Self-Build Practices on University Campus: Socio-Psychological Effects on Care and Intention to Spend Time in Outdoor Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objective and Hypotheses

2. Method

2.1. Participants

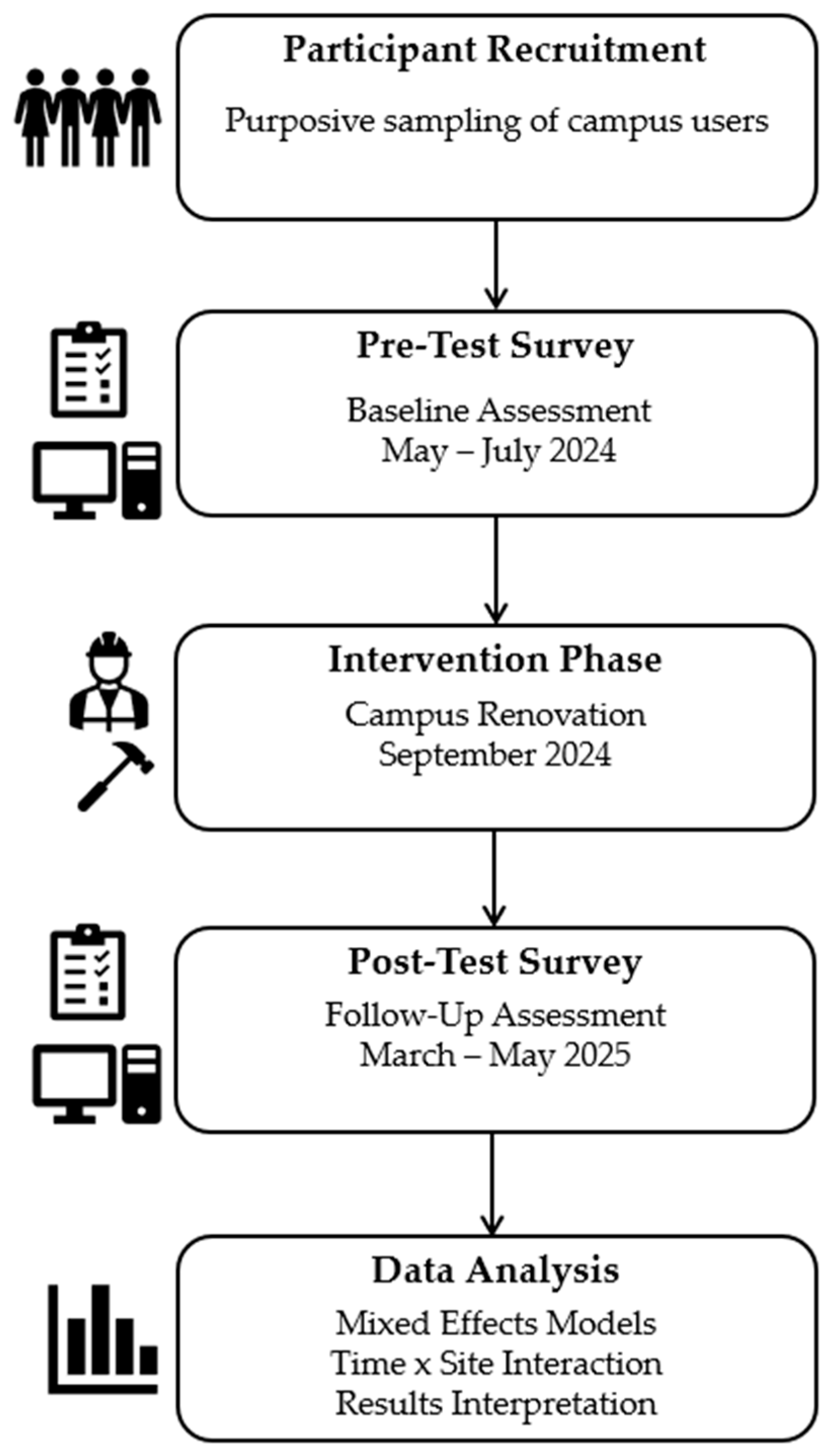

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

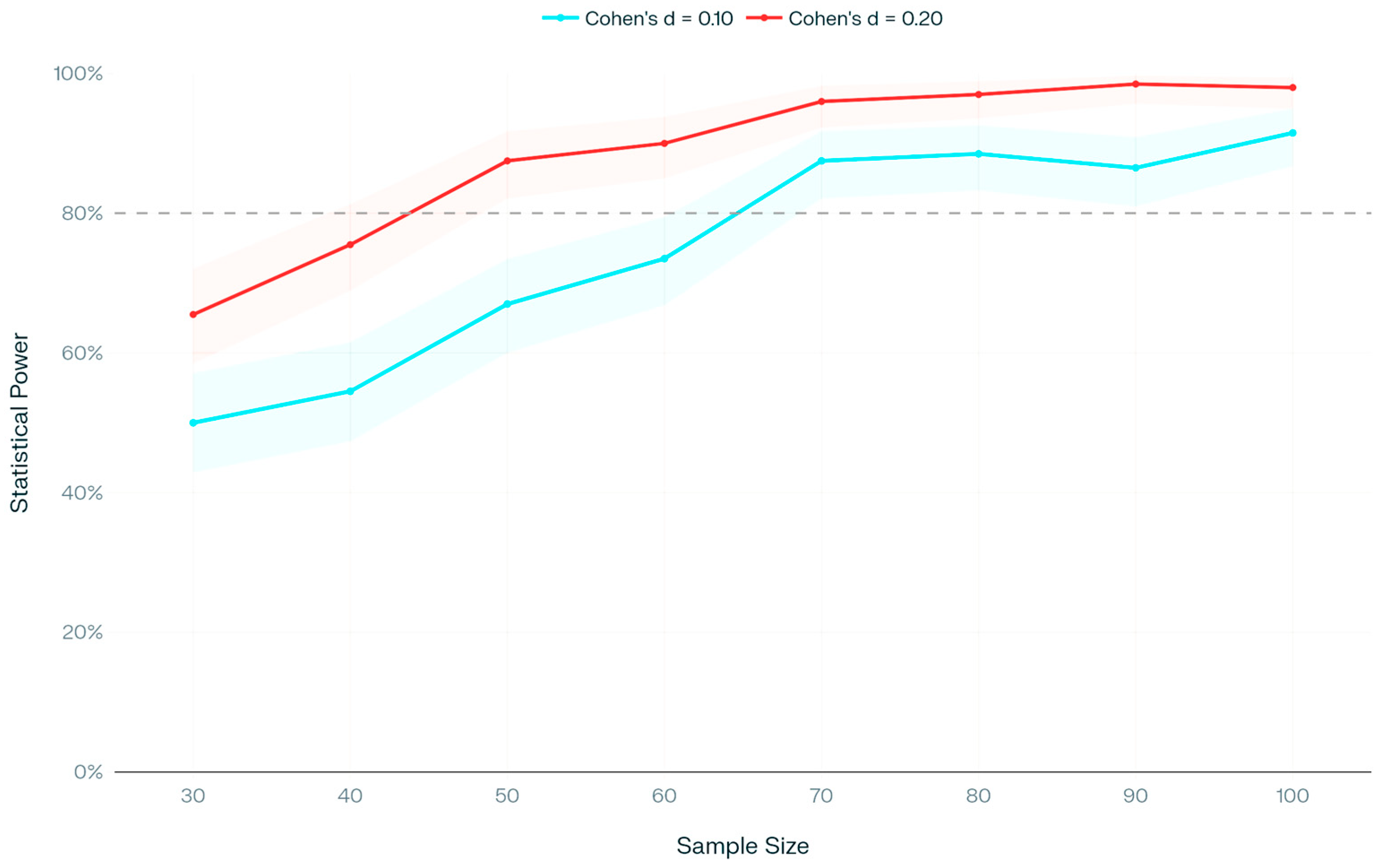

2.4. Data Analysis

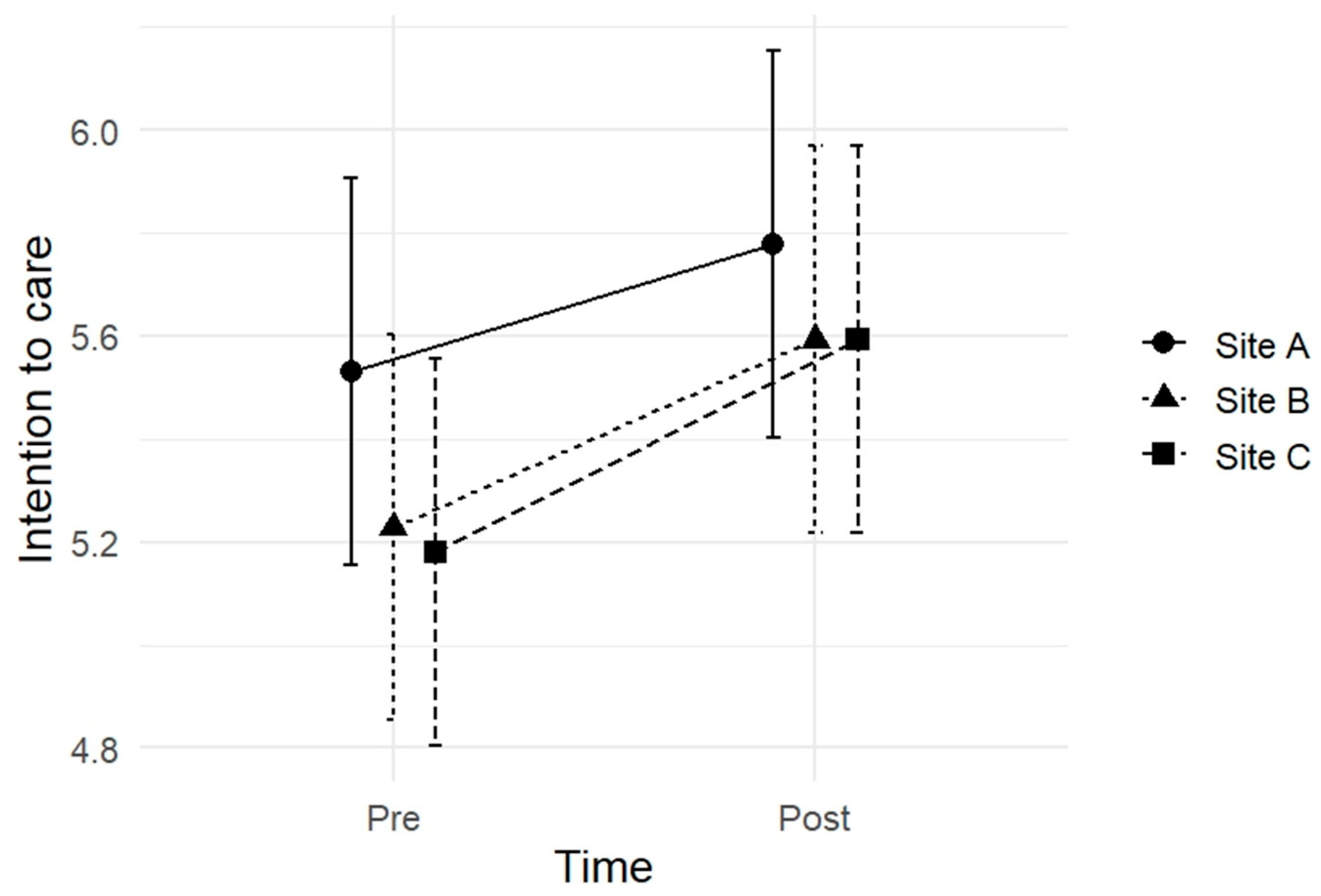

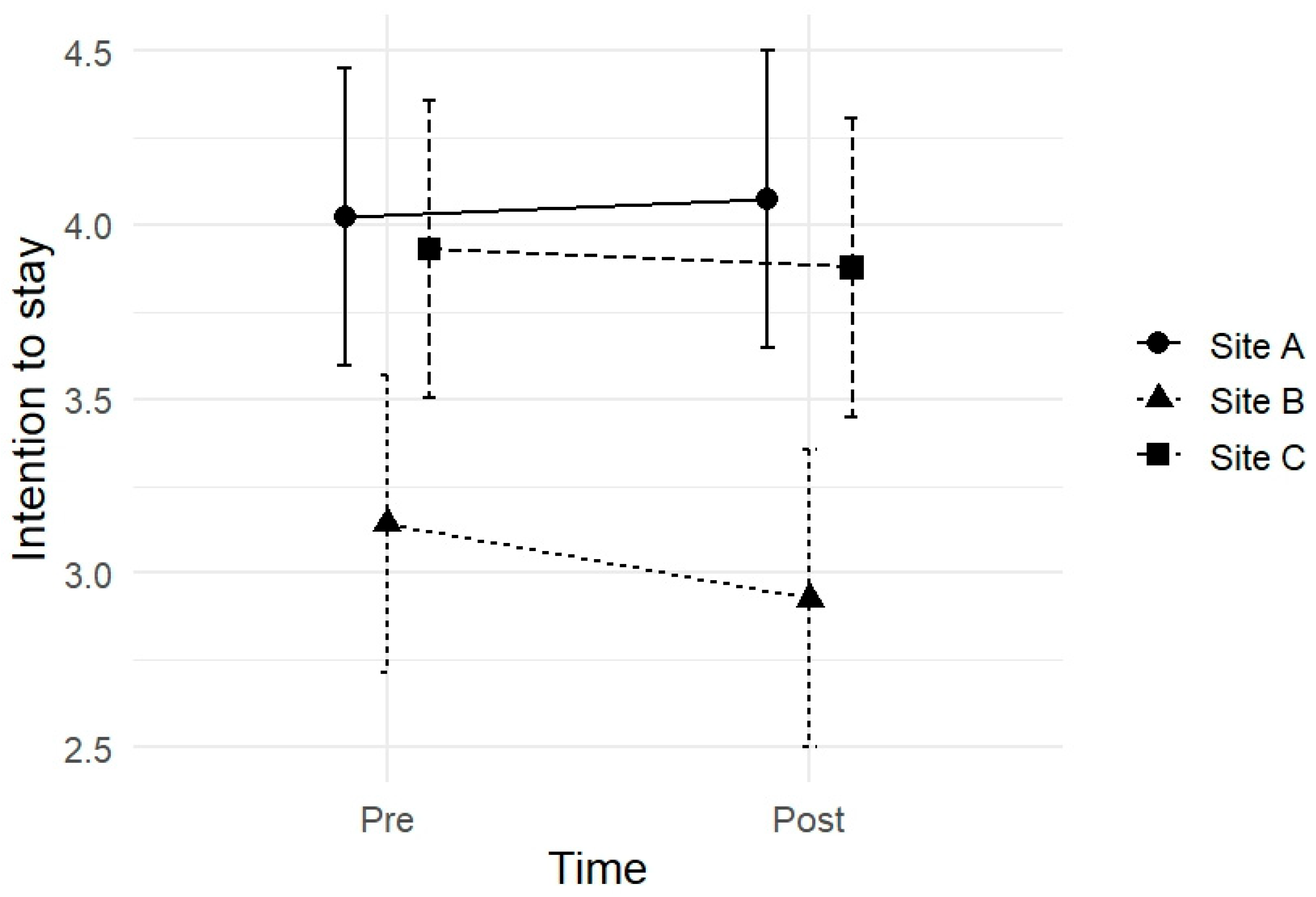

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lang, W.; Fu, D.; Chen, T. Exploring Self-Organization in Community-Led Urban Regeneration: A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Approaches. Land 2025, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Rocca, L.L. Urban Regeneration Processes and Social Impact: A Literature Review to Explore the Role of Evaluation. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2021: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12954, pp. 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H. A Review of Recent Studies on Sustainable Urban Renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, M. Urban Regeneration and “Resistance of Place”: Foregrounding Time and Experience. Space Cult. 2017, 20, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Cobbinah, P.B. Embedding place attachment: Residents’ lived experiences of urban regeneration in Zhuanghe, China. Habitat Int. 2023, 135, 102796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Zaccarelli, N.; Lara, A.; Sergi Cucinelli, F.; Aretano, R. A bottom-up and top-down participatory approach to planning and designing local urban development: Evidence from an urban university center. Land 2020, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L.; Hubbard, P. The emotional and psychological impacts of London’s ‘new’ urban renewal. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2020, 13, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alroy, K.A.; Cavalier, H.; Crossa, A.; Wang, S.M.; Liu, S.Y.; Norman, C.; Sanderson, M.; Gould, L.H.; Lim, S.W. Can changing neighborhoods influence mental health? An ecological analysis of gentrification and neighborhood-level serious psychological distress—New York City, 2002–2015. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. Urban regeneration involving communication between university students and residents: A case study on the student village design project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Principles for public space design, planning to do better. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blečić, I.; Cois, E.; Muroni, E.; Saiu, V. Spaces seeking activities-activities seeking spaces: Evaluation and policy design of neighbourhood-wide urban community spaces. City Cult. Soc. 2024, 39, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S. A Study on Urban Regeneration by Community Regeneration—Focussing on Community Regeneration Projects in the U.K. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2017, 33, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K.; Ison, R. Jumping off Arnstein’s ladder: Social learning as a new policy paradigm for climate change adaptation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piga, B.E.A.; Rainisio, N.; Stancato, G.; Boffi, M. Mapping the in-motion emotional urban experiences: An evidence-based method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.Y. Campustown Strategic Plan. Architecture 2018, 62, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C.; Yarker, S.; Hammond, M.; Kavanagh, N.; Phillipson, C. “Ageing in place” and urban regeneration: Analysing the role of social infrastructure. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küller, R. Environmental assessment from a neuropsychological perspective. In Environment Cognition and Action: An Integrated Approach; Garling, T., Evans, G.W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.A.; Johansson, M.; Sternudd, C.; Fornara, F. Transport walking in urban neighbourhoods. Impact of perceived neighbourhood qualities and emotional relationship. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2016, 150, 60–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Alves, S.; De Dominicis, S.; Petruccelli, I. Place attachment and natural hazard risk: Research review and agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviston, Z.; Dandy, J.; Horwitz, P.; Drake, D. Anticipating environmental losses: Effects on place attachment and intentions to move. J. Migr. Health 2023, 7, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Place value: Place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomoto, W.; Niñerola, A.; Pié, L. Social Impact Assessment: A Systematic Review of Literature. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 161, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lin, D.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J. Integrating street view images, deep learning, and sDNA for evaluating university campus outdoor public spaces: A focus on restorative benefits and accessibility. Land 2025, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Jiménez, A.; Lima, M.L.; Barrios-Padura, Á.; Molina-Huelva, M. Integrated urban regeneration based on an interdisciplinary experience in Lisbon / Regeneración urbana integrada basada en una experiencia interdisciplinar en Lisboa. PsyEcology 2020, 11, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manunza, A.; Giliberto, G.; Muroni, E.; Mosca, O.; Fornara, F.; Blečić, I.; Lauriola, M. “Build It and They Will Stay”: Assessing the Social Impact of Self-Build Practices in Urban Regeneration. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiboni, M.; Botticini, F.; Sousa, S.; Jesus-Silva, N. A systematic review for urban regeneration effects analysis in urban cores. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.; MacLeod, C.J. SIMR: An R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci, M. PATHj: Jamovi Path Analysis. 2021. [Jamovi Module]. Available online: https://pathj.github.io (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Jamovi (Version 2.6). Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Care and stewardship: From home to planet. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2011, 100, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 923464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L. The intention–behavior gap. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronello, C.; Gaborieau, J.B. Engaging in pro-environment travel behaviour research from a psycho-social perspective: A review of behavioural variables and theories. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Anh, T.; Nguyen, M.D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Duong, K.T. Energy saving intention and behavior under behavioral reasoning perspectives. Energy Effic. 2023, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, H.; An, Y.; Shi, Y.; Feng, X. Evaluating residents’ satisfaction before and after regeneration. The case of a high-density resettlement neighbourhood in Suzhou, China. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2144137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagsi, R.; Shapiro, J.; Weissman, J.S.; Dorer, D.J.; Weinstein, D.F. The educational impact of ACGME limits on resident and fellow duty hours: A pre–post survey study. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cap. Cl. 1998, 22, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, S.; Cantrill, J.G.; Myers, O.E. Place and the Promise of Conservation Psychology. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 100–112. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24706959 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ujang, N.; Zakariya, K. The notion of place, place meaning, and identity in urban regeneration. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, K.H. Designing for Diversity: Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Architectural Profession; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, L. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; Institute of Mathematical Statistics: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/foundations/snowball-sampling (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Gelo, O.; Braakmann, D.; Benetka, G. Quantitative and qualitative research: Beyond the debate. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2008, 42, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M.; De Lacey, S. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Site | Time | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | SE | Kurtosis | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to care | A | Pre | 54 | 5.53 | 5.67 | 1.34 | 1.67 | 7.00 | −0.798 | 0.325 | 0.062 | 0.639 |

| Post | 54 | 5.78 | 6.00 | 1.34 | 1.00 | 7.00 | −1.502 | 0.325 | 2.551 | 0.639 | ||

| B | Pre | 54 | 5.23 | 5.33 | 1.53 | 2.00 | 7.00 | −0.529 | 0.325 | −0.655 | 0.639 | |

| Post | 54 | 5.59 | 6.00 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 7.00 | −1.089 | 0.325 | 1.791 | 0.639 | ||

| C | Pre | 54 | 5.18 | 5.50 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 7.00 | −0.893 | 0.325 | 0.202 | 0.639 | |

| Post | 54 | 5.59 | 6.00 | 1.28 | 1.00 | 7.00 | −1.036 | 0.325 | 1.527 | 0.639 | ||

| Intention to stay | A | Pre | 54 | 4.02 | 4.17 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 7.00 | −0.105 | 0.325 | −0.908 | 0.639 |

| Post | 54 | 4.07 | 4.17 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 0.002 | 0.325 | −0.653 | 0.639 | ||

| B | Pre | 54 | 3.14 | 3.00 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 0.594 | 0.325 | −0.521 | 0.639 | |

| Post | 54 | 2.93 | 3.00 | 1.38 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 0.636 | 0.325 | 0.160 | 0.639 | ||

| C | Pre | 54 | 3.93 | 4.00 | 1.72 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 0.119 | 0.325 | −0.866 | 0.639 | |

| Post | 54 | 3.88 | 4.00 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 7.00 | −0.211 | 0.325 | −0.627 | 0.639 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Manunza, A.; Mura, A.L.; Lauriola, M.; Muroni, E.; Mula, S.; Giliberto, G.; Pirina, D.; Fornara, F.; Mosca, O. Self-Build Practices on University Campus: Socio-Psychological Effects on Care and Intention to Spend Time in Outdoor Spaces. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010023

Manunza A, Mura AL, Lauriola M, Muroni E, Mula S, Giliberto G, Pirina D, Fornara F, Mosca O. Self-Build Practices on University Campus: Socio-Psychological Effects on Care and Intention to Spend Time in Outdoor Spaces. Urban Science. 2026; 10(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleManunza, Andrea, Alessandro Lorenzo Mura, Marco Lauriola, Emanuel Muroni, Silvana Mula, Giulia Giliberto, Donatella Pirina, Ferdinando Fornara, and Oriana Mosca. 2026. "Self-Build Practices on University Campus: Socio-Psychological Effects on Care and Intention to Spend Time in Outdoor Spaces" Urban Science 10, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010023

APA StyleManunza, A., Mura, A. L., Lauriola, M., Muroni, E., Mula, S., Giliberto, G., Pirina, D., Fornara, F., & Mosca, O. (2026). Self-Build Practices on University Campus: Socio-Psychological Effects on Care and Intention to Spend Time in Outdoor Spaces. Urban Science, 10(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010023