Abstract

The Mediterranean Sea is recognized for its high biodiversity but is also a hotspot for pollution. In this study, fish samples of four native marine species were collected from wild catches to determine contaminants such as Anisakis parasites and heavy metals, including nickel, lead, copper, zinc, and chromium, within local marine fish species. The detection of Anisakis parasites was performed by a visual inspection and a digestion method. Metal analysis was carried out on skin, muscle, viscera, and bones of fish, using Microwave Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectroscopy. This study demonstrated that Boops boops was the least infested species by Anisakis parasite, while Scomber colias was the most infested, with Sardinella aurita and Trachurus trachurus showing a lower infestation rate. Pearson correlation statistics revealed that infestation correlated with fish size but not with maturity or sex. Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated that the carnivorous species were more prone to Anisakis infestation than the omnivorous species. The maximum levels of copper, nickel, chromium, lead, and zinc content in fish tissues were 13.2 ± 0.11, 19.5 ± 0.02, 19.9 ± 0.01, 28.8 ± 0.09, and 184.87 ± 0.63 µg/g, respectively. PCA revealed that heavy metal contamination does not discriminate between fish species and sex, as opposed to tissue type and location of catch. Some metals, such as zinc and lead, seem to accumulate more in muscle rather than the other tissues. These findings indicate that Anisakis infestation and heavy metal analysis should be monitored and extended beyond the current EU requirements.

1. Introduction

The Mediterranean Sea is widely recognized as a global hotspot of marine biodiversity, serving as a critical habitat for numerous endemic and commercially important fish species [1]. This area of sea, also known as the sea “between the lands,” contains 4–18% of global marine fish species with a high percentage of endemism, which amounts to 650 species and subspecies [2]. Malta, an island located in the middle of the Mediterranean, is found within the intermediate latitudinal gradient position between the shores of the European Mediterranean and the coast of North Africa and is distinguished by its warm climate and the clearest sea water in the Mediterranean. Furthermore, the various habitats of marine species characterize the surrounding waters of the Maltese islands with its richness and diversity of this marine fauna. There are 412 confirmed fish species in Maltese waters [3]. During 2021, 36.212 tonnes of Boops boops, 36.457 tonnes of Sardinella aurita, 586.614 tonnes of Somber colias, and 27.296 tonnes of Trachurus trachurus were caught [4].

Fish are an essential part of the diet for many people around the world. They are a source of high-quality protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins D and B12, and essential minerals like iodine and selenium [5]. These nutrients are crucial for various bodily functions, including brain development, cardiovascular health, and the immune system. Fish also provide a source of high-quality protein, which is necessary for muscle growth and repair, as well as the production of enzymes and hormones. The regular consumption of fish has been associated with numerous health benefits, such as a lower incidence of heart disease, better cognitive function, and reduced symptoms of depression [6,7].

Despite the numerous health benefits, fish can also be a source of harmful contaminants. Parasites and heavy metals are two major concerns [8]. Anisakis is a genus of parasitic nematodes that can infect marine fish and pose a significant health risk to humans. Anisakis parasites have a complex life cycle involving marine mammals, crustaceans, and fish. Humans can become accidental hosts by consuming raw or undercooked fish containing the larvae of these parasites. The larvae may cause anisakiasis, a condition characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The larvae can also penetrate the intestinal wall, leading to more severe complications that may require surgical intervention. Additionally, Anisakis can cause allergic reactions, ranging from mild symptoms like hives to severe anaphylactic reactions [9,10]. On the other hand, heavy metals can enter aquatic ecosystems through industrial pollution, agricultural runoff, and natural geological processes [11]. These metals can accumulate in the tissues of fish, posing risks to human health when consumed. Several heavy metals have been reported as toxic to humans [12,13]. Nickel (Ni) and lead (Pb) are also concerning due to their toxicity [14,15]. Ni can cause respiratory problems, allergic reactions, and, in high doses, kidney and cardiovascular damage [16]. Pb exposure can result in neurological and developmental issues, especially in children, and can also cause cardiovascular and renal problems in adults [17]. Copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), while essential nutrients, can be toxic at high concentrations [18]. Excessive Cu intake can lead to liver and kidney damage [19], while high levels of Zn can cause nausea, vomiting, and immune dysfunction [20]. Chromium (Cr) is found in two forms: trivalent chromium (Cr III), which is an essential nutrient, and hexavalent chromium (Cr VI), which is highly toxic and carcinogenic [21]. Industrial pollution is a significant source of Cr VI in aquatic environments.

Codex Alimentarius (CAC/RCP 52-2003) provides an international standard that regulates Anisakis parasite infestations in fish [22]. It is recommended that fish from wild catches are freeze-treated to eliminate the parasites, and a focus on Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) systems is advised to prevent parasitic infestations. Within the European Union, Regulation (EC) No. 853/2004 obliges operators to visually inspect fishery products for visible parasites and to freeze fish intended to be consumed raw or undercooked [23]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) issued a scientific opinion stating that risk assessment should emphasize regular monitoring, especially in wild-caught fish [24]. In its statement, the EFSA mentions that farmed fish have a negligible risk if fed parasite-free feed and grown in controlled environments. The regulation of heavy metal contamination is more limited, though it sets provisional tolerable weekly intakes for metals like mercury (1.6 µg/kg bw/week for MeHg) [25]. The World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) sets a limit of 1.826 µg/person/day for mercury intake. The Codex Alimentarius (Codex STAN 193-1995) includes maximum levels for metals in fish [26]. The EU, in its Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006, sets levels for mercury, lead, cadmium, and inorganic arsenic as 0.5–1.0 (depending on fish species), 0.3, 0.05–0.1, and 0.1, mg/kg in fish, respectively [27].

There are several claims that wild fish may harbor and transmit Anisakis and heavy metals along the food chain. In this study, four fish species were considered, namely Boops boops (bogue) and Sardinella aurita (round sardinella), which are omnivorous species, and Scomber colias (Atlantic chub mackerel) and Trachurus trachurus (Atlantic horse mackerel), which are carnivorous species. The study therefore aims at detecting and analyzing these contaminants in these local fish species around Malta, emphasizing the importance of maintaining safe levels of these substances in marine food sources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procurement of Samples

A total of 25 batches, consisting of a total of 195 fish, were procured from the Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Hal Luqa, Malta). This study focused on four native species, namely Boops boops, Scomber colias, Sardinella aurita, and Trachurus trachurus. The fish type and number of fish samples from the 25 batches are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fish type and number of fish sampled by batch.

After collection, the fish samples were transported to the laboratory. All samples were labelled accordingly and then stored at a controlled temperature of 4 °C. Testing was initiated within 24 h of collection.

2.2. Digestion and Detection of Anisakis Larvae

The examination of larvae was conducted via an artificial digestion method, adhering to the guidelines established by the European Union Reference Laboratory for Parasites (EURLP) [28], in accordance with ISO 23036-2021 [29]. The method was applied as follows.

Whole fish were visually inspected and manually eviscerated, skinned, and filleted. Before analysis, samples were acclimatized to room temperature. Sample batches included muscle and viscera of fish. Each sample was gently eased apart by surgical forceps so as not to disrupt or damage any nematode larvae. These were weighed and recorded alongside the batch number. Minimum individual sample size for testing by digestion was at least 25 g but not more than 200 g. Muscle tissue was sampled from the abdominal region, where larvae are more likely to be present according to ISO 23036-2021 [29]. The digestion solution was prepared with pre-warmed distilled water, pepsin, and hydrochloric acid (Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany). Samples were transferred to individual beakers filled with the digestion solution. A sieve was used to visually observe any presence of Anisakidae larvae. The larvae were further examined with a stereomicroscope at 10× and 20× magnification for their morphological identification. Larvae were then transferred to vials containing 90% ethanol and stored at −20 °C [30].

2.3. Sample Preparation and Detection of Heavy Metals

From each batch of fish samples, the skin, muscle, viscera, and bones were also collected for heavy metal analysis. Ceramic crucibles (75 mL) were rinsed in a 5% HNO3 bath for 12 h and then rinsed with deionized water (Human Ultrapure system, Magdeburg, Germany). Approximately 1 g of each sample was weighed, transferred to a 15 mL centrifuge tube, and properly homogenized by gentle vortexing for 1 min in 5 mL 5% HNO3 solution. The homogenates were transferred to the crucibles, and a further 1 mL of the acid was used to rinse the tube. The samples were digested over a hot plate at 90 °C, until the liquid evaporated completely. The samples were then transferred to a muffle furnace (Wise Therm—Wisd laboratory instruments, Witeg Labortechnik GmbH, Wertheim, Germany) set at 500 °C for 4 h [31]. The ashes, thus obtained, were dissolved in 5 mL 5% HNO3 solution, filtered through Whatman filter papers in 50 mL volumetric flasks and made to volume with deionized water. These were then filtered through 0.45 µm filters and transferred to 50 mL centrifuge tubes ready for analysis.

The samples were then analyzed for five heavy metals using a Microwave Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometer (MP-AES 4100, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) via the Agilent MP-Expert Software, with conditions set as demonstrated in Table 2. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for each metal were determined using the statistical approach described by Armbruster and co-workers [32] as follows:

Table 2.

The settings and conditions for the Microwave Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometer.

Accuracy (%Recovery) was calculated from the found and standard concentrations using the following equation:

Precision (%RSD) was calculated as follows:

The conditions of the five metals are illustrated in Table 3. The concentration of metals was calculated using the following equation:

where SDblank is the standard deviation of the blank, Cstd is the true concentration of the calibration standard, Cfound is the measured concentration, calculated from the instrument signal (intensity) using the calibration curve, concmetal is the concentration of the metal in the final aqueous solution, and weighttissue is the weight of fish tissue.

Table 3.

The wavelength, correlation coefficient (R2), LOD, LOQ, accuracy, and precision of the metals under investigation.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The datasets obtained were analyzed with Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and XLSTAT (2004.2.2, Lumivero) software. GraphPad was used to determine any differences between samples using ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-hoc test, which were performed on fish characteristics (weight and length) and heavy metals. This was undertaken to determine any difference between batches, types of tissue, and fish species. XLSTAT was used to determine if there was a correlation between the two methods used for the determination of Anisakis parasites in the fish. The dataset for heavy metals was subjected to Spearman correlation and principal component analysis. This was conducted to determine any correlation or divergences between fish tissues, locations of catch, fish species, and sex. All tests were carried out in triplicate. A probability level of p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

For this study, each fish sample length, weight, sex, and maturity (Table 4) was recorded before visually inspecting internally the fish for any parasites. The distribution of sexes for the four species varied significantly. Sardinella aurita and Scomber colias predominated in female fish, whereas Trachurus trachurus was more inclined towards the male population. For Boops boops, apart from a similar equal distribution between males and females (13 and 17, respectively), the sex for a group of 15 Boops boops was not determined. The lengths of the fish species ranged between 145 and 355 mm, whereas the weights ranged over a span, between 20 g and 281.67 g.

Table 4.

Sex distribution, lengths, and weights of individual fish for the four species.

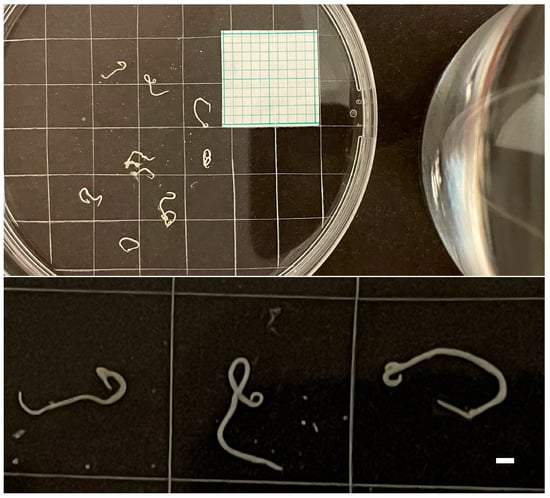

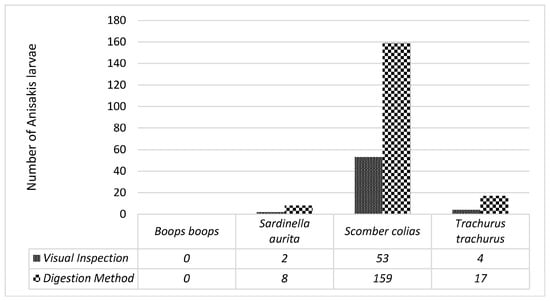

White coiled nematodes were detected in the fish samples (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the number of Anisakis larvae detected by the visual and digestion methods in the four fish species, showing that the digestion method provided a greater number of nematodes than simple visual examination. The Spearman correlation revealed that the findings of the two methods are significantly different from each other (p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Nematodes isolated from fish samples. The bar (bottom right) indicates 1 mm.

Figure 2.

The number of nematodes by fish species.

Table 5 shows the content of the five heavy metals in the four fish matrices: skin, muscle, bone, and internal organs. The Ni content in fish tissues ranged between 2.6 ± 0.10 µg/g and 19.5 ± 0.02 µg/g, Pb content ranged between 9.0 ± 0.05 µg/g and 28.8 ± 0.09 µg/g, Cu content ranged from undetectable quantities to 13.2 ± 0.11 µg/g, Zn content ranged from non-detectable quantities to 184.87 ± 0.63 µg/g, and Cr content ranged between 15.1 ± 0.01 µg/g and 19.9 ± 0.01 µg/g.

Table 5.

The concentration of heavy metals for the four matrices of the 25 batches.

4. Discussion

The distribution of sexes for the four species varied significantly from each other. Sardinella aurita and Scomber colias predominated in female fish, whereas Trachurus trachurus was more inclined towards the male population. Apart from a similar equal distribution between males and females (13 and 17, respectively), the sex for a group of 15 Boops boops was not determined.

The lengths of the fish species ranged between 145 and 355 mm. For Boops boops, the range was between 128 and 232 mm. This falls within the range quoted by Kara & Bayhan [33] (92–276 mm) but is on the lower end of the values quoted by Moutopoulos & Stergiou [34] (145–281 mm). The Sardinella aurita length range was between 185 and 290 mm in this present study. This range lies between the studies by Tsikliras and co-workers [35] (max. 248 mm), Tsikliras & Antonopoulou [36] (125–243 mm), and Dahel and co-workers [37] (80–255 mm), which are on the lower end, and the study by Moutopoulos & Stergiou [34] (232–290 mm), which is on the higher end. For Scomber colias, the length range was between 255 and 355 mm, which is similar to findings by Moutopoulos & Stergiou [34] (229–330 mm) and Velasco [38] (164–430 mm) but on the lower end according to studies by Martins [39] (540 mm) and Navarro and co-workers [40] (max. 650 mm). In the case of Trachurus trachurus, the length ranged between 145 and 275 mm, similar to that found by Moutopoulos & Stergiou [34] (158–280 mm) but on the higher end of the ranges quoted by Aydin & Karadurmuş [41] (69–190 mm) and Kalaycı and co-workers [42] (73–183 mm). There was a significant difference in the lengths for the Boops boops and Trachurus trachurus (p < 0.01), and these were significantly different from Sardinella aurita and Scomber colias (p < 0.001).

The weights of the fish species ranged over a wide range. In the case of Boops boops, the range was between 20 and 122 g, which falls within the range quoted by Kara & Bayhan [33] (7.18–281.67 g). For Sardinella aurita, the weight ranged between 47 and 179 g, which is superior to the range reported by Dahel and co-workers [37] (3.71–140.27 g). In the case of Scomber colias, it was between 131 and 411 g, which is considerably smaller when compared to the findings of Navarro and co-workers [40] with a maximum of 2900 g. For Trachurus trachurus, this ranged between 22 and 173 g, which is much higher than the ranges quoted by Aydin & Karadurmuş [41] (2.32–59.89 g) and Kalaycı and co-workers [42] (3.34–47.37 g). There was no significant difference in the weights for Boops boops and Trachurus trachurus, whereas these exhibited significantly different weights from Sardinella aurita and Scomber colias (p < 0.001).

Adverse reactions caused by the ingestion of seafood may range from mild urticarial to life-threatening anaphylactic reactions. EU Regulation (EC) No. 853/2004 requires fish operators (food business operators) to perform parasite checks such as visual inspections before the fish reaches consumers [23]. According to the Scientific Opinion on Risk Assessment of Parasites in Fishery Products issued by the EFSA [43], research shows that many food processing methods such as traditional marinating and cold smoking are not effective enough to kill Anisakis, stating that the most effective way is by applying heat and freeze treatments which should guarantee the killing of this parasite. This proves that all wild fish caught in seawater and freshwater should be considered a risk to human health and a state of concern, especially if fish products are eaten raw or nearly raw, as they have the possibility to contain parasites. Hence, control methods such as the use of the artificial digestion method to check fresh fish products for Anisakis parasites are important as there are medical and economic implications regarding public health and fish markets [44].

However, allergens caused by Anisakis may be triggered by this parasite, even after ingestion of well-cooked or heated fish [45]. Hence, certain Anisakis allergens have been found to be resistant to denaturation caused by cold or heat [46]. Nonetheless, when comparing high detection levels of Anisakis contamination in marine fish, cases of Anisakiasis are still uncommon and most infestation cases remain subclinical [46].

The Anisakis larvae were observed by direct visual checks and an artificial digestion method. Although the relationship between the methods shows a degree of linearity (rs = 0.919), the variances of the two datasets are different from each other (Levene’s test, p = 0.002). It can be concluded that although the visual method indicates firstly the presence or absence of Anisakis, and secondly a quantitative result for the number of Anisakis organisms, the digestion method is more precise in determining the total number of larvae in the fish muscle. The species most prone to Anisakis was found to be Scomber colias: the quantity detected by visual inspection amounted to 53 nematode larvae and by using the digestion method amounted to 159 parasites (44/45 specimens). Two other fish species were also found to be prone to Anisakis: Trachurus trachurus (42/45 specimens) and Sardinella aurita (12/60 specimens). On the other hand, no contamination of parasites was found in Boops boops (0/45 specimens). Analysis showed that Trachurus trachurus exhibited 4 parasites by visual inspection and 17 parasites by the digestion method. On the other hand, Sardinella aurita had 2 parasites by visual inspection and 8 parasites by the digestion method. The total amount of fish sampled and tested were 204 with 216 viable parasites detected, out of which 10 parasites were damaged. From previous studies regarding marketed marine fish in Egypt, 70% of Anisakis larvae were detected in herrings and 50% in sardine, and most of the parasites were found in the viscera of the two species; lower rates were detected in the muscles, with 30% in herrings and 10% in sardine [47]. In another study on European sea bass species (Dicentrarchus labrax) from Northeast Atlantic Ocean, the digestion method was used for analysis, where most of the larvae found were in the viscera, under the gastric and intestinal serosa, whilst only one parasite was detected in the dorsal fillet; the mean intensities were 93.39% in viscera and 1.94% in muscle [48].

Heavy metal contaminants are naturally found within the environment; however, their concentrations may increase through pollution and industrial activities. Heavy metal toxic components may severely harm the health of fish and their surrounding ecosystems [49]. Results from one study show that fish in polluted water accumulate heavy metals within the tissues, negatively affecting their growth development and adversely affecting the muscles and liver [50]. Studies show that the uptake and concentrations of metals found in fish may depend on environmental and biological factors according to fish species; also, they may rely on the chemical and physical status of a metal, accumulating in different rates and levels within different tissues found in fish [51]. Hence, this may create a threat to human health after the consumption of contaminated fish with toxic heavy metals, or there may be no economic value if the fish is too toxic for consumers [52,53,54]. Generally higher concentrations of heavy metals are more evident in the kidney, liver, and gills of fish than in the muscles and skin [55]. Five metals were analyzed in this study: chromium, copper, nickel, lead, and zinc.

Chromium is one of the most commonly found elements in aquatic environments and may occur in two valence states: trivalent chromium (Cr III) and hexavalent chromium (Cr VI). Exposure in the environment may happen due to industrial and natural sources. The amount of chromium concentration may depend on its form and medium, where hexavalent chromium is seen as the most toxic form, with carcinogenic and mutagenic properties that may cause harmful impacts to living organisms [56]. Chromium causes behavioral changes in fish, such as loss of appetite, irregular swimming, and increase in operculum [57]. In a study on Tilapia guineensis and Sarotherondon melanotheron found in the Bodo River, the Cr content ranged between 10.3 µg/g and 10.5 µg/g, using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry [58]. In this present study, the Cr content in fish tissues ranged between 15.1 ± 0.01 µg/g and 19.9 ± 0.01 µg/g. The chromium content was not significantly different in the different tissues. The muscle and bone exhibited values of 19.0 ± 0.09 and 19.0 ± 0.08 µg/g, respectively, while the internal organs and skin exhibited values of 18.0 ± 0.17 and 18.0 ± 0.14 µg/g, respectively. When compared to the Cr content reported on other fish, the levels in the study by Azmat and Javed [59] were significantly high in some internal organs, namely the fish liver (65.78 µg/g) and the kidney (54.95 µg/g). When considering fish species in this present study, the Cr content was not significantly different for the four species, with values ranging between 18.43 ± 0.15 µg/g for Scomber colias and 18.7 ± 0.11 µg/g for Boops boops. Regarding the maximum limit guidelines of FDA on hexavalent chromium in fish tissue, the limit is 12–13 µg/kg body weight [60]. In this present study, although the content does not seem significantly higher than this limit, and there was no distinction between the trivalent and the hexavalent Cr in the fish samples.

Generally, copper is found to be an essential element in fish, but in high concentrations it becomes toxic. The primary symptom in fish caused by toxic copper absorbed through the food chain is the production of free radicals that accumulate in tissues [50]. In a study by Olmedo and co-workers [54], the maximum Cu content in marine species was 4.736 µg/g, using an AAnalyst 800 atomic absorption spectrometer. It was reported that these results do not pose any risks to the average consumer as they did not exceed the toxicity reference values [54]. However, in this present study, the Cu content in fish tissues ranged from undetectable quantities to 13.2 ± 0.11 µg/g. The copper content was exceptionally high in internal organs (µ = 0.9 ± 0.30 µg/g), being not statistically different from Cu in skin samples (µ = 0.6 ± 0.10 µg/g) but significantly different from its content in muscle and bone (µ = 0.14 ± 0.02 and 0.09 ± 0.04 µg/g, respectively) (p < 0.01). When considering the fish species, the Cu content was significantly higher in Sardinella aurita (µ = 0.93 ± 0.24 µg/g) when compared to the content in Trachurus trachurus and Boops boops (µ = 0.15 ± 0.03 and 0.09 ± 0.04 µg/g, respectively, p < 0.01). However, the Cu level in Scomber colias was µ = 0.38 ± 0.07 µg/g, which is approximately half that quoted by Çelik and Oehlenschläger [61] in Scomber scombrus (0.84 µg/g).

Nickel is an important element required for all organisms, where deficiency in animals has been shown to cause slow growth development [62]. However, accumulation of Ni in aquatic organisms and their ecosystems may lead to fatal effects [63]. Ni may pass through the fish gills and skin, and would then accumulate within their internal organs [64]. In the human body, excess amounts of Ni may cause various pathological respiratory lung problems, weight loss, liver damage, heart problems, skin irritation, and mortality [65,66]. In this present study, the Ni content in fish tissues ranged between 2.6 ± 0.10 µg/g and 19.5 ± 0.02 µg/g. The nickel content in bone and skin was higher (11.0 ± 0.6 µg/g for both), though comparable and not statistically different from that in muscle and internal organs (10.0 ± 0.73 and 9.8 ± 0.63 µg/g, respectively). When considering the fish species, the Ni content was highest in Scomber colias (12.4 ± 0.65 µg/g), followed by that in Boops boops (11.5 ± 0.73 µg/g) and then by that in Sardinella aurita (9.8 ± 0.53 µg/g), with the first two being significantly different from the Ni content in Trachurus trachurus (8.4 ± 0.62 µg/g) (p < 0.01). In other fish species, such as Barbus grypus and Barbus xanthopterus, the Ni content in their gills was relatively low (0.27 µg/g and 0.78 µg/g, respectively) [67].

Lead is absorbed in the bloodstream of marine aquatics, and accumulation may occur within the fish tissues, kidneys, liver, bones, and scales [68]. Pb can also accumulate within human body tissues after frequent consumption of contaminated seafood [69]. In a study on marine organisms using ICP-OES, the Pb content in sea bass was 1.32 ± 0.06 µg/g, which is lower than the legal limit of 2.0 µg/g Pb in Brazil [62]. In this present study, Pb levels were much higher. The Pb content in fish tissues ranged between 9.0 ± 0.05 µg/g and 28.8 ± 0.09 µg/g. Lead content was not significantly different in the different tissues. The internal organs and muscle exhibited higher values (µ = 23.0 ± 0.63 and 23.0 ± 0.72 µg/g, respectively), than for the skin (µ = 20.0 ± 0.75 µg/g) and bone (µ = 18.0 ± 0.93 µg/g), the latter being statistically lower than the first two (p < 0.001). When considering the fish species, the Pb content in Scomber colias (µ = 23.21 ± 0.55 µg/g) was higher than that in Boops boops and Sardinella aurita (µ = 21.21 ± 0.83 and 21.04 ± 0.60 µg/g, respectively), which were quite comparable, but significantly higher than the Pb content in Trachurus trachurus (µ = 18.49 ± 0.83 µg/g, p < 0.001). In a study by Olmedo and co-workers [54], the Pb content in Scomber scombrus and Trachurus trachurus were relatively low (0.004 µg/g, for both) when compared to those obtained in this present study. In another study [55], the Pb content was also very low in other fish species (Cirrhinus mrigala and Gibelion catla, 1.48 µg/g and 0.18 µg/g, respectively). According to the EU Commission [27] and FAO/WHO [70], the maximum limit for Pb in fish is 0.30 µg/g. However, in this study, higher quantities were reported.

Generally, zinc is recognized as one of the most important elements for human beings, where issues may arise if there are low intakes. However, exposure to high concentrations of this heavy metal may produce toxicological effects. In fish, zinc generally enters through the gills, body surface, and alimentary canal, while it is excreted through the gastrointestinal tract [50]. The resistance to toxicity depends on the fish species. In chronically high levels, it may cause stress to fish, leading to fatal consequences. In this study, Cyprinus carpio was reported to be a suitable biological indicator of Zn contamination in water [71]. In another study, the Zn concentrations in fish, mussels, and oysters were 12.3–31.2, 21.1–30.9, and 129–431 µg/g, respectively [72]. In this present study, the Zn content in fish tissues ranged from non-detectable quantities to 184.87 ± 0.63 µg/g. Although, the zinc levels in the different tissues were quite different, they were not significantly different from each other. The highest amount was observed in the skin (µ = 66.0 ± 7.0 µg/g), followed by muscle and internal organs (µ = 50.0 ± 7.8 and 46.0 ± 6.8 µg/g, respectively) and finally by the bone (µ = 39.0 ± 6.5 µg/g). When considering fish species, the Zn content in Boops boops (µ = 75.9 ± 8.82 µg/g), Scomber colias (µ = 17.2 ± 8.64 µg/g), and Sardinella aurita (µ = 44.9 ± 5.39 µg/g) were significantly different than that in Trachurus trachurus (µ = 14.5 ± 5.84 µg/g, p < 0.01). In a study by Shafi and co-workers [55], the Zn content was very high in the gills of Labeo rohita (146.90 µg/g) and Cyprinus carpio (282.31 µg/g).

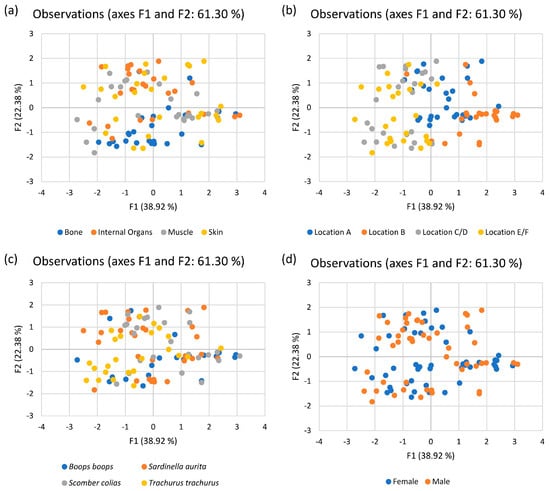

In order to consolidate the findings of this study, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted. PCA reduces the dimensionality of the dataset while retaining all the information provided on each sample. It is used as a visualization tool that can convert a high-dimensional dataset (with five metals, in this case) to a two-dimensional model that can be easily interpreted in terms of sample characteristics.

Table 6 illustrates the Spearman correlation between the heavy metals. The table shows that zinc correlated positively with nickel (rs = 0.589). The other metals did not show any significant correlations.

Table 6.

Correlation matrix (Spearman (rs)) between the heavy metals.

The variability observed between the samples is described by the first two principal components, which accounted for 61.30% (38.92% and 22.38%, respectively). Factor 1 is heavily loaded on Ni, Pb, and Zn, whereas factor 2 is heavily loaded on Cr and Cu. Observation plots were adopted for the different descriptions mentioned above, namely tissue type, location, fish species, and sex, by configuring the observations described in line with the parameters. Figure 3 shows all four observation plots.

Figure 3.

Observation plots for (a) type of tissue, (b) location of catch, (c) fish species, and (d) fish sex.

Considering metals by type of tissue, in general, the bone (represented by the blue dots in Figure 3a) is low in metals like Zn, Pb, and Cu as opposed to the other tissues, but high in Ni and Cr. On the other hand, muscle (represented by the grey dots) is low in Cu but high in Zn, Pb, Ni, and Cr. For the skin and internal organs (yellow and orange dots, respectively), the samples are scattered throughout the plot. Figure 3b illustrates clustering of locations A and B (blue and orange dots, respectively) on the right-hand side of the plot and clustering of locations C/D and E/F (grey and yellow spots, respectively) on the left-hand side of the plot. This clustering is due to fish caught in locations A and B showing higher levels of Ni, Pb, and Zn, but lower levels of Cu. Figure 3c shows that the distributions of fish specimens of all four species are relatively scattered. However, for Boops boops and Trachurus trachurus (blue and yellow dots, respectively), the samples are concentrated at the lower part of the plot, characterized by lower Cu and Pb than for Sardinella aurita and Scomber colias (orange and grey dots, respectively). As Boops boops and Sardinella aurita are omnivores while Trachurus trachurus and Scomber colias are carnivores, the omnivores and carnivores could not be classified with respect to the metal content in their tissues. Figure 3d shows the scattered samples through the plot for both males (orange dots) and females (blue dots). This means that the contamination of species is not sex-specific.

In general parasites and heavy metals are most prominent in fish species. Unfortunately, not all contaminants are taken into consideration. Depending on the quantity and the term of exposure from consuming fish, risks of development issues and illnesses may arise and affect human health. The objective of this research was to detect contaminants such as Anisakis parasites and the five types of heavy metal contaminants in wild fish species for the safeguard of food consumption in Maltese waters. In this analysis performed on four native marine species, which are Trachurus trachurus, Scomber colias, Boops boops, and Sardinella aurita, the methodology used to detect Anisakis showed that the digestion method was more accurate and reliable than the visual inspection in view of actual quantification of parasites. From the results, the fish species most prone to Anisakis was found to be Scomber colias, followed by Trachurus trachurus and Sardinella aurita. However, no contamination with parasites was found in fish species of Boops boops. It was also observed that the larger the fish size, in length and weight, the higher the risk of contamination with Anisakis.

5. Conclusions

This study concluded that the two carnivorous fish species (Scomber colias and Trachurus trachurus) are more prone to Anisakis infestation than the two omnivorous fish species (Boops boops and Sardinella aurita). Furthermore, it can be concluded that heavy metal contamination does not discriminate between fish species and sex, although it was observed that there were differences between fish tissue type and location of catch surrounding Malta, particularly in the south-eastern region of the island. Certain metals, such as Zn and Pb, in fish tissues seemed to accumulate mostly in muscle when compared to other fish tissues. Although fish products are subject to inspection, not all contaminated products are intercepted, thus placing public health at risk. Beyond re-enforcement and compliance with existing international and EU regulations, industry can proactively implement measures to improve early detection of contaminants and hence reduce the risk of clinical cases, recalls, and financial losses, amongst others. This approach will not only reduce the risk of health hazards but also improve the quality of food and market stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V.-T. and E.A.; methodology, R.V.-T., R.V.-A. and E.A.; validation, R.V.-T., R.V.-A. and E.A.; formal analysis, R.V.-T.; investigation, R.V.-T. and E.A.; resources, E.A.; data curation, R.V.-A. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V.-T. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, R.V.-A.; supervision, E.A.; funding acquisition, E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was submitted and approved by the University Research Ethics Committee of the University of Malta (IES-2022-00042, 24-01-2023). As the study did not involve live animals, no ethical concerns were identified.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. No voucher specimens were deposited in a formal collection. The material has been preserved and is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Veterinary Laboratory, Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Animal Rights, for hosting and assisting with part of the experimental work on Anisakis parasite detection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cuttelod, A.; García, N.; Abdul Malak, D.; Temple, H.; Katariya, V. The Mediterranean: A Biodiversity Hotspot Under Threat; Wildlife in a Changing World–an analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; Volume 89, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Aguzzi, J.; Voultsiadou, E. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, J.A.; Dandria, D.; Evans, J.; Knittweis, L.; Schembri, P.J. A Critical Checklist of the Marine Fishes of Malta and Surrounding Waters. Diversity 2023, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFA. Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Animal Rights. Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture—Catch and Effort Database. 2023. Available online: https://nso.gov.mt/agriculture-and-fisheries-fisheries/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Khalili Tilami, S.; Sampels, S. Nutritional value of fish: Lipids, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2018, 26, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; O’Donnell, M.; Hu, W.; Yusuf, S. Associations of fish consumption with risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality among individuals with or without vascular disease from 58 countries. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dighriri, I.M.; Alsubaie, A.M.; Hakami, F.M.; Hamithi, D.M.; Tayeb, H.O.; Alwadei, A.M.; Alshammari, T.M. Effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on brain functions: A systematic review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30022. Available online: https://www.cureus.com/articles/116591-effects-of-omega-3-polyunsaturated-fatty-acids-on-brain-functions-a-systematic-review.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.; Abbas, M.M.M.; Afifi, M.A.M.; El-Sayed, M.A.M.; El-Khodery, S.A. Fish parasites and heavy metals relationship in wild and cultivated fish as potential health risk assessment in Egypt. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 890039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonković, D.; Tešić, V.; Šimat, V.; Karabuva, S.; Medić, A.; Vrbatović, A. Anisakidae and anisakidosis: A public health perspective. Pathogens 2025, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubojević, D.; Novakov, N.; Djordjević, V.; Radosavljević, V.; Pelić, M.; Ćirković, M. Potential parasitic hazards for humans in fish meat. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 5, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daripa, A.; Malav, L.C.; Yadav, D.K.; Chattaraj, S. Metal contamination in water resources due to various anthropogenic activities. In Metals in Water; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: Toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, P.; Banerjee, P.; Mondal, P.; Saha, N.C. Effect of heavy metals on fishes: Toxicity and bioaccumulation. J. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, S18, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Agbugui, M.O.; Abe, G.O. Heavy metals in fish: Bioaccumulation and health. BJESR 2022, 10, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo, L.; Sala, M.; Focardi, C.; Pasqualetti, P.; Delfino, D.; D’Onofrio, F.; Neri, B. Monitoring of cadmium, lead, and mercury levels in seafood products: A ten-year analysis. Foods 2025, 14, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deeb, A.K.; El-Bialy, B.E.; El-Borai, N.B.; Elsabbagh, H.S. Nickel: A review on environmental distribution, toxicokinetics, and potential health impacts. J. Curr. Vet. Res. 2025, 7, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, E.K.; Hu, H. Lead toxicity in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osredkar, J.; Sustar, N. Copper and zinc, biological role and significance of copper/zinc imbalance. J. Clin. Toxicol. 2011, 3, 0495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Long, M. Copper toxicity in animals: A review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 2675–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, R.K. Excessive intake of zinc impairs immune responses. JAMA 1984, 252, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Kamila, S.; Chattopadhyay, A. Toxic and carcinogenic effects of hexavalent chromium in mammalian cells in vivo and in vitro: A recent update. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2022, 40, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Code of Practice for Fish and Fishery Products; CAC/RCP 52-2003; FAO/WHO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Off. J. Eur. Union 2004, L139, 55–205. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32004R0853 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bortolaia, V.; Bover-Cid, S.; De Cesare, A.; Dohmen, W.; Guillier, L.; Herman, L.; Jacxsens, L.; Nauta, M.; et al. EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ). Re-evaluation of certain aspects of the EFSA Scientific Opinion of April 2010 on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products, based on new scientific data. Part 2. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific opinion on the risk for public health related to the presence of mercury and methylmercury in food. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Codex General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and Feed (CODEX STAN 193-1995); FAO/WHO: Rome, Italy, 1995; revised 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B193-1995%252FCXS_193e.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L364, 5–24. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006R1881 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- European Union Reference Laboratory for Parasites. Detection of Parasites in Fish Fillet by Artificial Digestion: Standard Operating Procedure (SOP); Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/POP-04+(rev+3)+Artificial+digestion+of+fish+fillet.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- ISO 23036-2:2021; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Methods for the Detection of Anisakidae L3 Larvae in Fish and Fishery Products—Part 2: Artificial Digestion Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/74373.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Papapostolou, E.N.; Chaintoutis, S.C.; Gousia, P.; Karpouza, A.; Kachrimanidou, M.; Diakou, A. Food safety concerns: Anisakis spp. in ready-to-eat fish from the Greek market. Pathogens 2025, 14, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, D.; Attard, E. Honeybees and their products as bioindicators for heavy metal pollution in Malta. Acta Bras. 2020, 4, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, D.A.; Tillman, M.D.; Hubbs, L.M. Limit of detection (LQD)/limit of quantitation (LOQ): Comparison of the empirical and the statistical methods exemplified with GC–MS assays of abused drugs. Clin. Chem. 1994, 40, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Bayhan, B. Length–weight and length–length relationships of the bogue Boops boops (Linnaeus, 1758) in Izmir Bay (Aegean Sea of Turkey). Belg. J. Zool. 2008, 138, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Moutopoulos, D.K.; Stergiou, K.I. Length–weight and length–length relationships of fish species from the Aegean Sea (Greece). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2002, 18, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikliras, A.C.; Koutrakis, E.T.; Stergiou, K.I. Age and growth of round sardinella (Sardinella aurita) in the northeastern Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 2005, 69, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikliras, A.C.; Antonopoulou, E. Reproductive biology of round sardinella (Sardinella aurita) in the north-eastern Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 2006, 70, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahel, A.; Tahri, M.; Bensouilah, M.; Amara, R.; Djebar, B. Growth, age and reproduction of Sardinella aurita and Sardina pilchardus in the Algerian eastern coasts. AACL Bioflux 2016, 9, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, E.M.; Árbol-Pérez, J.P.; Baro, J.; Sobrino, I. Age and growth of the Spanish chub mackerel Scomber colias off southern Spain. Cybium 2011, 36, 406–408. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.M. New biological data on growth and maturity of Spanish mackerel (Scomber japonicus) off the Portuguese coast. ICES CM 1996, 1–23, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, M.R.; Villamor, B.; Myklevoll, S.; Gil, J.; Abaunza, P.; Canoura, J. Maximum size of Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) and Atlantic chub mackerel (Scomber colias) in the Northeast Atlantic. Cybium 2012, 36, 406–408. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, M.; Karadurmuş, U. Age, growth, length–weight relationship and reproduction of the Atlantic horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) in Ordu (Black Sea). Ordu Univ. J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaycı, F.; Samsun, N.; Bilgin, S.; Samsun, O. Length–weight relationship of 10 fish species caught by bottom trawl and midwater trawl from the Middle Black Sea, Turkey. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2007, 7, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ). Scientific opinion on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraulo, P.; Morena, C.; Costa, A. Recovery of anisakid larvae by means of chloro-peptic digestion and proposal of the method for the official control. Acta Parasitol. 2014, 59, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCIA. Allergic and Toxic Reactions to Seafood; Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy: Sydney, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://www.allergy.org.au/images/pc/ASCIA_PC_Seafood_Allergy_FAQ_2024.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Prester, L. Seafood allergy, toxicity, and intolerance: A review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2014, 35, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baher, W.M.; Darwish, W.S.E.A.; Elhelaly, A.E. Prevalence and public health significance of Anisakis larvae in some marketed marine fish in Egypt. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2022, 10, 1303–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, C.; Gustinelli, A.; Fioravanti, M.L.; Caffara, M.; Mattiucci, S.; Cattaneo, P. Prevalence and mean intensity of Anisakis simplex (s.s.) in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) from the Northeast Atlantic Ocean. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 148, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczyńska, J.; Paszczyk, B. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and lipid quality indexes in freshwater fish from lakes of Warmia and Mazury Region, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Yousafzai, A.M.; Siraj, M.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, I.; Nadeem, M.S.; Ahmad, W.; Akbar, N.; Muhammad, K. Pollution problem in River Kabul: Accumulation estimates of heavy metals in native fish species. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 537368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli, M.; Atli, G. The relationships between heavy metal (Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Pb, Zn) levels and the size of six Mediterranean fish species. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 121, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strungaru, S.A.; Nicoarã, M.; Rãu, M.A.; Plãvan, G.; Micu, D. Do you like to eat fish? An overview of the benefits of fish consumption and risk of mercury poisoning. Biol. Anim. 2015, 61, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sonone, S.S.; Jadhav, S.; Sankhla, M.S.; Kumar, R. Water contamination by heavy metals and their toxic effect on aquaculture and human health through food Chain. Lett. Appl. Nano BioSci. 2020, 10, 2148–2166. [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo, P.; Pla, A.; Hernández, A.F.; Barbier, F.; Ayouni, L.; Gil, F. Determination of toxic elements (Hg, Cd, Pb, Sn and As) in fish and shellfish: Risk assessment for consumers. Environ. Int. 2013, 59, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, J.; Mirza, Z.S.; Kosour, N.; Zafarullah, M. Assessment of heavy metals content in organs of edible fish species of River Ravi in Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2023, 33, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, A.; Panigrahi, A.K. A comprehensive review on chromium-induced alterations in freshwater fishes. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Yousafzai, A.M. Chromium toxicity in fish: A review. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2017, 5, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Owhonda, N.K.; Ogali, R.E.; Ofodile, S.E. Assessment of chromium, nickel, cobalt and zinc in edible flesh of two tilapia species from Bodo River, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2016, 20, 560–564. [Google Scholar]

- Azmat, H.; Javed, M. Acute toxicity of chromium to Catla catla, Labeo rohita and Cirrhina mrigala under laboratory conditions. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2011, 13, 961–965. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance Document for Chromium in Shellfish; DHHS/PHS/FDA/CFSAN/Office of Seafood: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, U.; Oehlenschläger, J. Determination of zinc and copper in fish samples collected from the Northeast Atlantic by DPSAV. Food Chem. 2004, 87, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, V.A.; dos Santos Vieira, E.V. Determination of Cd, Pb, Ni, Co and Cu in seafood after dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2014, 31, 1872–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasim, P.; Filipek, T. Nickel in the environment. J. Elem. 2015, 20, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, K.V.; Schlekat, C.E.; Garman, E.R. The mechanisms of nickel toxicity in aquatic environments: An adverse outcome pathway analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurganari, L.; Dastageer, G.; Mushtaq, R.; Khwaja, S.; Uddin, S.; Baloch, M.I.; Hasni, S. Assessment of heavy metals in cyprinid fishes from rivers of Khuzdar District, Balochistan, Pakistan. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 84, e256071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yeung, K.W.; Zhou, G.J.; Yung, M.M.; Schlekat, C.E.; Garman, E.R.; Gissi, F.; Stauber, J.L.; Middleton, E.T.; Wang, Y.Y.L.; et al. Acute and chronic toxicity of nickel on tropical aquatic organisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, T.; Kopernicka, M.; Harangozo, Ľ.; Bobkova, A.; Bobko, M. Mercury and nickel contents in fish meat. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 49, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nussey, G.; van Vuren, J.H.J.; du Preez, H.H. Bioaccumulation of Cr, Mn, Ni and Pb in tissues of Labeo umbratus from Witbank Dam, Mpumalanga. Water SA 2000, 26, 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, A.C.; O’Neill, B.; Sigge, G.O.; Kerwath, S.E.; Hoffman, L.C. Heavy metals in marine fish meat and consumer health: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Codex Alimentarius—International Food Standards. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/thematic-areas/contaminants/en/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Al-Zamili, H.A.A.; Hameed, S. Effect of water pollution by zinc on common carp (Cyprinus carpio): Biochemical parameters and GPx/MT gene expression. J. Degrad. Min. Lands Manag. 2025, 12, 8315–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilandžić, N.; Sedak, M.; Đokić, M.; Varenina, I.; Kolanović, B.S.; Božić, Đ.; Brstilo, M.; Šimić, B. Zinc in foods of animal origin, fish and shellfish from Croatia and contribution to dietary intake. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 35, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.