Abstract

Understanding urban deprivation and its impact on health is crucial for addressing inequalities in cities. Using Quito as a case study, we developed a census-based socioeconomic urban deprivation index and analyzed three health outcomes: fatal injuries, COVID-19 deaths, and maternal mortality. Spatial patterns were examined using Local Moran’s I, and regression analyses included OLS, spatial lag, spatial error, and GWR models, applied at two spatial scales, census sectors and census zones, with deprivation as the independent variable. Most of the regression models indicated that deprivation does not explain health outcomes, with the exception of fatal injuries and COVID-19 deaths at the census zone scale when spatial error models are applied. Our results also revealed MAUP effects, as spatial patterns and associations between the studied variables vary depending on spatial scale. Spatial models improved explanatory power compared to OLS, uncovering spatial dependence and heterogeneity in the relationships between deprivation and health outcomes. Our findings underscore the importance of multiscale and spatially explicit approaches in urban health research and provide actionable evidence for targeted interventions and urban planning that account for both local and structural patterns of deprivation.

1. Introduction

Deprivation indices have been widely used to represent social, economic and material disadvantages [1] and their impact on health outcomes [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The study of deprivation focuses on the fundamental unmet needs of populations [9]. Deprivation measures may vary depending on policy, geographic, social, and temporal frameworks [10] and are expressed at the area level, reflecting the socioeconomic environments or context that influence the well-being and health of individuals or populations [11].

A deprivation index is a multidimensional measure, composed of several indicators. The earliest experience in calculating a multidimensional measure was the Townsend index, which included four indicators: unemployment, lack of car ownership, lack of home ownership, and household overcrowding [1,12]. Diverse indices have been developed in recent decades, mainly in countries of the Northern Hemisphere. For instance, in the UK, the Carstairs deprivation index was composed of indicators such as overcrowding, male unemployment, low social class, and lack of car ownership [13]. Also in the UK, the Jarman index, also known as the Under-Privileged Area score, which was calculated using eight indicators, was used to assess the workload of physicians and define their remuneration [14,15]. Another index, the UK index of multiple deprivation, used the domains of income, employment, health, education, housing, and access [16]. In France, principal components analysis was applied to define indicators for a deprivation index useful for the analysis of health inequalities and urban and social planning [17].

Deprivation indices for health planning in Canada have been calculated [4,18], as well as place-specific and GIS-based socioeconomic deprivation indices [19,20]. In the US, a small-area deprivation index based on census socioeconomic indicators was identified as a good predictor of chronic disease burden [21], and a social deprivation index has been found to be associated with cognitive decline both in the US [22] and in Europe [23]. In China, deprivation indices included indicators from the domains of education, income, employment, and housing services [7,8]. In Latin America, specifically in Ecuador, deprivation indices constructed through multicriteria analyses or statistical procedures have been found to impact area-level and individual-level urban health and quality of life [2,11,24]. Additionally, ref. [25] developed a taxonomy of deprivation indices and grouped them into four types: socioeconomic, material, environmental, and multidimensional. Most of the indices were categorized as socioeconomic.

While classical definitions of deprivation focus on unmet material needs and multidimensional disadvantages, there are theoretical perspectives that highlight that deprivation is also about individual freedoms and opportunities. For instance, Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach shifts the focus from income or resources to the substantive freedoms people have, where the capability of a person refers to the substantive freedom to attain a particular way of life, incorporating valued functionings such as being healthy, being educated, and participating in society [26]. Martha Nussbaum builds on Sen’s framework by proposing a set of central human capabilities that should be protected to ensure justice and human development [27]. On this matter [28] explains that deprivation encompasses not only material dimensions but also symbolic aspects related to how individuals are recognized by society, while ref. [29] emphasizes that measures of deprivation need to be appropriate in cultural and social terms.

In terms of methodological aspects, ref. [30] argues that measuring inequality can involve considering properties of the social welfare function beyond traditional measures such as the Gini coefficient. Along these lines, ref. [31] proposes that, since deprivation is a multifaceted phenomenon, it should be assessed through appropriate indicators that are not solely based on income. Recent research also highlights innovative empirical and methodological approaches to measuring deprivation. For instance, ref. [32] presents a fuzzy perspective to capture the vagueness of the multidimensional nature of deprivation. In a similar vein, ref. [33] proposes an innovative approach to assessing poverty by applying two fuzzy methods, the fuzzy hierarchical analysis (FHA) and the fuzzy technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (FTOPSIS) while also incorporating a temporal dimension that reflects people’s perceptions of the past, present, and future. Likewise, ref. [34] evaluates differences in a three-dimensional housing deprivation measure between urban and rural areas, and ref. [35] employs a multi-criteria decision-making technique to measure deprivation in European Union countries, thereby expanding the possibilities for investigating deprivation from local to global perspectives.

Deprivation in urban contexts has important implications for the health of residents, and deprivation values measured at small-area levels may vary depending on the geographical extent and degree of urbanization of the study area [36]. For instance, ref. [37] identified an excess risk of mortality associated with material deprivation, while also noting that higher levels of urbanization tend to mitigate the impact of deprivation for most causes of death. Similarly, ref. [38] found higher excess mortality in districts with low socioeconomic status, except in the case of colorectal cancer, which showed higher rates in more advantaged urban areas. When analyzing standardized mortality ratios and deprivation values in urban units, ref. [39] observed that, although inequalities may decrease over time, deprivation remains associated with premature mortality. These findings highlight the need for deprivation to be continuously evaluated and reassessed in urban areas to more effectively address socioeconomic and health inequalities. More broadly, from a territorial perspective, measures used to assess population standards of living should be spatially explicit and adaptable to different regional contexts [40].

The interpretations of results regarding associations between urban deprivation and health-related factors may vary depending on the spatial scale of analysis. Additionally, spatial dependence and spatial heterogeneity are two fundamental aspects of any spatial analysis. Spatial dependence refers to the effect of distance, encompassing notions of relative location, whereas spatial heterogeneity refers to the non-uniformity of spatial effects [41]. Ref. [42] found marked differences in values of deprivation indices and differences in deprivation–health relationships between different scales of analysis. This problem is known as the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) [43]. The MAUP may occur when smaller spatial units are aggregated at a different scale (scale effect of the MAUP) or when, at the same scale, alternative spatial units are used (zoning effect of the MAUP) [43,44,45,46]. These effects can lead to incorrect interpretations of spatial patterns and relationships. Because census data and most health data are available only in aggregated form, MAUP can alter and distort the understanding of the relationship between deprivation and health. However, the effects of MAUP do not always profoundly affect this understanding. For instance, it has been found that there are no severe MAUP effects when evaluating the influence of areal-level deprivation on individual-level perceived health-related measures [11,24]. Nevertheless, ecological fallacy can arise due to aggregation effects of spatial units, and these effects may depend on the number of areas as well as the structure of the underlying data, such as the intra-area homogeneity of the variances of the analyzed variable [47].

Despite the growing body of research on urban deprivation and health inequalities, most studies have focused on cities in the Global North. This study addresses this gap by presenting a census-based index of socioeconomic deprivation for Quito, providing both an empirical tool and theoretical insights into urban inequalities in underrepresented contexts. Furthermore, by analyzing deprivation and health-related outcomes at two spatial scales, the study contributes to the theoretical discourse on the MAUP, a topic that has received limited attention in urban planning research in Latin America.

One concern of this study is to provide empirical measures of deprivation for cities such as Quito, situating these findings within a spatial approach. Another central concern is theoretical, specifically, the MAUP. A third concern is spatial dependence, where the value of an outcome in one spatial unit may be influenced by values in neighboring units. In this sense, this study is motivated by three main problems: 1. the limited evidence on deprivation–health relationships in Latin American cities, despite their marked socioeconomic and spatial inequalities, 2. the risk of misleading conclusions when analyses of deprivation–health relationships ignore the MAUP and spatial dependence, and 3. the lack of updated, small-area measures of deprivation in Quito, which could inform equity-oriented urban planning and provide guidance for comparable cities.

In this context, we formulate three research hypotheses: 1. socioeconomic deprivation is associated with adverse health outcomes (fatal injuries, maternal mortality, and COVID-19 mortality), 2. the significance of these associations and spatial pattens of deprivation and the health outcomes vary depending on the spatial scale of analysis, reflecting MAUP effects, and 3. accounting for spatial dependence improves the explanatory capacity of deprivation to explain adverse health outcomes.

The objectives of this investigation are threefold. First, we aim to update and refine an index of socioeconomic deprivation for Quito [24] using recent census data, thereby not only generating an empirical tool for the study of urban inequalities but also contributing to the theoretical discourse by presenting a deprivation index in the context of a city in the Global South, where such indices are far less developed compared to the Global North. Second, we aim to analyze the spatial patterns of deprivation and health outcomes (fatal injuries, COVID-19 deaths, and maternal mortality), contributing to the understanding of MAUP by showing how patterns of inequality vary across different scales of analysis. Third, we aim to evaluate statistical and spatial associations between deprivation and health outcomes through regression models that account for spatial dependence and heterogeneity, further advancing theoretical debates on the MAUP as well as on the spatially contingent nature of sociospatial inequalities in health.

2. Materials and Methods

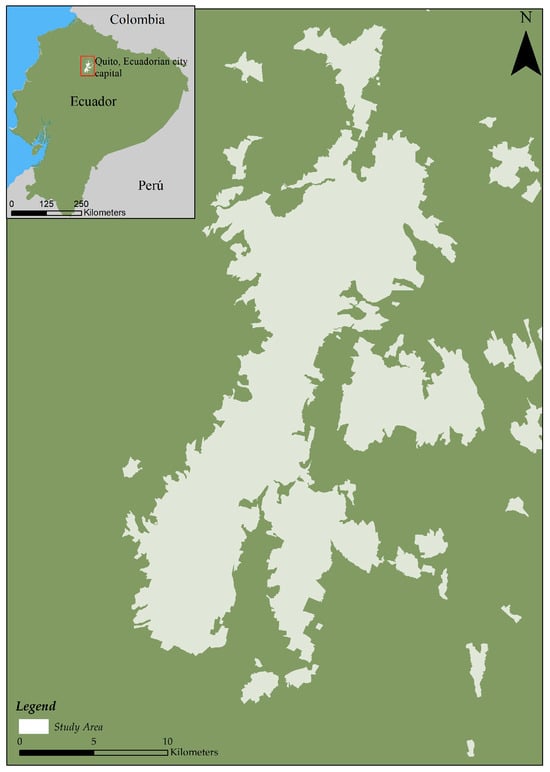

This study was carried out in Quito, the capital city of Ecuador (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study area.

Quito is home to around 3 million people [48]. In general, the city has adequate accessibility to different urban services. However, like many Latin American cities, Quito exhibits strong spatial and socioeconomic inequalities [24]. It is important to assess the impact of socioeconomic deprivation on health in Quito, as understanding how these disparities affect health outcomes is crucial for equity-oriented urban planning and for designing targeted interventions. Moreover, because Quito is representative of many Andean and Latin American cities, findings from this case study could inform broader discussions on urban health in the Global South. Quito’s colonial origins and subsequent urban expansion established a spatial pattern of segregation between wealthier central areas and more marginalized peripheral zones. Since the mid-20th century, Quito has undergone rapid demographic and spatial expansion fueled by rural-to-urban migration. Since the 1990s, Quito has experienced metropolitan-scale growth, with urban areas expanding into rural territories. As a result, the city is no longer limited to a long, narrow urban corridor at high altitude but also includes other urban zones adjacent to and surrounding this core area. The quantitative evaluation of socioeconomic inequalities can be carried out using indices calculated for statistical spatial units. In Ecuador, census-based information can be expressed at two spatial scales: census sectors and census zones. The census sector is the smallest census unit, while a census zone is composed of multiple census sectors. In the study area there are 6456 census sectors and 715 census zones.

At both scales, census sectors and census zones, we calculated an updated version of the deprivation index for the city of Quito, as presented by [24], and index that has been applied and validated to evaluate socioeconomic inequalities associated with health and quality of life. The indicators used to calculate the index were extracted from the 2022 Ecuadorian Population and Housing Census [48]. Table 1 lists the indicators included in the deprivation index.

Table 1.

Indicators of the deprivation index.

A min–max normalization was applied to the indicators, and multicollinearities were evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIFs). To calculate the weights of the indicators, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), as indicated by [49], was applied. Key steps in this PCA approach include normalizing the squared rotated component matrix and deriving a vector as a function of the highest values of the components of this matrix for each indicator. The Bartlett test of sphericity yielded a p-value lower than 0.05. The null hypothesis of this test assumes that the indicators are uncorrelated. A p-value lower than 0.05 supports the rejection of the null hypothesis, indicating that the indicators share sufficient correlation to justify the use of PCA. The obtained weights were re-scaled to sum to one. Table 2 shows the indicators along with their weights.

Table 2.

Weights of the indicators of the deprivation index for both scales of analysis.

Each indicator was multiplied by its corresponding weight, and the deprivation index was calculated as the sum of these weighted indicators:

where is the weight of indicator and is the normalized value of indicator . Here, denotes the number of indicators used. The deprivation index was computed at both the census sector and the census zone scales.

The health outcomes considered in this study are those included in the 2022 Ecuadorian Population and Housing Census. The advantages of using census-based health outcomes are that they are expressed at the same scale as the calculated deprivation indices and capture a wide range of health issues. The health outcomes included in the census are: (1) the count of violent deaths, suicides, and accidental deaths (the census does not provide separate information for these categories), (2) the count of deaths due to COVID-19, and (3) maternal mortality. The variable of violent deaths, suicides and accidental deaths can be considered a measure of injury mortality [50,51]. Socioeconomic measures at the geographical level (such as deprivation indices) can be linked to aggregate injury (intentional and unintentional) mortality outcomes [50]. To simplify terminology, in this study we refer to this variable as fatal injuries. COVID-19 deaths and fatal injuries can be measured in terms of the number of events, as census areas are designed to be as homogeneous as possible in terms of population.

We calculated local spatial autocorrelation using local Moran’s I. Moran’s I is the most widely used measure of local spatial autocorrelation, and its results are highly intuitive to identify positive and negative spatial autocorrelations. This measure can be expressed as [52,53]:

where is the value of variable at location , is the average value of (in the sample ), is the variance of , represents the values of at neighboring locations of , and represents the weights matrix between location and . This metric was applied to both the deprivation index and the health outcomes.

Four types of regression models were calculated. The first type of regression applied was the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model. OLS models produce the best linear unbiased estimates and are relatively robust against violations of homoscedasticity and normality of residuals. The OLS regression model can be expressed as [54]:

where is the dependent variable (the health outcome), is the intercept of the model, is the independent variable or covariate (the deprivation index), is the coefficient of the independent variable, and is the error term, which represents the residuals of the regression. If represents the predicted value of for the th observation, the th residual is the difference between and [55]. Because a linear regression model is constructed to minimize the sum of squared residuals, it is also called the OLS regression model [56].

The second and third types of regressions applied were the spatial lag regression and the spatial error regression. The choice between these models depends on the results of the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) tests for lag and error, obtained by applying a spatial weights matrix to the OLS regression. Spatial lag and spatial error models capture spatial spillovers of the dependent variable, correct for spatial autocorrelation in the residuals, and can provide less biased and more efficient estimates of regression coefficients.

The spatial weights matrix used was a queen-type contiguity matrix, which considers as neighbors those spatial units that share a border or a vertex. This type of contiguity is more inclusive than other forms, helping to avoid the isolation of spatial units of real-world datasets (such as census units) that may only touch others at a single point. A significant p-value in the LM lag test indicates the need to apply a spatial lag regression, while a significant p-value in the LM error test indicates the need to apply a spatial error regression.

The spatial lag regression model can be expressed as [57]:

where is the spatial autoregressive parameter of the dependent variable, and is the spatial weights matrix.

The spatial error regression model is expressed as [57]:

where is the spatial weights matrix, is the spatial autoregressive parameter of the error term, and represents an independent and identically distributed error term.

The fourth type of regression applied was Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR). GWR is a powerful tool for exploring spatial heterogeneity in the relationships between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. GWR enables the detection of spatially varying associations that may be obscured in traditional regression models. Unlike global models, GWR provides a local perspective, estimating coefficients at each location within the study area [58]:

where the coefficients are estimated at each location , and the term is a normally distributed random error with mean zero and constant variance. The GWR model was calibrated using a Gaussian kernel, and an optimal bandwidth of 51 was selected based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc), which offers an appropriate balance between model fit and parsimony, ensuring robustness and transparency in the estimation process.

3. Results

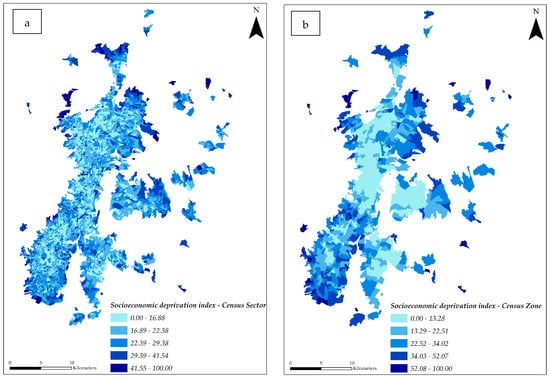

Figure 2 shows (a) the deprivation index at the census sector level and (b) the deprivation index at the census zone level. Higher deprivation is observed in the peripheral areas of the city, as well as in certain central areas, particularly the historic downtown, and in the southern part of the city. Lower deprivation values are concentrated in well-established urban areas, especially in the center-north and northern parts of the city, as well as in the eastern zones of recent urban expansion.

Figure 2.

Deprivation index: (a) census sectors and (b) census zones.

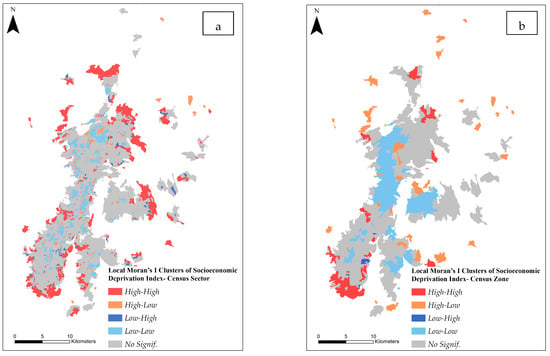

Figure 3 presents the results of the Local Moran’s I for the deprivation index at both the census sector and census zone levels. Most deprivation hotspots are observed in the urban peripheries, particularly in the outer northern and southern parts of the city. Coldspots of deprivation are located in well-established urban areas, especially in the center and northern parts of the city. This pattern is more pronounced at the census zone scale, where large coldspots are evident in the center, north, and some eastern zones, corresponding to the wealthiest areas of Quito. Several sectors and zones in the center and north exhibit negative spatial associations of the high–low type (areas of high deprivation surrounded by areas of low deprivation), highlighting pronounced urban socioeconomic inequalities.

Figure 3.

Local Moran’s I of the deprivation index: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

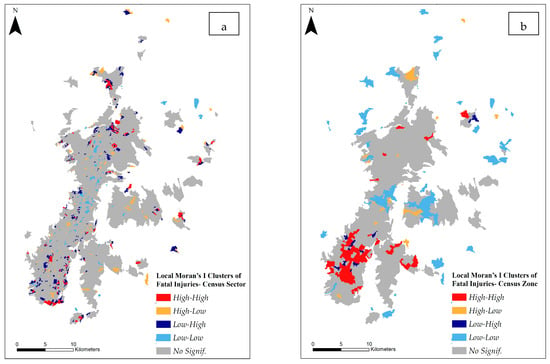

Figure 4 presents the results of the Local Moran’s I for fatal injury deaths at both the census sector and census zone levels. At both scales, several hotspots are visible, particularly in the southern part of Quito, where they overlap with areas of higher deprivation. However, negative spatial autocorrelations of the low–high type (areas with low numbers of fatal injuries surrounded by areas with high numbers) and the high–low type (areas with high numbers of fatal injuries surrounded by areas with low numbers) also appear across the city. These patterns suggest that fatal injuries are not uniformly clustered throughout Quito.

Figure 4.

Local Moran’s I of fatal injuries: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

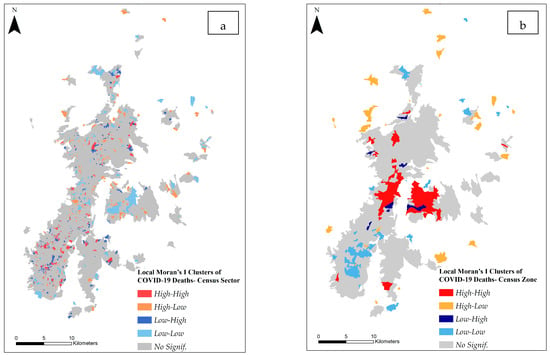

Figure 5 presents the results of the Local Moran’s I for COVID-19 deaths at both the census sector and census zone scales. At the census sector scale, hotspots are concentrated in the southern part of the city, whereas at the census zone scale, hotspots are observed in the center and east. This variation highlights the presence of the MAUP, where aggregation from sectors to zones generates scale effects that substantially alter the Moran’s I outcomes. Despite these differences, high–low patterns of COVID-19 deaths persist in certain areas of the north and east of Quito at both scales.

Figure 5.

Local Moran’s I of COVID-19 deaths: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

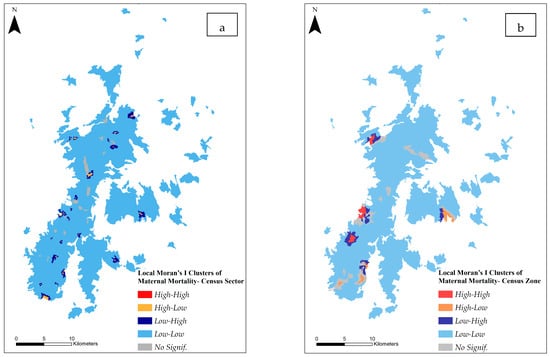

Figure 6 presents the Local Moran’s I for maternal mortality at both the census sector and census zone scales. Most of the city is a coldspot of maternal mortality. Evidence of the MAUP emerges for this variable: at the census zone scale, distinct hotspots are concentrated in the west of the city, whereas at the census sector scale, the same area reveals coldspots and high–low/low–high patterns. These high–low/low–high patterns are also observed in the south and east of the study area across both scales of analysis.

Figure 6.

Local Moran’s I of maternal mortality: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

Table 3 presents the results of the OLS regressions at both the census sector and census zone scales.

Table 3.

Results of the OLS regressions.

At the census sector level, with fatal injuries as the dependent variable, deprivation was statistically significant (p-value = 0.000), although the R2 was extremely low. The Jarque–Bera and Breusch–Pagan tests indicated non-normality and heteroscedasticity of the residuals (p-values = 0.000). In addition, the Lagrange Multiplier tests suggested the applicability of both spatial lag and spatial error regression models (p-values = 0.000).

At the census zone level, deprivation was statistically significantly associated with fatal injuries (p-value = 0.002), although the model explains only a minimal portion of the variation in this health outcome (R2 = 0.014). The residuals exhibited non-normality (Jarque–Bera test, p-value = 0.000), whereas the Breusch–Pagan test indicated homoscedasticity (p-value = 0.131). Lagrange Multiplier tests suggested that both spatial lag and spatial error regressions were appropriate for this model (p-values = 0.000).

At the census sector level, deprivation was not significantly associated with COVID-19 deaths (p-value = 0.143). The R2 indicates that the model explains virtually none of the variation in the outcome. The residuals exhibited non-normality (Jarque–Bera test, p-value = 0.000) and homoscedasticity (Breusch–Pagan test, p-value = 0.960). Lagrange Multiplier tests indicated that both spatial lag and spatial error regressions were applicable (p-values = 0.000).

At the census zone scale, deprivation was not associated with COVID-19 deaths (p-value = 0.521). Residuals exhibited non-normality and heteroscedasticity (Jarque–Bera and Breusch–Pagan tests, p-value = 0.000). Lagrange Multiplier tests indicated that both spatial lag and spatial error regressions could be applied (p-values = 0.000).

At the census sector level, deprivation was marginally associated with maternal mortality at a 90% confidence level (p-value = 0.051). However, the model exhibits no explanatory power, as it does not explain any of the variation in maternal mortality (R2 = 0.000). Residuals exhibited non-normality and heteroscedasticity (Jarque–Bera and Breusch–Pagan tests, p-value = 0.000). Lagrange Multiplier tests for both lag (p-value = 0.107) and error (p-value = 0.105) were not significant, indicating no spatial dependence in the dependent variable or in the regression errors.

At the census zone level, maternal mortality was not associated with deprivation (p-value = 0.400). Residuals showed non-normality (Jarque–Bera test, p = 0.000) and homoscedasticity (Breusch–Pagan test, p-value = 0.551). Lagrange Multiplier tests for both spatial lag and spatial error were significant (p-values = 0.000), indicating that spatial lag and spatial error regression models can be applied for this association.

Table 4 presents the results of spatial lag and spatial error models. At the census sector level, for the dependent variable fatal injuries, the spatial autoregressive term (in the spatial lag model) was highly significant (p-value = 0.000), and the autoregressive error term was also highly significant (p-value = 0.004). Deprivation was also significant. Nevertheless, the R2 was minimal (R2 = 0.012). For COVID-19 deaths, both the spatial lag term and the spatial autoregressive error term were highly significant (p-values = 0.000). At the census sector scale, there was no need to estimate spatial lag or spatial error models for maternal mortality because, as previously mentioned, the OLS models yielded non-significant Lagrange Multiplier tests (lag and error).

Table 4.

Results of the spatial lag and spatial error regressions. is the spatial autoregressive (lag) term of the dependent variable. is the spatial autoregressive error term.

At the census zone scale, for the dependent variable fatal injuries, the spatial autoregressive (spatial lag) term was highly significant (p-value = 0.000), and the autoregressive error term was also highly significant (p-value = 0.000). Deprivation was found to be significant in the spatial error model. For the models that account for spatial dependence (spatial lag and spatial error), deprivation explains 27% of the variation in fatal injuries. In the case of COVID-19 deaths, the spatial regressions showed highly significant spatial dependence in both the dependent variable and the errors (p-values = 0.000). When using the spatial error model, deprivation is also significant (p-value = 0.006), and the model’s predictive power improves: deprivation explains 23% of the variation in COVID-19 deaths. For maternal mortality, spatial dependence was also highly significant (p-values = 0.000), and accounting for this dependence in the spatial lag and spatial error models increased the R2 to 0.375. However, in these models, deprivation is not significant. Overall, the models that exhibited the highest R2 were those at the census zone level: the spatial lag and spatial error models for fatal injuries, the spatial error model for COVID-19 deaths, and the spatial lag and spatial error models for maternal mortality. In contrast, the models at the census sector level show extremely low R2 values.

The results of the GWR models should be interpreted not for prediction, but for exploring spatial heterogeneities in the relationship between deprivation and the health outcomes. Table 5 summarizes the results of the GWRs. The models at the census zone scale exhibit better performance (lower AIC) and higher global R2 values than those at the census sector scale.

Table 5.

Results of the GWRs.

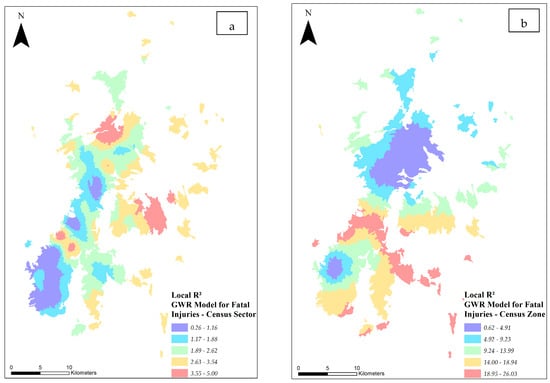

Figure 7 depicts the GWR results for fatal injuries as the dependent variable. R2 values are expressed in percentage (%). There is clear spatial variation in the association between deprivation and fatal injuries, and this variation differs across the two scales of analysis. For example, at the census sector scale, larger areas with lower local R2 values are observed in the south of Quito, whereas at the census zone scale, larger areas with lower values are found in the north. The highest local R2 for this association is 26%, occurring at the census zone scale.

Figure 7.

GWR results for fatal injuries as the dependent variable: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

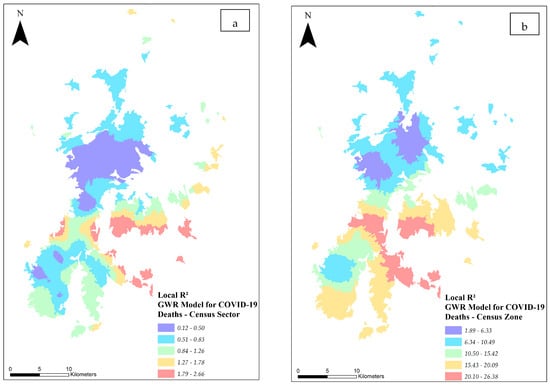

Figure 8 shows the GWR results for COVID-19 deaths as the dependent variable. R2 values are expressed in percentage (%). The association between deprivation and COVID-19 deaths exhibits clear spatial variation. Higher local R2 values are observed in the central areas of Quito at both scales, census sectors and census zones, while lower values occur in the northern part of the city. The highest local R2 for this association is 26%, observed at the census zone scale.

Figure 8.

GWR results for COVID-19 deaths as the dependent variable: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

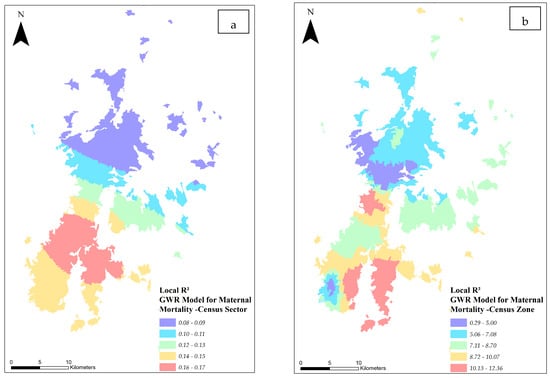

Figure 9 shows the GWR results for maternal mortality as the dependent variable. R2 values are expressed in percentage (%). The association between deprivation and maternal mortality exhibits spatial heterogeneity. Higher local R2 values are observed in the central and southern areas of Quito at both scales (census sectors and census zones) while lower values occur in the northern part of the city. The highest local R2 for this association is 12%, found at the census zone scale.

Figure 9.

GWR results for maternal mortality as the dependent variable: (a) census sector scale and (b) census zone scale.

4. Discussion

Spatial patterns of deprivation and health outcomes vary depending on the scale of analysis. Two notable variations can be identified: first, some hotspots of deprivation observed at the census sector level disappear at the census zone level; second, at the census zone level, large hotspots of fatal injuries, COVID-19 deaths, and maternal mortality emerge that are not apparent at the census sector level.

These variations are classical manifestations of the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) and align with observations made in previous studies [42,59,60]. For example, [59] found that deprivation measures and their correlation with cardiovascular disease vary across different scales, while [60] determined that, at the county level, low rates of late-stage breast cancer masked high rates at the census tract level. Additionally, these authors observed that, when applying global Moran’s I, both the index values and their significance decrease as the size of the spatial units increases. However, unlike [60], we did not limit the spatial autocorrelation assessment to a global index; instead, we applied local Moran’s I to identify local spatial patterns. We found that high values of health outcomes at the census zone level (the larger spatial unit in this study, composed of census sectors) obscured low values of these factors at the census sector level.

The OLS models indicated that, in the study area and at both scales of analysis, fatal injuries could be associated with deprivation, although the models showed no explanatory power. In contrast, COVID-19 deaths were not associated with deprivation. Maternal mortality could be associated with deprivation at the census sector scale (although the model explained no variation in maternal mortality, as reflected in the R2) but not at the census zone scale. However, at the census zone scale, when spatial error dependence is taken into account, deprivation explains variations in fatal injuries and COVID-19 deaths. In contrast, deprivation does not explain maternal mortality under models that account for spatial dependence.

A lack of explanatory power despite statistically significant deprivation coefficients can have several interpretations, including truly small effects of deprivation, the omission of relevant independent variables, or the presence of non-linear relationships between the variables. Nevertheless, the obtained findings indicate the presence of MAUP in the relationship between deprivation and health outcomes. However, it is important to consider that [11,24] found that MAUP effects are minimal in practical terms when examining interactions between urban deprivation and individual-level health, and suggest that MAUP effects may also be limited in the case of associations between urban deprivation and area-level (geographical-level) health.

The observations of significant associations between fatal injuries and urban socioeconomic deprivation is consistent with the findings of [61], who reported socioeconomic differentials in all-cause mortality, including deaths from external causes, and with those of [51], who identified urban socioeconomic inequalities in all injury mortality at the small-area level in several European cities. Additionally, the results align with the study by [50], which found that neighborhood-level (census tract) socioeconomic characteristics influence injury mortality, including homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths.

Linking the results of the significant associations between fatal injuries and deprivation with the findings from the local Moran’s I analysis, where large hotspots of fatal injuries were identified at the census zone level, it can be observed that these hotspots are in the south of Quito, an area with higher levels of deprivation. Although the fatal injuries variable is a composite measure of injury mortality, the results obtained, together with evidence from other studies, suggest potential individual-level relationships between specific types of injury mortality and deprivation. For instance, ref. [62] found that higher deprivation is significantly associated with increased suicide rates.

As previously mentioned, OLS models indicated no association between urban socioeconomic deprivation and COVID-19 deaths at either scale of analysis. On the other hand, at the census zone scale, the spatial error model indicates that COVID-19 deaths could be explained by deprivation. The findings of OLS models contrast with studies such as [63], which observed a significant positive association between COVID-19 mortality and poverty, and [64], which found that socioeconomic deprivation, along with diabetes and obesity, was significantly associated with COVID-19 mortality. However, there is also evidence suggesting that deprivation is not necessarily linked to COVID-19. For instance, ref. [65] found no association between socioeconomic deprivation and severe forms of COVID-19, ref. [66] concluded that deprivation alone does not affect the COVID-19 fatality burden, and ref. [67] observed that poverty was not associated with higher COVID-19 mortality. Ref. [68] found that COVID-19 incidence was initially higher in wealthier sub-city units before spreading to lower-income areas, although inequities in testing and reporting may have affected more deprived neighborhoods. Collectively, these findings suggest that understanding the burden of COVID-19 requires consideration of a complex set of factors operating across multiple individual and areal scales. Moreover, the relationship between deprivation and epidemics is not static and may vary depending on spatial scale and spatial dependence.

In the OLS model for maternal mortality at the census sector scale, deprivation was statistically significant, but its effect was extremely weak, explaining virtually none of the variability in maternal mortality. The spatial lag and spatial error models showed no influence of deprivation on maternal mortality. These findings are not consistent with previous investigations showing that socioeconomic disadvantage increases the risk of maternal mortality [69], that lower income levels are linked to higher maternal death rates [70], and that maternal mortality inequalities are more pronounced among poorer women [71]. Furthermore, after adjusting for patient-level factors, ref. [72] found that residence in deprived neighborhoods may contribute to maternal morbidity and mortality. However, in the case of other types of non-violent mortality, some cities show that the most socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are not necessarily associated with the highest mortality rates [73], indicating that factors beyond socioeconomic conditions, such as environmental influences, can also affect mortality.

At both scales of analysis, we identified that fatal injuries and COVID-19 deaths in a spatial unit (census sector or census zone) are influenced by fatal injuries and COVID-19 deaths in adjacent units. This spatial dependency was also observed for maternal mortality, but only at the census zone level. These findings are consistent with previous studies: ref. [74], who applied spatial lag and spatial error models and found spatial dependencies in intentional and unintentional injuries; Ref. [75], who used spatial simultaneous autoregressive models and detected significant spatial autocorrelation in COVID-19 mortality; and ref. [76], who reported that spatial lag and spatial error effects should be considered when modeling maternal mortality. Taken together, these results underscore the need to address health inequalities at the neighborhood level, as interventions in one area may yield benefits that extend to surrounding communities.

In general, our study shows that when accounting for spatial effects, neighborhood spillovers of health outcomes become evident. Health-related issues can ‘spill over’ across neighborhoods and do not stop at administrative boundaries, implying that health-related structural inequalities need to be addressed at the city level. Moreover, incorporating these effects leads to more accurate inferences. At the census zone scale, models that account for spatial dependencies (spatial error models) showed that deprivation explained 27% of the variation in fatal injuries and 23% of the variation in COVID-19 deaths, thereby improving its predictive capacity for these outcomes. Similarly, at the census zone scale, local R2 values from the GWR models highlighted spatial heterogeneities in the relationships between deprivation and both fatal injuries and COVID-19 deaths. In central and southern Quito, local R2 values ranged between 14% and 26% for fatal injuries and between 15% and 26% for COVID-19 deaths, illustrating notable spatial variation in model fit across the city.

Previous studies have applied spatial regression to assess the impact of deprivation on health outcomes. For instance, ref. [77] used a spatial regression approach to capture the spatial heterogeneity of deprivation and found positive associations with both maternal and child mortality rates. Similarly, ref. [78] applied spatial regressions and concluded that housing deprivation is significantly associated with health outcomes such as cardiopathy and chronic pneumonia. However, these studies did not account for the spatial dependencies of health outcomes, nor did they adopt a multiscale approach to address the MAUP.

Our findings point to contextual mechanisms that help explain the observed variations across deprivation and health outcomes. In Quito, the proliferation of informal settlements and peripheral expansion have reinforced patterns of deprivation that are captured by our index. The association between deprivation and fatal injuries at both scales reflects structural vulnerabilities in deprived areas, such as unsafe working conditions, inadequate transport infrastructure, and limited access to emergency care, all of which increase the risk of injury-related mortality. Maternal mortality showed scale-dependent spatial patterns, a clear illustration of the MAUP. Hotspots of maternal mortality suggest persistent inequalities in reproductive health services and access to obstetric care, that may be exacerbated by low public investment in the health sector in Ecuador in recent years. Regarding COVID-19 deaths, the results suggest a more generalized exposure across socioeconomic groups in Quito (at the census zone scale). Combined with the presence of COVID-19 deaths in a given spatial unit being influenced by deaths in adjacent units, the findings may also indicate socio-ecological urban connections in the spread of the pandemic. Together, these explanations highlight the importance of considering local socioeconomic conditions, the health system, and the urban structure when interpreting how deprivation relates to different health outcomes.

This investigation has some limitations that also present opportunities for future research. The models are based on a single independent variable (the deprivation index), which may restrict their explanatory power. While this choice was deliberate (our interest was to explore the specific contribution of deprivation to health outcomes while accounting for scale and spatial dependence), it necessarily limits a more comprehensive understanding of the broader determinants of health. Furthermore, we did not consider individual-level variables, which could introduce ecological bias into the results due to potential within-group variability in both exposures and confounders [79]. Accordingly, our findings should be interpreted as reflecting area-level patterns rather than individual-level mechanisms. Potential drivers of the health outcomes examined in this study that were not included may involve sociodemographic variables such as gender and age; environmental variables such as air and water pollution; and factors related to accessibility to urban facilities, encompassing a wide range of venues and services (depending on the health outcome), from schools and hospitals to sports arenas and alcohol outlets. Future research could expand the models by incorporating additional diverse independent variables, which may also improve the predictive capacity of OLS models.

Our analyses were conducted only at relatively small scales (census sectors and census zones), but future work could also explore other spatial scales in Quito, such as administrative parishes. Additionally, the use of different parameters in spatial techniques may yield contrasting results. For example, applying a different type of spatial weights matrix (e.g., rook contiguity instead of queen contiguity) might change results in specific areas of the city, although overall spatial patterns may remain consistent. Future studies could therefore benefit from systematically comparing the effects of different spatial parameters and methodological choices on the observed associations.

Our study provides further insight into the relationships between deprivation and health outcomes in urban environments, offering compelling evidence of spatial heterogeneities and dependencies in health-related factors. It also contributes to further validation of a deprivation index that has already been applied in other investigations, demonstrating its usefulness for detecting socioeconomic inequalities and its potential applicability to other cities in the Global South, particularly in Latin America. Finally, our findings highlight the importance of accounting for scale-related issues, such as the MAUP, to better inform place-based decision-making in urban contexts

5. Conclusions

The study of urban socioeconomic deprivation and health-related factors such as fatal injuries, COVID-19 deaths, and maternal mortality is a fundamental concern for both public health and urban public policy. The results obtained both challenge and support our hypotheses. OLS models indicated that deprivation explains minimal variation in fatal injuries and does not explain any variation in COVID-19 deaths or maternal mortality. However, spatial error models at the census zone level indicated that deprivation explains variation in fatal injuries and COVID-19 deaths.

These findings also validate our second and third hypotheses: the significance of associations varies depending on the spatial scale, reflecting MAUP effects, and accounting for spatial dependence at the census zone level (where, for example, COVID-19 deaths in one sector can be influenced by deaths in neighboring sectors), through spatial lag and spatial error models improves the explanatory capacity of deprivation (R2). The spatial error model increased the explanatory power of deprivation for fatal injuries, yielding an R2 of 27%. The spatial error model also improved the predictive capacity of deprivation for COVID-19 deaths, resulting in an R2 of 23%. For maternal mortality, the spatial lag and spatial error models increased the R2 to 37%, although deprivation was not found to be significant. MAUP effects are further evident in the spatial patterns of the studied variables. For instance, hotspots of deprivation present at the census sector level disappear at the census zone level, and hotspots of maternal mortality observed at the census zone level disappear at the census sector level, with regression results differing accordingly between the two scales.

These results can support more effective public policy and urban planning in Quito by guiding targeted interventions and promoting a multiscale perspective to minimize the implications of MAUP. The findings of this study highlight several concrete policy directions. First, the deprivation index can serve as a spatial targeting tool to prioritize the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, particularly those identified as hotspots of deprivation and adverse health-related factors. Second, sector-specific interventions are needed, including expanding primary care and emergency obstetric services in deprived areas, improving road safety infrastructure, promoting violence-prevention initiatives, and enhancing community-level emergency response capacity for potential future epidemics. Third, the deprivation index should be integrated into broader urban and housing policies, guiding investments in infrastructure and public services to reduce segregation and barriers to accessing urban services, such as healthcare. Finally, MAUP should be considered in policy design: decision-makers need to recognize that associations between urban deprivation and health outcomes vary depending on geographic scale and incorporate analyses conducted at multiple levels to guide decisions ranging from fine-grained targeting to broader structural interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.-B.; methodology, G.F.-G. and P.C.-B.; software, G.F.-G. and P.C.-B.; validation, P.C.-B. and G.F.-G.; formal analysis, P.C.-B.; investigation, P.C.-B. and G.F.-G.; resources, G.F.-G.; data curation, G.F.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.-B.; writing—review and editing, P.C.-B.; visualization, G.F.-G.; supervision, P.C.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The open data used in this study were obtained from the following website: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/estadisticas/ (accessed on 11 December 2025). The processed datasets presented in this article are not publicly available, as they form part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Townsend, P. Deprivation. J. Soc. Policy 1987, 16, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Barona, P.; Murphy, T.; Kienberger, S.; Blaschke, T. A Multi-Criteria Spatial Deprivation Index to Support Health Inequality Analyses. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.J.; Gatrell, A.C.; Duke-Williams, O. Do Area-Level Population Change, Deprivation and Variations in Deprivation Affect Individual-Level Self-Reported Limiting Long-Term Illness? Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Raymond, G. A Deprivation Index for Health Planning in Canada. Chronic Dis. Can. 2009, 29, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knighton, A.J.; Savitz, L.; Belnap, T.; Stephenson, B.; VanDerslice, J. Introduction of an Area Deprivation Index Measuring Patient Socio-Economic Status in an Integrated Health System: Implications for Population Health. eGEMs (Gener. Evid. Methods Improv. Patient Outcomes) 2016, 4, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillini, R.; Vercelli, M. The Local Socio-Economic Health Deprivation Index: Methods and Results. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2018, 59, E3–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.Y.W. Development of a Contextualized Index of Multiple Deprivation for Age-Friendly Cities: Evidence from Hong Kong. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 167, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Law, C.-K.; Zhao, J.; Hui, A.Y.-K.; Yip, B.H.-K.; Yeoh, E.K.; Chung, R.Y.-N. Measuring Health-Related Social Deprivation in Small Areas: Development of an Index and Examination of Its Association with Cancer Mortality. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaume, E.; Pornet, C.; Dejardin, O.; Launay, L.; Lillini, R.; Vercelli, M.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Fernández Fontelo, A.; Borrell, C.; Ribeiro, A.I.; et al. Development of a Cross-Cultural Deprivation Index in Five European Countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrizi, E.; Mussida, C.; Parisi, M.L. Comparing Material and Social Deprivation Indicators: Identification of Deprived Populations. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Barona, P.; Blaschke, T.; Gaona, G. Deprivation, Healthcare Accessibility and Satisfaction: Geographical Context and Scale Implications. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2017, 11, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P.; Phillimore, P.; Beattie, A. Health and Deprivation. Inequality and the North; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs, V.; Morris, R. Deprivation: Explaining Differences in Mortality between Scotland and England and Wales. BMJ Br. Med. J. 1989, 299, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarman, B. Underprivileged Areas: Validation and Distribution of Scores. Br. Med. J. 1984, 289, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarman, B. Identification of Underprivileged Areas. Br. Med. J. 1983, 286, 1705–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niggebrugge, A.; Haynes, R.; Jones, A.; Lovett, A.; Harvey, I. The Index of Multiple Deprivation 2000 Access Domain: A Useful Indicator for Public Health? Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalloué, B.; Monnez, J.-M.; Padilla, C.; Kihal, W.; Le Meur, N.; Zmirou-Navier, D.; Deguen, S. A Statistical Procedure to Create a Neighborhood Socioeconomic Index for Health Inequalities Analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampalon, R.; Raymond, G. A Deprivation Index for Health and Welfare Planning in Quebec. Chronic Dis. Can. 2000, 21, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, N.; Schuurman, N.; Hayes, M. V Using GIS-Based Methods of Multicriteria Analysis to Construct Socio-Economic Deprivation Indices. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2007, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Schuurman, N.; Oliver, L.; Hayes, M. Towards the Construction of Place-Specific Measures of Deprivation: A Case Study from the Vancouver Metropolitan Area. Can. Geogr. Géographies Can. 2007, 51, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lòpez-De Fede, A.; Stewart, J.E.; Hardin, J.W.; Mayfield-Smith, K. Comparison of Small-Area Deprivation Measures as Predictors of Chronic Disease Burden in a Low-Income Population. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, L.M.; Rodriguez, F.S. Association of Social Deprivation with Cognitive Status and Decline in Older Adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofbauer, L.M.; Rodriguez, F.S. Validation of a Social Deprivation Index and Association with Cognitive Function and Decline in Older Adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Barona, P.; Wei, C.; Hagenlocher, M. Multiscale Evaluation of an Urban Deprivation Index: Implications for Quality of Life and Healthcare Accessibility Planning. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenina, A.; Shalnova, S.; Maksimov, S.; Drapkina, O. Classification of Deprivation Indices That Applied to Detect Health Inequality: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0385720274. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Capabilities as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice. Fem. Econ. 2003, 9, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, R. Poverty; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, D.; Nandy, S. Measuring Child Poverty and Deprivation. In Global Child Poverty and Well-Being: Measurement, Concepts, Policy and Action; Minujin, A., Nandy, S., Eds.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 57–102. ISBN 9781447301141. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, A.B. On the Measurement of Inequality. J. Econ. Theory 1970, 2, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, B.; Whelan, C.T. Poverty and Deprivation in Europe; Oxford University Press, 2011; ISBN 9780199588435. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, H.; Szczesny, W. Multidimensional Material Deprivation in Poland: A Focus on Changes in 2015–2017. Qual. Quant. 2021, 55, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. A Fuzzy Hybrid MCDM Approach to the Evaluation of Subjective Household Poverty. Stat. Transit. New Ser. 2025, 26, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, H.; Wojewódzka-Wiewiórska, A. Dimensions of Housing Deprivation in Poland: A Rural-Urban Perspective. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241293256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. Assessing the Level of the Material Deprivation of European Union Countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, M.; Chevrier, C.; Pelé, F.; Serrano-Chavez, T.; Cordier, S.; Viel, J.-F. Can a Deprivation Index Be Used Legitimately over Both Urban and Rural Areas? Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, P.; Costa, C.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Gotsens, M.; Borrell, C. Mortality, Material Deprivation and Urbanization: Exploring the Social Patterns of a Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aungkulanon, S.; Tangcharoensathien, V.; Shibuya, K.; Bundhamcharoen, K.; Chongsuvivatwong, V. Area-Level Socioeconomic Deprivation and Mortality Differentials in Thailand: Results from Principal Component Analysis and Cluster Analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, S.; Ivaldi, E.; Testi, A. Measuring Change Over Time in Socio-Economic Deprivation and Health in an Urban Context: The Case Study of Genoa. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139, 745–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Cermakova, K.; Kalinowski, S.; Hromada, E.; Mec, M. Measurement of Sustainable Development and Standard of Living in Territorial Units: Methodological Concept and Application. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 4604–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. The Scope of Spatial Econometrics. In Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models; Anselin, L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 7–15. ISBN 978-94-015-7799-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman, N.; Bell, N.; Dunn, J.R.; Oliver, L. Deprivation Indices, Population Health and Geography: An Evaluation of the Spatial Effectiveness of Indices at Multiple Scales. J. Urban Health 2007, 84, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Openshaw, S. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem—Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography; GeoBooks: Norwich, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Wong, D.W.S. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem in Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Sp. 1991, 23, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, D.J. The Scale Issue in the Social and Natural Sciences. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1999, 25, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, D. Scale, Aggregation, and the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem. In Handbook of Regional Science; Fischer, M.M., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3-642-36203-3. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D.; Steel, D.G.; Tranmer, M.; Wrigley, N. Aggregation and Ecological Effects in Geographically Based Data. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC Censo de Población y Vivienda 2022. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/estadisticas/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- OECD/European Union/EC-JRC Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008.

- Cubbin, C.; LeClere, F.B.; Smith, G.S. Socioeconomic Status and Injury Mortality: Individual and Neighbourhood Determinants. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotsens, M.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Pérez, K.; Palència, L.; Martinez-Beneito, M.-A.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Burström, B.; Costa, G.; Deboosere, P.; Domínguez-Berjón, F.; et al. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Injury Mortality in Small Areas of 15 European Cities. Health Place 2013, 24, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Luo, L.; Xu, W.; Ledwith, V. Use of Local Moran’s I and GIS to Identify Pollution Hotspots of Pb in Urban Soils of Galway, Ireland. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 398, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorathiya, A.; Saval, P.; Sorathiya, M. Data-Driven Sustainable Investment Strategies: Integrating ESG, Financial Data Science, and Time Series Analysis for Alpha Generation. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Taylor, J. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in Python; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-38746-3. [Google Scholar]

- Haslwanter, T. An Introduction to Statistics with Python: With Applications in the Life Sciences, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-97370-4. [Google Scholar]

- Darmofal, D. Spatial Analysis for the Social Sciences; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-521-71638-3. [Google Scholar]

- Krivoruchko, K. Spatial Statistical Data Analysis for GIS Users; ESRI Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrecos, A.; Domínguez-Berjón, M.F.; Duque, I.; Franco, M.; Escobar, F. Geographic and Statistic Stability of Deprivation Aggregated Measures at Different Spatial Units in Health Research. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 95, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanet, C.P.; Carlos, H.; Weiss, J.E.; Diaz, M.C.G.; Shi, X.; Onega, T.; Loehrer, A.P. Evaluating Geographic Health Disparities in Cancer Care: Example of the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 6987–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layte, R.; Banks, J. Socioeconomic Differentials in Mortality by Cause of Death in the Republic of Ireland, 1984–2008. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caswell, E.D.; Hartley, S.D.; Groth, C.P.; Christensen, M.; Bhandari, R. Socioeconomic Deprivation and Suicide in Appalachia: The Use of Three Socioeconomic Deprivation Indices to Explain County-Level Suicide Rates. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwumiju, A.S.; Oluwafemi, O.; Mohammed, Y.D.; Mobolaji, J.W. Geospatial Evaluation of COVID-19 Mortality: Influence of Socio-Economic Status and Underlying Health Conditions in Contiguous USA. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 141, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lome-Hurtado, A.; Soto-Pérez, M. Modelling the Joint Association of Socio-Economic Disadvantage, Diabetes, and Obesity on COVID-19 Mortality in Greater Mexico City. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, A.-L.; Vignes, D.; Sterpu, R.; Bussone, G.; Kansau, I.; Pignon, C.; Ben Ismail, R.; Favier, M.; Molitor, J.-L.; Braham, D.; et al. Factors Associated with Hospital Admission and Adverse Outcome for COVID-19: Role of Social Factors and Medical Care. Infect. Dis. Now 2022, 52, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, F.; Lillini, R.; Martinelli, D.; Iannelli, G.; Ascatigno, L.; Casanova, G.; Lopalco, P.L.; Prato, R. Association of Socio-Economic Deprivation with COVID-19 Incidence and Fatality during the First Wave of the Pandemic in Italy: Lessons Learned from a Local Register-Based Study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2023, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorregaray Farge, Z.E.; Soto Tarazona, A.; De La Cruz-Vargas, J.A. Correlation between Mortality Due to COVID-19, Wealth Index, Human Development and Population Density in Districts of Metropolitan Lima during 2020: Correlación Entre Mortalidad Por COVID-19, Índices de Riqueza y Desarrollo Humano y Densidad Poblacional En Distritos de Lima Metropolitana Durante El 2020. Rev. La Fac. Med. Humana 2021, 21, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, M.J.P.; Morales Caceres, A.; Dykstra, T.E.; Dayrell Ferreira Sales, A.; Caiaffa, W.T. Social Epidemiology of Urban COVID-19 Inequalities in Latin America and Canada. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddes-Barton, D.; Baldelli, S.; Karthikappallil, R.; Bentley, T.; Omorodion, B.; Thompson, L.; Roberts, N.W.; Goldacre, R.; Knight, M.; Ramakrishnan, R. Association between Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2025, 79, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.; Jang, S.-I.; Park, E.-C.; Nam, J.Y. The Effect of Socioeconomic Status on All-Cause Maternal Mortality: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borde, M.T. Geographical and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Maternal Mortality in Ethiopia. Int. J. Soc. Determ. Health Health Serv. 2023, 53, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipre, M.; Bolaji, B.; Blanchard, C.; Harrelson, A.; Szychowski, J.; Sinkey, R.; Julian, Z.; Tita, A.; Baskin, M.L. Relationship Between Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Severe Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality. Ethn. Dis. 2022, 32, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Villamizar, L.A.; Marín, D.; Piñeros-Jiménez, J.G.; Rojas-Sánchez, O.A.; Serrano-Lomelin, J.; Herrera, V. Intraurban Geographic and Socioeconomic Inequalities of Mortality in Four Cities in Colombia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, E.; Cusimano, M.D.; Bação, F.; Damásio, B.; Penfound, E. Open Data and Injuries in Urban Areas—A Spatial Analytical Framework of Toronto Using Machine Learning and Spatial Regressions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, S.; Shaman, J. Investigating Associations between COVID-19 Mortality and Population-Level Health and Socioeconomic Indicators in the United States: A Modeling Study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamkhezri, J.; Razzaghi, S.; Khezri, M.; Heshmati, A. Regional Effects of Maternal Mortality Determinants in Africa and the Middle East: How About Political Risks of Conflicts? Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 865903. [Google Scholar]

- You, H.; Zhou, D.; Wu, S.; Hu, X.; Bie, C. Social Deprivation and Rural Public Health in China: Exploring the Relationship Using Spatial Regression. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 147, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Su, S. Neighborhood Housing Deprivation and Public Health: Theoretical Linkage, Empirical Evidence, and Implications for Urban Planning. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J. Ecologic Studies Revisited. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.