Abstract

This article presents a novel methodology for assessing the visibility and reachability of cultural heritage objects within urban structures, tested through a pilot study in Kaunas New Town (Naujamiestis), Lithuania. While heritage protection policies usually emphasize architectural composition, details, and external visual protection zones, interior urban views and functional spatial dynamics remain underexplored. Building upon Space Syntax theory and John Peponis’s concepts of distributive and correlative situational codes, this study integrates detailed visibility analysis with graph-based accessibility modeling. Visibility was quantified through a raster-based viewshed analysis of building footprints and street-based observation points, producing a normalized visibility index. Reachability was examined using a new graph indicator based on the ratio of reachable polygon area to perimeter (A2/P), further weighted by the area of adjacent buildings to reflect the potential for urban activity. Validation against independent datasets (population, companies, and points of interest) confirmed the superior explanatory power of the proposed indicator over traditional centralities. By combining visibility and reachability in a bivariate matrix, the model provides insights into heritage objects’ dual roles as landmarks, everyday hubs, or hidden sites, and offers predictive capacity for evaluating urban transformations and planning interventions.

1. Introduction

The research is carried out within the scope of project Heritage in Depopulated European Areas (HerInDep) and aims to develop and test a novel methodology for assessing the visibility and reachability of cultural heritage objects within urban structures, using Kaunas New Town (Naujamiestis) as a case study, in order to expand heritage evaluation beyond architectural form and external protection zones by integrating spatial visibility analysis with graph-based accessibility modeling for predictive urban heritage assessment.

As stated in the Law on the Protection of Immovable Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Lithuania [1], the concept of an intermediate protection zone plays a central role in safeguarding cultural heritage. Such a zone is established around a protected object or site with the purpose of mitigating the potential negative impacts of human activity on its condition, perception, and long-term preservation. The legislation distinguishes two possible subzones within the intermediate protection zone, each serving a different function and governed by specific protection and use regimes: the physical impact protection subzone and the visual protection subzone.

The physical impact protection subzone is primarily intended to reduce direct physical threats to a heritage object, such as construction works, environmental changes, or other forms of intervention that may cause structural damage. The visual protection subzone, on the other hand, extends beyond the immediate boundaries of the protected object or its physical protection area. It encompasses surrounding land plots or parts thereof, along with immovable property situated within this area, and is subject to legal restrictions aimed at safeguarding the visibility of the cultural heritage object. Within such a subzone, activities that might obstruct, diminish, or otherwise negatively alter the visual perception of the object—such as the construction of high-rise buildings, dense development, or other visually intrusive interventions—are prohibited. In this way, the law seeks not only to protect the material integrity of heritage objects but also to preserve their role as visible elements of the urban landscape and cultural identity.

Nevertheless, the legislation also recognizes that the establishment of visual protection subzones is not universally necessary. Exceptions are made in cases where cultural heritage objects are located within reserves, protected areas, or designated cultural heritage sites, where the protection of visibility is already ensured at a broader territorial level.

The chosen research area—Kaunas New Town—exemplifies this exception. As a whole, it is recognized as a protected immovable cultural heritage site, and thus a visual protection subzone has been defined at the territorial scale. However, within this designated site, individual heritage objects or complexes do not benefit from separately established visual protection subzones. This situation creates a unique condition in which the overall urban fabric is formally protected, yet the visual emphasis of individual buildings or ensembles remains unregulated. The visibility of buildings is partially regulated by defining protected perspectives toward specific historical landmarks, however, in some cases, the lack of specificity allows for interpretive flexibility. Consequently, questions of visibility and reachability within Kaunas New Town acquire particular importance, as they highlight the potential gaps between legal protection frameworks and the actual spatial experience of cultural heritage in the city.

The research is guided by the following questions:

- How visible are individual cultural heritage objects within the contemporary urban landscape?

- How do visibility and reachability interact spatially, and what combined patterns emerge in identifying landmarks, everyday nodes, or hidden heritage sites?

- How can these combined indicators support predictive assessment of future urban transformations and inform heritage protection or planning interventions?

By combining visibility and reachability indicators, the study aligns its aims with UNESCO-oriented heritage management needs, offering a predictive, computation-based approach that supports more informed and future-oriented conservation planning. Although visibility is formally recognized in heritage legislation and UNESCO guidance, its operationalization is often limited to static, externally oriented panoramas, leaving internal urban views and everyday perceptual exposure largely unexamined. Reachability, in turn, is rarely incorporated into heritage assessment despite UNESCO’s emphasis on living heritage, experiential continuity, and the integration of cultural assets into daily urban life. Together, visibility and reachability capture the dual logic of how heritage functions in the city, as visual anchors that structure collective identity and as accessible nodes that support social interaction, use, and meaning-making. By combining these two dimensions, the study aligns directly with UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach, which calls for heritage evaluation frameworks that reflect both spatial perception and functional connectivity. This combined analytical perspective also addresses a critical gap in current Lithuanian and international practice, where legal protection often focuses on object-based or façade-level criteria and overlooks how people actually see, reach, and experience heritage in situ.

The aim of this study is to design and propose a new methodology to enable the impartial, computation-based evaluation of the importance of heritage objects based on their importance and visibility. To achieve this aim, the research designs a methodology that incorporates state-of-the-art research and relevant technology, considering availability of data; proposes a new metric based on a combination of Digital Surface Models (DSM) and Thematic Digital Surface Models (TDSM), viewshed, space syntax, mathematical graph, and Spatial Design Network Analysis (sDNA); evaluates a methodology in a case study of Kaunas, Lithuania; and recommends a list of most important indicators and strategies regarding the use of this methodology.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conventional Approaches to Visual Protection and Their Limitations

Kaunas New Town district in Lithuania is renowned for its concentration of interwar modernist architecture, recently recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. This urban heritage is not only embodied in individual buildings but also in the spatial structure of the cityscape that emerged when Kaunas rapidly urbanized as the provisional capital in the 1920s–1930s [2]. Preserving such heritage requires careful evaluation of its cultural value and its role in the urban environment. However, current heritage assessment practices have notable limitations. Typically, the “valuable features” of immovable heritage are defined in terms of physical attributes—e.g., architectural composition, stylistic details, building plans, or street layouts. Visual relationships are addressed mainly through external view protections, such as designated panoramas, silhouettes, or sightlines safeguarded by visual protection zones. These conventional approaches focus on how a protected building looks from the outside, while neglecting other crucial aspects of spatial experience. Notably, internal visibility—how a heritage object is seen or experienced from within the surrounding urban space—is seldom considered. However, a different approach towards urbanism, having deep historical roots and at the same time highlighted as valuable by contemporary urbanists and thinkers [3,4,5,6], exists.

2.2. Historical and Theoretical Grounding of Spatial Experience: Apopsia and Dynamic Urbanism

In the history of urbanism, a fundamentally different dynamic model has been applied to the formation of the cityscape, which is based on the principle of apopsia. Apopsia is described in the treatise “On the Law or Conventions in Palestine” by the 6th century architect Julian of Ascalon [3]. In Julian’s of Ascalon treatise apopsia is defined as a view of a certain area or object (from a certain point), which gives the right to prohibit adjacent construction [6]. The essence of this principle is that the cityscape is not formed as a work of one author and is not preserved as a composition that has developed in one way or another, only to be changed up to certain limits, but it indicates what the objects of the urban environment are and from which zones or points they should be visible. In other words, it is not the composition itself that is created, but its most important formants that must be preserved in the event of any transformation of the cityscape are named. Thus, the application of apopsia eliminates the contradiction between the need to form the composition of the cityscape and the spontaneous formation of the urban environment [6]. The expediency of the application of apopsia in modern urban planning was thoroughly substantiated by Petrušonis [4,5]. According to Petrušonis [5], such approaches as apopsia are important for their holistic nature, emphasizing cooperation, organic development of the environment. They show how, through negotiation, establishing mutual conditions and harmonizing interests, a solution acceptable to all parties is found. Such documents clearly emphasize the importance of local specific circumstances, determined according to the specific capabilities of the negotiating parties. According to Zaleckis [6], this dynamic model of urban landscape formation has many advantages, including the solving of the contradiction between the dynamic nature of the cityscape and the need to consciously shape it; also model based on apopsia would allow for an accurate assessment of the peculiarities of each specific urban situation; it can be stated as well that the principle of apopsia focuses not on the formal aesthetics of the city, but on the formation of the already mentioned universal pattern (by also identifying and preserving the elements of the pattern characteristic to specific location).

Furthermore, when assessing the impact of new developments on historic urban fabric, planners often rely on expert opinion and static visualizations. Such methods are inherently subjective and of limited reliability, as they cannot fully capture the dynamic ways people actually perceive and move through the city. Prevailing evaluations tend to ignore the underlying logic of urban space functionality—for example, how street network configuration guides pedestrian movement or access to heritage sites. A well-established example of incorporating viewer exposure into landscape evaluation comes from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) Visual Resource Management program. The BLM uses a two-part process: a Visual Resource Inventory (VRI) to catalog baseline scenic values, and a Visual Impact Assessment (VIA) to evaluate proposed changes. Notably, “visual sensitivity” in the BLM system is defined as “a measure of public concern for scenic quality,” determined by the types and numbers of potential viewers, the level of public interest, surrounding land uses, and any special designations of the area. In practice, this means that areas seen by more people or by highly interested groups (such as tourists, recreationists) are assigned higher sensitivity [7]. Although the BLM approach was developed for natural landscapes, the underlying concept that the more intensively a viewpoint is used, the more sensitive it is can be applied equally to urban environments. For example, internal urban views can be very sensitive if they are widely experienced or cherished by the public. Contemporary research supports incorporating use intensity into visual assessments in the urban context. In fact, some new assessment frameworks explicitly include metrics like “number of viewers” and “viewer activity” in determining a view’s sensitivity or public concern level [8]. This means an internal urban view can be rated more sensitive not just for its aesthetic merits, but because it is observed by many people (or by particularly sensitive observers). Academic literature on visual quality confirms that the context of viewing matters: the significance of a view rises when large audiences are present to appreciate (or be impacted by) it [9]. Importantly, urban planning and heritage conservation practices have started to formalize the protection of such high-sensitivity internal views. For instance, UNESCO and ICOMOS guidance on Historic Urban Landscapes emphasize preserving key view corridors as fundamental to maintaining a city’s identity [10]. This justifies that incorporating viewer sensitivity based on use intensity provides a strong justification for prioritizing internal urban views in planning decisions.

The theoretical framing of visibility and reachability in urban heritage evaluation can be strengthened by linking it to broader heritage theory concepts, such as place identity, spatial perception, and cultural value. Place identity is shaped not only by architectural attributes but by how people perceive and engage with space over time. As Relph [11] argues, meaningful places arise from the integration of physical setting, activity, and psychological associations. In this view, visibility and reachability contribute directly to the sense of place by influencing how often heritage elements are encountered and embedded in daily urban routines. Spatial perception also plays a critical role; according to Norberg-Schulz [12], the legibility of space and the prominence of landmarks are essential for individuals to orient themselves and attribute meaning to their environment. Additionally, cultural value, as outlined by Smith and Campbell [13], extends beyond formal aesthetics to include the lived experiences and interactions that heritage enables. Therefore, quantifying visibility and reachability helps assess how effectively heritage objects support place attachment and social meaning through both perception and use.

2.3. International Planning Instruments for Visual Protection

In the United Kingdom, specific view corridors, vantage points and height limits are set. An example is the London View Management Framework (LVMF), which sets out the above aspects in the urban environment [14,15]. Such views should be visible from publicly accessible and widely used locations. They include significant buildings or cityscapes that help define London at a strategic level. These views represent at least one of the following categories: panoramas covering large parts of London; linear views of landmarks framed by landscape features; river perspectives along the Thames; significant cityscapes. Many cities in the UK have similar local instruments (Supplementary Planning Documents, core strategies).

In Germany, the protection of heritage and landscape/views is addressed through a combination of federal, state (Länder) legislation and local plans. Although there is no single national “model” for “protected views” like the LVMF, many cities apply a detailed regulated principle of protecting the cityscape (Stadtbild) (e.g., view corridors, height restrictions, etc.) [16].

In France, there are mandatory annexes to urban plans, which regulate how to manage the environment, changes in facades, new constructions, in order to preserve the visual character of the area. Protection is often integrated into the PLU (local urban plan) with specific regulations for facades, height, materials; it is decided at the local level which visible connections/panoramas are to be protected. In 2016, the classification as remarkable heritage sites was carried out. Remarkable heritage sites are “ towns, villages or districts whose conservation, restoration, rehabilitation or development is of public interest from a historical, architectural, archaeological, artistic or landscape point of view” [17]. The impact of classifying such objects is based on: the obligation to take this into account when defining urban planning documents, performing architectural expertise works related to buildings located on the perimeter of an outstanding heritage site, etc.

2.4. Identified Research Gaps and Rationale of the Study

To synthesize the main theoretical and methodological approaches discussed above, Table 1 summarizes their core contributions and highlights key limitations addressed by this study.

Table 1.

Key conceptual frameworks and methods reviewed in the literature. Sources include Relph [11], Norberg-Schulz [12], Smith and Campbell [13], BLM Visual Resource Inventory [7], UNESCO HUL guidance, and national frameworks in the UK, France, and Germany.

This research addresses several significant gaps in urban heritage evaluation methodologies. First, conventional approaches focus heavily on architectural form and static visual zones, often disregarding how heritage is experienced from within the interior spaces of the city and movement flows. Internal views, although crucial to everyday perception and spatial memory, are typically under-regulated or evaluated qualitatively, if at all. Second, current impact assessments frequently rely on expert judgment and visualizations that lack replicability or predictive strength. The analysis of literature has revealed that while existing methodologies offer strong theoretical bases for spatial analysis, they rarely translate into actionable frameworks for systematically assessing the spatial exposure and accessibility of heritage objects. There is also a limited intersection between cultural value theories and quantitative spatial analysis, leaving a conceptual gap in how visibility and reachability relate to place identity and public perception. These observations reveal the need for data-driven tools that can complement traditional heritage appraisals by accounting for spatial dynamics. Recent advancements in computational methods have significantly enriched the field of heritage visibility and spatial analysis. Contemporary studies increasingly utilize GIS-based viewshed modeling, isovist analysis, and network-based spatial metrics to assess how heritage elements are visually and spatially integrated within urban environments [18,19]. These approaches support more nuanced and scalable evaluations of visual exposure and accessibility, especially when combined with street network analysis. The conceptual direction of this study aligns with this growing body of research, contributing to the development of integrative methods that link spatial structure with experiential and cultural value.

3. Study Area

The research area, Kaunas New Town, is an important urban territory that contains a large number of heritage objects. In 1999, this territory was inscribed in the Register of Immovable Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Lithuania as a site of national significance protected by the state. The designated valuable features of the area are classified as architectural (significance determined as rare), engineering (significance determined as typical), historical (significance determined as unique), landscape, urban (significance determined as unique), and greenery (significance determined as important). The valuable characteristics of the territory include its spatial plan, which, according to the 1847 design project, follows a regular central layout with a rectangular street grid. This grid was expanded during the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. Based on the 1871 approved plan, the southern suburb known as Karmelitai was incorporated, featuring a regular spatial structure while also retaining traces of spontaneous development. Beyond the planned structure, the valuable elements of the territory also encompass streets, squares, access roads, passages, pathways and their surfaces, as well as natural features. One of the most significant characteristics of the area is its volumetric-spatial composition, consisting of immovable cultural heritage objects, structures with valuable features located within the territory, and buildings forming the urban structure. The historical urban fabric is distinguished by its principal functional and compositional centers: St. Michael the Archangel (Garrison) Church on Nepriklausomybės Square, the State Theatre (now Kaunas State Musical Theatre) situated across from the City Garden square, and the axis connecting them-Laisvės Avenue, the main compositional axis of the New Town. The Vytautas the Great Museum complex together with Unity Square forms the compositional-cultural center of the northern part of the territory, unified into a coherent urban structure by another compositional axis-Daukanto Street, perpendicular to Laisvės Avenue, which terminates in the north at the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and in the south at Nemunas Island. Parallel to this axis runs Gedimino Street, a historic compositional link between two key sacral dominants of New Town: St. Michael the Archangel (Garrison) Church and the Church of the Holy Cross (known as Karmelitai). The functional–compositional center of Kaunas New Town is the Railway Station Palace, towards which the compositional axis of this part of the city—Vytauto Avenue—leads. In the Register of Protected Properties, the key dominants of this territory are identified as St. Michael the Archangel (Garrison) Church, the Church of the Holy Cross, the Vytautas the Great Museum complex, and the Kaunas State Musical Theatre. An important dominant of the historical part of Kaunas, known as New Town, is also the Church of the Resurrection of Christ. Although it lies outside the designated territory, it constitutes a powerful visual landmark, visible from many locations across Kaunas [20].

The valuable attributes of the state-protected area of Kaunas New Town encompass both large-scale urbanistic features and the architectural and historical characteristics of individual buildings. Urban values include the perimeter layout of blocks, street lines and plot boundaries, the relationship of public spaces (squares, streets, avenues) and the Nemunas river to the urban fabric. Architectural attributes include facade composition, decorative elements, height and volume ratios, as well as the arrangement of pediments and loggias. Material values comprise authentic masonry structures, window and door fittings, interior representative spaces, and, in some cases, original interiors. The protection of these features is established in special planning documents and entries in the Cultural Heritage Register [21]

Kaunas New Town is also notable for its abundance of interwar-period buildings, which in 2023 were inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Modernist Kaunas: Architecture of Optimism, 1919–1939 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List under criterion (iv) as an example of a historic city center undergoing rapid urbanization and modernization, while at the same time serving as the temporary capital of Lithuania (1919–1939). It reflects the diverse values and aspirations of the local population to create a modern city, driven by post-war optimism and faith in an independent future during the turbulent early decades of 20th-century Europe [2].

One of the most prominent examples is the Kaunas Central Post Office (Laisvės Ave.). In 2021, the Government approved its inclusion in the list of historical and cultural objects of national significance, granting the building national importance. Constructed in 1932 and designed by architect Feliksas Vizbaras, it is considered one of the most important interwar representative state buildings, exemplifying modernist architecture in Kaunas. Its valuable features include distinctive interwar modernism, facade composition, representative interior spaces, and historical-cultural significance for both the city and the country [22].

Another example is the Kaunas Garrison Officers’ Club (A. Mickevičiaus Str. 19). This building represents a synthesis of interwar modernism and a distinctive national style. Its valuable features include facade composition, the layout of interior and representative halls, original historical architectural elements, and the building’s social and historical significance as an officers’ club [23].

In addition to these, New Town contains many individual residential and administrative buildings that are protected at regional or local levels. Such objects are valued not only for the individual buildings themselves but also for their contribution to the urban structure, the integrity of the historic urban fabric, and their authenticity.

The legal status of the territory’s protection is regulated by the laws of the Republic of Lithuania [24], territorial planning documents valid in the urbanized territory, etc. Some aspects of the territorial protection of Kaunas New Town are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Legal protection status of Kaunas New Town.

In the case of Kaunas New Town, the legal protection status is strong at the territorial level, but there are no clear regulations on heights, visual corridors or reference points, so it is necessary to evaluate each project proposal with additional methodologies (GIS, Space Syntax, visibility models).

4. Methodology

4.1. Theoretical Background and Research Rationale

Understanding the spatial logic of heritage environments requires tools capable of linking physical form, perception, and movement into a coherent analytical framework. Traditional heritage evaluation often relies on qualitative interpretation or visual inspection, which, while valuable, cannot fully reveal how spatial configuration shapes accessibility, visibility, and experiential hierarchy. To address this limitation, this study adopts a simulative modeling approach grounded in Mathematical Graph-based models of the network of urban spaces, which enables the quantitative exploration of relationships between spatial form and social or perceptual phenomena.

In such models, streets or spatial segments are represented as nodes and their intersections as links, allowing the city to be analyzed as a network whose topology encodes spatial relationships among its parts. As Hillier and Hanson [25] note, “the configuration of space itself can be represented as a pattern of relations rather than as geometry alone”, while Batty [26] emphasizes that “urban structure emerges from the networked connectivity of lines of movement rather than the geometry of built form.” This graph-based representation makes it possible to compute centralities, such as integration, closeness, or reachability, that describe how easily different parts of the street network can be accessed or perceived. Thus, through measures of spatial configuration, visibility, and reachability, it becomes possible to examine how urban form mediates both functional access and cultural meaning within protected areas.

Within this theoretical context, Peponis [27] identifies two fundamental situational codes that describe how spatial systems structure human experience: distributive and correlative. As he explains, “Distributive codes place emphasis on understanding where things are so that they can be accessed. Correlative codes place emphasis on understanding how things are related in space and what opportunities, affordances, or restrictions ensue from their relationship.” Peponis further clarifies that “in order to get to anything located in space, one has to understand spatial relationships, such as adjacency and connection, and plot a path from ‘here’ to ‘there.’”

He illustrates these two logics through an everyday distinction: “I may move from one location to another only because I want to get something that is there, or I may move from a location to another because I want to look at something in front of me from a different angle. In the first case, my reading of space can be interpreted as relying on a distributive code only. In the second case, my reading of space necessarily implies a relational code.” The first reflects a logic of access and distribution, while the second represents a relational or perceptual logic that gives form to meaning. Together, they define the dual nature of spatial understanding—functional and experiential—that underpins urban morphology and spatial culture.

In the context of heritage protection, both codes are equally significant. A strong correlative code characterizes visually dominant or symbolically charged structures such as church towers, town halls, or monuments that organize perception and orientation. A strong distributive code, in contrast, reflects the accessibility and integration of significant buildings within the everyday spatial network. Building on these ideas, the present study proposes to analyze heritage environments through the combined lenses of visibility and accessibility, corresponding to the correlative and distributive aspects of spatial configuration. This approach allows the interplay between perception and movement to be explored empirically, revealing how cultural and functional hierarchies are embedded within the spatial form of protected urban areas and how these patterns contribute to the legibility and continuity of cultural identity.

To operationalize both situational codes proposed by Peponis [27], the methodological framework must specify clear analytical parameters that translate the perceptual and functional aspects of space into reproducible metrics. Each parameter, such as observer height, sampling density, network radius, weighting factors, and polygon thresholds, was selected to correspond explicitly to either the correlative or distributive dimension of spatial logic. This ensures that the resulting indicators do not merely represent computational artifacts but remain theoretically grounded in the spatial experience of heritage areas. To support transparency, reproducibility, and theoretical alignment, all analytical choices are explained in the following sections and summarized in Table 3.

4.2. Visibility Analysis (Correlative Code)

The visibility analysis was designed to represent the correlative situational code described by Peponis [27], emphasizing the perceptual and relational aspects of urban space. In this study, visibility serves as a proxy for the degree to which individual buildings contribute to, or are structured by, the visual field of the city. The procedure was implemented using GIS-based raster and vector operations, combining Digital Surface Model (DSM) data, Thematic Digital Surface Model (TDSM) data, building footprints, and street-network geometry.

Data for DSM and TDSM was acquired using Lithuanian national GIS data distribution site [28]. Although the dataset that was used is distributed in LAS format, requiring additional processing, nevertheless it enabled production of TDSM which was otherwise unavailable [29]. Raster datasets were generated using QGS LAS processing toolbox, by coding required logical equations in Export to raster (using triangulation) tools filter [30]. Although DSM raster was readily available in the aforementioned site, it was generated anew to ensure consistency and not to derail research in finding wrong phenomena of difference of datasets from diverse sources.

To capture the visual conditions of the urban environment, two visibility scenarios were modeled: one with trees (DSM) and another without trees (TDSM), allowing for the assessment of vegetation’s influence on the visibility of built heritage. Observation points were generated along the central street lines at 10 m intervals, representing potential positions of pedestrians or observers.

For each scenario, the Viewshed Analysis tool in ArcGIS Pro (Version 3.x) [31] was applied to the DSM raster to produce binary visibility maps, where each cell value indicated whether the corresponding location was visible (1) or not visible (0) from the observer points. These rasters formed the basis for a building-level visibility assessment.

Building footprints were then converted from polygons to lines, and points were generated along each building perimeter at 1 m intervals. Raster visibility values were extracted to these perimeter points, after which a spatial join was performed to summarize visibility per building polygon. The sum of visible points along each perimeter was used as an indicator of total visual exposure.

Finally, the resulting values were normalized by dividing them by the maximum value within the dataset, producing a 0–1 scale of relative visibility. This normalization ensured comparability between scenarios and building categories. The derived indicators as visibility with trees, without trees, and their combined geometric mean, enabled the quantitative assessment of the correlative code across different typological groups of buildings within the protected area. For consistency, visibility indicators were standardized using the following notation: visibility without trees visibility without trees V_NT, visibility with trees V_WT, and combined visibility V. The final indicator is defined as the geometric mean:

V = √(V_NT V_WT)

The geometric mean was selected because it prevents extremely high visibility in one scenario from compensating for very low visibility in another, reflecting the fact that pedestrian visual experience is constrained by the most obstructed condition.

To integrate the two visibility scenarios into a single representative measure, the geometric mean of the visibility values with and without trees was calculated for each building. The geometric mean was chosen because it appropriately reflects the multiplicative relationship between the two conditions: visibility in open space and visibility constrained by vegetation. This method prevents disproportionately high visibility in one scenario from compensating for very low visibility in the other, resulting in a balanced and realistic index of overall perceptual accessibility. Consequently, the combined indicator captures both the inherent visual structure of the urban form and the moderating influence of vegetation, providing a robust representation of the correlative code in heritage environments.

The parameters chosen for visibility modelling derive from established spatial perception research and aim to approximate how pedestrians experience visibility in historic urban environments. An observer’s height of 1.75 m reflects the average human eye level and is commonly used in visibility studies to represent everyday perception conditions. The 10 m spacing of observer points along the street network balances computational efficiency with adequate spatial resolution, ensuring that no major perceptual gaps occur in the analysis. A 1 m sampling interval along building perimeters captures façade exposure with sufficient granularity, particularly important in the fine-grained street-block structure of Kaunas New Town. The use of DSM and TDSM datasets enables the separation of built form and vegetation effects as a critical distinction in interwar modernist districts where tree canopies not only around the investigated area but also inside the streets substantially shape visibility structure. The Old Town of Kaunas, with traditional medieval street spaces without trees, can serve as an opposite example. could be.

4.3. Reachability Analysis (Distributive Code)

The second component of the study, reachability analysis, represents the distributive situational code as defined by Peponis [27], focusing on how spatial structures support access, movement, and the distribution of activities across the urban network. While accessibility can be interpreted through behavioral data, such as pedestrian flows or activity densities, simulative graph-based models enable its systematic estimation from the spatial configuration itself, evaluating the reachability of each urban space within the street network based on calculations of graph centralities.

In this research, a graph-network model was constructed using street segments as nodes and intersections as links, following the principles of the segment-link modelled with the sDNA tool [32]. This allowed the identification of streets with higher movement potential and stronger functional integration or better reachability. A variety of graph centralities may serve as proxies for the distributive code, such as closeness, gravity (integration), metric reach, or total network length etc. Closeness centrality measures how easily a segment can be reached from all other segments in the network: it represents the average distance from one street to all others and thus indicates potential accessibility. Gravity or integration centrality evaluates how movement is likely to concentrate in specific segments by weighting proximity by distance, describing spaces that attract more through-movement or interaction. Total network length quantifies the total length or number of segments reachable within a given metric radius, reflecting local-scale permeability. Finally, total network length expresses the cumulative accessible distance from a segment to all others, offering a global measure of spatial connectedness.

However, these traditional measures are often sensitive to variations in street network density, which in the case of Kaunas New Town, is relatively low compared to the other parts of the historical city core (e.g., Old Town (Senamiestis)).

To overcome this limitation, a new reachability indicator was developed and tested as an alternative to conventional centrality measures as proposed in Zaleckis et al. [33]. The proposed metric is based on the geometric relationship between the area (A) of the polygon reachable from a given street segment and its perimeter (P). This ratio provides a scale-independent measure of spatial compactness and accessibility. To ensure clarity and comparability, the reachability indicator used in this study is defined using standardized notation. Let A denote the area of the polygon reachable from a street segment within radius r (1000 m), P the perimeter of that polygon of the reachable area within the street network, and GK is the total area of buildings supporting street culture. The final metric is defined as:

HAP2GK = A/P2 GK

This indicator expresses spatial compactness (via A/P2) weighted by socially active or potentially supporting street culture besides building footprints, reflecting both geometric and functional accessibility. GK was identified as the geometrical mean of buildings supporting street culture (industrial, military, storage, and similar buildings excluded). The choice of two weighting distances, 30 m and 400 m, was based on the need to capture different spatial scales at which street-culture-supporting buildings influence urban life. The 30 m radius reflects the immediate street-edge environment and includes buildings that directly shape the perceptual and functional conditions of a given segment (e.g., active façades, entrances, ground-floor uses). The 400 m radius represents a broader neighborhood-scale catchment, allowing the metric to account for buildings located inside perimeter blocks or slightly deeper within urban fabric, which nonetheless contribute to activity density, movement potential, and the overall socio-spatial richness of an area. Combining these two scales through a geometric mean ensures that both immediate frontage and wider contextual activity are incorporated without allowing either to dominate the weighting. The geometric mean was selected because it balances the influence of building areas at 30 m and 400 m without allowing disproportionately large values at one scale to dominate the indicator, thus reflecting the multiplicative and mutually reinforcing nature of immediate frontage activity and broader neighborhood vitality.

Its selection was validated empirically (Section 4.5), where it demonstrated the strongest and most consistent correlations with independent datasets. Additional validation of the model, made especially for the presented research and the investigated area, is presented in Section 4.5.

To enhance the interpretative value of the model, the reachability results were weighted by the area of buildings contributing to street culture, excluding industrial or storage structures, as conducted in Zaleckis et al. [33]. This weighting emphasizes the accessibility of spaces that actively support urban life rather than merely reflecting geometric connectivity.

All calculations were conducted within a 1000 m radius, representing an approximate 10–15 min walking distance, which is most relevant for the experiential scale of the study area. The resulting segment-based reachability values were then spatially joined in ArcGIS Pro (Version 3.x) to building polygons using a 30 m threshold and mean value aggregation to assign reachability scores to individual buildings.

This approach allows the distributive code to be expressed as a measurable property of urban form, describing how easily different types of buildings, especially heritage-related ones, can be reached and integrated within the surrounding spatial network.

All buildings were classified into four groups to support differentiated analysis: (1) Cultural Heritage Objects (KPO), representing buildings formally listed in the national heritage register; (2) Buildings with Valuable Heritage Characteristics (VSPT), identified through municipal “valuable properties” datasets; (3) Urban-Structure-Forming Structures (USFS), representing buildings that define block morphology or street enclosure; and (4) Other Buildings (KS), representing all remaining structures. These classifications were derived from the Lithuanian Cultural Heritage Register and Kaunas municipal GIS datasets.

4.4. Integration of Correlative and Distributive Codes: Combination of Visibility and Reachability

To explore the relationship between the correlative and distributive dimensions of spatial structure, visibility, and reachability, results were compared not through a single combined index but by constructing a two-dimensional interpretative matrix. This matrix represents the interaction between the perceptual and functional characteristics of urban form, illustrating how buildings differ in both their visual prominence and their accessibility within the street network.

For visualization, a bivariate (two-color) symbology was applied in ArcGIS Pro (Version 3.x) [31]. Visibility values (representing the correlative code) were placed along the x-axis, while reachability values (representing the distributive code) were placed along the y-axis. Both indicators were divided into three classes: low, medium, and high while using natural breaks. The resulting 3 × 3 matrix contained nine color squares, each corresponding to a distinct combination of visibility and reachability levels.

This visualization approach allowed the identification of characteristic spatial patterns, such as areas where buildings are both highly visible and easily reachable, or conversely, visually prominent yet spatially secluded. The bivariate color scheme thus provided an intuitive and spatially explicit means of interpreting how correlative and distributive properties intersect across the protected area, supporting comparative evaluation of heritage and non-heritage structures within their broader urban context.

4.5. Validation of the Initial Reachability Results and Selection of the Final Reachability Indicator

sDNA toolbox [32] for ArcGIS Pro (Version 3.x) [31] was chosen for modelling of reachability of street segments and buildings accordingly, as it provides the biggest selection of graph centralities which could be calculated, including area and perimeter of the polygons covered by the street network. To validate the idea of new centrality based on the area and perimeter of the polygon reachable from every street segment within a radius of 1000 m, it was compared with more traditional graph centralities calculated by sDNA:

Mean Euclidean distance (MED) calculated as the sum of distances from every graph node (street segment between the crossroads) and other segments divided by their number; network quantity penalized by a distance [34].

The Network Quantity Penalized by Distance (NQPD) centrality is a gravity-based form of closeness that considers both the quantity of reachable opportunities and their distance within the street network. It balances accessibility and proximity by weighting nearby destinations more strongly than distant ones, providing a nuanced measure of movement potential and spatial integration [34].

Betweenness centrality (BtBE), measures how often a street segment lies on the shortest paths between all other pairs of segments in the network, indicating its role as a connector or potential movement corridor. Segments with high betweenness serve as critical links that channel flows through the system, reflecting their structural importance in facilitating through-movement. In sDNA, betweenness is computed using geodesic paths, with endpoint contributions weighted proportionally to account for average journey start and end positions [34].

Length (Len) represents the total length of network segments that fall within a specified radius from each analyzed element. It reflects the overall spatial extent or density of the street network accessible from that point, providing a simple measure of potential movement range [34].

Angular Distance in Radius (AngD) measures the cumulative angular change required to move through the network within a given radius. Rather than relying on metric distance, it captures the degree of directional change between connected segments, offering an indicator of visual and cognitive simplicity in route choice [30].

The proposed indicators were the area of the reachable polygon squared within the street network divided by its perimeter (A2P); A2P weighted by the area of buildings supporting street culture within 30 and 400 m, counted as geometric mean between the areas (A2PGK); A2P weighted by the area of all buildings within 400 m (A2PALL); area divided be perimeter and weighted by the area of buildings supporting street culture (APGK); area divided by the perimeter squared and weighted by buildings supporting street culture (AP2GK); areas divided by perimeter squared (AP2); AP2 multiplied by Len.

To check which indicators, and especially if the newly proposed one is working better, the correlations between graph centralities and the following data were conducted: density of population in urban blocks [35] intersected with the street network within 20 m distance; points of interest (POIS) from the Open Street Map [36] (all POIS and just ones which could be associated with urban structures were taken) intersected with the street network within 400 m distance; commercial enterprises (Imonės) based on the official data [37] intersected with the street network within 400 m distance. All tested indicators systematized in Table 3, while correlations are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Summary of proposed and tested reachability indicators.

Table 3.

Summary of proposed and tested reachability indicators.

| Indicator | Formula/Definition | Components/Notes | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A2P | A2/P | A-area; P-perimeter | Spatial compactness of reachable space; sensitive to area expansion |

| A2PGK | A2/P GK | GK-geometric mean of street-culture buildings (30 m and 400 m) | Weights compactness by activity-supporting buildings at multiple scales |

| A2PALL | A2/P ALL | ALL-total building area within 400 m | Influence of total built volume in neighbourhood context |

| APGK | A/P GK | A-area; P-perimeter; GK-cultural-activity weight | Simplified compactness measure weighted by local + neighbourhood activity |

| AP2GK | A/P2 GK | A-area; P-perimeter; GK | Emphasises compact, well-connected shapes; penalises fragmentation |

| AP2 | A/P2 | Area and perimeter only | Scale-independent geometric compactness |

| A2P_Len | A2/P Len | Len-network length within radius | Adds reachability via network density |

| MED1000 | Mean geodesic length is the mean length (always in Euclidean metric) of all geodesics or streets in the radius referred as Closeness Centrality in Graph theory [34] | Mean Euclidean Distance (1000 m radius) | Evaluates closeness of reachability of spaces simply based on distances but neglecting density of street network |

| NQPDE1000 | NQPD is a form of closeness, commonly referred to as a gravity model, that takes into account both quantity and accessibility of network weight. By contrast, Farness takes into account only accessibility, while Weight takes into account only weight [34] | Network Quantity Penalised by Distance | NQPD reflects both distances between streets and density of street networks while prioritizing the last one. It was not working very well in the investigated area because of big size of urban blocks |

| BtBE1000 | Betweenness. counts the number of geodesic paths that pass through a graph node or street segment/group of segments, i.e., the number of times the segment lies on the shortest path between other pairs of vertices [34] | Betweenness centrality (1000 m) | It shows potential transit flows of the pedestrians and was considered worth trying in the proposed model |

| Len1000 | Length (Len) is the total network length in the radius [34] | Total network length (1000 m) | Represents not only a density or number of streets segments as nodes of the graph, but reflects the total perimeter of the accessible streets with radius. In some research it is correlated with more intensive street culture and higher diversity of public urban spaces catalysing social interaction [38] |

| AngD1000c | Angular distance (Ang Dist or AngD) is the total angular curvature on all links in the radius [34] | Angular Distance (1000 m, cumulative) | The indicator in essence reflects better visibility of the calculated street segment as smaller angular distance means more straight angles in the street layouts around it |

| POP20m | Sum (population in blocks intersecting street centrelines within 20 m) | Population data from SSVA; 20 m captures only blocks directly influencing street life | Represents immediate residential intensity supporting or constraining street vitality |

| pois400 | Count (POIs within 400 m) | OSM points of interest; distance corresponds to ~5 min walk | Captures access to amenities, including POIs located inside large buildings |

| pois400urban | Count (urban-use POIs within 400 m) | Filtered OSM POIs relevant to urban life (culture, commerce, services) | Represents density of urban-relevant attractors influencing pedestrian movement |

| imones400 | Count (commercial establishments within 400 m) | Data from National Register Center; 400 m = behavioural catchment | Indicates concentration of businesses affecting local economic activity and street culture |

Table 4.

Pearson correlations and Spearman’s rho. Green color marks moderate correlations; orange marks strong correlations. All ** marks 0.01 level significance of correlations. The underlined bold font marks the indicator used for the final modelling. Green and orange colors mark higher correlations. Numbers besides the abbreviations show radiuses of calculation (1000 m) and distance of data intersection (20 and 400 m).

Table 4.

Pearson correlations and Spearman’s rho. Green color marks moderate correlations; orange marks strong correlations. All ** marks 0.01 level significance of correlations. The underlined bold font marks the indicator used for the final modelling. Green and orange colors mark higher correlations. Numbers besides the abbreviations show radiuses of calculation (1000 m) and distance of data intersection (20 and 400 m).

| Pearson Correlation | ||||||||||||

| MED1000 | NQPDE1000 | BtBE1000 | Len1000 | AngD1000c | A2P | A2PGK | A2PALL | APGK | AP2GK | AP2 | A2P_Len | |

| POP20 m | 0.134 ** | 0.136 ** | 0.162 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.234 ** | 0.174 ** | 0.229 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.189 ** |

| pois400 | 0.105 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.199 ** | 0.357 ** | 0.234 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.243 ** | 0.373 ** |

| pois400urban | 0.088 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.308 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.211 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.203 ** | 0.399 ** |

| imones400 | 0.183 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.627 ** | 0.640 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.535 ** |

| Spearman’s rho | ||||||||||||

| MED1000c | NQPDE1000c | BtBE1000c | Len1000c | AngD1000c | A2P | A2PGK | A2PALL | APGK | AP2GK | AP2 | A2P_Len | |

| POP20m | 0.222 ** | 0.417 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.359 ** | 0.309 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.621 ** | 0.714** | 0.710 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.706 ** |

| pois400 | 0.184 ** | 0.451 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.556 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.423 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.410 ** | 0.340 ** | 0.420 ** |

| pois400urban | 0.182 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.400 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.377 ** | 0.341 ** | 0.385 ** |

| imones400 | 0.278 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.495 ** | 0.687 ** | 0.565 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.586 ** | 0.548 ** | 0.550 ** | 0.390 ** | 0.559 ** |

To determine the most suitable indicator for representing reachability, several graph-based centralities were tested and validated through correlation analysis with independent empirical data, including population density, points of interest (POIS), and registered enterprises. Both Spearman’s rho and Pearson’s r were calculated to assess both non-linear and linear relationships, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Validation results of the tested graph centralities. Note: Correlation coefficients represent averaged results across independent datasets. Both Spearman’s rho and Pearson’s rho were used to evaluate relationships.

Among the tested metrics, AP2GK and APGK showed the most balanced and consistently strong correlations across datasets, achieving average Spearman values of 0.51 and Pearson values of 0.45. The Len1000c indicator displayed the highest Spearman correlation overall, confirming its robustness in reflecting network reach within a 1 km radius. Indicators such as AP2PALL and the geometric mean of (Len + A2P) also performed well, but slightly weaker, as expected, since the geometric mean penalizes imbalances between length and integration. The lowest correlations were observed for NQPDE1000c, BtBE1000c, A2P, AP2, and MED1000c, indicating limited explanatory power. Ranking of the results is presented in Table 5.

Based on this comparative evaluation, HAP2GK was defined as the hull area divided by the perimeter squared and weighted by the area of buildings contributing to street culture, and was selected for further analysis. This indicator not only demonstrated good statistical performance but also higher sensitivity to the morphological structure of the urban fabric.

5. Results

5.1. Visibility and the Influence of Vegetation

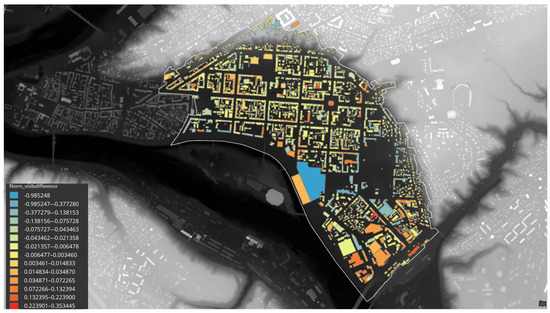

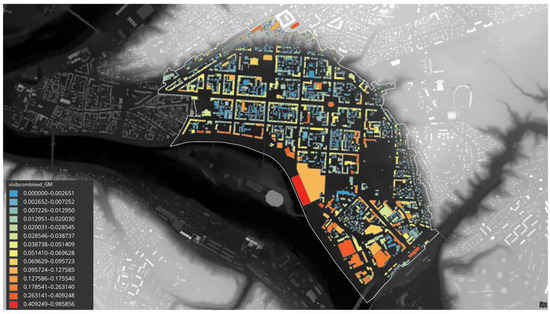

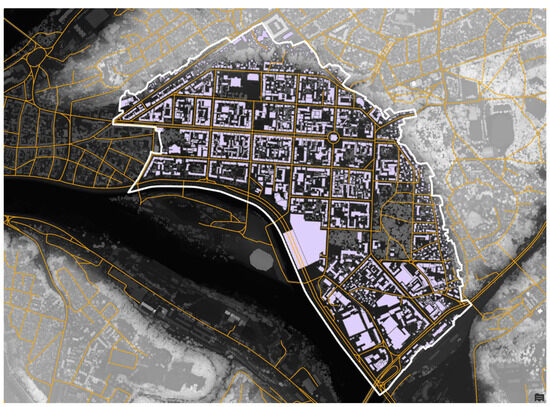

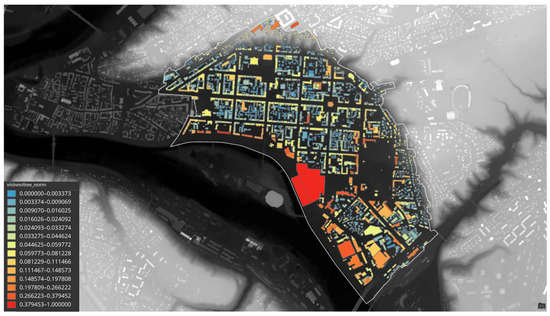

The analysis demonstrates that vegetation significantly influences the visibility of buildings within protected urban areas, moderating spatial perception and contributing to visual hierarchy (Table 6). Changes of the visibility indexes of buildings counted as the index without trees minus the index with trees is presented in Figure 1. The single combined visibility index presented in Figure 2. Across all object categories, the inclusion of trees led to a reduction in mean visibility values, confirming their screening effect. On average, mean normalized visibility decreased by approximately 17 percent when vegetation was included, while maximum visibility even increased slightly. This dual effect suggests that trees partially obscure general visibility but also enhance local focal points by framing certain views. It points out the potential significance of the greenery as a valuable feature of the protected urban area and as an important player of urban-architectural composition.

Table 6.

Comparison of visibility indicators by building category (with and without trees).

Figure 1.

Changes in the visibility index if situations without trees and with trees are compared. By authors.

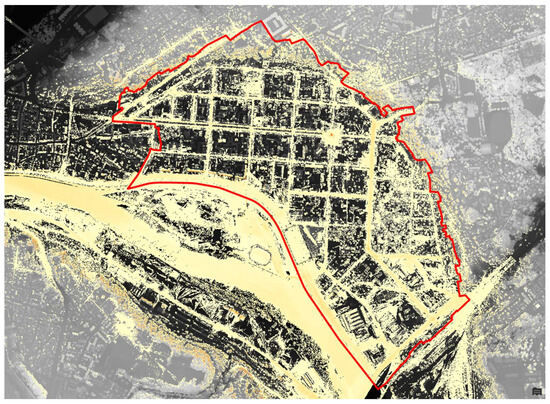

Figure 2.

The combined visibility index. By authors.

Cultural heritage objects (KPO) maintain the highest visibility across all categories with some competing KS objects. Although mean visibility slightly declines (from 0.0428 to 0.0397), the increase in maximum visibility (+0.062) indicates that heritage landmarks retain strong visual prominence. This stability aligns with their traditional placement in open or symbolically dominant urban positions.

Objects possessing valuable cultural heritage characteristics (VSPT) experience the most pronounced decline in mean visibility (−0.0063), suggesting higher sensitivity to vegetation occlusion. Despite this, their maximum visibility remains nearly unchanged, indicating that while greenery affects overall perception, key sightlines remain intact.

Urban-structure-forming objects (USFS) exhibit a balanced but contrasting response: their mean visibility decreases (−0.0056), yet their maximum visibility increases substantially (+0.074). This pattern implies that vegetation can simultaneously limit broad openness and accentuate focal architectural compositions, enhancing visual framing within the built fabric.

Other objects (KS) show the lowest overall visibility and irregular trends, partly due to normalization artifacts. Their average visibility (0.0184) and sharp maximum decline (−0.578) reflect enclosed, peripheral, or less significant visual roles. Despite this, some of the most significant visual dominants are formed by KS buildings, thus pointing out the fragility of the urban-architectural composition of the protected area, which could be affected even by a small number of new infill developments.

Overall, a consistent pattern emerges: cultural value correlates with visibility resilience. Heritage-related categories (KPO, VSPT) retain strong visual legibility in the northern part of New Town despite vegetation, whereas utilitarian or background elements (USFS, KS) experience stronger reductions. Vegetation thus reinforces urban hierarchy by enhancing contrast between prominent and subordinate spatial elements. It moderates visual exposure, preserves heritage distinctiveness, and contributes to perceptual balance between openness and enclosure. This outcome reveals the ecological and symbolic duality of trees as they provide environmental quality while shaping the legibility and experiential character of cultural urban landscapes. While the reduction of mean visibility values might initially appear to suggest a negative effect of vegetation on heritage perception, this interpretation would be incomplete. Trees and green spaces are not merely visual obstructions but active contributors to the experiential, environmental, and symbolic quality of protected urban areas. In many cases, the presence of vegetation enhances heritage appreciation by softening the built environment, framing significant viewpoints, creating seasonal variability, and improving microclimatic comfort. The increased maximum visibility observed for several categories illustrates precisely this effect: vegetation can heighten the legibility of key architectural elements by directing attention, producing contrast, and offering visual “breaks” that support orientation and atmosphere. Thus, rather than diminishing heritage value, greenery contributes to the lived quality of the area and shapes a more nuanced, layered visual experience. The analysis underscores that heritage visibility and vegetation should not be seen as competing interests; instead, they operate together to create a balanced urban landscape in which environmental quality and cultural identity reinforce one another.

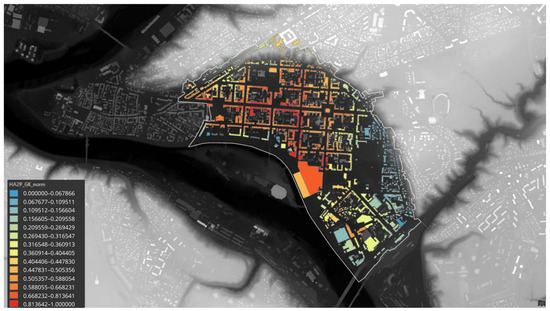

5.2. Comparison of Reachability by Building Groups

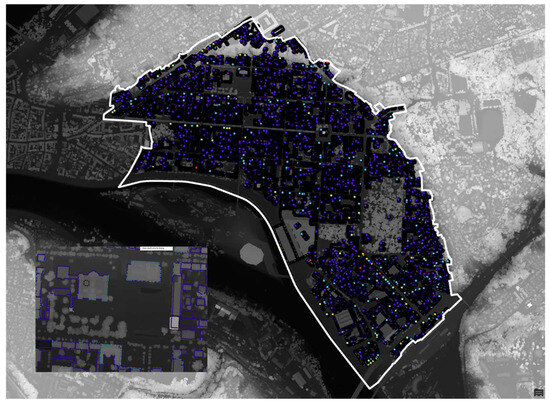

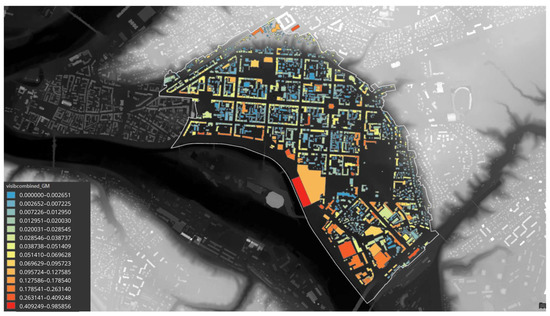

Visibility and reachability (Figure 3) values vary systematically across building categories (Table 7), reflecting differences in spatial prominence, functional integration, and morphological hierarchy within the protected urban area. The combined analysis reveals a consistent relationship between cultural significance and spatial centrality: buildings of higher cultural value tend to occupy more visually exposed and accessible positions, while other structures play supporting or peripheral roles in the urban fabric.

Figure 3.

The reachability index (HAP2GK) assigned to buildings. By authors.

Table 7.

Combined visibility and reachability by building category.

Cultural heritage objects (KPO) show the highest average values for both visibility (0.0395) and reachability (0.493), indicating their strong presence within both the visual and movement structure of the city. These sites occupy the most strategic positions, serving as focal points of accessibility and perception, which aligns with their symbolic and historical roles. Objects possessing valuable heritage characteristics (VSPT) also perform relatively well (visibility = 0.0256, reachability = 0.432), suggesting a transitional layer of cultural and spatial importance that bridges the heritage core with the broader urban fabric.

Urban-structure-forming objects (USFS) demonstrate moderate reachability (0.399) and visibility (0.0201), reflecting their role as structurally important yet less visually dominant elements that maintain network continuity rather than perceptual prominence. Other objects (KS) show the lowest average visibility (0.0178) and reachability (0.363), confirming their peripheral or enclosed position within the urban morphology.

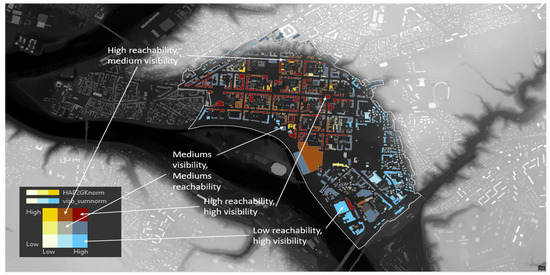

5.3. Interpretation of the Visibility-Reachability Matrix

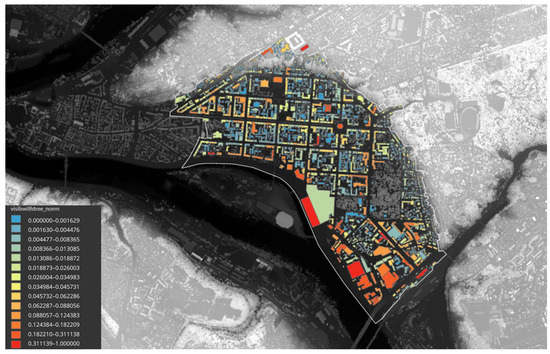

The bivariate matrix combining visibility and reachability (Figure 4) reveals distinct spatial logics within the protected area, linking visual prominence to functional accessibility. The combination of both indicators allows a nuanced differentiation between landmark prominence, everyday activity zones, and hidden or background urban fragments.

Figure 4.

The Matrix of Visibility and Reachability. By authors.

Areas with high visibility and high reachability correspond to the most legible and accessible parts of the urban fabric—typically central streets and squares where pedestrian flow and perceptual exposure coincide. These spaces act as urban landmarks and social anchors, supporting public activity and deserving priority in conservation and activation strategies.

In contrast, high-visibility but low-reachability zones represent iconic yet secluded sites—often heritage landmarks or visually striking buildings located in less permeable areas. While these objects contribute strongly to city imageability, improving physical or perceptual access (e.g., wayfinding, signage) would enhance their integration within the movement system.

Areas of low visibility but high reachability function as everyday hubs. Although less visually dominant, they remain spatially accessible and well connected, often accommodating daily services or local interactions. Design interventions here could focus on facade articulation, active ground-floor uses, or improved public-space quality to strengthen their social role.

Finally, low-visibility and low-reachability areas form latent or introverted spaces, frequently within internal courtyards or peripheral sectors. Their limited accessibility and perceptual presence suggest potential either for controlled redevelopment or deliberate preservation as quiet enclaves contributing to spatial diversity.

Together, these categories outline a multilayered urban hierarchy, where visibility and reachability jointly articulate the balance between legibility, accessibility, and functional differentiation across the historical urban landscape.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Findings of the Study

The integration of visibility and reachability analysis provides new insight into how the spatial configuration of protected urban areas reflects both perceptual and functional hierarchies. By linking the correlative and distributive situational codes, the study reveals how visual exposure and network accessibility jointly shape the legibility and cultural logic of the urban fabric. This dual approach extends heritage analysis beyond formal aesthetics, demonstrating that spatial prominence and accessibility often coincide with historical and symbolic significance.

The study demonstrates that the combined analysis of visibility and reachability offers a beneficial means of interpreting cultural heritage within its spatial context. The results confirm a strong correspondence between cultural importance and spatial centrality, showing that heritage prominence is both visual and functional. This quantitative framework not only enhances understanding of existing urban hierarchies but also serves as a predictive tool for evaluating future changes in protected areas. Further research should extend the method to other cities and explore integration with behavioral data, allowing for a deeper understanding of how spatial structure, perception, and cultural meaning interact in shaping sustainable and legible urban heritage environments.

To reinforce the interpretative value of the results, several quantitative patterns warrant explicit attention. The visibility analysis reveals measurable effect sizes across categories: mean visibility decreases with vegetation range from approximately −7% (VSPT) to −21% (USFS), while maximum visibility increases by up to +20% for some categories. This dual effect confirms that vegetation not only attenuates general exposure but also enhances focal visual hierarchies. Correspondingly, the reachability measures show that culturally significant buildings outperform non-heritage structures by 12–18% across most centrality indicators, quantitatively supporting the theoretical linkage between cultural value, visibility resilience, and spatial centrality.

6.2. Implications for Conservation and Planning

These quantitative patterns also highlight important implications for Lithuanian heritage policy. The existing system relies heavily on predefined visual protection zones and externally oriented corridors but lacks tools for evaluating internal visibility within the street network or understanding how daily movement shapes heritage perception. The findings demonstrate where formal protection aligns or misaligns with actual experiential prominence. For instance, while KPO objects maintain high visual and spatial centrality, VSPT buildings experience disproportionately high visibility loss from vegetation, indicating a vulnerability not currently addressed by regulation. This identifies specific categories where refined view management, selective pruning strategies, or micro-scale visibility corridors may be required.

From a heritage management perspective, the results highlight clear implications for conservation and planning. The combined indicators help to identify which buildings serve as landmarks, everyday connectors, or latent background elements within the city. Such differentiation supports more informed decisions about which areas to prioritize for conservation, adaptive reuse, or improved connectivity. Moreover, the approach provides a predictive tool capable of assessing how future changes, such as new construction, vegetation growth or decline, or changes in street structure, might alter the visibility and accessibility of culturally valuable sites. Integrating these insights into heritage management frameworks could help align protection boundaries and planning regulations with the actual experiential hierarchy of the urban environment.

Compared to traditional heritage evaluation methods, which typically rely on expert judgment, visual appraisal, or static panorama analysis, the presented approach offers a replicable, data-driven alternative. Quantitative modeling of visual and spatial relationships allows the identification of patterns that are often overlooked in qualitative assessments. However, this approach is not intended to replace expert-based interpretation but rather to complement it by providing measurable evidence of how spatial structure supports or constrains heritage perception and use.

6.3. Planning and Management Recommendations

By quantifying the visibility and reachability of heritage objects, particularly within internal urban views, planners can move beyond static zoning or abstract visual protection corridors toward more spatially grounded decision-making. The spatial exposure of heritage buildings in frequently used public routes suggests that visibility should be a weighted criterion in heritage evaluation, not merely as a visual attribute but as a proxy for cultural presence and experiential relevance. Municipalities could adopt such analytical methods to prioritize the conservation of buildings that serve as legible and accessible anchors within the urban fabric. For instance, adaptive reuse strategies or facade protection policies may be guided by the role of the building in shaping spatial legibility. Moreover, integrating reachability data into mobility planning allows authorities to enhance pedestrian infrastructure around key heritage zones, improving both their functional integration and symbolic centrality. These spatial indicators could also be used in participatory planning tools, helping stakeholders visualize how proposed interventions may reinforce or dilute the perceived value of heritage sites.

Moreover, combined visibility–reachability results offer actionable guidance for stakeholders. Heritage assets that score highly on both dimensions act as visual and functional anchors, suggesting priority zones for pedestrian improvements, adaptive reuse incentives, or facade preservation. Conversely, culturally important but spatially isolated buildings can be targeted for enhanced connectivity. These insights directly support municipal needs for evidence-based planning and reveal structural weaknesses in the current Lithuanian heritage protection system and specifically, its limited integration of experiential, movement-based, and internal visibility metrics. Integrating the presented indicators into planning practice would strengthen the proactive management of heritage values under urban change.

6.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

While the study introduces a novel methodological synthesis, it is not without limitations. Several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. The accuracy of visibility results depends on the resolution of the digital surface model and the completeness of vegetation data. The reachability measures are sensitive to the quality of street network data and normalization parameters. Moreover, the models capture potential accessibility and visibility rather than actual movement behavior or perceptual experience. These factors suggest the need for further validation through field observations or perception studies.

Moreover, it is necessary to mention that the approach primarily relies on spatial configuration and geometric visibility without incorporating real-time behavioral or perceptual data. This creates an opportunity for future research to combine Space Syntax metrics with empirical data sources such as pedestrian counts, eye-tracking, or user-generated spatial narratives. Second, while the study demonstrates the relevance of the method in a historical urban center, its scalability across different urban morphologies and cultural contexts remains to be tested. It might be stated that the proposed framework, based on visibility and reachability analysis grounded in Space Syntax theory, is inherently transferable to other urban contexts with a walkable street network and identifiable heritage assets, however, differences in planning regimes, heritage definitions, or street-network structures may affect the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, a more systematic exploration of how visibility and reachability relate to residents’ emotional attachment, identity formation, or usage frequency would strengthen the linkage to heritage theory. Developing composite indices that combine spatial exposure with cultural significance metrics may offer planners a holistic tool for prioritizing interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z.; methodology, K.Z.; software, K.Z. and M.I.; validation, K.Z.; formal analysis, K.Z., I.G.-V. and A.M.; investigation, K.Z., I.G.-V., A.M. and M.I.; resources, K.Z., I.G.-V., A.M. and M.I.; data curation, K.Z. and M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z., I.G.-V. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, K.Z., I.G.-V., A.M. and M.I.; visualization, K.Z. and M.I.; supervision, K.Z.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage and Global Change under the project Heritage in Depopulated European Areas (HerInDep). This research was funded by Lithuanian Research Council, grant number Project No. S-JPIKP-23-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results can be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT 5.1 for the purposes of the language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Visibility Analysis Procedure Steps

Figure A1.

Raster surface data with building polygons and walking paths and streets added. White line represents the boundary of the investigated area.

Figure A2.

Generated observation points (shown in green) with 10 m step along all streets inside of the investigated area and some streets outside of it from which the area is visible.

Figure A3.

Viewshed analysis results presented as the areas visible from observation points (yellow) and boundary of the investigated are (in red). Viewshed analysis was made on both rasters: with trees and without trees.

Figure A4.

Points generated within 1 m step around each building polygon (shown in green).

Figure A5.

Visibility is the number of points from which each point of the facade is visible based on spatial join analysis of GIS. Viewshed analysis was made on both rasters: with trees and without trees.

Figure A6.

Visibility of buildings as a sum of visibilities of the facade points normalized while dividing by maximal value based on the raster with tree canopies.

Figure A7.

Visibility of buildings as a sum of visibilities of the facade points normalized while dividing by maximal value based on the raster without tree canopies.

Figure A8.

Combined visibility with trees and without trees calculated as the geometric mean of both values for each building.

References

- Law of the Republic of Lithuania on the Protection of Immovable Cultural Heritage, Consolidated Version from 1 October 2025. Available online: https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.9BC8AEE9D9F8/asr (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Modernist Kaunas: Architecture of Optimism, 1919–1939. World Heritage Centre. 2025. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1661/#:~:text=This%20property%20testifies%20to%20the,architectural%20expression%20in%20the%20city (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Hakim, B.S. Julian of Ascalon’s treatise of construction and design rules from sixth-century Palestine. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 2001, 60, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrušonis, V. Vietos Dvasia (Genius Loci) ir Jos apraiškų Respektavimas. Respect for the Spirit of Place (Genius Loci) and Its Manifestations. Virtualus Architektūros Muziejus. 2018. Available online: http://archmuziejus.lt/lt/vietos-dvasia-genius-loci-ir-jos-apraisku-respektavimas/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Petrušonis, V. Regulation of high-rise construction in the city. Urban Archit. 2005, 29, 74–75. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar]

- Zaleckis, K. Sketch for a hypothetic prototype of contemporary megapolis townscape. Town Plan. Archit. 2007, 31, 75–86. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.G.; Meyer, M.E. Environmental reviews and case studies: The national park service visual resource inventory: Capturing the historic and cultural values of scenic views. Environ. Pract. 2016, 18, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.A.; Sim, J.; Powell, L.; Crump, L. Scenic assessment methodology for preserving scenic viewsheds of Virginia, USA. Land 2024, 13, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Bishop, I.; Hossain, H.; Sposito, V. Using GIS in Landscape Visual Quality Assessment. Appl. GIS 2007, 3, 18.1–18.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukwai, J.; Mishima, N.; Srinurak, N. Identifying visual sensitive areas: An evaluation of view corridors to support nature-culture heritage conservation in Chiang Mai historic city. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]