The Historical Role of Wormwood and Absinthe in Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Artemisia absinthium, the Plant

4. Artemisia absinthium in the History of Medicine

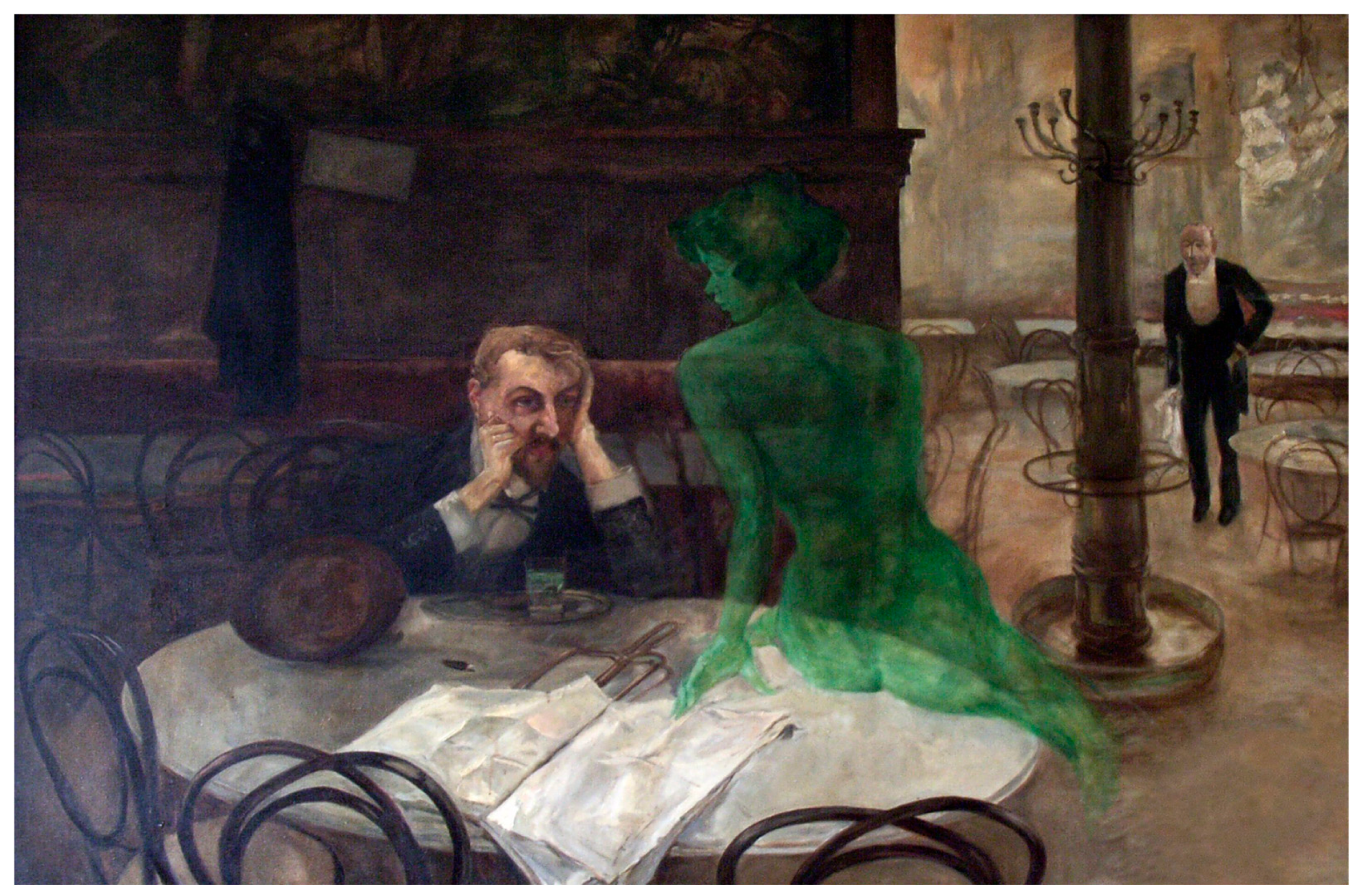

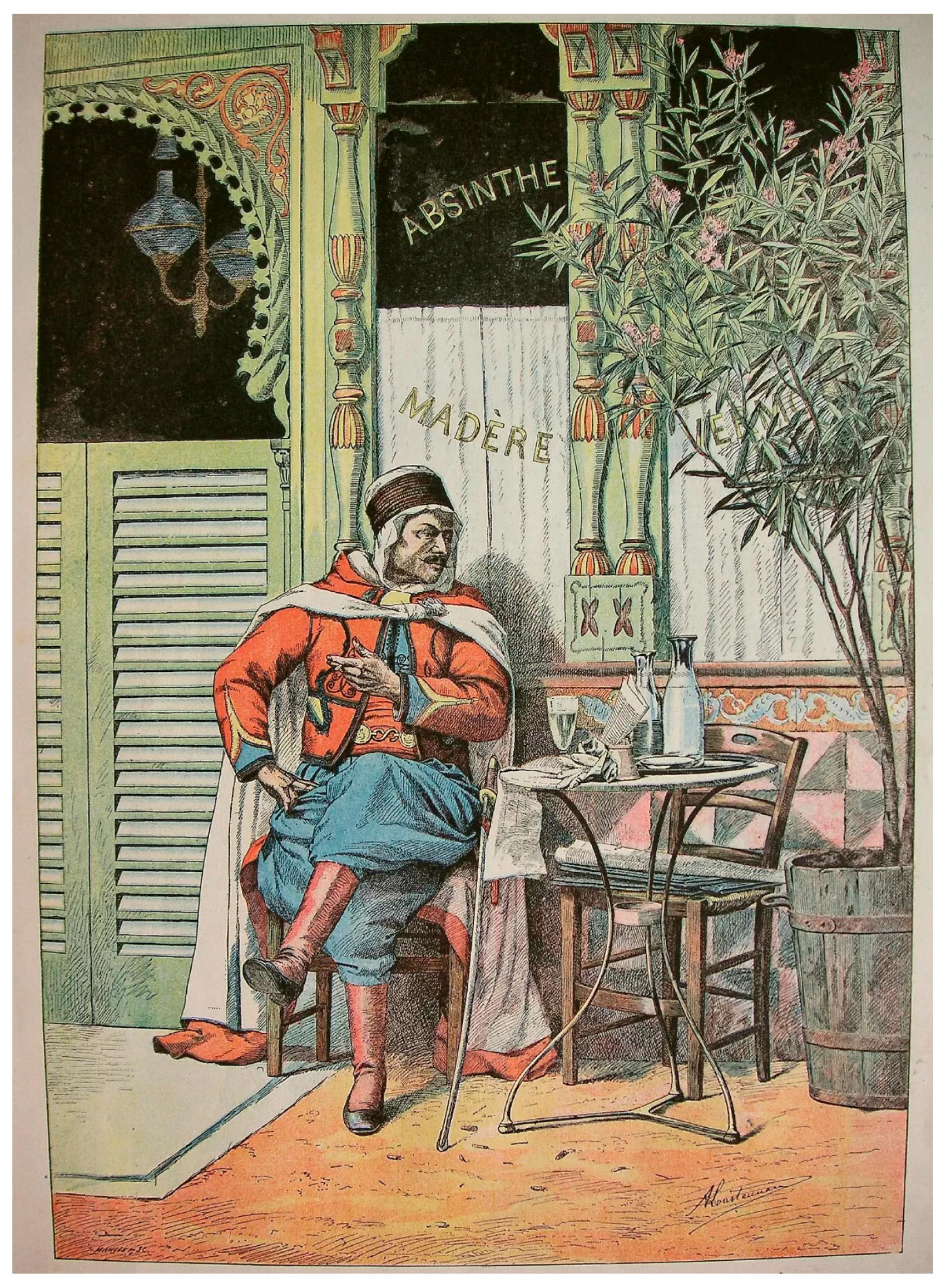

5. Absinthe Invention

6. Absinthe Usage in Medicine

7. Wormwood Antimicrobial Properties and Future Perspectives

| Organism Tested | Extract Type | Dose/Concentration | Key Outcomes/Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemonchus contortus (ovine nematode, studied on sheeps) | Crude aqueous and ethanolic extracts (aerial parts) | In vitro: paralysis/death at 10–80 mg/mL; In vivo: 1.0–2.0 g/kg (oral) | Anthelmintic; as effective as albendazole: Fecal Egg Count Reduction up to 90.46% | [29] |

| Entamoeba histolytica (acute intestinal amoebiasis, human clinical study) | Powdered whole plant (Afsanteen) | 1 g twice daily for 10 days (oral) | Clinical improvement and clearance of E. histolytica in stool; comparable efficacy to metronidazole | [30] |

| Plasmodium falciparum (in vitro) | 80% ethanolic extract (whole plant) | IC50: 1.9 μg/mL (K1, MDR resistant strain); 3.1 μg/mL (3D7, sensitive strain) | Potent antiplasmodial activity; no artemisinin detected in extract | [31] |

| Plasmodium berghei (in vivo, mouse model) | 80% ethanolic extract (whole plant) | 200 mg/kg/day × 4 days (oral) | 94.28% reduction in parasitemia | [31] |

| Staphylococcus aureus (rat surgical wound infection) | Hydroalcoholic extract (topical) | 10% ointment, daily × 7 days | Reduced bacterial load, improved wound healing | [32] |

| Clinical/ATCC (American Type Culture Collection) bacterial isolates (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, S. sonnei, S. aureus, C. perfringens, L. monocytogenes, E. aerogene, K. oxytoca, and P. mirabilis, in vitro) | Essential oil (aerial parts, Serbia) | MIC: <0.08–2.43 mg/mL; MBC: 0.08–38.80 mg/mL | Antibacterial; most active against Staphylococcus spp. | [34] |

| E. coli, S. flexneri, B. subtilis, S. aureus (in vitro) | Essential oil (leaves, Pakistan) | 55–75% inhibition (E. coli, S. flexneri); moderate for B. subtilis, S. aureus | Broad antibacterial activity, especially against Gram-negative | [38] |

| S. epidermidis (in vitro) | Methanol extract (MEAA) | MIC 0.625 mg/mL; MBC 1.25 mg/mL | Antibacterial activity; highly sensitive | [36] |

| S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis (in vitro) | Methanol extract (MEAA) | MIC 1.25–2.5 mg/mL; MBC 2.5–5 mg/mL | Antibacterial activity | [36] |

| Aspergillus spp (in vitro) | Essential oil (leaves, Pakistan) | Up to 70% inhibition | Strong antifungal activity | [38] |

| Penicillium chrysogenum, Aspergillus fumigatus | Essential oil (leaves) | MIC 84 ± 15 µg/mL and 91 ± 13 µg/mL respectively | Growth inhibition | [37] |

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jamshidi-Kia, F.; Lorigooini, Z.; Amini-Khoei, H. Medicinal plants: Past history and future perspective. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafni, A.; Böck, B. Medicinal plants of the Bible—Revisited. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, O.; Contini, C.; Martini, M. The History of Gin and Tonic; the Infectious Disease Specialist Long Drink. When Gin and Tonic Was Not Ordered but Prescribed. Le Infez. Med. 2022, 30, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, C. Doctors and Distillers: The Remarkable Medicinal History of Beer, Wine, Spirits, and Cocktails; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.-Q.; Tong, T. Curcumae Rhizoma: A botanical drug against infectious diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1015098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, P.E. Alcoholic Beverages as the Universal Medicine before Synthetics. In Chemistry’s Role in Food Production and Sustainability: Past and Present; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 1314, pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- There’s a Cure for That: Historic Medicines and Cure-Alls in America. Available online: https://www.ohsu.edu/historical-collections-archives/theres-cure-historic-medicines-and-cure-alls-america (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Szopa, A.; Pajor, J.; Klin, P.; Rzepiela, A.; Elansary, H.O.; Al-Mana, F.A.; Mattar, M.A.; Ekiert, H. Artemisia absinthium L.—Importance in the History of Medicine, the Latest Advances in Phytochemistry and Therapeutical, Cosmetological and Culinary Uses. Plants 2020, 9, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, S. Flora d’Italia; Edagricolae: Bologna, Italy, 2018; Volume 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bordean, M.-E.; Martis, G.S.; Pop, A.; Ungur, R.; Borda, I.M.; Buican, B.-C.; Muste, S. Artemisia Species: Traditional Uses and Importance in Pharmacology. Hop Med. Plants 2022, 30, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment Report on Artemisia absinthium L., Herba. 30 May 2017 EMA/HMPC/751484/2016 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-report/final-assessment-report-artemisia-absinthium-l-herba_en.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Artemisia Absinthium Size, Share, and Growth Report: In-Depth Analysis and Forecast to 2033. Available online: https://www.datainsightsmarket.com/reports/artemisia-absinthium-254234# (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Arnold, W.N. Absinthe. Sci. Am. 1989, 260, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Company of Distillers of London. The Distiller of London, Compiled and Set Forth by the Special Licence and Command of the Kings Most Excellent Majesty: For the Sole Use of the Company of Distillers of London. And by Them to Be Duly Observed and Practized; Richard Bishop: London, UK, 1639. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, D.D. Absinthium: A Nineteenth-Century Drug of Abuse. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1981, 4, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisman, M.; Brug, J.; Mackenbach, J. Absinthe—Is Its History Relevant for Current Public Health? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Walch, S.G.; Padosch, S.A.; Kröner, L.U. Absinthe—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Olatunde, A.; El-Mleeh, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Al-Rejaie, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Zahoor, M.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; Murata, T.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; et al. Bioactive Compounds, Pharmacological Actions, and Pharmacokinetics of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Antibiotics 2020, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Nathan-Maister, D.; Breaux, T.A.; Sohnius, E.-M.; Schoeberl, K.; Kuballa, T. Chemical composition of vintage preban absinthe with special reference to thujone, fenchone, pinocamphone, methanol, copper, and antimony concentrations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3073–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, L.C.; Matulka, R.A.; Burdock, G.A. Naturally Occurring Food Toxins. Toxins 2010, 2, 2289–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, D. Il Giro del Mondo in 80 Alberi; L’ippocampo: Milan, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Studer, N.S. Remembrance of Drinks Past: Wine and Absinthe in Nineteenth-Century French Algeria. In The Politics of Historical Memory and Commemoration in Africa; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, J. The Devil in a Little Green Bottle: A History of Absinthe; Science History Institute: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Studer, N.S. The Green Fairy in the Maghreb: Absinthe, Guilt and Cultural Assimilation in French Colonial Medicine. Maghreb Rev. 2015, 40, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marius, M. Consideration sur l’absenthisme. In Contributions a l’Etude de la Folie; Montpellier Imprimerie Firmin et Cabirou Frères: Montpellier, France, 1880. [Google Scholar]

- Scarfone, M. La Psichiatria Coloniale Italiana: Teorie, Pratiche, Protagonisti, Istituzioni (1906–1952). 2014. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10579/4645 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Ahamad, J.; Mir, S.R.; Amin, S. A Pharmacognostic Review on Artemisia Absinthium. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2019, 10, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, K.A.; Chishti, M.Z.; Ahmad, F.; Shawl, A.S. Anthelmintic activity of extracts of Artemisia absinthium against ovine nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 160, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Siddiqui, M.M.H.; Khan, A.B. Effect of Afsanteen (Artemisia absinthium) in acute intestinal amoebiasis. Hamdard Med. 1997, 40, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ramazani, A.; Sardari, S.; Zakeri, S.; Vaziri, B. In vitro antiplasmodial and phytochemical study of five Artemisia species from Iran and in vivo activity of two species. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 107, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslemi, H.R.; Hoseinzadeh, H.; Badouei, M.A.; Kafshdouzan, K.; Mazaheri Nezhad Fard, R. Antimicrobial Activity of Artemisia Absinthium Against Surgical Wounds Infected by Staphylococcus Aureus in a Rat Model. Indian J. Microbiol. 2012, 52, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikkema, J.; de Bont, J.A.M.; Poolman, B. Interactions of Cyclic Hydrocarbons with Biological Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 8022–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Jovanović, B.; Jović, J.; Ilić, B.; Miladinović, D.; Matejić, J.; Rajković, J.; Dorđević, L.; Cvetković, V.; Zlatković, B. Antimicrobial, Antioxidative, and Insect Repellent Effects of Artemisia Absinthium Essential Oil. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamegos, Y.C.; Kastritis, P.L.; Exarchou, V.; Han, H.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Vervoort, J.; Lewis, K.; Hamblin, M.R.; Tegos, G.P. Antimicrobial and Efflux Pump Inhibitory Activity of Caffeoylquinic Acids from Artemisia Absinthium against Gram-Positive Pathogenic Bacteria. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Nan, T.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L.; Yuan, Y. New Evidence for Artemisia absinthium as an Alternative to Classical Antibiotics: Chemical Analysis of Phenolic Compounds, Screening for Antimicrobial Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.K. Volatile composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Artemisia absinthium growing in Western Ghats region of North West Karnataka, India. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.A. Phytochemical profiling, antioxidant, antimicrobial and cholinesterase inhibitory effects of essential oils isolated from the leaves of Artemisia scoparia and Artemisia absinthium. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordali, S.; Cakir, A.; Mavi, A.; Kilic, H.; Yildirim, A. Screening of chemical composition and antifungal and antioxidant activities of the essential oils from three Turkish Artemisia species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordean, M.-E. Antibacterial and Phytochemical Screening of Artemisia Species. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balciunaitiene, A.; Viskelis, P.; Viskelis, J.; Streimikyte, P.; Liaudanskas, M.; Bartkiene, E.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Zokaityte, E.; Starkute, V.; Ruzauskas, M.; et al. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Extract of Artemisia absinthium L., Humulus lupulus L. and Thymus vulgaris L., Physico-Chemical Characterization, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity. Processes 2021, 9, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, M.; Saki, K.; Shahsavari, S.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Sepahvand, R.; Adineh, A. Identification of medicinal plants effective in infectious diseases in Urmia, northwest of Iran. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, O.; Armocida, E. El Alamein: The battle in the battle. How infectious disease management changed the fate of one of the most important battle of the World War II. Infez. Med. 2020, 28, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Fronzo, A.R.; Misin, A.; Zerbato, V.; Armocida, E.; Donghi, L.; Di Bella, S.; Morgante, G.; Petruzzellis, F.; Toc, D.A.; Simonetti, O. The Historical Role of Wormwood and Absinthe in Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review and Future Perspectives. Sci 2025, 7, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040186

Di Fronzo AR, Misin A, Zerbato V, Armocida E, Donghi L, Di Bella S, Morgante G, Petruzzellis F, Toc DA, Simonetti O. The Historical Role of Wormwood and Absinthe in Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review and Future Perspectives. Sci. 2025; 7(4):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040186

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Fronzo, Anna Rosaria, Andrea Misin, Verena Zerbato, Emanuele Armocida, Lorenzo Donghi, Stefano Di Bella, Ginevra Morgante, Francesco Petruzzellis, Dan Alexandru Toc, and Omar Simonetti. 2025. "The Historical Role of Wormwood and Absinthe in Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review and Future Perspectives" Sci 7, no. 4: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040186

APA StyleDi Fronzo, A. R., Misin, A., Zerbato, V., Armocida, E., Donghi, L., Di Bella, S., Morgante, G., Petruzzellis, F., Toc, D. A., & Simonetti, O. (2025). The Historical Role of Wormwood and Absinthe in Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review and Future Perspectives. Sci, 7(4), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040186