Evaluation of Essential and Potentially Toxic Elements in Kalanchoe laetivirens Leaves, Tea, and Juice: Intake Estimates and Human Health Risk Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Digestion of Dried Leaves

2.3. Preparation of Aqueous Plant Extract

2.4. Obtaining Tea from the Plant Leaves

2.5. Elemental Measurement by Using ICP OES

2.6. Risk Assessment Model

2.7. Hazard Quotient (HQ) and Hazard Index (HI)

2.8. Carcinogenic Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Concentration of meta(loids) in Tea, Aqueous Extract and Leaves of K. laetivirens

3.2. Risk Assessment Model: Chronic Daily Intake (CDI)

3.3. Risk Assessment Model: Hazard Quotients (HQs) and the Total Hazard Index (HI)

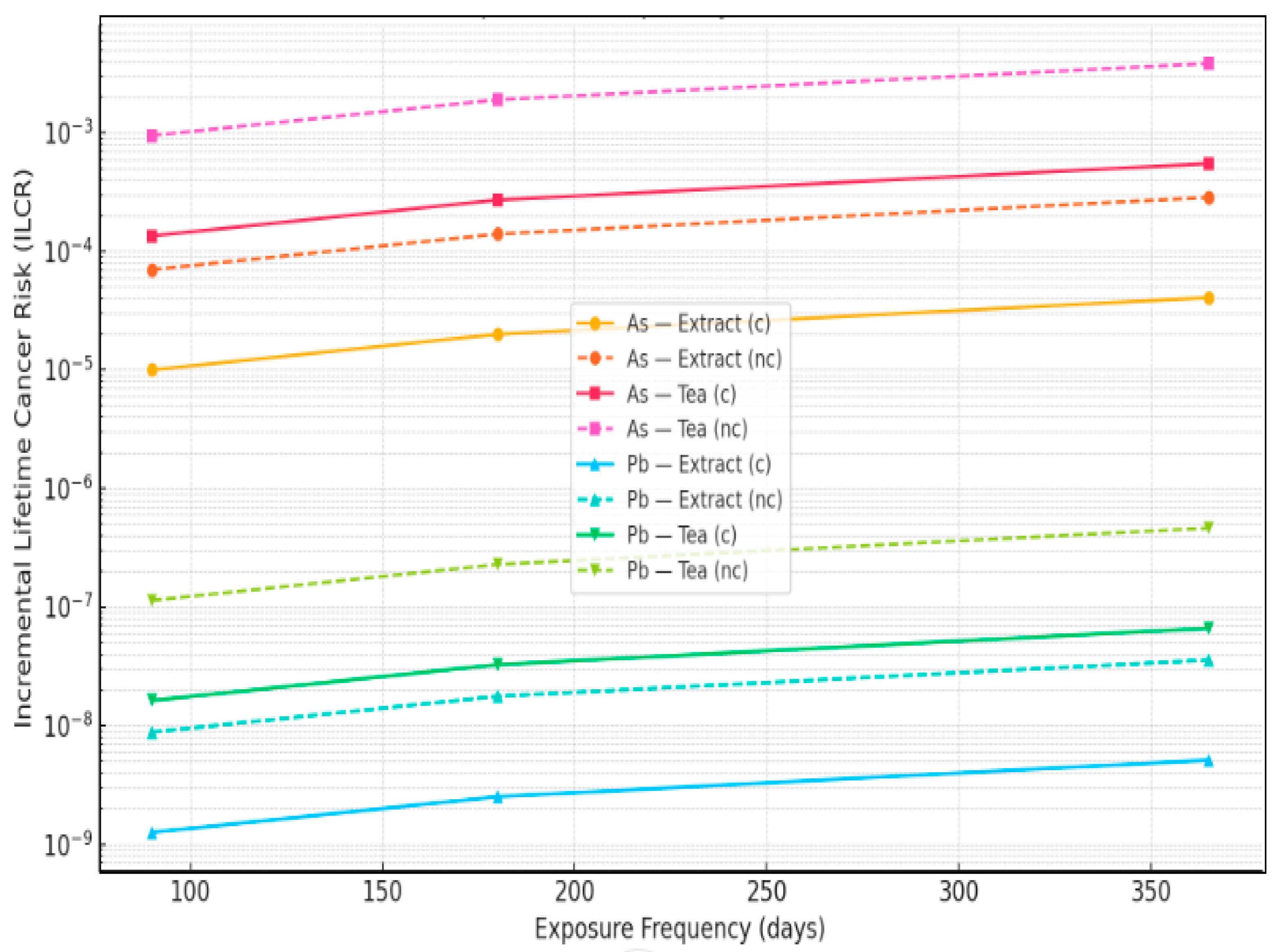

3.4. Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk (ILCR)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDI | Chronic Daily Intake |

| HQ | Hazard Quotient |

| HI | Hazard Index |

| ILCR | Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk |

| ICP OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission spectroscopy |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| CSF | Cancer slope factor |

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

| Al | aluminum |

| K | potassium |

| As | arsenic |

| Ba | barium |

| Co | cobalt |

| Cu | copper |

| Fe | iron |

| Mg | magnesium |

| Mn | manganese |

| Ni | nickel |

| P | phosphorus |

| Pb | lead |

| Se | selenium |

| V | vanadium |

| Zn | zinc |

| ANVISA | Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| UBM | Unified BARGE Method |

| PBET | Physiologically Based Extraction Test |

References

- Xia, Y.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Jin, W.-L. Drug repurposing for cancer therapy. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. Cancer; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/cancer (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Tan, L.; Siu, K.T.H.; Guan, X.-Y. Exploring treatment options in cancer: Tumor treatment strategies. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouh, A.; Mehdad, S.; El Ghoulam, N.; Daoudi, D.; Oubaasri, A.; El Mskini, F.Z.; Labyad, A.; Iraqi, H.; Benaich, S.; Hassikou, R.; et al. The use of medicinal plants by cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A cross-sectional study at a referral oncology hospital in Morocco. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, S.; Asif, H.M.; Nazar, H.M.; Akhtar, N.; Rehman, J.U.; Rehman, R.U. Medicinal plants combating against câncer—A green anticancer approach. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 4385–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrouni, I.A.; Elachouri, M. Anticancer medicinal plants used by Moroccan people: Ethnobotanical, pharmacological and phytochemical review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twilley, D.; Rademan, S.; Lall, N. A review on traditionally used South African medicinal plants, their secondary metabolites and their potential development into anticancer agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 261, 113101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagbo, I.J.; Otang-Mbeng, W. Plants Used for the Traditional Management of Cancer in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: A Review of Ethnobotanical Surveys, Ethnopharmacological Studies and Active Phytochemicals. Molecules 2021, 26, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrouni, I.A.; Elachouri, M. Anticancer medicinal plants used by Moroccan people: Ethnobotanical, preclinical, phytochemical and clinical evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 10, 113435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, H.; Matos, F.J.A. Plantas Medicinais do Brasil: Nativas e Exóticas; Instituto Plantarum: Nova Odessa, Brazil, 2002; p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- Trease, G.E.; Evans, W.C. Textbook of Pharmacognosy, 16th ed.; Tyndall and Cassel: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Garcês, H.M.P.; Champagne, C.E.M.; Townsley, B.T.; Sinha, N.R. Evolution of asexual reproduction in leaves of the genus Kalanchoe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15578–15583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.C.T.; Costa, L.C.B.; Costa, R.C.S.; Rocha, E.A. Abordagem etnobotânica acerca do uso de plantas medicinais na Vila Cachoeira, Ilhéus, Bahia, Brasil. Acta Farm. Bonaer 2002, 21, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.B.C.; Santos, A.T.; Azevedo, G.Z. Use of plants of the genus Kalanchoe as a potential treatment for inflammatory diseases. In Exploring the Field of Agricultural and Biological; Seven Editora: São José dos Pinhais, Brazil, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, R.; El-ahmady, S.; Singab, A.N. Genus Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae): A review of its ethnomedicinal, botanical, chemical and pharmacological properties. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2014, 4, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinpelu, D.A. Antimicrobial activity of Bryophyllum pinnatum leaves. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 193–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supratman, U.; FujitA, T.; Akiyama, K.; Hayashi, H. Insecticidal compounds from Kalanchoe daigremontiana × tubiflora. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, L.B.d.S.; Casanova, L.M.; Costa, S.S. Bioactive Compounds from Kalanchoe Genus Potentially Useful for the Development of New Drugs. Life 2023, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis de Andrade, E.; Machinski, I.; Terso Ventura, A.C.; Barr, S.A.; Pereira, A.V.; Beltrame, F.L.; Strangman, W.K.; Williamson, R.T. A Review of the Popular Uses, Anatomical, Chemical, and Biological Aspects of Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae): A Genus of Plants Known as “Miracle Leaf”. Molecules 2023, 28, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Resolução de Diretoria Colegiada—RDC Nº 10, de 9 de Março de 2010. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2010/rdc0010_09_03_2010.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- European Commission. Guidance Document on the Estimation of Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) for Measurements in the Field of Contaminants in Feed and Food. 2017. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-05/animal-feed-guidance_document_lod_en.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Mohammadi, A.A.; Zarei, A.; Majidi, S.; Ghaderpoury, A.; Hashempour, Y.; Saghi, M.H.; Alinejad, A.; Yousefi, M.; Hosseingholizadeh, N.; Ghaderpoori, M. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risk assessment of heavy metals in drinking water of Khorramabad, Iran. MethodsX 2019, 6, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Han, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, G.; Sun, Y. Potential Ecological Risk and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals and Metalloid in Soil around Xunyang Mining Areas. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Lara, R.; Suárez-Peña, B.; Megido, L.; Negral, L.; Rodríguez-Iglesias, J.; Fernández-Nava, Y.; Castrillón, L. Health Risk Assessment of Potentially Toxic Elements in the Dry Deposition Fraction of Settleable Partic-ulate Matter in Urban and Suburban Locations in the City of Gijón, Spain. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerba, C.P. Risk Assessment. In Environmental and Pollution Science, 3rd ed.; Brusseau, M.L., Pepper, I.L., Gerba, C.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 541–563. [Google Scholar]

- Junior, A.d.S.A.; Ancel, M.A.P.; Garcia, D.A.Z.; Melo, E.S.d.P.; Guimarães, R.d.C.A.; Freitas, K.d.C.; Bogo, D.; Hiane, P.A.; Vilela, M.L.B.; Nascimento, V.A.d. Monitoring of Metal(loid)s Using Brachiaria decumbens Stapf Leaves along a Highway Located Close to an Urban Region: Health Risks for Tollbooth Workers. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.C.G.; Melo, E.S.P.; Junior, A.S.A.; Gondim, J.M.S.; de Sousa, A.G.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Viana, L.F.; Carvalho, A.M.A.; Machate, D.J.; do Nascimento, V.A. Transfer of metal(loid)s from soil to leaves and trunk xylem sap of medicinal plants and possible health risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) Regional Screening Levels (RSLs)—Generic Tables. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). Calculating Hazard Quotients and Cancer Risk Estimates. 2022. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pha-guidance/conducting_scientific_evaluations/epcs_and_exposure_calculations/hazardquotients_cancerrisk.html (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Oni, A.A.; Babalola, S.O.; Adeleye, A.D.; Olagunju, T.E.; Amama, I.A.; Omole, E.O.; Adegboye, E.A.; Ohore, O.G. Non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks associated with heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in well-water samples from an automobile junk market in Ibadan, SW-Nigeria. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, B. Optimization of Cancer Risk Assessment Models for PM2.5-Bound PAHs: Application in Jingzhong, Shanxi, China. Toxics 2022, 7, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petenatti, M.E.; Petenatti, E.M.; Del Vitto, L.A.; Téves, M.R.; Caffini, N.O.; Marchevsky, E.J.; Pellerano, R.G. Evaluation of macro and microminerals in crude drugs and infusions of five herbs widely used as sedatives. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2011, 21, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, I.D.; Elaine, S.P.M.; Nascimento, V.A.; Pereira, H.S.; Silva, K.R.N.; Espindola, P.R.; Tschinkel, P.F.S.; Ramos, E.M.; Reis, F.J.M.; Ramos, I.B.; et al. Potential Health Risks of Macro- and Microelements in Commercial Medicinal Plants Used to Treatment of Diabetes. BioMed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6678931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente (CONAMA). Resolução nº 357, de 17 de Março de 2005. Dispõe Sobre a Classificação dos Corpos de Água e Diretrizes Ambientais para o seu Enquadramento. Diário Oficial da União Brasília, 18 March 2005. Available online: https://conama.mma.gov.br/?option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download&id=450 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045064 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Zhu, F.; Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Qu, L.; Qiao, M.; Yao, S. Assessment of potential health risk for arsenic and heavy metals in some herbal flowers and their infusions consumed in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Dobaradaran, S.; Spitz, J.; Mohammadi, A.; Tekle-Röttering, A.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Keshtkar, M. Metal(loid)s in herbal medicines and their infusions: Levels, transfer rate, and potential risks to human health. Hyg. Environ. Health Adv. 2023, 5, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson-Wood, K.; Jaafar, M.; Felipe-Sotelo, M.; Ward, N.I. Investigation of the uptake of molybdenum by plants from Argentinean groundwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 48929–48941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Molybdenum in Drinking-Water. Background Document for Preparation of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. (WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/11/Rev/1); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/75372/WHO_SDE_WSH_03.04_11_eng.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Antal, D.S.; Dehelean, C.A.; Canciu, C.M.; Anke, M. Vanadium in Medicinal Plants: New Data on the Occurence of an Element Both Essential and Toxic to Plants and Man; Analele UniversităĠii din Oradea, Fascicula Biologie. Tom. XVI/2, 2009; Université de Oradea: Oradea, Romania, 2009; pp. 5–10. Available online: https://bioresearch.ro/2009-2/005-10%20Antal.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Choi, J.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Kim, S.W.; Tosun, A.; Shim, J.H. Residues and contaminants in tea and tea infusions: A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Minimal Risk Levels (MRLs). Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/MRLS/mrlsListing.aspx (accessed on 30 July 2025).

| Step | Temperature (°C) | Pression (bar) | TRamp (min) | THold (min) | Power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 170 | 40 | 5 | 10 | 1800 |

| 2 | 200 | 40 | 2 | 20 | 1800 |

| 3 | 50 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| Chemical Elements | LOD (mg/L) | LOQ (mg/L) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 0.0282 | 0.0940 | 0.9998 |

| K | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.9996 |

| As | 0.0048 | 0.0160 | 0.9998 |

| Ba | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | 0.9997 |

| Co | 0.0008 | 0.0028 | 0.9998 |

| Cu | 0.0034 | 0.0113 | 0.9998 |

| Fe | 0.0071 | 0.0236 | 0.9998 |

| Mg | 0.0007 | 0.0023 | 0.9997 |

| Mn | 0.0010 | 0.0033 | 0.9998 |

| Mo | 0.0006 | 0.0020 | 0.9998 |

| Na | 0.0773 | 0.2576 | 0.9997 |

| Ni | 0.0013 | 0.0042 | 0.9999 |

| P | 0.0398 | 0.1325 | 0.9995 |

| Pb | 0.0041 | 0.0138 | 0.9999 |

| Se | 0.0068 | 0.0226 | 0.9999 |

| V | 0.0006 | 0.0021 | 0.9996 |

| Zn | 0.0023 | 0.0076 | 0.9999 |

| Elements | Raw Leaves (mg/kg) | Tea (mg/L) | Aqueous Extract (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 109.54 ± 7.56 | 20.47 ± 0.47 | 4.22 ± 0.12 |

| K | 15,399.31 ± 131.55 | 12,249.97 ± 240.17 | 943.16 ± 26.92 |

| As | 6.52 ± 0.42 | 5.98 ± 1.64 | 0.443 ± 0.0062 |

| Ba | 109.93 ± 2.10 | 70.17 ± 4.19 | 4.23 ± 0.060 |

| Co | 0.891 ± 0.159 | 0.855 ± 0.037 | 0.0525 ± 0.001 |

| Cu | 8.824 ± 0.211 | 1.114 ± 0.053 | 1.42 ± 0.0108 |

| Fe | 90.547 ± 1.64 | 3.680 ± 0.487 | 3.61 ± 0.056 |

| Mg | 3895.12 ± 100.63 | 3660.52 ± 32.17 | 218.83 ± 4.103 |

| Mn | 37.047 ± 0.917 | 28.88 ± 2.11 | 1.87 ± 0.016 |

| Mo | 2.136 ± 0.637 | 1.678 ± 0.017 | 0.127 ± 0.0013 |

| Na | 134.74 ± 2.82 | 132.94 ± 1.44 | 0.727 ± 0.061 |

| Ni | 1.094 ± 0.194 | 0.948 ± 0.043 | 0.097 ± 0.002 |

| P | 10,811.24 ± 197.22 | 5793.47 ± 760.74 | 664.071 ± 8.65 |

| Pb | 4.11 ± 0.86 | 3.82 ± 0.179 | 0.295 ± 0.0045 |

| Se | 7.012 ± 0.407 | 6.46 ± 1.50 | 0.455 ± 0.0033 |

| V | 12.21 ± 0.186 | 11.97 ± 0.401 | 0.844 ± 0.005 |

| Zn | 98.95 ± 33.19 | 69.11 ± 6.57 | 5.97 ± 0.062 |

| Element | EF_days/year | CDI_Extract_c | CDI_Extract_nc | CDI_Tea_c | CDI_Tea_nc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 90 | 2.124 × 10−6 | 1.487 × 10−5 | 1.030 × 10−5 | 7.211 × 10−5 |

| Al | 180 | 4.247 × 10−6 | 2.972 × 10−5 | 2.060 × 10−5 | 1.442 × 10−4 |

| Al | 365 | 8.612 × 10−6 | 6.029 × 10−5 | 4.178 × 10−5 | 2.924 × 10−4 |

| As | 90 | 6.688 × 10−6 | 4.681 × 10−5 | 9.028 × 10−5 | 6.319 × 10−4 |

| As | 180 | 1.338 × 10−5 | 9.363 × 10−5 | 1.805 × 10−4 | 1.264 × 10−3 |

| As | 365 | 2.712 × 10−5 | 1.899 × 10−4 | 3.661 × 10−4 | 2.563 × 10−3 |

| Ba | 90 | 2.129 × 10−6 | 1.490 × 10−5 | 3.531 × 10−5 | 2.472 × 10−4 |

| Ba | 180 | 4.257 × 10−6 | 2.980 × 10−5 | 7.062 × 10−5 | 4.943 × 10−4 |

| Ba | 365 | 8.633 × 10−6 | 6.043 × 10−5 | 1.432 × 10−4 | 1.002 × 10−3 |

| Co | 90 | 2.642 × 10−8 | 1.849 × 10−7 | 4.302 × 10−7 | 3.011 × 10−6 |

| Co | 180 | 5.284 × 10−8 | 3.699 × 10−7 | 8.604 × 10−7 | 6.023 × 10−6 |

| Co | 365 | 1.071 × 10−7 | 7.50 × 10−7 | 1.745 × 10−6 | 1.221 × 10−5 |

| Cu | 90 | 7.146 × 10−7 | 5.001 × 10−6 | 5.606 × 10−7 | 3.924 × 10−6 |

| Cu | 180 | 1.429 × 10−6 | 1.00 × 10−5 | 1.121 × 10−6 | 7.848 × 10−6 |

| Cu | 365 | 2.898 × 10−6 | 2.029 × 10−5 | 2.274 × 10−6 | 1.591 × 10−5 |

| Fe | 90 | 1.816 × 10−6 | 1.272 × 10−5 | 1.852 × 10−6 | 1.296 × 10−5 |

| Fe | 180 | 3.633 × 10−6 | 2.543 × 10−5 | 3.704 × 10−6 | 2.593 × 10−5 |

| Fe | 365 | 7.367 × 10−6 | 5.157 × 10−5 | 7.510 × 10−6 | 5.257 × 10−5 |

| K | 90 | 4.746 × 10−4 | 3.322 × 10−3 | 6.164 × 10−3 | 4.315 × 10−2 |

| K | 180 | 9.492 × 10−4 | 6.645 × 10−3 | 1.233 × 10−2 | 8.630 × 10−2 |

| K | 365 | 1.925 × 10−3 | 1.347 × 10−2 | 2.499 × 10−2 | 1.749 × 10−1 |

| Mg | 90 | 1.101 × 10−4 | 7.708 × 10−4 | 1.842 × 10−3 | 1.289 × 10−4 |

| Mg | 180 | 2.202 × 10−4 | 1.541 × 10−3 | 3.684 × 10−3 | 2.579 × 10−2 |

| Mg | 365 | 4.466 × 10−4 | 3.126 × 10−3 | 7.470 × 10−3 | 5.229 × 10−2 |

| Mn | 90 | 9.410 × 10−7 | 6.587 × 10−6 | 1.453 × 10−5 | 1.017 × 10−4 |

| Mn | 180 | 1.882 × 10−6 | 1.317 × 10−5 | 2.907 × 10−5 | 2.035 × 10−4 |

| Mn | 365 | 3.816 × 10−6 | 2.671 × 10−7 | 5.894 × 10−5 | 4.126 × 10−4 |

| Mo | 90 | 6.391 × 10−8 | 4.474 × 10−7 | 8.444 × 10−7 | 5.911 × 10−6 |

| Mo | 180 | 1.278 × 10−7 | 8.947 × 10−7 | 1.689 × 10−6 | 1.182 × 10−5 |

| Mo | 365 | 2.592 × 10−7 | 1.814 × 10−6 | 3.425 × 10−6 | 2.397 × 10−5 |

| Na | 90 | 3.658 × 10−7 | 2.561 × 10−6 | 6.689 × 10−5 | 4.682 × 10−4 |

| Na | 180 | 7.317 × 10−7 | 5.121 × 10−6 | 1.338 × 10−4 | 9.366 × 10−4 |

| Na | 365 | 1.484 × 10−6 | 1.039 × 10−5 | 2.713 × 10−4 | 1.899 × 10−3 |

| Ni | 90 | 4.881 × 10−8 | 3.417 × 10−7 | 4.770 × 10−7 | 3.339 × 10−6 |

| Ni | 180 | 9.762 × 10−8 | 6.834 × 10−7 | 9.541 × 10−7 | 6.679 × 10−6 |

| Ni | 365 | 1.979 × 10−7 | 1.386 × 10−6 | 1.934 × 10−6 | 1.353 × 10−5 |

| P | 90 | 3.342 × 10−4 | 2.339 × 10−3 | 2.915 × 10−3 | 2.040 × 10−2 |

| P | 180 | 6.683 × 10−4 | 4.678 × 10−3 | 5.830 × 10−3 | 4.082 × 10−2 |

| P | 365 | 1.355 × 10−3 | 9.487 × 10−3 | 1.182 × 10−2 | 8.276 × 10−2 |

| Pb | 90 | 1.484 × 10−7 | 1.039 × 10−6 | 1.922 × 10−6 | 1.346 × 10−5 |

| Pb | 180 | 2.969 × 10−7 | 2.078 × 10−6 | 3.844 × 10−6 | 2.691 × 10−5 |

| Pb | 365 | 6.020 × 10−7 | 4.214 × 10−6 | 7.796 × 10−6 | 5.457 × 10−5 |

| Se | 90 | 2.289 × 10−7 | 1.603 × 10−6 | 3.251 × 10−6 | 2.276 × 10−5 |

| Se | 180 | 4.579 × 10−7 | 3.205 × 10−6 | 6.502 × 10−6 | 4.551 × 10−5 |

| Se | 365 | 9.286 × 10−7 | 6.50 × 10−6 | 1.318 × 10−5 | 9.229 × 10−5 |

| V | 90 | 4.247 × 10−7 | 2.973 × 10−6 | 6.024 × 10−6 | 4.216 × 10−5 |

| V | 180 | 8.494 × 10−7 | 5.946 × 10−6 | 1.205 × 10−5 | 8.433 × 10−5 |

| V | 365 | 1.722 × 10−6 | 1.206 × 10−5 | 2.443 × 10−5 | 1.710 × 10−4 |

| Zn | 90 | 3.004 × 10−6 | 2.102 × 10−5 | 3.478 × 10−5 | 2.434 × 10−4 |

| Zn | 180 | 6.008 × 10−6 | 4.206 × 10−5 | 6.955 × 10−5 | 4.869 × 10−4 |

| Zn | 365 | 1.219 × 10−5 | 8.529 × 10−5 | 1.410 × 10−4 | 9.873 × 10−4 |

| Element | EF_days/year | HQ_Extract_c | HQ_Extract_nc | HQ_Tea_c | HQ_Tea_nc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 90 | 2.12 × 10−6 | 1.49 × 10−5 | 1.03 × 10−5 | 7.21 × 10−5 |

| Al | 180 | 4.25 × 10−6 | 2.97 × 10−5 | 2.06 × 10−5 | 1.44 × 10−4 |

| Al | 365 | 8.61 × 10−6 | 6.03 × 10−5 | 4.20 × 10−5 | 2.92 × 10−4 |

| As | 90 | 2.20 × 10−3 | 1.56 × 10−1 | 3.00 × 10−1 | 2.11 |

| As | 180 | 4.45 × 10−3 | 3.12 × 10−1 | 6.01 × 10−1 | 4.21 |

| As | 365 | 9.04 × 10−2 | 6.32 × 10−1 | 1.22 | 8.54 |

| Ba | 90 | 1.10 × 10−5 | 7.45 × 10−5 | 1.77 × 10−4 | 1.24 × 10−3 |

| Ba | 180 | 2.13 × 10−5 | 1.49 × 10−4 | 3.53 × 10−4 | 2.47 × 10−3 |

| Ba | 365 | 4.32 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−4 | 7.15 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| Co | 90 | 8.80 × 10−5 | 6.16 × 10−5 | 1.43 × 10−3 | 1.0 × 10−3 |

| Co | 180 | 1.76 × 10−4 | 1.23 × 10−3 | 2.87 × 10−3 | 2.0 × 10−2 |

| Co | 365 | 3.57 × 10−4 | 2.50 × 10−3 | 5.82 × 10−3 | 4.07 × 10−2 |

| Cu | 90 | 1.79 × 10−5 | 1.25 × 10−4 | 1.40 × 10−5 | 9.81 × 10−5 |

| Cu | 180 | 3.25 × 10−5 | 2.50 × 10−5 | 2.80 × 10−5 | 1.96 × 10−4 |

| Cu | 365 | 7.24 × 10−5 | 5.07 × 10−4 | 5.68 × 10−5 | 3.98 × 10−4 |

| Fe | 90 | 2.59 × 10−6 | 1.81 × 10−5 | 2.64 × 10−5 | 1.85 × 10−5 |

| Fe | 180 | 5.19 × 10−5 | 3.63 × 10−5 | 5.29 × 10−5 | 3.70 × 10−5 |

| Fe | 365 | 1.05 × 10−5 | 7.37 × 10−5 | 1.02 × 10−5 | 7.51 × 10−5 |

| K | 90 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| K | 180 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| K | 365 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mg | 90 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mg | 180 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mg | 365 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mn | 90 | 6.53 × 10−5 | 4.71 × 10−5 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 7.21 × 10−4 |

| Mn | 180 | 1.34 × 10−5 | 9.81 × 10−5 | 2.07 × 10−4 | 1.45 × 10−3 |

| Mn | 365 | 2.73 × 10−5 | 1.90 × 10−6 | 4.21 × 10−5 | 2.94 × 10−3 |

| Mo | 90 | 1.27 × 10−5 | 8.94 × 10−5 | 1.69 × 10−4 | 1.18 × 10−3 |

| Mo | 180 | 2.55 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 10−4 | 3.37 × 10−4 | 2.36 × 10−3 |

| Mo | 365 | 5.18 × 10−5 | 3.63 × 10−4 | 6.85 × 10−4 | 4.79 × 10−3 |

| Na | 90 | 1.22 × 10−5 | 8.53 × 10−5 | 2.22 × 10−3 | 1.56 × 10−2 |

| Na | 180 | 2.44 × 10−5 | 1.71 × 10−4 | 4.42 × 10−3 | 3.12 × 10−2 |

| Na | 365 | 4.94 × 10−5 | 3.46 × 10−4 | 9.04 × 10−3 | 6.33 × 10−2 |

| Ni | 90 | 2.44 × 10−6 | 1.70 × 10−5 | 2.38 × 10−5 | 1.66 × 10−4 |

| Ni | 180 | 4.88 × 10−6 | 3.41 × 10−5 | 4.77 × 10−5 | 3.33 × 10−4 |

| Ni | 365 | 9.90 × 10−6 | 6.69 × 10−5 | 9.65 × 10−5 | 6.75 × 10−4 |

| P | 90 | 16.7 | 116.5 | 145.5 | 1020 |

| P | 180 | 33.41 | 233.5 | 291.5 | 2040.5 |

| P | 365 | 67.75 | 474.3 | 591.0 | 4135 |

| Pb | 90 | 3.72 × 10−5 | 2.60 × 10−4 | 4.80 × 10−4 | 3.36 × 10−3 |

| Pb | 180 | 7.42 × 10−5 | 5.20 × 10−4 | 9.61 × 10−4 | 6.75 × 10−3 |

| Pb | 365 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 1.05 × 10−3 | 195 × 10−3 | 1,36 × 10−2 |

| Se | 90 | 4.58 × 10−5 | 3.20 × 10−4 | 6.50 × 10−4 | 4.56 × 10−3 |

| Se | 180 | 9.16 × 10−5 | 6.42 × 10−4 | 1.30 × 10−3 | 9.10 × 10−3 |

| Se | 365 | 1.86 × 10−4 | 1.30 × 10−3 | 2.64 × 10−3 | 1.84 × 10−2 |

| V | 90 | 8.50 × 10−5 | 5.94 × 10−4 | 1.20 × 10−3 | 8.42 × 10−3 |

| V | 180 | 1.70 × 10−4 | 1.19 × 10−3 | 2.40 × 10−3 | 1.68 × 10−2 |

| V | 365 | 3.44 × 10−4 | 2.41 × 10−3 | 4.88 × 10−3 | 3.42 × 10−2 |

| Zn | 90 | 1.0 × 10−5 | 7.0 × 10−5 | 6.704 | 8.0 × 10−4 |

| Zn | 180 | 2.0 × 10−5 | 1.40 × 10−4 | 2.32 × 10−4 | 1.62 × 10−3 |

| Zn | 365 | 4.06 × 10−5 | 2.84 × 10−4 | 4.70 × 10−4 | 3.30 × 10−3 |

| Element | EF (Days) | ILCR_Extract_c | ILCR_Extract_nc | ILCR_Tea_c | ILCR_Tea_nc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 90 | 1.00 × 10−5 | 7.02 × 10−5 | 1.35 × 10−4 | 9.48 × 10−4 |

| As | 180 | 2.00 × 10−5 | 1.40 × 10−4 | 2.71 × 10−4 | 1.90 × 10−3 |

| As | 365 | 4.07 × 10−5 | 2.85 × 10−4 | 5.49 × 10−4 | 3.84 × 10−3 |

| Pb | 90 | 1.26 × 10−9 | 8.83 × 10−9 | 1.63 × 10−8 | 1.14 × 10−7 |

| Pb | 180 | 2.52 × 10−9 | 1.77 × 10−8 | 3.27 × 10−8 | 2.29 × 10−7 |

| Pb | 365 | 5.12 × 10−9 | 3.58 × 10−8 | 6.63 × 10−8 | 4.64 × 10−7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siqueira, G.A.M.d.; Novais, L.C.; Ancel, M.A.P.; Ocampos, M.S.; Cabanha, R.S.d.C.F.; Oliveira, A.L.F.d.; Bastos Junior, M.A.V.; Melo, E.S.d.P.; Avellaneda Guimarães, R.d.C.; Granja Arakaki, D.; et al. Evaluation of Essential and Potentially Toxic Elements in Kalanchoe laetivirens Leaves, Tea, and Juice: Intake Estimates and Human Health Risk Assessment. Sci 2025, 7, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040180

Siqueira GAMd, Novais LC, Ancel MAP, Ocampos MS, Cabanha RSdCF, Oliveira ALFd, Bastos Junior MAV, Melo ESdP, Avellaneda Guimarães RdC, Granja Arakaki D, et al. Evaluation of Essential and Potentially Toxic Elements in Kalanchoe laetivirens Leaves, Tea, and Juice: Intake Estimates and Human Health Risk Assessment. Sci. 2025; 7(4):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040180

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiqueira, Giselle Angelica Moreira de, Leonardo Cordeiro Novais, Marta Aratuza Pereira Ancel, Marcelo Sampaio Ocampos, Regiane Santana da Conceição Ferreira Cabanha, Amanda Lucy Farias de Oliveira, Marco Aurélio Vinhosa Bastos Junior, Elaine Silva de Pádua Melo, Rita de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães, Daniela Granja Arakaki, and et al. 2025. "Evaluation of Essential and Potentially Toxic Elements in Kalanchoe laetivirens Leaves, Tea, and Juice: Intake Estimates and Human Health Risk Assessment" Sci 7, no. 4: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040180

APA StyleSiqueira, G. A. M. d., Novais, L. C., Ancel, M. A. P., Ocampos, M. S., Cabanha, R. S. d. C. F., Oliveira, A. L. F. d., Bastos Junior, M. A. V., Melo, E. S. d. P., Avellaneda Guimarães, R. d. C., Granja Arakaki, D., & Nascimento, V. A. d. (2025). Evaluation of Essential and Potentially Toxic Elements in Kalanchoe laetivirens Leaves, Tea, and Juice: Intake Estimates and Human Health Risk Assessment. Sci, 7(4), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040180