Abstract

Glaucoma is recognized as the second leading cause of blindness globally and a primary cause of irreversible blindness, estimated to affect over 80 million patients worldwide, including 4.5 million in the United States. Though the disease is multifactorial, the primary cause is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), which damages the optic nerve fibers that connect the eye to the brain, thus interfering with the quality of vision. Current treatments have evolved, which consist of medications, laser therapies, and surgical interventions such as filtering procedures, glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs), and current innovations of minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS). This paper aims to discuss the history and evolution of the design and biomaterials employed in GDDs and MIGS. Through a comprehensive review of the literature, we trace the development of these devices from early concepts to modern implants, highlighting advancements in materials science and surgical integration. This historical analysis, ranging from the mid-19th century, reveals a trend towards enhanced biocompatibility, improved efficiency in IOP reduction, and reduced complications. We conclude that the ongoing evolution of GDDs and MIGS underscores a persistent commitment to advancing patient care in glaucoma, paving the way for future device innovations and therapeutic trends to treat glaucoma.

1. Introduction

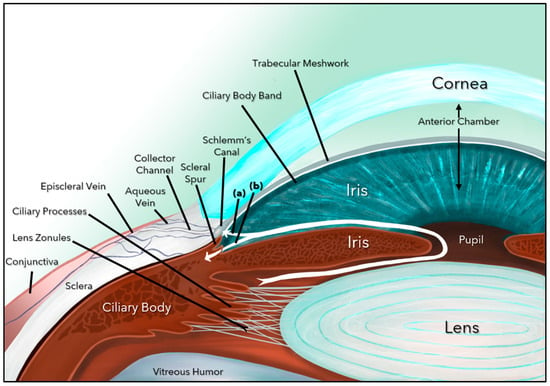

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally and is challenging both in terms of its diagnosis and controlling its progression [1,2]. There are several forms of glaucoma (primary, secondary, angle closure, childhood, juvenile, and adult), but the most common form (60–70%) is primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), a progressive, chronic optic neuropathy caused by damage to the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and their axons (nerve fiber layer), which ultimately form the optic nerve (ON) [2,3]. Glaucoma is multifactorial, and the major risk factors include elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), thin central corneal thickness, older age, African descent, family history of glaucoma, and systemic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea [2,3,4]. Elevated IOP, the most modifiable risk factor, is caused by blockage of the aqueous humor (AH) outflow at the level of the trabecular meshwork (TM) and beyond (Schlemm’s Canal, episcleral vessels, and aqueous veins), including damage to the uveoscleral outflow pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Aqueous humor dynamics. Aqueous humor formed by the ciliary body follows a circuitous pathway to the anterior chamber via the posterior chamber, pupil, and ultimately exits through the trabecular meshwork (a) and the uveoscleral pathway (b).

Current treatments aim to reduce IOP through medications, laser procedures, or surgery [2,3]. The IOP lowering medications are relatively effective in managing mild to moderate glaucoma, but this treatment modality is also strongly associated with toxicity, high costs, and patient nonadherence [2,3]. Conversely, surgery is mostly used in the advanced stages of glaucoma, as its outcomes are unpredictable and has inherent vision-threatening complications. Surgical interventions or filtering procedures include trabeculectomy, glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs), and newer microinvasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) [5,6,7,8]. Surgical options have evolved and improved over time, given the concurrent advancements in surgical microscope magnification, retinal and ON imaging, histopathology, pathophysiology of glaucoma, epidemiology, and biomaterials science [7,8,9]. With continual developments in medical science, the choice of biomaterial in IOP management has become critical as it directly impacts device performance, tissue response, fibrosis, patency, and the risk of complications [10,11,12].

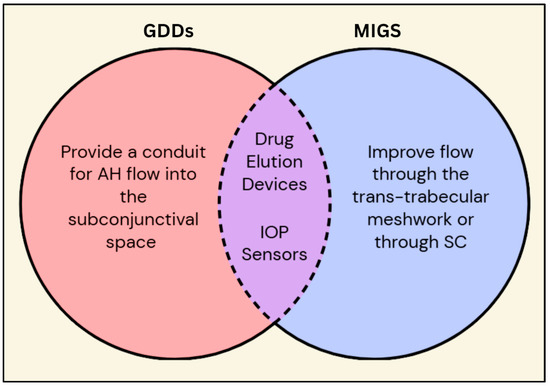

For this paper, we aim to delineate the structural and functional distinctions between GDDs and MIGS. GDDs are ocular implants that function to lower IOP by shunting AH from the anterior chamber (AC) to the external subconjunctival drainage space forming a fluid filled pocket (bleb) [5]. Conversely, MIGS aim to reduce IOP through a minimally invasive approach (either ab interno or ab externo) [6]. Currently, MIGS are indicated for mild to moderate POAG in combination with cataract surgery or as a standalone procedure (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram comparing and contrasting GDDs and MIGS. Besides the individual characteristics of the GDDs and MIGS, they both have common features such as prolonged drug delivery and continuous IOP measurements via embedded sensors. Legend: GDDs = glaucoma drainage devices; MIGS = minimally invasive glaucoma surgery; AH = aqueous humor; IOP = intraocular pressure; SC = Schlemm’s canal.

The purpose of this paper is to review the history and evolution of GDDs and MIGS from biomaterial and design perspectives, highlight emerging materials with potential to improve outcomes and reduce complications. In short, our research aims to provide the ophthalmic community with a more comprehensive understanding of how GDDs and MIGS have developed, what their shortcomings are, and how they can be further augmented to meet the growing needs and future challenges of glaucoma.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Search

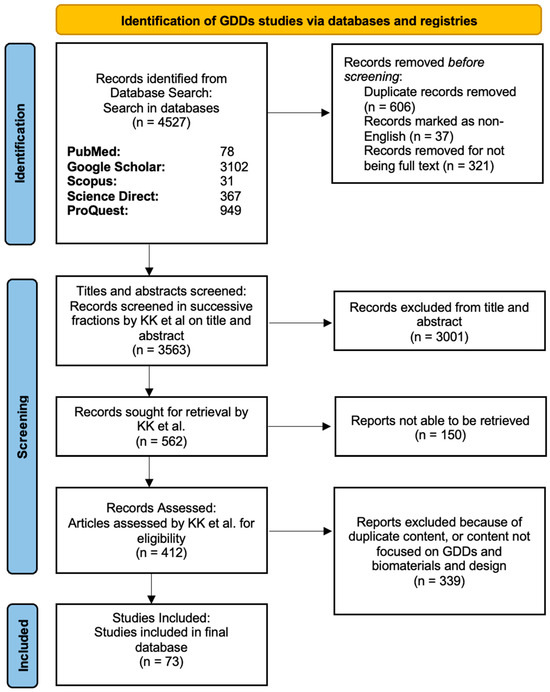

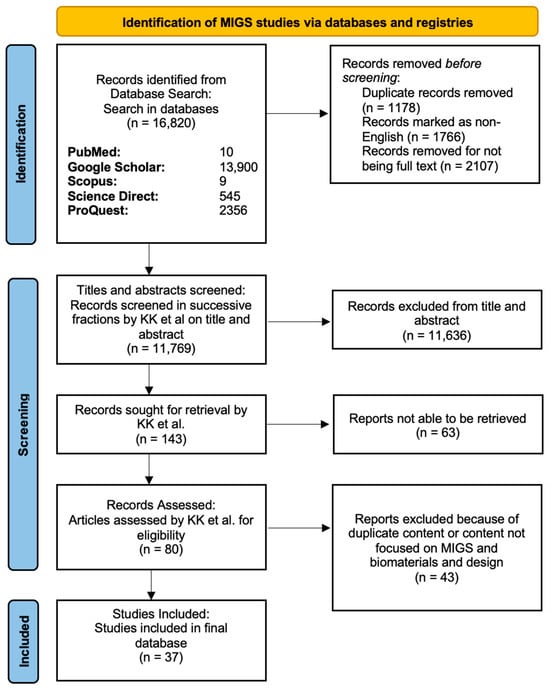

We followed the standards outlined by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (www.prisma-statement.org) (accessed on 9 December 2025) during data collection. For the GDDs search, we used keywords and MeSH terms such as “glaucoma drainage device” (or “GDD”), “glaucoma drainage implant”, “biomaterials”, and “biocompatible” (Figure 3). For the MIGS search, we used keywords and MeSH terms such as “minimally invasive glaucoma surgery” (or “MIGS”), “microinvasive glaucoma surgery”, “biomaterials”, and “biocompatible” (Figure 4). The PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study) framework (https://libguides.mssm.edu/ebm/ebp_pico) (accessed on 9 December 2025) was used to create eligibility criteria (Table 1).

Figure 3.

PRISMA diagram showing the screening process in the GDDs article search. In the stepwise flowchart, the exclusion criteria and number of articles removed are shown.

Figure 4.

PRISMA diagram showing the screening process in the MIGS article search. In the stepwise flowchart, the exclusion criteria and number of articles removed are shown.

Table 1.

PICOS Criteria for inclusion of studies.

Using these keywords and MeSH terms, we systematically searched the online databases of PubMed (MEDLINE), Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Google Scholar, and ProQuest up to June 2025. The results from the different databases were downloaded and saved as a comma-separated values (CSV) file and then compiled together on Google Sheets. We created a customized Python (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA, version 3.9.23) based script and downloaded all the references from Google Scholar in one file. The results were entered into two different Google Sheets: one for GDDs and the other for MIGS.

2.2. Protocol Registration

This review was not prospectively registered in PROSPERO or any other database of systematic review protocols. The scope of the review was refined iteratively in collaboration with the study authors to align with the evolving classification and engineering landscape of GDDs and MIGS.

2.3. Preliminary Screening

The fully compiled GDDs and MIGS list from Google Sheets was then input separately into Rayyan AI (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA https://www.rayyan.ai/) (accessed on 9 December 2025), a web-based platform, and we applied the same inclusion and exclusion criteria for both. The Rayyan AI was only used as a tool for storing the articles gathered during the systematic review and efficiently performing manual screening of the articles. The exclusion criteria included non-English articles, reports from conferences, abstracts, commentary, and duplicate papers with the same digital object identifier (DOI).

2.4. Eligibility Assessment, Data Extraction, and Synthesis Methods

The remaining manuscripts were carefully screened (KK, HT, NS, AS, NW, PJ, SB, AS) for eligibility assessment using information on authors, title, date of publication, journal, and DOI. Only full-text English articles, studies involving human and animal subjects, and clinical trials were selected. For each included study, the following data items were extracted: publication year, study type (clinical, preclinical, or materials-based), device or implant name, and country of development. Technical parameters included implant composition, material type, physical configuration, and device dimensions where available. Clinical or performance-related outcomes such as mean intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction, number of anti-glaucoma medications postoperatively, and reported complications were also recorded when presented. In cases where quantitative data were unavailable, qualitative descriptors of device performance or material properties were used instead. Data were extracted manually by two independent reviewers and verified for accuracy. Given the heterogeneity of study designs, we used narrative synthesis organized chronologically by device type to synthesize the information.

2.5. Risk of Bias, Reporting Bias, and Certainty Assessment

Because this review included a heterogeneous mixture of clinical studies, early-stage prototypes, and engineering-based reports, a formal risk-of-bias assessment (e.g., Cochrane ROB 2 or ROBINS-I) was not feasible. Instead, methodological quality was qualitatively evaluated based on study design, clarity of outcome reporting, and reproducibility of experimental methods. Reporting bias was not formally assessed given the engineering nature of the included studies, which often focused on device design and material performance rather than clinical outcomes. Similarly, certainty assessment of the evidence was not applicable to this review, as quantitative pooling or grading of comparative results was not performed.

3. Results

After multiple rounds of screening and combining the articles from the GDDs and MIGS searches, 110 studies were included in our final review (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

3.1. Introduction to Biomaterials in Glaucoma Drainage Devices

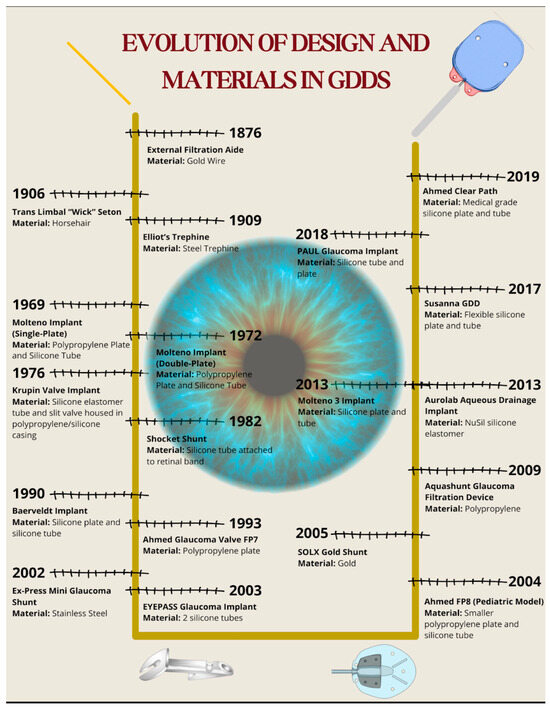

The advent of biomaterials in glaucoma surgery started in earnest with the introduction of iridectomy by Von Graefe in 1857 [5,13]. He recognized that patients who developed a bleb following an iridectomy had more favorable visual outcomes in the future, thus introducing the idea of filtering procedures. In 1867, French ophthalmologist Louis De Wecker discovered that inclusion of the iris within a corneal incision (iridencleisis) led to a filtering bleb, which formed the basis for the development of current filtering surgeries [14]. This section will discuss the evolution of design and materials used in GDDs (Figure 5).

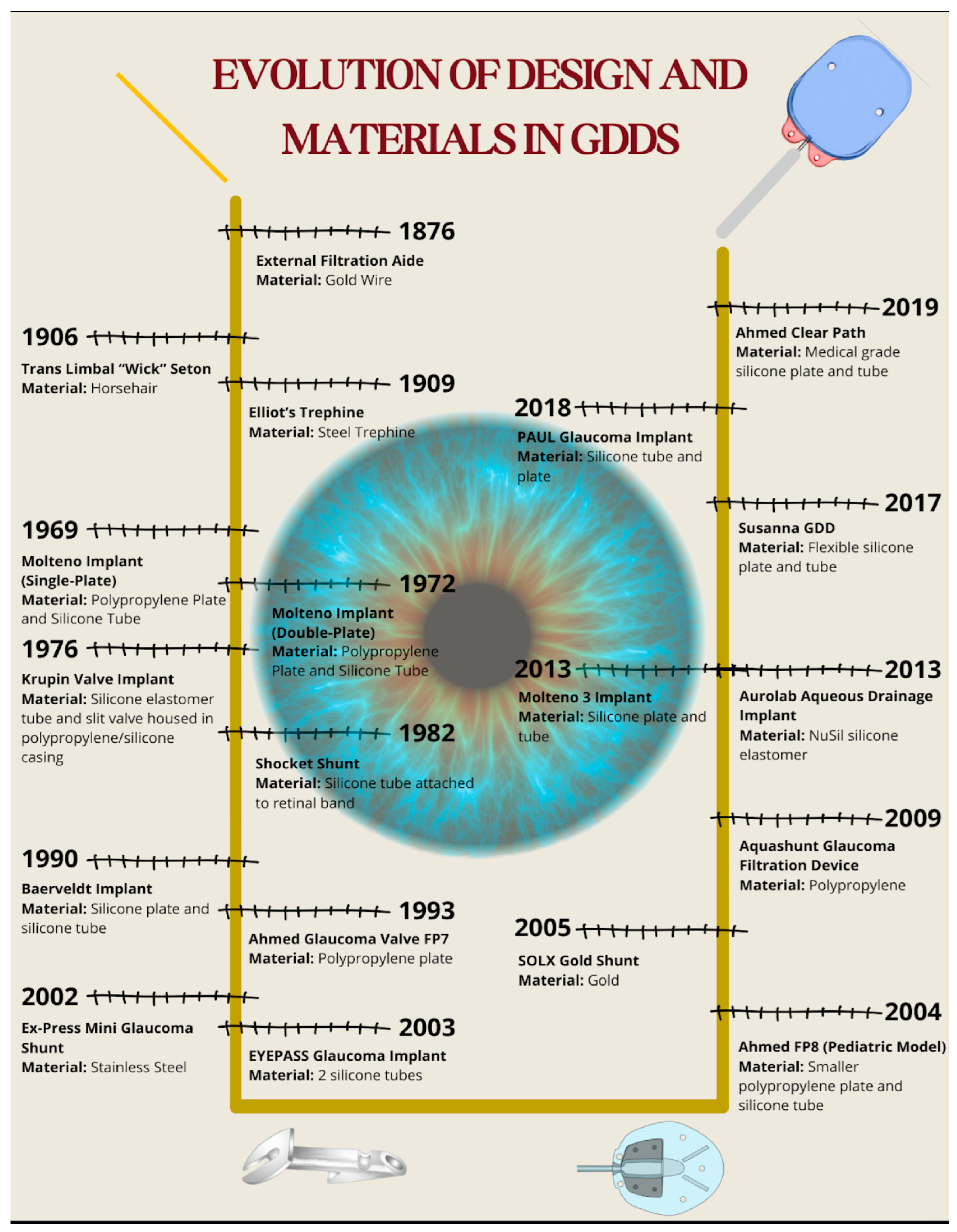

Figure 5.

Timeline illustrating the evolution of design and biomaterials in glaucoma drainage devices. The diagram presents each major device alongside its biomaterial composition and year of introduction.

3.2. Gold, Platinum, Horse Hair, and Sutures

Gold was first utilized by de Wecker in 1876 as an external filtration aid, which employed a gold wire to drain fluid outside of the sclera [14]. Although gold was recognized to be inert and malleable as early as 2500 BC by Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian physicians, de Wecker was the first to deploy it in the context of glaucoma. He found that over the long run, the gold rod was limited by incomplete drainage, inflammation, and fibrosis [14]. Interestingly, gold is utilized in a newer device called the SOLX Gold Shunt, which will be discussed later in Section 3.15.

In 1906, Rollet and Moreau introduced a trans-limbal ‘wick’ idea using horsehair passed through double corneal paracenteses to drain AH into the limbal subconjunctival space [5]. The intent was that AH would flow along the horsehair by capillary action, maintaining a patent fistula. Although innovative, the horse hair material failed to prevent fibrosis because of inflammation, irritation, redness, watering, and infections [14].

Later, silk thread was also utilized briefly around the 1910s based on the same concept as horse hair, as the material was thought to be more flexible and sterile. Although there is no quantitative data on outcomes in silk surgeries, qualitative reports claim that this method was quickly abandoned due to similar issues as horse hair [14].

These early attempts to utilize organic materials (horse hair, silk) and inert metals (gold, platinum) laid an important foundation for future GDDs. The short-term success accompanied by long-term failure due to inflammation and fibrosis demonstrated that creating a physically patent channel alone for AH drainage was often insufficient. This underscored the need for biocompatible materials and design, with the potential to resist inflammation, fibrosis, modulate healing, and promote controlled AH flow.

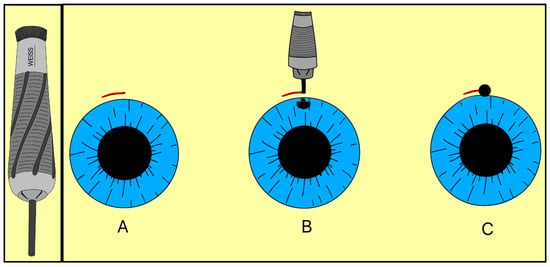

3.3. Elliot’s Trephine

In 1909, Colonel Robert Henry Elliot introduced the sclero-corneal trephining operation as an alternative to early drainage procedures [15]. Instead of implanting a foreign material, Elliot designed a handheld trephine made of steel with tubings of different lumens (Figure 6). The trephine was typically 1.5–2.0 mm in diameter, with a bevel length of approximately 1 mm, and was placed close to the limbus under a superior conjunctival flap (Figure 6).

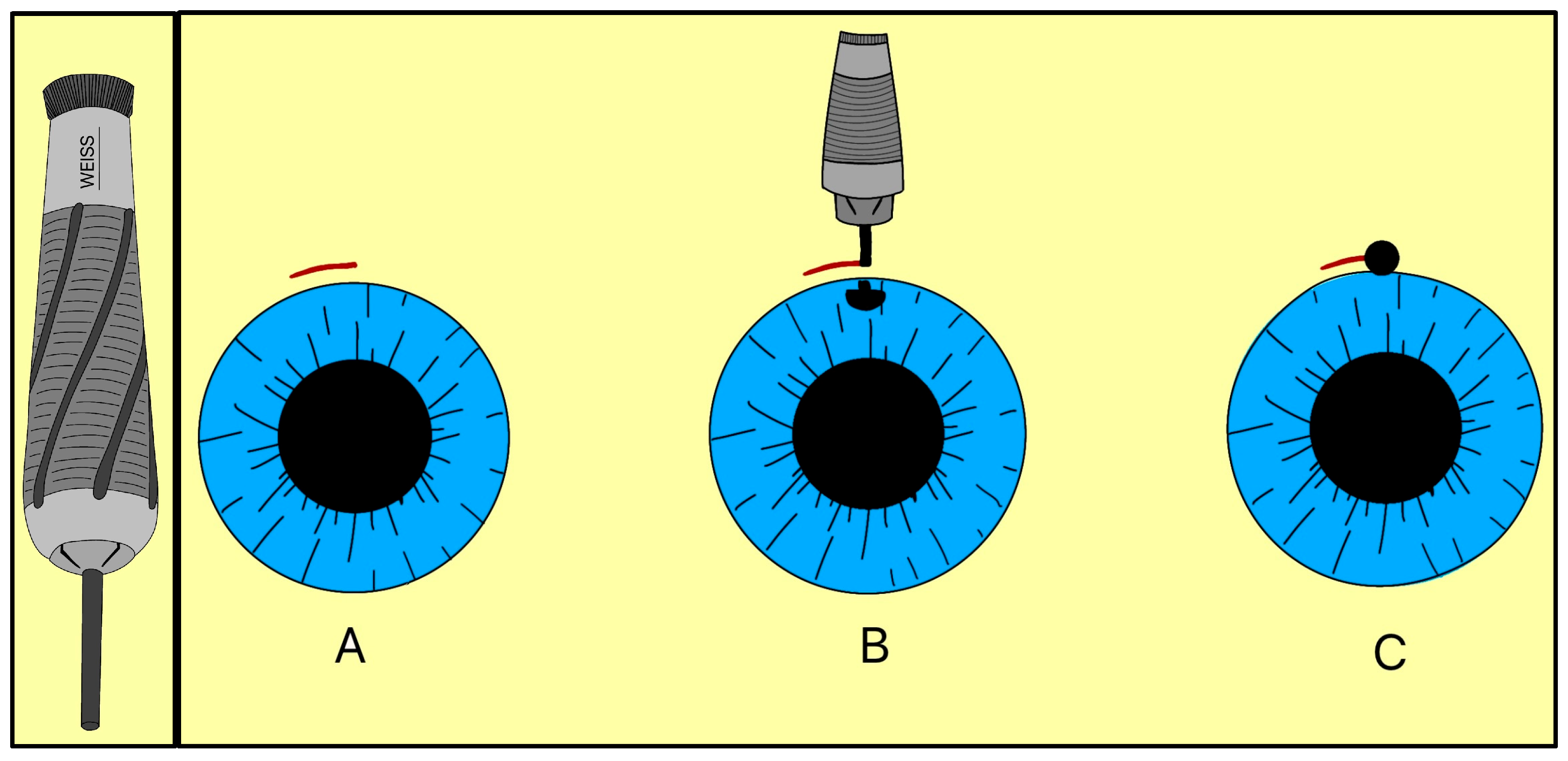

Figure 6.

Elliot’s trephine (left) and procedural steps (right). (A) Limbal conjunctival flap; (B) Creating a scleral hole; (C) Completed sclero-corneal trephining operation. Adapted from [15].

By removing part or all of the corneoscleral disc, the trephine created a direct channel for AH to exit under the subconjunctival space, forming a filtering bleb. The fistula depended on the size of the trephine selected, and Elliot sometimes combined the operation with a peripheral iridectomy when iris prolapse risk was high. Clinically, this approach represented a major conceptual advance, as it eliminated reliance on organic implants and relied on instrument-guided fistulas to promote filtration, a principle that ultimately led to the modern trabeculectomy and GDDs.

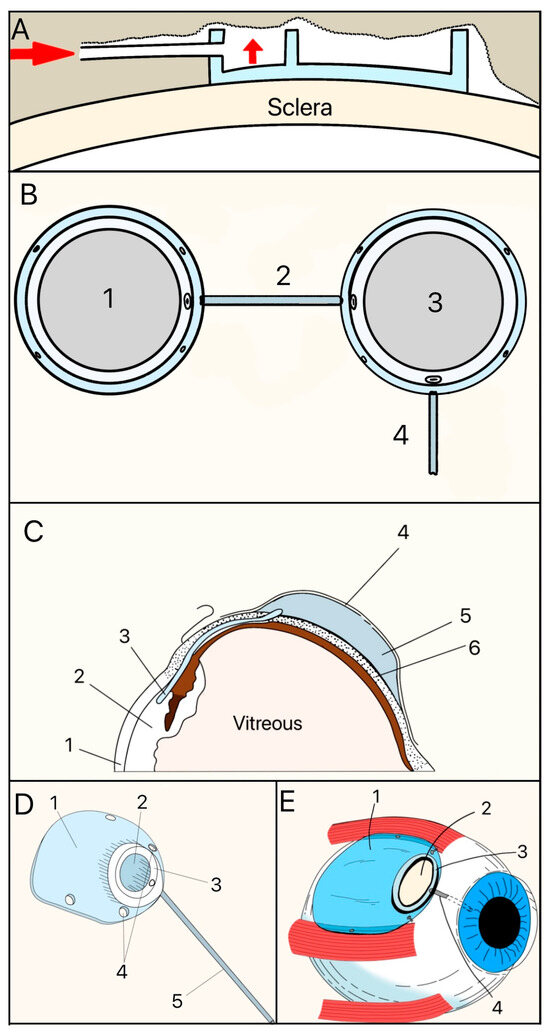

3.4. Molteno Implant

The Molteno implant, introduced in the early 1970s by Dr. Anthony B. Molteno in New Zealand, was the first valveless GDD made of a medical-grade silicone drainage tube and a polypropylene episcleral plate that measured approximately 13 mm in diameter with a 12 mm radius of curvature (Figure 7A). Its design innovations, particularly in plate geometry and material selection, set the stage for subsequent GDD improvements. The original Molteno implant had a concave episcleral plate designed to conform to the scleral curvature, with a circumferential ridge to define the bleb [16]. A later iteration of the Molteno included two plates, each having a ridge that measured 1.3 mm in height with a 45° outer slope angle and suture holes 0.6 mm in diameter (Figure 7B) [17]. In the next iteration of the Molteno implant, the main change was a secondary pressure ridge on the plate to create a pressure-sensitive spillover chamber onto the plate (Figure 7C) [18]. The pressure ridge was aimed at reducing early hypotony (low IOP). By 2010, the Molteno implant had evolved into a larger single-plate design with an inner ridge defining a primary drainage region and a secondary drainage region (Figure 7D). The outer ridge size was reduced to facilitate easier implantation while retaining suture holes for secure attachment. The plate continued to be made of medical-grade polypropylene, and was precision-molded to achieve the concave curvature (radius ~12 mm), ridge geometry (0.95–1.15 mm height), and suture holes (~0.6 mm). The plate thickness is 0.4 mm, with surface areas of 185 mm2 (small-plate) or 245 mm2 (large-plate), and maximum lengths and widths range from 15.4–17.4 mm and 13.6–15 mm, respectively. The medical-grade silicone drainage tube has a length of 17–19 mm with an inner diameter (ID) and outer diameter (OD) of 0.34 mm and 0.64 mm, respectively, as well as flanged ends for secure attachment (Figure 7E).

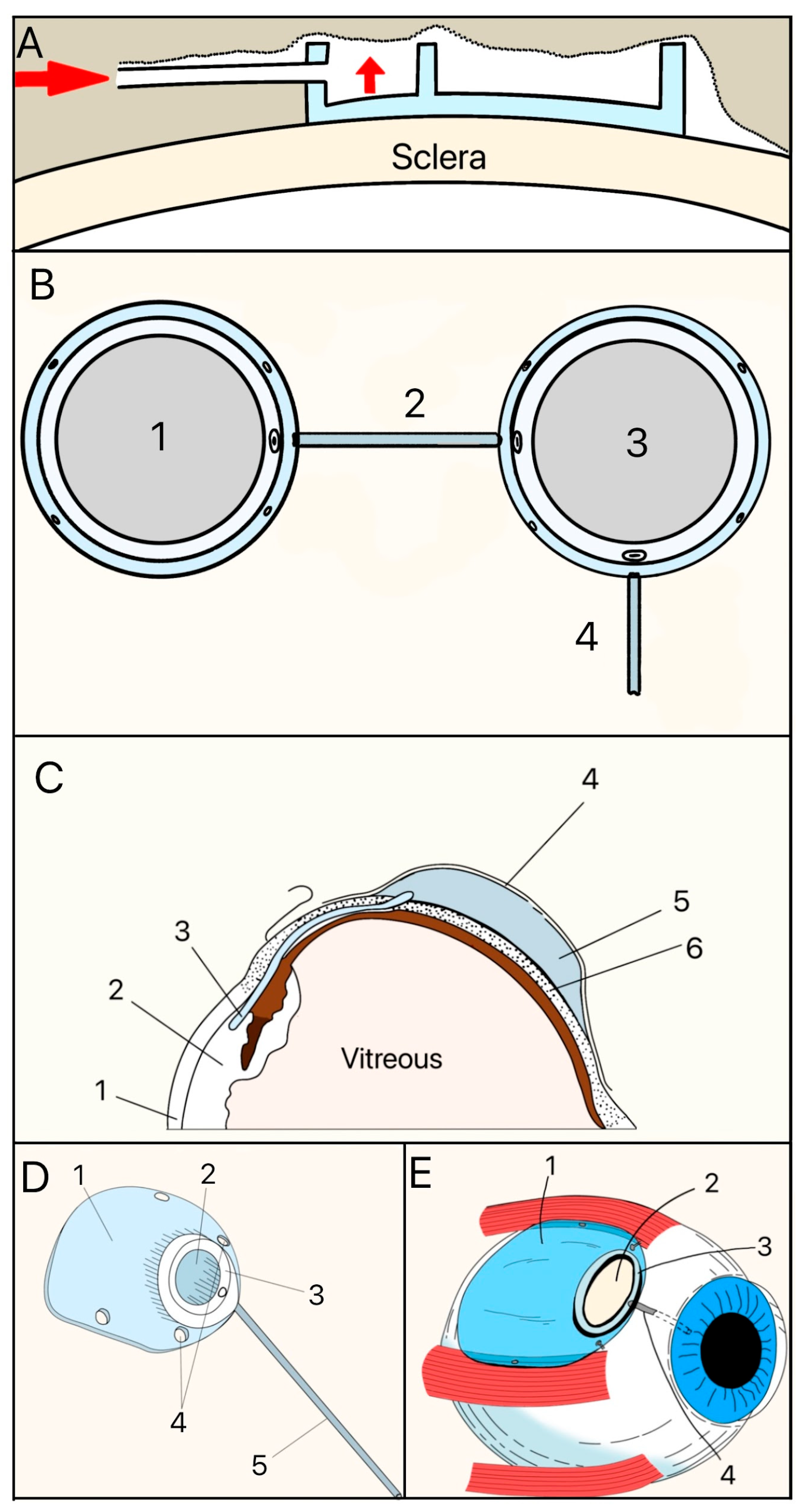

Figure 7.

(A) Cross-section of the original Molteno implant placed on the sclera. The red arrow shows where aqueous humor enters. (B) First version of the Double-Plate Molteno implant. 1 = Second plate, 2 = Connecting tube, 3 = First plate, 4 = Drainage tube; (C) Cross-sectional view of an inserted Molteno implant. 1 = Cornea, 2 = Anterior Chamber, 3 = Tube, 4 = Conjunctiva, 5 = Molteno implant, 6 = Sclera. (D) 2010 version of the Molteno implant. 1 = Plate, 2 = Primary drainage area, 3 = Outer ridge of the primary drainage area, 4 = Suture holes, 5 = Drainage tube. (E) Sketch of the Molteno implant on an eye. 1 = Plate, 2 = Primary drainage area, 3 = Outer ridge of the primary drainage area, 4 = Drainage tube. Adapted from [17,18,19].

The Molteno implant has shown satisfactory long-term IOP reduction in refractory and complex glaucoma [20]. The common adverse effects include hypotony, flat AC, choroidal detachment, encapsulated bleb, tube/plate exposure, corneal decompensation, phthisis bulbi, and endophthalmitis [20].

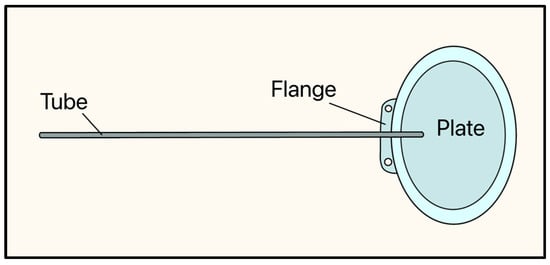

3.5. Krupin Eye Valve

In 1976, Theodore Krupin developed the Krupin eye valve, which marked a significant moment in the evolution of GDD design as it had a unidirectional, pressure-sensitive valve (Figure 8) [21].

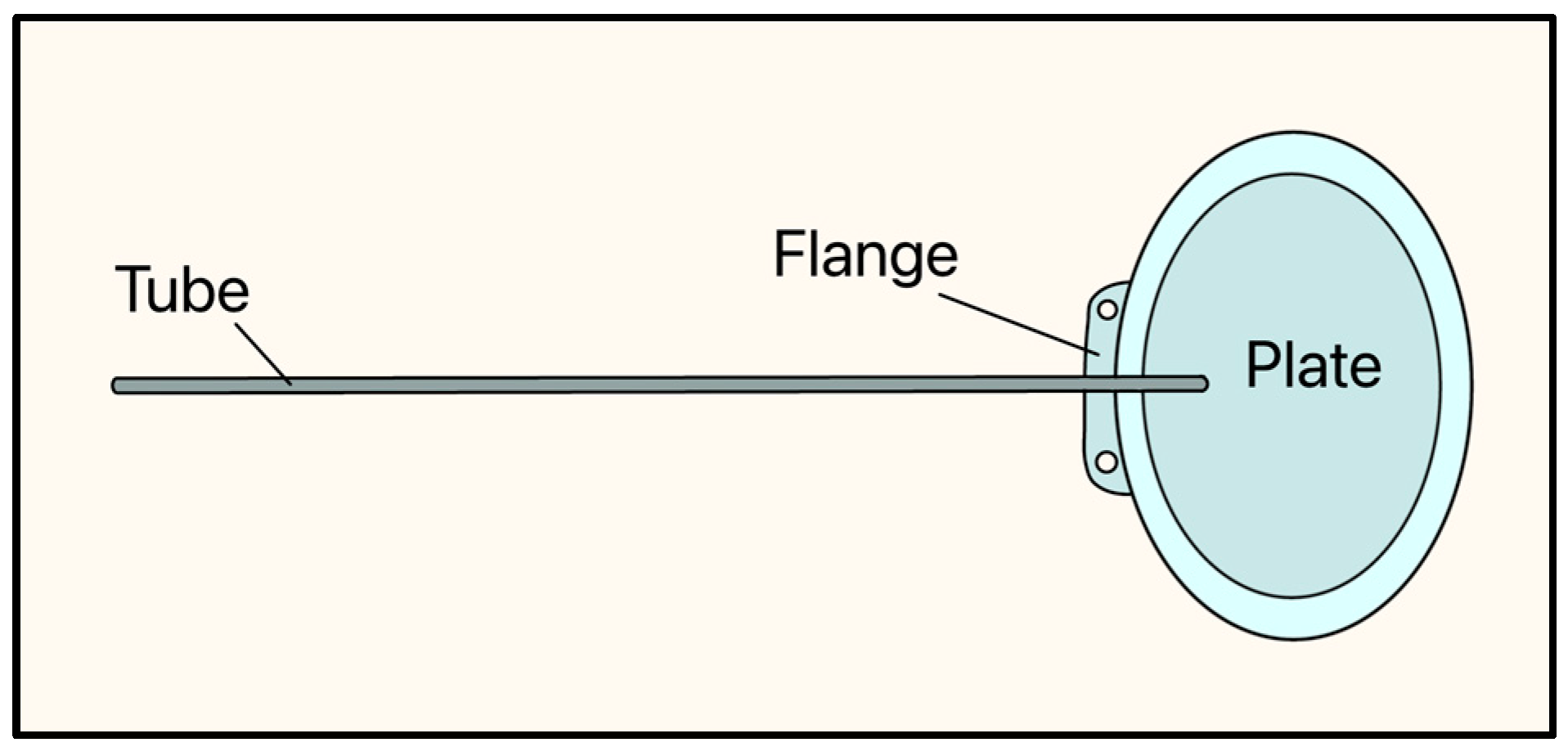

Figure 8.

Krupin valve showing the tube, flange, and plate. Adapted from [21].

The implant consists of a curved oval silicone plate, measuring 18 mm × 13 mm, and the tube is made of a silicone elastomer (OD: 0.58 mm, ID: 0.38 mm) and has a slit valve at its distal end, where it rests on the plate. The slit-valve is calibrated to open at a pressure between 10–12 mmHg and close at a pressure between 8–10 mmHg [21,22].

A 1996 study by Mastropasqua et al. [23] at the University of Chieti-Pescara (Italy) examined the long-term results of Krupin Eye Valve surgery in 28 eyes. Postoperative success (IOP less than 21 mmHg) was obtained in 10 (36%) eyes [23]. Early complications included shallow or flat AC (54%), hypotony (57%), elevated IOP (25%), serous choroidal effusion (25%), fibrinous uveitis (18%), and choroidal hemorrhage (7%). Late complications included bleb failure (43%), cataract formation (7%), bullous keratopathy (7%), conjunctival erosion (7%), phthisis bulbi (7%), and blockage of the intracameral portion of the tube by fibrovascular tissue (18%) [23].

A study by Ayyala et al. in 2000 [24] compared the inflammatory response of Krupin and Molteno implants in rabbit eyes. They found that the polypropylene material (Molteno) was associated with more inflammation, both in clinical observations and histological grading, than the silicone material (Krupin) [24]. The Krupin Eye Valve was not widely accepted after the introduction of the Baerveldt and Ahmed implants, and was finally discontinued in 2006 following a recall notice by regulators in Canada.

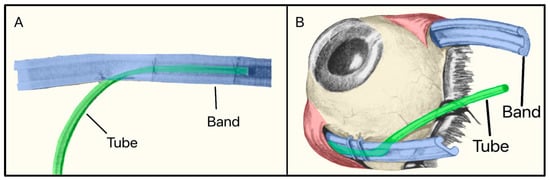

3.6. Schocket Shunt

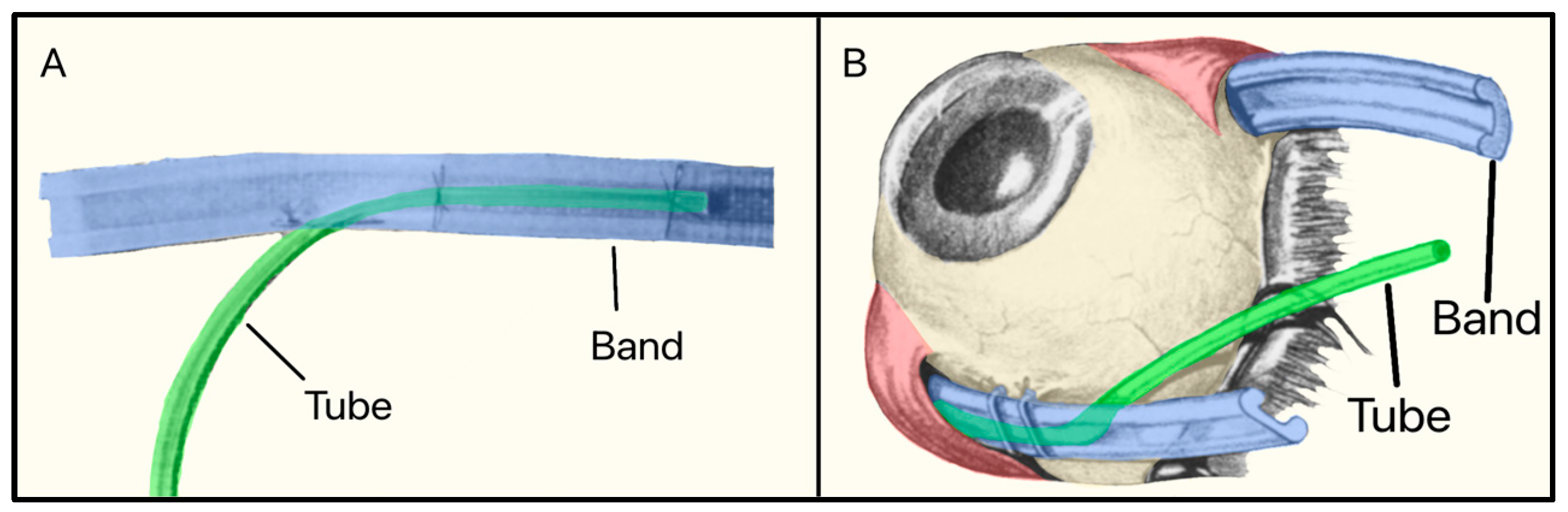

In 1982, Stanley Schocket, a vitreoretinal surgeon from Baltimore, Maryland, developed a non-valved non-plate GDD called the Shocket Shunt [25]. It consisted of a silicone tube that drained AH to an equatorial encircling silicone band (used for treating retinal detachment) placed under four ocular rectus muscles (Figure 9). The band was inverted with its groove facing the sclera, as draining AH to the retro-orbital area was preferable to the subconjunctival space [25].

Figure 9.

(A) The Schocket shunt showing the tube and the silicone band; (B) The Schocket shunt placed on the eye. Adapted from [25].

A 1992 multicenter, controlled, randomized trial by Wilson et al. compared the efficacy of the Schocket shunt versus the double-plate Molteno and found that the Molteno had better outcomes, and the Schocket shunt was eventually discontinued [26].

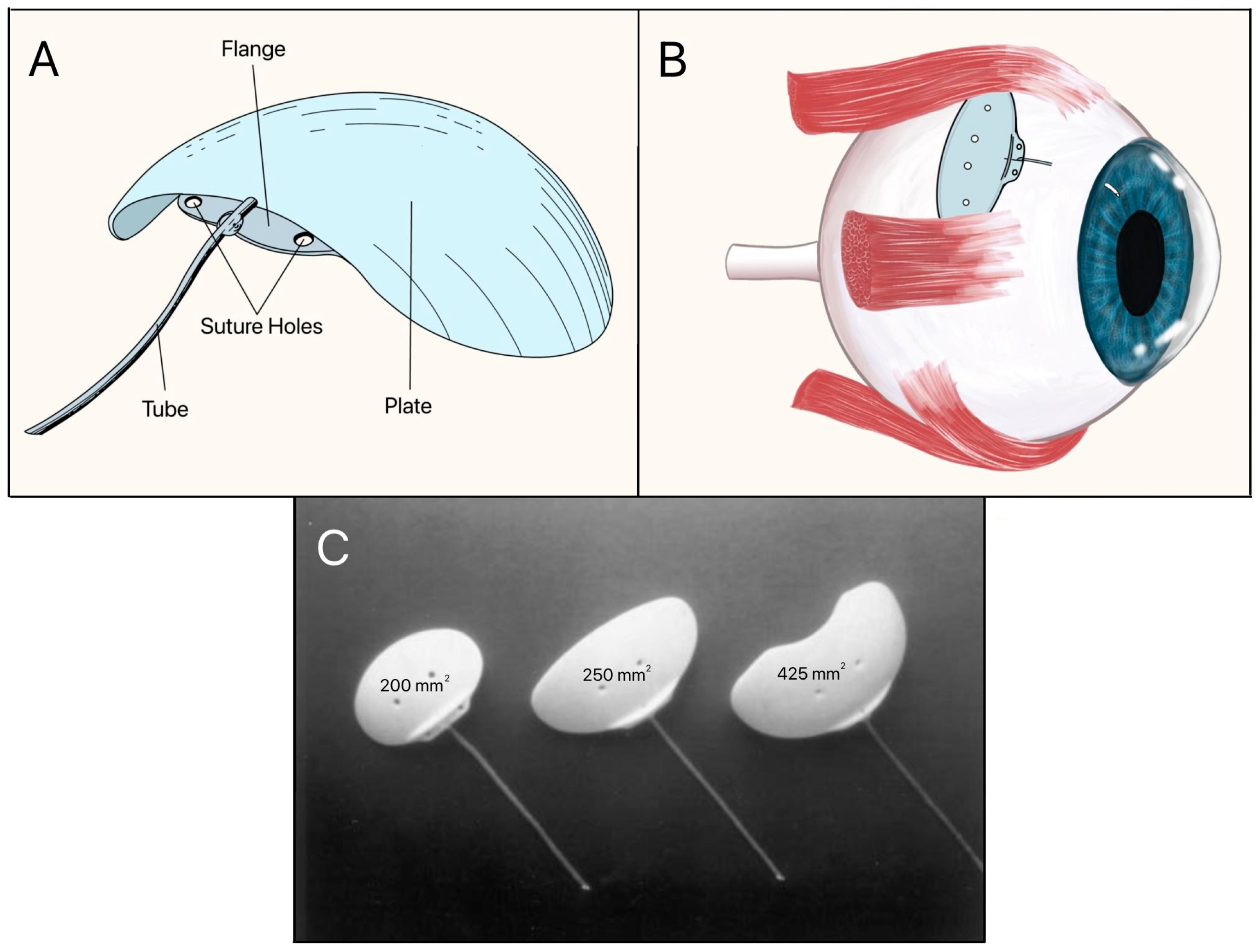

3.7. Baerveldt Implant

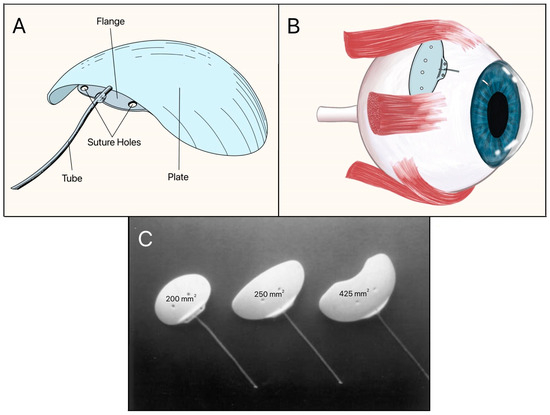

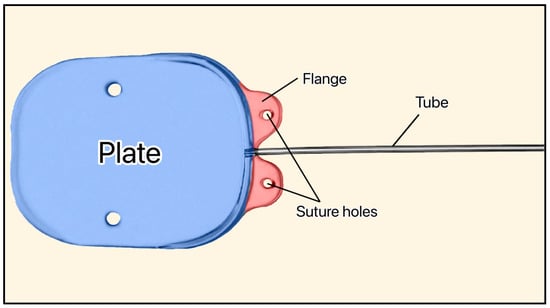

The Baerveldt implant is a non-valved device that was introduced in the late 1980s by Dr. George Baerveldt. Its early patents were assigned to Iovision, Inc., later manufactured by Abbott Medical Optics, and currently marketed by Johnson & Johnson Vision (Irvine, CA, USA). It consists of a large, flexible silicone endplate with a surface area of 350 mm2, a thickness of 0.5–2.0 mm, and a radius of curvature of 12–14 mm, impregnated with barium, thus making it radiopaque, and a silicone tube with an ID of 0.30 mm and OD of 0.64 mm (Figure 10A). It is designed for placement under the superior and lateral rectus muscles in the superotemporal quadrant (Figure 10B) [27]. Subsequent generations of the Baerveldt implant consisted of endplate sizes of 200 mm2, 250 mm2, 425 mm2, and 500 mm2 (Figure 10C). The 250 mm2 and 350 mm2 models became the most widely used, with the 350 mm2 model remaining the standard for maximal IOP reduction, while the 250 mm2 model was used in patients with smaller orbits [28].

Figure 10.

(A) Baerveldt implant showing the tube, suture holes, flange, and plate; (B) Baerveldt implant on the eye; (C) Three sizes of the Baerveldt implant with surface areas of 200 mm2, 250 mm2, and 425 mm2 (left to right). Adapted from [27,28].

The most frequently reported adverse effects include hypotony, tube and endplate exposure, corneal edema or decompensation, shallow or flat AC, choroidal effusion, choroidal hemorrhage, diplopia (double vision), device explantation, endophthalmitis, and retinal detachment [29].

3.8. Ahmed Glaucoma Valve

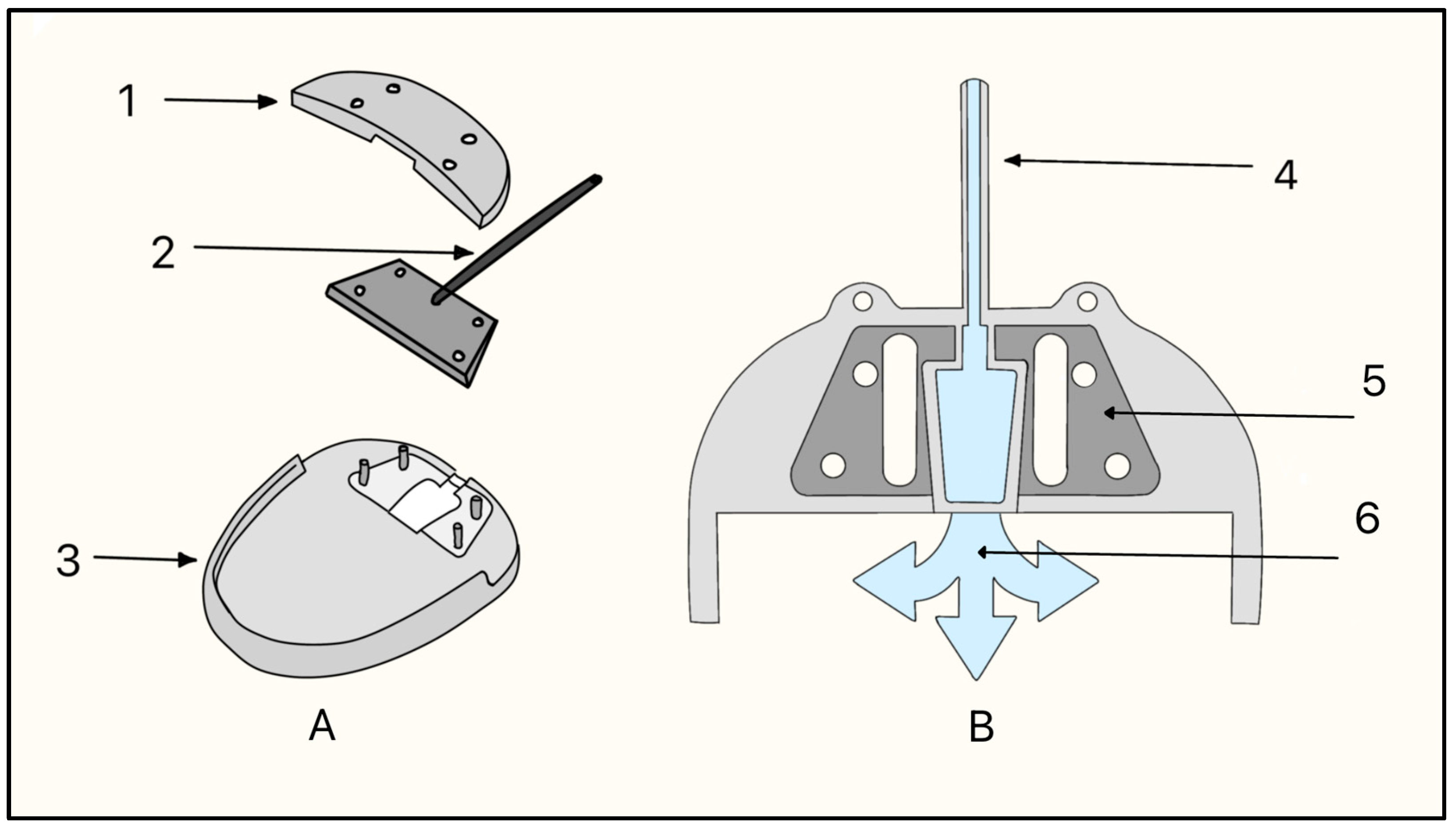

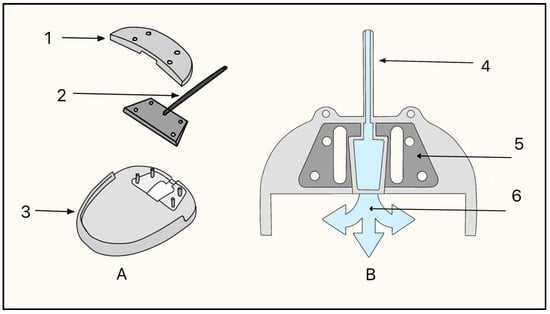

The Ahmed glaucoma valve (AGV) by New World Medical (Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA) was designed by Mateen Ahmed, PhD, in 1993. Dr. Ahmed’s concept was to create an innovation that integrates the flow-restricted valve mechanism (Figure 11). The design was aimed at controlling the flow of AH and thus mitigating the risk of early postoperative hypotony [30].

Figure 11.

Ahmed glaucoma valve components. (A) 1 = Valve system, 2 = Silicone drainage tube, 3 = Silicone Plate; (B) Ahmed Glaucoma Valve flow mechanism, 4 = Silicone drainage tube, 5 = Valve system, 6 = Fluid flow. Adapted from [31].

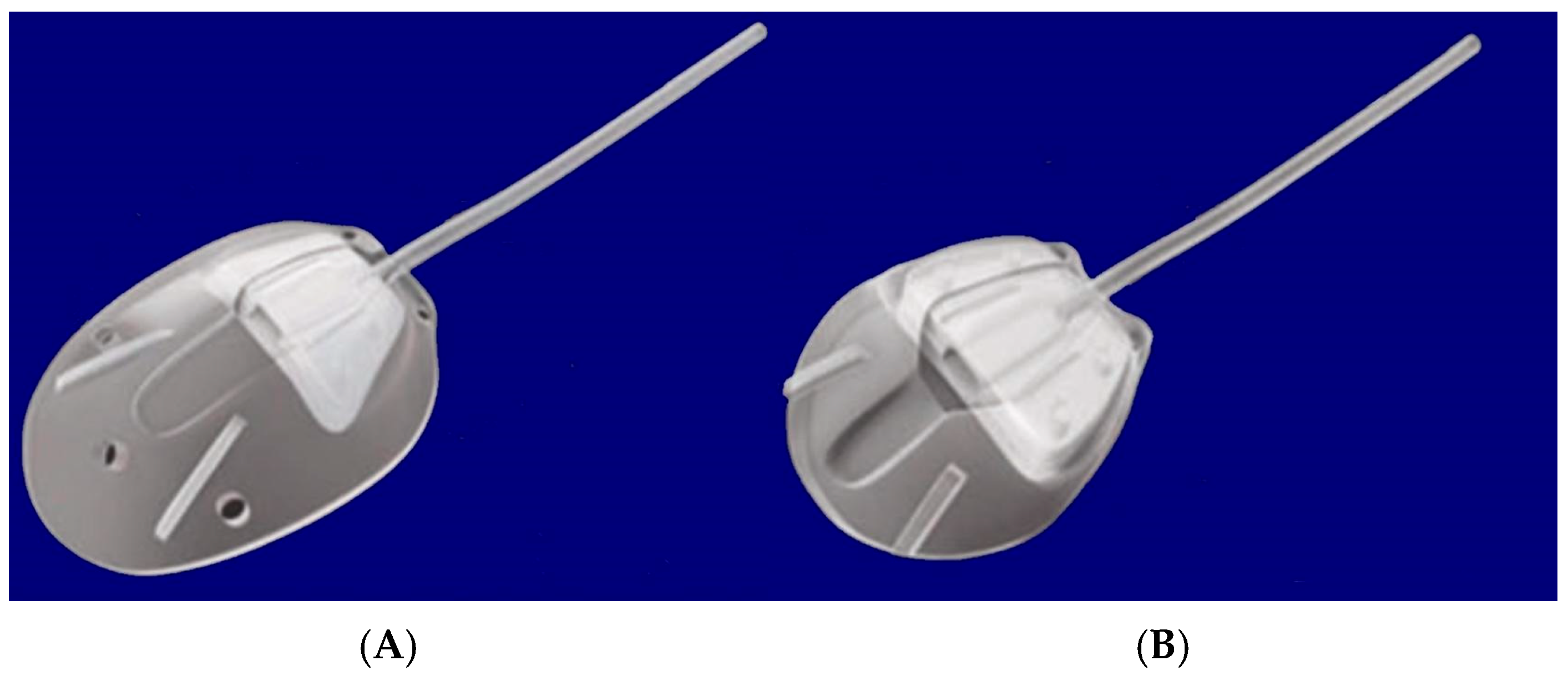

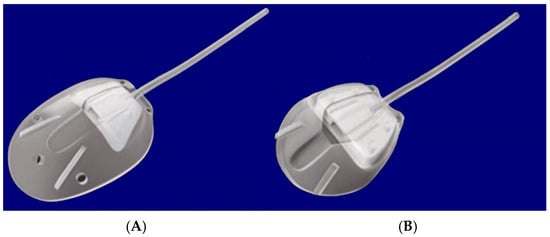

The original valve design was based on a venturi-style, unidirectional flow system. The valve was made of two thin, flexible, silicone membranes that responded to pressure differentials to open at 8 mmHg and close at 12–13 mmHg (Figure 11). Two medical-grade silicone leaflets (8 × 7 mm) mounted in a polypropylene housing form a tapered, venturi-style chamber. The silicone drainage tube (25.4 mm × 0.305/0.635 mm ID/OD) feeds the chamber, and the flexible silicone plate (FP7: 184 mm2; FP8: 102 mm2) provides the diffusion surface for AH outflow (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Silicone models of the Ahmed glaucoma valve. (A) FP7; (B) FP8. Adapted from [31].

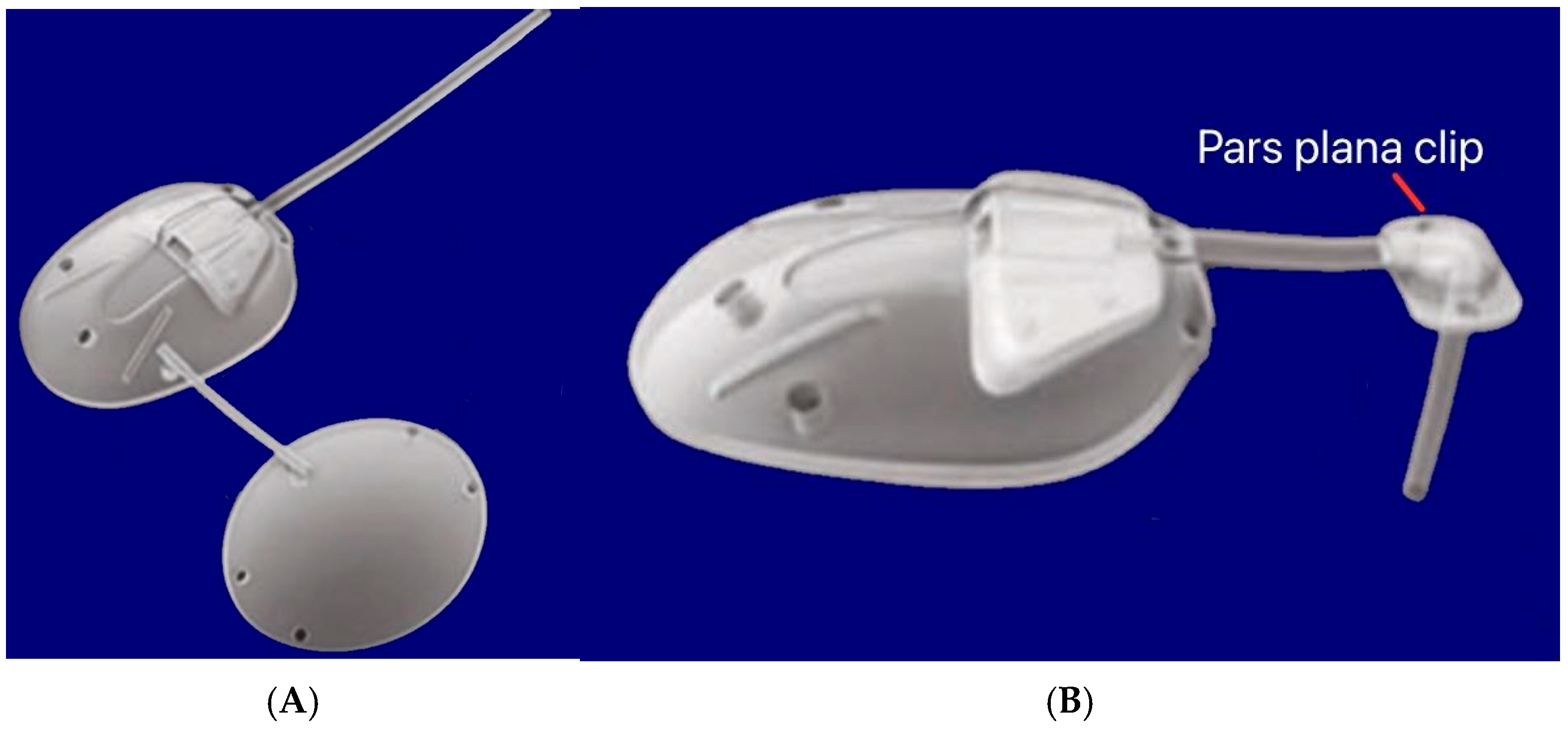

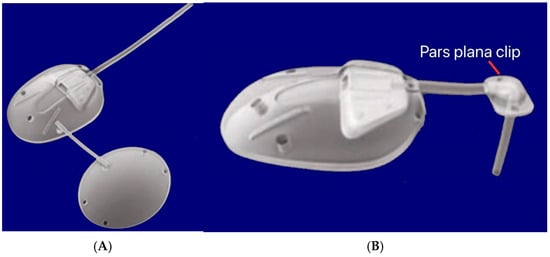

The flexibility of the valve components was essential for the nonlinear, pressure-dependent resistance. Computational and experimental analyses showed that the valve maintained a pressure drop between 7–12 mmHg across physiological flow rates. Polypropylene-based models are also available as S2 (184 mm2) and S3 (96 mm2). Other variants include a pars plana clip (PC7/PC8) that attaches to the tube to redirect it posteriorly through pars plana entry at 90° without kinking, and is used for posterior-segment placement in vitrectomized eyes (Figure 13). A flexible bi-plate configuration (FX1) adds a second plate in a separate quadrant to increase the total filtration surface to 364 mm2. The M4 model uses a porous high-density polyethylene (MEDPOR®) plate to encourage tissue integration [31].

Figure 13.

(A) Silicone double-plate model of the Ahmed FX1 (364 mm2); (B) Silicone model of the Ahmed PC7 (184 mm2) showing the pars plana clip. Adapted from [31].

Two new valveless AGV models (ClearPath) were introduced in 2019, available as 250 mm2 and 350 mm2 sizes [32]. The model 250 is designed for single-quadrant implantation between the rectus muscles to eliminate muscle isolation steps, while the model 350 features a winged plate with the winged portions placed under the rectus muscles for improved stability [32]. Both models are made from a barium-impregnated, medical-grade silicone plate (0.86 mm thick) and include a pre-inserted 23-gauge needle and optional 4-0 polypropylene ripcord [32]. The summary of the different types of AGVs is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptions of various types of Ahmed glaucoma valves.

The outcomes of the AGV have demonstrated effective long-term IOP reduction in refractory and complex glaucoma with a decrease in IOP and number of glaucoma medications sustained for up to 7–15 years post-implantation [33]. Success rates are high in the short term, but decline over time, and the complications include tube/plate exposure, hypertensive phase, hypotony, corneal decompensation, endophthalmitis, and vision loss [33].

3.9. Ex-PRESS Mini Glaucoma Shunt

Originally developed by Optonol Ltd. (Neve Ilan, Israel), the Ex-PRESS Mini glaucoma shunt was approved in 2003 as a substantial equivalent to existing devices, such as the AGV and the Baerveldt implant [34]. Currently, in the United States, the Ex-PRESS Mini glaucoma shunt is manufactured and distributed by Alcon Inc. (Fort Worth, TX, USA).

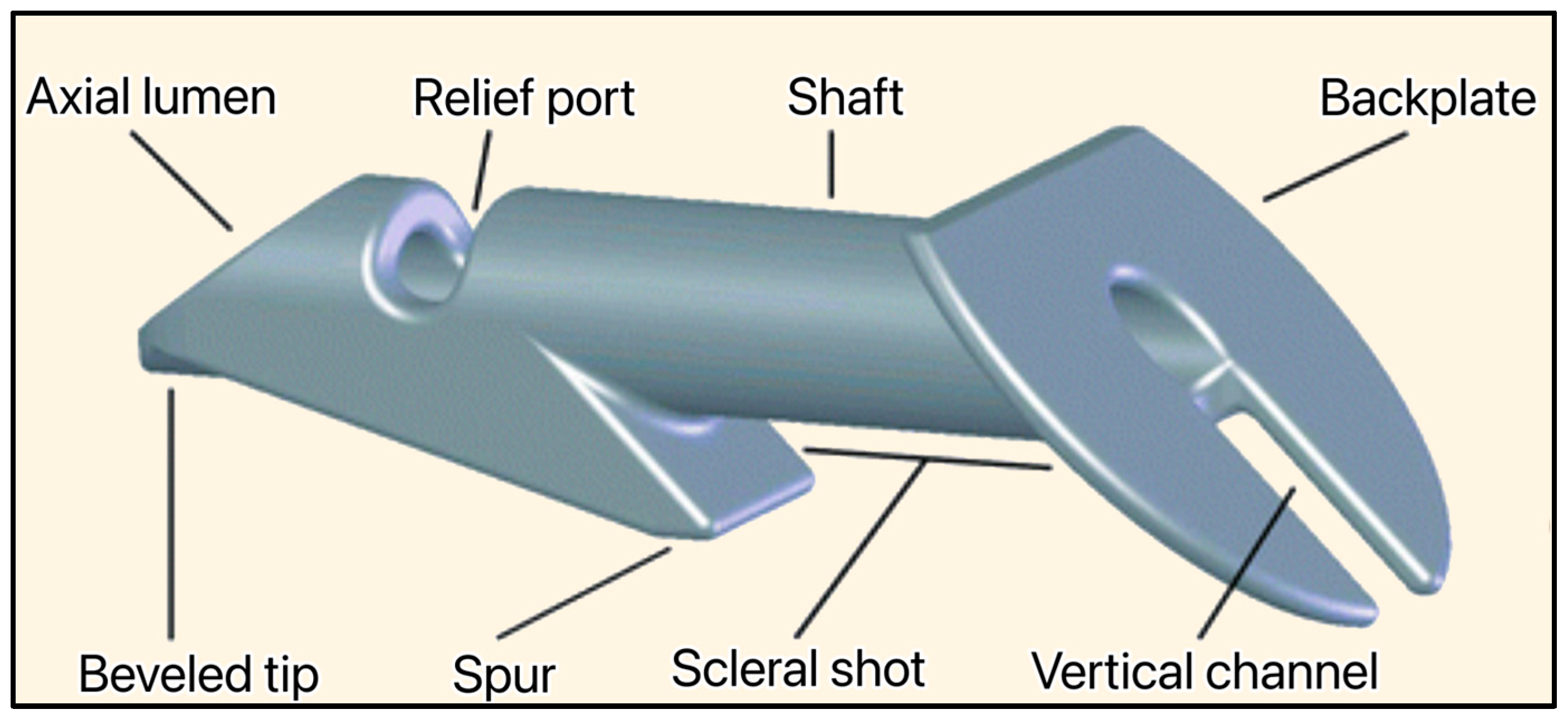

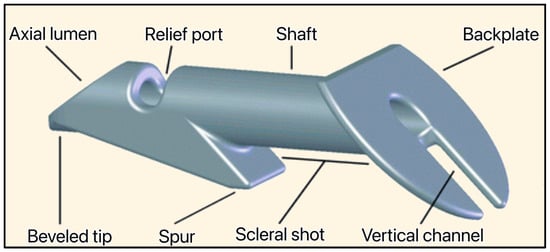

The implant is non-valved, made of medical-grade stainless steel, and MRI-compatible. With a total length of 2.44 mm, its shaft has an outer diameter of 400 μm and an inner lumen of 50 μm. The device is approved as a stand-alone treatment of glaucoma, and is inserted at the limbus (junction between the cornea and sclera) under a conjunctival flap (Figure 14) [35]. This initial approach resulted in severe complications such as persistent hypotony, inflammation, conjunctival erosion, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, endophthalmitis, and fibrosis. Later, the surgery was modified to cover the device with a partial-thickness scleral flap, and the complications decreased on par with the complications of a traditional trabeculectomy [35,36].

Figure 14.

The Ex-PRESS Mini glaucoma shunt showing the beveled tip, axial lumen, relief port, spur, shaft, scleral shot, backplate, and vertical channel. Courtesy of Alcon [34].

3.10. EyePass

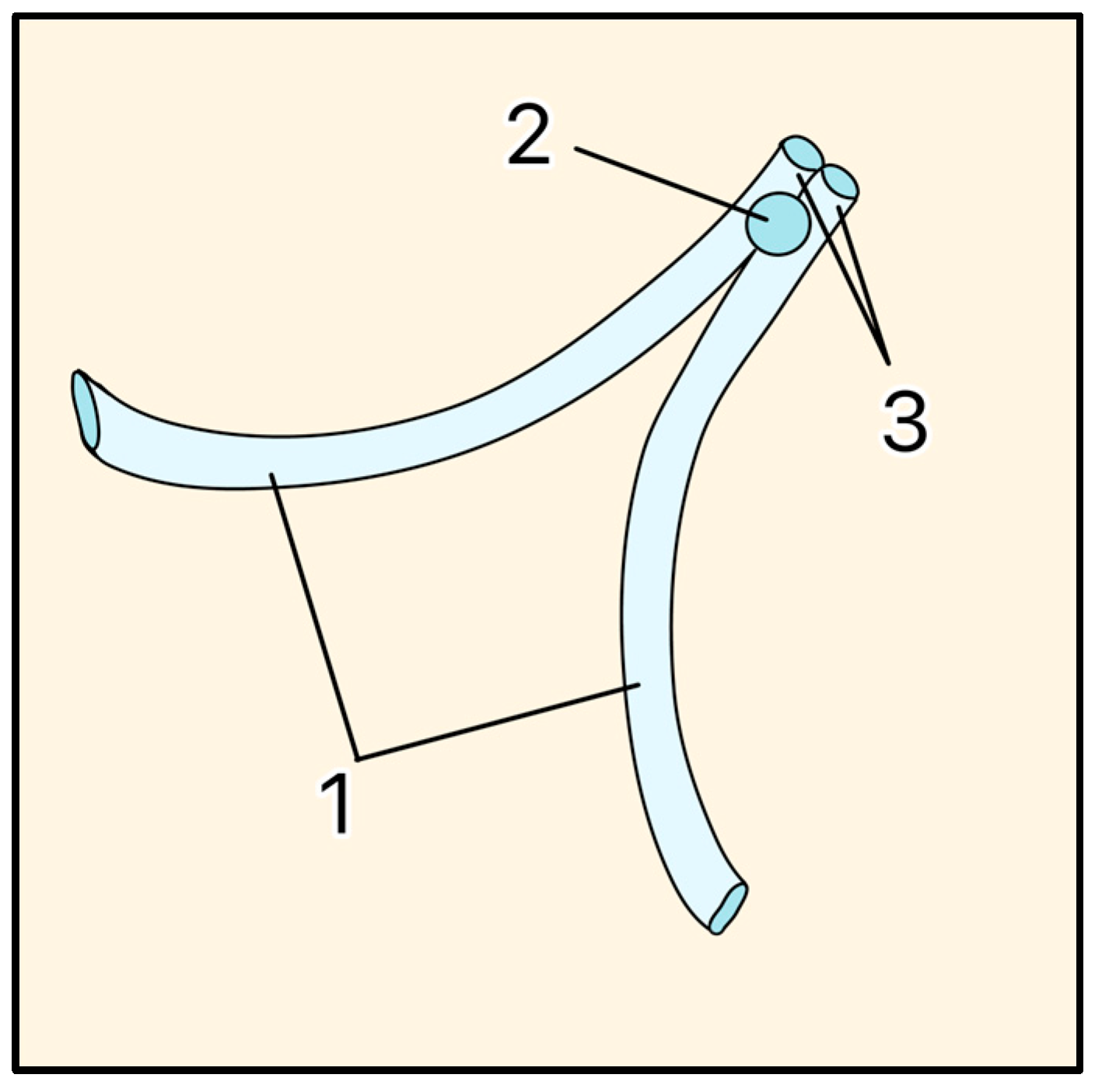

The EyePass implant was developed by Reay H. Brown, MD, and Mary Lynch, MD, at Emory Eye Center (Atlanta, GA, USA) and fabricated by GMP Companies Inc. (Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA) in 1999. However, the device was discontinued during Phase 3 clinical trials due to unsuccessful results. The technology and concepts were later acquired by Glaukos Corp. (Laguna Hills, CA, USA) and approved for commercial use in Europe. It was the first TM bypass device, indicated for mild-to-moderate POAG.

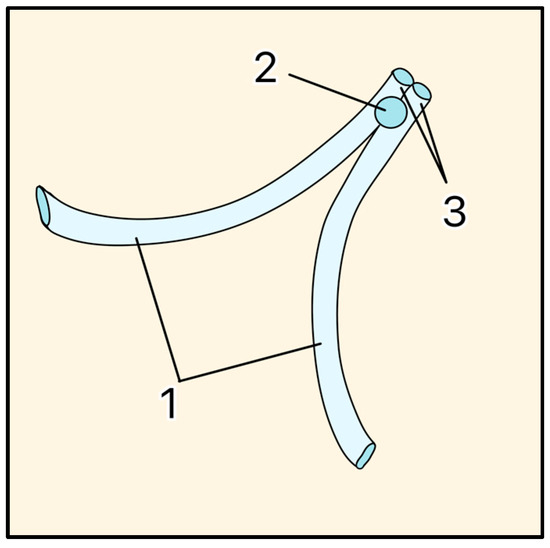

The EyePass featured a silastic shunt with a main collecting stem and two protruding 6-mm long drainage tubes forming a “Y” shape at the junction of the AC and the SC lumen (Figure 15) [37]. The OD and ID dimensions of the tube stem were 250 μm and 125 μm, respectively. The AH is shunted from the AC via the two lumens of the collecting stem and delivered into the SC in opposite directions [37].

Figure 15.

EyePass Device. 1 = Drainage tubes, 2 = Anchor, 3 = Collecting stem. Adapted from [37].

A 2017 study showed a 30.3% reduction in mean IOP 5 years postoperatively in 14 patients [38]. The most common complications were transient hypotony (28.6%), corneal decompensation (21.4%), and device malpositioning (14.3%) [38].

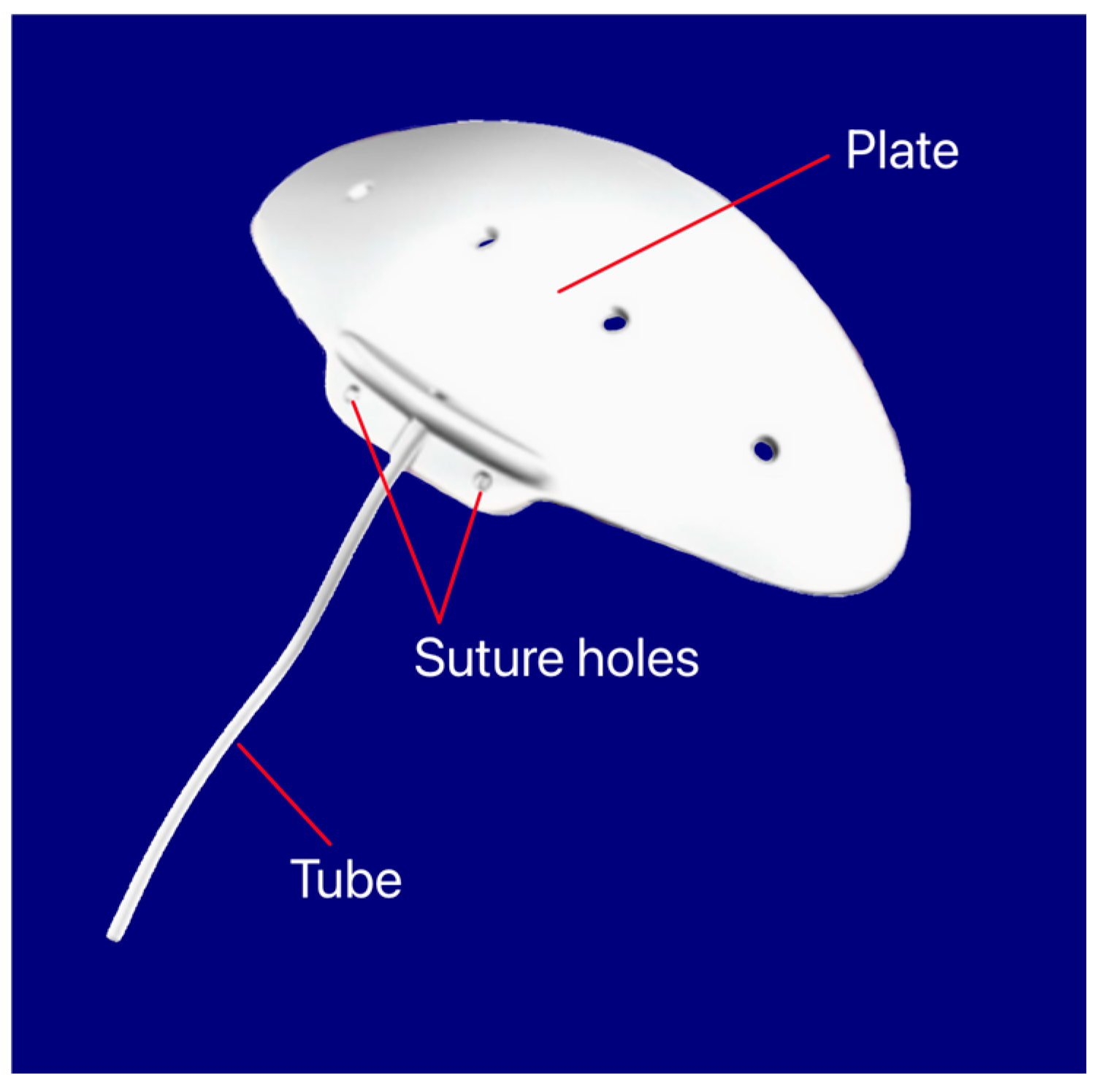

3.11. Aurolab Aqueous Drainage Implant

The Aurolab Aqueous Drainage Implant (AADI) was invented by Aurolab, a manufacturing division of Aravind Eye Care System in Madurai, India. In partnership with Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (Miami, FL, USA), the AADI was developed for commercial use in India and surrounding countries as a cheaper (~$50) but structurally similar alternative to the Baerveldt glaucoma implant 350 [39]. It was initially released in June of 2013, and clinical studies were conducted in Russia and Egypt to review and compare efficacy, safety, and postoperative complications. Aurolab has pursued regulatory approval for the commercial use of the AADI in Europe through the CE Mark; however, it has not submitted the necessary applications and extensive clinical data to the FDA for review in the U.S. [39].

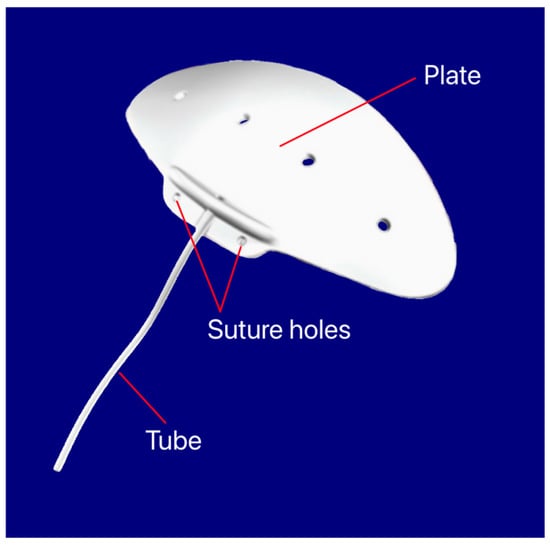

The device features a silicone elastomer non-valved shunt that drains AH from the AC into the subconjunctival space. The AADI has an end plate with a surface area of 350 mm2 with two fixation holes to help secure the implant to the sclera (Figure 16) [39].

Figure 16.

Aurolab Aqueous Drainage Implant showing the tube, suture holes, and plate. Courtesy of [39].

A 2022 review showed that the AADI achieved a significant reduction in both IOP (55–75%) and the number of anti-glaucoma medications (65–85%), with no significant change in visual acuity post-surgery [40].

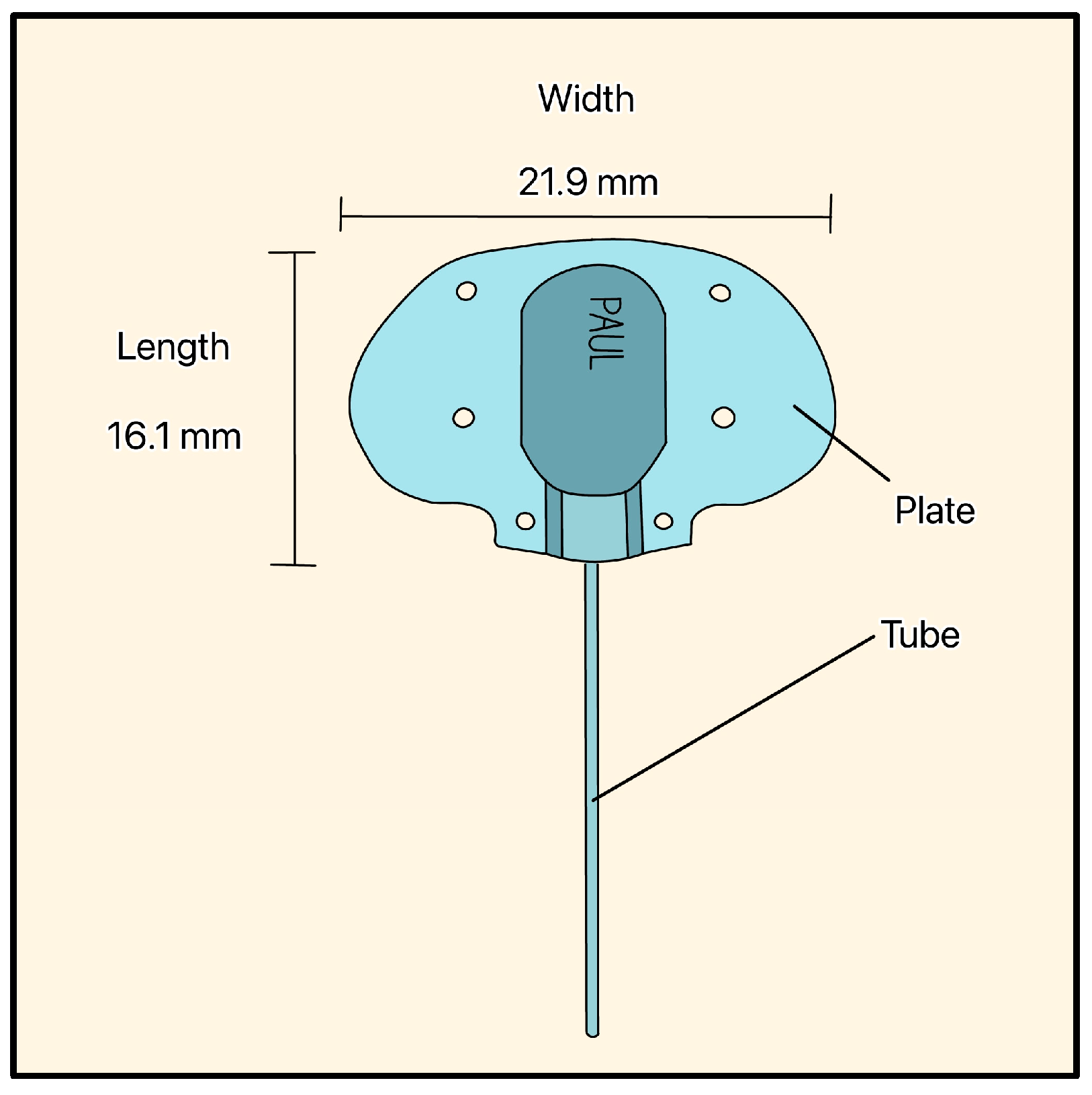

3.12. PAUL Glaucoma Implant

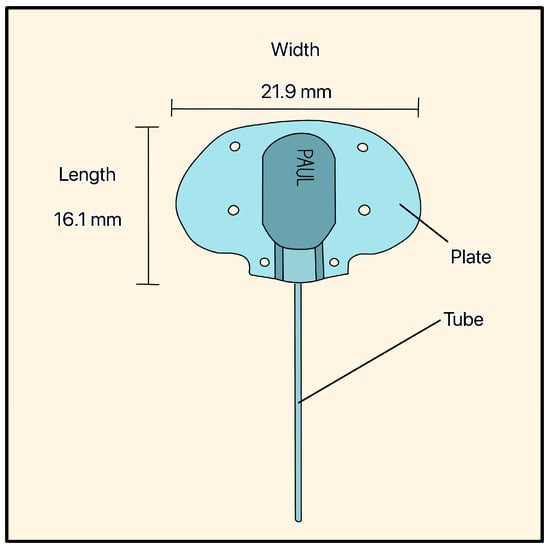

The PAUL Glaucoma Implant (PGI) is a valveless device developed by Paul Harasymowycz and colleagues at the University of Montreal and manufactured by Advanced Ophthalmic Innovations (Singapore). It is made of silicone and features a large endplate (21.9 mm width, 16.1 mm length, 342 mm2 surface area) and a tube with an ID/OD of 0.127 mm/0.467 mm, respectively (Figure 17) [41].

Figure 17.

PAUL Glaucoma Implant showing the tube, the plate, and the plate’s dimensions. Adapted from [41].

The PGI demonstrated mean IOP reductions between 14.8 mmHg and 19.1 mmHg across various studies in refractory glaucoma, and the common complications were early postoperative hypotony (2–35.4%), shallow AC (14.9–22.2%), choroidal detachment (0–13.3%), and tube/plate exposure or erosion (4.1–6.7%) [42].

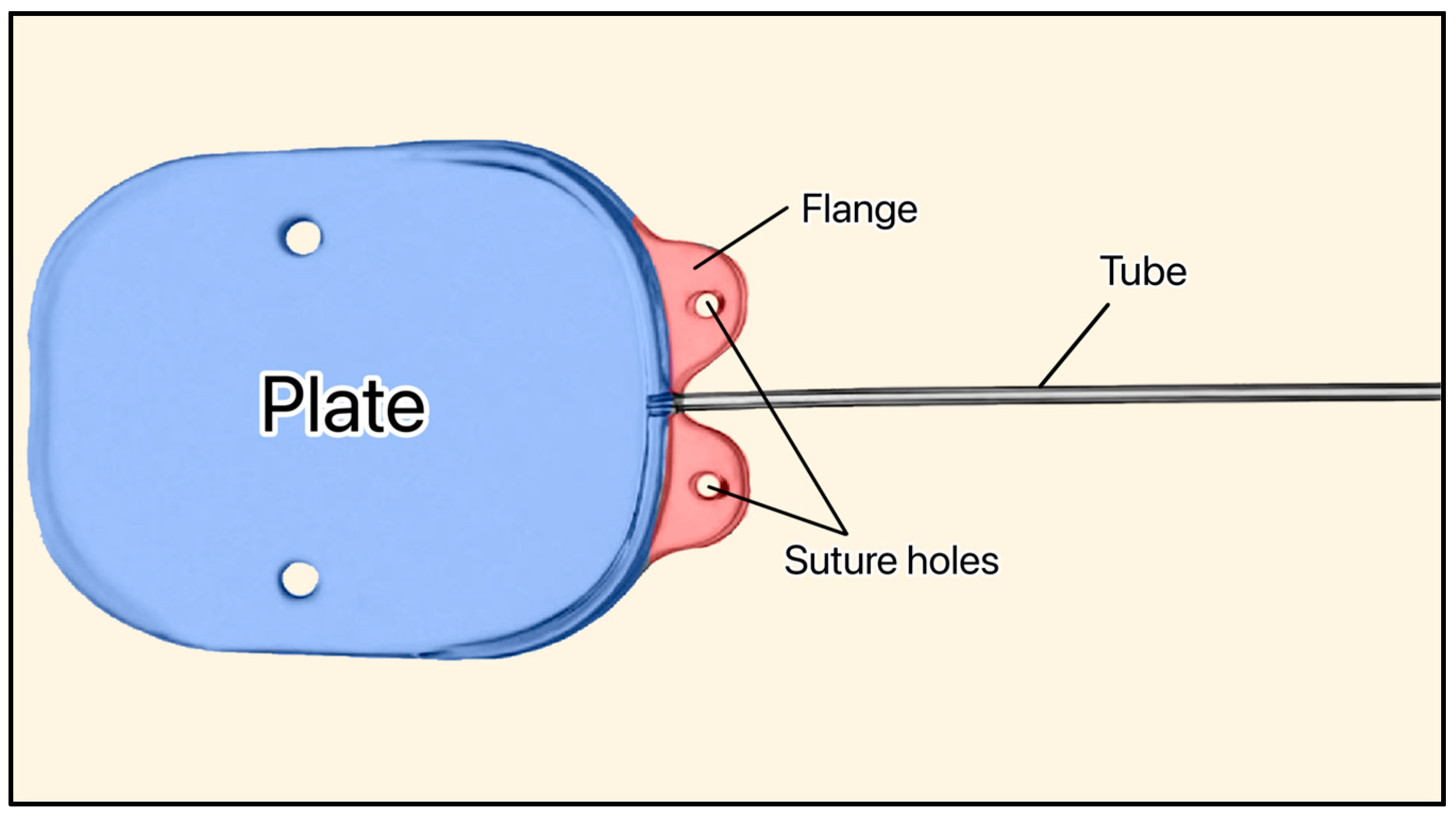

3.13. Susanna GDD

The Susanna GDD (not FDA approved) was developed by Dr. Remo Susanna and colleagues at the University of São Paulo (Brazil) [43]. It is a nonvalved silicone plate with two holes on the flanges for fixation to the sclera (Figure 18) [43]. The original version of the device had an elliptical-shaped plate (350 mm2) [43]. The new version of the device has a plate size of 200 mm2 and is soft enough to adjust to the shape of the eye [43]. Its total thickness (0.5 mm) makes it thinner than the Ahmed (1.9 mm) and Baerveldt (0.84 mm), and the tube dimensions are ID = 230 μm and OD = 530 μm [43].

Figure 18.

Susanna GDD showing the plate, flange, and suture holes. Adapted from [43].

A study by Biteli et al. at the University of São Paulo, Brazil in 2017 found that among 58 patients, the Susanna GDD lowered the mean IOP from 31.5 to 12.6 mm Hg (60%) and had a 73% success rate (defined as IOP < 21 mm Hg) for neovascular and 86% for refractory open-angle glaucoma [44]. A more recent study by Susanna et al. in 2021 found a 13.6% failure rate after one year, with severe complications occurring in 4.5% of patients [43].

3.14. Introduction to Suprachoroidal-Supraciliary Devices

Suprachoroidal devices, such as the SOLX Gold Shunt, CyPass Micro-Stent, and the Aquashunt, occupy a distinct category that is neither a traditional GDD nor a true MIGS procedure, although they are sometimes classified as one or the other [45]. These implants function by creating a controlled pathway for AH into the suprachoroidal or supraciliary space, thereby enhancing uveoscleral outflow rather than relying on SC bypass or subconjunctival bleb formation. Based on anatomy, supraciliary (above the ciliary body) implants are typically smaller in size compared to suprachoroidal (above the choroid) devices. This section will review examples of these devices [45].

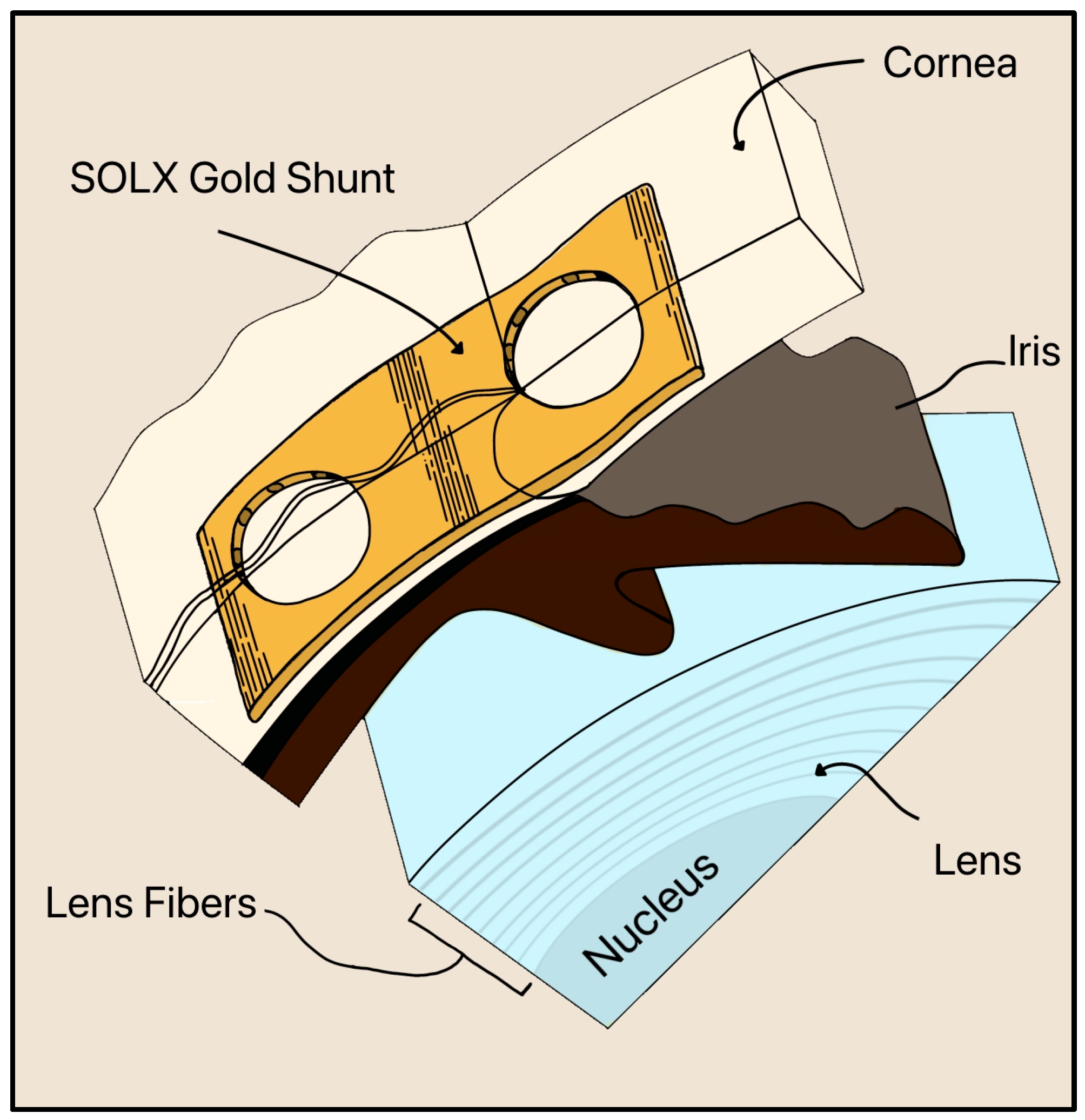

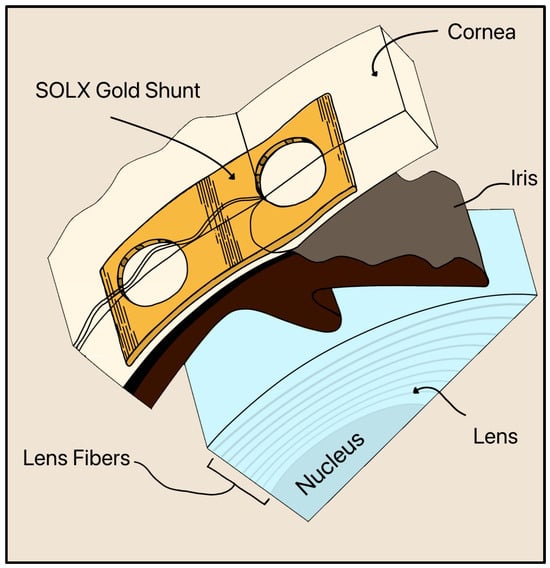

3.15. SOLX Gold Shunt

Gold is still utilized in a newer device called the SOLX Gold Shunt, invented by Gabriel Simon in 2005 [46]. The SOLX Gold Shunt is a flat, biocompatible implant designed for suprachoroidal placement to lower IOP by creating a direct pathway for AH outflow from the AC to the suprachoroidal space (Figure 19) [46]. The device is made of pure (24-karat) gold and measures approximately 5–10 mm in length and 3 µm in thickness. It contains longitudinal microchannels within a planar body sealed by thin gold membranes (2 µm thick) that can be selectively opened postoperatively using a titanium-sapphire laser (750–800 nm) [46]. Fenestrations may be created, enlarged, or closed with laser energy, allowing adjustable control of outflow after implantation.

Figure 19.

Cross section of the inserted SOLX Gold Shunt implant in the suprachoroidal space. The cornea, iris, and lens are also shown. Adapted from [46].

Although the SOLX Gold Shunt generated early interest as a biocompatible, supraciliary outflow device, subsequent clinical data have been largely unfavorable. In a prospective pilot study performed in 2009, IOP was reduced from 27.6 ± 4.7 to 18.2 ± 4.6 mm Hg at 12 months (~9-mm Hg, 32.6% reduction) [47]. Multicenter cohorts demonstrated poor long-term survival, with complete surgical success rates of 14%, 9%, and 0% at 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively, largely due to fibrosis, membrane occlusion, and inadequate long-term outflow [48]. Compared with other supraciliary or suprachoroidal approaches, the SOLX device exhibits substantially poorer durability and higher failure rates and is no longer commercially available in most markets [48].

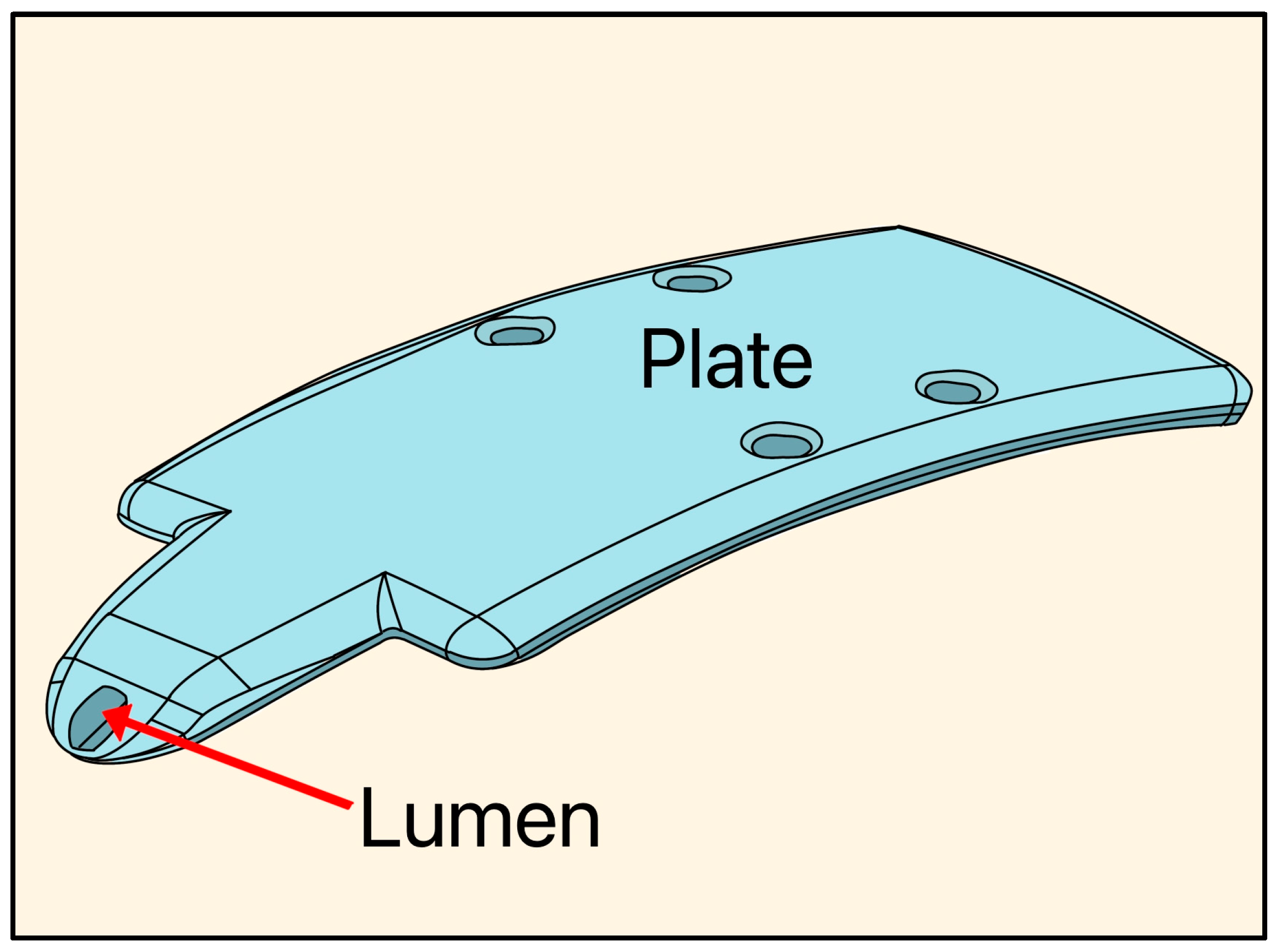

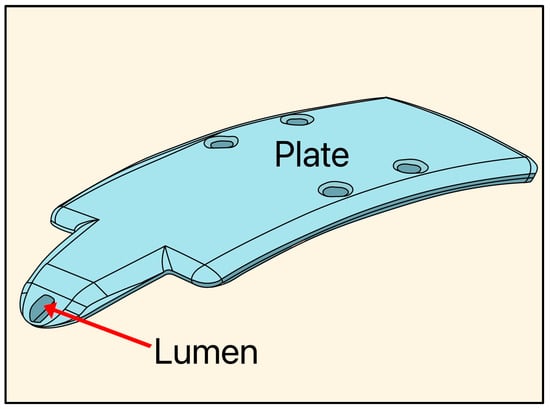

3.16. Aquashunt Glaucoma Filtration Device

The Aquashunt glaucoma filtration device was designed in 2009 by Bruce Shields, MD at Yale University and acquired by OPKO Health (Miami, FL, USA). The implant is made of polypropylene, and its dimensions are 4 mm wide × 10 mm long × 0.75 mm thick, with a single lumen of 250 µm, designed as a suprachoroidal device (Figure 20) [49].

Figure 20.

Diagram of the Aquashunt glaucoma filtration device showing the lumen and plate. Adapted from [49].

An early human trial consisting of 15 patients described IOP reduction of 31% at 8 months [50]. The complications included device explantation (6.7%), inadequate IOP lowering (20%), and hypotony (20%). Due to these limitations in early clinical trials, the device was not ultimately advanced in the U.S.

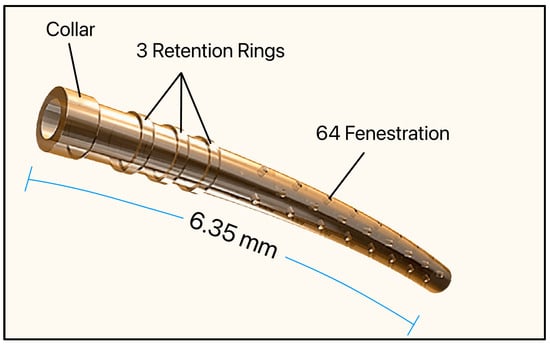

3.17. CyPass Micro-Stent

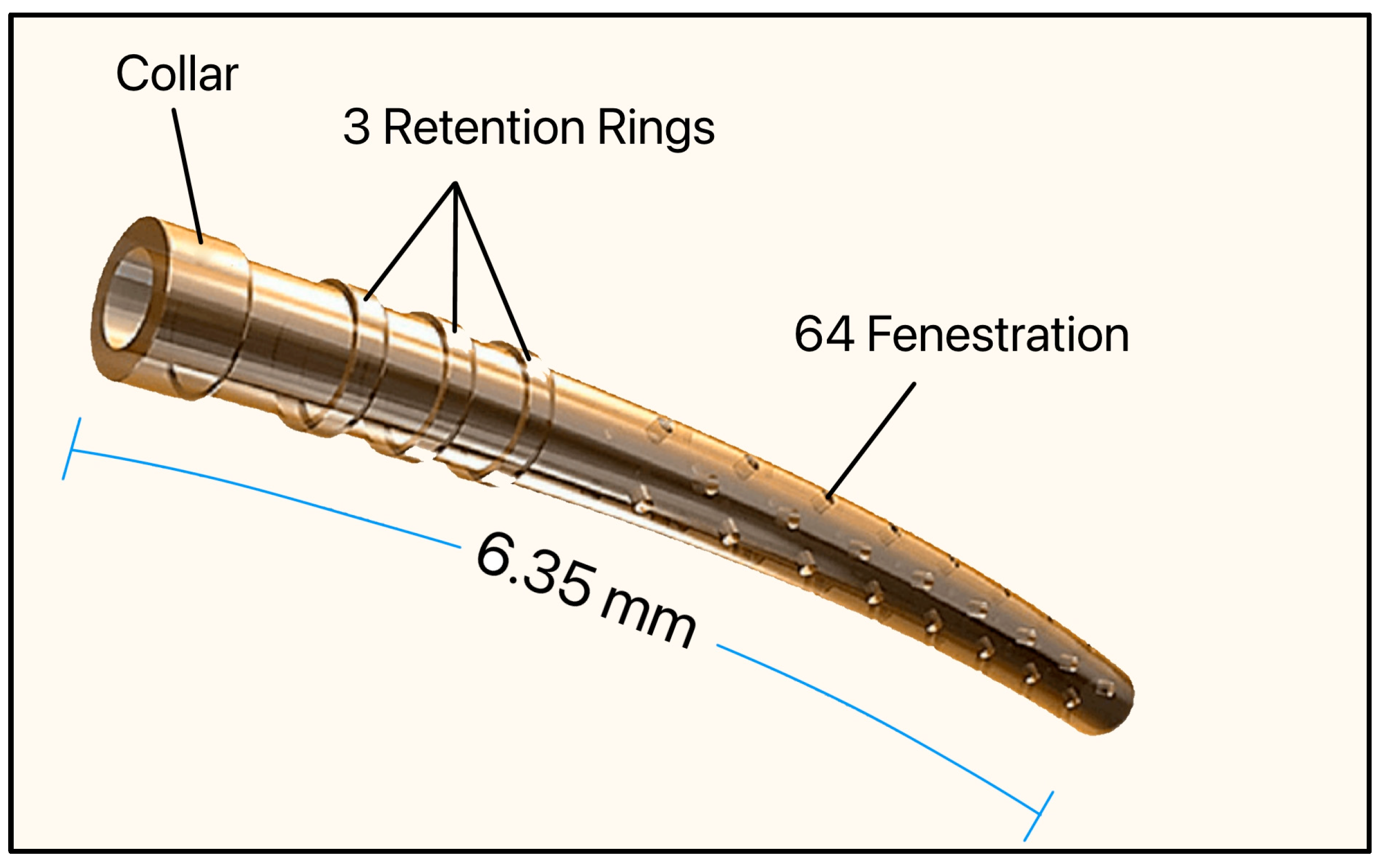

The CyPass Micro-Stent (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was approved by the FDA in 2016. It consisted of a non-biodegradable and biocompatible polyimide tube, 6.35 mm long with an OD and ID of 430 µm and 300 µm, respectively, and had a collar (530 µm), 3 retention rings (510 µm), and 64 fenestrations (76 μm in diameter) [51]. Polyimide was chosen as the biomaterial due to its known inert and biocompatible properties (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

The Cypass Micro-Stent showing the collar, retention rings, and fenestrations. Adapted from [51].

The device was supplied with a preloaded inserter and consisted of a guidewire and a front button for deployment and a back button for retraction, and the stent was placed in the suprachoroidal space ab interno and functioned to increase AH flow through the uveoscleral pathway. The device was approved as a standalone procedure or in combination with cataract surgery.

The early COMPASS trial study showed a 30% reduction in mean IOP and a 50% decrease in patients requiring anti-glaucoma drops one year after surgery [52]. However, based on the long-term follow-up, COMPASS-XT, the device caused significant corneal endothelial complications and was voluntarily withdrawn from the global market in 2018 [53]. One clinical study showed corneal endothelial cell loss that persisted for over 5 years, largely attributed to improper placement and progressive displacement into the AC [54].

3.18. Introduction to Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries (MIGS)

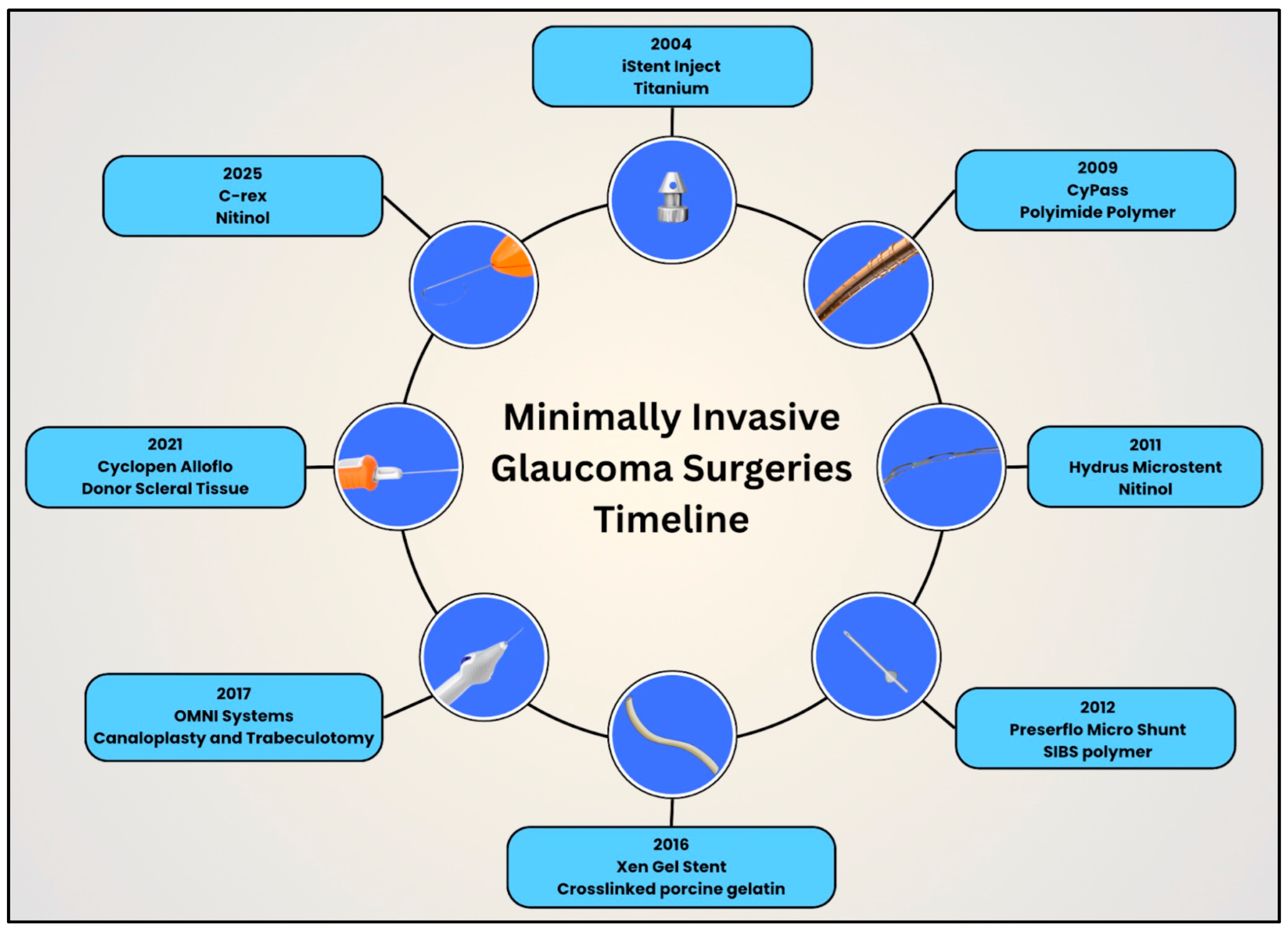

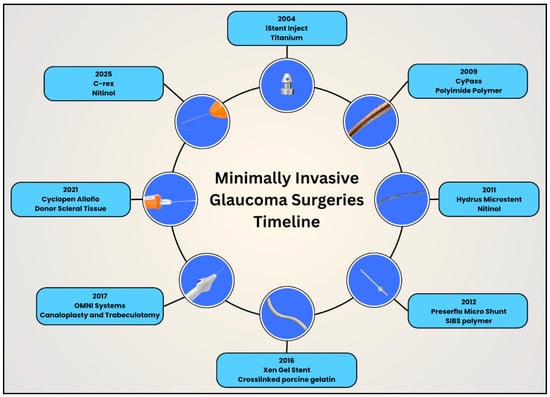

With the turn of the 21st century, the glaucoma surgical field benefited from continued advancements in MIGS. Ophthalmologists can now offer MIGS for mild to moderate glaucoma, unlike traditional glaucoma filtering surgeries and GDDs [55]. This proactive, upstream approach helps to control IOP early in the disease course and thereby reduce the likelihood of irreversible vision loss. One important factor in the development of MIGS has been the parallel advancement of biomaterials, which has allowed for the creation of smaller, safer, and more biocompatible implants. These innovations, together with advances in design and controlled fluid flow, continue to shape the effectiveness, longevity, and safety profile of MIGS procedures today. This section discusses the evolution of design, biomaterials, and techniques using MIGS (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Timeline illustrating the evolution of design and biomaterials in minimally invasive glaucoma surgery devices in clockwise, chronological order.

3.19. iStent

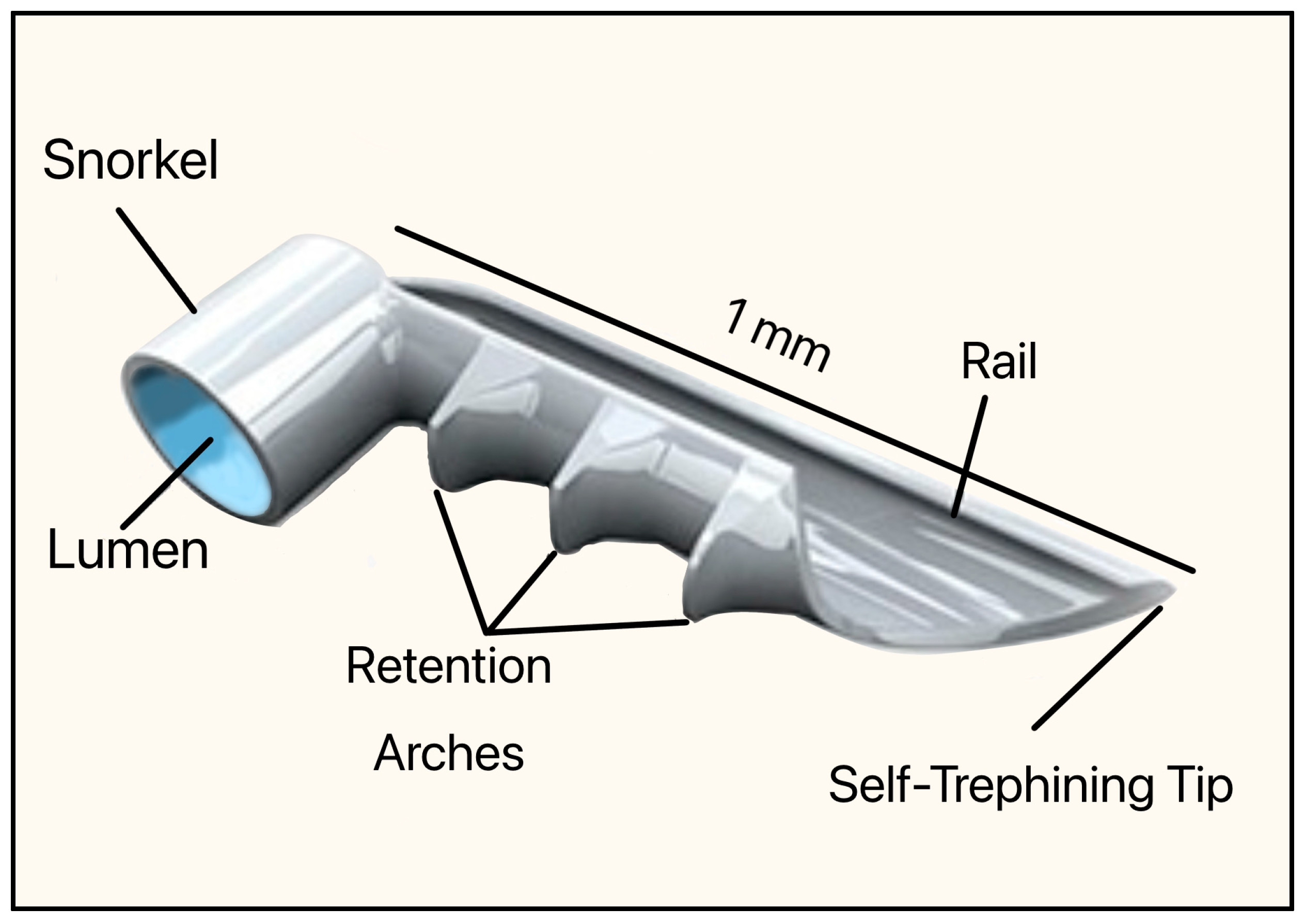

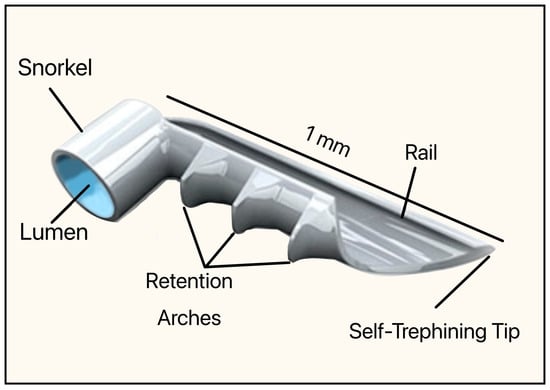

The iStent, designed by the Glaukos Corporation (San Clemente, CA, USA), was the first MIGS device to gain FDA approval in June 2012. It was intended to reduce IOP in adult patients with mild to moderate open-angle glaucoma undergoing cataract surgery [56].

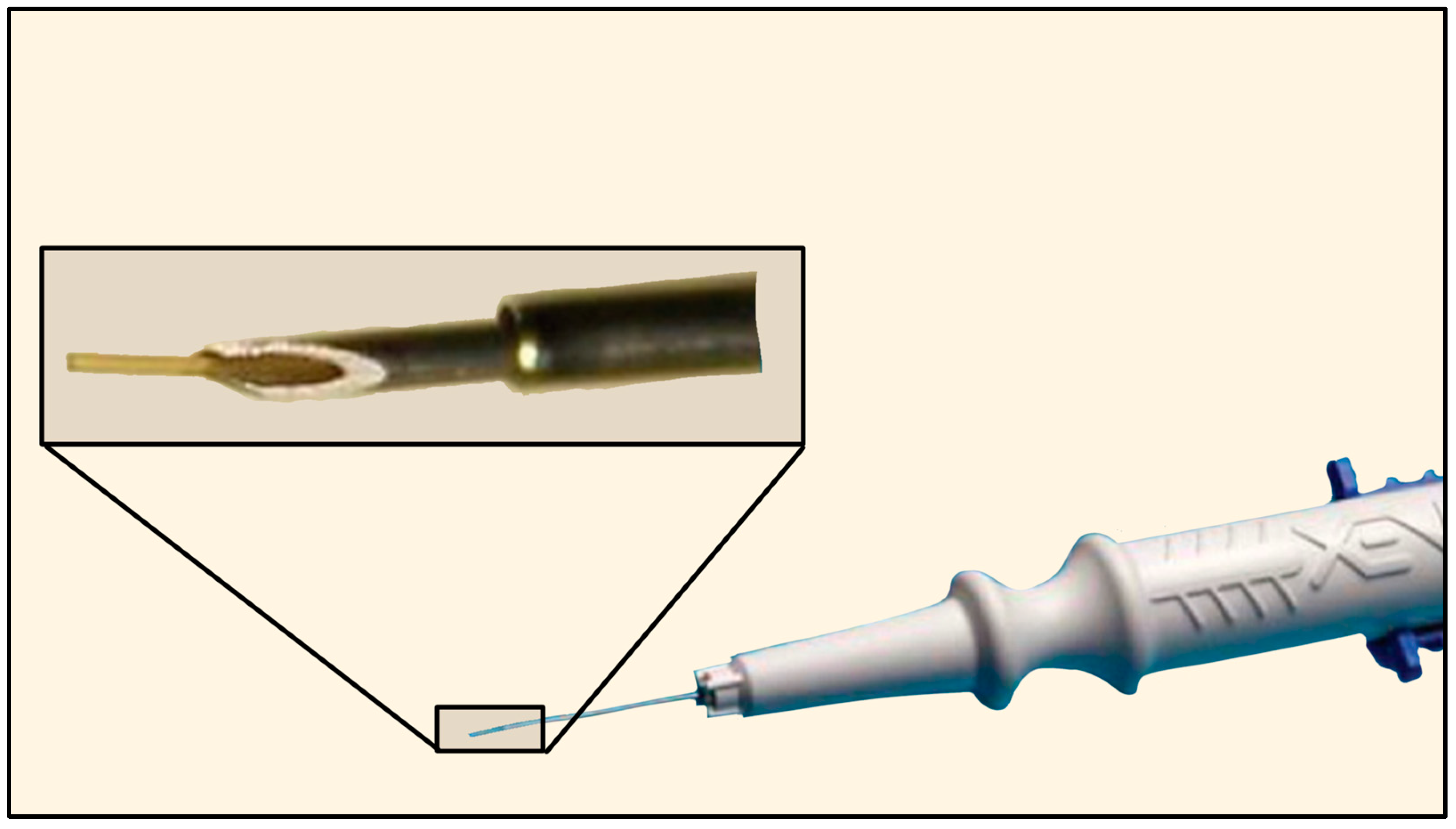

This implant was made of non-ferromagnetic titanium and coated with heparin (prevents blood clots and platelet activation). The dimensions were 1 mm in length and 0.33 mm in height, with an OD of 120 µm (Figure 23). It consisted of a short snorkel and lumen, which were designed to drain the AH from the AC into SC. The retention arches secured the device within the SC, the rail stabilized its position along the canal lumen, and the tip facilitated atraumatic entry and anchoring of the implant. The device required an inserter, which was a single-use, preloaded handpiece with an applicator tip that allowed ab interno delivery into the SC.

Figure 23.

Original version of the iStent, Model GS100R showing the snorkel, lumen, retention arches, rail, and self-trephining tip. Courtesy of [56].

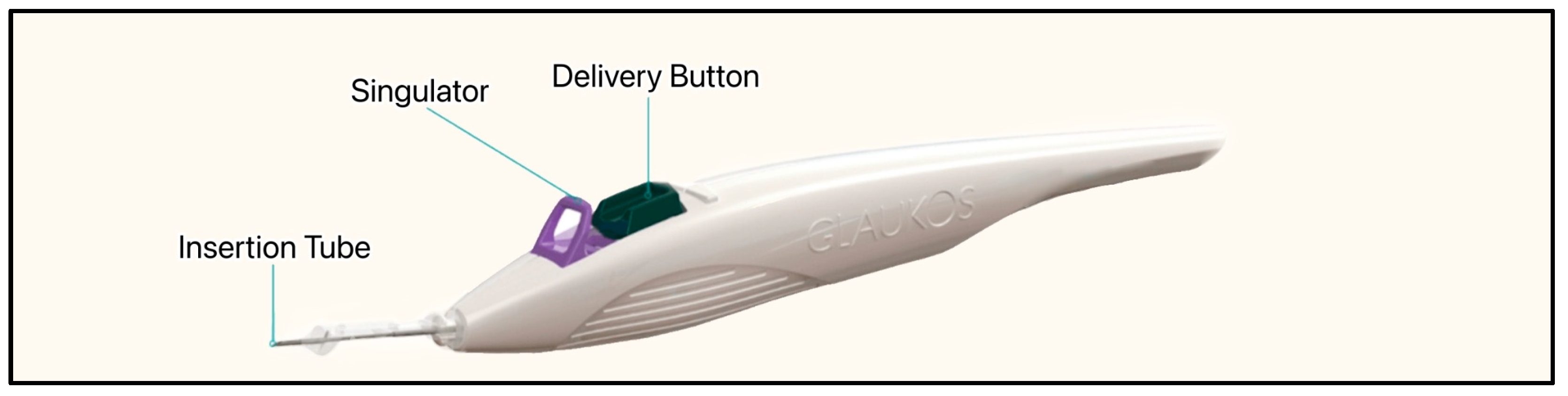

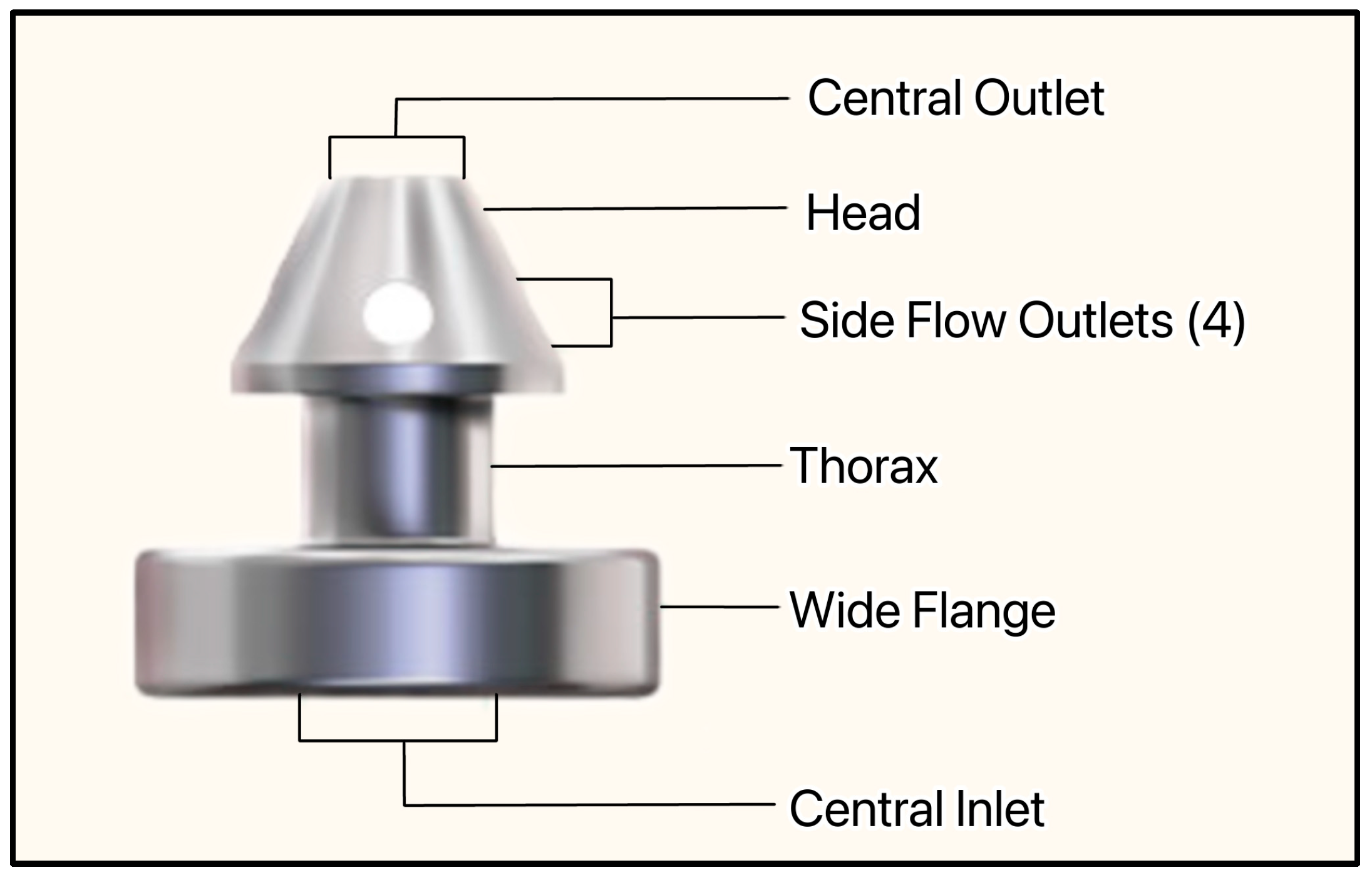

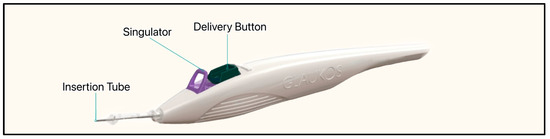

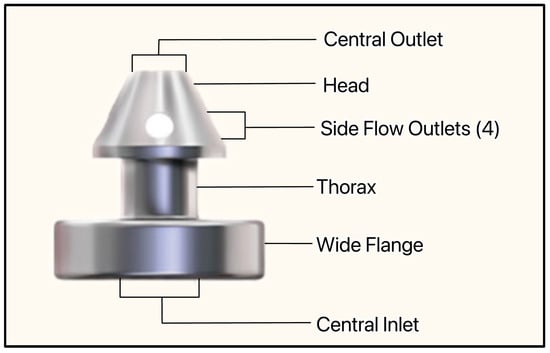

The most recent iteration of the device, the iStent Infinite, is approximately one-third the size of the original device, has three pre-loaded stents on a single-autoinjector system, and an 8° angled insertion tube which minimizes incision interference and eases stent delivery (Figure 24) [57]. The iStent Infinite has a diameter of 360 µm and a lumen of 80 µm (Figure 25). By delivering three implants, the iStent Infinite treats a larger segment of SC, thus increasing outflow facility [57].

Figure 24.

The iStent infinite injector system showing the anterior insertion tube, singulator, and delivery button. Courtesy of [58].

Figure 25.

The iStent infinite showing the central inlet, wide flange, thorax, side flow outlets, head, and central outlet. Courtesy of [58].

Both the past and present versions of the iStent bypass the TM, providing direct aqueous access to SC and downstream collector channels. Common complications include IOP spikes, stent obstruction or malposition, and hyphema [59].

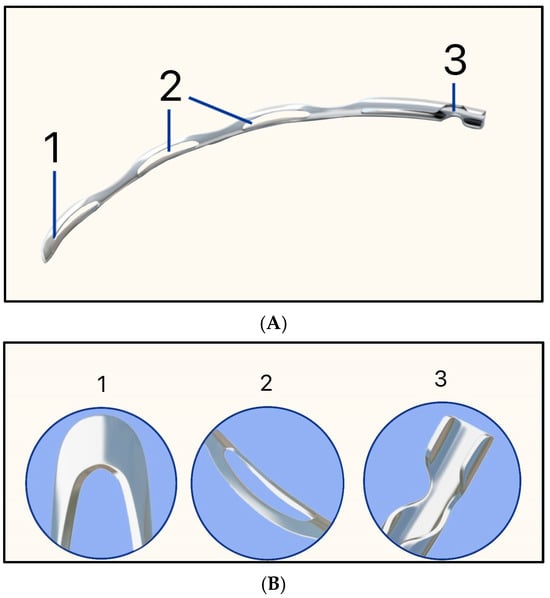

3.20. Hydrus Microstent

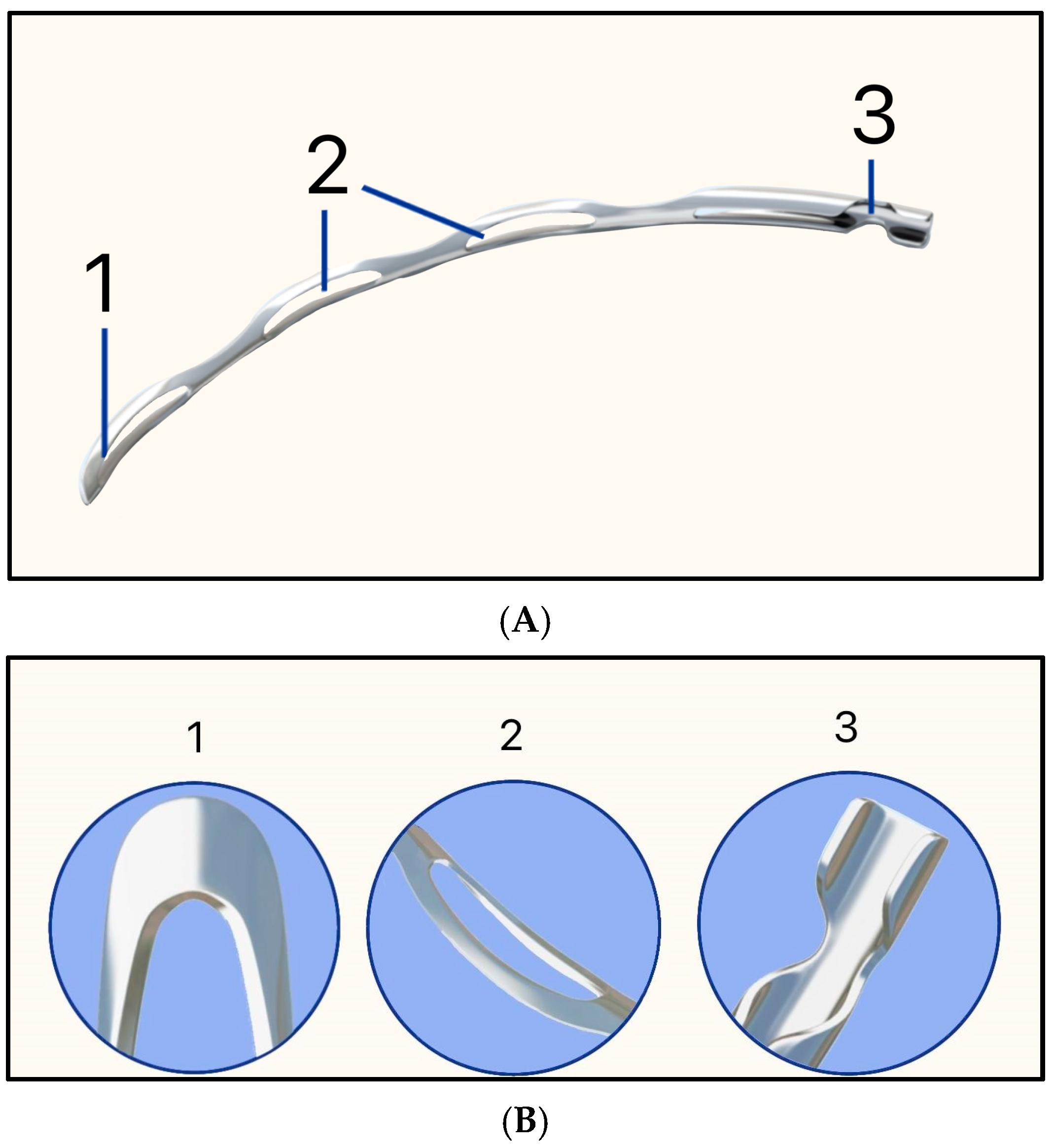

The Hydrus Microstent was developed by Ivantis (now Alcon) and was approved by the FDA in 2018. The implant is an 8 mm flexible nitinol scaffold (55% nickel and 45% titanium) that spans approximately 90° of SC via ab interno implantation [60,61]. The device is recommended for use in conjunction with cataract surgery. It contains a rounded distal tip for smooth passage into SC, and the inlet facilitates flow from the AC (Figure 26A,B) [60,61].

Figure 26.

Hydrus MicroStent illustrating (A) 1 = Rounded distal tip, 2 = Open-window scaffold, and 3 = Aqueous inlet; (B) Higher magnification of each component. Adapted from https://www.myalcon.com/professional/glaucoma/hydrus-microstent/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

In the HORIZON clinical trial, IOP was reduced by 31.7%, and intra-operative complications included hyphema (1%), cyclodialysis cleft (0.3%), iridodialysis (0.3%), malposition in the iris root (0.3%), and Descemet membrane detachment (0.3%) [62].

3.21. Preserflo MicroShunt

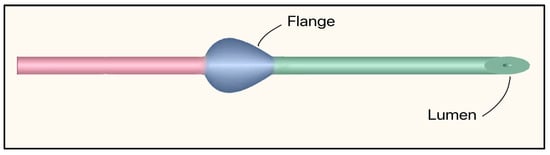

The concept and early prototypes of Preserflo Microshunt were developed by InnFocus, Inc. (Miami, FL, USA) with Leonard Pinchuk, PhD and collaborators at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in 2015. In 2016, Santen Pharmaceutical (Osaka, Japan) acquired InnFocus and subsequently commercialized the device, which was called InnFocus MicroShunt initially, as Preserflo [63,64,65]. The device received CE Mark in Europe in 2012; however, in the United States, the FDA issued a non-approvable letter in 2022. As of 2025, U.S. approval remains pending with active ongoing regulatory work [64].

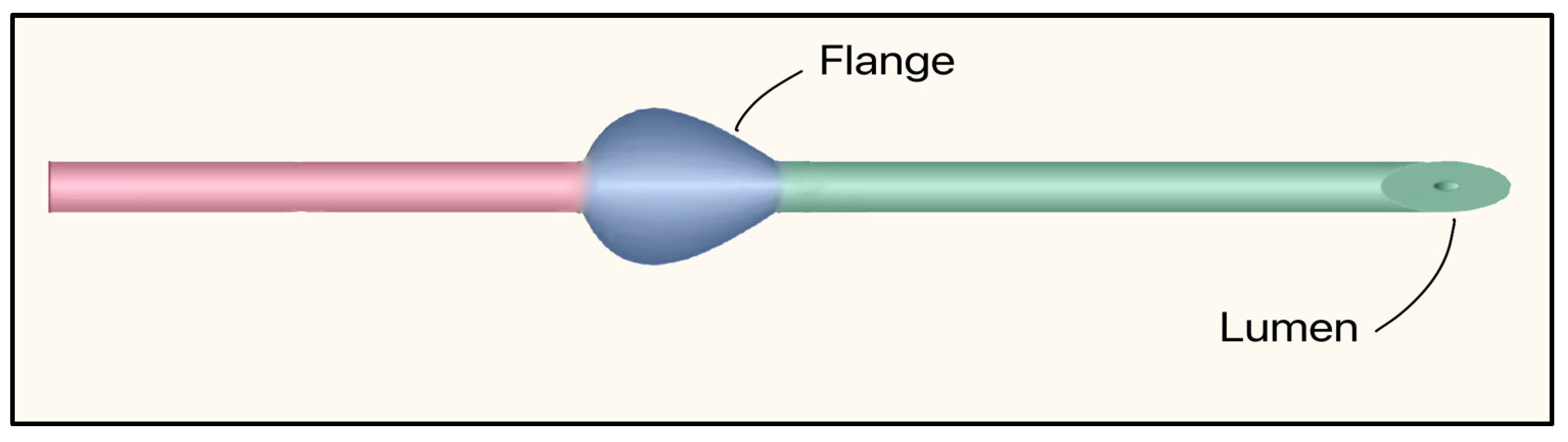

The Preserflo™ MicroShunt is a plateless, valveless ab-externo microshunt that relies on intrinsic flow resistance (ID 70 µm, OD 350 µm) to limit AH flow and hypotony. It is made of SIBS (poly[styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene]), a highly bioinert elastomer, and features a bevel up proximal tip. It contains a flange that is designed to be placed in a scleral pocket for fixation (Figure 27). The dimensions are 8.5 mm in length, and the 1 mm fixation flange divides the device into proximal and distal segments [63]. Implantation requires a needle tract (25–27 G), 2.5–3 mm posterior to the limbus. Then the microshunt is threaded in, bevel up, placing the flange in the scleral pocket, and often combined with anti-fibrotic mitomycin-C (MMC) [66].

Figure 27.

Preserflo MicroShunt showing the flange and lumen. The proximal segment (connecting the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space) is shown in green, and the distal segment (tail that releases aqueous humor into the filtering bleb) is shown in red. Adapted from [63].

The Preserflo device is mainly indicated for the management of open-angle glaucoma and refractory cases, both as a standalone procedure and in combination with cataract surgery. Clinical studies consistently demonstrate significant IOP reduction from baseline (42.4–55%). Surgical success rates (IOP < 21 mmHg) ranged from 60–80% at 1–3 years, with a sustained efficacy up to 5 years in long-term series [65,66]. Adverse effects included transient hypotony (13%), hyphema (9%), choroidal detachment (9%), and needling (1.6%) or surgical revision of the bleb (15.6%) [66].

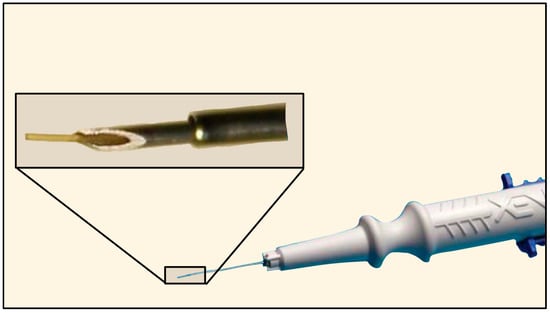

3.22. Xen Gel Stent

The XEN® Gel Stent (XEN45) was initially developed by AqueSys, Inc. (Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) and later acquired by Allergan (Dublin, Ireland) in 2015, which was later bought by AbbVie (Chicago, IL, USA) in 2020. In the United States, the XEN45 received FDA approval in 2016. It is a valveless ab-interno device made of gelatin derived from porcine dermis, cross-linked with glutaraldehyde, which softens and hydrates in vivo [67]. The XEN63 was introduced in 2020 as a newer model of the device with a larger ID of 63 µm. Both are supplied in a pre-loaded, single-use injector with a retractable 27-G needle for delivery through a limbal incision. The tube length is 6 mm for both the XEN45 and XEN63, with a 45 µm or 63 µm ID and 150 µm OD (Figure 28) [67,68].

Figure 28.

The Xen Gel Stent with magnification of the distal tip. Courtesy of https://www.xengelstent.com (accessed on 9 December 2025).

A XEN implant can be used as a standalone procedure or combined with cataract phacoemulsification. Surgical success rates range from 35% to 70% at 1–2 years, and adverse effects include hypotony (39%), stent occlusion (3.9–8.8%), wound leaks (2.1%), stent exposure (1%), or endophthalmitis (0.4–3%) [68].

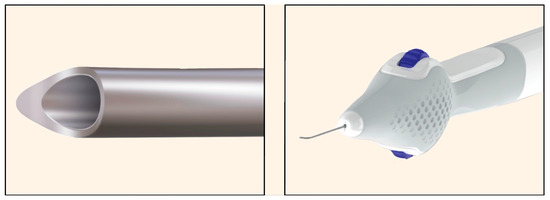

3.23. Omni Surgical System

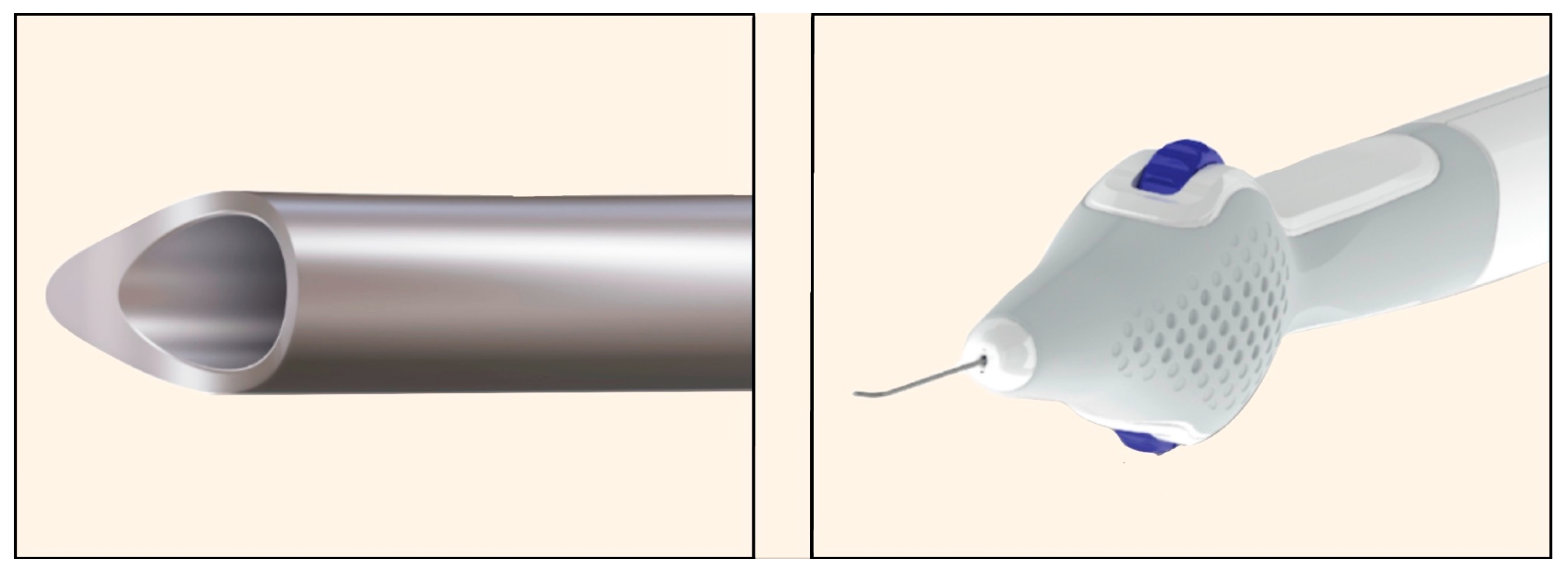

The OMNI platform (Sight Sciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA), launched in 2023, is an implant-free, ab interno surgical device designed for combined canaloplasty (viscodilation of SC and collector channels) and 360° trabeculotomy [69]. The cannula is advanced with a finger-wheel control handle, enabling it to traverse the SC and perform viscodilation concurrently (Figure 29) [69].

Figure 29.

OMNI Surgical System. (Left): Distal tip of the cannula. (Right): Finger-wheel control handle enabling rotation of the cannula tip. Courtesy of https://omnisurgical.com/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

In a large multicenter cohort, OMNI surgery (with or without concurrent phacoemulsification) achieved a 20% decrease in IOP in 80.2% of patients with a good safety profile over 12 months [70]. Because it is implant-free, OMNI avoids device-specific complications such as migration or obstruction. However, it does require a clear view of the iridocorneal angle and is dependent on technique and surgeon experience [71].

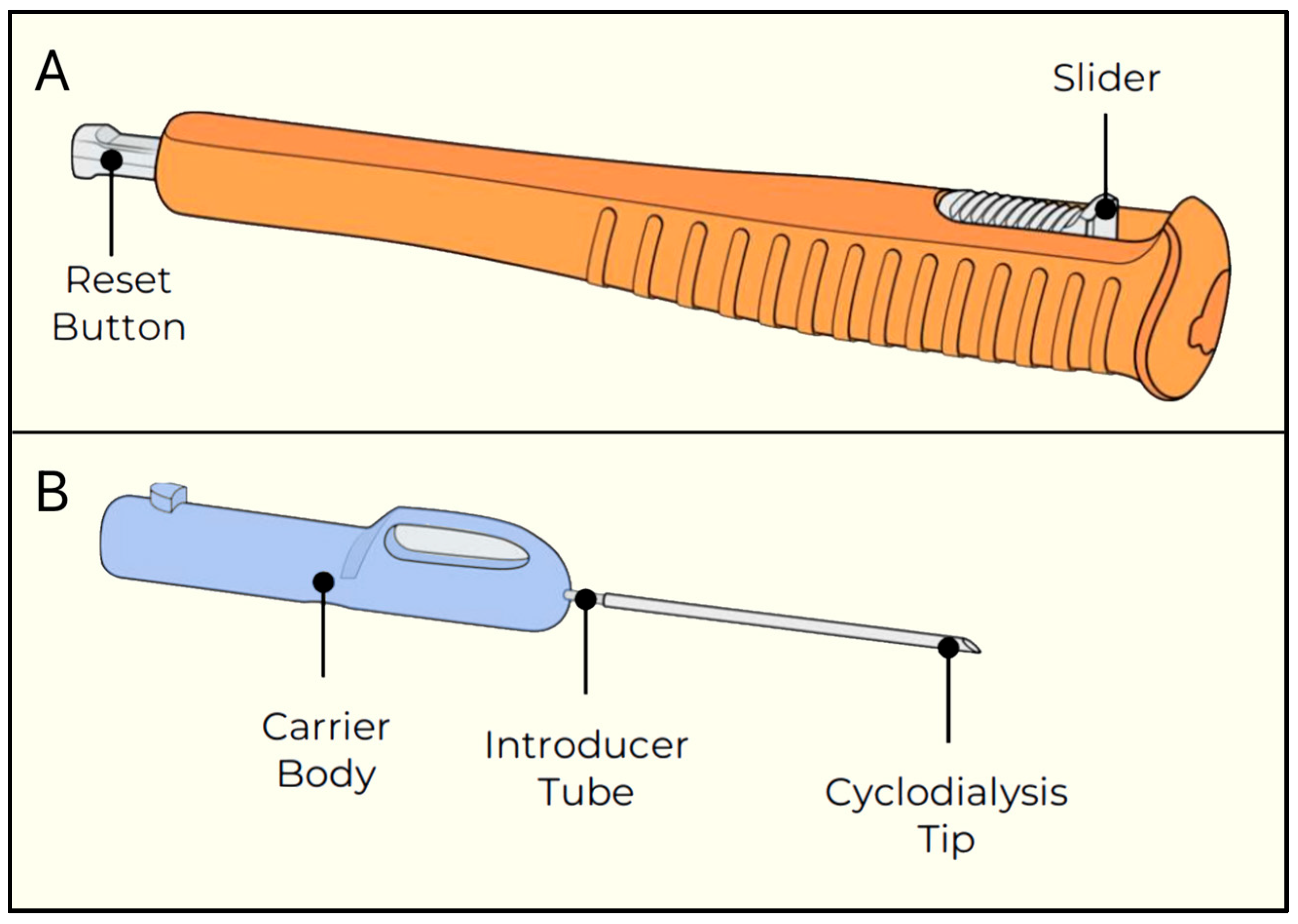

3.24. Alloflo Uveo

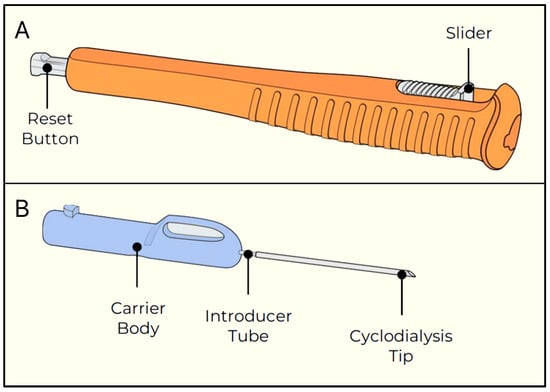

AlloFlo Uveo (Iantrek, White Plains, NY, USA) was introduced in 2025 and is made of naturally derived allogeneic bio-tissue (homologous graft material) configured to function as a bio-spacer without a permanent implant (Figure 30) [72]. It is designed to reinforce uveoscleral drainage by separating the ciliary body from the scleral spur (cyclodialysis cleft) [72].

Figure 30.

Alloflo Uveo insertion device. (A) The slider and reset button; (B) The carrier body attached to the introducer tube with the cyclodialysis tip. Courtesy of [72].

The procedure involves creating a micro cyclodialysis cleft, followed by insertion of the bio-tissue supporter. Early reported results show a significant 40% relative decrease in IOP and 42% fewer IOP-lowering medications after 12 months [73]. Additionally, post-operative complications are similar to those of other ab interno surgical procedures, such as hyphema, hypotony, shallow AC, and choroidal hemorrhage [73].

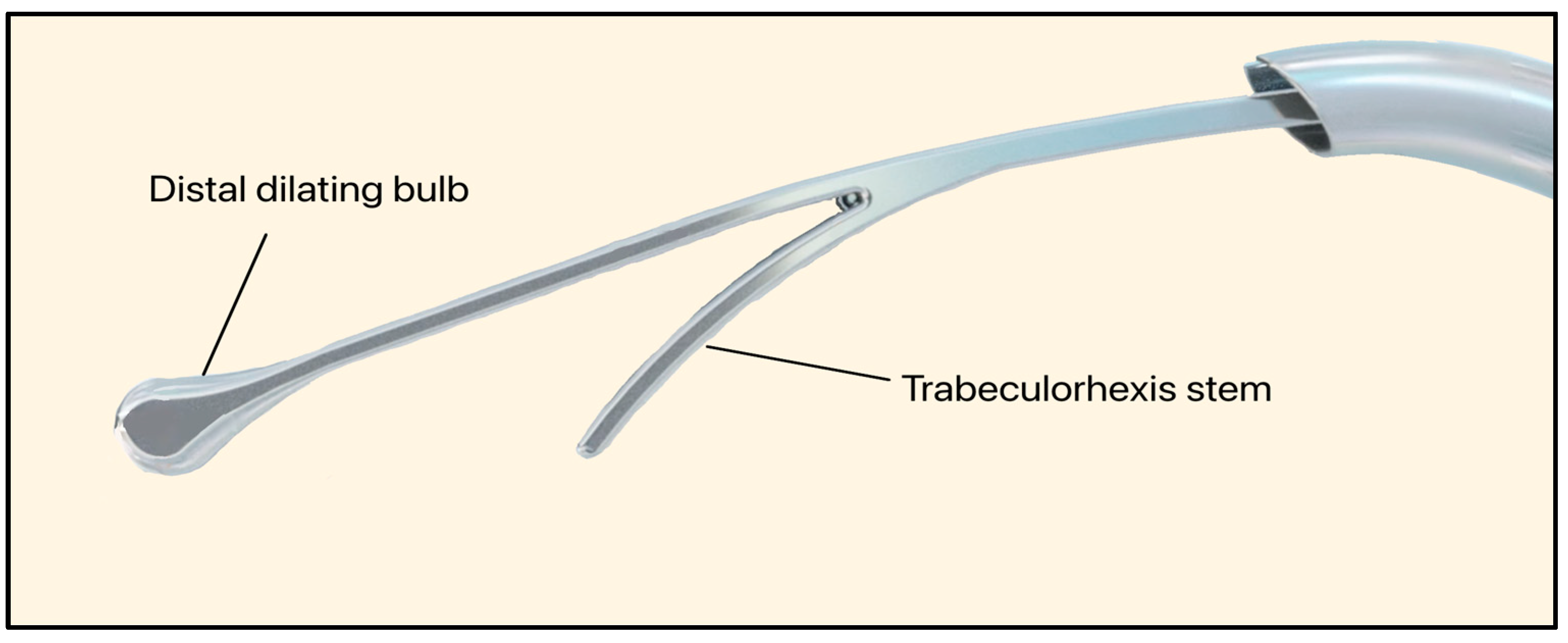

3.25. C-Rex System

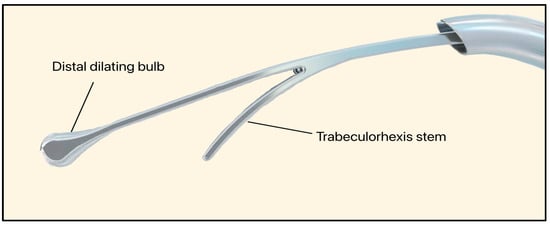

The C-Rex system (Iantrek, White Plains, NY, USA) is an FDA-approved glaucoma intervention designed by Sean Ianchulev M.D., the Iantrek founder. Introduced in early 2025, the C-Rex system consists of an elastic nitinol filament (80 μm wide) that can be delivered ab interno [74]. The device features a distal dilating bulb that expands SC (240 μm wide) and performs a 180–360° excisional trabeculorhexis goniotomy (Figure 31) [75].

Figure 31.

C-Rex System showing the distal dilating bulb and trabeculorhexis stem. Courtesy of [75].

Despite procedural promise, the non-implantable and traumatic nature of the C-Rex System makes it more liable to cause bleeding and subsequent fibrosis. Long-term data on IOP control, durability, and complications are not yet available.

3.26. Discussion

This review highlights advancements from the first gold wire shunt developed in the 1870s to present-day, technologically superior GDDs and MIGS. Advances have occurred thanks to gradual improvements in our understanding of glaucoma pathophysiology and our ability to engineer smaller, more biocompatible devices. Additionally, our knowledge regarding the immune system and fluid dynamics has enabled more precise optimization of biomaterial selection and flow dynamics. Many devices that are currently on the market, however, still suffer from a variety of complications related to material selection, flow optimization, and design characteristics. As a result, GDDs are largely restricted to more advanced glaucoma, while MIGS are typically utilized for mild to moderate cases. Even in these settings, postoperative complications such as corneal endothelial cell loss, hypotony, device obstruction, and fibrosis remain as significant barriers to long-term success.

From a materials standpoint, successive generations of plate-based GDDs have moved from rigid polypropylene endplates towards softer silicone or porous polyethylene designs to decrease inflammation, capsule formation, and plate encapsulation. Comparative work like the Krupin-Molteno rabbit study and long-term series of Ahmed, Baerveldt, AADI, and PAUL implants suggest that silicone plates are associated with less inflammation and better conformity to the globe than earlier polypropylene designs [24,27,28,29,33,42]. Similarly, MIGS devices rely on different material classes: SC-based implants use biocompatible metallic scaffolds with minimal TM footprint, whereas subconjunctival microshunts use soft, hydrophilic polymers and narrow lumens to generate low, diffuse blebs rather than mechanical valves [57,59,64,68]. These material choices exemplify how improvements in stiffness, surface chemistry, and lumen geometry have translated into smaller devices with fewer complications while maintaining clinically meaningful IOP reduction.

The quality of evidence was limited by the predominance of early-stage or prototype studies, small sample sizes, and heterogeneous reporting of outcomes such as IOP reduction and endothelial safety. Few studies included long-term follow-up or standardized definitions of success, and comparative head-to-head data remain scarce. Although this review followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines for transparency, the heterogeneity and engineering orientation of the included reports prevented quantitative synthesis or formal risk-of-bias evaluation. Additionally, exclusion of non-English articles and reliance on publicly available data may have omitted relevant findings.

3.27. Future Directions

Looking ahead to the future, increased interdisciplinary collaboration between basic scientists, bioengineers, and clinicians may allow for a more harmonious balance among biomaterial selection, design characteristics, and flow optimization, thus resulting in clinically meaningful IOP reduction with fewer complications. Additionally, new biomaterials are being introduced and demonstrate optimal biocompatibility, which historically has been one of the main obstacles to successful device design and utilization. This section will highlight some of the emerging biomaterials and design features of future hybrid GDDs/MIGS devices that may transform glaucoma management, allowing us to treat glaucoma earlier in the disease process with fewer complications.

3.28. Emerging Biomaterials

As device failure is often driven by fibrosis, biofouling, or AH outflow obstruction, emerging biomaterials aim to directly address the biological and mechanical limitations identified in prior generations of GDDs and MIGS. These next-generation polymers, hydrogels, nanostructured surfaces, and degradable scaffolds are being engineered to reduce inflammatory signaling, improve tissue integration, and maintain long-term patency of micro-lumens. Modern biomaterial science is shifting device design away from inert substrates toward materials that actively modulate the wound-healing environment, stabilize outflow, and extend device longevity. Table 3 provides an overview of these developing biomaterials, highlighting their key properties, advantages, and current limitations. Although Table 3 presents these emerging biomaterials in a unified framework, they are used in a variety of devices. In general, hydrogel-based and degradable polymers such as chitosan, PEG, HA, PLGA, and PCL are mainly being explored as surface coatings, drug-eluting matrices, or porous scaffolds for subconjunctival plate-based GDDs and bleb-forming microshunts. Mechanically robust structures such as nitinol, magnesium alloys and nano-engineered ceramic or diamond coatings are more often aligned with canal-based, suprachoroidal, and hybrid MIGS/GDDs. We therefore discuss these materials together to emphasize that the same design principles are applied across both traditional GDDs and MIGS, even though the underlying material and anatomic targets differ.

Table 3.

Summary of the key properties, advantages, and limitations of emerging biomaterials.

3.29. Future GDDs/MIGS Devices

Advances in biomaterial science have enabled the development of hybrid GDDs and MIGS devices that incorporate novel flow-control mechanisms, porous or nano-textured scaffolds, degradable membranes, and magnetically or mechanically adjustable components. These concepts represent a shift from traditional passive shunts toward adaptive, tunable, and biologically responsive implants that seek to overcome longstanding challenges such as fibrosis, hypotony, clogging, and unpredictable long-term performance. To contextualize the diverse technologies currently under development, Table 4 summarizes the major types of future devices, their mechanisms, developmental stages, and defining design features.

Table 4.

Summary of future GDDs/MIGS device concepts, development stages, and key points.

Among the emerging device concepts, two systems, the CorNeat eShunt and Visiplate, have progressed to advanced clinical evaluation and exemplify how novel biomaterials are being translated into functional glaucoma implants. The CorNeat eShunt utilizes an EverMatrix™ bio-integrative scaffold, designed to promote stable fibroblast ingrowth and long-term anchoring while diverting AH into the retro-orbital space, thereby reducing conjunctival inflammation and fibrosis [107]. In contrast, Visiplate employs a corrugated aluminum-oxide plate coated with a thin parylene-C polymer, leveraging nanoscale surface engineering to enhance flexibility, reduce protein adhesion, and distribute outflow more evenly across a larger surface area [108]. These devices highlight the direction of current biomaterials research, which focuses on improving tissue compatibility, minimizing scarring, and optimizing fluid dynamics through engineered micro- and nano-structured surfaces. Together, they represent the leading edge of clinically viable biomaterial innovations and serve as a bridge between experimental materials and next-generation commercial implants.

3.30. Proposed Metrics to Evaluate GDDs/MIGS

Direct comparison of GDDs and MIGS implants remains challenging due to the absence of standardized metrics for evaluating their design, material properties, and surgical behavior. Current studies often report heterogeneous outcomes using inconsistent descriptors, making it difficult to objectively assess performance across device classes. To address this gap, we propose a set of core comparative metrics that capture key features influencing biocompatibility, flow dynamics, surgical complexity, and long-term efficacy (Table 5). These parameters may provide a foundation for more uniform reporting and facilitate meaningful cross-device comparison for future research.

Table 5.

Proposed standardized metrics for comparing glaucoma drainage devices and minimally invasive glaucoma surgery implants. The table outlines key device characteristics (plate surface area, surgical approach, bleb dependence, material composition, and flow-modulation design) and explains their relevance to device performance and clinical outcomes.

4. Conclusions

This review outlines the evolution of GDDs and MIGS from early setons and trephines to contemporary valved plates and microshunts, and it summarizes emerging biomaterials and prototypes that will shape the next generation of designs. Significant advancements have enabled current devices to regulate AH outflow intrinsically in a predictable manner via valve mechanisms, lumen sizing, or microchannel resistance. These advancements have significantly reduced the incidence of post-operative hypotony and vision-threatening complications compared to early devices. Concurrently, growing recognition of the AH-borne cytokines and fibroblasts that cause fibrosis has prompted a renewed respect for AH and the need to release it in a slow, controlled fashion [110].

Across surgical pathways, trade-offs are pathway specific; subconjunctival bleb-forming shunts like the Baerveldt and Ahmed shunt achieve IOP reduction but remain vulnerable to encapsulation. On the other hand, devices using TM and SC approaches, such as the iStent and Hydrus, prioritize safety and earlier use that may yield more modest pressure reduction. Additionally, subconjunctival microshunts like the Xen and Preserflo rely on intrinsic ocular resistance rather than valves, thus balancing efficacy with simplified implantation. Lessons from prior suprachoroidal/supraciliary designs highlight migration risk and damage to endothelial corneal cells, underscoring precise placement and stable anchoring.

Persistent failure mechanisms of the current devices include fibrotic encapsulation, occlusion, tube/plate exposure, bleb morbidity, and corneal endothelial cell loss, which remain the primary barriers to early use and long-term durability. These complications reflect limitations of current GDD and MIGS designs and materials, which mostly rely on passive, fixed-geometry implants. They cannot actively modulate wound healing, prevent microaccumulation, or adapt to outflow as the ocular environment changes over time.

As glaucoma care shifts to earlier in the disease course, designs should emphasize simplified implantation, reproducible placement, and cost-conscious manufacturing to support equitable global access without compromising safety. Future GDDs and MIGS devices may have dynamic properties that allow clinicians to adjust devices post-implantation, provide drug elution to control inflammation and IOP, and include sensors to measure IOP post-operatively. In summary, as of June 2025, the field is converging on safer, earlier, and more customizable outflow controls. This promise will require safe and durable biomaterials harmonized with effective design to sustain long-term biocompatibility, adjustability, and access.

Future generations of GDDs and MIGS should contain materials that couple long-term biostability with a low chronic inflammatory profile. This can be achieved by incorporating surface chemistries or drug-eluting strategies that reduce fibrosis and protein deposition. Additionally, future devices should offer tunable mechanical compliance and permeability so that AH outflow can be maintained without inducing hypotony, endothelial cell loss, or device erosion. Lastly, these materials must be compatible with miniaturized, microfabricated designs and image guided or ab-interno delivery to enable earlier intervention while preserving the ability to maintain a stable outflow pathway over decades of disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T., N.S. and K.K.; Methodology, H.T.; Software, H.T.; Data Curation, H.T., N.S., A.S. (Amirmohammad Shafiee), N.W., P.J., S.B. and K.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.T., N.S., A.S. (Amirmohammad Shafiee) and N.W.; Writing—review and editing, K.K., H.T., N.S., A.S. (Amirmohammad Shafiee), A.S. (Amirmahdi Shafiee), P.J. and N.W.; Visualization, H.T., A.S. (Amirmahdi Shafiee) and P.J.; Supervision, K.K.; Project Administration, K.K., H.T. and N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as this is a retrospective review of published data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study would be made available to researchers upon appropriate request. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

BioRender® (Toronto, ON, Canada) and Canva® (Surrey Hills, Sydney, Australia), Apple iOS Sketchbook (v 6.2.3, Cupertino, CA, USA), Microsoft PowerPoint (v 16.103.4, Redmond, WA, USA), and ibisPaint X (v 13.1.17, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan) programs were used by the authors to make or significantly edit the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GDDs | Glaucoma Drainage Devices |

| MIGS | Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries |

| AH | Aqueous Humor |

| ON | Optic Nerve |

| POAG | Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma |

| IOP | Intraocular Pressure |

| TM | Trabecular Meshwork |

| SC | Schlemm’s Canal |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

| ID | Inner Diameter |

| OD | Outer Diameter |

| SA | Surface Area |

References

- Stuart, K.V.; de Vries, V.A.; Schuster, A.K.; Yu, Y.; van der Heide, F.C.T.; Delcourt, C.; Cougnard-Grégoire, A.; Schweitzer, C.; Brandl, C.; Zimmerman, M.E.; et al. Prevalence of Glaucoma in Europe and Projections to 2050: Findings from the European Eye Epidemiology Consortium. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedde, S.J.; Vinod, K.; Wright, M.M.; Muir, K.W.; Lind, J.T.; Chen, P.P.; Li, T.; Mansberger, S.L. American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Glaucoma Committee: Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 71–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, R.N.; Aung, T.; Medeiros, F.A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1901–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMonnies, C.W. Glaucoma history and risk factors. J. Optom. 2017, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Kuldeep, K.; Tyagi, M.; Sharma, P.D.; Kumar, Y. Glaucoma drainage devices. J. Clin. Ophthalmol. Res. 2013, 1, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SooHoo, J.R.; Seibold, L.K.; Radcliffe, N.M.; Kahook, M.Y. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: Current implants and future innovations. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 49, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, C.; Batras, M.; Iliescu, D.A.; Timaru, C.M.; de Simone, A.; Hosseini-Ramhormozi, J. Current options for surgical treatment of glaucoma. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 59, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ang, B.C.H.; Lim, S.Y.; Betzler, B.K.; Wong, H.J.; Stewart, M.W.; Dorairaj, S. Recent advancements in glaucoma surgery—A review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.H.; Yen, W.T.; Lu, D.W. Advances in glaucoma diagnosis and treatment: Integrating innovations for enhanced patient outcomes. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, D.J.; Sheridan, C.M.; D’Sa, R.A.; Willoughby, C.E.; Bosworth, L.A. Exploiting biomaterial approaches to manufacture an artificial trabecular meshwork: A progress report. Biomater. Biosyst. 2021, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, M.; Court, M.; Xu, H.; Stroder, M.; Webel, A.D. Biomaterials for glaucoma surgery. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 2023, 11, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klézlová, A.; Bulíř, P.; Klápšťová, A.; Netuková, M.; Šenková, K.; Horáková, J.; Studený, P. Novel biomaterials in glaucoma treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišević, M.; Stanić, R.; Ivanišević, P.; Vuković, A. Albrecht von Graefe (1828–1870) and his contributions to the development of ophthalmology. Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 40, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburn, F.S.; Netland, P.A. The Evolution of Glaucoma Drainage Implants. J. Ophthalmic. Vis. Res. 2018, 13, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, R.H. Sclero-Corneal Trephining in the Operative Treatment of Glaucoma, 2nd ed.; George Pulman & Sons: London, UK, 1914; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Every, S.G.; Molteno, A.C.B.; Bevin, T.H.; Herbinson, P. Long-Term Results of Molteno Implant Insertion in Cases of Neovascular Glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2006, 124, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteno, A.C.B. Glaucoma Drainage Implant. U.S. Patent 4,457,757A, 3 July 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Molteno, A.C.B. Implant for Drainage of Aqueous Humour. U.S. Patent 4,750,901, 14 June 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Molteno Ophthalmic Ltd. Glaucoma Drainage Implant System. U.S. Patent 7,776,002 B2, 17 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, R.P.; Reynolds, A.; Emond, M.J.; Barlow, W.E.; Leen, M.M. Long-term survival of Molteno glaucoma drainage devices. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupin, T. Device and Method For Controlling Intraocular Fluid Pressure. U.S. Patent 5,454,796, 3 October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krupin, T.; Podos, S.M.; Becker, B.; Newkirk, J.B.l. Valve implants in filtering surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1976, 81, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropasqua, L.; Carpineto, P.; Ciancaglini, M.; Zuppardi, E. Long-Term Results of Krupin-Denver Valve Implants in Filtering Surgery for Neovascular Glaucoma. Ophthalmologica 1996, 210, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyala, R.S.; Michelini-Norris, B.; Flores, A.; Haller, E.; Margo, C.E. Comparison of different biomaterials for glaucoma drainage devices: Part 2. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schocket, S.S.; Lakhanpal, V.; Richards, R.D. Anterior Chamber Tube Shunt to an Encircling Band in the Treatment of Neovascular Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1982, 89, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.P.; Cantor, L.; Katz, L.J.; Schmid, C.M.; Steinmann, W.C.; Allee, S. Aqueous shunts. Molteno versus Schocket. Ophthalmology 1992, 99, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerveldt, G.; Blake, L.W.; Wright, G.M. Glaucoma Implant. U.S. Patent 5,558,629, 24 September 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, E.M.; Parrish, R.K., 2nd. Plain film imaging of Baerveldt glaucoma drainage implants. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 935–937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Budenz, D.L.; Feuer, W.J.; Barton, K.; Schiffman, J.; Costa, V.P.; Godfrey, D.G.; Buys, Y.M. Postoperative Complications in the Ahmed Baerveldt Comparison Study During Five Years of Follow-up. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 163, 75–82.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stay, M.S.; Pan, T.; Brown, J.D.; Ziaie, B.; Barocas, V.H. Thin-film coupled fluid-solid analysis of flow through the Ahmed glaucoma drainage device. J. Biomech. Eng. 2005, 127, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.A. Device for Treating Glaucoma & Method of Manufacture. U.S. Patent 7,025,740 B2, 11 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- New World Medical. Ahmed Clearpath. 2025. Available online: https://www.newworldmedical.com/ahmed-clearpath/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Arikan, G.; Gunenc, U. Ahmed Glaucoma Valve Implantation to Reduce Intraocular Pressure: Updated Perspectives. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 17, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcon. EXPRESS MINI GLA SHUNT P50PL. 2025. Available online: https://www.alconnordicsurgicalproducts.com/node/1051 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Nicolai, M.; Franceschi, A.; Pelliccioni, P.; Pirani, V.; Mariotti, C. EX-PRESS Glaucoma Filtration Device: Management of Complications. Vision 2020, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, C.; Dahan, E.; Nicolai, M.; Levitz, L.; Bouee, S. Long-term outcomes and risk factors for failure with the EX-press glaucoma drainage device. Eye 2014, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.G.; Brown, R.H.; Smeets, G. Dual Drainage Pathway Shunt Device. U.S. Patent 2010/0234791 A1, 16 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, B.; Huchzermeyer, C.; Rejdak, R.; Reulbach, U.; Dietlein, T.; Hohberger, B.; Jünemann, A. Eyepass Glaucoma Implant in Open-Angle Glaucoma After Failed Conventional Medical Therapy: Clinical Results of a 5-Year-Follow-up. J. Glaucoma 2017, 26, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind Eye Care System. 2025. Available online: https://aravind.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Sisodia, V.P.S.; Krishnamurthy, R. Aurolab Aqueous Drainage Implant (AADI): Review of Indications, Mechanism, Surgical Technique, Outcomes, Impact and Limitations. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 37, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, T.K.P.; Barton, K.; Khor, E.; Sng, C.C.A. Ocular Drainage Device and Method of Manufacturing Thereof. U.S. Patent 9,808,374 B2, 7 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carlà, M.M.; Gambini, G.; Boselli, F.; Hu, L.; Perugini, A.M.; Crincoli, E.; Catania, F.; De Luca, L.; Rizzo, S. The Paul Glaucoma Implant: A systematic review of safety, efficacy, and emerging applications. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2025, 263, 2447–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanna, F.N.; Susanna, B.N.; Susanna, C.N.; Nicolela, M.T.; Susanna, R., Jr. Efficacy and Safety of the Susanna Glaucoma Drainage Device After 1 Year of Follow-up. J. Glaucoma 2021, 30, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biteli, L.G.; Prata, T.S.; Gracitelli, C.P.B.; Kanadani, F.N.; Boas, F.V.; Hatanaka, M.; Paranhos, A., Jr. Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of the New Susanna Glaucoma Drainage Device in Refractory Glaucomas: Short-term Results. J. Glaucoma 2017, 26, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigon, A.; Shaarawy, T. The Suprachoroidal Route in Glaucoma Surgery. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2016, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, G. Shunt for the Treatment of Glaucoma. U.S. Patent 7,207,965 B2, 24 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed, S.; Ben Simon, G.J.; Goldenfeld, M.; Simon, G. Efficacy and safety of gold micro shunt implantation to the supraciliary space in patients with glaucoma: A pilot study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figus, M.; Loiudice, P.; Passani, A.; Perciballi, L.; Agnifili, L.; Nardi, M.; Posarelli, C. Long-term outcome of supraciliary gold micro shunt in refractory glaucoma. Acta. Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, B.; Warner, N.F.; Warner, S.; Shields, B.; Battle, J.F. Uveoscleral Drainage Device. U.S. Patent 2011/0105986 A1, 5 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kammer, J.A.; Mundy, K.M. Suprachoroidal devices in glaucoma surgery. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 22, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Juan, E., Jr.; Boyd, S.; Deem, M.E.; Gifford, H.S., III; Rosenman, D. Glaucoma Treatment Device. U.S. Patent 8,734,378 B2, 27 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vold, S.; Ahmed, I.I.K.; Craven, E.R.; Mattox, C.; Stamper, R.; Packer, M.; Brown, R.H.; Ianchulev, T. Two-year COMPASS trial results: Supraciliary microstenting with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma and cataracts. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2103–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, G.; Clifford, B.; Vold, S.; He, J.; Hamilton, C.; Dickerson, J.; Lane, S. Safety and Effectiveness of CyPass Supraciliary Micro-Stent in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: 5-Year Results from the COMPASS XT Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 208, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, J.H.; Benetz, B.A.; He, J.; Hamilton, C.; Tress, M.V.; Dickerson, J.; Lane, S. Corneal Endothelial Cell Loss and Morphometric Changes 5 Years after Phacoemulsification with or without CyPass Micro-Stent. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 208, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saheb, H.; Ahmed, I.I. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery: Current perspectives and future directions. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2012, 23, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.L.; Samuelson, T.W. iStent: Trabecular Micro-Bypass Stent; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, D.S.; Gille, H.K.; Kalina, C.R., Jr.; Cogger, J.J. Glaucoma Treatment Device. U.S. Patent 9,173,775 B2, 3 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Glaukos Corporation. iStent Inject® W. Available online: https://www.glaukos.com/glaucoma/products/istent-inject-w/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Popovic, M.; Campos-Moller, X.; Saheb, H.; Ahmed, I.I.K. Efficacy and Adverse Event Profile of the iStent and iStent Inject Trabecular Micro-bypass for Open-angle Glaucoma: A Meta-analysis. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2018, 12, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, T.S.; Charles, L.E. Glaucoma Treatment Method. U.S. Patent 8,414,518 B2, 9 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Samet, S.; Ong, J.A.; Ahmed, I.I.K. Hydrus microstent implantation for surgical management of glaucoma: A review of design, efficacy and safety. Eye Vis. 2019, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, T.W.; Chang, D.F.; Marquis, R.; Flowers, B.; Lim, K.S.; Ahmed, I.I.K.; Jampel, H.D.; Aung, T.; Crandall, A.S.; Singh, K.; et al. A Schlemm Canal Microstent for Intraocular Pressure Reduction in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma and Cataract: The HORIZON Study. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InnFocus, LLC. Glaucoma Implant Device. U.S. Patent 7,431,709 B2, 7 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pinchuk, L.; Riss, I.; Batlle, J.F.; Kato, Y.P.; Martin, J.B.; Arrieta, E.; Palmberg, P.; Parrish, R.K., 2nd; Weber, B.A.; Kwon, Y.; et al. The development of a micro-shunt made from poly(styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) to treat glaucoma. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2017, 105, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadruddin, O.; Pinchuk, L.; Angeles, R.; Palmberg, P. Ab externo implantation of the MicroShunt, a poly (styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) surgical device for the treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma: A review. Eye Vis. 2019, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarz Barberá, M.; Martínez-Galdón, F.; Caballero-Magro, E.; Rodríguez-Piñero, M.; Tañá-Rivero, P. Efficacy and Safety of the Preserflo Microshunt With Mitomycin C for the Treatment of Open Angle Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2022, 31, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, C.; Romoda, L.O. Methods for Deploying Intraocular Shunt from a Deployment Device and into an Eye. U.S. Patent 8,663,303 B2, 4 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.Y.; Betzler, B.K.; Yip, L.W.L.; Dorairaj, S.; Ang, B.C.H. Standalone XEN45 Gel Stent implantation in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2022, 67, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, D.Y.; O’Keefe, D.; Badawi, P. Ocular Delivery Systems and Methods. U.S. Patent 8,894,603 B2, 25 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, L.; Cotliar, J.; Vold, S.; Selvadurai, D.; Campbell, A.; Ferreira, G.; Aminlari, A.; Cho, A.; Heersink, S.; Hochman, M.; et al. Canaloplasty and trabeculotomy ab interno with the OMNI system combined with cataract surgery in open-angle glaucoma: 12-month outcomes from the ROMEO study. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2021, 47, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, B.K.; Vold, S.D.; Campbell, A.; Hirsch, L.; Selvadurai, D.; Aminlari, A.E.; Cotliar, J.; Dickerson, J.E. Canaloplasty and Trabeculotomy with the OMNI System in Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma: Two-Year Results from the ROMEO Study. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 17, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianchulev, T. Implantable Biologic Stent and System for Biologic Material Shaping, Preparation, and Intraocular Stenting for Increased Aqueous Outflow and Lowering Intraocular Pressure. U.S. Patent 12,257,188 B2, 25 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, K.; Flowers, B.; Patterson, M.; Vera, L.; Ianchulev, T.; Ahmed, I.I. Bio-interventional uveoscleral outflow enhancement in patients with medically uncontrolled primary open-angle glaucoma: 1-year results of allograft-reinforced cyclodialysis. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2025, 17, 25158414251362010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, D.; Beaulieu, R.H.; Buxton, S.; Ianchulev, T.; Nelsen, D. Methods and Devices for Increasing Aqueous Drainage of the Eye. U.S. Patent 2025/0169989 A1, 29 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, J. Iantrek Announces First Commercial Cases of C.Rex Micro-Interventional System. Optometry Times, 4 February 2025. Available online: https://www.optometrytimes.com/view/iantrek-announces-first-commercial-cases-of-c-rex-micro-interventional-system (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K.; Wong, T.W. Chitosan and its application as tissue engineering scaffolds. In Nanotechnology Applications for Tissue Engineering; Thomas, S., Grohens, Y., Ninan, N., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Qin, G.; Li, X.; Lv, H.; Qian, Z.; Yu, L. The PEG-PCL-PEG Hydrogel as an Implanted Ophthalmic Delivery System after Glaucoma Filtration Surgery; a Pilot Study. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. 2014, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fea, A.M.; Novarese, C.; Caselgrandi, P.; Boscia, G. Glaucoma Treatment and Hydrogel: Current Insights and State of the Art. Gels 2022, 8, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allyn, M.M.; Luo, R.H.; Hellwarth, E.B.; Swindle-Reilly, K.E. Considerations for polymers used in ocular drug delivery. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 787644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boia, R.; Dias, P.A.N.; Martins, J.M.; Galindo-Romero, C.; Aires, I.D.; Vidal-Sanz, M.; Agudo-Barriuso, M.; de Sousa, H.C.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Braga, M.E.M.; et al. Porous poly(ε-caprolactone) implants: A novel strategy for efficient intraocular drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2019, 316, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borandeh, S.; Alimardani, V.; Abolmaali, S.S.; Seppälä, J. Graphene Family Nanomaterials in Ocular Applications: Physicochemical Properties and Toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 1386–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, M.; Li, Y.; et al. A novel deployable microstent for the treatment of glaucoma. Innovation 2025, 6, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, S.R.; Gniesmer, S.; Gapeeva, A.; Offermann, K.J.; Adelung, R.; Mishra, Y.K.; Cojocaru, A.; Kaps, S.; Grisanti, S.; Grisanti, S.; et al. In Vitro Evaluation of Zinc Oxide Tetrapods as a New Material Component for Glaucoma Implants. Life 2022, 12, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Xie, L.; Pan, F.S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, Y.R.; Hutnik, C.M. A feasibility study of using biodegradable magnesium alloy in glaucoma drainage device. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaeili, A.; Rahmani, S.; Hassanpour, K.; Meshksar, A.; Ansari, I.; Afsar-Aski, S.; Einollahi, B.; Pakravan, M. A new glaucoma drainage implant with the use of Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). A pilot study. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 65, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra, A.; Saravia, M.J.; Gurman, P.; Auciello, O. Science and Technology of Ultrananocrystalline Diamond (UNCD) Coatings for Glaucoma Treatment Devices. In Ultrananocrystalline Diamond Coatings for Next-Generation High-Tech and Medical Devices; Auciello, O., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, B.; Shah, J.V.; Cox, A.; Simón, G.; Irazoqui, P. Parylene-C Microbore Tubing: A Simpler Shunt for Reducing Intraocular Pressure. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 69, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, I.C.; Bartels, P.A.; Bertens, C.J.; Söntjens, S.H.; Wyss, H.M.; Schenning, A.P.; Dankers, P.Y.; Beckers, H.J.; den Toonder, J.M. A New Polymeric Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Implant. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2301686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Pandav, S.S.; Kaushik, S.; Nada, R.; Gautam, N.; Kaur, S.; Thattaruthody, F. Biodegradable material for glaucoma drainage devices—A pilot study in rabbits. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]