Prediction of Concrete Arch Dam Response Using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A detailed strategy is proposed for the thermo-mechanical calibration of numerical models for high concrete arch dams.

- Instead of using parametric regression models—which apply a single regression function across the entire dataset—this study employs a nonparametric regression approach that dynamically defines the regression function for each individual input. This adaptability enables the capture of highly nonlinear dam behavior without relying on excessively complex machine learning models.

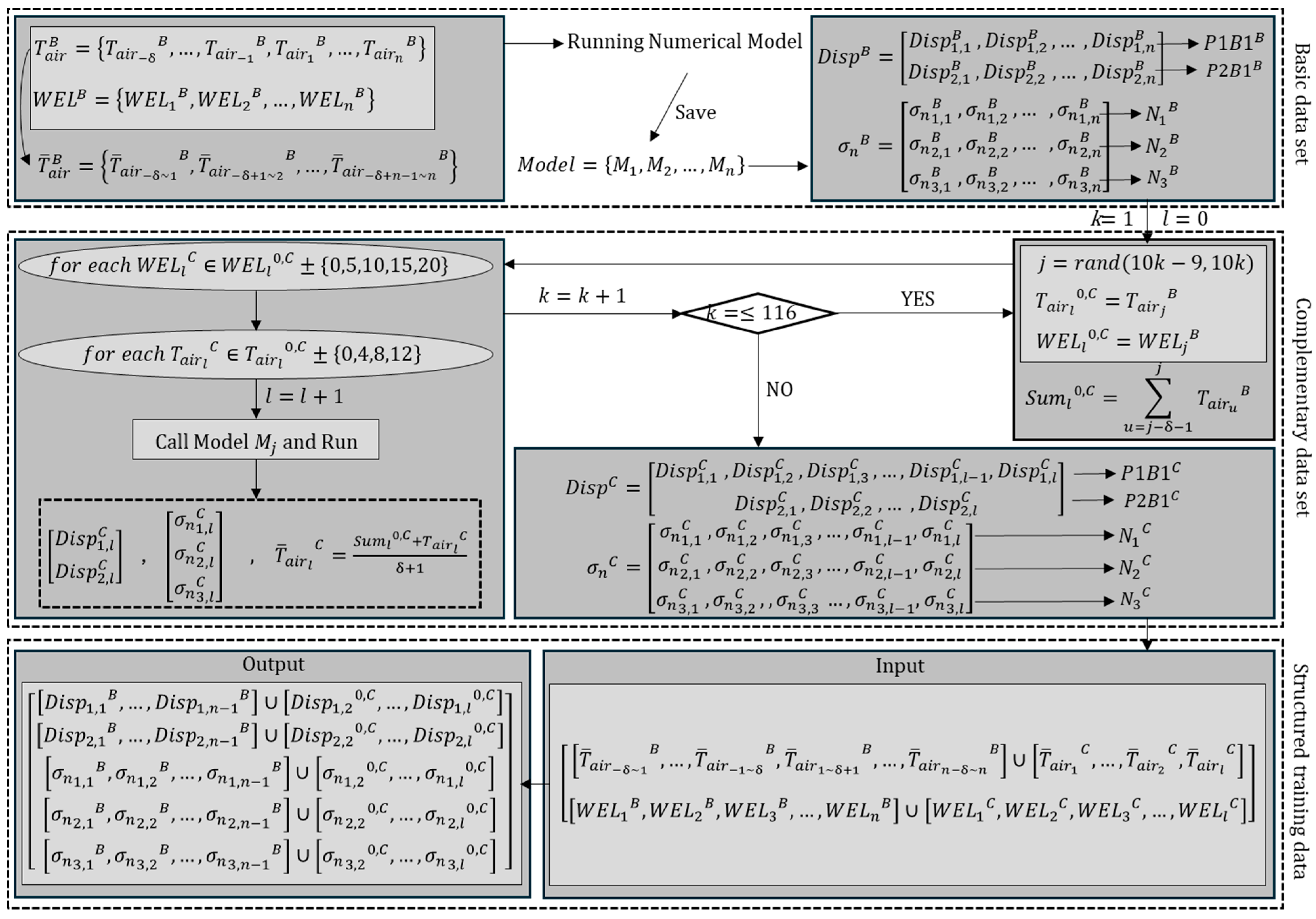

- The training dataset is generated entirely from a well-calibrated numerical model, eliminating the influence of noisy or invalid measurements often present in field observations. This ensures more reliable and robust predictions. However, an optional mechanism can be included to integrate new instrumentation data when needed, allowing for model correction over time.

- Since training data is derived from the numerical model, the methodology can predict multiple response types, including deformation, stress, and joint opening. In this study, stress and deformation are selected to demonstrate the applicability of the methodology.

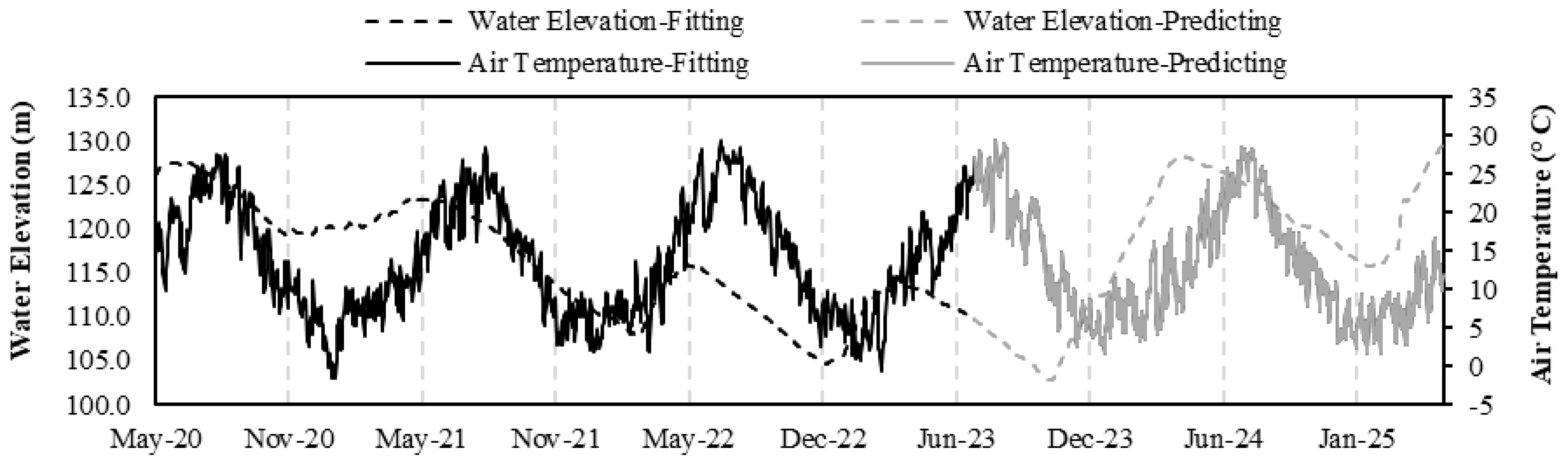

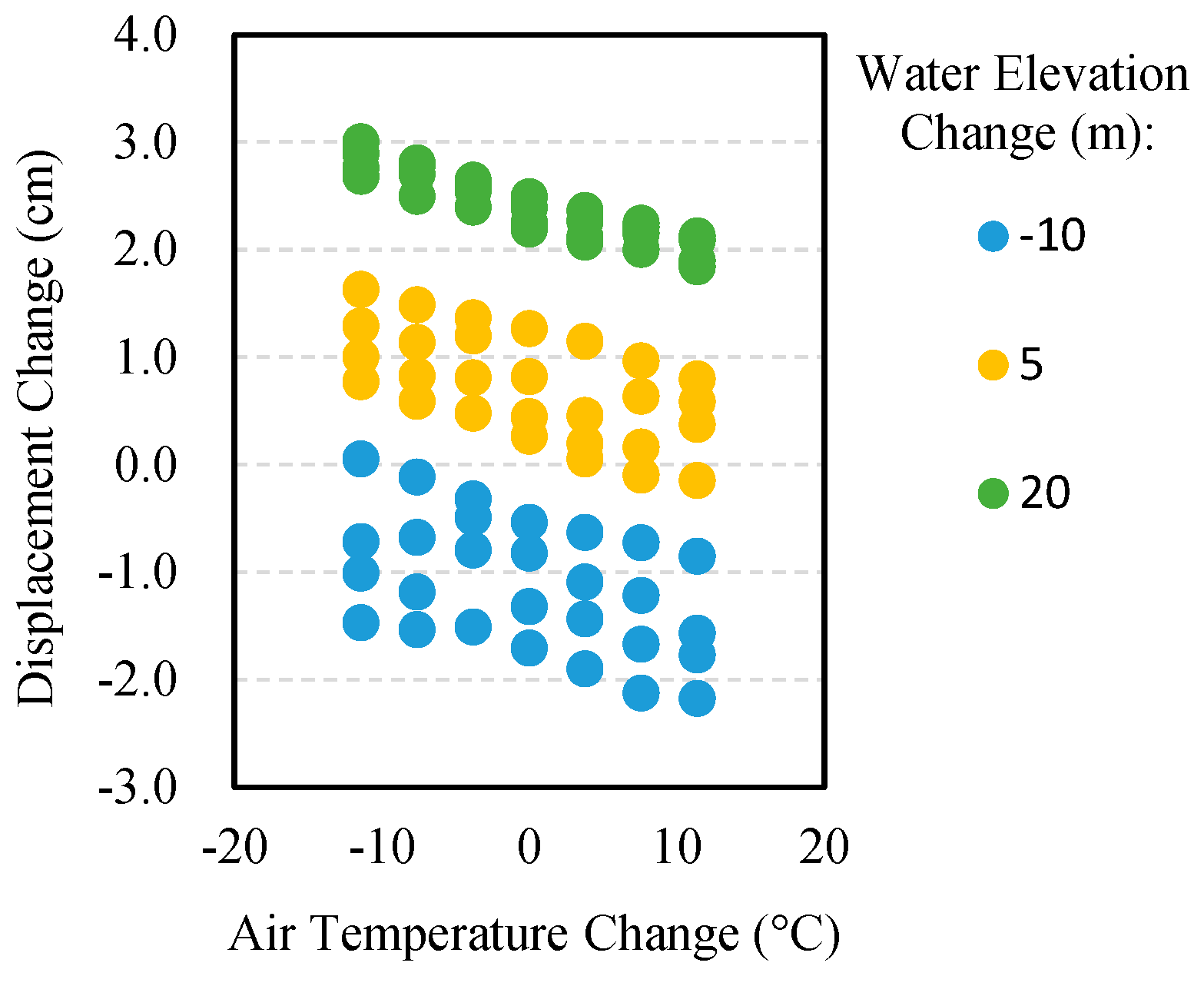

- The input variables include reservoir water elevation and air temperature. However, instead of using the current air temperature, a study is conducted to identify a more effective temperature-based variable for improved prediction accuracy.

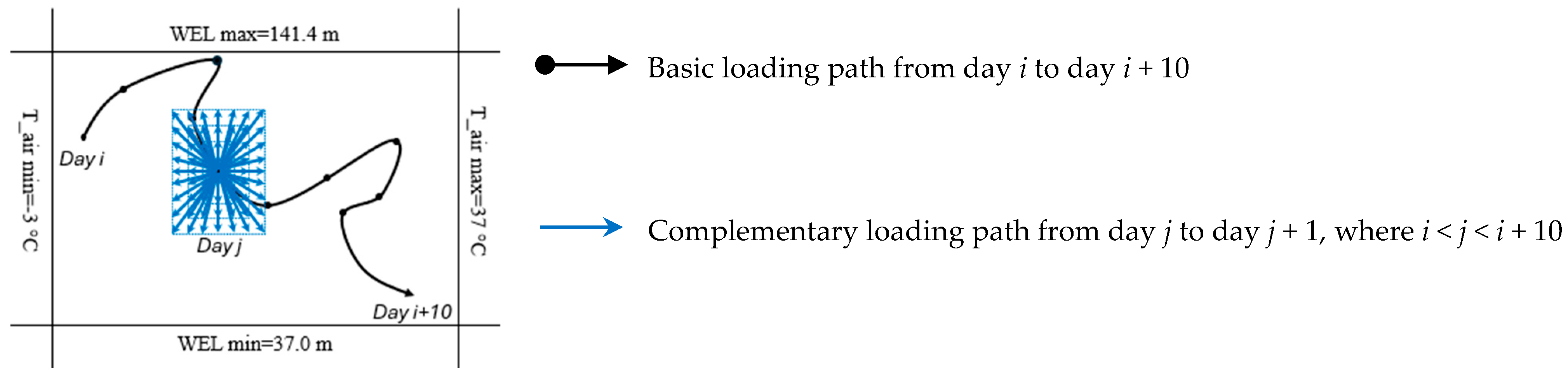

- Initial analyses reveal that nonlinear concrete arch dam responses depend on the loading path, i.e., two models with similar final water elevation and air temperature but different historical loading conditions show different responses. To account for this, the numerical model is evaluated under various possible loading paths, ensuring that the training dataset includes not only the actual loading history experienced by the dam but also a broader range of potential scenarios.

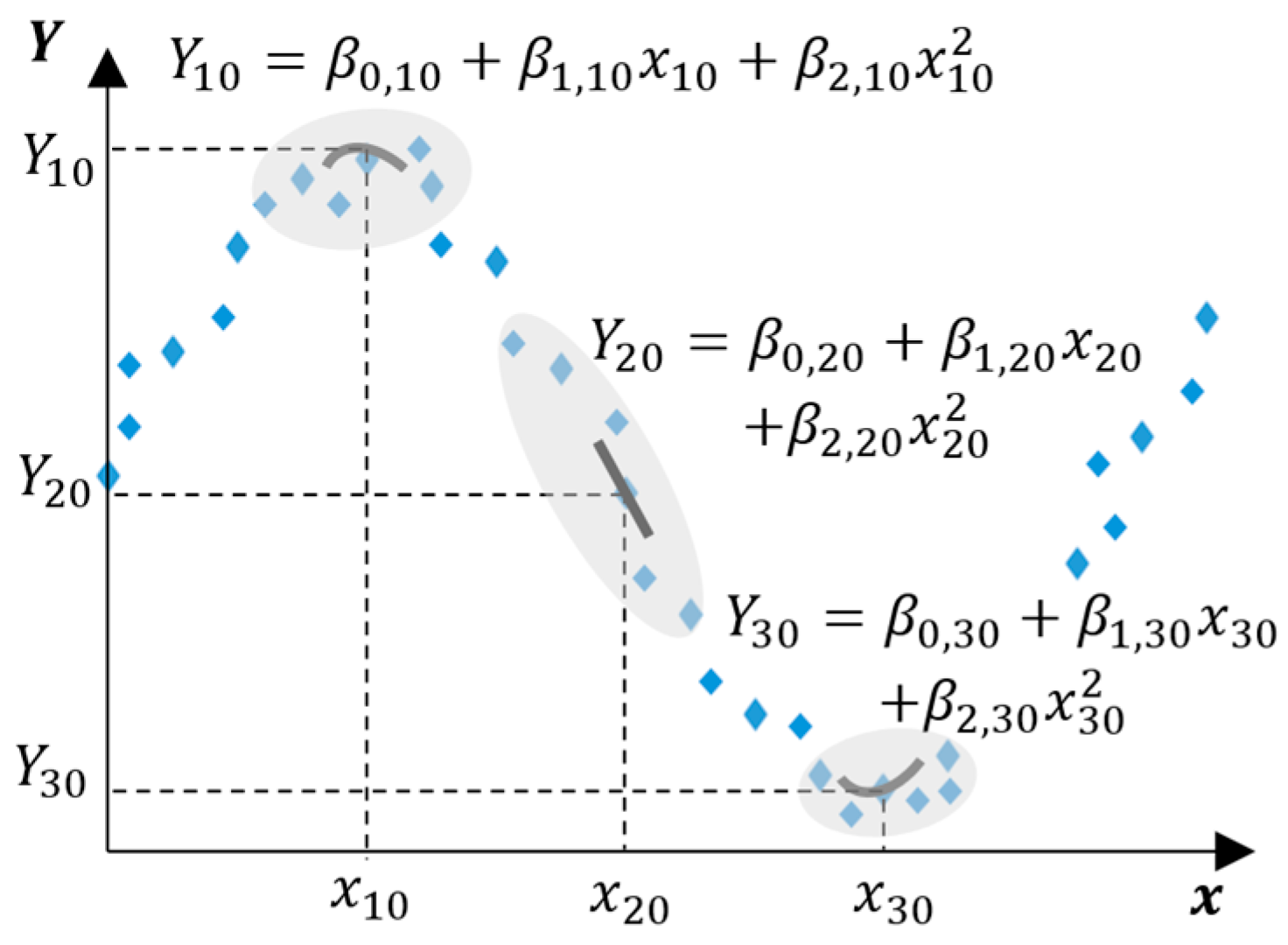

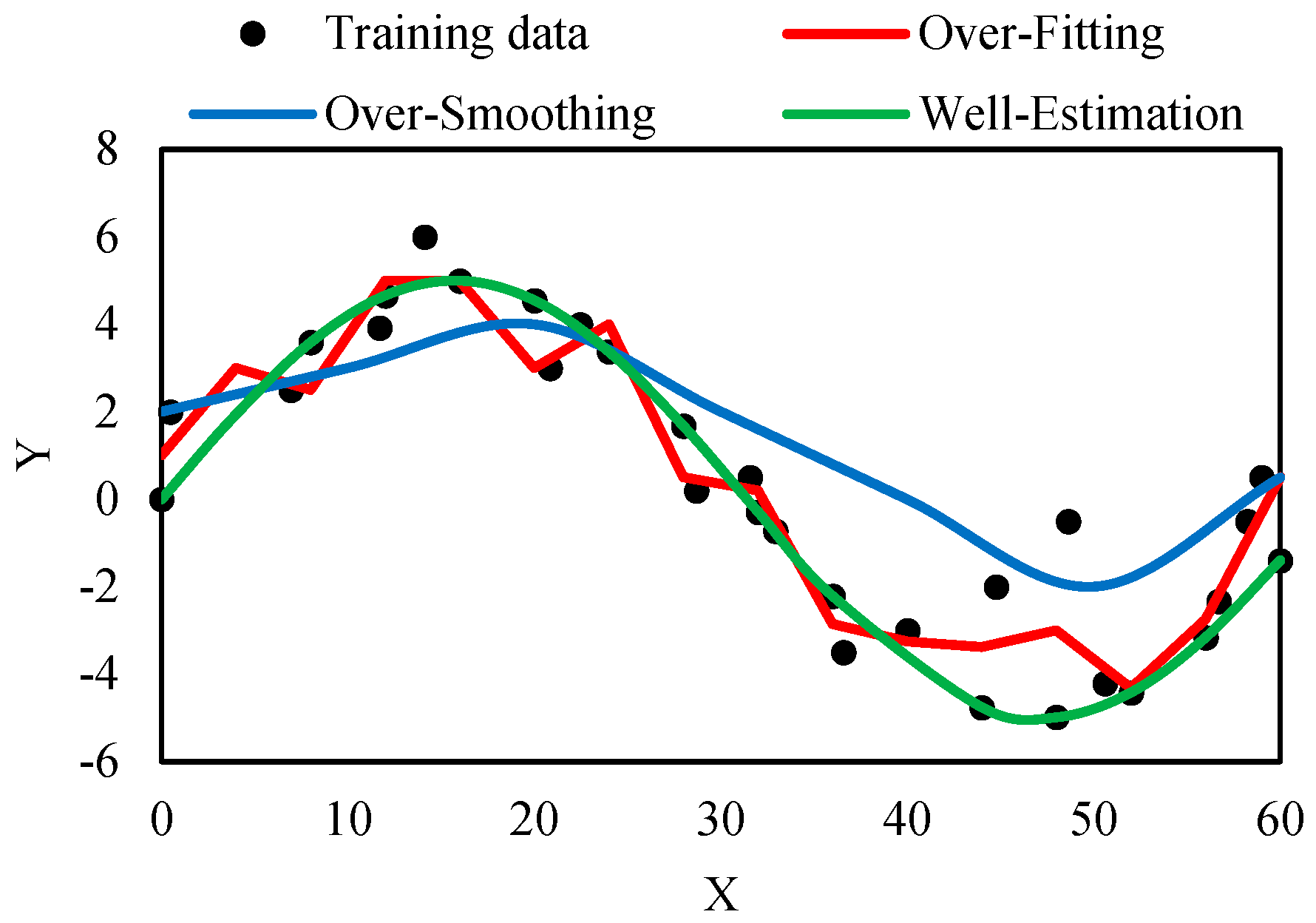

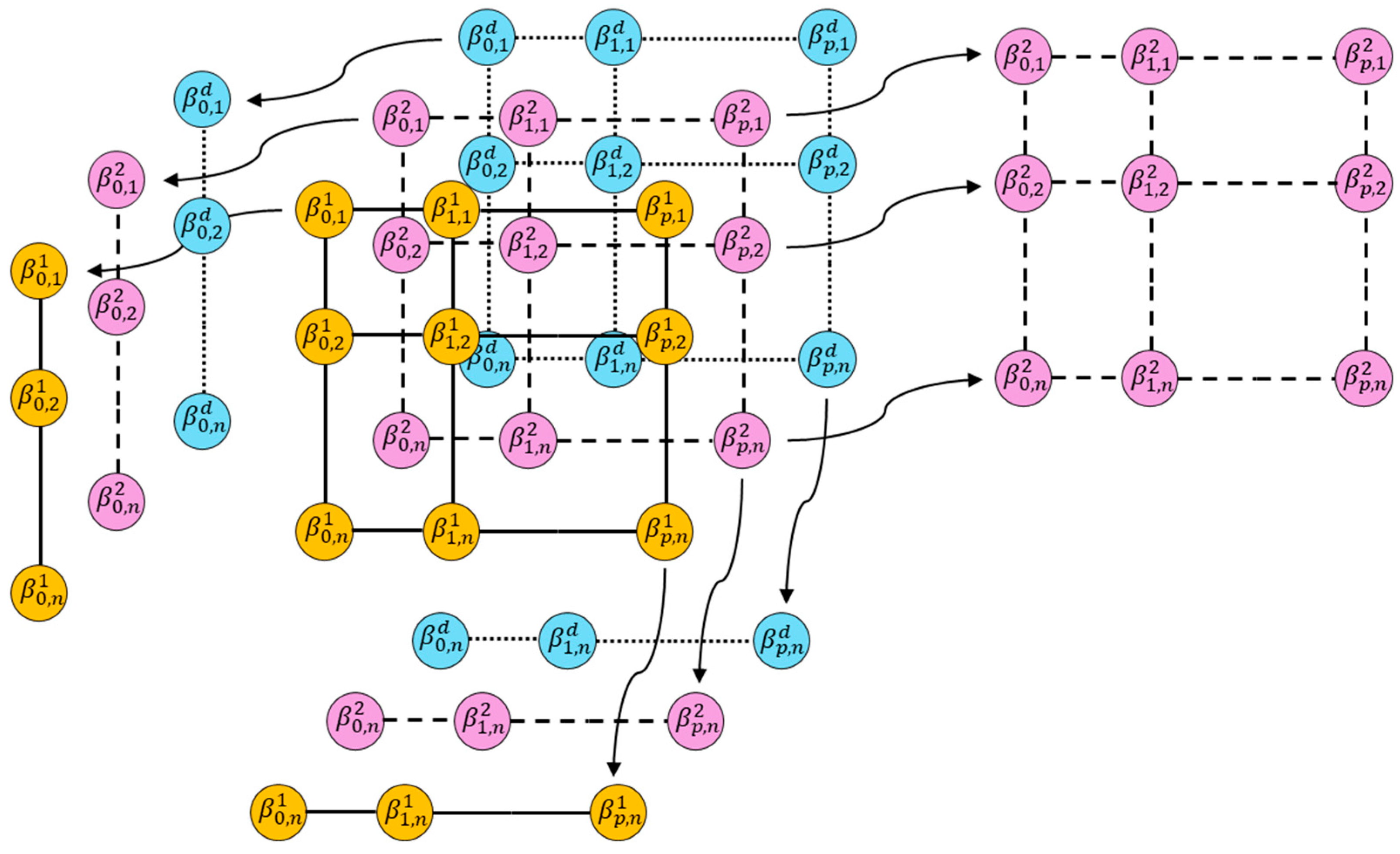

2. Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing

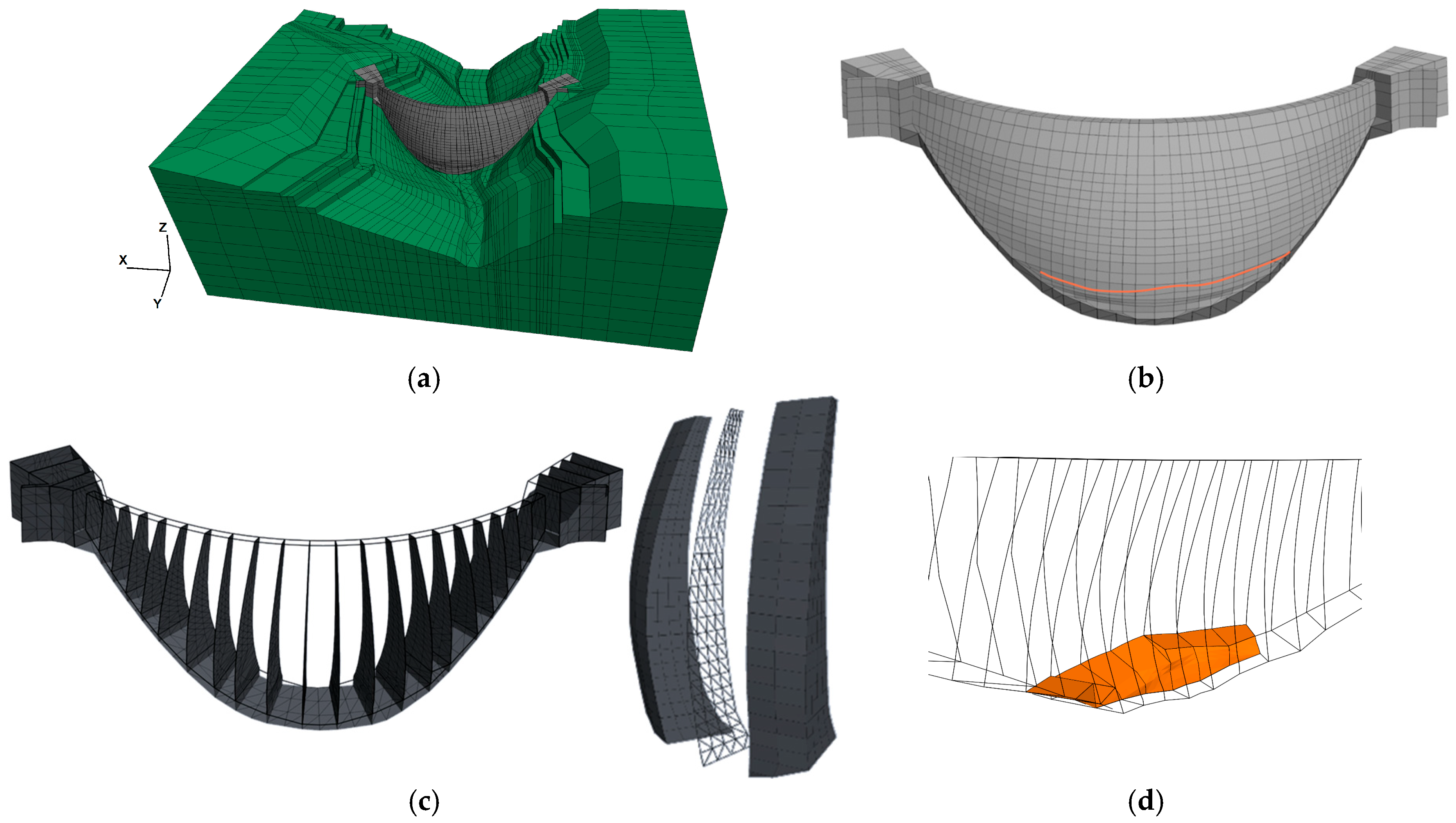

3. The Numerical Model

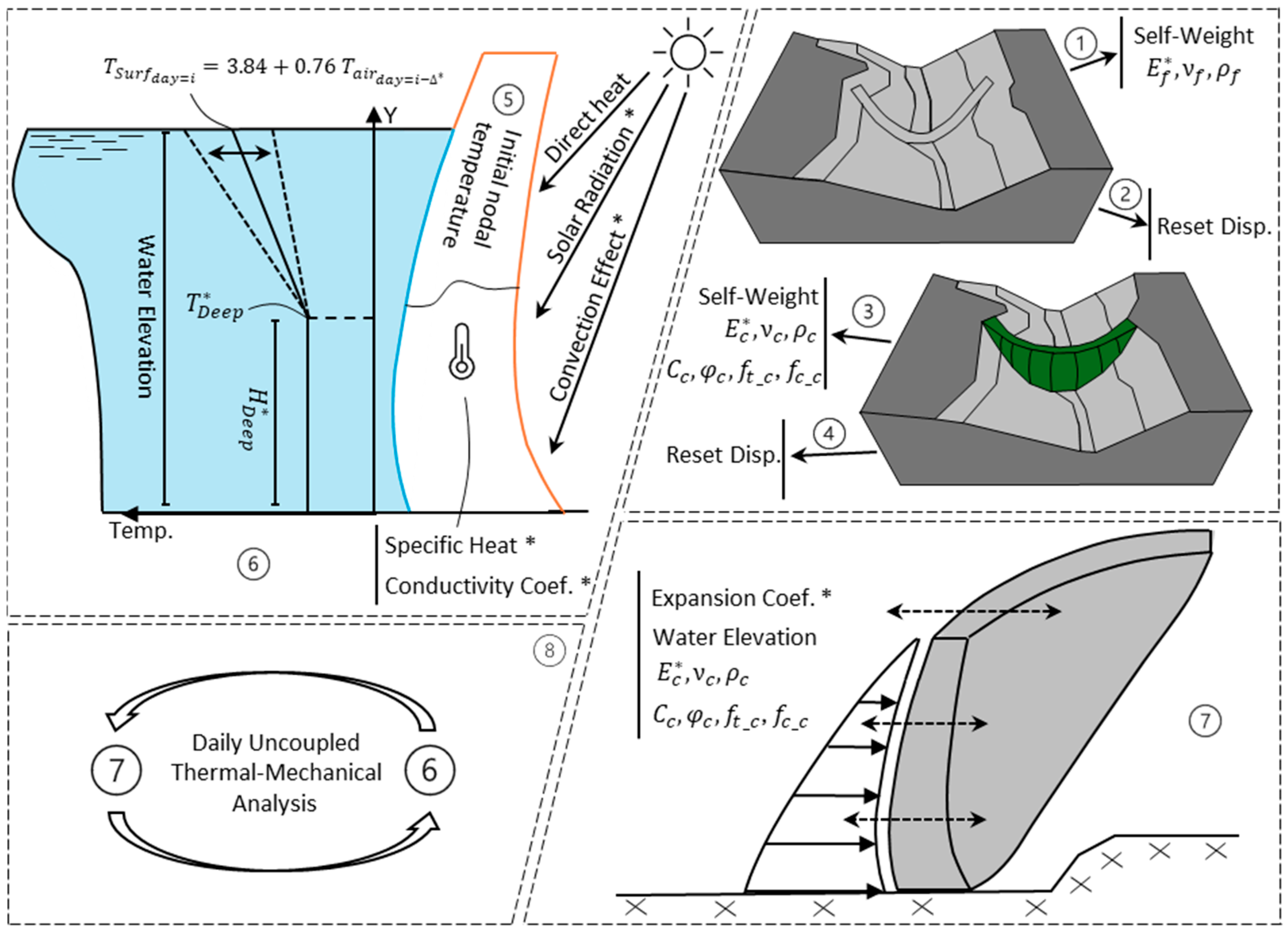

- Foundation Self-Weight: The foundation elements (without the dam body) are called and analyzed under their self-weight.

- Stress Initialization: Displacements are reset to zero while retaining stresses for the next step. This allows the estimation of in situ foundation stresses.

- Dam Self-Weight: The dam body elements are introduced, and the model is solved under the dam’s self-weight. It is worth mentioning that, in this study, the dam body stage construction is not simulated, as the primary analysis has indicated that it has a negligible impact on the stress-deformation field.

- Displacement Reset: Similarly to Step 2, displacements are set to zero while retaining stresses. This step is essential for model calibration, as it enables comparisons between the model displacement and observed displacements from pendulum readings.

- Initial Thermal Field Definition: The initial temperature field of the dam body is defined for each model node based on thermometer readings for day i.

- Thermal Simulation: Thermal boundary conditions for day i + 1 are applied to the upstream and downstream faces of the dam body. These conditions are categorized as dry or wet based on whether the surface is in contact with the reservoir. The dry boundaries are influenced by the air temperature, solar radiation, and convection effects. The wet boundaries are defined by the water temperature, which varies in response to air temperature fluctuations and reservoir elevation. Further details on these boundary conditions are provided in Section 4. After applying the thermal boundary conditions, a transient uncoupled thermal analysis is performed over one day (86,400 s). In this step, the temperature variations do not induce deformations.

- Hydrostatic Loading: The hydrostatic pressure for day i + 1 is applied to the upstream face of the dam body, and a mechanical analysis is performed to update displacements and stresses according to the new thermal and hydrostatic conditions.

- Time Stepping: Steps 6 and 7 are iteratively repeated for the subsequent days.

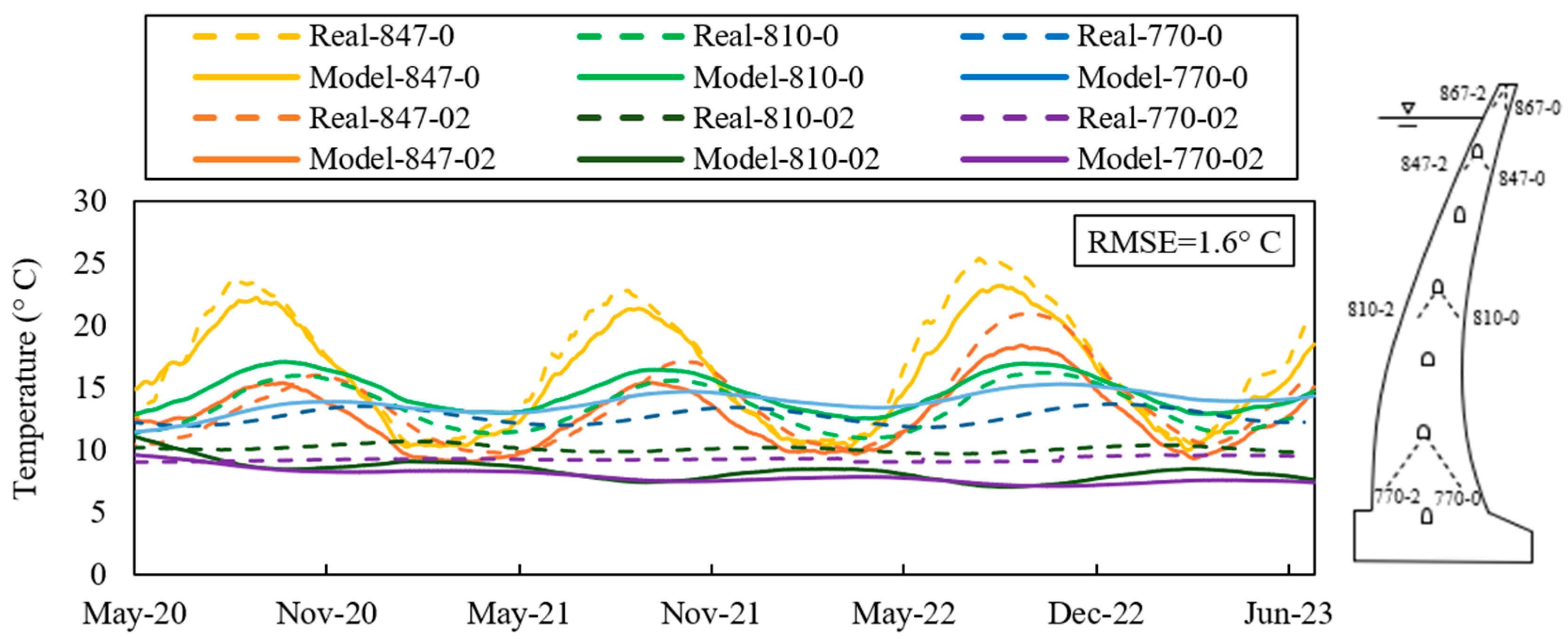

4. The Numerical Model Calibration

- (I)

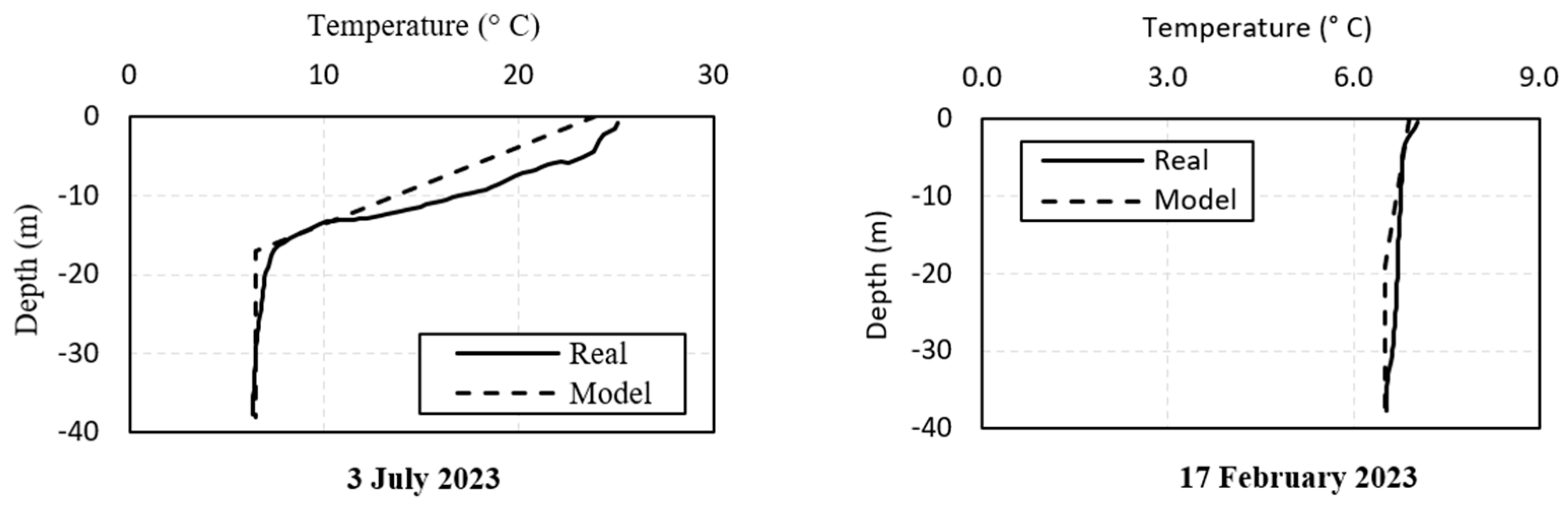

- Wet Surface Temperature Calibration: This step involves calibrating the reservoir water temperature. On any given day, the water temperature typically varies linearly from the surface water temperature to the deep-water temperature, after which it remains constant down to the dam’s base. The surface water temperature is influenced by air temperature with a certain time delay. A commonly used approach to relating surface water temperature to air temperature is Bofang’s formula [68]:

- (II)

- Dry Surface Temperature Calibration: The temperature of dry surfaces is influenced by the mean daily air temperature, solar radiation, and convection effects. Solar radiation is estimated by increasing the air temperature by a specific amount. Léger et al. [69] suggested increasing the air temperature by 2 °C in summer and 5 °C in winter to approximate the solar radiation effect on the concrete dam’s surface. However, these values require calibration, as they may vary depending on geographic location, climate conditions, and surface orientation. The convection effect is incorporated into the model by a predefined convection coefficient, which also requires calibration to accurately reflect heat exchange between the dam surface and the surrounding air. Thus, the calibration parameters for dry surfaces include solar radiation temperature and convection coefficient.

- (III)

- Inner Nodes Temperature Calibration: The temperature of inner nodes is influenced by the upstream and downstream thermal boundary conditions, as well as the thermal properties of the dam material, specifically its specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity. These two parameters should be carefully calibrated to ensure consistency with observed temperature distributions.

5. Response Prediction Using a Hybrid Methodology

5.1. Training Data Preparation

5.2. The LOESS Model Setup

5.3. The Prediction Error Quantification

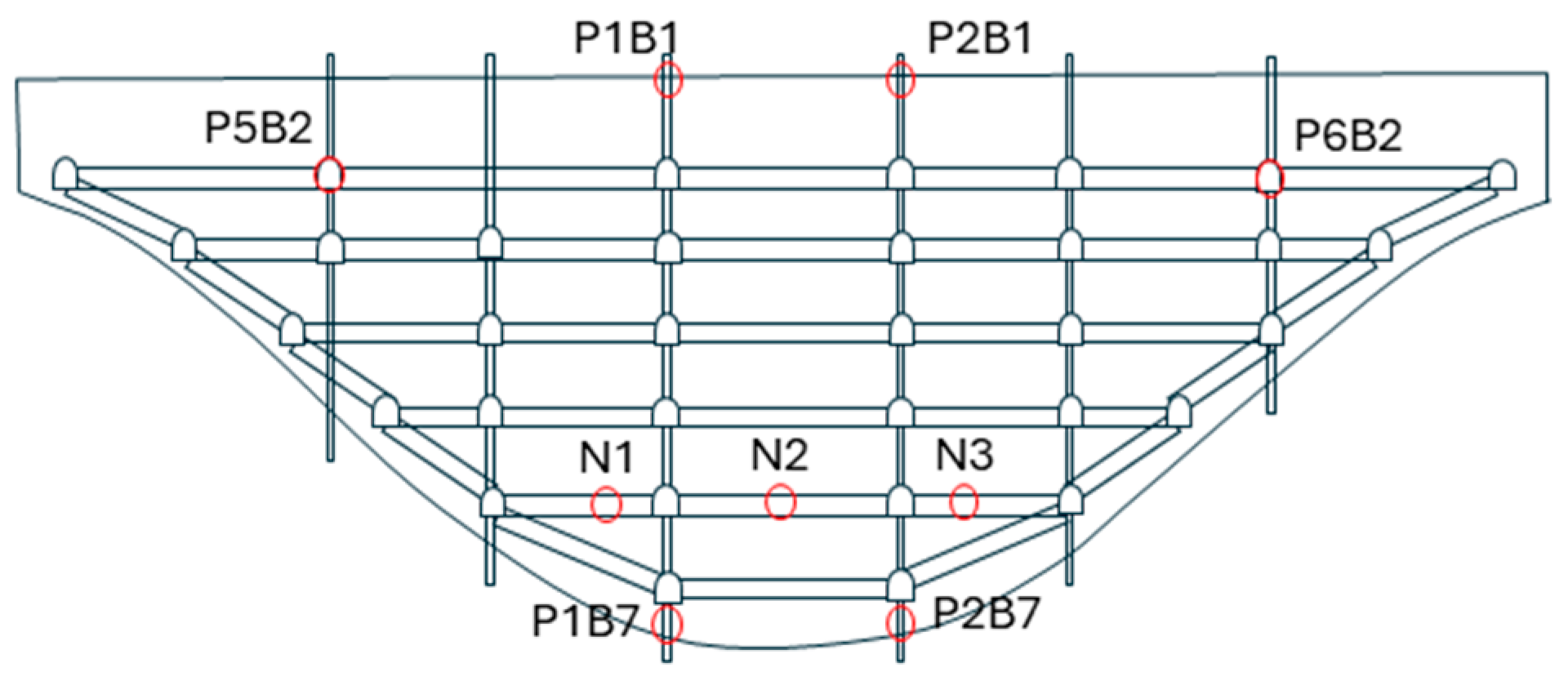

6. Results and Discussion

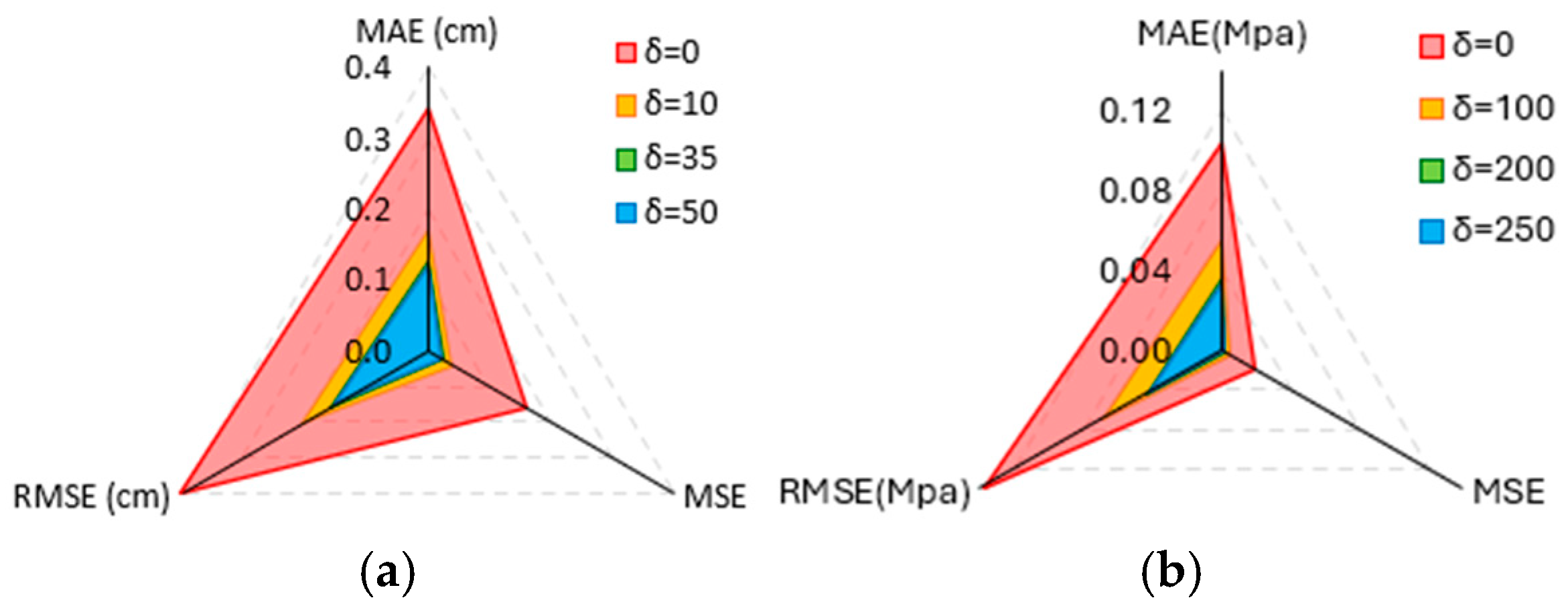

6.1. Selection of δ

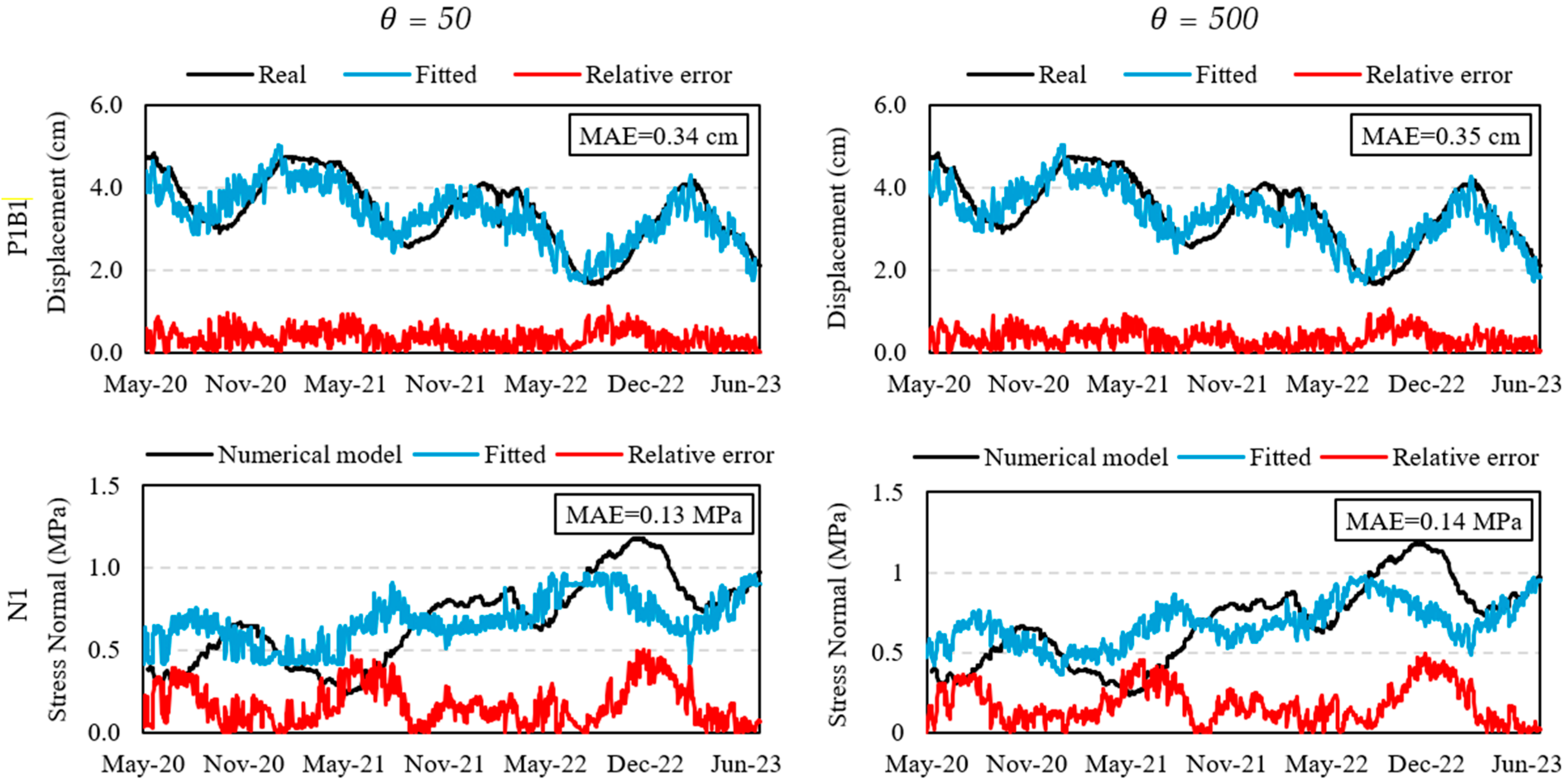

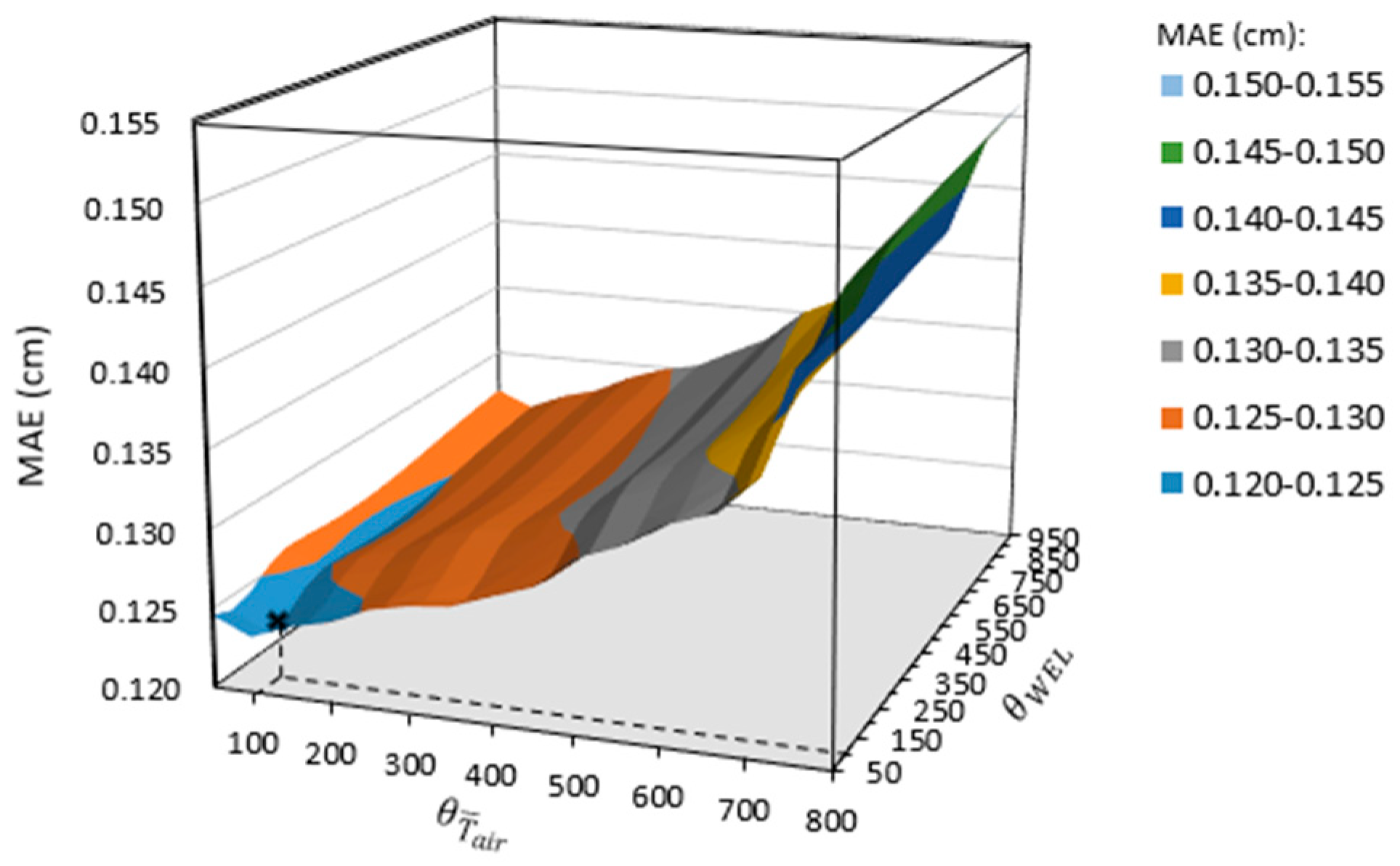

6.2. Selection of θ

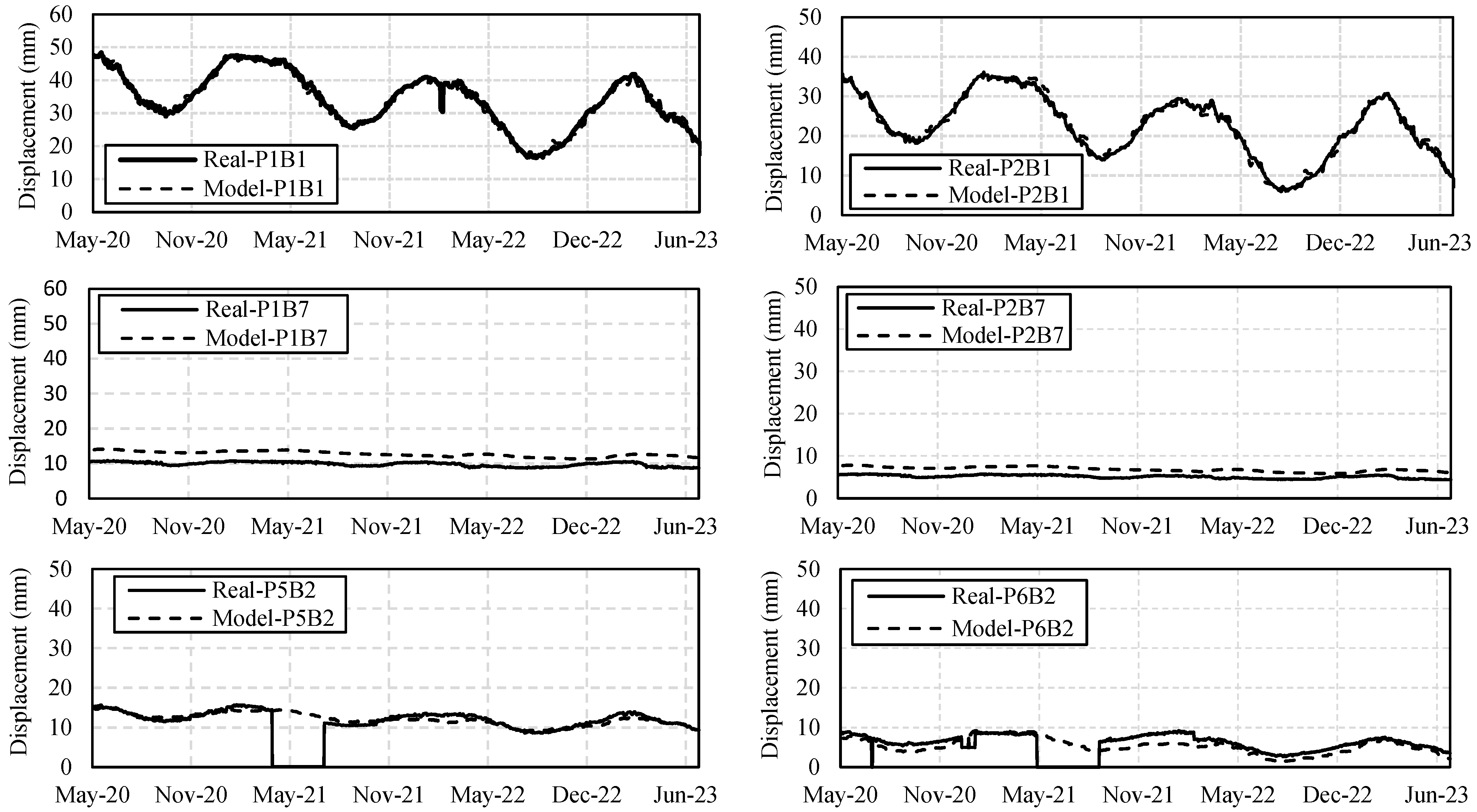

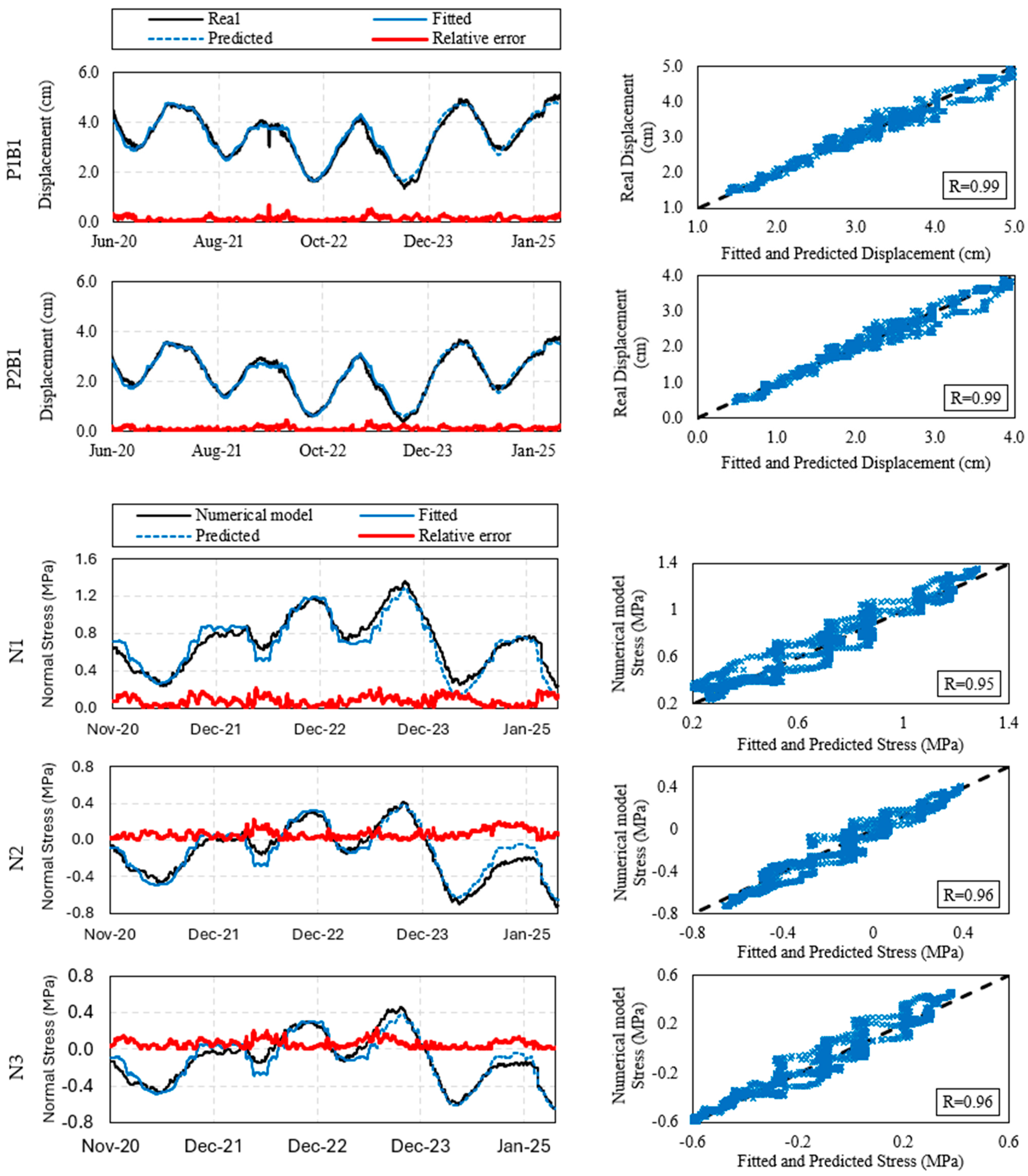

6.3. Final Fitting and Prediction Attempt

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chelidze, T.; Matcharashvili, T.; Abashidze, V.; Kalabegishvili, M.; Zhukova, N. Real time monitoring for analysis of dam stability: Potential of nonlinear elasticity and nonlinear dynamics approaches. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2013, 7, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, L.; Williams, D.; Seppälä, J. Real-time monitoring of tailings dams. Georisk Assess. Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards 2021, 15, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Li, M.; Kong, T.; Ma, J. Multi-sensor real-time monitoring of dam behavior using self-adaptive online sequential learning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 140, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Ying, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Li, M.; An, W. Motion and Appearance Decoupling Representation for Event Cameras. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 5964–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, N.; Al-Ansari, N.; Ali, S.H.; Laue, J.; Knutsson, S. Dams safety: Review of satellite remote sensing applications to dams and reservoirs. J. Earth Sci. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 11, 347–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Chang, L.; Chang, F. Intelligent control for modeling of real-time reservoir operation, part II: Artificial neural network with operating rule curves. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 2005, 19, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.G.; da Silva, V.H.C.; Pinto, L.F.R.; Centoamore, P.; Digiesi, S.; Facchini, F.; Neto, G.C.d.O. Economic, environmental and social gains of the implementation of artificial intelligence at dam operations toward Industry 4.0 principles. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, L.; Kim, T.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Peng, Q. A large-scale comparison of Artificial Intelligence and Data Mining (AI&DM) techniques in simulating reservoir releases over the Upper Colorado Region. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126723. [Google Scholar]

- Serradilla, O.; Zugasti, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Zurutuza, U. Deep learning models for predictive maintenance: A survey, comparison, challenges and prospects. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 10934–10964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Saini, R.P. A review on operation and maintenance of hydropower plants. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 49, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Kaplan, A. A brief history of artificial intelligence: On the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopgood, A.A. Intelligent Systems for Engineers and Scientists: A Practical Guide to Artificial Intelligence; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi, A.; Amini, A.; Hariri-Ardebili, M.A. An uncertainty-aware dynamic shape optimization framework: Gravity dam design. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 222, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASE Arch Dam Task Group. User’s Guide: Arch Dam Stress Analysis System (ADSAS); US Army: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flah, M.; Nunez, I.; Ben Chaabene, W.; Nehdi, M.L. Machine learning algorithms in civil structural health monitoring: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2621–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri-Ardebili, M.A.; Pourkamali-Anaraki, F. An automated machine learning engine with inverse analysis for seismic design of dams. Water 2022, 14, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, D.; Seyedpoor, S.M. Shape optimal design of arch dams using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and improved particle swarm optimization. Appl. Math. Model. 2010, 34, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanzaib, M.; Shah, S.A.; Son, H.J.; Jang, S.-H.; Kim, T.-W. Predicting hydrological drought alert levels using supervised machine-learning classifiers. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 3019–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Cao, M.-T.; Huang, I.-F. Hybrid artificial intelligence-based inference models for accurately predicting dam body displacements: A case study of the Fei Tsui dam. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 21, 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Gao, X. Monitoring and early warning of a metal mine tailings pond based on a deep learning bidirectional recurrent long and short memory network. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Ghanem, K.; Alsalemi, A.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A. Artificial intelligence based anomaly detection of energy consumption in buildings: A review, current trends and new perspectives. Appl. Energy 2021, 287, 116601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wen, Z.; Wu, Z. Study on an intelligent inference engine in early-warning system of dam health. Water Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 1545–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri-Ardebili, M.A.; Sudret, B. Polynomial chaos expansion for uncertainty quantification of dam engineering problems. Eng. Struct. 2020, 203, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, A.; Spada, M.; Vetsch, D.F.; Marelli, S.; Whealton, C.; Burgherr, P.; Sudret, B. Metamodeling for uncertainty quantification of a flood wave model for concrete dam breaks. Energies 2020, 13, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Yuan, L.; van Gelder, P.; Yorke-Smith, N. Long-term viscoelastic deformation monitoring of a concrete dam: A multi-output surrogate model approach for parameter identification. Eng. Struct. 2022, 266, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Yang, J.; Ma, C.; Cheng, L.; Li, G. The prediction of concrete dam displacement using Copula-PSO-ANFIS hybrid model. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 4335–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, F.; Hermosilla, G.; Piña, O.; Villavicencio, G.; Allende-Cid, H.; Palma, J.; Valenzuela, P.; García, J.; Carpanetti, A.; Minatogawa, V. Generation of synthetic data for the analysis of the physical stability of tailing dams through artificial intelligence. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Tang, X. Slope stability prediction using integrated metaheuristic and machine learning approaches: A comparative study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 118, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chen, S.; Hariri-Ardebili, M.A.; Li, T. An explainable probabilistic model for health monitoring of concrete dam via optimized sparse bayesian learning and sensitivity analysis. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2023, 2023, 2979822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shu, X. A mathematical-mechanical hybrid driven approach for determining the deformation monitoring indexes of concrete dam. Eng. Struct. 2023, 277, 115353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Luo, S.; Yuan, D. Optimized combined forecasting model for hybrid signals in the displacement monitoring data of concrete dams. In Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1989–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L.; Zheng, D.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, H. Stress estimation of concrete dams in service based on deformation data using SIE–APSO–CNN–LSTM. Water 2022, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.; Miranda, F.; Antunes, A.; Romão, X.; Pedro Santos, J. Characterization of relative movements between blocks observed in a concrete dam and definition of thresholds for novelty identification based on machine learning models. Water 2023, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, S. Estimation of unloading relaxation depth of Baihetan Arch Dam foundation using long-short term memory network. Water Sci. Eng. 2021, 14, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sui, X.; Liu, Y.; Gu, H.; Xu, B.; Xia, Q. Prediction and interpretation of the deformation behaviour of high arch dams based on a measured temperature field. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 13, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariri-Ardebili, M.A.; Mahdavi, G.; Nuss, L.K.; Lall, U. The role of artificial intelligence and digital technologies in dam engineering: Narrative review and outlook. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Wen, L.; Sun, X. A multi-output prediction model for the high arch dam displacement utilizing the VMD-DTW partitioning technique and long-term temperature. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 267, 126135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Yang, M.; Li, S.; Liu, Z. A New Prediction Model of Dam Deformation and Successful Application. Buildings 2025, 15, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, Y.; Yang, S.; Su, H. Dam deformation prediction considering the seasonal fluctuations using ensemble learning algorithm. Buildings 2024, 14, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ren, Q.; Li, M.; Fang, X.; Xiao, L.; Li, H. A separate modeling approach to noisy displacement prediction of concrete dams via improved deep learning with frequency division. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 60, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zheng, S.; Qin, X. Ordinary Kriging interpolation method combined with FEM for arch dam deformation field estimation. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wei, B.; Li, H.; Mao, Y. Multipoint hybrid model for RCC arch dam displacement health monitoring considering construction interface and its seepage. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 110, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Wei, B.; Xu, F.; Zhou, L. Deterministic combination prediction model of concrete arch dam displacement based on residual correction. In Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1011–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Weng, K.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, T.; He, Q.; Su, Y. Time series prediction of dam deformation using a hybrid STL–CNN–GRU model based on sparrow search algorithm optimization. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Gu, C.; Valente, S.; Zhao, E.; Liu, X.; Yuan, D. Multi-arch dam safety evaluation based on statistical analysis and numerical simulation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Liu, B.; Yuan, D.; Mao, Y.; Yao, S. Spatiotemporal hybrid model for concrete arch dam deformation monitoring considering chaotic effect of residual series. Eng. Struct. 2021, 228, 111488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, C.; Gu, C.; Su, H.; Wu, B. Hydraulic-seasonal-time-based state space model for displacement monitoring of high concrete dams. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2021, 43, 3347–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, F.; Conde, A.; Vicente, D.J. Identification of dam behavior by means of machine learning classification models. In Numerical Analysis of Dams: Proceedings of the 15th ICOLD International Benchmark Workshop 15; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 851–862. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Gu, C.; Meng, Z.; Hu, Y. Integrating the finite element method with a data-driven approach for dam displacement prediction. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 4961963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, C.; Gu, C.; Su, H.; Hu, K.; Xia, Q. Displacement monitoring model of concrete dams using the shape feature clustering-based temperature principal component factor. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2020, 27, e2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Zhao, E.; Gu, C.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y. A nonlinear method for component separation of dam effect quantities using kernel partial least squares and pseudosamples. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1958173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Gu, C.; Bao, T.; Xia, Q.; Hu, K. Hysteretic effect considered monitoring model for interpreting abnormal deformation behavior of arch dams: A case study. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2019, 26, e2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gu, C.; Chen, B. Zoned elasticity modulus inversion analysis method of a high arch dam based on unconstrained Lagrange support vector regression (support vector regression arch dam). Eng. Comput. 2017, 33, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.H. Classical and Modern Regression with Applications; Duxbury Press: Belmont, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- John Lu, Z.Q. The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2010, 173, 693–694. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, N.S. An introduction to kernel and nearest-neighbor nonparametric regression. Am. Stat. 1992, 46, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storlie, C.B.; Helton, J.C. Multiple predictor smoothing methods for sensitivity analysis: Description of techniques. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2008, 93, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Veiga, S.; Wahl, F.; Gamboa, F. Local polynomial estimation for sensitivity analysis on models with correlated inputs. Technometrics 2009, 51, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Gijbels, I. Variable bandwidth and local linear regression smoothers. Ann. Stat. 1992, 20, 2008–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Gijbels, I. Adaptive order polynomial fitting: Bandwidth robustification and bias reduction. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1995, 4, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, D. Parameter selection method for support vector regression based on adaptive fusion of the mixed kernel function. J. Control. Sci. Eng. 2017, 2017, 3614790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal de Isabel II. Documento XYZT de la Presa de El Atazar; Internal Technical Report; Canal de Isabel II: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Itasca Consulting Group, Inc. FLAC3D: Fast Lagrangian Analysis of Continua in 3 Dimensions; Itasca Consulting Group, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ICOLD. Guidelines for Use of Numerical Models in Dam Engineering; International Commission on Large Dams: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, N.; Escuder Bueno, I. Effect of Contraction and Construction Joint Quality on the Static Performance of Concrete Arch Dams. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Escuder-Bueno, I.; Klun, M. System Reliability Analysis of Concrete Arch Dams Considering Foundation Rock Wedges Movement: A Discussion on the Limit Equilibrium Method. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofang, Z. Thermal Stresses and Temperature Control of Mass Concrete; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Léger, P.; Venturelli, J.; Bhattacharjee, S.S. Seasonal temperature and stress distributions in concrete gravity dams. Part 1: Modelling. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 1993, 20, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

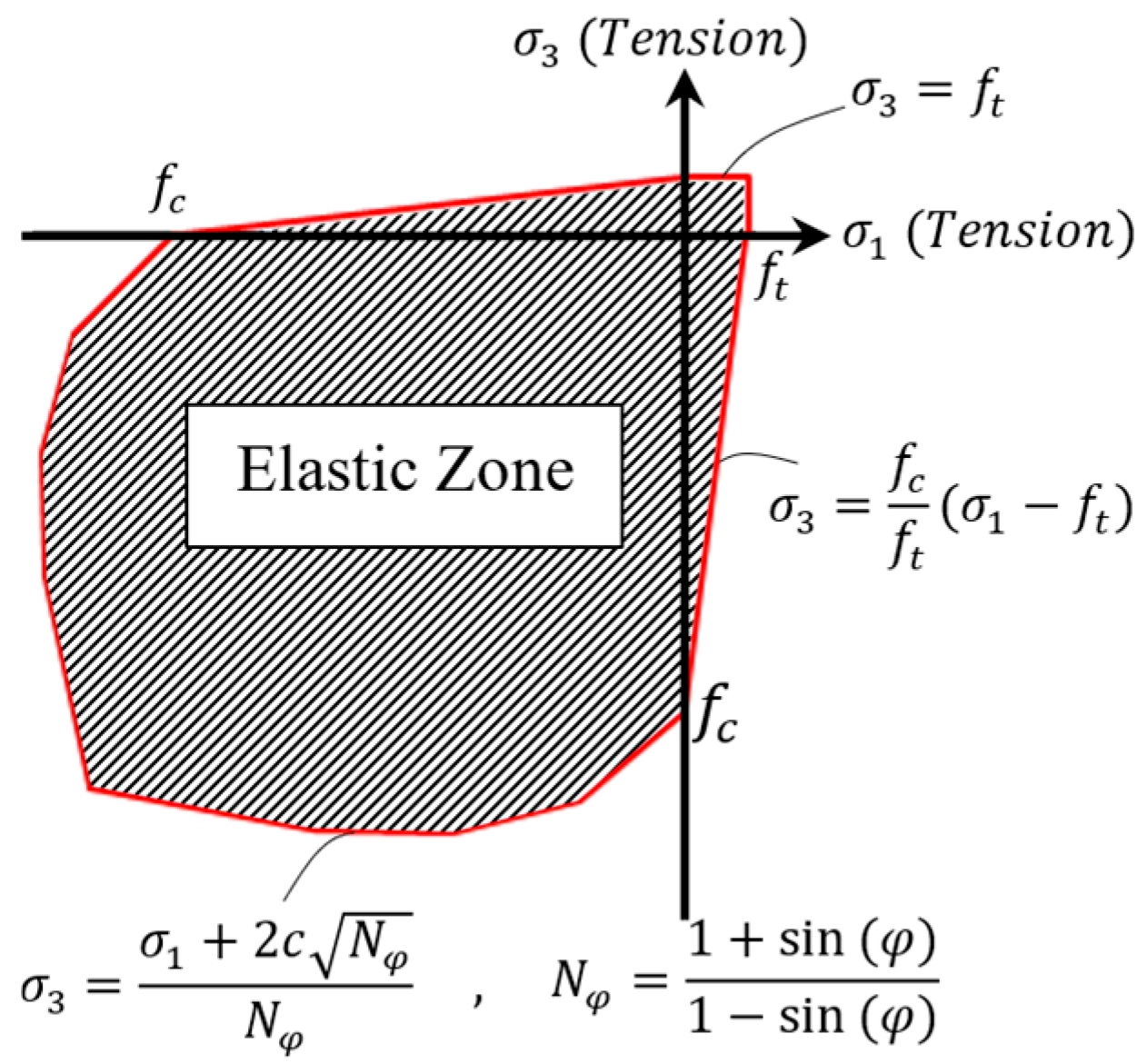

- Ahmadi, M.T.; Soltani, N. Mixing Regression-Global Sensitivity analysis of concrete arch dam system safety considering foundation and abutment uncertainties. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 139, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneghahi, M.H.; Alembagheri, M.; Soltani, N. Reliability and variance-based sensitivity analysis of arch dams during construction and reservoir impoundment. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2019, 13, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Alembagheri, M.; Khaneghahi, M.H. Risk-based probabilistic thermal-stress analysis of concrete arch dams. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2019, 13, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Yuan, D.; Wang, G. Optimized prediction model for concrete dam displacement based on signal residual amendment. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 78, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Gu, C.; Wei, B.; Qin, X.; Xu, W. A high-performance displacement prediction model of concrete dams integrating signal processing and multiple machine learning techniques. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 112, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, D.; Wand, M.P.; Holst, U.; HöSJER, O. Local polynomial variance-function estimation. Technometrics 1997, 39, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Zhai, W.; Deng, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, A. Temperature time-lag effect elimination method of structural deformation monitoring data for cable-stayed bridges. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 42, 102696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, C.O.; Alcay, S.; Ceylan, A. Displacement response of a concrete arch dam to seasonal temperature fluctuations and reservoir level rise during the first filling period: Evidence from geodetic data. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2016, 7, 1489–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretyak, K.; Palianytsia, B. Research of seasonal deformations of the Dnipro HPP dam according to GNSS measurements. Geodynamics 2021, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Sheng, J.; Jiang, C.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, H. Concrete dam deformation prediction model considering the time delay of monitoring variables. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Wen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, H. A multi-point joint prediction model for high-arch dam deformation considering spatial and temporal correlation. Water 2024, 16, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán, D.; Salete, E.; Toledo, M.Á. A new 1D analytical model for computing the thermal field of concrete dams due to the environmental actions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 85, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Algorithm | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 2025 | Variational Model Decomposition and Dynamic Time Warping | [38] |

| 2025 | Particle Swarm, EEMD-Wavelet Noise Reduction Algorithm | [39] |

| 2024 | XGBoost and TPE Optimization Algorithm | [40] |

| 2024 | Frequency-division decomposition and deep neural networks | [41] |

| 2023 | FEM *, Multi-Layer Perceptron | [31] |

| 2023 | Kriging Interpolation Method | [42] |

| 2022 | FEM *, Multipoint Hybrid, Multiple Linear Regression | [43] |

| 2022 | FEM *, Long Short-Term Memory Network, Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average | [44] |

| 2022 | Numerical model, Convolutional Neural Network, Long Short-Term Memory, Gated Recurrent Unit, Sparrow Search Optimization | [45] |

| 2022 | FEM *, Multiple Linear Stepwise Regression | [46] |

| 2021 | FEM *, Support Vector Machine, Particle Swarm Optimization | [47] |

| 2021 | FEM *, Hydraulic-Seasonal-Time-Based State Space Model, Kalman Filter Algorithm Optimization | [48] |

| 2021 | FEM *, Machine Learning Classification Model | [49] |

| 2020 | FEM *, Random Coefficient Model | [50] |

| 2020 | FEM *, Feature-Based Spatial Clustering | [51] |

| 2019 | FEM *, Kernel Partial Least Squares | [52] |

| 2019 | FEM *, Hydraulic-Hysteretic-Seasonal-Time Model | [53] |

| 2017 | FEM *, Unconstrained Lagrange Support Vector Regression, Culture Genetic Algorithm | [54] |

| 2011 | FEM *, Wavelet Networks, Rough Sets Theory | [23] |

| Variable | Calibrated Value |

|---|---|

| °C)) | 3.5 |

| Specific Heat (J/(kg °C)) | 967.0 |

| °C)) | 20.90 |

| (m) | 88.0 |

| (°C) | 6.5 |

| Delay Value (days) | 7.0 |

| Solar Radiation Effect (°C) | +3.0 |

| Variable | Concrete | Foundation | Vertical Joints | Peripheral Joint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | ||||

| E (GPa) | 30.0 * | 5.0 * | 15.0 * | - | - |

| ν | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.33 | - | - |

| ρ (kg/m3) | 2500 | 2850 | 2850 | - | - |

| (MPa) | 32.0 | - | - | - | - |

| (MPa) | 3.0 | - | - | - | 1.5 |

| Shear Stiffness (GPa/m) | - | - | - | 4.0 | 7.0 |

| Normal Stiffness (GPa/m) | - | - | - | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| (°) | 56.0 | - | - | 40.0 | 56.0 |

| C (MPa) | 4.9 | - | - | 0.0 | 3.0 |

| Expansion Coef. (1/°C) | * | - | - | - | - |

| Prediction Variable | MAE (cm) | MSE | RMSE (cm) | R | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitted | Predicted | Fitted | Predicted | Fitted | Predicted | Fitted | Predicted | |

| P1B1 | 0.120 | 0.125 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.159 | 0.151 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| P2B1 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.124 | 0.115 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Prediction variable | MAE (MPa) | MSE | RMSE (MPa) | R | ||||

| Fitted | Predicted | Fitted | Predicted | Fitted | Predicted | Fitted | Predicted | |

| N1 | 0.076 | 0.078 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.088 | 0.096 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| N2 | 0.056 | 0.073 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.066 | 0.092 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| N3 | 0.069 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.080 | 0.070 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Soltani, N.; Escuder-Bueno, I.; Galán, D. Prediction of Concrete Arch Dam Response Using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing. Infrastructures 2026, 11, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010009

Soltani N, Escuder-Bueno I, Galán D. Prediction of Concrete Arch Dam Response Using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing. Infrastructures. 2026; 11(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoltani, Narjes, Ignacio Escuder-Bueno, and David Galán. 2026. "Prediction of Concrete Arch Dam Response Using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing" Infrastructures 11, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010009

APA StyleSoltani, N., Escuder-Bueno, I., & Galán, D. (2026). Prediction of Concrete Arch Dam Response Using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing. Infrastructures, 11(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010009