Abstract

The agri-food sector is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions while facing increasing demand for food production driven by population growth. Transitioning towards sustainable and low-carbon agricultural systems is therefore critical. Green hydrogen, produced from renewable energy sources, holds significant promise as a clean energy carrier and chemical feedstock to decarbonize multiple stages of the agri-food supply chain. This systematic review is based on a structured analysis of peer-reviewed literature retrieved from Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, covering over 120 academic publications published between 2010 and 2025. This review provides a comprehensive overview of hydrogen’s current and prospective applications across agriculture and the food industry, highlighting opportunities to reduce fossil fuel dependence and greenhouse gas emissions. In agriculture, hydrogen-powered machinery, hydrogen-rich water treatments for crop enhancement, and the use of green hydrogen for sustainable fertilizer production are explored. Innovative waste-to-hydrogen strategies contribute to circular resource utilization within farming systems. In the food industry, hydrogen supports fat hydrogenation and modified atmosphere packaging to extend product shelf life and serves as a sustainable energy source for processing operations. The analysis indicates that near-term opportunities for green hydrogen deployment are concentrated in fertilizer production, food processing, and controlled-environment agriculture, while broader adoption in agricultural machinery remains constrained by cost, storage, and infrastructure limitations. Challenges such as scalability, economic viability, and infrastructure development are also discussed. Future research should prioritize field-scale demonstrations, technology-specific life-cycle and techno-economic assessments, and policy frameworks adapted to decentralized and rural agri-food contexts. The integration of hydrogen technologies offers a promising pathway to achieve carbon-neutral, resilient, and efficient agri-food systems that align with global sustainability goals and climate commitments.

1. Introduction

The agri-food and livestock sectors constitute one of the foremost challenges to environmental sustainability worldwide, accounting for nearly one-third of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, particularly within the so-called ‘farm gate’ through agri-food production activities [1,2]. Nevertheless, the rising demand for agricultural products driven by demographic growth projected to surpass 9 billion people by 2050 requires increased food production and, in turn, greater energy consumption. These dynamics highlight the urgent need to transition toward more sustainable agricultural systems and to integrate innovative energy technologies [3]. Renewable energy sources can expand access to energy, enhance energy security, reduce dependence on fossil fuels and mitigate GHG emissions. Within the agri-food sector, the principal renewable energy technologies include photovoltaics, wind, geothermal systems, biofuels, batteries and energy storage systems. Despite being recognized as one of the most promising decarbonization strategies, the large-scale production and deployment of green hydrogen (GH2) in the global energy system remains limited [4]. Climate change thus continues to pose a critical challenge.

The ecological degradation it causes progresses more slowly than that induced by other drivers, such as land-use change and pollution, yet it entails long-term impacts on the environment, agro-ecosystems and, ultimately, significant economic and social implications for food security and nutrition [5,6]. Since the release of the most recent panel report, climate governance has increasingly concentrated on legislation designed to curb GHG concentrations in the atmosphere, complemented by related indirect measures [7]. Among the principal global initiatives addressing climate change, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development endorsed in September 2015 by 193 United Nations member states sets forth an integrated framework for action on people, the planet and prosperity, encompassing 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 associated targets [8,9]. In Europe, the European Commission has set the objective of achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, grounded in the development of a secure, sustainable and competitive energy system that incorporates renewable energy, substitution of end-use fuels and carbon capture and storage [10]. To reach these climate goals, emissions from the agri-food supply chain including production, processing, distribution and consumption must be substantially reduced [11,12,13,14]. At present, to extend the shelf life of food products and limit the need for continuous new production, preservation processes such as cooking, drying, pasteurization, refrigeration and sterilization are widely employed. These techniques improve resistance to microbial spoilage and reduce lipid oxidation, thereby slowing natural decomposition and rancidity [15].

Hydrogen, when used as a clean energy carrier, offers the potential to replace fossil fuels across various stages of the agri-food chain, ranging from energy supply for machinery and transport to fertilizer production, heating and food processing. Although hydrogen production is widely recognized as a promising energy technology, only a limited number of case studies have thus far demonstrated its deployment from renewable energy sources to achieve significant reductions in GHG emissions [16,17]. Nevertheless, it represents a critical energy resource to support and accelerate the transition toward a low-carbon economy. Accordingly, after a concise overview of regulatory and technological background, the review focuses on hydrogen applications in agriculture and the food industry, which constitute the core contribution of this work, with particular attention to the advantages and limitations of its current and prospective uses. The literature search was carried out using Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar to ensure comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed publications. Searches were performed using combinations of keywords including “green hydrogen”, “renewable hydrogen”, “agriculture”, “livestock”, “agri-food sector”, “fertilizer production”, “food industry”, “agricultural machinery”, and related terms.

The search covered publications from approximately 2010 to 2025, reflecting the period during which green hydrogen technologies and their potential applications in agriculture and food systems have been most actively investigated. Only peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers published in English were considered. Studies were included when they explicitly addressed hydrogen production, conversion, or use in agricultural, livestock, or food-system contexts. Publications focusing on hydrogen technologies without relevance to agri-food systems were excluded.

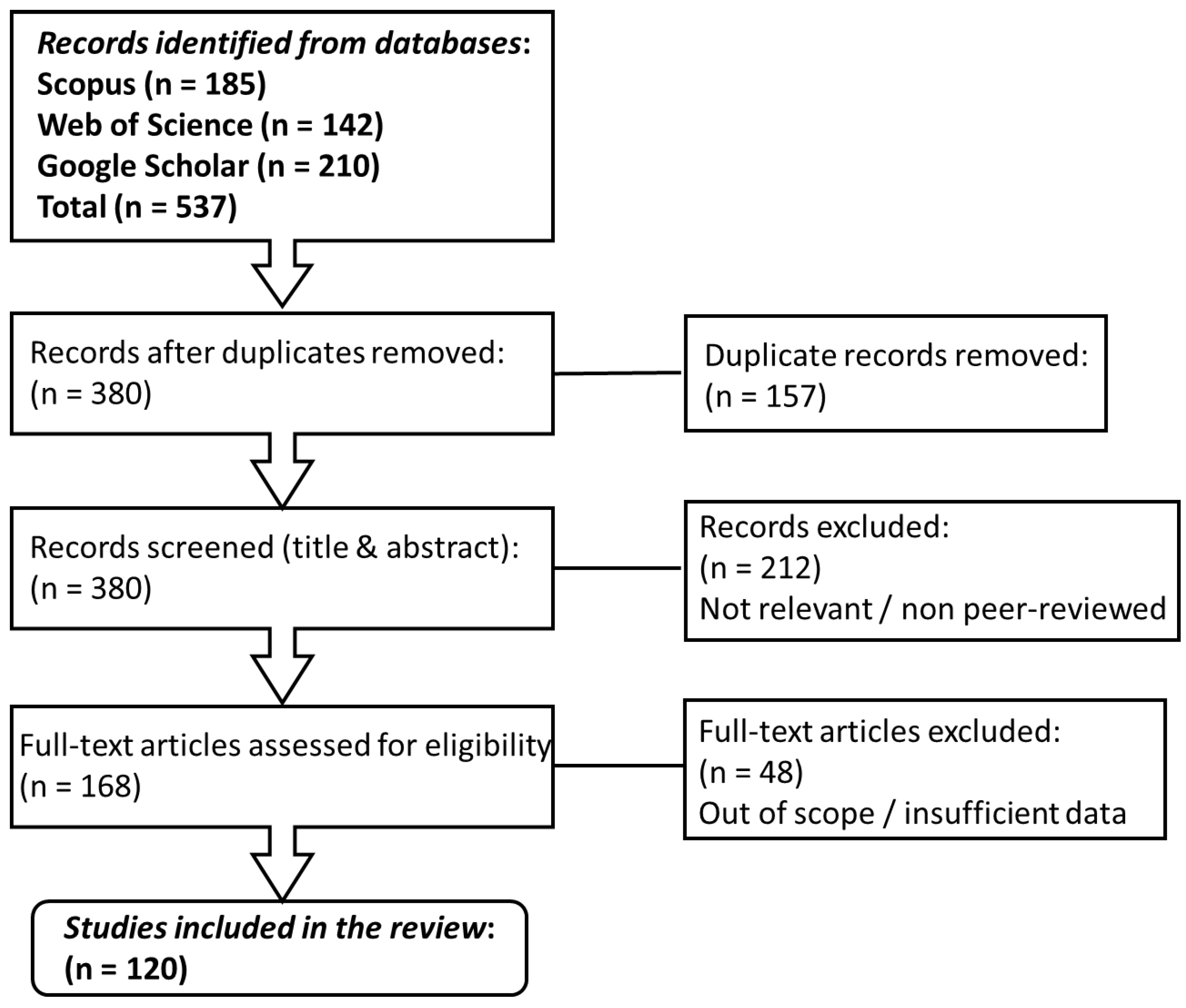

Following the database searches, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and the full texts of selected articles were assessed against the inclusion criteria. Reference lists of key publications were also examined to identify additional relevant studies. An overview of the literature identification, screening, and selection process is provided in the flow chart illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the literature identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion process for this systematic review (Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar).

Experimental applications of hydrogen derived from renewable energy sources have already been explored in agricultural vehicles. However, the substitution of certain vehicles or machinery used in vineyards with electric traction alternatives is not yet widely available, including for greenhouse and hydroponic systems. For instance, in a vineyard in north-eastern Spain, Caroquino and colleagues implemented a renewable energy system [18]. Energy generated from photovoltaic fields already supports or has entirely replaced the power supply for wastewater treatment plants in several wineries, irrigation systems and other auxiliary operations.

Greenhouses represent another important aspect of modern agriculture, particularly in regions with unfavourable climatic conditions for plant growth; nevertheless, such systems are highly energy-intensive. Ganguly and colleagues [19] modelled and analyzed an integrated energy system combining photovoltaics, an electrolyzer and a fuel cell (FC) for a floriculture greenhouse. Similarly, Pascuzzi and colleagues [20] constructed an experimental self-sufficient greenhouse comprising photovoltaic panels, a water electrolyzer, FCs, pressurized hydrogen tanks and a geothermal heat pump. Yamaguchi and colleagues [21] developed a small-scale hydroponic system for lettuce cultivation, powered by renewable energy and regulated by a hybrid system combining a hydrogen FC with a lead-acid battery. More recently, Swaminathan and colleagues [22] designed and implemented an automated hydroponic system for urban agriculture, integrating a solar panel, an electrolyzer and a FC. In this system, hydrogen produced via solar-powered water electrolysis during daylight hours was stored for use by the FC in the absence of sunlight, while waste heat was utilized to maintain optimal plant temperatures [23].

2. General Aspects

2.1. Regulatory Framework and Emissions Standards for Agricultural Machinery

The deployment of alternative fuels and powertrains in agriculture is strongly influenced by the regulatory framework governing pollutant emissions from non-road mobile machinery (NRMM). In the European Union, agricultural tractors and machinery are regulated under EU Regulation 2016/1628 (Stage V) [24], which establishes limits for nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter (PM), particle number (PN), hydrocarbon (HC), and carbon monoxide (CO) across different engine power classes.

Compared with previous regulatory stages, Stage V introduces more stringent PM and PN limits and extends coverage to a wider range of engine categories, thereby tightening emission constraints for both conventional diesel engines and alternative-fuel machinery. The main emission thresholds applicable to agricultural engines are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Emission limits (L) expressed in grams for kilowatt hour (g/kWh) and the Particle Number (PN) limit expressed in number of particles per kilowatt hour (#/kWh), as established by Regulation (EU) 2016/1628 [24].

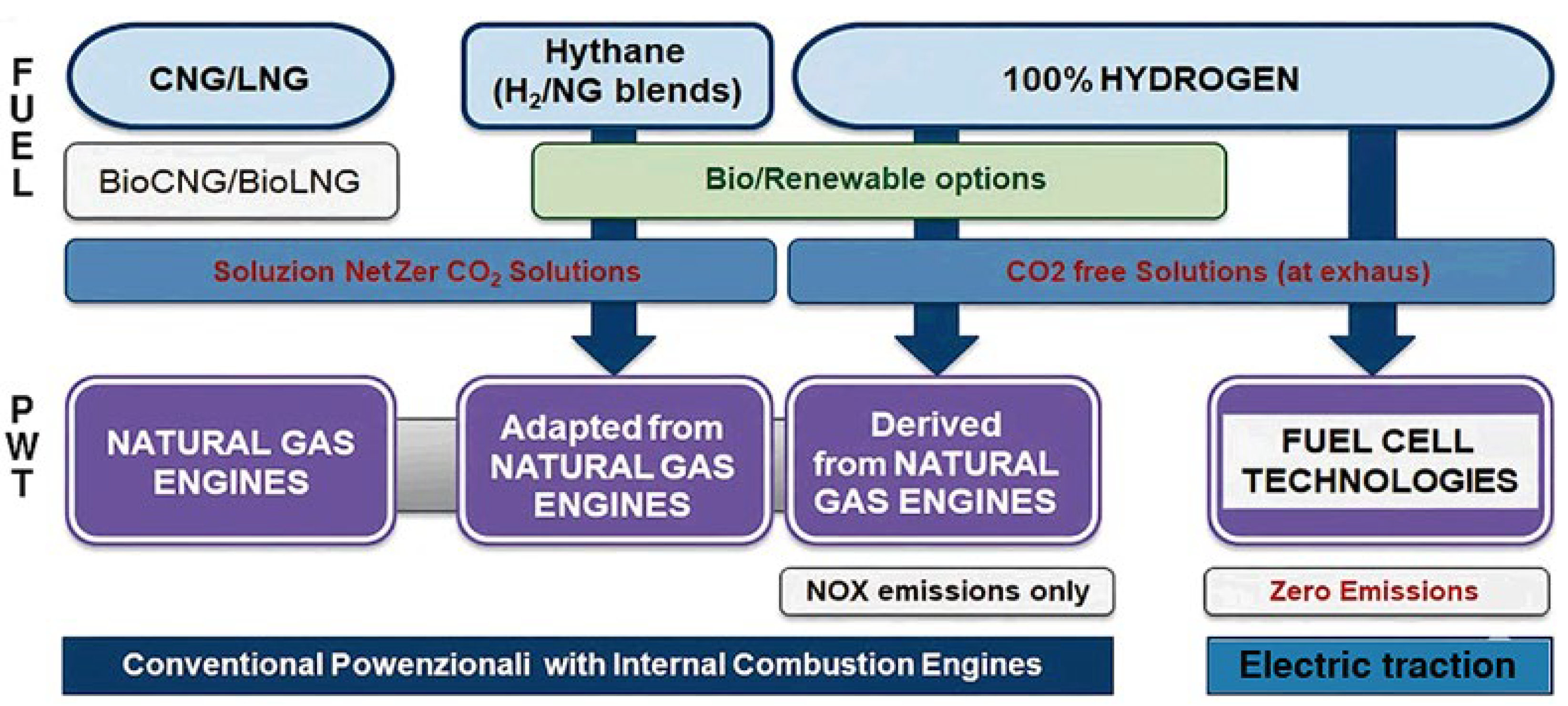

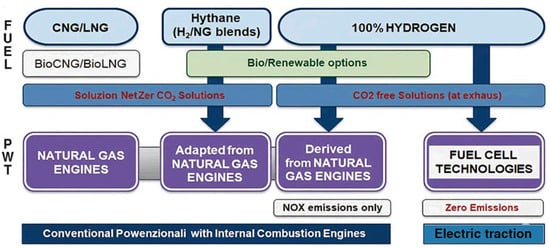

In parallel, current decarbonization strategies increasingly promote the use of gaseous fuels—such as natural gas, hydrogen, and their blends—as transitional or long-term options for reducing exhaust emissions, as schematically illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Solutions based on the use of gaseous fuels (natural gas, hydrogen and blends) in relation to the decarbonisation objective.

Within this regulatory context, hydrogen and hydrogen-containing fuels are of interest primarily for their potential to reduce exhaust emissions at the point of use, particularly with respect to particulate matter and carbon-based pollutants. However, regulatory compliance alone does not determine technology uptake in agriculture; practical considerations such as system cost, durability, refuelling infrastructure, and operational suitability under field conditions remain decisive. Against this regulatory backdrop, the potential contribution of hydrogen-based solutions in agriculture ultimately depends on how hydrogen is produced, supplied, and integrated into agri-food systems; the main hydrogen production pathways and their relevance to agricultural and food-sector applications are therefore outlined in the following section.

2.2. Brief Overview of the Current Hydrogen Production Technologies

Hydrogen (H2) can be produced through a range of thermochemical, electrochemical, and bio-based pathways, which differ markedly in technological maturity, carbon intensity, and suitability for integration into agri-food systems through a variety of processes [25,26,27,28,29]. At present, global hydrogen production remains dominated by fossil-based routes, primarily SMR and coal gasification, which together account for the vast majority of supply (98%) but are associated with substantial GHG emissions [25,30]. Electrolysis contributes only a small but rapidly growing share of production. Indeed, from a decarbonisation perspective, water electrolysis powered by low-carbon or renewable electricity represents the most relevant route for GH2 production [16,17,31,32,33,34]. Among electrolysis technologies, alkaline water electrolysis (AWE) and proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis [35,36,37,38] are currently the most commercially mature and have been deployed at industrial scale [39,40], whereas solid oxide electrolysis (SOE) remains at the demonstration or early commercial stage [41,42,43,44]. Although PEM electrolysis remains cost-constrained, significant advantages are still expected, such as an ergonomic layout, high current density (>2 A cm−2), excellent efficiency, rapid response, compact footprint and the ability to operate at low temperatures (20–80 °C) [45]. Another issue is that while electrolysis produces hydrogen without direct CO2 emissions at the point of production, its life-cycle carbon footprint depends strongly on the electricity mix, and substantial emission reductions are achieved only when low-carbon or renewable power sources are used [46,47,48,49,50]. Therefore, truly carbon-neutral or carbon-negative H2 can only be achieved when the process is coupled to the avoidance or capture of CO2 that would otherwise be emitted, for example, through biomass-derived feedstocks combined with carbon capture or co-production routes. In the agri-food sector, O2 generated during electrolysis can support processes such as wastewater sludge treatment, aerobic composting and aquaculture tank oxygenation [51], while waste heat can be recovered for greenhouse and fish-tank heating, enhancing overall sustainability [52]. Electroreforming (anodic electro-oxidation of biomass derivatives coupled with cathodic hydrogen evolution) is a promising route to co-produce GH2 and value-added chemicals; recent demonstrations include electroreforming of chitin (shrimp-shell waste) and of lignocellulosic residues at lab/pilot scale [53,54,55]. However, H2 production from organic matter is still largely limited to the industrial sector due to high costs and low technological maturity [56]. Recent innovative bio-electrochemical technologies, such as Microbial Electrolysis Cells (MECs), require relatively low external energy input, can process a wide range of organic materials and can treat pollutants [57]. In MEC systems, electrochemically active microorganisms serve as catalysts, enhancing sustainable hydrogen production [58,59,60,61].

2.3. Challenges in Green Hydrogen Production

Globally, GH2 is expected to become a traded commodity in terms of GHG emission reduction, contingent upon comprehensive lifecycle assessments to inform effective policies. Nonetheless, the production and management of hydrogen pose critical challenges, including high capital costs for electrolyzers, integration complexities with variable renewable energy sources and substantial energy requirements for compression, storage and transport [62,63]. These challenges include the variability and intermittency of electricity generated from renewable sources, modelling limitations, constraints related to electrolyzer capacity, lifetime and performance characteristics, operational costs, storage and safety considerations and overall electrolyzer efficiency [64,65]. Safety risks also arise from hydrogen’s high flammability and low ignition energy, necessitating advanced safety protocols [66,67]. Although GH2 can be produced from renewable sources such as wind and solar, the instability of electricity supply remains a significant challenge [61,68]. Bakhtiari and Naghizadeh [69] identified low solar irradiation and low wind speeds as key limitations for single-source hybrid renewable systems. The inherent adaptability of electrolysis technology, however, facilitates the integration of multiple renewable energy sources [70,71]. Further analyses are needed to optimize complex electrolysis plants operating under variable and irregular electricity production, whether powered entirely by wind or photovoltaic systems and whether grid-connected or off-grid. Future research should focus on dynamic modelling of electrolyzers validated through experimental pilot-plant tests, to enhance their performance, reliability and scalability [72,73].

3. Advantages of Green Hydrogen Compared with Conventional Fuels

The increasing urgency to achieve climate objectives assigns hydrogen a pivotal role, particularly in attaining carbon neutrality in sectors that are currently challenging to decarbonize. GH2 produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy sources is emerging as a critical resource for the energy transition, especially in agriculture [74] and the food industry [3]. Advances in electrolyzer technology are essential for enabling large-scale and cost-competitive deployment, particularly in regions endowed with abundant renewable energy resources to support GH2 production [75]. Hydrogen is often considered a promising option within broader low-carbon energy strategies, especially for hard-to-abate sectors, but its overall role remains uncertain and contingent on technological, economic, and policy developments [76]. It serves as both an energy carrier and a chemical feedstock, representing one of the fundamental pillars of the energy transition [77,78].

Nevertheless, despite increasing research activity, the practical deployment of hydrogen technologies across the agri-food sector is still at an early stage, with most applications restricted to small-scale demonstrations or feasibility studies.

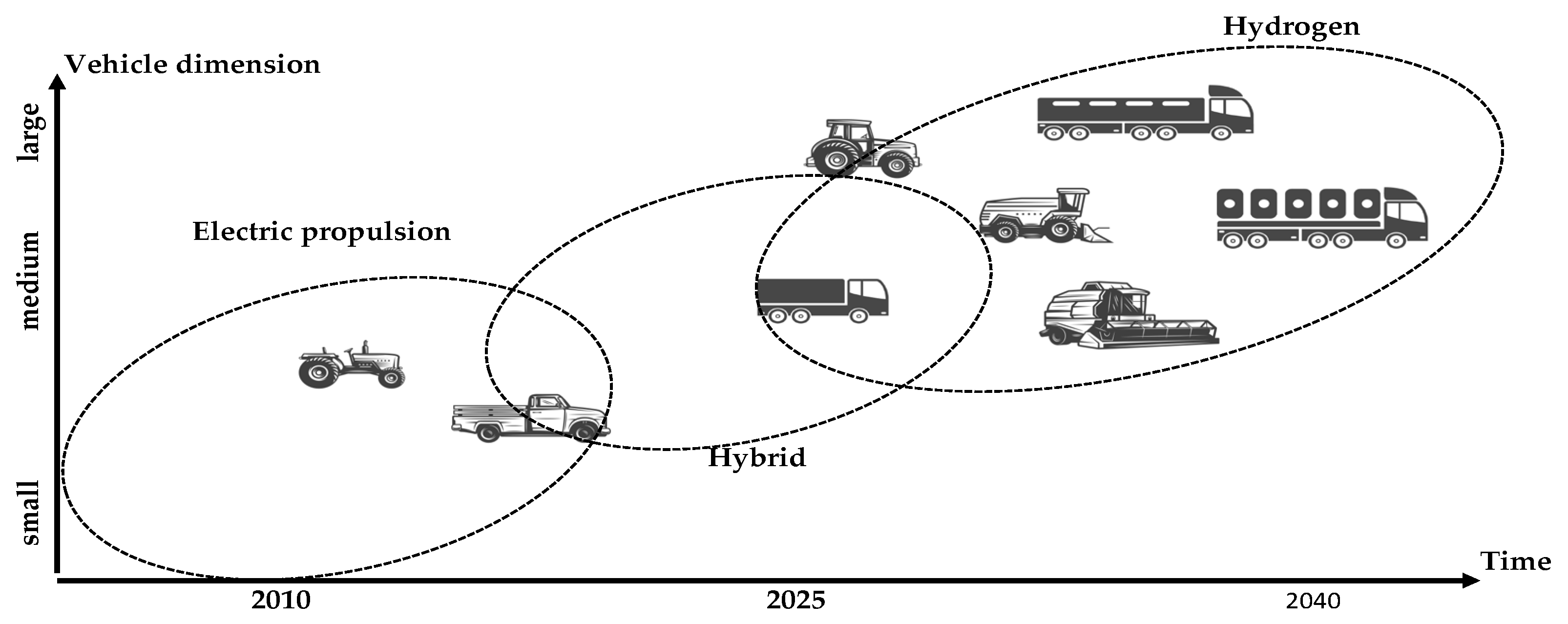

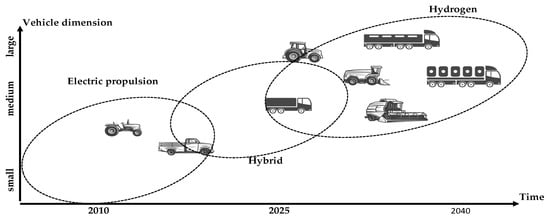

Hydrogen propulsion systems primarily rely on two energy conversion technologies: hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) and internal combustion engines (ICEs) (Figure 3). FCVs, which convert hydrogen into electrical energy for propulsion, currently represent the most commercially mature approach. Tank-to-wheel (TtW) efficiency for FCVs is estimated between 31% and 36%, with water vapour as the sole emission [79,80]. Toyota, Honda and Hyundai have already commercialized FCVs in select markets, with over 6500 units sold by June 2018 [81,82]. A prototype FC truck, offering a range of 480 km, was recently introduced by Toyota and Kenworth [83], demonstrating the potential to replace ICE technology in future heavy-duty applications.

Figure 3.

Overview of hydrogen and biomethane energy pathways in agriculture.

Hydrogen storage remains a critical challenge in the development of FCVs. Due to hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density, storing sufficient quantities on board to achieve adequate driving range without excessive tank size or weight is difficult. Pressurized tanks with robust carbon fibre-lined cylinders, including impact-resistant designs for collision safety, have been developed. For instance, compressed H2 has been stored at 34 MPa with a mass of 32.5 kg and a volume of 186 L, sufficient for a driving range of approximately 500 km [84]. This tank volume corresponds to roughly 90% of a 55-gallon drum, representing a significant spatial constraint for individual vehicles; even if a 6% weight target is met, tank size remains a concern. These limitations continue to represent a major engineering bottleneck for large-scale adoption in agricultural and off-road machinery, where space constraints are even more restrictive than in passenger vehicles [85].

Although H2 Port Fuel Injection (H2PFI) systems can achieve competitive peak efficiencies, they face limitations that can be addressed by advanced Direct Injection Systems (DISs). BMW and partners demonstrated the potential of DIS technology in 2009, developing a DIS fuelled by hydrogen with injection pressures up to 300 bar, integrated into a spark-ignition (SI) engine, achieving a maximum efficiency of 42%, comparable to turbo-charged diesel engines [86,87].

Leveraging the potential of hydrogen engines, Mazda has developed a rotary hydrogen engine integrating both PFI and DI technologies since 2006, applied to a sports car model with an extended driving range of 649 km [88,89,90]. Despite these advances, reliance on H2 as a clean energy source necessitates careful consideration of its production origin to ensure genuine environmental benefits. While the majority of hydrogen mobility research has focused on road transport, many of the resulting technologies, such as high-pressure storage and direct-injection systems, can be transferred to agricultural machinery to achieve low-emission operation.

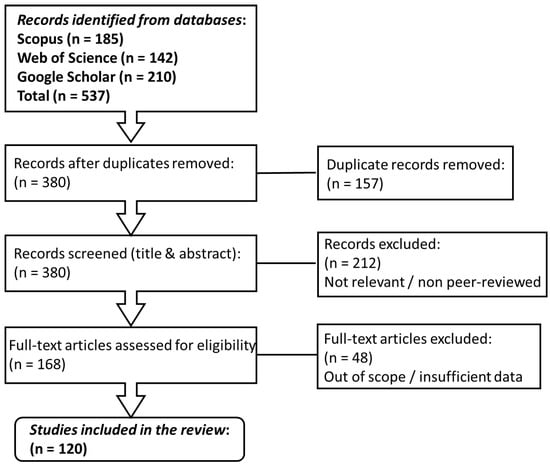

Hydrogen in the Agricultural and Forestry System

Numerous studies have examined efforts to decarbonize agricultural and forestry machinery. Brenna et al. [91] estimated the dimensions of the main components of an electric tractor and compared its operating costs with those of conventional diesel tractors. The study showed that annual electricity expenditures and other operational and maintenance costs are lower for electric tractors, suggesting that battery-electric tractors with performance comparable to traditional diesel models are technically and economically feasible. Currently, capital expenditures for battery electric vehicles (BEVs) remains higher than that of ICE vehicles due to the higher cost of batteries although these costs are expected to decrease substantially with technological advances and production scaling. Lagnelöv et al. [92] evaluated the use of autonomous battery electric tractors on a Swedish farm. They reported a 58% reduction in annual final energy consumption compared to conventional diesel tractors, with total costs approximately 15% lower. The largest cost reductions were observed in labour requirements, but reductions in tractor costs excluding battery costs were also significant. The study concluded that a system combining autonomous control with battery-electric propulsion can contribute to overall cost savings.

However, fully autonomous tractors capable of handling all agricultural operations do not yet exist. Inventory data for autonomous vehicles are limited and data for tractors are even less available than for heavy road vehicles. It was therefore assumed that data from other vehicle types could be scaled and adapted for autonomous tractor systems, particularly regarding vehicle electrification and autonomy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Components included in life cycle assessment (LCA) of the battery electric vehicle (BEV) and internal combustion engine (ICE) cases. Categories marked with * were included, but to a reduced extent.

In his 1990 article, Das examined ICEs fuelled by hydrogen (H2 ICE) tracing their development back to the 1930s and highlighting key characteristics of hydrogen combustion [93]. These include the potential for very low emissions, load control via variation in the air-fuel ratio variation and a tendency toward abnormal combustion phenomena such as backfiring, pre-ignition and knock.

In 1998, Peschka [94] published an influential article although not a review, illustrating numerous ideas on glow-ignition DI operation, which were subsequently explored in greater detail by Eichlseder et al. [95]. They provided a thorough synthesis of theoretical foundations before reporting the first “modern” experimental comparison between PFI and DI, along with a discussion of load-control strategies to optimize the balance between efficiency and emissions. In 2006, White et al. [86] and Verhelst et al. [96] published review articles that, collectively, summarized the most significant findings from a large body of literature. Subsequently, Verhelst and Wallner [97] provided perhaps the most comprehensive review to date. One of the final sections of their article, which summarizes unresolved research and development challenges, serves as a reference point for the present review.

In Europe, the three-year integrated HyICE project (2004–2007) reported by Werhelst in his 2014 review [98] demonstrated hydrogen engine concepts exceeding 100 kW/L of specific power and achieving peak efficiencies of about 42%. Funded under the European Commission’s Sixth Framework Programme and coordinated by BMW, the consortium comprised both industrial and academic partners. The project investigated hydrogen’s potential in single- and multi-cylinder engines, employing both DI and cryogenic PFI, developed 1D and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modelling tools, designed DI injectors and explored optical measurement techniques to elucidate the peculiarities of hydrogen combustion in engines. Although HyICE predates the temporal scope defined for this review, it is explicitly referenced as it initiated several research directions that laid the foundation for much subsequent work.

4. Agriculture Applications

Hydrogen technology in agriculture is increasingly recognized for its potential to promote sustainable and environmentally friendly farming. Its applications are both current and rapidly expanding for future use. The recent survey by Kuranc et al. [99] reviews relevant European policies like the European Green Deal and “Fit for 55” strategy encouraging hydrogen infrastructure and low-emission technology adoption to support the decarbonization of the agricultural sector. Below, some agricultural sectors that could benefit from H2 technology are briefly reviewed. Despite promising experimental results, most of these applications remain limited to controlled or pilot-scale conditions.

4.1. Hydrogen-Rich Water Treatments

Hydrogen-Rich Water (HRW) treatments significantly extend the shelf life of perishable products by modulating antioxidant metabolism. Indeed, a hydrogen supply system can improve tolerance to abiotic and biological stresses, regulate plant growth and development, improve nutritional quality, prolong both the shelf life of fruits and the in bottle-life of fresh-cut flowers [100,101]. HRW irrigation has demonstrated significant improvements in water efficiency, crop resilience and enhanced seed germination, root development, and nutrient uptake while reducing oxidative stress. For instance, wheat treated with HRW exhibited a 15–24% increase in root/shoot length and improved drought resistance [102]. In fruit preservation, it has been reported that HRW (0.6 mM) reduces rot incidence in kiwifruit by 40% by suppressing pectin-degrading enzymes (polygalacturonase and cellulase) and enhancing superoxide dismutase activity while HRW maintains ascorbic acid levels in Rosa roxburghii by upregulating glutathione-ASA cycle genes [3,103]. Other studies investigated how HRW treatment affects plant growth, ion absorption, osmotic and oxidative stresses, antioxidant enzyme levels, hormone levels and root endophytic bacteria in strawberry seedlings under salt stress [104].

4.2. Fertilizers

GH2 could potentially revolutionize fertilizer production by decarbonizing ammonia synthesis. Conventional ammonia synthesis is still overwhelmingly carried out via the Haber–Bosch process, using hydrogen mainly derived from natural gas. There is growing research interest in low-temperature, low-pressure electrochemical routes and in ‘green ammonia’ produced from renewable hydrogen, but these alternatives are currently at laboratory or pilot scale and represent a negligible fraction of global output [105]. In the medium term, the more realistic decarbonisation pathway is to couple existing or modified Haber–Bosch plants with low-carbon hydrogen (e.g., from electrolysis powered by renewables), thereby reducing the carbon intensity of fertilizer production rather than replacing Haber–Bosch itself. Life-cycle assessment studies indicate that replacing SMR-derived hydrogen with electrolytic hydrogen produced using low-carbon or renewable electricity in the Haber–Bosch process can reduce cradle-to-gate greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 55–90%, depending on electricity carbon intensity, system boundaries, and process assumptions. Such configurations have also been discussed as a potential pathway toward decentralized or farm-scale fertilizer production, although these concepts remain at an early or pilot stage of development [106,107,108]. Recent innovations also focus on integrating hydrogen-derived green ammonia with precision agriculture to minimize nitrogen runoff [109].

4.3. Waste-to-Hydrogen

Several waste-to-hydrogen pathways have been investigated as part of broader efforts to advance energy-efficient, low-emission agri-food systems while supporting circular resource utilization. Agricultural and food residues represent a diverse feedstock pool—including lignocellulosic crop residues, manure, and organic food waste—that can be converted into hydrogen through thermochemical, biological, electrochemical, or hybrid processes, depending on moisture content, scale, and local integration opportunities.

Thermochemical routes, such as gasification and reforming of agricultural residues and biogas, are among the most mature waste-based hydrogen pathways. In agricultural contexts, anaerobic digestion of manure and crop residues is already widely deployed, producing biogas typically composed of approximately 50–60% methane, with minor hydrogen fractions that can be further upgraded through reforming processes [110]. For instance, a study conducted in Hokkaido, Japan assessed the implementation of biogas plants (BGPs) fueled by cattle manure across 139 municipalities [111,112]. The siting of centralized BGPs was optimized using a Geographic Information System (GIS) and initial and annual costs, energy generation and GHG emission reductions were estimated. The total initial and annual costs for 330 centralized BGPs were estimated at USD 8162 million and USD 1089 million (1 USD = 80 JPY), respectively. These plants were projected to generate between 150 and 390 GWh of excess energy and between 490 and 730 GWh of total energy, sufficient to power approximately 34,000–86,000 households (1.3–3.3% of total households in Hokkaido in 2007). Annual GHG emission reductions were estimated at 1.07–1.2 Mt CO2-equivalent (1.5–1.7% of total emissions in Hokkaido). The economic feasibility of centralized BGPs was constrained by the low purchase price of renewable electricity, which must reach at least USD 1900 MWh−1 for viability in more than half of the municipalities.

While these routes are technically feasible, their overall environmental performance depends on feedstock logistics, gas cleaning requirements, and the integration of carbon management strategies.

Biological and bio-electrochemical approaches are particularly relevant for wet and heterogeneous agri-food waste streams, such as food-processing residues, wastewater, and slurry. Dark fermentation, photo-fermentation, and microbial electrolysis cells enable hydrogen production under relatively mild operating conditions, albeit currently at low yields and limited scales. These technologies are therefore best suited for decentralized or niche applications and remain largely at laboratory or pilot stages. More recently, electrochemical and hybrid waste-to-hydrogen concepts have attracted attention for their potential to couple hydrogen production with the valorization of biomass-derived intermediates. Projects such as AGRI-WASTE2H2 demonstrate how straw-derived cellulose can be electro-converted into hydrogen while simultaneously producing value-added platform chemicals, thereby improving overall process economics [113].

Additionally, circular integration strategies, such as coupling food waste fermentation units with hydrogen FCs, enable on-site renewable energy production for agricultural operations, thereby reducing reliance on grid power and enhancing local energy self-sufficiency [114]. Recent comprehensive reviews have examined biomass-to-biohydrogen conversion pathways, including thermochemical, biological, and hybrid systems, highlighting both their potential contribution to low-carbon hydrogen supply chains and the persistent challenges related to scalability, efficiency, and system integration [28,115,116]. Overall, waste-to-hydrogen technologies appear most promising when deployed as complementary, site-specific solutions within agri-food systems—particularly where waste management, energy demand, and by-product valorisation can be jointly optimized—rather than as stand-alone large-scale hydrogen production routes.

5. Food Industry Applications

Hydrogen plays a crucial role in fat hydrogenation, improving food packaging and preservation, acting as a reducing agent and providing sustainable energy for food processing, thus helping improve product quality and shelf life while supporting industry sustainability goals [117]. In the food industry, hydrogen is used both in food production processes and as a packaging gas. Hydrogen is mainly used in the production of margarine and frying fats. This allows products to have the desired consistency and a longer shelf life. Hydrogen is also often used as a protective gas in food packaging to protect products from oxidation. In addition, it prolongs the freshness of some products, such as meat and seafood, by inhibiting bacterial growth.

5.1. Hydrogenation of Fats and Oils

Hydrogen is widely used to hydrogenate vegetable oils, converting liquid oils into semi-solid or solid fats like margarine and shortening. This improves texture, consistency, and shelf life of food products [118]. Recent catalysis literature emphasizes that modern edible-oil hydrogenation increasingly prioritizes selectivity control (maximizing desired mono-unsaturated products while minimizing trans-isomer formation), motivating continued research into catalyst design and process optimization [119].

5.2. Packaging: H2-Modified Atmospheres

Hydrogen gas, listed as a food additive with the number E 949, is used in modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) or reducing atmosphere packaging (RAP), where it helps protect food from oxidation and microbial growth, thereby extending freshness and shelf life. This is especially effective for perishable products such as cheese, strawberries, fish and meat [120]. For instance, RAP (10% H2, 4% CO2, 86% N2) extends shelf life by 3–5 times versus controls and 1.5–3 times versus MAP. It preserves firmness, anthocyanins (15–30% higher) and antioxidant capacity during 12 weeks of storage at 4 °C [121]. However, H2-MAP/RAP should be framed as an emerging, product-specific concept, because practical implementation requires careful consideration of safety, concentration limits, packaging integrity and risk management, given hydrogen’s flammability. A recent review also emphasizes that broader adoption will depend on robust validation across food categories and standardized protocols [117].

5.3. Food Waste Valorisation

Food-to-hydrogen (F-to-H2) conversion technologies enable circular energy systems. They are used to convert food waste into H2, focusing on biological and thermochemical routes such as anaerobic digestion, fermentation and gasification, thus highlighting the efficiency and potential of food waste as a biomass for GH2 production [122]. Several studies discuss innovative biological techniques like dark fermentation to convert food waste into biohydrogen with high yields under optimized conditions [123]. The paper by Seglah et al. [124] presents anaerobic digestion and steam-reforming technologies applied on food waste to generate H2-rich gas streams, emphasizing the role of bacterial communities and operating parameters on yield. Another study explores the feasibility of producing H2 gas from kitchen food waste (potato peel, watermelon rind) by dark fermentation and simultaneously producing nutrient-rich biochar as a valuable byproduct [125]. A recent analysis examines economic viability and sustainability metrics of emerging F-to-H2 technologies, combining bioprocesses with thermal gasification or combined cycles [126]. At the web site of IEA Bioenergy, a detailed report is available on gasification and subsequent H2 separation technologies by converting biomass including food residues and achieving high gas purity suitable for FCs [127]. Moreover, studies on thermophilic acidogenesis for H2 production from food waste underline that operational conditions like pH, retention time and organic loading rate critically impact hydrogen yields [128].

6. Future Research Directions

Future research on green hydrogen in agri-food systems should focus on addressing the technical, economic, and infrastructural barriers that currently limit large-scale deployment. In the context of agricultural machinery, hydrogen-based propulsion via fuel cells remains constrained by powertrain costs, onboard hydrogen storage requirements, fuel-cell durability, cooling demands, and the limited availability of refuelling infrastructure. As a result, hydrogen is unlikely to represent a competitive near-term solution for most agricultural vehicles, particularly when compared with battery-electric alternatives that currently offer higher efficiency and lower operating costs. More promising research opportunities may arise in heavy-duty transport and industrial applications, although the lack of widespread hydrogen infrastructure continues to restrict market development in the short term. Beyond mobility, significant potential exists in the chemical and energy sectors, particularly through the integration of hydrogen into biogas plants, where processes such as methanation via the Sabatier reaction can convert CO2 into synthetic methane suitable for injection into gas grids or direct energy use [129].

Additional research is warranted on hydrogen-based production of methanol and ammonia, which offer advantages in storage, transport, and compatibility with existing industrial systems. Methanol can serve both as a hydrogen carrier and as a fuel, while green ammonia synthesized from renewable hydrogen represents a strategic opportunity for reducing the carbon intensity of fertilizer production and enhancing regional supply security [130,131,132,133,134]. Across all these application domains, future studies should emphasize field-scale validation, dynamic system modelling, and integrated techno-economic and life-cycle assessments that reflect the specific operational conditions of agri-food systems. Such efforts will be essential to clarify realistic deployment pathways and to inform policy and investment decisions.

7. Conclusions

This review has examined the potential roles of hydrogen technologies across agri-food systems, highlighting both application-specific opportunities and significant constraints. The analysis indicates that hydrogen should not be regarded as a universal solution for the sector, but rather as a context-dependent and complementary option whose relevance varies strongly with technology readiness, scale, and integration potential.

From the perspective of hydrogen production, pathways relevant to agri-food systems can be broadly distinguished by their level of technological maturity. Commercial or near-term options (TRL ~8–9) include water electrolysis powered by renewable electricity (e.g., photovoltaic or wind systems) and hydrogen production from biomass or biogas reforming, which can leverage existing agricultural residues and infrastructure. These routes are already technically feasible and represent the most realistic contributors to near-term decarbonisation, provided that low-carbon electricity and sustainable biomass supplies are available.

Emerging and pilot-scale options (TRL ~4–6) include bio-electrochemical systems such as microbial electrolysis cells and electro-reforming of biomass-derived substrates from wastewater, manure, or food processing residues. While these approaches offer promising perspectives for circular resource use and integration with waste management, they remain constrained by limited operational experience, scale-up challenges, and uncertain techno-economic performance.

By contrast, long-term and exploratory concepts (TRL ≤ 3)—such as direct solar-to-hydrogen conversion via photosynthetic or hydrogenase-based biological processes—remain largely confined to laboratory research. Although scientifically interesting, these pathways are highly speculative in the context of agri-food energy systems and are unlikely to contribute meaningfully in the foreseeable future.

Regarding end-use applications, the review identifies the most concrete near-term opportunities for hydrogen in fertilizer production and selected food-industry processes, where replacing fossil-derived hydrogen with low-carbon or renewable hydrogen in established industrial routes (e.g., ammonia synthesis, hydrogenation, and controlled-atmosphere processing) can substantially reduce GHG emissions. In contrast, the widespread adoption of hydrogen in agricultural machinery and off-road vehicles faces major barriers related to storage volume, system cost, refuelling infrastructure, and competition from battery-electric solutions, making large-scale deployment unlikely in the short to medium term.

In controlled-environment agriculture, including greenhouses and hydroponic systems, H2-based energy storage and conversion concepts may support the integration of variable renewable electricity, particularly when waste heat and by-products such as oxygen can be valorised. However, most reported implementations remain at pilot or demonstration scale and require further validation under real operating conditions.

Overall, the findings of this review suggest that hydrogen can contribute to the decarbonisation of agri-food systems in targeted and differentiated ways, rather than through broad, sector-wide substitution of existing energy carriers. Future research should prioritize field-scale demonstrations, technology-specific life-cycle and techno-economic assessments, and policy frameworks adapted to decentralized and rural contexts, in order to clarify where hydrogen can deliver the greatest environmental and systemic benefits within agri-food systems.

Building on these findings, future research should prioritize field-scale demonstrations of hydrogen technologies in agricultural and food-industry contexts, alongside robust techno-economic and life-cycle assessments that account for decentralized operation, seasonal demand, and local resource availability. In parallel, the development of policy frameworks and standards tailored to rural and agri-food systems will be essential to support viable deployment pathways. These forward-looking research needs have been previously discussed in greater detail in Section 6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A. and P.C.; methodology, F.G., G.T. and B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G., R.A., G.T., B.B. and P.C.; writing—review and editing, F.G., P.C., G.T. and B.B.; supervision, R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FPT Industrial IVECO GROUP (Turin, Italy), represented by Eng. Andrea Gerini, and Eng. Giuliano Vercelli, for the information provided on hydrogen-powered engine technologies. We also extend our gratitude to Erwin Mayr, for the information shared regarding the use of hydrogen in the Trentino-Alto Adige region.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| AEM | Anion Exchange Membrane |

| AWE | Alkaline Water Electrolysis |

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| BGP | Bio Gas Plant |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CNG | Compressed Natural Gas |

| DIS | Direct Injection System |

| FC | Fuel Cell |

| FCV | Fuel Cell Vehicle |

| F-to-H2 | Food-to-Hydrogen |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GH2 | Green Hydrogen |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| HER | Hydrogen Evolution Reaction |

| H2PFI | Hydrogen Port Fuel Injection |

| HRW | Hydrogen-Rich Water |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| LNG | Liquid Natural Gas |

| MAP | Modified Atmosphere Packaging |

| MEC | Microbial Electrolysis Cell |

| NRMM | Non-Road Mobile Machinery |

| OER | Oxygen Evolution Reaction |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PWT | Power Train |

| RAP | Reducing Atmosphere Packaging |

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| SOE | Solid Oxide Electrolysis |

| TtW | Tank-to-Wheel |

References

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agrifood Systems. Global, Regional and Country Trends, 2000–2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/statistics/highlights-archive/highlights-detail/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-agrifood-systems.-global--regional-and-country-trends--2000-2022/en?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Alwazeer, D.; Hancock, J.T.; Russell, G.; Stratakos, A.C.; Li, L.; Çiğdem, A.; Engin, T.; LeBaron, T.W. Molecular hydrogen: A sustainable strategy for agricultural and food production challenges. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1448148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganza, A.; Gabetti, A.; Pastorino, P.; Zanoli, A.; Sicuro, B.; Barcelò, D.; Cesarani, A.; Dondo, A.; Prearo, M.; Esposito, G. Toward Sustainability: An Overview of the Use of Green Hydrogen in the Agriculture and Livestock Sector. Animals 2023, 13, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuiller, W. Biodiversity: Climate change and the ecologist. Nature 2007, 448, 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, T.; Von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 2013, 341, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Colglazier, W. Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science 2015, 349, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Potrč, S.; Čuček, L.; Martin, M.; Kravanja, Z. Sustainable renewable energy supply networks optimization—The gradual transition to a renewable energy system within the European Union by 2050. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.; Buratini, J. Global challenges for the 21st century: The role and strategy of the agri-food sector. Anim. Reprod. 2016, 13, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.W.R.; Blanchard, J.L.; Gardner, C.; Green, B.S.; Hartmann, K.; Tyedmers, P.H.; Watson, R.A. Fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions of world fisheries. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Domingo, N.G.G.; Colgan, K.; Thakrar, S.K.; Tilman, D.; Lynch, J.; Azevedo, I.L.; Hill, J.D. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2 °C climate change targets. Science 2020, 370, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sid, S.; Mor, R.S.; Panghal, A.; Kumar, D.; Gahlawat, V.K. Agri-food supply chain and disruptions due to COVID-19: Effects and Strategies. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, S.K.; Uddin, M.M.; Rahman, R.; Islam, S.M.R.; Khan, M.S. A review on mechanisms and commercial aspects of food preservation and processing. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.L.V.; Gray, E.M.A. Optimization and integration of hybrid renewable energy hydrogen fuel cell energy systems—A critical review. Appl. Energy 2017, 202, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelico, R.; Giametta, F.; Bianchi, B.; Catalano, P. Green Hydrogen for Energy Transition: A Critical Perspective. Energies 2025, 18, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroquino, J.; Bernal-Agustín, J.L.; Dufo-López, R. Standalone Renewable Energy and Hydrogen in an Agricultural Context: A Demonstrative Case. Sustainability 2019, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Misra, D.; Ghosh, S. Modeling and analysis of solar photovoltaic-electrolyzer-fuel cell hybrid power system integrated with a floriculture greenhouse. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 2036–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascuzzi, S.; Anifantis, A.S.; Blanco, I.; Mugnozza, G.S. Electrolyzer Performance Analysis of an Integrated Hydrogen Power System for Greenhouse Heating. A Case Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small Indoor Hydroponic System with Renewable Energy. IEEE Conference Publication. IEEE Xplore. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8571543 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Swaminathan, G.; Saurav, G. Development of Sustainable Hydroponics Technique for Urban Agrobusiness. Evergreen 2022, 9, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoin, C.; Balsari, P.; Cerruto, E.; Pascuzzi, S.; Raffaelli, M. Improvement in pesticide application on greenhouse crops: Results of a survey about greenhouse structures in Italy. Acta Hortic. 2008, 801, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation-2016/1628-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/1628/oj/eng (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Global Hydrogen Review 2024–Analysis-IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, M.P.; Longo, S.; Cellura, M.; Miccichè, G.; Ferraro, M. Critical Review of Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen Production Pathways. Environments 2024, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Fiori, L. Thermochemical and biological routes for biohydrogen production: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 23, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phogat, P.; Chand, B.; Shreya. Hydrogen economy: Pathways, production methods, and applications for a sustainable energy future. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 45, e01550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Akash, F.A.; Shovon, S.M.; Monir, M.U.; Ahmed, M.T.; Khan, M.F.H.; Sarkar, S.M.; Islam, K.; Hasan, M.; Vo, D.-V.N.; et al. Grey, blue, and green hydrogen: A comprehensive review of production methods and prospects for zero-emission energy. Int. J. Green Energy 2024, 21, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.; Rajendran, S.; Khusnun, N.; Bahari, M.; Johari, A.; Kamaruddin, M.; Ismail, M. Recent review and evaluation of green hydrogen production via water electrolysis for a sustainable and clean energy society. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Beswick, R.R.; Yan, Y. A green hydrogen economy for a renewable energy society. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 33, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Koo, M.; Woo, J.R.; Hong, B.I.; Shin, J. Economic valuation of green hydrogen charging compared to gray hydrogen charging: The case of South Korea. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 14393–14403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Hydrogen Review 2022–Analysis-IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2022 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Abdel-Motagali, A.; Al Bacha, S.; El Rouby, W.M.A.; Bigarré, J.; Millet, P. Evaluating the performance of hybrid proton exchange membrane for PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xing, F.; He, J. Rated Power Performance Optimization and Efficiency Enhancement Strategies for 60 kW Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Systems. Fuel Cells 2025, 25, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, A.; Haider, Z.; Farooq, U.; Shafique, S.; Karim, S.; Xu, H.; Ahmed, S. Advancements in acidic OER and HER electrocatalysts: Iridium, MOF-based, and ruthenium systems for sustainable hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 152, 150188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminaho, E.N.; Aminaho, N.S.; Aminaho, F. Techno-economic assessments of electrolyzers for hydrogen production. Appl. Energy 2025, 399, 126515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Alstad, V.; Jäschke, J. Design considerations for industrial water electrolyzer plants. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 37120–37136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Uchino, Y.; Ohno, J.; Suzuki, K.; Kim, S. Development and Demonstration of Large-scale Alkaline Water Electrolysis System ‘Aqualyzer’. Electrochemistry 2025, 93, 117007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Hydrogen: A Guide to Policy Making. Available online: https://www.irena.org/publications/2020/Nov/Green-hydrogen (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Global Hydrogen Review 2021–Analysis-IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2021 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Kumar, S.S.; Himabindu, V. Hydrogen production by PEM water electrolysis—A review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2019, 2, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsad, S.; Arsad, A.; Ker, P.J.; Hannan, M.; Tang, S.G.; Goh, S.; Mahlia, T. Recent advancement in water electrolysis for hydrogen production: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis and technology updates. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 60, 780–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.R.; Stansberry, J.M.; Mukundan, R.; Chang, H.-M.J.; Kulkarni, D.; Park, A.M.; Plymill, A.B.; Firas, N.M.; Liu, C.P.; Lang, J.T.; et al. Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Water Electrolysis: Cell-Level Considerations for Gigawatt-Scale Deployment. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 1257–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Passaro, R.; Ulgiati, S. Is Green Hydrogen an Environmentally and Socially Sound Solution for Decarbonizing Energy Systems Within a Circular Economy Transition? Energies 2025, 18, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoulaki, G.; Kougias, I.; Taylor, N.; Dolci, F.; Moya, J.; Jäger-Waldau, A. Green hydrogen in Europe—A regional assessment: Substituting existing production with electrolysis powered by renewables. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 228, 113649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpino, F.; Canale, C.; Cortellessa, G.; Dell’iSola, M.; Ficco, G.; Grossi, G.; Moretti, L. Green hydrogen for energy storage and natural gas system decarbonization: An Italian case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.K.; Hassan, Q.; Tabar, V.S.; Tohidi, S.; Jaszczur, M.; Abdulrahman, I.S.; Salman, H.M. Techno-economic analysis for clean hydrogen production using solar energy under varied climate conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 2929–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, S.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Meenakshisundaram, A.; Ferron, P.; Oni, B.A. Economic, social, and regulatory challenges of green hydrogen production and utilization in the US: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, H.; Yamashita, T.; Ogino, A.; Ishida, M.; Tanaka, Y. Hydrogen Fermentation of Cow Manure Mixed with Food Waste. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. JARQ 2010, 44, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, L.; McDonagh, S.; Weinrich, S.; Nilsson, D.; Hansson, P.A.; Nordberg, Å. Techno-Economic Assessment of Demand-Driven Small-Scale Green Hydrogen Production for Low Carbon Agriculture in Sweden. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 595224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lu, D.; Wang, J.; Tu, W.; Wu, D.; Koh, S.W.; Gao, P.; Xu, Z.J.; Deng, S.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Raw biomass electroreforming coupled to green hydrogen generation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.I.; Lee, L.Q.; Li, H.; Lai, Z.I.; Lee, L.Q.; Li, H. Electroreforming of Biomass for Value-Added Products. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Q.; Zhao, H.; Lim, T.Y.; Junyu, G.; Ding, O.L.; Liu, W.; Li, H. Green hydrogen generation assisted by electroreforming of raw sugarcane bagasse waste. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 7707–7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, J.G.F.; Oliveira, E.M.; Springer, M.V.; Cabral, H.L.; Barbeito, D.F.D.C.; Souza, A.P.G.; Moura, D.A.d.S.; Delgado, A.R.S. Hydrogen production from swine manure biogas via steam reforming of methane (SRM) and water gas shift (WGS): A ecological, technical, and economic analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8961–8971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Q.H.H.; Phan, T.P.; Nguyen, P.K.T. Recent advances in powering microbial electrolysis cells for sustainable hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 147, 150034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadier, A.; Simayi, Y.; Abdeshahian, P.; Azman, N.F.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Kalil, M.S. A comprehensive review of microbial electrolysis cells (MEC) reactor designs and configurations for sustainable hydrogen gas production. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Mohamed, H.O.; Park, S.-G.; Obaid, M.; Al-Qaradawi, S.Y.; Castaño, P.; Chon, K.; Chae, K.-J. A review on self-sustainable microbial electrolysis cells for electro-biohydrogen production via coupling with carbon-neutral renewable energy technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, A.A.; Ahmad, A. (Eds.) Microbial Electrolysis Cell Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, T.; Jemni, A. Green hydrogen production: A review of technologies, challenges, and hybrid system optimization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 225, 116194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Hunger, R.; Berrettoni, S.; Sprecher, B.; Wang, B. A review of hydrogen storage and transport technologies. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antweiler, W.; Schlund, D. The emerging international trade in hydrogen: Environmental policies, innovation, and trade dynamics. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2024, 127, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, S.S.; Twinkle, A.R.; Sasi, B.S.A.; Reshma, R. Emerging paradigms in renewable hydrogen production: Technology, challenges, and global impact. Next Energy 2025, 8, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Stanway, C.; Becerra, V.; Prabhu, S. Techno-economic analysis with electrolyser degradation modelling in green hydrogen production scenarios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 106, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, M.; Portarapillo, M.; Di Nardo, A.; Venezia, V.; Turco, M.; Luciani, G.; Di Benedetto, A. Hydrogen Safety Challenges: A Comprehensive Review on Production, Storage, Transport, Utilization, and CFD-Based Consequence and Risk Assessment. Energies 2024, 17, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzmann, D.; Heinrichs, H.; Lippkau, F.; Addanki, T.; Winkler, C.; Buchenberg, P.; Hamacher, T.; Blesl, M.; Linßen, J.; Stolten, D. Green hydrogen cost-potentials for global trade. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33062–33076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdem, M.S.; Mazzeo, D.; Matera, N.; Baglivo, C.; Khan, N.; Afnan; Congedo, P.M.; De Giorgi, M.G. A brief overview of solar and wind-based green hydrogen production systems: Trends and standardization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, H.; Naghizadeh, R.A. Multi-criteria optimal sizing of hybrid renewable energy systems including wind, photovoltaic, battery, and hydrogen storage with ɛ-constraint method. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2018, 12, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scamman, D.; Bustamante, H.; Hallett, S.; Newborough, M. Off-grid solar-hydrogen generation by passive electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 19855–19868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareiß, K.; de la Rua, C.; Möckl, M.; Hamacher, T. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen from proton exchange membrane water electrolysis in future energy systems. Appl. Energy 2019, 237, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaban, S.; Bozalakov, D.; Vandevelde, L. Development of a dynamic mathematical model of PEM electrolyser for integration into large-scale power systems. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 23, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arough, P.B.; Moranda, A.; Niyati, A.; Paladino, O. Parametric Sensitivity of a PEM Electrolyzer Mathematical Model: Experimental Validation on a Single-Cell Test Bench. Energies 2025, 18, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exploring the Potential of Hydrogen in Agriculture: Farming with a Green Future. Available online: https://extension.psu.edu/exploring-the-potential-of-hydrogen-in-agriculture-farming-with-a-green-future (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Nagaj, R.; Gajdzik, B.; Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W.W. The Impact of Deep Decarbonization Policy on the Level of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the European Union. Energies 2024, 17, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikiru, S.; Adedayo, H.B.; Olutoki, J.O.; Rehman, Z.U. Hydrogen integration in power grids, infrastructure demands and techno-economic assessment: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 104, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Raimondi, P.P.; Scita, R.; Hafner, M. The Role of Green and Blue Hydrogen in the Energy Transition—A Technological and Geopolitical Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megia, P.J.; Vizcaino, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Hydrogen Production Technologies: From Fossil Fuels toward Renewable Sources. A Mini Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 16403–16415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R. Green hydrogen production potential in West Africa–Case of Niger. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togun, H.; Basem, A.; Abdulrazzaq, T.; Biswas, N.; Abed, A.M.; Dhabab, J.M.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Slimi, K.; Paul, D.; Barmavatu, P.; et al. Development and comparative analysis between battery electric vehicles (BEV) and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEV). Appl. Energy 2025, 388, 125726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Helmolt, R.; Eberle, U. Fuel cell vehicles: Status 2007. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänggi, S.; Elbert, P.; Bütler, T.; Cabalzar, U.; Teske, S.; Bach, C.; Onder, C. A review of synthetic fuels for passenger vehicles. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret, S. Toyota and Kenworth unveil fuel cell heavy truck at Port of LA. Fuel Cells Bull. 2019, 2019, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, Y.; Hosseini, S.E.; Butler, B.; Alzhahrani, H.; Senior, B.T.F.; Ashuri, T.; Krohn, J. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles; Current Status and Future Prospect. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshekarzadeh, T.; Akbari, S.; Sharifian, M.; Mirshekarzadeh, A.; Salehi, F.; Bijarchi, M.A. Physical solutions for hydrogen storage: Technological challenges, safety assessments, and environmental aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 230, 116627–116660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.M.; Steeper, R.R.; Lutz, A.E. The hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engine: A technical review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S. Recent progress in the use of hydrogen as a fuel for internal combustion engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfert, F. Mazda: Hydrogen RE with Dual-Fuel System (Sustainable Zoom-Zoom). January 2008. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/64476099/Mazda_Hydrogen_RE_with_Dual_Fuel_System_Sustainable_Zoom_Zoom_ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Ozcanli, M.; Bas, O.; Akar, M.A.; Yildizhan, S.; Serin, H. Recent studies on hydrogen usage in Wankel SI engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 18037–18045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.W.G. Future technological directions for hydrogen internal combustion engines in transport applications. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 21, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenna, M.; Foiadelli, F.; Leone, C.; Longo, M.; Zaninelli, D. Feasibility Proposal for Heavy Duty Farm Tractor. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference of Electrical and Electronic Technologies for Automotive, AUTOMOTIVE 2018, Milan, Italy, 9–11 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagnelöv, O.; Larsson, G.; Larsolle, A.; Hansson, P.A. Life cycle assessment of autonomous electric field tractors in Swedish agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, L.M. Hydrogen engines: A view of the past and a look into the future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1990, 15, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschka, W. Hydrogen: The future cryofuel in internal combustion engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1998, 23, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichlseder, H.; Wallner, T.; Freymann, R.; Ringler, J. The Potential of Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engines in a Future Mobility Scenario; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Sierens, R.; Verstraeten, S. A Critical Review of Experimental Research on Hydrogen Fueled SI Engines; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Wallner, T. Hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 490–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, H.L.; Srna, A.; Yuen, A.C.Y.; Kook, S.; Medwell, P.R.; Yeoh, G.H.; Medwell, P.R.; Chan, Q.N. A Review of Hydrogen Direct Injection for Internal Combustion Engines: Towards Carbon-Free Combustion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuranc, A.; Dudziak, A.; Słowik, T. Low-Carbon Hydrogen Production and Use on Farms: European and Global Perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Gao, C.; Fang, P.; Lin, G.; Shen, W. Alleviation of cadmium toxicity in Medicago sativa by hydrogen-rich water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cheng, D.; Wang, R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Shen, W. Endogenous hydrogen gas delays petal senescence and extends the vase life of lisianthus cut flowers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 147, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Shorna, M.N.A.; Islam, S.; Biswas, S.; Biswas, J.; Islam, S.; Dutta, A.K.; Uddin, S.; Zaman, S.; Ekram, A.E.; et al. Hydrogen-rich water: A key player in boosting wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedling growth and drought resilience. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Batool, S.; Khalid, N.; Ali, S.; Raza, M.A.; Li, X.; Li, F.; Xinhua, Z. Recent trends in hydrogen-associated treatments for maintaining the postharvest quality of fresh and fresh-cut fruits and vegetables: A review. Food Control 2024, 156, 110114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, T.; Ren, Y.; Yang, H.; Ding, W.; et al. Regulation of hydrogen rich water on strawberry seedlings and root endophytic bacteria under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1497362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugazhendhi, A.; Bharathi, D.; Aljohani, B.S.; Aljohani, K.; Kamarudin, S.; Sekar, M.; Shanmuganathan, R. Sustainable ammonia production, storage, and transport technologies for clean energy applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 194, 152504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Elgowainy, A.; Wang, M. Life cycle energy use and greenhouse gas emissions of ammonia production from renewable resources and industrial by-products. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 5751–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Liu, X.; Vyawahare, P.; Sun, P.; Elgowainy, A.; Wang, M. Techno-economic performances and life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of various ammonia production pathways including conventional, carbon-capturing, nuclear-powered, and renewable production. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 4830–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, D.; Rosa, L.; Gabrielli, P.; Parente, A.; Contino, F. Cost-competitive decentralized ammonia fertilizer production can increase food security. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, R.; Hong, J.; Gao, Y.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, R.; Ostrikov, K.; et al. Sustainable ammonia production via nanosecond-pulsed plasma oxidation and electrocatalytic reduction. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 342, 123426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Ansar, R.; Jahan, Z.; Javaid, F.; Ahmad, R.; Anjum, H.; Ibrahim, M.; Bokhari, A. Thermochemical conversion of agricultural waste to hydrogen, methane, and biofuels: A review. Fuel 2023, 351, 128947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, N. Environmental and economic evaluations of centralized biogas plants running on cow manure in Hokkaido, Japan. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 49, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveraging Local Hokkaido Resources in a Dairy-Farming Town: The Hydrogen Supply Chain Efforts of ‘Shikaoi Hydrogen Farm’. TSH Stories. 【公式】Team Sapporo-Hokkaido|北海道の GX. Available online: https://tsh-gx.jp/en/stories/shikaoi/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Green Hydrogen and Platform Chemicals from Agricultural Residues (AGRI-WASTE2H2). NordForsk. Available online: https://www.nordforsk.org/projects/green-hydrogen-and-platform-chemicals-agricultural-residues-agri-waste2h2-0 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Karim, S.M.R. Production of green hydrogen from farm and food wastes: A project for generation of low-cost renewable energy and eco-friendliness. In Proceedings of the 3rd Edition of Global Conference on Agriculture and Horticulture, Valencia, Spain, 11–13 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Puteri, M.N.; Gew, L.T.; Ong, H.C.; Ming, L.C. Biomass-to-biohydrogen conversion: Comprehensive analysis of processes, environmental, and economic implications. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 200, 107943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyaperumal, G.; Nagabhooshanam, N.; Rathore, S.; Kulshreshta, A.; Sheela, C.S.; Beulah, D.; Maranan, R.; Srinivasan, R.; Sathiyamurthy, S. Converging pathways in biomass-to-biohydrogen conversion: A review on hybrid systems, nanotechnological interventions, and sustainable integration frameworks. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2025, e70295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, U.; Mondol, M.S.A.; Abdi, G.; Dash, K.K.; Khan, S.A.; Dar, A.H. Hydrogen assisted technologies in food processing, preservation and safety: A comprehensive review. Food Control 2025, 178, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanti, I.; Wongsawaeng, D.; Kongprawes, G.; Ngaosuwan, K.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Hosemann, P.; Sola, P.; Assabumrungrat, S. Enhanced cold plasma hydrogenation with glycerol as hydrogen source for production of trans-fat-free margarine. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiekermann, M.L.; Seidensticker, T. Catalytic processes for the selective hydrogenation of fats and oils: Reevaluating a mature technology for feedstock diversification. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 4390–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, C.; Lin, W.; Li, L.; Shen, W. Hydrogen-based modified atmosphere packaging delays the deterioration of dried shrimp (Fenneropenaeus chinensis) during accelerated storage. Food Control 2023, 152, 109897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwazeer, D.; Özkan, N. Incorporation of hydrogen into the packaging atmosphere protects the nutritional, textural and sensorial freshness notes of strawberries and extends shelf life. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyekum, E.B.; Al-Maaitah, M.I.; Kumar, P.; Odoi-Yorke, F.; Rashid, F.L. Progress of hydrogen production from food waste—A systematic, content, and bibliometric review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Wasima, F.; Shawon, M.S.I.K.; Mourshed, M.; Das, B.K. Valorization of food waste into hydrogen energy through supercritical water gasification: Generation potential and techno-econo-environmental feasibility assessment. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seglah, P.A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Neglo, K.A.W.; Zhou, K.; Sun, N.; Shao, J.; Xie, J.; Bi, Y.; Gao, C. Utilization of food waste for hydrogen-based power generation: Evidence from four cities in Ghana. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Yuzer, B.; Bicer, Y.; McKay, G.; Al-Ansari, T. Hydrogen gas and biochar production from kitchen food waste through dark fermentation and pyrolysis. Front. Chem. Eng. 2024, 6, 1450151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.K.; Shelare, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, D.; Patane, P.M.; Wagle, C.S.; Awale, S.D. Techno-economic analysis and sustainable advancements in food waste conversion to biogas and hydrogen fuel. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2025, 44, e14606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomass Gasification for Hydrogen Production–Bioenergy. Available online: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/blog/publications/biomass-gasification-for-hydrogen-production/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Shin, H.S.; Youn, J.H. Conversion of food waste into hydrogen by thermophilic acidogenesis. Biodegradation 2005, 16, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birbara, P.J.; Sribnik, F. Development of an Improved Sabatier Reactor; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 79-ENAS-36. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A.H.M.; Cheralathan, K.K.; Porpatham, E.; Arumugam, S.K. Hydrogen generation using methanol steam reforming–catalysts, reactors, and thermo-chemical recuperation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Yamada, T. Methanol Reforming for Hydrogen Production: Advances in Catalysts, Nanomaterials, Reactor Design, and Fuel Cell Integration. ACS Eng. Au 2025, 5, 314–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkou, E.; Wang, H.; Manos, G.; Constantinou, A.; Tang, J. Advances in Catalyst and Reactor Design for Methanol Steam Reforming and PEMFC Applications. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 3810–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaroli, N.; Balzani, V. The hydrogen issue. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaroli, N.; Balzani, V. Towards an electricity-powered world. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3193–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.