Abstract

Purpose: We aim to present a case of disseminated fusariosis that occurred in the setting of immunosuppression and presented with bilateral endogenous endophthalmitis, along with a literature review of Fusarium endophthalmitis, highlighting management strategies. Observation: A 70-year-old male with acute myeloid leukemia who had recently undergone a bone marrow transplant noted bilateral floaters and decreased vision. He was found to have bilateral Fusarium endophthalmitis, with subsequent evidence of fungemia and fusariosis in his skin and joints. Despite aggressive local and systemic treatment, he succumbed to the disease. Endophthalmitis was initially stabilized with pars plana vitrectomy and intravitreal amphotericin and voriconazole until the patient transitioned to comfort measures. A review of 31 cases demonstrates that outcomes are poor and that the disease must be treated aggressively, often both systemically and surgically. Conclusion: This case highlights the recalcitrance of Fusarium bacteremia and Fusarium endophthalmitis.

1. Introduction

Although ubiquitous in the environment as a plant pathogen, Fusarium does not commonly result in systemic fungal infection or enter the eye to cause endophthalmitis [1]. When present, Fusarium endophthalmitis more commonly occurs exogenously after inoculation from trauma, invasion into the eye from keratitis, or after cataract surgery. Often, in these cases, aggressive treatment is required, and prognosis remains poor despite multifaceted local, surgical, and systemic treatment [2,3,4,5]. This report illustrates a case of bilateral endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis in an immunocompromised patient, highlighting the complex multidisciplinary care these rare cases require.

2. Case Report

A 70-year-old male with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented for a mismatched, unrelated donor bone marrow transplant (BMT). He had previously been treated with three cycles of chemotherapy, including two rounds of intrathecal chemotherapy for presumed central nervous system disease. While the central nervous system disease showed improvement, the patient had residual bone marrow involvement.

Despite a hospital course complicated by neutropenic fever, acute pulmonary edema, new-onset atrial fibrillation, and clostridium difficile colonization, his bone marrow transplant team felt optimistic one month after his BMT that his immune system was recovering and that his disease may have been cured. Throughout this first month after BMT, he was on antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal agents for prophylaxis: oral levofloxacin for neutropenic fever, oral acyclovir for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV), oral letermovir for cytomegalovirus (CMV), oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, and oral isovuconazole for fungal prophylaxis.

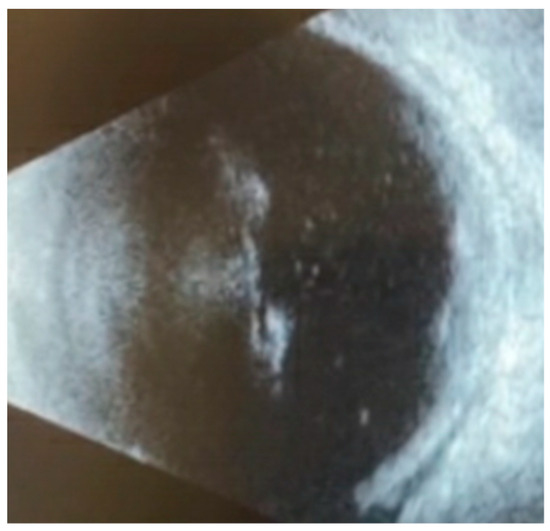

It was at this time, one month following BMT, that the patient noted one week of bilateral floaters and decreased vision. An ophthalmology consult was requested. On exam, his visual acuity was counting fingers from two feet in both eyes with normal intraocular pressures. He had mild temporal conjunctival injection in the left eye but an otherwise normal anterior segment exam. The dilated fundus exam was notable for mild vitreous haze bilaterally, numerous foci of elevated, subretinal lesions, and overlying hemorrhage in the macula of each eye. Ocular ultrasonography (Figure 1) confirmed the presence of subretinal masses and vitreous debris bilaterally, without retinal detachment.

Figure 1.

B-scan ultrasonography of macular lesions in the left eye on initial examination demonstrated vitreous opacities consistent with vitritis, elevated subretinal lesions, and a thickened choroid.

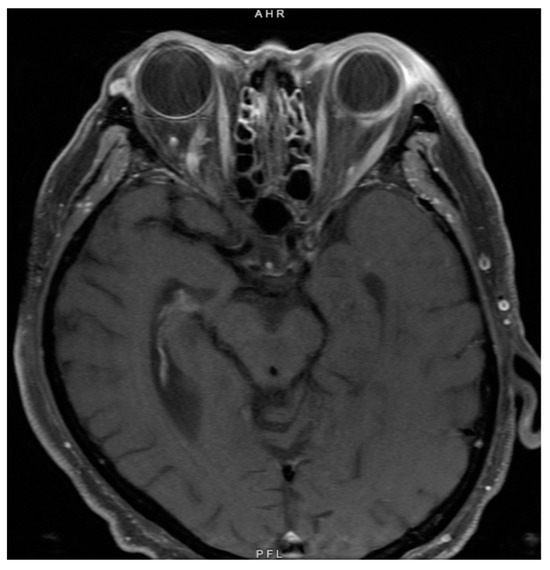

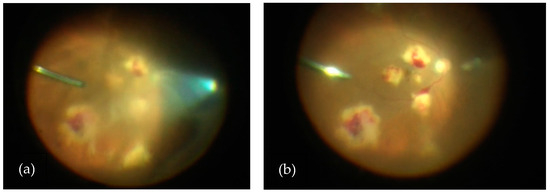

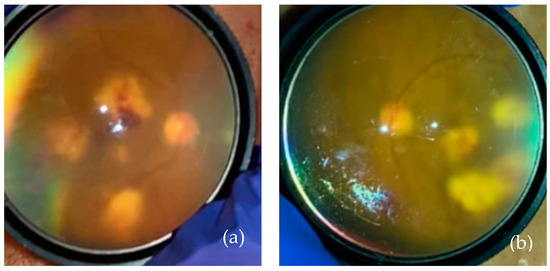

Due to concern for recurrent or widespread malignancy, magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) and a lumbar puncture were performed, neither of which showed evidence of neoplasia. The patient received a vitreous tap and intravitreal injection of voriconazole (100 mg/0.1 mL), vancomycin (1 mg/0.1 mL), and ceftazidime (2.25 mg/0.1 mL) in both eyes. After five days, the culture began to grow fungi, which ultimately speciated as Fusarium solani. A blood culture and diagnostic vitrectomy (Figure 3) similarly yielded Fusarium species. His vision remained intact, able to count fingers from two feet in both eyes afterward (Figure 4). Further examination revealed systemic dissemination with the involvement of his skin and several joints, which similarly grew Fusarium species. From the blood sample, amphotericin B was found to have a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2 micrograms/mL and voriconazole an MIC of 4 mg/mL.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbit at the time of initial diagnosis showed abnormal thickening of the left sclera and periorbital soft tissues but no lesions infiltrating the optic nerve to suggest malignancy.

Figure 3.

(a) View of vitritis and subretinal lesions in the right eye during diagnostic vitrectomy and prior to core vitrectomy. (b) View of subretinal lesions in the right eye during diagnostic vitrectomy and after core vitrectomy.

Figure 4.

(a) Right eye post-operative day 2 after diagnostic vitrectomy of the right eye. (b) The left eye on the same day.

Systemic coverage was initiated with intravenous amphotericin B and voriconazole and, eventually, a novel experimental antifungal, fosmanogepix. Ocular treatment consisted of ten rounds of intravitreal injections every other day with antifungals, alternating between amphotericin B and voriconazole. Examination findings stabilized during treatment, with similar visual acuity and no extension of the lesions. Given extensive systemic disease, the patient ultimately wished to discontinue local treatments and withdrew care, succumbing to his disease process.

3. Discussion

Even with aggressive systemic and local therapy, fungal endophthalmitis can be a devastating disease with a poor visual prognosis. Fungal endophthalmitis more often occurs exogenously after trauma, keratitis, or intraocular surgery; endogenous endophthalmitis associated with systemic fungal infection represent 2–15% of all cases [6]. The most common organisms found in endogenous fungal endophthalmitis are Candida albicans and Aspergillus species [7]. Here, we present a case of bilateral endogenous fungal endophthalmitis caused by Fusarium solani, which is a rare presentation with isolated case reports in the literature, as summarized below.

4. Literature Review

Twelve species of Fusarium have been reported to be associated with systemic infection, of which the most common are Fusarium solani (~50% of cases), Fusarium oxysporum (~20% of cases), Fusarium verticillioidis (~10% of cases) and Fusarium monoliforme (~10% of cases) [1]. When associated with ocular infection, Fusarium species are more often associated with keratitis and exogenous endophthalmitis [1,6].

A literature review was conducted on April 10, 2024, on PubMed using the keywords “fusarium endophthalmitis” and “endogenous fusarium endophthalmitis.” All cases of endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis referred to in these articles were also included. Several larger case series reported exogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis, while a limited number of case reports associated with endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis were found (n = 30, not including the case reported here). Prior to this review, the largest case series included 14 cases [8], so this is the most comprehensive literature review to our knowledge to date. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Most endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis occurred in the setting of an immunocompromised state. Including our patient, AML (n = 13/31) and acute lymphocytic leukemia (n = 8/31) were the most commonly associated medical comorbidities. Other identified medical risk factors included immunosuppression from Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 1/31) [9], the use of systemic steroids (n = 3/31) [8,10,11], diabetes (n = 2/31) [8,10], Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS, n = 1/31) [12], and a history of liver transplantation (n = 1/31) [13]. Aside from the presented case, one other patient (n = 2/31) had undergone a bone marrow transplant [14], while one had undergone a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (n = 1/31) [15]. One case for each was reported where the only identifiable medical history was intravenous drug use [16], preceding kidney infection [17], or a recent thorn prick with a self-limited local inflammatory reaction [18]. When a species was identified, Fusarium solani (n = 17/31) predominated. Two cases were reported for Fusarium dimerum [16,19].

Treatment options for fungal endophthalmitis include topical natamycin (though not often used alone), intravitreal injections of antifungals such as amphotericin B (5–10 µg/0.1 mL) and voriconazole (1 mg/0.1 mL), systemic oral or intravenous antifungal treatment with amphotericin B, and surgical treatment with pars plana vitrectomy (n = 17/31) or the removal of other infected areas (e.g., lensectomy) (n = 4/31) and in recalcitrant cases, evisceration or enucleation (n = 7/31). Almost all authors used systemic amphotericin (n = 24/31) and/or an azole (n = 14/31) such as voriconazole (most common, n = 12), fluconazole (n = 1), or itraconazole (n = 1). Intravitreal injections of amphotericin only (n = 10/31), vorizonacole only (n = 6/31), or an alternating combination of amphotericin and voriconazole (n = 6/31) were given at most, simultaneously and once weekly, up to 6 weeks [20] (aside from the reported case). Seven cases received systemic therapy without intravitreal injections, with one of these patients undergoing pars plana vitrectomy and one requiring enucleation. No well-studied regimen exists to guide treatment selection, and most cases used combination therapy. Vitrectomy provides the advantage of reducing the fungal burden in the vitreous and provides additional samples for establishing the diagnosis, as well as addressing common post-infectious sequelae such as retinal detachment and epiretinal membrane [21]. In one case of fungal endophthalmitis (not specified to be Fusarium), the intralesional injection of voriconazole and povidone-iodine was performed with final vision at 20/25 [22].

Systemic outcome and final vision varied without a consistent pattern. Two cases had patients that ultimately recovered to 20/20 visual acuity; both of these cases involved only the eye and suggested the importance of immune recovery and treatment with vitrectomy, systemic amphotericin B, and intravitreal injections of antifungals [16,20]. Overall, this literature review suggests the need for aggressive treatment and a surgical reduction in disease burden, but no conclusion can be drawn about the most effective treatment nor about systemic and ocular prognosis upon diagnosis. Only three patients had final visual acuities between 20/50 and 20/80, while most patients experienced near or total vision loss of the affected eyes [8,17,23]. Multi-system Fusarium involvement (n = 21/31) resulted in both survival (n = 11 of 24 with reported systemic outcomes) and death (n = 13 of 24 with reported systemic outcomes), likely in part related to factors involved in the course of their systemic disease.

Table 1.

Summary of case reports in the literature.

Table 1.

Summary of case reports in the literature.

| Reference | No. of Patients | Age (Years) | Gender | Medical History | Antifungals Prior to Ocular Symptoms | Involved Sites | Fusarium species | Treatment | Ocular Surgery | Ocular Outcome | Final Vision | Systemic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiribelli et al. 2002 [24] | 1 | 31 | Male | AML | Itraconazole | Skin, lungs, eye, meninges | F. solani | Systemic: AmB | Vitrectomy Iridectomy PK | No response | Total vision loss | Death from hemorrhagic shock |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Rezai et al. 2005 [25] | 1 | 70 | Female | AML | NA | Skin, blood, eye | NA | Systemic: AmB | None | No response | - | Death from multiorgan failure |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Cudillo et al. 2006 [26] | 1 | 34 | Male | ALL | Itraconazole | Skin, blood, lungs, sinuses, eye | NA | Systemic: AmB | None | Response | - | Death from leukemia relapse |

| Thachil et al. 2010 [15] | 1 | 67 | Female | AML | NA | Skin, blood, eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Vitrectomy | Response | HM | Survival |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Kapp et al. 2011 [27] | 1 | 69 | Male | AML, HSCT | Posaconazole | Blood, kidneys, eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Vitrectomy | No response | Worse than HM | Death from multiorgan failure |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Kah et al. 2011 [23] | 1 | 9 | Male | ALL | NA | Skin, blood, eye, kidney abscess, subcutaneous soft tissue | NA | Systemic: AmB cholesterol dispersion | None | Response | VA 6/24 (20/80) | Survival |

| Intraocular: Vori | ||||||||||||

| Perini et al. 2013 [28] | 1 | 68 | Male | AML | NA | Skin, blood, lungs, eye | NA | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Enucleation | No response | - | - |

| Intraocular: Vori | ||||||||||||

| Malavade et al. 2013 [9] | 3 | 62 | Male | Hodgkin lymphoma | Fluconazole | Skin, eye | NA | Systemic: itraconazole, AmB | Vitrectomy | No response | - | Death from refractory leukemia |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Topical: AmB | ||||||||||||

| 66 | Male | AML | AmB + Vori | Skin, bone, eye | NA | Systemic: AmB, Vori | Vitrectomy | No response | - | - | ||

| Intraocular: AmB, Vori | RD repair Enucleation | |||||||||||

| 46 | Male | ALL | Vori | Skin, sinus, eye | NA | Systemic: Vori, AmB, co-trimoxazole | None | NA | - | - | ||

| Jørgensen et al. 2014 [13] | 1 | 56 | Female | Liver transplant x 2 | Micafungin | Eye | F. solani | Systemic: Micafungin, Vori after enucleation | Enucleation | NA | - | Death from septic shock |

| Intraocular: Vori for contralateral eye | ||||||||||||

| Bui & Carvounis 2016 [20] | 1 | 14 | Female | ALL | NA | Eye | NA | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Vitrectomy | Response | VA 20/20 | Survival |

| Intraocular: AmB, Vori | ||||||||||||

| Ocampo-Garza et al. 2016 [29] | 1 | 46 | Male | ALL | NA | Skin, lungs, eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori, AmB | None | No response | Total vision loss | Survival, undergoing continued chemotherapy |

| Topical: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Balamurugan and Khodifad 2016 [10] | 1 | 46 | Male | Diabetes mellitus, topical and oral steroids for uveitis treatment | NA | Eye | NA | Systemic: antifungal not specified | Vitrectomy | No response | HM | - |

| Intraocular: Vori | ||||||||||||

| Rizzello et al. 2018 [8] | 1 | 59 | Female | ALL, Diabetes mellitus in setting of prolonged steroid use | Posaconazole | Skin, blood, eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Vitrectomy Lensectomy | Response | VA +0.50 logMAR (20/63) | Survival in ALL remission |

| Intraocular: Vori | ||||||||||||

| Topical: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Glasgow et al. 1996 [12] | 1 | 51 | Male | AIDS, cytomegalovirus retinitis | Ganciclovir | Blood, brain, lung, kidney, thyroid, lymph nodes, eye | F. solani | Systemic: AmB, fluconazole | None | No response | - | Death |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Patel et al. 1994 [30] | 1 | 31 | Female | ALL | NA | Skin, eye | NA | Systemic: AmB, 5-FC | None | No response | Progressive vision loss | Death from bronchopneumonia and multiorgan failure |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Topical: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Cho et al. 1973 [31] | 1 | 2.5 | Male | ALL | None | Skin, knee, eye | F. solani | Systemic: AmB | None | Response | - | Death |

| Topical: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Simon et al. 2018 [19] | 1 | 71 | Female | AML | Posaconazole | Eye | F. dimerum | Systemic: Vori | Vitrectomy | Response | HM | Survival, undergoing continued chemotherapy |

| Intraocular: AmB, Vori | ||||||||||||

| Topical: Vori | ||||||||||||

| Milligan et al. 2016 [18] | 1 | 32 | Female | None; recent thorn prick with self-limited local inflammatory | None | Eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori | Vitrectomy | No response | CF | Survival |

| Intraocular: AmB, Vori | RD repair with silicone oil | |||||||||||

| Yoshida et al. 2018 [32] | 1 | 16 | Male | AML | NA | Lung, spleen, subcutaneous soft tissue, eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Vitrectomy | Response | VA 20/400 | Survival |

| Intraocular: Vori | Tractional RD repair | |||||||||||

| Gabriele and Hutchins. 1996 [16] | 1 | 30 | Male | Intravenous drug use | NA | Eye | F. dimerum | Systemic: AmB | Vitrectomy | Response | VA 20/20 | Survival |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Baysal et al. 2018 [33] | 1 | 28 | Male | AML | Posaconazole | Eye | NA | Systemic: Vori, AmB | Enucleation | NA | - | Death from pneumosepsis |

| Voriconazole | ||||||||||||

| Relimpio-López et al. 2018 [34] | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Eye | F. solani | NA | Lensectomy | No response | - | NA |

| PK | ||||||||||||

| Evisceration | ||||||||||||

| NA | NA | NA | NA | Eye | F. solani | Systemic: Vori | Vitrectomy | Response | HM (aphakic) | NA | ||

| Intraocular: AmB, Vori | PK | |||||||||||

| Topical: AmB, fortified Vori, Povidone-Iodine | ||||||||||||

| Lieberman et al. 1979 [11] | 1 | 45 | Female | Uveitis treated with oral prednisone 60–120 mg daily | NA | Eye | F. solani | None | Sector iridectomy Lensectomy Enucleation | No response | - | NA |

| Comhaire-Poutchinian et al. 1990 [17] | 1 | 27 | Female | Recent kidney infection | Itraconazole | Kidney, skin, eye | NA | Systemic: AmB, 5-FC | Vitrectomy | Response | VA 4/10 (20/50) | Survival |

| Venditti et al. 1988 [35] | 1 | 55 | Male | AML | NA | Skin, blood, eye | F. solani | Systemic: AmB, 5-FC | None | No response | Total vision loss | Death |

| Robertson et al. 1991 [14] | 1 | 33 | Male | AML, BMT | NA | Skin, eye, toe | F. solani | Systemic: AmB | Vitrectomy | No response | - | Survival free of leukemia and fungal disease |

| Intraocular: AmB | Enucleation | |||||||||||

| Louie et al. 1994 [36] | 1 | 67 | Male | AML | Fluconazole | Blood, eye | F. solani | Systemic: AmB | Vitrectomy | Response | VA 4/200 (20/1000) | Death from recurrent leukemia |

| Intraocular: AmB | ||||||||||||

| Topical: None | ||||||||||||

| Present Case | 1 | 70 | Male | AML, BMT | isovuconazole | Skin, blood, joints, eye | F. solani | Systemic: AmB | Vitrectomy | No response | CF at 2-3′ | Death from complications of treatment |

| Intraocular: AmB, Vori | ||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 31 |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AmB, Amphotericin B; 5-FC, 5-fluorocytosine; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; BMT, bone marrow transplant; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; Vori, voriconazole; NA, not available/applicable; RD, retinal detachment; PK, penetrating keratoplasty.

5. Conclusions

Endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis is rare. When present, it is more likely to occur in the setting of an immunocompromised patient with hematologic malignancy or neutropenia. Aggressive treatment is warranted, and even then, the prognosis for visual recovery remains poor.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft preparation: C.S.Z., C.M.T.D.; Supervision: K.W., E.B.K., E.R., P.M., C.M.T.D.; Writing—review and editing: K.W., E.B.K., E.R., V.B.M., C.M.T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the P30 Vision Research Core Grant, NEI P30-EY026877, and Research to Prevent Blindness. VBM is supported by R01EY024665; CMD is supported by K12 EY033745, The Robert Machemer Foundation, and E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, as this is a retrospective case study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent from the patient’s family was obtained for the publication of this report. This case report does not contain any details or information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Additional acknowledgement goes to the Stanford Department of Ophthalmology, Bone Marrow Transplant, and Infectious Disease residents, fellows, and faculty members who assisted in the care of this patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nucci, M.; Anaissie, E. Fusarium Infections in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun, D.; Fernandez, V.; Miller, D.; Alfonso, E.C. Advanced Fusarium Keratitis Progressing to Endophthalmitis. Cornea 2003, 22, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Shah, S.; Garg, A.; Gandhi, A.; Kumar, B. Fusarium Causing Recalcitrant Post-operative endophthalmitis-Report of a Case with Review of Literature. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arasaki, R.; Tanaka, S.; Okawa, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Inoue, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Ito, A.; Maruyama-Inoue, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Muraosa, Y.; et al. Endophthalmitis outbreak caused by Fusarium oxysporum after cataract surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2022, 26, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, M.; Lee, S.J.; Shin, J.P.; Kim, J.G.; Kang, S.W.; Park, K.H.; for the Korean Retina Society Members. An Outbreak of Fungal Endophthalmitis After Cataract Surgery in South Korea. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023, 141, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhablani, J. Fungal Endophthalmitis. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essman, T.F.; Flynn, H.W.; Smiddy, W.E.; Brod, R.D.; Murray, T.G.; Davis, J.L.; Rubsamen, P.E. Treatment Outcomes in a 10-year Study of Endogenous Fungal Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers 1997, 28, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, I.; Castagnetti, F.; Toschi, P.G.; Bertaccini, P.; Primavera, L.; Paolucci, M.; Faccioli, L.; Spinardi, L.; Lewis, R.; Cavo, M.; et al. Successful Treatment of Bilateral Endogenous Fusarium solani Endophthalmitis in a Patient with Acute Lymphocytic Leukaemia. Mycoses 2018, 61, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malavade, S.S.; Mai, M.; Pavan, P.; Nasr, G.; Sandin, R.; Greene, J. Endogenous Fusarium Endophthalmitis in Hematologic Malignancy: Short Case Series and Review of Literature. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2013, 21, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, S.; Khodifad, A. Endogenous Fusarium Endophthalmitis in Diabetes Mellitus. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2016, 2016, e6736413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, T.W.; Ferry, A.P.; Bottone, E.J. Fusarium Solani Endophthalmitis without Primary Corneal Involvement. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1979, 88, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, B.J.; Engstrom, R.E., Jr.; Holland, G.N.; Kreiger, A.E.; Wool, M.G. Bilateral Endogenous Fusarium Endophthalmitis Associated with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1996, 114, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, J.S.; Prause, J.U.; Kiilgaard, J.F. Bilateral Endogenous Fusarium solani Endophthalmitis in a Liver-Transplanted Patient: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2014, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.J.; Socinski, M.A.; Soiffer, R.J.; Finberg, R.W.; Wilson, C.; Anderson, K.C.; Bosserman, L.; Sang, D.N.; Salkin, I.F.; Ritz, J. Successful Treatment of Disseminated Fusarium Infection After Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1991, 8, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Thachil, J.; Mohandas, K.; Sebastian, R.T. Successful Treatment of Disseminated Fusariosis with Ocular Involvement After Chemotherapy for Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2010, 18, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, P.; Hutchins, R.K. Fusarium Endophthalmitis in an Intravenous Drug Abuser. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 122, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comhaire-Poutchinian, Y.; Berthe-Bonnet, S.; Grek, V.; Cremer, V. Endophthalmitis due to Fusarium: An Uncommon Cause. Bull. Soc. Belg. Ophtalmol. 1990, 239, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, A.L.; Gruener, A.M.; Milligan, I.D.; O’Hara, G.A.; Stanford, M.R. Isolated endogenous Fusarium endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent adult after a thorn prick to the hand. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2016, 6, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.; Gastaud, L.; Martiano, D.; Bailleux, C.; Hasseine, L.; Gari-Toussaint, M. First Endogenous Fungal Endophthalmitis due to Fusarium Dimerum: A Severe Eye Infection Contracted During Induction Chemotherapy for Acute Leukemia. J. Mycol. Médicale 2018, 28, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.K.; Carvounis, P.E. Favorable Outcomes of Filamentous Fungal Endophthalmitis Following Aggressive Management. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 32, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, Y.E.; Eliott, D. The Role of Vitrectomy in the Management of Fungal Endophthalmitis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 32, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbin, B.; Guest, J.M.; Lin, X. Recalcitrant Fusarium Fungal Endophthalmitis: Novel Surgical Technique Combining Vitrectomy with Intralesional Injection of Voriconazole and Povidone Iodine. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2022, 16, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kah, T.A.; Yong, K.C.; Rahman, R.A. Disseminated fusariosis and endogenous fungal endophthalmitis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia following platelet transfusion possibly due to transfusion-related immunomodulation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2011, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiribelli, M.; Zaja, F.; Filì, C.; Michelutti, T.; Prosdocimo, S.; Candoni, A.; Fanin, R. Endogenous endophthalmitis following disseminated fungemia due to Fusarium solani in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2002, 68, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezai, K.A.; Eliott, D.; Plous, O.; Vazquez, J.A.; Abrams, G.W. Disseminated Fusarium Infection Presenting as Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis in a Patient with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2005, 123, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cudillo, L.; Tendas, A.; Picardi, A.; Dentamaro, T.; Del Principe, M.I.; Amadori, S.; de Fabritiis, P. Successful treatment of disseminated fusariosis with high dose liposomal amphotericin-B in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2006, 85, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapp, M.; Schargus, M.; Deuchert, T.; Springer, J.; Wendel, F.; Loeffler, J.; Grigoleit, G.; Kurzai, O.; Heinz, W.; Einsele, H.; et al. Endophthalmitis as primary clinical manifestation of fatal fusariosis in an allogeneic stem cell recipient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2011, 13, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perini, G.F.; Camargo, L.F.A.; Lottenberg, C.L.; Hamerschlak, N. Disseminated fusariosis with endophthalmitis in a patient with hematologic malignancy. Einstein 2013, 11, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocampo-Garza, J.; Herz-Ruelas, M.; Chavez-Alvarez, S.; Gómez-Flores, M.; Vera-Cabrera, L.; Welsh-Lozano, O.; Gallardo-Rocha, A.; Escalante-Fuentes, W.; Ocampo-Candiani, J. Disseminated fusariosis with endophthalmitis after skin trauma in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, e121–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.S.; Hemady, R.K.; Rodrigues, M.; Rajagopalan, S.; Elman, M.J. Endogenous Fusarium Endophthalmitis in a Patient with Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1994, 117, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.T.; Vats, T.S.; Lowman, J.T.; Brandsberg, J.W.; Tosh, F.E. Fusarium Solani Infection During Treatment for Acute Leukemia. J. Pediatr. 1973, 83, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Kiyota, N.; Maruyama, K.; Kunikata, H.; Toyokawa, M.; Hagiwara, S.; Makimura, K.; Sato, N.; Taniuchi, S.; Nakazawa, T. Endogenous Fusarium Endophthalmitis During Treatment for Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Successfully Treated with 25-Gauge Vitrectomy and Antifungal Medications. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, M.; Umit, E.; Boz, İ.B.; Kırkızlar, O.; Demir, M. Fusarium Endophthalmitis, Unusual and Challenging Infection in an Acute Leukemia Patient. Case Rep. Hematol. 2018, 2018, 9531484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relimpio-López, M.I.; Gessa-Sorroche, M.; Garrido-Hermosilla, A.M.; Díaz-Ruiz, C.; Montero-Iruzubieta, J.; Etxebarría-Ecenarro, J.; Ruiz-Casas, D.; Rodríguez-de-la-Rúa-Franch, E. Extreme Surgical Maneuvers in Fungal Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmologica 2017, 239, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venditti, M.; Micozzi, A.; Gentile, G.; Polonelli, L.; Morace, G.; Bianco, P.; Avvisati, G.; Papa, G.; Martino, P. Invasive Fusarium solani Infections in Patients with Acute Leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1988, 10, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, T.; el Baba, F.; Shulman, M.; Jimenez-Lucho, V. Endogenous Endophthalmitis due to Fusarium: Case Report and Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994, 18, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).