Abstract

As landscape architecture shifts toward evidence-based practices, the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF)’s Case Study Investigation (CSI) initiative has been instrumental in driving the growth of Landscape Performance Evaluation (LPE) and enhancing disciplinary rigour. This paper reflects on our CSI case study, evaluating Te Whāriki, a master-planned residential landscape in New Zealand. We adopt a methodological reflexivity approach, critically examining the challenges faced and insights gained during the evaluation, providing a comprehensive reflection on the current practical challenges and potential future research directions in the field of LPE. This research reflects upon the methodological reliability of LPE approaches, challenging stereotypes surrounding “measured” and “estimated” methods. Our study emphasises the importance of improving input data quality, explores the trade-off between accuracy and cost, and introduces the concept of a universal currency for landscape benefits. By offering our reflections, this paper aims to stimulate further conversations and catalyse ongoing iterations in the evaluation framework and methodological exploration within this evolving field.

1. Introduction

Landscape architecture, as a young discipline, has evolved swiftly over the past half-century [1,2]. During this period of rapid development, pioneering researchers and practitioners have been constantly pushing the boundaries of the discipline in various directions [1,3,4,5]. Their explorations have led to a growing awareness that carefully designed landscapes possess immense potential to yield a wide array of benefits [5,6,7]. Scholars, practitioners, governments, and the general public are increasingly acknowledging the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural values that landscape architects can offer [7,8].

Contemporary landscape architecture researchers and practitioners hold the belief that by implementing well-planned and effective landscape interventions, the designed landscape can play a pivotal role in conserving soil; regulating water circulation; safeguarding and promoting biodiversity; conserving energy; reducing emissions; mitigating the urban heat island effect; enhancing air quality; offering recreational and educational opportunities; improving environmental safety; enriching spatial experiences; fostering equality and justice; preserving cultural heritage; stimulating economic development; generating employment prospects; and delivering a host of other advantageous outcomes [6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

However, concurrently, the built environment sector is recognised as a significant contributor to the world’s present environmental crisis, accounting globally for 35% of energy consumption, 16% of water usage, and 38% of greenhouse gas emissions [16,17]. Despite being a part of this problematic sector and contributing to these environmental crises, landscape architects often perceive themselves as the environmentally conscious side of the industry, dedicated to saving humanity from the crisis [18]. Nevertheless, some of these idealistic notions held by landscape architects are being challenged by empirical studies. Craig Pocock, a landscape practitioner and researcher, conducted a study to assess the actual carbon footprint of his past projects, responding to his own discomfort with those idealistic assumptions [18]. Despite a professional practice history that he considered to be typical in terms of carbon footprint, the results were alarming—Pocock’s carbon footprint fell significantly short of being carbon neutral, requiring approximately 120,000 more trees to offset it [18]. Pocock [19,20] emphasised that the embodied carbon footprint of materials commonly specified by landscape architects is substantial, far exceeding the carbon that can be offset by planting work throughout their entire careers.

Beyond the rosy illusion of being environmentally friendly, various studies also cast doubts on the claims made about the extensive range of benefits offered by landscape architects. A study conducted by Jacky Bowring and Marion MacKay [21] revisited 12 award-winning projects in New Zealand to evaluate their long-term performance. Surprisingly, many of these landscapes, celebrated as exemplars of design excellence, did not live up to expectations and failed to deliver their intended benefits. As Barnes [8] aptly noted, assertions of diverse landscape benefits pervade the industry, yet individual firms frequently lack an accurate grasp of whether their endeavours genuinely achieve these presumed benefits in practice. Further, there are also studies identifying adverse repercussions and challenges arising from landscape architecture practices, such as social inequality, degraded biodiversity, impacts of urban sprawl, and other intricacies [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. These cautionary signals highlight the imperative for landscape architects to comprehend the full extent of their impacts. There is a pressing need for landscape architects to impartially assess their contributions to human well-being, irrespective of whether those impacts are positive or negative [29].

Consequently, landscape architecture is undergoing a significant transformation, evolving into an evidence-based discipline, placing increased emphasis on rigour [30,31]. Over the past decade, there has been an increased understanding of the inherent value that landscape architecture can bring [32,33]. In this transformative journey, the Case Study Investigation (CSI) initiative spearheaded by the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF), has played an instrumental role [30].

In 2010, measuring and documenting the actual performance of built landscape projects was identified by LAF as one of the top priorities for the landscape architecture discipline [8,30]. The CSI programme has been running annually since then to facilitate the transformation of the discipline. Throughout the past decade, the CSI programme has provided funding to approximately ten research teams per year. The teams include researchers, students, and landscape architecture practitioners, and they are tasked with measuring and documenting the performance of exemplary landscape projects all around the world. To date, the CSI programme has funded and facilitated the evaluations of more than 190 cases. Aside from its support for these standardised performance evaluations, the CSI has also funded research pertaining to evaluation frameworks and techniques. These collective endeavours have played a pivotal role in driving the rapid growth of the field of Landscape Performance Evaluation (LPE) over the past decade.

In July 2023, the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) announced that the United States Department of Homeland Security has officially designated degrees in landscape architecture as a Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) discipline [31,32,33]. This recognition highlights the importance and technical rigour of landscape architecture education and aligns it with other established STEM fields [31]. The positive impact of LPE in measuring the benefits of landscape architecture projects and enhancing disciplinary rigour has indisputably contributed to this milestone of the STEM accreditation. The designation is expected to have significant implications for the discipline, as it may open up new opportunities for research funding, professional development, and career pathways, thereby further exerting and leveraging the impacts of the discipline [31]. As the disciplinary rigour becomes more widely recognised and the LPE research methodology continues to mature, it is opportune to review and update the directions and challenges for future exploration of this subfield in the new era.

In 2021, we participated in the CSI programme as one of ten teams funded by the LAF. Ours was the first CSI evaluation project in New Zealand. With the support from the original landscape architecture firm, we measured the actual performance of Te Whāriki, a master-planned residential landscape featuring a multi-functional artificial wetland system by employing a range of adapted and newly developed evaluation methods. As hands-on participants in this research, we experienced first-hand the adaptation of conventional evaluation approaches as well as the exploration of the methodological frontiers. During this process, we gained practical insights into the new challenges faced by current LPE practices, as well as the potential future research directions. In this paper, we adopt a methodological reflexivity approach as outlined by Olmos-Vega et. al. [34], using our CSI exploration as a basis to critique and reflect upon the evaluation methodology employed. Our study intends to be reflexive, rather than evaluative. The outputs from this process are not meant to prove anything, but to offer a novel angle of viewing and understanding the current evaluation frameworks, approaches, and their limitations. This means that future research and observations are needed to verify and test our reflexive outputs, which are out of the scope of this study. By sharing these findings and reflections, we aim to catalyse further conversations concerning the current evaluation framework and methodological exploration, thereby contributing to its ongoing iteration and improvement.

2. Study Site

2.1. Te Whāriki Overview

Te Whāriki is a 58-hectare residential development located in Lincoln, Canterbury, Aotearoa New Zealand. This subdivision development is framed by a design vision that weaves together the bicultural heritage of Māori and European settlement histories with the ecological characteristics of the former farmland. Previously a Lincoln University dairy farm, the area has been reshaped into a high-amenity residential landscape, delivering a range of environmental, social, and economic benefits, supported by artificial wetlands, green corridors, stormwater infrastructure, and a network of open spaces.

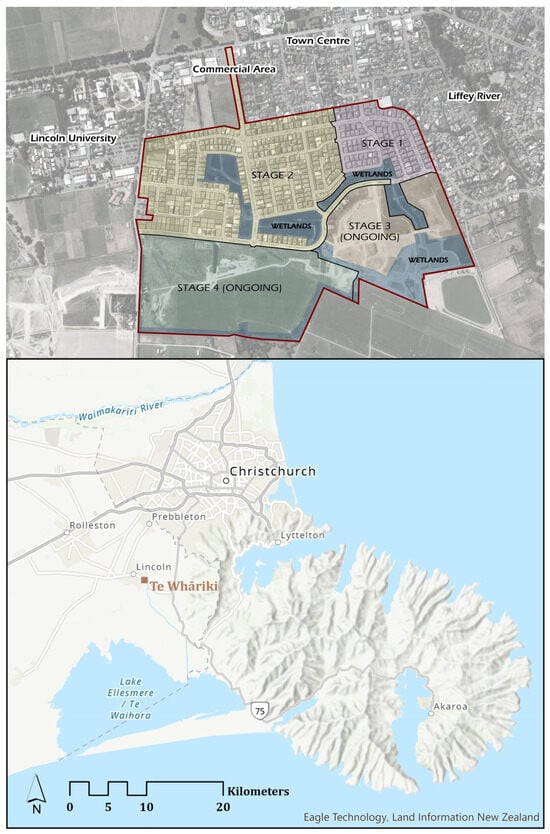

The subdivision development was staged (as shown in Figure 1). The areas being assessed by our case study are Stages 1 and 2. Figure 2 illustrates a typical landscape of the public open space of the Te Whāriki residential subdivision, Phases 1 and 2. The design of the subdivision featured restored historical waterways and a stormwater treatment system that was implemented with the intention of improving downstream water quality in Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere), one of New Zealand’s most heavily polluted yet culturally significant lakes located approximately 8 km away. Figure 1 illustrates the spatial context of Te Whāriki. Native plants that existed prior to the dairy-farming era were also reintroduced to re-establish wildlife habitat and strengthen ecological identity.

Figure 1.

A satellite map of the Te Whāriki residential subdivision as of November 2020, showing the stages of the development plan (NTS) (Top). The spatial context of the Te Whāriki residential subdivision (Bottom). (Adapted from Eagle Technology, Land Information New Zealand, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)).

Figure 2.

A typical landscape of the public open space of the Te Whāriki residential subdivision Phases 1 and 2, featuring artificial wetlands and a walking trail traversing the wetlands. (Image credit: Guanyu Chen, 2021).

The subdivision is used actively by local residents as well as the staff and students of the nearby university and schools. People engage with the space for recreation, exercise, food foraging, social gatherings, and a range of educational activities. Local schools, alongside university students, use the site for plant identification and as a field setting for studying stormwater management systems.

2.2. Landscape Features

In response to the vision for the subdivision, the design of Te Whāriki incorporates a range of landscape features. Central to the design is an integrated stormwater system intended to capture, filter, and detain runoff from roads and other hard surfaces. This network consists of rain gardens, street-centre swales, and a series of interconnected wetlands (as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). During a one-in-100-year flood event in 2021, these features functioned effectively: rain gardens and swales collected the runoff and mitigated overland flow, while the wetlands provided substantial temporary storage, preventing flooding of roads and dwellings (as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Street-centre swales and rain gardens provide a network for stormwater to pass through before entering the wetlands. (Image credit: Guanyu Chen, 2021).

Figure 4.

The rain gardens and swales performed effectively when the site experienced a one-in-100-year flood event in 2021 (Left). During a 100-year flood event, the wetlands were able to absorb a considerable amount of stormwater with no impact on roads or residences (Right). (Image credit: Jacky Bowring, 2021).

Covering approximately 14% of the entire development (8.3 ha or 20.5 acres in total), the wetlands support a broad range of species—including birds, insects, mollusks, and arachnids (Figure 5). An extensive path network runs around and through these wetlands, offering opportunities for walking, cycling, and wildlife watching.

Figure 5.

The interconnected wetlands within Te Whāriki support a range of wildlife. (Image credit: Guanyu Chen, 2021).

Food and fibre provision is another key landscape feature of the design. Pear, blueberry, and redcurrant trees are planted within an edible garden, alongside herbs, including rosemary, thyme, and sage, etc. There is also a garden dedicated to harakeke (Phormium spp.). Harakeke—distinct from European flax (Linum sp.)—holds deep cultural significance in Māori weaving traditions. These productive landscapes, together, echo the area’s agricultural history and provide residents with freely accessible food and fibre resources (as shown in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Residents and visitors are encouraged to harvest food and fibre from the landscape. The species captured in this image include Rosemary “Tuscan Blue”, Salvia officinalis, Feijoa “Apollo”, Pear “Double Worked”, and Malus “Jack Humm”. (Image credit: Earthwork Landscape Architects).

Cultural narratives are embedded in the design of Te Whāriki. The wetlands and harakeke gardens create a symbolic connection from the site to nearby Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere), which was historically an important mahinga kai landscape for local Māori. Since the mid-nineteenth century, when extensive agricultural practices were introduced with the arrival of European settlers, the surrounding land and waterways have been heavily degraded. Restoring the degraded water quality, now, holds vital significance—not only for community wellbeing but also for Māori cultural and spiritual identity, especially as wai is inherently tied to mahinga kai practices and to wairua, the soul or spirit.

The subdivision’s name, Te Whāriki—meaning “floor mat”—references traditional flax weaving. The design conceptualises the lakebed as a floor mat, acknowledging that Te Waihora once extended to the present-day subdivision boundary. This concept is expressed through the introduced wetlands and the overall design. The cultural narratives are illustrated in Te Whāriki’s playground. Figure 7 shows the playground that was themed Mahi Toi (arts and crafts). It also incorporates whāriki mats referenced through the raranga (weaving) paving pattern. This recollection and expression of continuity between the mat of the land and the lakebed symbolises how environmental stewardship at Te Whāriki positively influences the lake.

Figure 7.

Te Whāriki’s playground reinforces cultural narratives with the ‘whāriki’ mats referenced through the paving surface. (Image credit: Earthwork Landscape Architects).

Narratives of the local landscape are also reinforced through design interventions such as the gabions that draw on local geology, illustrating the underlying geomorphology across the area where alternating layers of alluvial and volcanic stone lie in varied configurations (as shown in Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Local geology is expressed through features like gabion baskets, which draw on local geology, illustrating the underlying geomorphology across the area where alternating layers of alluvial and volcanic stone lie in varied configurations. (Image credit: Earthwork Landscape Architects, 2020).

The design of Te Whāriki also acknowledges its historical ties to Lincoln University. Some streets in the subdivision are named in honour of notable university figures, such as Crowder Street, named after Bob Crowder, a pioneer in organic farming, and Goh Street, named after Kuan Goh, Emeritus Professor of Soil Science.

Some of the landscape features were designed to be more legible to the users of the landscape. Amenities such as the stormwater system, wetlands, and the harakeke garden communicate both cultural narratives and ecological processes in an observable way, creating learning opportunities for students from the nearby university and local schools. Interpretive signage positioned around the features further assists the wider community in appreciating the significance of these features (as shown in Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Interpretive signage provides residents and visitors with information about the planting and cultural context. (Image credit: Earthwork Landscape Architects).

Across the subdivision, a network of public open spaces, comprising playgrounds, productive gardens, cultural areas, and waterfront spaces, are linked by a series of trails. Together, these spaces provide residents with opportunities for exercise, play, food and fibre harvesting, and social interaction (as shown in Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The waterfront tracks of Te Whāriki provide local residents and visitors with an opportunity for physical exercise and play. (Image credit: Earthwork Landscape Architects).

3. Case Study Investigation—Measuring the Performance of Te Whāriki

This section summarises the methods and results of the performance evaluation we conducted as part of the 2021 CSI programme. This summary of methods and results contextualises our reflections, which are discussed in the next section. However, as a reflexive study (categorised using Deming and Swaffield [3]’s landscape architecture research classification scheme), the focus of this study is not on the specific evaluation methods, but rather on offering our reflections on the evaluation framework and methodology. The detailed assessment methods and results are documented in the original evaluation report [35], which elaborates on the methodology details of measuring a wide range of environmental, social, and economic benefits offered by Te Whāriki.

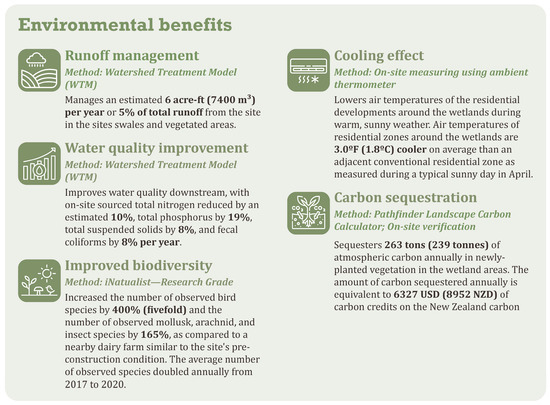

The environmental assessment focused on the creation of wetlands, stormwater systems, and green spaces in the Te Whāriki subdivision (as shown in Figure 11). Using tools like the Watershed Treatment Model (WTM) and Pathfinder Landscape Carbon Calculator, we calculated runoff management, water quality improvement, and atmospheric carbon sequestration. We also used iNaturalist as a crowdsourcing approach to assessing biodiversity changes. Our on-site measurement also provided evidence for the cooling effect of the wetlands.

Figure 11.

Environmental benefits of Te Whāriki landscape development.

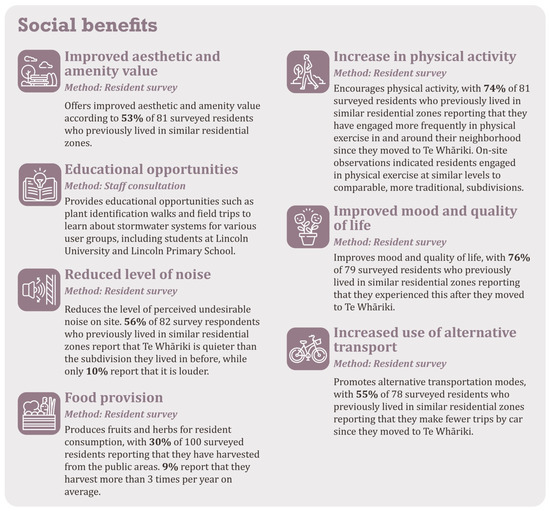

The social benefits assessment highlighted the subdivision’s role in providing a better living environment, as well as recreational, educational, and productive opportunities for local residents, and student and staff users from the nearby university and schools (as shown in Figure 12). These benefits were supported by the wetlands, a series of public open spaces, circulation networks, and edible gardens.

Figure 12.

Social benefits of Te Whāriki landscape development.

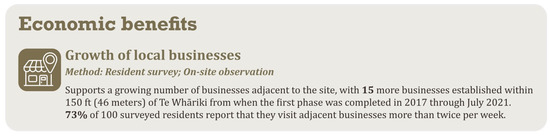

Economically, the development of the subdivision has resulted in a growing number of local businesses (as shown in Figure 13). Most of the surveyed local residents visit the businesses on a regular basis.

Figure 13.

Economic benefits of Te Whāriki landscape development.

The methods employed in this evaluation (as outlined in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, and further elaborated on in the original report) involved both estimation and measurement-based approaches to capture the multi-faceted performance of the Te Whāriki subdivision. Our findings indicate significant environmental, social, and economic benefits resulting from the integration of sustainable landscape practices and well-planned development. However, it is important to acknowledge that the benefits we evaluated are not exhaustive. Certain aspects, either deemed less significant or lacking sufficient data to support a legitimate evaluation, fall out of the scope of the original evaluation. Aspects such as the landscape premium reflected in real estate values or cost savings attributed to landscape resilience are both meaningful aspects of investigation in future research.

4. Reflections on the Current Performance Evaluation Framework

4.1. Methodological Reliability of Measured and Estimated Approaches

While many of the presented landscape benefits were quantified using measurement or observation-based approaches (e.g., temperature regulating benefits, increased physical activity presented, and improved mood and quality of life), some others were partially or fully based on estimation tools (e.g., runoff reduction and water quality improvement, and carbon sequestration). A common query that frequently arises pertains to the reliability of these estimation-based techniques. Addressing these inquiries necessitates an exploration of a conventional stereotype implicit in the posed questions, which posits that measurement or observation-based approaches exhibit higher levels of reliability compared to estimation-based methodologies.

In the process of designing our Case Study Investigation (CSI) evaluation methods, we critically analysed a range of published CSI cases. Some of the estimation-based assessments, particularly in the early years of the CSI programme, did exhibit a diminished level of reliability. For instance, in some of the cases, the estimation of landscape benefits hinged solely on data gleaned from design or construction documents, rendering their evaluation outcomes as projections of expected performance rather than reflective of actual performance. However, it is worth noting that in many of these cases, the challenges surrounding methodological reliability were not solely attributable to the process of estimation itself.

Estimation tools, at their core, are models that simulate real-world landscape processes. The reliability of these models varies depending on how accurately they replicate natural phenomena. It is crucial to recognise that, like other evaluation methods, such as observations and measurements, estimation tools inherently possess a margin of error. The methodological reliability of employing surveys, interviews, or observations relies on statistical principles, especially when dealing with populations too vast to study comprehensively. Even when drawing conclusions from a representative sample, there remains a margin of error. Adherence to statistical requirements can mitigate this error to an acceptable level, but it cannot be entirely eliminated. For example, as elaborated in the original report on the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC) observation, the observations presented also exhibit their share of methodological limitations. The quality of observations depends on factors like the procedural approach, the duration and scope of observation, and other factors. Consequently, observations can only offer glimpses of a project’s actual performance, and when conducted diligently, can offer a representation closely mirroring reality but not identical to it. Similarly, as detailed in the original report about the cooling effect, the reliability of the measurements conducted to quantify the cooling effects of Te Whāriki was also constrained by the limited temporal and physical ranges of the measurements and the interference from a range of factors.

Landscapes are very complex living systems. This inherent nature implies that complete certainty will not be an achievable goal for landscape performance evaluations, and there will always be certain levels of “estimations” and “hypotheses”, such as the system remains the same today and tomorrow, or one part of the landscape is the same as the other part of it. This echoes a view presented by Chen, Bowring and Davis [29]—the LPE practices historically stemmed from similar architectural practices evaluating how built projects perform, but more attention needs to be paid to the contextual differences between landscape architecture and architecture during the process of interdisciplinary conceptual adoption. Buildings, in contrast to landscapes, are often surrounded by walls and have a more controlled environment, which makes their performance more predictable, providing a higher level of certainty for Building Performance Evaluations (BPE). On the contrary, landscapes are often open systems, i.e., one landscape is often interconnected and interactive with its surrounding landscapes, and the impacts of landscape design interventions often do not stop at their boundary. Being an open system also means there are substances and energy constantly flowing in and out of the system—in other words, there are often significantly more interfering factors (including abiotic factors like wind, light, temperature, water, and biotic factors like animals and plants) influencing its performance, and the magnitude of interference is often much more significant than systems like a building. The mixture of periodic and non-periodic changes in interfering factors makes the performance of landscapes less predictable, meaning that each “snapshot” taken for their performance is less representative than the ones for a building. Measuring the performance of a highly dynamic and complex system means that the same level of certainty and accuracy that BPE aspires for may not always be achievable, or in some cases, can only be achieved at a higher cost.

We argue that in the field of LPE, due to the dynamics and complexity of landscape systems, evaluation approaches cannot be dichotomously categorised into “estimated” and “measured”, perceiving that the former is less reliable than the latter (even if it may be true for BPEs). Rather, the reliability of evaluation approaches can be conceptualised as a continuous spectrum, on which different types of estimation and measurement-based performance are crosswise distributed.

4.2. Towards a More Accurate and Reliable Estimation

As discussed, estimation tools, at their core, are models that simulate real-world landscape processes. For example, as detailed in the original report, we calculated the water quality improvement and on-site runoff reduction by using the Watershed Treatment Model (WTM), a benefit-simulating model, which is commonly used for water quality management. This model requires a range of input data, including the size of the project’s catchment area, the type and size of green-blue infrastructures, treatment practices, etc. Based on the input information, the model can provide expected values indicating the design interventions’ impacts on water quality by simulating the water treatment processes. Similarly, as detailed in the original report, we calculated the amount of atmospheric carbon that can be sequestered by the landscapes in Te Whāriki each year by using the Pathfinder Landscape Carbon Calculator (PLCC), an online tool, into which the type and number of plants are inputted to calculate an indicative value of carbon sequestration.

As acknowledged in the original report—PLCC, the PLCC model was developed based on general plant types (e.g., evergreen tree, deciduous tree, evergreen shrub, deciduous shrub, wetlands, and lawn) and their general sizes (e.g., large, medium, and small (categorised based on the mature height of plants)). This coarse-grained simulation, while simplifying the complexity of reality and making the model easier to use, undoubtedly leaves out many details, lowering the accuracy of the estimation. However, the PLCC model has been iterated over the years to improve its accuracy. By 2023, many more plant categories had been added to the model, including perennial grasses, temperate forests, tropical forests, and boreal forests, in comparison to 2021 when the Te Whāriki evaluation was conducted. These finer-grained inputs will no doubt improve the quality of the estimation model by allowing a more accurate simulation, which eventually contributes to the accuracy and reliability of the evaluation results.

Apart from the quality of models, the quality of inputs is another key factor determining the quality of estimation results. As elucidated in the prior section, the performance estimations conducted in some of the past CSI cases were solely reliant on data extracted from design or construction documents. This approach renders the evaluation outcomes more akin to forecasts of expected performance rather than a true reflection of actual performance. For instance, in the process of studying past CSI cases, we found that some evaluations input the information sourced from the original planting plans into the PLCC model to estimate the projects’ carbon sequestration performance, even if many years have passed since the projects’ completion.

In our evaluation, we aimed to improve the quality of the estimation by feeding the same model with more reliable input data. Instead of inputting the type and number of plants directly from the original planting plan, we checked the plants on-site to inventory how they had been coping with the environment, responding to the maintenance practices, and whether they were performing as they were expected. The inventory result in Table 1 shows that there is a considerable gap between the expected and the actual number of plants. About one-third of the plants were no longer present or had been replaced by different species, and some were very stunted in their growth. As a result, the actual carbon sequestration is a quarter lower than the value that can be calculated by solely using the information sourced from the original planting plan, as shown in Table 1. This result indicates that the quality of inputs can have a significant impact on the accuracy or reliability of the estimations.

Table 1.

Comparison of the actual and planned number of plants and the amount of their annual carbon sequestration.

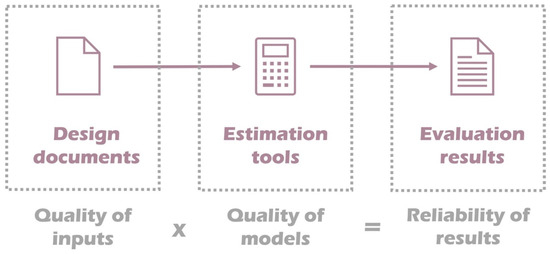

Based on the discussion above, we argue that the reliability of estimation results can be conceptualised as a function of the quality of the inputs and the quality of the estimation model, with which the reliability of the estimation is directly correlated (as shown in Figure 14). While the scale of impact that model quality may have on the reliability of the results was not examined by this study, our findings do highlight that attention needs to be drawn to the quality of inputs and their impacts on the evaluation results. Also, in comparison to improving the estimation model, improving the quality of the inputs may be a lower-hanging fruit for landscape performance evaluators to pursue in such cases.

Figure 14.

The reliability of estimation results can be conceptualised as a function of the quality of the inputs and the quality of the estimation model, with which the reliability of the estimation is directly correlated.

Guarding against bias for input quality control requires making all underlying assumptions explicit. In estimation-based evaluation, there are typically two key assumptions: (1) that the estimation tools appropriately represent real-world processes, and (2) that the input data accurately reflect site conditions. In practice, these assumptions should be checked on a case-by-case basis where possible.

For example, in our case, if the carbon sequestration assessment relies solely on planting plans from the original design documents, the implicit assumption would be that all plants have been put in place perfectly as what was planned and all of them have coped well and are still alive in a reasonable condition—an assumption that may or may not be true, depending on how well the landscape was designed and managed. In such a case, a plant audit would therefore be useful to test or reduce input bias. As another example, when hedonic modelling is used to assess perceived socio-cultural benefits, input quality would really depend on factors such as data representativeness, sample size, variable selection, and data cleaning procedures, etc. These forms of quality control are largely determined by the specific statistical techniques and data sources used.

The conceptual model of estimation reliability presented above is instrumental for understanding the key contributors to reliability, but its practical application will vary by context. In summary, transparency about assumptions, appropriate data-quality checks, and methodological common sense are essential safeguards against introducing bias.

4.3. Accuracy vs. Cost

As previously discussed, due to the dynamics and complexity of landscape systems, it is often very challenging for an LPE to achieve the same level of accuracy as a BPE, or, while possible, often at a higher cost (i.e., taking more effort and resources). However, it is essential to recognise that the value of an evaluation, or in other words, the overall positive impacts derived from an evaluation (including learning from past projects, helping communicate the contribution of a design, providing evidence for decision-making, etc.) is not infinite. This means that in order to ensure an evaluation is worthwhile, accuracy must not be the only dimension for judging the quality and effectiveness of an evaluation. It is also crucial to view an evaluation through a multidimensional lens, weighing the marginal benefits of enhancing evaluation accuracy.

There is normally more than one way to improve the accuracy of an evaluation. Taking the case of carbon calculation as an example again, in order to improve the evaluation quality, we can check the plant condition to make the input more accurate or improve the model by making the simulation finer-grained. There are also ways to further improve the evaluation accuracy, for example, it is possible to measure the size of each plant and differentiate their carbon storage ability according to their species, and it is even possible to carry out experiments to measure the amount of carbon sequestration. However, such degrees of accuracy would come at a huge cost, and the key is to find a “sweet spot” or the equilibrium point between accuracy and cost and to strategically maximise the overall effectiveness of evaluations. Identifying the lower-hanging fruits and taking action accordingly, as argued previously, therefore, is vital to the success and continued improvement of an evaluation. Looking ahead, emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence may shift this equilibrium by enabling higher accuracy at reduced cost, and thereby pushing the equilibrium towards the direction of more cost-effective evaluations, which offer exciting opportunities for future research.

4.4. Universal Currency for Landscape Benefits

Our final reflection is about the overall Landscape Performance Evaluation framework in its current form. The evolution of the Landscape Performance Evaluation framework over the past decade is a significant achievement, offering a considerable expansion in the range of tools and making it possible to quantify a wide range of landscape benefits. However, even with all of the data that has been generated, is it possible to answer the question—“How successful is a landscape development”?

The landscape we evaluated is estimated to save 239 tons of carbon each year. The result sounds very attractive. But, if we can, for example, make 50% of residents happier by spending the same amount of money or resources on recreation opportunities, or reduce 50% of the annual runoff by investing in stormwater facilities, would that be a better option? With the numbers we achieved from our CSI evaluation, it is still a very difficult question to answer, because the quantified benefits are measured using different “currencies”, with different units. The data cannot convey how significantly those benefits can contribute to wellbeing, the ultimate goal of landscape development.

Secondly, every benefit gained from a built landscape comes at a certain cost. With our current evaluation techniques, associating the benefits with their costs remains a formidable task. It is noteworthy that the considerations of benefits and costs extend beyond mere market values, encompassing non-market values as well. The consideration related to the cost–benefit comparison leads to the third challenge.

In practice, there are always limited resources, such as money and time. A key question that landscape architects and decision-makers are facing every day is, with limited resources, which benefits should be invested in, and how better decisions can be made to maximise the overall contributions that landscapes can make to wellbeing.

We argue that one of the key actions that LPE researchers should take to further advance the field is to develop a universal currency, with which landscape benefits and costs can be measured and compared. With the universal currency, LPEs will then be able to answer the three questions that we raised above, to which landscape architects and decision-makers urgently need answers.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study delves into the methodological reliability of both “measured” and “estimated” approaches in the context of LPE. We argued that, unlike buildings, landscapes are highly complex and open systems, which makes achieving the same level of certainty and accuracy as BPE a challenging endeavour.

Our study also challenges the common stereotype that “measured” approaches are inherently more reliable than “estimated” ones. The reliability of LPE approaches is depicted as a continuous spectrum where different methods are crosswise distributed.

This paper also emphasises the importance of improving the quality of inputs in estimation-based evaluations. It demonstrates how a discrepancy between expected and actual plant conditions significantly affected the accuracy and reliability of estimations. This underscores that while improving estimation models is crucial, enhancing input data quality, in some cases, may be a more attainable and effective means of enhancing reliability.

Furthermore, our study also explores the trade-off between accuracy and cost in LPE. The complexity of landscape systems makes achieving high levels of accuracy a resource-intensive task. Balancing the level of accuracy with the available resources is imperative. We argue that identifying “lower-hanging fruit” in terms of accuracy improvements is a strategic approach.

Finally, this article introduces the concept of a universal currency for landscape benefits, which aims to address the challenge of comparing the value of different landscape benefits, as well as comparing the benefits to the costs. By developing such a universal metric, the LPE community could better evaluate the contributions of landscape projects to human well-being and assess the relationship between benefits and costs, aiding landscape architects and decision-makers in making informed choices. This reflexive study also identifies promising directions for future research, including the development of a “universal currency” for comparing diverse landscape benefits, as well as for assessing benefits relative to costs. Our discussion on the equilibrium between evaluation accuracy and resource investment also underscores the potential role of emerging technologies—particularly artificial intelligence—in landscape performance evaluation (LPE). These innovations may help shift the accuracy–cost balance toward a more cost-effective direction, reinforcing the need to critically explore their prospective impact on the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.B. and G.C.; methodology, G.C., J.B. and S.D.; software, G.C.; formal analysis, G.C. and J.B.; investigation, G.C. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, G.C., J.B. and S.D.; visualisation, G.C.; supervision, J.B. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication has been partially financed by the Case Study Investigation (CSI) programme of the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF), the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects Vectorworks Landmark Scholarship, and Lincoln University Faculty of Environment, Society and Design Writing Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Lincoln University Human Ethics Committee (Application No: 2021-12) on 1 April 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions, but may be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Egoz, S. Landscape Is More Than the Sum of Its Parts: Teaching an Understanding of Landscape Complexity, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Sarlöv Herlin, I.; Stiles, R. Exploring the Boundaries of Landscape Architecture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, M.E.; Swaffield, S. Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.; Thompson, I.; Waterton, E.; Atha, M. The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, I.H. Landscape Architecture: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, J.; Yang, B.; Whitlow, H. Evaluating Landscape Performance—A Guidebook for Metrics and Methods Selection; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. About Landscape Performance. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/about-landscape-performance (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Barnes, M. Evaluating Landscape Performance; Land F/X: San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B. Landscape performance evaluation in socio-ecological practice: Current status and prospects. Socio Ecol. Pract. Res. 2020, 2, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, S.; Binder, C. Economic benefits: Metrics and methods for landscape performance assessment. Sustainability 2016, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, M.E. Social & cultural metrics: Measuring the intangible benefits of designed landscapes. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 1, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, S.; Binder, C. A research frontier in landscape architecture: Landscape performance and assessment of social benefits. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdil, T.R. Economic Value of Urban Design; VDM Publishing: Munich, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdil, T.R. Social value of urban landscapes: Performance study lessons from two iconic Texas projects. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2016, 4, 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdil, T.R.; Stewart, D.M. Assessing economic performance of landscape architecture projects: Lessons learned from Texas case studies. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 1, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ametepey, S.O.; Ansah, S.K. Impacts of construction activities on the environment: The case of Ghana. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 2014, 4, 934–948. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, C. The carbon landscape. Topos 2008, 61, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, C. The carbon landscape policy—The development of an IFLA climate change action plan. In Proceedings of the IFLA 54th World Council, Montreal, QC, Canada, 27 September 2017; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, C. The Carbon Landscape Theory. Available online: http://www.carbonlandscape.com/carbon-road-show.html (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Bowring, J.; MacKay, M. Landscapes that last? In Landscape New Zealand; Craig Potton Publishing: Nelson, New Zealand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, M. The Social Dimensions of Landscape Sustainability; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Egoz, S.; Makhzoumi, J.; Pungetti, G. The Right to Landscape: Contesting Landscape and Human Rights; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK; Florence, Italy; London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Anderson, C.; Zakariya, K. Framed to Be Open: Exploring the Strategies of Planning University Campuses in China. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2013, 1, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Anderson, C. From line to thickness: Strategies and tactics for reviving marginal space. In LA China—Landscape Architecture China: Reviving Derelict Sites; Chinese Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage Books ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gillham, O. The Limitless City: A Primer on the Urban Sprawl Debate; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Liu, Z.; Tian, J.; Ma, Q. Urban expansion dynamics and natural habitat loss in China: A multiscale landscape perspective. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 2886–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Bowring, J.; Davis, S. Exploring the terminology, definitions, and forms of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) in landscape architecture. Land 2023, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. Landscape Performance Series Turns 10. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/blog/2020/09/landscape-performance-turns-10 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Niland, J. Landscape Architecture Is Now Officially A STEM Discipline. Available online: https://archinect.com/news/article/150356461/landscape-architecture-is-now-officially-a-stem-discipline-according-to-the-u-s-department-of-homeland-security (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Brodka, C. Why Landscape Architecture Matters Now More than Ever. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/1004201/why-landscape-architecture-matters-now-more-than-ever (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- American Society of Landscape Architects. Become A Landscape Architect—Landscape Architecture: A STEM Profession. Available online: https://www.asla.org/ContentDetail.aspx?id=57146 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med. Teach. 2023, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowring, J.; Chen, G. Te Whāriki Subdivision Phases 1 and 2 methods. In Landscape Performance Series; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).