Accessibility and Spatial Conditions in Northern Italian Metropolitan Areas: Considerations for Governance After Ten Years of Metropolitan Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theorical and Policy Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Selection of the Territorial Area of Investigation

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Metropolitan Cities

3.2.1. Morphological and Settlement Characteristics

- Territorial extent;

- Resident population and population density;

- Demographic trends (2015–2025);

- Number of municipalities;

- Number of “small municipalities” (resident population of up to 5000 inhabitants, Art. 1, para. 2, Law 158/2017) [35];

- Classification of municipalities by altitude zones;

- Territorial extent of the core city and its share within the metropolitan context;

- Population residing in the core city and its share within the metropolitan population.

3.2.2. Accessibility Analysis

3.3. Case Study

4. Results

4.1. Findings from the Comparative Analysis

4.1.1. Results: Morphological and Settlement Characteristics

4.1.2. Results: Accessibility Analysis

4.1.3. Influence of Land Use and Morphology on Accessibility Patterns

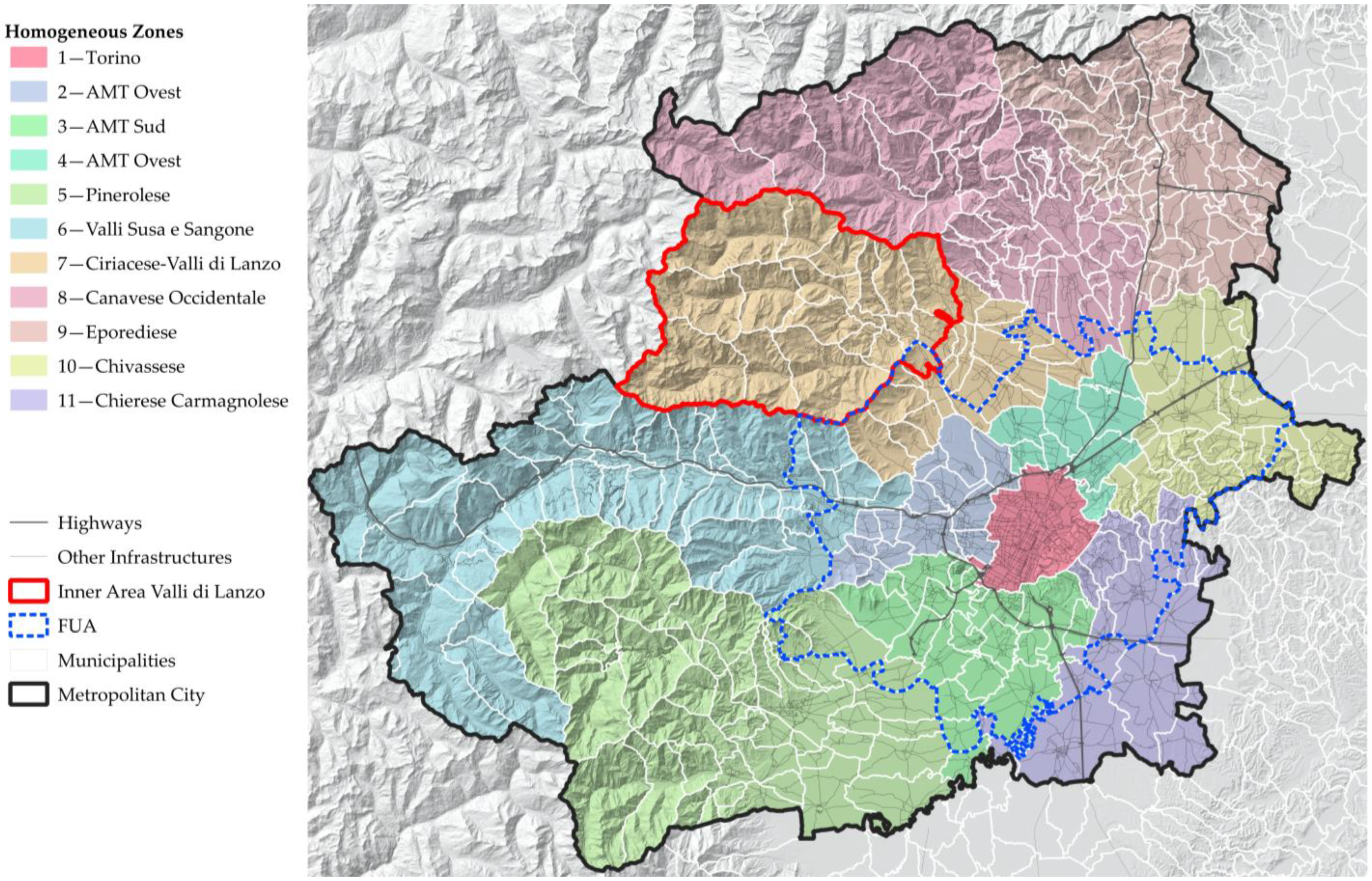

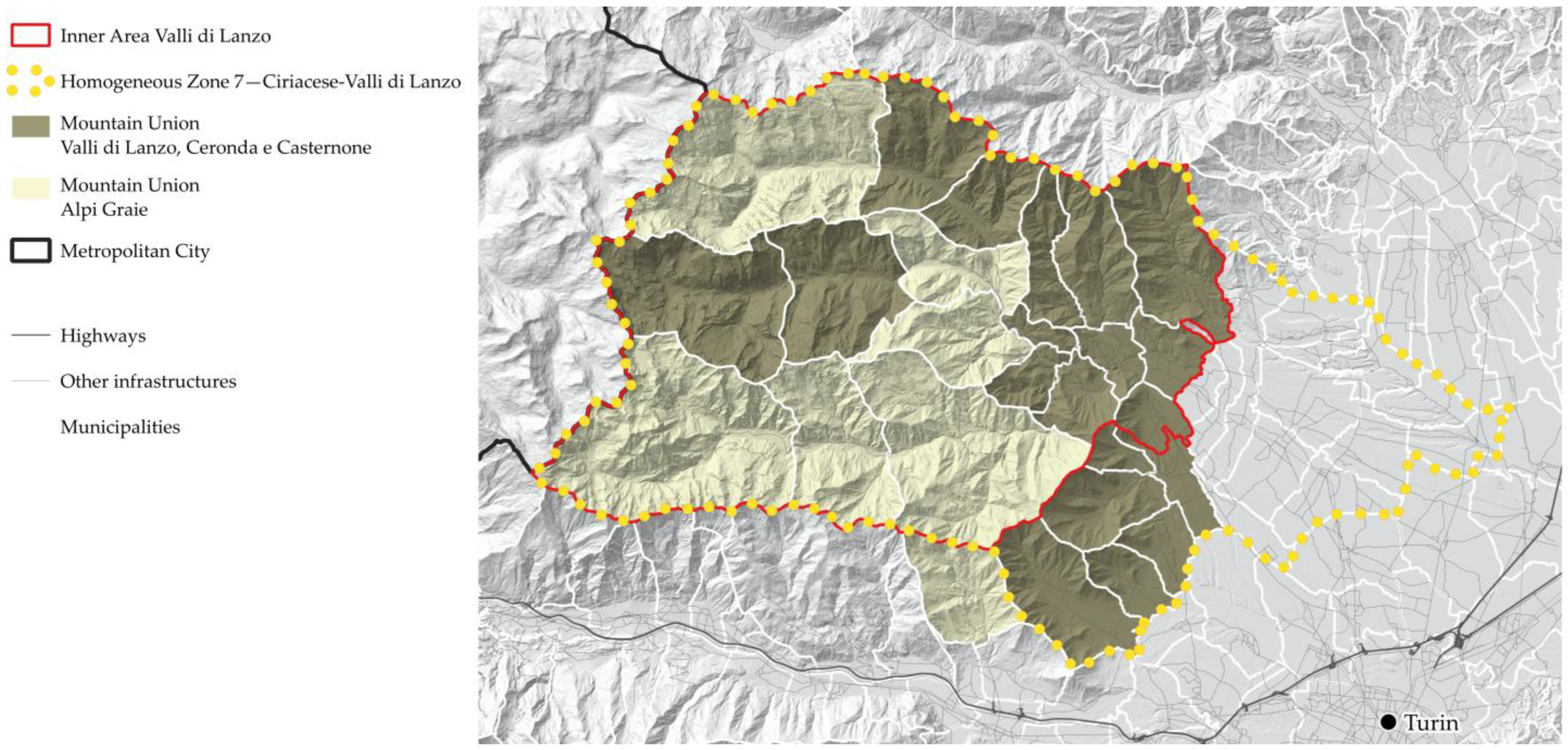

4.2. Focus on the Metropolitan City of Turin

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FUA | Functional Urban Area |

| GTMP | General Territorial Metropolitan Plan |

| HZ | Homogeneous Zones |

| LULC | Land Use-Land Cover |

| MC | Metropolitan City |

| MCTo | Metropolitan City of Turin |

| MCMi | Metropolitan City of Milan |

| MCVe | Metropolitan City of Venice |

| MSP | Metropolitan Strategic Plan |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PNRR | Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Italy) |

| SNAI | Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne (National Strategy for Inner Areas, Italy) |

| SUMP | Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan |

References

- Casavola, D.; Cotella, G.; Janin Rivolin, U.; Vitale Brovarone, E. Metropolitan governance in Europe: A classification of current national models. disP Plan. Rev. 2025, 61, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law No. 56 of 7 April 2014. Disposizioni Sulle Città Metropolitane, Sulle Province, Sulle Unioni e Fusioni di Comuni. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/2014_0056.htm (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Mascarucci, R. Città Medie e Metropoli Regionali; INU Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, F.; Bruzzone, F.; Nocera, S. Effects of high-speed rail on regional accessibility. Transportation 2023, 50, 1685–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá Marques, T.; Saraiva, M.; Ribeiro, D.; Amante, A.; Silva, D.; Melo, P. Accessibility to services of general interest in polycentric urban system planning: The case of Portugal. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 1068–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. Pensare lo Spazio Urbano Senza Più Esterno. IC Imprese Città 2015, 6, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres-Merino, J.; Coloma, J.F.; García, M.; Monzon, A. The Unsustainable Proximity Paradox in Medium-Sized Cities: A Qualitative Study on User Perceptions of Mobility Policies. Land 2025, 14, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, A. City-Effect: New Centralities in Post-pandemic Regional Metropolis Pescara-Chieti. In Urban and Transit Planning, Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation, 3rd ed.; Alberti, F., Matamanda, A.R., He, B., Galderisi, A., Smol, M., Gallo, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Der kosmopolitische Blick Oder: Krieg ist Frieden; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Abitare la Prossimità: Idee Per la Città Dei 15 Minuti; Egea: Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Transport Forum (ITF). Sustainable Accessibility for All; ITF Research Reports; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, B.; Rokicka, B.; Stępniak, M. Major transport Infrastructure Investment and Regional Economic Development–an Accessibility-based Approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 72, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Transport Forum (ITF). Benchmarking Accessibility in Cities. Measuring the Impact of Proximity and Transport Performance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/accessibility-proximity-transport-performance_2.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hansen, W.G. How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. J. Am. Plan. Inst. 1959, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straatemeier, T. How to Plan for Regional Accessibility? Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Territorial Agenda 2030–A Future for All Places, 2020. Available online: https://territorialagenda.eu/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- European Union, Urban Agenda for the EU ‘Pact of Amsterdam’ Agreed at the Informal Meeting of EU Ministers Responsible forUrban Matters on 30 May 2016 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/urban-development/agenda/pact-of-amsterdam.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Urban Agenda for EU. Ljubljana Agreement. Informal Meeting of Ministers Responsible for Urban Matters26 November 2021 Brdo pri Kranju, Slovenia, 2021. Available online: https://www.urbanagenda.urban-initiative.eu/sites/default/files/2022-10/ljubljana_agreement_2021_en.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hinchcliff, C.; Taylor, I. Every Village, Every Hour: A Comprehensive Bus Network for Rural England; CPRE: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://www.cpre.org.uk/resources/every-village-every-hour-2021-buses-report-full-report/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- International Transport Forum (ITF). The Innovative Mobility Landscape: The Case of Mobility as a Service, International Transport Forum Policy Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Volume 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, G.C. Dalle Leggende Alle Città Metropolitane. Difficile Attuazione di Un’istituzione del Governo del Territorio tra Passato, Presente e Futuro. In La Riorganizzazione Territoriale e Funzionale Dell’area Vasta. Riflessioni Teoriche, Esperienze e Proposte Applicative a Partire Dal Caso Della Regione Lombardia; Ricciardi, G.C., Venturi, A., Eds.; G. Giappichelli Editore: Torino, Italy, 2018; pp. 29–86. Available online: https://osservatorioautonomie.unipv.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/5_Ricciardi_Venturi_Area-vasta-2018.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Palermo, A.; Tucci, G.; Chieffallo, L. Definition of Spatio-Temporal Levels of Accessibility. Isochronous Analysis of Regional Transport Networks. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2025, 18, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Per la Coesione Territoriale. PON Città Metropolitane. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/pon/pon-metro/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Dipartimento Per le Politiche di Coesione e il Sud. PON Città Metropolitane 2014–2020. Available online: https://www.pnmetroplus.it/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Spinedi, M. Mobilità Nelle e Per le Città Metropolitane: Temi e Problemi. Working Papers. Rivista Online di Urban@it 2015, 1. Available online: https://www.urbanit.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/BP_A_Spinedi.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Cascetta, E.; Cartenì, I.; Henke, E.; Pagliara, F. Economic growth, transport accessibility and regional equity impacts of high-speed railways in Italy: Ten years ex post evaluation and future perspectives. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 139, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. High-speed rail services development and regional accessibility restructuring in megaregions: A case of the Yangtze River Delta, China. Transp. Policy 2018, 72, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarucci, R. Sistema urbano intermedio e aree montane. In Urbano Montano. Verso Nuove Configurazioni e Progetti di Territorio; Corrado, F., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2021; pp. 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. Strategia Nazionale Per le Aree Interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance, Accordo di Partenariato 2014–2020; Ministero Dello Sviluppo Economico, Dipartimento Per lo Sviluppo e la Coesione Economica, Unità di Valutazione Degli Investimenti Pubblici: Rome, Italy, 2014. Available online: https://www.mim.gov.it/documents/20182/890263/strategia_nazionale_aree_interne.pdf/d10fc111-65c0-4acd-b253-63efae626b19 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri. Dipartimento Per le politiche di Coesione e Per il Sud. Piano Strategico Nazionale Delle Aree Interne. 2025. Available online: https://politichecoesione.governo.it/media/jhld12qn/psnai_finale_30072025_clean_ministro.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le Aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Servillo, L.; Russo, A.P.; Barbera, F.; Carrosio, G. Inner Peripheries: Towards an EU place-based agenda on territorial peripherality. IJPP Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2016, 6, 42–75. Available online: https://arts.units.it/retrieve/e2913fdb-e4af-f688-e053-3705fe0a67e0/2016%20Servillo%20Russo%20Barbera%20Carrosio%20Journal%20Planning.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Barbera, F.; De Rossi, A. Metromontagna. Un Progetto Per Riabitare l’Italia; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Law No. 158 of 6 October 2017. Misure Per il Sostegno e la Valorizzazione Dei Piccoli Comuni, Nonchè Disposizioni Per la Riqualificazione e il Recupero Dei Centri Storici Dei Medesimi Comuni. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:2017-10-06;158~art1-com2 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Demography in Figures. Available online: https://demo.istat.it/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Italian Statistical Yearbook 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ASI_2024.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H.; Veneri, P. The EU-OECD Definition of a Functional Urban Area; OECD Regional Development Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Boundaries of Functional Urban Areas (Spatial Data). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/oecd-definition-of-cities-and-functional-urban-areas.html (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- OECD. Population by Age and Sex—Cities and FUAs. 2024. Available online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?fs[0]=Topic%2C1%7CRegional%252C%20rural%20and%20urban%20development%23GEO%23%7CCities%20and%20functional%20urban%20areas%23GEO_URB%23&pg=0&fc=Topic&bp=true&snb=23&vw=ov&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_FUA_DEMO%40DF_AGE_SEX&df[ag]=OECD.CFE.EDS&df[vs]=1.1&dq=.A..._T._T..&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&pd=2024%2C2024 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- OECD. Local Administrative Units—Cities and FUAs. 2024. Available online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?fs[0]=Topic%2C1%7CRegional%252C%20rural%20and%20urban%20development%23GEO%23%7CCities%20and%20functional%20urban%20areas%23GEO_URB%23&pg=0&fc=Topic&bp=true&snb=28&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_FUA_TERR%40DF_LAU&df[ag]=OECD.CFE.EDS&df[vs]=1.1&dq=.A.LAU_C..&pd=2024%2C2024&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service; European Environment Agency. Corine Land Cover (CLC) Backbone. 2023. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/clc-backbone (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Geurs, K.T.; van Wee, B. Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosik, P.; Stępniak, M.; Komornicki, T. The decade of the big push to roads in Poland: Impact on improvement in accessibility and territorial cohesion from a policy perspective. Transp. Policy 2015, 37, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turri, E. La Megalopoli Padana; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, B.; Zullo, F. Half a Century of Urbanization in Southern European Lowlands: A Study on the Po Valley (Northern Italy). Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 9, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan City of Turin. Metropolitan Strategic Plan 2024–2026. English Version 2024. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.torino.it/sites/default/files/pagina/qa7/PSM/piano_strategico_metropolitano_2024-2026_eng.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Metropolitan City of Turin. StaTÒmetro—La Città Metropolitana di Torino in Numeri. 2024. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYzgzZjMyZTgtMjhhZC00ZDJhLWE0YWMtODIwZTY4ZDBlODQ2IiwidCI6IjA4M2IzZjU2LWVhYzQtNDM0Mi1hNDk5LWI5MDBkNTMxMDkyMyIsImMiOjh9 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Buonomo, A.; Benassi, F.; Gallo, G.; Salvati, L.; Strozza, S. In-between centers and suburbs? Increasing differentials in recent demographic dynamics of Italian metropolitan cities. Genus 2024, 80, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriani, S.; Calzavara, A. Una valutazione critica sull’implementazione della legge 56 in Veneto: Il caso della Città metropolitana di Venezia. Geotema 2022, 70, 56–64. Available online: https://www.ageiweb.it/geotema/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/GEOTEMA-70.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Fondazione di Venezia. Quattro Venezie Per un Nordest. Rapporto su Venezia Civitas Metropolitana; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cristaldi, F. Commuting and gender in Italy: A methodological issue. Prof. Geogr. 2005, 57, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, F.; Dematteis, G.; Durbiano, E.; Gioia, D. The Mountain–City Exchange: The Case of the Metropolitan City of Turin; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dematteis, G. The Alpine Metropolitan–Mountain Faced with Global Challenges: Reflections on the Case of Turin. J. Alp. Res. Rev. De Géographie Alp. 2018, 106, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.A.; Giaimo, C. The Metropolitan City as a New Institution for Planning. In La Città Metropolitana di Torino e il Ruolo di Una Nuova Pianificazione; Barbieri, C.A., Giaimo, C., Voghera, A., Eds.; Urbanistica Dossier Online, INU Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 28, pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vetritto, G. L’Italia da rammendare. Legge Delrio e ridisegno del sistema delle autonomie. Riv. Giuridica Del Mezzog. 2016, 1, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan City of Turin. Piano Territoriale Generale Metropolitano—Progetto Preliminare/Metropolitan General Territorial Plan—Preliminary Draft. Relazione Illustrativa. 2022. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.torino.it/sites/default/files/pagina/allegati/Territorio/ptgm/ProgPrel/pdf/A_Relazione_illustrativa_PP.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Ahrend, R.; Gamper, C.; Schumann, A. The OECD Metropolitan Governance Survey: A Quantitative Description of Governance Structures in Large Urban Agglomerations; OECD Regional Development Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwiaczonek, K. Metropolisation Through Institutional Action: An Analysis of Seven Metropolitan Areas in Central Europe. Stud. Socjol. 2025, 2, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, I. Governing the Metropolitan Dimension: A Critical Perspective on Institutional Reshaping and Planning Innovation in Italy. Eur. J. Spat. Dev. 2019, 70, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, G. Planning Assignments of the Italian Metropolitan Cities: Early Trends. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2017, 10, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.A. Un nuovo modo di pianificare il territorio metropolitano. In La Città Metropolitana di Torino e il Ruolo di Una Nuova Pianificazione; Barbieri, C.A., Giaimo, C., Voghera, A., Eds.; Urbanistica Dossier Online, INU Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 28, pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mortari, I.; Boggio Merlo, P.; Fiora, G. Città metropolitana di Torino: Gli strumenti della pianificazione territoriale e strategica fra rigenerazione urbana e sviluppo territoriale. Urban. Inf. 2023, 317, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.A. Dall’istituzione all’azione della Città metropolitana di Torino: Il ruolo di una nuova pianificazione. Il Piemonte Delle Auton. 2015, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolitan City of Turin. Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provinciale 2/Provincial Territorial Coordination Plan 2. Relazione Illustrativa. 2011. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.torino.it/sites/default/files/pagina/allegati/Territorio/Pian_Area_Vasta/ptc2/PTC2_Rel_ill_dcr121_2011.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Piedmont Region. Strategia Per le Valli di Lanzo: La Montagna si Avvicina. 2020. Available online: https://www.unionemontanavlcc.it/portals/1708/SiscomArchivio/8/Strategia_SNAI_Lanzo.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Metropolitan City of Turin Piano Urbano Della Mobilità Sostenibile/Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan. Rapporto Finale 2022. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.torino.it/sites/default/files/pagina/allegati/trasporti/PUMS/RAPPORTO%20FINALE/PUMS_RapportoFinale.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Giacomino, G. Lanzo Hospital in Chaos Between Resignations and Closures. La Stampa. 23 February 2025. Available online: https://www.lastampa.it/torino/2025/02/23/news/ospedale_lanzo_dimissioni_chiusure-15018325/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Regione Piemonte. Piano Territoriale Regionale. Variante di Aggiornamento Adottata. Schede degli Ambiti di Integrazione Territoriale, 2024. Available online: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/sites/default/files/media/documenti/2024-06/3_schede_ait.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Metropolitan City of Turin. Statuto Metropolitano. Approved by the Metropolitan Conference on 14 April 2015, Amended by Resolution No. 3/2023 of 14 February 2023. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.torino.it/sites/default/files/pagina/a02/consiglio/statuto/statuto_2023.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Giaimo, C.; Pantaloni, G.G. Oltre i confini delle Zone omogenee: Vocazione ecosistemica e rigenerazione urbano-territoriale nella Città metropolitana di Torino. In La Città Metropolitana di Torino e il Ruolo di Una Nuova Pianificazione; Barbieri, C.A., Giaimo, C., Voghera, A., Eds.; Urbanistica Dossier Online, INU Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 28, pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Giannino, C. Dieci anni dopo la nascita delle città metropolitane. Quale contributo offerto ai processi di sviluppo urbano? Urban. Inf. 2024, 317, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J. Metropolitan Governance: A Framework for Capacity Assessment; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat); GIZ: Bonn and Eschborn, Germany, 2018. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/giz2018-0191en-metropolitan-governance-framework-capacity-assessment.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- ESPON. METRO: The Role and Future Perspectives of Cohesion Policy in the Planning of Metropolitan Areas and Cities. Annex III—Metropolitan City of Turin Case Study; Cotella, G., Vitale Brovarone, E., Staricco, L., Casavola, D., Eds.; Politecnico di Torino: Turin, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tubertini, C. Nuove dinamiche territoriali e logiche metropolitane: Spunti per le città medie e le aree interne. Ist. Del Fed. 2016, 4, 857–865. [Google Scholar]

- Urbani, P. Città metropolitane: Un difficile bilancio positivo. Urban. Inf. 2024, 317, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, P. Strategie Per le Aree Interne: Tra Retorica del Declino e Infrastrutturazione Comunitaria. DiTe. 15 July 2025. Available online: https://www.dite-aisre.it/strategie-per-le-aree-interne-tra-retorica-del-declino-e-infrastrutturazione-comunitaria/?utm_source=DiTe+newsletter&utm_campaign=7610721d3d-17_luglio_2025&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-c731c5715a-672480233 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Mobilio, G. Le Città metropolitane a dieci anni dalla loro istituzione. Spunti per un bilancio. Ital. Pap. Fed. 2024, 1, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | MCTo | MCMi | MCVe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area (km2) | 6828 | 1574 | 2477 |

| Population 2025 (inh.) | 2,207,873 | 3,247,623 | 833,934 |

| Population density (inh./km2) | 323 | 2063 | 333 |

| Population trend 2015–2025 (inh. & %) | −74,324 (−3.26%) | +39,114 (+1.22%) | −21,762 (−2.54%) |

| Municipalities (n) | 312 | 133 | 44 |

| Number of ‘small municipalities’ (n) | 105 mountainous 124 hilly 83 plains | All plains | All plains |

| Surface area of the core city (km2) | 130 | 182 | 415.5 |

| Population of the core city 2025 (inh.) | 856,745 | 1,366,155 | 249,466 |

| Surface core city/MC (%) | 2% | 12% | 17% |

| Population core city/MC (%) | 39% | 42% | 30% |

| Indicator | Turin | Milan | Venice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area (km2) | 1702 | 3841 | 670 |

| Population 2024 (inh.) | 1,707,875 | 4,981,421 | 545,623 |

| Municipalities (n) | 89 | 303 | 15 |

| Land Use Land Cover Classes | MCTo Surface Area (%) | MCMi Surface Area (%) | MCVe Surface Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Sealed | 7.4% | 30.8% | 10.3% |

| 2—Woody needle leaved trees | 8.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| 3—Woody broadleaved deciduous trees | 28.0% | 11.4% | 3.3% |

| 4—Woody broadleaved evergreen trees | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.3% |

| 5—Low-growing woody plants | 1.9% | 0.7% | 5.9% |

| 6—Permanent herbaceous | 29.4% | 20.7% | 15.6% |

| 7—Periodically herbaceous | 15.3% | 33.9% | 43.3% |

| 8—Lichens and mosses | 0.0% | 0% | 0.0% |

| 9—Non- and sparsely vegetated | 8.8% | 0.9% | 0.8% |

| 10—Water | 0.8% | 1.2% | 20.1% |

| 11—Snow and ice | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitulano, V.; Pantaloni, G.G.; Bocca, A.; Bruzzone, F. Accessibility and Spatial Conditions in Northern Italian Metropolitan Areas: Considerations for Governance After Ten Years of Metropolitan Cities. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120526

Vitulano V, Pantaloni GG, Bocca A, Bruzzone F. Accessibility and Spatial Conditions in Northern Italian Metropolitan Areas: Considerations for Governance After Ten Years of Metropolitan Cities. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):526. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120526

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitulano, Valeria, Giulio Gabriele Pantaloni, Antonio Bocca, and Francesco Bruzzone. 2025. "Accessibility and Spatial Conditions in Northern Italian Metropolitan Areas: Considerations for Governance After Ten Years of Metropolitan Cities" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120526

APA StyleVitulano, V., Pantaloni, G. G., Bocca, A., & Bruzzone, F. (2025). Accessibility and Spatial Conditions in Northern Italian Metropolitan Areas: Considerations for Governance After Ten Years of Metropolitan Cities. Urban Science, 9(12), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120526