Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming pharmaceutical science by shifting drug delivery research from empirical experimentation toward predictive, data-driven innovation. This review critically examines the integration of AI across formulation design, smart drug delivery systems (DDSs), and sustainable pharmaceutics, emphasizing its role in accelerating development, enhancing personalization, and promoting environmental responsibility. AI techniques—including machine learning, deep learning, Bayesian optimization, reinforcement learning, and digital twins—enable precise prediction of critical quality attributes, generative discovery of excipients, and closed-loop optimization with minimal experimental input. These tools have demonstrated particular value in polymeric and nano-based systems through their ability to model complex behaviors and to design stimuli-responsive DDS capable of real-time therapeutic adaptation. Furthermore, AI facilitates the transition toward green pharmaceutics by supporting biodegradable material selection, energy-efficient process design, and life-cycle optimization, thereby aligning drug delivery strategies with global sustainability goals. However, challenges persist, including limited data availability, lack of model interpretability, regulatory uncertainty, and the high computational cost of AI systems. Addressing these limitations requires the implementation of FAIR data principles, physics-informed modeling, and ethically grounded regulatory frameworks. Overall, AI serves not as a replacement for human expertise but as a transformative enabler, redefining DDS as intelligent, adaptive, and sustainable platforms for future pharmaceutical development. Compared with previous reviews that have considered AI-based formulation design, smart DDS, and green pharmaceutics separately, this article integrates these strands and proposes a dual-framework roadmap that situates current AI-enabled DDS within a structured life-cycle perspective and highlights key translational gaps.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved from an auxiliary analytical tool into a transformative engine for pharmaceutical innovation. In drug delivery research, where the design space encompasses vast and interdependent parameters—drug solubility, excipient compatibility, process variables, and release kinetics—traditional trial-and-error or linear modeling approaches often reach their limits. AI, encompassing machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), Bayesian optimization (BO), and reinforcement learning (RL), provides a data-driven way to capture nonlinear relationships and to predict formulation outcomes that previously required years of empirical work. This computational paradigm shift aligns with the broader movement toward Pharmaceutics 4.0, where digital technologies, automation, and data intelligence converge to accelerate discovery, optimize manufacturing, and personalize therapy [1].

Recent investigations across Southeast Asia (2019–2025) demonstrate that local pharmaceutics research is progressively embracing AI-enabled modeling for formulation optimization and sustainable material design [2,3,4]. These studies explore polymeric and herbal delivery matrices, green nanomaterial synthesis, and predictive algorithms that emulate formulation behavior under limited-data conditions—transforming scarcity into innovation through hybrid experimental–computational strategies. Yet methodological rigor varies; most models remain at the proof-of-concept level, with limited validation and dataset diversity. Collectively, these efforts signify an adaptive diffusion of AI-enabled smart and sustainable drug delivery systems (DDSs), in which intelligent modeling and eco-informed materials converge to expand pharmaceutics beyond major industrial centers toward more inclusive regional participation.

While this review uses Southeast Asian case studies as an initial vantage point, similar trajectories are emerging in North American and European contexts. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Emerging Technology Program has begun to support AI-enabled continuous manufacturing and advanced process-analytical technologies by offering early, science-based dialogue with sponsors [5,6]. In Europe, regulatory discussions around AI in medicines are increasingly shaped by European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidance and by the forthcoming EU Artificial Intelligence Act, which is expected to classify many health-related AI applications as high-risk systems and to require robust data quality, documentation, and human oversight [5,6,7]. Situating regional developments against these global initiatives helps to show that AI-enabled smart and sustainable DDS are not confined to a single geography but are part of a broader international realignment of pharmaceutical innovation [8,9].

Early implementations of AI in pharmaceutics focused on property prediction—estimating solubility, dissolution, stability, and disintegration profiles of candidate formulations. Recent advances, however, have extended beyond predictive analytics toward generative and adaptive design. Deep neural and graph-based architectures now model hierarchical relationships within polymeric and nanoparticulate systems, while Bayesian and RL algorithms enable iterative optimization loops that balance competing design objectives such as potency, viscosity, and shelf stability. In parallel, digital twin frameworks and process-analytical technologies have introduced real-time simulation and feedback control, bridging formulation design with manufacturing intelligence. These developments collectively signal the emergence of AI-enabled formulation ecosystems capable of self-learning and self-correcting performance through continuous data feedback.

Yet, despite the accelerating progress, the field remains constrained by persistent challenges. Formulation datasets are often small, heterogeneous, and biased toward positive results, undermining reproducibility and generalization. Model interpretability and regulatory compliance remain pressing concerns—especially when AI operates as a black box in domains governed by Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and ICH Q8–Q12 guidelines. Moreover, while AI has begun to enable smart and sustainable DDS through predictive modeling of biodegradable and stimuli-responsive materials, its integration within broader ethical and environmental frameworks still lags its technical sophistication. Questions of data transparency, energy consumption, algorithmic fairness, and human oversight underscore the need for responsible innovation to ensure that AI enhances, rather than erodes, scientific rigor and public trust.

Existing reviews and perspective articles have begun to map this territory from different angles. Broadly, three strands can be distinguished. Methodologically oriented reviews focus on AI- and ML-based formulation design and process optimization, emphasizing model classes, data requirements, and performance metrics but paying only limited attention to smart materials or sustainability [8,9,10,11,12]. A second group centers on smart or nano-enabled drug delivery systems, often highlighting stimuli-responsive carriers, biosensor integration, and closed-loop control while treating AI primarily as an enabling analytics layer [13,14,15]. A third, emerging strand explores green and sustainable pharmaceutics, where AI is mentioned mainly in the context of solvent selection, waste minimization, or life-cycle assessment rather than as a unifying design engine [16,17]. Together, these strands illustrate the rapid diversification of AI applications but also reveal that existing literature tends to treat formulation intelligence, smart responsiveness, and sustainability as partially separate agendas.

Despite these advances, a critical integrative gap remains. Few publications explicitly analyze how these strands intersect across the full drug delivery life cycle, and to our knowledge, none has proposed a structured roadmap that explains how AI can simultaneously connect formulation design, real-time adaptive control, and circular-economy principles within a single conceptual frame. Existing reviews typically benchmark algorithms or materials in isolation, with limited discussion of technology-readiness progression, regulatory alignment, or the practical steps required to translate AI-enabled smart and sustainable DDS from proof-of-concept studies to clinically robust systems [5,17,18,19].

Building on and extending these prior contributions, the present review pursues two main objectives. First, it synthesizes the scattered literature on AI in formulation science, smart drug delivery, and sustainable pharmaceutics into a coherent narrative that compares the strengths, limitations, and domain suitability of current approaches across these three domains. Second, it introduces a dual-framework roadmap—a conceptual model and a technology readiness level (TRL) trajectory—that shows how AI can be deliberately embedded into each stage of the DDS life cycle, from computational discovery through smart adaptive delivery to regulatory translation and sustainable deployment. In doing so, the review aims to clarify not only what AI can currently achieve in drug delivery but also how the field can progress toward intelligent, interpretable, and environmentally responsible DDS in practice.

Positioning of this review relative to previous work: Relative to earlier reviews on AI in pharmaceutics and drug delivery, the present article offers three complementary contributions. First, it treats AI-driven formulation design, smart/adaptive DDS, and sustainable/green pharmaceutics as a single coupled design problem rather than as three parallel topics: Section 3 and Section 4 explicitly map how AI methods, stimuli-responsive carriers, and eco-informed materials co-evolve across the DDS life cycle. Second, it formalizes a dual-framework roadmap that couples a life-cycle view of AI adoption in DDS with a staged TRL trajectory, allowing readers to locate current technologies within a staged maturity ladder and to identify which methodological capabilities are needed to advance them. Third, by integrating case studies and examples from both high-resource and emerging research ecosystems, the review reframes recurring data, regulatory, and infrastructural constraints as positive design requirements for future AI-enabled smart and sustainable DDS—an emphasis that is largely absent from previous surveys focused mainly on algorithms, materials, or green metrics in isolation.

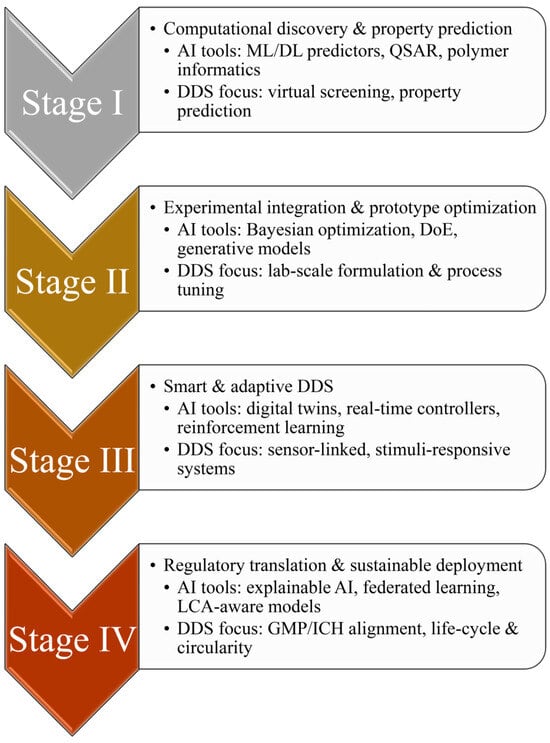

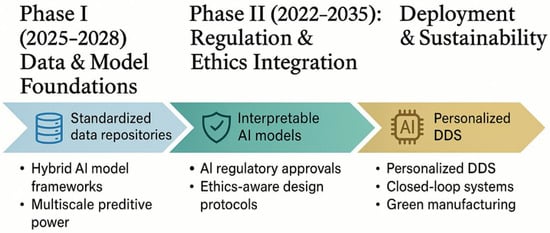

As illustrated in Figure 1, AI adoption in DDS can be viewed as a four-stage trajectory: from computational discovery, through lab-scale optimization and smart adaptive delivery, to regulatory translation and sustainable deployment. This progression emphasizes how AI capabilities expand from virtual screening and property prediction toward experimental integration, real-time control, and life-cycle-aware implementation. The same stage-based logic is used to structure the present review, providing a coherent framework for understanding how AI methods are progressively embedded across the DDS life cycle.

Figure 1.

Four-stage roadmap depicting the progressive integration of AI into DDS, from early computational discovery and property prediction (Stage I) and experimental integration at the lab scale (Stage II) to smart, adaptive DDS (Stage III) and finally to regulatory translation with sustainable real-world deployment (Stage IV). Arrows between stages indicate the sequential advancement of AI-enabled DDS concepts from design to implementation and highlight how AI capabilities broaden across the product life cycle.

1.1. Review Design

The present review uses a narrative approach that is supported by systematic principles. This format was selected because the development of AI-guided drug delivery does not progress through linear clinical endpoints alone, but through ideas, prototypes, and evolving regulatory expectations. A strictly systematic or meta-analytic format would overlook many of these conceptual and technological transitions. Instead, a narrative structure allows us to trace how knowledge in this area has emerged—ranging from early computational prediction to smart material design and sustainability-driven innovation—while still maintaining transparency in how the literature was identified and selected.

This approach acknowledges that AI-enabled formulation science is inherently interdisciplinary: insights arise from computational chemistry, polymer science, bioengineering, regulatory science, and environmental assessment. A flexible narrative format therefore allows these strands to be connected meaningfully, rather than treated as isolated evidence types. In line with good practice for narrative reviews described by Grant and Booth (2009) [20] and Xiao and Watson (2019) [21], the methodological aim was to balance interpretive depth with clear reporting of how the literature base was constructed.

During manuscript preparation, generative AI-based language tools (Grammarly (San Francisco, CA, USA), QuillBot (Chicago, IL, USA), and ChatGPT by OpenAI (San Francisco, CA, USA)) were used solely for grammar refinement and stylistic clarity. They were not used to generate or modify scientific ideas, conduct searches, extract information, or interpret findings. The author is fully responsible for all scientific content presented in this review.

1.2. Literature Search and Study Selection

To ensure transparency, the literature search followed a structured process spanning multiple databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the MDPI repository. Targeted searches in Google Scholar were added to capture gray literature and recent preprints that may not yet be indexed in major databases. The search covered literature published from 2019 to 2025, restricted to English-language articles. The review focused on peer-reviewed original research articles and substantial conference papers, whereas reviews, short commentaries, and editorials were used only to provide contextual background and were not counted as part of the core evidence base.

Search terms were developed around three core themes:

- (1)

- AI and ML: “artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “Bayesian optimization”, “reinforcement learning”;

- (2)

- Drug delivery and formulation: “drug delivery system”, “formulation design”, “polymer informatics”, “microneedle”, “digital twin”;

- (3)

- Sustainability: “sustainable”, “biodegradable”, “green pharmaceutics”, “circular economy”.

Eligibility criteria were defined a priori. Studies were included if they:

- (1)

- Applied AI or machine learning methods to formulation design, polymer or excipient selection, or DDS performance prediction;

- (2)

- Involved smart, stimuli-responsive, or biodegradable biomaterials;

- (3)

- Explicitly addressed aspects of environmental sustainability, life-cycle, or resource efficiency in pharmaceutical systems.

Search terms were adjusted and combined in different ways to broaden or narrow the results, depending on the database and the specificity required. Searches were also iteratively expanded through backward and forward citation tracking to identify foundational studies and recent contributions of high relevance. Eligibility was determined based on thematic and conceptual relevance rather than numerical thresholds, consistent with the interpretive aims of this review. In practice, articles were included when they provided meaningful contributions to one or more of the following thematic clusters:

- (1)

- AI-enabled prediction, optimization, or generative design of formulations or polymers;

- (2)

- Integration of AI with smart biomaterials, including stimuli-responsive, biodegradable, or adaptive systems;

- (3)

- Sustainability-oriented considerations such as life-cycle assessment, resource efficiency, or eco-informed material selection;

- (4)

- Regulatory, ethical, or data-governance implications related to ICH Q8–Q12 or quality by design (QbD) approaches in AI-enabled systems.

Studies were excluded if they lacked a substantive AI component, were unrelated to drug delivery or formulation science, or focused exclusively on drug discovery without downstream DDS relevance. Editorials and opinion pieces without empirical contribution were also excluded. Non-English publications, papers without accessible full text, and duplicate reports of the same study were excluded from the review.

In total, 180 records were identified across all sources; after removing duplicates, 160 unique records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 40 were excluded as clearly unrelated to AI-enabled DDS or sustainability, leaving 120 full-text articles for detailed assessment. Following full-text screening, 92 studies were retained for in-depth narrative synthesis. The identification, screening, and inclusion process is summarized in a PRISMA-style table (Table 1, Table S1).

Table 1.

PRISMA-style summary of database search and study selection.

The full-text review allowed assessment of methodological soundness, technological maturity, and translational relevance. Consistent with the narrative review guidance from Grant and Booth (2009) [20] and Xiao and Watson (2019) [21], synthesis proceeded through conceptual clustering, critical appraisal, and integrative interpretation rather than quantitative filtering. This process made it possible to link predictive modeling, material design, adaptive control, manufacturing intelligence, and environmental stewardship into a coherent framework that reflects how AI is transforming pharmaceutical development.

2. The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutics

AI has evolved from a peripheral computational tool into a core driver of pharmaceutical innovation. The logic is clear: modern formulation and delivery research deals with a vast parameter space—drug solubility, excipient compatibility, process variables, and kinetic behavior—that defeats linear intuition. ML models can map these nonlinearities and shorten discovery cycles that once required years of empirical testing. As Bannigan et al. (2021) demonstrated, supervised algorithms can already predict disintegration time and dissolution profiles with accuracy exceeding classical regression approaches [10]. This shift marks the opening chapter of what commentators now call Pharmaceutics 4.0, a data-centric era where experimentation and computation reinforce each other.

Early applications focused on single-output prediction—solubility, viscosity, or drug release from polymer matrices. The review by Bao et al. (2023) synthesized more than 80 studies and showed how random-forest and support-vector-machine models improve formulation screening while reducing material waste [11]. Progress since 2020 has expanded into multi-objective optimization. Narayanan et al. (2021) used BO to design stable antibody formulations, reaching the target melting temperature with only 33 experiments—ten-fold fewer than a conventional factorial design [12]. Later work by Li et al. (2025) extended the same framework to vaccine adjuvant systems, confirming that active-learning loops can navigate competing goals of potency, viscosity, and shelf stability [22]. Such examples illustrate how Bayesian and RL strategies transform formulation science from static screening into closed-loop discovery.

DL broadened the representational frontier. Convolutional neural networks now analyze micro- and nano-structural images to correlate particle morphology with release kinetics, while graph neural network (GCN) models interactions among polymers, surfactants, and active compounds. Generative architectures—variational autoencoders (VAEs) and diffusion models—can even propose excipient combinations that meet pre-specified biopharmaceutical targets. Wu et al. (2025) reviewed these methods and highlighted cases where generative models yielded novel nanoparticle formulations later validated experimentally [9]. Likewise, Dong et al. (2024) described an AI-powered web platform that integrates descriptor databases with predictive algorithms to guide bench scientists in real time [23]. The momentum of these studies confirms a genuine methodological revolution rather than a transient computational fad.

Parallel to algorithmic progress, digital twin technology has emerged as AI’s operational companion. A digital twin is a dynamic, virtual counterpart of a physical process that updates continuously through sensor and process analytical technology (PAT) data. Kirby et al. (2024) detail how digital twins are being adopted for continuous manufacturing, enabling real-time adjustment of mixing, drying, or coating parameters [24]. Fischer et al. (2024) expanded the concept to patient twins that simulate physiological variability for personalized dosing [25]. By coupling AI-enabled parameter estimation with mechanistic process models, these systems close the loop between design, manufacture, and clinical performance—an aspiration long held by formulation scientists.

However, enthusiasm for AI must be tempered by realistic appraisal. The first constraint is data quality and representativeness. Formulation datasets are typically small, heterogeneous, and skewed toward successful prototypes; negative results remain under-reported. Noorain et al. (2023) noted that fewer than 20% of surveyed ML studies provided external validation or public data access, hampering reproducibility [26]. Without transparent benchmarks, claimed accuracy can be illusory. The second issue is interpretability. Deep neural networks (DNNs) excel at prediction yet rarely explain causal relationships—problematic for a discipline anchored in physicochemical reasoning. Regulatory agencies, guided by principles of GMP, demand traceable logic for every process parameter. Schmidt et al. (2025) argue that digital twin and AI deployments must include model-lifecycle governance and explainable layers to be auditable [27]. The third challenge is infrastructural: few laboratories possess integrated data pipelines linking formulation databases, sensors, and cloud computation securely enough for continuous operation.

Ethical and sustainability dimensions also warrant discussion. Large-scale model training consumes substantial energy; the irony of using energy-intensive computation to promote green pharmaceutics cannot be ignored. Moreover, excessive automation may de-skill younger scientists, replacing experiential insight with algorithmic dependence. Commentaries such as Sridhar et al. (2025) on AI-enabled phytoconstituent nanocarriers remind us that human interpretation remains essential to validate biologically plausible predictions [28]. The consensus forming across reviews is that AI should serve as augmented intelligence—a collaborator amplifying, not displacing, human expertise.

Viewed holistically, the infusion of AI into pharmaceutics signifies a deeper change in scientific understanding. Classical formulation science advanced through sequential hypothesis testing; AI introduces iterative, data-centric learning that continuously updates understanding of structure–property–performance linkages. When combined with mechanistic theory, this yields hybrid physics-informed models that respect conservation laws while adapting from data. Digital twins extend the paradigm by embedding these models within feedback-controlled manufacturing, enabling predictive quality assurance rather than retrospective correction. Such coupling embodies the philosophy of quality by prediction—a natural evolution from QbD.

To capitalize on this transformation, the community must build interoperable and findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable (FAIR) data infrastructures that capture both successes and failures, adopt explainable or hybrid model architectures, and train a workforce fluent in data science and pharmaceutics alike. Cross-sector consortia—linking academia, industry, and regulators—can accelerate the establishment of shared validation datasets and standard protocols. If these cultural and technical foundations are laid, AI can indeed shape the next generation of DDS: designs that are data-rich yet physically grounded, efficient yet sustainable, and algorithmically precise yet human-interpretable. The trajectory suggests not replacement but co-creation—scientists and algorithms learning together to deliver smarter, cleaner, and more personalized therapeutics.

3. AI-Enabled Innovation in Formulation Design and Optimization

3.1. Summary of the Landscape

In the evolving domain of pharmaceutical development, AI (encompassing ML, DL, BO, and RL) is rapidly gaining traction as a tool to accelerate and refine formulation design. Rather than relying solely on trial-and-error experimentation, AI methods enable in silico exploration of high-dimensional formulation spaces, prediction of property–structure relationships, and automated optimization loops. Recent comprehensive reviews outline how AI is being integrated across the pharmaceutical pipeline, from drug discovery to dosage form design and process optimization [8,9].

Within the specific subfield of formulation and DDS, the promise lies in three key capabilities:

- (1)

- Property prediction: Given candidate drugs, polymers, and excipients, AI models aim to predict critical performance metrics (e.g., release kinetics, stability, solubility, mechanical strength).

- (2)

- Generative/inverse design: AI may propose new molecular structures or formulations that meet user-specified targets (e.g., maximize release over 24 h while maintaining stability at 37 °C).

- (3)

- Optimization and adaptive design: Through techniques like BO or RL, AI supports automated iteration—choosing formulations to test next based on predicted gains.

Leading-edge platforms already begin to embody these ideas (e.g., a web-based platform for formulation design) that integrate data ingestion, prediction engines, and formulation suggestions [23]. In parallel, polymer informatics—learning structure–property maps for polymers—has matured as a supporting discipline [29,30]. The junction of polymer informatics and AI-driven formulation design is where many challenges and opportunities lie.

Thus, the heart of modern AI-enabled formulation is to close the “design → test → learn → redesign” loop more quickly and reliably than what traditional design of experiments (DoE) approaches permit.

3.2. Analysis of Key Methods and Their Applications

In practice, AI in formulation design and DDS tends to revolve around three core computational tasks: property prediction, generative or inverse design, and optimization or adaptive control. Rather than treating model classes in isolation, it is more useful to view them as parts of a single workflow. Property predictors estimate how a candidate formulation or material is likely to behave; generative models propose new candidates that might satisfy a target profile; and optimization or RL schemes decide which experiments or parameter sets should be tested next. Together, these components form a loop in which data, models, and experiments continually inform one another.

The following subsections briefly summarize how different model families are used within each of these tasks and how they connect to real-world formulation and DDS applications.

3.2.1. Property Prediction: Models, Representations, and Use Cases

A recurring difficulty in AI-driven formulation design is how to represent drugs, polymers, and excipients in a way that is both machine-readable and chemically meaningful. For small molecules, this is often addressed using standard descriptors—molecular weight, log P, topological polar surface area (TPSA), hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, molecular fingerprints, or graph-based encodings. For polymers and excipients, the challenge is more severe: chain length, crosslinking density, monomer ratios, architecture (linear versus branched), and polydispersity all influence performance and must somehow be encoded. Polymer-informatics work has therefore explored specialized representations such as BigSMILES, sequence-based embeddings, and GCNs tailored for macromolecular structures [29,30]. Several reviews have emphasized that data curation, representation choice, and the mapping from microstructure to macroscale performance remain key bottlenecks for reliable prediction [30,31].

On top of these representations, a range of model families are used. Tree-based ensembles such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM are common in moderate-sized datasets because they tolerate heterogeneous features and experimental noise and still provide reasonably interpretable variable-importance patterns. When data volumes increase, and relationships become highly nonlinear, DNNs are often used. However, they require careful regularization to avoid overfitting. More recently, GCNs have become attractive for molecular and polymer systems because they operate directly on node–edge structures rather than on pre-computed descriptors, and multi-task learning frameworks can predict several formulation-relevant properties simultaneously, sharing information across tasks.

These modeling choices are not abstract; they already underpin real formulation workflows. Kehrein et al. introduced POxLoad, an ML tool that predicts drug loading in poly(2-oxazoline) micellar carriers, allowing formulators to narrow down experiments to the most promising candidates [32]. In polymer research more broadly, ensemble models and other ML regressors have been used to predict mechanical, thermal, and solution behavior from composition and structural descriptors, helping to screen excipients and polymer backbones before synthesis [29,30]. Within formulation science, AI models have been applied to tablets, lipid-based systems, and nanotechnology-based carriers, frequently outperforming classical regression or response-surface methodology in multi-objective settings where several performance criteria must be balanced simultaneously [8,33]. A web-based platform described by Dong et al. integrates these predictive engines into a practical interface that allows bench scientists to upload data, obtain property predictions, and receive candidate formulation suggestions in near real time [23].

These instances illustrate how property prediction is foundational to the rest of the workflow: if predictions are poor, subsequent generative or optimization steps can be misled.

3.2.2. Generative and Inverse Design Approaches

Once reasonably robust predictive models are available, attention naturally shifts from predicting formulation performance to inverse design, that is, identifying which formulations should be created to achieve a specified target. Generative and inverse-design models attempt to answer this by proposing new candidates that are likely to satisfy user-defined constraints.

VAEs and generative adversarial networks (GANs) learn latent spaces of molecules or polymer structures and can sample new points within these spaces. In drug discovery, such architectures have been widely used to suggest small molecules with desired properties or bioactivity profiles. Conditional generative models extend the idea by biasing the generator toward meeting specific targets—such as a desired release rate, stability window, or mechanical strength—so that the sampled candidates are not only novel but also tailored to the problem at hand. RL formulations of design go a step further by casting the construction of a molecule or polymer as a sequence of decisions: the agent adds monomers, adjusts ratios, or modifies processing parameters and receives rewards based on predicted performance. BO in latent space offers another variant, treating the learned embedding of candidates as the search domain and using a surrogate model plus acquisition function to locate promising regions efficiently [34,35].

So far, most of the convincing success stories for these methods come from materials science outside classical pharmaceutics, where generative models have proposed new polymers with tuned mechanical or thermal properties that were later synthesized and validated experimentally. In DDS, progress has been slower. The mapping from composition and microstructure to drug release or stability is highly complex and strongly influenced by processing conditions and internal morphology, making it harder to learn a stable generative mapping. Achieving controllability—reliably generating candidates that satisfy several constraints at once—is non-trivial, and there is always a risk that the model suggests chemically invalid or synthetically infeasible structures. In practice, generative pipelines therefore require post-filtering or constrained generation steps, and they depend heavily on the quality of the underlying predictive models and representations.

As a result, generative and inverse-design approaches currently sit at the “high-potential but high-risk” frontier: they offer the possibility of leaping beyond incremental trial-and-error, but they remain sensitive to data limitations, representation choices, and domain constraints, especially in complex DDS settings.

3.2.3. Optimization and Adaptive Design via BO and RL

Even when promising candidates or parameterized formulation spaces are available—whether from human expertise, property predictors, or generative models—experimental validation remains expensive. Optimization and adaptive design methods aim to decide which experiments to run next so that information is gained as efficiently as possible.

BO addresses this by building a surrogate model over formulation parameters (for example, polymer ratios, excipient levels, or processing temperatures) and an objective function such as deviation from a target release profile or stability specification. An acquisition function then balances exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of promising ones, guiding the selection of new experimental points. In formulation science, such BO loops have been combined with ML surrogates to tune complex biopharmaceutical formulations, reducing the number of necessary experiments while still reaching multi-parameter targets [8,12]. This makes BO particularly attractive in situations where each experiment is costly in time, material, or analytical effort.

RL offers a complementary perspective for problems that are naturally sequential. Here, each adjustment to a formulation or process parameter is treated as an action, and the sequence of actions forms a trajectory whose cumulative reward depends on eventual performance (for example, long-term stability or in vitro release). RL is therefore conceptually well suited to multi-step fabrication processes or adaptive control schemes in which decisions at one stage affect options later. However, training RL agents in realistic formulation settings is challenging. Sample efficiency, reward design, and exploration strategies all become critical, and purely simulation-based training risks overfitting to an idealized virtual environment [8].

Hybrid strategies are beginning to emerge that combine BO, RL, and surrogate modeling into flexible design loops—for instance, using BO for broad exploration of the formulation space and then switching to RL or local search for fine-tuning once a promising region has been identified. Across all these approaches, practical considerations remain important. The dimensionality of the design space influences how quickly an algorithm can learn; experimental noise can mislead optimization; and if the surrogate is inaccurate early in the process, the algorithm may converge to local optima or select unstable or unrealistic formulations. Nevertheless, when carefully implemented, optimization and adaptive design methods can turn AI from a passive predictor into an active partner in experimental planning, closing the loop between computation and the bench.

3.3. Critique: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Gaps

No approach is without limitations, and the current landscape of AI-driven formulation design reflects a mix of clear strengths and equally clear weaknesses [36]. On the positive side, AI methods have already shown that they can screen large design spaces in silico and substantially cut down the number of physical experiments required. Property-prediction models support rapid pre-screening of excipients, polymers, and dosage-form variants; optimization loops help navigate multi-objective trade-offs between release profile, stability, manufacturability, and cost; and both generative and adaptive strategies make it possible to explore non-intuitive regions of the design space that would be unlikely to emerge from manual trial-and-error alone. When these components are combined thoughtfully, they create iterative “design–test–learn–redesign” cycles that are far more efficient than traditional one-factor-at-a-time experimentation.

At the same time, several recurring limitations temper this promise. Many formulation subdomains—especially novel polymer classes, niche DDS, or sustainability-oriented systems—suffer from sparse, heterogeneous, and biased datasets. The familiar “garbage in, garbage out” problem is therefore acute: models trained on narrow or non-representative data may fail badly when applied to new chemistries or process conditions. Representation remains another key bottleneck. Finding descriptors that capture the relevant physics of polymers, excipients, and processing steps is challenging, and even sophisticated graph-based encodings cannot fully compensate for missing or noisy experimental data. DL and generative models amplify these concerns because, while powerful, they often behave as black boxes. Understanding why a given formulation is predicted to succeed is difficult, which complicates trust, knowledge transfer, and regulatory acceptance. There is also a practical gap between virtual design and real-world feasibility: some algorithmically proposed structures or parameter sets may be synthetically infeasible, too expensive to manufacture, or incompatible with existing equipment and GMP constraints.

Looking across published work, a number of gaps and underexplored areas also become apparent. Much AI research still focuses on static properties; realistic, time-dependent dissolution and release behavior under physiological conditions is modeled less frequently, even though it is central to DDS performance. Process parameters—mixing protocols, temperature profiles, drying or coating conditions—are often treated as secondary variables, despite their dominant influence on final product quality. Methods for interpretability and explainable AI are only beginning to be integrated into formulation workflows, leaving many high-performing models opaque. Transfer learning and domain-adaptation techniques that could help reuse models across dosage forms or related formulation spaces are still in their infancy. Finally, although the concept of fully autonomous, closed-loop experimentation is widely discussed, only a handful of laboratories appear to have the automation, data infrastructure, and validation procedures needed to realize such pipelines in practice.

Overall, the critique is therefore not that AI lacks potential, but that its deployment in formulation science is uneven. Data quality, representation, interpretability, regulatory readiness, and infrastructural maturity all act as rate-limiting factors. Addressing these issues will be essential if AI is to move from isolated success stories toward reliable, widely adopted tools for designing the next generation of smart and sustainable DDS.

3.4. Integrative Synthesis and Forward Outlook

Drawing together the summary, analysis, and critique, it becomes evident that AI-enabled design in formulation science holds transformative potential, although its practical implementation is far from trivial. The most promising architecture is a hybrid pipeline:

- (1)

- Curated dataset and representation engineering;

- (2)

- Robust property prediction models (surrogate models);

- (3)

- Generative/candidate proposal (VAE/RL/conditional models);

- (4)

- Optimization loop (BO/RL) constrained by domain feasibility;

- (5)

- Experimental validation and feedback → model update.

In practice, success depends heavily on steps 1 and 2: without good data and representation, everything downstream stumbles. In that way, the evolution of polymer informatics, data sharing (FAIR principles), and experimental standardization becomes foundational [30].

A second technical priority in this hybrid pipeline is rigorous management of model extrapolation. Most formulation models summarized in this review are calibrated on relatively narrow chemical or process domains, yet are often applied to new active pharmaceutical ingredients, excipient classes, or manufacturing scales [10,36,37]. To mitigate this risk, practical workflows should include explicit estimation of a model’s domain of applicability based on leverage statistics or distance metrics in descriptor space, coupled with uncertainty-aware prediction schemes that flag low-confidence outputs or abstain when a query lies outside the validated region [12,36]. Active-learning strategies can then be used to select additional experiments near these domain boundaries, incrementally expanding the reliable operating space with minimal experimental burden [12,22]. At the same time, systematic external validation across dosage forms and scales, and transparent reporting of the model’s intended use domain, are essential to avoid over-interpretation of nominally high-accuracy models that have only been tested within constrained laboratory settings [36,37,38].

Moreover, techniques like transfer learning (leveraging models across related formulation spaces) and meta-learning (learning how to learn new formulation tasks faster) may help bridge gaps in data-sparse domains. Interpretable AI techniques or mechanism-guided AI (hybrid physics + ML) can help reduce black-box risk.

In the nearer term, partial adoption is likely: AI will augment human formulators, suggesting candidate spaces or parameter ranges, rather than fully replacing expert judgment. Over time, as infrastructure (data, lab automation) improves, more fully autonomous loops may emerge.

One possible concrete milestone is the integration of AI within QbD and PAT frameworks, where AI models help monitor and adjust in real time during manufacturing [36].

In summary, AI-enabled innovation in formulation design is not a panacea—but it offers a new paradigm: a design-centric, feedback-rich, data-driven approach that increasingly merges computation and experimentation. The maturation of data resources, model robustness, interpretability, and lab–AI integration will determine how fast and how deeply this paradigm transforms pharmaceutical development.

3.5. Case Studies and Comparative Evaluation of AI Models in Formulation Science

3.5.1. Summary of Representative Case Studies

Real-world studies demonstrate how AI has shifted from theoretical promise to experimental utility in formulation science. Early works centered on property prediction; later ones integrate optimization and generative design. Key exemplars are summarized below.

Table 2 presents the practical applications of AI and ML models in pharmaceutical formulation and DDS. The table consolidates peer-reviewed case studies in which AI was explicitly implemented to design, predict, or optimize formulation parameters within real experimental settings. Each entry delineates the dosage-form system, algorithmic approach, performance metric, and the corresponding original publication for verification. Collectively, these cases depict a chronological progression of AI integration—from predictive modeling of drug-release kinetics [39] and BO of biopharmaceutical formulations [12] to platform-level implementations such as FormulationAI [23].

Taken together, the R2 and mean absolute error (MAE) values in Table 2 illustrate that reported accuracy must be interpreted in light of data regime and problem structure. For instance, gradient-boosted trees achieved R2 ≈ 0.92 for predicting fractional release in long-acting injectables [39], a level of performance that is difficult to obtain with linear models when nonlinear interactions between polymer composition and processing history dominate release behavior. In contrast, studies using smaller or more homogeneous datasets often report similarly high R2 values even for simpler models, suggesting that apparent accuracy in narrow domains may not translate to broader formulation spaces.

Moreover, several high-performing models rely on internal cross-validation or random train–test splits within a single dataset. Under such conditions, MAE or R2 can overestimate real-world performance if covariate shift or batch effects are present. A critical reading of these studies therefore emphasizes not only the magnitude of the reported metrics, but also the validation strategy, sample size, and descriptor quality.

From an analytical standpoint, the pattern underscores the adaptive maturity of AI in formulation science. Early works relied on ensemble-learning frameworks (Random Forest, XGBoost), which offered interpretability and stability with limited datasets—a characteristic well-suited to the data-scarce environment typical of pharmaceutical laboratories. In contrast, more recent efforts employ deep neural and graph-based models (CNN, GCN) to capture nonlinear molecular interactions and the spatial architecture of polymeric networks or microneedle arrays. The incorporation of Bayesian and RL loops signifies a paradigm shift from static prediction toward iterative, closed-loop optimization—a movement aligning pharmaceutical R&D with the principles of autonomous experimental design and self-driving laboratories.

From a critical perspective, however, several limitations remain evident. Many of the published models demonstrate impressive accuracy within narrow experimental boundaries but lack external validation across formulation types or manufacturing scales. Datasets remain fragmented, heterogeneous, and often proprietary, hindering model generalization and reproducibility. Moreover, AI applications are frequently constrained to post hoc prediction rather than a priori mechanistic understanding—raising questions about explainability and regulatory acceptance under frameworks such as ICH Q8 and Q12. Without transparent model interpretability, the translation from computational optimization to GMP-compliant production remains uncertain.

Synthesizing across these insights, the trajectory revealed by Table 2 points toward a hybrid paradigm—one that couples interpretable ensemble baselines with data-hungry deep or graph architectures as information richness increases. Such integration may yield models that are not only predictive but also mechanistically insightful, bridging the gap between empirical formulation design and theory-driven pharmaceutical engineering. Ultimately, the empirical evidence summarized in Table 2 substantiates AI’s growing legitimacy within formulation science while simultaneously exposing the methodological and infrastructural gaps that must be addressed for full-scale industrial adoption. The next frontier lies in integrating these AI capabilities with smart and sustainable DDS, where material intelligence and environmental responsibility intersect. These observations directly motivate the comparative synthesis in Table 3.

These studies collectively reveal a steady methodological gradient—from interpretable ensemble learners toward data-intensive, representation-rich deep models.

3.5.2. Analysis of Model Performance and Domain Suitability

Performance outcomes depend strongly on data scale, representation, and domain complexity. Tree-based methods remain the pragmatic workhorse for small-to-medium datasets (<104 samples), while graph and neural models excel only with larger, chemically diverse datasets.

In practical terms, the comparative R2 and MAE values reported in Table 2 show that no single algorithm is universally optimal. Tree-based ensembles (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) tend to outperform linear baselines when the formulation space is moderately sized but highly nonlinear, with complex interactions between excipient type, processing parameters, and environmental conditions. Under these data conditions, their built-in feature bagging and nonparametric splits allow them to capture higher-order effects without strong assumptions about the underlying structure of the data.

By contrast, graph-based and DL architectures only begin to outperform ensemble baselines when three conditions are met: (i) sufficiently large and chemically diverse datasets, (ii) informative structural or sequence-level representations (e.g., polymer graphs, 3D conformers), and (iii) careful regularization to avoid overfitting. Studies that reported the highest R2 values for polymer property prediction [39,40,41,42] relied on rich molecular representations and thousands of labeled samples; when these conditions were not satisfied, deep models often matched but did not clearly exceed the MAE achieved by simpler ensembles.

Quality of descriptors—particularly for polymers and excipients—remains the single largest determinant of model success. Studies combining physicochemical descriptors + processing parameters reported ≈ 10% lower RMSE than those relying on chemical descriptors alone.

Table 2.

Representative AI applications in formulation design.

Table 2.

Representative AI applications in formulation design.

| System/Application | AI Model/Algorithm | Main Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric long-acting injectables: predicting release and guiding design | Gradient-boosted trees (incl. LGBM), RF, XGBoost | Learned to predict fractional drug release; models used to guide new LAI design; LGBM predicted fractional drug release with R2 ≈ 0.92 (3783 data pts) | [39] |

| Poly(2-oxazoline) micellar formulation | ML ensemble (PoxLoad tool) | Predicted drug-loading capacity → cut experiments by > 50% | [32] |

| Biopharmaceutical formulation (proteins): adaptive tuning | BO + ML surrogate | Cut experimental runs by ~40% while optimizing multi-parametric formulations | [12] |

| Polymer thermal/mechanical property prediction | Random forest regressor | MAE < 5% for tensile strength | [41] |

| Polymer informatics for copolymer design | GCN | Accurate prediction of bulk modulus and thermal expansion | [40] |

| Cross-modal formulation design platform | Multi-algorithm platform (prediction + candidate suggestion) | Web-based FormulationAI integrates datasets and models for 16+ formulation properties | [23] |

| In vitro prediction for OFDF, SR matrix tablets | DL vs. classical ML | DNNs outperformed six ML baselines in predicting formulation properties | [10] |

| Polymer/copolymer property prediction for excipient/polymer selection | GCN | Accurate prediction of polymer thermal/mechanical properties; interpretable trends | [42] |

| Microneedle design for interstitial fluid collection | FEM-augmented ML (MLR, RF, SVR, NN) | Optimized microneedle geometry to maximize collected fluid | [43] |

| Microneedle design (rapid online tuning) | Bayesian ML optimization (with user-bounded parameters) | Online method proposes optimal microneedle geometry within bounds | [44] |

| Dynamic dissolution profiles and kinetic parameters (tablets) | Random Forest/ML ensemble | ML predicts full release profiles and kinetic parameters | [37] |

Abbreviations: AI, artificial intelligence; ML, machine learning; DL, deep learning; BO, Bayesian optimization; FEM, finite element method; GCN, graph convolutional network; LAI, long-acting injectable; LGBM, Light Gradient Boosting Machine; MAE, mean absolute error; MLR, multiple linear regression; DNN, deep neural network; OFDF, oral fast dissolving film; R2, coefficient of determination; RF, random forest; SR, sustained release; SVR, support vector regression.

Table 3.

Comparative performance of AI models across formulation domains.

Table 3.

Comparative performance of AI models across formulation domains.

| AI/ML Model | Application Domain | Input Representation/Feature Type | Performance Metric(s) | Advantages/Observed Strength | Limitations/Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest, Gradient Boosting | Prediction of polymer physical/thermal properties | Descriptors/fingerprint vectors (e.g., ECFP, SMILES-based features) | R2 ≈ 0.88 (melting temperature), glass transition etc. | Robust on moderate data, interpretable feature importance | Performance depends heavily on feature engineering; may not generalize to novel chemistries | [41] |

| Transformer/Language-model based (TransPolymer) | Polymer property prediction | Polymer SMILES/sequence tokenization | Outperformed baseline models on multiple polymer property benchmarks | Learns representations end-to-end, less need for hand-crafted features | Requires large pretraining datasets; possible domain shift issues | [45] |

| Multimodal/hybrid models (e.g., combining 1D + 3D) | Polymer property prediction | Sequential + structural/3D-derived features | State-of-the-art in benchmark tasks (multi-property) | Better captures multi-scale structure information | 3D structural data is often sparse or expensive to compute | [46] |

| Descriptor-based ML vs. deep/GNN in formulation review context | Formulation/dosage form prediction/optimization | Molecular descriptors, process parameters, excipient descriptors | Reported in reviews: improved accuracy, lower error vs. classical techniques | Easy to implement, interpretable, often first-line model | Reviews note data scarcity, overfitting risks, reproducibility issues | [38] |

| Descriptor/DL hybrid in polymer research | Polymer property prediction | Fingerprint + deep architectures | Better performance than descriptor-only in benchmarks | Learns hierarchical features, can capture nonlinear dependencies | More data required, more hyperparameter tuning | [47] |

| Review-level comparative summary | Polymer composites/polymers | Varies across studies | Summarizes accuracy, strengths, limitations across ML methods | Aggregates empirical comparisons, highlights domain gaps | Does not always provide standardized metrics | [48] |

Abbreviations: AI, artificial intelligence; ML, machine learning; DL, deep learning; ECFP, extended-connectivity fingerprint; SMILES, simplified molecular-input line-entry system; GNN, graph neural network; R2, coefficient of determination.

3.5.3. Integrative Appraisal of AI Models

Table 3 presents a comparative view of artificial-intelligence and ML model classes as they are applied across polymer science, materials informatics, and pharmaceutical formulation design. It synthesizes verified comparative and benchmark studies that evaluate how different model families perform, how they represent complex data, and what inherent limitations they face. By organizing these studies side by side, the table provides more than a simple ranking—it maps how algorithmic thinking has evolved in formulation science, revealing a gradual transition from interpretable, rule-driven models toward architectures capable of learning hierarchical and spatial relationships in molecular systems.

Tree-based ensembles such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting continue to demonstrate remarkable resilience in data-limited environments, where interpretability and reproducibility remain paramount. Their structured decision paths offer not only predictive stability but also insight into variable importance—a feature often valued by experimental scientists. In contrast, more recent research embraces deep-learning and graph-based architectures—notably CNNs, GCNs, and Transformers—that can encode molecular topology, polymer connectivity, or reaction pathways in ways that mirror physical chemistry itself. Multimodal frameworks such as MMPolymer exemplify this evolution: by fusing 1-D descriptors with 3-D structural embeddings, they capture multi-scale patterns linking composition to macroscopic performance. The movement here is clear—from models that interpret data, to systems that internalize the physics behind it.

However, higher predictive performance does not come without trade-offs. Tree-based ensembles, while robust and relatively interpretable, can struggle to extrapolate beyond the chemical and process space spanned by the training data, and their decision paths may still be opaque to non-technical stakeholders. Deep neural and graph models, in turn, offer richer representations but are far more sensitive to data imbalance, noise, and hyperparameter choices; in several studies, small changes in training protocol led to materially different MAE or R2 values. These observations underline that “better-performing” algorithms in Table 2 and Table 3 are not inherently superior, but rather conditionally advantageous given specific data regimes and design objectives.

Yet, despite these advances, several critical gaps persist. Comparative reviews consistently report that data sparsity and inconsistency undermine model reliability; most published datasets are small, proprietary, or poorly standardized. Benchmark metrics also vary widely, making it difficult to assess progress across studies or domains. Even high-performing neural models often excel only within narrow experimental boundaries, lacking external validation or scalability beyond laboratory settings. This fragmentation limits the field’s ability to establish generalizable knowledge. Moreover, the interpretability crisis of deep architectures remains unresolved—a point of tension when regulatory frameworks such as ICH Q8 and Q12 increasingly demand explainability in design and manufacturing decisions. In short, performance alone is not enough; without transparency, AI remains scientifically impressive but industrially fragile.

Bringing these observations together, Table 3 exposes the trade-offs that define modern AI in formulation science: accuracy versus interpretability, and predictive power versus data demand. The emerging consensus is a hybrid philosophy—interpretable ensemble methods as the stable backbone, with deep and graph models layered on top as data richness grows. Such a composite framework encourages cooperation rather than competition among model families, blending human reasoning with machine abstraction. Ultimately, the comparative insights of Table 3 suggest that the future of AI-driven formulation design will not be dictated by any single algorithm, but by the intelligent orchestration of multiple ones—each contributing a distinct dimension of understanding to the complex landscape of materials and medicines.

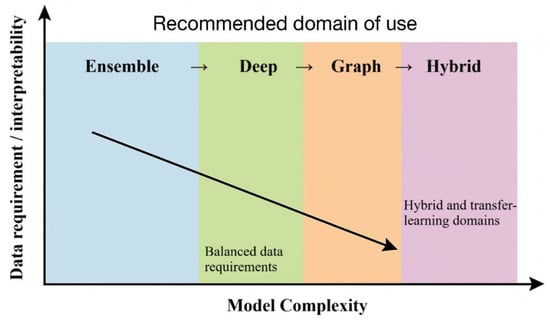

Figure 2 summarizes how model classes balance predictive performance, data requirements, and interpretability in pharmaceutical formulation. It highlights that ensemble methods occupy a relatively robust zone for current datasets, whereas deep, graph, and hybrid models offer additional gains mainly when richer and higher-quality data are available, often at the cost of transparency summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Figure 2.

Comparative performance summary of AI model classes in pharmaceutical formulation. The diagram positions ensemble, deep, graph, and hybrid model families along axes of data requirements and interpretability, illustrating how increasing model complexity generally improves predictive accuracy while reducing transparency. Colored zones indicate recommended domains of use based on current formulation datasets and applications.

3.5.4. Critique and Integrative Synthesis

Taken together, Table 1 and Table 2 move the discussion from empirical demonstration to comparative synthesis. While the former establishes how AI has been applied in real formulation contexts, the latter benchmarks how different model classes perform across domains. Building on these foundations, the following section critiques current evidence and integrates the insights into a coherent design perspective.

Current evidence, while promising, remains fragmented. Most demonstrations emphasize single-step prediction rather than closed-loop design; very few integrate feedback-driven retraining. The field still lacks unified benchmarks and uncertainty reporting.

- (1)

- Tree ensembles are the most validated baseline for current pharmaceutical datasets.

- (2)

- Graph and deep models lead in polymer informatics but need larger public data.

- (3)

- Optimization and RL approaches excel once a trustworthy surrogate exists.

- (4)

- Generative models represent a forward-looking frontier, best paired with rule-based constraints.

The synthesis of these insights underscores that AI excels when embedded inside a human-guided, data-rich, feedback-aware design cycle. Future progress depends less on algorithmic novelty and more on data governance, model interpretability, and experimental integration.

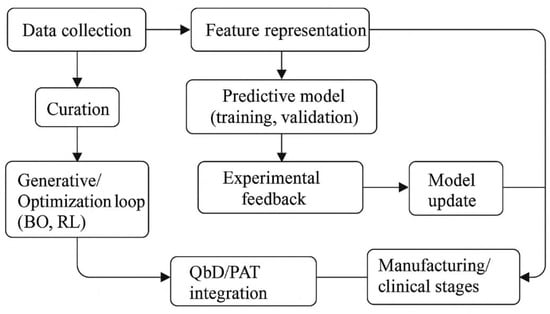

Figure 3 integrates these elements into an iterative AI-enabled formulation workflow. Rather than a linear sequence, it emphasizes a cyclical “design–test–learn–redesign” loop in which data collection, predictive modeling, candidate generation, and experimental feedback continuously inform one another. By embedding this loop within QbD and PAT principles, the figure highlights how AI can act as a connecting layer between formulation development, manufacturing control, and downstream clinical use.

Figure 3.

AI-enabled formulation pipeline from data to validated design. The workflow begins with data collection and curation, followed by feature representation and predictive model training to build surrogate models of formulation behavior. These models feed into a generative or an optimization loop—typically using BO or RL—to propose new candidate formulations. Experimental results are cycled back into the system to update the models, creating a closed “design–test–learn–redesign” loop that ultimately informs deployment in manufacturing and clinical settings, in alignment with QbD and PAT frameworks.

Overall, the comparative evidence suggests that claims of accuracy in AI-guided formulation must be qualified by data conditions. Reported R2 or MAE values are most informative when accompanied by a description of dataset size, chemical diversity, descriptor construction, and validation strategy. Without this context, apparently “state-of-the-art” performance may reflect favorable benchmarking choices rather than genuine advances in model capability. The present review therefore interprets the literature not as a leaderboard of algorithms, but as a map linking model families to the data conditions under which they are technically and practically justified. These results show how AI methods can organize and speed up formulation design and optimization. The next section uses this as a starting point to examine how AI-enabled workflows are connected to smart and sustainable DDS at the level of materials and devices.

4. Integration of AI with Smart and Sustainable Drug Delivery Systems

4.1. AI for Smart Drug Delivery Systems

Building upon these methodological foundations, the next logical step is the convergence of AI with smart and sustainable DDS—a defining evolution in pharmaceutics. Traditional DDS research focused on optimizing carrier composition and release kinetics through iterative experimentation; AI introduces a predictive, data-centric dimension capable of orchestrating material design, performance forecasting, and environmental responsibility simultaneously. Recent advances reveal that AI can guide the synthesis and modification of smart biomaterials—stimuli-responsive polymers, hybrid nanocarriers, and bio-based composites—while minimizing the ecological footprint inherent in conventional development [49]. For instance, ML-guided modeling has enabled predictive selection of polymer blends with tunable pH or temperature responsiveness, reducing the need for redundant synthesis cycles and thereby conserving energy and reagents [9]. Complementarily, AI-enabled screening of biopolymers derived from renewable feedstocks such as chitosan, alginate, or lignocellulosic derivatives supports the shift toward biodegradable, green DDS aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals [30]. Broader analyses reinforce this trend: Panchpuri et al. (2025) present a concise yet forward-looking review on how AI revolutionizes smart DDS by enabling predictive formulation, adaptive dosing, and real-time diagnostic feedback through data-driven modeling. Their synthesis highlights AI’s capacity to integrate multi-omics and sensor data for personalized, closed-loop control of therapeutic release—framing AI as the cognitive core of next-generation delivery platforms. This analytical lens effectively illustrates AI’s transformative role but remains limited by a lack of depth in addressing data bias, regulatory readiness, and model interpretability. While the review adeptly connects technical progress with clinical aspirations, it underplays the infrastructural and ethical challenges of deploying such systems in diverse healthcare contexts. Overall, the article advances the discourse by positioning AI-enabled DDS as a convergence point between automation, sustainability, and precision medicine—underscoring that true clinical translation will depend on harmonizing algorithmic intelligence with transparent, ethically governed design [14].

Analytically, the fusion of AI and material science is redefining how smartness and sustainability are operationalized. Smart materials respond dynamically to stimuli—pH, light, temperature, magnetic fields, or biomolecular signals—while sustainable systems minimize resource intensity and promote circular life cycles. AI accelerates both dimensions by offering predictive modeling of structure–property–performance linkages and enabling multi-objective optimization across environmental and clinical metrics. Deep neural and graph-based architectures can model how polymer topology, crystallinity, and cross-linking affect degradation rate and release kinetics, while Bayesian frameworks evaluate trade-offs between therapeutic efficacy and carbon cost. Such approaches parallel trends in green informatics, where ML predicts recyclability, toxicity, and life-cycle energy of biomaterials [31]. Ruiz-Gonzalez et al. further contextualized AI as a driver for greener pharmaceutical practice—selecting eco-friendly solvents, minimizing waste, and enabling sustainable-by-design chemistries [17]. Collectively, these efforts form a computational infrastructure for eco-by-design formulation—embedding sustainability criteria directly into the design space rather than applying them post hoc.

Parallel to global progress, regional pilot studies [50,51] have merged AI-based modeling with eco-friendly biopolymers—chitosan, alginate, and lignocellulosic derivatives—to design biodegradable nanogels and herbal transdermal systems that balance performance with environmental safety. Their outcomes underline a pragmatic innovation path: replacing high-cost proprietary datasets with iterative, small-scale modeling loops guided by ML to minimize waste and energy consumption. From a critical perspective, such works reveal the strength of contextual innovation yet also its fragility—data fragmentation, limited reproducibility, and lack of standardized validation impede scalability. Nonetheless, these studies collectively embody the principle of circular pharmaceutics, where digital intelligence and green material design co-evolve toward a responsible manufacturing paradigm suited to regional infrastructures.

These integrations remain constrained by data gaps, limited interpretability, and sustainability concerns, as discussed in greater detail in Section 5. When such constraints are addressed, however, AI-enabled smart DDS can exhibit unprecedented functionality. Closed-loop systems coupling biosensors, microprocessors, and responsive carriers embody the transition from static to adaptive therapeutics. In such architectures, AI algorithms analyze real-time biosignals—glucose, cortisol, temperature—and regulate actuator responses in microneedle arrays or hydrogel patches, modulating drug flux on demand. Experimental prototypes of AI-guided microneedle patches with real-time feedback have demonstrated improved dosing precision and reduced adverse effects [44]. Beyond wearable patches, AI-integrated transdermal systems use RL controllers to adjust permeation-enhancer levels or electrical stimuli dynamically, achieving personalized pharmacokinetic profiles [25]. Recent studies of biomolecule-driven nanocarriers underscore this synergy—AI frameworks now inform multi-stimuli-responsive systems that adjust release in response to biomarker cues [13]. Collectively, these developments signify the dawn of autonomous pharmaceutics, where data loops close seamlessly between sensing, decision, and actuation—a realization of precision medicine at the material interface.

4.2. AI for Sustainable and Green Pharmaceutics

From a sustainability vantage, AI also enables a circular pharmaceutics paradigm. Predictive analytics can identify recyclable or biodegradable excipients, simulate degradation pathways, and optimize packaging or process conditions to minimize waste. For example, ML models trained on polymer degradation kinetics predict end-of-life behavior under various environmental conditions, guiding selection of carriers that degrade harmlessly without microplastic residue [41]. RL loops embedded in process-analytical-technology frameworks allow continuous adjustment of solvent ratios, temperature, or mixing speed to maintain quality while cutting material losses—thus merging smart manufacturing with sustainable chemistry. Combined with digital twin models of both product and process, such AI ecosystems enable predictive control across the entire DDS life cycle—from raw material selection to patient-level monitoring—fulfilling the regulatory vision of quality by prediction [16].

To move beyond a purely conceptual link between AI and sustainability, several recent studies report explicit environmental metrics alongside AI- or model-based optimization. For example, the SolECOs platform couples thermodynamically informed ML models for API solubility with ReCiPe 2016 life-cycle impact indicators to rank single and mixed solvents for crystallization, enabling solvent choices that balance process performance with reduced environmental burden [52]. Similarly, the SUSSOL tool uses a Kohonen self-organizing map to cluster hundreds of solvents and then scores candidates according to safety, health, and environment criteria, allowing AI-guided substitution of non-benign solvents with greener alternatives [53]. In drug product manufacturing, an integrated flowsheet and optimization framework for wet granulation and tableting showed that adjusting process conditions to minimize energy consumption while preserving product quality can reduce energy use by 71.7% in the optimized batch case and 83.3% in the optimized continuous case, directly linking process decision variables to energy- and carbon-related performance metrics [54].

From a life-cycle perspective, a recent cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment (LCA) of oral solid dosage manufacturing compares direct compression, roller compaction, high-shear granulation, and continuous direct compression platforms and quantifies contributions from materials, equipment energy use, facility overheads, cleaning, and waste to the overall environmental footprint; the LCA is further coupled with a system model so that process parameters can be explored in terms of both product quality and carbon cost [55]. Together, these examples illustrate how AI- and model-based optimization of formulations and processes can be evaluated explicitly against life-cycle indicators such as global warming potential, cumulative energy demand, and process mass intensity, rather than treating sustainability as a qualitative afterthought.

Methodologically, these examples show how sustainability indicators can be embedded directly into AI-driven optimization rather than being evaluated only post hoc. In multi-objective Bayesian optimization or RL controllers, the objective function can be defined to simultaneously penalize (i) deviations from target critical quality attributes, (ii) economic cost, and (iii) LCA-derived indicators such as global warming potential, process mass intensity, or energy use per dose. Recent work on digital technologies for LCA further outlines how AI and machine learning can be integrated into all four phases of an LCA study—from inventory construction to impact assessment and interpretation—so that environmental impacts become algorithmically optimized outputs rather than external constraints [56].

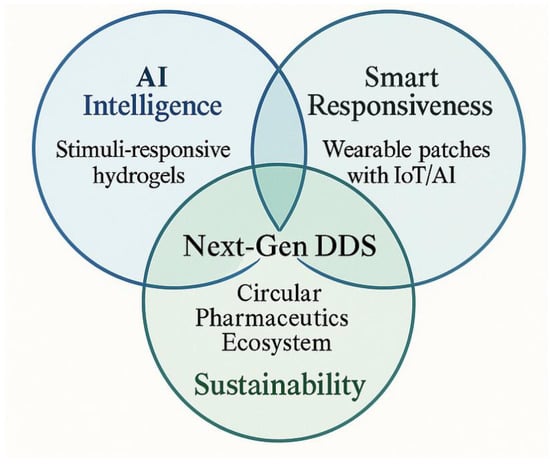

4.3. Convergence of Intelligence, Responsiveness, and Sustainability

Figure 4 illustrates the conceptual convergence of AI, smart responsiveness, and sustainability in next-generation DDS. The three intersecting domains represent AI (enabling predictive modeling and design optimization), smart responsiveness (achieved through stimuli-responsive and IoT-integrated materials), and sustainability (through biodegradable and eco-informed design). Their intersection embodies the vision of a circular pharmaceutics ecosystem—an intelligent, adaptive, and environmentally responsible DDS paradigm.

Figure 4.

AI and smart/sustainable DDS convergence framework.

5. Challenges, Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

5.1. Data and Model-Related Challenges

The ascent of AI-enabled, smart DDS opens vast promise, yet it is crucial to reckon with foundational obstacles—both technical and ethical—that could impede translation from bench to bedside. At the outset, the quality and availability of data remain a primary bottleneck: many datasets on biodegradation, release kinetics under physiological conditions, and patient-specific biomarkers are small, imbalanced, or confined to narrow domains. Models trained on such data risk overfitting, lack generalizability, and inherit biases from the underlying sources. These issues, also noted in medical AI literature [6,57], equally affect pharmaceutical datasets. The problem of data scarcity is particularly acute in emerging research ecosystems, where formulation datasets remain fragmented and often confined to herbal or polymeric systems [58]. Analyses of regional AI-based DDS highlight recurrent issues of overfitting, inconsistent preprocessing, and absence of cross-validation—symptoms of limited experimental throughput and unshared repositories. This situation highlights wider ethical and knowledge-sharing gaps: without transparent data governance and FAIR-data collaboration, the risks of algorithmic bias and poor reproducibility increase. Addressing these constraints demands coordinated regional frameworks for data sharing, capacity building, and interpretable modeling, ensuring that AI-enabled pharmaceutics advance equitably across both resource-rich and resource-limited settings. Another pressing issue is the black-box dilemma: high-performing AI models (e.g., deep neural networks, ensemble methods) often lack transparency in how inputs map to outputs, complicating interpretability, reproducibility, and regulatory trust. Recent advances in interpretable AI strive to unpack these relationships—attributing risk scores to features, generating counterfactuals, or employing attention mechanisms to highlight salient variables [59]. Still, for pharmaceutical stakeholders and regulatory agencies, reproducibility across datasets and environments remains an unmet expectation: model retraining, versioning, and audit trails must be rigorously documented to ensure robustness [6,18].

In practical terms, moving toward FAIR data in AI-enabled DDS requires more than high-level commitments. For findability, formulation datasets should be registered with persistent identifiers and standardized metadata describing composition, processing conditions, release protocols, and analytical methods. Accessibility can be improved through governed repositories and precompetitive data-sharing agreements that allow de-identified or aggregated datasets to be reused beyond the originating laboratory. Interoperability demands the use of common file formats, controlled vocabularies for excipients, dosage forms, and endpoints, and ontology-based encodings that make it possible to integrate data from ELNs, LIMS platforms, and clinical records. Finally, reusability depends on detailed documentation of experimental protocols, uncertainty estimates, and model-ready descriptors so that downstream users can reconstruct design decisions and reliably benchmark new algorithms against existing work [26,30,57].

Several ongoing efforts in pharmaceutical and biomedical AI already provide templates that DDS researchers can adapt. These include cross-institutional consortia that define common data models for preclinical and clinical data, initiatives to standardize reporting of in vitro and in vivo release profiles, and repositories that host curated polymer and excipient property datasets under well-defined licenses [6,26,29,30,57]. Adopting similar community standards for DDS—such as minimal information checklists for formulation experiments, shared ontologies for dosage forms, and harmonized descriptors for release and degradation behavior—would turn currently fragmented datasets into a reusable resource for model development, benchmarking, and regulatory evaluation [6,18,26,30,57].