Abstract

Iron deficiency anemia remains a major public health concern in Brazil, particularly among children, pregnant women, and women of childbearing age. This scoping review aimed to map the trend line of public policies on iron supplementation and food fortification implemented between 1977 and 2025. The review followed PRISMA-ScR guidelines and the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology, and included searches in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, Google Scholar, and official government documents. Three main strategies were identified: iron supplementation, mandatory food fortification, and nutrition education. Key milestones included the National Iron Supplementation Program, the 2002 ANVISA Resolution (RDC No. 344/2002) mandating wheat and corn flour fortification, and the launch of the NutriSUS program in 2014. Despite important normative and programmatic advances, persistent critical issues remain, including low adherence, inadequate monitoring, data discontinuity, and bureaucratic barriers. Strengthening intergovernmental coordination, improving information systems, and adopting more bioavailable iron compounds are essential to increase the effectiveness of public policies aimed at preventing and controlling iron deficiency anemia in Brazil.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia as a condition in which blood hemoglobin levels fall below established reference values for healthy individuals. Cut-off points are stratified according to age group and physiological status, categorized as follows: children aged 6–23 months (<105 g/L), children aged 24–59 months (<110 g/L), non-pregnant women (<120 g/L), and adult men (<130 g/L). During pregnancy, cut-off values range between <105 g/L and <110 g/L, depending on the trimester [1,2].

Anemia can result from multiple causes, including nutritional deficiencies, raised physiologic demand, chronic diseases, genetic disorders, and infections [3]. Iron deficiency anemia, the most common form, arises primarily from insufficient dietary iron intake and blood loss, which, in women, is attributed to the menstrual period, pregnancy, and postpartum hemorrhage [4,5].

Its homeostasis is regulated by hepcidin, a hormone produced in the liver that controls both intestinal absorption and the release of stored iron, thereby ensuring balance and preventing either deficiency or overload [6,7,8]. Furthermore, iron deficiency (ID) may be exacerbated by the lack of other micronutrients required for iron metabolism, such as vitamin A, folate, vitamin B12, and riboflavin [8].

Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most prevalent nutritional deficiencies worldwide and represents a major public health concern. In 2023, the WHO estimated that 30.7% of women of reproductive age (15–49 years) were affected by this condition, with prevalence rates of 35.5% in pregnant women, 30.5% in non-pregnant women and 39.8% in children aged 6–59 months corresponding to approximately 571 million women and 269 million children globally [9,10].

In Brazil, the National Study of Child Food and Nutrition (ENANI-2019), conducted by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), reported anemia in 10% of children under five years of age, with 3.5% of cases specifically attributed to ID. The highest prevalence was observed in the North region, particularly among children aged 6 to 23 months, where supplement coverage is limited. The use of supplements varied substantially across regions, with the lowest coverage recorded in the North [11,12].

Given the persistently high prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in Brazil, particularly among vulnerable groups such as young children, women of reproductive age, and pregnant women, the implementation of effective public policies for its prevention and control remains a pressing need [13]. Although the epidemiological relevance of the condition has been recognized for decades, and national debates on the subject have been ongoing since 1977, there is still a notable lack of comprehensive scoping reviews that systematically analyze the evolution, barriers, and impacts of Brazilian public health strategies addressing ID.

Over the years, Brazil has implemented a series of initiatives, including large-scale supplementation programs and mandatory food fortification, which have been designed to reduce the burden of anemia in priority populations. However, these policies have faced challenges related to adherence, regional inequalities in coverage, insufficient monitoring systems, and limited integration with broader nutritional and health strategies.

In this context, the present scoping review aims to map the trend line of national policies on iron supplementation and/or food fortification in Brazil from 1977 to 2025. The review provides a broad overview of their historical development, identifies target populations, and examines implementation strategies as well as limitations encountered along the way. By synthesizing this evidence, the aim is to contribute to a deeper understanding of the successes and shortcomings of existing policies and to inform future strategies for addressing iron deficiency anemia within the Brazilian public health system.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the international guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [14] database is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Checklist S1) and the methodology proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [15], with the objective of mapping Brazilian public policies on iron supplementation and/or food fortification for the prevention and control of iron deficiency anemia between 1977 and 2025. The protocol for this review was prospectively registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) [16].

The research question was developed using the PCC framework: Population (children, pregnant women, and women of reproductive age); Concept (public policies focused on iron supplementation or fortification); and Context (Brazil, from 1977 to 2025).

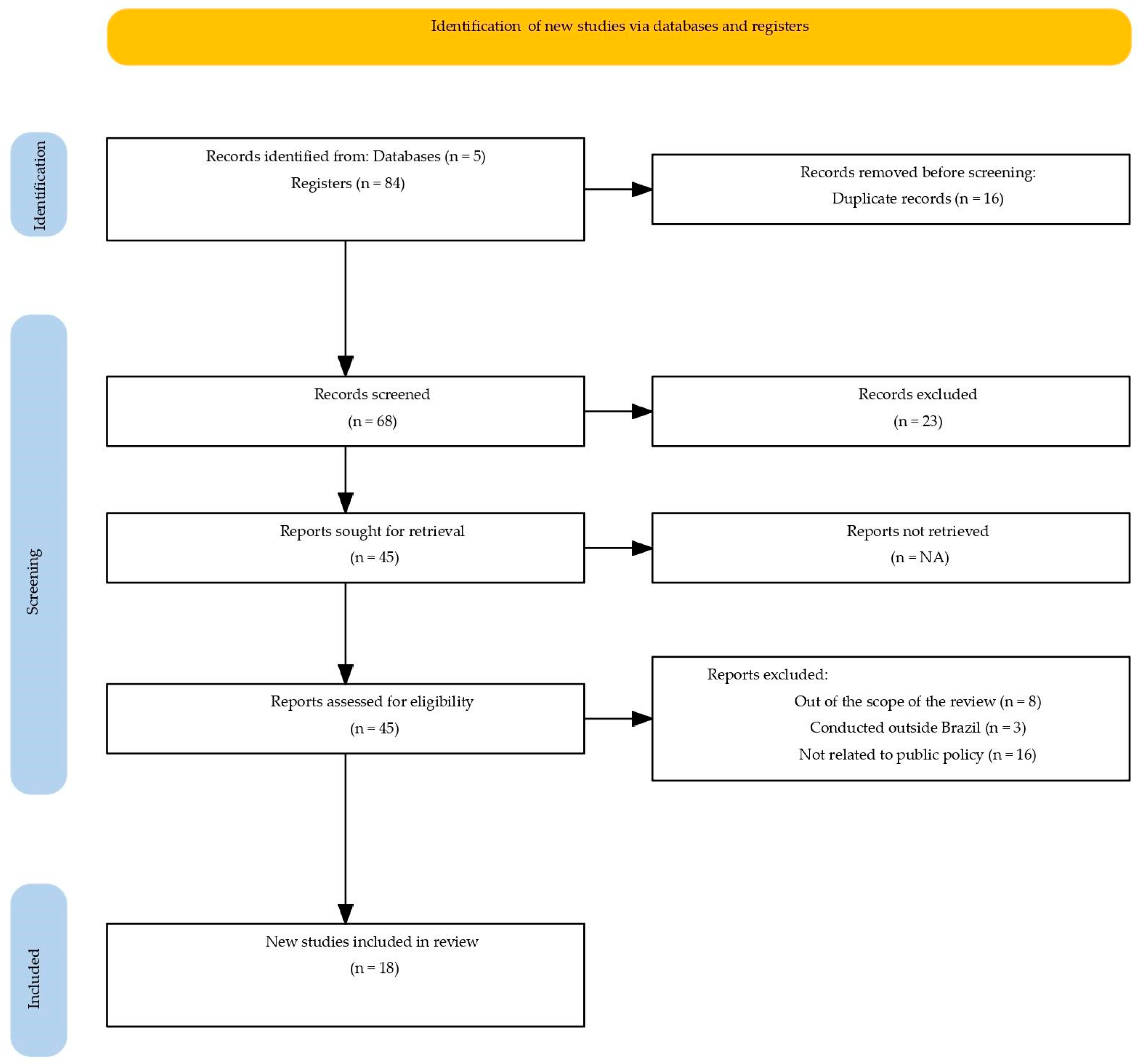

The searches were carried out in February 2025 in the PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and Google Scholar databases (Figure 1), as well as in official documents from the Ministry of Health (MS), the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA), and the Virtual Health Library (BVS). The full electronic search strategy used for the PubMed/MEDLINE database is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). Validated descriptors from BVS were used in Portuguese and English, including: anemias; anemia, iron deficiency; iron deficiency anemias; public policy; health policy; government programs; Brazil.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram of the study selection process.

Original studies and normative documents addressing public policies on iron in Brazil, published from 1977 onwards, that is, the historical milestone marking the beginning of the national agenda for anemia control were included. Eligible documents were those written in Portuguese, English, or Spanish. Exclusion criteria comprised studies conducted outside Brazil, without connection to public policies, or with an exclusive focus on the clinical or pathophysiological aspects of anemia.

Study selection was performed independently by two reviewers, in two stages: (i) title and abstract screening, and (ii) full-text assessment of eligible records. The process was managed using the Rayyan software, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Data extracted included: type of intervention, target population, dosage, coverage, adherence, and main outcomes. The synthesis was descriptive and presented in both narrative and tabular formats.

3. Results

The process of study identification and selection, detailed in the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1), started with 84 publications. After the removal of duplicates and screening, 45 articles proceeded to full-text review, resulting in the exclusion of 27 for not meeting the eligibility criteria: out of scope, conducted outside Brazil, or not related to public policies. Thus, a total of 18 studies and normative documents related to public policies on iron supplementation and fortification implemented between 1977 and 2025 were included. The findings were organized into four main themes: the historical evolution of public policies; types of interventions and forms of iron used; target populations; and operational limitations. This framework allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory advances, coverage gaps, and barriers affecting the effectiveness of these actions.

In addition to identifying policy milestones, the selected documents describe how different interventions were structured and implemented over time, reflecting progressive changes in national strategies for the prevention and control of iron deficiency anemia.

Initial actions focused on pregnant women and the incorporation of therapeutic or prophylactic supplementation into prenatal care. Subsequently, policies evolved toward universal flour fortification and, more recently, toward early childhood strategies through the use of multivitamin powders (MNP). Among the publications included, recurring operational results were reported, such as the standardization of dosage regimens, the expansion of target populations, the incorporation of monitoring and evaluation procedures, and the definition of responsibilities at the federal, state, and municipal levels. Despite these regulatory advances, the documents also highlight persistent barriers such as irregular supply of supplements, low adherence due to adverse effects, limited local monitoring capacity, and marked regional inequalities, which help contextualize the effectiveness of these interventions over the decades.

Table 1 below presents the main normative and programmatic milestones related to iron supplementation and food fortification policies in Brazil over the past five decades. The information includes the period of implementation, type and nature of the intervention, target population, and recommended dosages. In addition, the data provide an overview of the historical trend line of national strategies aimed at preventing and controlling iron deficiency anemia, highlighting the evolution of regulatory frameworks and shifts in public health priorities.

Table 1.

Public policies on iron supplementation and/or food fortification implemented in Brazil (1977–2025).

4. Discussion

4.1. Historical Evolution of Brazilian Public Policies (1977–2025)

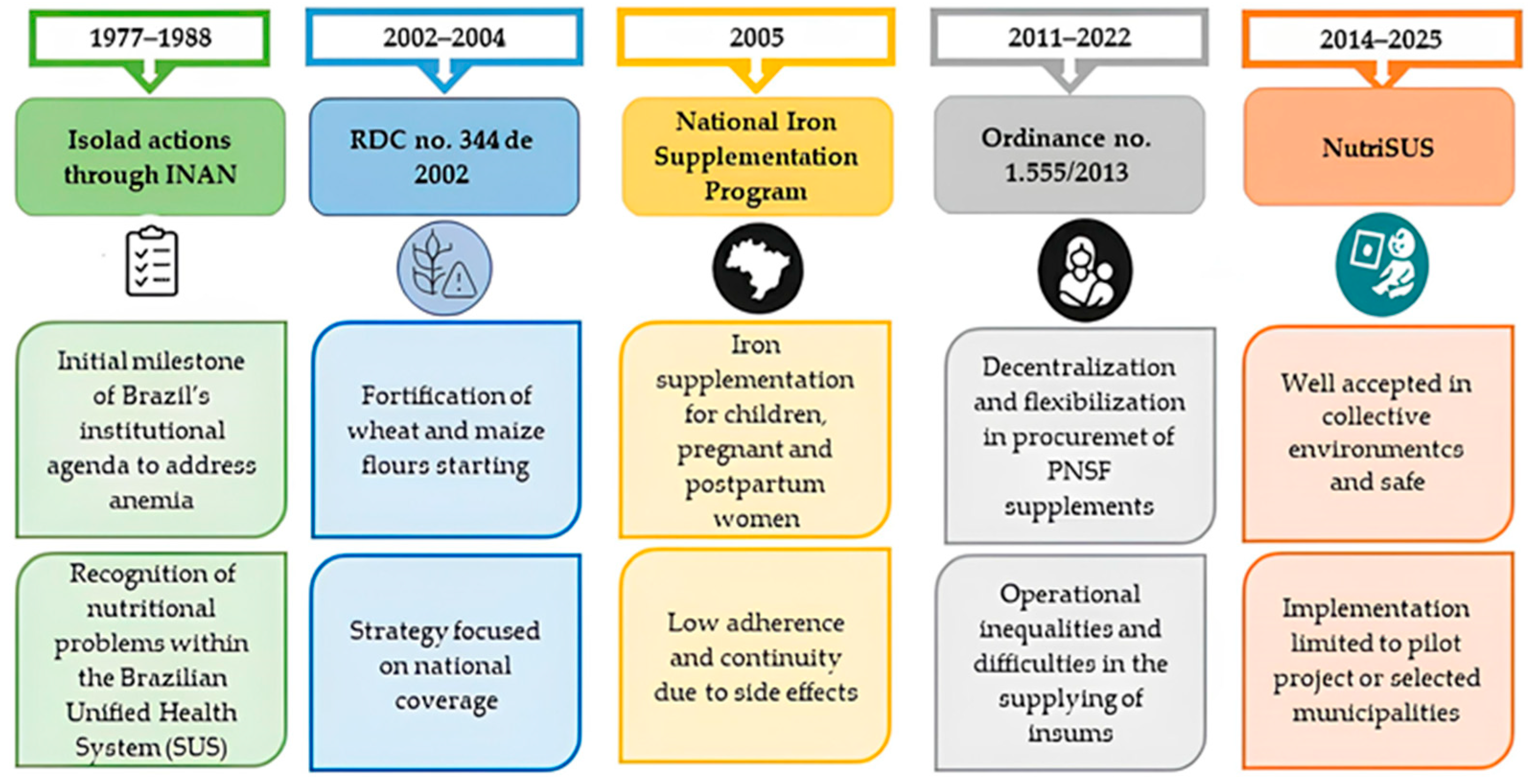

The efforts to address iron deficiency anemia in Brazil began in 1977 with the first technical meeting organized by the now-defunct National Institute of Food and Nutrition (INAN), under the Ministry of Health. During this meeting, strategies to increase iron intake in the country were discussed. This event marked the first official recognition of ID as a public health problem and represented a political–institutional milestone by placing nutritional anemia on the governmental agenda and aligning Brazil with international strategies to enhance iron consumption. However, its effectiveness was limited by the fragmented health system that existed at the time [17].

A few years later, in 1982 and 1983, the Programa de Atenção à Gestante (Pregnant Women Care Program, PAG) implemented the first nationwide iron supplementation intervention using ferrous sulfate (Fe2+), targeting all pregnant women assisted in Primary Health Units. The program also included anemia diagnosis through hemoglobin testing, aiming to interrupt the deficiency cycle and prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes. Although limited in scope, these interventions served as the first practical experience of population-level supplementation, revealing challenges in adherence, logistical barriers, and insufficient monitoring, and highlighting the need for more comprehensive and structured public health policies [13].

The creation of the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde—SUS) in 1988 provided the legal and institutional foundation for the development of broader public policies in the field of food and nutrition [26]. Unlike the isolated initiatives of previous decades, the SUS enabled the expansion of coordinated national programs that linked anemia prevention to permanent public health strategies, while ensuring an equitable approach to access and care [26,27].

The international scenario also played a decisive role. In 1990, the New York Summit recognized anemia prevention as a global priority, and in 1992, Brazil made its first international commitment to establish a national control program. Initially focused on women of reproductive age, the targets were later expanded to include preschool-aged children, encouraging the conduct of nutritional surveys and the implementation of more consistent interventions for the prevention and control of anemia [17].

In 2002, the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) issued Resolution RDC No. 344, mandating the fortification of wheat and corn flours with iron and folic acid. However, this regulation only came into effect in 2004, following an 18-month grace period granted to industries for compliance with the new standards. Despite representing a significant regulatory milestone, its effectiveness was limited due to deficiencies in enforcement, the use of compounds with low bioavailability (such as reduced iron), and the lack of systematic monitoring [18,28,29,30]. Subsequently, Resolution RDC No. 150/2017 revised the regulation by restricting the permitted compounds and adjusting dosage limits. More recently, Resolution RDC No. 604/2022 consolidated the current regulatory framework, repealing earlier provisions [23,24].

The National Iron Supplementation Program (Programa Nacional de Suplementação de Ferro—PNSF) was established in 2005, targeting children aged 6 to 24 months, pregnant women from the 20th week of gestation, and postpartum women up to the third month after delivery [19]. In 2013, the decentralization of supplement procurement sought to increase local autonomy; however, it also resulted in operational inequalities among municipalities [20,31]. Despite its nationwide scope, studies have reported low adherence rates due to the gastrointestinal side effects of ferrous sulfate (Fe2+), as well as logistical failures in the regular distribution of supplements and limited information among caregivers and health professionals, which have constrained the program’s overall effectiveness in reducing anemia prevalence [19,20,32].

In 2014, the NutriSUS program was launched as a home fortification strategy using sachets containing multiple micronutrients, aimed at children aged 6 to 48 months enrolled in public daycare centers. This initiative functioned as a complementary measure to the PNSF and demonstrated positive outcomes in pilot projects, including improvements in hemoglobin levels among participating children. However, its coverage remained limited and heavily dependent on technical and institutional support [22,33,34,35].

Regulatory updates implemented in 2018 and 2021 adjusted supplementation schemes and incorporated NutriSUS into primary care initiatives, expanding eligibility criteria [25]. However, challenges persisted, such as low adherence, logistical failures, and insufficient monitoring of initiatives, hindering the policy’s sustainability [34,36].

In 2022, the Brazilian Ministry of Health updated both the PNSF and NutriSUS through the National Micronutrient Supplementation Programs Handbook. The PNSF revised the supplementation scheme for children aged 6 to 24 months, introducing a new model based on two intermittent cycles, consisting of three months of supplement administration followed by a three-month pause, after which a new cycle begins. In turn, the NutriSUS program established three distribution periods for micronutrient powder sachets: the first at 6 months, the second at 12 months, and the third at 18 months of age, with a 3- to 4-month break between each supplementation cycle [25].

More recently, in 2023, a preliminary version of the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines (PCDT) for Iron Deficiency Anemia was published, which incorporated more effective and safer formulations, such as ferric polymaltose, ferric carboxymaltose, and ferric derisomaltose [37]. However, according to Technical Note No. 371/2024 from Co-nitec and Request for Information No. 3333/2024, bureaucratic obstacles among ministerial departments have delayed its official publication, revealing weaknesses in governance and institutional coordination. The lack of robust monitoring systems and the slowness of decision-making processes continue to compromise the effectiveness of public policies aimed at the prevention and treatment of iron deficiency anemia in Brazil [38].

Figure 2 summarizes the trajectory of Brazilian public policies, highlighting significant regulatory advances as well as persistent limitations related to operational effectiveness and coverage.

Figure 2.

Evolution of Brazilian public policies on iron deficiency anemia, 1977–2025.

Therefore, although Brazil has established regulatory advances and expanded its public policies from mandatory fortification to supplementation and home fortification programs, it still faces numerous operational challenges and governance weaknesses. This highlights that, despite institutional frameworks, the efforts to date have been insufficient to reduce iron deficiency anemia at the population level.

4.2. Types of Interventions and Iron Formulations Used

National strategies have primarily relied on medicinal supplementation and food fortification [17]. Supplementation is carried out through the free distribution of iron in the form of Fe2+ (oral solution, tablets, or powder), available at Basic Health Units for children aged 6 to 24 months, pregnant women from the 20th week of gestation, and postpartum women up to the third month after delivery, as established by the National Iron Supplementation Program guidelines [13,19].

However, the effectiveness of these strategies depends on the formulation characteristics of the formulations employed. Within the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), inorganic forms are generally used, which exhibit lower efficacy when compared to compounds with higher bioavailability. Nevertheless, these more bioavailable forms are considerably more expensive, limiting their large-scale adoption in public health programs [28,39]. Effective iron replacement requires high doses, ranging from 50 to 200 mg/day of elemental iron for 3 to 12 weeks. However, the intestine’s capacity to absorb iron is limited to approximately 10–20%. Thus, the unabsorbed luminal iron can cause gastrointestinal adverse effects and disrupt the intestinal microbiota [39,40,41].

Consequently, the side effects associated with the use of ferrous iron (Fe2+), such as nausea and constipation, are among the main causes of low adherence, particularly among children and pregnant women. The degree of adherence varies according to the type of formulation. The oral solution is suitable for pediatric use, as it allows dose adjustment based on body weight; however, it is often linked to gastrointestinal side effects and poor palatability. Conversely, tablet formulations are more practical for pregnant women and adults, although they still present tolerability challenges [36,40]. Powder formulations, such as those used in the NutriSUS program, have better acceptance because they can be mixed with food and cause less gastrointestinal discomfort, although their effectiveness depends on the acceptance of the fortified food, variation in the ingested dose, and consistency of distribution [34,36,40].

In parallel with individual supplementation, mandatory flour fortification, implemented in 2002, aimed to reach the entire population through the industrial addition of micronutrients to commonly consumed foods [18]. However, its effectiveness has been limited not only by variations in the iron concentrations used by the food industry and the lack of systematic monitoring [28], but also by the type of compound employed. The food industry has generally used reduced iron, a form with low bioavailability, thereby diminishing the overall efficacy of the fortification strategy [29].

In practice, the outcomes of this policy in Brazil have been limited. A study conducted among Brazilian children under six years of age showed little or no significant impact from flour fortification. The low effectiveness observed in this group has been attributed to the low consumption of wheat and corn flours and to the poor bioavailability of the iron compound used [42,43]. On the other hand, among pregnant women, the results were more positive, with a modest reduction in the prevalence of anemia from 25% to 20%. Therefore, this improvement was particularly notable in the North and Northeast regions, where anemia rates had previously been higher [29].

This limitation observed in the Brazilian context contrasts with the strategies implemented in other countries. Indeed, the effectiveness of flour fortification as a public health intervention is well supported by global evidence. A comprehensive systematic review demonstrated that this practice reduced the risk of anemia by approximately 27% among individuals over two years of age, compared with the consumption of non-fortified flour. Moreover, the study highlighted those countries employing more bioavailable iron compounds, such as NaFeEDTA, or ensuring adequate levels of ferrous sulfate or fumarate, achieved greater impacts, as observed in Morocco and particularly in Uzbekistan [44].

In this context, and with the goal of improving the national strategy, regulatory updates have redefined the technical standards currently in force in Brazil. The first major revision occurred in 2017 with RDC No. 150, which limited the authorized compounds to ferrous sulfate and ferrous fumarate (with or without encapsulation) and adjusted the dosage limits to 4–9 mg of iron and 140–220 μg of folic acid per 100 g of flour [23]. These specifications were later reaffirmed in 2022 through RDC No. 604, which consolidated the current regulations by revoking the previous resolution [24].

Given the limitations of both individual supplementation and universal fortification, the NutriSUS program was proposed, introducing powdered formulations supplied in 1 g single-dose sachets containing iron and 14 other micronutrients, including zinc, vitamin A, and folic acid [22,33]. This strategy aimed to improve adherence, as it is better accepted when mixed with foods and causes fewer gastrointestinal discomforts. However, its implementation has remained largely limited to pilot projects, with low coverage and difficulties maintaining actions after the end of technical support. In practice, although NutriSUS has shown promising individual outcomes under controlled conditions, its national impact has been limited due to structural challenges in scaling up and ensuring sustainability [34,35].

Additionally, another approach has been explored through biofortification. A recent study on iron-biofortified common beans demonstrated that regular consumption of this type of food increases iron stores, improves cognitive function, and enhances physical capacity in anemic women, representing a viable alternative to pharmaceutical supplementation [45].

4.3. Target Populations of the Policies

The prioritization of vulnerable groups has been a central guideline in Brazil’s strategies to combat iron deficiency anemia. Initially, the focus was on children aged 6 to 24 months, pregnant women from the 20th week of gestation, and postpartum women up to the third month, in line with the guidelines of the National Iron Supplementation Program [29]. These groups are at greater risk of ID due to increased physiological demands during periods of rapid growth and pregnancy [28,46].

However, the implementation of interventions targeting these hard-to-reach populations faces significant challenges, including limited administrative capacity in remote municipalities and logistical barriers, which ultimately reduce the practical effectiveness of public health actions in these contexts [12].

Another critical issue is that supplementation for target groups is not always accompanied by educational actions, which compromises adherence, especially among women who do not perceive immediate benefits and caregivers of children who have experienced side effects or difficulties with administration [36,39]. Furthermore, children outside the standard age range, such as those under 6 months or over 2 years, also present an increased risk of anemia but are not systematically addressed in operational guidelines [47].

In the context of home fortification, the NutriSUS program was initially directed at children aged 6 to 48 months enrolled in public daycare centers, with the aim of expanding access in institutional settings [22]. From 2022 onwards, it shifted its focus to children aged 6 to 24 months assisted in Primary Health Care Units [33]. Despite evaluations indicating good acceptability, coverage remained limited and uneven across municipalities, particularly after the end of federal technical and financial support [34]. Official records from the monitoring system present data only for the period from 2017 to 2019, with no subsequent updates, highlighting the discontinuity of the strategy [48].

4.4. Program Coverage, Adherence, and Barriers to Effectiveness

Despite the consolidation of national strategies for the control of iron deficiency anemia, available data indicate that program coverage and adherence among target populations remain unsatisfactory, compromising their overall effectiveness [12,34,36].

According to the ENANI-2019 survey, only 21.7% of children aged 6–59 months were using iron supplements, with significant regional variation. In addition, the study also revealed that 10% of children under five presented anemia, with 3.5% of these cases attributed specifically to iron deficiency anemia. The North region of the country showed the highest rates, with 17% of anemia and 6.5% of iron deficiency anemia in children aged 6 to 23 months, underscoring the need for targeted interventions [11,12].

Evidence from local studies further illustrates this scenario. In Salvador (Bahia), between 2017 and 2022, supplementation coverage was below 7% among pregnant women and less than 1% among children [49]. Similarly, in Florianópolis (Santa Catarina), only 2.4% of children adhered to the recommended supplementation regimen [50].

Among the main factors explaining poor adherence are the side effects of ferrous sulfate, such as nausea, constipation, darkened stools, and child refusal, in addition to the lack of adequate professional follow-up [36,40]. Prescriptions made without prior anemia diagnosis and the absence of individualized care further hinder family engagement [12,50].

Difficulties are not limited to individual adherence. At the operational level, multiple structural and institutional barriers compromise the continuity and quality of program implementation. The decentralization of supplement procurement, formalized from 2011 onward, transferred to municipalities the responsibility for purchasing and distributing supplements [20,31]. While this change expanded local autonomy, it also generated administrative and budgetary inequalities, affecting the regularity of supply [12].

Another critical point is the weakness in monitoring and evaluation systems. Platforms such as the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System (SISVAN) and e-SUS remain underutilized or incompletely filled, making it difficult to analyze coverage, assess outcomes, and plan evidence-based actions [49,51].

In the case of home fortification with micronutrient powders (NutriSUS), coverage was limited to pilot projects in selected municipalities. Although sachets were well accepted by caregivers and program managers, the strategy failed to consolidate nationally, and its continuity was hampered by the lack of funding, technical supervision, and integration with health teams [34,35]. Moreover, the absence of a robust impact evaluation system prevents consistent conclusions regarding its effectiveness [48].

The difficulty in implementing targeted interventions is not unique to Brazil. In Canada, universal food fortification has also proven ineffective for vulnerable populations. Among remote Indigenous communities, the prevalence of iron-deficiency anemia has reached up to 50%, levels comparable to those observed in high-risk groups in Brazil. In response, a home fortification strategy using micronutrient sachets known as “Sprinkles”, similar to the NutriSUS approach, was implemented and shown to be effective and well accepted. The Canadian experience reinforces that, even in high-income countries, the elimination of anemia in specific subpopulations depends on targeted interventions, whose sustainability remains the main challenge [52].

Finally, the scarcity of continuous educational initiatives, combined with the limited training of primary health care teams, contributes to misinformation among the population about the benefits of supplementation and fortification, thereby undermining the achievement of public policy objectives [12,34]. These factors reveal a clear mismatch between normative guidelines and the realities of implementation across different territories.

The implementation challenges of the actions emphasized in this study for the Brazilian context contrast with the well-established effectiveness of such interventions. According to findings from systematic reviews compiled by the Cochrane Collaboration, iron supplementation and food fortification, whether administered alone or in combination with other micronutrients, have been shown to increase hemoglobin levels and reduce the risk of anemia in infants, preschool children, pregnant women, and women of reproductive age. Strategies such as the use of multiple micronutrient powders, fortification of cereals and dairy products, and even simple approaches like cooking food in iron pots have demonstrated positive effects, although the magnitude of these effects and the quality of the evidence vary among studies. Nonetheless, the reviews also highlight persistent limitations, including methodological heterogeneity, uncertainties regarding long-term safety, and a lack of research focused on adolescents, adult men, and the elderly [44,53,54,55].

Therefore, even though Brazil has decades of experience with supplementation and fortification programs, improvements in monitoring and evaluation remain necessary. The adoption of effective strategies for adherence, supervision, and performance assessment is essential to overcome persistent challenges and enhance the national response to anemia prevention.

4.5. Study Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The limitations identified in this study are mainly from the time frame (1977–2025), which, although necessary to trace the trajectory of policies, resulted in a dependence on normative documents and laws for the early years, given the scarcity of indexed scientific studies on the subject before a certain period. In addition, the exclusion of studies conducted outside Brazil and the restriction to research that had no direct connection with public policies limited the possibility of conducting international comparative analyses and deepening the debate on clinical outcomes outside the regulatory context.

Based on these gaps, future research should focus on three main areas. First, conducting studies on the effectiveness and cost–benefit of the most recent policies (2022 PNSF and NutriSUS guidelines) considering regional contexts. Second, international comparative studies are needed to evaluate the actions taken in other countries to identify and adapt the most successful strategies to the Brazilian scenario. Third, qualitative and operational research should be deepened to investigate logistical and adherence barriers, as well as to develop robust monitoring systems that use the integration of surveillance data (SISVAN and e-SUS) to help shape future policies based on scientific evidence.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review highlights the historical trajectory and current challenges of Brazilian public policies on iron supplementation and food fortification implemented between 1977 and 2025. The findings reveal that, while regulatory advances such as the establishment of the PNSF, the mandatory fortification of wheat and maize flours, and the introduction of NutriSUS have marked important milestones, their effectiveness remains limited. Persistent barriers include low adherence due to side effects of ferrous sulfate, operational inequalities among municipalities following the decentralization of supply management, and insufficient integration of supplementation with educational strategies.

Furthermore, monitoring systems such as SISVAN and e-SUS remain underutilized, and the discontinuity of initiatives—particularly NutriSUS—reflects fragilities in governance, financing, and institutional coordination. These structural limitations have prevented the consolidation of long-term, sustainable outcomes and have contributed to the persistent high prevalence of iron deficiency anemia, especially in vulnerable populations such as children, pregnant women, postpartum women, and Indigenous communities.

The evidence suggests that enhancing the effectiveness of these policies requires a multipronged approach. First, communication and health education strategies must be strengthened to improve awareness and adherence among target groups. Second, investment in more bioavailable iron formulations, such as NaFeEDTA and novel combinations with prebiotics, could significantly increase the nutritional impact of fortification programs. Third, robust and systematic monitoring mechanisms must be established to ensure accountability, continuity, and evidence-based adjustments to interventions.

Overall, the mismatch between normative advances and operational implementation remains the central barrier to achieving the full potential of Brazil’s iron supplementation and fortification policies. Addressing this gap will require political commitment, adequate financing, and stronger integration between national guidelines and local health systems. By aligning regulatory frameworks with practical realities, Brazil can improve the prevention and control of iron deficiency anemia and advance toward greater health equity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sci7040185/s1, Table S1: Full electronic search strategy for PubMed/MEDLINE; Checklist S1: PRISMA-ScR Checklist.

Author Contributions

For this article, É.L.F.L., N.A., K.d.C.F., V.A.d.N., P.A.H., R.d.S.F., A.C.I. and R.d.C.A.G. contributed equally to the conception, planning, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as writing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available in the published literature and listed in the References section.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Graduate Program in Health and Development in the Central-West Region, Medical School, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, and the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul-UFMS for the support. The authors also thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-CAPES). This research was partially supported by the Brazilian Research Council (CNPq) (CNPq: process 304312/2025-8 and CNPq: process no 313985/2023-5). This research was financially supported by the Brazilian Research Council (CNPq) (CNPq: Process No 314551/2023-9) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES)-Finance Code 001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANVISA | Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária [National Health Surveillance Agency] |

| ENANI | Estudo Nacional de Alimentação e Nutrição Infantil [National Study of Child Food and Nutrition] |

| Fe2+ | Ferrous Iron |

| PNSF | Programa Nacional de Suplementação de Ferro [National Iron Supplementation Program] |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RDC | Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada [Collegiate Board Resolution] |

| SUS | Sistema Único de Saúde [Unified Health System] |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guideline on Haemoglobin Cutoffs to Define Anaemia in Individuals and Populations, 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/375566 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Bellad, M.B.; Patted, A.; Derman, R.J. Is It Time to Alter the Standard of Care for Iron Deficiency/Iron Deficiency Anemia in Reproductive-Age Women? Biomedicines 2024, 12, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia 1993–2005: WHO Global Database on Anaemia; de Benoist, B., McLean, E., Egli, I., Cogswell, M., Eds.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241596657 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Kolarš, B.; Mijatović Jovin, V.; Živanović, N.; Minaković, I.; Gvozdenović, N.; Kokeza, I.D.; Lesjak, M. Iron Deficiency and Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Comprehensive Overview of Established and Emerging Concepts. Pharmaceutics 2025, 18, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.D.; Chong, Y.S.; Clemente-Chua, L.R.; Irwinda, R.; Huynh, T.N.K.; Wibowo, N.; Gamilla, M.C.Z.; Mahdy, Z.A. Prevention and management of iron deficiency/iron deficiency anemia in women: An Asian expert consensus. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Y.; Babitt, J.L. Hepcidin regulation in the anemia of inflammation. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2016, 23, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, Y. Iron Deficiency and Iron Deficiency Anemia: Potential Risk Factors in Bone Loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Anaemia. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Anaemia Estimates: Key Findings, 2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240113930 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Use of Micronutrient Supplements: Characterization of the Use of Micronutrient Supplements Among Brazilian Children Under 5 Years of Age. Brazilian National Survey on Child Nutrition (ENANI-2019). Available online: https://enani.nutricao.ufrj.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Relatorio-6-ENANI-2019-Suplementacao-de-Micronutrientes.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Castro, I.R.R.; Normando, P.; Alves-Santos, N.H.; Bezerra, F.F.; Citelli, M.; Pedrosa, L.d.F.C.; Junior, A.A.J.; de Lira, P.I.C.; Kurscheidt, F.A.; da Silva, P.R.P.; et al. Methodological aspects of the micronutrient assessment in the Brazilian National Survey on Child Nutrition (ENANI-2019): A population-based household survey. Cad. Saúde Pública 2021, 37, e00037221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarfarc, S.C. Public policies to control iron deficiency in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2010, 32, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libório, E.; Araujo, N.; Freitas, K.C.; Nascimento, V.A.; Hiane, P.A.; Bogo, D.; Guimarães, R.C.A. Brazilian Public Policies for the Prevention and Control of Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Scoping Review. Open Science Framework 2025 ; OSF: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista Filho, M.; Rissin, A. Nutritional Deficiencies: Specific Control Measures by the Health Sector. Cad. Saúde Pública 1993, 9, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução RDC n° 344, de 13 de Dezembro de 2002. Torna Obrigatória a Fortificação de Farinhas de Trigo e Milho com Ferro e Ácido Fólico; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2002. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2002/rdc0344_13_12_2002.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria GM/MS n° 730, de 13 de maio de 2005. Institui o Programa Nacional de Suplementação de Ferro (PNSF); Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2005. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2005/prt0730_13_05_2005.html (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria GM/MS n° 1.977, de 12 de Setembro de 2014. Altera a Portaria n° 730, de 2005; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2014. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2014/prt1977_12_09_2014.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria SCTIE/MS N° 28, de 13 de Agosto de 2014. Torna Pública a Decisão de Incorporar o Suplemento Alimentar em pó com Múltiplos Micronutrientes para Fortificação da Alimentação Infantil no âmbito do Programa NutriSUS; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2014. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/sctie/2014/prt0028_13_08_2014.html (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. NutriSUS: Caderno de Orientações: Estratégia de Fortificação da Alimentação Infantil com Micronutrientes (Vitaminas e Minerais) em pó. 2015. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/nutrisus_caderno_orientacoes_fortificacao_alimentacao.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Resolução RDC n° 150, de 13 de Abril de 2017. Dispõe Sobre o Regulamento Técnico Para Fortificação das Farinhas de Trigo e das Farinhas de Milho com Ferro e Ácido Fólico; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, DF, Brazil, 2017. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2017/rdc0150_19_04_2017.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Resolução RDC n° 604, de 10 de Fevereiro de 2022. Dispõe Sobre o Regulamento Técnico Para Fortificação das Farinhas de Trigo e das Farinhas de Milho com Ferro e Ácido Fólico; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, DF, Brazil, 2022. Available online: https://anvisalegis.datalegis.net/action/ActionDatalegis.php?acao=abrirTextoAto&tipo=RDC&numeroAto=00000604&seqAto=000&valorAno=2022&orgao=RDC/DC/ANVISA/MS&codTipo=&desItem=&desItemFim=&cod_menu=1696&cod_modulo=134&pesquisa=true (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Caderno dos Programas Nacionais de Suplementação de Micronutrientes; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2022. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/caderno_programas_nacionais_suplementacao_micronutrientes.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Brasil. Lei n° 8.080, de 19 de Setembro de 1990. Dispõe Sobre as Condições Para a Promoção, Proteção e Recuperação da Saúde, a Organização e o Funcionamento dos Serviços Correspondentes; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 1990. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8080.htm (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Marques, R.M.; Piola, S.F.; Roa, A.C. Sistema de Saúde no Brasil: Organização e Financiamento. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/sistema_saude_brasil_organizacao_financiamento.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Ferreira da Silva, L.; Dutra-de-Oliveira, J.E.; Marchini, J.S. Serum iron analysis of adults receiving three different iron compounds. Nutr. Res. 2004, 24, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, E.; Sato, A.P.S.; Szarfarc, S.C.; Veiga, G.V.; Oliveira, V.A.; Colli, C.; Moreira-Araújo, R.; de Arruda, I.K.G.; Uchimura, T.T.; Brunken, G.S.; et al. Anemia in Brazilian pregnant women before and after flour fortification with iron. Rev. Saude Publica 2011, 45, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L.J.; Dary, O. Governments and academic institutions play vital roles in food fortification: Iron as an example. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1791–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria n° 1.555, de 30 de Julho de 2013. Dispõe Sobre as Normas de Financiamento e de Execução do Componente Básico da Assistência Farmacêutica no Âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2013. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2013/prt1555_30_07_2013.html (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Motta, N.G.; Domingues, K.A.; Colpo, E. Impact of the National Program of Iron Supplementation for children in Santa Maria, RS. Rev. AMRIGS 2010, 54, 393–398. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-685636 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instrutivo da Estratégia de Fortificação da Alimentação Infantil com Micronutrientes em pó-Nutrisus; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2022. Available online: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/instrutivo_nutrisus.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Silva, N.P.; De Oliveira, J.M. Analysis of the NutriSUS public policy implementation in Porto Ferreira, SP. Saúde Soc. São Paulo 2023, 32, e220106pt. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcanjo, F.P.N.; da Costa Rocha, T.C.; Arcanjo, C.P.C.; Santos, P.R. Micronutrient Fortification at Child-Care Centers Reduces Anemia in Young Children. J. Diet. Suppl. 2019, 16, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira-De-Almeida, C.A.; Ued, F.d.V.; Del Ciampo, L.A.; Martinez, E.Z.; Ferraz, I.S.; Contini, A.A.; da Cruz, F.C.S.; Silva, R.F.B.; Nogueira-De-Almeida, M.E.; Lamounier, J.A. Prevalence of childhood anaemia in Brazil: Still a serious health problem: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 6450–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas (PCDT) da Anemia por Deficiência de Ferro–Versão Preliminar; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/conitec/pt-br/midias/consultas/relatorios/2023/relatorio-tecnico-pcdt-anemia-por-deficiencia-de-ferro (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Nota Técnica n° 371/2024, Conitec; Requerimento de Informação n° 3333/2024; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2024. Available online: https://www.camara.leg.br/proposicoesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra?codteor=2822410&filename=Tramitacao-RIC%203333/2024#:~:text=Trata%2Dse%20do%20Requerimento%20de,%C3%9Anico%20de%20Sa%C3%BAde%20(SUS) (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Pantopoulos, K. Oral iron supplementation: New formulations, old questions. Haematologica 2024, 109, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotto, H.Z.W. Iron physiology and metabolism. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2010, 32, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamantziani, T.; Pouliakis, A.; Xanthos, T.; Ekmektzoglu, K.; Paliatsiou, S.; Sokou, R.; Iacovidou, N. The Effect of Oral Iron Supplementation/Fortification on the Gut Microbiota in Infancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assunção, M.C.; Santos, I.S.; Barros, A.J.D.; Gigante, D.P.; Victora, C.G. Flour fortification with iron has no impact on anaemia in urban Brazilian children. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1796–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assunção, M.C.; Santos, I.S.; Barros, A.J.D.; Gigante, D.P.; Victora, C.G. Effect of iron fortification of flour on anemia in preschool children in Pelotas, RS. Rev. Saude Publica 2007, 41, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, M.S.; Mitra, P.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Wheat flour fortification with iron and other micronutrients for reducing anaemia and improving iron status in populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD011302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, A.M.; da Silva, C.V.F.; de Pádua, V.L. Microbial Insights into Biofortified Common Bean Cultivation. Sci 2024, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotto, H.Z.W. Iron metabolism: An overview on the main mechanisms involved in its homeostasis. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2008, 30, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, N.G.A.; Freire, E.M.; Castro, F.A.R.; Cruz, F.O.N.; Costa, G.L.; Souza, J.P.C.; Gomes, L.A.; Motta, M.E.S.; Castro, M.F.R.; Castilhos, V. Iron deficiency in children: Early diagnosis and prevention strategies. Braz. J. Implantol. Health Sci. 2025, 7, 1307–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Micronutrientes. Available online: https://sisaps.saude.gov.br/micronutrientes/nutrisus/relatorio (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Santos, N.G.S.; Florence, T.C.M.; Alves, T.C.H.S. National Iron Supplementation Program in the First Thousand Days of Life in Salvador (BA). Rev. Baiana Saúde Pública 2023, 47, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cembranel, F.; Corso, A.C.T.; González-Chica, D.A. Coverage and adequacy of ferrous sulfate supplementation in the prevention of anemia among children treated at health centers of Florianopolis, Santa Catarina. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2013, 31, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.B.; Baltar, V.T.; Horta, R.L.; Lobato, J.C.P.; Vieira, L.J.E.S.; Gallo, C.O.; Carioca, A.A.F. Food and Nutrition Surveillance System (SISVAN) coverage, nutritional status of older adults and its relationship with social inequalities in Brazil, 2008–2019: An ecological time-series study. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2023, 32, e2022595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofides, A.; Schauer, C.; Zlotkin, S.H. Iron deficiency anemia among children: Addressing a global public health problem within a Canadian context. Paediatr. Child Health 2005, 10, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, S.-R.; Hayes, E.; Kalumba, K.; Biggs, B.-A. Effect of daily iron supplementation on health in children aged 4-23 months: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, e77–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchdev, P.S.; Jefferds, M.E.D.; Ota, E.; Lopes, K.S.; De-Regil, L.M. Home fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders for health and nutrition in children under two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD008959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adish, A.A.; Esrey, S.A.; Gyorkos, T.W.; Jean-Baptiste, J.; Rojhani, A. Effect of consumption of food cooked in iron pots on iron status and growth of young children: A randomised trial. Lancet 1999, 353, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).