Abstract

Despite its economic profitability, fur farming in Europe, responsible for half of global production, faces a growing ethical backlash. Animal welfare concerns, particularly regarding mink, foxes, and raccoon dogs kept in restrictive cages, have intensified due to advocacy, scientific reviews, and COVID-19 outbreaks. In response, several EU nations have implemented bans or stricter regulations. However, limited research exists on EU public opinion. This study analyses data from Eurobarometer 533 (March 2023), surveying 26,368 citizens across 27 EU countries, to assess attitudes toward fur farming. Respondents selected from three policy preferences: a full ban, EU-wide regulation, or acceptance of current practices. Multinomial logistic regression and chi-square tests revealed significant socio-demographic and ideological influences. Older individuals were more supportive of current practices (p = 0.001), while higher education levels correlated with support for a ban or stricter regulation (p = 0.003). Income positively influenced support for regulation (p = 0.002), and women (p = 0.008), urban residents (p = 0.001), and those with regular animal contact (p = 0.007) were more likely to support reform. Right-leaning respondents (p = 0.012) and residents of countries without fur farming bans (p < 0.001) were less supportive. These findings suggest that values, demographics, and national legislation significantly shape public opinion. Aligning policy with evolving societal values requires integrated legislative reform, public engagement, and equitable transition strategies to ensure meaningful and sustainable improvements in animal welfare across the EU.

1. Introduction

Fur farming has long represented a controversial intersection between economic interests and animal welfare concerns [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Despite increasing ethical scrutiny, it is a multi-billion-euro industry that continues to generate revenue and employment in several countries. An estimation of 60,000 direct jobs depending on the industry was reported by Gremmen [9]. Globally, the primary producers of fur are China, North America, and Europe, where around 11,000 farms are active [10], involving the slaughter of 85 to 100 million animals per year [11]. In 2019, global retail sales of fur products were valued at approximately 22 billion euro, according to estimates from the Fur Information Council of America [7]. Today, half of the world’s fur production originates from Europe, with approximately 5000 farms operating across 22 countries [12]. Within Europe, Denmark (15 million), The Netherlands (4.75 million), Poland (6 million), and Finland (1.7 million) have historically been the largest exporters of mink pelts, supplying a substantial portion of the international fur market [9]. In 2017, Europe was responsible for 85% of the world’s mink fur production, with a retail value near 6 billion euro [13].

The most commonly farmed species for fur include mink (Neovison vison), the common red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and the Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus), the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides), rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), and the chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera) [7]. Many other species are also captured with traps, in the wild, for their fur, mainly in North America, but also in Europe, and species include beaver (Castor spp.), lynx (Lynx spp.), coyote (Canis latrans), muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), raccoon (Procyon lotor), sable (Martes zibellina), and many others [12]. Mink is by far the most prevalent species farmed in the EU. These animals are bred and reared in captivity specifically for their pelts, which are processed and used in the fashion industry to manufacture garments, accessories, and luxury products [14].

The typical fur farming production system involves small wire-mesh cages housed in rows within large sheds or open-sided barns. These cages often measure less than one square metre, offering very limited space for movement or expression of natural behaviours. Animals are kept in barren environments devoid of meaningful enrichment or stimulation. Social species are frequently housed singly or in inappropriate groupings, contributing to elevated levels of stress, aggression, and stereotypic behaviour such as pacing, fur-chewing, and self-mutilation [15].

From an animal welfare standpoint, fur farming has been widely criticised for its inability to meet even the most basic ethological needs of the animals. Numerous scientific reviews and investigations have highlighted chronic welfare problems, including physical injuries [16,17], untreated illnesses [18,19], cannibalism [20], and high mortality rates [21]. The European Parliament has acknowledged that existing cage systems fall short of ensuring adequate welfare standards [22]. Moreover, the slaughtering methods used have also raised significant welfare concerns [23].

Public discontent with fur farming has grown substantially over recent decades, fuelled by greater awareness of animal welfare issues, shifts in consumer ethics, and the emergence of powerful animal advocacy campaigns. Some EU countries have already banned fur farming, including Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, France, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Ireland, Slovakia, and Slovenia, and partial bans and stricter legislation was implemented in Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, and Sweden [24].

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the fur farming debate, particularly in Denmark and The Netherlands, where outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 were documented on mink farms, later spreading to other countries. These events raised questions about biosecurity and public health risks associated with fur farming under the “One Health” concept [10].

Despite the mounting evidence of welfare deficiencies and the wave of national bans, there remains a need for a comprehensive understanding of the EU citizens’ collective stance on fur farming. While scattered surveys and polls indicate significant opposition to the practice, systematic research exploring the breadth and depth of public attitudes across the EU is lacking. Such insight is essential not only for informing future legislation but also for aligning animal welfare policy with societal values.

Many economic and sociodemographic variables can affect the perception of fur farming in European citizens. Age shapes fur-farming perceptions as older adults often accept current practices due to traditional norms, while younger cohorts—exposed to ethical consumerism and social awareness—may display higher levels of scepticism [7,25]. Higher household income correlates with luxury consumption preferences and conditional support for welfare-regulated fur, reflecting socio-economic links between affluence and ethical consumption [26,27]. Political ideology predicts attitudes, and right-leaning individuals more often oppose bans or strict regulation, linked to higher social dominance and authoritarian tendencies [28]. Gender differences persist, with women generally showing greater empathy and stronger support for animal protection than men, influencing opposition to fur-farming [29]. Community context matters as rural residents, closely tied to agricultural livelihoods, tend to defend fur farming, whereas urbanites favour ethical and environmental considerations [30]. Regular contact with animals (e.g., pet ownership or work with animals) increases empathy and awareness of sentience, promoting support for stricter welfare or bans on fur farming [7,31]. Finally, national legislation both reflects and shapes public opinion and countries with fur-farming bans report higher citizen support for EU-wide prohibitions [26]. This research paper aims to investigate the position of EU citizens regarding fur farming in Europe, with a particular focus on perceptions of animal welfare standards within the industry. Through a cross-national analysis of public opinion data, the study seeks to elucidate the extent to which EU citizens support or oppose fur farming, identifying key societal drivers of these attitudes. By examining these perspectives, the paper contributes to the broader discourse on ethical food and fashion production, sustainable farming practices, and the democratic legitimacy of animal use industries in the EU context. The variables identified in the previous paragraph will be evaluated; therefore, the research questions or hypotheses relate to whether these affect the EU citizens’ perception of fur farming.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The dataset used in this study is freely accessible to the public and was gathered by the European Commission as part of the Special Eurobarometer 533 survey titled Attitudes of Europeans towards Animal Welfare. This survey forms part of the broader Eurobarometer 99.1 series [32].

This cross-sectional survey was administered between 3 and 26 March 2023, employing a multistage, clustered sampling approach. The fieldwork was carried out across 27 European Union nations. Data collection methods included both face-to-face computer-assisted interviews and remote video interviews conducted online. Questionnaires were translated into each country’s official language(s), ensuring that respondents were interviewed in their native or national tongue. The target population encompassed residents aged 15 and above from all EU Member States, including EU citizens living within any of the 27 nations involved. The survey explored respondents’ views on animal welfare alongside socio-demographic information. Each respondent constituted a single unit of analysis, with the complete dataset comprising a total of 26,368 individual responses.

The Eurobarometer strictly follows high ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and for those under 18, interviews were conducted only with parental or guardian consent and supervision. Additional technical details regarding sampling design and regional weighting can be accessed via GESIS [33].

2.2. Variables Used in This Study

This study aims to explore the stance of European citizens regarding animal welfare within the context of fur farming. To achieve this, the analysis focused on responses to question C6 of the survey, used as the dependent variable (DV). Before answering, participants were presented with the following introductory statement:

“Fur animals (such as minks, raccoons, dogs and foxes) are carnivorous animals which, in the wild, move freely over large areas. For commercial purposes (i.e., fur farming), they are raised on farms in cages. Currently, only generic EU animal welfare rules apply to fur farming, leaving specific rules to each individual EU Member State.”

The question itself reads as follows:

“Which of the following statements about fur farming in the EU comes closest to your view?”

- Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU.

- Fur farming should be maintained, but under EU-wide welfare conditions for those animals.

- The current welfare conditions of fur animals are acceptable, so you do not see a need to change current practices.

The following socio-demographic variables were employed as independent variables (IVs) in the analysis:

- ‘Age’: Provided in full years. This question was answered by all participants, and thus, no data were excluded on this basis.

- ‘Gender’: Respondents could choose from ‘male’, ‘female’, or ‘none of the above/non-binary/do not recognise yourself in the above categories’. For this study, only those who identified as ‘male’ or ‘female’ were included in the analysis. A total of 31 individuals selected the third option; due to the small number, their responses were excluded on statistical grounds. This decision is in no way intended to disregard or devalue individuals with diverse gender identities.

- ‘Highest Level of Education Completed’: Responses ranged from ‘1—no formal schooling/did not complete primary education’ to ‘9—doctorate/PhD’. All participants responded, and no exclusions were necessary.

- ‘Household Income’: Categorised into deciles (from the lowest 10% to the highest 10%) within the sample. A total of 3655 individuals either chose not to respond or indicated they did not know, and these cases were therefore omitted from the analysis.

- ‘Political Positioning’: Measured on a scale from ‘1 (far left)’ to ‘10 (far right)’. Here, 3386 respondents either refused to answer or selected “Don’t know” and were consequently excluded from the analysis.

- ‘Type of Community’: Categorised as ‘rural area or village’, ‘small town’, or ‘large town’. All participants responded to this question, and no data were excluded.

- ‘Regular Contact with Animals in Daily Life’: Respondents answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Full responses were obtained for this question, requiring no exclusions.

For all the questions, respondents were given the option to answer ‘don’t know’. Additionally, the choices ‘refuse to answer’ were explicitly available for both the ‘Household Income’ and ‘Political Positioning’.

A new variable was also created, organising the countries according to their law concerning fur farming (banned, strict, and not banned) and according to the list provided by Respect For Animals [24], listed in the introduction for banned and strict, with those not listed being the EU countries where fur farming is not banned. This variable was tested for its association with the choice of statements, using a Pearson’s chi-square test of independence.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The DV was initially analysed using univariate multinomial logistic regression models, with each of the socio-demographic variables serving as IVs. In a second stage, the DV was analysed using a multivariate multinomial logistic regression model, with all the socio-demographic variables entering as IVs. The selection of significant variables followed a backwards stepwise procedure. The overall fitness of the model was evaluated using the −2 log-likelihood chi-square test. Additionally, the pseudo R-squared value (Cox and Snell) is reported to provide further insight into model performance. The significance of individual predictors was examined through the Wald chi-square statistic. All statistical analyses were conducted via the NOMREG routine using the IBM® SPSS® Statistics software, version 29.0.2.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The tables accompanying each model present the logistic regression coefficients (β) for the predictor variables across the different response statements. These β values indicate the anticipated change in the log-odds (logit) of selecting a particular response category for every one-unit increase in the respective predictor variable. The logit represents the likelihood of an individual being classified under a specific response option. A β coefficient near zero suggests that the predictor has minimal impact on the logit. Conversely, the exponential of the coefficient, eβ, reflects the odds ratio for each predictor. An odds ratio greater than 1 (eβ > 1) indicates that the predictor raises the likelihood of the outcome, while a value of 1 (eβ = 1) suggests no influence. Odds ratios below 1 (eβ < 1) denote a decrease in the likelihood of the response. These correspond to positive, null, and negative β values, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistic

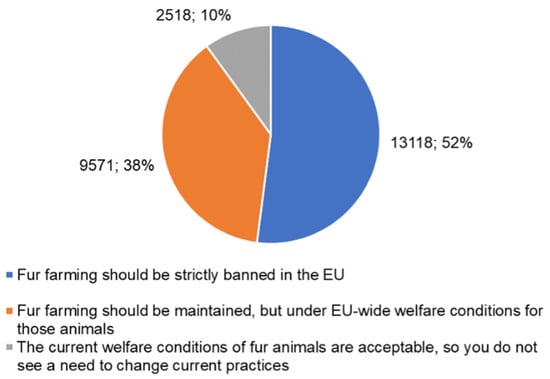

A total of 25,207 interviewees answered Question C6, and its distribution by the three options available can be consulted in Figure 1. As can be observed, there is a majority of interviewees in favour of banning fur farming in the EU.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the surveyed respondents by their choice to the question: “Which of the following statements about fur farming in the EU comes closest to your view?” Source: authors.

The variables ‘Gender’, ‘Regular contact with animals’, and ‘Community type’, have the following distribution: men 9313 (47.6%), women 10,267 (52.4%), with regular contact with animals 12,317 (62.9%), without regular contact with animals 7263 (37.2%) rural 6232 (31.8%), small town 7187 (36.7%), and large town 6161 (31.5%). The descriptive statistics related to the covariate IVs can be consulted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the covariate independent variables. Please note that ‘N’ varies as some interviewees did not answer or did not know the answer to that particular question.

3.2. Univariate Models

All independent variables were effectively fit to the models. The summary statistics for the model performance are presented in Table 2. Details regarding model parameters, including the odds ratios, are provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Statistics of the univariate multinomial regression models.

Table 3.

Parameterisation of the univariate multinomial regression models. Dependent variable: “Which of the following statements about fur farming in the EU comes closest to your view?”.

The univariate models have the following interpretation:

Older generations have a higher probability than younger generations of choosing the statement “The current welfare conditions of fur animals are acceptable, so you do not see a need to change current practices.” A 0.5% increase per year of age.

As the household income increases, the probability of choosing that fur farming should be allowed under EU-wide animal welfare conditions also increases. A 3.4% increase per decile of income level.

As the political positioning moves to the right, the probability of choosing that fur farming should be allowed under EU-wide animal welfare conditions decreases (4.8% per point on the scale); however, it decreases even further for the choice of the statement “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU.”

Men have a lower probability of choosing that “Fur farming should be allowed under EU-wide animal welfare conditions” (6.9%), and even lower for “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU” (34.5%).

Small towns and rural areas have a lower probability of choosing that fur farming should be allowed under EU-wide animal welfare conditions, decreasing 4.1% and 7%, respectively. This probability is even lower for the choice “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU”, decreasing 3.6% and 14%, respectively.

Individuals without regular contact with animals have a lower probability of choosing the statement “Fur farming should be maintained, but under EU-wide welfare conditions for those animals” (a decrease of 27.1%). The decrease is even higher for the statement “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU” (46.7%).

3.3. Multivariate Model

The model fitted the data very well (−2 log likelihood 35,551, chi-square 621.56, 16 df, p < 0.001), pseudo-R2 (Cox and Snell) = 0.031. All the parameters, except ‘Age’ were found to be significant (−2 log likelihood, chi-square, df, p-value): ‘Household income’ (35,588, 128.54, 2, p < 0.001), ‘Political positioning’ (35,776, 222.371, 2, p < 0.001), ‘Education level’ (35,604, 50.108, 2, p < 0.001), ‘Gender’ (35,682, 128.540, 2, p < 0.001), ‘Community type’ (35,566, 12.255, 4, p = 0.016), and ‘Regular contact with animals’ (35,696, 142.607, 2, p < 0.001). The full description of the significant parameters of the model is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameterisation of the multivariate multinomial regression model fitted to the data. Dependent variable: “Which of the following statements about fur farming in the EU comes closest to your view?”.

The probability of an individual choosing each statement is calculated through the generic equation:

where P(Y = j|X) is the probability of the outcome being category j given variables X. βj are the parameters calculated by the model for category j. βk are the coefficients of the other categories including β0 as the intercept and β1 to β6. β1 is the parameter related to household income of the individual, and X1 is the decile of the household income of the individual. The β2 is the parameter related to the political positioning of the individual, and X2 is the value on the scale of political positioning. The β3 is the parameter related to the education level of the individual, and X3 is the value on the scale of education of the individual. The β4 is the parameter related to the gender of the individual, and X4 is the dummy variable related to gender. The β5 is the parameter related to the type of community of the individual, and X5 is the dummy variable related to the type of community. The β6 is the parameter related to the regular contact with animals of the individual, and X6 is the dummy variable related to regular contact with animals.

The interaction between factors and covariates in multivariate model makes it very difficult or impossible at all to interpret. Our comments and discussion will, therefore, be based in the univariate models. Due to the immense number of possible combinations of variables determining different individual profiles, we leave to the curiosity of the reader the calculation of these probabilities for their chosen individual profiles. For that, use Equation (1) and the corresponding parameters found in Table 4. For example, the probability of a male interviewee living in a rural setting without regular contact with animals, aged 40, with an education level 6, political positioning 5, and income 5, the answer “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU” is calculated as:

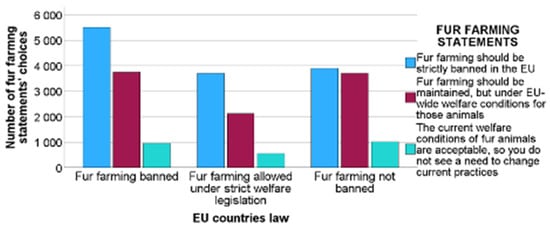

3.4. Association Between EU Countries’ Law and Position Concerning Fur Farming

The test of association was found to be significant (χ2 = 261.437, 4 df, p < 0.001), and, therefore, there is a positive association between countries where legislation has banned fur farming and the choice of the statement “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU”. There is also a positive association between countries where legislation does not ban fur farming and the choice of the statement “The current welfare conditions of fur animals are acceptable, so you do not see a need to change current practices.” The distribution of responses accordingly to countries’ legislation can be consulted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cross-tabulation showing the distribution of responses accordingly to countries’ legislation. Source: authors.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Age Effect

This study shows that older generations of EU citizens are more likely than younger ones to consider current welfare conditions in EU fur farming acceptable. A possible explanation for this result is that older generations may be more accustomed to traditional uses of animals in agriculture and industry, including for clothing [34]. Having grown up in a time when fur was more widely accepted and seen as a symbol of quality and status, older individuals might view fur farming as a normal and unproblematic practice. As a result, they may be less inclined to question the welfare conditions of animals farmed for fur, perceiving them through an angle of utilitarianism shaped by economic rationales and anthropocentric speciesism [35]. Older generations have also been shown to understand animal sentience less well [36].

In a different position, younger generations have grown in an era marked by an evolving awareness towards animal rights and ethical consumption [37,38,39]. The youth are more likely to be influenced by educational campaigns, social media advocacy, and evolving societal values that challenge the legitimacy of industries perceived to harm animals [40,41]. These age-related differences may contribute to greater scepticism among younger generations toward fur farming.

Generational differences in trust toward institutions and regulatory frameworks might also be relevant. Older individuals may place more confidence in existing EU regulations and the assumption that if a practice is legally permitted, it must meet acceptable standards [42]. Younger people, on the other hand, may be more critical of regulatory shortcomings, particularly if they believe that legislation has failed to keep pace with ethical progress or scientific understanding of animal welfare [37,38].

This generational divide also aligns with broader patterns observed in public opinion research, where older populations tend to be more conservative in their views on change, especially when tradition and economic interests are involved. In contrast, younger citizens are more open to reform and transformation in line with progressive values [43].

4.2. The Household Income Effect

The finding that individuals with higher household incomes are more likely to choose the second statement “Fur farming should be maintained, but under EU-wide welfare conditions for those animals” suggests that higher income levels are associated with the consumption of these luxury products, and therefore, they prefer the status quo with improved animal welfare regulation.

Environmental studies often reference the concept known as the Environmental Kuznets Curve. This theory suggests that as a country’s per capita income rises, environmental impact initially increases but eventually declines once a certain income threshold is reached [44]. Some explanations for why more affluent countries or regions tend to lessen their environmental footprint point to changes in the values of wealthier individuals. Once their fundamental needs are satisfied, these individuals often develop a tendency to prioritise altruistic concerns and an appreciation for environmental and aesthetic quality [45]. This concept could eventually be applied to luxury fur product consumption, as it was observed for animal food by Frontuto et al. [46], and for canine welfare by Kawata [47].

4.3. The Political Positioning Effect

The observed relationship between political orientation and responses to the fur farming question reveals important ideological underpinnings in attitudes toward animal welfare policy. Specifically, the finding that as political positioning shifts to the right, the probability of supporting the regulation of fur farming under EU-wide welfare standards decreases, and that the probability of supporting a total ban decreases even more steeply, suggests that individuals on the political right are less inclined to support either regulatory intervention or the prohibition of fur farming.

Right-wing ideology is commonly understood through two main psychological dimensions, the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA), and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) [48]. The RWA emphasises obedience to authority, adherence to traditional norms, and hostility toward those who challenge social conventions [49]. In contrast, SDO reflects a preference for hierarchical social structures and dominance over lower-status groups [50]. Both RWA and SDO have been shown to independently predict prejudice and support for discriminatory attitudes. In research conducted by Dhont and Hodson [51] in Europe (Belgium), they found that right-wing ideologies are associated with greater support for animal exploitation, driven by these theories, in the case of SDO, belief in human superiority over animals. These results are also corroborated by a study in the USA [52], where it was found that conservative beliefs were linked to lower support for animal welfare and stronger endorsement of speciesism.

Conservatives may also tend to defend fur farming by placing greater importance on economic freedom and rural livelihoods at the expense of animal welfare. A recent study conducted in Belgium and The Netherlands [53] shows a growing emphasis on animal protection over time, in election manifestos. The most prominent topics were farmed animal welfare and wildlife/biodiversity. Left-wing parties consistently advocated for stronger animal protection, while right-wing parties tended to prioritise economic interests.

4.4. The Gender Effect

The finding that men are less likely than women to support either a regulatory approach to fur farming or a complete ban reveals notable gender differences in attitudes toward fur animal welfare and ethical consumption. Specifically, the lower probability among men (6.9%) for supporting regulation under EU-wide welfare conditions, but especially supporting a strict ban (34.5%), suggesting that men are more inclined than women to support the status quo, which accepts current welfare conditions without requiring change.

This result is consistent with existing research in the fields of sociology [47,48,54,55], psychology [56,57], and animal studies [30,51], which frequently identify women as being more sensitive to animal welfare issues and more likely to adopt ethical stances regarding animal use. Women generally score higher on measures of empathy, compassion, and concern for the treatment of animals [58]. These tendencies are reflected in consumer behaviour as well, with women more likely to avoid products associated with animal suffering and to support animal rights or welfare legislation [59].

Men, on the other hand, often exhibit a more utilitarian or instrumental view of animals, particularly in relation to traditional industries such as farming, hunting, or product manufacturing [60]. Cultural norms that associate masculinity with pragmatism, tradition, and economic rationality may also contribute to a greater tolerance among men for existing practices in fur farming, particularly if these are seen as economically legitimate or culturally embedded.

Throughout human evolution, men and women have traditionally assumed different societal roles, which may have influenced their attitudes toward animals. Historically, men were more involved in hunting, which may have fostered a more utilitarian and emotionally detached view of animals. In contrast, while women also viewed animals as sources of food, their socialisation into caregiving and nurturing roles contributed to the development of more empathetic and moralistic attitudes toward animals [60]. Given these deep-rooted gender differences, it is unsurprising that our study also found consistent disparities between male and female perspectives. Notably, such differences persist even in Western societies where gender equality is more prominent [61], and they have also been observed across diverse countries and cultures worldwide [58].

4.5. The Effect of the Type of Community

The finding that respondents from small towns and rural areas are less likely to support either statement 2 (“Fur farming should be maintained, but under EU-wide welfare conditions”) or statement 1 (“Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU”) suggests that residents in less urbanised regions are more inclined to endorse the status quo that is, they are more likely to view current fur farming practices as acceptable and see no need for change (statement 3).

This pattern aligns with broader socio-cultural and economic aspects that influence attitudes toward animal farming and rural livelihoods. In rural and semi-rural contexts, people are often more closely connected (directly as active agents or indirectly through the living style context) to agricultural and animal farming. These industries, including fur farming, may be considered of paramount importance to local economies, employment, and cultural identity. As such, any external criticism or proposed change to these practices (especially bans or increased regulation) may be perceived as a threat or as an imposition by distant, decontextualised, urban-centred political agendas [62].

When it comes to food production, urban residents are more likely than those in rural or town settings to believe that EU food production is costlier due to stricter regulations like animal welfare standards, likely due to greater exposure to regulatory information and consumer advocacy [63]. However, people living in rural areas and small towns may place greater emphasis on the practical economic difficulties of farming [64]. Being more closely connected to agriculture, these communities might prioritise issues like financial assistance to support local farms, safeguard food security and preserve rural ways of life. Analytic hierarchical processes help determine consumer choices, and personal factors have a stronger influence on consumer decisions than psychological, social, or cultural factors [65]. As such, and since food holds a higher position in the hierarchy than fur, individuals in the urban areas may be less sensitive to animal welfare issues related to food than to those related to fur.

Europeans living in rural areas are more likely to hold conservative views, express dissatisfaction with how democracy functions in their country, and show lower levels of trust in the political system [66]. This factor also influences the results obtained, as rural communities often value continuity, tradition, and self-reliance, and may view animal use (whether for food, clothing, or work) as a natural and acceptable part of life. From this perspective, ethical concerns about animal suffering may not be seen as sufficiently compelling to justify disrupting traditional practices. Europeans from urban areas tend to have a greater distance (both physical and psychological) from the realities of animal farming, and often form their opinions based on broader ethical, environmental, or symbolic considerations [66]. As a result, support for bans or regulatory reforms tends to be higher in cities, where fur use is more likely to be viewed as abstracting moral values rather than a practical livelihood.

4.6. The Effect of Regular Contact with Animals

The finding that individuals without regular contact with animals are less likely to support either regulatory reform (“Fur farming should be maintained, but under EU-wide welfare conditions”) or a complete ban (“Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU”) indicates that higher levels of personal experience with animals play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward more positive animal welfare and ethical fur farming practices.

Previous research has demonstrated that exposure to animals fosters greater empathy and concern with their well-being [67,68,69,70,71]. People who have pets, work with animals, or live in environments where they regularly observe animal behaviour tend to develop a stronger emotional connection with animals and a greater awareness of their capacity to suffer. This awareness often translates into heightened sensitivity to animal welfare issues, including the conditions in which animals are farmed for fur. A study conducted with students in Belgium and The Netherlands [72] also found that regular contact with animals conveys more positive attitudes towards animal welfare.

Prokop and Tunnicliffe [73] reached the same conclusion with children in Slovakia.

Concerns about animal welfare are shaped by both psychological mechanisms and ethical considerations. One key psychological factor is the similarity principle, which suggests that people are more likely to empathise with animals if they see them as similar to themselves or to those they care about, such as pets [74,75]. This empathy can increase concern for the welfare of farmed animals. In the context of fur farming, Arney and Piirsalu [76] discussed the rights-based ethics in opposition to animals’ fur farming welfare, emphasising animals’ inherent rights incompatibility with animal welfare. Care ethics stresses moral obligations arising from human–animal relationships [77]. Emotional responses, especially among empathetic individuals, can strengthen ethical concerns [74,75].

4.7. The Effect of the Law of the Country

The findings of the present study suggest a strong association between national legislation on fur farming and public attitudes towards its practice among EU citizens. Specifically, in countries where fur farming is legally banned, there is a higher likelihood that citizens support the statement, “Fur farming should be strictly banned in the EU.” Conversely, in countries where fur farming remains legal, there is a greater tendency for citizens to agree with the statement, “The current welfare conditions of fur animals are acceptable, so you do not see a need to change current practices.” These patterns reveal a potential mutual reinforcement between legislative frameworks and public opinion.

The relationship between national legislation on fur farming and public attitudes within the EU reflects the dynamic interaction between evolving laws, ethical concerns, and societal values regarding animal welfare. Legislative changes across the EU have increasingly responded to public opposition to fur farming. The United Kingdom, while still in the EU, was among the first to introduce a ban on fur farming, signalling the public sentiment [7]. Other countries have followed, with initiatives such as “Fur Free Europe” calling for a comprehensive ban across the EU [78].

Public support for legislative bans on fur farming is widespread. Surveys across EU member states show strong support for banning fur products, largely due to animal welfare concerns [7,79]. While opposition is evident throughout the EU. Animal advocacy organisations have significantly shaped public opinion by raising awareness of welfare issues in fur farming [78].

4.8. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. In the first place, the collection of data always offers limitations, as the construction of variables may influence perceptions. For example, interviewees with no stronger opinions might casually select the third fur farming positioning option “current conditions are acceptable…”, treating it as an “indifferent” or “don’t know” option if they do not have a strong position regarding fur farming. Also, political positioning is more than standing in a left-right scale, and eventually, not all political nuances are captured with this simplistic scale.

Secondly, the data rely on self-reported attitudes, which may be influenced by social desirability bias or incomplete knowledge of fur farming practices. Third, while demographic factors such as age, income, gender, political views, and place of residence were included, other important influences (such as cultural background, religion, or media exposure) were not examined. Fourth, the cross-sectional design captures opinions at one point in time and cannot measure how attitudes may change in response to new policies, campaigns, or societal debates. Also, because attitudes differ across EU member states, caution is needed when generalising findings to the entire EU population. Finally, the multivariate model could be more refined with additional variables such as differences between countries; however, this process would create even higher degrees of complexity making it impossible to interpret.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that attitudes toward fur farming in the EU are shaped by age, income, gender, political views, urban–rural differences, regular contact with animals, and national laws. These factors highlight the need for inclusive policymaking that balances animal welfare with local economies and traditions. Education, open dialogue, and opportunities for human–animal interaction can help build empathy and public consensus. National legislation also plays a key role in shaping values, suggesting that legal reform can drive broader social change. To be effective, EU policies on fur farming must combine legislation, public engagement, and fair transition measures, ensuring reforms are both ethically grounded and socially sustainable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.; methodology, F.M.; validation, N.B., M.J. and J.S.; formal analysis, F.M.; investigation, F.M., N.B., M.J. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M., N.B., M.J. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, F.M., N.B., M.J. and J.S.; visualisation, F.M., N.B., M.J. and J.S.; supervision, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This is a third-party data study. Data was collected originally by Eurobarometer for the European Commission. Both Eurobarometer and European Commission adhere to the strictest ethical procedures.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original dataset used in this study are available open access in the Eurobarometer repository, GESIS from The Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences at https://doi.org/10.4232/1.14142.

Acknowledgments

To the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) for financial support to CISAS UIDB/05937/2020 and UIDP/05937/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tonsor, G.T.; Wolf, C.A. US Farm Animal Welfare: An Economic Perspective. Animals 2019, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandøe, P.; Christiansen, S.B.; Appleby, M.C. Farm Animal Welfare: The Interaction of Ethical Questions and Animal Welfare Science. Anim. Welf. 2003, 12, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.; Hubbard, C. Reconsidering the Political Economy of Farm Animal Welfare: An Anatomy of Market Failure. Food Policy 2013, 38, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.M.; Goodnight, G.T. Entanglements of Consumption, Cruelty, Privacy, and Fashion: The Social Controversy over Fur. Q. J. Speech 1994, 80, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooman, S. Politics, Law, and Grasping the Evidence in fur Farming: A Tale of Three Continents; Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group: Lanham, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, R. Animal Protection and Public Policy. In Animals, Politics and Morality; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2024; pp. 194–230. ISBN 1526183749. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, C.; McCulloch, S.P. Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, M. Liberal Neutrality and Consumption: The Dispute Over Fur. In Exploring Sustainable Consumption; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gremmen, K.J.M. Safeguarding Animal Welfare in the European Fur Farming Industry. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Twente, Twente, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O.; Maurin, M.; Devaux, C.; Colson, P.; Levasseur, A.; Fournier, P.-E.; Raoult, D. Mink, SARS-CoV-2, and the Human-Animal Interface. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 663815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C.; Pilny, A.; Steedman, C.; Grant, R. One Health Implications of Fur Farming. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1249901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fur Federation Sustainable Fur: Farming Fur Europe. Available online: https://www.sustainablefur.com/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Hansen, H.O. European Mink Industry—Socio-Economic Impact Assessment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani, M.; Coste-Maniere, I. To Fur or Not to Fur: Sustainable Production and Consumption Within Animal-Based Luxury and Fashion Products. In Textiles and Clothing Sustainability: Sustainable Fashion and Consumption; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 41–60. ISBN 978-981-10-2131-2. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, B.I.F.; Møller, S.H.; Malmkvist, J. Animal Welfare Measured at Mink Farms in Europe. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 248, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, A.; Agger, J.F.; Clausen, T.; Bertelsen, S.; Jensen, H.E.; Hammer, A.S. Anatomical Distribution and Gross Pathology of Wounds in Necropsied Farmed Mink (Neovison Vison) from June and October. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015, 58, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, A.; Hammer, A.S.; Jensen, H.E.; Bonde-Jensen, N.; Lassus, M.M.; Agger, J.F.; Larsen, P.F. Foot Lesions in Farmed Mink (Neovison Vison) Pathologic and Epidemiologic Characteristics on 4 Danish Farms. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, J.M.; Agger, J.F.; Aalbæk, B.; Struve, T.; Hammer, A.S.; Jensen, H.E. Dam Characteristics Associated with Pre-Weaning Diarrhea in Mink (Neovison Vison). Acta Vet. Scand. 2018, 60, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, J.M.; Agger, J.F.; Dahlin, C.; Jensen, V.F.; Hammer, A.S.; Struve, T.; Jensen, H.E. Risk Factors Associated with Diarrhea in Danish Commercial Mink (Neovison Vison) during the Pre-Weaning Period. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, J.-A. Freeing Subjectivities. In Knowing Life: The Ethics of Multispecies Epistemologies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 167. [Google Scholar]

- Rattenborg, E.; Dietz, H.-H.; Andersen, T.H.; Møller, S.H. Mortality in Farmed Mink: Systematic Collection versus Arbitrary Submissions for Diagnostic Investigation. Acta Vet. Scand. 1999, 40, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, T.B.; van Gerwen, M.; Meijer, E.; Tobias, T.J.; Giersberg, M.F.; Goerlich, V.C.; Nordquist, R.E.; Meijboom, F.L.B.; Arndt, S.S. End the Cage Age: Looking for Alternatives: Overview of Alternatives to Cage Systems and the Impact on Animal Welfare and Other Aspects of Sustainability; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Linzey, A.; Linzey, C. Brief Overview: Fur Factory Farming Worldwide. In An Ethical Critique of fur Factory Farming; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Respect for Animals a Guide to Fur Bans Around the World. Available online: https://respectforanimals.org/a-guide-to-fur-bans-around-the-world/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Carnovale, F.; Xiao, J.; Shi, B.; Arney, D.; Descovich, K.; Phillips, C.J.C. Gender and Age Effects on Public Attitudes to, and Knowledge of, Animal Welfare in China. Animals 2022, 12, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riuzzi, G.; Contiero, B.; Gottardo, F.; Cozzi, G.; Peker, A.; Segato, S. Socio-Economic Analysis of the EU Citizens’ Attitudes toward Farmed Animal Welfare from the 2023 Eurobarometer Polling Survey. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1505668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Al Mamun, A.; Yang, Q.; Masukujjaman, M. Predicting Sustainable Fashion Consumption Intentions and Practices. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhont, K.; Hodson, G.; Leite, A.C. Common Ideological Roots of Speciesism and Generalized Ethnic Prejudice: The Social Dominance Human–Animal Relations Model (SD–HARM). Eur. J. Pers. 2016, 30, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Basso Ricci, E.; Colombo, E.S. The Complexity of the Human–Animal Bond: Empathy, Attachment and Anthropomorphism in Human–Animal Relationships and Animal Hoarding. Animals 2022, 12, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran-Cournane, F.; Cain, T.; Greenhalgh, S.; Samarsinghe, O. Attitudes of a Farming Community towards Urban Growth and Rural Fragmentation—An Auckland Case Study. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Meng, C.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Y. Pet Ownership and Its Influence on Animal Welfare Attitudes and Consumption Intentions Among Chinese University Students. Animals 2024, 14, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission and European Parliament Eurobarometer 99.1, ZA7954 Data File Version 1.0.0 2025; GESIS: Cologne, Germany, 2023.

- GESIS–Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. Eurobarometer 99.1, GESIS Study Number ZA7954–Read Me 2025; GESIS: Cologne, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, J.W. Attitudes Toward Animal Use. Anthrozoos 1992, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, S.; Cassaday, H.J. Attitudes to Animal Use of Named Species for Different Purposes: Effects of Speciesism, Individualising Morality, Likeability and Demographic Factors. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, R.S.E.; Irene, C.; Laura, A.B.; Steve, L.; Faical, A.; Turner, S.P. Belief in Pigs’ Capacity to Suffer: An Assessment of Pig Farmers, Veterinarians, Students, and Citizens. Anthrozoos 2020, 33, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.; Dos-Santos, M.; Cocksedge, J. Attitudinal and Behavioural Differences towards Farm Animal Welfare among Consumers in the BRIC Countries and the USA. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A Systematic Review of Public Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours towards Production Diseases Associated with Farm Animal Welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.E.; González-Montaña, J.R.; Lomillos, J.M. Consumers’ Concerns and Perceptions of Farm Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.C.; Williams, J.M. The Challenges and Future Development of Animal Welfare Education in the UK. Anim. Welf. 2021, 30, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.; Stokes, J.E.; Morgans, L.; Manning, L. The Social Construction of Narratives and Arguments in Animal Welfare Discourse and Debate. Animals 2022, 12, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, R.S.; Mounk, Y. The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect. J. Democr. 2016, 27, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollebergh, W.A.M.; Iedema, J.; Meuss, W. The Emerging Gender Gap: Cultural and Economic Conservatism in the Netherlands 1970–1992. Polit. Psychol. 1999, 20, 291–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. In The Gap Between Rich and Poor; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Upreti, G. Satisfaction of Human Needs and Environmental Sustainability. In Ecosociocentrism: The Earth First Paradigm for Sustainable Living; Upreti, G., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 111–135. ISBN 978-3-031-41754-2. [Google Scholar]

- Frontuto, V.; Felici, T.; Andreoli, V.; Corsi, A.; Bagliani, M.M. Is There an Animal Food Kuznets Curve, and Does It Matter? Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2024, 14, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, Y. Does the Animal Welfare Kuznets Curve Hypothesis Hold for Japanese Canines? Camb. Open Engag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacke, L.; Riemann, R. Two Sides of the Same Coin? On the Common Etiology of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2023, 207, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, B. Enemies of Freedom: Understanding Right-Wing Authoritarianism; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 1555420974. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; ISBN 0521805406. [Google Scholar]

- Dhont, K.; Hodson, G. Why Do Right-Wing Adherents Engage in More Animal Exploitation and Meat Consumption? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 64, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffarth, M.R.; Azevedo, F.; Jost, J.T. Political Conservatism and the Exploitation of Nonhuman Animals: An Application of System Justification Theory. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2019, 22, 858–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hus, A.; McCulloch, S.P. The Political Salience of Animal Protection in the Netherlands (2012–2021) and Belgium (2010–2019): What Do Dutch and Belgian Political Parties Pledge on Animal Welfare and Wildlife Conservation? J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2023, 36, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.K.; McGrath, N.; Nilsson, D.L.; Waran, N.K.; Phillips, C.J.C. The Role of Gender in Public Perception of Whether Animals Can Experience Grief and Other Emotions. Anthrozoos 2014, 27, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender Differences in Human–Animal Interactions: A Review. Anthrozoos 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgerber, H. Real Men Don’t Eat (Vegetable) Quiche: Masculinity and the Justification of Meat Consumption. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2013, 14, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A.; Milfont, T.L. Why Are Women Less Likely to Support Animal Exploitation than Men? The Mediating Roles of Social Dominance Orientation and Empathy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 129, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Adan, A.; Antofie, M.-M.; Arrona-Palacios, A.; Candido, M.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Chandrakar, P.; Demirhan, E.; Detsis, V.; Di Milia, L. Animal Welfare Attitudes: Effects of Gender and Diet in University Samples from 22 Countries. Animals 2021, 11, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.; Jaeger, B.; Domingues, I. Perceptions of Farm Animal Sentience and Suffering: Evidence from the BRIC Countries and the United States. Animals 2022, 12, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.; Vrij, A.; Cherryman, J.; Nunkoosing, K. Attitudes towards Animal Use and Belief in Animal Mind. Anthrozoos 2004, 17, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.; Izmirli, S.; Aldavood, J.; Alonso, M.; Choe, B.I.; Hanlon, A.; Handziska, A.; Illmann, G.; Keeling, L.; Kennedy, M. An International Comparison of Female and Male Students’ Attitudes to the Use of Animals. Animals 2010, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, F.; Lee, N.; Morrow, E.R. Faith No More? The Divergence of Political Trust between Urban and Rural Europe. Political Geogr. 2021, 89, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.; Dos-Santos, M.J.P.L. European Citizens’ Evaluation of the Common Agricultural Policy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.; Cano-Díaz, C.; Jesus, M. The European Citizens’ Stance on the Sustainability Subsidies Given to The EU Farmers. Eur. Countrys. 2024, 16, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šostar, M.; Ristanović, V. Assessment of Influencing Factors on Consumer Behavior Using the AHP Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M.; Luca, D. The Urban-Rural Polarisation of Political Disenchantment: An Investigation of Social and Political Attitudes in 30 European Countries. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2021, 14, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Maurice Broom, D.; Orihuela, A.; Velarde, A.; Napolitano, F.; Alonso-Spilsbury, M. Effects of Human-Animal Relationship on Animal Productivity and Welfare. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2020, 8, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J.-L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The Power of a Positive Human–Animal Relationship for Animal Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; McGreevy, P. What We Know about the Public’s Level of Concern for Farm Animal Welfare in Food Production in Developed Countries. Animals 2016, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D. Effects of Human Contact on Animal Health and Well-Being. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1999, 215, 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I. Review of Human-Animal Interactions and Their Impact on Animal Productivity and Welfare. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Hansart, C.; Su, B. Attitudes of Young Adults toward Animals—The Case of High School Students in Belgium and The Netherlands. Animals 2019, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, P.; Tunnicliffe, S.D. Effects of Having Pets at Home on Children’s Attitudes toward Popular and Unpopular Animals. Anthrozoos 2010, 23, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bump, J. Biophilia and Emotive Ethics: Derrida, Alice, and Animals. Ethics Environ. 2014, 19, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R.; Costa, A.; Megías-Robles, A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Faria, L. Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Empathy towards Humans and Animals. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arney, D.; Piirsalu, P. The Ethics of Keeping fur Animals, the Estonian Context. In Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences; De Gruyter Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; Volume 71, p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, R. The Ethical Implications of the Human-Animal Bond on the Farm. Anim. Welf. 2003, 12, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaczyńska-Raczak, M. Using by Pro-Animal Organizations EU and National Legislative Tools to Outlaw the Breeding. Adm. Law. Rev. 2024, 8, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Hopwood, C.J.; Graça, J.; Nissen, A.T.; Dillard, C.; Thompkins, A. Exploring Public Support for Farmed Animal Welfare Policy and Advocacy across 23 Countries. Psychol. Hum.-Anim. Intergroup Relat. 2024, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).