Abstract

The safe and stable operation of ultra-high-voltage (UHV) transmission lines is fundamental to ensuring efficient and large-capacity power delivery. Critical fittings, as essential load-bearing components connecting towers, conductors, and insulator strings, are highly susceptible to damage under complex ice–wind conditions, thereby posing significant threats to grid security. To address the prevalent issues of jumper spacer breakage and conductor abrasion observed in field maintenance, a systematic finite element analysis model incorporating bundled conductors, jumper structures, and associated fittings was established. This model enabled comprehensive investigation of the effects of non-uniform ice accretion, wind loading, and ice-shedding impacts on the bearing characteristics of critical fittings. Through high-throughput computational simulations, a large-scale dataset capturing the bearing characteristics of jumper spacers was constructed. Based on this dataset, a damage risk assessment model under complex ice–wind conditions was developed using a multi-layer feedforward deep neural network (MLF-DNN). The results indicated that wind loading had a relatively minor influence on jumper spacers, whereas ice accretion and ice-shedding impacts were the dominant factors leading to damage. In particular, non-uniform ice-shedding readily induced unbalanced forces among sub-conductors, significantly increasing stress levels in jumper spacers and resulting in substantial risk. The proposed risk assessment model demonstrated high predictive accuracy and strong generalization capability, providing effective support for rapid evaluation and early warning of damage to fittings in UHV transmission lines under complex ice–wind environments.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

UHV transmission technology offers the advantages of large capacity, low loss, and long-distance delivery, serving as a vital means to achieve optimal allocation of energy resources and efficient operation of the power grid in China. However, since UHV lines often traverse complex terrains and harsh climatic regions, extreme environmental conditions pose severe challenges to the safe and reliable operation of transmission systems [1]. Among these, frequent ice–wind disasters have become a prominent issue, causing severe damage to key hardware fittings of transmission lines and thus threatening grid security [2]. In particular, in southwestern China and alpine regions, icing is characterized by large thickness and long duration, and it is often accompanied by strong wind loads and ice-shedding impacts. These combined effects can easily induce abrasion, fracture, and even structural failure of critical fittings, significantly endangering the safe and stable operation of the grid.

1.2. Literature Review

In response to the safety assessment of transmission lines under ice–wind conditions, many scholars have conducted extensive investigations. Fan et al. [3] examined the temperature characteristics of DC ice-melting conductors through experimental and numerical studies, offering guidance for conductor protection during ice-melting operations. Cai et al. [4] explored the aerodynamic characteristics of iced eight-bundle conductors under varying turbulence intensities in wind tunnel tests, while Cai et al. [5] further investigated the galloping behavior of D-shape iced six-bundle conductors in a full-scale tower-line system. Jiang et al. [6] conducted site experiments on suspension–tension arrangements to mitigate icing-induced tripping of transmission lines. Huang et al. [7] studied ice accretion on composite insulators and proposed anti-icing geometry optimization strategies. In addition, Liu et al. [8] developed simplified methods for galloping analysis of iced transmission lines, improving computational efficiency. Moreover, Zhang et al. [9] investigated the natural icing behavior of porcelain insulator strings at the Xuefeng Mountain test base and found that freezing rain and mixed rime processes cause more severe icing on the windward side, with icing thickness and mass closely related to wind speed, humidity, and shed geometry. Further, they [10] proposed optimized composite insulator designs with enlarged top sheds and modified shed combinations, demonstrating that these structures significantly reduce icicle bridging and contamination accumulation, improving anti-icing and anti-pollution performance by up to 30% compared with conventional designs.

Further progress has been made in recent years through advanced modeling and field validation. Dong et al. [11] proposed a calculation model of equivalent ice thickness on overhead lines considering ice and wind loads, which was verified with field data. Mou et al. [12] numerically assessed the anti-galloping efficiency of rotary clamp spacers for eight-bundle conductors. Hu et al. [13] investigated the influence of rainfall on the corona characteristics of AC transmission conductors, while Liu et al. [14] simulated ice-shedding and conductor breakage in tower-line systems using a co-rotational theory approach. Wu et al. [15] analyzed the dynamic responses of multi-span lines following ice-shedding and established prediction models using neural networks. Cai et al. [16] combined Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) with artificial neural networks to predict displacement responses of iced tower-line systems. Huang et al. [17] focused on the shadowing effect on bundled conductors during icing through simulations and tests. Liu et al. [18] applied data-driven identification methods to galloping models with different degrees of freedom. Teng et al. [19] proposed prediction models for dynamic responses of six-bundle conductors in ultra-heavy ice zones. Huang et al. [20] investigated ice-shedding jump heights through reduced-scale modeling tests. Collectively, these studies have significantly advanced understanding of icing, galloping, and ice-shedding phenomena in transmission lines; however, relatively little attention has been devoted to the safety and mechanical performance of hardware fittings.

As critical connectors between conductors, insulator strings, and towers, hardware fittings directly influence the mechanical performance and operational reliability of transmission lines. Wolf et al. [21] examined the numerical aspects of determining natural frequencies of transmission line cables equipped with in-line fittings, highlighting their importance in Aeolian vibration analysis. Zhang et al. [22] analyzed the wind-induced response of down-lead transmission line–connection fitting systems in UHV substations through finite element modeling and experiments, revealing the significant impact of connection fitting types and system configurations on mechanical properties under wind loads. Teng et al. [19] numerically investigated the dynamic response characteristics of six-bundle conductors in ultra-heavy ice regions using a nonlinear finite element model validated by scaled tests and established prediction models for jump height and transverse swing after ice-shedding, providing design guidance for insulation clearance and structural strength in heavily iced UHV corridors. Zhang et al. [23] proposed a non-unit protection scheme for flexible DC transmission lines based on fitting the rate of change in line-mode voltage reverse traveling waves, contributing to fault identification methods in transmission systems. Cai et al. [24] carried out topography optimization and buckling tests of tension plates in ultra-high-voltage direct current (UHVDC) transmission lines, identifying weak-bearing regions and providing guidance for structural reinforcement.

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence algorithms, particularly deep learning, has provided new approaches for solving complex engineering problems [25,26,27]. With powerful nonlinear mapping and data-driven capabilities, deep neural networks (DNNs) have demonstrated great potential in transmission line risk assessment. Wu et al. [28] applied a backpropagation (BP) neural network to investigate the dynamic characteristics of ice-shedding jumps in isolated-span transmission lines. Huang et al. [29] adopted multiple DNN algorithms to explore icing-induced disaster risks of transmission lines in mountainous areas. Against this backdrop, this study aims to evaluate the damage risk of critical hardware fittings in UHV transmission lines under complex ice–wind conditions by developing an intelligent assessment approach based on an MLF-DNN. This work not only holds theoretical significance but also provides practical guidance for field operation and maintenance.

1.3. Contribution and Organization of This Paper

This study investigates the loading characteristics and risk assessment of critical hardware fittings in UHV transmission lines under complex ice–wind coupling conditions. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

(1) A refined finite element (FE) model incorporating bundled conductors, jumper structures, and associated fittings is developed to accurately simulate the static and dynamic responses of hardware under ice accretion, wind loading, and ice-shedding impacts.

(2) A high-throughput numerical simulation framework, combined with Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), is employed to generate a large-scale dataset that comprehensively represents the mechanical behavior of jumper spacers under various coupled load scenarios.

(3) Based on the constructed dataset, an MLF-DNN model is proposed to assess the damage risk of key fittings. The model achieves high prediction accuracy and strong generalization capability, providing an efficient data-driven tool for structural risk evaluation and early warning.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the FEM-based model for fitting damage analysis and its validation. Section 3 analyzes the bearing characteristics of jumper spacers under ice–wind coupling. Section 4 develops the MLF-DNN-based risk assessment model and evaluates its performance. Section 5 concludes the main findings and provides future research perspectives.

2. FEM-Based Model for Fitting Damage Analysis

2.1. FEM Model Construction

Although jumper spacers are relatively small-sized connection components in transmission lines, the loading boundaries they experience under coupled ice–wind conditions are highly complex and strongly influenced by the overall structure. Building a simplified model for the spacer alone cannot comprehensively and accurately capture its actual stress state and potential bearing characteristics. To thoroughly analyze the load-bearing behavior of jumper spacers under complex ice–wind conditions and systematically understand their damage mechanisms and distribution patterns, it is necessary to establish a complete, system-level finite element model (FEM) that incorporates bundled conductors, jumper configurations, tension-string structures, suspension string structures, and associated fittings. Such a model can effectively reproduce the realistic structural environment and typical service boundaries of the hardware, thereby laying the foundation for subsequent numerical simulations and risk assessments.

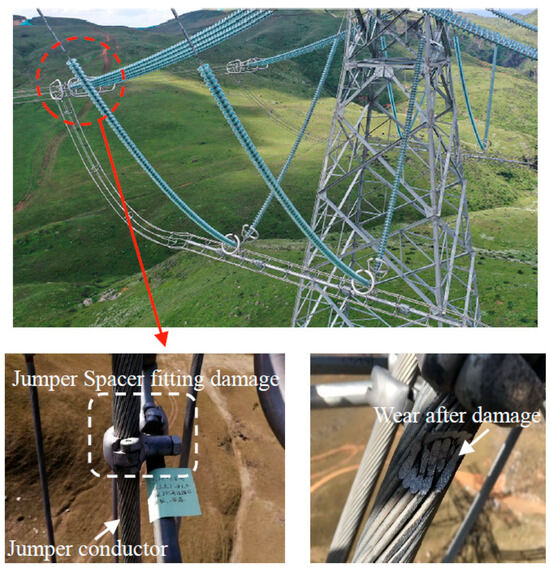

In this study, a representative UHV transmission line was selected as the research object, focusing on a tension section with a span length of 444 m and a height difference of 38 m. The main conductors are aluminum–clad steel-reinforced conductors (JLHA1/G2A-720/50), while the jumper lines adopt type JL/LB1A-720/50. The corresponding hardware fittings include conductor fittings (model N550PE) and jumper fittings (model TV210PE). The primary parameters of the conductor lines and jumper lines are the same and listed in Table 1. According to the filed observation as shown in Figure 1, the jumper spacer hardwires are of primary concern, which are made of ZL102 aluminum alloy, with a yield strength of 90 MPa and a tensile strength of 130 MPa.

Table 1.

Parameters of transmission line and jumper lines.

Figure 1.

Field schematic of damage and failure of jumper spacer hardware.

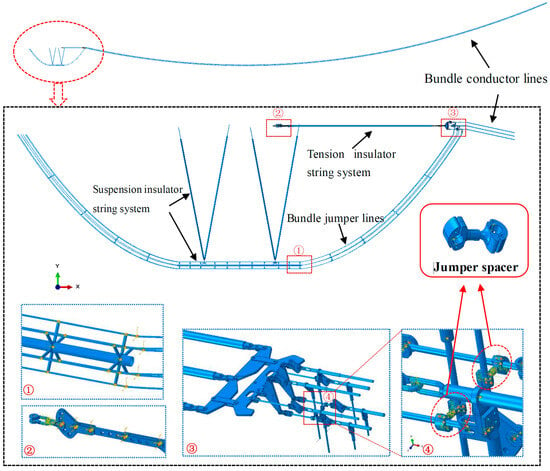

Given the high complexity of the overall system structure, finite element modeling in this study followed both blueprint fidelity and engineering simplification principles to ensure accuracy of the analysis while improving computational efficiency. Using ABAQUS 2023, the FEM model of the hardware–conductor–jumper coupled system is presented in Figure 2. Moderate simplifications were applied under the premise of preserving critical connections and mechanical characteristics, including (i) neglecting complicated connectors such as bolts and pins, which were instead represented using connector elements and constraint conditions to simulate connection and motion states; (ii) omitting geometric details with negligible mechanical influence, such as small holes, minor chamfers, and surface textures; (iii) simplifying components with limited impact on the mechanical response of hardware fittings, such as insulator disks and fine structural features of suspension strings; and (iv) excluding non-load-bearing parts, such as grading rings. Both conductor and jumper lines are modeled using beam elements, with detailed modeling procedures reported in ref. [27]. And all the fitting parts, including jumper spacer, conductor spacer, yoke plate, pull rod, hanging ring, etc., are modeled with entity elements. Due to space limitations, other modeling steps are not repeated here. The established system-level finite element model of the hardware–conductor–jumper assembly is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

FEM model of the hardware–conductor–jumper coupled system.

Although certain simplifications were introduced, the boundary conditions were carefully defined to accurately reproduce the real dynamic responses of the entire system under wind and ice-shedding excitations. Specifically, beam connectors with fixed constraints were applied between conductors and spacers, hinge connectors with rotational freedom were used to simulate bolt connections, and contact elements were defined between adjacent rings. Moreover, the ends of conductor lines, jumper lines, and tension strings that are connected with the tower are fixed. The ends of suspension strings are restricted in movement but are free in rotation. These boundary conditions collectively ensure the validity and accuracy of the model in simulating both static and dynamic responses of the structure under complex wind and ice-loading scenarios. The final model consists of 253 components and 89 connection relationships, with a total of approximately 366,000 elements, including 35,324 beam elements, 278,058 tetrahedral elements, and 53,236 hexahedral elements.

Regarding the loading configurations, wind and ice loads were applied to the conductors, jumper lines, and hardware fittings. Specifically, the self-weight of the entire model was represented by gravitational loading, the wind effects corresponding to different wind speeds were simulated using pressure loads, and the ice loads as well as ice-shedding processes were modeled by varying the gravitational load distribution in accordance with ref. [29].

Moreover, to ensure computational feasibility and enable high-throughput simulation, certain simplifications were introduced in the loading configurations. The wind load was applied as a steady-state pressure distribution along the conductors, jumpers, and fittings, aiming to evaluate the quasi-static stress response rather than fully dynamic aerodynamic interactions. Dynamic effects such as aerodynamic damping, wake-induced vibration, and galloping torque were not included in this stage, as they require fluid–structure interaction modeling beyond the current framework. Similarly, the ice-shedding process was represented by a sudden reduction in gravity load to simulate the detachment of ice mass, while adhesive fracture energy release and multi-span propagation effects were not considered. These simplifications allow for isolating the mechanical contributions of different load types and establishing a generalized and scalable framework for subsequent risk assessment modeling.

2.2. Validation of the Modeling Approach

As shown in Figure 2, the hardware–conductor–jumper assembly model developed in this study is highly complex, and complete experimental datasets for direct validation are not readily available. This work primarily aims to investigate the load-bearing characteristics of key hardware fitting under ice–wind conditions, particularly their mechanical response under ice-shedding impacts. To clarify the validation process, it should be noted that the sandbag ice-shedding test on the ground wire was primarily conducted to verify the jumping height and dynamic response characteristics of the mechanical system rather than to reproduce actual material damage. The purpose of this experiment is to confirm the validity of the modeling methodology and boundary conditions used in the FEM simulations. Given the large scale and complexity of the jumper spacer assembly, direct full-scale destructive testing under realistic ice–wind conditions is extremely difficult to perform. Therefore, the present validation serves as a physical reference for dynamic behavior rather than a point-by-point verification of stress distribution at critical locations such as end lugs and clevis holes.

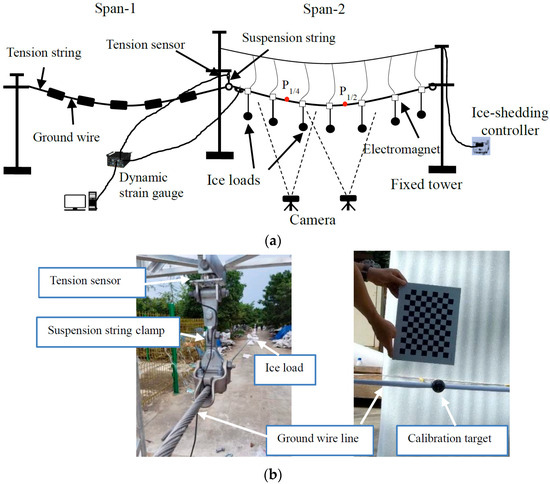

The experimental site was located at China Power Construction Group Chengdu Electric Power Fitting Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China, with a total length of approximately 140 m. Due to test conditions and site limitations, a two-span continuous ground wire–suspension string model was constructed, as illustrated in Figure 3. The span lengths were 70.2 m and 70.5 m, respectively, with no height difference. The initial tensile stress of the ground wire was set to 153 MPa, corresponding to a sag of 26.3 cm.

Figure 3.

Test model of ground wire in two consecutive spans after ice-shedding. (a) Test model. (b) Test site and calibration image.

The experimental platform consisted of four subsystems: (i) the ground wire–suspension string system, (ii) the ice-shedding control system, (iii) the tension measurement system, and (iv) the displacement measurement system. The ground wire–suspension string system included ground wires, suspension strings, tower foundations, and tension strings. Since tower deformation has a negligible effect on the dynamic response of conductors during ice-shedding, stiff steel frames were employed to simulate towers, and tower flexibility was neglected.

The ice-shedding control system comprised sandbags, electromagnets, and an ice-shedding controller, which are presented in Figure 3a. Sandbags of calibrated mass were used to simulate icing on the ground wire, while electromagnets were energized to hold the sandbags in place, simulating ice accretion. The release of sandbags by de-energizing the electromagnets simulated the ice-shedding process. The electromagnets were connected to a programmable controller, enabling various ice-shedding modes. In this study, particular emphasis was placed on complete-span ice-shedding scenarios.

The tension measurement system consisted of load cells and a dynamic strain gauge. A load cell, installed on the ground wire near the suspension string at the end of the ice-shedding span, was used to record tension variation during ice-shedding. The sensor had a measurement range of 0–10 t and a precision of 10 kg. The load cell was connected to the strain gauge to achieve real-time monitoring of tension fluctuations.

The displacement measurement system employed a high-precision digital camera, calibration board, marker points (Labled with red points in Figure 3a), and image-processing software, with detailed methods reported in ref. [20]. This setup allowed accurate recording of conductor displacement histories.

It is well known that the maximum ice-shedding jump height and the most severe impact loads typically occur under complete-span ice-shedding. Accordingly, this section focuses on the 100% ice-shedding case in the second span. Due to site limitations, it was not possible to conduct full-scale tests simulating heavy-icing conditions typical of severe climate regions. Fortunately, the primary objective of this chapter was to validate the finite element model rather than to reproduce extreme field conditions. Therefore, experiments were conducted for icing thicknesses of 10 mm and 20 mm, which provided sufficient validation for the simulation framework.

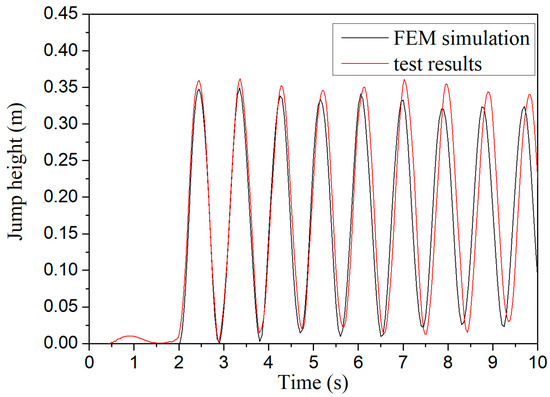

The comparisons of displacement time histories at the 1/2-span point under 10 mm ice accretion are presented in Figure 4, showing excellent agreement between experimental and simulated results. For brevity, time-history results under 20 mm ice thickness are not shown; instead, only the maximum jump heights are summarized, and the results are presented in Table 2. It shows the maximum ice-shedding jump heights obtained experimentally and numerically under 10 mm and 20 mm ice conditions. The maximum relative error was found to be 5.99%, indicating strong consistency between experimental and simulation results. This validates the reliability of the ground wire–suspension string finite element model and provides confidence for its application in subsequent dynamic analyses of key fittings under severe ice–wind conditions.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curve obtained by test and simulation under 10 mm ice thickness.

Table 2.

Comparison of jump height at typical points obtained by test and simulation.

In future work, static tensile and bending tests on full-scale or reduced-scale jumper spacer samples, with and without ice sleeves, will be conducted to experimentally verify the FEM-predicted stress concentrations at critical regions. These tests will further validate and enhance the engineering reliability of the proposed risk assessment framework for UHV transmission line fittings under complex ice–wind conditions.

3. Bearing Characteristics of Jumper Spacers

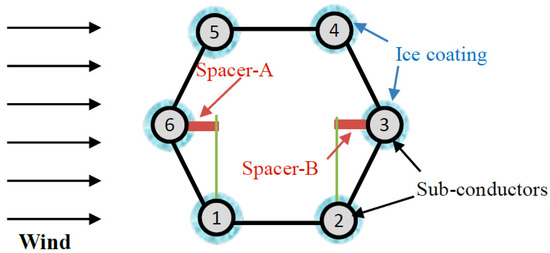

For the tension structure of six-bundle conductor lines, there are two symmetrically arranged jumper spacers, as illustrated in Figure 5. Under wind loading or non-uniform icing or ice-shedding impacts, the two spacers may experience different loadings. Therefore, in the following analysis, the mechanical response of both jumper spacers will be examined simultaneously.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of jumper spacer arrangement.

To illustrate the analysis procedure of the load-bearing characteristics of jumper spacers under ice–wind conditions, a representative case was selected. Since ice accretion is closely related to wind speed, the sub-conductors on the leeward side are influenced by the wake flow of the windward side, resulting in relatively smaller ice thickness [17]. Therefore, a non-uniform icing scenario was considered, where sub-conductors 1, 5, and 6 were assigned an ice thickness of 30 mm, while sub-conductors 2, 3, and 4 were assigned 20 mm. The stress response of jumper spacers under both static ice loads and ice-shedding jump conditions was investigated.

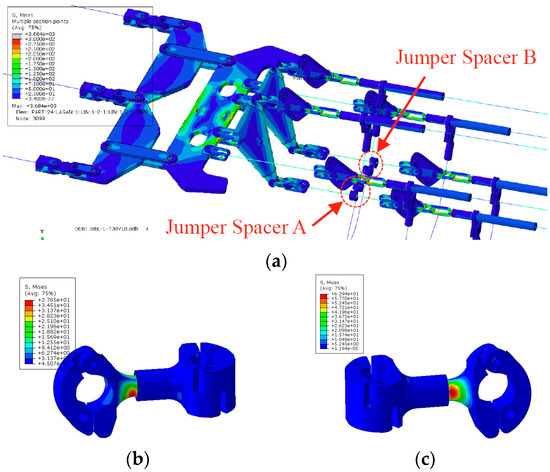

By applying the above non-uniform ice load under self-weight, the stress distribution of the hardware–conductor–jumper system was obtained. The stress contours of the jumper spacer region under static icing are shown in Figure 6. It can be observed that the maximum von Mises stress of spacer A was 37.5 MPa, whereas that of spacer B reached 62.9 MPa. These results indicate that non-uniform icing induces significant unbalanced forces in the tension structure, leading to uneven stress between the two spacers. The weakest locations were consistently found at the connection regions, which agrees well with field failure observations.

Figure 6.

Stress distribution of jumper spacers under non-uniform ice accretion. (a) General stress distribution of part of tension string. (b) Jumper spacer A on the windward side. (c) Jumper spacer B on the windward side.

To conduct a detailed analysis of the influencing factors, the load-bearing characteristics of critical hardware were investigated under varying wind speeds, wind directions, ice thicknesses, and degrees of non-uniform icing. The degree of non-uniform icing U is defined as U = Tleeward/Twindward, where T denotes the ice thickness. In this study, the windward sub-conductor was assumed to have an ice thickness of 30 mm.

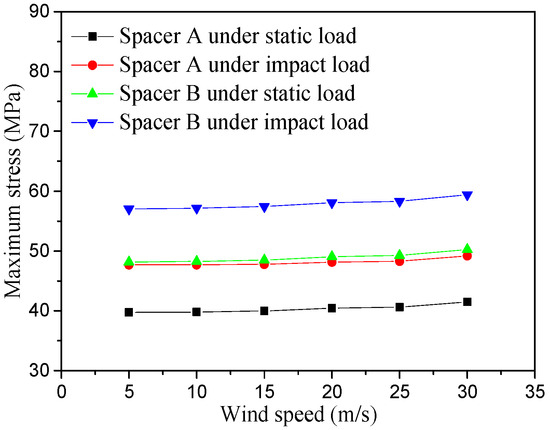

First, the effect of wind speed on the load-bearing performance of jumper spacers was examined. Under the condition of 30 mm ice thickness, static maximum stress values and maximum stress under ice-shedding impact were analyzed at wind speeds of 5 m/s, 10 m/s, 15 m/s, 20 m/s, 25 m/s, and 30 m/s. The results, as shown in Figure 7, indicate that the maximum stress in spacer B is consistently greater than that in spacer A, while variations in wind speed exert relatively minor influence on the maximum stresses of both spacers.

Figure 7.

Effect of wind speed on the maximum stress of hardware under ice–wind coupling conditions.

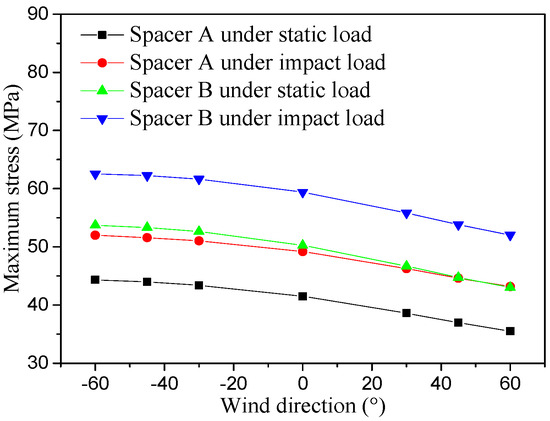

The effect of wind direction on the load-bearing characteristics of jumper spacers under coupled ice–wind conditions is illustrated in Figure 8. In this case, an ice thickness of 30 mm and a wind speed of 30 m/s were applied, and the influence of varying wind direction angles on the maximum static stress and the instantaneous maximum stress during ice-shedding impacts was examined. It was found that the maximum stress of the spacers decreased as the wind direction angle increased. However, all stress values remained below the yield strength of the material, indicating that the operating condition was within a safe range.

Figure 8.

Effect of wind direction on the maximum stress of hardware under ice–wind coupling conditions.

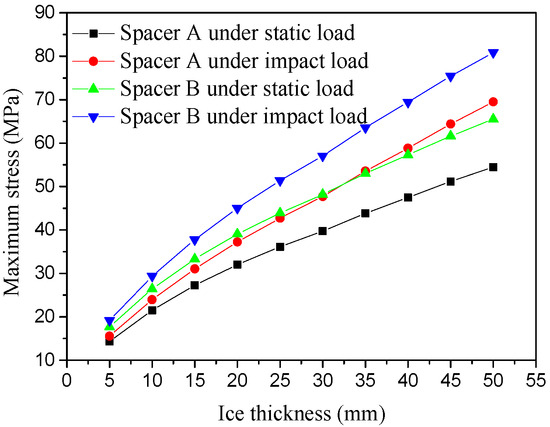

To investigate the influence of ice accretion, two scenarios were considered: (i) uniform ice thickness across all sub-conductors and (ii) non-uniform ice distribution among sub-conductors. In Figure 9, the variation in maximum stress in jumper spacers under ice thicknesses ranging from 5 mm to 50 mm is illustrated. It can be observed that the maximum stress increased significantly with the growth of ice thickness. When the ice thickness reached 50 mm, the maximum stress of spacer B under ice-shedding impact was 83.5 MPa, approaching the yield strength of the material. After considering non-uniform icing, the results are shown in Figure 10. When the degree of non-uniform icing was 1.1, the instantaneous maximum stresses of spacers A and B under ice-shedding impact reached 104.0 MPa and 132 MPa, respectively, both exceeding the tensile strength of the material and indicating a considerable safety risk.

Figure 9.

Effect of ice thickness on the maximum stress of hardware under ice–wind coupling conditions.

Figure 10.

Effect of non-uniform ice accretion on sub-conductors on the maximum stress of hardware.

It should be noted that the present study focuses on the quasi-static mechanical responses of critical fittings under coupled ice–wind conditions. The exclusion of aerodynamic damping, galloping torque, and adhesive fracture mechanics represents a trade-off between model complexity and computational efficiency. In future work, the model will be further enriched by incorporating aerodynamic–structural coupling, multi-span dynamic propagation, and fracture energy considerations to improve its physical fidelity and predictive capability under real ice–wind environments.

4. Risk Assessment Model for Hardware Load-Bearing Capacity

4.1. Data Acquisition

To construct a hardware risk assessment model with high accuracy and strong generalization capability, the Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) method was employed to generate combinations of key parameters. Compared with conventional random sampling, LHS ensures a more uniform distribution of samples in multidimensional space, reduces the risk of clustering, and improves the efficiency and accuracy of model training. Furthermore, LHS enables better coverage of extreme cases and representative engineering scenarios under a limited number of samples, making it more suitable for complex engineering problems.

The parameter selection [30] was determined based on typical engineering scenarios and actual operating conditions. Seven key influencing factors were considered, namely ice thickness (T), wind speed (V), wind direction angle (α), degree of non-uniform icing on windward sub-conductors (U1), degree of non-uniform icing on leeward sub-conductors (U2), ice-shedding ratio (R), and non-uniform ice-shedding state (S), as summarized in Table 3. These factors accounted for various loading conditions and their dynamic responses under ice–wind coupling. The range of T was set to 0–50 mm to reflect heavy-icing scenarios; wind speed was set to 0–30 m/s; differences in icing thickness between windward and leeward sub-conductors were included to characterize non-uniform icing; the effect of ice-shedding ratio was also incorporated; and to capture ice-shedding jumps, particularly under non-uniform shedding, a specific condition was designed in which ice was assumed to shed from windward sub-conductors while remaining on leeward ones. The chosen parameter ranges therefore covered both typical and extreme icing conditions, wind loading conditions, and non-uniform ice-shedding cases encountered in engineering practice, ensuring representativeness and applicability of the analysis results.

Table 3.

Condition design and parameter selection ranges.

Using LHS, 800 computational samples were generated. These samples were simulated using the hardware–conductor–jumper coupled finite element model established in Section 2.1. Large-scale numerical analyses were performed under both static load and dynamic ice-shedding impact conditions. For each case, the maximum stress values of jumper spacers A and B under static and dynamic states (denoted as MA1, MA2, MB1, and MB2, respectively) were extracted. After data post-processing and elimination of unconverted cases, a comprehensive dataset was constructed, consisting of 760 valid samples that characterize the load-bearing behavior of key hardware and support damage risk assessment under complex ice–wind conditions.

To further verify the representativeness and uniformity of the generated dataset, the sampling distribution was visualized, as shown in Figure 11. The figure illustrates the two-dimensional and three-dimensional distributions of the samples with respect to the key parameters—ice thickness (T), wind speed (V), and wind direction angle (α). It can be clearly observed that the samples are uniformly distributed across the entire parameter space, confirming that the LHS method effectively ensures comprehensive coverage of typical and extreme conditions. This uniform distribution eliminates the possibility of class imbalance and guarantees that the generated dataset fully captures the diverse mechanical responses of the fittings under complex ice–wind coupling effects.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the sample distribution. (a) Two dimensions. (b) Three dimensions.

4.2. Model Construction Based on MLF-DNN

To enable efficient prediction of the damage risk of critical hardware in UHV transmission lines under complex ice–wind conditions, a regression model was constructed using MLF-DNN performed in Python 2.7 with the TensorFlow and Scikit-learn libraries. The maximum stress responses of jumper spacers under different ice–wind loading scenarios were modeled. By mapping input variables through multiple neural layers, this method provides strong capabilities in high-dimensional modeling, nonlinear representation, and generalization, making it particularly suitable for complex engineering systems where sample size is limited but input dimensionality is high.

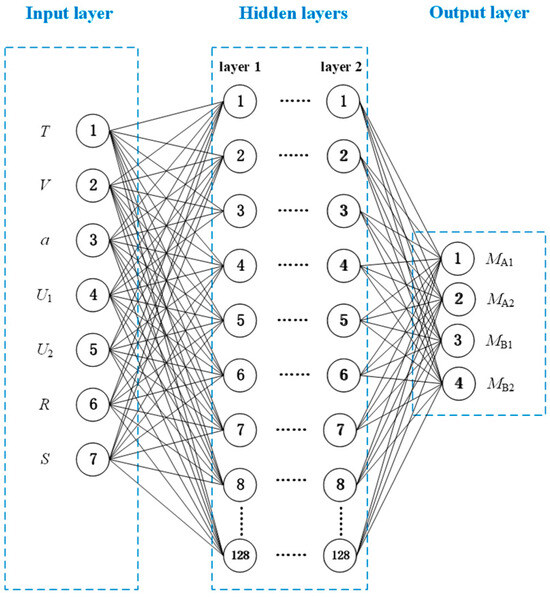

As illustrated in Figure 12, the developed MLF-DNN model consists of an input layer, two hidden layers, and an output layer. The input layer contains seven nodes, corresponding to the seven influencing parameters defined in Section 4.1, while the output layer consists of four nodes, namely MA1, MA2, MB1, and MB2. Each hidden layer contains 128 neurons, and the rectified linear unit RELU function and sigmoid function are employed as the activation functions to enhance nonlinear representation and accelerate convergence. To prevent overfitting and improve model robustness, min–max scaling was applied to normalize all inputs (seven dimensions) and outputs (four dimensions), linearly mapping them into the range of [0, 1], as expressed below:

in which x denotes the original value, and x′ represents the normalized value.

Figure 12.

Neural network architecture based on MLF-DNN.

To enhance the training effectiveness and generalization capability of the model, the dataset was divided into training and testing sets in a ratio of 8:2. During the parameter optimization stage, the GridSearchCV method in the Scikit-learn library was employed to systematically search for key hyper-parameters of the neural network (such as learning rate, batch size, and number of hidden-layer neurons). A 10-fold cross-validation strategy was used to evaluate model performance under different parameter combinations, thereby improving the robustness and generalization capability of the model across various loading conditions.

After the optimal parameter configuration was determined, the MLF-DNN model was retrained on the full training set. Regularization constraints and feature weight control mechanisms were incorporated to further suppress overfitting and enhance both stability and generalization. As a result, a damage risk assessment model for critical hardware under complex ice–wind conditions was successfully developed.

4.3. Evaluation of the Risk Assessment Model

To evaluate the predictive performance and generalization capability of the MLF-DNN model, the mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), and coefficient of determination (R2) were adopted as evaluation metrics:

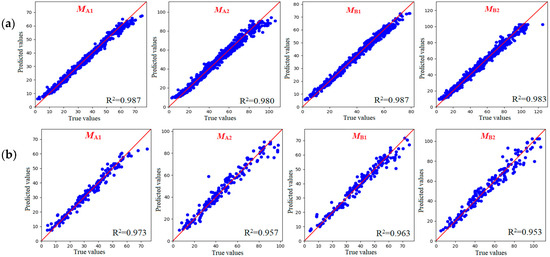

When the MAE and MSE values approach zero and the R2 value approaches one, the surrogate model can be regarded as having strong generalization capability. Figure 13 illustrates the comparison between the predicted and simulated stress values for the training set (Figure 13a) and the testing set (Figure 13b), where the horizontal axis represents the simulated true stress values and the vertical axis represents the predicted values obtained from the model.

Figure 13.

Prediction accuracy of the MLF-DNN-based risk assessment model: (a) training set; (b) testing set.

It can be observed that the model exhibited good fitting performance and high prediction accuracy across all four output variables (MA1, MA2, MB1, and MB2). For the training samples, the R2 values of all output indices exceeded 0.98, indicating that the model was able to effectively capture the complex nonlinear mapping relationships between high-dimensional inputs and outputs. For the testing samples, the model also maintained strong predictive performance with comprehensive R2 values of 0.961, and specifically 0.973 (MA1), 0.957 (MA2), 0.963 (MB1), and 0.953 (MB2), demonstrating that the model possessed robust generalization capability on unseen data.

In addition, the red diagonal line in the figure represents the ideal prediction scenario, where the predicted values are identical to the true values. Most of the data points are concentrated near this diagonal line, with relatively small prediction errors, which confirms that the MLF-DNN model was able to accurately reproduce the stress responses of jumper spacers under both static and dynamic loading conditions.

Moreover, to further evaluate the predictive performance and robustness of the proposed MLF-DNN model, two additional ensemble learning algorithms, including Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost, were employed for comparison. These algorithms were trained and validated using the same dataset and parameter settings to ensure fairness in evaluation. The comparative results are summarized in Table 4, from which it can be observed that the MLF-DNN model achieves the highest predictive accuracy, with R2 = 0.961, MSE = 0.006, and MAE = 0.019, outperforming RF (R2 = 0.940) and XGBoost (R2 = 0.946).

Table 4.

Comparison of models obtained by different algorithms.

The superior performance of the MLF-DNN model is mainly attributed to its deep hierarchical feature extraction and nonlinear representation capabilities, which allow it to capture complex interactions between multiple ice–wind parameters and the resulting mechanical responses of the fittings. In particular, compared with traditional tree-based methods, the MLF-DNN exhibits better generalization when modeling coupled dynamic processes, where nonlinear dependencies and cross-effects between ice thickness, wind speed, and ice-shedding ratio become significant.

Therefore, it is demonstrated that the MLF-DNN model, while maintaining high prediction accuracy, also possesses strong stability and robustness, making it effective for assessing the load-bearing risks of hardware under static and ice-shedding dynamic conditions with multidimensional ice–wind coupled inputs.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the damage risk of critical hardware fitting in UHV transmission lines under complex ice–wind conditions was investigated. An FEM model incorporating the coupling effects of conductors, jumpers, and hardware fittings was established. A high-quality large-sample dataset was generated using the LHS method. On this basis, a damage risk assessment model for key hardware fitting was developed using the MLF-DNN, enabling prediction of the load-bearing risks of jumper spacers under both static and dynamic ice-shedding conditions. The following conclusions were drawn:

(1) An FEM model covering bundled conductors, jumper structures, and associated fittings was constructed for the first time, and the risk assessment of maximum bearing stress of jumper spacers under icing, wind loading, and ice-shedding impacts in complex ice–wind conditions was realized.

(2) The bearing risks of jumper spacers under static loading and ice-shedding impacts in complex ice–wind conditions were clarified. It was found that ice accretion and ice-shedding impacts exerted significant influence, whereas the effects of wind speed and wind direction were relatively minor.

(3) Non-uniform icing and non-uniform ice-shedding were shown to easily induce unbalanced forces, which are critical factors affecting the bearing performance of jumper spacers.

(4) A damage risk assessment model for critical hardware based on MLF-DNN was established, demonstrating strong nonlinear fitting capability and generalization performance. The model can provide effective support for rapid damage risk assessment and early warning of critical hardware in UHV transmission lines under complex ice–wind conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. (Zhiguo Li) and D.L.; methodology, Z.L. (Zhiguo Li); software, Z.L. (Zhiguo Li); validation, Z.L. (Zhiyi Liu); investigation, G.Y.; data curation, G.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. (Zhiguo Li); writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, Z.L. (Zhiyi Liu); supervision, G.H.; project administration, Z.L. (Zhiyi Liu); funding acquisition, Z.L. (Zhiyi Liu) and G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Funding Project of China Southern Power Grid, grant number CGYKJXM20220333.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Some of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the constructive comments and suggestions from the anonymous reviewers, which helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Z.L. (Zhiguo Li), G.Y., D.L. and X.Z. were employed by the company China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd., Author Z.L. (Zhiyi Liu) was employed by the company Powerchina Chengdu Electric Power Fittings Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UHV | ultra-high-voltage |

| UHVDC | ultra-high-voltage direct current |

| MLF-DNN | multi-layer feedforward deep neural network |

| FEM | finite element model |

| LHS | Latin Hypercube Sampling |

References

- Papailiou, K.O. Overhead Lines; Springer Nature: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, P.; Havard, D.; Laneville, A. Effect of Ice and Snow on the Dynamics of~Transmission Line Conductors. In Atmospheric Icing of Power Networks; Farzaneh, M., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 171–228. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Jiang, X.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shu, L. Temperature characteristic of DC ice-melting conductor. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 65, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Liu, X.; Huang, H. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Iced 8-bundle Conductors under Different Turbulence Intensities. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4812–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Yang, X.; Huang, H.; Zhou, L. Investigation on Galloping of D-Shape Iced 6-Bundle Conductors in Transmission Tower Line. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhu, M.; Dong, L.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J. Site experimental study on suspension-tension arrangement for preventing transmission lines from icing tripping. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 119, 105935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Virk, M.S. Ice accretion study of FXBW4-220 transmission line composite insulators and anti-icing geometry optimization. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 194, 107089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Min, G.; Cai, M.; Yan, B.; Wu, C. Two Simplified Methods for Galloping of Iced Transmission Lines. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yue, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Zeng, W. Growth characteristics and influence analysis of insulator strings in natural icing. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 228, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jing, S.; Pang, G.; Gao, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Jiang, X. Performance analysis of novel anti-pollution and anti-icing composite insulators. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 241, 111350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Jiang, X.; Xiang, Z. Calculation model and experimental verification of equivalent ice thickness on overhead lines with tangent tower considering ice and wind loads. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 200, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; Yan, B.; Yang, H.; Wu, K.; Wu, C.; Yang, X. Study on anti-galloping efficiency of rotary clamp spacers for eight bundle conductor line. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 193, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Shu, L.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, X. Effects of rainfall on the corona characteristics of AC single conductor of 110 kV transmission lines. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Ye, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhang, B.; Lv, Z. Research on ice shedding and broken conductor in tower-line system based on CR method. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 222, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yan, B.; Yang, H.; Liu, Q.; Lu, J.; Liang, M. Characteristics of multi-span transmission lines following ice-shedding. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 218, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Bao, W.; Tian, B.; Yang, S.; Min, G. Displacement response prediction of eight-bundle transmission tower-line system combining Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) and ANNs. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, Z.; Ouyang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Virk, M.S. Study on icing characteristics of bundled conductor of transmission line based on shadowing effect analysis. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, C.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, B.; Tao, Y. Research on parameter identification of transmission line galloping model under different degrees of freedom. Appl. Math. Modell. 2025, 140, 115899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhou, X.; Yang, H.; Gao, Y.; Wu, K.; Deng, H. Response characteristic parameters of six-bundle conductor lines in ultra-heavy ice zones following ice-shedding. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Yan, B.; Wen, N.; Wu, C.; Li, Q. Study on jump height of transmission lines after ice-shedding by reduced-scale modeling test. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 165, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, H.; Singer, S.; Pustaić, D.; Alujević, N. Numerical aspects of determination of natural frequencies of a power transmission line cable equipped with in-line fittings. Eng. Struct. 2018, 160, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shang, R.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xie, K.; Zhang, B. Analysis of wind-induced response of down lead transmission line-connection fitting systems in ultrahigh-voltage substations. Eng. Struct. 2020, 206, 110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z. Non-unit protection scheme for flexible DC transmission lines based on fitting the rate of change of line-mode voltage reverse traveling waves. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 164, 110415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Yan, B.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, B. Topography Optimization and Buckling Test of Tension Plates in UHVDC Transmission Lines. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 1462–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, A.; Liu, Z.; Tang, R.; Huang, G. Tree-Based Surrogate Model for Predicting Aerodynamic Coefficients of Iced Transmission Conductor Lines. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wu, G.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wei, W. Development of surrogate models for evaluating energy transfer quality of high-speed railway pantograph-catenary system using physics-based model and machine learning. Appl. Energy 2023, 333, 120608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Yan, B.; Mou, Z.; Huang, G.; Yang, H.; Lv, X. Prediction models for dynamic response parameters of transmission lines after ice-shedding based on machine learning method. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 202, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yan, B.; Yang, H.; Lu, J.; Xue, Z.; Liang, M.; Teng, Y. Dynamic Response Characteristics of Isolated-Span Transmission Lines After Ice-Shedding. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 3519–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wu, G.; Guo, Y.; Liang, M.; Li, J.; Dai, J.; Yan, X.; Gao, G. Risk assessment models of power transmission lines undergoing heavy ice at mountain zones based on numerical model and machine learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard, D.; Diana, G.; Vinogradov, A.; Cosmai, U.; Halsan, K.; Krispin, H.-J.; Mito, M.; Sunkle, D.; Dulhunty, P. State of the Art Survey On Spacers and Spacer Dampers 277; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).