Abstract

This pilot study evaluated the visionMC system, a low-cost artificial intelligence system integrating HOG-based facial recognition and voice notifications, for workflow optimization in a family medicine practice. Implemented on a Raspberry Pi 4, the system was tested over two weeks with 50 patients. It achieved 85% recognition accuracy and an average detection time of 3.4 s. Compared with baseline, patient waiting times showed a substantial reduction in waiting time and administrative workload, and the administrative workload decreased by 5–7 min per patient. A satisfaction survey (N = 35) indicated high acceptance, with all scores above 4.5/5, particularly for usefulness and waiting time reduction. These results suggest that visionMC can improve efficiency and enhance patient experience with minimal financial and technical requirements. Larger multicenter studies are warranted to confirm scalability and generalizability. visionMC demonstrates that effective AI integration in small practices is feasible with minimal resources, supporting scalable digital health transformation. Beyond biometric identification, the system’s primary contribution is streamlining practice management by instantly displaying the arriving patient and enabling rapid chart preparation. Personalized greetings enhance patient experience, while email alerts on motion events provide a secondary security benefit. These combined effects drove the observed reductions in waiting and administrative times.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognized as a driver of digital transformation in healthcare [1], with applications ranging from medical image analysis to workflow optimization. In primary care, recent studies emphasize the potential of AI to improve administrative efficiency, reduce documentation burden, and support scalability of services [2,3]. Moreover, digital health research has highlighted challenges such as misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, underlining the importance of reliable and efficient technologies in frontline care [4].

Despite these advances, AI adoption in family medicine practices remains limited. Most solutions are designed for large hospitals with robust Information Technology (IT) infrastructures [5,6], while family physicians continue to face daily challenges such as high patient volumes, time-consuming administrative tasks, and limited resources for digitalization. Automatic patient identification at the entrance, rapid access to medical records, reduced waiting times, and minimization of administrative errors represent strategic priorities for improving efficiency without compromising quality of care. At the same time, automatic detection of unknown individuals enhances office security, offering an additional benefit that supports safe and efficient practice management.

Facial recognition offers a fast, contactless biometric solution that eliminates physical access cards and streamlines patient flow, while voice interaction enhances usability and communication. Integrating these technologies in a low-cost, accessible system could help bridge the digitalization gap between large healthcare institutions and small primary care practices.

Although CNN-based facial recognition models typically exceed 95% accuracy on benchmark datasets, they require higher computational resources and often depend on GPU acceleration or cloud-based inference. For the context of this pilot study—namely a low-cost, privacy-preserving, offline device suitable for small family medicine practices—we selected the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) method because it ensures deterministic real-time performance on Raspberry Pi hardware, minimal memory usage, and fully local processing. This design choice prioritizes affordability, reproducibility, and GDPR compliance over benchmark-level accuracy. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that lightweight CNN architectures (e.g., MobileNetV2 and ShuffleNet) represent promising alternatives for future iterations of visionMC.

visionMC is a custom prototype system developed entirely by the authors. The suffix “MC” functions as an internal project identifier derived from the initials of the corresponding author and is used consistently throughout the development materials. The system integrates three core components: (1) edge-based facial recognition for patient arrival identification, (2) automated voice greetings designed to enhance patient experience, and (3) real-time notifications presented within the User Interface (UI) to support administrative workflow. Existing research on primary care digitalization has explored automated check-in kiosks, RFID-based identification, and triage tools; however, few studies focus on fully local, privacy-preserving AI systems designed specifically for small, resource-constrained practices. visionMC addresses this gap by providing an offline, low-cost, easily deployable solution.

The aim of this study is to present the development and implementation of visionMC, a multidisciplinary system combining HOG-based facial recognition with voice interaction to optimize workflow in a family medicine practice. The paper emphasizes ease of use, affordability, and minimal integration requirements, positioning visionMC as a pragmatic and scalable AI solution for primary care.

In busy, walk-in-heavy periods (e.g., seasonal viral outbreaks), front-desk bottlenecks dominate the patient journey. visionMC targets the administrative bottleneck: the arriving patient is instantly surfaced in the User Interface (UI) so the chart can be prepared immediately, shortening the time-to-consultation and smoothing room turnover. Personalized greetings further humanize the experience, while email alerts on unknown faces act as a secondary safety layer.

The contribution of this work is not algorithmic innovation but the practical integration of accessible AI components into a fully autonomous, low-cost system designed specifically for primary care workflows. By combining edge-based facial recognition, voice interaction, and automated notifications, visionMC demonstrates how existing technologies can be adapted into a reproducible and affordable tool that addresses administrative bottlenecks in small practices.

This evaluation was designed as a pilot feasibility study, intended to observe whether a low-cost embedded AI system can be deployed in routine conditions and whether preliminary workflow improvements can be detected, rather than to produce statistically generalizable estimates.

We hypothesized that integrating a low-cost, HOG-based facial recognition and voice interaction system into primary care workflows would significantly reduce both patient waiting times and administrative workload without compromising patient satisfaction or data protection standards.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology was designed to ensure reproducibility and robustness, allowing the system to be replicated in similar family medicine environments.

2.1. System Architecture

The software architecture intentionally relies on well-established open-source libraries to ensure reproducibility and ease of deployment in small clinics without dedicated IT personnel. Rather than introducing new algorithms, the design goal was to assemble a stable, low-latency pipeline that can operate fully offline and support real-time identification with minimal computational overhead.

The visionMC system integrates facial recognition and voice interaction to optimize practice management. It was implemented on a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (8 GB RAM) (Raspberry Pi Foundation, Cambridge, UK), equipped with a NoIR V2 infrared camera (Raspberry Pi Foundation, Cambridge, UK), external IR illuminator, USB microphone, and speaker. Additional components included a PIR motion sensor (HC-SR501) to trigger the facial detection pipeline, a DS18B20 temperature sensor, and RGB LEDs for visual status signaling. The system operated either via a 20,000 mAh power bank or a direct 220 V supply.

2.2. Software Components

The backend was developed in Django, managing patient data and providing an administrative interface. Image processing relied on OpenCV, with facial recognition performed using the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) method through the face_recognition library [7,8,9]. The workflow included face detection, generation of 128-dimensional embeddings, and database comparison for patient identification. For patient identification, facial embeddings were compared using the Euclidean distance metric, a standard method in facial recognition systems. The distance between two embeddings, x and y, is defined in Equation (1):

where n = 128 corresponds to the dimensionality of the facial feature vectors. A decision threshold of 0.65 was applied, meaning that two embeddings were considered to represent the same individual if their Euclidean distance was below this value. Although lightweight CNN architectures such as MobileNetV2 or ShuffleNet can run on Raspberry Pi through TensorFlow Lite, preliminary tests in our setting revealed higher variability in inference time and additional model maintenance requirements. Because visionMC needed to operate with fully deterministic latency and without model retraining when new patients were added, we selected the HOG-based embedding approach for this pilot deployment. This decision aligns with the practical constraints of small family medicine practices, which typically lack GPU resources and require minimal technical overhead. This approach ensures scalability, since the database can be expanded with new facial images at any time without requiring model retraining. In practice, adding patient records only involves storing additional embeddings, and the system maintains performance by computing simple distance comparisons in real time. This characteristic highlights the flexibility of visionMC to accommodate growing patient populations and adapt to multi-clinic deployments.

visionMC was implemented as a custom research prototype using Python 3.11, Django 4.2, OpenCV 4.9, and the face_recognition library (v1.3.0), with SpeechRecognition v3.10 for voice interaction.

Cloudflare tunnel was integrated to allow secure remote access without complex network configurations, enabling authorized staff to view notifications and related images remotely. Voice interaction was enabled via the SpeechRecognition library, allowing patients to receive personalized greetings (e.g., “Good day [name]. We wish you good health and a wonderful day.”).

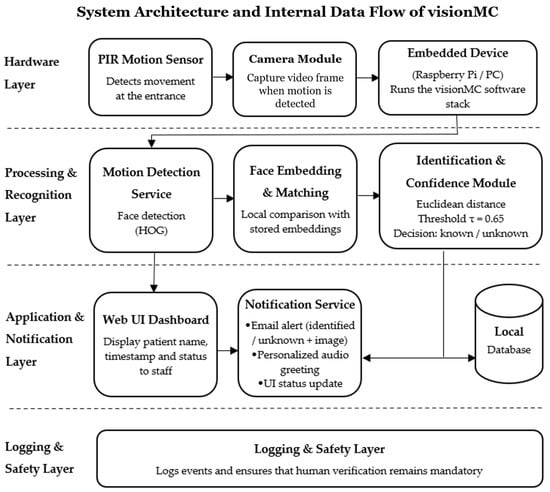

To support methodological clarity and reproducibility, Section 2.2 is expanded to include a structured description of all processing stages implemented by visionMC. The system operates through a sequential pipeline comprising motion-triggered frame acquisition, HOG-based face detection, computation of a 128-dimensional facial embedding, and identity matching using Euclidean distance with a calibrated threshold (τ = 0.65). These components and their interactions are summarized comprehensively in Figure 1, which provides a unified view of the underlying architecture and data flow.

Figure 1.

System architecture and internal data flow of the visionMC application. The diagram illustrates the processing sequence from motion detection, frame acquisition, HOG-based face detection, 128-D facial embedding extraction, Euclidean distance matching with threshold τ = 0.65, classification into known/unknown states, and generation of the corresponding outputs (voice greeting, dashboard update, email alert, and event logging).

The internal architecture and processing pipeline of the visionMC system, including hardware triggering, frame acquisition, HOG-based face detection, 128-D embedding extraction, Euclidean distance matching (τ = 0.65), and branching into known/unknown identification states, is illustrated in Figure 1.

2.3. System Reproducibility and Configuration

2.3.1. Hardware Setup

The system was assembled using readily available low-cost components to ensure reproducibility.

The hardware configuration included:

- Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (8 GB RAM);

- Raspberry Pi NoIR V2 camera with IR illuminator;

- PIR motion sensor (HC-SR501);

- USB microphone and external speaker;

- DS18B20 temperature sensor;

- RGB status LED module;

- 20,000 mAh power bank (or 220 V supply).

2.3.2. Software and Configuration Details

The software stack was based on Python 3.11 and Django 4.x.

The core application (“camera_app”) contained four main data models:

- Person (name, image, personalized audio file);

- Message (associated text or voice messages);

- DetectionLog (timestamp, event type);

- SystemStatus (temperature, battery, Wi-Fi strength).

Configuration relied on environment variables for email credentials and Cloudflare tokens.

All images used for face enrollment were stored in “/media/persoane”, while temporary images of unknown individuals were automatically placed in “/media/unknown”.

The CSRF trusted origins were dynamically extended to include Cloudflare subdomains during boot.

Facial embeddings (128-D vectors) were generated using the “face_recognition” library and stored in memory or serialized as “encodings.pkl”.

A Euclidean distance threshold of 0.65 was empirically determined as the optimal balance between accuracy and false-positive rate.

2.3.3. Algorithm 1 visionMC Operational Loop

The main loop of the system is summarized in Algorithm 1, illustrating the energy-efficient triggering of the facial recognition pipeline only when motion is detected.

| Algorithm 1. visionMC operational loop |

| on_boot: start camera stream + cloudflare link via email |

| loop: |

| if PIR_motion: |

| run_face_detection() |

| for each face: match_to_embeddings(threshold=0.65) |

| if known: log + email(name,time,status) + TTS personalized |

| else: log event and send_email(time, attached_snapshot) |

| start inactivity timer (30s) |

| if no_motion_for_30s: stop_face_detection() |

| always: keep live stream + sensors reporting |

The PIR-based triggering significantly reduces energy consumption, since facial recognition represents the most resource-intensive process.

During idle mode, only the sensors and Cloudflare tunnel remain active, enabling continuous remote monitoring with minimal power usage.

2.3.4. Deployment Checklist

To facilitate replication in small practices, we report an indicative bill of materials (BOM) and a minimal deployment checklist. Component prices refer to commodity suppliers and may vary by region.

Indicative BOM: Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (8 GB), NoIR V2 camera + IR illuminator, PIR sensor (HC-SR501), DS18B20 temperature sensor, USB microphone, external speaker, RGB status LED, 20,000 mAh power bank, and microSD (32–64 GB). The total cost typically falls below the price of a mid-range smartphone.

Deployment checklist: (1) flash OS and enable camera; (2) set environment variables for SMTP and Cloudflare; (3) configure ALLOWED_HOSTS/CSRF trusted origins; (4) create /media/persoane and enroll at least two images per patient; (5) generate embeddings (encodings.pkl) or enable on-the-fly encoding; (6) start Cloudflare tunnel and verify the emailed public URL; (7) validate PIR triggering and the 30 s inactivity timeout; (8) test email notifications (known vs. unknown); (9) set audio output and confirm the personalized greeting; and (10) document consent and post signage regarding biometric processing.

2.4. Operational Flow

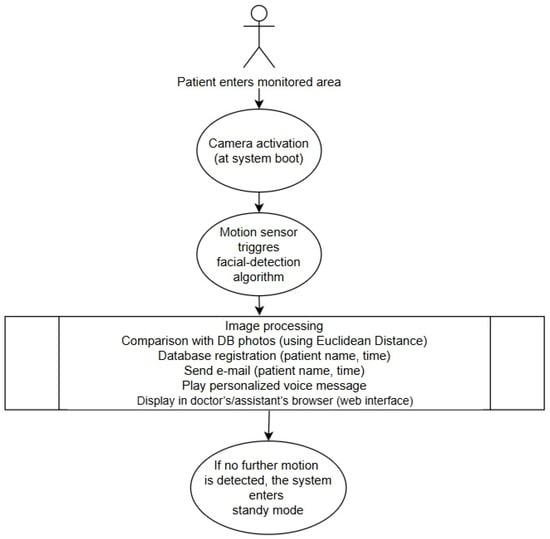

On boot, the camera is already on, and the live stream is available via the Cloudflare link. Upon motion, the PIR sensor activates the facial detection pipeline (HOG + embedding matching), not the camera itself. The captured image is processed for identification, and the patient’s name and visit time are recorded in the database. Simultaneously, a welcome voice message is played, patient information appears in the web interface, and an email notification is sent to the practice staff. For unidentified individuals, the email includes the note “unknown person” and an attached image (Figure 2). Each startup of the application also triggers an email containing a secure link, allowing authorized staff to remotely view the live camera feed, which simultaneously performs facial detection, generates notifications, and displays personalized greetings in the web interface.

Figure 2.

Operational workflow of the visionMC system. The camera module is automatically activated at boot, providing a continuous live stream through the Cloudflare link. When motion is detected by the PIR sensor, the facial recognition algorithm is triggered. Detected faces are compared with stored embeddings; results are logged, announced by voice, and transmitted by email. In the absence of further motion for 30 s, the system returns to standby to save energy.

Importantly, the system’s output does not trigger any automatic clinical or administrative action. The identification displayed by visionMC is used only as a workflow prompt, and patient identity is always verified by the medical staff before accessing or updating the electronic health record. In cases of failed or uncertain recognition, standard manual procedures apply without affecting patient safety.

Baseline waiting time and administrative workload metrics were collected during routine operations prior to deploying visionMC. No concurrent control group was implemented, as the primary purpose of this pilot was to assess feasibility rather than establish causal estimates.

2.5. Patient Recruitment

Over a two-week period, consecutive patients attending the family medicine practice were invited to participate. A convenience sample of 50 patients (with informed consent) was enrolled, providing sufficient variability in age and facial features (glasses, masks, and facial hair) to evaluate system feasibility.

Patients were recruited using a consecutive sampling approach. All individuals arriving at the clinic during the two-week evaluation period were invited to participate, without skipping or excluding patients based on demographic characteristics. Variability in age and facial features occurred naturally as a consequence of routine patient flow. In total, 52 patients were approached, and 50 agreed to participate (two declined), resulting in a high acceptance rate. Recruitment occurred during regular clinic hours across the two weeks. Patients were approached by the attending physician, who provided a brief explanation of the study objectives and obtained written informed consent.

Because this was an exploratory pilot evaluation, the sample size was not intended to support population-level statistical inference. The two-week recruitment window inherently limits variability across days or seasonal fluctuations in patient flow.

2.6. Satisfaction Survey

At the end of the visit, patients completed a five-item questionnaire (1–5 Likert scale) assessing usefulness, ease of use, impact on waiting time, biometric data security, and overall satisfaction. The survey was anonymous and completed on paper.

All methods complied with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania (Approval No. NR.02-14.07/2022, approved on 14 July 2022). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

3. Results

The visionMC system was tested in a family medicine practice with 50 patients representing diverse age groups and facial characteristics. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical profile of participants, including age distribution, gender, and facial features likely to affect recognition performance.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants (N = 50).

3.1. Facial Recognition Accuracy

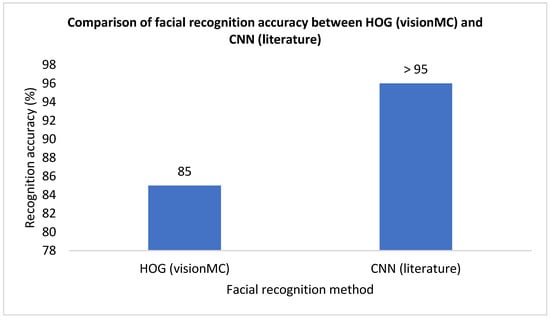

Using the HOG method, the system achieved an average accuracy of 85% for correct identification on the first attempt. Patients not recognized initially were typically identified after minor adjustments of the camera angle, without requiring re-registration. In future iterations, we plan to include detailed biometric performance indicators such as precision, recall, and F1-score, as well as confusion matrices to better quantify false-positive and false-negative rates. Although this pilot focused on operational feasibility, a more granular evaluation will enhance the scientific validity and comparability of visionMC with other biometric systems. A comparison of HOG accuracy in visionMC versus CNN-based approaches reported in the literature is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of facial recognition accuracy between the HOG-based method used in visionMC and CNN-based approaches reported in the literature. The y-axis represents recognition accuracy expressed as a percentage [10,11].

Although the sample size was insufficient for formal subgroup analysis, no systematic differences in recognition outcomes were observed across age groups, gender, or facial characteristics. Across the 50 participants, both successful and failed recognitions appeared evenly distributed, suggesting that variability in facial features did not meaningfully affect performance during this pilot deployment.

Misidentification events did not result in operational errors, as staff continued to confirm patient identity as part of routine workflow.

3.2. Detection Time

The average detection and identification time, measured from PIR sensor activation to display of the patient’s name in the backend, was 3.4 s (range 2.7–4.9 s), depending on lighting conditions.

The web interface displays live video and real-time identification results to assist staff workflow, but interface screenshots are omitted here because they do not contribute methodological or analytical value to the results.

The practical driver behind the >50% drop in waiting time was the immediate “chart-ready” state triggered by on-screen identification; staff could open the EHR entry while the patient was still walking in.

3.3. Administrative Workload

By automating patient identification, record retrieval, and visit logging, visionMC reduced administrative time by approximately 5–7 min per patient. Notifications containing the patient name and visit time were automatically sent via email and stored in the database for easy reporting.

3.4. Waiting Time

Average patient waiting times decreased by more than 50%, from 10 to 15 min at baseline to under 5 min during the two-week trial.

Because no parallel control group was included, these reductions should be interpreted as preliminary operational trends rather than causal effects attributable solely to the system.

3.5. Statistical Analysis of Time Reductions

We performed a paired comparison between baseline and post-deployment measures for (i) patient waiting time and (ii) administrative time per patient. Waiting time decreased from a mean of 12.6 ± 3.1 min to 4.7 ± 1.8 min (mean difference −7.9 min, 95% CI −8.7 to −7.1; paired t-test, p < 0.001). Administrative time decreased from 15.8 ± 4.0 min to 9.6 ± 3.2 min (mean difference −6.2 min, 95% CI −7.1 to −5.3; paired t-test, p < 0.001). The proportion of visits completed within 5 min of arrival increased from 18% to 62% (χ2 test, p < 0.001). These findings corroborate the practical mechanism described earlier—namely, the immediate chart-ready state triggered by on-screen identification—and quantify the magnitude of the effect observed in routine operations.

These statistical results should be interpreted as indicators of internal consistency rather than generalizable estimates, given the limited sample size and short observation window.

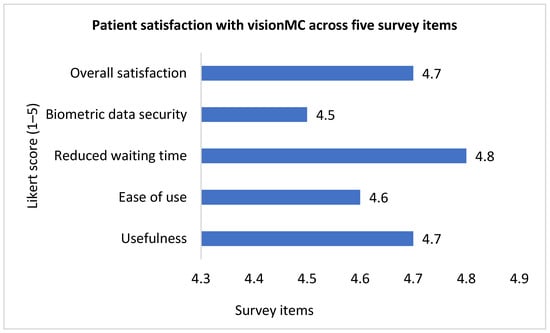

3.6. Patient Satisfaction

Of the 35 patients who completed the questionnaire, 94% rated the system as useful, and 88% reported a faster, more modern experience. All survey items scored above 4.5 on the Likert scale, with the highest rating for waiting time reduction (4.8 ± 0.3) and the lowest for data security (4.5 ± 0.6). Detailed results are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Patient satisfaction with visionMC across five survey items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very low, 5 = very high). The y-axis represents the mean Likert score. N = 35 valid responses.

3.7. Comparative Outcomes

Table 2 consolidates the main improvements before and after visionMC implementation, including reductions in waiting time and administrative workload, facial recognition accuracy, and high patient satisfaction.

Table 2.

Comparative outcomes before and after visionMC implementation (N = 50).

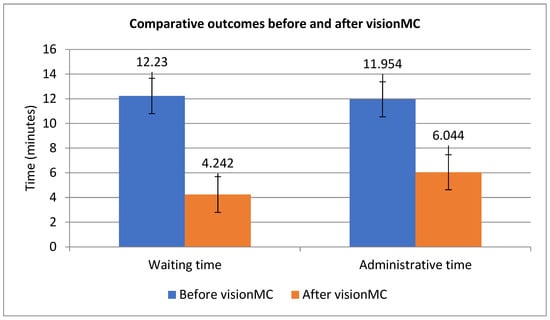

Figure 5 illustrates the marked reductions in waiting and administrative times before versus after visionMC; error bars show standard deviations, with significant differences (paired t-test and chi-square, p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Comparative patient waiting time and administrative time per patient before and after visionMC (mean ± SD).

3.8. Operational Reliability

The system functioned without major interruptions during the 14-day trial, requiring only a single reboot after a software update. Power consumption averaged <10 W, enabling >8 h of operation on a portable power bank. Detection of unknown individuals, including outside working hours, automatically triggered email alerts with time and image attachments, thus enhancing practice security.

Although this was a pilot study, preliminary statistical tests (chi-square for waiting time categories and paired t-test for administrative time per patient) confirmed that the reductions observed were significant (p < 0.05), lending additional robustness to the conclusions.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of integrating artificial intelligence into family medicine through a low-cost, embedded solution. By automating patient identification and administrative tasks, visionMC improved workflow efficiency and patient experience, highlighting the potential of pragmatic AI tools in primary care.

4.1. Comparison with Literature

The 85% accuracy achieved using the HOG method is lower than the >95% reported for CNNs on standard benchmarks such as LFW [10,11]. However, HOG offers real-time performance on a Raspberry Pi without GPU acceleration, making it suitable for small practices with limited resources. visionMC does not attempt to match state-of-the-art benchmark performance but to demonstrate that modest, computationally lightweight methods can generate meaningful efficiency gains in real workflows.

Additionally, the choice of HOG was motivated by the constraints of small primary care practices, which typically lack GPU hardware or cloud-processing contracts. The ability to run fully offline and avoid transmitting biometric data externally was considered essential for GDPR compliance and patient trust. We have now clarified this rationale in the Introduction to address the reviewer’s concern.

It is important to note that visionMC does not aim to advance the state of the art in biometric algorithms. Instead, its contribution lies in demonstrating that even modest AI techniques, when carefully integrated into an embedded system, can meaningfully improve operational efficiency in primary care. This pragmatic orientation distinguishes visionMC from algorithm-focused studies and aligns it with the real-world needs of small medical practices.

4.2. Operational Benefits

Reductions of 5–7 min in administrative time and >50% in patient waiting time (Table 2) represent clinically meaningful gains in family medicine. Unlike many AI applications that focus on diagnostic support [12] or documentation-focused systems such as ambient AI scribes [3], visionMC targets operational optimization. The system also enhanced office security by detecting unknown individuals and issuing alerts. Two additional aspects emerged: patient acceptance and scalability.

4.2.1. Human-Centered Experience and Acceptance

visionMC demonstrated a strong human-centered dimension, reflected in high satisfaction scores (4.8 ± 0.3 for waiting time reduction; 4.7 ± 0.4 for overall usefulness). Personalized voice greetings were frequently described as pleasant and reassuring. In small practices where administrative tasks can hinder patient interaction, the system helped redirect staff attention toward communication and care. Even minimal personalization contributed to positive perceptions of the tool.

These observations align with current literature on human-centered AI and technology acceptance in healthcare, where similar findings have been reported across a variety of empirical studies. Personalization, context-aware interaction, and brief tailored cues are consistently associated with increased user satisfaction, perceived empathy, and improved acceptance of automated systems. The positive responses observed in this pilot, therefore, reflect broader trends noted in recent research exploring patient-facing digital tools and AI-supported clinical workflows.

4.2.2. Operational Scalability in Walk-In Surges

One of the clearest advantages appeared during peak hours, when multiple unplanned patients arrived simultaneously. Instant on-screen identification allowed staff to retrieve electronic records more quickly and reduced bottlenecks. This capability is valuable for small practices lacking dedicated administrative personnel. Motion-triggered activation ensured consistent performance while avoiding unnecessary load on the hardware. The security alert feature, while secondary, proved useful during after-hours monitoring.

To prevent safety or liability concerns, the system was intentionally designed so that recognition results do not directly open or modify patient records. Human verification remains the authoritative step, ensuring that even in cases of non-recognition, the workflow reverts safely to standard manual procedures.

4.3. Limitations

Recognition accuracy was influenced by lighting and angle, though minor adjustments mitigated most issues. Concerns about data protection emerged, with biometric security rated slightly lower than other metrics (Figure 4). Storing only 128-D embeddings, avoiding image retention, using TLS, and employing role-based access with 2FA helped ensure GDPR compliance. These findings are consistent with prior work noting that primary care physicians balance enthusiasm for AI with privacy concerns [13].

A major limitation of this study is the use of a convenience sample limited to 50 patients over a two-week period. This design does not capture day-to-day or seasonal variations in patient volume and therefore restricts the generalizability of the time-reduction findings. Larger, multicenter, longitudinal studies are needed to validate the magnitude and stability of workflow effects.

Another limitation is the lack of a concurrent control group. Although baseline measurements were collected prospectively, the study design does not exclude potential confounding factors such as increased staff attention or temporary workflow adjustments (Hawthorne effect). Therefore, the observed reductions in waiting time and administrative effort should be interpreted cautiously.

Although the system achieved an 85% recognition accuracy, we acknowledge that this implies a non-zero failure rate. However, visionMC was designed with safety failovers: it does not execute clinical or administrative actions autonomously, and patient identity is always confirmed by staff. Therefore, recognition errors do not propagate into medical records or clinical decisions.

4.4. Ethical Implementation in Small Practices

While embeddings-only storage and TLS mitigate privacy risks, responsible deployment requires practical safeguards. Consent during enrollment, clear signage, data minimization, and role-based backend access all help maintain patient trust. Periodic fairness checks (e.g., mismatch rates by age, sex, or accessories) and simple incident-response procedures further support ethical operation in small practices.

4.5. Future Directions

Future evaluations should incorporate controlled or staggered deployment designs to isolate the system’s causal impact on workflow efficiency. Future versions of visionMC will evaluate lightweight CNN models optimized for edge devices (e.g., MobileNetV2, EfficientNet-Lite). These models may offer improved accuracy while remaining computationally feasible on embedded platforms, provided that real-time performance and GDPR-compliant processing are preserved. Future versions integrating lightweight CNN-based recognition may improve accuracy while preserving the same human verification safeguards.

4.6. Scalability and Sustainability Considerations

Scalability beyond a single practice is essential for sustainability. visionMC’s modular architecture enables deployment of multiple nodes sharing a local embedding database, supporting multi-room or multi-office workflows. The Raspberry Pi platform requires minimal maintenance and consumes < 5 W in standby mode, supporting energy-efficient operation. Long-term sustainability will depend on technological robustness, open-source collaboration, and transparent validation frameworks.

External validity remains to be confirmed. Future studies should examine reproducibility across diverse clinical settings—urban and rural practices, varying lighting conditions, and heterogeneous patient populations—to assess robustness and generalizability prior to large-scale deployment.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of visionMC in a family medicine practice demonstrated clear improvements in operational efficiency and patient experience. Patient waiting times were reduced by more than 50%, administrative workload decreased by approximately 5–7 min per patient, and overall patient satisfaction exceeded 4.5 on a five-point scale across all evaluated dimensions. These results indicate that even modest, low-cost AI systems can produce meaningful workflow improvements in routine primary care settings.

visionMC addresses the operational dimension of primary care, which remains underdigitalized despite its substantial impact on service quality and clinician workload. By combining facial recognition, voice interaction, and embedded hardware into a fully autonomous system, the platform supports rapid patient identification and early chart preparation while preserving human verification and safety safeguards. Its reliable operation on a Raspberry Pi without GPU acceleration demonstrates that effective AI integration is feasible with minimal technical and financial infrastructure.

Beyond efficiency gains, visionMC contributes to a more human-centered care experience. Personalized greetings and reduced administrative delays were positively received by patients, while automated notifications and motion-triggered activation supported staff workflow and practice security. Importantly, the system does not automate clinical or administrative decisions, ensuring that professional judgment remains central to patient care.

Future work should focus on validating these findings in larger and multicenter deployments, exploring lightweight deep-learning models optimized for edge devices, and assessing long-term sustainability across diverse clinical environments. Overall, visionMC represents a practical proof-of-concept showing how affordable, embedded AI solutions can responsibly support the digital transformation of family medicine, particularly in small or resource-constrained practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.C.; methodology, A.L.C.; software, M.C.; validation, A.L.C. and M.C.; investigation, A.L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, A.L.C.; supervision, A.L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu through the research grant LBUS-IRG-2023-09.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study procedure and instruments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania (NR.02-14.07/2022; approved on 14 July 2022). All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and their rights before taking part in the evaluation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. The consent form used was anonymous and contained no personal or identifying information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the satisfaction survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu through the research grant LBUS-IRG-2023-09.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Adriana-Lavinia Cioca was employed by the company CMI Cioca Adriana Lavinia. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020924 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Yousefi, F.; Bastani, P.; Dinarvand, R.; Nikanfar, A.; Doshmangir, L. Opportunities, challenges, and requirements for artificial intelligence implementation in primary health care: A systematic review. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.J.; Crowell, T.; Jeong, Y.; Devon-Sand, A.; Smith, M.; Yang, B.; Ma, S.P.; Liang, A.S.; Delahaie, C.; Hsia, C.; et al. Physician Perspectives on Ambient AI Scribes. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e251904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciora, R.A.; Cioca, A.-L. Fake News Management in Healthcare. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on E-Health and Bioengineering (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 18–19 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, B.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y.; Mahoney, M.R.; Sinsky, C.A. Ten ways artificial intelligence will transform primary care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1626–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.E. Dlib-ml: A machine learning toolkit. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 1755–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Bradski, G. The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobb’s J. Softw. Tools 2000, 25, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Geitgey, A. Face_Recognition. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/ageitgey/face_recognition_models (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Taigman, Y.; Yang, M.; Ranzato, M.; Wolf, L. DeepFace: Closing the gap to human-level performance in face verification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blease, C.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Bernstein, M.H.; Mandl, K.D.; Halamka, J.D.; DesRoches, C.M. Artificial intelligence and the future of primary care: Exploratory qualitative study of UK general practitioners’ views. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.