Abstract

Inhaled medications, commonly prescribed for respiratory conditions such as asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, are increasingly scrutinized in sports medicine due to their potential performance-enhancing effects. Bronchodilators, in particular, may improve lung function, increase oxygen delivery, and influence muscle contractility, potentially enhancing athletic performance. However, supratherapeutic use raises concerns about cardiovascular risks, including tachyarrhythmias and altered autonomic balance, as well as muscle hypertrophy and sprint capacity gains. These effects blur the line between therapeutic use and doping, creating challenges for fair competition. This review explores the mechanisms by which inhaled drugs affect the cardiovascular and muscular systems, summarizes notable doping cases, and evaluates current detection methods. Despite regulatory thresholds established by the World Anti-Doping Agency, assay interpretation remains complicated by inter-individual variability, short drug half-lives, and enantiomeric differences. Addressing these gaps requires refined pharmacokinetic modeling, enantioselective assays, and metabolomic fingerprinting to safeguard both athlete health and the integrity of sport.

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Inhaled Medication Use Among Athletes and Prevalence

Inhaled medications, particularly β2-adrenergic agonists and corticosteroids, are commonly used for the management of respiratory conditions such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Asthma is a highly prevalent disease in the general population, affecting about 6.6% of adults, 9.1% among children and 11.0% among adolescents [1]. Although its prevalence is lower in low-income countries compared to high-income countries, the associated burden is more severe [2]. Asthma prevalence is reported to be higher in athletes. Data suggest that up to 50% of endurance athletes report some degree of asthma and EIB [3]. Aquatic and winter-based sporting disciplines are also particularly associated with a higher percentage of athletes suffering from lower airway dysfunction [4,5].

The pathogenesis of EIB in athletes is multifactorial and influenced by sport type, training environment, genetics, and individual susceptibilities. High-intensity exercise often requires predominantly oral breathing, bypassing the natural filter of the upper airways and exposing the lower airways to physical, thermal, and chemical stress. In susceptible individuals, this can trigger airway dysfunction and bronchoconstriction, leading to respiratory symptoms such as cough, wheezing, and dyspnoea [6,7].

For athletes suffering from asthma or EIB, the recommended treatment mirrors that of the general population and is based on inhaled medications, including inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), short-acting beta-agonists (SABA), leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA), and mast cell stabilizers (MCSA) [4,8].

1.2. Potential for Misuse Among Athletes

According to the World Anti-Doping Code, a substance or method is included on the Prohibited List if it meets at least two of the following criteria: it has the potential to enhance sport performance, it represents an actual or potential health risk to the athlete, or its use violates the spirit of sport. Substances or methods that can mask the use of other prohibited substances or methods are also included [9].

While inhaled drugs are therapeutic for managing asthma and EIB, their potential misuse to enhance performance has raised concerns. Inhaled β2-agonists are the most extensively studied: salbutamol, formoterol, and terbutaline are permitted under specific conditions. However, some studies show these substances may enhance muscle strength and sprint performance, suggesting possible ergogenic effects [10,11]. Several high-profile doping cases involving β2-agonists have highlighted the challenge of distinguishing legitimate therapeutic use from potential misuse [12,13,14].

These medications induce bronchodilation, improving airflow and oxygen delivery during exertion, though this effect may be less significant than the direct muscular effects [3]. According to WADA, systemic corticosteroids are prohibited in-competition because of their potential performance-enhancing effects. In contrast, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are permitted both in- and out-of-competition, as evidence for any ergogenic effect is lacking [15].

This has led to debate in the scientific community regarding the thresholds at which therapeutic agents may confer a competitive advantage.

2. Mechanisms of Action of Inhaled Medications

2.1. Bronchodilators

Inhaled bronchodilators are the cornerstone of the symptomatic treatment of several respiratory diseases, particularly asthma, EIB and COPD [16]. They act primarily inducing relaxation of bronchial smooth muscle, thereby relieving airway obstruction and improving airflow. They are classified by mechanism of action and receptor target into β2-adrenoceptor agonists, anticholinergics, and theophylline.

2.1.1. β2-Agonists

They are the ones used most frequently in both asthma and COPD management. Based on their pharmacodynamics, they are classified into Short-Acting Beta Agonists (SABAs) and Long-Acting Beta Agonists (LABAs).

- -

- SABAs: Provide quick relief of symptoms and are typically administered in case of exacerbation, but are not recommended for chronic treatment. Examples include salbutamol and terbutaline [17,18].

- -

- LABAs: Commonly used as maintenance therapy. Examples include formoterol and salmeterol [17].

These drugs activate β2-adrenergic receptors on airway smooth muscle cells. The β2-adrenergic receptor is a G-protein-coupled receptor composed of a heterotrimer (Gαs, Gβ, Gγ). When a β2-agonist binds this receptor, the heterotrimer dissociates into a Gαs monomer and a Gβγ dimer. Gαs undergoes a conformational change and binds to adenylate cyclase, the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), an intracellular second messenger [19].

Elevated cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates downstream targets. One important PKA effect is activation of myosin phosphatase, which dephosphorylates the myosin light chain (MLC). Dephosphorylated MLC cannot bind actin, reducing smooth muscle contraction and leading to relaxation.

Additionally, the Gβγ dimer activates potassium (K+) channels, causing K+ efflux, hyperpolarization, and reduced calcium mobilization, further inhibiting contraction. cAMP also activates Epac, which downregulates Rho and contributes to airway smooth muscle relaxation [20,21].

2.1.2. Anticholinergics

Like β2-agonists, they are classified by duration of action into

- -

- Short-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists (SAMAs): sometimes used with SABAs in acute settings (e.g., ipratropium bromide).

- -

- Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists (LAMAs): such as tiotropium, which is rarely used in asthma but more commonly employed in COPD.

Their mechanism is blocking muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle and mucous glands. M3 receptors are the most relevant on bronchial smooth muscle, but M2 autoreceptor dysfunction and increased M1 activation also contribute to bronchoconstriction, mucus secretion, inflammation, and airway remodeling [22,23].

Blocking acetylcholine reduces contractility by preventing activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) signaling. Normally, PKC inhibits myosin light chain phosphatase, and IP3 triggers Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum. Both mechanisms increase contraction; blocking them promotes relaxation [24].

Combining a LAMA with a LABA offers complementary mechanisms: LAMA blocks parasympathetic-induced constriction, while LABA stimulates β2-receptors to enhance cAMP-mediated relaxation. This dual approach has been shown to improve lung function and reduce exacerbations in chronic respiratory conditions [25].

Although anticholinergic bronchodilators improve airflow and ventilatory capacity, there is currently no convincing evidence that they provide meaningful ergogenic benefits in healthy or athletic populations. Accordingly, anticholinergics are not included on the WADA Prohibited List.

2.1.3. Theophylline

Theophylline is a methilxanthine and a minor metabolite of caffeine, currently used for a variety of respiratory conditions including EIB. Its mechanism of action involves non-selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase, leading to increased intracellular cyclic AMP, as well as antagonism of adenosine receptors, which contributes to bronchodilation and mild central nervous system stimulation [26]. Beyond its respiratory applications, theophylline has been investigated for potential ergogenic properties. Although it is not currently included in the WADA Prohibited List, theophylline was classified as a forbidden substance for several years due to its central nervous system–stimulating properties, for example, by the Flemish Government in 1991. As a methylxanthine structurally related to caffeine, it may enhance physical performance through adenosine receptor antagonism, leading to increased alertness, reduced perception of effort, and improved ventilatory efficiency. Evidence indicates that theophylline can exert mild performance-enhancing effects, particularly in endurance-based activities, though the studies results are inconsistent contradicting results and/or insufficient data [27].

2.2. Corticosteroids and Other Inhaled Drugs

Bronchial asthma is characterized by persistent inflammation even during remission. ICS such as beclomethasone, budesonide, and fluticasone act by reducing airway inflammation, improving airflow, controlling symptoms, and preventing exacerbations [8]. Unlike systemic corticosteroids, ICS have minimal systemic absorption at therapeutic doses, reducing side effects [28]. They are often combined with LABAs or used in triple therapy (LABA/LAMA/ICS) in patients with frequent COPD exacerbations or hyper-eosinophilia, and in asthma uncontrolled by monotherapy. The combination of LABAs and ICS plays a critical role in chronic asthma management, since LABA monotherapy has been associated with loss of effectiveness over time (tachyphylaxis) due to down-regulation or uncoupling of β2-adrenergic receptors on airway smooth muscle and inflammatory cells. ICS contribute to restoring β2-receptor function by increasing receptor expression and reversing agonist-induced desensitization, thereby enhancing the anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator responses of the combination therapy.

Mechanism: ICS bind to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in epithelial and immune cells. The drug–receptor complex translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with glucocorticoid response elements (GREs). This leads to upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes (e.g., lipocortin-1, which inhibits phospholipase A2), and downregulation of pro-inflammatory genes (e.g., IL-4, IL-5, TNF-α, COX-2). Consequences: reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells, decreased mucus production, reduced vascular permeability, and induction of eosinophil apoptosis, limiting fibrosis and airway remodelling [29,30,31].

In patients with asthma, ICS help by suppressing the underlying airway inflammation and reducing hyper-responsiveness, while LABAs act on different pathophysiological pathways, not only by bronchodilation, but also by inhibiting mast cell mediator release, reducing plasma exudation and possibly decreasing sensory nerve activation. Moreover, there are positive molecular interactions: corticosteroids up-regulate β2-receptor gene expression (thus counteracting potential receptor down-regulation from long-term β2-agonist use), and β2-agonists may enhance corticosteroid efficacy by increasing nuclear localization of glucocorticoid receptors and amplifying anti-inflammatory effects [32].

2.3. How These Medications Improve Respiratory Function and Overall Performance

Bronchodilators improve pulmonary function by relaxing smooth muscle via increased cAMP, causing bronchodilation and reduced airflow resistance. This enhances ventilation, oxygen uptake, and CO2 elimination [33]. This condition of improved distribution of airflow throughout the lungs translates into an increase in Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s (FEV1) and Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) relative to baseline, even in non-asthmatic individuals [34]. Also ICS have shown to improve lung function, symptoms, and quality of life and to reduce exacerbations in both COPD and asthma [35]. Consequently, oxygen delivery to the muscles is optimized, which can delay fatigue and improve endurance. This could be particularly helpful during physical exertion when greater skeletal muscle performance is requested, especially during aerobic activities. However, some studies have shown that the positive effect on FEV1 induced by β2-agonists administration, is not accompanied by an increase in aerobic performance outcomes, such as maximum oxygen uptake (VO 2max), time trial performance, time to exhaustion and minute ventilation at peak exercise [36,37].

There is evidence of a clear benefit of inhaled medications on overall performance in people affected by chronic respiratory diseases [21,34]. However, several studies have questioned the performance-enhancing effect of inhaled drugs on healthy people, especially athletes [38,39].

Non-asthmatic athletes may also experience EIB, particularly under extreme environmental conditions [40,41]. Commonly, short-acting bronchodilators are used 15–30 min before exercise to prevent bronchoconstriction onset. However, recent studies and recommendations discourage the use of SABA as a sole treatment [4,8].

The assumption that inhaled medications have the potential to improve physical performance, resulting in an unfair competitive advantage when taken by healthy athletes brought the anti-doping agencies to regulate their administration. In athletes suffering from asthma and EIB, however, use of inhaled medication is fundamental to resolve exacerbations, reduce their episodes and reduce symptoms burden [17].

Some studies have shown that an acute oral administration of salbutamol has an ergogenic effect on sprint exercise in non-asthmatic athletes [42]. Other studies [43,44,45] found that acute salbutamol ingestion during supramaximal or anaerobic exercise improved performance metrics such as peak power output and fatigue resistance and enhanced anaerobic performance during Wingate tests. For the inhaled form and at doses normally prescribed to treat asthma or EIB, systemic effects are negligible and the performance-enhancing potential is low. However, when administered at higher doses, they have greater systemic absorption, and there is evidence that they may enhance sprint performance and muscle strength, especially when given acutely [46]. Despite evidence of ergogenic effects by β2-agonists, some doubts still remain and WADA, since the 2008 Games, has made numerous changes to inhaled drugs on the Prohibited List [47].

β-agonists have also systemic metabolic effects, especially on lipolysis, glucose homeostasis, and insulin secretion via β2-adrenergic receptors. They act elevating intracellular cAMP, stimulating protein kinase A (PKA) pathways that promote fat breakdown and affect glucose uptake and metabolism [48]. The same pathway accelerates ATP replenishment and promotes a mild anabolic shift by enhancing protein synthesis and suppressing ubiquitin–proteasome–mediated degradation. The net effect can be a modest increase in peak power output during repeated sprints and a faster post-exercise recovery of muscle contractile capacity, though these benefits are dose- and route-dependent [3]. Moreover, inhaled terbutaline enhances anaerobic performance by stimulating glycolysis and increasing power output during repeated sprinting. These effects occur independently of oxygen delivery, suggesting a direct muscle-level effect [49].

3. Effects on the Cardiovascular System

3.1. Impact of Bronchodilators on Cardiovascular System

Inhaled medications, particularly β2-adrenergic agonists such as salbutamol, can exert cardiovascular effects at the molecular level by stimulating β2-adrenergic receptors not only in the lungs but also in the heart and vascular smooth muscle. The hemodynamic effects are mediated by β2-receptor activation, which increases intracellular cAMP via Gs protein–coupled stimulation of adenylyl cyclase, leading to smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilation. This can cause reflex tachycardia and a mild reduction in blood pressure [20].

Specifically, activation of cardiac β2-adrenoceptors results in acute hemodynamic changes such as increased heart rate, increased cardiac output, decreased total peripheral resistance, and reduced parasympathetic outflow [50]. Chronic use of inhaled medications, such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids, is associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular events in people affected by asthma or COPD, due to their anti-inflammatory properties and the reduction in exacerbation events [51].

For what concerns systolic function, a few studies investigated the effects of inhaled medications on heart’s contractility. In patients affected by COPD, a significant increase in RVEF and LVEF has been found at multiple gated radionuclide ventriculography after the administration of salbutamol or pirbuterol [52]. Another study on patients with COPD and lung hyperinflation showed that the combination of indacaterol, a long-acting beta-2 adrenoceptor agonist, and glycopyrronium, a muscarinic antagonist, improved cardiac function by increasing LV end-diastolic volume (EDV) and an increased stroke volume at cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [53]. A recent work on different inhaled beta-2 adrenoceptor agonists has shown a significant increase in LVEF and an improvement in the global longitudinal strain (GLS) after the administration of salbutamol, formoterol and their combination in 24 healthy, non-asthmatic female and male endurance athletes. This effect was particularly relevant in female athletes with a more important increase in LV systolic function than in male athletes. Notably, higher serum concentrations for both salbutamol and formoterol were detectable in female athletes while higher concentrations of salbutamol have been observed with the combined inhalation of salbutamol plus formoterol in male athletes [54].

3.2. Potential Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Misuse (e.g., Arrhythmias, Increased Workload)

Use of inhaled medications has also been associated with risks, especially for the cardiovascular system. Side effects of inhaled medications are especially reported when inhaled medications are overused or misused, and this is common in healthy athletes using this class of drug to enhance their physical performance [55]. Salbutamol, for example, has been demonstrated to cause a reduction in vascular function and an increase in arterial stiffness in people suffering from asthma [56]. The potential risk of side cardiac effects with abuse of beta-2 adrenoceptor agonists is linked to their action on β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, both expressed in the heart tissue and involved in positive cardiotonic chronotropic regulation, cardiac myocyte growth and cardiac toxicity [57]. As previous mentioned, the shift in cardiovascular autonomic control towards decreased parasympathetic tone associated with the acute use of salbutamol could lead to an increase in heart rate and cardiac output with an overstress of the heart [50]. In fact, some of the most common adverse side effects are tachycardia, supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, hypokalemia, gastrointestinal disturbances or tremor [58,59].

Moreover, beta-2 adrenergic agonists such as salbutamol and albuterol, have a well-documented effect on serum potassium levels. Through beta-2 receptors stimulation on cell membranes, they activate the sodium-potassium ATPase pump and driving potassium from the extracellular space into cells. This mechanism can lead to transient hypokalemia, especially when beta-2 agonists are used in high doses or administered repeatedly, such as during acute asthma exacerbations or when used via nebulization, augmenting the risk of arrhythmias [60]. Studies have also demonstrated that beta-2 agonists can prolong the corrected QT interval (QTc), in some cases unmasking congenital long QT syndromes in previous asymptomatic patients [61]. Terbutaline, for example, has shown to prolong QTc in young and healthy male subjects; this effect was closely associated with a decrease in plasma potassium levels, augmenting the risk for malignant arrhythmias [62].

Inhaled anticholinergics, such as ipratropium and tiotropium, have also been scrutinized for potential cardiac risks. These drugs can reduce parasympathetic activity and may lead to increased heart rate and reduced heart rate variability, which are markers of cardiac autonomic imbalance [63]. Tiotropium, in particular, has raised concerns due to early reports suggesting an elevated risk of stroke and myocardial infarction; however, subsequent large-scale trials such as the TIOSPIR study did not confirm these findings, and tiotropium is now generally considered safe for most patients when used as directed [64,65].

Theophylline’s cardiovascular effects warrant careful consideration. In healthy individuals, theophylline can increase heart rate and cardiac output, effects that are more pronounced during physical exertion or in combination with beta-agonists [66]. In patients with congestive heart failure, theophylline may enhance sympathetic activity and improve ventilation without significantly worsening hemodynamics [67]. Moreover, elevated plasma concentrations are associated with significant arrhythmic risk, including both supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, which can occur even in the absence of preexisting cardiac disease [68].

Inhaled corticosteroids may also pose cardiovascular risks when used in high doses or over long durations. Although systemic absorption is lower compared to oral corticosteroids, chronic ICS use has been associated with metabolic changes, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and insulin resistance, which are all risk factors for cardiovascular disease [69]. Table 1 summarizes the main cardiovascular effects and associated risks of different classes of inhaled medications, highlighting their impact on cardiac function and potential implications for athlete health and doping considerations.

Table 1.

Cardiovascular effects and risks associated with different classes of inhaled medications commonly used in athletic populations. CV, cardiovascular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; MI, myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; QTc, corrected QT interval; Na+/K+ ATPase, sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase; ↓ = reduction; ↑ = increase.

4. Effects on Muscle Function

4.1. Influence on Muscle Contraction and Performance

The effect of β2-agonists on skeletal muscle contraction and hypertrophy is well established. This occurs through β2-receptor stimulation in skeletal muscle, which elevates cAMP and activates protein kinase A (PKA)–mediated signaling [70].

PKA phosphorylates a variety of downstream targets, including CREB (cAMP response element–binding protein) and components of the Akt/mTOR pathway, both of which are involved in promoting muscle protein synthesis and cellular growth [71,72]. Additionally, PKA activation modulates eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) and Akt2, enhancing translation and anabolic signalling [71]. This cascade supports fiber-type remodeling (favoring fast-twitch MHC IIa fibers), increased myofibrillar protein synthesis, and net muscle hypertrophy, especially when combined with resistance training [73]. However, the effects appear to vary by training type, present during habitual and resistance training, but absent during endurance training [74].

Acute administration of high doses of terbutaline in trained men have shown to improve Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, leading to increased contractile force and power output during maximal voluntary and evoked contractions. Moreover, it counteracted exercise-induced reductions in Na+–K+-ATPase, preventing impairing ion balance and muscle excitability [75]. Oral administration of terbutaline has also shown to produce an increase in lean muscle mass and insulin sensitivity in healthy young men. This effect is not accompanied by canonical increases in GLUT4 or metabolic enzyme content, implying that muscle hypertrophy itself is a major contributor to improved glucose disposal [72]. Also salbutamol may enhance calcium sensitivity in muscle fibers, amplifying the benefits of resistance exercise. Combining oral salbutamol with targeted resistance training effectively maintains, and even improves, ankle extensor strength during prolonged unloading, particularly benefiting women [76]. This evidence suggests that β2-agonist administration may be a viable countermeasure against disuse-induced muscle loss, but it could also raise concerns about doping, particularly in strength sports.

Although most mechanistic evidence derives from studies using systemic or oral β2-agonist administration, comparable effects on intracellular signalling, muscle contractility, and performance have also been observed following inhaled administration, particularly at high therapeutic or supratherapeutic doses of terbutaline, formoterol, and salbutamol.

High-dose inhaled terbutaline has proven to enhance muscle strength, sprint performance and lean body mass in trained men [77]. However, prolonged use of terbutaline has been shown to hinder skeletal muscle adaptation in response to high-intensity training [71]. Formoterol and salbutamol can acutely increase muscle strength and power output in healthy individuals and trained athletes [78,79]. The mechanism involves the same β2-receptor-mediated modulation of intracellular signalling pathways previously discussed that enhance calcium handling, sodium-potassium pump activity, and sarcoplasmic reticulum function, factors critical for rapid and forceful muscle contractions [80]. The increased glycolytic flux and anaerobic energy production during sprinting, potentially delaying the onset of fatigue and supporting higher power outputs [49,78]. Chronic administration may further amplify these effects by promoting muscle hypertrophy and fiber-type shifts toward more glycolytic phenotypes [81].

Use of GCs, particularly oral or injectable forms, was associated with improvements in endurance-related outcomes such as time to exhaustion and exercise capacity in healthy individuals. They may lead to moderate improvements in submaximal and maximal exercise performance, likely due to their anti-inflammatory, euphoric, and metabolic effects [82,83]. However, there is currently no clear evidence regarding the effects of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) on these outcomes.

4.2. Potential Benefits for Strength and Power Athletes

The ergogenic potential of inhaled β2-agonists has gained significant interest in strength and power disciplines, where short bursts of high-intensity performance are crucial. Though traditionally used for bronchodilation in asthmatics, evidence suggests that β2-agonists, particularly in supratherapeutic doses or under specific conditions, may improve anaerobic performance, muscle strength, and power output in non-asthmatic individuals [10,84,85].

Meta-analyses and controlled trials confirm that inhaled β2-agonists like salbutamol and formoterol can produce acute improvements in maximal voluntary contraction, sprint performance and muscle power, albeit with individual variability [10,39]. For example, formoterol inhalation has been shown to significantly enhance repeated sprint ability and high-intensity cycling performance in elite athletes, likely by increasing muscle contractility, reducing fatigue, and improving glycolytic energy contribution [78,86].

Mechanistically, these benefits are largely attributed to β2-receptor-mediated pathways that enhance calcium handling, improve sarcoplasmic reticulum function, and increase Na+–K+-ATPase activity, facilitating faster and more forceful contractions during high-intensity efforts [78]. Despite these findings, the magnitude of ergogenic effects appears dose-dependent and context-specific. Standard therapeutic doses of inhaled salbutamol (e.g., ≤800 µg/day) have generally shown limited or no significant impact on muscle strength or sprint performance in non-asthmatic athletes [87,88,89]. However, higher doses (exceeding WADA’s permitted limits) can lead to measurable increases in lean mass, muscle force, and sprint capacity, raising concerns about doping and unfair advantages in competitive environments [90,91]. However, chronic use of terbutaline has been reported to impair skeletal muscle adaption following high-intensity training [71].

While β2-agonists have shown ergogenic potential, the effects of corticosteroids on strength and power performance appear to differ depending on the route of administration. Oral corticosteroids, such as prednisolone, have demonstrated some capacity to improve endurance and high-intensity exercise performance when used acutely or over short periods. Several studies involving acute or short-term oral prednisolone intake reported improved time to exhaustion, enhanced endurance capacity, and altered substrate utilization during submaximal exercise. These effects are thought to result from glucocorticoid-induced euphoria, blunting of fatigue perception, anti-inflammatory effects, and shifts in energy metabolism [92,93,94]. In contrast, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) appear to have limited or no ergogenic effects on strength and power performance in healthy athletes. Kuipers et al. (2008) found that four weeks of inhaled corticosteroid treatment did not enhance maximal power output in trained endurance athletes [95]. While ICS may reduce airway inflammation and improve pulmonary function in asthmatic athletes, their systemic absorption is minimal, and their effects on muscle performance are negligible in healthy subjects. Table 2 summarizes the mechanisms, muscle effects, and performance outcomes of inhaled and oral β2-agonists and corticosteroids.

Table 2.

Effects of inhaled and oral β2-agonists and corticosteroids on muscle function, performance outcomes, and potential implications for athletes. PKA, protein kinase A; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CREB, cAMP response element–binding protein; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; eEF2, eukaryotic elongation factor 2; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; MHC IIa, myosin heavy chain type IIa; ↓ = reduction; ↑ = increase.

5. Doping Concerns and Ethical Implications

5.1. Current Regulations and Guidelines on Permissible Thresholds for Therapeutic Use

Inhaled medications occupy a complex regulatory space because they are both essential treatments and potential performance enhancers. As previously discussed, the ergogenic effect depends on formulation, dosage, and type of activity. At standard therapeutic inhaled doses, ergogenic effects are minimal, but high doses improve anaerobic power and muscle strength.

To mitigate the potential misuse of inhaled medications while ensuring access for athletes with legitimate medical needs, WADA has established regulatory thresholds that reflect a nuanced approach that differentiates between therapeutic use and potential misuse. All β2-agonists are classified as prohibited substances under Section S3 of the 2025 WADA Prohibited List, applicable both in- and out-of-competition [96]. This category encompasses both selective and non-selective β2-agonists, including substances such as salbutamol, salmeterol, formoterol and vilanterol. The rationale for this classification stems from the potential performance-enhancing effects of these drugs, which, when used improperly, can provide athletes with an unfair advantage. However, WADA acknowledges the legitimate medical use of certain inhaled β2-agonists at established therapeutic doses for conditions like asthma and EIB, leading to specific exceptions in the regulations.

For inhaled salbutamol, WADA permits a maximum dose of 1600 micrograms over 24 h, with no single dose exceeding 600 micrograms within any 8-h period. Similarly, inhaled formoterol is allowed up to a maximum delivered dose of 54 micrograms over 24 h, with no more than 36 micrograms administered within any 12-h period. Inhaled salmeterol is permitted up to 200 micrograms per 24 h, and inhaled vilanterol up to 25 micrograms per 24 h. These dosage limits are designed to ensure that the use of these medications remains within therapeutic boundaries and does not confer performance-enhancing benefits.

A critical aspect of WADA’s regulations is the monitoring of urinary concentrations of these substances. The presence of salbutamol in urine exceeding 1000 ng/mL or formoterol exceeding 40 ng/mL is considered inconsistent with therapeutic use and will be regarded as an Adverse Analytical Finding (AAF), potentially leading to an anti-doping rule violation (ADRV) (Prohibited List 2026) and a period of ineligibility from sport or the potential stripping of all results from the date of the violation [9]. In such cases, the athlete bears the burden of proving, through a controlled pharmacokinetic study, that the elevated levels resulted from the permitted inhaled doses. Recent data on AAFs for commonly misused β2-agonists highlight trends in anti-doping testing. In 2022, testing identified 47 cases of terbutaline, 7 cases of salbutamol, 2 cases of fenoterol, and 154 cases of clenbuterol [97]. In 2023, terbutaline was detected in 35 cases, salbutamol in 15 cases (approximately twice the number reported in 2022), fenoterol in 5 cases (also a two-fold increase), and clenbuterol in 34 cases, representing a substantial decrease compared with 2022 [98]. These figures illustrate ongoing monitoring of inhaled β2-agonists and clenbuterol in professional sports and underscore fluctuations in detected AAFs over time. Clenbuterol is a β2-agonist with bronchodilator activity that is approved for human use in a limited number of countries (e.g., parts of Eastern Europe and Latin America) for conditions such as asthma or COPD, but it is not approved in the United States of America and in Europe. The notably high numbers of AAFs for clenbuterol may reflect several overlapping factors: (1) intentional doping use, exploiting its combined anabolic, fat-loss, and bronchodilation properties; (2) therapeutic use without an appropriate Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) in those jurisdictions where it is legitimately approved; (3) unintentional ingestion from contaminated meat or animal products, especially in countries where clenbuterol is used illegally in livestock, which has been documented as a source of inadvertent positive tests. Finally, contaminated dietary supplements (often fat-burner products or illicit preparations) may also contribute to inadvertent findings [99].

Athletes requiring the use of inhaled β2-agonists beyond the specified limits must apply for a TUE. The TUE process involves a thorough review of the athlete’s medical history, diagnostic tests (such as spirometry or bronchoprovocation tests), and justification for the need to exceed standard dosage limits. This process ensures that the use of these medications is medically necessary and does not provide the athlete with a competitive advantage. The TUE system is integral to balancing the legitimate medical needs of athletes with the overarching goal of preserving the integrity of competition.

ICS, conversely, are not prohibited by WADA when administered via inhalation at doses within the manufacturer’s recommended limits. This includes medications such as fluticasone, budesonide, and beclomethasone.

Despite its safeguards, the TUE system has faced criticism for potential inconsistencies, lack of transparency, and the possibility of abuse, especially when some national anti-doping organizations appear more lenient or rigorous than others in approving exemptions. Moreover, distrust in TUE administration has been reported among athletes, especially in those that have had experience of TUEs [100].

5.2. Considerations in Medical Use Versus Doping Misuse

Several high-profile doping cases highlight the misuse of inhaled medications. In 2017, a British cyclist tested positive for salbutamol above permitted levels during the Vuelta a España. A year later, UCI and WADA accepted that the elevated concentration could be explained by a severe asthma attack, not intentional misuse, and closed the case [12]. In 2014, an Italian cyclist exceeded the urinary threshold for salbutamol. The Swiss Olympic Disciplinary Chamber concluded he had acted negligently but without intent to dope, resulting in a 9-month suspension [13]. Another case involved a Spanish cyclist who received a 2-year ban and was stripped of his 2010 Tour de France and 2011 Giro d’Italia titles after testing positive for clenbuterol, a β2-agonist with anabolic effects used off-label as a bronchodilator [14]. More recently, in 2020, a Swiss cyclist Schelling tested positive for the β2-agonist terbutaline during the Tour du Rwanda and received a four-month ban for a non-intentional anti-doping rule violation, as terbutaline use requires a valid TUE [101].

The distinction between therapeutic use and performance-enhancing misuse is a central ethical concern in sports medicine. As previous exposed, athletes have a higher prevalence of asthma and EIB compared to the general population. While this could reflect better diagnostic vigilance and environmental exposure (e.g., to cold air, chlorine, or pollutants), some experts argue that diagnostic inflation may be occurring, where athletes without clinical need are prescribed inhaled medications to gain a competitive advantage [102].

This concern is compounded by the potential ergogenic effects of β2-agonists in supratherapeutic doses that suggests that even marginal misuse can shift the balance of competition, violating the ethical principles of fairness and respect for opponents.

On the other hand, denying access to needed medications out of suspicion or over-regulation can harm athletes with genuine medical conditions. The perception that asthma medication may enhance sports performance has created a negative stigma towards athletes with asthma, inhaler therapy, and TUEs. In this context, both athletes and clinicians may have inadequate knowledge of current anti-doping policies regarding asthma medication, increasing the risk of receiving AAFs, committing ADRVs, or undertreating asthma [100,103]. Poorly controlled asthma can severely impair performance and increase the risk of exercise-related complications such as airway collapse, hypoxemia, or even hospitalization [104]. Moreover, it has been suggested that stigma surrounding asthma treatment and concerns about violating anti-doping rules may be leading some athletes to avoid adhering to their prescribed therapy [105]. Therefore, ethical policymaking must protect both the athlete’s health and the integrity of sport by facilitating timely treatment while implementing rigorous oversight mechanisms to detect abuse.

The challenge lies in identifying and closing the regulatory grey zones. Recent advancements such as the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP), which tracks individual physiological parameters over time, may offer promising tools to detect unusual patterns indicative of misuse, along with “omics” strategies and artificial intelligence [106,107]. Continued research into drug metabolism, objective diagnostic thresholds, and individualized response profiles may also support more accurate assessments of legitimate need versus strategic use. Moreover, promoting education for athletes, coaches, and healthcare providers on ethical medication use and the potential risk of doping is critical in fostering a culture of integrity and responsibility.

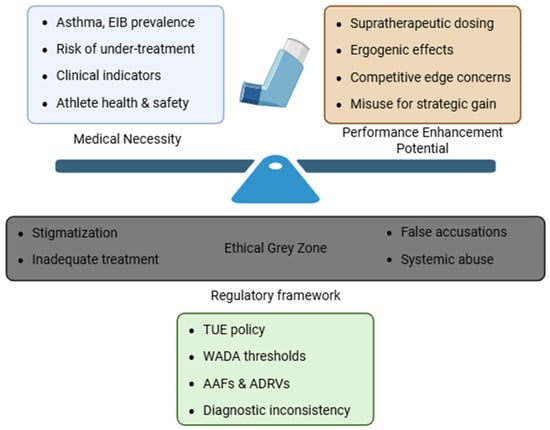

Addressing these challenges requires a combination of science-based policy, transparent governance, and a shared commitment to both athlete health and fair play. Figure 1 illustrates the ethical tensions surrounding inhaled medication use in sport.

Figure 1.

Ethical Complexity Surrounding inhaled medication use in sport. The image highlights the ethical and regulatory challenges in managing asthma treatment in athletes, weighting clinical need against potential performance enhancement. An ethical grey zone emerges, consisting of stigmatization, risk of undertreatment, false accusations and systemic abuse. In this context, the regulatory framework, based on WADA policies, aims to mediate this complex landscape.

6. Detection Methods for Inhaled Medications

6.1. Urine and Blood Testing Protocols

The primary matrix for monitoring inhaled β2-agonists in athletes is urine, owing to its non-invasive collection and extended detection window. Blood sampling, while more specific for pharmacokinetic profiling, remains less practical due to rapid clearance and logistical challenges in anti-doping settings. The WADA permits therapeutic inhalation of β2-agonists such as salbutamol and formoterol within specified dose limits yet enforces urinary thresholds to discriminate acceptable use from doping violations. The limit for salbutamol in urine, for example, is 1000 ng/mL, while formoterol has a threshold of 40 ng/mL [96]. The regulatory framework is codified in WADA’s Technical Document TD2022DL, which details decision limits (DLs), internal standardization, chromatographic confirmation, ion-ratio verification, and minimum performance criteria [108].

Urinary thresholds are designed to accommodate typical therapeutic dosing while flagging supratherapeutic usage. However, the practical application of these thresholds is complex due to large inter-individual and intra-individual variability. Empirical findings confirm that inhaled formoterol and salmeterol yield urinary concentrations in the low to sub-ng/mL range following therapeutic inhalation, comfortably below WADA thresholds for formoterol and far below salbutamol’s limit [109,110].

However, numerous studies have reported that urinary concentrations of inhaled β2-agonists can vary significantly due to factors beyond dose. Haase et al. (2016) documented that intense exercise and moderate dehydration markedly elevated urinary salbutamol levels following high-dose administration, calling into question the reliability of thresholds in athletic contexts [111]. Similarly, Dickinson et al. (2014) demonstrated differences in excretion linked hydration status, irrespective of gender or ethnicity [112]. Both findings emphasize the need for context-specific judgment when interpreting urinary results. Moreover, Heuberger et al. (2018) critically highlighted the futility of current urine-based detection protocols for salbutamol [113]. Their analysis concluded that the high threshold and wide variability contribute to frequent false negatives; athletes taking supratherapeutic doses may remain below the set limit, while therapeutic usage under burdening conditions could trigger false positives. This raises serious concerns about the fairness and reliability of urine-based control strategies [113].

Blood or plasma sampling can offer higher resolution snapshots of recent drug intake, reflecting peak concentrations more faithfully than urine. However, β2-agonists exhibit rapid absorption and clearance from plasma, meaning that sampling must occur within hours after dosing [114]. Practical challenges such as multiple sampling needs, invasive collection, and ethical considerations limit adoption in competition settings, relegating blood testing to clinical studies or investigatory follow-ups. Despite these limitations, combining plasma with urine can help pinpoint timing and dosing.

For salmeterol, whose use is also permitted via inhalation, no formal urinary threshold is currently defined by WADA. However, Jacobson et al. (2017) used enantioselective UPLC-MS/MS to quantify (R)- and (S)-salmeterol in urine after single doses of 50 µg and 200 µg [115]. They reported median peak concentrations of 0.084 ng/mL and 2.1 ng/mL respectively, with a maximum observed level of only 5.7 ng/mL. These findings suggest that inhaled racemic salmeterol results in urinary concentrations well below typical analytical cut-offs, highlighting the critical need for more sensitive assays and/or threshold guidelines [115].

6.2. Advanced Technologies for Detecting Bronchodilators

The evolution of High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) platforms empowers simultaneous screening of multiple prohibited substances with unmatched sensitivity. Liu et al. (2023) employed an HRMS-based workflow capable of co-detecting an array of β2-agonists, their metabolites, and conjugates in a single sample [116]. This approach significantly reduces false negatives from unrelated drug presence or metabolic cross-interference [116]. Similarly, Thevis et al. (2022) lauded non-targeted HRMS profiling as a transformative tool, capable of identifying unknown metabolites, structural analogues, and emerging doping agents, including designer β2-agonists [117]. High-resolution data can retrospectively identify new analytes upon database updates, extending the lifespan of each sample and strengthening retrospective analysis [117].

Chiral separation techniques afford precise targeting of enantiomers such as (R)- and (S)-salmeterol, which possess divergent pharmacodynamics and metabolic rates. Jacobson et al. (2022) demonstrated that measuring the R-enantiomer improves both sensitivity to recent therapeutic use and specificity, making differentiations between metabolic sources [118]. The “salmeterol anomaly” further highlights cases in which nonspecific methods flagged samples that, under enantioselective scrutiny, aligned with therapeutic administration [118].

Metabolite-targeted assays seek to detect both parent β2-agonists and their phase II conjugates or phase I oxidized products. Orlovius et al. (2009) discovered a sulfoconjugated metabolite of terbutaline, a marker absent in the base drug, into doping detection tools [119]. Chundela & Große (2015) developed LC–MS/MS assays to detect vilanterol and olodaterol, including their specific metabolites, enabling detection in low-dose therapeutic contexts [120].

While mass spectrometry is central to laboratory testing, immunoassay and biosensor methods are under development for rapid, high-throughput screening. Ouyang et al. (2022) reviewed immunoassays capable of detecting β2-agonists across foods and biologics, highlighting their low-cost, user-friendly potential [121]. Xu et al. (2022) introduced a colloidal gold-based immunosensor capable of detecting up to 12 β2-agonists simultaneously in urine with high sensitivity [122]. Though not yet accepted in WADA labs, such tools may streamline preliminary rounds of testing. These methods offer portability and speed, important advantages for in-competition screens or field testing. Limitations include cross-reactivity issues and generally lower specificity compared to MS-based confirmatory methods, which require ongoing refinement to meet WADA accuracy criteria.

Recently, the microsampling technique of dried blood spots (DBS) has emerged as a promising complementary matrix to urine and conventional venous blood in anti-doping control. WADA has officially approved the use of DBS for doping control through the Technical Document TD2021DBS, which outlines the requirements for sample collection, transport, and analysis [108]. DBS enables minimally invasive collection of micro-volumes of capillary whole blood, offers simplified transport/storage and potentially robust quantitative assessment of circulating drug concentrations, thus opening new perspectives for improved result interpretation [123]. DBS could help bridge the gap between urinary metabolite levels and the actual systemic exposure of an athlete, supporting more accurate interpretation of quantitative results in anti-doping investigations.

6.3. Challenges in Detecting Inhaled Medications Due to Short Half-Lives and Dosage Variation

Short elimination half-lives, typically in the range of few hours, characterize many inhaled bronchodilators. In athletes undergoing intense physical training, both salmeterol and its α-hydroxymetabolite fall below quantifiable limits within 12–24 h after a single dry powder inhalation. In contrast, chronic inhalation may lead to higher concentrations of both the drug and its metabolite in the bloodstream compared to a single dose [124]. Similarly, urinary profiles of vilanterol and its metabolites, following both therapeutic and elevated dosing, highlight the rapid decline and significant inter-individual variability of both the parent compound and its metabolites [125]. These findings underscore the risk of false-negative results when sampling does not occur near peak excretion.

Urinary drug concentrations do not scale predictably with inhaled dose due to influences such as device aerosol characteristics, pulmonary deposition, swallow/absorption ratios, and metabolic pathway activation. Fitch (2018) critiques the assumption that urine concentration equates dose, emphasizing that route and method critically skew interpretations [126]. Heuberger et al. (2018) further demonstrated that toxicologically significant doses could remain undetected in standard control regimes [113].

Terbutaline’s case supports this view. Jacobson and Hostrup (2017) advocated for introducing a dose-based urinary threshold for inhaled terbutaline, arguing that clearly defined dose-concentration relationships would help distinguish therapeutic use from misuse, reduce false positives, and align anti-doping policy with pharmacological evidence [127].

Athletic activity, particularly endurance sports, affects pharmacokinetics, notably through dehydration, redistribution of body fluids, and increased excretion. Haase et al. (2016) confirmed that 1600 µg salbutamol inhaled post-exercise led to urinary concentrations exceeding 2000 ng/mL in dehydrated subjects, twice WADA thresholds [111]. Similarly, Dickinson et al. (2014) showed hydration and activity independently influence detection, implicating technical thresholds in risking false enhancement or suppression of results [112].

Detection protocols must address both parent compounds and their conjugates. For instance, terbutaline sulfoconjugates may persist in detectable form even when the base drug has cleared. Accurate detection relies on validated assays to include both classes. [119].

The proliferation of new inhaled drugs (e.g., olodaterol, vilanterol), introduced for COPD, requires method adaptation. Early detection efforts by Chundela & Große (2015) built assay libraries capable of identifying olodaterol and vilanterol, showing imperative response times required for emerging inhalants [120].

Many β2-agonists are chiral, and their enantiomers often differ in both pharmacological activity and metabolic fate. Standard immunoassays and non-chiral LC-MS methods cannot distinguish between these enantiomers. For example, racemic salmeterol yields a mixture in urine, though only the (R)-enantiomer is pharmacologically active. Jacobson et al. (2022) demonstrated that enantioselective measurement of urinary salmeterol offers improved interpretive clarity and may support future doping control efforts, especially if thresholds are introduced [118]. Their findings highlight the analytical advantage of resolving enantiomer-specific disposition in evaluating therapeutic use versus potential misuse [118].

WADA’s guidelines provide crucial structure but depend on the integrity of confirmatory tests [108]. Invalid or borderline results may unjustly penalize athletes or, conversely, fail to identify substance abuse. Addressing this challenge requires robust cross-laboratory validation of HRMS, immunoassay screens, and emerging analytical platforms, alongside inter-laboratory ring trials to ensure jurisdictional consistency. Furthermore, data-driven adjustments to urinary thresholds, particularly for chiral drugs or compounds with unpredictable metabolite profiles, are essential to improving both fairness and analytical accuracy. Increasingly, contaminated over-the-counter products and dietary supplements introduce β2-agonists unintentionally. For example, higenamine is a plant-derived beta-2 adrenergic agonist found in various herbal supplements, known for its stimulant and fat-burning properties, that is banned by WADA at all times due to its potential performance-enhancing effects. Stojanovic et al. tracked urinary higenamine in women following supplement consumption, showing potential interference with doping tests [128]. Thorough education on all relevant sources, plus careful laboratory source verification, is essential to avoid accidental doping cases.

Non-targeted metabolomic profiling detects secondary metabolites and metabolic fingerprint shifts characteristic of bronchodilator use, often persisting after the parent drug has been cleared. Kiss et al. applied ultra-HRMS paired with multivariate statistics to urine from athletes who used salbutamol or budesonide [129]. They identified distinct metabolite signals, beyond the parent compounds, that differentiated treated individuals from clean controls, demonstrating how HRMS-derived metabolic patterns can reveal drug exposure even when standard assays no longer detect the drug. Similarly, Coll et al. systematically characterized the urinary excretion profiles of budesonide and its metabolites after varying routes of administration (intranasal, inhaled, and oral), emphasizing that metabolite patterns differed significantly depending on dose and delivery method [130]. These findings underscore the value of incorporating detailed metabolite mapping into anti-doping protocols, not only for performance-enhancing agents like β2-agonists, but also for substances like inhaled corticosteroids, which may not directly enhance performance yet remain subject to misuse. Integrating metabolomic data could refine threshold interpretations, enable retrospective detection, and improve fairness by reducing both false positives and undetected infractions.

7. Conclusions

Inhaled medications occupy a unique position in sports medicine, being essential for the treatment of asthma and EIB; however, they may confer performance benefits when misused. Bronchodilators can enhance cardiovascular function, muscle performance, and recovery at supratherapeutic doses, while inhaled corticosteroids exert mainly anti-inflammatory effects with limited ergogenic potential.

The regulatory framework addresses this duality through WADA thresholds and the TUE system, which provide athletes access to essential therapies for their respiratory conditions while protecting the integrity of competition. Nevertheless, variability in individual responses and detection challenges continue to complicate enforcement, as shown by high-profile cases involving elite athletes and ongoing debates on ergogenic thresholds.

Future progress will rely on more refined detection methods, such as enantioselective assays and metabolomic profiling, together with transparent governance and effective education. Ultimately, ensuring athletes’ health and fair play requires policies that remain scientifically robust, ethically rigorous, and consistently applied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., A.S., A.F., M.C. and F.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C., A.S., E.S., C.F., G.P.U., F.P. and F.G.; supervision, R.C., A.S., E.S., C.F., G.P.U., F.P. and F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- The Global Asthma Report 2022. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2022, 26 (Suppl. S1), 1–104. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Tao, J.; Wang, J.; She, W.; Zou, Y.; Li, R.; Ma, Y.; Sun, C.; Bi, S.; Wei, S.; et al. Global, Regional, National Burden of Asthma from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Incidence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 80, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Jessen, S. Beyond Bronchodilation: Illuminating the Performance Benefits of Inhaled Beta2—Agonists in Sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrione, P.; Sgrò, P.; Giombini, A.; Segreti, A.; Steinacker, J.M.; Pigozzi, F. Relevant Medical Conditions Affecting Sports Participation. In Sports Physician Handbook; Pitsiladis, Y.P., Yung, P.S.-H., Hutchinson, M.R., Pigozzi, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 139–198. [Google Scholar]

- Price, O.J.; Sewry, N.; Schwellnus, M.; Backer, V.; Reier-Nilsen, T.; Bougault, V.; Pedersen, L.; Chenuel, B.; Larsson, K.; Hull, J.H. Prevalence of Lower Airway Dysfunction in Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by a Subgroup of the IOC Consensus Group on “Acute Respiratory Illness in the Athlete”. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helenius, I.; Haahtela, T. Allergy and Asthma in Elite Summer Sport Athletes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 106, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, J.A.; La Gerche, A.; Hull, J.H. Is the Healthy Respiratory System Built Just Right, Overbuilt, or Underbuilt to Meet the Demands Imposed by Exercise? J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 129, 1235–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ora, J.; De Marco, P.; Gabriele, M.; Cazzola, M.; Rogliani, P. Exercise-Induced Asthma: Managing Respiratory Issues in Athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Anti-Doping Code. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/2021_wada_code.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Riiser, A.; Stensrud, T.; Stang, J.; Andersen, L.B. Can Β2-Agonists Have an Ergogenic Effect on Strength, Sprint or Power Performance? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsen, K.-H.; Hem, E.; Stensrud, T.; Held, T.; Herland, K.; Mowinckel, P. Can Asthma Treatment in Sports Be Doping? The Effect of the Rapid Onset, Long-Acting Inhaled Beta2-Agonist Formoterol upon Endurance Performance in Healthy Well-Trained Athletes. Respir. Med. 2001, 95, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Anti Doping Agency. WADA Clarifies Facts Regarding UCI Decision on Christopher Froome. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/news/wada-clarifies-facts-regarding-uci-decision-christopher-froome (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Sky Sports. Diego Ulissi Given Back-Dated Nine-Month Ban for Failing Drugs Test at 2014 Giro d’Italia. Available online: https://www.skysports.com/more-sports/cycling/news/12040/9652137/diego-ulissi-given-backdated-nine-month-ban-for-failing-drugs-test-at-2014-giro-ditalia (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Fotheringham, W. Alberto Contador Gets Two-Year Ban and Stripped of 2010 Tour de France. The Guardian. 6 February 2012. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2012/feb/06/alberto-contador-ban-tour-cycling (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- World Anti Doping Agency. 2026 Prohibited List. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/2026-prohibited-list (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Stolz, D.; Matera, M.G.; Rogliani, P.; van den Berge, M.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Gosens, R.; Singh, D.; Hanania, N.; Cazzola, M.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.-H. Current and Future Developments in the Pharmacology of Asthma and COPD: ERS Seminar, Naples 2022. Breathe 2023, 19, 220267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024 GINA Main Report. Global Initiative for Asthma—GINA. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/2024-report/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Storgaard Petersen, R.; Hallas, H.; Brustad, N.; Chawes, B. Short-Term Efficacy of Inhaled Short-Acting Beta-2-Agonists for Acute Wheeze/Asthma Symptoms in Preschool-Aged Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thorax 2025, 80, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Beta2-Adrenoceptors: Mechanisms of Action of Beta2-Agonists. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2001, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Beta(2)-Adrenergic Receptor Function, Response, and Regulation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, M.G.; Page, C.P.; Calzetta, L.; Rogliani, P.; Cazzola, M. Pharmacology and Therapeutics of Bronchodilators Revisited. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 218–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koarai, A.; Ichinose, M. Possible Involvement of Acetylcholine-Mediated Inflammation in Airway Diseases. Allergol. Int. 2018, 67, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muiser, S.; Gosens, R.; van den Berge, M.; Kerstjens, H.A.M. Understanding the Role of Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists in Asthma Treatment. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022, 128, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadley, K.J.; Kelly, D.R. Muscarinic Receptor Agonists and Antagonists. Molecules 2001, 6, 142–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Page, C.; Rogliani, P.; Calzetta, L.; Matera, M.G. Dual Bronchodilation for the Treatment of COPD: From Bench to Bedside. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 3657–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Theophylline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. Effects of Theophylline and Theobromine on Exercise Performance and Implications for Competition Sport: A Systematic Review. Drug Test. Anal. 2021, 13, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, D.; Puttanna, A.; Balagopal, V. Systemic Effects of Inhaled Corticosteroids: An Overview. Open Respir. Med. J. 2014, 8, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Glucocorticoids: Molecular Mechanisms. Clin. Sci. 1998, 94, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalin, D.A.; Løkke, A.; Kristiansen, P.; Jensen, C.; Birkefoss, K.; Christensen, H.R.; Godtfredsen, N.S.; Hilberg, O.; Rohde, J.F.; Ussing, A.; et al. A Systematic Review of Blood Eosinophils and Continued Treatment with Inhaled Corticosteroids in Patients with COPD. Respir. Med. 2022, 198, 106880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, S.; Higham, A.; Beech, A.; Singh, D. How Inhaled Corticosteroids Target Inflammation in COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Scientific Rationale for Inhaled Combination Therapy with Long-Acting Beta2-Agonists and Corticosteroids. Eur. Respir. J. 2002, 19, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Matera, M.G. Bronchodilators: Current and Future. Clin. Chest Med. 2014, 35, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marco, F.; Sotgiu, G.; Santus, P.; O’Donnell, D.E.; Beeh, K.-M.; Dore, S.; Roggi, M.A.; Giuliani, L.; Blasi, F.; Centanni, S. Long-Acting Bronchodilators Improve Exercise Capacity in COPD Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissy, H.H.; Kelly, H.W.; Harkins, M.; Szefler, S.J. Inhaled Corticosteroids in Lung Diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerström, F.; Rex, C.E.; Maagaard, M.; Rubak, S.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Heiberg, J. Exercise Performance after Salbutamol Inhalation in Non-Asthmatic, Non-Athlete Individuals: A Randomised, Controlled, Cross-over Trial. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riiser, A.; Stensrud, T.; Stang, J.; Andersen, L.B. Aerobic Performance among Healthy (Non-Asthmatic) Adults Using Beta2-Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.H.; Anderson, S.D.; Bjermer, L.; Bonini, S.; Brusasco, V.; Canonica, W.; Cummiskey, J.; Delgado, L.; Del Giacco, S.R.; Drobnic, F.; et al. Treatment of Exercise-Induced Asthma, Respiratory and Allergic Disorders in Sports and the Relationship to Doping: Part II of the Report from the Joint Task Force of European Respiratory Society (ERS) and European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) in Cooperation with GA(2)LEN. Allergy 2008, 63, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluim, B.M.; de Hon, O.; Staal, J.B.; Limpens, J.; Kuipers, H.; Overbeek, S.E.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Scholten, R.J.P.M. Β2-Agonists and Physical Performance. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, L.-P.; O’Byrne, P.M. Asthma and Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Athletes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreti, A.; Celeski, M.; Guerra, E.; Crispino, S.P.; Vespasiano, F.; Buzzelli, L.; Fossati, C.; Papalia, R.; Pigozzi, F.; Grigioni, F. Effects of Environmental Conditions on Athlete’s Cardiovascular System. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.M.J.; Collomp, K.; Carra, J.; Borrani, F.; Coste, O.; Préfaut, C.; Candau, R. Effect of Acute and Short-Term Oral Salbutamol Treatments on Maximal Power Output in Non-Asthmatic Athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 3251–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collomp, K.; Le Panse, B.; Portier, H.; Lecoq, A.-M.; Jaffre, C.; Beaupied, H.; Richard, O.; Benhamou, L.; Courteix, D.; De Ceaurriz, J. Effects of Acute Salbutamol Intake during a Wingate Test. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Panse, B.; Arlettaz, A.; Portier, H.; Lecoq, A.-M.; De Ceaurriz, J.; Collomp, K. Short Term Salbutamol Ingestion and Supramaximal Exercise in Healthy Women. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Panse, B.; Arlettaz, A.; Portier, H.; Lecoq, A.-M.; De Ceaurriz, J.; Collomp, K. Effects of Acute Salbutamol Intake during Supramaximal Exercise in Women. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breenfeldt Andersen, A.; Jacobson, G.A.; Bejder, J.; Premilovac, D.; Richards, S.M.; Rasmussen, J.J.; Jessen, S.; Hostrup, M. An Abductive Inference Approach to Assess the Performance-Enhancing Effects of Drugs Included on the World Anti-Doping Agency Prohibited List. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, K.D. The Enigma of Inhaled Salbutamol and Sport: Unresolved after 45 Years. Drug Test. Anal. 2017, 9, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipson, L.H. Beta-Agonists and Metabolism. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 110 (Suppl. 6), S313–S317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsen, A.; Hostrup, M.; Söderlund, K.; Karlsson, S.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J. Inhaled Beta2-Agonist Increases Power Output and Glycolysis during Sprinting in Men. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekici, L.; Valipour, A.; Kohansal, R.; Burghuber, O.C. Short-Term Effects of Inhaled Salbutamol on Autonomic Cardiovascular Control in Healthy Subjects: A Placebo-Controlled Study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 67, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lev-Ari, N.; Oberman, B.; Kushnir, S.; Yosef, N.; Shlomi, D. The Cardiovascular Effects of Long-Acting Bronchodilators Inhalers and Inhaled Corticosteroids Purchases among Asthma and COPD Patients. Heart Lung 2025, 70, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.J.; Langford, J.A.; Rudd, R.M. Effects of Oral and Inhaled Salbutamol and Oral Pirbuterol on Right and Left Ventricular Function in Chronic Bronchitis. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1984, 288, 824–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlfeld, J.M.; Vogel-Claussen, J.; Biller, H.; Berliner, D.; Berschneider, K.; Tillmann, H.-C.; Hiltl, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Welte, T. Effect of Lung Deflation with Indacaterol plus Glycopyrronium on Ventricular Filling in Patients with Hyperinflation and COPD (CLAIM): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Crossover, Placebo-Controlled, Single-Centre Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persch, H.; Bizjak, D.A.; Takabayashi, K.; Schober, F.; Winkert, K.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Harps, L.C.; Diel, P.; Parr, M.K.; Zügel, M.; et al. Left Ventricular Systolic Function after Inhalation of Beta-2 Agonists in Healthy Athletes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, G.; Chiappini, S.; Mattioli, F.; Martelli, A.; Schifano, F. β-2 Agonists as Misusing Drugs? Assessment of Both Clenbuterol- and Salbutamol-Related European Medicines Agency Pharmacovigilance Database Reports. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 123, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.E.; Kapoor, K.; Byers, B.W.; Brotto, A.R.; Ghods-Esfahani, D.; Henry, S.L.; St James, R.B.; Stickland, M.K. Acute Effects of Salbutamol on Systemic Vascular Function in People with Asthma. Respir. Med. 2019, 155, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzola, M.; Matera, M.G.; Donner, C.F. Inhaled Beta2-Adrenoceptor Agonists: Cardiovascular Safety in Patients with Obstructive Lung Disease. Drugs 2005, 65, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, P.E.; Koutlianos, N.; Baggish, A.; Bermon, S.; Cavarretta, E.; Deligiannis, A.; Furlanello, F.; Kouidi, E.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Niebauer, J.; et al. Cardiovascular Effects of Doping Substances, Commonly Prescribed Medications and Ergogenic Aids in Relation to Sports: A Position Statement of the Sport Cardiology and Exercise Nucleus of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.; Dawson, A.H.; Brown, J.A. Clenbuterol Toxicity: A NSW Poisons Information Centre Experience. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 200, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.J.; Lipworth, B.J. Pharmacokinetics and Systemic Beta2-Adrenoceptor-Mediated Responses to Inhaled Salbutamol. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 51, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zreik, J.; LaPage, M.J.; Zreik, H. Congenital Long QT Syndrome Unmasked by Albuterol in an Adolescent with Asthma. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 67, e446–e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuusela, T.A.; Jartti, T.T.; Tahvanainen, K.U.O.; Kaila, T.J. Prolongation of QT Interval by Terbutaline in Healthy Subjects. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogale, S.S.; Lee, T.A.; Au, D.H.; Boudreau, D.M.; Sullivan, S.D. Cardiovascular Events Associated with Ipratropium Bromide in COPD. Chest 2010, 137, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Loke, Y.K.; Furberg, C.D. Inhaled Anticholinergics and Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2008, 300, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, R.; Calverley, P.M.A.; Dahl, R.; Dusser, D.; Metzdorf, N.; Müller, A.; Fowler, A.; Anzueto, A. Safety and Efficacy of Tiotropium Respimat versus HandiHaler in Patients Naive to Treatment with Inhaled Anticholinergics: A Post Hoc Analysis of the TIOSPIR Trial. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2015, 25, 15067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Conradson, T.B. Cardiovascular Effects of Two Different Xanthines in Healthy Subjects. Studies at Rest, during Exercise and in Combination with a Beta-Agonist, Terbutaline. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1984, 27, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, S.; Reiter, H.; Lüthje, L.; Delekat, A.; Grunewald, R.W.; Hasenfuss, G.; Somers, V.K. Differential Effects of Theophylline on Sympathetic Excitation, Hemodynamics, and Breathing in Congestive Heart Failure. Circulation 2004, 110, 2157–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessler, C.N.; Cohen, M.D. Cardiac Arrhythmias during Theophylline Toxicity. A Prospective Continuous Electrocardiographic Study. Chest 1990, 98, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipworth, B.J. Systemic Adverse Effects of Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Sainz, R.D. Beta-Adrenergic Agonists and Hypertrophy of Skeletal Muscles. Life Sci. 1992, 50, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostrup, M.; Onslev, J.; Jacobson, G.A.; Wilson, R.; Bangsbo, J. Chronic Β2 -Adrenoceptor Agonist Treatment Alters Muscle Proteome and Functional Adaptations Induced by High Intensity Training in Young Men. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, S.; Baasch-Skytte, T.; Onslev, J.; Eibye, K.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J.; Hostrup, M. Muscle Hypertrophic Effect of Inhaled Beta2-agonist Is Associated with Augmented Insulin-stimulated Whole-body Glucose Disposal in Young Men. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, S.; Reitelseder, S.; Kalsen, A.; Kreiberg, M.; Onslev, J.; Gad, A.; Ørtenblad, N.; Backer, V.; Holm, L.; Bangsbo, J.; et al. Β2-Adrenergic Agonist Salbutamol Augments Hypertrophy in MHCIIa Fibers and Sprint Mean Power Output but Not Muscle Force during 11 Weeks of Resistance Training in Young Men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, S.; Onslev, J.; Lemminger, A.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J.; Hostrup, M. Hypertrophic Effect of Inhaled Beta2 -Agonist with and without Concurrent Exercise Training: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Kalsen, A.; Ørtenblad, N.; Juel, C.; Mørch, K.; Rzeppa, S.; Karlsson, S.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J. Β2-Adrenergic Stimulation Enhances Ca2+ Release and Contractile Properties of Skeletal Muscles, and Counteracts Exercise-Induced Reductions in Na+–K+-ATPase Vmax in Trained Men. J. Physiol. 2014, 592 Pt 24, 5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, J.F.; Hamill, J.L.; Yamauchi, M.; Cook, T.D.; Mercado, D.R.; Wickel, E.E. Albuterol and Exercise Effects on Ankle Extensor Strength during 40 Days of Unloading. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2008, 79, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Kalsen, A.; Bangsbo, J.; Hemmersbach, P.; Karlsson, S.; Backer, V. High-Dose Inhaled Terbutaline Increases Muscle Strength and Enhances Maximal Sprint Performance in Trained Men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 2499–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsen, A.; Hostrup, M.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J. Effect of Formoterol, a Long-Acting Β2-Adrenergic Agonist, on Muscle Strength and Power Output, Metabolism, and Fatigue during Maximal Sprinting in Men. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 310, R1312–R1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, L.; Horan, M.A.; Rothwell, N.J.; Little, R.A. Salbutamol, a Beta 2-Adrenoceptor Agonist, Increases Skeletal Muscle Strength in Young Men. Clin. Sci. 1992, 83, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Cairns, S.P.; Bangsbo, J. Muscle Ionic Shifts During Exercise: Implications for Fatigue and Exercise Performance. Compr. Physiol. 2021, 11, 1895–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Kalsen, A.; Onslev, J.; Jessen, S.; Haase, C.; Habib, S.; Ørtenblad, N.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J. Mechanisms Underlying Enhancements in Muscle Force and Power Output during Maximal Cycle Ergometer Exercise Induced by Chronic Β2-Adrenergic Stimulation in Men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riiser, A.; Stensrud, T.; Andersen, L.B. Glucocorticoids and Physical Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1108062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, K.V.; Chen, K.J.Q.; Diep, D. Effect of Glucocorticoids on Athletic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2022, 32, e151–e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, W.; Meyer, T. Inhaled Beta2 Agonists and Performance in Competitive Athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40 (Suppl. S1), i43–i47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfarth, B.; Wuestenfeld, J.C.; Kindermann, W. Ergogenic Effects of Inhaled Beta2-Agonists in Non-Asthmatic Athletes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 2010, 39, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, J.S.; Jessen, S.; Thomassen, M.; Backer, V.; Bangsbo, J.; Hostrup, M. Inhaled Beta2 -Agonist, Formoterol, Enhances Intense Exercise Performance, and Sprint Ability in Elite Cyclists. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; MacInnis, M.J.; Sporer, B.C.; Rupert, J.L.; Koehle, M.S. Inhaled Salbutamol Does Not Affect Athletic Performance in Asthmatic and Non-Asthmatic Cyclists. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.B.; Labreche, J.M.; McKenzie, D.C. Acute Formoterol Administration Has No Ergogenic Effect in Nonasthmatic Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baak, M.A.; Mayer, L.H.; Kempinski, R.E.; Hartgens, F. Effect of Salbutamol on Muscle Strength and Endurance Performance in Nonasthmatic Men. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, J.; Molphy, J.; Chester, N.; Loosemore, M.; Whyte, G. The Ergogenic Effect of Long-Term Use of High Dose Salbutamol. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2014, 24, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlini, M.; Whyte, G.; Marcora, S.; Loosemore, M.; Chester, N.; Dickinson, J. Improved Sprint Performance with Inhaled Long-Acting Β2-Agonists Combined with Resistance Exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlettaz, A.; Collomp, K.; Portier, H.; Lecoq, A.-M.; Pelle, A.; de Ceaurriz, J. Effects of Acute Prednisolone Intake during Intense Submaximal Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2006, 27, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlettaz, A.; Portier, H.; Lecoq, A.-M.; Labsy, Z.; de Ceaurriz, J.; Collomp, K. Effects of Acute Prednisolone Intake on Substrate Utilization during Submaximal Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2008, 29, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]