Abstract

The capacity of exhibitions to transform a city extends over a long period. The expo area is converted into a unique scenario for architecture, diversity, technology, mobility, and culture during the event itself. After the exhibition is over, work continues with the architectural transformations necessary to reconfigure the place into one that responds to the needs of the city and its inhabitants. The collateral actions of urban development through exhibitions involve the regeneration of different areas of the city, such as emblematic areas, and the reconfiguration of its operational systems such as transport, telecommunications, various networks, etc. Universal Expositions have historically served as catalysts for large-scale urban transformation, leaving behind complex spatial, architectural, and infrastructural legacies. However, the long-term integration of former expo sites into the contemporary city remains uneven and insufficiently documented, particularly in the case of Seville, which hosted both the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition and the 1992 Universal Exposition. This research employs a mixed qualitative methodology combining archival investigation, cartographic and photographic analysis, field observation, and research by design. Based on these findings, the paper presents an original architectural and landscape intervention for the degraded area of Isla de la Cartuja, proposing a multifunctional center and botanical garden, a recreational complex that reactivates an abandoned section of the former American Garden. This study contributes to worldwide discussions on mega-event legacies by offering a structured post-expo evaluation framework, identifying lessons for future regeneration processes, and demonstrating how research by design can support the sustainable transformation of such a former event landscape.

1. Introduction

The International Exhibitions (Expos), also known as Universal or World Expositions or International Specialized and Registered Exhibitions, have become emblematic models, adopting visionary urban planning as a strategic component, becoming case studies of urban organization, and providing, through their pavilions and sites, panoramic visions and overviews of the cities of the future [1,2]. Historically, they served also as instruments of territorial modernization, international diplomacy, and speculative urban transformation.

Universal Exhibitions have often left a decisive mark on the cities in which they took place. Over time, the duration and the impact of the exhibitions have changed.

Within this broader discussion, former expo sites constitute unique laboratories for examining the intersection between temporary event-making and permanent urban development.

At first, exhibitions were designed to last 3 to 6 months, and then many of the constructions were demolished (partially or completely most of the time), for example, the cases of London in 1851 and Paris in 1889.

Currently, they are envisioned from the outset as part of the city, later incorporating various functions necessary for the city (a notable example is Lisbon 1998 in Portugal and Zaragoza 2008 in Spain) [3,4,5].

In most cases, some emblematic parts of the exhibitions have remained symbols of the city (for example, in Paris, 1889—the Eiffel Tower, or in Montreal, 1967—the Geodesic Dome). However, the long-term metamorphosis of these sites remains under-explored, particularly in cases where complex governance structures, economic transitions, or multiple historical layers intersect.

This study focuses on the city of Seville, one of the few cities worldwide that hosted two major international exhibitions—the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition and the 1992 Universal Exposition (Expo ’92).

Both events significantly reconfigured the city’s form, infrastructures, and cultural landscape. Yet, while the pre-event transformations have been widely documented, the post-event evolution of these spaces (especially of the 1992 site on Isla de la Cartuja) remains insufficiently theorized, unevenly reported, and rarely evaluated against international experiences of post-expo land reuse.

1.1. Problem Statement and Research Gap

Despite their crucial role in shaping modern Seville, the long-term trajectory of the two exposition sites reveals divergent outcomes.

The 1929 site was successfully integrated into the urban fabric, becoming a consolidated cultural and institutional district.

In contrast, the 1992 site exhibits fragmented redevelopment, a mixture of successful infrastructures and severely degraded public spaces, and unresolved questions regarding its identity and future role within the metropolitan system.

The current academic literature inadequately answers the following questions:

- Why do the two sites evolve so differently?

- How have governance, urban planning, and landscape decisions shaped these divergences?

- What lessons does Seville’s experience offer for future event redevelopment?

Therefore, a certain research gap exists in the post-expo evaluation frameworks applicable to cities with multiple layers of mega-event heritage and incomplete long-term integration strategies. Specific literature references will be detailed in the next section.

1.2. Research Objectives

This study aims to examine how the two exposition sites of Seville have been transformed over time, to identify the factors influencing their divergent legacies, and to propose a design-led intervention addressing current deficiencies in the 1992 site.

The research is guided by three main questions, which emphasize the main objectives:

- How were the 1929 and 1992 exposition sites integrated into the urban and metropolitan development of Seville over time?

- Which spatial, governance, and socio-economic factors contributed to successful or problematic post-expo reuse?

- How can research by design support the sustainable reconversion of degraded areas within former expo sites, and what lessons does the Seville case offer for future mega-event regeneration?

1.3. Contributions and Structure of the Study

This research provides three key contributions:

- Analytical contribution: It offers a comparative examination of the two exposition sites, revealing the processes and obstacles that shaped their long-term urban integration.

- Methodological contribution: It introduces a mixed qualitative approach combining archival analysis, fieldwork, cartographic documentation, and research by design to evaluate post-expo landscapes.

- Applied contribution: It presents an original architectural and landscape proposal for the reconversion of a degraded sector of Isla de la Cartuja, demonstrating a design-based method for reactivating abandoned mega-event infrastructures.

The article respects these key contributions, providing adequate structure, according to all objectives and questions detailed in Section 1.1 and Section 1.2.

2. Literature Overview

This section presents the basis of the methodology and case study framework.

Universal Expositions are one of the most influential categories of mega-events, generating profound yet ambivalent urban transformations as well as a major social impact. Over the past few decades, an extensive body of scholarship has examined these events as instruments of state representation, urban restructuring, territorial marketing, and spatial experimentation. Research consistently highlights the complex political, economic, and cultural geographies that emerge before, during, and after such events, particularly concerning their long-term urban legacies.

2.1. Mega-Events and Urban Transformation

Early foundational works on mega-events [2] conceptualized expositions and Olympics as tools for accelerated modernization, often used by cities to justify large-scale infrastructure, new mobility systems, and spatial reconfiguration. More recent studies deepen the discussion by highlighting processes of uneven development, socio-spatial fragmentation, and contested governance [5], arguing that mega-events often reproduce existing political inequalities or create new forms of spatial polarization.

Universal Expos, in particular, have been interpreted as urban laboratories, generating architectural innovation, pioneering public spaces, and new forms of environmental design [4]. However, scholars have also emphasized the risks of post-event decline, including abandoned pavilions, degraded landscapes, or speculative land practices that fail to integrate into the everyday life of the city.

The Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) is the intergovernmental entity in charge of organizing and regulating all major World Expositions since 1931 [6]. BIE is particularly concerned with the future of all cities, in general. Cities are increasingly confident in sustainable urban development, and, in this way, nowadays, exhibitions are becoming an important tool for sharing these practices and stimulating global discussions on solutions corresponding to such ends. In this sense, when cities decide to host an exhibition, this intervention will not be made in a vacant land, but, on the contrary, the exhibition will be integrated into the development plan of the city and will most often subsequently direct the desired transformation.

Although exhibitions are usually related to short-term, transient events, they can have, if they are thought out from the very beginning, a concrete and lasting character. Exhibitions have always played an important role in urban planning as strategic instruments for urban, economic, and cultural revitalization [5,6,7,8]. Despite their short physical duration, 3 to 6 months, the exhibitions are part of projects with a long-term impact on the transformations they bring to the city. The positive and long-lasting impact of an exhibition depends on its ability to successfully integrate into the city and be part of much broader objectives [9,10].

Over time, the principles and themes of the exhibitions have changed.

Between 1851 and 1940, the exhibitions were strongly influenced by the idea of material progress and technological inventions. The themes were generally based on the passion for building the future and the importance of national identity, for example “A Century of Progress (Chicago, 1933)”, “Art and Technology in Modern Life (Paris, 1937)”, etc.

During the period between 1958 and 2000, expositions were characterized by the need to put technological innovation to the service of the prosperity of humanity. The interest changes from a unitary, monolithic identity to relationships, emphasizing the interconnection of people, technology, research, and nature. The change in perspective is also reflected in the new themes addressed, namely the following: “Towards a more humane world (Brussels, 1958)”, “Man and his world (Montreal, 1967)”, “Progress and harmony for humanity, (Osaka, 1970)”, “The age of discoveries (Sevilla, 1992)”, and “Humankind—Nature—Technology, (Hannover, 2000)”.

The new century is characterized by interdependence. Exhibitions reflect the awareness that every action has long-term consequences for the environment and our lives. There is also a new conviction that exhibitions can once again be true instruments of progress in all areas that present sustainability problems of the global way of life [6]: environment, energy, health, education, etc. Although the focal points of exhibitions have changed over time, a very important concept remains permanent, namely progress, which for the BIE represents the innovation and continuity of exhibitions, while each exhibition is a step towards the future and a catalyst for development [6,8]. For example, the themes of these exhibitions are as follows [6]: “Nature’s Wisdom”, Expo Shanghai 2010 “Better City, Better Life”, Expo 2015 Milan “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life”, Expo Dubai 2020 “Connecting Minds, Creating the Future”, Expo Osaka 2025 “Designing Future Society for Our Lives”, etc.

2.2. Post-Event Land Reuse and Legacy Challenges

The legacy of mega-events has become a central topic in urban studies, with increasing attention to the post-event reuse of exhibition grounds. Research indicates that successful post-event integration depends on the following:

- Long-term planning frameworks established before the event [7];

- Coherent governance structures capable of managing transition periods [5];

- Flexible architectural typologies designed for future adaptation;

- Alignment with regional development agendas and socio-economic dynamics [2].

Comparative studies of past expositions (Montreal 1967, Vancouver 1986, Lisbon 1998, Zaragoza 2008) illustrate divergent outcomes. While some sites were integrated into metropolitan systems as cultural or technological hubs, others experienced prolonged abandonment and failed redevelopment. This variability underscores the need for evaluation frameworks tailored to the specific governance, economic, and geographical contexts of each host city.

The International Bureau of Exhibitions (BIE) attaches great importance to the integration of the exhibition complex into the city, and also to the need for successful management of the plan to allow its reuse [6]. These concerns are regulated by the 1994 Norms of the General Assembly on the conditions for the implementation and reuse of an exhibition complex. Namely, to ensure the contribution that exhibitions should have to the development and improvement of the quality of life of the city concerned, great attention should be paid to the following [6]:

- The environmental conditions of the insertion of the complex and the access infrastructures, reduction in contamination risks, conservation, the establishment of green spaces, and the quality of urban development.

- The reuse of the complex and the infrastructure after the end of the exhibition.

The overall design of an exhibition begins with its architectural landmarks, such as palaces, towers, exhibition halls, and singular monuments. Later, exhibition ensembles are born, which are ample spaces containing different attractions, most often isolated from urban areas, after which a third dimension characteristic of exhibitions is reached, that of urban regeneration, whereby the transient program of the event becomes a sustainable part of the city [9,10,11].

2.3. The Context of Sevilla’s Expositions

Spain has a particularly rich tradition of international exhibitions, shaping its modern identity and urban development from the late 19th to the early 21st century. Recent historiographical analyses (Camerin & Fernández Maroto, 2025) [12] show that Spanish expositions have often served as instruments of national modernization, aiming to reposition cities like Barcelona and Seville within global cultural and economic networks.

Within this Spanish trajectory, the Andalusian context is distinctive. The 1929 Ibero-American Exposition constructed symbolic bridges with Spanish-speaking countries and promoted regional identity through architectural eclecticism. The 1992 exposition, aligned with Spain’s integration into the European Union, sought to redefine Andalusia as a technological and innovative region, a shift documented in works by Vázquez-Barquero and Carrillo (2004) [13], who analyze the creation of the Cartuja 93 Technology Park.

However, despite these ambitions, research also points to structural governance tensions, fragmented land-use decisions, and maintenance deficits that challenge long-term integration, issues clearly visible in the case of Seville’s 1992 site.

In architecture and urbanism, research by design has become an established methodological paradigm, enabling researchers to formulate knowledge through the design process itself. This approach is particularly relevant in complex post-industrial and post-event contexts, where spatial diagnosis, scenario building, and prototyping converge [14]. When applied to expo sites, research by design allows us to explore adaptive reuse strategies; to test environmental and landscape approaches; to propose integrated solutions based on spatial analysis; and to bridge the gap between theoretical evaluation and practical intervention.

Although the literature documents the history of expositions and their pre-event transformations, fewer studies systematically analyze the post-event evolution of expo sites, especially in cases where multiple expositions occurred in the same city. For Seville, existing research focuses either on the architectural achievements of 1929, the planning processes of 1992, or the technological aspirations of Cartuja 93.

What remains insufficiently explored is the comparative long-term trajectory of both expo sites, the reasons behind their divergent outcomes, and the potential of design-led methodologies to address current spatial deficiencies.

This gap positions the present study within an emerging field of inquiry that bridges mega-event legacy research, urban regeneration theory, and spatial design practice.

At this point, exhibitions have become much more complex, and there are difficulties in aligning the initial visions of the event ensembles with the future, more or less predictable ones.

3. Materials and Methods

A Universal Exposition can be designed as a fully coherent whole, from large-scale infrastructure down to the smallest landscape details.

Like other major-attraction events, such as the Olympic Games or more recently the European Capitals of Culture, exhibitions fall into the category of “urban opportunities”. Once chosen as an exhibition venue, the city can take advantage and design the necessary infrastructure, and attract major private investments, which, without this opportunity, would have had much less chance of being realized in such a short time. The recent trend is to assign great importance to public space, which has become the most effective protagonist. Public space is the element that can favor subsequent transformations.

Our research adopts a multidisciplinary scientific methodology that integrates historical analysis, spatial investigation, and research by design. This specific approach was developed in response to the complexity of post-expo issues, which require the combined examination of archival records, forms, governance documents, and current urban conditions. The methodology was designed to address the three research questions presented in the Introduction.

3.1. Research Design and Case Study Justification

As we mentioned, the municipality of Seville (Spain) hosted two exhibitions that have had a major influence on the development of the city [9,10]. The first one was the Ibero-American Exhibition (130 ha), located in the south of the historic area, which took place in 1929. The Great Ibero-American Exhibition allowed the sudden development of the city towards the South; the exhibition pavilions are currently part of the buildings that serve the city—they are either the headquarters of the embassies of the countries once represented or various centers belonging to the faculties—libraries, exhibition halls, etc. The second exhibition was EXPO’92 (250 ha), located in the North, North-West of the historic area, the Great Universal Exhibition of Seville—EXPO’92 took place in 1992, greatly impacting the city.

In the following part, the role of these two exhibitions in Seville will be detailed, including whether their influence was negative or positive and to what extent they managed to be later integrated into the city. Their legacies continue to shape the city’s spatial, cultural, and economic development. The case study method was selected because

- Both expo sites remain physically identifiable and contain substantial built heritage.

- Their post-event trajectories differ clearly, allowing comparative analysis.

- The 1992 site is currently undergoing debates on future redevelopment.

- Authors have direct access to local planning documents and on-site conditions.

This justifies a case study approach aimed at generating transferable insights for broader mega-event legacy research.

3.2. Data Sources Used for Research

Our actual research is based on four main data sources:

- Archive-based documentary sources

- Copies of historical maps, site plans, urban studies, and photographic materials from personal and public archives;

- Some specific publications from the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE);

- Urban planning documents associated with Expo 1929, Expo 1992, and Cartuja 93;

- The academic literature on Spanish exhibitions and Andalusian territorial planning.

- Spatial and cartographic analysis

- GIS-based mapping of land-use changes (1929–2024);

- Morphological analysis of urban blocks, public spaces, and pavilions;

- Delineation of redevelopment zones (technological park, cultural zone, abandoned areas).

- Field observation and photographic survey

- Multiple on-site visits (2007–2024) to document the present conditions;

- Photographic evidence of abandoned structures, degraded landscapes, and recent redevelopment;

- Direct observation of pedestrian flows, accessibility patterns, and functional continuity.

- Research-by-design material

- Conceptual sketches, spatial scenarios, and design prototypes;

- Climatic, shading, and landscape integration studies;

- Iterative architectural modelling was used to develop the proposed intervention.

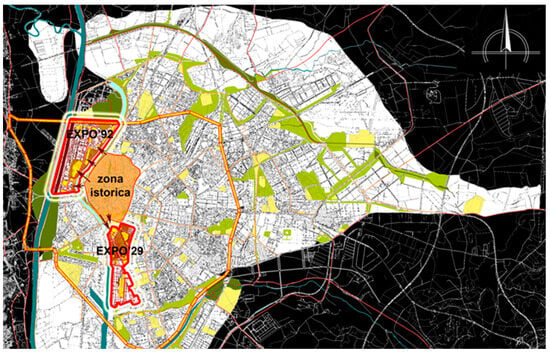

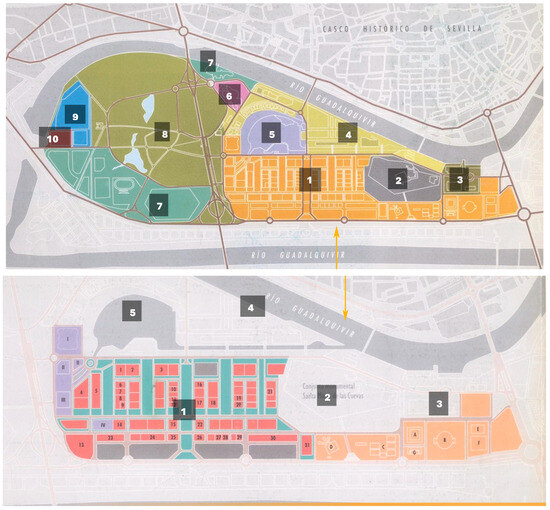

Figure 1 depicts the actual locations of the two expositions on the city map.

Figure 1.

Location of the two city expositions on the Seville map, connected by the historical center of the city.

3.3. Seville and Its Metropolitan Area

Seville is the fourth-largest city in Spain by population (684,234 inhabitants in 2021).

It is located at an altitude of 20 m above sea level, in the middle of a low plain area, crossed by the Guadalquivir River.

It is one of the major commercial and artistic centers in southern Spain and one of the cities with the strongest personality. Seville is a city of significant tourist importance, preserving the largest historical and artistic urban center in Europe. The Giralda, the Cathedral, the Alcázar, the Archive of the Indies, and its surroundings were declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1987.

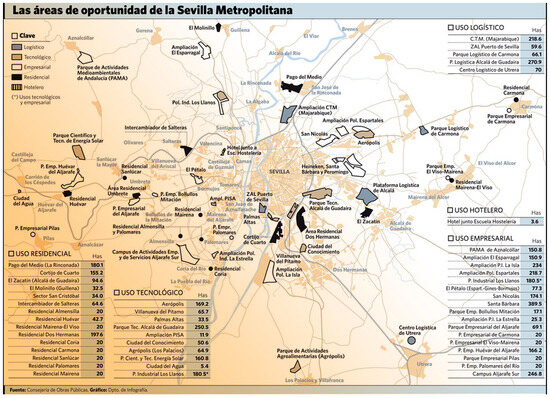

This area is composed of 46 municipalities very closely linked to the capital (Seville), covering around 140 km2. Most of these municipalities are dormitory cities, and the others help the city in commercial aspects, services, facilities, relaxation, rest, and entertainment. The development of this metropolitan area began between the 70s and 80s, but the great urban apogee occurred in the 90s and continues to this day when this metropolitan area continuously grows through villages and extensions [10], as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

General plan of Seville, metropolitan area, divided into 5 areas: logistic (light blue), technological (brown color), business (white), residential (black), and hotel (brown with stripes).

The 20th century in Seville began with the dream of an exposition, which finally took place in 1929. The Ibero-American Exposition left behind the Plaza de España, the Plaza de America, and the pavilions of the main participating countries, which presented different styles that evoked the indigenous pre-Columbian cultures. The century ended with Expo 92, which commemorated the 5th Centenary of the Discovery of America and which, from an urban point of view, meant not only the incorporation of Cartuja Island but also the elimination of the two train stations that represented a great obstacle to the internal communication of the city, the construction of the Santa Justa Station, the high-speed train, the ring roads, etc.

3.4. The Ibero-American Exposition

The Ibero-American Exposition was opened on 9 May 1929 and lasted until 21 June 1930. The countries participating in the exhibition were the following: Portugal, Brazil, the United States, Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Colombia, Chile, Cuba, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Bolivia, Panama, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Ecuador. Every Spanish region and every province of Andalusia were also represented [9].

The exposition aimed to improve relations between Spain and the participating countries, many of which were former Spanish colonies.

The exposition was a replica of the one held in Barcelona the same year. The city of Seville prepared for the exhibition for over 19 years. The exhibition buildings were built in Maria Luisa Park along the Guadalquivir River. Most of the buildings were designed to remain permanently after the exposition closed. Many of the foreign buildings, including the United States pavilion, were originally intended to serve as consulates of the countries represented. By the time the exposition opened, all the pavilions were finished, and some were no longer new. Not long before the opening of the exposition, the Spanish government also began a modernization of the city in order to prepare it for the large number of participants and visitors. Namely, they built a lot of new hotels and widened the medieval streets to allow for automobile traffic, etc.

- Spanish Pavilions and Exhibits:

Spain invested large sums of money in developing its exhibits, which it presented in elaborate constructions. The exhibits were designed to display Spain’s social and economic progress, as well as to express its culture. Spanish architect Anibal Gonzalez designed the largest and most famous building of the exposition, which surrounds the Plaza de Espana. This building housed one of the largest exhibitions, the “Salon of the Discovery of America”, which included maps, letters, and other documents related to the discovery of America, including those of Christopher Columbus.

- United States of America Pavilions:

The U.S. contributed three pavilions to the exhibition, the main one of which presented a multitude of household appliances and was later intended for the consulate, and the other two buildings were intended for a cinema theater and government exhibitions.

- Latin American Pavilions:

A total of 10 of the participating countries had individual pavilions (Peru—the largest, Colombia, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Venezuela), and others such as Bolivia, Panama, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Ecuador presented their products in the “American Commercial Gallery”.

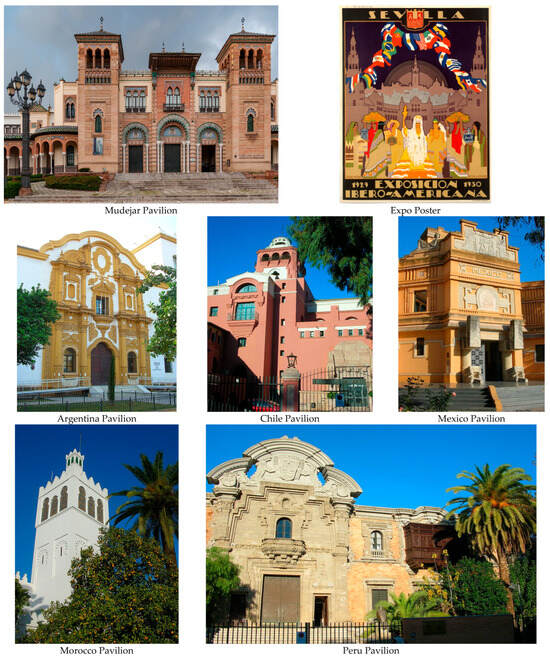

Today, many of the exhibition pavilions remain standing, such as the famous Plaza de Espana (Figure 3—our archive), as well as the national pavilions converted into consulates general (Figure 4). Many of the buildings are now museums or schools, such as the Flamenco dance school in the former Argentine pavilion. Due to the architecture and characteristics of each country once represented, this setting has been used in many films.

Figure 3.

Plaza de España from Seville, today.

Figure 4.

Different images of Expo 29 pavilions (from our archive).

Although predictions made prior to 1929 suggested that this exhibition would be a total waste and very unprofitable, despite the relatively low number of visitors (800,000) due to the world crisis of 1929, the city benefited enormously from this event. Namely, a factor of modernization finally intervened in a much too traditional city. The standard of living was raised through major infrastructure projects and equipment necessary for the city, and, last but not least, the most important consequence was the new direction of urban development of the city towards the south, an area that had been completely abandoned until then.

3.5. The 1992 Exposition

Seville92 represents a unique example in the history of exhibitions. First of all, it must be placed in the Spanish context of the 1980s. The main objective and pretext was the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus. Because this name was very questionable, the Spanish government redefined the theme of the exhibition as “Age of Discoveries”. The focus of the EXPO’92 Exhibition was on presenting the new frontiers of science and technology, opening the way to a much more innovative project [15].

The city of Seville, with approximately 700,000 inhabitants at the time, began planning the most ambitious urban development operation in its history. The project aimed to present to the world an image of a modern country, of technological progress, but also a project of regional rebalancing in favor of a southern region, traditionally not industrialized like Andalusia, focusing on projects of modernization of its administrative capital (Seville), through a strong territorial dynamism of the metropolitan space and betting on this opportunity of regional articulation and north–south balance in Spain, in the shadow of European policies oriented to this end [16].

The Cartuja Island—“Isla de la Cartuja”—is located very close to the historic center, on the right bank of the Guadalquivir River, an ideal strategic place for the location of the exhibition area. To create the Universal Exhibition, 250 hectares of agricultural land was used where the historic Cartuja Monastery is located, from which Christopher Columbus prepared his journey to America and where he was buried for 30 years. The monastery was in an advanced stage of degradation, and total rehabilitation was necessary to recover its former splendor and to become one of the symbols of the 1992 Exhibition. The transformation of this land known as “Isla de la Cartuja”, the Cartuja Island, is considered one of the most important public works of the last century in Spain. Figure 5a presents the island before the intervention, and Figure 5b presents the situation during/after the intervention.

Figure 5.

Isla de la Cartuja before (a) and after (b) the intervention.

The exhibition was, in fact, a means to revitalize a city, a historically depressed region. As Perez Escolano said [10], the need to address these unprecedented urban and territorial transformations had, alongside the actual proposal of the exhibition ‘92, the simultaneous support of a General Urban Organization Plan, whose objectives were fully achieved.

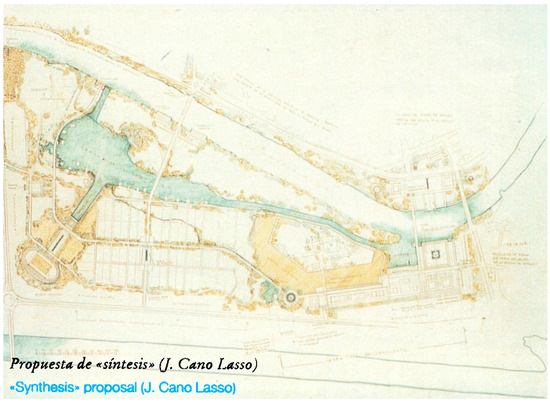

In organizing the exhibition, there was a shift from an ambitious vision of arranging the exhibition spaces along the riverbank to more pragmatic visions in which the buildings were concentrated in a single enclosure [17]. With these premises, the competition of ideas for the Management Project of the complex began in 1986. Of the 20 teams that presented themselves, the jury gave two prizes to the architects Jose Antonio Fernandez Ordonez and Emilio Ambasz.

Ordonez proposed a complex of pavilions arranged in an orthogonal grid, with a linear park on the banks of the Guadalquivir River and a giant sphere (100 m in diameter) as the planetary symbol of the exhibition.

Ambasz’s conception was much more landscape-oriented, making particular use of the importance of watercourses.

Despite the great differences, both urban-landscape concepts had certain common features, in particular, the weak connection with the riverbank. The final project was developed by Julio Cano Lasso (1987) [13], a hybrid between the two solutions, with a rather conventional air regarding its autonomy from the riverbank and the historic city, as seen in Figure 6. But, despite this relationship with the riverbank, a connection was created between the city and the exhibition, through new pedestrian streets, promenades, and bridges over the river. Also, a new road network was created, the railway network was strengthened, and the very fast train AVE was introduced.

Figure 6.

Final proposal of J. Cano Lasso.

The Expo’92 Universal Exhibition brought many changes to Seville from an urban point of view. Over 70 km of new stations was built, along with a train station, and the high-speed train, AVE, now connects Seville with Madrid in less than 3 h. The Guadalquivir River was restored to its original state, and the following bridges were built: Puente del V Centenario, Pasarela de la Cartuja, Puente de las Delicias, Puente de Chapina, Puente de la Barqueta, and Puente del Alamillo. Other buildings built for Expo’92 are the Maestranza Theater, in front of the bullring of the same name; the Cartuja Auditorium; and the Congress Palace, which boasts a huge golden dome. In addition, the Old Cordoba Train Station was transformed into an exhibition hall.

The exhibition was open to the public for 176 days, during which it was visited by 42 million people (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11).

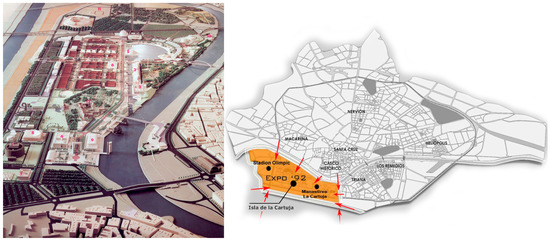

Figure 7.

Layout and location of the Expo 92 site.

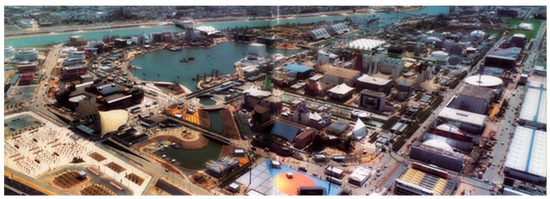

Figure 8.

Aerial view of the Expo 92 site.

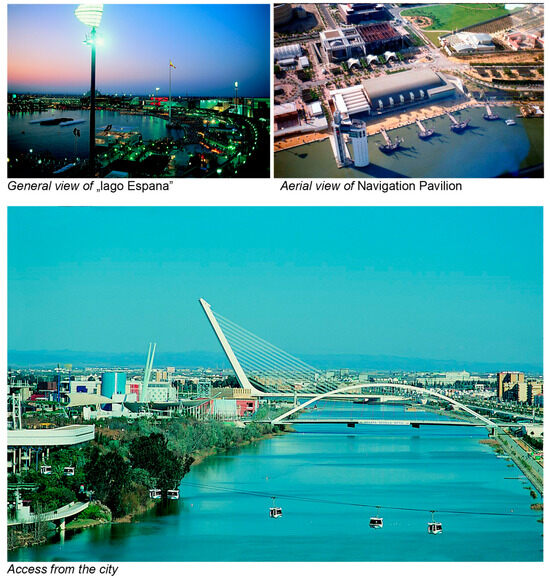

Figure 9.

Different views of the Expo’92 site at that time.

Figure 10.

Avenida 3—bioclimatic sphere.

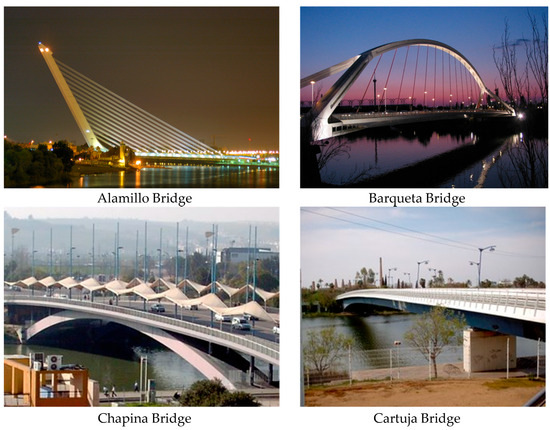

Figure 11.

The most important bridges related to Expo’92.

During the 176 days that this exhibition lasted, there were numerous concerts and shows. The attraction of the night was the Lake Show, where various shows were projected on the sprayed water and mixed with light, sound, laser, and fireworks.

In the landscape design, numerous elements were extremely important in order to create a city with vegetation in two years. On the one hand, a master plan of the ensemble was organized by a team of landscape architects, and on the other hand, projects were made by landscape architects to coordinate the free spaces around the buildings with the built space to create unity.

The execution in a record period of two years, the use of 25,000 plant species, the introduction of new species in 20th-century Europe, the development of the green ring, and the design of planted public spaces converted this project into a reference for future exhibitions and also had an influence on the design of new cities and urbanizations.

A nursery was created within the exhibition for training and growth until the moment of transplantation of the species necessary for the exhibition, and it also functioned as a place where exotic plants, such as species brought from Latin America, could be purchased.

3.6. The American Garden Within Isla De La Cartuja

The most important landscape projects within the exhibition, some of which are still current, would be Guadalquivir Park–Garden, Cartuja Garden, American Garden, Defense Wall and plantation in galleries, Boulevard 1,2,4,5, “Avenida 1,2,4,5”, World Trade Center (the building is built around an interior courtyard of vegetation), Lakeside and the Plant Pergolas Project.

During the exhibition, vegetation had an unexpected success among visitors. The vegetal pergola projects, the projects of the 5 boulevards, and the American greenhouse competed with the most famous singular architectural objects of the expo.

As we mentioned before, the 1992 site covers over 250 hectares; therefore, an analysis requires some prioritization. This almost abandoned area, formerly known as the American Garden (having around 1.7 ha), was studied by our team, due to the following reasons:

- Its historical and landscape importance within Expo ’92;

- Its current advanced state of abandonment and the degradation of the landscape, buildings, details, and ornamentation, analyzed using photography and photogrammetry if necessary [14];

- Its almost strategic position near other cultural and landscape objectives (monastery, auditorium, Guadalquivir riverfront);

- The existence of a certain remaining infrastructure suitable for adaptive reuse;

- Its potential to reconnect fragmented sections of the island through public space.

These criteria align with established methods in landscape urbanism, cultural heritage adaptation, and ecological regeneration.

After this event, green spaces became important protagonists alongside architecture and urban planning.

We will also discuss the research methodology involved in this study.

3.7. Analytical Research Framework

We have to analyze the research methodologies involved in this study.

To evaluate the post-event evolution of the expo sites located in Seville, Spain, especially the Cartuja Island, our current article employs a three-stage analytical framework:

- Historical Urban Reconstruction: It involves understanding how both expositions were planned, built, and integrated into Seville’s urban development before the event.

- Post-Event Spatial Evaluation: This framework involves assessing long-term land-use transitions, levels of functional occupancy, preservation of public space quality, infrastructural resilience, and the degree of urban integration. Also, it involves evaluating transformation patterns across multiple dimensions: physical (architecture, public spaces, infrastructures), functional (economic activities, cultural/social roles, accessibility), and governance (ownership fragmentation, planning instruments, investment cycles).

- Design-Led Problem Solving (Research by Design):This method is about

- Using design-related tools as a method to test potential regeneration solutions;

- Applying environmental, structural, and architectural criteria to evaluate feasibility;

- Positioning the proposed project as an analytical tool answering the research questions.

3.7.1. Research by Design: Role and Justification

The authors’ involvement in producing an architectural and landscape proposal for the site is acknowledged explicitly as part of the methodology. In many architectural studies, design serves both as an analytical tool, enabling the interpretation of existing spatial conditions, and as a projective tool, allowing the development of solutions based on empirical analysis.

The proposed multifunctional botanical complex is therefore not only a design outcome but also a methodological instrument that operationalizes the findings of the historical, spatial, and governance analyses.

3.7.2. Limitations of the Methodology Involved

This study is qualitative, simple, and exploratory in nature. It does not include extensive survey-based social data, long-term economic modeling, or quantitative environmental simulations beyond preliminary design considerations.

However, the results of archival research, spatial analysis, and design exploration provide a robust foundation for evaluating the long-term evolution of former expo sites.

4. Results

The results of this research summarize the combined analysis of historical documentation, literature reviews, spatial evaluation, field trip observations, and design-oriented investigation. This section synthesizes these main findings regarding (1) the post-event evolution of the 1929 exposition site, (2) the transformation and challenges of the 1992 site, and (3) the spatial diagnosis that led to the design proposal for the American Garden/Jardín Americano area (a project made by one member of the team). The case of the 1992 Seville Expo is relevant in terms of post-expo land use, both for thinking and planning in the early stages of the exhibition design and for the outcome in the years that followed. Some of the previous examples (Montreal 1967, Tsukuba 1985, or Vancouver 1986) suffered from the slow process of urban integration of the former exhibition grounds [18].

4.1. Post-Event Evolution of the 1929 Exposition Site

One of the most important facts about Expo 1929 and its planning was the location with its successful integration into Seville’s urban fabric. The high level of integration was achieved due to several factors:

- Strategic location within the existing urban structure of Seville, close to the historical area and consolidated neighborhoods, adjacent to main mobility axes, and easy accessibility.

- Architectural permanence of the buildings, because most of the pavilions were strategically designed as durable constructions intended for institutional reuse after the exposition was over.

- A clear and transparent governance model, with the assumption of ownership and management of the site/buildings after the closure of the event by municipality and regional entities.

- Close links to major cultural anchors/tourist attractions because of the proximity to Maria Luzia Park and Plaza de Espana, offering continuous use and integration in promenade relaxation routes.

By the mid-20th century, the location developed into a cohesive cultural and administrative district. Former pavilions were gradually occupied by diverse academic institutions, museums, and other public institutions while maintaining their former architectural identity, style, and appearance.

Field observation and documentation from multiple sources revealed a functional diversification of uses like cultural (museums, exhibition spaces), academic (university offices and departments), administrative (government institutions), and recreational (gardens and parks). Good maintenance and permanent public investments explain the good conservation of the entire area and the buildings which once belonged to the former site of Expo 1929, a subject that will be later compared to the situation of the 1992 Expo site.

4.2. Post-Event Evolution of the 1992 Exposition Site (Isla De La Cartuja), Urban Planning

Contrasting the situation from 1929, the 1992 Expo site suffered from a more fragmented and uneven trajectory. What is very interesting for Seville is that, despite the criticisms made, due to the lack of a post-expo project, it is easy to demonstrate that the reality was completely different: it was not the absence of a project but the coexistence of visions and conflicts of interest for the reuse of the land that posed great difficulties in respecting the initial plans. In 1989, the Andalusian Department, through the Andalusian Promotion Institute (IFA), hired a team of specialists (members of the universities of Seville, Málaga, Madrid, and the EXPO’92 State Company) to carry out the Investigation Project on New Technologies in Andalusia (PINTA) under the direction of Manuel Castells and Peter Hall. The EXPO’92 State Company adopted an innovative strategy, establishing one of the basic objectives of the future of the exhibition in 1993, the optimization of an advanced infrastructure of the complex for a future “attractive location for the establishment of research centers, scientific centers, and innovative high-tech companies”. For this reason, the criteria for immediate economic profitability were left aside, and the focus was shifted to the future—towards activities encompassed under the concept of a “Science and Technology Park”. But, in addition to the economic and political conflict of interest shortly before the exhibition’s inauguration, the economic situation after 1992 stimulated the reconversion of the initial idea towards a state-of-the-art business park rather than a technological one [19,20]. As mentioned before, fragmented governance and land-use patterns were among the main reasons the post-expo 1992 site struggled to achieve a coherent and continuous urban integration. On site, maps and document analysis reveal at least ten different land management arrangements in operation on the site after 1992, including municipal authorities, regional governments, different private companies, and also educational institutions. This fragmentation inevitably produced discontinuous redevelopment, inconsistent maintenance, and spatial segregation between the functional areas. With the establishment of the Cartuja 93 Technology Park, a large area of the island was reactivated, but yet, this process left other areas underused or abandoned for several years.

So, after the end of the Expo, Cartuja Island was divided into several areas, each with different specifics and a different owner (according to Figure 12), namely as follows [21]:

Figure 12.

Cartuja’93 island with the division of the 10 areas in the first image and a detailed view of the Scientific and Technological Park (STP)—areas of use—in the second image.

- Seville Tecnopolis—Cartuja’93 Scientific and Technological Park (STP), which reuses much of the infrastructure of Expo’92 (the “Puerta Triana” project—the first office skyscraper in Seville was developed in this area);

- Monumental Ensemble “Santa Maria de las Cuevas”;

- Cultural Area;

- Entertainment, Relaxation and Culture Area;

- Entertainment and Relaxation Area (theme park “Isla Magica”);

- Hotel;

- Sports Facilities;

- Alamillo Metropolitan Park;

- University Park;

- Spanish Radio Television.

Since it began operating, Cartuja’93 has become one of the most developed Scientific and Technological Parks in Europe, with 567 company headquarters (including many innovative start-ups), technological, research, university, and training centers. Cartuja’93 Technology Park has more than 15,000 employees and an economic gain of EUR 2.194 million annually. The area of Cartuja’93 is presented in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Seville Tecnópolis—Cartuja’93 Scientific and Technological Park integration into the city.

Based on site and cartographic analysis, to sum up the transformation of the most important functional areas, we highlighted these specialized sectors:

- Technological and Scientific Park (high occupancy, stable economic activity);

- Cultural and Leisure Zone (Auditorio Rocío Jurado, theme park and other events facilities);

- Institutional and Educational Zone (satellite university facilities);

- Abandoned Pavilion Zone (isolated structures, unused platforms, degraded open spaces);

- Riverfront Areas with partial revitalization but inconsistent accessibility.

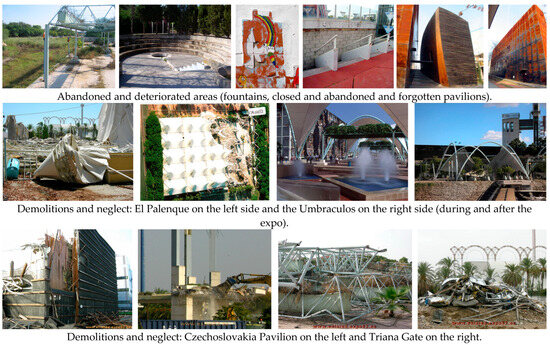

The area of the Technological and Scientific Park exhibits both commendable and unfavorable attributes. Certain sectors, currently unoccupied by enterprises, are entirely neglected and exhibit significant deterioration, as depicted in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Demolitions and neglect of Expo’92 structures.

Public space degradation is highly visible in the images above. Photographic and on-site evidence show widespread issues in at least three categories:

- Material degradation (broken pavements, vandalized elements);

- Landscape degradation (vegetation loss, dry gardens, erosion);

- Infrastructural obsolescence (inoperative technical systems, disconnected pedestrian routes).

This degradation contrasts sharply with the 1929 site, where continued institutional presence ensured maintenance and adaptive reuse.

Somehow, that compositional unity that the exhibition was so proud of has been lost. Among the pavilions that still have no owner and have been unused for many years would be that of Czechoslovakia (which was destroyed at the end of February 2008) of Austria, which is still standing, and the “Palenque” area—the stage and open-air market—which, due to the high cost of the land, was demolished at the end of 2007 to build new office buildings, as seen in Figure 14 [21].

Some new construction sites have been added to the site, as described in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

New construction sites in the Expo’92 area.

The cable cars and the urban train have been completely lost, and the saddest thing is that the Guadalquivir and American Gardens have been closed to the public for over 10 years due to lack of funds for maintenance. These gardens were, in 2008, when the authors started analyzing the site, in the final stage of destruction; over 60% of the plant species had disappeared, and if beneficial intervention were not made in these plots, everything would have been lost.

The five boulevards that were the strong points of Expo’92 are also suffering, being abandoned.

After the state of abandonment in the public spaces of the old Expo’92 premises, the revitalization of the area and at the same time the regeneration based on culture began with the implementation of functions of major interest for the city (exhibition centers on different themes, museums, shopping centers, office buildings, parks and green spaces, amusement parks, etc.), resulting in the creation of a coherent waterfront.

The revitalization process of the riverfront was a partial success. A set of projects implemented over the past few decades has improved different zones of the Guadalquivir river edge, including facilities such as promenades, new cycling routes, and of course restored landscapes, which were much needed in the area. Although this was a huge step forward, spatial continuity was not yet achieved. Gis analysis still indicates that several segments remain unconnected to nearby urban districts or are inaccessible.

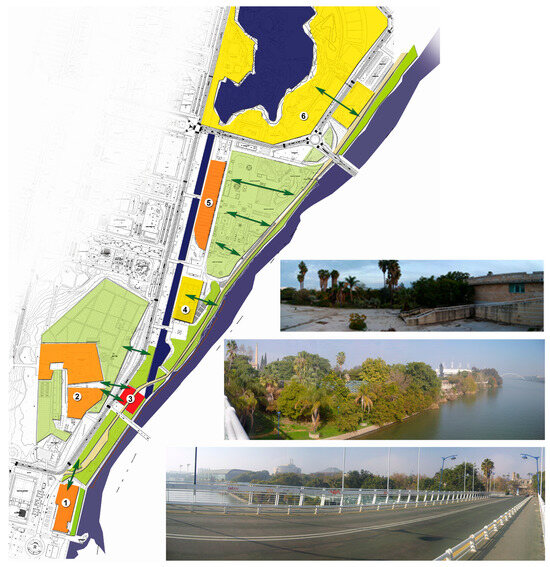

Some projects for Isla de la Cartuja aim to address these special discontinuities. Among them, the “NATURALIA XXI” proposal seeks to restore, recover, and reactivate degraded public spaces to create a scientific–cultural–educational and recreational complex with a strong environmental character.

Naturalia XXI is an open proposal for which funds are being sought. The aim is to create a complex with an environmental character located on the Cartuja Island and its vicinity, targeting the already existing spaces. In general terms, the Naturalia XXI project aims to recover the abandoned spaces of the Expo’92, those that were used inappropriately. This project was born from the desire of the inhabitants of Seville and those in love with the former Universal Exhibition [22].

This master plan aims to save as much as possible the concepts that were the basis of the exhibition and the public areas—the main goal is to introduce nature into the space of the former Expo’92.

The areas targeted by the project are as shown in Figure 16:

Figure 16.

Naturalia XXI project map (the numbers refer to the list provided below in the text).

- American Garden—recovery of plant species;

- Reuse of the Pavilion of the Future as a science center–museum;

- Isla de Tercia Ecological Reserve;

- Bike paths—proposal;

- Alamillo Park—expansion;

- Monastery Orchard—recovery;

- Aquatic Ecology Center;

- San Jeronimo Park;

- Nursery—project;

- Riverbank forest–park–promenade—proposal;

- Meander bank forest–park;

- San Jeronimo Meander.

There are new projects and competitions for several other buildings, like the bioclimatic office building and many others.

The construction of the first skyscraper of Seville, The Seville Tower (Torre Sevilla), known also as the Pelli Tower, is one of the major construction projects of Cartuja Island. It is an office skyscraper that is 180.5 m tall and has 40 floors, designed by the architect C. Pelli. The construction started in March 2008 and was completed in 2015 (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

The Seville Tower and its controversial history.

UNESCO was considering putting Seville’s monuments—which are classified as World Heritage Sites (the Cathedral, Alcazar, and Archivo de Indias)—into the “Threatened List”, because of the tower’s “negative visual impact” on the old town skyline of Seville. UNESCO even asked the municipality to lower the tower’s height, but most of the city officials ignored all these ideas.

4.3. Comparative Findings Between Seville’s Former Expo Sites: 1929 Versus 1992

- Different Pre-Event Strategies: 1929 where long-term institutional reuse was planned in advance versus 1992 with an emphasis on technological innovation and international visibility, with low focus on durable post-event integration.

- Different Spatial Logics: the 1929 site was embedded within the city with strong connection versus the 1992 site which was on an isolated island, requiring new bridges and mobility infrastructure and more complicated integration.

- Governance as a Determined Factor: The continuity of public management in 1929 contrasts with the fragmented governance after 1992.

- Differential Maintenance: Long-term maintenance levels diverged strongly, directly influencing public space quality and functional resilience.

4.4. Diagnosis of the American Garden Area (Jardin Americano), as Basis for the Proposal Described in Section 4.5

For the revitalization proposal developed in Section 4.5, we chose the former American Garden (1.7 ha) and we made a detailed spatial analysis, revealing four critical issues:

- Existing Structural Elements with Significant Potential for Adaptive Reuse: Leftover foundations, walls, and platforms from the original Expo ’92 installation remain structurally sound, offering opportunities for adaptive reuse without complete demolition.

- Severe Landscape Degradation: Field survey indicated 80–90% loss of original vegetation, erosion of soil layers, absence or degradation of irrigation systems, and the presence of invasive species that destroyed the original valuable plants.

- Missing Connections to Adjacent Functions: The site of the gardens is strategically located between strong and important anchors (monastery, auditorium and riverfront) but suffers from physical barriers, lack of signage and visibility, and absence of continuous pedestrian safe routes.

- Lack of Identity and Programmatic Anchor: The area functions as a void within the entire island, lacking a defined public program, ecological structure, and cultural/recreational functions, and has almost no integration into the broader Cartuja strategy.

- The analysis/diagnosis made defines the implications for the design proposal described below in Section 4.5. The regeneration of degraded post-expo landscapes requires the following:

- Reconnecting fragmented public spaces;

- Reactivating abandoned infrastructures through adaptive reuse;

- Integrating ecological principles to restore soil, vegetation, and microclimates;

- Creating new public attractions with cultural and educational functions;

- Strengthening links between the island and the city.

All of these findings directly influenced the author to design the concept and technical development of the proposed botanical garden and multifunctional center.

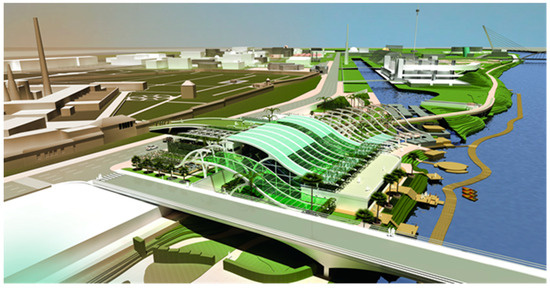

4.5. Multifunctional Center and Botanical Garden, Proposal for a Neglected Area Within the Expo 1992 Site, on the American Garden Plot

The theme of the project was the revitalization of an area within the former EXPO’92 site (215 ha) and the proposal of a function appropriate to the place and the needs of the city. The studied land, as well as the entire exhibition, is in an advanced stage of degradation. The theme of nature had an important role in the exhibition.

Despite this, the site was abandoned and closed to the public for decades. The plants in the parks and gardens have completely dried up. In our attempt to give life to the EXPO again, we chose one of the abandoned plots, the old American Garden (1.7 ha), one of the successful areas of the event, which at that time housed thousands of types of plants brought with great effort from America.

The motivation for choosing the location was simple: First of all, the choice was based on the attempt to revitalize an abandoned and degraded area that causes an unfavorable image for both the area itself and the city. Secondly, due to its key position within the site dedicated to the Universal Exhibition, the site is surrounded by riverfront neighborhoods which play an extremely important role in the city—such as the amusement park, the LA Cartuja Art Museum, the Auditorium, the Guadalquivir Garden, and the future projects of the Science Museum, the Aeronautical Museum, and the Naval Museum. Together with the proposal for a botanical garden on the chosen site, these will be able to form a complete chain of functions—a network and a closed area for public use for rest, entertainment, relaxation, and also information.

Following the analysis of the site and the possible developments, trends, and needs of the area, the main lines of development of the project were the following:

- Context within the metropolitan area and its development;

- City–river relationship as a center of attraction;

- History, art, and integration into the museum circuit;

- Relaxation, rest, fun, and study—moments spent in free time;

- Neighborhood in the natural setting and outdoor spaces;

- Future, sustainable development, and environmental respect.

The project will detail a multifunctional center with botanical garden specificity. The chosen theme is directly related to what is currently found on the site—namely the remains of a former garden with plants brought from Latin America, a simulation of the Amazonian rainforest (the evergreen equatorial forest that covers the entire Amazon basin), which, unfortunately, if the necessary attention is not given to its rescue as soon as possible, will disappear. A former area of fountains and small water basins that once connected the artificial lake and the river now exists only as abandoned infrastructure once the exhibition ended, as we can see from Figure 18, where our project is located in area number 3.

Figure 18.

Project site location and the proposed connection to the riverbanks and between major cultural facilities (1—Navigation Pavilion/Naval Museum, 2—La Cartuja Monastery/Contemporary Arts Museum, 3—authors’ proposal for multifunctional center with botanical garden, 4—auditorium, 5—The Pavilion of the Future/New Museum of Science and Technology, Aeronautical Museum, and 6—Isla Magica Theme Park) versus photos with the actual status of the site.

The project tries to save as much of what is left of the exhibition on this site. The intervention would be as minor as possible; it could be a project designed to be open to the public but with annexes and spaces for rent, which, although not directly related to the specifics of the botanical garden, are necessary for the proper functioning of the ensemble both from the point of view of the whole and from the financial point of view. Through these annexes such as the conference room, classrooms, exhibition rooms, and cafes, the building can function with their support, without depending on continuous financing from public funds [14,15].

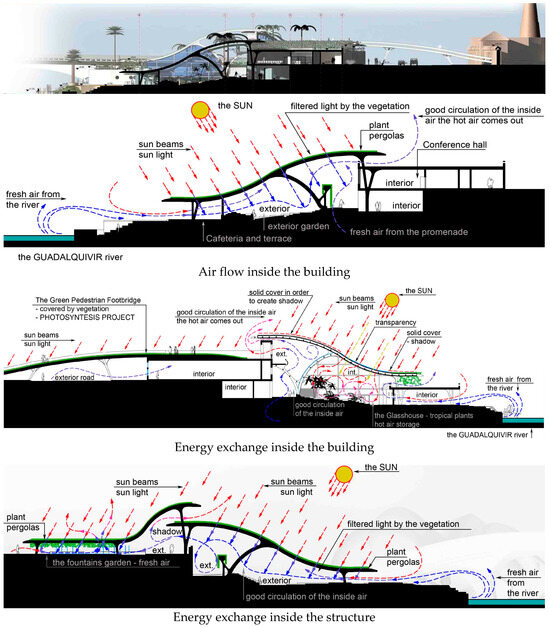

The construction integrates into the natural setting of which it is a part. Being bordered by the riverbed and the land on a slope, its adopted form seems to be born from the water, transforming into a wave that takes advantage of the existing slope, and stopping suddenly where it intersects with the rectangular part of the building, which is covered in vegetation, as observed in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Project overview.

Also, on the opposite side of the monastery, a green pedestrian walkway starts, which counterbalances and adds a sense of balance to the architectural dynamics. This shape is optimal for a botanical garden because palm trees need vast, high spaces. The shape is conducive to good circulation of interior air that can be used for energy purposes, and at the same time, being a predominantly glass building, it can make use of sunlight and heat to support the technical functioning of the building.

Using a skeletal structure of the “rib” type, we tried to integrate architecture with modern construction technologies in the project implementation area. Thus, naturally, vegetation can grow freely, covering the structure. The resulting vegetal pergolas create a pleasant, fresh atmosphere on hot summer days in Seville, as seen in Figure 20.

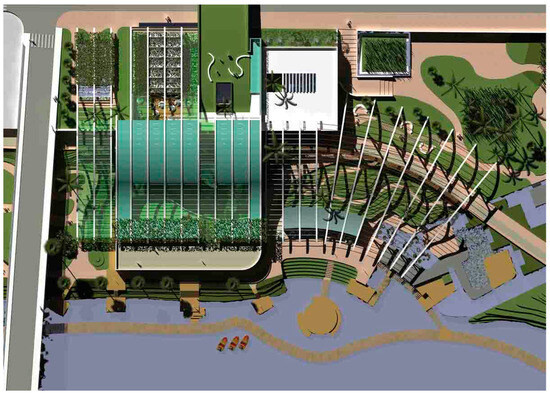

Figure 20.

Top view of the structure.

The new proposed function integrates well with those already existing on the site and in the vicinity, and forms with them a cultural, museum, and leisure network for spending free time. The first phase in approaching this project was to emphasize the existence of an old connection between the functions on the riverbank. Within the site, we proposed an internal network for visiting the botanical garden; namely, the visit will begin at the access area, where visitors descend a ramp that surrounds an internal courtyard in which the Amazon rainforest will be simulated. After that, a route will lead to the area intended for tall plants (palm trees of different types) and diverse flowers and exotic species, after which they will reach the area intended for water plants. Once they arrive there, the route can vary; it can continue, eventually reaching the Guadalquivir Garden, or it can take a 90-degree turn in the direction of the small park or the old area intended for the American Garden. The annex spaces—reading rooms, exhibition halls, conference room, and cafes—are located along this route, interacting with it and making it easily accessible, as described in Figure 21.

Figure 21.

Design and energy efficiency.

Seville’s biggest problem is the strong sun during the summer.

In this sense, the project is divided into five areas treated differently in terms of their relationship with natural light, as seen in Figure 21.

- The outdoor promenade—suitable for outdoor walks, thanks to the pleasant light filtered by the vegetal pergolas.

- The outdoor garden and parks—such as the American Garden with numerous cacti or the aquatic plant garden—are treated differently, with fountains, sprayed water, and filtered light.

- The indoor botanical garden—a glass greenhouse for plants that need high, constant temperatures.

- Simulating an Amazon rainforest—a space where it rains very often, which does not need direct light, protected by tensioned translucent canvases, specially designed for reliable use.

- Interior spaces—such as classrooms, exhibition spaces, cafes, conference rooms, and shops—positioned near spaces with good air circulation, refreshing the indoor atmosphere.

The main concept of the project is photosynthesis and sustainability.

As plants need sunlight to grow, people also need plants to live. Not only do plants produce oxygen through the process of photosynthesis, but they completely transform the environment, visually and aesthetically.

We need plants to live in a simple relation: light–plants–people–life.

Light is the most important aspect of our lives. The goal of our project was to use sunlight differently, to create different areas depending on the need. By studying the importance of sunlight, we designed sustainable architecture that takes into account the needs of the users.

In any case, the expo undoubtedly had a major impact on the urban structure of Seville. The accumulation of investments produced in only a few years led to spectacular transformations.

5. Discussions

The comparative analysis of Seville’s two Universal Exposition sites reveals significant differences in post-event trajectories that align with and also add nuance to contemporary theoretical discussions on mega-event legacies. This section situates the findings within established research, discusses the structural determinants of success or failure in post-expo integration, and positions the proposed design intervention within international debates on adaptive reuse and ecological regeneration.

Because, after the end of the exhibition, the area was subdivided in 1993, control over what was originally intended to be a whole was lost. What worked, and still works very well (with large expansion plans, doubling in 5 years), is the technology park, but the area seems and is silent and lifeless.

Of course, the area attracts a very large number of people daily, thanks to the companies that work in these offices, but there is no unity. These people do not relate to the site or each other because there are no attractive public areas. We are not suggesting that public areas do not exist; on the contrary, they could function if restored.

5.1. Interpreting Seville’s Divergent Post-Expo Trajectories

Up to now, there have been no major investments in revitalizing these main public areas. We will try to establish the main causes of this status.

5.1.1. Governance Structure as a Key Determinant

The results demonstrate that governance fragmentation was the principal factor explaining the long-term difficulties of Isla de la Cartuja. This finding corroborates the arguments of Minner [5], who highlights that post-event management models strongly influence whether former mega-event sites evolve into vibrant urban districts or into socially and physically fragmented landscapes.

By contrast, the 1929 site benefited from unified ownership, consistent political stewardship, continuous public investment, and stable institutional occupation.

This supports theoretical models arguing that strong post-event governance correlates with functional resilience and spatial consolidation [7].

5.1.2. Pre-Event Planning and Designed Permanence

The results confirm one of the core principles in the mega-event literature: the extent to which exhibition structures are designed for permanence influences post-event performance.

The 1929 exposition was planned with the explicit intention of establishing durable buildings for cultural and governmental functions. Conversely, the 1992 exposition prioritized technological spectacle and temporary installations, consistent with global trends in late-20th-century mega-event urban planning.

The findings support previous comparative research (e.g., Montreal 1967; Vancouver 1986; Lisbon 1998) showing that sites without a predetermined long-term program tend to experience extended periods of abandonment.

5.2. Spatial Configuration and Urban Connectivity

The analysis confirms the theoretical assertion that isolation undermines post-event integration. The 1929 site was embedded in the existing city structure; the 1992 site required bridges, highways, and new infrastructures to connect it to the city.

Despite improvements, Isla de la Cartuja remains perceived as a spatial enclave. This aligns with the literature suggesting that mega-event sites located on reclaimed or peripheral land frequently become urban islands, struggling to achieve everyday integration (Zhou et al., 2024 [11]).

5.3. Maintenance, Identity, and Long-Term Urban Life

A critical insight emerging from this study is the central role of ongoing maintenance and place identity. The 1929 site developed a strong, coherent identity as a cultural district. The 1992 site lacks a unifying narrative, resulting in fragmented landscapes and degraded public spaces.

This observation supports theoretical frameworks emphasizing the role of soft factors (identity, narrative, heritage) in shaping urban continuity and also the necessity of aligning post-event functions with cultural memory and community expectations.

It also explains the resistance to certain redevelopment proposals noted in local debates, consistent with reviewer comments regarding traditionalist perceptions and attachment to historical images.

5.4. Discussions About International Post-Expo Experiences

Comparisons with international expositions show that Seville’s trajectory is not unique. Several patterns emerge:

- Vancouver 1986: delayed integration due to complex public–private partnerships.

- Lisbon 1998: successful redevelopment owing to strong state coordination and long-term planning.

- Zaragoza 2008: similar challenges of underused pavilions and incomplete post-event integration.

These examples reinforce the idea that institutional continuity and clear long-term objectives are decisive for successful legacy outcomes.

Seville’s 1929 site exemplifies best practices; the 1992 site illustrates the risks associated with institutional fragmentation and insufficient post-event strategy.

5.5. The Role of Research by Design in Mega-Event Regeneration

The proposed architectural and landscape intervention is not only a project but also a methodological instrument. In line with contemporary design research practice, the project synthesizes empirical findings, reinterprets existing infrastructures, re-establishes ecological continuity, reconnects fragmented spatial sequences, and provides a scalable model for degraded post-event landscapes.

This aligns with theoretical models of design-led regeneration, where architectural research contributes to identifying feasible trajectories for complex urban sites.

Furthermore, the project illustrates how adaptive reuse can be mobilized to preserve traces of exposition heritage while addressing environmental degradation.

The findings from Seville contribute to the broader literature by demonstrating the contrasting long-term effects of two exposition models within the same urban context; highlighting governance continuity as a more decisive factor than architectural typology alone; showing how research by design can bridge the gap between analysis and intervention; proposing an analytical framework applicable to similar post-event sites located worldwide.

5.6. Implications for Future Regeneration of Isla De La Cartuja

The discussion suggests that a sustainable future for the 1992 site depends on reducing institutional fragmentation through coordinated governance, establishing a unified identity aligned with Seville’s cultural landscape, investing in ecological restoration, activating public spaces to stimulate daily use, and integrating design-led solutions that reconnect isolated fragments.

These insights provide the conceptual basis for the intervention detailed in the Conclusions.

The attempt to revitalize the ensemble began through the current projects under development listed below:

- Naturalia XXI, which proposes opening the riverbank to the public, with pedestrian and bicycle paths, was a very important first step, namely, creating the city–Cartuja Island connection (existing proposal).

- Step 2 involves the revitalization project and creating a coherent waterfront, by implementing cultural functions (Museum of Contemporary Arts, Naval Museum, Science Museum) along the river; recreational functions, by revitalizing the Isla Magica amusement park; and relaxation functions, by revitalizing the parks along the Guadalquivir riverbank (a more complex proposal).

- Step 3 involves new projects for the Cartuja Island, such as the new Pelli tower—an office building with commercial spaces, terraces, and green areas at the base (existing proposal).

6. Conclusions

The most important change brought about by this exhibition was the transformation of the city, which was equipped with new roads, a high-speed train, a new airport, and new bridges that opened the northwestern area of the city to residents, and the large metropolitan park that benefits both the population of Seville and the metropolitan area.

6.1. Key Findings

The results demonstrate that the 1929 exposition achieved a high level of long-term integration due to its strategic urban location, permanent architectural structures, and consistent public management. In contrast, the 1992 site exhibits fragmented redevelopment patterns, uneven maintenance, and spatial discontinuities resulting from its peripheral location, temporary construction logic, and the complexity of its institutional framework.

Across both sites, three factors emerge as decisive for successful post-event reuse:

- Governance continuity, including coordinated long-term management and clear ownership structures.

- Spatial embeddedness, particularly the degree to which the site is integrated into existing urban networks.

- Post-event programming, which must ensure functional diversity, public accessibility, and a coherent identity.

These findings confirm and refine existing theoretical models on mega-event legacy and provide an analytical basis for evaluating similar urban contexts internationally.

In this way, after completing the steps mentioned above, the area will certainly gain life. Revitalizing an area that has reached this stage of degradation consists in finding the missing points, the negative points, and also the strong points that work. Creating a relationship between them is the solution. Implementing functions currently missing on the site (shopping, terraces, bars, relaxation spaces, green areas, cultural functions) will certainly help; they will open the area to the city, and they will make it easily accessible and attractive in the first place.

Step 3, which we talked about previously, is unfortunately almost impossible at the moment if we do not succeed in swaying public opinion. Seville is much too traditionalist; it does not accept this type of implementation in the city, claiming that it will ruin the way the city is currently perceived. Both the residents and a large percentage of those in charge of the city were in total opposition to the new office building proposal.

This scientific article is from the field of architecture and urban planning; therefore, the research methodology differs slightly from that of the exact sciences. The working methods are based on creativity, the introduction of new design elements, case studies, and construction variants that can be applied. The analysis begins with the situation of the municipality of Seville, which must manage the post-expo 92 area in a useful and pleasant way for the local community by combining several projects and solutions—of different utilities or of different architectural styles—into a common ensemble. Within the general efforts of rehabilitation of this site, our team proposes a targeted project for a certain part of the exhibition park, an original project that capitalizes on the location and introduces new architectural elements and specific functionalities, as well as efficient shading, ventilation, and lighting solutions.

6.2. Contribution of the Proposed Design Intervention

Based on the spatial diagnosis, the study introduced a design-led proposal for the rehabilitation of the former American Garden area within Isla de la Cartuja. The intervention operates as both an applied contribution, offering a feasible strategy for ecological restoration and public space activation, and a methodological demonstration of how research by design can support the transformation of degraded post-event landscapes.

The project illustrates how adaptive reuse of existing infrastructures, combined with landscape integration and programmatic diversification, can help re-stitch fragmented territories and reinforce the identity of the 1992 site.

The most important part of our project is the multifunctional center and botanical garden, with a clear description of the proposed solution, in terms of design and functionality. The economic, landscape, social, and technical advantages of the proposed solutions are difficult to evaluate, especially from a scientific research point of view, especially since these urban planning elements have not been materialized on site, and the economic or technical indicators are difficult to evaluate at this stage.

We believe that Seville would benefit enormously if it were no longer so traditionalist and thought about the future of the city in a much more open way. The same problem that existed when Seville was chosen as the expo site for 1992, when the inhabitants claimed that there was no need for this in their city, is exactly what is happening today. The inhabitants are somehow still living a long-gone dream, of what Isla de la Cartuja once was for the city, the 1992 Expo. They do not want to change anything; they want to revitalize the area and to bring the expo back to the city, exactly as it was in 1992 “que revive la expo’92”, but this should be reinterpreted and superimposed onto a 21st-century city, the Seville of 2025, which is no longer the one of 1992.

A few years ago, after presenting our project to the Seville City Hall, the municipality was very enthusiastic about the proposal, which took into account 100% of what existed on the ground during the 1992 exhibition and proposed an expansion and opening of the area to the city. They preferred, “due to lack of funds”, only a surface cleaning of the abandoned area, hoping in the future for a possible proposal of this kind on the site. This strengthened our conviction that, if Seville cannot overcome the barrier of what is currently in the city and does not try to overcome this moment, the city will not be able to develop and will stagnate. Indeed, these phrases have a personal perspective, but most of the conclusions are aimed at our original project or other rehabilitation projects of the Expo92 site.

The two exhibitions, the one in 1929 and the one in 1992, undoubtedly had a major impact on the urban structure of Seville; they left traces, without which today’s Seville could lose its identity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and A.A.A.; methodology, F.M.F.-I., and E.A.D.; software, A.S.; validation, A.A.A., A.S., and F.M.F.-I.; formal analysis, E.A.D.; investigation, A.A.A.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.F.-I.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, E.A.D.; supervision, F.M.F.-I.; project administration, F.M.F.-I.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fraga, F.J.M. Exposiciones Internacionales y Urbanismo. El Proyecto Expo Zaragoza 2008; Edicions UPC: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Pervolarakis, Z.; Agapakis, A.; Xhako, A.; Zidianakis, E.; Katzourakis, A.; Evdaimon, T.; Sifakis, M.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Stephanidis, C. A Method and platform for the preservation of temporary exhibitions. Heritage 2022, 5, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo, M. La Ciudad de las Exposiciones Universales; Monografías de Urbanismo; Gerencia Municipal de Urbanismo: Seville, Spain, 1985. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, R. The “Expo” and the post-“Expo”: The role of public art in urban regeneration processes in the late 20th century. Sustainability 2022, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]