Abstract

Access to Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) is a critical component for social inclusion and population development. This study aimed to analyze ICT access in Argentine households, considering its distribution according to deprivation conditions and area of residence (urban–rural) at the regional level, and incorporating a spatial association perspective at the departmental level. The percentage of households with Internet access, computers (or tablets), and cell phones with connectivity was examined at the regional level, according to household deprivation type and area of residence. At the departmental level, the analysis was conducted through thematic maps and the estimation of spatial autocorrelation patterns (global and local Moran’s Index). Indicators were constructed using data from the 2022 Population, Household, and Housing Census. Results revealed significant disparities in ICT access, attributable to deprivation conditions and the geographic distribution of households. Spatial autocorrelation patterns with low ICT access were mainly identified in the Northwest (NOA) and Northeast (NEA) regions, while the highest coverage levels were concentrated in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (AMBA), the Pampeana, and Patagonia regions. The evidence highlights the need to design public policies aimed at reducing digital divides.

1. Introduction

Throughout the twenty-first century, Argentina has made significant progress in digital inclusion, positioning itself as one of the countries with the greatest access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Latin America and the Caribbean [1,2]. The expansion of coverage, particularly since the early 2010s [3], is closely related to the implementation of public policies focused on access, use, and appropriation of these technologies [4,5,6,7]. Nevertheless, the literature and statistics provided by international organizations suggest that substantial gaps persist, especially among lower-income strata and in rural areas [8,9]. This situation reflects the conditions of poverty and the lag in educational and occupational trajectories of the population [10].

Most studies aimed at analyzing these socioeconomic inequalities in the region, and particularly in Argentina, have relied on data from household surveys [11,12,13,14]. This approach limits the possibility of examining household access to ICT according to sociodemographic characteristics associated with stratification inequalities, while ensuring full population coverage (free from sampling errors) [15,16]. It also restricts the capacity to study ICT distribution in smaller populations using geographic information systems (GIS) [17,18,19,20].

Within this framework, the present study aims to analyze household access to ICT in Argentina, considering its distribution according to deprivation conditions and area of residence (urban–rural) at the regional scale, and incorporating a spatial association perspective at the departmental level. Specifically, using microdata from Argentina’s 2022 Population, Household, and Housing Census, this research seeks to answer the following questions: What differences in ICT coverage are observed among households across Argentina’s regions in 2022? What is the level of ICT access according to deprivation type and area of residence in households across the country’s regions in 2022? What is the degree of spatial clustering of households with ICT access across Argentina’s departments in 2022? And what patterns of spatial autocorrelation, associated with low and high levels of access, can be identified across the national territory in 2022?

To address these questions, the analysis first examines household coverage of computers (or tablets), cell phones with connectivity, and Internet access by deprivation category and area of residence (as a proxy for potential differences in access among social groups), considering their distribution according to the Household Material Deprivation Index (HMDI) and the territorial area (urban–rural) at the regional level. Second, access to the aforementioned ICTs is represented through thematic maps that illustrate the spatial distribution of these digital technologies across the country’s departments. Finally, also at the departmental level, the Moran’s Index—both global and local versions—is used to identify patterns of spatial autocorrelation in ICT access.

This approach makes it possible to visualize how inequality in digital coverage is spatially manifested as an expression of poverty, reinforced by the conditions of energy infrastructure [8]. The methodological path presented enables the identification of digital inequality patterns through an ecological approach that considers variables of ICT access, material deprivation (as a proxy for the social group to which the household population belongs), and geographic location, employing GIS-based analytical tools. This study aims to provide updated empirical evidence and contribute to the development of geospatial methodologies applied to the analysis of digital divides—an area of research that remains relatively unexplored in Latin America and the Caribbean [17,18,19,21,22].

In the hypothesis of this study, it is proposed that the lowest levels of coverage will be observed among households with greater deprivation, particularly those classified as convergent (as defined in the methodological section) and located in rural areas. In line with the estimates reported by previous studies [3,14,15], it is anticipated that spatial association patterns (at the departmental level) linked to low access to ICT will be concentrated in the Northwest (NOA) and Northeast (NEA) regions of Argentina, while clusters of high coverage will be found in the populations of the Pampeana region and, especially, in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (AMBA).

The results are expected to guide public interventions aimed at promoting digital inclusion and supporting community development in key areas closely linked to ICT access, such as energy, health, employment, education, and mobility [23].

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptualization of the Digital Divide Phenomenon in the World and in Latin America and the Caribbean

ICTs, understood as tools, resources, and programs that facilitate the processing, storage, and transmission of digital information, have become a fundamental component for promoting human development [10,24,25]. In the digital era, devices such as computers and mobile phones with connectivity, together with services such as the Internet, are key elements in building sustainable societies [26], both in terms of economic growth and progress in social equity and environmental promotion [27,28,29]. As noted by Lythreatis, Singh, and El-Kassar [30], the potential of ICT related to innovation, inclusion, and resource-use efficiency can have a significant impact on achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

From a resource management perspective, these technologies—by broadening access to information and interaction among groups—enhance understanding in decision-making related to consumption and production, which intrinsically contributes to economic growth, poverty reduction, and improved living conditions [15,31]. In contrast, from a more humanistic perspective [10], though not detached from the material conditions of people’s existence, their incorporation contributes to collective well-being and social inclusion, particularly in sectors such as education [1,11], health [32], employment [33], environmental sustainability [29], and financial inclusion [34], among others. In this sense, ICTs act as catalysts for more accessible and flexible educational processes (e.g., virtual classes), enable access to remote health services (such as telemedicine), and foster new forms of work and entrepreneurship (e.g., teleworking across various sectors), potentially reducing disparities and promoting the formation of more equitable communities [35].

Globally, there has been an increase in the proportion of people and households with Internet, computers, and/or mobile phones with connectivity; however, significant differences in the availability of these tools persist, especially in countries lagging behind in terms of sustainable development [36,37,38,39]. In the specific case of Latin America and the Caribbean, although ICT coverage has expanded, by the beginning of the third decade of the twenty-first century more than 40 million households still lacked connectivity, mainly affecting the lowest income quintiles and rural areas [12,13]. Specifically, while in urban areas the regional average of connected households reached 76.3% in 2023, in rural areas it was 40.4%, and among the lowest wealth quintiles, around 25.7% [40,41,42]. Likewise, estimates from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) [43] indicate that despite increases in the percentage of households with fixed and mobile broadband, subscription rates remain significantly lower than in European Union countries, with the widest gaps observed in fixed connections. The higher prevalence of mobile broadband over fixed broadband is largely associated with lower subscription costs [43].

These heterogeneities are known as digital divides, generally understood as inequalities between populations that have access to ICT and those that do not, or that have limited or outdated access [15,37]. The lack of adequate coverage of such resources constitutes a symptom of sociodemographic vulnerability, associated with populations experiencing high levels of deprivation of current and patrimonial household resources, low income and limited educational attainment among household heads [5,10,24,38], high rurality [16], as well as restricted access to basic services (such as health) [32] and participation in digital markets [31,34]. In this sense, specialized literature conceives these divides as a contemporary manifestation of social marginality [39], closely linked to forms of energy and multidimensional poverty [15], in which the most affected households face greater difficulties in sustaining processes of digital inclusion and, consequently, in participating fully in society [33]. In particular, studies such as Wang et al. [26] point out that energy poverty increases levels of depression among individuals and reduces the perceived usefulness and importance of the Internet—its use and appropriation as a key resource in contemporary societies for the reproduction of capital.

In this regard, it is emphasized that the growing universalization of ICT access among different social strata can paradoxically contribute to an increase in digital divides in the region [10]. This is because, in order to truly reduce inequalities, it is necessary to promote both objective conditions (such as the availability of updated devices and reliable energy sources to ensure their use) and subjective digital conditions, related to the effective use and real appropriation of these tools. If the expansion of coverage is promoted without parallel development of digital skills that enable functional use of these technologies in areas such as work, education, finance, or health, the gaps between those sectors possessing the necessary capabilities to generate capital (human, social, economic, cultural, or symbolic) and those unable to fully integrate into the digitalization of society and institutions will widen [17,40,41].

In this context, the literature highlights that households with a computer tend to exhibit higher levels of connectivity than those without one [44]. The availability of such equipment is associated not only with higher access levels but also with greater appropriation of ICT within the household, as it is often linked to higher digital skills for developing activities aimed at generating and enhancing human capital—an aspect that proved essential during the pandemic [45,46]. Consistent with this, computers (or similar devices, such as tablets) show lower household penetration than mobile phones with connectivity, since the latter offer greater versatility and require fewer technical skills to operate. Specifically, previous studies [47,48,49] suggest that mobile phones with Internet access are the most widespread technology among low-income households and individuals as they are more affordable, portable, and easier to use than computers. Moreover, they have the advantage of connecting to the Internet through mobile broadband, which means that subscribing to a fixed broadband service at home is not required to gain connectivity [43].

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s marked the beginning of a period characterized by profound changes in modes of human interaction, with ICT becoming a key element across multiple dimensions of daily life, productive development, and social organization [26]. However, this series of transformations also exposed the significant divides in ICT availability and effective use across Latin America and the Caribbean [3,13]. Before the pandemic, although these tools were already part of people’s interaction networks, they had not yet become an essential pillar in shaping educational and occupational trajectories, nor in other services and opportunities that are now closely tied to population development [10,14].

Although since the 2010s there had been a steady increase in scientific publications focused on studying digital divides, between 2015 and 2021, a notable rise in the frequency of such works was recorded [10,50]. These contributions have focused on regional inequalities in coverage, the implementation of public policies aimed at promoting digital inclusion, and discussions emphasizing that it is not only necessary to guarantee objective access conditions to these tools, but also crucial to foster the development of digital skills (subjective conditions) for their effective use in an increasingly digitalized world [41,51,52].

In recent years, in addition to classic quantitative studies estimating variations in digital inequality and their dynamics across social groups, Latin American and Caribbean literature has incorporated qualitative contributions, mostly developed from theoretical-philosophical approaches [10,26,30,39,41]. These studies have specifically examined individuals’ perceptions of heterogeneities in ICT coverage and appropriation, as well as analyses that, from epistemological and discursive perspectives, reflect on the implications of these divides for sustainable development, highlighting the relevance of both capitalist and humanist perspectives in the debate on digital inclusion.

In contrast, the number of studies dedicated to examining digital disparities among smaller population units (such as departments, municipalities, or census tracts) remains considerably lower—both globally and regionally [17,18,19,20]. One of the main factors behind this trend lies in the limited availability of data sources providing information on the coverage or appropriation of these resources at more disaggregated geographic scales, since this phenomenon has been predominantly studied through surveys and administrative records [11,12,13,14,15,16].

2.2. ICTs and Digital Inclusion Policies in Argentina

In the specific case of Argentina, significant progress has been made throughout the 21st century in reducing inequalities in ICT coverage. By the early 2020s, the country had positioned itself as one of the nations in Latin America and the Caribbean with the highest levels of access [8,9]. Estimates by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) [53], based on data from the Permanent Household Survey for the fourth quarter of 2024, indicate that approximately 60% of households have at least one computer and over 93% have Internet access. At the regional scale, the lowest coverage levels are found in the Northwest (NOA) and Northeast (NEA) of Argentina—areas that have historically exhibited higher rurality, lower relative development, and greater sociodemographic vulnerability [54,55]. In contrast, the highest levels of access are observed in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (AMBA), Pampeana, and Patagonia—regions characterized by greater urbanization and better living conditions, as evidenced by higher levels of production, literacy, schooling, participation in the formal labor market, and, overall, lower levels of material and income deprivation [56,57].

According to estimates from ECLAC [43], by 2023 approximately 93.1% of households in the lowest income quintile had some form of connectivity, while coverage reached 98% among the highest-income households. Furthermore, ECLAC’s data indicate that, beyond having higher broadband connectivity than the regional average (both fixed and mobile), Argentina’s relative number of mobile connections is close to that of the European Union—between 118 and 125 mobile connections per 100 inhabitants, respectively.

Most reports and scientific articles addressing this topic in Argentina have focused on estimating quantitative indicators, typically disaggregated at the national or regional scale, as they rely on data derived from surveys and administrative records [11,12,13]. Within this framework, notable studies have analyzed ICT coverage and effective use according to sociodemographic characteristics, examining the relationship between digital inequalities and the population’s socioeconomic strata. Consistent with global and regional evidence [15,31,32,33,34,35], these studies indicate that groups with higher education levels, belonging to wealthier segments and generally residing in urban areas with better housing and income conditions, tend to display higher levels of ICT access and appropriation [3,11,13,15]. Within this context, particular attention has been given to studies that examined the dynamics of this phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic, comparing ICT access in 2020–2021 with previous years or analyzing monthly variations during the health emergency [1,3,12,14,55], as well as those addressing gender-based inequalities in ICT coverage and appropriation during the same period [58,59].

Complementing these quantitative approaches, qualitative studies—mainly through theoretical-discursive analyses, systematic literature reviews, and historical reconstructions (often combined with quantitative indicator estimation)—have examined the implementation of digital inclusion policies in Argentina and their potential impact on expanding ICT access [3,4,5,6,7]. Other works, such as those by Moreira et al. [60] and Benítez Larghi et al. [61], based on qualitative approaches using interviews and interpretive analyses, explore the experiences and perceptions of actors involved in digital inclusion programs (such as Conectar Igualdad), providing key insights into the processes of technological appropriation and the persistence of inequalities in access and effective use of ICTs for human capital and relative wealth generation.

More recently, the contribution by Batiston et al. [62], based on a series of open interviews and the systematization of news and articles, examined the strategies employed by several public universities in Argentina to reduce digital inequalities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The selected institutions were the National University of Salta (UNSa), the National University of Rafaela (UNRaf), and the National University of the Arts (UNA). This study, like most research addressing digital divides in the context of the pandemic [1,3,45,46], suggests that despite the strategies implemented by the national government and universities, differences in access to and effective use of digital tools intensified (or at least became more visible), deepening inequalities across educational and labor spheres, as well as in other rights, such as communication.

According to Califano [3], although pro-market policies during the 1990s promoted an increase in access to basic telephone services, their implementation by the private sector—primarily oriented toward guaranteeing coverage among more urbanized and developed populations—contributed to widening the gaps, as they failed to address service availability in rural and less developed areas. During the 2000s, a gradual shift began in the State’s role, moving from a merely regulatory function toward greater participation in planning and financing connectivity infrastructure, laying the foundations for the digital democratization policies that would consolidate in subsequent years [4,5,6,7]. In line with this shift, initiatives developed during the 2010s primarily aimed to ensure both the expansion of ICT coverage (objective conditions) and the development of digital skills among the population (subjective conditions), with the goal of promoting the effective use of these tools in learning, social participation, and socioeconomic development processes [10,11,12,13,14].

Specifically, under Decree No. 1552/2010, the Argentina Conectada National Telecommunications Plan [4,5] was launched, promoting two key initiatives between 2010 and 2015 (during Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s second presidential term) that contributed to improving both the objective and subjective conditions for reducing digital divides: (1) the deployment of the Federal Fiber Optic Network (REFEFO), operated by ARSAT, aimed at addressing regional imbalances and extending broadband coverage to previously disconnected localities; and (2) the Conectar Igualdad program, which distributed laptops to secondary school students and teachers to foster technological and educational appropriation. Subsequently, as noted by Califano [3], under the Federal Internet Plan, fiber-optic infrastructure expansion continued between 2016 and 2019 (during Mauricio Macri’s presidency), albeit with lower public investment [6,7]. Finally, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (at the beginning of Alberto Fernández’s presidency), Decree 690/2020 declared telecommunications and Internet services as essential, reinforcing infrastructure and promoting connectivity as a right to guarantee access to education, work, and basic services.

Within this framework, despite the progress achieved since 2010, the sudden dependence on ICTs during the health emergency revealed significant inequalities among social groups and between urban and rural areas across the country [12,14,45], as well as the urgent need to develop specific strategies to reduce these disparities [1,50,51]. A key step in this task is to generate indicators that provide information on ICT access for populations at higher levels of spatial disaggregation—such as departments, municipalities, census tracts, and blocks. However, since most studies rely on survey-based data, few have analyzed spatial autocorrelation patterns at subnational divisions below the provincial level, employing spatial association indicators such as the Global and Local Moran’s Index [23,63,64,65].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methodological Approach

This quantitative study employed a descriptive, ecological, and spatial approach to analyze digital divides in households in Argentina during 2022. This methodological framework facilitates the characterization of ICT coverage according to sociodemographic characteristics, thereby enabling the identification of territorial patterns of inequality. These patterns are derived through the utilization of geospatial and statistical tools.

A number of recent studies have demonstrated the value of spatial analysis in identifying concentrations of digital poverty and territorial segmentation of technological infrastructure [8,9,13,23,64,65]. However, the utilization of this analytical approach in the context of investigating inequalities in digital coverage in Argentina remains understudied. In the context of this study, sociodemographic data from the 2022 National Population, Household and Housing Census were integrated with Geographic Information System (GIS) technology and the estimation of the Moran’s Index (global and local), with the objective of analyzing disparities in ICT access between regions in Argentina and identifying spatial association trends at the departmental geographic scale.

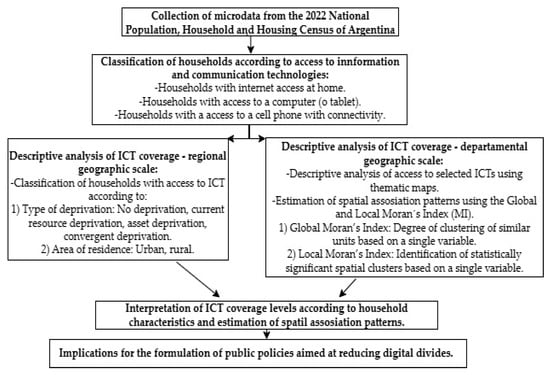

The subsequent flowchart (Figure 1) illustrates the methodological approach employed in the analysis of digital divides in Argentina during 2022.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the study of digital divides in Argentina (2022).

3.2. Case Study: Argentina

Argentina has been observed to demonstrate higher levels of digital connectivity coverage in comparison to other countries within the Latin American and Caribbean regions [43]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the implementation of public policies aimed at mitigating digital divides, such as the Conectar Igualdad program and REFEFO [5,6,7,8]. However, these initiatives have had limited success in addressing existing inequalities, particularly in rural and peripheral regions [3,14]. The dearth of studies that have examined disparities in access to ICTs in Argentina underscores the necessity to scrutinize their dissemination with respect to the sociodemographic characteristics of households (deprivation and area of residence) and identify patterns of spatial autocorrelation at the departmental level. This endeavor is undertaken with the objective of contributing to the formulation of efficacious public policies that are targeted towards specific regions.

3.3. Data Source and Variables

The source of information used was the 2022 National Population, Household and Housing Census, conducted on 18 May by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC) [31], whose microdata were processed through the Redatam Web platform. The main variables selected were: (1) The household has Internet access in the home; (2) The household has a computer (or tablet); (3) The household has a cell phone with Internet access. These variables were analyzed at two scales: regional and departmental.

3.3.1. Analysis at the Regional Scale

First, a comparative descriptive analysis was carried out among the six statistical regions of the country (these are presented in Section 3.4. Sociodemographic characterization of Argentina), differentiating the percentages of ICT access according to household deprivation and residence characteristics [54,66] (Supplementary Materials). In the first instance, households were classified according to the four categories of the Household Material Deprivation Index (HMIH): (1) Households with no deprivation: they do not present deficiencies in either of the two dimensions of the HMIH (current resources and patrimonial), meaning that they have both sufficient economic capacity and adequate patrimonial conditions; (2) Households with deprivation due to current resources: they present insufficiency in their economic capacity to cover basic needs, although their patrimonial conditions remain within the minimum adequate standards; (3) Households with patrimonial deprivation: they present deficiencies in the patrimonial dimension, such as inadequate housing or durable goods, but have sufficient current resources to cover basic needs; (4) Households with convergent deprivation: they simultaneously present deficiencies in both current resources and patrimonial dimensions, representing the most intense form of material deprivation.

Households were also differentiated by area of residence: (1) Urban households: located in localities with more than 2000 inhabitants or with a population density that allows the concentration of services and urban facilities; (2) Rural households: located in localities with fewer than 2000 inhabitants or dispersed throughout the territory, where agricultural activities predominate and the concentration of services is lower.

This stage made it possible to identify general trends and regional differences, following approaches similar to those proposed in previous studies [3,14].

3.3.2. Analysis at the Departmental Scale and Spatial Analysis

At the departmental level (528 units), in the first instance, thematic maps of the percentages of households with access to the three ICTs considered for this study were constructed using Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) 3.40 software. Subsequently, the Moran’s Index (global and local) was constructed using GeoDa 1.22 software, with the objective of detecting statistically significant spatial autocorrelation patterns [56,57].

By constructing the Moran’s Index in its global version, the degree of agglomeration of units of analysis with similar characteristics by the same ICT coverage variable was estimated. Values closer to 1 indicate a stronger positive spatial autocorrelation for the variable. Consequently, the estimation of the Moran’s Index in its local version made it possible to identify spatial clusters, i.e., units of analysis surrounded by neighbors with similar characteristics for the same variable. The statistically significant units were classified into: (1) High-High (areas with high access surrounded by similar areas; positive spatial autocorrelation); (2) Low-Low (areas with low access surrounded by similar areas; positive spatial autocorrelation); (3) High-Low and Low-High (areas with opposite values to their neighbors; negative spatial autocorrelation).

The queen contiguity criterion was used to define neighborhoods, considering as neighbors those analytical units (departments) that shared at least one common point, either a vertex or a boundary. This criterion was chosen because it captures all possible neighboring relationships, including units that only touch at vertices. Unlike distance-based matrices, queen contiguity ensures that no direct neighbor is excluded, which is essential for accurately identifying spatial clusters of ICT access at the departmental level [64,65]. Furthermore, this approach is consistent with the literature on spatial autocorrelation and inequality analysis, and it has frequently been applied even at the level of census tracts [63]. Statistical significance was evaluated using a threshold of p ≤ 0.05.

3.4. Sociodemographic Characterization of Argentina

The Argentine Republic is characterized by the diversity of its populations, marked by social and cultural differences that historically have been associated with its heterogeneous levels of economic development and urban expansion [54]. At the subnational level, the provincial geographic scale in Argentina is composed of 24 jurisdictions: 23 provinces and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (CABA), which has a constitutional status comparable to that of a province. In the case of the departmental scale, Argentina has 528 departments, which are intermediate administrative units between the provincial and municipal levels.

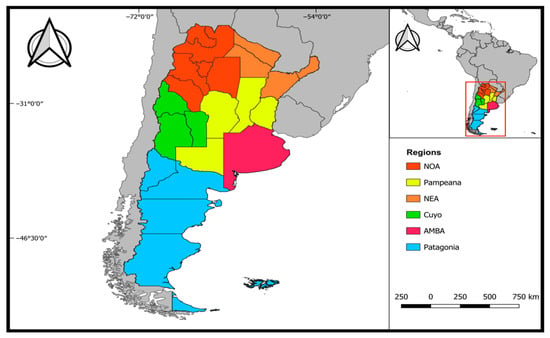

The INDEC traditionally groups the provinces into six regions, whose distribution is shown in Figure 2 and is organized as follows [66]: Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (AMBA): Buenos Aires and CABA; Northwest Argentina (NOA): Catamarca, Jujuy, La Rioja, Salta, Santiago del Estero and Tucumán; Northeastern Argentina (NEA): Corrientes, Chaco, Formosa and Misiones; Pampeana: Córdoba, Entre Ríos, La Pampa, Santa Fe; Cuyo: Mendoza, San Juan and San Luis; Patagonia: Chubut, Neuquén, Río Negro, Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego.

Figure 2.

Map of Argentina differentiated between regions.

Data from the 2022 Population, Households and Housing Census [54] indicate that the country has 15,932,302 households (in private homes). Among them, 41% are concentrated in the AMBA, 21% in the Pampean region, between 11% and 9% in the NOA and NEA, and between 7% and 6% in Cuyo and Patagonia. In terms of territorial distribution (urban–rural), 96% of households in the national total are located in urban areas. At the regional level, all populations exceed 92% of households located in urban areas.

In relation to the distribution of households according to the HPI criteria, in the national average, 66% of households show no type of deprivation; 16% show deprivation due to current resources; 10% have patrimonial deprivation; and 8% show convergent deprivation. On a regional scale, AMBA, Pampeana, and Patagonia register 70% of households without any type of deprivation. Consequently, between 14% and 19% show deprivation due to current resources; between 7% and 9% show patrimonial deprivation; and between 4% and 6% show convergent deprivation.

In the case of Cuyo, 61% of households do not show any type of deprivation; 21% show deprivation due to current resources; 9% have patrimonial deprivation; and 8% show convergent deprivation. In contrast, in the NOA and NEA regions, between 49% and 51% of households do not show any type of deprivation; between 15% and 19% show deprivation due to current resources; between 14% and 19% show patrimonial deprivation; and approximately 17% show convergent deprivation.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the percentage of households with access to the Internet, computers (or tablets), and cell phones with connectivity in the regions of Argentina in 2022. On average nationally, the ICT with the highest household coverage was the cell phone with connectivity. In contrast, the computer (or tablet) was the technology with the lowest level of access. Regarding Internet connectivity at home, the percentage of households with access to this service fell between those with a cell phone with connectivity and those with a computer (or tablet).

Table 1.

Percentage of households according to access to Internet, computer (or tablet) and cell phone with connectivity at regional level in Argentina during 2022.

Across the regions, at least 83% of households had access to cell phones with connectivity; more than 60% had Internet access, and at least 42% had a computer (or tablet). The regions with the highest coverage of digital technologies were the AMBA, Patagonia, and Pampeana. In contrast, the NOA and NEA were the areas most affected by the digital divide, with lower levels of access to ICTs.

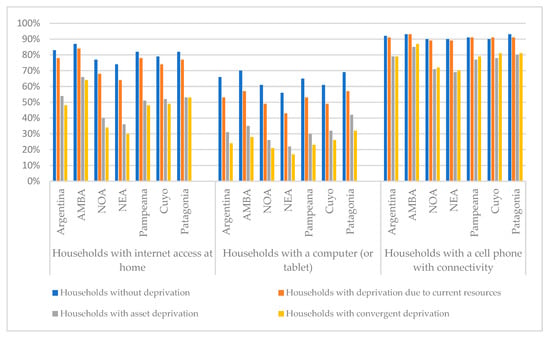

Figure 3 shows the percentage of households with access to the Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity, by type of deprivation, in the regions of Argentina during 2022. Regardless of the type of deprivation, the technology with the highest level of access in households was a cell phone with connectivity. In contrast, the computer (or tablet) was the device with the lowest availability, and Internet access was located at an intermediate point between the coverage of both devices.

Figure 3.

Percentage of households according to access to Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity by type of deprivation at the regional level in Argentina during 2022.

In line with the above, the greatest access to ICTs was observed in households with no deprivation (both nationally and regionally), followed by those with only current resource deprivation. In both types of households, there were similar levels of coverage of the technologies studied. In contrast, households with patrimonial and convergent deprivation had more limited access to digital technologies.

Consequently, it is noteworthy that the availability of cell phones with connectivity registered the highest coverage thresholds among the ICTs analyzed. In addition, it presented similar access percentages in the four categories of household deprivation, both in the national average and in the regions studied. In households without deprivation and in those with current resource poverty, the percentage of availability of this service was around 90%. In households with patrimonial and convergent deprivation, the values ranged between 72% and 87%. This trend suggests that the cell phone with connectivity was the ICT with the highest penetration level and the least inequality in its distribution among the different types of households by deprivation.

In contrast, the availability of Internet and a computer (or tablet) showed marked differences between households without deprivation and those with patrimonial or convergent deprivation, especially in the NOA and NEA regions. In these two regions, computer coverage in households with multiple poverty varied between 17% and 21%. In contrast, in other regions with greater access (such as the AMBA, Pampeana, and Patagonia), the percentages were between 28% and 32%. On the other hand, in households without any type of deprivation according to regions, access to computers was between 56% and 71%, while the availability of Internet in the home was between 74% and 87%.

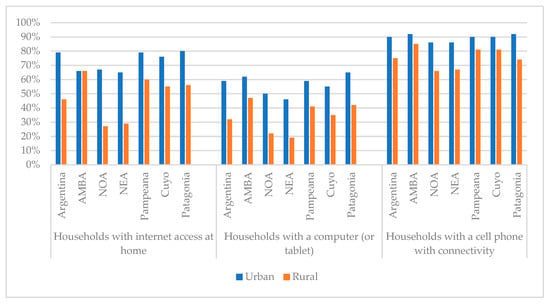

Figure 4 shows the percentage of households with access to Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity, by area of residence (urban–rural), in the regions of Argentina during 2022. At the national and regional level, ICT coverage was notably higher in households located in urban areas compared to those residing in rural areas. The narrowest differences in access by territorial area were found in the case of cell phones with connectivity, while the most pronounced gaps were identified in the case of computers (or tablets). Internet access in the home presented intermediate coverage between the two technologies mentioned (in both areas of residence).

Figure 4.

Percentage of households according to access to Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity according to territorial area (urban–rural) at the regional level in Argentina during 2022.

The greatest inequalities between urban and rural sectors, as well as the smallest percentages of access in both areas of residence, were found in the NOA and NEA regions. In contrast, the smallest gaps between territorial areas were found in AMBA, Pampeana, and Patagonia. In the urban areas of the national average and the aforementioned regions, the percentage of households that hade a cell phone with connectivity was around 90%; Internet access in the home reached approximately 80%; and computer (or tablet) ownership was between 60% and 65%.

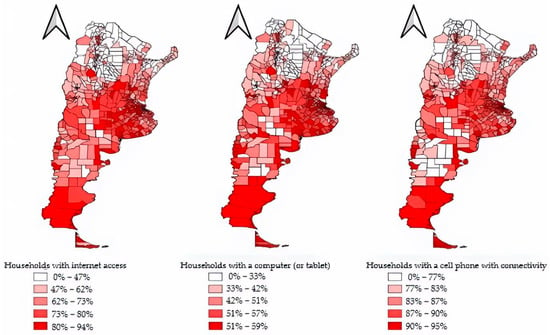

Figure 5 shows the percentage of households with access to the Internet, computer (or tablet) and cell phone with connectivity in the departments of Argentina during the year 2022 in thematic cartographies. The highest coverage was recorded in the case of cell phones with connectivity, with values ranging between 90% and 95% in the fifth quantile. This was followed by Internet access in the home, with a distribution of 80% to 94% in the same quantile. In last place was the availability of computers (or tablets), which registered values in the fifth quantile ranging from 50% to 89%.

Figure 5.

Map of percentage of households with access to the Internet, computer (or tablet), and cellular with connectivity in Argentina’s departments during 2022.

Regarding the pattern of access to ICTs in the country’s departments, it was observed that the three digital technologies presented similar coverage distributions among the populations, although with different percentage intensities. In line with this, the two quantiles with the lowest percentage of access to these technologies were mainly concentrated in the departments of the NOA and NEA regions. Specifically, the lowest levels of access (first quantile) were identified in the departments of the provinces of Santiago del Estero, Jujuy, Salta and the northwestern area of Catamarca (NOA), as well as in the jurisdictions of Formosa and Chaco (NEA). In the case of cellular access with connectivity at home, low levels were also observed in some populations of Chubut (Patagonia).

In the case of the three quantiles with the highest ICT household coverage, their distribution was mainly identified in the AMBA, Pampeana, and Patagonia regions. Specifically, the departments with the greatest access (fifth quantile) were located in the jurisdictions of CABA and Buenos Aires (AMBA), Córdoba, Santa Fe, and La Pampa (Pampeana), as well as in Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego (Patagonia).

Table 2 presents the level of spatial autocorrelation (based on the global Moran’s Index) for the percentage of households with access to the Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity in the departments of Argentina during the year 2022. The highest levels of spatial autocorrelation were recorded for household Internet access (0.71), followed by computer (or tablet) coverage (0.69). The lowest degrees of agglomeration of similar units were identified in the case of ownership of at least one cell phone with connectivity (0.55).

Table 2.

Global Moran’s Index according to percentage of households with access to Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity at the departmental level in Argentina during 2022.

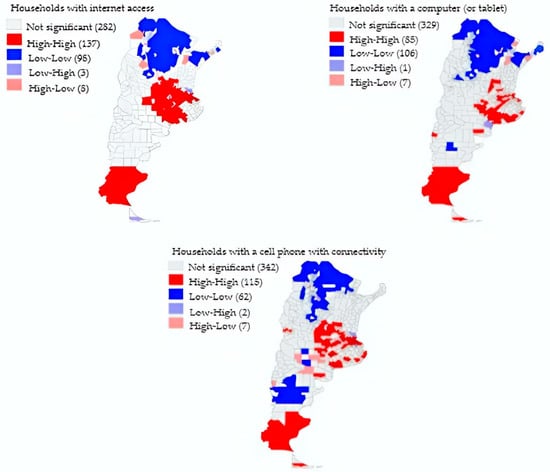

Figure 6 shows in a series of cartographies the spatial autocorrelation patterns of the local Moran’s Index according to the percentage of households with access to the Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity in the departments of Argentina during the year 2022.

Figure 6.

Spatial autocorrelation map (local Moran’s Index) according to percentage households with access to the Internet, computer (or tablet), and cell phone with connectivity in the departments of Argentina during 2022.

In the first instance, it can be seen that the ICT that registered the highest number of departments with positive spatial autocorrelation was Internet coverage in the home, with a total of 235 positive clusters, of which 137 corresponded to departments with high-high values statistically significant, while 98 departments showed low-low values. Consequently, the technology that presented the second largest number of departments with positive autocorrelation was the availability of at least one computer (or tablet) at home, with a total of 191 positive clusters, of which 85 presented high-high values and 106 low-low values.

In the third instance, cell phone with connectivity at home was the technology that presented the lowest frequency of cases with positive spatial autocorrelation, with a total of 177 positive clusters. However, this third ICT registered a greater number of clusters with high-high values (115) compared to the coverage of computers (or tablets) in homes, as well as a lower number of cases with low-low values. This particularity suggests a higher penetration of this technology in households with respect to computers (or tablets), as well as a lower territorial concentration of households lacking this resource.

Finally, when examining the distribution of the positive clusters, it can be seen that the departments with low-low values were located mainly in the provinces of Santiago del Estero, Salta, and Jujuy (NOA), and in Formosa, Chaco, and part of Misiones (NEA). In the case of cellular access with connectivity at home, this type of cluster was also found in Chubut (Patagonia). In contrast, populations with positive autocorrelation and high-high values were especially agglomerated in the provinces of Buenos Aires and CABA (AMBA), Córdoba, Santa Fe, and La Pampa (Pampeana), and Santa Cruz (Patagonia).

5. Discussion

Currently, reducing digital divides is an essential component in promoting sustainable development [24,25]. The expansion of ICT access has consolidated as a key factor in economic growth [35], reducing social inequalities [10], and enabling the effective exercise of human rights [32], especially following the pandemic, which amplified the role of ICTs in people’s daily lives [1,45,46]. In this context, it is necessary to have precise indicators to analyze household ICT access, considering territorial and socioeconomic inequalities, in order to design targeted public policies for specific groups [3]. In line with this, the present study provides estimates of ICT access in Argentine households (covering the entire population), examining its distribution according to deprivation characteristics and urban–rural residence (as proxies for differences between social groups [54]) at the regional geographic scale, and identifying patterns of spatial association at the departmental level.

The main results indicate that differences in ICT coverage are associated with geographical disparities between regions [59], as well as with the type of deprivation and area of residence of households [10,11,12,13,14]. Initially, the AMBA, Pampeana, and parts of Patagonia regions exhibited the highest access levels, with mobile phone ownership with connectivity leading, followed by home Internet access and computers (or tablets) (Table 1). In contrast, NOA and NEA showed the lowest coverage levels, particularly for computers and Internet access, although mobile phones maintained relatively high penetration compared to other regions. These findings reflect interregional gaps, with populations in rural areas and higher exposure to sociodemographic vulnerability—reflected in household deprivation [53,54,56,57]—displaying lower ICT coverage. In this context, digital divides are not only a reflection of poverty and social marginalization [58,59], but also a phenomenon that contributes to reproducing these conditions among populations lacking access to these resources [15].

Consequently, in line with previous studies [11,12], ICT access levels among regions also vary according to the type of deprivation and area of residence (urban–rural) (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Households without deprivation showed the highest coverage, followed by those with current resource deprivation, while households with asset deprivation and convergent deprivation (both current resource and asset deprivation) had more limited access, particularly to computers and Internet. Similarly, urban households had higher access thresholds than rural ones, with mobile phones exhibiting smaller disparities between areas, suggesting that this technology is more evenly distributed than the other examined ICTs.

The trends indicated by the indicators reinforce the hypothesis that households located closer to urban conglomerates [16,20] and with lower exposure to socioeconomic backwardness [13,14,15] tend to have greater ICT coverage than those in rural areas more affected by poverty-related characteristics [27,30,31]. These differences reflect not only material inequalities but also structural mechanisms of social and territorial exclusion that limit sustainable development. Lack of access to these resources is not only a manifestation of multidimensional poverty but also a factor potentially restricting inclusion and social mobility, reproducing the vulnerability conditions experienced by populations [15]. Within this framework, implementing public policies aimed at reducing digital divides—at least regarding overcoming objective availability conditions [41,45,52]—is fundamental to removing barriers limiting technological integration in a society increasingly dependent on ICTs [10], as well as reversing conditions that reinforce these inequalities [23], particularly among households most affected by material and convergent deprivation.

In line with the above, and considering the Argendata [67] data on the percentage contribution of the gross domestic product (GDP) of Argentina’s regions and provinces in 2022 (whose values are presented in Table A1 of the Appendix A), it was observed that, as in the analysis of households according to type of deprivation and area of residence, the regions that recorded the highest levels of access to ICTs were those that made a greater relative contribution to national production and the economy: AMBA, Pampeana, and Patagonia, respectively. In contrast, the populations that exhibited a lower relative contribution to GDP were also those with lower levels of access to these technologies, a trend that became more evident in the NOA and NEA regions. This pattern suggests that, as noted by previous studies on the digital economy and development [68,69,70], the availability and use of ICTs are closely linked to the level of economic development of territories. This relationship has also been documented for countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, where digital infrastructure and broadband expansion tend to be concentrated in the most economically dynamic regions [71,72].

At the departmental level (Figure 5), thematic maps revealed a heterogeneous distribution of ICT access. Populations with the lowest access were identified in NOA and NEA, with most cases concentrated in the first quintile, reaching maximum access levels of up to 47% for Internet, 33% for computers (or tablets), and 77% for mobile phones. In contrast, departments with higher coverage were located in AMBA, Pampeana, and parts of Patagonia, predominantly in the third to fifth quintile, where the highest quintile showed a minimum access of 80% to Internet, 57% to computers (or tablets), and 90% to mobile phones. While differences exist between populations, the spatial disaggregation analysis shows that the NOA and NEA populations exhibited a relatively homogeneous low-access pattern (most departments in the lowest quintile), while AMBA showed uniformly high coverage (most departments in the fourth and fifth quintiles), and other regions displayed more heterogeneous ICT availability.

The most pronounced gaps between extreme quintiles (first and fifth) were observed for computers (or tablets). This trend, similar to the regional analysis by deprivation type and territorial area, suggests that although access to this technology has lower overall penetration, its availability is concentrated in households less affected by deprivation, closer to urban centers, and in populations with better overall welfare conditions [51,52,53,54]. In this regard, using the GDP estimates provided by ArgenData [67] at the provincial level as a proxy for departmental differences (whose values are presented in Table 1 of the Annex), it was observed that although the relationship between economic growth and access to ICTs is not entirely solid in the populations studied (for example, in the case of Santa Cruz, where GDP—although not the highest in Patagonia—is associated with the highest ICT coverage thresholds in the region), the cases that contributed the most to the structure of the Argentine economy (such as CABA and the Province of Buenos Aires in the AMBA, or Córdoba and Santa Fe in the Pampeana region) exhibited higher levels of access to ICTs. In contrast, the populations with lower GDP contributions tended to show lower levels of coverage of these technologies, as is the case in most of the populations analyzed in the NOA and NEA regions.

Consistent with previous studies [45,46], this dynamic may be related to the fact that households with this type of technology generally have higher digital competencies for effective ICT use and more active participation in digital inclusion processes (subjective conditions of appropriation) [47,48,49]. These households also tend to have higher educational and income levels, lower vulnerability to housing deficits and inaccessibility to basic services (health, energy), and less exposure to social marginalization [11,29,32,33]. Despite policies like the Conectar Igualdad Program, implemented since the early 2010s to provide school computers, evidence shows that significant inequities in technology coverage persist among the population [5,7].

Increasingly, mobile phones with connectivity are becoming the essential digital inclusion technology, even in rural areas [43,69]. The lower availability of computers (or tablets) compared to mobile phones may relate to the latter’s greater versatility. Previous studies [47,48,49] note that Internet-enabled mobile phones are among the most widespread ICTs among households and individuals in vulnerable socioeconomic strata, being more affordable, portable, and easier to use than other technologies, such as desktop or laptop computers. The smaller gaps observed in mobile phone access—across deprivation types and urban–rural areas—may be associated with their lower cost, multifunctionality, and ease of developing digital competencies [73]. Additionally, mobile phones can access the Internet via mobile broadband, eliminating the need for a fixed household Internet connection. This trend is reflected in ECLAC estimates [43], which show that in both the Argentina and the Latin America and Caribbean regional average, the smallest gaps compared to EU countries are in mobile broadband subscriptions, contrasting with wider disparities in fixed household Internet coverage.

High fixed Internet access in households of AMBA, Pampeana, and parts of Patagonia (observed in the fifth quintile in Figure 5) can be linked to public policies since the early 2010s that promoted connectivity expansion as a key component in educational and labor trajectories [5,7,21,62], recognized during the pandemic as essential under Decree 690/2020 [3]. However, despite these advances, the study found significant gaps in fixed Internet access at the departmental level in NOA and NEA, as well as among rural households and by deprivation type at the regional level (Figure 2 and Figure 3). While connectivity policies may have partially reduced inequalities in more disadvantaged populations, their deployment has not fully closed Internet access gaps, similar to the patterns observed for computers (or tablets) [47,48,49]. The low fixed Internet coverage in some areas may also be explained by the increasing preference for mobile broadband subscriptions over fixed Internet at home, as shown by ECLAC estimates [43].

Spatial autocorrelation analysis reinforces the trends observed in thematic maps (Figure 5). Global Moran’s Index estimates (Table 2) indicate high autocorrelation for Internet and computers, while mobile phones showed lower clustering [63]. Local Moran’s Index patterns (Figure 6) revealed low-access clusters in NOA, NEA, and some Chubut departments (Patagonia), and high-access clusters in AMBA, Pampeana, and parts of Patagonia, particularly numerous in AMBA. Although mobile phones showed lower spatial clustering of high-access cases than computers, they displayed a higher number of high-high clusters, indicating more homogeneous penetration less dependent on household geographic location.

Overall, these findings indicate that, while ICT distribution inequalities persist, mobile phones have the highest coverage and lowest inequity among Argentine households, partially overcoming social and territorial exclusion mechanisms in high-vulnerability departments. Mobile phone access emerges as a key technology to reduce digital inequalities and mitigate multidimensional poverty and social marginalization. Their affordability (cost-functionality ratio) ensures objective coverage, while ease of use and rapid adaptation facilitate overcoming subjective barriers to effective appropriation in areas such as education [16], work, health [32], and finance [33]. In contrast, computers (or tablets) show lower household reach, with more limited portability, functionality, and ease of skill adaptation for effective digital use [12,45,46].

Applying spatial association techniques was crucial for interpreting thematic maps and ensuring the observed patterns were statistically significant rather than random. Global and Local Moran’s Indices were constructed to estimate the spatial autocorrelation of ICT coverage, determining whether patterns reflected statistically significant spatial structure (χ2 test, p ≤ 0.05) or random distribution. Unlike descriptive spatial tracking (e.g., Figure 5), the Global Index quantifies the degree of clustering, while the Local Index identifies clusters of low and high prevalence, providing a solid basis for detecting areas with digital vulnerability [23,63,64,65].

This approach represents a novel contribution for designing public policies to mitigate barriers to sustainable development in specific populations, providing key information to identify low- and high-access clusters at the departmental level [17,18,19,20]. It also supports locating areas with other sociodemographic vulnerabilities linked to digital exclusion, such as unfavorable educational conditions, current resource deficits, limited formal labor participation, and insufficient energy infrastructure, among other determinants of social inequality. Identifying populations with lower coverage is essential for reducing inequalities, as highlighted by Lythreatis, Singh, and El-Kassar [30], consistent with SDG 10 [23].

The data source was the 2022 National Population, Households, and Housing Census [66], providing comprehensive coverage and high spatial resolution rarely used in Latin American digital divide studies [17,18,19]. This approach overcomes the representativeness limitations of household surveys [11,12,63], which only provide expanded samples for regional and provincial averages, mostly covering major urban areas [53]. An additional advantage is its potential replicability in other Latin American countries with georeferenced census data, facilitating regional comparisons and identifying sociodemographic vulnerability clusters, reducing poverty and inequality, and promoting sustainable development [15,39].

Compared to survey-based methodologies [11,12,13,14,15], this approach offers broader representativeness, enabling the identification of digital exclusion patterns and poverty-related characteristics at finer geographic scales (departments, blocks, and census tracts), allowing more detailed future analyses. The data also enabled examining digital access by deprivation type and residence area, proxies for social group differences in access [54]. Previous regional and Argentine studies adopting similar approaches mostly relied on expanded samples that did not fully capture urban–rural differences or household deprivation.

The 2022 Census microdata are newly available, so estimates of undercoverage are not yet accessible, limiting quality assessment of the data used for indicator construction. A notable limitation is the lack of variables on digital appropriation, essential for evaluating effective digital inclusion [22]. Digital divides are influenced not only by objective ICT coverage but also by subjective appropriation inequalities, linked to effective technology use in increasingly digital environments—particularly post-pandemic—in education and work [1,31,32], digital markets [33,34], health [35], and other areas where information access and reproduction affect individual and collective performance. Several studies warn that ICT expansion [45,46] without parallel digital skill development may paradoxically deepen existing gaps, reproducing inequalities in the capabilities needed to leverage digital benefits [10].

Due to differences between the 2010 and 2022 Census variables, temporal changes and causal links between specific public policies and ICT access inequalities could not be assessed. Internet connection type was also unavailable, limiting differentiation between low- and high-quality connectivity [3]. Simple Internet access does not necessarily reflect speed, stability, or continuity, which directly affect usage quality, digital participation opportunities, and effective household inclusion. Future research should complement the 2022 Census data with specialized digitalization surveys to explore access patterns, service quality, and ICT appropriation.

Finally, a limitation in identifying spatial autocorrelation patterns is that the Moran’s Index (Global and Local) was not estimated by household deprivation or residence area. This prevented bivariate autocorrelation analysis between ICT coverage and selected sociodemographic variables. Future work will incorporate this at departmental and census-tract levels to deepen the understanding of access inequalities and support targeted public policy design.

Identifying territorial digital exclusion clusters can guide infrastructure investment and access programs in critical areas, combining connectivity strategies with interventions in education and digital equipment provision [28]. The geospatial methodology can also assess territorial accessibility to other essential services dependent on digital connectivity, including telemedicine, virtual education, smart energy management, environmental monitoring, and water and gas management [8,74]. Applying this methodology in other countries can contribute to SDG progress assessment [23].

6. Conclusions

This study found that ICT access gaps in Argentina in 2022 were linked to household deprivation conditions and urban–rural residence (proxies for social group differences [54]) at the regional level. Analysis of relative frequencies and spatial autocorrelation patterns in smaller population units showed some homogeneity in access inequalities among departments within particular regions.

NOA and NEA regions had the lowest technology access, especially in rural areas and among populations with high deprivation, particularly those with asset and convergent deprivation. These regions exhibited homogeneous digital exclusion clusters at the departmental scale. In contrast, AMBA, Pampeana, and parts of Patagonia showed higher ICT access associated with lower deprivation and rurality. In line with the above, the GDP data provided by Argendata [67] made it possible to identify that the regions contributing more substantially to the country’s economic structure recorded higher levels of ICT access (AMBA, Pampeana, and Patagonia), whereas populations with a lower contribution exhibited lower levels of coverage of these technologies.

Mobile phones with connectivity emerged as the most widespread ICT, while computers (or tablets) remained the least accessible, especially in high-deprivation, rural areas. Mobile phone penetration relative to computers is associated with affordability, portability, multifunctionality, and the ease of developing digital skills for effective appropriation in highly digitalized contexts—particularly post-pandemic—such as education, work, basic services (health), and participation in digital markets [47,48,49].

GIS and spatial association techniques identified spatial autocorrelation patterns, distinguishing high- and low-access areas. Georeferenced census data at the departmental level proved useful for analyzing digital coverage gaps spatially, especially in smaller territorial units. Estimating these patterns revealed statistically significant digital exclusion and concentration clusters, providing empirical evidence beyond visual map interpretation.

Future research should deepen the analysis of digital divides using the 2022 Census and specialized digitalization surveys, examining both access patterns (objective conditions) and appropriation (subjective conditions). Departmental and census-tract-level analyses, particularly in highly populated urban agglomerations, should evaluate associations between access conditions and sociodemographic vulnerability, considering deprivation dimensions and urban–rural residence, using bivariate spatial autocorrelation patterns and Moran’s Index (Global and Local).

These findings provide a novel contribution for targeted public policy, identifying priority areas for digital infrastructure investment, educational programs, and technology provision to reduce structural inequalities and promote digital inclusion. Full census representativeness and high spatial resolution allow replicating this approach in other Latin American and Caribbean contexts, supporting regional comparability and SDG monitoring [23].

Supplementary Materials

https://redatam.indec.gob.ar/binarg/RpWebEngine.exe/Portal?BASE=CPV2022&lang=ESP (accessed on 2 December 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.F.L. and J.R.G.; methodology, V.F.L.; software, V.F.L.; validation, J.R.G.; formal analysis, V.F.L.; investigation, V.F.L.; resources, J.R.G.; data curation, V.F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, V.F.L.; writing—review and editing, V.F.L.; visualization, V.F.L.; supervision, J.R.G.; project administration, J.R.G.; funding acquisition, J.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNAL).

Data Availability Statement

The data can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author due to restrictions (the project policy).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the institutional support of the Comité de Energía de Córdoba (CEC) of the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios sobre Cultura y Sociedad (CIECS)|CONICET and UNC as well as the Fundación Energía Córdoba. This research was supported by Electrical Machines and Drives (EM&D) from Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Red de cooperación de soluciones energéticas para comunidades, code: 59384.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Relative contribution, expressed as a percentage, of the regions and provinces to Argentina’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2022.

Table A1.

Relative contribution, expressed as a percentage, of the regions and provinces to Argentina’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2022.

| Relative Contribution, Expressed as a Percentage, of the Regions and Provinces to Argentina’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBA | |||||

| 52.2% | |||||

| Buenos Aires | CABA | /// | |||

| 32.5% | 19.7% | ||||

| NOA | |||||

| 7.9% | |||||

| Catamarca | Jujuy | La Rioja | Salta | Santiago del Estero | Tucumán |

| 0.6% | 1% | 0.6% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.0% |

| NEA | |||||

| 4.9% | |||||

| Corrientes | Chaco | Formosa | Misiones | /// | |

| 1.3% | 1.6% | 0.6 | 1.3% | ||

| Pampeana | |||||

| 20.2% | |||||

| Córdoba | Entre Ríos | La Pampa | Santa Fe | /// | |

| 8.5% | 2.8% | 1.1% | 7.8% | ||

| Cuyo | |||||

| 5.6% | |||||

| Mendoza | San Juan | San Luis | /// | ||

| 3.3% | 1.3% | 1% | |||

| Patagonia | |||||

| 9.2% | |||||

| Chubut | Neuquen | Rio Negro | Santa Cruz | Tierra del Fuego | /// |

| 1.9% | 3.5% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.0% | |

| National Total (Argentina) | |||||

| 100% | |||||

Source: Data obtained from Argendata [67].

References

- Galeano Alfonso, S.; Pla, J.L. Clases Sociales y Brechas Digitales. In La Sociedad Argentina en la Pospandemia: Radiografía del Impacto del COVID-19 Sobre la Estructura Social y el Mercado de Trabajo Urbano; Salvia, A., Poy Piñeiro, S., Pla, J., Eds.; Siglo XXI Editores: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022; pp. 175–192. Available online: https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/199670 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Jung, J.; Katz, R.L. Impacto del COVID-19 en la Digitalización de América Latina; LC/TS.2022/177/Rev.1; Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11362/48486 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Califano, B. Políticas y desigualdades en el acceso a Internet durante la pandemia en la Argentina. Tsafiqui—Rev. Científica en Cienc. Soc. 2023, 13, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baladron, M.; Rivero, E. Políticas digitales de democratización en la Argentina 2010–2015. Actas Periodis. Comun. 2017, 21. Available online: https://perio.unlp.edu.ar/ojs/index.php/actas/article/view/3707 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Gvirtz, S.; Torre, E. 1-1 Model and the Reduction of the Digital Divide: Conectar Igualdad in Argentina. In Second International Handbook of Urban Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, M.S. Diez años de continuidad en Argentina: El caso de tendido y operación de la Red Federal de Fibra Óptica entre 2010 y 2020. Rev. Latinoam. Econ. Soc. Digit. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finquelievich, S.; Odena, M.B. Políticas públicas para resolver el acceso diferencial a las tecnologías digitales y la conectividad en Argentina. Rev. Int. Ética Inf. 2022, 32, 1–6. Available online: https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/224083 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Vivienda y Servicios Básicos. 2024. Available online: https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/inequalities/housing-and-basic-services.html?indicator=4623&lang=es (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe)/Observatorio de Desarrollo Digital (ODD). Sobre la Base de World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database, Julio 2023, Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT). Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/observatoriodigital (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Plaza de la Hoz, J.; Espinosa Zárate, Z.; Camilli Trujillo, C. Digitalización y pobreza en América Latina: Una revisión teórica con enfoque en la educación. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, R. Brecha social y brecha digital. Pobreza, clima educativo del hogar e inclusión digital en la población urbana de Argentina. Signo Pensam. 2020, 39, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, P.; Huepe, M.; Trucco, D. Educación y Desarrollo de Competencias Digitales en América Latina y el Caribe (LC/TS.2025/3); Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2025; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/48486 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- García Zaballos, A.; Iglesias Rodriguez, E.; Puig Gabarró, P. Informe anual del Índice de Desarrollo de la Banda Ancha: Brecha digital en América Latina y el Caribe: IDBA 2021; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, J.C.B. El lugar importa: Brecha digital y desigualdades territoriales en tiempos de COVID-19. Una revisión comparativa sobre la realidad argentina, sus provincias y principales centros urbanos. Argum. Rev. Crítica Soc. 2021, 24, 3. Available online: https://publicaciones.sociales.uba.ar/index.php/argumentos/article/view/6977 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Alderete, M.V. Examining the drivers of Internet use among the poor: The case of Bahía Blanca city in Argentina. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.E.; Arévalo-Wierna, C. Brecha y desigualdad digital en la educación argentina. Rev. Colomb. Educ. 2023, 88, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, F.; González-Relaño, R.; Lucendo-Monedero, Á.L. Comportamiento espacial del uso de las TIC en los hogares e individuos: Un análisis regional europeo. Investig. Geográficas 2020, 73, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, J.; Sarkar, A.; Parrish, E. The Latin American and Caribbean digital divide: A geospatial and multivariate analysis. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2021, 27, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, K.J.; Ayeni, B. Análisis basado en SIG de la accesibilidad geográfica a la infraestructura compartida de tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) en una región remota de Nigeria. Rev. Afr. Cienc. Tecnol. Innov. Desarro. 2019, 11, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Mancero, X.; Guerrero, S. Mapeo de la pobreza en América Latina: Experiencias de la CEPAL en la estimación de áreas pequeñas. Rev. CEPAL 2022, 138, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barón, I.F.R.; Montoya, J.C.C.; Cañón, J.S.V.; Rodríguez, J.E.O.; Torres, J.C.G. Análisis espacial de ubicación de antenas para la conectividad mediante la aplicación de herramientas SIG. El Reventón Energético 2023, 21, 7–17. Available online: https://revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistafuentes/article/view/14144/13007 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Di Virgilio, M.M.; Serrati, P. Ciudades inteligentes, brecha digital y territorio: Evidencias a partir del caso del aglomerado Gran Buenos Aires. Territorios 2022, 47, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciones Unidas. Transformar Nuestro Mundo: La Agenda 2030 Para el Desarrollo Sostenible. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/agenda-2030/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Barberá-Gregori, E.; Suárez-Guerrero, C. Evaluación de la educación digital y digitalización de la evaluación. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2021, 24, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz Terra, L. TIC y mundo del trabajo: Desigualdades digitales en Argentina frente a la pandemia del COVID-19. Prácticas Discursos 2022, 11. Available online: https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/212886 (accessed on 2 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pick, J.B.; García-Murillo, M.; Navarrete, C.J. Investigación en tecnologías de la información en América Latina. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2007, 13, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cao, A.; Wang, G.; Xiao, Y. The impact of energy poverty on the digital divide: The mediating effect of depression and Internet perception. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Income disparity and digital divide: The Internet Consumption Model and cross-country empirical research. Telecommun. Policy 2013, 37, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-R.; Ling, K.; Zhang, Y.-J. The carbon emission reduction effect of digital infrastructure development: Evidence from the broadband China policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 434, 140060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S.; Singh, S.K.; El-Kassar, A.N. The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Flamm, K.S.; Horrigan, J. An analysis of the determinants of Internet access. Telecommun. Policy 2005, 29, 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros, D.F.; Moreno, C.M.; Miller, F.D.W.; Omori, R.; MacKinnon, N.J. Assessing access to digital services in health care–underserved communities in the United States: A cross-sectional study. Mayo Clin. Proc. Digit. Health 2023, 1, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, H.; Arcidiacono, M. Empleo y brecha digital de género en América Latina. Rev. Latinoam. Econ. Soc. Digit. 2021, 1, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhrab, M.; Chen, P.; Ullah, A. Digital financial inclusion and income inequality nexus: Can technology innovation and infrastructure development help in achieving sustainable development goals? Technol. Soc. 2023, 76, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, M. Empoderamiento digital como proceso para mejorar la participación ciudadana. Learn. Electron. Digit. Media 2006, 3, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Global Internet Use Continues to Rise But Disparities Remain. United Nations Social Development Network 2024. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/sdn/global-internet-use-continues-to-rise-but-disparities-remain (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Tewathia, N.; Kamath, A.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Social inequalities, fundamental inequities, and recurring of the digital divide: Insights from India. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonaki, M.; Stamatopoulou, G.; Parsanoglou, D. Factors explaining adolescents’ digital skills in Europe. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakopoulou, P.; Hustad, E. Bridging digital divides: A literature review and research agenda for information systems research. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, A. Ciudadanía Económica Cosmopolita; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Solorio, I.; Guzmán, J.; Guzmán, I. Toma de decisiones participativa en el proceso de integración de políticas: Consulta indígena y desarrollo sustentable en México. Policy Sci. 2023, 56, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Indicador 4623—Hogares con acceso a Internet (% del total de hogares). Portal de Estadísticas CEPAL, sección Desigualdades: Vivienda y servicios básicos. 2025. Available online: https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/inequalities/housing-and-basic-services.html?lang=es&indicator=4623 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). CEPALSTAT—Portal de Datos. Indicador 5381, Área 639. Available online: https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html?indicator_id=5381&area_id=639&lang=es (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Marandino, J.; Wunnava, P.V. The Effect of Access to Information and Communication Technology on Household Labour Income: Evidence from One Laptop Per Child in Uruguay. Economies 2017, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, J.; García-Sánchez, J.-N. The Digital Divide of Know-How and Use of Digital Technologies in Higher Education: The Case of a College in Latin America in the COVID-19 Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarry Galvez, D.P.; Revinova, S. Assessing Digital Technology Development in Latin American Countries: Challenges, Drivers, and Future Directions. Digital 2025, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Campbell, S.W.; Ling, R. Mobile Phones Bridging the Digital Divide for Teens in the US? Future Internet 2011, 3, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, P. The Impact of Mobile Broadband and Internet Bandwidth on Human Development—A Comparative Analysis of Developing and Developed Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 16419–16453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa Zárate, Z.; Camilli Trujillo, C.; Plaza de la Hoz, J. Digitalization in Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 1821–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, R.; Ilieva-Trichkova, P. Digitalization and Inequality: The Impact on Adult Education Participation Across Social Classes and Genders. World 2025, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Arancibia, J.; Hochstetter-Diez, J.; Bustamante-Mora, A.; Sepúlveda-Cuevas, S.; Albayay, I.; Arango-López, J. Navigating Digital Transformation and Technology Adoption: A Literature Review from Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinadé Chagas, M.E.; Silva, A.; Fernandes, G.R.; Aguilar, G.T.; da Silva, M.M.D.; Moraes, E.L.; Lottici, I.D.A.; Amorim, J.d.R.d.; de Abreu, T.; Moreira, T.D.C.; et al. The Evolution of Digital Health: A Global, Latin American, and Brazilian Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1582719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]