Abstract

This study numerically investigates pavement damage caused by explosions in buried leaking natural gas pipelines using a coupled Lagrangian–Eulerian (CLE) framework in LS-DYNA. The gas phase is described by a Jones–Wilkins–Lee-based equation of state, while soil and pavement are modeled using a pressure-dependent soil model and the Riedel–Hiermaier–Thoma concrete model with strain-based erosion, respectively. The approach is validated against benchmark underground explosion tests in sand and blast tests on reinforced concrete slabs, demonstrating accurate prediction of pressure histories, ejecta evolution, and crater or damage patterns. Parametric analyses are then conducted for different leaked gas masses and pipeline burial depths to quantify shock transmission, soil heave, pavement deflection, and damage evolution. The results indicate that the dynamic response of the pavement structure is most pronounced directly above the detonation point and intensifies significantly with increasing total leaked gas mass. For a total leaked gas mass of 36 kg, the maximum vertical deflection, the peak kinetic energy, and the peak pressure at the bottom interface at this location reach 148.46 mm, 14.64 kJ, and 10.82 MPa, respectively. Moreover, a deflection-based index is introduced to classify pavement response into slight (<20 mm), moderate (20–40 mm), severe (40–80 mm), and collapse (>80 mm) states, and empirical curves are derived to predict damage level from leakage mass and burial depth. Finally, the effectiveness of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) strengthening schemes is assessed, showing that top and bottom surface reinforcement with a total CFRP thickness of 2.67 mm could reduce vertical deflection by up to 37.93% and significantly mitigates longitudinal cracking. The results provide a rational basis for safety assessment and blast resistant design of pavement structures above buried gas pipelines.

1. Introduction

Buried natural gas pipelines constitute an important part of urban lifeline systems, but are prone to deformation, fatigue and rupture when subjected to inadequate protection, shallow burial or external disturbance [1]. Once leakage occurs, ignition may trigger a vapor cloud explosion (VCE) that affects both underground utilities and surface transport infrastructure. Historical incidents have shown that such explosions frequently induce pavement cracking, local uplift and service interruption in densely built-up areas [2,3]. These observations underscore the need to clarify how blast loads generated within buried pipelines propagate through the surrounding soil and translate into damage of overlying pavement structures. Recent synthesis studies on blast effects on buried infrastructures further emphasize that reliable damage assessment requires explicit consideration of the coupled interaction among the explosion source, surrounding ground, and receiving structures [4].

To analyse pipeline explosion disaster, a variety of theoretical and semi-empirical models have been developed for characterizing VCE loads initiated by leaked natural gas [5,6,7]. Representative approaches include spherical and hemispherical flame models [8,9,10,11], the multi-energy method developed by TNO [12,13], and the TNT equivalent method [14,15]. Among these, the TNT equivalent method provides a practical way to estimate explosion intensity by equating the combustion energy of the gas to an equivalent TNT charge. Such models are widely used to determine peak overpressure and impulse envelopes, and thus supply essential input for preliminary design and safety assessment. However, they do not describe how shock waves propagate in layered soil deposits, interact with buried structures, and transform into complex stress and deformation fields within pavement systems. This limitation is particularly critical for shallow urban pipelines, where the coupling between gas, soil and pavement governs the actual extent of surface damage. In addition to these simplified load characterizations, numerical blast-load modeling has been shown to be essential in complex environments where wave reflection, confinement, and geometric shielding influence the loading history [16]. Recent computational investigations have also employed computational mechanics-based approaches to predict pipeline response under different blast scenarios, further indicating the need for physics-consistent load representation beyond empirical prescriptions [17].

The transmission of explosion loads through soil is strongly influenced by pipeline material, burial depth, leakage geometry and surrounding stratigraphy. Previous research has examined explosion behavior in pipelines made of different materials [18,19] and the dynamic response of buried pipelines subjected to blast or impact loading [20,21]. In leakage scenarios, natural gas can accumulate within soil voids, utility tunnels or pavement discontinuities, and ignition generates high-pressure shock waves that propagate upwards. Numerous studies have also focused on such effects of explosions on buildings and adjacent underground pipelines [22,23]. Nonetheless, investigations dedicated to pavement structures above leaking pipelines remain limited. Existing studies, such as that by Yang et al. [24], have analysed pavement deformation induced by pipeline explosions; however, the progressive evolution of damage and detailed failure patterns were not examined, and the coupled gas–soil–pavement interaction was only partially represented. Related numerical investigations have focused on the response of buried pipelines subjected to surface blast loading, highlighting the sensitivity of structural response to standoff distance and burial conditions [25]. In addition, studies on confined explosions and their effects on neighboring buried structures, including tunnel explosion scenarios, have demonstrated that confinement and waveguiding mechanisms can significantly modify both the spatial extent and intensity of transmitted blast loads [26].

Experimental studies on blast-resistant concrete structures also provide valuable insight into the behavior of pavement slabs subjected to intense transient loading. Tests on soil-supported concrete slabs have reported characteristic flexural and punching failure modes and indicated that soil stiffness exerts a limited influence on slab rupture once a critical impulse is exceeded [27]. Other experiments have demonstrated the enhanced blast resistance of ultra-high-performance concrete [28] and the beneficial effects of fiber reinforcement on crack control and energy dissipation [29]. Nevertheless, full-scale or large-scale blast tests involving buried explosions and pavement systems are costly, difficult to instrument and hard to repeat systematically. These constraints have motivated extensive use of numerical simulation tools, such as LS-DYNA and AUTODYN [30,31,32], which can incorporate nonlinear constitutive models, strain-rate effects and blast–soil–structure interaction within a unified computational framework. Beyond pavement and slab tests, validated blast simulations for other infrastructure components, such as cylindrical thin-shell systems, further demonstrate the value of robust numerical frameworks for establishing response trends and design-relevant metrics under varying blast conditions [33].

Parallel to these developments, data-driven and machine-learning-based approaches have been introduced to support prediction of structural response and performance under blast loading [34]. While these methods offer efficient surrogate models once sufficient training data are available, they do not replace the need for physics-based simulations, especially when new loading scenarios or structural configurations are considered. In particular, they are less suited to reveal the detailed mechanisms of energy transfer, wave propagation, soil heave and cracking that control pavement damage above buried pipelines. Continuum-based numerical approaches therefore remain indispensable for understanding the coupled processes associated with leakage-induced pipeline explosions. However, existing literature still provides limited treatment of the progressive damage mechanisms in pavement slabs under underground explosion loading, and systematic damage classification and mitigation strategies for such systems are scarce.

To address the identified research gaps, this study establishes a coupled arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian (ALE) and Lagrangian numerical framework to simulate the dynamic response of pavement structures subjected to buried natural gas pipeline explosions. The framework employs a multi-material ALE formulation for modeling the explosive gas, described by a Jones–Wilkins–Lee (JWL) equation of state, while the surrounding soil and pavement concrete are simulated using Lagrangian meshes with a pressure-dependent constitutive model and the Riedel–Hiermaier–Thoma (RHT) model with strain-based erosion, respectively. The main novelties and contributions of this work are threefold. First, the proposed fully coupled gas–pipeline–soil-pavement framework is developed to accurately capture the complex fluid–structure interaction during underground explosions. Second, its validity and accuracy are rigorously demonstrated through comparisons with benchmark underground explosion tests in sand and experimental results from concrete slab blast experiments. Third, a series of parametric analyses is conducted using a typical pipeline–soil–pavement configuration to elucidate the effects of critical factors, including gas leakage mass and pipeline burial depth, on energy transfer mechanisms, deformation patterns, and damage evolution. Furthermore, the effectiveness of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) strengthening schemes for pavement mitigation is quantitatively evaluated. Based on the numerical results, this study subsequently proposes deflection-based damage assessment criteria and establishes empirical damage prediction curves, which provide practical tools for the performance evaluation and protective design of pavements against such blast hazards. This research gap has also been noted in recent reviews focusing on blast effects on buried infrastructures [35].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 formulates the coupled gas–pipeline–soil–pavement problem and introduces the governing equations, constitutive models and loading conditions within the ALE–Lagrangian framework. Section 3 describes the numerical model setup, including validation against benchmark tests, configuration of the gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system and mesh sensitivity analysis. Section 4 presents the numerical results, focusing on the global dynamic response, displacement and pressure fields, damage evolution, deflection-based damage assessment and the mitigation effect of CFRP strengthening, and lastly, Section 5 summarizes the main findings.

2. Formulation of the Gas–Pipeline–Soil–Pavement Coupled Problem

This Section formulates the coupled problem of gas explosion, pipeline response, soil deformation and pavement damage within a unified numerical framework. The physical system is represented by a Eulerian description for the leaking and exploding gas, and a Lagrangian description for the buried pipeline, surrounding soil and overlying pavement. On this basis, the governing equations for the gas and solid subdomains, the interface conditions, the constitutive models and the loading and boundary conditions are introduced.

2.1. Overview of the Coupled ALE–Lagrangian Framework

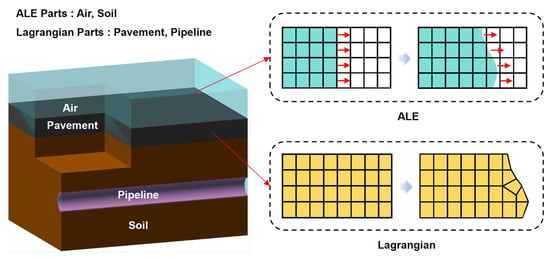

The numerical model is constructed to capture the interaction between the leaking gas, the buried pipeline, the surrounding soil and the pavement under an internal explosion. The computational domain is decomposed into two interacting subdomains (see Figure 1). The explosion gas within the leakage cavity, the soil layers and the surrounding air are represented in a Eulerian frame using a multi-material ALE formulation, which permits large deformation, advection and possible venting of the gas without mesh distortion. The pipeline and pavement slab are described in a purely Lagrangian form, so that stress development, permanent deformation and damage in the structural components can be followed explicitly in time.

Figure 1.

Numerical description adopted for each part of the gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system.

The Eulerian subdomain is centered on the leakage region around the pipeline where combustible gas accumulates prior to ignition. Within this region, the evolution of gas density, pressure and velocity is governed by the conservation laws of compressible flow, complemented by an appropriate equation of state for the combustible gas or explosion products. The ALE mesh covers both the initial leakage cavity and a surrounding buffer zone, so that the rapid expansion of the gas and its interaction with the cavity walls, the pipe surface and any rupture openings can be resolved with sufficient spatial resolution.

The Lagrangian subdomain extends vertically from the pavement surface to a depth at which the explosion-induced stress waves have essentially attenuated, and laterally to several times the pipe burial depth. This configuration limits artificial reflections from the model boundaries and ensures that the zone of interest around the pipeline and pavement is not contaminated by boundary effects within the time window considered. The pavement structure, backfill, native soil and pipeline are discretized as distinct material regions, allowing differences in stiffness, strength and energy dissipation to be represented explicitly.

Coupling between the gas and solid domains is realized through an embedded ALE–Lagrangian interface algorithm. At each time step, the gas pressure and momentum flux acting on the gas–pipeline, gas–soil and gas–pavement interfaces are transferred to the adjacent Lagrangian elements as equivalent surface tractions, while the motion of the solid boundaries updates the effective geometry seen by the Eulerian mesh. In this way, the explosion-induced pressure loading, stress–wave transmission in the soil and the subsequent redistribution of stresses within the gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system are treated in a consistent manner. This coupled ALE–Lagrangian framework forms the basis for the governing equations, constitutive models and boundary conditions introduced in the following subsections.

2.2. Governing Equations for Gas, Pipeline, Soil and Pavement

The coupled response of the gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system is governed by the conservation of mass and momentum in both the gas phase and the solid skeleton. In the Eulerian gas domain, the conservation of mass (Equation (1)) describes the evolution of gas density as the explosion products expand, impinge on the cavity wall and interact with the surrounding ground. The conservation of momentum (Equation (2)) relates the temporal change in gas momentum to the divergence of the momentum flux, the pressure gradient and body forces, such as gravity. The governing equations are written as

where is the density, is the displacement, is the stress and is the body force. Combined with an appropriate equation of state that links gas pressure, density and internal energy, as will be detailed in Section 2.3, these equations reproduce the rapid build-up and subsequent decay of explosion pressure in the leakage cavity and along the gas–solid interfaces.

In the Lagrangian solid domain, which comprises the buried pipeline, the surrounding soil and the overlying pavement, the governing equation (Equations (3) and (4)) is the balance of linear momentum written in terms of the Cauchy stress tensor, body forces and material acceleration, written as

where and indicate the mass and volume, respectively, and indicates the acceleration.

The stress tensor is updated from the strain and strain rate through the constitutive models (Section 2.3), so that nonlinear, pressure dependent and rate sensitive behavior can be represented where necessary. For the pipe, an elastic–plastic formulation with kinematic hardening is adopted to capture large deformation and progressive yielding under internal blast loading. Kinematic relations between displacement, strain and strain rate follow standard assumptions in dynamic geotechnical analysis, and provide the link between the nodal degrees of freedom and the internal stress state in each solid phase.

On the gas–solid interfaces, traction continuity and kinematic compatibility are enforced. The normal component of the gas pressure acts as a boundary traction on the pipe wall, soil surface or pavement underside, whereas the motion of the solid boundary provides a moving interface for the Eulerian gas computation. In the present work, the conservation equations in the gas and solid subdomains are advanced in time using an explicit time integration scheme, with the global time step controlled by the smallest characteristic element size and the highest wave speed in either domain. These balance equations, together with the interface conditions, are closed by the material models and explosion loading descriptions introduced in Section 2.3 and Section 2.4, which define the complete gas–pipeline–soil–pavement coupled problem.

2.3. Constitutive Relations for Pipeline, Soil, and Pavement

2.3.1. Pipeline

The buried natural gas pipeline is made of polyethylene and is represented at the continuum level by an isotropic elastoplastic model based on the von Mises yield criterion. Under uniaxial loading, the stress–strain relation is idealized as a bilinear curve as expressed by [36]

where is the initial yield stress, is elastic modulus, is the tangent modulus, is strain, and is elastic limit strain, respectively. This idealization captures the dominant features of the in-plane response of polyethylene pipe under the combined action of internal gas pressure and external soil confinement, including the development of large elastic–plastic deformation and localized plastic hinges. Rate effects and pressure dependence of yielding are neglected, which is acceptable for the present focus on quasi-static residual deformation and damage patterns rather than detailed high-rate polymer behavior.

2.3.2. Soil

In high-strain-rate blast simulations, the Mohr–Coulomb model fails to capture dynamic effects, while the cap model is often overly complex and computationally inefficient. In contrast, the Soil–Foam model [36], by virtue of its polynomial equation of state, enables more accurate simulation of soil compressive response under extreme high pressures. Therefore, the Soil–Foam model is adopted to simulate the behavior of soil. It could capture the fluid-like mechanics of the soil in high pressure and high strain rates and has demonstrated utility in soil modeling applications. The soil is idealized as a pressure-dependent granular material with elastic volumetric response and ideal plastic deviatoric response. The stress tensor is decomposed into a hydrostatic part and a deviatoric part, and yielding in the deviatoric plane is controlled by the second invariant of the deviatoric stress tensor and the mean stress . The yield function takes the form given in

where , and are strength parameters. Within the elastic range, the soil stiffness is characterized by a shear modulus and a bulk modulus , which define the small-strain wave speeds and volumetric compressibility. Beyond initial yield, the deviatoric response follows an associated ideal plastic flow rule in the framework, while the volumetric response remains essentially elastic. This combination reproduces the fluid-like, pressure-dependent behavior of loose sand under high-strain-rate loading, and has been shown to provide a robust approximation for underground explosion problems.

2.3.3. Pavement

The concrete pavement is modeled using the Riedel–Hiermaier–Thoma (RHT) dynamic concrete model. In this model, the macroscopic strength envelope is described by three distinct limit surfaces, namely an elastic limit surface, a failure surface and a residual strength surface. These surfaces are expressed as functions of the hydrostatic pressure and the third invariant of the deviatoric stress tensor, and thus account for the dependence of strength on confinement and Lode angle. The three surfaces represent, respectively, the initial yield strength, the peak failure strength and the residual strength after severe damage, so that the concrete can still sustain a reduced level of load after cracking and crushing.

In the fully dense state, the volumetric response of concrete is described by a polynomial equation of state. Porosity effects are introduced through a compaction function, which modifies the volumetric behavior as the material is compressed. Assuming that concrete satisfies a linear polynomial relationship in the dense state, a porosity coefficient is introduced and a state equation that accounts for concrete porosity is obtained. Under compaction, this state equation is written in the form of

where ( represents compression in volume, represents expansion in volume); is the material density; is the specific internal energy; is the material parameter. In this way, the volumetric stiffness and strength of concrete vary consistently with the applied pressure.

In explicit dynamic simulations, severe deformation or distortion of Lagrangian elements can substantially reduce the critical time step, compromising computational efficiency and potentially leading to numerical instability. To ensure stable and accurate simulation of impact and blast events, erosion algorithms based on user-defined criteria are commonly employed [37,38,39]. In the present study, various erosion criteria were evaluated, and a geometric strain limit of 0.5 was adopted, which provides satisfactory numerical performance [40]. Element erosion is therefore triggered when the instantaneous geometric strain reaches the threshold defined in

Severely distorted elements are removed from the computation, while load transfer within the damaged region continues to be governed by the residual strength surface, thereby enabling a robust representation of cracking, spalling, and crushing in the pavement slab under blast loading. Owing to their high tensile strength and stiffness, CFRP materials are well suited for enhancing the blast resistance of concrete structures. By restraining crack opening, limiting tensile strain, and improving flexural capacity under dynamic loading conditions [41,42], CFRP reinforcement is therefore adopted in this study to strengthen the concrete pavement. CFRP layers are explicitly represented as thin shell elements and simulated using an enhanced composite damage constitutive model [36], allowing their stress development, deformation, and interaction with the concrete pavement to be captured directly.

2.4. Modeling of Air and Explosion-Induced Loading

The air within the leakage cavity and in the surrounding voids is modeled as an inviscid compressible medium described by a null-strength material coupled with an ideal-gas-type equation of state. In this formulation the Cauchy stress reduces to the hydrostatic pressure, and the pressure is related to the density and specific internal energy through

where is the gas pressure, is the adiabatic constant for air (taken as 1.4), is the current density and is the specific internal energy. The reference state is defined by the initial density of air at ambient conditions and a prescribed initial internal energy, so that the initial pressure in the air domain matches the atmospheric pressure.

The detonation of the leaked gas is represented by an explosive products region occupying the leakage cavity around the pipeline at the ignition time. The thermodynamic response of the explosion products is described by a Jones–Wilkins–Lee (JWL) equation of state [43], which relates the pressure to the specific internal energy and the current relative volume as

where is hydrostatic pressure; is the specific volume; is specific internal energy; , , , , ω are material constants. The terms and are the pressure coefficients, and are the principal and secondary eigenvalues, respectively. is the fractional part of the normal Tait equation adiabatic exponent. is a mathematical constant. These parameters are chosen to reproduce the pressure–time history and specific energy release of the leaked gas explosion, following established TNT-equivalence or gas-detonation data. At the instant of ignition, the pressure and internal energy in the explosive region are instantaneously raised to their detonation values, and the subsequent expansion of the products is governed by the JWL law and the conservation equations in the Eulerian gas domain.

The explosion-induced loading on the soil, pipeline and pavement arises from the propagation of the blast wave in the air-filled leakage cavity and its interaction with the surrounding solid boundaries. Within the coupled ALE–Lagrangian framework, the pressure field computed in the explosive and air domains is transferred at each time step to the gas–solid interface as a normal traction acting on the adjacent Lagrangian elements. The reflected and transmitted components of the blast wave are naturally captured by the combined solution of the gas and solid governing equations. The outer boundaries of the air domain are placed sufficiently far from the leakage cavity and equipped with non-reflecting or transmitting conditions, so that spurious wave reflections do not contaminate the pressure–time histories acting on the pavement and soil. In this way, the model resolves the full evolution of the explosion-induced loading, from the initial shock rise and peak overpressure to the subsequent decay and negative phase, and provides a consistent input for the analysis of gas–pipeline–soil–pavement interaction.

2.5. Numerical Implementation of the Coupled Model

The coupled gas–pipeline–soil–pavement problem is implemented in LS-DYNA (R14.0) using an explicit ALE–Lagrangian formulation. The explosion gas, soil layers and surrounding air are modeled by multi-material ALE elements, while the pavement and buried polyethylene pipe are discretized with Lagrangian solid elements. Time integration follows the central-difference scheme with an automatic critical time step governed by the smallest element size and highest wave speed. In the solid domain, reduced-integration elements with hourglass control are adopted to maintain stability, and limited bulk viscosity is introduced in the ALE domain to regularize pressure gradients near the shock front. A viscous hourglass control method was employed to mitigate spurious zero-energy deformation modes, which is suitable for simulating structural responses under blast loading. Furthermore, the hourglass energy was verified to remain well below 5% of the internal energy throughout the simulation, confirming the effectiveness of the adopted control approach.

Material behavior and equation of state are described by standard LS-DYNA models. Soil is represented by MAT_SOIL_AND_FOAM, and the polyethylene pipe by MAT_PLASTIC_KINEMATIC based on a bilinear von Mises response. Concrete pavement by MAT_RHT with a polynomial equation of state, with the MAT_ADD_EROSION keyword employed to simulate the erosion process. For the CFRP used to reinforce the pavement structure, the MAT_ENHANCED_COMPOSITE_DAMAGE model was adopted, which is considered appropriate for this simulation. The spatial distribution of the explosive is defined using the INITIAL_VOLUME_FRACTION_GEOMETRY, and the explosion products are modeled by MAT_HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_BURN coupled with EOS_JWL, while air is represented by MAT_NULL with an ideal-gas-type EOS. The coupling between the gas and solids is a critical feature of the adopted methodology. By modeling the air and explosive products explicitly using ALE elements, the blast load acting on the structure is generated naturally through the physical processes of detonation and subsequent wave propagation, rather than being prescribed via empirical formulas. This approach eliminates the uncertainty associated with estimating the magnitude, spatial distribution, and duration of the load, thereby ensuring greater accuracy in capturing the true loading process and structural response. This interaction is enforced computationally through the CONSTRAINED_LAGRANGE_IN_SOLID algorithm, which transfers pressures from the ALE domain to the Lagrangian structural surfaces and consistently updates the gas–solid interface in response to structural motion. Furthermore, strain-based erosion is activated for the concrete elements (and locally for the soil where necessary) to remove severely distorted elements and maintain computational robustness during the intense blast–soil–structure interaction.

It is noted that in the present coupled framework, the modeling assumptions adopted in the formulation and numerical implementation are selected based on the physical characteristics of near-field blast–soil–structure interaction and common engineering practice, with the aim of balancing physical fidelity and computational feasibility. The credibility of these assumptions is supported through validation at three levels. At the theoretical level, the governing conservation laws and constitutive formulations employed are standard and well established for high-strain-rate blast applications. At the numerical level, the coupled ALE–Lagrangian implementation is verified against published benchmark tests, including underground explosions in sand and blast tests on concrete slabs, showing good agreement in pressure histories, deformation patterns, and damage modes. At the application level, the framework is further exercised under representative buried gas pipeline explosion scenarios to confirm physically consistent response trends and damage evolution for the problem addressed. Nevertheless, the present framework still involves several simplifying assumptions and modeling choices that may influence the results under certain conditions. These aspects are explicitly discussed in the following Sections and are identified as directions that warrant further extension and in-depth investigation in future work. Despite these limitations, the proposed approach is expected to provide a useful reference for simulating near-field buried pipeline explosion scenarios and to offer practical insights for subsequent methodological development and engineering applications.

3. Numerical Model Setup and Validation

This Section first verifies the numerical framework against two representative benchmark problems, namely an underground explosion in dry sand and a close-in blast test on a reinforced concrete slab, to ensure that blast wave propagation, soil response and concrete damage are captured with sufficient accuracy. On this basis, a three-dimensional coupled ALE–Lagrangian model of the gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system is established in LS-DYNA, including model geometry, boundary conditions, mesh arrangement and material parameters. Finally, the mesh sensitivity analysis and key modeling choices are summarized, providing the foundation for the subsequent parametric studies on explosion-induced pavement damage.

3.1. Validation of Buried Explosion in Dry Sand

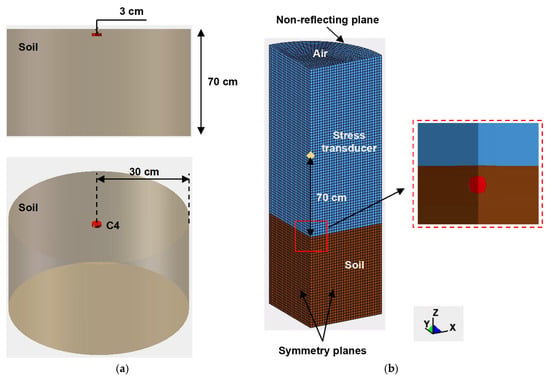

To assess the capability of the numerical framework to reproduce blast wave propagation and soil ejecta induced by buried explosions, a benchmark underground explosion test reported by Materials Sciences Corporation [44] is simulated using LS-DYNA. In the experiment, a cylindrical explosive charge with a diameter of 6.4 cm and a thickness of 2 cm was embedded in dry quartz sand at a depth of 3 cm below the ground surface inside a cylindrical container with a thickness of 70 cm and a diameter of 60 cm (see Figure 2). A stress transducer was positioned 70 cm above the sand surface to record the time history of blast-induced pressure. The sand, which was also used in the plate impact tests conducted by Chapman et al. [45]. Exploiting symmetry, a quarter three-dimensional finite element model of the soil container and surrounding air is constructed. The computational domain is discretized using 67,500 eight-node solid (hexahedral) elements with an average mesh size of about 10.0 mm. Symmetry boundary conditions are applied on the two vertical planes, whereas non-reflecting boundaries are assigned to the outer faces of the air domain to minimize spurious wave reflections. To reproduce the confinement of the experimental container and prevent material outflow, normal displacements on the external soil surfaces are constrained. This validation case adopts C4 explosive, with the main material parameters given as: equation of state coefficients = 609.97 GPa, = 12.95 GPa, = 4.5, = 1.4, and = −0.25. All other material parameters are identical to those specified in the main numerical example will later be described in Section 3.3 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Experimental and numerical simulation setup of the buried explosion test in dry sand: (a) arrangement of measuring points; (b) finite element model.

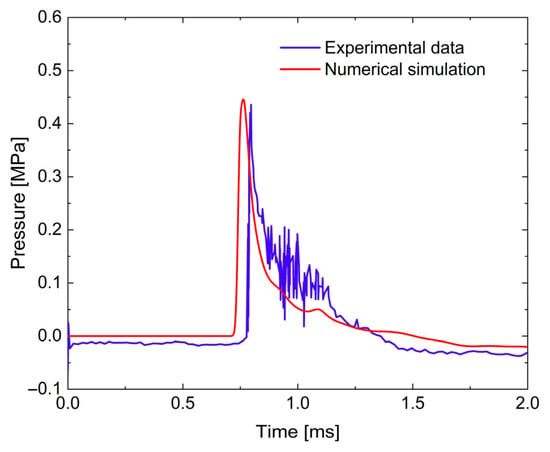

Figure 3 compares the simulated and measured pressure–time histories at the monitoring point. The calculated stress wave arrives at approximately 0.7 ms, followed by a rapid rise to a peak pressure of 0.445 MPa at about 0.76 ms, and then a gradual decay into a negative phase. This evolution reflects the transient confinement provided by the overlying soil, whose wave impedance is much higher than that of air. As the shock front propagates upward, energy dissipation in the soil remains relatively slow, while rarefaction waves that develop behind the front give rise to the subsequent negative phase as the wave enters the air domain. The difference between the numerical and experimental peak pressures is about 0.007 MPa, and the small phase shift in arrival time is negligible for engineering applications, indicating that the main features of blast wave propagation are accurately captured.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of measured and calculated pressure for the buried explosion test in dry sand (experimental data from [44]).

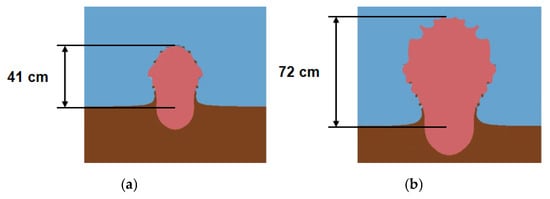

The kinematics of the soil ejecta provide an additional validation metric. Figure 4 presents snapshots of the ejecta profile obtained from numerical simulations at 420 and 830 after detonation, where the experimental results could be found in [44]. The blast-induced deformation of the soil around the charge accelerates the overburden and generates a characteristic ejecta plume. The measured ejecta heights at these two times are approximately 45 cm and 75 cm, respectively, whereas the simulated heights are slightly smaller, resulting in relative errors of 8.89% and 4.00%. Despite this modest underestimation, the numerical results reproduce the observed evolution of the ejecta front and the overall plume shape with good fidelity, indicating that the adopted soil model and ALE formulation can represent the complex soil–blast interaction.

Figure 4.

Simulation snapshots of soil ejecta heights for the buried explosion test in dry sand (experimental results could be found in [44]): (a) Time = 420 μs; (b) Time = 830 μs.

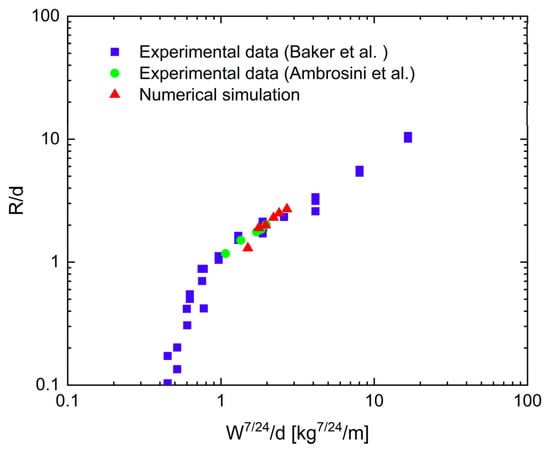

A further validation concerns the formation of craters and subsurface cavities generated by buried spherical charges. Under a buried explosion, soil in the vicinity of the charge is crushed and compacted radially outward, forming a cavity and, at shallow burial depths, an apparent surface crater. The crater size and geometry depend mainly on explosive weight, burial depth and soil resistance. Baker et al. [46] proposed an empirical relation for apparent crater radius in terms of scaled crater radius and scaled charge weight, based on dimensional analysis and a large number of field tests, as expressed by

where represents the apparent crater radius, denotes the burial depth of the explosive, signifies the weight of the explosive, stands for the soil strength factor, and is defined as the gravitational effect factor. It is argued by Luccioni et al. [47] that serves as the optimal metric for and is identified as the most suitable measure for , where representing the seismic velocity in the soil. The experimental data reveal that when plotting the scaled crater radius against the scaled charge weight , the resulting curve exhibits consistency with the experimental results obtained from a series of field tests. Luccioni et al. [47] also demonstrated that the scaled crater radius is an appropriate measure of apparent crater size and that a seismic-velocity-based parameter provides a suitable index of soil resistance. When experimental data are plotted as scaled crater radius versus scaled charge weight, data from different tests collapse onto a single curve, indicating good similarity.

Within the present framework, a series of simulations is carried out for spherical charges with different burial depths and explosive weights. For each case, the apparent crater radius obtained from the numerical results is converted into scaled form and plotted against the corresponding scaled charge weight. As shown in Figure 5, the numerical predictions follow the experimental trend closely and lie within the scatter band of field test data [46,48]. This agreement confirms that the ALE formulation, material models and boundary conditions adopted in this study can reliably reproduce key features of buried explosion phenomena, including pressure histories, soil ejecta and crater formation, and provide a sound basis for the subsequent simulations of gas pipeline explosions beneath pavement structures.

Figure 5.

Comparison of crater diameter with scaled distance for the buried explosion test in dry sand (experimental data from [46,48]).

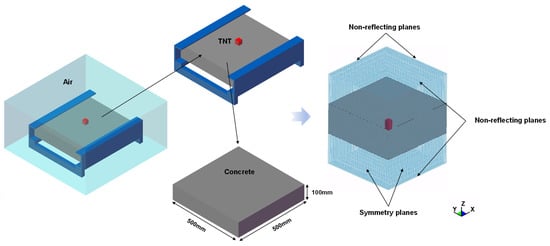

3.2. Validation of Concrete Slab Damage Under Blast Loading

The adopted material models and coupled ALE–Lagrangian formulation are further validated against blast tests on concrete slabs reported by Zhao et al. [49]. The model employs ALE elements for the air and Lagrangian elements for the concrete slab. The interaction between them is governed by CLE approach. In the reference experiment, a concrete slab with plan dimensions of 500 mm × 500 mm and a thickness of 100 mm was subjected to a 50 g explosive charge detonated in direct contact with the slab surface under fully fixed boundary conditions (see Figure 6). The computational domain is discretized into 550,000 eight-node solid elements with an average mesh size of about 5.0 mm. The test exhibited severe spalling and crater formation on both faces, but no complete perforation, providing a stringent benchmark for predicting concrete damage under close-in blast loading. Following the experimental configuration, a quarter-symmetry three-dimensional model of the slab and surrounding air is constructed in LS-DYNA. Displacement constraints along the outer edges reproduce the fixed supports, symmetry conditions are imposed on the two vertical planes, and non-reflecting boundaries are applied on the outer air surfaces to suppress artificial wave reflections. The explosive charge is defined in the air immediately adjacent to the slab. Concrete is represented by the RHT model with an appropriate equation of state, air by a null-strength material with an ideal-gas-type equation of state, and the CLE approach is used to capture interaction between detonation products and the deforming slab. The material parameters are identical to those specified in the main numerical example and will later be described in Section 3.3 (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Experimental and numerical setup for the concrete slab damage test under blast loading.

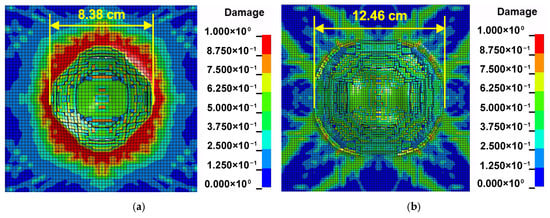

Figure 7 presents the simulated damage patterns on the top and bottom faces, where the experimental results could be found in [49]. In the tests, conical craters formed on both surfaces, with measured diameters of approximately 8 cm on the blast face and 12 cm on the rear face. The numerical model reproduces these features, predicting crater diameters of 8.38 cm and 12.46 cm, corresponding to relative errors of 4.75% and 3.83%, respectively. The simulation also captures the extent of spalling, scabbing and the absence of full perforation. This close agreement in crater size and damage morphology indicates that the combined use of the CLE formulation and the RHT concrete model can reliably represent blast-induced cracking, spalling and scabbing in concrete slabs, and thus forms a sound basis for subsequent simulations of pavement structures subjected to underground gas pipeline explosions.

Figure 7.

Comparison of numerically predicted damage patterns of the concrete slab with experimentally observed failure modes reported in the literature: (a) top and (b) bottom surfaces (experimental results could be found in [49]).

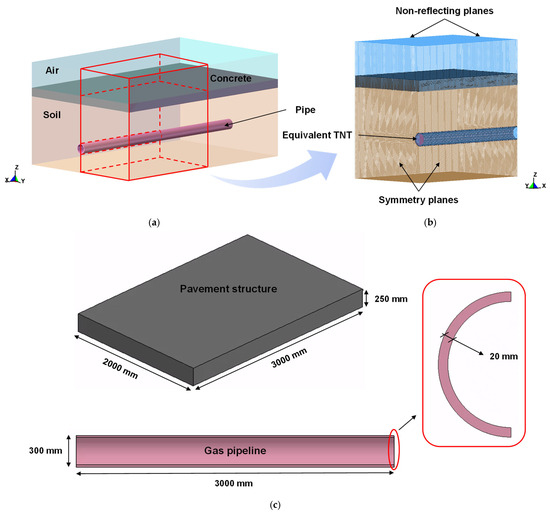

3.3. Setup of the Gas–Pipeline–Soil–Pavement Simulation

The validated numerical framework is then applied to a representative gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system to investigate explosion-induced pavement response. The configuration follows a typical urban concrete pavement with an underlying distribution pipeline (see Figure 8). The pavement slab is made of C30 concrete, with a width of 4.0 m and a thickness of 0.25 m, and is supported by a compacted soil foundation. The natural gas pipeline is modeled as a polyethylene pipe with an outer diameter of 300 mm and a wall thickness of 20 mm. The pipe crown is located at a depth of 1.15 m below the pavement surface. The surrounding soil domain is extended laterally and vertically such that reflections from artificial boundaries do not interfere with stress and deformation in the region of interest around the pipe and pavement.

Figure 8.

Numerical model of the pipeline–soil–pavement system under gas pipeline explosion: (a) schematic diagram of the model, (b) finite element model, (c) dimensions of the pavement structure and gas pipeline.

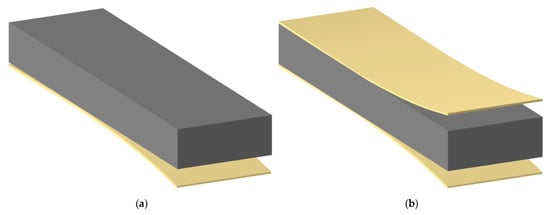

Two CFRP strengthening schemes were examined in this work, as presented in Figure 9. These comprise bottom-face strengthening (Case 1) and combined strengthening applied to both the top and bottom faces (Case 2). Commercial CFRP products typically have a single-layer thickness of 0.167 mm, and previous investigations [50,51] have shown that stacking multiple layers can significantly improve blast resistance. The present study therefore compares the two schemes for a range of total CFRP thicknesses, with the aim of identifying an efficient reinforcement configuration.

Figure 9.

Illustration of the CFRP reinforcement schemes: (a) Case 1 (bottom surface reinforcement); (b) Case 2 (top and bottom surface reinforcement).

To reduce computational cost while retaining the essential three-dimensional characteristics, a quarter-symmetry model is adopted. Symmetry planes are placed along the longitudinal and transverse mid-planes of the pavement–pipe system, with normal displacements constrained to enforce symmetry. The lateral outer boundaries of the soil are restrained in the horizontal direction to represent confinement by adjacent ground or roadside structures, whereas the bottom boundary is fully fixed to approximate the stiffness of the deeper subsoil. In the longitudinal direction, only axial displacement is constrained at the external faces, allowing realistic wave propagation and deformation along the pipe axis in the central zone. The explosion is represented by an equivalent TNT charge located at the pipe crown inside the leakage cavity, with the TNT mass determined from the total leaked gas mass using the method described in Section 2.4. The overburden load from the pavement and soil is not explicitly prescribed as an external force. Instead, it is implicitly accounted for through the application of gravity to all components and the contact interactions defined between the soil, pavement, and pipeline. This approach allows the confinement effect and the initial stress state to be naturally represented within the coupled ALE–Lagrangian formulation. The main material parameters of the numerical model are summarized in Table 1. The material parameters employed in the numerical model are the result of a rational selection process, ensuring they are carefully screened, cross-verified, and appropriately matched to the key physical mechanisms of the research problem. The main material parameters for each constitutive model are obtained from the references provided in the table and the additional parameters can be found in the corresponding references.

Table 1.

Material parameters used in the numerical model.

Table 1.

Material parameters used in the numerical model.

| Concrete [52] | Soil [53,54] | TNT [53] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.22 | (MPa) | 63.85 | (m/s) | 6930 | |

| 1.22 | (MPa) | 1064 | (GPa) | 21 | |

| 100 | 0, 0, 0.87 | A (GPa) | 373.8 | ||

| 0 | CFRP [55] | (GPa) | 3.747 | ||

| 1.4 | Elastic modulus (GPa) | 212.12 | 4.15 | ||

| 0.61 | Tensile strength (GPa) | 4.1 | 0.9 | ||

| 0.18 | Ultimate strain | 1.74% | 0.35 | ||

| 0.1 | Pipeline [56,57] | Air [58] | |||

| 0.6805 | (MPa) | 19.8 | (kg/m3) | 1.225 | |

| 0.0105 | (MPa) | 834.9 | 0.4 | ||

| (MPa) | 30 | (MPa) | 300.32 | (J/kg) | 2.5 × 105 |

The gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system is discretized using different finite element formulations tailored to the components’ material behavior and expected response. The pavement and pipeline are modeled with 8-node solid Lagrangian elements. In contrast, the explosive gas, soil, and surrounding air are modeled using multi-material ALE elements. The CFRP sheets are discretized using shell elements. The final model consists of 738,400 solid elements and 13,400 shell elements. Each node of the solid elements possesses three translational degrees of freedom. The shell formulation employs the Belytschko–Tsay element, where each node has three translational and two rotational degrees of freedom. This formulation is known for its computational efficiency and is generally considered a stable and effective choice for problems involving large deformations. A structured, locally refined mesh is adopted near the pipe and pavement (see Figure 8), where large stress and strain gradients are expected, and a gradually coarsening mesh is used away from this critical region to balance accuracy and efficiency. The characteristic element size in the high-gradient zone is set to 30 mm, as justified by the mesh sensitivity analysis in the subsequent subsection. Non-reflecting boundaries are applied on the outer faces of the Eulerian air domain to suppress artificial pressure reflections. The computational time of the model varies depending on the number of CPU cores used. When running on an 8-core CPU, the simulation takes approximately 20 h to complete.

3.4. Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

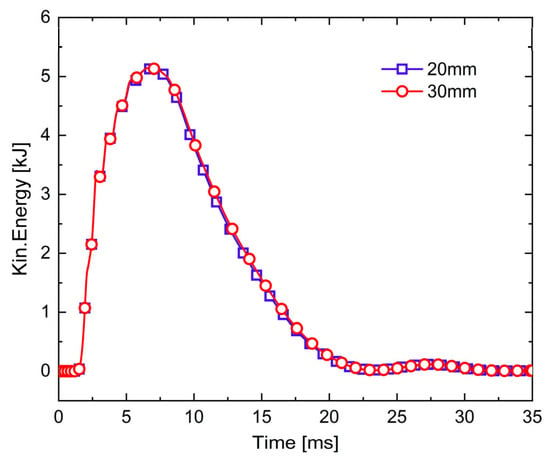

The spatial discretization of the coupled gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system has a direct influence on both the accuracy and stability of the simulations, particularly under highly transient explosion loading. In an explicit scheme, the critical time step is governed by the smallest element size and the highest local wave speed. An excessively fine mesh over the whole domain would therefore lead to prohibitively small timesteps and very high computational cost, whereas an overly coarse mesh would be unable to resolve stress–wave propagation, localized damage and permanent deformation in the vicinity of the pipe and pavement. A mesh sensitivity analysis is thus required to identify an element size that achieves an appropriate balance between accuracy and efficiency in the critical region.

The analysis focuses on the dynamic response of the pavement slab, which is the primary indicator of surface damage and serviceability. Several meshes with different characteristic element sizes in the pavement and adjacent soil are generated, while keeping the overall geometry, material models and boundary conditions unchanged. For each mesh, a representative explosion scenario is simulated and the time history of the total kinetic energy of the pavement slab is extracted. Under blast loading, the explosive energy is first converted into kinetic energy of the surrounding media and then dissipated through inelastic deformation and stress–wave attenuation. The evolution of the slab kinetic energy therefore provides an integrated measure of how well the mesh resolves the dominant dynamic processes.

Figure 10 compares the kinetic energy–time histories for meshes with characteristic element sizes of 20 mm and 30 mm in the high-gradient zone around the pipe and pavement. The two curves exhibit almost identical rise times, peak values and decay characteristics, with no noticeable phase shift in the arrival of the main pulse or spurious oscillations when refining the mesh from 30 mm to 20 mm. This indicates that the 30 mm mesh already captures the essential features of the structural response. Further refinement significantly increases the number of elements and the computational cost without a commensurate gain in accuracy. This finding is consistent with that reported by Yang et al. [50]. Accordingly, a characteristic element size of 30 mm in the critical zone, combined with a gradually coarsening mesh away from the pipe–pavement region, is adopted in all subsequent simulations and parametric studies.

Figure 10.

Kinetic energy–time history of the pavement structure with different mesh densities.

4. Results and Analysis

In this Section, the validated numerical model is employed to investigate the dynamic response and failure mechanisms of concrete pavement structures subjected to buried natural gas pipeline explosions. A parametric sensitivity analysis is conducted, focusing on the following key engineering variables: the total leaked gas mass, the pipeline burial depth, and the application of CFRP strengthening. These parameters directly govern the magnitude of the transmitted load and the subsequent structural response. The influence of the leaked gas mass on the global energy response, displacement and stress fields, damage patterns, and damage indices of the pavement is first quantified. Subsequently, the effects of burial depth and CFRP reinforcement are systematically examined. Based on the results, empirical relations for damage prediction are established.

4.1. General Dynamic Response of the Pavement System

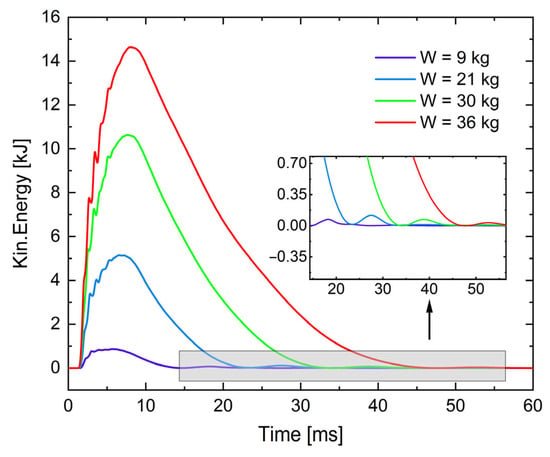

To begin with, the global evolution of kinetic energy in the coupled gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system is examined to characterize the overall dynamic response under different leakage scenarios. A natural gas leakage rate of 0.3 kg/s is considered, with leakage durations of 30 s, 70 s, 100 s and 120 s. The corresponding total leaked masses are 9 kg, 21 kg, 30 kg and 36 kg, respectively. Using the TNT equivalence method [15], the equivalent TNT charge weights are obtained as approximately 3.71 kg, 8.65 kg, 12.36 kg and 14.83 kg. For each scenario, the numerical model is used to evaluate the time history of the kinetic energy of the pavement system, so as to characterize the onset and duration of the dynamic response and to quantify the fraction of explosion energy transferred from the pipeline region to the pavement.

Figure 11 presents the evolution of the pavement structure’s kinetic energy over time for the four leakage scenarios. In all cases, the kinetic energy increases sharply following the arrival of the blast wave at the pavement level, peaks rapidly within a short duration, and then gradually decays to zero as structural vibrations are damped. Notably, the onset of the pavement response is largely independent of the total leaked gas mass, with a significant rise in kinetic energy consistently occurring at approximately t = 1.4 ms across all scenarios. This indicates that the propagation time of the main shock wave through the overlying soil is governed primarily by wave speed and burial depth, rather than by the magnitude of the explosion.

Figure 11.

Kinetic energy–time histories of the pavement structure for different total leaked gas masses.

In comparison, both the growth rate and peak value of the kinetic energy correlate strongly with the total mass of leaked gas. As increases, the equivalent TNT charge, the resulting peak overpressure, and the impulse transmitted to the soil and pavement all rise accordingly. Consequently, the kinetic energy of the pavement increases more rapidly, reaches a significantly higher peak, and remains elevated for a longer duration before decaying. This trend indicates that a greater proportion of the explosion energy is transferred into the vibrational and inelastic deformation modes of the pavement structure. Simultaneously, the rate of energy dissipation also increases with explosion magnitude, as more intense loading induces more extensive cracking, plastic deformation, and frictional sliding within the pavement and surrounding soil, thereby enhancing the overall damping of the system.

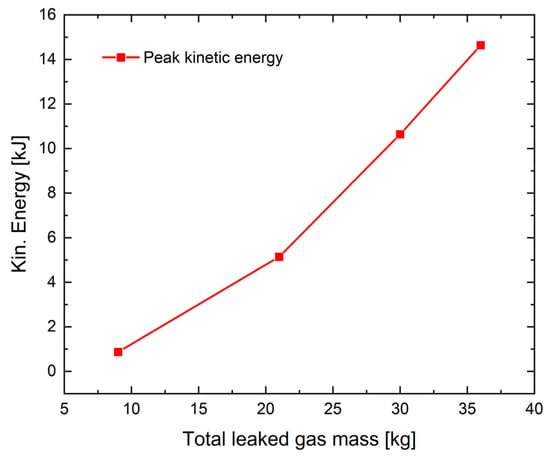

Figure 11 further reveals a secondary, smaller rise in kinetic energy subsequent to the decay of the primary response phase (see inset). Following the initial shock, the pavement slab is driven upward, partially separating from the underlying soil, which is heaved into an arched profile above the pipeline. As the upward motion is arrested and the slab rebounds under gravity, it oscillates downward and impacts the deformed soil surface. This intermittent contact between the recovering pavement and the uplifted soil generates secondary fluctuations in kinetic energy. Although the magnitude of this secondary peak is considerably lower than that of the primary response, it provides clear evidence of strong soil–structure interaction during the post-blast settlement phase and contributes to the development of residual deformation and surface damage. As a quantitative investigation, the first kinetic energy peak for the four working conditions of the pavement structure is compared in Figure 12. When the total leaked gas masses are 9 kg, 21 kg, 30 kg, and 36 kg, the corresponding first peaks are 0.88 kJ, 5.14 kJ, 10.64 kJ, and 14.64 kJ, respectively. As the mass of leaked gas increases, the first kinetic energy peak rises, and its growth rate gradually accelerates. This nonlinear amplification of kinetic energy indicates a progressively intensified dynamic demand on the pavement system, which is closely associated with the observed transition from localized damage to more extensive flexural deformation and surface cracking.

Figure 12.

Peak kinetic energy of pavement structure versus total leaked gas mass.

4.2. Vertical Displacement and Interface Pressure of the Pavement

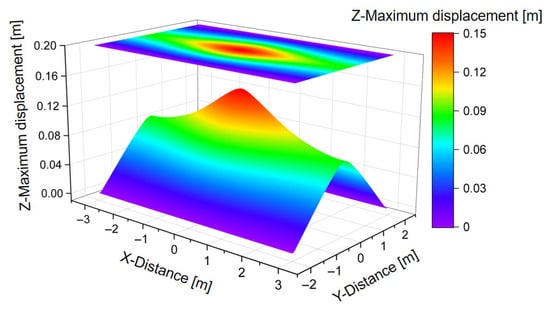

Next, local deformation and loading at the pavement level are examined in terms of the vertical displacement field and the pressure history at the pavement–soil interface. Figure 13 shows the distribution of the maximum vertical (Z-direction) displacement of the pavement structure for a total leaked natural gas mass of 36 kg. Under blast loading from the buried pipeline, the pavement experiences pronounced uplift, with a maximum vertical displacement of 148.46 mm occurring directly above the detonation center. Significant uplift is also observed toward both ends of the slab in the X-direction, where the maximum vertical displacement reaches 85.43 mm. After detonation, radial expansion and local failure of the pipe wall are first initiated at the ignition location, generating a spherical shock wave. This wave rapidly compresses the gas inside the pipeline along its axis and evolves into a cylindrical wave. Once the shock wave pressure exceeds the critical failure threshold of the pipe, progressive axial failure occurs, transferring the internal energy of the pressurized gas into the surrounding soil. The resulting soil heave and upward movement of the overlying soil layer drive the uplift of the pavement. The spatial variation in maximum Z-displacement is smooth, without abrupt gradients, indicating that localized damage has limited influence on the global deformation pattern of the pavement slab.

Figure 13.

Distribution of Z-maximum displacement of the pavement structure ( = 36 kg).

Owing to differences in loading intensity and boundary constraints, the resulting displacement patterns are direction-dependent. Figure 14 compares the maximum vertical displacements along the X- and Y-directions for different total leaked gas masses. The displacement distributions in both directions exhibit consistent shapes across all leakage scenarios. Along the X-direction (Figure 14a), the maximum vertical displacement gradually decreases from the center toward both ends, with the attenuation rate slowing as distance from the center increases. In contrast, the variation along the Y-direction (Figure 14b) is nearly linear from the center to the slab edges. A decrease in the total leaked gas mass reduces the explosion energy transmitted to the pavement, resulting in uniformly smaller uplift displacements across the slab. At the pavement center, the maximum vertical displacements are 11.88 mm, 48.63 mm, and 94.67 mm for total leaked masses of 9 kg, 21 kg, and 30 kg, respectively, confirming the strong sensitivity of the vertical response to explosion magnitude.

Figure 14.

Z-maximum displacement of the pavement structure: (a) variations along X direction, (b) variations along Y direction.

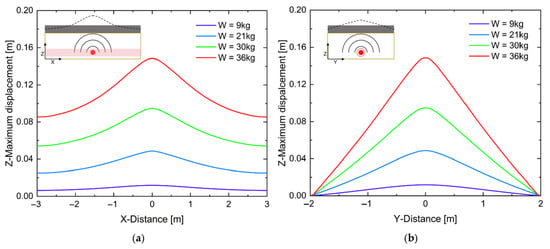

The results presented above indicate that the structural response of the pavement is predominantly concentrated in the vertical direction above the detonation center. To further clarify the local load-transfer mechanism at this critical location, Figure 15 presents the pressure–time history recorded at the bottom surface of the pavement directly above the detonation center. Following gas detonation, the blast-induced shock wave arrives at the bottom of the pavement at approximately t = 1.2 ms, with only minimal variation in arrival time across the different leakage scenarios. The pressure at the slab bottom then rises sharply to a peak value, the magnitude of which increases monotonically with the total leaked gas mass. Specifically, peak pressures of 3.26 MPa, 7.18 MPa, 8.76 MPa, and 10.82 MPa correspond to total leaked masses of 9 kg, 21 kg, 30 kg, and 36 kg, respectively.

Figure 15.

Pressure-time histories at the bottom surface of the pavement directly above the detonation center.

The pressure–time histories presented in Figure 15 indicate that the response of the pavement bottom surface to the blast shock wave can be categorized into three distinct stages: a positive loading phase, a reflected loading phase, and a free vibration phase. During the positive loading phase, the shock pressure rises rapidly to its maximum within a very short duration and then decays. The decay rate is faster for larger leaked gas masses, owing to stronger nonlinear attenuation within the soil–structure system. In the subsequent reflected loading phase, pronounced pressure oscillations occur at the pavement–soil interface, resulting in multiple stress peaks. This behavior arises from the separation of the uplifted pavement from the underlying soil, which generates a transmitted wave propagating upward toward the pavement top and a reflected wave returning downward into the soil. Because blast wave attenuation in soil is considerably slower than in air, the pavement bottom experiences a relatively prolonged duration of repeated pressure input. In the final free vibration phase, the direct influence of the blast pressure has effectively ceased. The motion of the pavement is then governed primarily by inertia, gravity, and contact forces resulting from intermittent impact between the slab and the heaved soil.

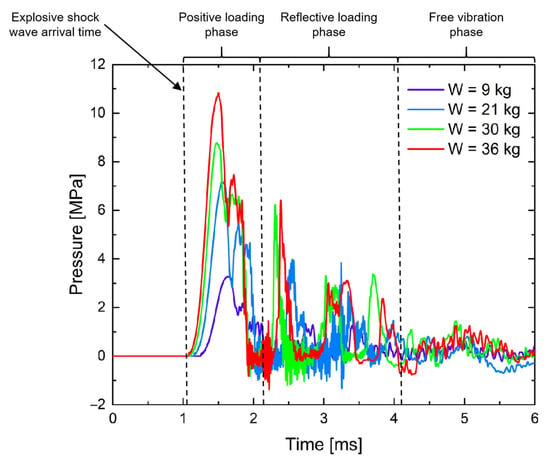

4.3. Damage Patterns and Failure Mechanisms of Pavement Slabs

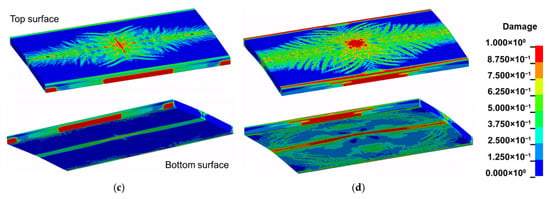

Building on the previous analysis of global dynamic response and interfacial loading, this Section examines the spatial distribution of damage and the underlying failure mechanisms within the pavement slabs. Figure 16 illustrates the temporal evolution of damage in the pavement structure for a total leaked gas mass of 36 kg. At t = 2 ms, the significant acoustic impedance contrast between air and concrete causes the compressive shock wave, reflected at the top surface, to convert into a tensile wave. The resulting tensile stresses exceed the dynamic tensile strength of the concrete, initiating damage at the top surface, as shown in Figure 16a. By t = 5 ms, this top-surface damage intensifies, while initial damage also emerges at the bottom surface and along the lateral faces (Figure 16b). Over time, the combined effect of the blast-induced pressure and the upward heave of the underlying soil induces pronounced flexural deformation in the slab. This bending causes the damage front to propagate from the top surface toward the bottom and outward along the longitudinal direction, progressively enlarging the damaged area and leading to through-thickness cracking in the central region.

Figure 16.

Damage evolution of the pavement structure for the case of leaked gas mass = 36 kg.

The explosion within the buried pipeline generates a cylindrical wave that propagates along the pipe axis. Pipeline failure transforms this wave into a distributed, non-uniform axial load applied beneath the pavement. When the resulting compressive stresses at the bottom of the slab remain below the concrete compressive strength, part of the load is carried by the residual stiffness of the bottom fibers. This mechanism leads to the formation of a longitudinal damage band rather than immediate perforation, as shown in Figure 16c–f. With increasing overall flexural deformation of the slab, damage within this longitudinal band accumulates and coalesces. By t = 35 ms, the longitudinal damage zone has propagated through the entire slab thickness, forming a continuous damaged region that connects the top and bottom surfaces (Figure 16e). At t = 60 ms, the deformation and damage patterns have largely stabilized, with only limited further extension of the existing cracks (Figure 16f).

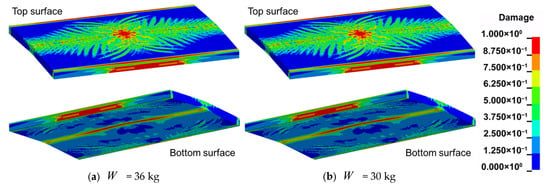

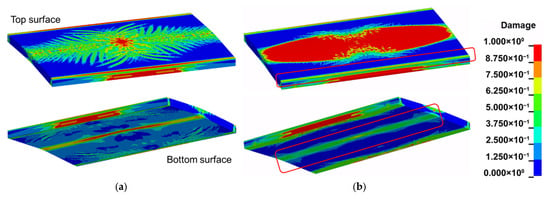

The influence of explosion intensity on pavement damage is examined in Figure 17, which compares the damage distributions at t = 60 ms for different total leaked gas masses (W). As W decreases, the global deformation of the slab is significantly reduced and the damaged area on the bottom surface contracts noticeably. These results indicate that damage on the pavement top surface is governed primarily by tensile wave effects, while the extent of through-thickness damage is strongly controlled by the level of blast energy transmitted from the pipeline. For W = 36 kg and W = 30 kg (Figure 17a,b), the longitudinal damage zone fully penetrates both the top and bottom surfaces, indicating severe flexural cracking and substantial stiffness loss in the central region. At W = 21 kg (Figure 17c), the longitudinal damage links the top and bottom surfaces only within a relatively confined central area, with moderate damage remaining on the bottom surface. The case W = 9 kg exhibits the mildest response: the longitudinal damage does not extend through the full thickness, and no significant bottom-surface damage is observed (Figure 17d). At this lower energy level, the kinetic energy imparted to the pavement is relatively low, and the response is dominated by local uplift near mid-span, with limited deformation along the longitudinal direction. Combined with the restraint provided by the transverse boundary conditions, this leads mainly to localized tensile damage near the bottom edges along both lateral sides, rather than to a continuous through-thickness failure band.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the damage of the pavement structure at T = 60 ms for the cases of different leaked gas masses. (Red circled region indicates high damage.)

4.4. Damage Indices and Prediction Model for Pavement Performance

The damage state of a pavement structure subjected to underground explosions is governed by multiple interacting factors, including explosion intensity and location, pavement configuration, and soil properties. In principle, damage can be evaluated using either qualitative or quantitative criteria [59]. However, qualitative descriptions are difficult to define objectively in numerical analyses. To address this, Fallah and Louca [60] proposed a quantitative assessment method in which tunnel structures are idealized as elastic–plastic single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) systems, and damage is classified according to the system deflection. This deflection-based criterion has been shown to be effective and has been adopted in several subsequent studies [50,53].

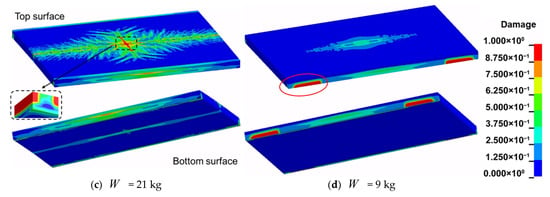

In the present work, the pavement structure predominantly experiences a global flexural failure mode under natural gas pipeline explosions. Considering the longitudinal continuity of the pavement, the maximum vertical deflection of the pavement cross-section is adopted as the criterion for quantitative damage assessment, as illustrated in Figure 18. Based on the ratio of maximum deflection to span, Yang et al. [50] classified the structural condition into four damage levels: slight, moderate, severe, and collapse. The ratios of critical maximum deflection to span for different damage levels were determined as follows:

where represents the maximum deflection, denotes the cross-sectional width. Thus, based on the method described above, the corresponding ranges of maximum vertical deflection are summarized in Table 2 and are used to distinguish different damage states in the subsequent analysis.

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram of pavement damage assessment.

Table 2.

Maximum deflection values corresponding to different damage levels of pavement structure.

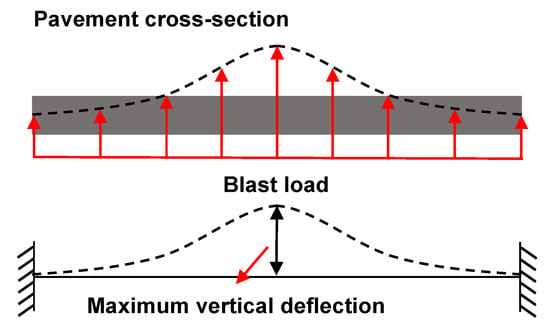

Figure 19 illustrates representative failure patterns corresponding to the four defined damage levels. At the slight damage level (Figure 19a), only small-scale cracking develops on the top surface, accompanied by localized tensile damage near the longitudinal ends of the side faces. The bottom surface remains essentially intact, and the overall stiffness and load-carrying capacity of the slab are largely preserved. At the moderate damage level (Figure 19b), the damaged area on the top surface expands, forming a distinct longitudinal band above the detonation region. Damage at mid-span along the side faces becomes more pronounced, and initial cracking appears on the bottom surface, with the longitudinal band remaining the dominant damage feature. At the severe damage level (Figure 19c), the affected zones on both the top and bottom surfaces enlarge significantly, and damage at mid-span intensifies substantially. The longitudinal damage bands on the upper and lower surfaces connect through the thickness, indicating a marked reduction in flexural stiffness. Concurrently, the damaged region at mid-span along the side faces broadens, whereas damage near the longitudinal ends diminishes. At the collapse level (Figure 19d), the top surface exhibits extensive cracking and spalling. The longitudinal bands on the top and bottom surfaces become fully connected over a large portion of the span. Severe damage concentrates at mid-span on the top surface and along the longitudinal band on the bottom surface. Adjacent areas show intensified cracking, and localized through-thickness failure zones develop near the side faces.

Figure 19.

Typical damage patterns for different damage levels: (a) slight damage ( = 9 kg, PBD = 1.15 m); (b) moderate damage ( = 21 kg, PBD = 1.45 m); (c) severe damage ( = 30 kg, PBD = 1.35 m); (d) collapse ( = 36 kg, PBD = 1.05 m).

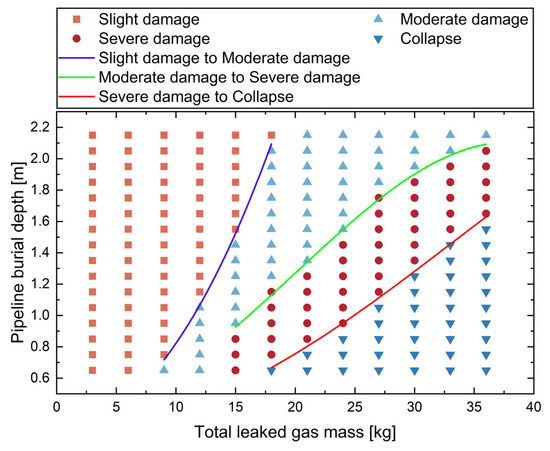

To establish quantitative boundaries between the four damage levels, a comprehensive series of numerical simulations was carried out for total leaked gas masses ranging from 6 to 36 kg and pipeline burial depths (PBD) between 0.65 and 2.15 m. For each case, the maximum pavement deflection was extracted and classified according to Table 2. Figure 20 summarizes the statistical distribution of maximum deflection over the full parameter space, together with fitted critical curves separating adjacent damage levels. The results show that damage severity increases systematically with increasing total leaked gas mass and decreasing burial depth, reflecting the combined effect of higher explosion energy and reduced soil confinement. The critical curves, expressed by the empirical relation in Equation (13), provide clear quantitative demarcations between slight, moderate, severe and collapse states, and thus form a convenient basis for damage prediction and performance-based design of pavement structures above gas pipelines.

where and are the burial depth and leaked gas mass, respectively.

Figure 20.

Deflection-based classification of pavement structural damage levels and the calibrated critical curves for explosion scenarios in the gas–pipeline–soil–pavement system.

4.5. Effectiveness of CFRP Strengthening Schemes

The numerical results indicate that, within the range of natural gas pipeline explosion scenarios considered in this study, the pavement structure mainly fails in a global flexural mode, superimposed with localized cracking in the vicinity of the blast-influenced region. Accordingly, protective measures should be conceived with the primary objective of enhancing the flexural stiffness and tensile resistance of the slab rather than relying solely on local thickening or strengthening.

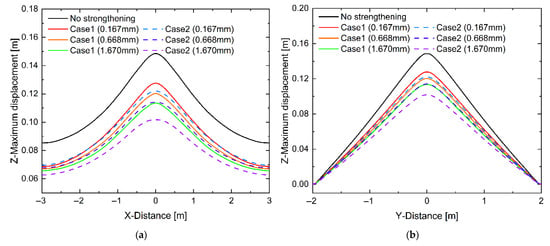

To assess the influence of CFRP thickness on the structural response for each scheme, computations are carried out for total CFRP thicknesses of 0.167 mm, 0.668 mm and 1.67 mm. Figure 21 shows the corresponding distributions of Z-maximum displacement along the X and Y directions. For both reinforcement schemes, the introduction of CFRP leads to a pronounced reduction in maximum vertical displacement compared with the unreinforced slab, confirming the beneficial effect of CFRP on blast resistance. As the CFRP thickness increases, the Z-maximum displacement decreases monotonically, reflecting the enhanced flexural stiffness and tensile capacity provided by the composite layers. For all thicknesses considered, Case 2 (top-and-bottom reinforcement) yields smaller displacements than Case 1, and the performance gap between the two schemes widens as the CFRP thickness increases. This trend indicates that simultaneous restraint of tensile strains on both faces of the slab is more effective than strengthening the tension face alone, particularly at higher reinforcement levels.

Figure 21.

Z-maximum displacement of pavement structure under different reinforcement schemes (a) variations along X direction, (b) variations along Y direction.

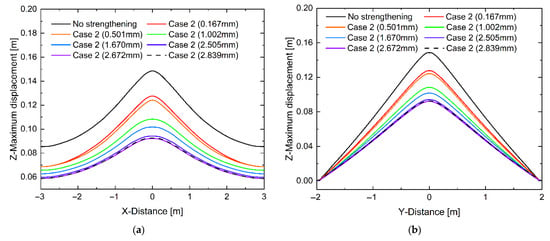

Building on these observations, Figure 22 focuses on Case 2 and compares the Z-maximum displacement of the pavement structure for a wider range of CFRP thicknesses, with the objective of determining an optimal thickness. The results show a clear diminishing-return tendency. For relatively small thicknesses, especially below about 1.002 mm, the Z-maximum displacement decreases rapidly with increasing CFRP thickness, indicating a high marginal benefit of additional layers. Beyond this range, the rate of reduction becomes more gradual, and further increases in thickness produce only limited additional stiffness. At a total CFRP thickness of 2.672 mm, the peak Z-maximum displacement is 92.15 mm, corresponding to a 37.93% reduction relative to the unreinforced case and demonstrating a substantial improvement in blast resistance. When the thickness is increased slightly to 2.839 mm, the peak displacement rises to 92.64 mm, exceeding the value at 2.672 mm and suggesting that numerical and modeling uncertainties may outweigh any marginal gain in stiffness. Within the present parameter range, a total CFRP thickness of 2.672 mm therefore emerges as an efficient reinforcement level for Case 2.

Figure 22.

Z-maximum displacement under different CFRP reinforcement thicknesses: (a) variations along X direction, (b) variations along Y direction.

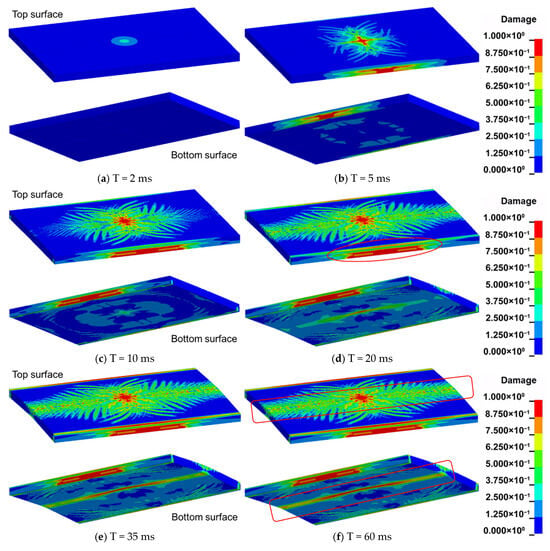

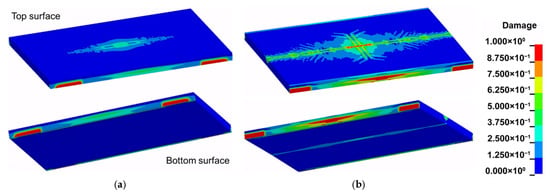

Figure 23 compares the damage patterns of the pavement structure before and after the application of the optimal CFRP reinforcement. The reinforced slab exhibits significantly increased overall stiffness, reduced crack widths, and a more favorable distribution of flexural deformation. In particular, the extent and severity of damage within the longitudinal damage zone at the bottom surface are markedly reduced, as shown in Figure 23b, indicating an effective suppression of tensile cracking on the tension side. At the same time, the reinforcement leads to a redistribution of internal forces and may promote slightly more pronounced cracking on the top surface, where compressive stresses and reflected tensile waves interact. Overall, the CFRP reinforcement scheme considered in this study effectively mitigates the blast-induced deformation and damage of the pavement structure and provides a rational basis for the design of practical strengthening measures for pavements above buried gas pipelines.

Figure 23.

Damage comparison of pavement structure before and after reinforcement: (a) unreinforced; (b) reinforced. (Red boxed region indicates mitigated blast-induced damage.)

Based on the analysis of the dynamic response and damage mechanisms of the pavement presented in this Section, it is further demonstrated that the explicit modeling of air combined with the CLE algorithm can accurately simulate the effects of blast loading. While investigating the propagation of explosion-induced stress waves along the pipeline is of inherent interest, the response of the pipeline in such a near-field scenario is dominated by intense local loading rather than by the long-distance transmission of stress waves along its axis. Consequently, the potential influence of blast wave propagation on far-field pipeline behavior falls outside the scope of this study and is not discussed. The present work therefore focuses primarily on examining the damage development in the overlying concrete pavement induced by buried gas pipeline explosions, with particular emphasis on the near-field soil–structure interaction and pavement response.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a coupled gas–pipeline–soil–pavement numerical framework based on an ALE–Lagrangian formulation to investigate the dynamic response and damage evolution of concrete pavement structures subjected to natural gas pipeline explosions. The proposed framework was validated against benchmark underground explosion tests and concrete slab blast experiments, confirming its capability to capture key features of blast-induced soil–structure interaction and pavement damage. On this basis, a series of parametric analyses incorporating different leakage masses and pipeline burial depths were performed, revealing the fundamental response characteristics of pavements, including cases with CFRP strengthening. From these analyses, a deflection-based damage classification and prediction approach was established, together with empirical damage evaluation curves. Furthermore, the effectiveness of CFRP reinforcement schemes for enhancing blast resistance was quantitatively assessed. The study thus provides a validated numerical tool, fundamental insight into pavement behavior under internal blast loading, and practical damage assessment criteria for engineering applications. Several main conclusions are presented as follows.

(1) The pavement response under natural gas pipeline explosions is dominated by a global flexural mode, with the maximum vertical deflection occurring at mid-span above the equivalent detonation center. For leakage masses of 9 kg, 21 kg, 30 kg, and 36 kg, the corresponding maximum deflections are 11.88 mm, 48.63 mm, 94.67 mm, and 148.46 mm, respectively. The deflection attenuates along the longitudinal direction and varies almost linearly in the transverse direction, and a pronounced longitudinal damage zone forms and penetrates both the top and bottom surfaces once the blast load exceeds a critical level.

(2) Taking the maximum deflection as a global response index, the pavement damage is classified into four levels, namely slight (<20 mm), moderate (20–40 mm), severe (40–80 mm), and collapse (>80 mm). Parametric simulations over a range of leaked gas masses and pipeline burial depths, combined with curve fitting, yield empirical critical curves that separate adjacent damage levels and allow rapid prediction of pavement damage state from the leakage mass and burial depth.

(3) CFRP sheet reinforcement effectively reduces blast induced deflection and damage in the pavement structure. Among the reinforcement layouts examined, the scheme with CFRP applied on both the top and bottom surfaces provides the best blast resistance, and within the parameter range considered, a total CFRP thickness of about 2.67 mm in this configuration could reduce a maximum vertical displacement by 37.93% compared to the unreinforced case.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and Z.L.; methodology, L.L. and Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, L.L., J.C. and J.L.; formal analysis, L.L. and J.C.; investigation, L.L., J.C. and J.L.; resources, L.L. and J.L.; data curation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, L.L., Z.L., J.C. and J.L.; visualization, L.L. and J.C.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China Railway 18th Bureau Group Municipal Engineering Co., Ltd. under the Technical Development Contract (SYSU-76140-20240124-0002) and partially funded by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Project for Sustainable Development (KCXFZ202002011008532); and, the APC was funded by China Railway 18th Bureau Group Municipal Engineering Co., Ltd. under the same contract.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lijun Li was employed by the company Guangzhou Metro Co., Ltd. and author Jiguan Liang was employed by the company Guangzhou Municipal Engineering Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Saneian, M.; Han, P.H.; Jin, S.; Bai, Y. Fracture response of steel pipelines under combined tension and bending. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 154, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirimello, P.G.; Otegui, J.L.; Buisel, L.M. Explosion in gas pipeline: Witnesses’ perceptions and expert analyses’ results. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 106, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.B.; Wehrstedt, K.D.; Krebs, H. Lessons learned from recent fuel storage fires. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 107, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, L.; Kaewunruen, S. Blast Effects on Buried Infrastructures. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]