Assessment of Urban Size-Fractionated PM Down to PM0.1 Influenced by Daytime and Nighttime Open Biomass Fires in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

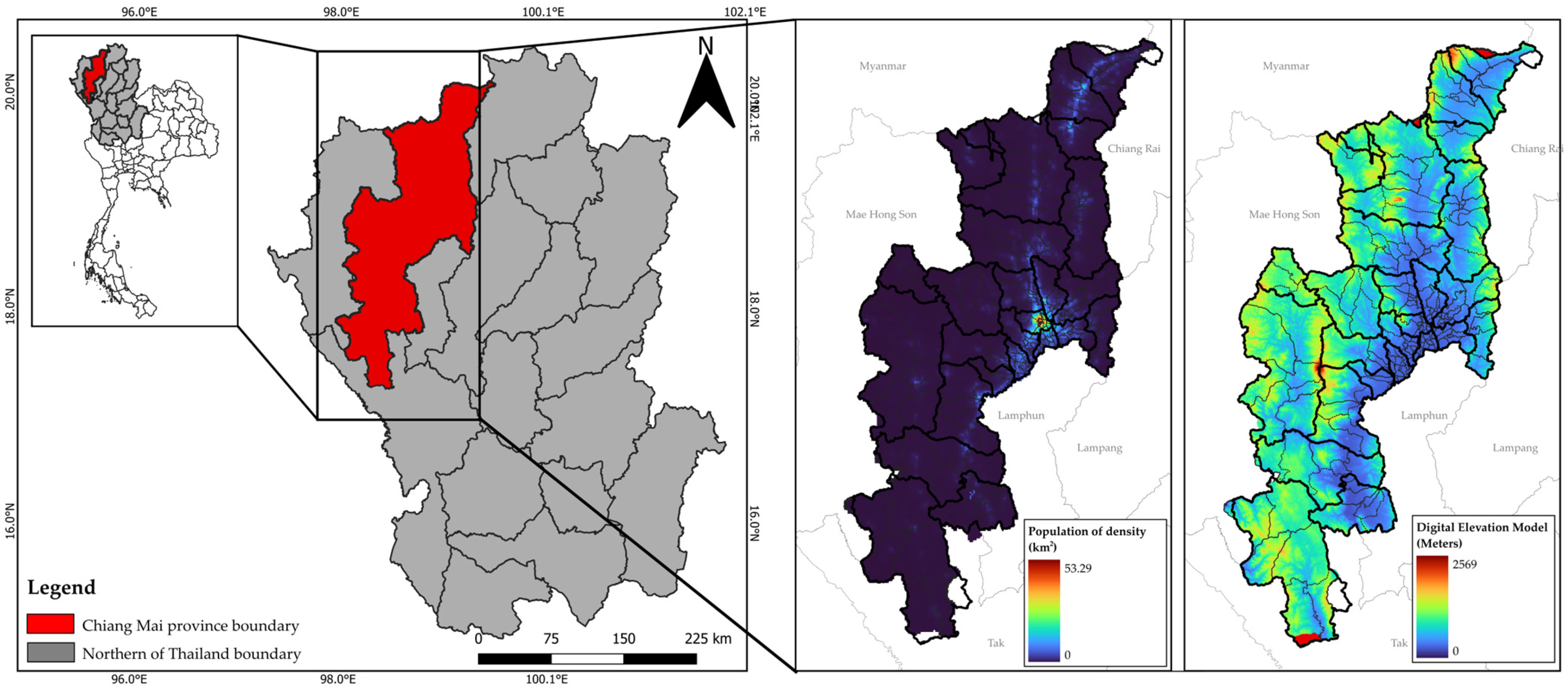

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Data

2.2.2. Land Use and Land Cover

2.2.3. Meteorological Data and Air Mass Movement

2.3. Sampling Description

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fire Hotspots in Chiang Mai, Thailand

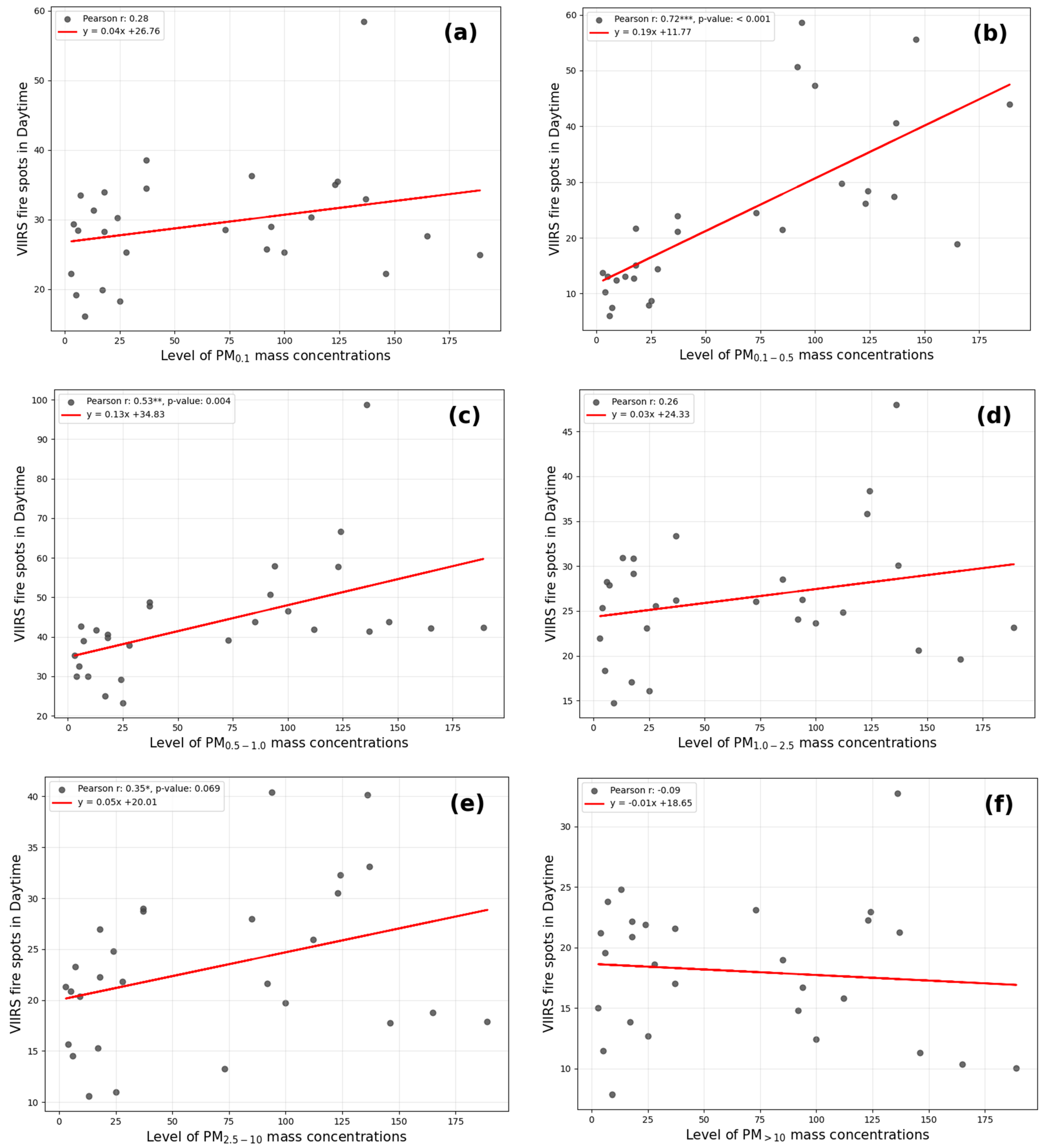

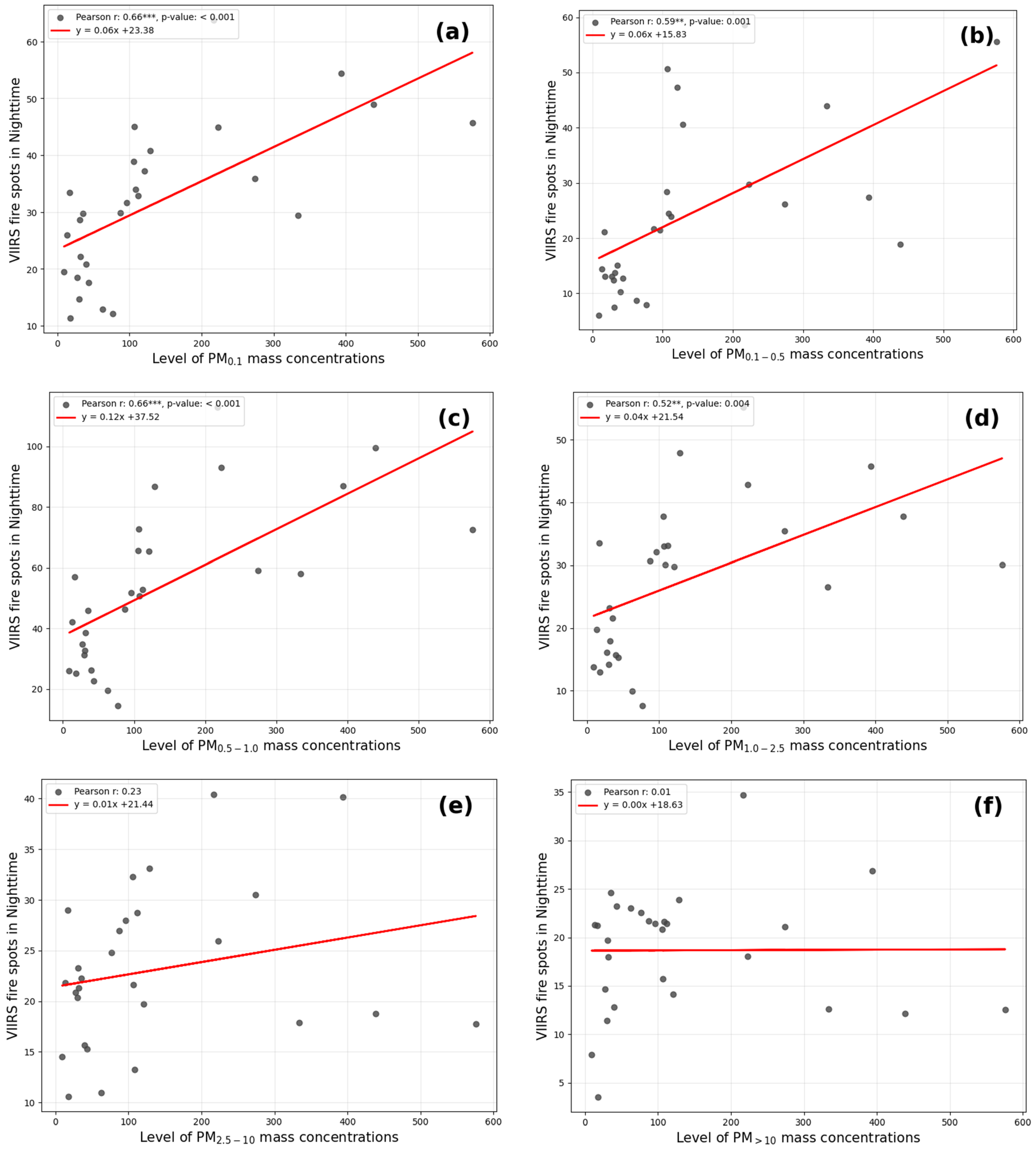

3.2. Particulate Matter and Fire Hotspots

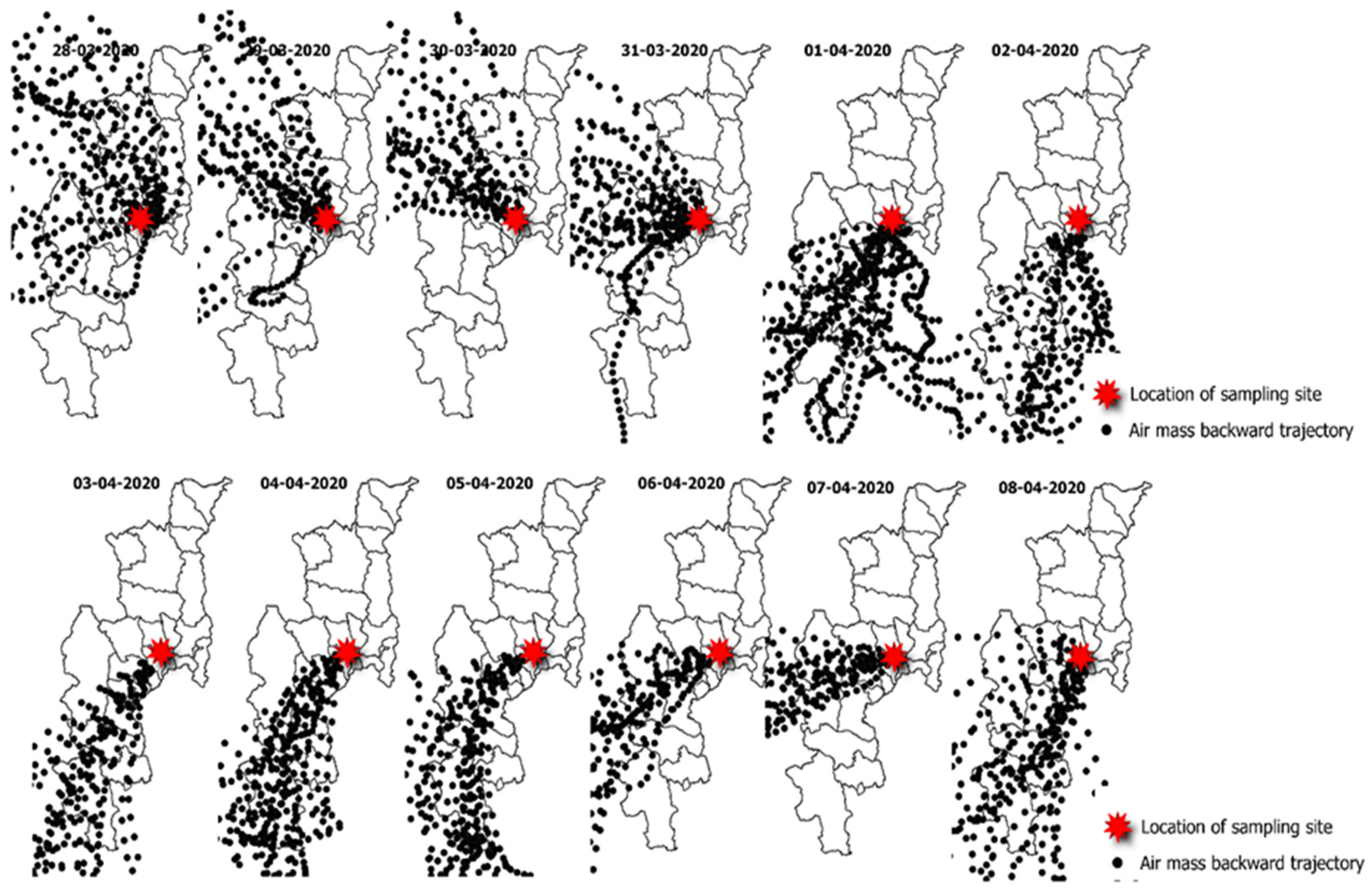

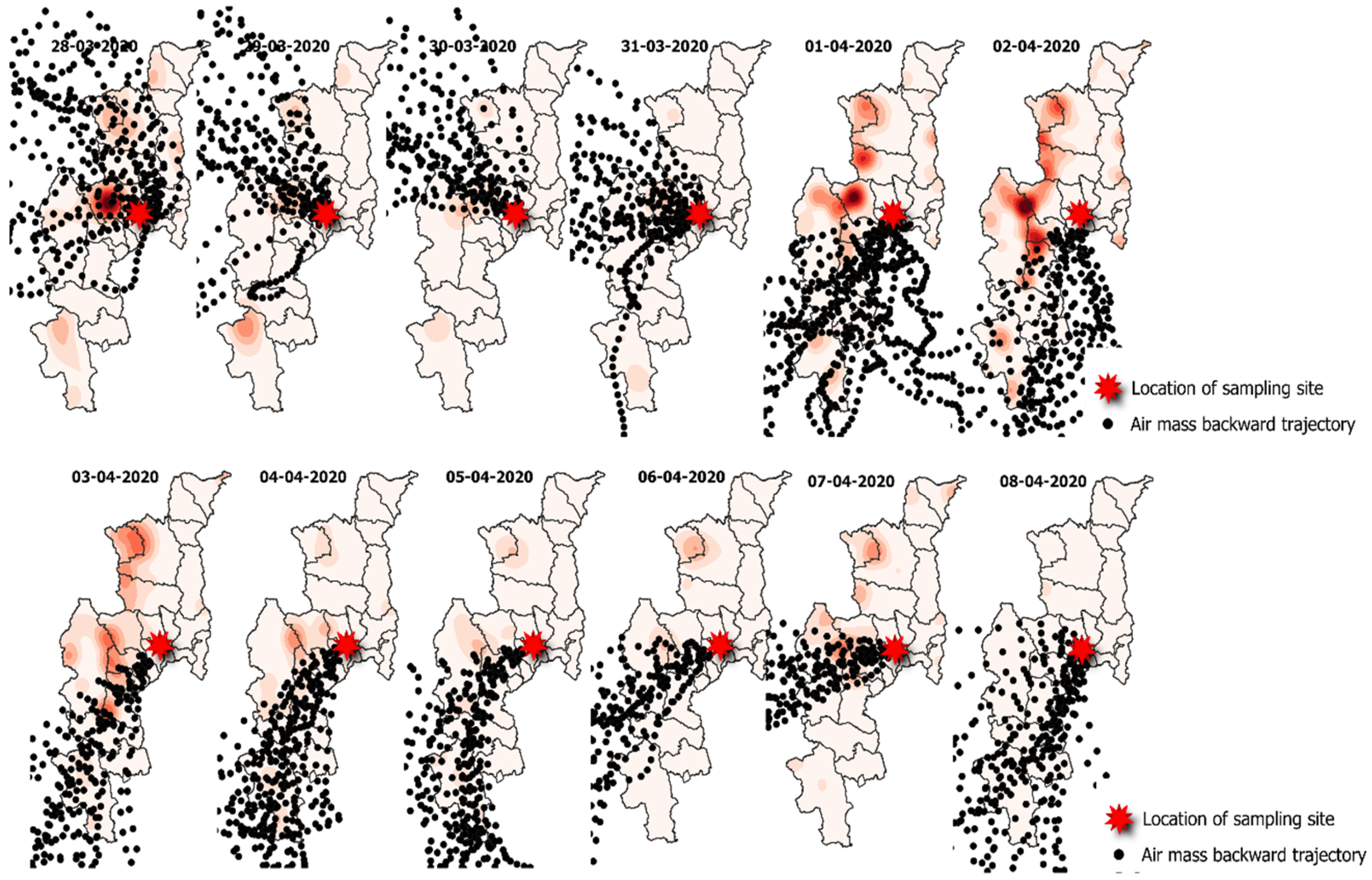

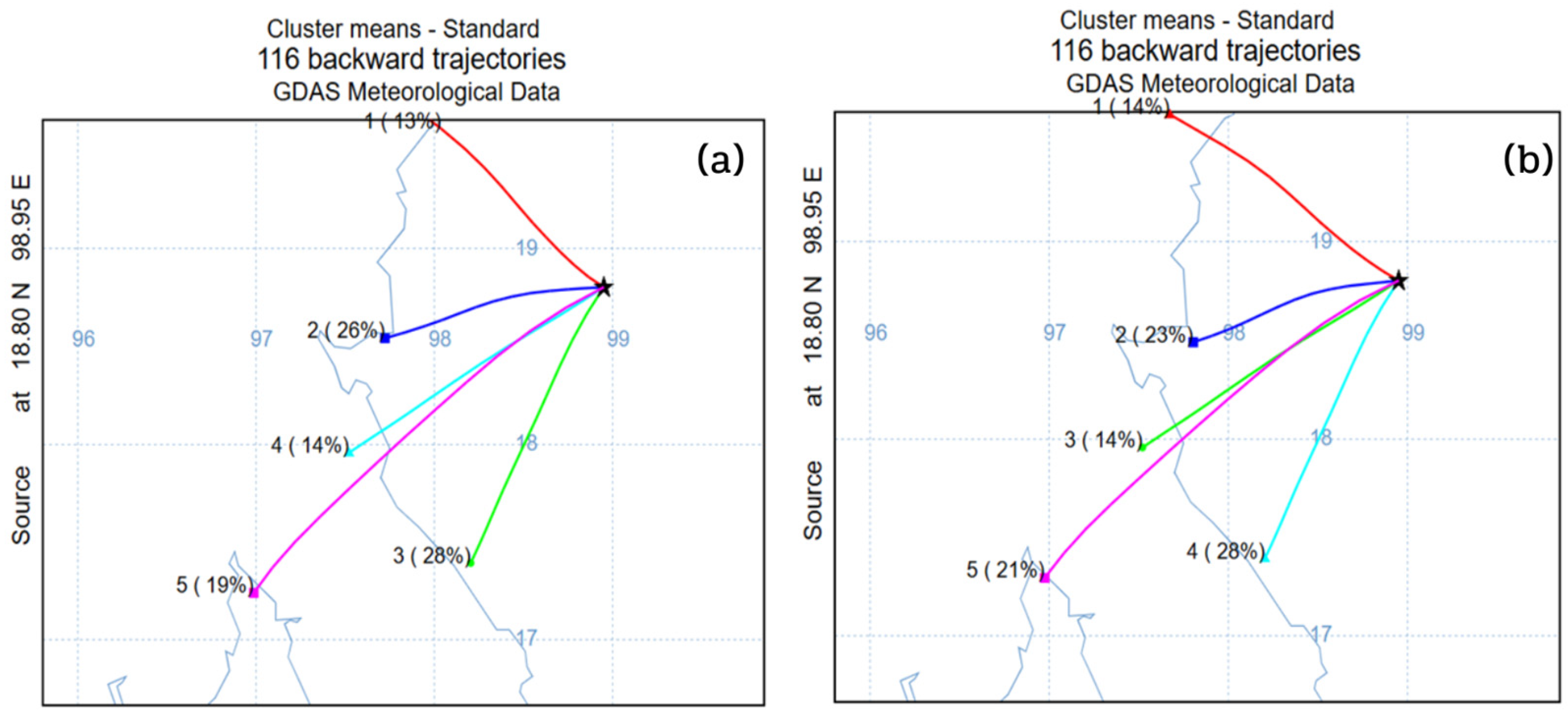

3.3. Influence of Wind and Air Mass Movement

3.3.1. Influence of Wind

3.3.2. Influence of Air Mass Movement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Adam, M.G.; Tran, P.T.M.; Bolan, N.; Balasubramanian, R. Biomass burning-derived airborne particulate matter in Southeast Asia: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, F.; Rauber, M.; Santijitpakdee, T.; Kawichai, S.; Prapamontol, T.; Szidat, S.; Zhang, Y.-L. Biomass Burning Greatly Enhances the Concentration of Fine Carbonaceous Aerosols at an Urban Area in Upper Northern Thailand: Evidence from the Radiocarbon-Based Source Apportionment on Size-Resolved Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punsompong, P.; Pani, S.K.; Wang, S.-H.; Bich Pham, T.T. Assessment of biomass-burning types and transport over Thailand and the associated health risks. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 247, 118176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh Thao, N.N.; Pimonsree, S.; Prueksakorn, K.; Bich Thao, P.T.; Vongruang, P. Public health and economic impact assessment of PM2.5 from open biomass burning over countries in mainland Southeast Asia during the smog episode. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanana, I.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, L.; Kulshreshtha, S.; Kumar, S.; Patel, S.K.S. Combustion and Stubble Burning: A Major Concern for the Environment and Human Health. Fire 2023, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavi, I. Wildfires in Grasslands and Shrublands: A Review of Impacts on Vegetation, Soil, Hydrology, and Geomorphology. Water 2019, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z. Air Pollution and Global Warming: History, Science, and Solutions, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Myllyntaus, T.; Hares, M.; Kunnas, J. Sustainability in Danger? Slash-and-Burn Cultivation in Nineteenth-Century Finland and Twentieth-Century Southeast Asia. Environ. Hist. 2022, 7, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyommaneerat, W. Enhancing Local Capability toward Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management: Case Study of Nan Municipality, Thailand. Rep. Grant-Support. Res. Asahi Glass Found. 2022, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasko, K.; Vadrevu, K.P.; Tran, V.T.; Ellicott, E.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Bui, H.Q.; Justice, C. Satellites may underestimate rice residue and associated burning emissions in Vietnam. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 085006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanabkaew, T.; Kim Oanh, N.T. Development of Spatial and Temporal Emission Inventory for Crop Residue Field Burning. Environ. Model. Assess. 2011, 16, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promkhambut, A.; Yokying, P.; Woods, K.; Fisher, M.; Li Yong, M.; Manorom, K.; Baird, I.G.; Fox, J. Rethinking agrarian transition in Southeast Asia through rice farming in Thailand. World Dev. 2023, 169, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Huang, Q.; Yang, D.; Yang, Y.; Xie, G.; Yang, S.; Liang, C.; Qin, Z. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Open Biomass Burning in Guangxi Province, China, from 2012 to 2023 Based on VIIRS. Fire 2024, 7, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappier-Brinton, T.; Lehman, S.M. The burning island: Spatiotemporal patterns of fire occurrence in Madagascar. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, N.R.; Ahmad, F.; Goparaju, L.; Choudhury, P.; Qayum, A.; Rizvi, J. Forest fire in Thailand: Spatio-temporal distribution and future risk assessment. Nat. Hazards Res. 2024, 4, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phairuang, W.; Suwattiga, P.; Chetiyanukornkul, T.; Hongtieab, S.; Limpaseni, W.; Ikemori, F.; Hata, M.; Furuuchi, M. The influence of the open burning of agricultural biomass and forest fires in Thailand on the carbonaceous components in size-fractionated particles. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongruang, P.; Pimonsree, S. Biomass burning sources and their contributions to PM10 concentrations over countries in mainland Southeast Asia during a smog episode. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 228, 117414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinakana, S.D.; Raysoni, A.U.; Sayeed, A.; Gonzalez, J.L.; Temby, O.; Wladyka, D.; Sepielak, K.; Gupta, P. Review of agricultural biomass burning and its impact on air quality in the continental United States of America. Environ. Adv. 2024, 16, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phairuang, W.; Chetiyanukornkul, T.; Suriyawong, P.; Amin, M.; Hata, M.; Furuuchi, M.; Yamazaki, M.; Gotoh, N.; Furusho, H.; Yurtsever, A.; et al. Characterizing Chemical, Environmental, and Stimulated Subcellular Physical Characteristics of Size-Fractionated PMs Down to PM0.1. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 12368–12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, M.; Miura, M.; Xiao, Y. Influence of biomass burning on local air pollution in mainland Southeast Asia from 2001 to 2016. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuthammachot, N.; Phairuang, W.; Stratoulias, D. Estimation of Carbon Emission in the Ex-Mega Rice Project, Indonesia Based on Sar Satellite Images. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 2489–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.A.M.; Amaral, S.S.; Soares Neto, T.G.; Cardoso, A.A.; Santos, J.C.; Souza, M.L.; Carvalho, J.A., Jr. Forest Fires in the Brazilian Amazon and their Effects on Particulate Matter Concentration, Size Distribution, and Chemical Composition. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2023, 195, 3045–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Lai, A.; Dongmei, C.; Chunlin, L.; Carmieli, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Rudich, Y. Secondary Organic Aerosol Generated from Biomass Burning Emitted Phenolic Compounds: Oxidative Potential, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Cytotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 8194–8206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.; Prajati, G.; Humairoh, G.P.; Putri, R.M.; Phairuang, W.; Hata, M.; Furuuchi, M. Characterization of size-fractionated carbonaceous particles in the small to nano-size range in Batam city, Indonesia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarbarzin, A.; Zinchuk, A.; Wellman, A.; Labarca, G.; Vena, D.; Gell, L.; Messineo, L.; White, D.P.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Redline, S.; et al. Cardiovascular Benefit of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Adults with Coronary Artery Disease and Obstructive Sleep Apnea without Excessive Sleepiness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelen, M.; Toro Campos, R.A.; Veldink, J.H.; Visser, A.E.; Hoek, G.; Brunekreef, B.; van der Kooi, A.J.; de Visser, M.; Raaphorst, J.; van den Berg, L.H.; et al. Long-Term Air Pollution Exposure and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Netherlands: A Population-based Case-control Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 097023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlwein, S.; Kappeler, R.; Kutlar Joss, M.; Künzli, N.; Hoffmann, B. Health effects of ultrafine particles: A systematic literature review update of epidemiological evidence. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraufnagel, D.E. The health effects of ultrafine particles. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardthaisong, L.; Sin-ampol, P.; Suwanprasit, C.; Charoenpanyanet, A. Haze Pollution in Chiang Mai, Thailand: A Road to Resilience. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.D.; Straka, W.; Mills, S.P.; Elvidge, C.D.; Lee, T.F.; Solbrig, J.; Walther, A.; Heidinger, A.K.; Weiss, S.C. Illuminating the Capabilities of the Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (NPP) Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Day/Night Band. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6717–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskuner, K. Assessing the performance of MODIS and VIIRS active fire products in the monitoring of wildfires: A case study in Turkey. iFor.—Biogeosci. For. 2022, 15, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvidge, C.D.; Zhizhin, M.; Hsu, F.-C.; Baugh, K.E. VIIRS Nightfire: Satellite Pyrometry at Night. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4423–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Bergeron, Y.; Valeria, O.; Chavardès, R.D.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J. Fire Detection and Fire Radiative Power in Forests and Low-Biomass Lands in Northeast Asia: MODIS versus VIIRS Fire Products. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Kondragunta, S.; Csiszar, I. Comparison of Fire Radiative Power Estimates From VIIRS and MODIS Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 4545–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Blackburn, G.A.; Onojeghuo, A.O.; Dash, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Atkinson, P.M. Fusion of Landsat 8 OLI and Sentinel-2 MSI Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 3885–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.E.D.; Picoli, M.C.A.; Sanches, I.D. Recent Applications of Landsat 8/OLI and Sentinel-2/MSI for Land Use and Land Cover Mapping: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inlaung, K.; Chotamonsak, C.; Macatangay, R.; Surapipith, V. Assessment of Transboundary PM2.5 from Biomass Burning in Northern Thailand Using the WRF-Chem Model. Toxics 2024, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.; Latif, M.T.; Hamid, H.H.A.; Uning, R.; Khumsaeng, T.; Phairuang, W.; Daud, Z.; Idris, J.; Sofwan, N.M.; Lung, S.-C.C. Spatial–temporal variability and health impact of particulate matter during a 2019–2020 biomass burning event in Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuuchi, M.; Eryu, K.; Nagura, M.; Hata, M.; Kato, T.; Tajima, N.; Sekiguchi, K.; Ehara, K.; Seto, T.; Otani, Y. Development and Performance Evaluation of Air Sampler with Inertial Filter for Nanoparticle Sampling. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2010, 10, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskiy, N.V.; Kirienko, V.A. Forest Fuel Drying, Pyrolysis and Ignition Processes during Forest Fire: A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, N.; Yebra, M.; Boer, M.M.; Griebel, A.; Nolan, R.H. A Review of Leaf-Level Flammability Traits in Eucalypt Trees. Fire 2024, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro dos Santos, D.; de Oliveira, A.M.; Duarte, E.S.F.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Menezes, L.S.; Albuquerque, R.; Roque, F.d.O.; Peres, L.F.; Hoelzemann, J.J.; Libonati, R. Compound dry-hot-fire events connecting Central and Southeastern South America: An unapparent and deadly ripple effect. NPJ Nat. Hazards 2024, 1, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, N.; Manomaiphiboon, K.; Pala-En, N.; Devkota, B.; Inerb, M.; Kokkaew, E. A Study of Urban Haze and Its Association with Cold Surge and Sea Breeze for Greater Bangkok. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barmpoutis, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. A Review on Early Forest Fire Detection Systems Using Optical Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phoo, W.W.; Manomaiphiboon, K.; Jaroonrattanapak, N.; Yodcum, J.; Sarinnapakorn, K.; Bonnet, S.; Aman, N.; Junpen, A.; Devkota, B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Fire activity and fire weather in a Lower Mekong subregion: Association, regional calibration, weather–adjusted trends, and policy implications. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 13259–13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunhawong, K.; Chaisan, T.; Rungmekarat, S.; Khotavivattana, S. Sugar Industry and Utilization of Its By-Products in Thailand: An Overview. Sugar Tech 2018, 20, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inlaung, K.; Chotamonsak, C.; Surapipith, V.; Macatangay, R. Relationship of Fire Hotspot, PM2.5 Concentrations, and Surrounding Areas in Upper Northern Thailand: A Case Study of Haze Season in 2019. J. King Mongkut’s Univ. Technol. North Bangk. 2022, 33, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan Bran, S.; Macatangay, R.; Chotamonsak, C.; Chantara, S.; Surapipith, V. Understanding the seasonal dynamics of surface PM2.5 mass distribution and source contributions over Thailand. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 331, 120613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Huang, G.; Piao, J.; Chotamonsak, C. Temporal and spatial variation of the transitional climate zone in summer during 1961–2018. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritong-aon, C.; Thomya, J.; Kertpromphan, C.; Phosri, A. Estimated effects of meteorological factors and fire hotspots on ambient particulate matter in the northern region of Thailand. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2021, 14, 1857–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Paluang, P.; Chetiyanukornkul, T.; Suriyawong, P.; Furuuchi, M.; Phairuang, W. Assessment of Urban Size-Fractionated PM Down to PM0.1 Influenced by Daytime and Nighttime Open Biomass Fires in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020103

Paluang P, Chetiyanukornkul T, Suriyawong P, Furuuchi M, Phairuang W. Assessment of Urban Size-Fractionated PM Down to PM0.1 Influenced by Daytime and Nighttime Open Biomass Fires in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. Urban Science. 2026; 10(2):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020103

Chicago/Turabian StylePaluang, Phakphum, Thaneeya Chetiyanukornkul, Phuchiwan Suriyawong, Masami Furuuchi, and Worradorn Phairuang. 2026. "Assessment of Urban Size-Fractionated PM Down to PM0.1 Influenced by Daytime and Nighttime Open Biomass Fires in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand" Urban Science 10, no. 2: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020103

APA StylePaluang, P., Chetiyanukornkul, T., Suriyawong, P., Furuuchi, M., & Phairuang, W. (2026). Assessment of Urban Size-Fractionated PM Down to PM0.1 Influenced by Daytime and Nighttime Open Biomass Fires in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. Urban Science, 10(2), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020103