Abstract

Promoting and increasing sustainable mobility has become more of a focus in transport and mobility policies and plans. However, challenges remain in its implementation in low-density urban areas, which are usually highly dependent on private motorised transport. This study investigates how local actors and citizens in a low-density suburban area perceive the main mobility challenges and opportunities, contributing empirical evidence on how collaborative planning operationalises accessibility-oriented mobility models in low-density suburban territories, an under-researched context in sustainable mobility. It also examines how co-creation processes contribute to identifying barriers and priorities and to what extent proximity-based concepts such as the 15-Minute City, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) can be reinterpreted for low-density suburban realities. The methodological approach involved three focus groups with local actors and citizens to identify barriers, priorities, and strategies through collective discussion and co-creation. This process resulted in an agreement on eight (8) co-created strategies, revealing convergence towards promoting active modes and public transport and emphasising that accessibility depends on territorial redesign, digital integration, and inclusive governance. The findings contribute to the empirical evidence that participatory and context-sensitive approaches can enable sustainable mobility transitions in suburban areas by efficiently meeting people’s needs and aspirations.

1. Introduction

The long-standing reliance on private motorised transport in low-density suburban areas, characterised by dispersed settlement patterns and limited public transport access, remains a significant challenge to achieving sustainable and equitable mobility [1]. These conditions reinforce spatial fragmentation and intensify social exclusion, especially among populations without access to private vehicles, such as low-income and ageing groups [2,3,4]. Moreover, private motorised mobility in these territories contributes disproportionately to transport energy consumption, air pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions, intensifying environmental pressures [5,6,7]. Sustainable mobility debates increasingly recognise that these challenges are structural in suburban contexts and require integrated territorial responses rather than isolated transport improvements [2,8,9].

While collaborative and participatory planning practices have been widely developed across different international contexts [10,11,12]. Their application to low-density suburban contexts remains uneven and context-dependent. Previous studies have demonstrated the value of participatory approaches in revealing everyday mobility experiences and place-based meanings [13], negotiating proximity and accessibility in planning processes [14], or combining participatory inputs with multi-criteria and decision-support methods. Existing studies tend to address either participatory processes in urban centres or accessibility challenges in suburban areas, with few integrating both dimensions. Rather than claiming a methodological gap, this situation highlights the need for further empirical research examining how co-creation approaches can inform accessibility-oriented mobility strategies in a low-density suburban context [11,15].

Over recent decades, the concept of sustainable mobility has evolved from a transport-oriented logic to a multidimensional framework centred on accessibility, equity, and environmental responsibility [16,17]. Policies have gradually shifted towards proximity-based approaches, promoting multimodal integration and the reorganisation of urban systems so that active or collective modes can reach daily needs [2,18]. In this perspective, mobility is framed as a social right embedded in urban space rather than solely a matter of efficiency [17,19]. Three conceptual paradigms capture this evolution: the 15-Minute City, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), and Mobility as a Service (MaaS). Respectively, these approaches emphasise spatial proximity to daily services [20], the integration of land use and public transport [21], and the digital integration of transport services to improve accessibility [22]. In this study, these paradigms are used as analytical lenses rather than prescriptive planning models to empirically examine how their core principles are reinterpreted by local actors in low-density suburban contexts. Although they all promote accessibility through spatial, functional, and digital integration, their implementation in low-density suburban areas remains complex due to limited density, poor connectivity, and fragmented governance [23,24]. In such contexts, TOD must be reinterpreted through a functional accessibility lens, focusing on strategic nodes, mobility corridors, and minimum public transport service levels, and prioritising access conditions over morphological intensity.

In this study, low-density suburban peripheries are defined as territories characterised by dispersed land-use patterns, fragmented service provision, and firm reliance on private motorised transport, conditions typical of medium-sized Southern European cities [23]. Adapting proximity-based models to such contexts requires functional rather than morphological transformation, aligning dispersed structures with service accessibility through coordinated spatial and digital strategies [19,25]. Building sustainable suburban mobility, therefore, depends on strengthening intermodality, improving access to essential services, and reinforcing governance mechanisms capable of cross-institutional cooperation [11,26].

Co-creation and collaborative planning techniques are particularly relevant in these environments, where traditional top-down planning tools often fail to capture local challenges and behavioural dynamics. In low-density suburban contexts, mobility practices are strongly shaped by spatial dispersion, high reliance on private motorised vehicles, and fragmented territorial structures, making everyday accessibility constraints highly context-specific and difficult to address through standardised mobility solutions [15,27,28]. By enabling interaction and collective reflection, focus groups are particularly suitable for eliciting lived mobility experiences, identifying shared problems and divergences and supporting the co-production of context-sensitive strategies in complex suburban settings [10,11]. These methods are especially valuable in fragmented suburban settings, where understanding lived experiences is crucial for designing feasible mobility strategies.

Coimbra provides a suitable case for examining these dynamics. As a medium-sized Southern European city, it exhibits marked contrasts between its compact historic core and its dispersed suburban peripheries. São Martinho do Bispo reflects typical challenges of low-density areas, car dependency, weak multimodal integration, and significant institutional fragmentation. The ENTROPY project [29] offers an integrated framework for analysing these issues by combining co-creation methodologies with collaborative mobility planning in medium-sized cities.

Within the broader ENTROPY project, the present study represents a specific empirical stage focused on exploring suburban mobility challenges through participatory approaches. Earlier project activities contributed to framing key analytical dimensions related to accessibility, proximity, and governance in medium-sized cities. On this basis, the focus groups conducted in this study deepen the understanding of local mobility practices and directly inform the research questions addressed.

Within this context, and building on the insights generated through the focus groups, the study is guided by the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1: How do local institutional, technical, and citizen actors perceive the main mobility challenges and accessibility constraints in a low-density suburban area?

- RQ2: How can co-creation processes, based on focus group discussions, contribute to the identification of barriers, priorities, and context-sensitive mobility strategies in low-density suburban contexts?

- RQ3: To what extent can proximity-based mobility models, such as the 15-Minute City, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), and Mobility as a Service (MaaS), be reinterpreted to inform sustainable mobility transitions in low-density suburban realities?

By addressing these research questions, the study aims to co-produce mobility strategies with institutional and citizen stakeholders and to explore how collaborative planning can support accessibility-oriented mobility transitions in suburban contexts.

Methodologically, the research employs three focus groups involving institutional, technical, and citizen actors, followed by qualitative coding and co-occurrence analysis, enabling a multi-actor understanding of mobility challenges while generating empirically grounded strategies. Overall, the study demonstrates how participatory and context-sensitive approaches can operationalise sustainable mobility transitions in low-density suburban areas, offering insights relevant to medium-sized cities across Europe.

This paper contributes to existing literature in three main ways:

- It provides empirical evidence from a low-density suburban area within a medium-sized European city, a context that remains underrepresented in sustainable mobility research.

- It integrates participatory planning approaches with accessibility-oriented mobility paradigms, bridging collaborative governance frameworks with spatial and transport planning theories.

- It combines focus group methodologies with qualitative co-occurrence analysis, offering a robust mixed qualitative approach to capture both deliberative processes and structured thematic relationships among mobility dimensions.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the research design, case study, and methodological approach based on focus groups and qualitative analysis. Section 3 presents and discusses the results of the participatory process and co-occurrence analysis. Finally, Section 4 summarises the main conclusions, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative and exploratory design grounded in collaborative and communicative planning principles [10,11,30]. The methodological approach follows the framework developed within the ENTROPY project [29], which applies co-creation and multi-actor engagement tools to support the transferability of participatory mobility planning processes across medium-sized European cities. In this context, the research combines participatory focus group discussions with qualitative coding and co-occurrence analysis, seeking to understand how citizens, institutions, and private actors co-design mobility strategies in suburban environments.

Within this design, the methodological phases were structured to address the study’s research questions directly: the focus group sessions primarily inform RQ1 and RQ2 by capturing actors’ perceptions, priorities, and co-created strategies, while the qualitative coding and co-occurrence analysis support RQ2 and RQ3 by identifying thematic relationships and assessing how proximity-based mobility concepts can be reinterpreted in a low-density suburban context.

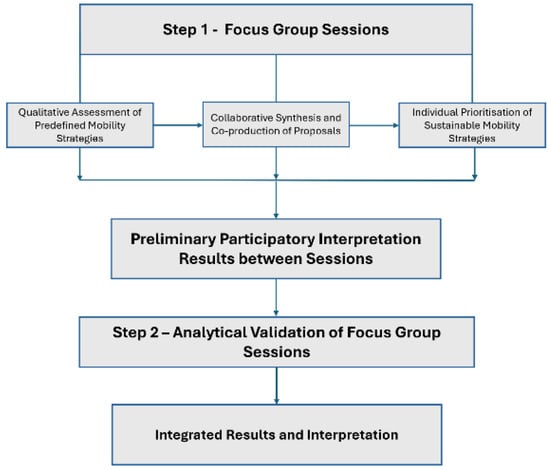

The methodological framework integrates two complementary stages (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Methodological diagram of the research process and analytical sequence.

- Focus Group Sessions and Discussions: Participatory diagnosis through focus groups with institutional and citizen stakeholders.

- Focus Group Data Analysis: Qualitative coding and co-occurrence analysis of the focus group sessions’ transcriptions, identifying conceptual interrelations among thematic dimensions.

This triangulated approach combined field observation, documentary sources, and deliberative participation, ensuring both empirical consistency and analytical depth.

2.2. Focus Group Sessions

2.2.1. Session’s Structure and Objectives

Each session lasted approximately 90 min and followed a four-phase structure designed to build trust, identify priorities, co-create solutions, and collectively assess them. This structure ensured a gradual transition from individual perceptions to shared synthesis, enabling the co-creation of context-specific strategies for sustainable mobility. Figure 2 presents the four-phase methodological structure of the focus group sessions, illustrating the progression from trust-building to the identification of priorities, co-creation of proposals, and their subsequent collective assessment.

Figure 2.

Four-phase methodological structure of the focus group sessions.

In phase two, open debate discussions centred on six predefined strategies, used as a shared conceptual framework to stimulate reflection and identify structural barriers and opportunities, followed by a visual voting exercise (green/yellow/red) that captured participants’ initial evaluations [2,3,16,17]:

- Pedestrian-only zones: promoting walkability and the reallocation of street space to pedestrians.

- Public transport integration: improving intermodality and coordination between transport modes.

- Pedestrian connectivity: ensuring safe, continuous, and accessible walking routes.

- Cycling promotion: encouraging active mobility through dedicated infrastructure and supportive facilities.

- New facility development: addressing local gaps in essential services and urban amenities.

- Low-emission zones: fostering environmentally responsible travel behaviour and improving air quality.

These strategies served as a standard conceptual reference to stimulate reflection and identify barriers, opportunities, and potential interventions within the study area [2,3,16,17].

Phases two and three primarily address RQ1 by eliciting participants’ perceptions of mobility challenges and accessibility constraints, while also contributing to RQ2 by collectively identifying barriers, priorities, and context-sensitive mobility strategies.

In phase three (see Table 1), whose main objective was to translate proposals into concrete territorial solutions, participants were invited to present individual proposals for improving mobility through collaborative work, using detailed maps of the study area to visualise specific spatial inequalities and opportunities. At the end of this phase, the generated proposals were also qualitatively assessed by participants using the same colour-coded evaluation scheme applied in phase two, allowing for a consistent comparison of perceived priorities across phases.

Table 1.

Comparative synthesis of the proposals from the three focus group sessions.

While phase three focused on a collaborative, spatially grounded diagnostic exercise, phase four constituted an entirely separate, autonomous activity. In this final phase, participants were invited to individually prioritise a distinct set of predefined mobility proposals through a digital scoring exercise, independent from the discussions and outputs generated in the earlier phases. Using an online polling tool, each proposal was rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = low priority; 5 = high priority), allowing individual preferences to be translated into comparable priority scores. These proposals are presented below:

- Expanding the cycling network.

- Improving the quality of existing cycling infrastructure.

- Increasing pedestrian–only zones.

- Providing real–time public transport information.

- Enhancing the quality of public transport services.

- Expanding the availability of shared mobility services.

This prioritisation exercise further supports RQ2 by translating deliberative discussions into structured assessments of proposed mobility interventions.

Taken together, phases two to four constituted the analytical core of the participatory process, enabling participants to discuss, map, and prioritise strategies for sustainable mobility in a structured, progressively collaborative manner.

2.2.2. Participant Selection

Given the exploratory and deliberative nature of the method, it was essential to select participants who could contribute informed, experience-based perspectives on mobility challenges and opportunities in the study area [31,32]. Institutional and technical participants were included based on their professional involvement in mobility planning, transport management, or related policy areas. In contrast, citizen participants were required to live, work, or regularly travel within São Martinho do Bispo. Individuals without direct professional or everyday experience of local mobility conditions were excluded.

In Coimbra, São Martinho do Bispo, three focus group sessions were conducted between March and April 2025, engaging 18 participants representing institutional, technical, and citizen perspectives. Institutional and citizen stakeholders were organised in separate groups to encourage open discussion and prevent potential power asymmetries.

Participants were recruited through local associations, municipal contacts, and institutional partnerships, based on their knowledge of mobility issues in the area. Participation was voluntary, and all contributors provided informed consent, with anonymity preserved through generic identifiers (e.g., Citizen 1, Local Authority 1).

The sample size was considered appropriate for exploratory qualitative research and deliberative focus group methodology, where analytical depth and interaction are prioritised over statistical representativeness. The number of participants and group sizes are consistent with established methodological recommendations for focus groups [33].

In line with recent expert-based and policy-oriented qualitative studies, relatively small samples are commonly accepted as methodologically appropriate when participants are selected for their domain knowledge and the objective is analytical depth rather than statistical generalisation. Recent studies in policy, management, and socio-technical research report comparable sample sizes (often between 10 and 25 participants) and treat them as sufficient for generating robust and credible qualitative insights [32,34,35,36,37]. Focus group research typically prioritises analytical richness, interaction, and diversity of perspectives over large numbers of participants [32,38,39]. Comparative methodological studies confirm that robust qualitative findings can be achieved with samples of 10–30 participants when participants are selected for their domain expertise and lived experience [40,41]. In this sense, the participation of 18 institutional, technical, and citizen actors in this study is consistent with established research practice and supports the methodological validity and credibility of the findings.

Across the focus group sessions, citizen participants were predominantly older adults, reflecting the study area’s demographic profile, with average ages above 60 years and a relatively balanced gender distribution. Their profiles included retired residents and active workers who regularly relied on walking, public transport, and private vehicles for daily mobility. This composition allowed the analysis to capture everyday accessibility constraints and mobility challenges, particularly relevant to ageing populations in low-density suburban contexts, while preserving participant anonymity. Separating institutional/technical and citizen participants was a deliberate methodological choice to reduce power asymmetries and foster open deliberation. This structure enabled citizens to articulate everyday mobility constraints without institutional influence, while institutional and technical actors reflected on governance, infrastructure, and policy feasibility. This separation was explicitly designed to mitigate potential power asymmetries between institutional and citizen actors and to foster more balanced and open deliberation.

2.3. Step 2—Analytical Validation of Focus Group Sessions Data

The analytical validation phase was designed to deepen insights from the focus group sessions and to address RQ2 and RQ3 by systematically examining thematic patterns, interrelations, and conceptual associations emerging from participants’ discussions.

This analytical phase was also explicitly designed to ensure methodological transparency regarding code development, segmentation procedures, and co-occurrence thresholds.

The analytical stage sought to identify conceptual associations among themes and validate the qualitative insights emerging from the participatory process. All focus-group sessions were recorded, transcribed with informed consent, and triangulated with documentary sources and field observations to strengthen interpretive reliability. Data were analysed using Atlas.ti 25, which enabled systematic coding and interpretation of the transcripts [42,43,44]. Atlas.ti 25 was used as a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis tool to support coding and thematic exploration. Analytical robustness was ensured through repeated coding and re-analysis using a consistent coding framework and fixed parameters.

The coding scheme was developed using a hybrid inductive–deductive approach. Deductive codes were initially defined based on the ENTROPY framework, the research questions, and the six core thematic dimensions, while inductive codes emerged through close reading of the transcripts to capture context-specific mobility issues. Coding was conducted iteratively, with code definitions refined across successive rounds of analysis. Although an initial analytical structure was used, the coding process remained open to emergent themes, allowing empirical material to challenge and refine predefined categories, thereby mitigating the risk of pre-structured analytical bias. Consistency was ensured by re-coding selected transcripts using the final coding scheme and cross-checking the application of codes across focus group sessions. A single researcher conducted all coding; therefore, formal inter-coder reliability was not calculated, which is acknowledged as a methodological limitation.

Conceptual associations among codes were explored through co-occurrence analysis, which identifies how frequently two codes appear within the same textual segment as an indication of thematic proximity [43].

Transcripts were segmented into meaningful thematic units (sentences or short paragraphs addressing a single mobility-related issue), which constituted the basic coding units in Atlas.ti 25.

The hierarchical coding framework included six thematic dimensions: (i) Built Environment, (ii) Public Transport Accessibility, (iii) Infrastructure and Services, (iv) Digitalisation, (v) Diversity, and (vi) Governance and Participation.

The co-occurrence coefficient (c) was calculated using the following expression:

where represents the number of segments coded simultaneously with both codes, and and denote their individual frequencies. The coefficient ranges from 0 (no association) to 1 (maximum association), indicating the degree of conceptual co-occurrence.

In line with recommendations for discourse and thematic network analysis [43,45], coefficients were interpreted qualitatively rather than statistically, as high values may reflect overlapping or redundant codes rather than genuine conceptual links. Following Friese [43], Alamillo [46], and Scharp [47], very high coefficients (>0.50) were treated cautiously as they may indicate redundancy, while intermediate values (0.20–0.50) were interpreted as analytically meaningful conceptual associations. A threshold value of c ≥ 0.20 was therefore adopted to balance interpretive relevance with the risk of spurious associations in a corpus of moderate size (18 participants, three focus groups).

The analytical interpretation followed two complementary stages:

- Intra-group analysis—exploring relationships within the six thematic dimensions.

- Inter-group analysis—examining cross-cutting associations between the six thematic dimensions

This qualitative analysis, combining interpretive depth with co-occurrence analysis, strengthened the empirical validity of the participatory findings presented in Step 1 and provided the analytical basis for discussing challenges and opportunities in sustainable mobility promotion in the case study.

By identifying co-occurrences between accessibility, governance, infrastructure, and digitalisation dimensions, this analytical phase provides a structured basis for assessing how proximity-based mobility models can be adapted to low-density suburban contexts (RQ3).

2.4. Case Study Description

Coimbra, located in central Portugal, is a medium-sized city with approximately 119,000 inhabitants [48]. Its urban development reflects a historical transition from a compact medieval core to a fragmented metropolitan area shaped by unregulated suburban expansion since the mid-twentieth century [49]. The post-war rise in motorised mobility and car-oriented planning reinforced low-density sprawl, producing a spatial duality between consolidated central districts and dispersed peripheral zones. This pattern, common across Southern European cities, poses significant challenges for sustainable mobility, as improved regional accessibility often coincides with reduced local connectivity and a strong dependence on private vehicles.

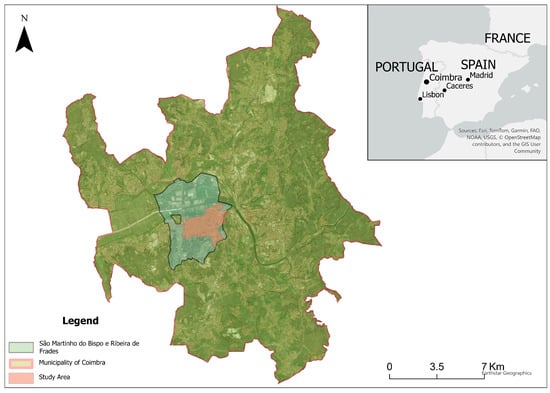

São Martinho do Bispo, situated on Coimbra’s southwestern periphery (Figure 3), exemplifies these dynamics. Covering approximately 21 km2 and home to around 13,000 residents, it combines an older rural nucleus with newer housing developments, resulting in a heterogeneous suburban fabric characterised by dispersed land use, low population density, and high car dependency. Local demographic trends include an ageing population in the traditional settlement cores and younger families in recent developments, creating diverse mobility needs. The area’s topography, marked by steep slopes, further constrains active travel, particularly for older residents and people with reduced mobility.

Figure 3.

Geographical location of the study area within the municipality of Coimbra, Portugal.

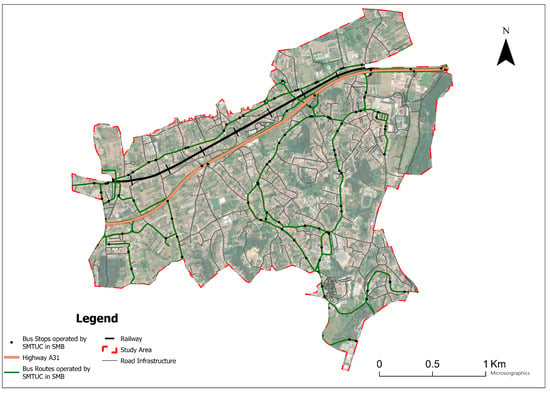

Major infrastructure, such as the A31 highway and the railway line, enhances regional accessibility but creates internal barriers for pedestrians and cyclists. Public transport is operated by SMTUC, with roughly one hundred stops linking São Martinho do Bispo to the city centre. However, low service frequency, irregular schedules, and limited coverage reduce its attractiveness, especially in peripheral neighbourhoods. Pedestrian pathways are fragmented, and dedicated cycling infrastructure is almost absent [50], although municipal plans foresee new cycling connections to major educational and service hubs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mobility infrastructure in São Martinho do Bispo.

A necessary mobility transformation in the municipality is the ongoing implementation of the Metro Mondego [51], a light rail system that has been converted into a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) network. This project aims to replace the former regional railway line with a high-capacity, electrically powered system connecting peripheral parishes to the city centre and university areas. Although São Martinho do Bispo is not directly served by the main BRT corridor, the system is expected to influence local mobility through improved regional connectivity, feeder services, and potential integration with cycling and pedestrian networks. However, its success will depend on effective multimodal coordination and the ability to address last-mile constraints in low-density areas.

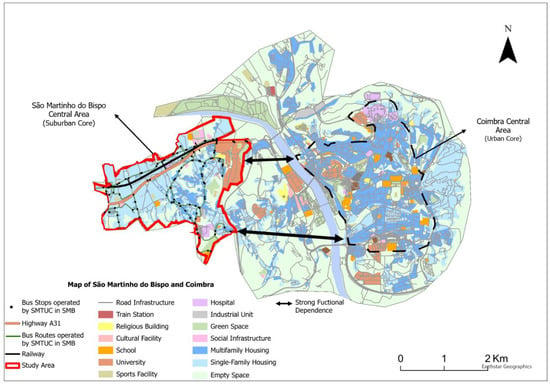

Beyond its residential function, São Martinho do Bispo also serves as a peri-urban employment and service hub, hosting major institutions including the Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra and the Hospital dos Covões. These trip-generating activities attract high daily traffic volumes and exert continuous pressure on local infrastructure, reinforcing reliance on motorised transport while exposing the lack of safe, efficient, and multimodal alternatives (Figure 5). University-related flows, particularly between student residences and educational campuses, intensify peak-hour congestion and highlight the need for improved multimodal connections.

Figure 5.

Mobility infrastructure network and land use patterns in São Martinho do Bispo (Coimbra).

3. Results and Discussion

This section introduces the analytical interpretation of the three focus group sessions conducted in São Martinho do Bispo. It examines how institutional, technical, and citizen participants perceived the main mobility challenges and opportunities in the area, identifying key patterns of agreement and divergence that underpin the strategies developed later in this chapter.

3.1. Step 1—Focus Group Sessions

3.1.1. Focus Group Description

The following subsections present the results according to the four-phase structure defined in the methodological framework (see Figure 2). Although phase one focused on trust-building and is not analysed in detail, the organisation of this section follows the sequence of the participatory process, with results reported for phases two to four: the qualitative assessment of predefined mobility strategies, the collaborative synthesis and co-production of proposals, and the individual prioritisation of sustainable mobility strategies. Figure 6 summarises the composition of the focus groups and the sequencing of the sessions, illustrating the diversity of participant profiles and the organisation of the collaborative process.

Figure 6.

Overview of the Focus Group Sessions: Participant Profiles and Session Dates.

3.1.2. Qualitative Assessment of Predefined Mobility Strategies

The second phase of the focus groups aimed to identify mobility priorities through structured discussions around six predefined strategies. Participants debated constraints and opportunities related to pedestrian-only zones, public transport integration, pedestrian connectivity, cycling infrastructure, new facilities, and low-emission zones. The voting results are presented in Appendix A. The discussion below qualitatively interprets these outcomes, integrating participants’ perspectives with relevant theoretical insights from the literature.

- 1.

- Pedestrian-Only Zones

Pedestrianisation generated both enthusiasm and caution. Most participants recognised its potential to enhance safety and life ability, while institutional actors raised concerns about parking management and logistics:

“Pedestrian areas are essential for quality of life, but we must think about where people will park and how deliveries will be made.”—Municipal representative

Institutional and technical stakeholders (FG1 and FG2) expressed neutral positions (yellow), citing the fragmented urban structure and the need for detailed planning. Citizens (FG3) showed unanimous support (green) for flexible pedestrianisation around schools and local amenities. This tension between technical caution and experiential pragmatism reflects common patterns in participatory planning [10,11,30].

Pedestrianisation is recognised as a key component of sustainable urban transitions, fostering reduced car dependence and improved environmental quality [2,52,53], though its success in low-density contexts depends on careful local adaptation [16,17,18,54,55].

- 2.

- Public Transport Integration

Public transport integration was the most consensual strategy, receiving positive evaluations (green) across all focus groups. Participants emphasised coordination, comfort, and shorter travel times:

“It is inconceivable that a public transport route takes 50 min when the same trip by car takes 15.”—Municipal representative

This convergence highlights the importance of reliable, user-centred design in reducing dependence on motorised private transport [2,16]. Participants agreed that better intermodal coordination and more regular service are essential for sustainable mobility in suburban areas.

- 3.

- Pedestrian Connectivity

Pedestrian connectivity received unanimous support (green) across all groups. Participants linked continuous and safe pedestrian routes with inclusion and accessibility:

“Pedestrians are still forced to walk along drainage ditches, often without pavements or with interrupted ones.”—Regional authority participant

Institutional actors considered connectivity a structural prerequisite for planning, while citizens described it as a daily obstacle. This convergence between strategic and lived perspectives reinforces the centrality of walkability in equitable mobility planning [2,52].

- 4.

- Cycling Infrastructure

Cycling infrastructure elicited mixed responses. Institutional and technical groups (FG1 and FG2) expressed neutral-to-negative views (yellow/red), citing safety concerns and the absence of a cycling culture. Citizens (FG3) voted positively (green), stressing the need for dedicated routes, particularly along the A31 corridor, and improved coexistence between cyclists and motorists:

“Cycle lanes are especially helpful for less experienced users, but respect between drivers and cyclists is disappearing.”—Local association participant.

While institutional scepticism prevailed, citizens appeared more open to behavioural change, provided that infrastructure ensured safety and continuity. This pattern reflects broader evidence that cycling adoption in suburban contexts depends on network quality and perceived safety [56,57,58,59,60].

- 5.

- Development of New Facilities

This strategy revealed divergent evaluations. Institutional and technical stakeholders (n = 13) cast mostly negative votes (red = 8), reflecting caution toward new investments, while citizens (n = 5) were more supportive (green = 3), especially for preschools and cultural amenities:

“We must reorganise and upgrade what already exists.”—Education-sector representative.

The divergence reflects differing priorities: institutional actors emphasised efficiency and maintenance, whereas citizens focused on everyday accessibility. This illustrates the value of participatory planning in aligning community needs with strategic frameworks [2,3,10,17].

- 6.

- Low-Emission Zones

Low-emission zones (LEZ) received cautious but broadly positive evaluations, with 8 positive, 9 neutral, and 1 negative vote among institutional participants, and 4 positive and 1 neutral among citizens:

“It is super important, but will people actually respect it?”—Citizen participant.

Both groups acknowledged the environmental benefits of LEZ but stressed fairness, gradual implementation, and the need for affordable public transport alternatives. This cautious support reflects findings that acceptance of restrictive measures depends on perceived fairness and institutional trust [3,17,61,62,63].

Taken together, these discussions reveal that accessibility and connectivity underpinned the most widely shared priorities. In contrast, strategies requiring behavioural adaptation or regulatory enforcement, such as cycling promotion and low-emission zones, elicited more cautious responses. Beyond the individual colour-coded evaluations, a cumulative reading of voting patterns across the three focus groups highlights clear gradients of consensus and divergence: pedestrian connectivity and public transport integration emerged as high-consensus strategies, while cycling infrastructure and low-emission zones revealed more differentiated positions between institutional and citizen actors. This pattern highlights the complementarity between citizens’ pragmatic perspectives and institutions’ systemic rationality, demonstrating that sustainable mobility transitions rely on reconciling experiential knowledge with technical planning. The participatory process showed how collaborative deliberation can bridge these perspectives, providing legitimate and context-sensitive foundations for advancing sustainable mobility in low-density suburban environments [2,10,11].

3.1.3. Collaborative Synthesis and Co-Production of the New Proposals

Phase three, as defined in the methodological framework, centred on a collaborative, spatially grounded diagnostic exercise in which participants identified local barriers, opportunities, and mobility needs using detailed maps of the study area. This phase also enabled participants to formulate context-specific proposals to improve mobility in São Martinho do Bispo, drawing on their lived experiences and understanding of institutional and infrastructural constraints. These contributions provided valuable insights into feasible pathways for sustainable mobility transitions in suburban areas.

To complement the qualitative findings, Table 2 presents a comparative synthesis of the proposals generated across the three focus group sessions. The table highlights the areas of convergence and divergence between institutional, technical, and citizen groups. This comparative view enables the identification of shared priorities, such as improving public transport and pedestrian infrastructure, while also revealing context-specific proposals, including micro logistics solutions and the creation of cultural or educational facilities.

Table 2.

Average priority scores assigned by stakeholder groups.

The synthesis above provides the empirical foundation for a deeper interpretative analysis, connecting participants’ proposals with broader theoretical perspectives on collaborative and sustainable mobility planning. The findings reinforce that effective mobility transitions depend not only on infrastructure and policy coordination but also on civic engagement, local knowledge, and the co-production of context-sensitive solutions [2,3,10,11,17].

3.1.4. Individual Prioritisation of Sustainable Mobility Strategies

In the fourth phase, participants engaged in an autonomous, individually based prioritisation exercise, distinct from the discussions and outputs of the previous phases. Using the Slido digital platform, each participant was invited to evaluate a predefined set of sustainable mobility proposals, assigning a score from 1 (low priority) to 5 (high priority). These proposals were not generated during the focus group discussions; the research team introduced them to assess participants’ preferences for concrete mobility interventions. The resulting scores enabled a comparative assessment of priorities across stakeholder groups, revealing patterns of convergence and divergence. Table 2 presents the average priority scores assigned by institutional and technical stakeholders (FG1 and FG2) and by citizens (FG3) [30,60,61].

The comparative results reveal a strong convergence around active and collective modes, confirming a shared commitment to accessibility and sustainability across stakeholder groups.

Among institutional and technical actors, the highest priorities were assigned to expanding cycling infrastructure (4.7), increasing the availability of shared mobility services (4.6), and creating pedestrian zones (4.5). These preferences reflect an understanding of sustainable mobility as dependent on diversifying modal options and integrating technological solutions beyond conventional public transport. Their emphasis on flexibility, multimodality, and digitalisation indicates a shift from infrastructure-centred approaches toward integrated mobility ecosystems that link governance coordination, innovation, and behavioural change [2,54,64].

For citizens, the priorities were rooted in everyday experience. The highest scores were given to improving public transport and cycling infrastructure (5.0 each), followed by pedestrian zones (4.8) and real-time public transport information (4.6). Shared mobility services received a lower but still positive evaluation (4.0), suggesting cautious interest influenced by limited familiarity with these emerging systems. This pattern expresses a pragmatic orientation in which usability, comfort, and reliability take precedence over systemic innovation, an outlook consistent with the literature on mobility justice and participatory planning, which stresses the need to connect strategic sustainability goals with lived urban realities [3,17,65].

Overall, the prioritisation exercise functioned not only as an evaluative mechanism but also as a reflexive process that enhanced mutual understanding among stakeholder groups. The complementarity between institutional rationality and citizen pragmatism underscores that advancing sustainable mobility in suburban contexts requires inclusive and adaptive governance capable of integrating strategic planning with everyday experience [2,10,11].

3.1.5. Preliminary Participatory Interpretation Results Between Sessions

The synthesis of proposals and prioritisation results across the three focus group sessions reveals both shared priorities and differentiated perspectives regarding the transition toward sustainable mobility in São Martinho do Bispo. Building on the comparative findings presented in Table 2, this analysis examines how institutional, technical, and citizen viewpoints intersect across the six thematic dimensions of sustainable mobility, illustrating the mediating role of collaborative processes in the relationship between institutional rationalities and lived mobility experiences.

Consistent with theories of collaborative and communicative planning [10,11] and sustainable mobility transitions [2,18,54], the findings demonstrate the value of participatory arenas in bridging expert and experiential knowledge. Public transport and pedestrian infrastructure emerged as the most consensual domains, confirming that accessibility, reliability, and safety constitute the foundation of equitable mobility systems and urban livability [16,17,52]. From a spatial justice perspective, participants’ emphasis on continuous pedestrian networks, safe crossings, and reliable public transport reflects concerns about uneven access to daily services, particularly affecting older residents and car-dependent households in peripheral areas. This convergence reflects a pragmatic understanding among participants that spatial quality and service integration are essential to reducing dependence on motorised private transport and enhancing collective accessibility.

By contrast, dimensions such as cycling, logistics, and connectivity exposed the constraints of suburban contexts, where dispersed settlement patterns and infrastructural discontinuities limit the feasibility of low-carbon modes [23,60]. These themes revealed deeper structural and behavioural tensions: while participants recognised the desirability of cycling and micro logistics, they emphasised the need for sustained institutional commitment, regulatory support, and cultural adaptation to ensure their implementation. Such tensions were frequently framed by participants in terms of unequal mobility opportunities across neighbourhoods, highlighting how infrastructural discontinuities and limited service provision translate into spatially differentiated access. The education and community dimension, highlighted across all groups, reinforced that mobility transitions are not merely technical endeavours but social processes of learning, negotiation, and behavioural change [3,62,63].

The prioritisation exercise further clarified how these shared and divergent perspectives were translated into evaluative preferences. Results revealed strong convergence around active and collective modes, confirming a cross-group commitment to accessibility and sustainability. Nonetheless, subtle but meaningful differences persisted:

- Institutional actors emphasised coordination, system efficiency, and the need for long-term planning.

- Citizens prioritised concrete, locally grounded improvements that directly enhance daily mobility.

This complementarity underscores that advancing sustainable mobility in suburban contexts requires reconciling strategic and experiential perspectives through inclusive and adaptive governance [2,10,11]. The prioritisation process thus functioned not only as an evaluative mechanism but also as a reflexive exercise, strengthening mutual understanding of priorities and trade-offs among stakeholder groups.

Taken together, the participatory process demonstrated that transformative change in mobility systems depends on more than physical infrastructure. It requires governance frameworks that integrate spatial planning, behavioural adaptation, and social inclusion. In this sense, spatial justice emerges not as an abstract normative principle, but as an empirical concern grounded in participants’ accounts of uneven pedestrian conditions, service discontinuities, and the exclusion risks associated with ageing and digital dependency. Building trust, coordinating institutions, and empowering citizens are preconditions for successful mobility transitions [2,10]. The co-creative proposals and subsequent prioritisation reveal how collaborative planning can serve simultaneously as a governance instrument and a catalyst for social learning, generating legitimate, context-sensitive foundations for sustainable mobility in low-density suburban environments.

By linking to structured evaluation, this synthesis provides an empirically grounded foundation for the next analytical stage, which examines how these shared priorities materialised across thematic dimensions through intra- and inter-group analyses.

3.2. Step 2—Analytical Validation of Focus Group Insights

This section presents the analytical validation of the ideas and proposals that emerged during the third phase of the focus group sessions. Using Atlas.ti 25, both intra- and inter-group co-occurrence analyses were performed to identify conceptual relationships among thematic codes. These analytical results not only characterise participants’ perceptions but also empirically substantiate the eight strategic axes for sustainable mobility, which were later synthesised through co-creation.

3.2.1. Intra-Group Analysis

The intra-group analysis explores relationships between thematic codes within each dimension of sustainable mobility. Coefficients of 0.20 or greater were considered analytically significant, indicating conceptual proximity between participants’ perceptions. This approach revealed interconnected patterns linking infrastructure, governance, digitalisation, and behavioural factors that shape daily mobility in São Martinho do Bispo. The results (Table 3) highlight that physical design, digital integration, and participatory governance operate as mutually reinforcing pillars of sustainable mobility transitions.

Table 3.

Summary of key intra-group co-occurrences identified in Atlas.ti 25.

Within the built environment, participants consistently associated the perceived quality of urban space with the continuity and safety of pedestrian infrastructure, confirming walkability as both a spatial and social advantage [23,52,66]. Digitalisation emerged as a critical enabler of reliability and coordination in public transport, with participants recognising the value of real-time information and integrated service apps, yet warning that overreliance on digital systems risks excluding vulnerable users [3,67,68]. The diversity dimension underscored the relevance of mixed land use and proximity to essential services, such as retail and healthcare, as anchors for low-carbon, community-based mobility [2,16].

In governance and participation, co-occurrences indicated that policy acceptance depends on meaningful citizen engagement and transparent communication, as top-down measures were often perceived as disconnected from everyday mobility realities [15]. Within infrastructure and services, participants emphasised the absence of small-scale facilities, such as secure bike parking, while mismatched schedules and inconsistent frequency constrained public transport accessibility.

Overall, the intra-group analysis reveals that sustainable mobility transitions rely on alignment across spatial, technological, and institutional dimensions: physical design supports accessibility, digital tools enhance efficiency and trust, and collaborative governance fosters legitimacy and behavioural change. These findings align with the principles of communicative and adaptive planning [11,30], which emphasise the co-production of spatial, technological, and behavioural dimensions through inclusive, context-sensitive processes.

3.2.2. Inter-Group Analysis

The inter-group analysis examines how the six thematic dimensions of sustainable mobility, Built Environment, Public Transport Accessibility, Infrastructure and Services, Digitalisation, Diversity, and Governance and Participation, interact across stakeholder groups. Co-occurrence coefficients above 0.20 were considered significant, indicating conceptual overlaps among spatial, institutional, and behavioural perspectives. This analytical stage highlights how understandings of sustainability are co-constructed through dialogue between citizens, institutional representatives, and technical experts, offering a relational view of suburban mobility systems [2,23].

Table 4 presents the strongest inter-group co-occurrences, illustrating how cross-dimensional interactions, such as those between infrastructure and governance or digitalisation and multimodality, reflect shared priorities and tensions among stakeholder groups.

Table 4.

Summary of key inter-group co-occurrences identified in Atlas.ti 25.

The co-occurrence between Park and Ride and Multimodality (c = 0.36) reflects a shared recognition that efficient intermodality is essential to reducing private-car dependency. However, participants noted that weak peripheral infrastructure and limited coordination between operators and municipalities continue to constrain integration, reinforcing the need for planning frameworks that align physical infrastructure with institutional collaboration [4,54,64].

The association between Healthcare and Funding Initiatives (c = 0.31) shows collective awareness of the link between active mobility, public health, and fiscal efficiency. Stakeholders suggested that investing in walking and cycling could generate measurable healthcare savings, supporting European priorities for health-oriented, cross-sectoral governance [57,66].

Digitalisation also emerged as a unifying theme. The connection between Payment Systems and Multimodality (c = 0.23) illustrates the pivotal role of digital tools in enabling seamless mobility. Participants viewed integrated ticketing and real-time information as foundations for a Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) framework capable of merging physical and digital infrastructures into a coherent, user-centred system [16,67].

At the governance interface, the relationship between Effectiveness of Policies and Accessibility (c = 0.20) confirms that legitimacy depends on visible, tangible improvements and clear communication. Stakeholders emphasised that restrictive measures, such as low-emission zones, must be accompanied by viable alternatives to sustain public trust [10,11,15]. Similarly, the co-occurrence between Multimodality and Social Rejection (c = 0.20) underscores that acceptance of mobility projects relies more on trust and transparency than on technical design alone. Participants highlighted that inclusive communication and co-decision processes are critical to prevent social resistance, consistent with communicative planning theory [15,69].

Finally, the association between Quality of Public Transport Stops and Waiting Time (c = 0.20) reveals how spatial quality directly shapes perceptions of service reliability. Poorly maintained or poorly designed stops intensify the discomfort of long waits, especially for vulnerable users, thereby eroding confidence in public transport. Addressing these issues through participatory design can strengthen both accessibility and institutional credibility [23,52].

The inter-group analysis demonstrates that sustainable mobility transitions in São Martinho do Bispo depend on the alignment of spatial, institutional, and social dimensions. Building trust, ensuring physical quality, and integrating digital tools are essential to creating a coherent and inclusive mobility ecosystem.

3.2.3. Synthesis of Intra- and Inter-Group Findings

The synthesis of the intra- and inter-group analyses provides an integrated perspective on how participants collectively interpreted and negotiated the concept of sustainable mobility. Across both analytical levels, three interdependent pillars emerged as fundamental to mobility transitions in suburban contexts: space and infrastructural quality, digital integration, and participatory governance [2,23,54].

At the intra-group level, participants associated the quality of the built environment, service accessibility, and land-use diversity with everyday well-being and social inclusion. These associations illustrate that the material and social fabric of urban space remains central to the experience of mobility systems. The inter-group analysis, in turn, revealed that such physical and functional priorities must be underpinned by institutional coordination and social trust to achieve systemic effectiveness. The strongest inter-group co-occurrences, particularly between Public Transport Accessibility, Infrastructure, and Governance, demonstrate that mobility transitions depend on shared responsibility across governance levels [62,64].

Digitalisation emerged in both analyses as a cross-cutting enabler. Within groups, it was perceived as essential for reliability and user confidence; across groups, it acted as a bridge between the physical and operational dimensions, reflecting the logic of Mobility-as-a-Service frameworks. Similarly, governance and participation appeared as decisive conditions of legitimacy, confirming that behavioural change requires transparency, dialogue, and co-designed communication [15,70].

Together, these findings indicate that advancing sustainable mobility in São Martinho do Bispo requires aligning spatial design, technological integration, and participatory governance. This analytical convergence provides a robust empirical foundation for the following section, where the co-created strategies translate these shared priorities into actionable planning principles.

3.2.4. Co-Creation of Mobility Strategies

Building on the validated insights from the intra- and inter-group analyses, this final phase translated the collective priorities of all stakeholder groups into a coherent strategic framework. Through an iterative process of deliberation and analytical validation in Atlas.ti 25, participants transformed conceptual discussions into a shared action agenda for sustainable mobility in São Martinho do Bispo [10,70].

Each proposal was cross-checked against the co-occurrence analysis results to ensure empirical consistency through significant associations (c ≥ 0.20) between key thematic codes. This triangulation process consolidated eight interrelated strategies that articulate a community-driven vision for an inclusive and sustainable mobility system (Table 5).

Table 5.

Co-created sustainable mobility strategies for São Martinho do Bispo (Coimbra).

The co-created strategies converge around three complementary dimensions. The grouping of strategies into these three axes reflects recurring patterns identified across focus-group discussions and co-occurrence analysis. The spatial axis focuses on redesigning the built environment to prioritise walking, cycling, and safety, addressing the fragmented urban fabric typical of suburban areas [2,17,52]. The operational axis emphasises improving public transport reliability, multimodal integration, and digital innovation through real-time systems and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) [16,67,68].

Finally, the governance and cultural axis highlights education, awareness, and institutional travel planning as mechanisms for long-term behavioural change and coordination across policy domains [10,70]. Together, these axes define a place-based, participatory framework for advancing sustainable mobility in São Martinho do Bispo [23,54].

Building on these collaboratively defined strategies, the following section synthesises their broader theoretical and policy implications, exploring how the São Martinho do Bispo case contributes to rethinking governance, equity, and implementation pathways for sustainable mobility in the suburban context. In particular, it explicitly links the reinterpretation of the 15-Minute City, TOD, and MaaS to the empirical patterns identified across focus-group discussions and to the strongest intra-/inter-group co-occurrences between accessibility, the built environment, governance, and digitalisation.

3.3. Synthesis and Policy Implications

The combined analysis of focus-group results and co-occurrence data demonstrates that advancing sustainable mobility in suburban contexts such as São Martinho do Bispo requires more than isolated interventions. Meaningful transformation depends on an integrated framework that links spatial quality, digital innovation, and participatory governance. Accessibility, inclusiveness, and institutional coordination operate as interdependent conditions for equitable and enduring mobility transitions [2,3,4,54]. Analytically, the reinterpretation of proximity-based models is grounded in the systematic coding of focus-group transcripts and in the analysis of recurring discursive patterns and co-occurrences between key thematic dimensions, particularly accessibility, governance, and infrastructure. Rather than treating proximity-based models as normative planning frameworks, this study empirically demonstrates how they are reinterpreted in practice through participatory focus-group processes in a low-density suburban context.

More specifically, these reinterpretations reveal that participants did not adopt proximity-based models as fixed templates but instead reinterpreted their core principles in light of recurring, concrete constraints discussed across sessions. In particular, “proximity” was repeatedly articulated through safe, continuous pedestrian access to everyday destinations (e.g., schools, retail, and healthcare) and through reduced waiting times and improved service reliability (Section 3.1.2 and Section 3.1.3). This interpretation is empirically supported by the strongest analytical associations identified in Atlas.ti 25, especially between the built environment and pedestrian space, and between digital tools and public transport reliability (Table 3 and Table 4).

Taken together, the findings show that participants did not adopt proximity-based models as fixed templates but reinterpreted their core principles to fit the constraints of a low-density suburban context. The 15-Minute City was reframed as a functional goal of ensuring pedestrian access to essential services rather than universal morphological proximity; Transit-Oriented Development was understood as a strategy of multimodal integration and feeder services at strategic nodes rather than densification; and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) was operationalised through real-time information and integrated ticketing, while raising concerns about digital exclusion. These reinterpretations are grounded in participants’ accounts and illustrate how proximity-based paradigms are reshaped by suburban dispersion, ageing populations, and fragmented governance.

First, public transport reliability and spatial accessibility form the structural foundation for all other strategies. Participants repeatedly emphasised the importance of service predictability, safe waiting environments, and continuous physical connections, underscoring that infrastructural improvement and social trust are mutually reinforcing [2,16,17,53]. These concerns were frequently framed in terms of uneven access, particularly affecting older residents and peripheral neighbourhoods, linking accessibility directly to issues of spatial justice.

Second, human-scale public-space design emerged as a transversal condition for sustainability. Continuous sidewalks, safe crossings, and well-maintained pedestrian corridors are not complementary measures but prerequisites for modal integration and urban equity. Walkability functions as the connective tissue of the mobility system, enabling cycling networks and facilitating access to transport hubs and local facilities. These findings support Gehl’s [52] and Martens’ [17] argument that spatial justice and active mobility must converge within urban planning, forming the physical backbone of integrated mobility systems [18,54].

Third, governance and participation are decisive in transforming awareness into action. The study reveals that even technically sound measures, such as low-emission zones or new facilities, risk rejection if not co-produced with stakeholders and paired with viable alternatives. Legitimacy arises from transparent communication, shared problem framing, and the continuity of dialogue between institutions and citizens, reflecting the principles of communicative and collaborative planning [10,11,70,71].

At the operational level, the co-creation phase highlighted that policy coherence depends on alignment across the physical, behavioural, and digital dimensions. Enhancing pedestrian and cycling infrastructure must be complemented by digital tools that provide real-time information, integrated payment systems, and feedback mechanisms. This integration aligns with the Mobility as a Service (MaaS) paradigm [67,68], which redefines accessibility as a service ecosystem rather than a collection of discrete modes. At the same time, the findings caution that digitalisation must be implemented inclusively, ensuring the availability of analogue alternatives to prevent new forms of exclusion, particularly among older users, reinforcing the need for inclusive accessibility strategies.

The participatory process itself proved to be transformative. Through deliberation, mapping, and co-design, participants did not merely identify barriers; they collectively reframed mobility as a shared public responsibility. In this sense, collaborative planning emerges not only as a methodological choice but as a form of governance innovation, capable of generating legitimacy and mobilising collective intelligence [11,15,70]. For policymakers, the implication is clear: achieving sustainable mobility requires technical optimisation coupled with institutional learning and social co-ownership.

In the subsequent synthesis phase, outputs from all groups were treated as analytically equivalent and systematically compared, with no hierarchical weighting between institutional, technical, or citizen inputs, ensuring that citizen perspectives directly informed the final eight co-created strategies rather than being filtered through institutional interpretations. This strengthened the legitimacy of the process and confirmed collaborative planning as a form of governance innovation in low-density suburban contexts. To enhance planning relevance, the findings distinguish between aspirational preferences voiced in the focus groups, the eight co-produced strategies, and feasible interventions with differentiated implementation pathways. In low-density suburban contexts, feasibility is shaped by fiscal capacity, fragmented governance, minimum service thresholds for public transport, and land-use inertia, which condition how strategies can be operationalised and involve unavoidable trade-offs between ambition, resources, and institutional capacity. Infrastructure-related strategies largely depend on municipal authorities and transport operators, whereas schools, local associations, and community organisations can more effectively advance awareness and behavioural initiatives.

4. Conclusions

The case of São Martinho do Bispo demonstrates that sustainable mobility transitions in low-density suburban contexts can be supported when communities are actively engaged in shaping territorial strategies [10,11]. The participatory process enabled local stakeholders to articulate a shared vision of accessibility grounded in integrating active travel, public transport, and digital connectivity. The eight (8) co-created strategies, ranging from improvements to pedestrian and cycling infrastructure to the development of mobility plans for schools and workplaces, constitute a coherent framework that directly responds to the territory’s physical and social specificities. These measures illustrate that even in fragmented suburban environments, functional proximity may be strengthened through coordinated interventions across spatial, institutional, and behavioural dimensions [2,54]. In practice, these strategies imply differentiated implementation pathways, with infrastructure-related measures largely dependent on municipal coordination. At the same time, awareness and cultural initiatives may be more readily advanced through community-based collaboration within a fragmented institutional context.

From this local experience, three broader lessons emerge for suburban mobility planning. First, accessibility must be understood as a multidimensional concept, encompassing reliable public transport, safe and continuous pedestrian infrastructure, and inclusive digital tools [3,17]. Second, the legitimacy and effectiveness of mobility policies depend on co-production mechanisms in which citizens, technicians, and institutions collaboratively design solutions anchored in everyday practices [70,71]. Third, innovation in suburban mobility requires adaptation rather than replication, transforming global models such as the 15-Minute City or Transit-Oriented Development into locally meaningful frameworks aligned with territorial realities [20,68].

These findings suggest that proximity can be functionally reconstructed through the combination of multimodal transport systems, equitable public-space design, and digital integration via Mobility as a Service (MaaS) [16,67]. When implemented through collaborative governance, these may not only improve accessibility and efficiency but also reinforce social trust and collective ownership of urban transformation processes [23].

Ultimately, this research underscores that reorganising mobility in suburban areas is both possible and necessary when grounded in collaborative planning [10,15]. By placing citizens at the centre of decision-making, urban planning evolves from a technical exercise into a democratic process of co-creation, capable of producing more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable suburban futures [11,70]. The insights derived from São Martinho do Bispo invite further comparative research and policy experimentation in similar European contexts, contributing to the broader debate on how participatory and proximity-based planning can advance territorial cohesion and climate resilience.

This study also acknowledges several limitations. First, the analysis focuses on a single suburban case, São Martinho do Bispo, whose specific socio-spatial characteristics may limit the generalisability of the results. However, the comparative scope of the ENTROPY project partly mitigates this limitation by situating the case within broader European suburban dynamics. Second, the participatory approach relied on a limited number of focus groups, which may not fully capture the diversity of local mobility experiences. Nonetheless, the inclusion of institutional, technical, and citizen stakeholders ensured plural perspectives and broadened the range of viewpoints captured. In addition, the citizen participants were predominantly older adults, reflecting the demographic structure of the study area, which may have influenced the types of mobility needs and priorities emphasised during the discussions, while potentially underrepresenting other vulnerable or less visible groups (e.g., younger low-income residents, migrants, or people with disabilities). Although group separation reduced power asymmetries, subtle forms of institutional framing cannot be entirely excluded, which is an inherent limitation of participatory research. Recruitment was also constrained by limited availability and willingness to participate, a common challenge in suburban, car-dependent contexts, further limiting the sample’s size and diversity. Third, as with most qualitative and deliberate research, the findings reflect negotiated understandings rather than measurable outcomes. At the same time, systematic coding and co-occurrence analysis are performed in Atlas.ti 25 reduced potential bias, interpretive subjectivity cannot be eliminated. Finally, the co-created strategies should be viewed as preliminary frameworks requiring validation through implementation and quantitative assessment. Despite these constraints, the study offers a context-sensitive approach that may inform similar participatory processes in other suburban settings, subject to adaptation.

Importantly, this research does not evaluate the long-term implementation feasibility of the proposed strategies. The focus groups should be understood as an initial deliberative step aimed at identifying shared priorities and informing subsequent analytical and decision-making stages.

Building on this research, a follow-up survey will be conducted in the municipality of Coimbra, designed to align with the analytical dimensions explored in this study and focused on local mobility strategies. The questionnaire will be distributed to both focus group participants and residents who were unable to attend, introducing a quantitative dimension, supported by the MACMA model, to complement the qualitative insights obtained thus far. In parallel, a targeted survey will be administered to university students in Coimbra to assess their perceptions of the proposed strategies and to deepen understanding of the mobility practices, preferences, and expectations of the academic community. Including this demographic will broaden the empirical scope of the research and enhance representativeness, particularly regarding young adults and daily institutional commuters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.R., J.M. and M.G.; methodology, J.G.; software, J.G.; validation, J.G., A.R. and J.M.; formal analysis, J.G.; investigation, J.G.; resources, A.R. and M.G.; data curation, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, A.R., J.M. and M.G.; visualisation, J.G.; supervision, M.G.; project administration, A.R. and M.G.; funding acquisition, A.R. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The ENTROPY project was jointly developed by the Transport Research Centre of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (TRANSyT) and the University of Extremadura. This research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MCIU) through the 2022 call for “Proyectos de Generación de Conocimiento”, grant number PID2022-138120OB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union (FEDER).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not include any clinical intervention, did not collect sensitive personal data, and did not involve vulnerable groups. Under the University of Coimbra’s institutional framework and in accordance with standard practice for this type of non-clinical, non-sensitive social research, formal IRB or Ethics Committee approval is not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Atlas.ti 25 for the purposes of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEI | Spanish State Research Agency |

| BRT | Bus Rapid Transit |

| CITTA | Research Centre for Territory, Transport and Environment |

| EU | European Union |

| FEDER | European Regional Development Fund |

| FG | Focus Group |

| INESCC | Institute for Systems Engineering and Computers of Coimbra |

| MaaS | Mobility as a Service |

| MCIU | Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Spain) |

| P&R | Park and Ride |

| PT | Public Transport |

| TOD | Transit-Oriented Development |

| TRANSyT | Transport Research Centre, Technical University of Madrid |

| UC | University of Coimbra |

| UEx | University of Extremadura |

| UPM | Technical University of Madrid |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Second-Phase Voting by Focus Group 1 (Stakeholders)

| Focus Group 1 | Education Sector 1 | Local Association | Local Authority | Private Sector | Regional Authorities 1 | Regional Authorities 2 |

| Represents | ||||||

| Pedestrian-only zones | ||||||

| Integration with public transport | ||||||

| Pedestrian connectivity | ||||||

| Cycling infrastructure | ||||||

| New facilities | ||||||

| Low-emission zones |

Appendix A.2. Second-Phase Voting by Focus Group 2 (Stakeholders)

| Focus Group 2 | Education Sector 2 | Regional Authorities 3 | Regional Authorities 4 | Transport 1 | Health Sector | Education Sector 3 | Transport 2 |

| Represents | |||||||

| Pedestrian-only zones | |||||||

| Integration with public transport | |||||||

| Pedestrian connectivity | |||||||

| Cycling infrastructure | |||||||

| New facilities | |||||||

| Low-emission zones |

Appendix A.3. Second-Phase Voting by Focus Group 3 (Citizens)

| Focus Group 3 | Citizen 1 | Citizen 2 | Citizen 3 | Citizen 4 | Citizen 5 |

| Represents | |||||

| Pedestrian-only zones | |||||

| Integration with public transport | |||||

| Pedestrian connectivity | |||||

| Cycling infrastructure | |||||

| New facilities | |||||

| Low-emission zones |

References

- Kakar, K.A.; Prasad, C.S.R.K. Impact of Urban Sprawl on Travel Demand for Public Transport, Private Transport and Walking. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, D. The sustainable mobility paradigm. Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K. Transport and social exclusion: Where are we now? Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Scheurer, J. Performance measures for public transport accessibility: Learning from international practice. J. Transp. Land Use 2017, 10, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Transport and Environment Report 2021; EEA Report; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022-Mitigation of Climate Change-Working Group III; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.; Sousa, N.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J.; Natividade-Jesus, E. Challenges Ahead for Sustainable Cities: An Urban Form and Transport System Review. Energies 2024, 17, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Scheurer, J. Planning for sustainable accessibility: Developing tools to aid discussion and decision-making. Prog. Plan. 2010, 74, 53–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargarzadeh, M.; Ribeiro, A.S.N. Urban Suitability for Active Transportation: A Case Study from Coimbra, Portugal. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follador, D.; Tremblay-Racicot, F.; Duarte, F.; Carrier, M. Collaborative Governance in Urban Planning: Patterns of Interaction in Curitiba and Montreal. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 04020056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehl, A.; Chen, Y.; Sanabria-Véaz, K.; Uttal, D.; Stathopoulos, A. Where does active travel fit within local community narratives of mobility space and place? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 123, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Solá, A.; Vilhelmson, B. Negotiating Proximity in Sustainable Urban Planning: A Swedish Case. Sustainability 2018, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legacy, C. Is there a crisis of participatory planning? Plan. Theory 2017, 16, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Evaluating Transportation Equity: Guidance for Incorporating Distributional Impacts in Transport Planning. ITE J. (Inst. Transp. Eng.) 2022, 92, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, K. Transport Justice: Designing Fair Transportation Systems; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 9780415638319. [Google Scholar]

- Cascajo, R.; Lopez, E.; Herrero, F.; Monzon, A. User perception of transfers in multimodal urban trips: A qualitative study. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 13, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M. Mobility justice. In Handbook of Research Methods and Applications for Mobilities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the ‘15-minute city’: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Renne, J.L.; Bertolini, L. Transit Oriented Development: Making it Happen; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamargianni, M.; Li, W.; Matyas, M.; Schäfer, A. A Critical Review of New Mobility Services for Urban Transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 3294–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Merino, J.; Coloma, J.F.; García, M.; Monzon, A. The Unsustainable Proximity Paradox in Medium-Sized Cities: A Qualitative Study on User Perceptions of Mobility Policies. Land 2025, 14, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]