Abstract

The current refugee crisis has revealed flaws in existing systems. Factors such as socioeconomic background, access to housing, and urban policies influence refugees’ abilities to fully participate in city life. The research objective is to analyze the interplay between housing access for adult refugees residing in Curitiba, Brazil, and the city’s targeted public policies and strategies for refugees. The research methodology adopts a case study approach centered on Curitiba, Brazil, with the city shown as a key destination for refugees in Brazil. This study combines qualitative and quantitative techniques, following a structured research protocol that guides the processes of data collection and analysis. The innovation and originality lie in offering a new perspective on how urban strategies intersect with the rights and inclusion of refugees, exploring the relationship between refugees’ housing access and its interconnection with the strategic digital city framework. The results highlight the importance of a multifaceted approach to addressing housing access challenges for refugees, which includes safeguarding their rights, promoting stability, integration, and ensuring their participation in shaping public policies. The conclusion outlines the urgent need to promote integration by reassessing housing affordability, ensuring access to services, engaging refugees in decision-making processes, and improving their social welfare.

1. Introduction

The global refugee crisis has exposed institutional shortcomings and heightened public expectations for improved support [1]. UN-Habitat projections indicate that by 2030, around 40% of the world’s population will require access to adequate housing. This demand translates into a need for 96,000 new affordable housing units daily [2]. Moreover, housing access is fundamental to ensuring opportunities in employment, education, healthcare, and social services [3,4,5,6]. Addressing the housing crisis requires governments at all levels to prioritize housing within urban policies, emphasizing human rights and sustainable development [7,8,9,10].

The research problems that portray the intersection of refugee management and digital urban governance are becoming increasingly relevant as forced displacement converges with rapid urbanization in the Global South [11].

In Latin America, Brazil stands as one of the principal host countries for refugees, reflecting both its historical role as a destination for migrants and its formal commitments to international protection frameworks [2,12]. Under Brazilian law, recognized refugees are granted access to documentation, education, employment, and other rights equivalent to those held by legally resident foreign nationals. As of June 2024, Brazil hosted over 790,000 forcibly displaced individuals under UNHCR’s mandate, including more than 144,000 officially recognized refugees. While the majority originated from Venezuela, significant numbers also arrived from Haiti, Cuba, Colombia, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Burkina Faso, and Mali [13].

Despite significant advancements in urban development, large segments of Brazil’s population continue to live in precarious or inadequate housing conditions, with some individuals facing total homelessness [12,14].

Many refugees often end up in informal settlements, facing precarious living conditions and inflated rents due to unfamiliarity with local systems and language barriers. These vulnerabilities leave refugees exposed to exploitation, harassment, discrimination, and violence [15,16,17,18].

Urban challenges in Brazil, such as the lack of effective public policies to provide adequate housing and infrastructure, have driven peripheral urbanization and perpetuated the issues of housing scarcity and limited access to urban services [19,20]. Such exclusion further restricts their access to the city and exacerbates their marginalization within Brazilian society. Despite significant efforts in city planning, systemic exclusion remains a pervasive issue, underscoring the gap between strategic intent and practical outcomes [19,20,21].

In parallel, the concept of the strategic digital city emphasizes the adoption of information technology to improve urban management. However, its implementation faces challenges such as limited citizen participation, unequal territorial distribution of benefits, and a lack of coherent technology use [22,23,24]. These challenges are particularly pronounced for marginalized groups like refugees, who often lack access to digital tools, education, or support systems that could enable meaningful participation. While strategies vary depending on local and global contexts, many countries, particularly in the Global South, face ongoing challenges of population marginalization in socioeconomic development [11,25].

Thus, the research question is as follows: how do public policies and city strategies influence access to housing for adult refugees in Curitiba, Brazil?

The research objective is to analyze the relationship between housing access for adult refugees residing in Curitiba, Brazil, and the city’s targeted public policies and strategies for refugees. To achieve this, the research seeks to analyze the situation of refugees in Curitiba by profiling their socioeconomic characteristics, including their demographics, origin, and geographic distribution, while also assessing the types of housing and access available to them. Additionally, this study evaluates how city strategies and public policies play an important role in affecting and offering housing access for refugees. In this way, the strategic digital city context is represented by the city strategies subproject.

Additionally, it is important to highlight that, in the literature investigated, housing transcends the physical dimension, being understood as a fundamental urban right that enables access to other social rights, such as health, education, work, and civic participation. In this way, social inclusion is understood because of expanded access to housing, acting as a vector for urban integration and citizenship for refugee populations. Therefore, it is an urban strategy that promotes cultural diversity in cities and is articulated with the principles of the strategic digital city (SDC) projects and urban studies. In this context, the concept and subprojects of SDC are introduced to the urban study as an analytical tool to understand how urban strategies enabled by public management influence access to housing for refugees. Thus, the SDC project allows for the identification of barriers, governance gaps, and inclusion opportunities that directly affect the realization of the right to the city and respective urban studies.

The research justifications, on the other hand, are demonstrated through the positive impacts of effective collaboration among the public, private, and government sectors. It also demonstrates how local governments play a pivotal role in planning, structuring, and managing urban territories to ensure adequate housing, urban quality of life, and social sustainability [25,26,27].

For refugees, true integration into democratic societies also requires the safeguarding of legal and political rights [16,28,29]. Public policies and civil society initiatives must be participatory and tailored to refugees’ specific needs, addressing their economic vulnerabilities while fostering full urban inclusion. These efforts should include housing programs, the development of basic infrastructure in refugee settlements, and urbanization initiatives in vulnerable areas [4,19,25].

Strategic approaches can foster collaborative innovation by promoting interaction between public management and citizens, leading to increased civic participation and the shaping of local public policies. Moreover, city strategies drive innovation and citizen participation, influencing local public policies while also recognizing the strategic and creative roles of local authorities [23,30,31], and they underscore the strategic significance digital cities have in terms of improving citizens’ life quality and city competitiveness, emphasizing the role of information technology in urban development [22,23].

Urban areas generally possess greater access to digital infrastructure, expertise, and financial resources, making them more capable of executing integration strategies [32]. For refugees, housing decisions involve more than choosing where to live; they also entail navigating a city’s digital landscape. Thus, having access to digital tools and platforms significantly impacts their ability to find housing, connect with communities, and access essential services [33].

This study advances urban studies by exposing a major empirical gap by documenting how Curitiba, which is celebrated as a model of innovative planning, lacks coherent housing strategies for refugees, revealing contradictions between global smart-city narratives and local governance realities in the Global South.

The research contributions also include a novel analytical model that integrates housing access, right to the city, and strategic digital city frameworks, linking socioeconomic refugee profiles with urban policy and digital governance variables, an approach not which has not previously been applied to refugee housing research. Furthermore, this research contributes to urban management by identifying mismatches between refugees’ residential patterns and the spatial concentration of support services, recommending decentralized service provision, institutional responsibility for housing, and inclusive digital infrastructures.

Unlike approaches centered on cities in the Global North, such as Berlin [34], Athens [35], or Canada [36], the discussion proposed here focuses on Curitiba, which was selected not for its size or refugee inflows alone but because it represents a paradox within the Brazilian urban context. Internationally praised for pioneering sustainable planning and smart-city strategies, Curitiba has no centralized refugee database, lacks dedicated housing programs for forcibly displaced populations, and exhibits fragmented institutional responsibilities [3,12,37]. The scarcity of centralized statistics and the fragmentation of information related to housing and integration underscore the scientific relevance of selecting Curitiba. In this way, this study recognizes the need for research that exposes these gaps and contributes to the improvement of local public policies, as proposed herein.

In addition, the concept of the strategic digital city, considered by [22,23] as a tool for contemporary urban management, is applied to the inclusion of vulnerable populations such as refugees. Theoretically, the research contributes to expanding discussions on urban governance. As such, the adopted approach is unprecedented in the literature on refugees, as it incorporates variables such as access to housing, civic participation, access to information, and urban strategies as structuring elements of the right to the city [22,23,24].

It is also worth noting that this study connects both local and international evidence, such as the situation of Venezuelan refugees in Brazil [1] and the experiences of Syrian refugee integration in Canada [36]. This articulation broadens the debate on urban justice and dignified housing, providing the basis for justifying the choice of Curitiba as the case study.

2. Literature Review

The Literature Review Section will delve deeper into the primary concepts underpinning this research. It will explore the definitions and lived experiences of refugees, the challenges they face in accessing housing, and broader urban rights frameworks, such as the right to the city. Furthermore, it will analyze the transformative potential of strategic digital cities and city strategies in fostering inclusive urban development. These interconnected themes will guide this study’s understanding of how urban policy and planning can address refugee integration and housing access within a technologically advanced and socially inclusive urban framework.

2.1. Refugees

This subsection establishes the foundational context for understanding the challenges refugees face in accessing housing, particularly in Curitiba, Brazil. Defining “refugees”, “immigrants,” and “internally displaced persons (IDPs)” is crucial for framing the broader socio-legal and human rights dimensions underpinning this research.

This literature review does not treat refugeehood as an abstract or humanitarian issue alone. Rather, it positions refugees as urban actors whose rights, recognition, and access to space are embedded within political and digital infrastructures.

A widely accepted refugee definition incorporates elements from the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol. This definition includes individuals who flee their countries due to threats to life, safety, or freedom arising from widespread violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive human rights violations, or other severe disruptions to public order. In some cases, refugees cannot remain in their initial country of refuge due to factors such as the persecutor’s presence across borders [38], the host state’s inability to protect them, or challenges related to integration, protection, or documentation [39,40].

While refugees cross international borders, internally displaced persons (IDPs) are forced from their homes by similar events, armed conflicts, natural disasters, or human rights violations, yet remain within their country. They may find temporary shelter in different regions or designated IDP camps. Unlike refugees, IDPs lack formal international recognition and legal protections [41,42].

Refugees often exist in a liminal space between their home and host countries, navigating the complexities of cultural adaptation and social integration. This intermediary position can marginalize them in terms of identity, culture, and social inclusion. Legal challenges also arise, as opting for refugee status in a host country, even temporarily, may limit their ability to fully exercise citizenship rights in their home country [27,29].

In the context of a strategic digital city, digital technologies can act as both tools of exclusion and avenues for inclusion. Refugees may use these technologies to organize, advocate for better housing, or create alternative housing networks [43,44].

Immigrants, on the other hand, are typically defined as individuals who move across borders, voluntarily or involuntarily, for economic, social, or environmental reasons [45]. The motivations can range from seeking better life opportunities to escaping structural poverty or violence. The Brazilian New Migration Law (Law No. 13.445/2017) and Normative Resolution No. 126/2017 grant temporary residence and humanitarian visas to immigrants, particularly in response to the Venezuelan crisis [24,46].

These legal differences directly affect access to housing and integration mechanisms in host countries like Brazil, where refugee policy frameworks intersect with broader urban management strategies [47,48].

2.2. Housing Access for Refugees

Housing is not merely a physical necessity but a structural condition for integration, inclusion, and access to urban citizenship. In the context of forced displacement, it represents both a material resource and a socio-political right.

The right to adequate housing, as defined by UN-Habitat [49], guarantees more than shelter: it entails legal security of tenure, access to infrastructure, safety, dignity, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes regarding one’s living environment. This perspective is central to understanding the multidimensional barriers faced by refugees in host cities of the Global South, such as Curitiba, Brazil.

In Brazil, despite constitutional guarantees and progressive migration laws (Law No. 9.474/1997; Law No. 13.445/2017), urban refugees face a fragmented institutional environment where local governments are often unprepared to translate legal protection into housing inclusion.

Studies from Europe and Canada show that legal barriers, discrimination, and market inaccessibility prevent many refugees from leaving collective shelters and entering the formal housing sector [33,34,50]. Although such camps are intended as temporary solutions, they often become spaces of prolonged confinement. This tendency is mirrored in the Global South through informal settlements, overcrowded peripheries, or neglected spaces; while not formally designated as camps, they function through exclusion and marginalization [21,51].

These patterns of spatial exclusion demand a shift in analytical focus: from housing as shelter to housing as an expression of urban belonging and governance. For refugees, the location, quality, and tenure of housing directly affect their capacity to rebuild social networks, access employment, participate in public life, and reclaim a sense of autonomy [9]. Moreover, housing choices are deeply shaped by digital inequalities. In increasingly digitalized urban systems, such as Curitiba’s, access to housing is often mediated through online platforms and digital bureaucracies. Refugees, especially recent arrivals or those with limited digital literacy, may be unable to navigate these systems, further compounding their exclusion [3,52].

2.3. Right to the City for Refugees

Section 2.1 and Section 2.2 examined the multiple barriers refugees face—legal, social, and infrastructural—and emphasized housing not only as a right, but as a critical interface between displacement and integration. Building on this foundation, this section introduces the right to the city as a theoretical and normative framework that bridges individual rights and collective urban transformation. This concept enables a rethinking of urban policies, particularly in cities like Curitiba, where tensions between progressive urban planning narratives and institutional exclusion of refugees reveal persistent governance gaps.

Originally proposed by Henri Lefebvre [53], the right to the city calls for a radical restructuring of urban life by ensuring that all inhabitants, not just those with legal citizenship, can actively participate in the production and transformation of urban space. It encompasses access to housing, mobility, information, cultural expression, and political representation. Importantly, it reframes marginalized populations, such as refugees, not as passive beneficiaries of aid but as legitimate co-creators of urban life [54,55].

In Brazil, this concept gained formal recognition in the City Statute (Federal Law No. 10.257/2001) and through national urban policy frameworks endorsed by the Ministry of Cities. These frameworks define the right to the city as the entitlement of all inhabitants to inhabit, use, produce, and govern the city in a just and democratic manner [56,57]. However, the operationalization of this right remains uneven, particularly for non-citizens and forcibly displaced populations, whose presence often falls outside the scope of municipal governance instruments and databases [58].

In the context of immigration, a well-managed refugee reception and integration process is pivotal for upholding human rights and fostering social inclusion. When refugees are welcomed and supported, they can become active contributors to urban life, enriching society and helping to develop inclusive and responsive urban policies [59].

Therefore, the right to the city challenges cities to democratize not only access to resources but also participation in shaping urban futures. This can be achieved through inclusive urban planning and policymaking, community-based initiatives and partnerships, access to language training, education, and job training, anti-discrimination policies and practices, and collaboration between governments, NGOs, and community organizations.

2.4. Urban Studies, Public Policies, and Strategic Digital City

Urban studies and strategic digital cities also understand city strategies as means to achieve the city’s sustainable objectives, implementing multiple projects and technologies to improve citizens’ quality of life [22,23,60,61,62].

Achieving co-benefits in urban development necessitates overcoming siloed approaches. Co-governance structures should be anchored in networks and will depend on the information exchange they foster, promoting integrated and collaborative strategies [30,63]. The emergence of fragmented urban spaces calls for a reevaluation of urban planning strategies. Planners and policymakers must address the complexities of fragmented segregation by promoting inclusive development, mitigating displacement risks, and fostering social cohesion across diverse urban landscapes. Recognizing the nuanced patterns of fragmentation is essential for developing effective interventions that accommodate the evolving nature of urban social dynamics [31].

Public policies are the principles and course of actions that governments take to address societal issues and achieve public goals. They are essentially decisions and actions of the government related to specific problems or concerns of an area, which can be laws and regulations. They are responses to public issues which have a great influence on society; hence, they are necessary for the development and well-being of the masses in a community [64]. Once in place, they help with the checking and balancing of operations and the life of community and city dwellers and foster the smooth running of the life and activities of the city dwellers while also helping city managers to work effectively [65].

Strategic digital city, which has city strategies and public services as subconstructs, is a tool for navigating the complexities of urban governance. Acting as roadmaps, they guide decision-making and provide a structured approach to achieving clearly defined objectives in dynamic urban environments [22,23,60]. City strategies and public services also serve as powerful instruments for directing policy initiatives, securing critical external funding, and fostering community integration. By providing a structured framework for public dialogue and collaborative action, these strategies pave the way for meaningful advancements in local development management [32]. By fostering community involvement and cultivating a sense of ownership over urban development, city strategies contribute to the creation of more engaged and invested communities [31].

Therefore, in this study, the concept of a strategic digital city (SDC) is applied as an analytical lens to investigate how urban strategies impact vulnerable populations, especially refugees, in their access to housing and local public services. By integrating variables such as civic participation, access to information, and public policies, the SDC allows for a critical reading of contemporary urban management and its implications for social inclusion as urban studies consider [22,23,24].

State regulations also play a crucial role in shaping housing access for refugees. While regulatory frameworks can impose limitations on where and how refugees settle, they also offer opportunities to design equitable housing solutions [33].

Displaced individuals use technology to navigate adversity. Smartphones and social media are critical in these resilience strategies, enabling refugees to maintain transnational social networks that evolve to mobilize tangible support through digitally mediated social bonding within communities, bridging between different groups, and linking with institutions [66].

Participatory digital methodologies offer a promising pathway. The “3D water survey” app developed for the Al Baqa’ refugee camp in Jordan exemplifies a bottom-up approach where residents become active data collectors and partners in identifying and solving urban problems [67]. By integrating community knowledge directly into a City Information Modeling (CIM) framework, such tools can bridge critical data gaps and ensure that technological solutions are context-specific and aligned with community needs. This approach shows that technology is not just a service delivered to refugees but a tool they can wield to shape their own environments [67,68].

A strategic digital city, therefore, is one that not only provides digital services but actively fosters digital citizenship, empowering marginalized communities to participate in their own governance. Thus, it is emphasized that when local public administration is not aligned with inclusive policies, it can exacerbate territorial inequalities and render vulnerable populations, such as refugees, invisible.

3. Materials and Methods

This research adopts a case study methodology [69], focusing on the city of Curitiba, Brazil, which was selected based on criteria of convenience, relevance, and urban representativeness in the context of refugee housing and municipal strategies. The study integrates both quantitative and qualitative techniques. This choice was made to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the multiple dimensions involved in refugee housing access and its relationship with urban policies and management.

The methodologies used include bibliographic research, document analysis, and content analysis [70,71], conducted through the examination and interpretation of theoretical references and data collected via documentary research. Additionally, an informal unstructured exploratory interview with the State Center for Information on Migrants, Refugees, and Stateless Individuals (CEIM) director enriches the qualitative analysis.

To analyze the socioeconomic profile of refugees in Curitiba, including factors such as nationality, age, gender, and education level, quantitative techniques were used to assess city strategies and policies. Simultaneously, qualitative methods complement this analysis, providing deeper insights into urban issues, refugee experiences with housing, and the specific names and types of relevant strategies, services, and public policies. This compilation of information forms the foundation of the research protocol, guiding the exploration of various factors (variables) that influence key aspects of the study (subconstructs) [70,71].

The research was conducted in four phases. (a) Preparation: this phase involved a literature review, the selection of a case study methodology (focused on Brazil), and the creation of the research protocol. (b) Data collection: data on refugees were gathered from reliable sources, including official organizations such as the Federal Police, the CEIM, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations (UN), and relevant government documents and strategic plans. (c) Analysis: collected data were analyzed following the research protocol. Constructs and subconstructs were established, and each variable were examined in relation to its corresponding subconstruct. A comparative analysis was conducted to form the research results. (d) Documentation: the final phase included documenting the analyzed data, writing the conclusion, and completing the research process.

Curitiba was selected due to its symbolic and strategic significance in Brazilian urbanism. Known for its pioneering urban planning models and digital infrastructure projects, Curitiba offers an apparent contradiction. While celebrated globally for its sustainable and participatory policies, it has yet to effectively integrate refugees into these frameworks. Although São Paulo and Boa Vista receive larger numbers of forcibly displaced persons, Curitiba presents an analytically valuable context precisely due to its institutional limitations, fragmented data management, and absence of refugee-specific strategies within urban plans.

According to CEIM and OBMigra reports, Curitiba experienced a measurable increase in its refugee population between 2015 and 2022, particularly from Venezuela, Syria, and Haiti. However, the city lacks centralized indicators and coherent policy instruments for refugee integration. This disjunction between a globally recognized urban management model and the marginalization of refugees justifies the selection of Curitiba as a case study to expose governance gaps and suggest pathways toward inclusive, rights-based urban policies.

This research’s observation unit comprises documents, books, surveys, articles, and government websites that help to build a comprehensive database on the refugee situation. Empirical data focus on refugees in Brazil, with particular emphasis on those in Curitiba. Critical sources include the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the National Committee for Refugees (CONARE), and NGOs that assist refugees.

Local sources, such as CEIM, provide annual reports on refugees’ socioeconomic profiles, which are analyzed in this research. Laws, conventions, and scientific articles on refugees’ right to housing and local public policies aimed at integration, reception, and accessibility to housing, infrastructure, health, and education are also examined [70,71,72].

A structured research protocol was developed, organizing the investigation into two primary constructs and four subconstructs, resulting in the analysis of 14 variables. Each variable was operationalized using specific sources, instruments, and techniques for analysis, as detailed in the following table (Table 1): The first construct, access to housing for refugees, is subdivided into three subconstructs: local access to housing for refugees; refugees’ socioeconomic profile; and refugees’ right to the city, while the second construct, strategic digital city, consists of a single subconstruct: city strategies aimed at refugees [69].

Table 1.

Research protocol with its constructs, subconstructs, variables, and data sources.

The local access to housing for refugees subconstruct contains 4 variables to be analyzed, such as housing types, refugees’ location, organizations assisting refugees, and ways of guaranteeing housing access for refugees in the city. Refugees subconstruct encompasses refugees’ categories, the refugee population percentage, the refugee gender percentage, refugees’ nationalities, and refugees’ age range. The right to the city subconstruct comprises peripheral urbanization categories and access to the right to the city. The city strategies aimed at refugees subconstruct encompasses city strategies’ names, city strategies’ thematics, and city strategies’ sources. For detailed data, see Supplementary Materials.

Although the study relies primarily on secondary data, all sources were selected for their reliability and institutional validity. Temporal relevance was considered: datasets from 2015, 2021, and 2022 were used to ensure a historical and comparative perspective. All empirical findings were triangulated across sources to enhance analytical rigor.

Regarding the Data Analysis Procedures, quantitative data (e.g., percentages of refugees by age, gender, category) were systematized using Excel and descriptive statistics. These were used to assess trends and demographic profiles obtained from CEIM, UNHCR, CONARE, FAS, and IOM reports (2015–2024) [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86].

Qualitative data (e.g., institutional strategies, categories of urbanization) were analyzed through thematic content analysis [87], allowing identification of recurring patterns and key themes related to exclusion, integration, and spatial distribution. It should be noted that, as this is predominantly qualitative research, complex mathematical or statistical formulas were not applied. The data analysis followed an interpretive approach, focusing on the identification of thematic patterns and relationships between variables, as detailed in the research protocol.

The qualitative component is supported by a single, unstructured interview with the CEIM coordinator, because the center is the primary municipal body coordinating refugee support in Curitiba, and its coordinator offers unique insight into institutional practices and governance gaps. This technique was selected to allow for an open-ended dialogue, enabling deeper insights into the institutional practices, challenges, and perceptions regarding refugee housing and urban integration. However, it should be noted that although only one informal interview was conducted, its function was to complement the documentary analysis and the triangulation of secondary data, as provided for in the research protocol. The interview was not intended to provide exhaustive narrative accounts but to validate and contextualize patterns identified in the secondary data.

The interview followed a flexible thematic guide addressing topics such as refugee profiles (including nationality, gender, marital status, and education); predominant areas of residence and the formation of refugee communities; the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and housing location; types of housing occupied (e.g., rental housing or social housing); CEIM’s institutional functions; referral pathways to other agencies; cooperation networks; and both institutional and refugee-specific challenges.

No sensitive or confidential data was collected. All information obtained during the interview is anonymous, and the content discussed refers to general institutional practices, not to individual cases. Furthermore, a supporting institutional report was made available, which was already intended for public dissemination and served to validate the interview content. The information collected was systematized through field notes and analyzed thematically to support and triangulate the broader findings of the study.

Additionally, and despite the triangulation of sources and the institutional validation of the data used, a significant limitation of the study lies in the absence of centralized statistics and the fragmentation of information about refugees in Curitiba. It is important to state that this gap made the application of more robust quantitative methods difficult, requiring the use of an interpretive qualitative approach. Thus, the scarcity of systematized data from the local government also compromises the comparability between cities while limiting the generalization of the results, reinforcing the need for local public policies that improve the collection and management of data on refugee populations, reiterating that qualitative methods can also be used in urban studies with refugees [88].

The research spanned from February 2022 to January 2025 and followed the four phases outlined.

4. Research Analysis

4.1. Analyses of Local Access to Housing for Refugees

The analysis revolves around four critical variables related to refugees’ housing access in Curitiba, emphasizing the importance of addressing these issues to meet refugees’ needs and uphold their fundamental rights.

4.1.1. Housing Types for Refugees

This first variable categorizes the various forms of housing available to refugees, aiming to understand the specific needs and rights associated with each. Based on theoretical foundations, housing for refugees can be divided into four key concepts: home, housing, shelter, and settlements, distinguished by their scope and permanence.

The broadest concept, home, encompasses more than a physical space; it includes essential rights such as privacy, dignity, and security. Housing, however, is typically used in urban and neighborhood contexts, integrating infrastructure, services, and urban strategies. Shelters and settlements, in contrast, represent temporary and emergency solutions vital for survival, particularly for refugees and other vulnerable groups.

While home is associated with permanence, the other three forms, housing, shelter, and settlements, are transitional and are often tied to physical and spatial limitations. However, all these concepts share intrinsic rights aimed at fulfilling basic human needs and ensuring dignity.

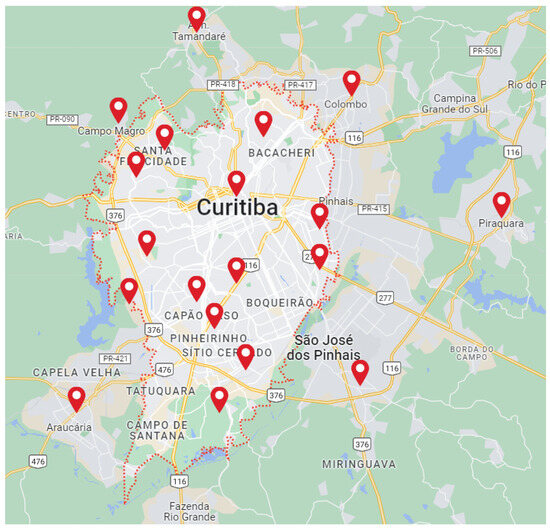

This analysis identifies that most refugees do not inhabit what could be considered a stable home in legal, emotional, or material terms. Instead, the majority live in rented properties or temporary collective accommodations. Only 6.8% own their residence, while 21% live in precarious, shared or collective arrangements.

This reinforces the theory that public housing frameworks inadequately address refugees’ needs. The lack of targeted housing programs, combined with structural barriers such as high rental costs, the absence of guarantors, and discrimination, constrains refugees to temporary, often informal solutions. The analysis demonstrates that existing housing options fail to fulfill the broader dimensions of the right to housing, especially regarding permanence, dignity, and autonomy.

4.1.2. Refugee Locations in Curitiba

The second variable analysis examines the neighborhoods and metropolitan regions in which refugees concentrate, emphasizing the importance of distributing support services to these areas, particularly in neighborhoods distant from the city center.

Annual reports from the Center for Information on Migrants and Refugees (CEIM, in Portuguese) identify the largest refugee groups in Curitiba as Haitians, Venezuelans, Syrians, and Cubans. Most refugees are adult males, many of whom possess qualifications that enable them to seek employment and assistance. Refugees often secure housing independently or through referrals to social hotels or the Social Action Foundation (FAS). Notably, individuals from similar origins, such as Haitians, frequently form their own communities.

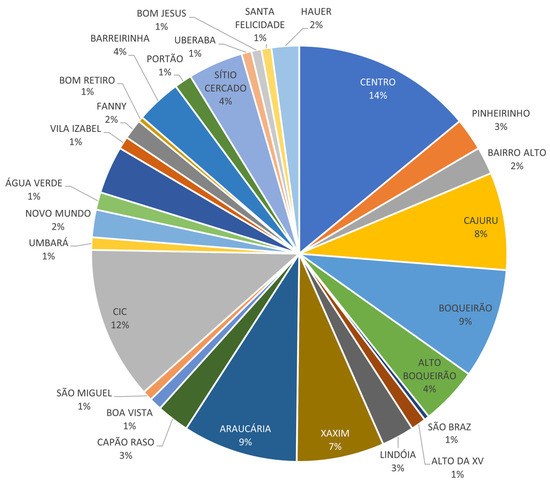

In 2022, CEIM assisted 6004 migrants and refugees, officially registering 3751 individuals (62.4%). However, 2842 individuals (47%) did not report their housing information due to language barriers, confidentiality concerns, and fear of persecution. Among those identified, the majority resided in central Curitiba (14%), followed by neighborhoods such as CIC (12%), Araucária, Boqueirão, Cajuru, and Xaxim, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Refugees’ locations in the city of Curitiba, created by the authors based on the CEIM data.

Support services are concentrated in central Curitiba. The high concentration of registrations in the city center likely reflects convenience or greater awareness of aid centers located there. However, many refugees reside in peripheral neighborhoods or metropolitan areas, limiting their access to essential services. Thus, while 14% reside in the center, 86% are dispersed across peripheral zones, often lacking adequate access to public services, infrastructure, or employment opportunities (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Refugees’ distribution in Curitiba and the metropolitan area.

Addressing language barriers and confidentiality concerns is critical, as nearly half of the refugees assisted did not disclose their housing situations. Implementing secure and anonymous location-tracking mechanisms could help to more effectively identify and meet the needs of refugees across the city and its metropolitan region.

4.1.3. Assisting Organizations for Refugees in Curitiba

The third variable analysis explains the key partnership that exists between the UNHCR and religious institutions, notably Caritas, which has been instrumental in advancing human rights and refugee support at both national and international levels.

Brazil’s legal framework for refugee assistance, overseen by the National Committee for Refugees (CONARE), includes representatives from various ministries, such as the ministries of justice, foreign affairs, labor, health, education, and the federal police, alongside civil society members, particularly religious institutions and UNHCR representatives.

This tripartite structure integrates three critical actors in refugee support: religious institutions (e.g., Caritas and the Institute for Migration and Human Rights), international organizations (UNHCR), and the Brazilian government, primarily represented by the Ministry of Justice, which presides over CONARE. While the legal framework primarily focuses on documentation, broader challenges, such as social, psychological, economic, and cultural integration, persist.

Moreover, the State Center for Information for Migrants, Refugees, and Stateless Persons (CEIM), Social Assistance Centers (CRAS), the Specialized Social Assistance Reference Center (CREAS), the Social Action Foundation (FAS), and TETO Brazil, are some of the main organizations which offer a range of services, including guidance on public services, documentation, job placement, education referrals, social assistance, legal rights, and support for victims of discrimination, domestic violence, and rights violations.

Institutions such as FAS manage social policies related to employment and assistance for individuals in vulnerable situations, aligning their services with the Unified Social Assistance System (SUAS), which emphasizes family and community integration. Meanwhile, TETO Brazil focuses on building emergency housing in precarious communities, using refugee-inclusive eligibility criteria. Families must meet residency and ownership requirements, but no one is excluded based on refugee status if proper documentation is provided.

Refugees and migrants in vulnerable situations may also access certain federal programs through the CadÚnico system, including income transfer initiatives (Bolsa Família), affordable housing (Casa Verde e Amarela), disability benefits (Benefício de Prestação Continuada), social rent assistance, educational and professional training programs for youth (Projovem), child development support (Criança Feliz), and federal initiatives for professional training and labor market inclusion (Progredir).

Organizations like Caritas and UNHCR play central roles, and municipal actors like CEIM and FAS offer documentation, job referral, and social support services. However, no institution assumes direct responsibility for housing access. Federal programs such as Casa Verde e Amarela theoretically include migrants, yet their eligibility criteria often exclude those lacking permanent documentation. Programs like Bolsa Família or CadÚnico offer indirect support, but without addressing structural housing deficits. This points to an institutional gap in Curitiba’s urban governance structure, with housing access falling between the mandates of multiple agencies, which also reveals a contradiction between legal rights and administrative practices.

4.1.4. Ways of Guaranteeing Access to Housing for Refugees in the City

Lastly, the fourth variable analysis concentrates on analyzing housing programs and temporary shelters.

While refugees technically have the right to rent any property, they frequently face barriers such as the need for a guarantor, discrimination based on their foreign status, and high costs, all of which complicate their integration into Brazilian society.

Migration Law No. 13,445/2017 in Brazil guarantees the right to housing for migrants. Article 3 of this law establishes the principles and guidelines of Brazil’s migration policy, including equal and free access for migrants to services, programs, and social benefits, such as housing, education, and employment. The responsibility for ensuring the right to housing is shared by the Union, the States, the Federal District, and the Municipalities, which implement programs to build housing and improve living conditions.

However, migrants often face significant challenges upon arriving in Brazil. Many lack the resources necessary to rent a property, besides the difficulty of securing a local guarantor, and frequently rely on temporary shelters or acquaintances. Refugees also encounter discrimination and biases based on their status or nationality. To receive guidance and assistance, migrants are typically referred to social assistance services. Yet, eligibility criteria for government housing programs, such as Casa Verde e Amarela, often exclude refugees without permanent residency or citizenship, limiting their access despite their legal rights.

Empirical studies conducted in Curitiba by the UNHCR in cooperation with the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) provide valuable insights into refugees’ housing conditions, including their living arrangements, shared spaces, and economic constraints. These studies reveal that refugees overwhelmingly live in rental housing, with 90% of surveyed individuals renting their accommodations.

Only 6.8% have managed to purchase their own homes, highlighting limited long-term integration. Approximately 21% live in collective or shared housing, such as boarding houses or shelters, reflecting precarious and overcrowded conditions, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Housing access for refugees: owned, shared, or rented.

High rental costs and the lack of guarantors often prevent refugees from accessing private rentals. For instance, 34% of Venezuelan refugees surveyed reported having no guaranteed living space for the following month.

Temporary housing solutions, such as public shelters, offer another avenue for addressing refugees’ housing needs. However, these facilities often have strict time limits and limited capacity. For example, the Santa Dulce dos Pobres Reception and Integration Center in Curitiba provides housing for up to three months while facilitating access to employment, education, and other essential services. Yet, shelters specifically designed for refugees, such as those managed by Cáritas Brasileira, are insufficient to meet demand. Similarly, the Casa da Acolhida para Família Migrante, managed by FAS, offers semi-independent living arrangements for migrant families but has a capacity of only 20 individuals.

Moreover, some normative resolutions incentivize real estate investment for residency authorization but remain largely inaccessible to refugees due to high financial thresholds. Nonetheless, access to suitable housing for refugees often depends on their economic power. Despite legal frameworks recognizing housing as a right, structural and institutional barriers hinder refugees’ access, reinforcing exclusion and precarity. Tailored public policies remain absent.

So, for refugees to truly integrate into society and feel welcomed, it is essential to promote stability and long-term housing opportunities through public policies. These policies should include subsidized rent, low-interest loans, and measures to combat discrimination in the housing market.

4.2. Refugees’ Analysis

The examination of local housing access for refugees underscores the need for tailored solutions to address their diverse experiences and challenges. This subsection transitions to an analysis of refugee demographics in Curitiba, focusing on categories, percentages, gender distributions, nationalities, and age ranges. By dissecting these factors, we gain a more nuanced understanding of how socioeconomic profiles influence housing needs and integration efforts. This analysis builds insights into housing access and provides a demographic lens through which urban strategies and public policies can be evaluated.

4.2.1. Refugee Categories

The first variable analysis plays a pivotal role in the housing access context, as it helps illuminate the different situations faced by this population and determines the type of assistance and protection each group requires. Refugees can be categorized based on the reasons for their displacement, the duration of their displacement, and their level of integration into the host society.

Refugees can be classified by their geographic movement: those who cross international borders and those who remain within their country of origin, known as internally displaced persons (IDPs). Refugees, as defined by international law, are entitled to specific protection under instruments such as the 1951 Refugee Convention. In contrast, IDPs remain under the jurisdiction of their national governments and often rely on assistance from international organizations or NGOs. This legal distinction leads to differences in rights, responsibilities, and access to resources between the two groups.

The circumstances of refugees also vary significantly depending on the duration of their displacement and the policies of the host country. Short-term refugees may experience temporary shelter and relief-focused aid, whereas long-term refugees face protracted displacement, requiring them to navigate complex bureaucracies, legislative frameworks, and integration processes. Refugees’ status can also depend on whether they are formally recognized, integrated into society, or left in informal and precarious conditions. Additional categories include asylum seekers and resettled refugees, whose circumstances are shaped by specific host countries’ policies and urban planning measures.

Host government policies and public attitudes play critical roles in shaping the refugee experience. In some cases, neglect or systemic barriers result in the erosion of rights, particularly for those living in informal or unregulated settings. Discrimination, racism, and xenophobia, manifesting through societal attitudes or government securitization policies, further hinder refugees’ ability to rebuild their lives.

Depending on public policies, some refugees can maintain their cultural practices, while others face forced assimilation or marginalization. For example, the securitization of migration policies in some countries fosters an environment of exclusion, deterring integration and exacerbating vulnerabilities. Conversely, inclusive urban planning and proactive government policies can empower refugees, foster integration, and enable access to rights.

Refugees in Curitiba include recognized refugees, asylum seekers, and individuals with humanitarian visas. While these legal categories shape access to documentation and services, the analysis finds that many policies do not operationally distinguish between them. This produces bureaucratic ambiguity and uneven access to rights. Furthermore, long-term displacement trajectories and protracted waiting times for recognition reduce the effectiveness of integration strategies. Without tailored responses to these distinct categories, urban policies risk reproducing exclusion and undermining the logic of differentiated protection.

4.2.2. Refugee Population Percentage in Curitiba

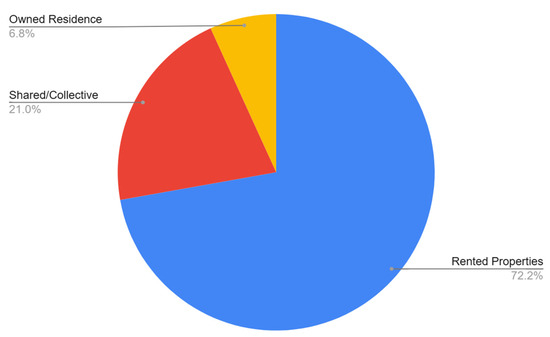

The second variable analysis highlights some important insights into the housing challenges faced by the city. When examining data on the percentage of refugees within Curitiba’s population, it becomes evident that no centralized or comprehensive statistics are available, as can be seen in Figure 4 and Table 2. Instead, various organizations provide fragmented figures on specific segments. The data for this analysis were gathered from official sources, including the Curitiba government, OBMigra, the Federal Police, the Latin American House (CASLA), and reports from the UFPR in collaboration with organizations such as UNHCR.

Figure 4.

Number of migrant registrations by main municipalities in Brazil. Based on OBMigra data from the Federal Police, National Migration Registration System (SISMIG RA), 2021.

Table 2.

Number of migrant registrations, by month of registration, according to main municipalities: January 2021, December 2021 and January 2022.

The most recent data from the Federal Police, dated 2015, indicates that over a 15-year period, approximately 39,300 foreigners requested visas at Curitiba’s Federal Police office. Of these, 51.3% retained active registrations. However, this data does not reflect the actual number of immigrants in the city, as visa requests can be made at any Federal Police office, and individuals often relocate within the country. Furthermore, undocumented immigrants are excluded from these statistics. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of immigrants in Brazil, Paraná, and Curitiba increased significantly, coinciding with a rise in refugee arrivals. For instance, the number of refugees entering the country annually grew from 9000 in 2000 to approximately 81,000 in 2015, with Paraná and Curitiba experiencing similar growth patterns.

CASLA estimates that Curitiba hosts approximately between 15,000 and 19,000 migrants and refugees, while Paraná hosts an average of 60,000. More recent data from 2021 and 2022 positions Curitiba among the top five cities in Brazil receiving refugees, following Boa Vista (RR), São Paulo (SP), Manaus (AM), and Pacaraima (RR). For example, in 2021, Curitiba recorded approximately 5000 migrant registrations. In 2022, the city averaged 400 registrations per month, maintaining its status as a key destination for refugees.

The data underscores Curitiba’s prominence as a hub for migrants and refugees. Despite this, the lack of centralized and consistent statistics complicates efforts to fully understand the dynamics of the city’s refugee population. However, Curitiba stands out as a focus for migration after São Paulo and Boa Vista.

The profiles of refugees in Curitiba also reveal behavioral trends influenced by their need for community and security. Many prefer to settle in suburban or peripheral areas to maintain a sense of cultural and social cohesion. Despite these preferences, Curitiba itself attracts more refugees than its metropolitan region, hosting an estimated 30% to 40% of all refugees in the state, while Paraná ranks as the fourth-highest state in terms of the number of refugee applications received and is home to 4 of the 18 cities that host 75% of Haitian migrants in Brazil. Current statistics lack precision and centralization, making it difficult to form a comprehensive understanding of the refugee population’s size, needs, and distribution. The absence of precise figures highlights a pressing need for improved data collection and coordination among agencies.

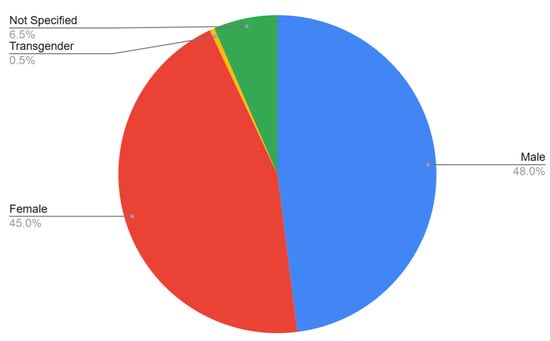

4.2.3. Refugees’ Gender Percentage

The third variable analysis reveals a nearly equal distribution between men and women among refugees in Curitiba. Of the 3751 individuals registered in the CEIM report, 1794 identified as male, 1686 as female, 20 as transgender, and one person did not specify their gender. In percentage terms, this equates to 48% male, 45% female, and 0.5% transgender.

Additionally, OBMigra’s 2022 report highlights that, on a national scale, 54.6% of asylum seekers in Brazil are male and 45.4% are female, reaffirming that men slightly outnumber women among refugees, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Refugees’ gender percentage.

This equilibrium is significant for urban planning and housing policy, as gender differences influence the needs and vulnerabilities of refugee populations. Female refugees often encounter heightened challenges with regard to housing, particularly in collective shelters, which include risks related to gender-based violence, harassment, and a lack of privacy. Addressing these issues requires housing policies that ensure safety and dignity for women, including secure spaces and support systems.

Similarly, the inclusion of transgender individuals, though a small proportion (0.5%), highlights the need for gender-sensitive and inclusive policies. Transgender refugees may face discrimination and unique barriers to housing access due to widespread misunderstandings of their identities.

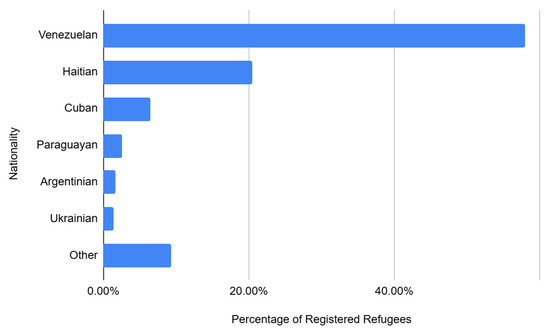

4.2.4. Refugees’ Nationalities in Curitiba

The fourth variable analysis highlights the diversity of the refugee population in the city. The 2022 CEIM report provides a detailed breakdown of the nationalities of refugees in Curitiba, revealing significant trends in the composition of this population. Venezuelans constitute the majority, with 2178 individuals (58%), followed by Haitians with 772 individuals (20.5%). Other notable groups include Cubans (247 individuals, 6.5%), Paraguayans (99, 2.6%), Argentinians (66, 1.7%), and Ukrainians (53, 1.4%). On a national scale, the 2022 OBMigra report highlights Venezuela as the leading source of asylum seekers in Brazil, with 33,753 applications (67%), followed by Cuba (5484 applications, 10.9%), Angola (3418 applications, 6.7%), Colombia (744 applications, 1.4%), and China (512 applications, 1%). These figures reinforce Venezuela’s significant role in shaping refugee trends, reflecting the ongoing humanitarian crisis in the country, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Refugees’ nationalities in Curitiba, by percentage.

Understanding the predominant nationalities assists in promoting refugees’ integration and assimilation, as different ethnic and cultural groups have specific housing needs. For example, some nationalities, like the Haitians, prefer living in groups and forming their own communities, even in remote areas. Each nationality brings unique cultural and social practices that influence housing preferences, such as household size, communal living arrangements, and proximity to community support networks.

Furthermore, adults, families with children, the elderly, and illiterate groups have different housing requirements. Families with children may need access to nearby schools, while the elderly may require accessible housing. Language barriers, employment opportunities, and social integration efforts also vary by group. For instance, Venezuelans often seek urban areas for work, whereas other groups might prioritize community-centric neighborhoods.

4.2.5. Refugees’ Average Age Range in Curitiba

The fifth variable analysis highlights the diversity of age demographics among refugees in the city. The 2022 CEIM report does not provide specific age-range data for refugees in Curitiba. However, certain trends can be inferred from related metrics, particularly educational attainment. According to the report, 54% of registered refugees have completed an education of at least high school level or higher, indicating that the majority are adults. In contrast, 26.7% have only completed elementary education or reported that they did not finish high school. Expanding this analysis to a national level in Brazil for 2022, 30% of refugees are under the age of 15, while 49% are over the age of 25. These figures highlight a diverse age distribution among refugees, with a significant proportion being working-age adults.

This data assists in identifying age-specific housing needs. For example, adult refugees in the working-age group may prioritize housing near employment opportunities or urban centers. Families with children would prefer housing near schools and childcare facilities, while elderly refugees require accessibility features, such as ramps and elevators, which are critical for individuals with limited mobility. Moreover, higher levels of education among many refugees suggest a capacity for integration into local economies, potentially impacting their housing preferences and ability to afford independent living.

4.3. Analysis of Refugees’ Right to the City

Understanding refugees’ socioeconomic profiles underscores the critical need for equitable access to urban spaces and services. Connecting the demographic findings to broader urbanization trends, such as peripheral expansion and gentrification highlights systemic barriers refugees face in asserting their urban rights. The discussion serves as a conceptual bridge to assess how urban policies can create inclusive cities that uphold the dignity and rights of all inhabitants, considering the various backgrounds of the refugees, their economic challenges, and issues they face with social integration. This encourages helping the refugees with access to resources, social inclusion, and community engagement, and can be achieved through community-based initiatives, collaborations, and partnerships, which can lead to creating a more inclusive and equitable urban environment.

4.3.1. Peripheral Urbanization Categories

This first variable is a multifaceted phenomenon involving the unregulated expansion of metropolitan areas into rural zones. This process has led to the emergence of multiple urban centers, challenging the traditional notion of a single city center surrounded by peripheries. Instead, cities are transforming into multi-centered entities, including their peripheral regions. Peripheral urbanization can be categorized into informal settlements, peripheralization, gentrification, and illegal subdivisions. These dynamics are closely tied to the disordered occupation of urban spaces by low-income populations, who are often deprived of basic services such as potable water, sanitation, and electricity [59,60].

Low-income groups increasingly settle in areas with limited or no access to urban infrastructure, creating sprawling informal settlements. Rising property values and rental costs force lower-income families into precarious living conditions. This process often leads to homelessness or compels families to compromise on other fundamental rights like food, health, and education in order to afford adequate housing.

As cities become multi-centered, new urban areas emerge, resulting in a heterogeneous distribution of resources, services, and opportunities. This urban fragmentation often reflects and magnifies pre-existing social inequalities. Central areas have a greater concentration of employment opportunities, quality education, healthcare, and recreational amenities, whereas peripheral areas suffer from resource scarcity, inadequate infrastructure, and limited access to urban services. These disparities are compounded over time as public policies and investments prioritize central areas, perpetuating socioeconomic inequality and segregation. Refugees and vulnerable groups are particularly affected, often residing in the most precarious and underserved areas [60].

Refugees often seek housing in areas where they can maintain community ties, but this preference may isolate them further from resources. The lack of adequate housing undermines the dignity and security of affected populations, particularly women, children, and the elderly.

Curitiba’s urban fabric reflects national trends of peripheralization and fragmentation. Refugees settle in informal or semi-legalized zones lacking basic infrastructure. Their location at the margins, both spatially and institutionally, exemplifies what Lefebvre termed as the right to difference being denied through exclusionary urban planning.

The peripheral urbanization categories identified, such as informal settlements, illegal subdivisions, and gentrification zones, limit refugees’ access to services and participation in urban life. These dynamics reinforce cycles of spatial injustice, where refugees’ visibility is confined to areas of invisibility in policy, and the deprivation of housing is not merely a matter of shelter; it denies access to health services, education, civic participation, and other fundamental human rights.

4.3.2. Access to the City

This second variable is an argument that cities are not merely physical structures but socially constructed spaces where all individuals should have the right to actively participate in their creation and influence their development. Housing accessibility emerges as a central component of this right, as housing not only shelters individuals but also serves as a means for social inclusion and active participation in urban life.

Lefebvre conceptualizes the city as a tripartite entity: social space that represents the collective interactions of urban dwellers; a produced space that encompasses the tangible aspects of urban planning and housing; and lastly, the living space, which reflects personal experiences and memories attached to urban environments.

In the context of housing accessibility, the focus lies on the produced space. Decisions regarding the availability and quality of housing are made here, directly impacting society. It is critical that this space be shaped with the active involvement of residents to ensure that housing policies address their needs and aspirations, fostering democracy and social inclusion in urban design. Access to the city extends beyond housing to encompass essential services such as potable water, sanitation, energy, and transportation. Urban policies must ensure that all residents, regardless of income or social status, have access to adequate and affordable housing alongside these critical services. This includes rehabilitating and renewing degraded urban areas to improve living conditions [64,65].

Furthermore, these policies must aim for equity in distributing urban benefits and burdens while promoting environmental sustainability. Recognizing cultural and social diversity is essential, as urban policies should protect minority rights and celebrate the pluralistic nature of cities, fostering an inclusive environment.

For the right to the city to be realized, it is essential to establish avenues for civic engagement, such as community forums, which are spaces for open discussion and collaboration, public assemblies, which are platforms for collective decision-making, and electoral processes that offer opportunities for citizens to influence urban governance [38,39]. Access to information is vital. Traditional and digital media can empower residents by keeping them informed about urban issues, enabling them to make educated decisions.

Mass housing projects and substandard dwellings are often created as reactive solutions to population surpluses. These structures lack aesthetic and functional qualities, often being cramped and poorly designed. Such inadequacies exacerbate social exclusion, as lacking a fixed address can hinder access to employment, public services, and full societal participation. Denying the right to housing equates to denying the right to belong to the city.

In the context of industrialization, urbanization often prioritizes housing production over the holistic concept of habitation. Cities evolve continuously, shaped by social, economic, and political dynamics. Housing plays a critical role in enabling individuals to establish themselves and actively engage in urban life. This entails safe, stable housing that supports individual and family well-being, inclusive housing that fosters a sense of belonging and community, and adequate housing that allows individuals to fully engage in the social and economic fabric of the city.

Refugees’ limited access to urban rights (mobility, information, and services) reflects their marginal status in city-making processes. Curitiba’s policies lack mechanisms for civic participation, public deliberation, or transparency that would empower refugee voices.

Mass housing programs and urban renewal policies rarely include refugees in their planning or design. This results in housing solutions that are either exclusionary or poorly adapted to their needs. The lack of participatory frameworks undermines not only housing quality but the broader democratization of the urban experience.

4.4. City Strategies and Public Policy Analyses of Urban Studies

The analysis of the “Right to the City” highlighted the importance of strategic interventions to address urban inequities. The analysis of strategies aimed at migrants, refugees, and stateless individuals is crucial for understanding the complex issues surrounding housing access and integration, particularly in Paraná, Brazil. These strategies adopt a multifaceted approach to address the challenges these populations face in seeking dignified and secure lives. In this subsection, three variables will be analyzed thoroughly: the strategies’ name, theme, and source.

The first strategy, outlined in the II State Plan for Migrants and Refugees (2022), provides a comprehensive framework encompassing education, family and social development, culture, security, justice, employment, human rights, and health. While it does not directly address housing, its multidimensional goals, such as integration and protection, have direct implications for housing access. The plan emphasizes the importance of evaluating and reformulating existing policies to ensure the active participation of migrants. It also highlights the need to create deliberative and participatory spaces, which are essential for promoting rights and inclusion in society, including the right to housing.

The Livelihood Strategy (UNHCR, 2019–2021) [75], focuses on economic and employment themes but also incorporates social and integration aspects. By empowering refugees with skills and job opportunities, this strategy indirectly contributes to their ability to secure adequate housing. Furthermore, its holistic approach promotes social inclusion and awareness of refugee rights, factors that directly influence housing access [66].

Specific interventions aimed to reduce unemployment, combat xenophobia, and address the lack of awareness among public servants and financial institutions. Measures included financial assistance, vocational training, job placement programs, and the promotion of entrepreneurship. Data provided by UNHCR revealed that 70% of participants in integration centers achieved steady incomes, indicating progress in socioeconomic inclusion.

The third strategy, Operation Welcome, is a federal initiative aimed at relocating refugees to different Brazilian states, offering opportunities for socioeconomic integration in other regions. Launched in response to Venezuelan migration, its key objectives are to alleviate pressure on Roraima’s public services and enhance refugees’ integration prospects. The strategy focuses on areas such as shelter transfers from Roraima to integration centers in other cities, family reunification to facilitate connections between relatives, support for community networks through social gatherings, and job placements to secure formal employment opportunities.

Since 2018, 102,476 individuals have been relocated across Brazil, including 6548 in Curitiba (6.4% of the total). A gender analysis reveals a near-equal distribution: 48% female and 52% male, predominantly adults. Among relocation methods, social reunification accounts for 63%, followed by family reunification (17%), institutional transfers (12%), and employment placements (5%).

Targeted and specific strategies also play an important role in facilitating immigrants’ integration and recognizing the importance of learning the local language. Adapting strategies to meet the diverse needs of different groups is crucial for ensuring inclusion and access to essential services. These strategies also ensure that migrants and refugees have the necessary documentation to access housing and other services, such as through the issuance of humanitarian visas.

For example, the Social Assistance for Migrants program, outlined in a 2016 report by the Ministry of Social Development, included measures to assist migrants in vulnerable situations. Programs like the Brazilian Portuguese for Humanitarian Migration Project (PBMIH) and initiatives by universities and NGOs, including language courses, help ease migrants’ daily challenges and foster market integration.

The Brazilian Action Plan (2014) [76] is another example, as it expanded humanitarian visas for Syrians and implemented the Quality Assurance Initiative (QAI) to enhance asylum procedures. Efforts included reducing backlogs, improving case management, and addressing protection demands for mixed migrations. Education and Human Rights Strategies were also adapted to address the specific needs of diverse groups, including refugees. Legal provisions, such as Law 9.474/97, protect their right to asylum, while new migration laws promote safe and regulated entry pathways.

Housing appears indirectly as a component of integration, but without specific funding, programs, or monitoring. The absence of a municipal or state housing strategy for refugees exposes a critical policy gap, even as Curitiba ranks among Brazil’s primary refugee destinations. Curitiba’s participation in Operation Welcome (6.4% of total relocations) indicates strong political will, but without local housing support, its impact is limited.

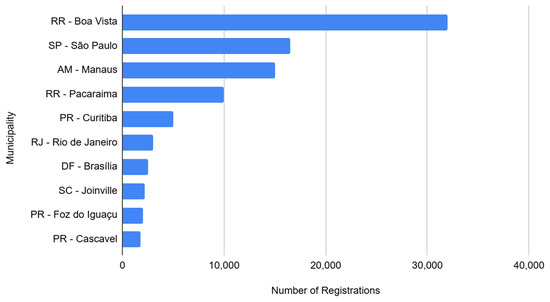

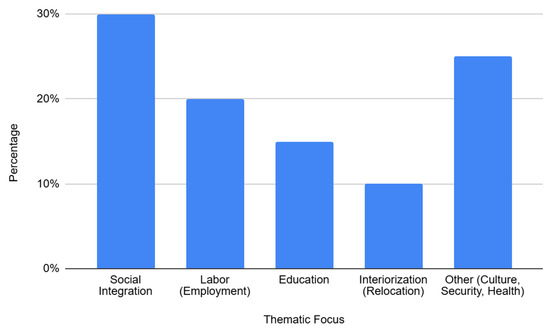

The second variable analyzes the dominant themes in the strategies discussed. A prominent theme that emerges from the analysis is social integration, which accounts for 30% of the thematic focus. This is followed by labor (20%), education (15%), and interiorization (10%), with culture, security, and health collectively comprising the remaining 25%, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Strategies aimed at refugees’ thematic focus by percentage.

However, a significant gap exists in addressing housing as an independent issue. While interiorization and shelter initiatives provide initial support, there are no dedicated policies that treat housing as a standalone priority.

The third variable analyzed is the sources of information underlying these strategies, which demonstrate a collaborative effort involving government entities, NGOs, and religious organizations. This partnership enabled the development of the strategies analyzed earlier, with government participation present in all initiatives and UNHCR partnership in certain cases. However, this institutional fragmentation results in inconsistent implementation, bureaucratic dead ends, and policy inefficacy.

Despite these collaborative efforts, none of the strategies explicitly address housing access. While aspects of housing may be implicitly included in certain initiatives, the absence of a dedicated strategy for housing access remains a critical gap. Ensuring housing inclusion as a specific focus and implementing concrete policies in this area are essential steps toward improving the overall effectiveness of integration strategies.

5. Results and Discussions

The exploration of themes such as housing access for refugees, refugee categories, the right to the city, and strategies for migrants, refugees, and stateless individuals provides a comprehensive view of the complex issues related to housing access for vulnerable populations in Curitiba, Brazil. These interconnected analyses emphasize the need for a holistic approach to address the challenges faced by refugees.

To move beyond emergency responses, refugee housing must be fully integrated into Curitiba’s broader urban policies, including its municipal master plan and digital city platforms. This would create accountability and sustained institutional commitment. Curitiba’s municipal government should establish a single Refugee Housing Unit that coordinates all housing-related programs, consolidating data and streamlining access to rentals, subsidies, and emergency shelters.

A one-size-fits-all approach fails to account for these differences. Designing inclusive policies means offering a flexible variety of solutions such as rental subsidies, transitional housing, community housing models, and integration into existing social housing frameworks. Government policies and urban planning play a pivotal role in shaping access to rights and services, not only for educated adult refugees but also for more vulnerable groups, such as minors and the elderly.

Curitiba’s diverse refugee population reflects how housing needs vary across ethnic groups. Many refugees prefer forming their own communities, even in peripheral areas. Yet, despite this spatial concentration, support services remain centralized, creating a mismatch between where refugees live and where they can access assistance. This spatial disconnection forces many into informal or overcrowded settlements, reinforcing cycles of exclusion and invisibility. Addressing this requires a redistribution of services and investments toward these urban peripheries, alongside strategies like mobile service units, localized infrastructure improvements, and community-based digital mapping.

Applying Lefebvre’s framework exposes how Curitiba’s celebrated smart city and participatory planning initiatives bypass refugees. Their invisibility in social participation projects illustrate a denial of their spatial and political rights. Recognizing refugees as co-producers of urban life would require embedding them in decision-making forums, data systems, and urban governance, transforming the right to the city from slogan to practice.

A more focused approach to housing is essential for ensuring dignity, family stability, and the social inclusion of refugee populations. Economically privileged refugees typically face fewer challenges in securing housing, while others depend on temporary solutions, which expose them to social exclusion, exploitation, abuse, and harm.

On the other hand, strategic digital city planning offers a promising avenue for refugee integration by providing information, facilitating collaboration, monitoring housing policies, and promoting active civic participation. However, it is equally important to develop inclusive strategies that address the needs of those who cannot access such services. Public awareness campaigns are as critical as strategies to ensure housing access, as refugee integration depends on both governmental and societal acceptance.

Curitiba’s strategic digital city framework has the potential to support refugee integration through online housing portals, legal guidance platforms, and civic engagement tools. However, this model excludes refugees who lack digital access or literacy. Ensuring digital inclusion, through free public internet access, multilingual interfaces, and digital literacy initiatives, is a necessary step for the inclusion process. These tools must also be paired with on-the-ground support, such as mobile help centers or paper-based applications, to ensure that no one is excluded.

This research highlights successful examples, such as “The Livelihood Strategy” and “The Welcome Operation,” which were implemented through collaboration between the government and UNHCR. These initiatives fostered refugee integration and well-being within the host society. However, other international examples further support this research and illuminate Curitiba’s potential pathways.

For instance, the Canadian approach to social bridging for Syrian refugees demonstrates how friendliness, intentional connections, and neighborly relations can help refugees adapt and develop a sense of belonging. Successful integration strategies in Canada involve collaboration between government agencies, community organizations, and individual citizens. By working together, these entities strengthen support systems for refugees and create more effective strategies [61].