Heat Transfer Enhancement and Flow Resistance Characteristics in a Tube with Alternating Corrugated-Smooth Segments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

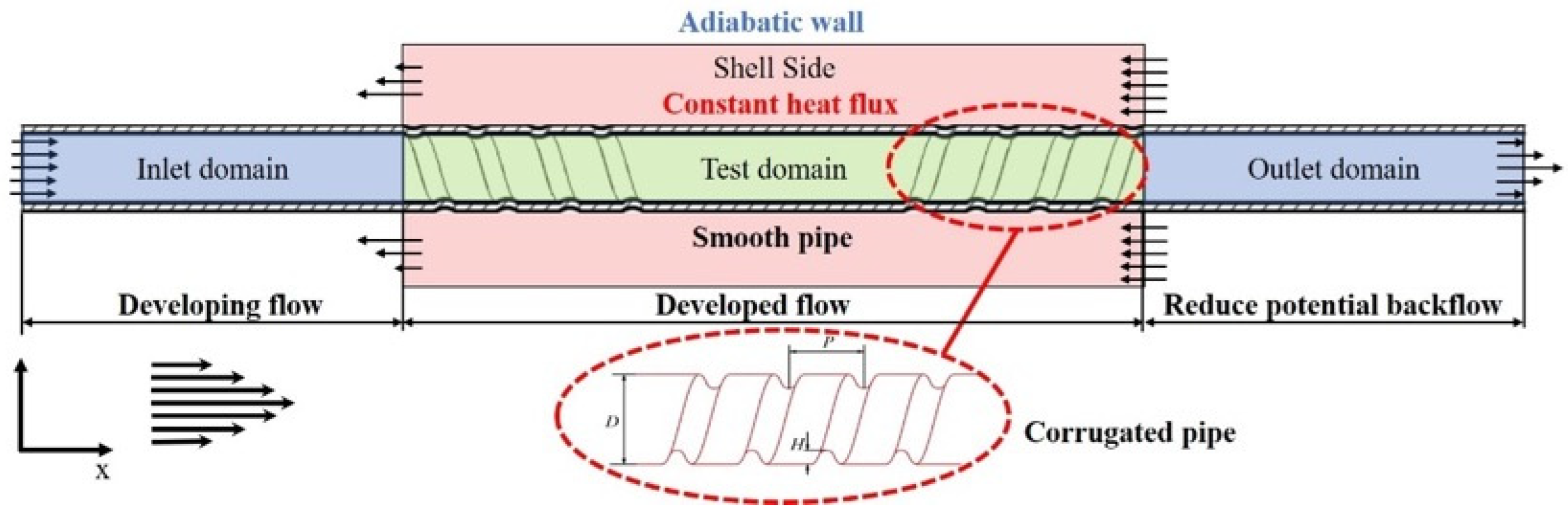

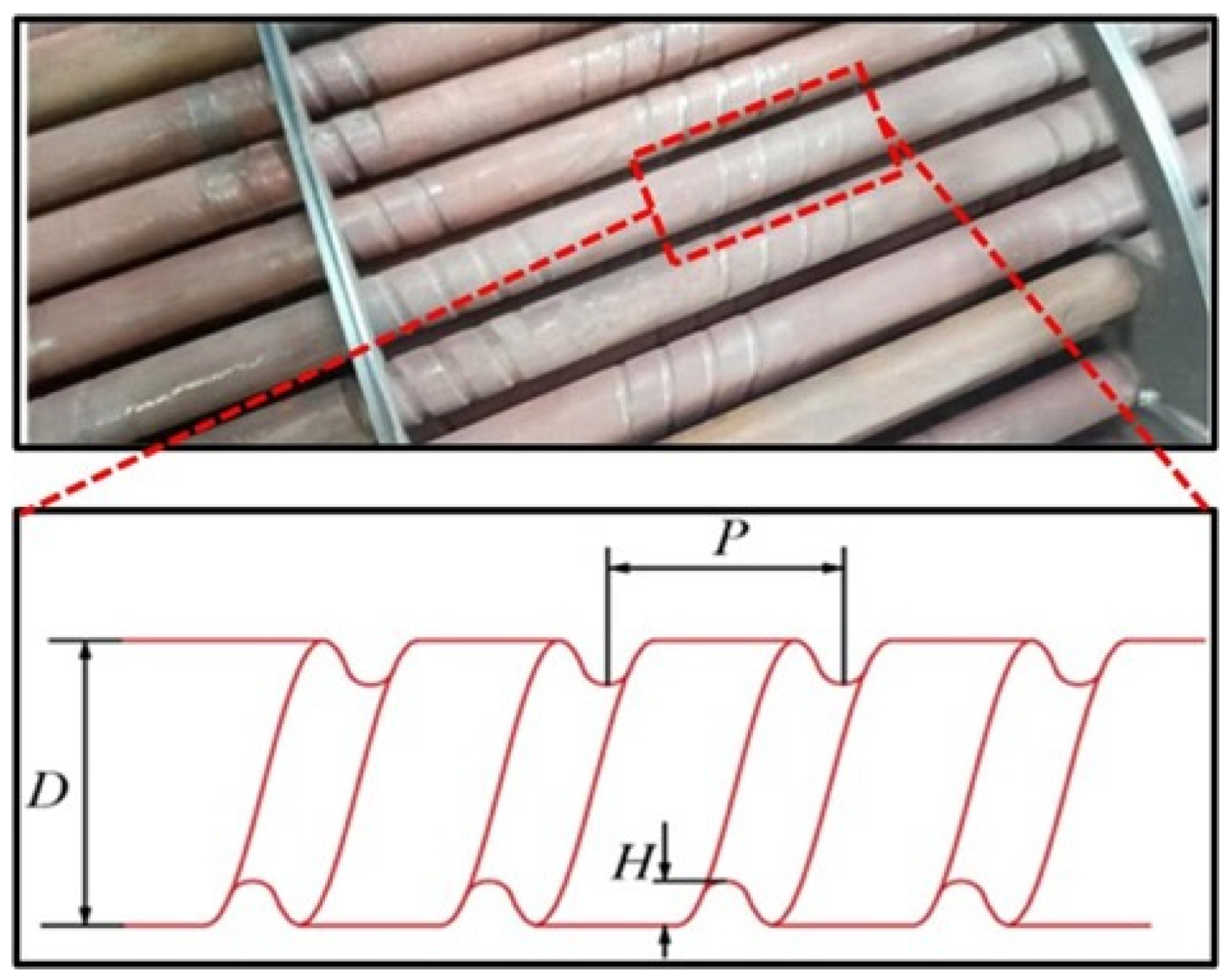

2.1. Physical Models and Boundary Conditions

2.2. Governing Equations and Data Reduction

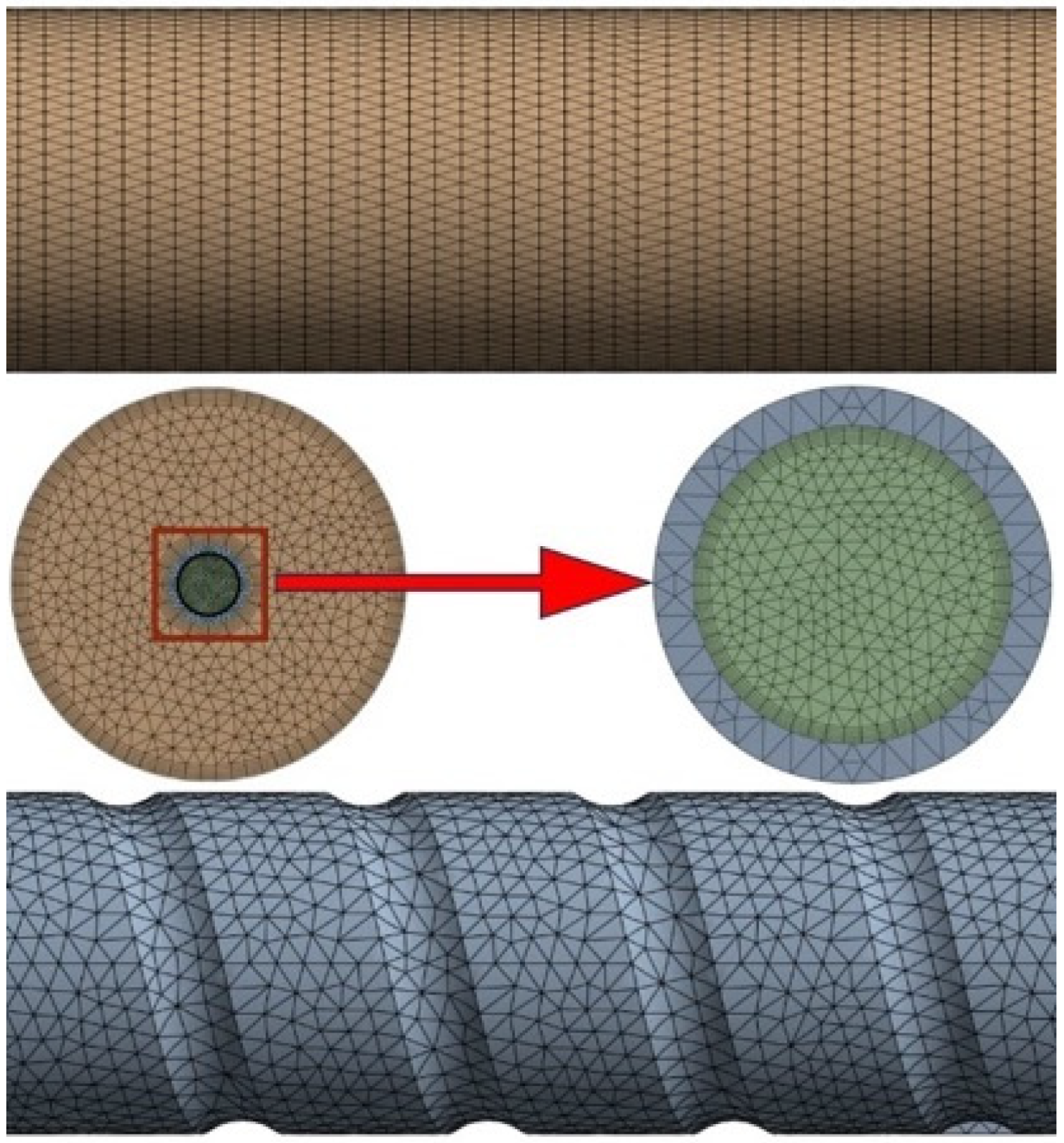

2.3. Grid Independence Analysis

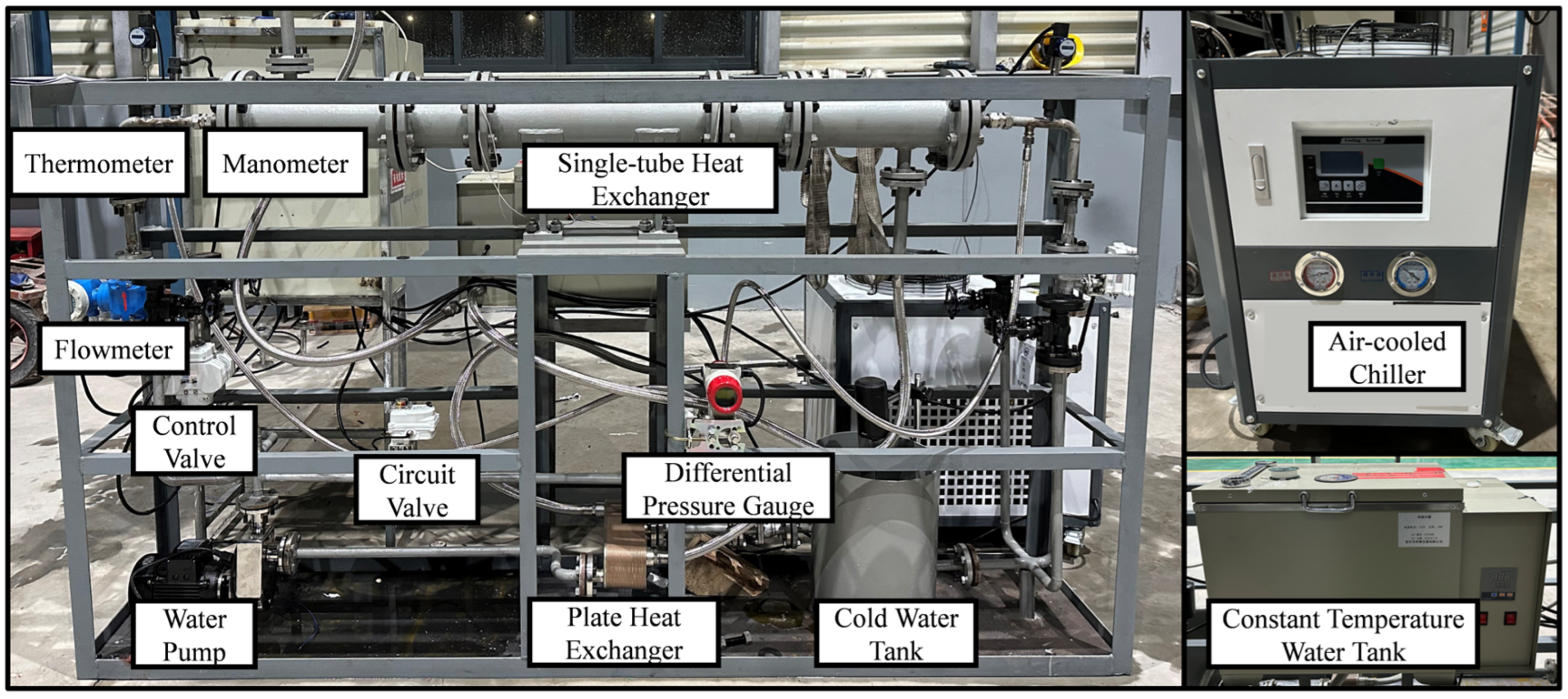

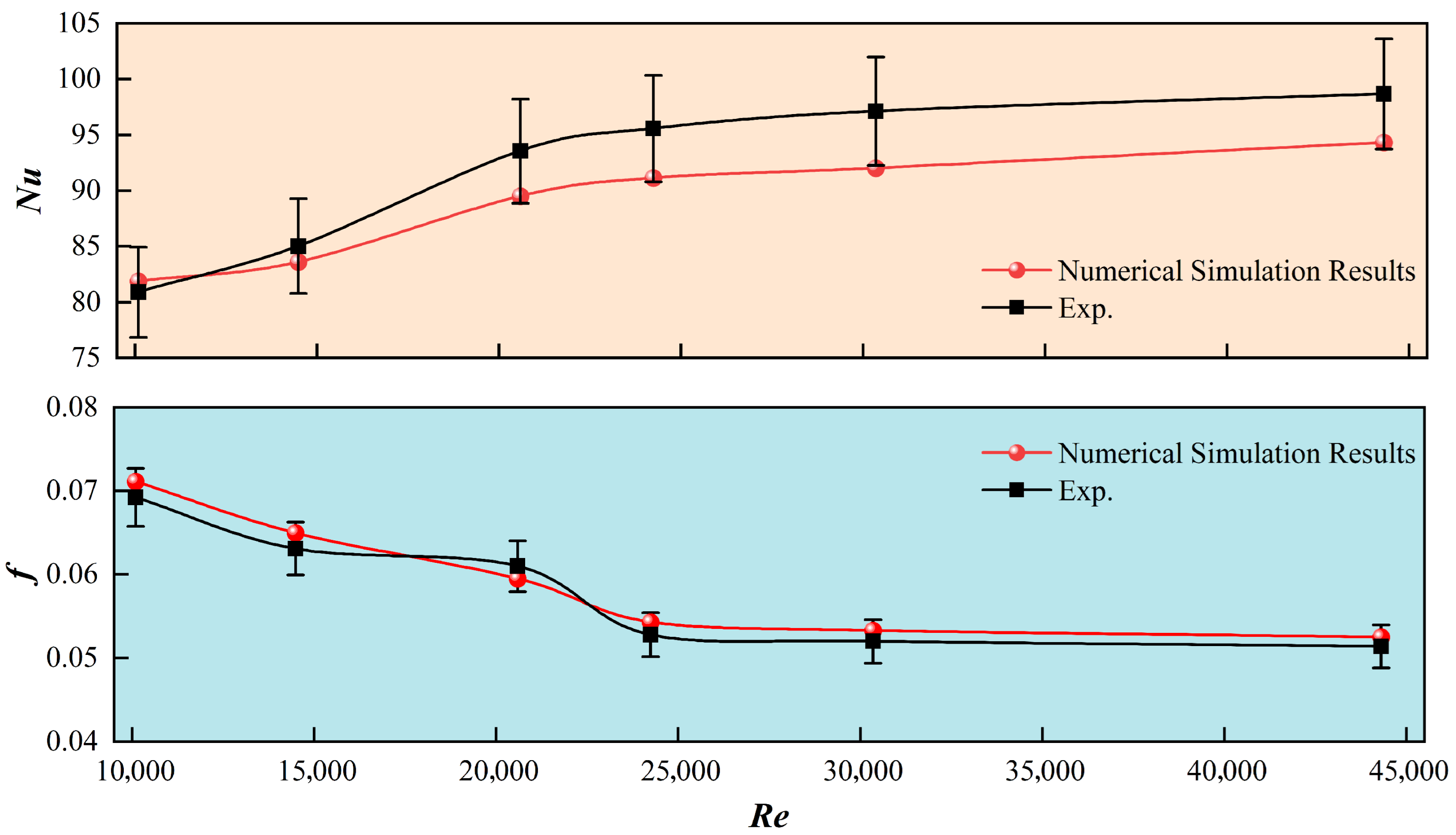

2.4. Model Validation

3. Results

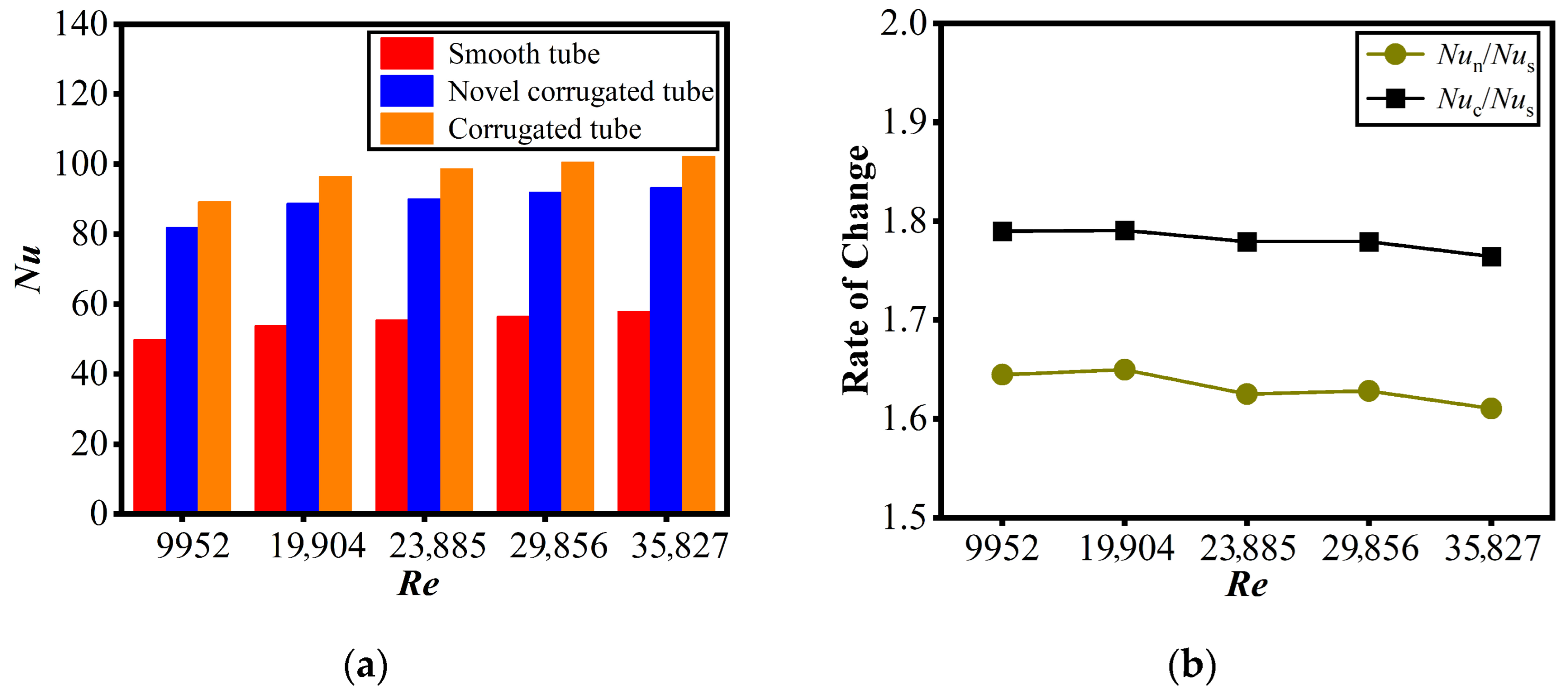

3.1. Heat Transfer Characteristics

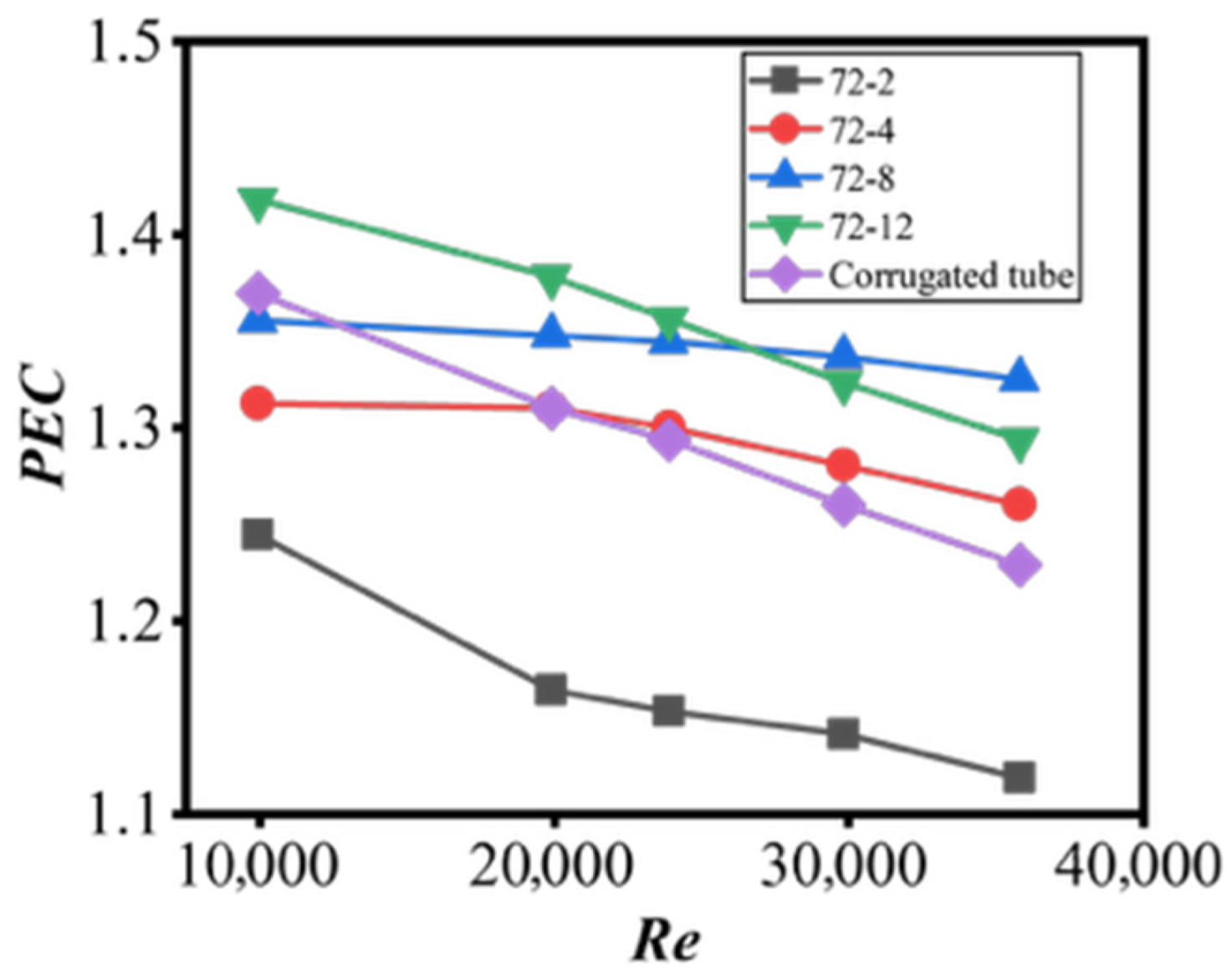

3.2. Performance Study

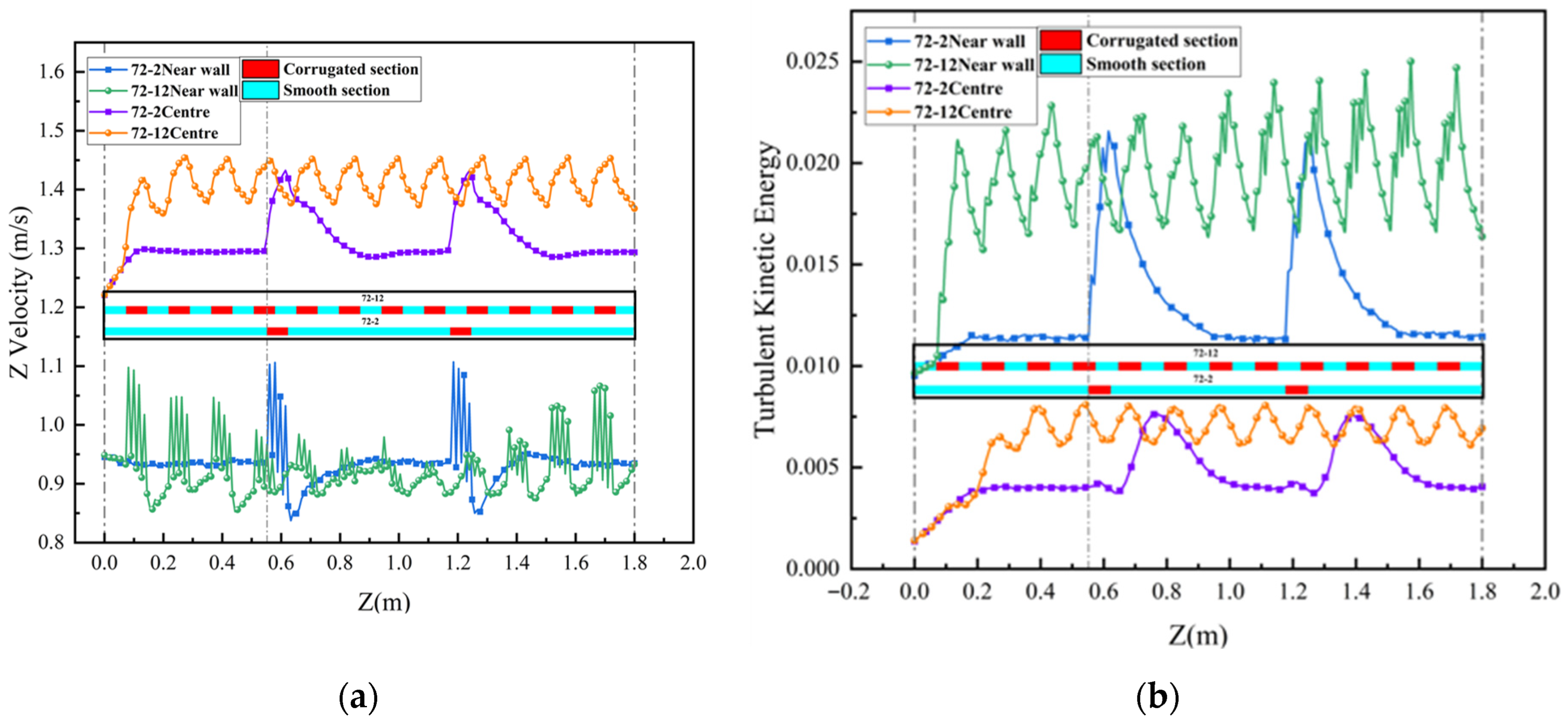

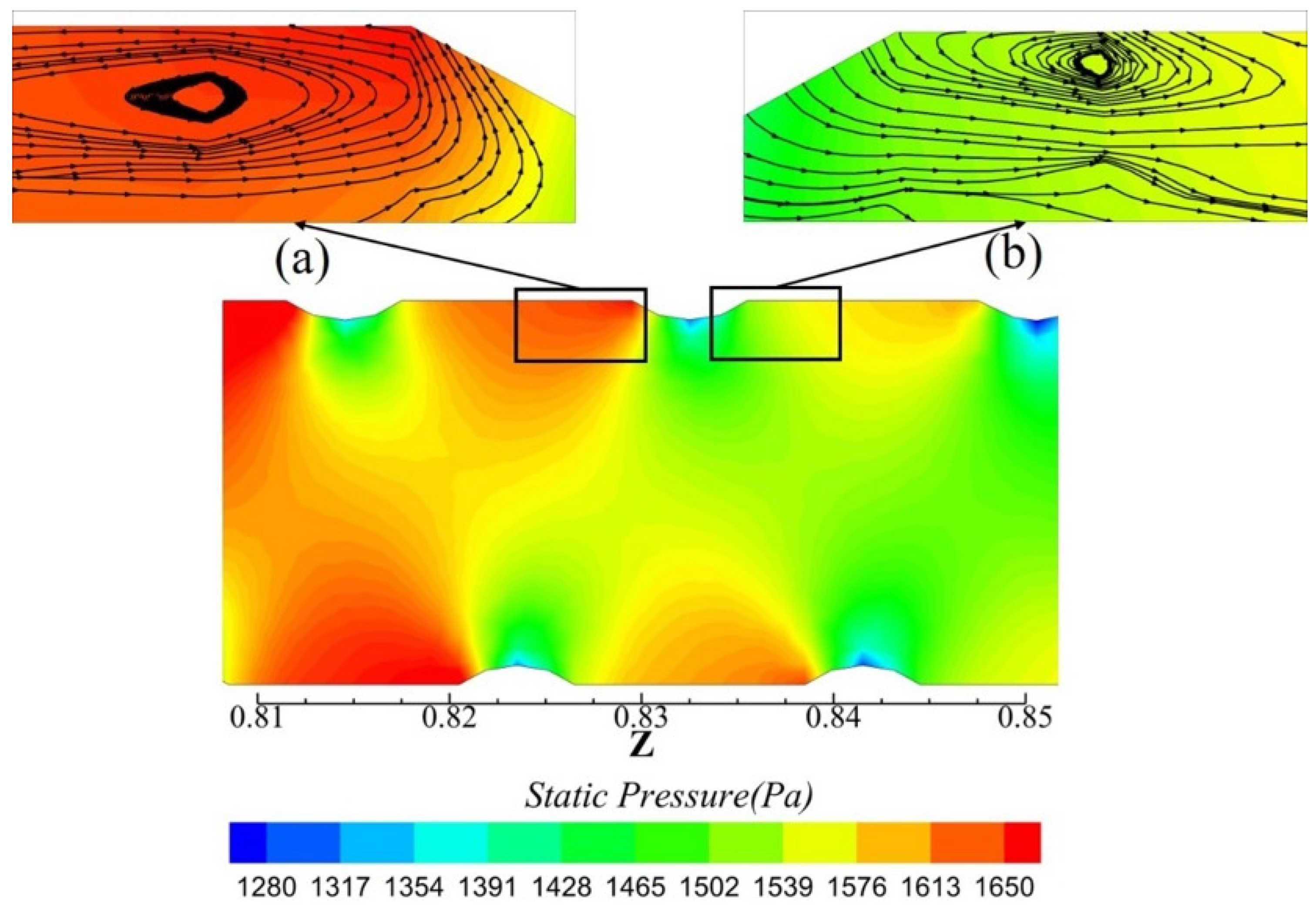

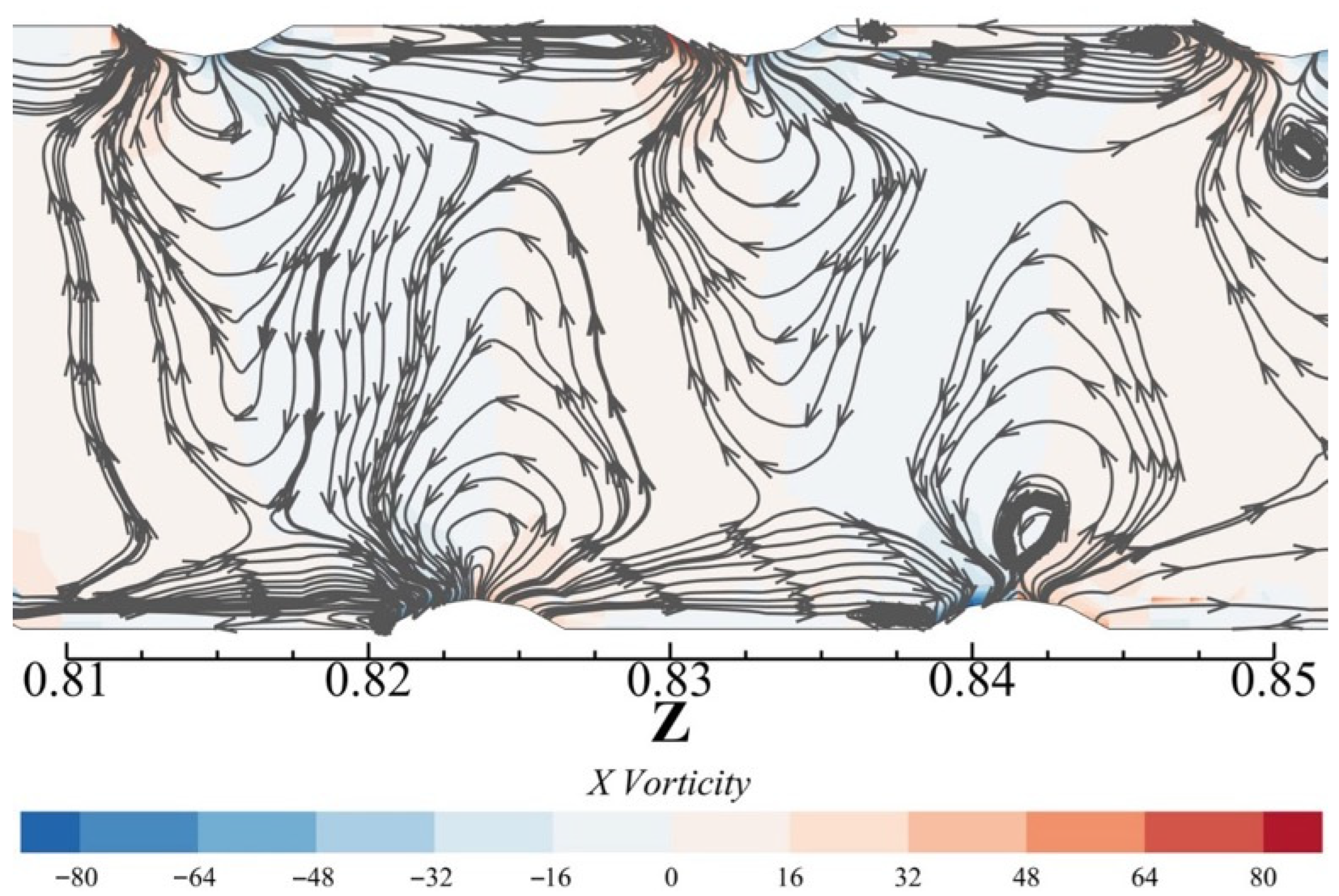

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

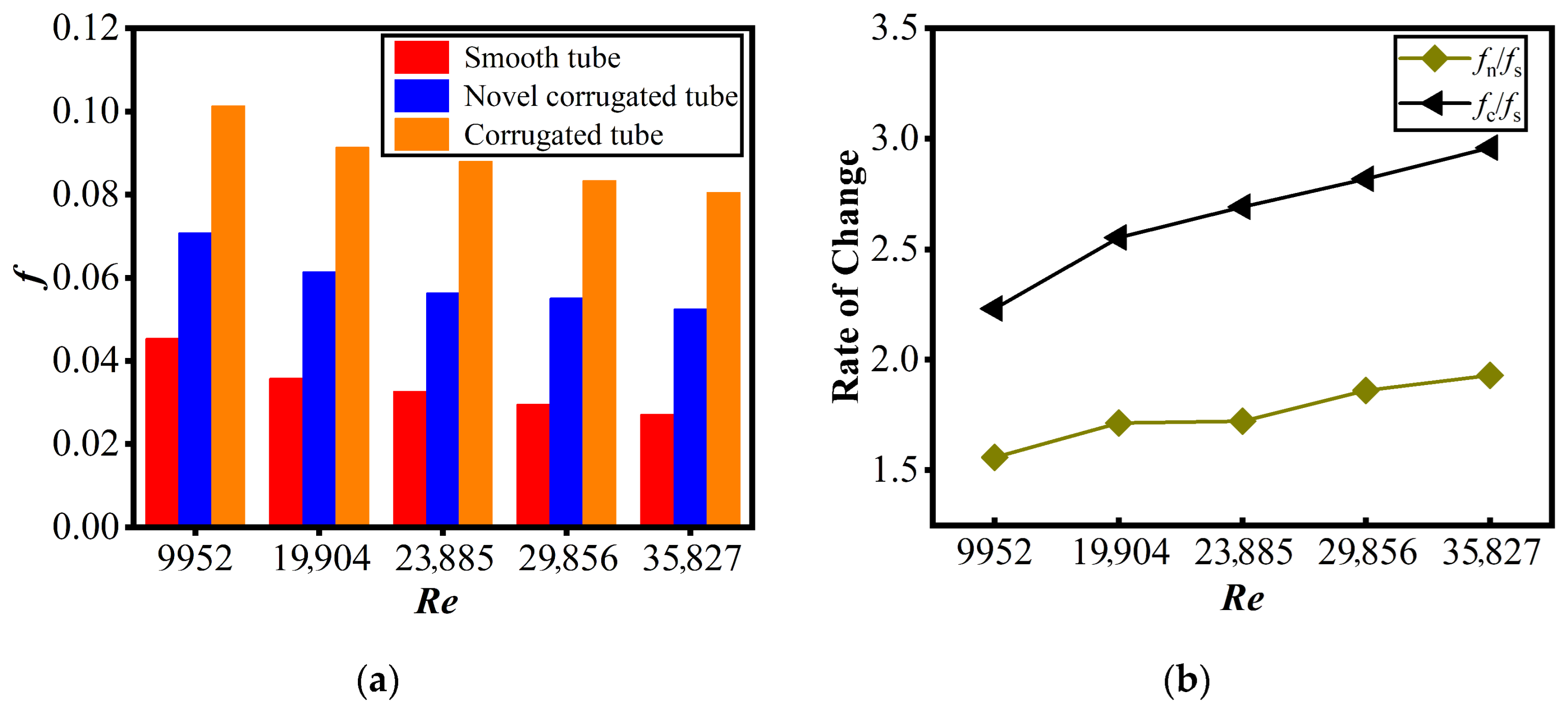

- Performance balance: The novel tube achieved a superior trade-off: it maintained substantial heat transfer enhancement (Nun/Nus ≈ 1.61–1.65) while limiting flow resistance growth (fn/fs ≈ 1.56–1.93). In contrast, the conventional corrugated tube (though achieving higher heat transfer, Nuc/Nus ≈ 1.76–1.79) incurred a steep pressure penalty (fc/fs = 2.96)—making the novel tube well-suited for pump-power-constrained scenarios.

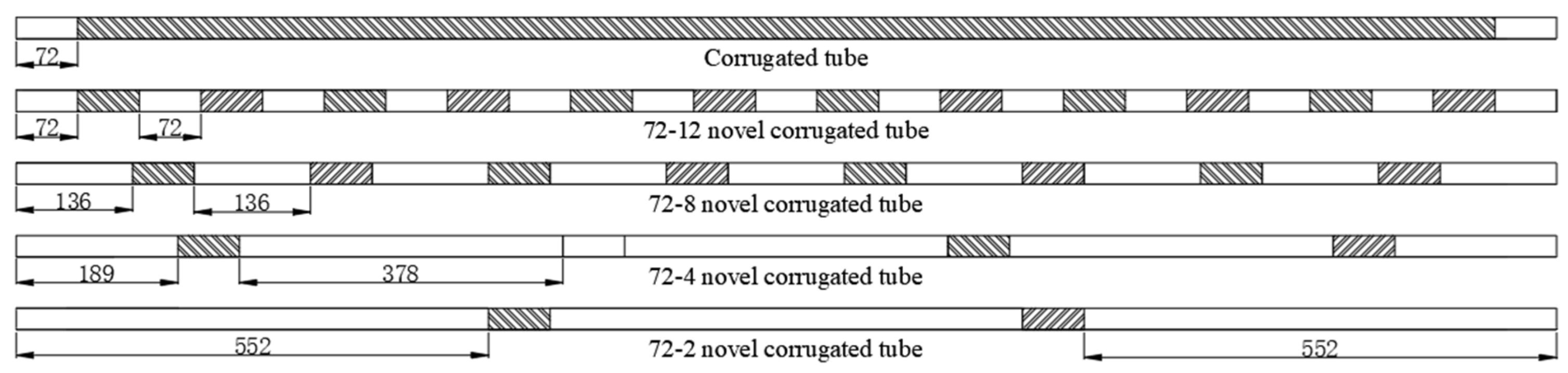

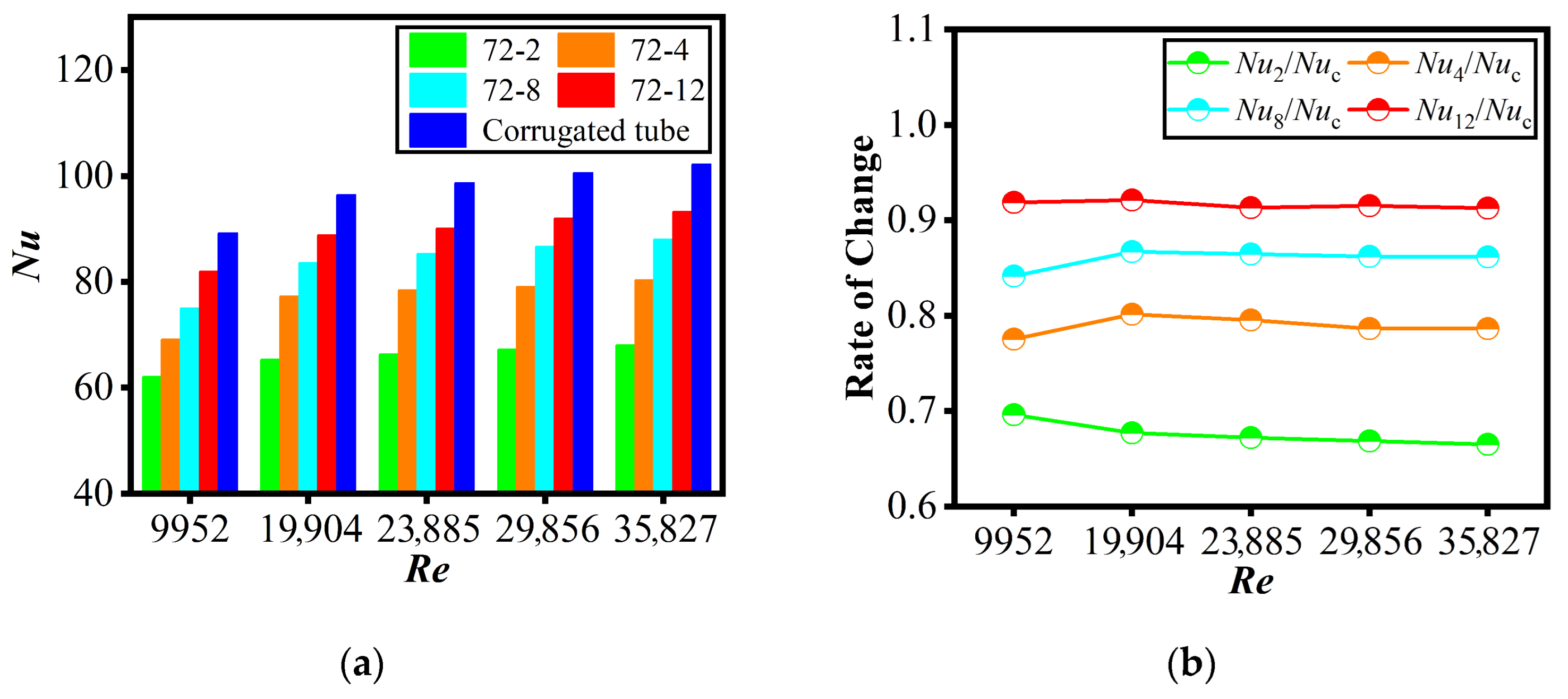

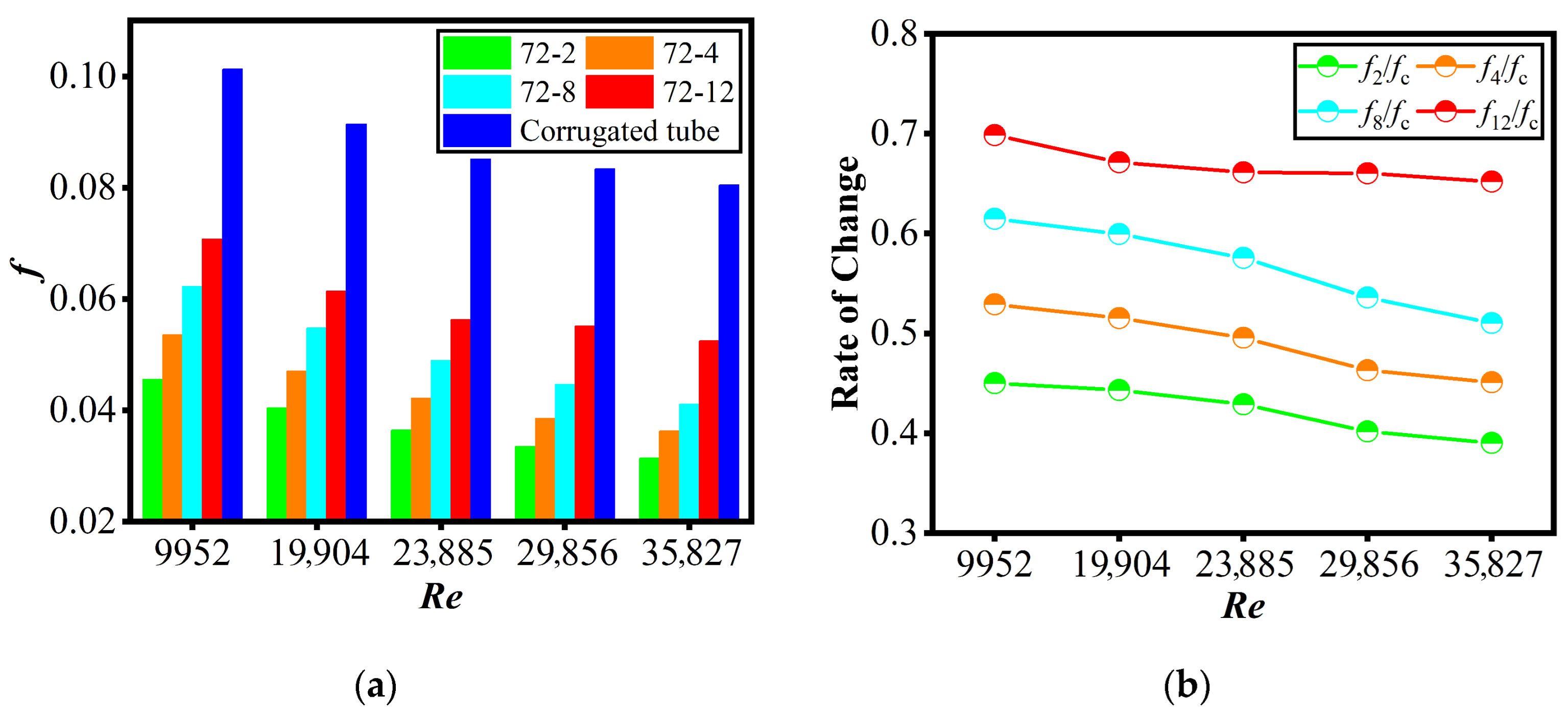

- Structural parameter effect: Corrugated segment count is a critical tunable parameter: more segments (e.g., 72-12, 72-8 configurations) boost heat transfer performance, fitting applications prioritizing high thermal efficiency; fewer segments (e.g., 72-2 configuration) reduce the friction factor by up to 40.7%, ideal for low-flow-resistance requirements.

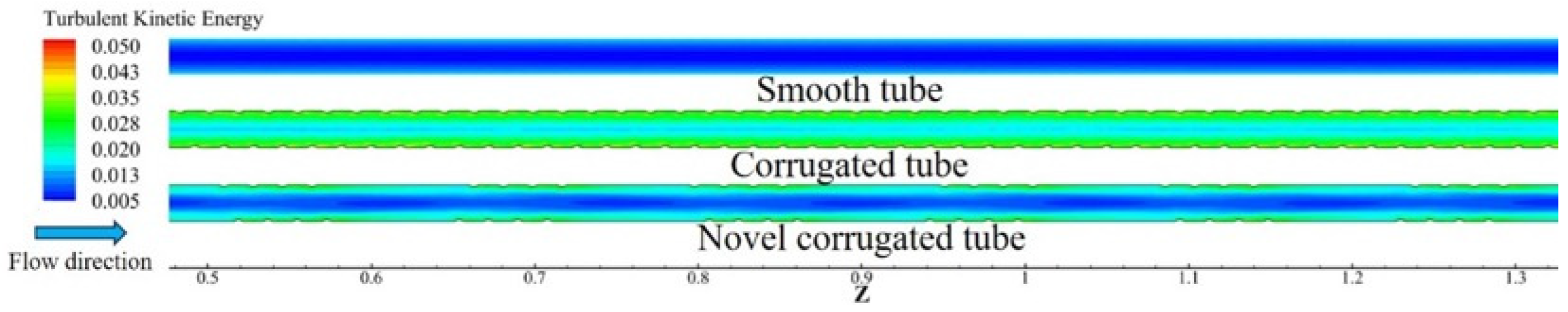

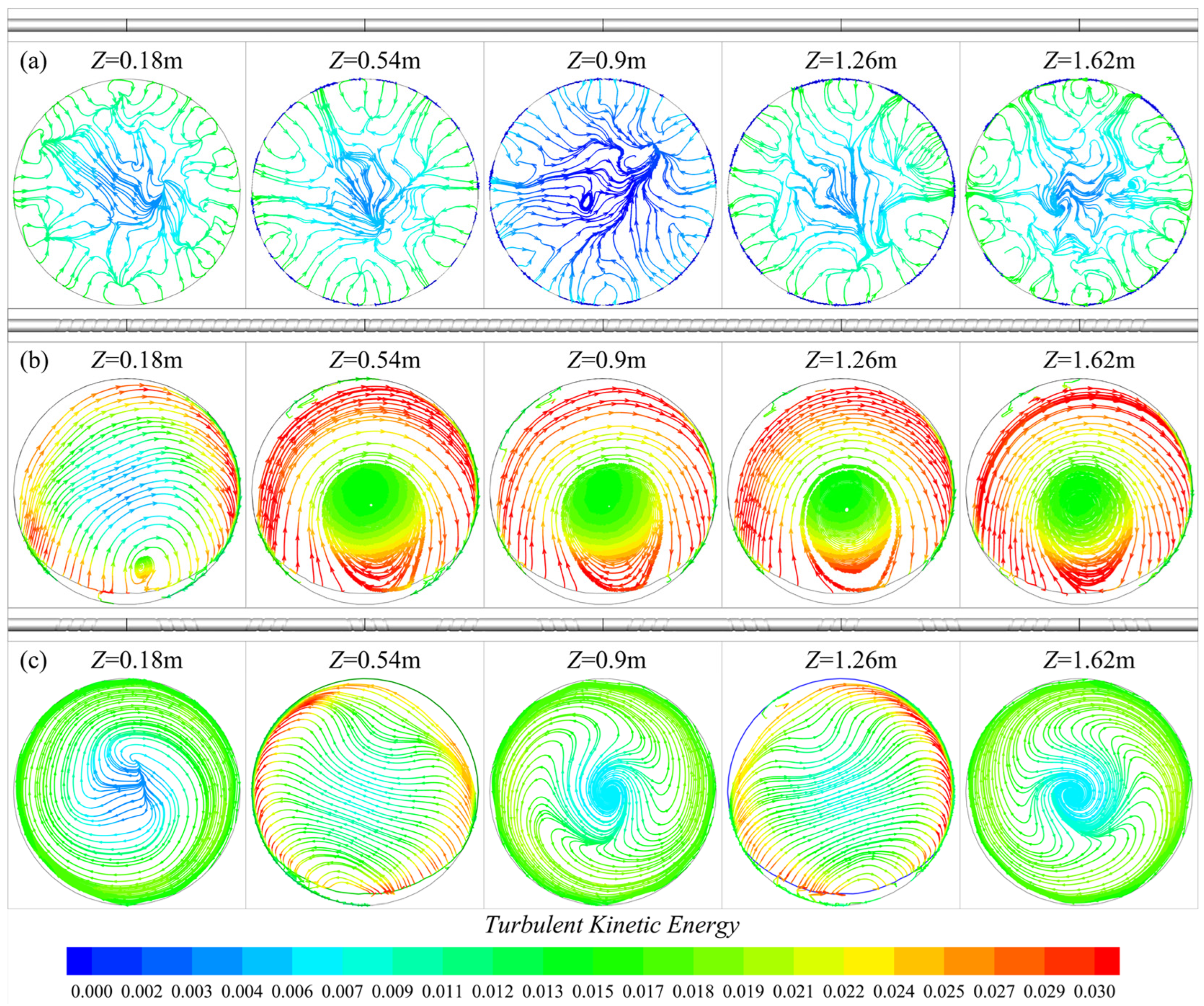

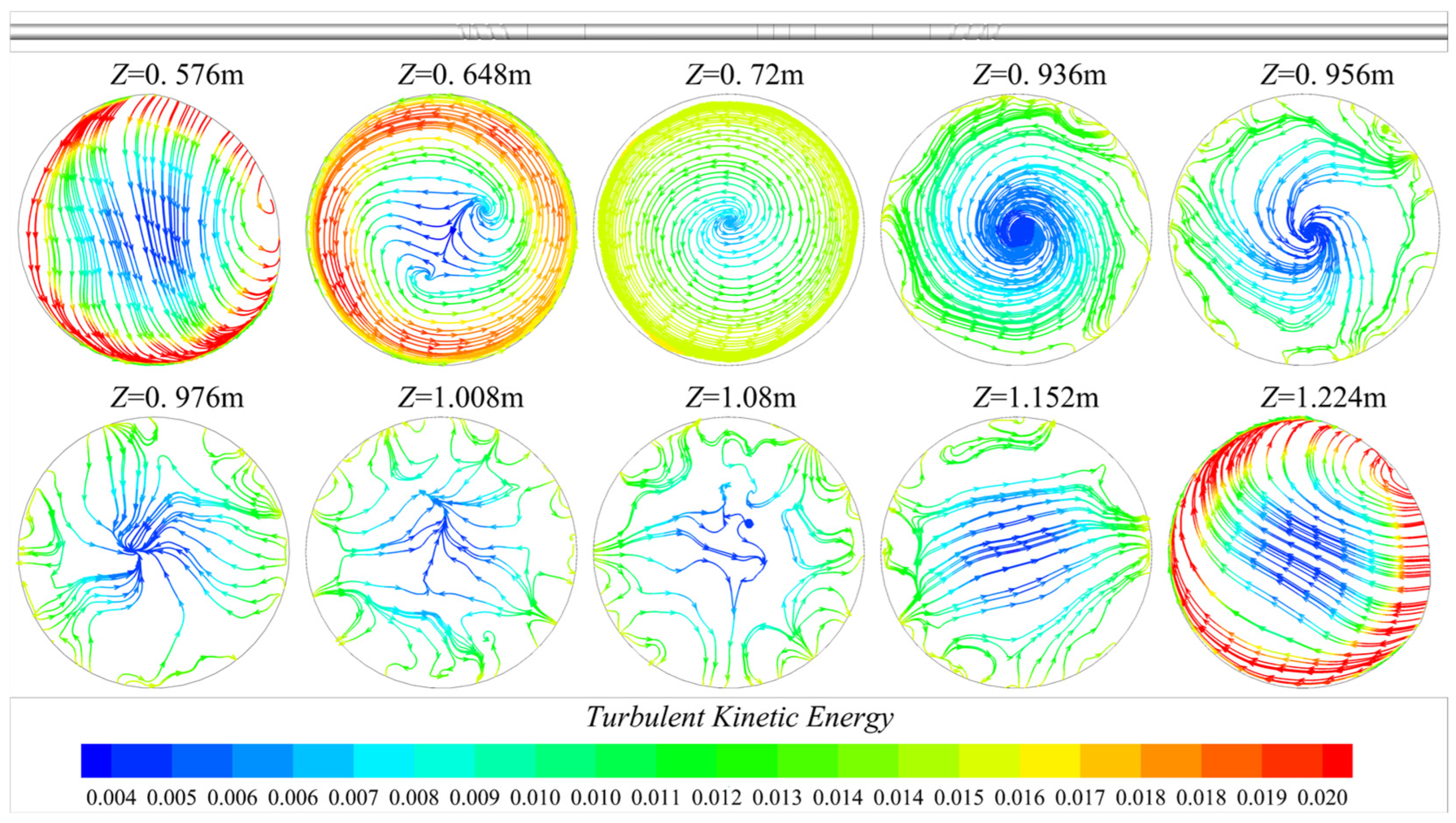

- Heat transfer mechanism: Corrugated segments act as vortex generators, periodically disrupting the thermal boundary layer, inducing secondary flows, and intensifying fluid mixing to enhance heat transfer. The novel tube’s defining innovation (smooth segments between corrugated sections) allows turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) from corrugated zones to decay and redevelop—sustaining enhanced heat transfer while avoiding the excessive, continuous pressure rise of fully corrugated conventional tubes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | |||

| cp | specific heat capacity [j·kg−1·K−1] | Subscript | |

| D | diameter [mm] | in | inlet |

| f | Friction factor [−] | out | outlet |

| H | corrugation depth [mm] | a | average |

| qm | mass flow rate [kg·s−1] | w | wall |

| Nu | Nusselt number [−] | Δ | Tube side:inlet-outlet |

| P | corrugation pitch [mm] | n | Novel corrugated tube |

| p | pressure [Pa] | s | Smooth tube |

| Re | Reynolds number [−] | c | Corrugated tube |

| T | temperature [K] | 2 | 72-2 novel corrugated tube |

| TKE | turbulent kinetic energy | 4 | 72-4 novel corrugated tube |

| h | overall heat transfer coefficient [W·m−2·K−1] | 8 | 72-8 novel corrugated tube |

| A | heat exchange area [m2] | 12 | 72-12 novel corrugated tube |

| L | heat exchange length [m] | Greek letter | |

| V | velocity [m·s−1] | ρ | fluid density [kg·m−3] |

| PEC | Performance Evaluation Criterion | μ | dynamic viscosity [Pa·s] |

| λ | thermal conductivity [W·m−1·K−1] | ||

References

- Liu, S.; Sakr, M. A Comprehensive Review on Passive Heat Transfer Enhancements in Pipe Exchangers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 19, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanavel, C.; Saravanan, R.; Chandrasekaran, M. Heat Transfer Augmentation by Nano-Fluids and Circular Fin Insert in Double Tube Heat Exchanger—A Numerical Exploration. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 21, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Z. Effectiveness of Actively Adjusting Vapour-Liquid in the Evaporator for Heat Transfer Enhancement. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 200, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirbastami, S.; Moujaes, S.F.; Mol, S.G. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Heat Enhancement in Internally Helical Grooved Tubes. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass Transf. 2016, 73, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navickaitė, K.; Cattani, L.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Engelbrecht, K. Elliptical Double Corrugated Tubes for Enhanced Heat Transfer. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 2019, 128, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.K.; Azzawi, I.D.J.; Khadom, A.A. Experimental Validation and Numerical Investigation for Optimization and Evaluation of Heat Transfer Enhancement in Double Coil Heat Exchanger. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 22, 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Li, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Xie, L. Numerical investigation of convective heat transfer enhancement by a combination of vortex generator and in-tube inserts. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass Transf. 2021, 127, 105490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celen, A.; Çebi, A.; Aktas, M.; Mahian, O.; Dalkilic, A.S.; Wongwises, S. A Review of Nanorefrigerants: Flow Characteristics and Applications. Int. J. Refrig. 2014, 44, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L.; Meyer, J.P. In-Tube Passive Heat Transfer Enhancement in the Process Industry. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2007, 27, 2713–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, Z.S.; Mohd Jaafar, M.N.; Lazim, T.M.; Abdullah, S.; Abdulwahid, A.F. Passive Heat Transfer Enhancement Review in Corrugation. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2015, 68, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xu, M.; Gong, L.; Duan, X.; Chai, J.C. Effects of Surface Roughness in Microchannel with Passive Heat Transfer Enhancement Structures. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 2020, 148, 119070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córcoles, J.I.; Moya-Rico, J.D.; Molina, A.E.; Almendros-Ibáñez, J.A. Numerical and Experimental Study of the Heat Transfer Process in a Double Pipe Heat Exchanger with Inner Corrugated Tubes. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2020, 158, 106526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkar, S.M.; Gönül, A.; Celen, A.; Dalkilic, A.S. Multi-Objective Optimization of Single-Phase Flow Heat Transfer Characteristics in Corrugated Tubes. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 186, 108119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, R.; Bharj, R.S.; Said, Z. Effect of Arc Corrugation Initiation on the Thermo-Hydraulic Performance and Entropy Generation of the Corrugated Tube. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 138, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Lian, S. Effect of Compound Corrugation on Heat Transfer Performance of Corrugated Tube. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 185, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Yu, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Shape Optimization of Corrugated Tube Using B-Spline Curve for Convective Heat Transfer Enhancement Based on Machine Learning. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 2734–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, S.; Valipour, M.S. Experimental Study on the Heat Transfer Enhancement in Helically Corrugated Tubes under the Non-Uniform Heat Flux. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 140, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Li, B.; Sunden, B. Entropy Study on the Enhanced Heat Transfer Mechanism of the Coupling of Detached and Spiral Vortex Fields in Spirally Corrugated Tubes. Heat. Transf. Eng. 2021, 42, 1417–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Sun, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Peng, W. Large-Eddy Simulation of Turbulent Flow and Heat Transfer of Helically Corrugated Tubes in the Intermediate Heat Exchanger of a Very-High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 178, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengel, Y.A.; Cimbala, J.M. Fluid Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, T.H.; Liou, W.W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. A new k-ε eddy viscosity model for high Reynolds number turbulent flows—Model development and validation. Comput. Fluids 1994, 24, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.T.; Li, F.Q.; Wang, G.Y.; Yan, J.; Lu, Z.K. Comparative Study of RANS Models for Simulating Turbulent Flow and Heat Transfer in Corrugated Pipes. Water 2025, 17, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS, Inc. Ansys Fluent Theory Guide, Release 2024 R1; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Usui, Y.; Kasaya, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Iwamoto, H. Marine Magnetotelluric Inversion with an Unstructured Tetrahedral Mesh. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 214, 952–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmagied, M. Determining of the Thermo-Hydraulic Characteristics and Exergy Analysis of a Triple Helical Tube with Inner Twisted Tube. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2024, 204, 109922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, R.J. Using Uncertainty Analysis in the Planning of an Experiment. J. Fluids Eng. 1985, 107, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, A.; Mhrous, Y.; Abdelmagied, M.M. Investigation of the Hydraulic and Thermal Characteristics of a Double Concentric Tubes with an Inner Twisted Spiral Tube. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmagied, M. Thermo-Fluid Characteristics and Exergy Analysis of a Twisted Tube Helical Coil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Grids (Size-NO.) | Re = 12,000 | |

|---|---|---|

| Nu | f | |

| 3.6-125,000 | 92.8826 | 0.08256 |

| 2.9-240,000 | 86.2161 | 0.07615 |

| 2.3-480,000 | 83.4533 | 0.07221 |

| 1.8-1,000,000 | 82.5619 | 0.07113 |

| 1.4-2,140,000 | 81.4728 | 0.07005 |

| 1.2-3,360,000 | 81.0276 | 0.07010 |

| 1.1-4,290,000 | 81.2601 | 0.07003 |

| 0.9-7,660,000 | 81.1047 | 0.07008 |

| Numerical Simulation | EXP. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tube Side | Shell Side | Tube Side | Shell Side | |

| Velocity (m/s) | 0.5~1.8 | 0.5 | 0.5~1.8 | 0.5 |

| Inlet temperature (°C) | 20 | 50 | 20 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cheng, J.; Zhu, J.; Wen, X.; Yu, H.; Lin, W.; Xin, Z.; Yu, J. Heat Transfer Enhancement and Flow Resistance Characteristics in a Tube with Alternating Corrugated-Smooth Segments. Inventions 2026, 11, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010005

Cheng J, Zhu J, Wen X, Yu H, Lin W, Xin Z, Yu J. Heat Transfer Enhancement and Flow Resistance Characteristics in a Tube with Alternating Corrugated-Smooth Segments. Inventions. 2026; 11(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Junwen, Jiahao Zhu, Xin Wen, Haodong Yu, Wei Lin, Zuqiang Xin, and Jiuyang Yu. 2026. "Heat Transfer Enhancement and Flow Resistance Characteristics in a Tube with Alternating Corrugated-Smooth Segments" Inventions 11, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010005

APA StyleCheng, J., Zhu, J., Wen, X., Yu, H., Lin, W., Xin, Z., & Yu, J. (2026). Heat Transfer Enhancement and Flow Resistance Characteristics in a Tube with Alternating Corrugated-Smooth Segments. Inventions, 11(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions11010005