Abstract

Folk festivals and other intangible cultural heritage have received widespread attention, and their socio-cultural value can be used to promote tourism, strengthen local identity, and build city brands. However, it remains unclear how these intangible cultural heritage festivals transform their multi-dimensional and multi-configuration material characteristics into economic benefits and image enhancement. This study proposes a practical decision-making framework aimed at understanding how different festival design and governance strategies can work synergistically under different cultural conditions. Based primarily on a literature review and expert questionnaire survey, this study identified six stable materialized practice modules: productization, spatialization, experientialization, digitalization, branding/communication, and co-creation governance. At the same time, this framework also incorporates two other conditional intervention properties: classicism and novelty. The interactions between these modules shape people’s understanding of intangible cultural heritage festivals. Subsequently, this study used a multimodal national dataset that included official statistics, industry reports, e-commerce and social media data, questionnaires, and expert ratings to construct module scores and cultural attributes for 167 festival case studies. Through rough set analysis (RSA), this study simplifies the attributes and extracts clear “if-then” rules, establishing a configurational causal relationship between module configuration and classic/novel conditions to form high economic benefits and enhance local image. The findings of this study reveal a robust core built around spatialization, digitalization, and co-creative governance, with brand promotion/communication yielding benefits depending on the specific context. This further confirms that classicism reinforces the legitimacy and effectiveness of rituals/spaces and governance pathways, while novelty amplifies the impact of digitalization and immersive interaction. In summary, this study constructs an integrated and easy-to-understand process that links indicators, weights, and rules, and provides operational support for screening schemes and resource allocation in festival event combinations and venue brand governance.

1. Introduction

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) embodies cultural identity, community memory and place-brand equity. In the form of folk festivals, performances, rituals, foodways and crafts are brought together into cultural scenes that can be seen, participated in, transacted and disseminated. Recent reviews show that research on ICH tourism has moved beyond early work on resource inventory and preservation towards questions of impact evaluation, tourist behaviour and destination marketing, with “social practice, ritual and festival events” emerging as core topics [1]. Meanwhile, the commercialisation/commodification of festivals does not necessarily erode cultural meaning; rather, through re-interpretation it may generate new meanings. Since Cohen [2] advanced the debate on ‘authenticity and commoditisation’, scholars have continued to examine the dialectical relationship between commodification and cultural value, providing deeper theoretical grounding for balancing protection and use in contemporary local governance.

Based on this, recent heritage research emphasizes that intangible cultural heritage is not only a collection of “intangible” meanings, but also constantly materialized through festivals, performances, cultural and creative products, digital platforms, and governance mechanisms [3]. In this sense, materialization refers to the repeated practice of narratives, rituals, and skills being transformed into spatial environments, infrastructure, marketable products, and institutional rules. Therefore, UNESCO’s conservation framework and local policy tools can be understood as part of a broader process of materialization in which cultural memory is stabilized, presented, and disseminated through specific socio-technical configurations.

In China’s urban and rural development, intangible cultural heritage in the form of folk festivals is not only an engine for urban tourism but also a key element in shaping urban brands. Festivals and events can enhance a destination’s visibility, attract tourists, increase their willingness to return, and generate positive word-of-mouth. Real-world experience shows that, when carefully planned as a combination of annual events, it can also contribute to the long-term development of a city’s brand [4,5]. Several research directions have been developed around these practices, mainly focusing on the following aspects: commercialization and intellectual property licensing of cultural and creative products; spatial design and exhibition of festival scenes; interactive and immersive experience forms; digital interventions such as augmented reality/virtual reality, live streaming and social media interaction; and governance involving residents, cultural heritage inheritors and local businesses [6]. From the perspective of environmental design and governance research, the above research threads all point to the same question: how exactly are intangible cultural heritage festivals “embodied/materialized” into a perceptible, manageable, and governable environmental system? In other words, folk festivals do not occur in a vacuum, but are embedded in a specific material and institutional environment: on the one hand, they rely on spatial carriers such as streets, squares, stages, and temporary installations, as well as built environments such as lighting, sound, and infrastructure. On the other hand, through cultural and creative products and derivative goods, digital interfaces and platform mechanisms, as well as a whole set of institutional arrangements and governance rules, they are constantly translated into “festival scenes” that can be consumed, experienced and managed.

However, existing research shows that these seemingly diverse paths still exhibit a high degree of fragmentation. Research on cultural and creative products and the IP economy often focuses on the value transformation and revenue distribution at the commodity level [7]. Research on intangible cultural heritage scene design and scene creation focuses on the relationship between place imagery and behavioral patterns [8]. Many studies also focus on exploring the impact of interactive and immersive experiences in intangible cultural heritage festivals on tourists’ emotional responses and visitor satisfaction [9]. Studies on digital intervention often use online traffic and brand exposure as the main indicators [10]. While these tasks are indeed in-depth in their own way, they often take a single module as the unit of analysis and lack a systemic perspective that can integrate different elements and observe the logic of their combined operation. In other words, we do not yet fully understand what analyzable components make up the material environment of ICH festivals, how these components are combined, superimposed, and selected in practice, and under what conditions different configurations will lead to different economic effects and urban image expressions.

On the other hand, although the discussion on the tension between the “authenticity” and “innovation” of festivals is quite rich at the theoretical level, it has rarely been systematically introduced into the above-mentioned material environment analysis [11]. Since Cohen [2], scholars have repeatedly pointed out that tourists’ evaluation of festivals does not only reflect their objective design, but is also deeply shaped by their subjective judgments of “classic”, “orthodox”, and “innovative and novel”. On the one hand, factors such as the integrity of the rituals, lineage, and official recognition can make the festival perceived as more “classic” and culturally legitimate. On the other hand, cross-border collaborations, digital immersion, and youth-oriented formats make the festivals seem “creative” and novel [12]. However, existing empirical studies mostly describe this tension in individual cases or on a single surface, and rarely use “classicism” and “novelty” as operational judgment dimensions to examine how they intervene in and change the mechanisms of action of different material environmental factors. For example, in highly classic festivals, are certain spatial and governance configurations more likely to gain recognition and support? In highly innovative festivals, are digital interventions and experience design more crucial to their economic impact? These issues have not yet been systematically compared and verified in existing literature.

Summing up, this study asks: how do local governments and communities translate cultural value through different materialisation practice modules; and how do classicity and novelty, as moderating factors, shape the effects of these module configurations on place image and economic outcomes? Specifically, we address:

- (1)

- In the development of local folk-festival cultural initiatives, which materialisation practice modules are widely adopted, and how can these modules be operationalised and assembled into an analytical framework?

- (2)

- How do classicity and novelty influence the effectiveness of the above modules? More precisely, which interaction configurations constitute the critical conditions for festival success?

- (3)

- How do different configurations of conditions lead to high economic impact and enhanced place image, and do multiple equivalent pathways exist?

The purpose of this study is to provide a systematic analysis of the value-transformation mechanisms through which China’s folk-festival forms of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) contribute to urban development. The specific objectives are: (1) to identify and quantify ICH materialisation practice modules and to construct an analytical framework; (2) to examine how classicity and novelty, as moderating dimensions, influence the marginal effects of different modules; and (3) to uncover the plural rules and threshold conditions under which various module configurations, in conjunction with C/N moderation, lead to high economic impact and enhanced place image. To address these gaps, the study designs a multi-case, multi-factor configurational framework, combining the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM) with Rough Set Analysis (RSA). In summary, the main contribution of this study is the development of an integrated fuzzy Delphi-rough set analysis process that integrates indicators, weights, and “If…Then…” rules into an interpretable multi-attribute decision-making framework, supplemented by uncertainty and robustness tests. Furthermore, this study provides operational decision support for local governments and planners to design combinations of intangible cultural heritage festival activities and allocate resources by identifying clear threshold conditions and multiple feasible paths, in order to enhance economic impact and city image. To achieve the objectives of this study, the research design includes three phases. First, through literature review and practical research, this study preliminarily defines the material practice modules of ICH, as well as the two cultural adjustment dimensions of classicism and novelty. We further invited experts such as intangible cultural heritage scholars, local cultural and tourism managers, festival planners and inheritors to use the FDM convergence index system and determine the weights. Then, representative Chinese folk festivals were selected to construct a multi-case sample. The data encompasses both objective and subjective data. The indicators of each module are standardized and synthesized to form six module scores and a cultural attribute score (C/N). Interactive conditional attributes are constructed to examine the moderating effect of cultural traits. Finally, this study uses module scores and interaction attributes as conditional attributes, and “high economic impact” and “enhanced local image” as decision attributes. It uses RSA to extract causal rules, revealing how different combinations lead to multiple outcomes, and examines whether there is equifinality.

2. Previous Works

With the rise of the concept of cultural sustainability, intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is increasingly being repositioned as an important engine driving local economies and urban image, rather than just a passively preserved carrier of cultural resources. Related research has gradually shifted from early resource surveys and protection planning to issues such as impact assessment, tourist behavior and destination marketing, and regards social practices, ceremonies and festivals as one of the core forms of ICH presentation. Recent research further suggests that future research agendas need to respond in an integrated manner to the complex relationship between place-making, technological mediation, and environmental context, rather than treating them in isolation [1]. Within this framework, scholars argue that ICH is not only a “continuation of cultural memory”, but a dynamic process of being “materialized” through festivals, performances and cultural and creative practices, and is closely intertwined with multi-level policy and governance frameworks such as UNESCO [13]. In the context of rapid urbanization and cultural tourism, the research focus has shifted from one-dimensional “protection discourse” to “value creation”, paying attention to how reproduction, reinterpretation and reuse constitute a cultural-economic “transformation chain”, and extending to issues such as cultural governance, urban branding and community co-management [14].

The existing literature can be broadly summarised into three complementary theoretical lines. First, the cultural and experience economy perspective emphasises value transformation centred on experience and is widely used in management and tourism research, arguing that well-designed cultural experiences can transform symbolic capital into economic value [15]. Second, studies on local dependence and city branding explain how cultural representation shapes collective identity, city brand image, and the interactions and power games among stakeholders [16]. Third, research on cultural governance and value co-creation highlights that value is not produced by a single supplier, but is jointly generated through interactions among multiple actors across policy, institutional, and market arenas [17]. Taken together, these three lines of research provide the theoretical foundation for this study. Building on them, we develop an analytical framework that links ICH festivals, local imagery, and economic benefits through the notion of “materialised practice modules”. A detailed explanation of this framework and the rationale for selecting its constituent elements is presented in Section 3.1.

In terms of specific types, folk festival-type ICH, as the most visible and participatory form of heritage presentation, is widely regarded as a key link connecting cultural heritage, industrial development and local identity [18]. Existing research shows that festivals can boost the local economy, stimulate consumption and create job opportunities through cultural tourism and creative industries [19]. In recent years, the introduction of digital media and e-commerce platforms has further amplified the market spillover effect, gradually transforming ICH festivals from being mainly “local activities” into “cultural brand products” that can be widely circulated. At the same time, festivals are increasingly seen as a symbolic carrier of city brand and cultural identity. Local governments often use curatorial and event combinations to re-present regional culture, deepen local identity and cultivate citizens’ pride. However, scholars have repeatedly pointed out that there is a continuous tension between “local authenticity” and “innovation/digitalization” in festival governance and urban branding practice. That is, how to promote creative renewal and digital transformation without diluting traditional credibility is an important challenge facing local branding strategies at present [20].

It is worth noting that this tension is often understood in most studies as a linear or binary “trade-off,” and less frequently as a dynamic, oscillating relationship that can be finely theorized. To address this tension more precisely, this study introduces a new theoretical perspective from contemporary social science—metamodernism. The theory argues that contemporary cultural practices often oscillate between seemingly opposing extremes and form higher-level value structures through sublation/dialectical integration. Cultural phenomena are simultaneously a material-semiotics structure, interwoven with matter and symbols, and are “anchored” in institutions and daily practices as social types with stable recognition [21,22]. From this perspective, this study reconstructs the “classicism-novelty” relationship in ICH festivals from a simple linear tug-of-war into a dialectical system that continuously oscillates and is reorganized in time and space. In other words, classicism and novelty do not simply add a contextual variable to explain variation, but rather change the marginal effects of each module on economic impact and local imagery. Therefore, they are designed in this study as moderating conditions to characterize different cultural contexts.

In terms of specific conceptualization, this study further constructs ICH festivals as a materialized system consisting of three dimensions: scene, digital, and governance. Among them, the scene dimension refers to the spatial layout, landscape installations, ritual performances and atmosphere creation of the festival, emphasizing how embodied experience and symbolic codes intertwine to form a “perceptible cultural scene” [23]. During measurement, encoding can be performed using indicators such as spatial structure complexity, cultural symbol density, ritual intensity, and circulation design. Digital dimension refers to the overall configuration of festivals through digital media, immersive devices, live streaming, and social media platforms, including the completeness of digital facilities, exposure on multiple platforms, UGC volume, and e-commerce traffic mechanisms [24]. Finally, the governance dimension encompasses the collaborative governance mechanisms among government departments, cultural institutions, communities, and market entities during festivals, including policy support levels, resource allocation methods, co-creation platforms, and risk management systems [25]. In metamodern’s understanding, these three are not three separate variables, but rather a triple material–symbolic practice field that spans the natural, social, and technological levels, and presents different configuration forms under different combinations of classicism and novelty. In other words, each “materialized practice module” can be seen as the result of rearranging scene-digital-governance in a specific way along the classicity-novelty axis.

Specifically, this study defines classicity as the extent to which a festival anchors itself to existing ritual structures, historical narratives, and institutional recognition in order to establish cultural legitimacy and social trust. This includes aspects such as ritual integrity, historical continuity, intangible cultural heritage certification levels, lineage of inheritors, and local community participation. Novelty refers to the ability of festivals to expand their reach, update their interpretive framework, and attract new audiences through innovative formats, cross-disciplinary content, and digital media, including immersive scenarios, cross-disciplinary collaborations, youth-oriented event design, and the integration of social media and e-commerce. At the operational level, this study views classicity and novelty as continuous, multi-indicator constructs rather than binary classifications: classicity will be weighted by indicators such as historical depth and continuity, ritual integrity, certification and protection level, and visibility of inheritors and community organizations. Novelty comprises indicators such as new event formats and scene design, the introduction of immersive and interactive technologies, cross-cultural/cross-industry collaboration, and online traffic and conversion mechanisms. The above indicators are quantified by combining textual and visual data with expert scores, and construct validity is improved through expert consistency tests and cross-case comparisons. Furthermore, to avoid misinterpreting “classicism” and “novelty” as inherent attributes of the festival itself, this study adopts the views of Storm [21] and Matlovič and Matlovičová [22], regarding them as social kinds that have gradually stabilized through multiple “anchoring mechanisms”. Specifically, this article distinguishes three anchoring methods: (1) dynamic-nominalist anchoring, which refers to defining what is considered orthodox and classic by means of labels, recognition systems and ritual paradigms, such as UNESCO/national intangible cultural heritage, official protection levels, and ritual scripts that have been codified into the canon. (2) mimetic anchoring refers to different cities or organizers replicating the appearance of a certain kind of festival by imitating existing successful paradigms (such as scene design, program arrangement and cross-city event format). (3) Ergonic anchoring is the accumulation of material infrastructure and technology to make a certain festival practice stable and repeatable in a specific venue and hardware environment, such as fixed festival squares, lighting and sound equipment and live broadcast equipment configuration.

At the methodological level, most previous studies have used regression models or structural equation models to estimate the average effect of independent variables on dependent variables [26]. While such research designs are valuable in verifying established hypotheses, they are less able to fully capture the “combinatorial causality” and multiple equifinalities/multipath equifinalities that are common in complex urban contexts. Therefore, recent event tourism research calls for an approach that can extract transparent and interpretable decision rules from multiple attribute combinations, rather than viewing various driving factors in isolation [27]. Against this backdrop, this study argues that configuration methods such as Rough Set Analysis (RSA) provide important supplements: they can extract If…Then… rules such as “if A and B and not C, then high performance can be achieved” from real-world cases, identify “core conditions” and “marginal conditions”, and are highly relevant to festival planning and design decisions.

Although there is a wealth of empirical research on “authenticity,” “typicality,” and “innovation,” there is still a lack of consensus in the literature on how to consistently and comparablely measure these constructs across case contexts. In particular, classicism often remains at the conceptual level (such as ritual integrity, certified status, and lineage of successors), while novelty is often temporarily replaced by “one-off creative elements,” “digital spectacles,” or “youth-oriented activities.” Similarly, most studies on the relationship between scenario, digital, and governance are presented in a descriptive manner, lacking quantifiable and combinatorial tools to support decision-making. In summary, this study introduces the perspective of metamodernism’s oscillation and sublation at the theoretical level, reconstructing classicity–novelty and scene–digital–governance into a dynamic, dialectical, and configurable materialized system. On the other hand, at the methodological level, through interpretable configuration methods such as rough sets, a set of construct indicators and If…Then… decision rules that can be compared across cases are established. It is hoped that at the intersection of ICH governance, festival portfolio planning and explanatory decision analysis, the shortcomings of existing research in terms of theoretical depth, construct validity and methodological transparency can be made up for.

3. Methodology and Steps

3.1. Analytical Framework and Research Design

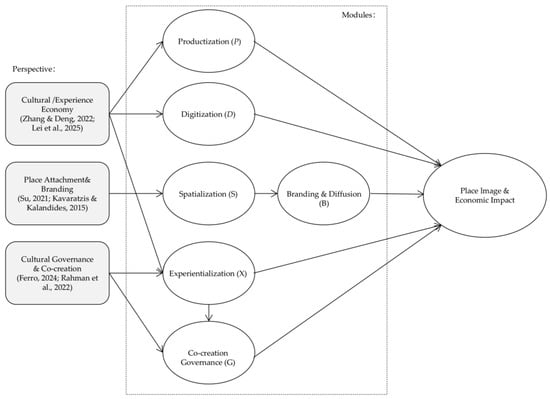

Based on a review of relevant literature, this study found that scholars generally use the perspectives of cultural/experience economy, place attachment and place branding, as well as cultural governance and co-creation to explain the impact of the composition and organizational characteristics of intangible cultural heritage festivals on local image and economy [11,12,13]. In this study, the elements or attributes that enable intangible cultural heritage festivals to be transformed into specific products, spaces, experiences, and governance arrangements that can create cultural and economic value are considered as ICH materialization modules (As shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of ICH festival modules and place image & economic impact [11,12,13,15,16,28].

From the perspective of culture and the experience economy, contemporary cultural activities create value primarily by crafting memorable experiences, rather than simply providing services or goods [15]. Some scholars have found through empirical research that innovations in program design, dramatic structure and service interaction can enhance tourists’ perception of authenticity and subjective well-being, but if the experience design is entirely driven by market logic, it may also increase the risk of cultural distortion [11,15]. First, the Production (P) module reflects the pathways through which symbolic cultural capital is transformed into economic value through product design and pricing strategies, referring to how ICH-related rituals, crafts, and performances are packaged into repeatable and tradable products [11,15]. In addition, to help intangible cultural heritage festivals reach a wider audience, accumulate data, and build lasting interactions, modules that use digital media and information technology to expand and enhance the festival experience are categorized as digitalization (D). Research on technology-enabled festival marketing shows that such innovations have become a key tool for destination branding and are used to build multi-stage visitor experiences that span before, during, and after events. Finally, drawing on literature on the experience economy, scholars have explained that intangible cultural heritage festivals can integrate entertainment, education, aesthetics, and escapism, thereby evoking emotional resonance and subjective well-being among tourists. For example, well-planned workshops, interactive rituals, role-playing, or themed evening events.

The second path in Figure 1 starts from the perspective of place attachment and place branding, passes through spatialization (S) and branding and diffusion (B), and finally reaches the place image and economic impact. Research on intangible cultural heritage and authenticity shows that people’s attachment to a place is built through tangible contact with a specific heritage environment, and efforts to promote intangible cultural heritage for tourism often involve reconfiguring streets, squares and historic districts into “festival spaces” [12,16]. Based on this insight, this study captures how ICH festivals are incorporated into specific spatial arrangements, such as parade routes, waterfront stages, newly decorated streetscapes, and landmark nodes, through which participants repeatedly experience the festivals and emotionally “anchor” them to the city. Furthermore, the literature on place branding points out that place branding is not simply a slogan, but rather stems from the interaction between spatial experiences and the narratives surrounding those experiences [12]. Kavaratzis and Kalandides [16] point out that place branding is generated through “the interactive formation of place branding,” in which the physical environment, daily practices, and stakeholder communication collectively construct the psychological image of the place.

Recent studies on heritage-led urban development emphasize that festivals and intangible cultural heritage practices are no longer just “events” but tools of urban and regional policies, which inevitably reshape local power relations and the distribution of interests [13]. Studies on the gentrification and tourism of heritage neighborhoods have shown that whether festivals are a “threat” or an “opportunity” for local communities depends on the decision-making process, the authority of the participants, and the way conflicts are mediated [13]. At the same time, research on technology-enabled festival branding emphasizes that innovative forms, such as interactive installations, digital extensions and hybrid online and offline experiences, require coordination among public institutions, private operators and local residents, rather than being designed unilaterally by organizers [28]. These insights form the basis of the two modules in our framework: experientialization (X) and co-creation governance (G). Both X and G ultimately point to Place image & economic impact, because immersive festival experiences can directly enhance the attractiveness and distinctiveness of the destination, while robust co-creation governance determines whether such experiential gains translate into legitimate, widely accepted forms of local revitalisation and shared economic benefits. Conceptually, this pathway assumes that the influence of Experientialization (X) on place image and local economic outcomes is partly mediated by Co-creation governance (G). In other words, without inclusive and responsive governance, experimental festival experiences may remain temporary spectacles or even intensify social tensions; with effective co-creation governance, they are more likely to consolidate positive place images and support sustainable “place-making”.

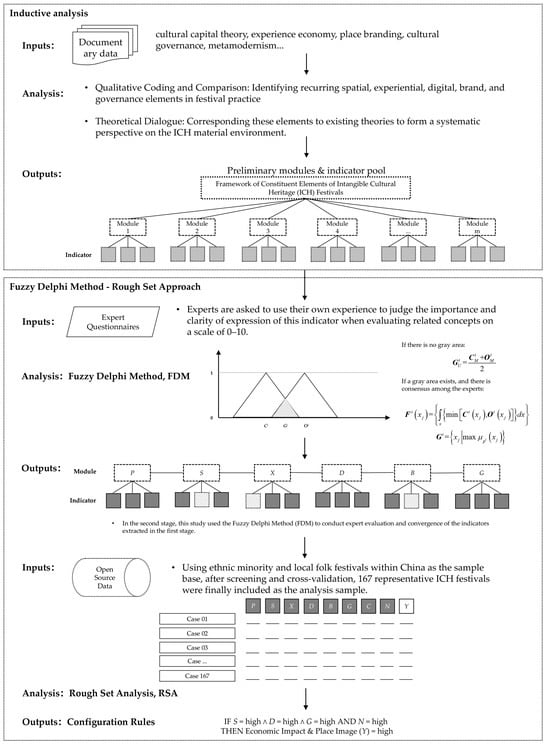

To achieve the aims and sub-objectives of this study, we develop a research design grounded in multi-case, multi-source configurational analysis. Focusing on representative Chinese folk festivals, we combine the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM) with Rough Set Analysis (RSA) to examine how materialisation practice modules of ICH festivals, moderated by classicity and novelty, shape place image and economic outcomes. First, drawing on prior literature and cultural capital theory, we inductively identify the key materialisation modules through which ICH festivals are translated from intangible cultural resources into urban assets that can be consumed, disseminated and governed. Next, informed by event portfolio theory [4], we specify the operational forms of each module by defining a set of core indicators under each. On this basis, we design an FDM questionnaire and convene a panel of experts to assess the importance of the materialisation modules and indicators derived from the theoretical groundwork. In parallel, we consider how local ICH festivals can maintain cultural authenticity amidst different dimensions of material concretisation (the authenticity-commodification debate). Complementing this, and following a scenographic perspective, we ask how non-material cultural elements are “staged” and transformed into consumable scenes. Accordingly, we treat economic benefit and place image as decision attributes, and introduce classicity (C) and novelty (N) as condition attributes that moderate the marginal effects of the other materialisation modules. In sum, the overall research design and the data collection/analysis workflow are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research design and data analysis process.

3.2. Summarizing and Constructing Modules and Properties

To ensure that the indicator construction in this study is theoretically grounded and practically representative, we first conduct a qualitative inductive analysis. Through a systematic review of academic literature, policy documents and case texts, we distil the latent factors by which ICH festivals influence place image and local economies, forming the initial indicator pool for the subsequent Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM). At this stage, the primary sources comprise studies published over the past decade in SSCI/SCI journals on ICH tourism, cultural festivals, city branding and the cultural economy. We also include heritage-protection and festival-promotion plans issued by China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism and by local governments. To ensure completeness, we incorporate qualitative materials drawn from open information platforms, including programme briefs for local traditional festivals, promotional press releases and media reports. In analysing these materials, we proceed as follows. First, we compile and organise multi-source texts to build an analytical corpus. Second, we mark descriptive segments related to how festivals affect place image and economic outcomes (initial coding). Third, we aggregate similar segments into higher-order categories and progressively merge them (category integration). Fourth, we raise the level of abstraction to derive two thematic groups—“materialisation practice modules” and “cultural attributes” (thematization). Finally, we map the resulting categories onto a three-layer theoretical structure to complete the theory alignment, thereby ensuring that the indicators are both empirically grounded and consistent with the overarching theoretical framework.

3.3. Expert Screening and Weighting Using the Fuzzy Delphi Method

To ensure that the research indicators reflect expert consensus and minimise subjective bias, this study employs the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM) to screen and converge the preliminary indicator pool. Combining the strengths of the traditional Delphi technique and fuzzy set theory, FDM converts expert judgements into fuzzy numbers and applies a “grey-zone” overlap test to assess the degree of consensus, thereby deriving the final set of usable condition attributes. The basic idea is to transform experts’ importance judgements for each indicator into a “most conservative cognition value” and a “most optimistic cognition value”, and then construct a pair of triangular fuzzy numbers. By comparing the overlap of the two triangular fuzzy numbers and the size of the grey zone, we determine whether expert opinions have converged and obtain a “consensus value” for each indicator. First, invited experts provide, for each indicator, both a most conservative cognition value and a most optimistic cognition value. Secondly, we compile all expert responses and remove extreme values that fall outside the mean ± two standard deviations. Thirdly, based on the cleaned data, we construct for each evaluation indicator two triangular fuzzy numbers—one for conservative cognition and one for optimistic cognition—each expressed as (minimum, geometric mean, maximum) (see Appendix A for detailed steps).

3.4. Configurational Analysis and Rule Extraction Using Rough Set Analysis

Rough set theory proposed by Pawlak is a data analysis method that deals with uncertainty and fuzziness in knowledge. It is particularly suitable for conditional rule extraction scenarios with “multiple cases—multiple attributes—multiple results” [29]. Compared to traditional regression or structural equation modeling, RST does not require additional statistical assignment assumptions. Instead, it directly uses the data itself to extract decision rules in the form of If…Then… from the relationship between conditional attributes and decision attributes. Therefore, this study uses RSA to analyze whether different module configurations cross specific threshold conditions under the adjustment of classicism and novelty, thereby leading to different ICH festival value transformation results. Before performing rough set analysis, we first standardized and appropriately discretized the continuous variables such as visitor numbers, consumption expenditure, UGC quantity, and resident participation rate, and constructed a decision table to form an information system that can be used for rule induction. Based on this, following the approach of existing research, the dependence of each condition attribute on the decision attribute is calculated. The higher the dependence, the stronger the explanatory power of the condition for decision classification. Next, by deleting redundant attributes and retaining the core attributes that have the greatest impact on decision classification, the rule extraction process is made relatively concise and representative in terms of dimensions. Finally, by combining conditional attributes as antecedents and decision attributes as consequents, a set of IF–THEN decision rules is derived, and the support and accuracy of each rule are calculated as preliminary indicators of its reliability. In this way, we can compare whether different combinations of conditions lead to the same result, revealing the multiple pathways and combinational causality of ICH festival value transformation.

Considering the unavoidable uncertainties in rule extraction with finite samples, this study added two simple robustness and uncertainty checks in addition to the standard RSA procedure. First, we use bootstrap resampling, which involves repeatedly drawing samples and re-reducing and generalizing the rules to observe the range of variation in overall classification quality, support for key rules, and accuracy. This provides range estimates for relevant indicators, rather than just reporting a single estimate. Second, we conduct simplified in-sample/out-of-sample validation: the case data is randomly divided into training and test sets, rules are established on the training set, and out-of-sample classification performance is calculated on the test set to evaluate the robustness of the rules on unseen data and reduce the risk of overfitting. At the epistemological level, we adopt a zetetic approach: the rules generated by rough sets are viewed as a set of “abductive best-explanations” and workable decision-making criteria under the current data and model settings, rather than as the discovery of indisputable causal laws. Through the aforementioned uncertainty management, this study attempts to provide a reasonable assessment of the credibility of the rules by classifying them, and to use these rules in a manner close to the “as-if pragmatism” emphasized by metamodernism, that is, to regard them as working hypotheses and practical tools for ICH governance and festival mix planning, while retaining the openness to further revise and update them for new data and new situations.

3.5. Case Selection, Indicator Measurement and Data Compilation

Building on six materialisation modules—productisation, spatialisation, experientialisation, digitisation, branding and diffusion, and co-creation governance—and two cultural moderating dimensions—classicity and novelty—this study establishes a multi-source, multi-level data registry to ensure that indicators are both operational and empirically robust. Objective statistics are taken from government and industry open sources, including annual reports of local culture and tourism departments, festival implementation plans, official statistical bulletins and e–commerce sales data (for example Taobao and JD.com), supplemented by Baidu Heat Map, Baidu Index and Google Trends; these inform measures such as cultural-creative product sales, festival site area, night-tour footfall and retail growth in adjacent business districts. Social and new-media data are drawn from Weibo, Douyin, Kuaishou, Xiaohongshu and Bilibili, covering user-generated content, interaction metrics and online viewership, to register indicators such as live-stream view counts, volumes of derivative content, social-media topic exposure and youth participation rates, thereby capturing the dynamism of the digitisation and novelty modules. Survey questionnaires and expert assessments complement cultural attributes that are difficult to quantify directly: visitor surveys record immersive performance, educational and aesthetic experience and the use experience of interactive installations on seven-point Likert scales, while expert ratings qualitatively quantify ritual integrity, level of innovativeness and bearer lineage to ensure theoretical and practical comparability. Finally, categorical and binary variables reflect recognition and institutional conditions, for example inscription on the UNESCO ICH lists (1 or 0) and official recognition level (national 3, provincial 2, municipal or county 1), facilitating the construction of decision tables for subsequent QCA and RSA analyses; together these sources form a multidimensional database spanning objective statistics, social-media dynamics, survey and expert judgements and institutional recognition, ensuring completeness, representativeness and alignment with the theoretical framework.

Furthermore, based on Storm’s anchoring perspective, we explicitly encoded the anchoring mechanism primarily reflected in each metric and module. For each metric in Table 1, we assigned one or more of three anchoring types: Dynamic Nominalism (DN), Imitation (M), and Ergonomics (E). In our coding, productization (P) is primarily anchored through DN and M (formal branding and licensing labels combined with the imitation of successful IP patterns). Spatialization (S) and co-creative governance (G) are primarily anchored by E and DN because they rely on persistent infrastructure and formal templates. Experiential (X) and digital (D) combine E and M, relying on technological devices and the replication or hybridization of existing immersive and streaming modes. Branding and communication (B) is mainly reflected in DN and M, which involves stabilizing labels and narratives while spreading through imitative communication methods. Therefore, the classicism indices (C1–C3) are primarily anchored to DN (and also include some E), while the novelty indices (N1–N3) mainly reflect M and E. Clarifying these anchors indicates that C/N is a type of social stability rather than an intrinsic nature, and improves the causal interpretability and cross-contextual generalization of our rule set.

Table 1.

Data types and sources of collection.

As shown in Table 1, this study ultimately established a multi-source, multi–level data registry encompassing official reports, e–commerce and travel-platform data, social-media big data, and survey and expert evaluations. In practice, we invited 15 experts (including ICH scholars, local culture-and-tourism officials, festival planners, and nationally or provincially recognised bearers) to participate in the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM), assessing and converging 42 initial indicators under the eight modules. To ensure the completeness of objective data, for 167 local ICH festival events used as cases we additionally collected approximately 12,496 records of cultural–creative product sales via web crawlers and APIs from the Taobao and JD ICH sections, and about 12,855 items of UGC and interaction data from platforms such as Douyin and Xiaohongshu to capture indicators related to digitisation and novelty. After de-duplication and keyword screening, these social-media data were consolidated into 5578 high-quality samples. For cultural attributes that are difficult to quantify objectively, such as ritual integrity and aesthetic experience, we designed on-site and online questionnaires and obtained 6032 valid responses measured on seven-point Likert scales. Experts, through three rounds of rating, provided qualitative quantifications for indicators such as bearer lineage and innovation level, which were ultimately normalised to 0–1. Drawing on these multiple sources, the study ensured the operability of the eight condition attributes and assembled a sufficiently rich and diverse evidence base for constructing the subsequent RSA decision tables.

Following the construction of the indicator system and data collection, we applied Rough Set Analysis (RSA) to the 167 ICH festival cases to conduct a configurational examination of how different materialisation practice modules, moderated by classicity (C) and novelty (N), jointly lead to high economic impact and enhanced place image. The RSA procedure was as follows. First, we built a decision table. Using 167 festival events as the study universe, we defined the eight modules (P, S, X, D, B, G, C, N) as the set of condition attributes (A), each discretised—per the processing above—into high/low or high/medium/low categories; ‘high economic impact’ and ‘enhanced place image’ formed the set of decision attributes (Y). The decision attributes were derived from indicators including tourism revenue, visitor growth rate, media coverage intensity, and revisit or word-of-mouth intention.

Secondly, we compute the classification quality to assess the explanatory power of the condition attributes for the decision attributes. Its formulation (Equation (1)) is the ratio of the number of objects in the positive region of the decision attribute to the total number of samples.

Thirdly, we identify core attributes via attribute reduction. Concretely, we iteratively test whether removing a given attribute decreases the classification quality; if its removal reduces quality, that attribute is deemed core. Core attributes are those conditions with the most critical explanatory power for the decision. Finally, based on the reduced subset of attributes obtained from the core set, we apply decision rule induction to generate causal rules mapping condition-attribute configurations to decision attributes. For example, a typical rule might read: ‘IF productisation (P) is high AND co–creation governance (G) is high, AND under a context of high novelty (N), THEN economic impact is high.’ These rules are expressed in IF–THEN form and are accompanied by support and confidence measures to indicate their statistical robustness and scope of applicability. Through this procedure, the study reveals multiple equifinal pathways, demonstrating the diverse routes to success for ICH festivals.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Screening Key Indicators Describing the ICH Materialisation Modules

Building on the eight condition attributes and twenty-three specific quantitative indicators set out in Table 1, we employed a multi-round Fuzzy Delphi survey to validate and converge the framework. Fifteen experts (basic characteristics shown in Table 2) evaluated the eight attributes and their twenty-three subordinate indicators. Respondents were drawn from multiple provinces and regions in North China, East China, Southwest and Northwest China. Approximately one-third had long-term work experience in ethnic minority-concentrated areas or in national-/provincial-level ICH clusters, covering a diverse range of sectors including universities and research institutes, public-sector culture and tourism authorities, festival planning and operations units, as well as local business organisations. Overall years of professional experience ranged from 5 to 13 years, with a median of about 8 years, ensuring that the experts possessed both theoretical perspectives and substantial practical experience. In the three rounds of the FDM survey, the effective response rates were as follows: in the first round, 15 questionnaires were distributed and 13 were returned (an effective response rate of approximately 86%); in the second round, the same 13 experts who had completed the first round were invited again, and all 13 responses were retained (about 93%); the third round focused on re-evaluating a small number of indicators that had not yet converged, and finally 13 complete questionnaires were collected. Overall, expert participation and response rates remained high across all three rounds, reducing the risk that panel attrition would bias the convergence results.

Table 2.

Profile of participating experts.

Each expert provided, for every indicator, a “most conservative”, “most probable” and “most optimistic” value; convergence was then tested using triangular fuzzy number transformation and a grey-zone overlap check. The results show that twenty indicators met the convergence criterion and were retained; three indicators—UGC derivative resources (D3), interactive installations (X1) and cross-border media coverage (B2)—failed to converge due to substantial divergence among experts, suggesting that their importance varies across cases and remains contested.

This study followed a principle of stepwise convergence. In the first round, seven of the twenty-four initial indicators exhibited marked divergence in expert judgements: the grey zone exceeded the gap between the conservative and optimistic geometric means, indicating a lack of consensus on their importance. For these non-convergent indicators, a second-round questionnaire was administered, accompanied by summary statistics from round one so that experts could re-evaluate with awareness of the group’s overall responses. After the second-round assessment, consensus was achieved for most items, with only three indicators still showing substantial disagreement (see Table 3). These three were ultimately confirmed for removal in the third round. Regarding the specific criteria for determining gray areas, we follow the existing FDM literature and use the difference (Mi) between the geometric means of the two triangular fuzzy numbers and the gray area width (Zi) as convergence indicators, and use Mi − Zi ≥ 0 and the consensus indicator Gi ≥ 6 as the main thresholds for “reaching consensus”. As shown in Table 3, the Mi − Zi values of most indicators are greater than 0, and the Gi values are all higher than 6, indicating that experts have reached a sound consensus on the importance ranking. In contrast, the three deleted indicators were interactive devices (X1), UGC derivative resources (D3), and cross-border media reporting (B2). These indicators consistently showed low consensus in multiple rounds of expert questionnaires. Although experts had sufficient consensus on these three indicators, they all believed that their importance was insufficient. Therefore, we considered these three indicators as controversial indicators falling into the “grey zone” and removed them after the third round.

Table 3.

Fuzzy Delphi results.

During the three-round expert survey, we found that three indicators—interactive installations (X1), UGC derivative resources (D3) and cross-border coverage (B2)—failed to reach consensus and were ultimately excluded from the condition-attribute system. From the standpoint of expert heterogeneity, all three involve highly dynamic and context-dependent elements. In our view, the experiential effect of interactive installations is contingent on specific design technologies, site conditions and audience profiles; the influence of UGC derivatives is strongly shaped by platform rules, algorithms and community cultures; and the value of cross-border coverage depends on the intrinsic newsworthiness of an event and the agendas of international media. These contingencies vary markedly across festival cases, making it difficult for experts to agree on their universal importance. To examine whether deleting these three metrics would have a conclusive impact on subsequent rough set analysis, we conducted a simple sensitivity test: after incorporating X1, D3, and B2 into the conditional attributes and re-performing reduction and rule induction, the overall classification quality only changed slightly from 0.898 to about 0.89. The core attribute combination remained stable on the S–D–G ternary structure, showing that whether or not they were deleted would not change the main decision rules and theoretical conclusions.

4.2. Discretisation and Categorical Analysis of ICH Case Data

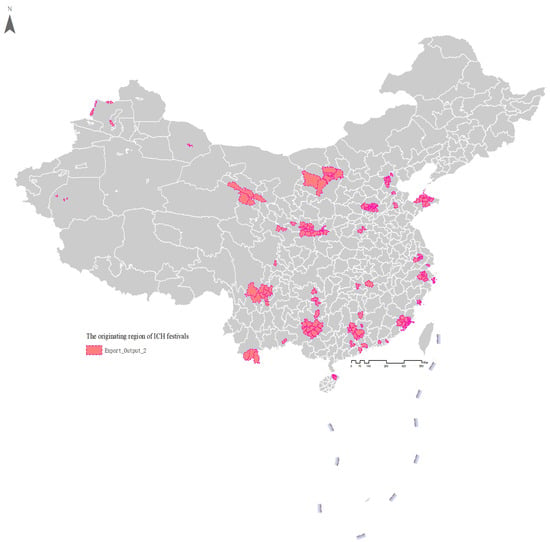

Following convergence of the indicator system, we proceeded to discretise and classify the dataset covering 167 local minority-festival cases. These ICH festival events originate from the urban areas shown in Figure 2 and are distributed across multiple provinces and regions of China, encompassing the southwest, northwest, south and north. The sample is concentrated in minority-inhabited areas and ICH-rich regions—for example Zhuang, Miao, Yi and Dong festivals in Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi and Sichuan, and Mongolian and Hui festivals in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Ningxia. At the same time, selected Han Chinese traditional festivals from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the south-eastern coastal belt are included, yielding a multi-level, multi-ethnic and multi-geographical case set.

This study first compiled 238 ICH festivals related to ethnic minorities from the national intangible cultural heritage list published by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the festival catalogs of provincial culture and tourism departments, and publicly available data from local governments, as the initial parent group. Based on this, we adopted the following inclusion criteria: (1) It has been held for at least three consecutive sessions during the observation period of this study; (2) It is directly associated with a formally recognized national or provincial ICH project; (3) It has basic and comparable data in three sources: economic indicators, media data and tourist surveys (as shown in Figure 3). At the same time, cases that are large-scale events held only once, ceremonies that are mainly aimed at closed religious communities and lack publicly available information, and cases with an excessively high proportion of missing key indicators are excluded. In addition, due to the severe impact of COVID-19 on tourist traffic and consumption patterns, this study mainly selected 2016–2019 and 2022–2025 as observation periods, and used the comprehensive data of the most recent one or two events as representative values for each festival. Of the 167 festivals ultimately included, approximately 23.9% are located in southwestern provinces with large minority populations (Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, Sichuan, etc.), 13.2% are located in northwestern and northern ethnic minority areas (Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Ningxia, etc.), and the remainder are distributed in Han Chinese areas along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the southeastern coast. Divided by city level, provincial capitals and sub-provincial cities account for 3.6%, prefecture-level cities account for 10.8%, and county-level cities and townships account for 86.6%, forming a multi-level sample structure from metropolitan areas to small and medium-sized cities and counties.

Figure 3.

Regions of ICH festival activities.

Because the specific indicators under each module—for example sales revenue, visitor numbers, UGC counts and media mentions—are continuous or count data, feeding them directly into a rough set system would produce overly dispersed distributions that hinder rule induction. We therefore apply fuzzy-number mapping combined with quantile cut-offs to transform raw values into two- or three-level categories, namely low (1) and high (2), or low (1), medium (0) and high (2), thereby building a strongly comparable categorical database. Having established the sampling frame and discretisation standards, we then created, for each of the 167 cases, a “condition–decision” record to form a complete decision-table structure. This procedure relies on multi-source data collection and cross-platform auditing to ensure that every case carries comparable, well-sourced indicator values.

For the condition attributes, the six materialisation practice modules (P, S, X, D, B, G) and the two cultural moderators (C/N) were coded from multiple sources. For the productisation module, cultural-creative product development (P1) was traced via sales data from the Taobao and JD ICH sections, while brand licensing (P2) and IP transformation (P3) were drawn from official event reports and licensing cases. Within spatialisation, night-time lighting (S2) and coupling with commercial districts (S3) were captured from municipal tourism bulletins and Baidu Index behavioural data. For experientialisation, immersive performances (X2) and educational/aesthetic experience (X3) were derived from Xiaohongshu and other visitor reviews together with on-site survey responses. The digitisation module comprised AR/VR tours (D1) and live streaming (D2), with viewing and interaction metrics obtained from Douyin. For branding and diffusion, traditional and social-media dissemination (B1) was measured through news databases and Baidu News heat indices. Co-creation governance (G1–G3) drew on official local registers, counts of resident participation and records of merchant collaboration. Classicity (C1–C3) and novelty (N1–N3) were converted respectively from expert assessments and questionnaires completed by visitor representatives.

For the decision attributes, both economic impact and place-image enhancement were likewise assembled from multiple sources. Economic impact was primarily gauged by growth in tourism revenue, local statistical bulletins and consumption in adjacent business districts, supplemented by e-commerce sales indicators. Place-image enhancement was assessed through news and social-media heat (number of articles, search volume, Weibo/Douyin interactions) and by survey measures of revisit intention and word of mouth. To mitigate bias, the research team cross-checked and weighted subjective survey data (6032 valid responses) against objective big data (5578 screened social-media samples), producing more reliable indicator entries. Ultimately, we compiled a complete 167 × (eight condition attributes + two decision attributes) data matrix (a subset is shown in Table 4). Each case is assigned a set of standardised, discretised attribute values, providing a solid basis for subsequent rough set dependency analysis, attribute reduction and rule extraction.

Table 4.

Data registry of condition and decision attributes for selected ICH festival cases.

It should be noted that while using quantile mapping to discretize continuous variables facilitates subsequent rough set modeling, it may also “compress” or “cut off” relationships that originally existed on a continuous scale in some cases. To examine whether the results of this study depend on a specific discretization setting, we conducted two additional robustness checks. First, regarding granularity sensitivity, we discretized the condition and decision attributes into two levels (binary high/low), three levels (low/medium/high used in the main model of this study), and four levels (divided by quartiles), respectively. Under each binning strategy, we re-executed rough set reduction and rule extraction to compare the changes in core attribute combinations and overall classification quality. Secondly, regarding supervised discretization, we use the minimum description length criterion based on information entropy to automatically segment each continuous index, so that the cut-off point is no longer determined solely by quantiles, but is optimized based on the ability to distinguish decision attributes (high/low economic impact and local image). On this basis, we perform rough set analysis again to examine whether the core conditions and main rules are consistent with the master model under entropy-based discretization.

4.3. Configurational Analysis of ICH Festival Attributes Based on RSA

Using rough set analysis on 167 minority ICH festival cases, we built a configurational model linking condition attributes to decision attributes. The results indicate that, among the eight module attributes, four entered the core set at the initial stage—spatialisation (S), digitisation (D), branding and diffusion (B), and co-creation governance (G)—with an overall classification quality of 0.898, suggesting the model explains close to 90% of decision outcomes (see Table 5). Based on this, we further used bootstrap resampling to conduct a robustness check. The results showed that the overall classification quality distribution was relatively concentrated in multiple resamplings, with the 95% interval roughly falling between 0.84 and 0.93, indicating that the rule set still has stable explanatory power under sample fluctuations. Meanwhile, the in-sample/out-of-sample validation results based on a random 8:2 split show that the classification quality of the training set is about 0.91, and the out-of-sample classification accuracy of the test set is about 0.85–0.87. The difference between the two is limited, indicating that the model’s performance on unseen data is still reasonable, and there is no obvious overfitting problem. Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis results of the discretization strategy show that the main configuration conclusions of this study are quite robust under different settings. When the conditions and decision attributes are classified using binary (high/low), triadic (low/medium/high), and quartile classification respectively, the overall classification quality remains roughly between 0.81 and 0.94, with limited difference from the baseline model of 0.898. In all settings, spatialization (S), digitization (D), and co-creation governance (G) are consistently identified as core attributes, while productization (P) and brand diffusion (B) appear briefly as secondary conditions in some settings. By further adopting entropy-based supervised decentralization, the core conditions and dominant combinations of the resulting rule set are highly consistent with the main model, with only minor changes in the support and accuracy of some rules. The results above show that the S–D–G key group configuration presented in this paper is not the product of a single quantile binning, but a robust pattern that can be repeatedly observed under various discretization strategies.

Table 5.

RSA statistical results.

This aligns with recent heritage research underscoring multi-factor interweaving, namely that ICH value transformation is not driven by a single lever but by the compounded effects of interacting modules [41]. After attribute reduction, the analysis further corroborates the core status of digitisation (D), co-creation governance (G) and spatialisation (S). The remaining attributes, while theoretically complementary, did not exhibit significant explanatory power for classification in the empirical data. In other words, the value transformation of ICH festivals can be effectively captured by an S–D–G triangular structure, with branding and diffusion (B) acting as a supportive, context-dependent condition rather than a universal core.

From a hylosemiotics perspective, the results of this study also provide a more detailed interpretation of the roles of spatialization (S) and brand/diffusion (B). The spatialization module encompasses the layout of festival venues, lighting design, procession performances, and coupling with commercial districts, forming the material scene foundation upon which the audience can move, linger, and perceive, while also embedding ritual rhythms and spatial language familiar to the local community. In contrast, the media reports, slogans, social media topics, and city brand narratives involved in the brand and diffusion modules translate these specific scenarios and ritual practices into symbols and stories that can circulate in different communication channels. Hylosemiotics emphasizes that the festival experience does not come from two separate technical paths of “material setting” and “symbolic promotion,” but rather from a continuous material–symbolic co-construction process between “scene and symbol”: S provides the material carrier that carries meaning, while B organizes and amplifies the cultural narrative that can be read and shared on it.

Under this understanding, the rough set rule’s statement that “S stability is the core condition and B is a situational auxiliary condition” becomes more clearly explanatory: only when the scene shaped by S resonates sufficiently with local rituals and historical memories through material–symbolic resonance will the investment in branding and diffusion bring significant marginal benefits—media and platforms can then rely on scenes with deep symbolic density to re-narrate and reproduce. Conversely, if the scene design has a weak connection with the local cultural vocabulary and only remains a superficial visual spectacle, even with large-scale investment in publicity and traffic generation, it will be difficult for B to leverage lasting local identity and word-of-mouth accumulation. Its position in the configuration rules will naturally tend to be “supporting” rather than “universally core”. In other words, the results of this study show that the effectiveness of brand and diffusion modules depends not only on the scale of communication investment, but also on whether they are successfully anchored in material contexts with deep local symbolism.

Among the three core attributes, digitisation (D, 0.593) exerts the strongest influence, indicating that its absence would markedly reduce classification quality; spatialisation (S, 0.563) ranks second, underscoring that scene-making remains the physical foundation of festival impact; and co-creation governance (G, 0.485) follows, highlighting the importance of resident and bearer participation for cultural legitimacy and sustainability. These findings resonate with Getz and Page [4] scene–experience–community participation framing, yet our results go further in showing that, in the digital era, digitisation is not an ancillary module but the primary driver of festival influence. At the same time, the results support Richards [42] discussion of the innovation–tradition tension: S and G safeguard authenticity and embeddedness, while D provides the medium and platform for ongoing innovation.

Through rule induction under Rough Set Analysis (RSA), we constructed a decision table for 167 minority ICH festival cases and obtained six principal rules (see Table 6). These rules show how different module configurations, moderated by classicity (C) and novelty (N), lead to high or low outcomes on “economic impact and place-image enhancement” (Y = 1 or 2). First, spatialisation (S) and digitisation (D) appear with high frequency across most rules, indicating that scene-making and digital diffusion have become core drivers of value transformation. As Rules 1 and 4 demonstrate, when S and D are both high, the Y outcome rises significantly even when other module conditions vary, evidencing the robust effect of the immersive scene & digital diffusion combination. This aligns with recent cultural-tourism research emphasising a dual-drive model that couples immersive experience with digital enablement.

Table 6.

Decision rules linking ICH festival condition attributes to local economic impact and place image (coverage > 10%).

Secondly, co-creation governance (G) is accentuated in Rules 2, 3 and 6, indicating that resident participation and community co-management further amplify the effects of S and D. When G is high, the outcome Y tends towards 2 even when C or N varies, implying that festivals cannot succeed through digitisation and spatial design alone; sustainable value transformation requires coupling these levers with locally grounded governance arrangements.

Notably, although C and N do not appear as core conditions in the rules, they act as moderating factors in most cases. For example, when C is high it lends cultural legitimacy to the S & G bundle, enabling festivals to preserve ritual gravitas while enhancing visitors’ perceptions of authenticity and dampening concerns about over-commercialisation. Conversely, when N is high it amplifies the marginal effects of D (and, to a degree, S), particularly in digital dissemination and cross-media diffusion, where novel elements markedly increase social-media engagement and youth participation. Accordingly, we argue that while C and N are not decisive conditions, they operate through a moderating pathway that strengthens or weakens the effects of S, D, and G, forming a complementary nexus of traditional legitimacy—digital innovation—community participation.

4.4. Synthesis of Results and Theoretical Implications

Bringing together the FDM screening, RSA-based attribute reduction, and rule induction, three main empirical insights emerge. First, the value transformation of ICH festivals is not driven by any single materialisation module but by a small set of recurrent configurations. Across all discretisation schemes, spatialisation (S), digitisation (D) and co-creation governance (G) consistently enter the core set and jointly sustain a high classification quality, while productisation (P), experientialisation (X) and branding diffusion (B) play more peripheral or context-contingent roles. This confirms that festival success depends on how scenes, digital infrastructures and governance arrangements are combined, rather than on isolated “best practices” in one domain.

Second, the configurational rules clarify how classicity (C) and novelty (N) reshape the marginal effects of these modules. In high-classicity contexts, rules with strong explanatory power typically feature S and G as necessary or quasi-necessary conditions, with D playing a supportive amplifying role. This pattern indicates that when ritual integrity, recognition status and bearer lineage are strongly anchored, well-designed scenes and participatory governance become the main channels through which cultural legitimacy is converted into economic impact and enhanced place image. By contrast, in high-novelty contexts the rules shift towards D-centred combinations: strong digitisation, together with at least moderate S or B, is sufficient to generate high outcomes even when classicity is weaker. In other words, novelty amplifies the returns to digital mediation and immersive experiences, while classicity stabilises the legitimacy and community embeddedness of scene- and governance-based pathways.

Third, several rules illustrate a metamodern oscillation between classicity and novelty rather than a simple trade-off. Configurations with the highest support and accuracy typically do not maximise C or N alone, but alternate between them in a “both/and” fashion—for example, festivals that retain a gravitas-laden daytime ritual procession (high C, strong S and G) while introducing evening light shows, live streaming and interactive installations (high N, strong D and X). Such patterns resonate with the metamodern view of oscillation and sublation: classicity and novelty are not mutually exclusive poles but dynamically combined to generate higher-order place-brand and economic value. This also reflects a hylosemiotic logic in which material scenes (lighting, layout, processions) provide the substrate on which digital signs and media narratives travel, explaining why the absence of S markedly degrades classification quality even when D is strong.

From a practical standpoint, the induced If…Then… rules offer interpretable decision support for urban event planning and ICH governance. Municipal planners and festival organisers can use the S–D–G-centred configurations as screening templates when designing or revising event portfolios—for example, prioritising investments in scene quality and participatory governance for high-classicity flagship events, while allocating more resources to digital platforms and cross-media storytelling for innovation-oriented or youth-targeted festivals. Because the rules have been tested for uncertainty (bootstrap intervals and granularity sensitivity) and remain stable across alternative discretisation schemes, they can be used as “as-if” decision heuristics: not as deterministic laws, but as transparent, data-driven guidelines to balance protection and use, and to allocate limited resources across competing festival projects.

The results of this study both confirm and expand upon the existing event tourism framework, particularly the scenario-experience-community engagement model for planned events proposed by Getz and Page [4]. In the framework constructed in this study, spatialization (S) mainly corresponds to “scenario”, experientialization (X) corresponds to “experience”, and collaborative creation governance (G) corresponds to “community participation”. However, rough set methods show that holiday outcomes do not depend on the linear predictions of these dimensions individually, but rather on a specific combination of S–D–G, where productization (P), experientialization (X), and brand promotion/communication (B) act as context-enhancing factors. Furthermore, by introducing classicism and novelty as postmodern moderating variables, we found that the scenario- and governance-centered approach is particularly effective in highly classic contexts, while the digitization-centered approach dominates in highly novel contexts. In this sense, this study transforms previous event tourism models into an interpretable form of decision analysis, expressed with clear “if…then…” rules, and places them within a broader context of classicism-novelty dynamics and a semiotic understanding of how material scenes and symbolic narratives jointly create the value of intangible cultural heritage. This helps intangible cultural heritage research move beyond debates about single variables of authenticity versus innovation, and instead focus on configurative explanations of how different material modules and cultural attributes collectively shape local image and economic impact.

5. Conclusions

Drawing on 167 cases of minority ICH festivals in China and combining the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM) with Rough Set Analysis (RSA), this study examines how different materialisation practice modules and cultural attributes jointly shape the dual transformation of local economies and place image. The results show that spatialisation, digitisation and co-creation governance co-occur at high frequency across the decision rules and constitute the core driving bundle of ICH value transformation. Spatialisation (S) secures the scenographic experience and local recognisability of festivals; digitisation (D) amplifies the external reach of cultural content and extends the radius of dissemination; and co-creation governance (G) sustains the participation and legitimacy of cultural bearers, enabling a workable balance between commercialisation and authenticity. Further rule analysis reveals a clear moderating role for classicity (C) and novelty (N) in value generation. When C is high, ritual integrity and lineage-based legitimacy stabilise S and G and safeguard cultural depth; when N is high, innovative formats and digital immersion increase the marginal returns to D and strengthen market appeal. Taken together, the two dimensions produce a “cultural depth with innovative vitality” pattern and suggest that ICH festivals are not static cultural symbols, but continuously reproduced value systems.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings contribute to research on ICH tourism and the cultural economy in several ways. First, the empirical evidence on the S–D–G core bundle illustrates how festivals act as dynamic mechanisms of cultural–capital conversion. Rather than viewing ICH as a static resource that simply requires protection, the study shows how spatial scenes, digital infrastructures and co-creation governance interact to transform cultural meaning into economic and branding assets without necessarily diluting authenticity. This supports, but also refines, existing debates on the relationship between commodification and cultural value.

Second, the complementarity between spatialisation and digitisation, anchored by co-creation governance, supports a configurational understanding of festival success. The rough-set rules demonstrate that high economic impact and enhanced place image are achieved through a small set of recurrent configurations, rather than through single “best-practice” levers. This confirms and extends the scene–experience–community participation framing in the event-tourism literature by showing that scenes, technologies and governance arrangements form a triangular structure with equifinal pathways.

Third, the study offers a structured way to bring classicity and novelty into ICH analysis as measurable moderating dimensions. By quantifying C and N and examining how they alter the marginal effects of S, D and G, the study moves beyond binary debates of authenticity versus innovation. Classicity enhances cultural legitimacy and embeddedness, while novelty increases market competitiveness and communicability; the two logics operate not as simple opposites but in a symbiotic, oscillatory relationship consistent with a metamodern lens. In this sense, the configurational rules provide an integrated explanation of how different materialisation modules and cultural attributes jointly shape place image and economic outcomes.

Methodologically, the cross-domain integration of FDM and RSA shows how indicator systems, expert weights and case-based rules can be linked in a single multi-attribute decision-making pipeline. The use of bootstrap, out-of-sample checks and granularity sensitivity analyses also illustrates how interpretable, rule-based analytics can incorporate uncertainty rather than claiming deterministic laws.

5.2. Practical Implications

The induced If…Then… rules provide interpretable and operational decision support for urban festival planning and ICH governance. For high-classicity flagship festivals, the results suggest prioritising investments in scene quality and co-creation governance, such as spatial layouts that respect ritual grammars, careful integration of commercial areas, and mechanisms that give residents and heritage bearers a substantive role in planning and operation. Digitisation can then be used primarily as an amplifier, for documentation, selective online diffusion and the extension of influence without undermining ritual gravitas.

For innovation-oriented or youth-targeted events, the rules point towards more digitisation-centred configurations. Strong digital infrastructures, immersive and interactive technologies, and cross-platform storytelling, combined with at least moderate spatial design and branding, are sufficient to generate reach and spending even when classicity is weaker. In such cases, novelty amplifies the returns to digital mediation and helps attract new audiences and external visitors.

At the portfolio level, municipal authorities and planners can treat the S–D–G-centred configurations as templates when composing an annual calendar of events. A mix of high-C, S/G-anchored festivals that stabilise place identity and high-N, D-centred festivals that drive experimentation and visibility can help balance protection and use. Because the rules have been tested for robustness and uncertainty, they can be used as pragmatic “as-if” heuristics for screening project proposals, prioritising resource allocation and conducting sensitivity analysis across competing ICH festival projects.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work