback without physical contact has garnered significant attention. This paper aimed to investigate whether sliding fingers over onomatopoetic text strings with pseudo-haptic effects induces change in perception toward their symbolic semantics. To address this, we conducted an experiment using finger-point reading as our subject matter. The experimental results confirmed that the “neba-neba,” “puru-puru,” and “fusa-fusa” effects create a pseudo-haptic feeling for the associated texts on the “hard–soft,” “slippery–sticky,” and “elastic–inelastic” adjective pairs. Specifically, for “hard–soft,” it was found that the proposed effects could consistently produce an impact.

1. Introduction

Recent research has explored providing tactile stimulation during e-book reading, finding it promotes narrative comprehension [1,2]. However, we believe such systems are difficult to generalize due to the need for dedicated actuators attached to tablets. We therefore focused on pseudo-haptics, a technique that allows for tactile feedback without physical contact. Pseudo-haptics refers to an imaginary haptic sensation perceived through changes in a mouse pointer or background image accompanying a user’s subjective movement. The core of pseudo-haptics is the discrepancy between a user’s physical action and the visual feedback they receive [3,4].

While the dynamic display of text on computers is known to effectively convey the tone and emotion of speech [5,6,7], prior pseudo-haptics research has primarily focused on the motion of self-projected images like mouse pointers. There has been no investigation into the effects of pseudo-haptics on the perception and semantic understanding readers gain when the visual changes occur on meaningful text strings. On the other hand, many studies have revealed that finger-point reading enhances reading comprehension [8,9]. In addition, a study by Marutani et al. [10] found that the dynamic display of characters during finger-point reading can alter perceptions.

Therefore, this paper investigates the impact of pseudo-haptics on the perception derived from text strings with symbolic semantics. To achieve this, we chose finger-point reading as our subject matter. Our goal is to extend the interpretation of meaning in finger-point reading by examining the effects of adding pseudo-haptics. While we considered applying pseudo-haptics to entire sentences, we initially narrowed our target text to onomatopoeia to minimize ambiguity in the interpretation of symbolic semantics. Here, onomatopoeia is the formation of a word from a sound associated with what is named. In this paper, the Japanese onomatopoeia we use refers to character strings commonly used in Japanese, such as “neba-neba,” which represent repetitive sounds describing contact with an object. The term symbolic semantics in this paper is a technical term used to express the meaning of characters as symbols. Our research question is to identify the effect of pseudo-haptics on symbolically semantic characters, and specifically, how it influences their symbolic semantics. This will allow us to expand the application of pseudo-haptics to text-based media, such as e-books.

2. Effect to Onomatopeia

First, we held an experiment to investigate differences in perceptions evoked by onomatopoeic characters with pseudo-haptic effects, displayed on a touchscreen, using the method of constant stimuli. However, we found that the method of constant stimuli required lengthy, repetitive trials, which led to participants not consistently performing appropriate symbolic semantics interpretations. Therefore, we decided to use short sentences containing onomatopoeia as our target strings to comprehend the symbolic semantics, with only the onomatopoeic portion subject to the pseudo-haptic effect.

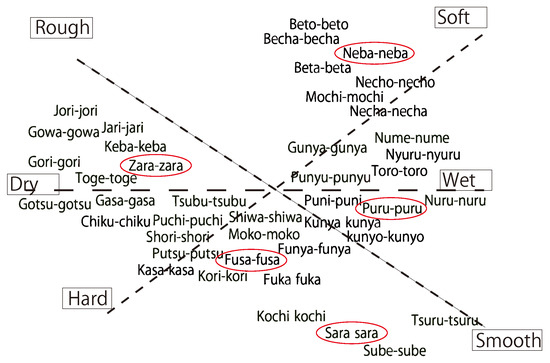

In this study, we selected representative onomatopoeia as our graphical motifs, drawing from an onomatopoeia map created in prior research on haptics and onomatopoeia analysis [11]. Specifically, we chose “neba-neba” (sticky), “zara-zara” (rough), “fusa-fusa” (fluffy), “puru-puru” (jiggly), and “sara-sara” (smooth/sandy), as they represent distinct points near the ends of the respective axes on the map (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Onomatopoeia map [11]: The red circles show the onomatopoeia selected for the experiment. “Neba-neba” (sticky), “zara-zara” (rough), “fusa-fusa” (fluffy), “puru-puru” (jiggly), and “sara-sara” (smooth/sandy) were chosen, because they represent distinct points near the ends of the respective axes on the map.

The design criteria for the graphics expressing each onomatopoeia were created based on principles from animated text [12], with the following conditions:

- Expressible using flat graphics.

- The original calligraphy should be discernible.

It should be noted that the objective of this research is to evaluate the effectiveness of pseudo-haptics for characters allowing for symbolic interpretation, and thus, the optimization of graphic effects is not a focus of this research.

Designs of Pseudo-Haptic Effect

As mentioned above, pseudo-haptics is the discrepancy between a user’s physical action and the visual feedback they receive. To design pseudo-haptic effect toward onomatopoeia text on touchscreen, we use finger movement as input and corresponding visual effects toward the text as output. Each effect is explained below. The following effects were made with Unity, and their animation frame rates were all 60 fps. We employed a Microsoft Surface as a touchscreen, and the following effects were displayed and interacted with it. For each effect, we created two-staged (weak/strong) effects for the following experiment.

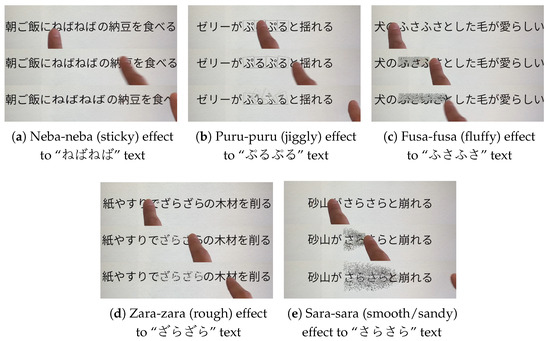

First, for the “neba-neba” (sticky) effect, we created graphics that stretch with finger movement. To maintain calligraphic consistency and allow it to return to its original state, we simulated a spring-like motion. We hypothesized that the displacement in the x-direction from where the finger is placed represents a virtual force . The extent of the onomatopoeic character’s stretch and contraction, , is expressed as the extension of a spring using a spring constant k. We then adjusted the effect’s intensity in two stages by varying this spring constant (Figure 2a). When the finger is lifted from the screen, the graphic returns to its normal size, exhibiting damped oscillation (underdamped) and changing in magnitude.

Figure 2.

Stop-motion images illustrating pseudo-haptics effects for each onomatopeia: based on the movement of the user’s finger, each visual effect is displayed. (a) Neba-neba effect: features a spring-like motion. The Japanese sentence means “I eat sticky natto for breakfast.” (b) Puru-puru effect: shows a jelly wobbling. The sentence means “The jelly jiggles.” (c) Fusa-fusa effect: depicts a flattening fur. The sentence means “The dog’s fluffy fur is adorable.” (d) Zara-zara effect: includes visual vibration and chip generation. The sentence means “Sanding rough wood with sandpaper.” (e) Sara-sara effect: presents a collapsing sand pile. The sentence means “The sand dune crumbles softly.” Each video can be found in the Supplementary file: Video S1.

Next, for the “puru-puru” (jiggly) effect, we simulated the appearance of jelly wobbling. In this graphic, the movement of objects, such as their displacement angle, responds to changes in the damping oscillation amplitude (A), allowing for two-stage effect intensity adjustments based on the initial amplitude (Figure 2b). The damping oscillation equation is as follows: . For the “fusa-fusa” (fluffy) effect, when a finger touches the character, the “fur” appears to flatten by controlling the leaning angle, , of linked small parts of the character. The n-th part’s angle is calculated by the follwoing equation: , where is proportional to the finger movement. After a set period, it returns to its original position. The two-level effect intensity is adjusted by the time t it takes for the “fur” to flatten (Figure 2c). We set it to remain in the flattened state for 0.5 s after collapsing, then return to its original position over 0.5 s.

For the “zara-zara” (rough) effect, we made the visuals vibrate based on the recorded acceleration by the experimenter’s finger on #40 sandpaper. By using the movement of the user’s finger, the corresponding recorded data are derived. Thus, the visual movement, , is as follows: . Simultaneously, as the finger moved, we generated objects that represented chips from the text. We set two types of acceleration values (a) for the experiment: (no smoothing) and (moving average of 15 consecutive points). These were used to adjust the two-stage effect intensity (Figure 2d). Finally, for the “sara-sara” (smooth/sandy) effect, we created an effect where the parts of the text moves as if a sand pile is collapsing ramdomly. We adjusted the two-stage effect intensity using the maximum displacement of the parts (Figure 2e).

3. Experiment

Our research aims to verify the effect of pseudo-haptics on text with symbolic semantics, so the optimal nature of the graphical effect is not a focus of the research. To investigate the influence of pseudo-haptic stimuli on symbolic semantic interpretation, we compared sentences that had symbolic semantics related to the created pseudo-haptic stimuli with sentences that did not have such related symbolic semantics (Table 1). The perception of each effect was then investigated using the Semantic Differential (SD) method. The five-point scale of the Semantic Differential (SD) method is a way to evaluate impressions of an object using a pair of opposing adjectives (e.g., “bright–dark”) on a five-point scale.

Table 1.

Sentences used in the experiment. These sentences are translated into English.

In this experiment, participants were asked to trace-read sentences displayed on a tablet, with each character measuring 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm, at a speed of approximately 10 cm/s. To prevent participants from tracing without interpreting the meaning and to standardize the time required for meaning interpretation, audio readings of the sentences were created using VOICEPEAK version 1.0.1 (AHS Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan)), and participants were instructed to trace along with the audio.

For these sentences, the pseudo-haptics effect was applied under three conditions: “no effect,” “weak,” and “strong.” Participants then performed finger-point tracing. After the finger-point tracing, they were asked to rate their perception of the sentences using the SD method’s evaluation axes, and the experiment concluded after collecting their subjective comments.

The seven evaluation axes for the SD method used in this experiment were adopted from Sakamoto et al.’s work [13,14], where they developed a system to visualize individual differences in tactile sensation using an onomatopoeia distribution map. These axes are as follows: “warm–cold,” “hard–soft,” “inelastic–elastic,” “wet–dry,” “slippery–sticky,” “bumpy–flat,” and “smooth–rough.”

To prevent habituation effects on meaning interpretation due to repetition in each experiment, we used different sentences for every effect. Specifically, participants performed finger-point reading on the following sentence pairs for each pseudo-haptic effect. The sentences containing the selected onomatopoeia used in this experiment were taken from “Onomatopoeia and Mimetic Words 4500: A Japanese Onomatopoeia Dictionary” [15]. For these 10 types of sentences, one of three degrees of effect was assigned to each participant. The presentation order was randomized for each participant.

Specifically, participants performed finger-point reading on the following sentence pairs (Table 1). For example; for “neba-neba” (sticky) pseudo-haptic effect: sentences containing “neba-neba” and “shin-shin” (quietly/deeply), and so on. The experiment involved 16 participants, both male and female, aged 21–24 years old. Figure 3 shows the experimental setup.

Figure 3.

Overview of the experimental setup.

Statistical Analysis and Results

For the obtained results, a significance level of 5% was set. For data confirmed to be normally distributed by the Shapiro–Wilk test, we used Repeated Measures ANOVA (by statsmodels 0.14.4). For data not confirmed to be normally distributed, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. If a statistically significant difference was found among the three groups, the Scheffé method was used for pairwise comparisons between each pair of groups.

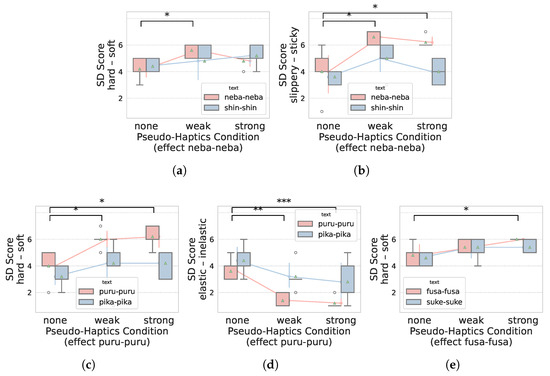

First, we examined the results for sentences with a symbolic semantics related to the pseudo-haptic effect, for example, a “neba-neba” (sticky) pseudo-haptic effect applied to a sentence containing “neba-neba.” This revealed a statistically significant difference for the “neba-neba,” “fusa-fusa,” and “puru-puru” pseudo-haptic effects when compared to the no effect condition (see Figure 4a–e: in these figures, * indicates a p-value of less than a 5% statistical significance level, ** a p-value of less than a 1% statistical significance level, and *** a p-value of less than a 0.5% statistical significance level). Therefore, we confirmed that the created effects produced pseudo-haptic feelings in the participants.

Figure 4.

Evaluated SD Scores of the adjective pairs for each pseudo-haptic effect under each related/unrelated onomatopoeia text. For the related onomatopoeia, statistically significant differences were observed between no effect and the other conditions. (a) Hard–soft evaluation under neba-neba effect; (b) slippery–sticky evaluation under neba-neba effect; (c) hard–soft evaluation under puru-puru effect; (d) elastic–inelastic evaluation under puru-puru effect; (e) hard–soft evaluation under fusa-fusa effect. In these figures, * indicates a p-value of less than a 5% statistical significance level, ** a p-value of less than a 1% statistical significance level, and *** a p-value of less than a 0.5% statistical significance level. The green triangle markers indicate the mean value of each condition, while the white circles denote outliers.

Next, we compared these three effects with results from sentences that did not have a symbolic semantics related to the pseudo-haptic effect (e.g., a “neba-neba” pseudo-haptic effect applied to a sentence that did not contain an onomatopoeia of “neba-neba”). The results are shown below figures (Figure 4a–e). As shown in each figure, there are statistically significant differences between no effect and weak/strong effects in related texts (for example, an onomatopoeia of “neba-neba” with a “neba-neba” pseudo-haptic effect). However, there are no statistically significant differences in unrelated texts (for example, an onomatopoeia of “shin-shin” with a “neba-neba” pseudo-haptic effect).

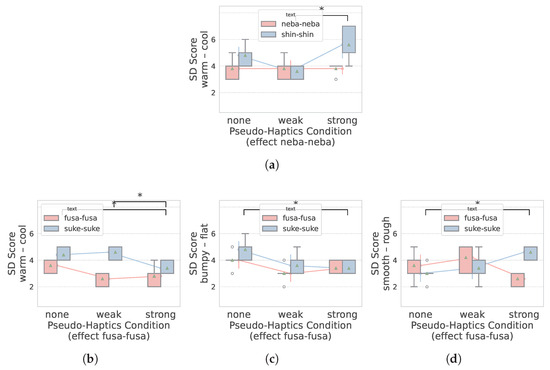

On the other hand, we examined other effects, “zara-zara” and “sara-sara,” which show no statistically significant difference when compared to the no effect condition in related texts. The results are shown in the figures below (Figure 5a–d). As shown in each figure, there are statistically significant differences between a strong-effect condition and the others in unrelated texts (for example, an onomatopoeia of “shin-shin” with a “neba-neba” pseudo-haptic effect). However, there are no statistically significant differences in related texts (for example, an onomatopoeia of “neba-neba” with a “neba-neba” pseudo-haptic effect).

Figure 5.

Evaluated SD Scores of the adjective pairs for each pseudo-haptic effect under each related/unrelated onomatopoeia text. For the unrelated onomatopoeia, statistically significant differences were observed between the strong effect and the other conditions. (a) Warm–cool evaluation under neba-neba effect; (b) warm–cool evaluation under fusa-fusa effect; (c) bumpy–flat evaluation under fusa-fusa effect; (d) smooth–rough evaluation under fusa-fusa effect. In these figures, * indicates a p-value of less than a 5% statistical significance level. The green triangle markers indicate the mean value of each condition, while the white circles denote outliers.

4. Discussion

Our experimental results show the following: For the “neba-neba” onomatopoeia, the associated “neba-neba” effect produced a statistically significant difference compared to no effect in the evaluation of both hard–soft and slippery–sticky qualities. For the “puru-puru” onomatopoeia, the associated “puru-puru” effect produced a statistically significant difference compared to no effect in the evaluation of both hard–soft and elastic–inelastic qualities. For the “fusa-fusa” onomatopoeia, the associated “fusa-fusa” effect produced a statistically significant difference compared to no effect in the evaluation of the hard–soft quality. These findings confirm that the “neba-neba,” “puru-puru,” and “fusa-fusa” effects create a pseudo-haptic feeling for their respective associated texts, specifically across the adjective pairs of hard–soft, slippery–sticky, and elastic–inelastic. Notably, for hard–soft, our proposed effects commonly yielded a significant impact.

When the “neba-neba” effect was applied to the “shin-shin” onomatopoeia text, we found no statistically significant difference compared to no effect in the evaluation of hard–soft and slippery–sticky qualities. Similarly, with the “puru-puru” effect to the “pika-pika” onomatopoeia text, there was no statistically significant difference compared to no effect in the evaluation of hard–soft and elastic–inelastic qualities. And for the “fusa-fusa” effect to the “suke-suke” onomatopoeia text, no statistically significant difference was found compared to no effect in the evaluation of the hard–soft quality.

From this, we can conclude that while effects associated with their respective onomatopoeia result in effective pseudo-haptics, effects using unrelated onomatopoeia do not. In other words, we found that there is some correlation between the symbolic semantics of an onomatopoeia and the perception of pseudo-haptics.

Conversely, our pseudo-haptic effects were unable to produce an impact on the adjective pairs of “warm–cold,” “wet–dry,” “bumpy–flat,” and “smooth–rough.” It is likely that our chosen pseudo-haptic effects, being image-dependent, had difficulty influencing perceptions related to heat or wetness. Furthermore, “bumpy–flat” typically evokes vertical displacement, which was challenging to represent with the planar and simple visual changes employed in this study. For “smooth–rough,” which suggests subtle variations in response to finger movement, our application’s “zara-zara” visual vibrate effect, designed to generate fine effects, operated at only 12 frames per second (fps). This limited responsiveness to finger movements likely resulted in the reduced effectiveness observed.

Additionally, a statistically significant difference was found between the strong effect and other effects for the “neba-neba” effect toward “shin-shin” onomatopoeia text in the evaluation of warm–cool, and for the “fusa-fusa” effect toward “suke-suke” onomatopoeia text in the evaluation of warm–cool, bumpy–flat, and smooth–rough. As mentioned above, these adjective pairs were likely difficult to represent with the visual changes used in this study. However, despite this, the appearance of a statistically significant difference suggests that large visual changes might possess an effect separate from the intended onomatopoeia.

As previously stated, the primary objective of this research was to verify the effect of pseudo-haptics on characters capable of symbolic semantic interpretation; thus, the optimality of the graphic images was not the focus. However, anticipating that graphic images whose perceptions change based on the magnitude of the change exist, it will be necessary to investigate more optimal visual changes in the future.

5. Conclusions

With the advancement of haptic technology, the use of pseudo-haptics to provide tactile feedback without physical contact has garnered significant attention. However, research concerning pseudo-haptics has primarily focused on changes in the movement of self-projected images, such as mouse pointers. There have been no studies that investigate its effects on meaningful text strings (i.e., those with symbolically interpretable meaning), specifically regarding the impact on the interpreted perceptions readers gain.

Therefore, this paper aimed to investigate the influence of pseudo-haptics on the perception derived from text strings that possess symbolic semantics. Our research question is to identify the effect of pseudo-haptics on symbolically meaningful characters, and specifically, how it influences their symbolic semantics.

To address this, we conducted an experiment using finger-point reading as our subject matter. Our goal was to extend the interpretation of meaning in finger-point reading by examining the effects of adding pseudo-haptics.

The experimental results confirmed that when related effects were applied to the “neba-neba,” “puru-puru,” and “fusa-fusa” onomatopoeia texts, a statistically significant difference was observed in the “hard–soft,” “slippery–sticky,” and “elastic–inelastic” evaluations compared to the no effect condition. These findings confirm that the “neba-neba,” “puru-puru,” and “fusa-fusa” effects create a pseudo-haptic feeling for the associated texts on the “hard–soft,” “slippery–sticky,” and “elastic–inelastic” adjective pairs. Specifically, for “hard–soft,” it was found that the proposed effects could consistently produce an impact.

Conversely, when the same effects were applied to unrelated onomatopoeia text, no statistically significant difference was found. Moreover, for visual-dependent pseudo-haptics, it was found that the current visual-effect-driven approach could not induce changes for the “warm–cold,” “wet–dry,” “bumpy–flat,” and “smooth–rough” adjective pairs. This suggests that while pseudo-haptics related to onomatopoeia are effective, those unrelated to onomatopoeia are not. This indicates some correlation between symbolic semantics and pseudo-haptic perception.

In this study, graphics were created using onomatopoeia as a motif, but the expression methods and parameters used were specified by the authors and do not precisely simulate the behavior of objects described in the text. As previously stated, the purpose of this research was to verify the effect of pseudo-haptics on characters with interpretable symbolic semantics, so the optimality of the graphics image was not a primary concern. However, anticipating that some graphic images may alter perceptions based on the magnitude of change, it will be necessary to investigate more optimal image changes in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/mti9100100/s1, Video S1: Pseudo-haptics effects for each onomatopeia.

Author Contributions

S.S. served as the principal investigator, coordinating the research, managing the data, and drafting the manuscript. K.S. was responsible for conducting the experiments, organizing the experimental data, and co-authoring the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 24K03019) and the Murata Science and Education Foundation (grant number M24AN141).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kumamoto University (protocol code: R4-1, and the approval date is 7 September 2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Kanta Shirakawa has been employed by Kyushu Hitachi Systems, Ltd. since the completion of this research. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cingel, D.; Piper, A.M. How Parents Engage Children in Tablet-Based Reading Experiences: An Exploration of Haptic Feedback. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; CSCW ’17. pp. 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannier, N.; Israr, A.; Lehman, J.F.; Klatzky, R.L. FeelSleeve: Haptic Feedback to Enhance Early Reading. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; CHI ’15. pp. 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Yasumura, M. VisualHaptics: Generating Haptic Sensation Using Only Visual Cues. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, Yokohama, Japan, 3–5 December 2008; ACE ’08. p. 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujitoko, Y.; Ban, Y.; Narumi, T.; Tanikawa, T.; Hirota, K.; Hirose, M. Yubi-Toko: Finger Walking in Snowy Scene Using Pseudo-Haptic Technique on Touchpad. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2015 Emerging Technologies, Kobe, Japan, 2–6 November 2015; SA ’15. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Forlizzi, J.; Ishizaki, S. Kinetic Typography: Issues in Time-Based Presentation of Text. In Proceedings of the CHI ’97 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, Georgia, 22–27 March 1997; CHI EA ’97. pp. 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhler, G.; Osen, M.; Harrikari, H. A User Interface Framework for Kinetic Typography-Enabled Messaging Applications. In Proceedings of the CHI ’04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vienna, Austria, 24–29 April 2004; CHI EA ’04. pp. 1505–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine, K.; Pignol, M. Kinetic Typography-Based Instant Messaging. In Proceedings of the CHI ’03 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA, 5–10 April 2003; CHI EA ’03. pp. 914–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehri, L.C.; Sweet, J. Fingerpoint-Reading of Memorized Text: What Enables Beginners to Process the Print? Read. Res. Q. 1991, 26, 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, C.; Rodella, A.; Nadalini, A.; Taxitari, L.; Pirrelli, V. Does Finger-Tracking Point to Child Reading Strategies? In Proceedings of the Seventh Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics CLiC-it 2020, Bologna, Italy, 1–3 March 2021; Dell’Orletta, F., Monti, J., Tamburini, F., Eds.; Collana Dell’Associazione Italiana Di Linguistica Computazionale, Accademia University Press: Torino, Italy, 2020; pp. 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruya, K.; Watanabe, J.; Takahashi, H.; Hashiba, S. A Learning System Utilizing Learners’ Active Tracing Behaviors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Learning Analytics And Knowledge, Poughkeepsie, NY, USA, 16–20 March 2015; LAK ’15. pp. 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Hayakawa, T.; Matsui, S.; Kano, A.; Shimizu, Y.; Sakamoto, M. Visualization of Tactile Material Relationships Using Sound Symbolic Words. In Proceedings of the Haptics: Perception, Devices, Mobility, and Communication, Tampere, Finland, 13–15 June 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. The Animator’s Survival Kit: A Manual of Methods, Principles and Formulas for Classical, Computer, Games, Stop Motion and Internet Animators, expanded edition ed.; Faber & Faber: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, M.; Tahara, T.; Watanabe, J. A System to Visualize Individual Variation in Tactile Perception using Onomatopoeia Map. Trans. Virtual Real. Soc. Jpn. 2016, 21, 213–216. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Watanabe, J. Visualizing Individual Perceptual Differences Using Intuitive Word-Based Input. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, M. Onomatopoeia and Mimetic Words 4500: A Japanese Onomatopoeia Dictionary; Shogakukan: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).