Abstract

The development of effective vaccines is a critical step in effective disease management in aquaculture. This study introduces a novel Multiepitope Chimeric Vaccine (MCV) designed to enhance immunity in lumpfish against Vibrio anguillarum, Aeromonas salmonicida, Yersinia ruckeri, Moritella viscosa and Piscirickettsia salmonis. Epitopes from major toxins and virulence factors were selected to construct the MCV in silico. Structural validation showed 96.7% of residues in favored regions, confirming stability. Codon optimization yielded a G+C content of 54.61% and a Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) of 1, indicating strong expression potential in Escherichia coli. Immune simulations predicted robust B- and T-cell responses, suggesting induction of both humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Experimental vaccination of lumpfish (n = 35/group) with E. coli-expressed MCV led to significantly elevated IgM levels at four- and six-weeks post-vaccination (p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, respectively). Upon pathogen challenge, vaccinated groups showed delayed mortality against V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, and P. salmonis, though survival differences were not statistically significant across treatments. These results highlight the immunogenicity potential of the MCV and its capacity to elicit targeted immune responses. However, further optimization is necessary to improve protective efficacy and survival outcomes. This study lays a foundation for the application of multiepitope vaccines in lumpfish aquaculture and supports ongoing efforts toward sustainable disease control strategies.

Keywords:

multi-epitope vaccines; reverse vaccinology; immune informatics; aquaculture; fish vaccinology Key Contribution:

This study introduces a novel multiepitope chimeric vaccine (MCV) for lumpfish, integrating epitopes from five major bacterial pathogens. The MCV demonstrated strong structural stability, expression potential, and immunogenicity, eliciting significant IgM responses and delayed mortality upon pathogen challenge, thereby laying the foundation for multiepitope vaccine applications in sustainable aquaculture disease management.

1. Introduction

Ectoparasite sea lice (e.g., Lepeophtheirus salmonis, etc.) are a recalcitrant issue of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) aquaculture. One effective biocontrol strategy involves the use of lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus), a native fish of the North Atlantic, which can detect and consume sea lice directly from the salmon skin [1,2]. Finfish, including lumpfish, rainbow trout, tilapia, and salmon, are highly susceptible to bacterial infections caused by pathogens such as Vibrio anguillarum, Aeromonas salmonicida, Moritella viscosa, Yersinia ruckeri, and Piscirickettsia salmonis [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. These infections affect lumpfish performance as cleaner fish in aquaculture operations, and the development of effective vaccines is the primary focus for enhancing the resilience and health of lumpfish in the field. Additionally, lumpfish has become a useful model to study teleost immunity [15,16,17,18].

Traditional vaccine development approaches, including inactivated or live-attenuated vaccines, have demonstrated efficacy, but their development is time-consuming and may lack the specificity or breadth required to protect against the diversity of pathogens affecting cultured fish [19,20,21,22,23]. Multiepitope Chimeric Vaccines (MCVs) are designed and tested in silico before animal experiments and can be tailored against several pathogens [24,25,26,27,28]. A combination of epitopes from different antigens and pathogens, MCVs could stimulate a robust and broad immune response [29,30,31,32,33,34]. In silico vaccine design or reverse vaccinology has transformed vaccine development, allowing for selection of antigens and epitopes, optimizing the vaccine molecular and physicochemical properties, and simulating immune responses before animal experiments [31,35,36,37]. Advancements in computational vaccine design have been complemented by progress in molecular biology techniques [38]. For instance, once the vaccines are completed, DNA synthesis and recombinant expression systems, such as Escherichia coli, enable the efficient production of multiepitope vaccines at large scale and low costs [39,40,41].

Likewise, studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of bacterial recombinant vaccines in aquaculture, with significant yields and immunogenicity. For instance, Flavobacterium psychrophilum heat shock proteins (Hsp) 60 and 70 were identified as highly immunogenic and evaluated as recombinant vaccine candidates. Recombinant forms of these proteins were expressed and purified from E. coli and successfully evaluated in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Eight weeks post-vaccination, all groups showed antibody responses against these recombinant proteins, and fish immunized with rHsp70 exhibited significantly elevated antibody levels against F. psychrophilum and improved protection against F. psychrophilum, suggesting its strong immunogenic and protective potential [42]. In a different study, the efficacy of three different subunit vaccines expressed in E. coli using 14 different proteins of A. salmonicida was successfully evaluated in rainbow trout. Following a challenge with virulent A. salmonicida seven weeks post-immunization, all immunized groups exhibited significantly lower mortality rates (17–30%) at three weeks post-challenge compared to controls (48% and 56%) [43]. Similarly, a recombinant Lactococcus lactis vaccine expressing Streptococcus agalactiae antigens was successfully evaluated in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). This vaccine, expressing the surface immunogenic protein (SIP) and a truncated SIP version (tSIP), was administered orally to juvenile tilapia over a month. The vaccinated fish exhibited significant immunogenic responses, with detectable levels of SIP-specific serum IgM. Fish immunized with the tSIP vaccine achieved the highest protection, with a relative percentage of survival (RPS) of 89% against S. agalactiae at 14 days post-challenge, compared to the 50% RPS for the SIP group. Upregulation of immune markers such as IgM, IL-1β, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ also highlighted the ability of the vaccine to stimulate both humoral and cell-mediated immune response [44].

An MCV targeting Aeromonas veronii, a fish pathogen and antibiotic-resistant strain, was designed using reverse vaccinology [45]. Cadaverine reverse transporter (CadB) and maltoporin (LamB), antigens of A. veronii, were analyzed to identify their epitopes. Selected epitopes were combined and used to design an immunogenic, non-allergenic, and highly soluble MCV [45]. Computational techniques, such as molecular dynamics, structural stability, and compactness, ensured its theoretical efficiency. Codon optimization for E. coli K12 resulted in an ideal G+C content and a high Codon Adaptation Index (CAI), facilitating efficient expression of the vaccine construct. The optimized sequence was successfully cloned into the pET30a+ vector, demonstrating the scalability of recombinant systems for MCV production [45]. Immune simulation models showed the vaccine efficacy before in vivo trials, reducing the time and cost associated with experimental testing [45].

While MCVs hold significant promise, their application in aquaculture remains underexplored, particularly for emerging diseases and non-traditional cultured fish species like lumpfish. To date, most MCVs have been developed to target common pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, but their broader potential across diverse species and novel disease challenges has yet to be fully realized [46,47].

The challenges in the design of MCVs are related to the linkers used between between epitopes, which affect the overall properties of the MCVs. Linkers that maintain the structural integrity of epitopes and reduce junctional immunogenicity have been previously identified and are commonly used in MCVs to improve antigen processing and presentation [48,49]. However, despite their utility, linker-based MCVs can face limitations in terms of protein folding, stability, and epitope accessibility, especially in multivalent vaccine designs. Structural protein scaffolds provide greater stability, solubility, and spatial organization of epitopes. For instance, flavodoxin and flavodoxin-like proteins can serve as scaffolds for inserting epitopes. This approach was successfully used in an MCV with five epitopes against Streptococcus agalactiae, conferring a relative percent survival (RPS) of 76% in tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) [46].

In this study, we developed a novel MCV for lumpfish that incorporated 11 common and specific epitopes identified in frequent bacterial pathogens of fish, including V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, Y. ruckeri, M. viscosa, and P. salmonis [50]. These epitopes were assembled using the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) scaffold, a flavodoxin-like protein for enhanced protein stability. In silico tools, including structural modeling and immune simulations, were employed to optimize the MCV structure and predict its immunogenicity, guiding the design for efficient expression. The finalized construct was then expressed in E. coli to enable scalable production. Experimental trials were conducted under controlled conditions to assess the immune response and protective efficacy of the MCV in lumpfish. These integrated approaches provide a robust foundation for the application of MCVs in aquaculture, addressing a critical need for effective disease management in lumpfish populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Engineering and Epitope Integration

To engineer the MCV, the DHODH scaffold was used. Specific regions of DHODH were selectively replaced with six epitopes derived from common outer membrane proteins (OMPs), and five from virulence factors relevant to V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, Y. ruckeri, M. viscosa, and P. salmonis, previously identified [50]. This incorporation was strategically performed to ensure that the epitopes retained structural stability while potentially enhancing the immunogenicity of the chimeric protein. The integration process involved precise sequence alignment and molecular modeling to ascertain the compatibility and functionality of the epitopes within the DHODH framework.

2.2. Computational Analysis

To characterize the designed MCV, the Expasy ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/; accessed on 31 December 2025), a comprehensive computational resource that allows for the determination of various physical and chemical parameters of proteins, was used [51]. The tool analyzed proteins stored in UniProtKB databases and user-entered sequences. The parameters assessed by ProtParam tool included molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point (Pi), amino acid composition, atomic composition, extinction coefficient, estimated half-life, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) [51].

2.3. Computational Protein Modeling and Validation of the 3D Structure of MCV

The 3D structure of the MCV was generated using computational protein modeling techniques. The Swiss model server was used for the prediction of the 3D structure of the MCV protein sequence (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/; accessed on 31 December 2025) [52,53]. The server used a library of experimental protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to perform homology modeling of the MCV. The output from the server included a QMEAN score for global model quality and a local per-residue model quality estimation. This provided a comprehensive assessment of the MCV model. After predicting the 3D structure of the MCV, this was refined using the Swiss Model server’s built-in refinement tools. This step is crucial as it improves the MCV model stereochemistry. The refinement process involved energy minimization and side-chain optimization. Finally, the validation of the refined model was performed using MolProbity on the Swiss model. MolProbity provided a comprehensive validation of the stereochemical quality of the MCV model. The validation process included multiple structural quality assessments such as clash score, Ramachandran plot analysis, rotamer analysis, and the MolProbity score. The clash score measures the number of serious steric overlaps (>0.4 Å) per 1000 atoms, indicating potential errors in atomic positioning [54,55]. The Ramachandran plot analysis evaluates the backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ) of amino acid residues to determine whether they fall within energetically favorable regions [56,57]. For a stable protein structure, over 90% of residues should lie in favored regions, with less than 10% in allowed regions and ideally less than 1% in disallowed regions [58]. Rotamer analysis checks the side-chain conformations against common rotamer libraries to identify strained or disallowed conformations [59]. The MolProbity score is a combined metric that includes the clash score, percentage of residues in favored regions of the Ramachandran plot, and percentage of rotamers in favored regions. The antigenic probability of the MCV was calculated on VaxiJen version 2.0 (https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/vaxijen/VaxiJen/VaxiJen.html; accessed on 31 December 2025) [60]. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to assess binding stability and structural compactness.

2.4. Codon Optimization and Cloning Design

The sequence of the MCV was codon optimized for E. coli using the Java Codon Adaptation Tool (JCat) server (https://www.jcat.de/; accessed on 31 December 2025). Codon optimization was based on the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) values and 50% G+C content [61].

The SnapGene tool version 5.2.4 (https://www.snapgene.com/; accessed on 31 December 2025) was used to visualize, annotate, and simulate the cloning of the optimized MCV sequence into the selected expression vector. The pET30a (+) vector (EMD Biosciences) was selected for cloning due to its strong T7 promoter regulated by a lac operator and its T7 transcriptional terminator, enabling high-level of IPTG-inducible expression. The optimized MCV gene fragment was then inserted into the vector multiple cloning site (MCS), using EcoRI and EcoRV restriction sites. A poly-histidine (6-His) affinity tag was included at the C-terminus to facilitate purification by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) if required and Western blot detection. After the cloning simulation, the sequence integrity of the final plasmid construct was verified using SnapGene. Additionally, SnapGene was configured to avoid prokaryotic ribosome-binding sites and the cleavage sites of the EcoRI and EcoRV restriction enzymes. Following the codon optimization, the optimized gene sequence was synthesized commercially by GenScript and cloned into the pET30a (+) expression vector using, EcoRI and EcoRV restriction sites.

2.5. Immune Simulation of MCV

The C-ImmSim server (https://kraken.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM/index.php?page=0; accessed on 31 December 2025) was used to simulate the immunogenicity of the MCV construct. This tool is designed to mimic the dynamics of an immune system responding to vaccination. The model integrates a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) for predicting immune epitopes and employs machine learning to forecast interactions between different immune components [62]. The vaccination regimen was simulated with up to four injections, each administered at 28-day intervals, specifically on days 0, 28, 56, and 84. In the simulation, these time points correspond to steps 1, 84, 168, and 252, with each time step representing 8 h post-immunization. This time-step conversion allows the model to closely mimic the timing of real immune responses [63]. Each injection delivered 1 unit of vaccine in a simulated volume of 100 µL. The entire immune response was modeled over 100 simulation steps to assess the progression of antigen presentation and antibody production. All other parameters, including cell counts, antigen presentation, and immune cell replication dynamics, were set to default, unless otherwise specified. The output data from C-ImmSim were processed to analyze immune cell populations over time, including B cells, T cells, and their respective states (e.g., active, duplicating, resting, and anergic).

2.6. Transformation of E. coli with a Recombinant Plasmid Harboring the MCV

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli BL21 Star™ (DE3) electro-competent cells were transformed with the respective recombinant plasmid carrying the MCV or the empty vector (control) [64]. To electroporate E. coli with the plasmid of interest, the electrocompetent bacteria were thawed on ice and 50–100 μg of plasmid was added. The cell and plasmid suspension mix was transferred to an electroporation cuvette. Cells were electroporated at 2.5 kV (E. coli PulsorTM Transformation apparatus, Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 0.5 s and resuspended in 300 μL of LB. Then the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a shaker at 180 rpm, centrifuged (8000 rpm) for 10 min at room temperature, resuspended in 50 μL of LB, and plated on Kanamycin (50 μg/mL)-supplemented LB agar plates and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. Then, single colonies were isolated and evaluated for protein expression using Western blots.

Table 1.

List of strains and plasmids used in this study.

2.7. Evaluation of MCV Expression in E. coli

Expression of the MCV in E. coli was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using standard protocols [64]. A single colony of E. coli harboring the recombinant pEZ317 plasmid (pET30+(a) and MCV insert) was incubated in 3 mL of LB supplemented with kanamycin (Km; 50 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 37 °C with aeration (180 rpm). Once the cell density reached an O.D. of ~0.6–0.8 at 600 nm, 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma-Adrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to induce MCV expression for 4 h. About 1 mL of culture was collected and centrifuged at 4200× g at room temperature for 10 min, and the resulting pellets were washed once with PBS. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 2X SDS-Coomassie blue loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. Aliquots of 5 µL were loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gels and separated at 120 V for 1 h and 40 min using a Mini-PROTEAN II Cell electrophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The gels were stained with Coomassie blue solution (50% (vol/vol) methanol, 10% (vol/vol) glacial acetic acid, 0.125% (wt/vol) Coomassie blue, ddH2O up to 1 L) for 30 min, then destained in destaining solution (30% (vol/vol) methanol, 10% (vol/vol) acetic acid, ddH2O up to 1 L).

To detect the expression of MCV by Western blot, proteins were transferred onto 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) using a semi-dry TRANS-BLOT SD apparatus (Bio-Rad) at 20 V for 30 min. Membranes were blocked overnight at room temperature in blocking buffer (0.5% skim milk in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T)). Following blocking, membranes were washed three times for 10 min each with PBS-T at room temperature with gentle rocking (50 rpm). Membranes were then incubated overnight at room temperature with a primary mouse anti-His tag monoclonal antibody (1:5000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted in blocking buffer. After three additional 10-min washes with PBS-T at room temperature under gentle rocking, membranes were incubated overnight with a goat anti-mouse IgG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) with gentle shaking (50 rpm) at room temperature. Color development was performed using a nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) substrate mixture (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

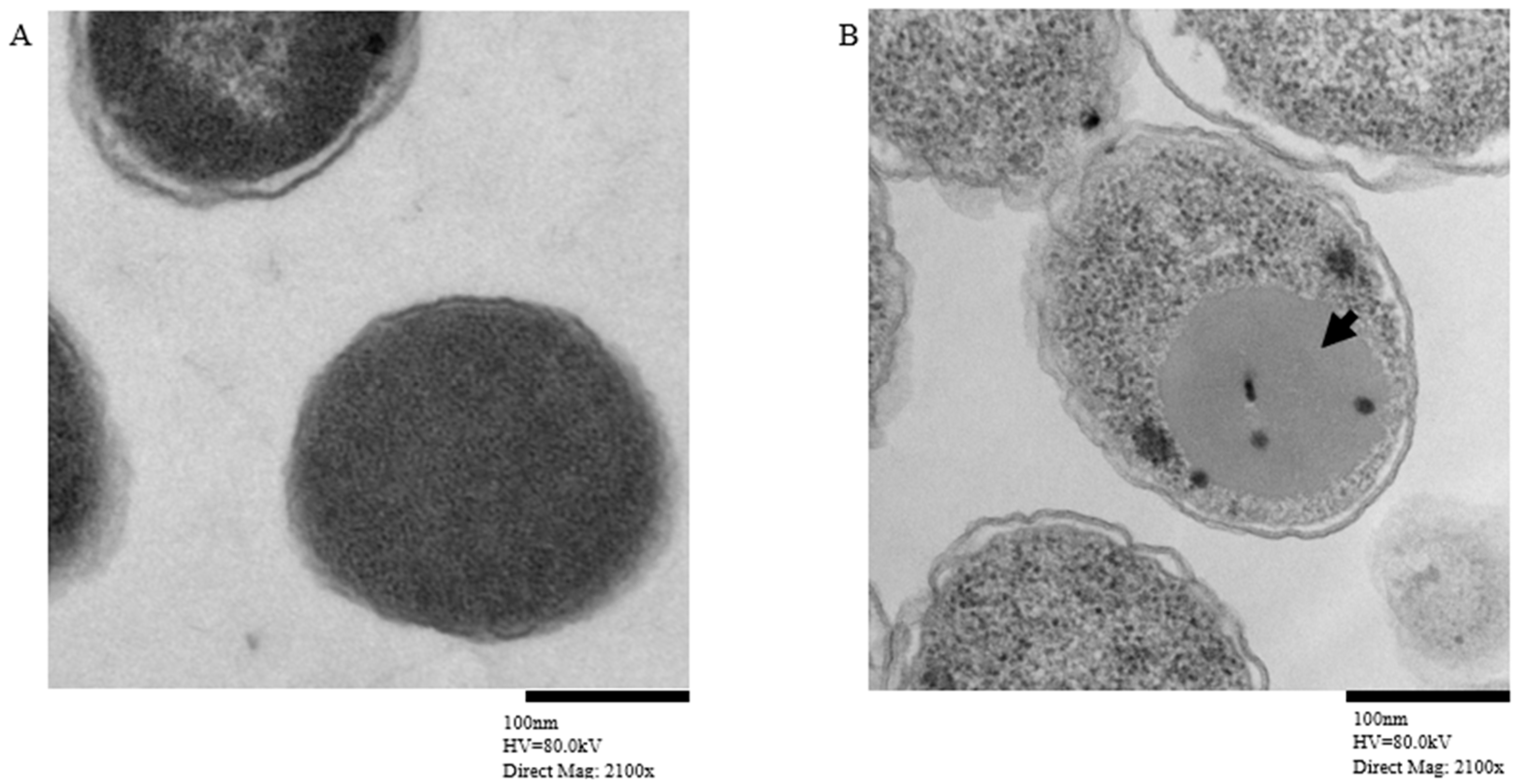

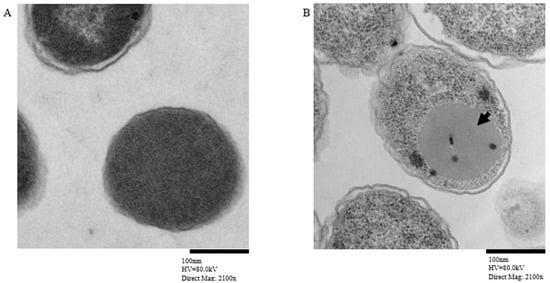

2.8. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM was conducted to examine the formation of inclusion bodies in the E. coli cells, confirming the intracellular accumulation of the expressed protein. Briefly, E. coli pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA) and processed at the Electron Microscopy Facility, Memorial University of Newfoundland, for both simple staining and sectioning. For simple staining, 5 μL of the bacterial suspension was placed onto copper formvar/carbon grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Staining was performed with 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min, followed by a 1-min wash in 0.1 μm-filtered phosphate-buffered saline (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at room temperature. Imaging was carried out using a Tecnai Spirit Transmission Electron Microscope operating at 80 kV, equipped with a 4-megapixel AMG digital camera, at magnifications ranging from 15,000× to 21,000×.

For sectioning, the bacterial samples were fixed in Karnovsky fixative for 20 min, washed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 5 min, and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 15 min. Samples were dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol and acetone, infiltrated with EPON resin (Sigma), and polymerized overnight at 70 °C in BEEM capsules (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Ultra-thin sections were cut using a diamond knife (Diatome, Hatfield, PA, USA), mounted on 300 mesh copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined using a Tecnai™ Spirit TMA microscope (FEI company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

2.9. Bacterial and Culture Conditions

All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteriological media are from Difco (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). P. salmonis LF89 was initially grown on a CHSE-214 monolayer cell culture. Bacteria were then inoculated onto CHAB agar plates (brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 1 g/L L-cysteine and 5% salmon blood) and incubated at 15 °C for 20 days. A single colony was subsequently transferred into Austral-SRS broth and incubated at 15 °C for an additional 10 days with gentle shaking (100 rpm) until reaching approximately 108 cells/mL (O.D.600~1.0) [67]. A. salmonicida strain J223 was grown in Tryptic Soya Broth (Yeast extract 5 g; Tryptic soy broth 30 g; NaCl 10 g, dextrose 1 g; Difco (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) [68], and V. anguillarum O2 strain J360 was grown in TSB supplemented with 2% NaCl [17,66]. E. coli strains were grown in LB (yeast extract 5 g; Tryptone 10 g; NaCl 10 g, dextrose 1 g) at 37 °C with aeration (180 rpm). When required, the culture media were supplemented with 1.5% agar.

2.10. Fish Holding

Lumpfish were raised and maintained at the Dr. Joe Brown Aquatic Research Building (JBARB) at the Department of Ocean Sciences, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada. The lumpfish were kept in 500 L tanks using a flow-through system (75 L/min) of UV-treated seawater, 95–100% air saturation, and ambient photoperiod (12 h light:12 h dark). Proper biomass density (5–30 kg/m3) was maintained throughout all the experimental periods. The fish were fed twice daily at 0.5% body weight with a commercial diet (Europa 15-Skretting). This experiment was performed following the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Institutional Animal Care Committee (https://www.mun.ca/research/about/acs/acc/, accessed on 31 December 2025) (protocols #17-01-JS; #17-02-JS) and biohazard license L-01.

2.11. Recombinant E. coli-MCV Preparation

A single verified E. coli BL21 Star™ (DE3) colony harboring the pEZ317 plasmid was selected for large-scale culture. The verified colony was inoculated into 50 mL of LB broth supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm overnight. The overnight culture was then used to inoculate 500 mL of fresh LB broth containing kanamycin. Cultures were grown at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm until reaching an O.D.600 of ~0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG, and cultures were incubated for an additional 4 h under the same conditions. Following induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4200× g for 20 min at 4 °C. Bacterial pellets were washed twice with PBS to remove residual media components. The final bacterial pellet was resuspended in sterile PBS to an approximate concentration of 108 CFU/mL, and Carbigen adjuvant was added at 10% v/v. The mixture was stirred gently, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 to ensure optimal antigen encapsulation and stability.

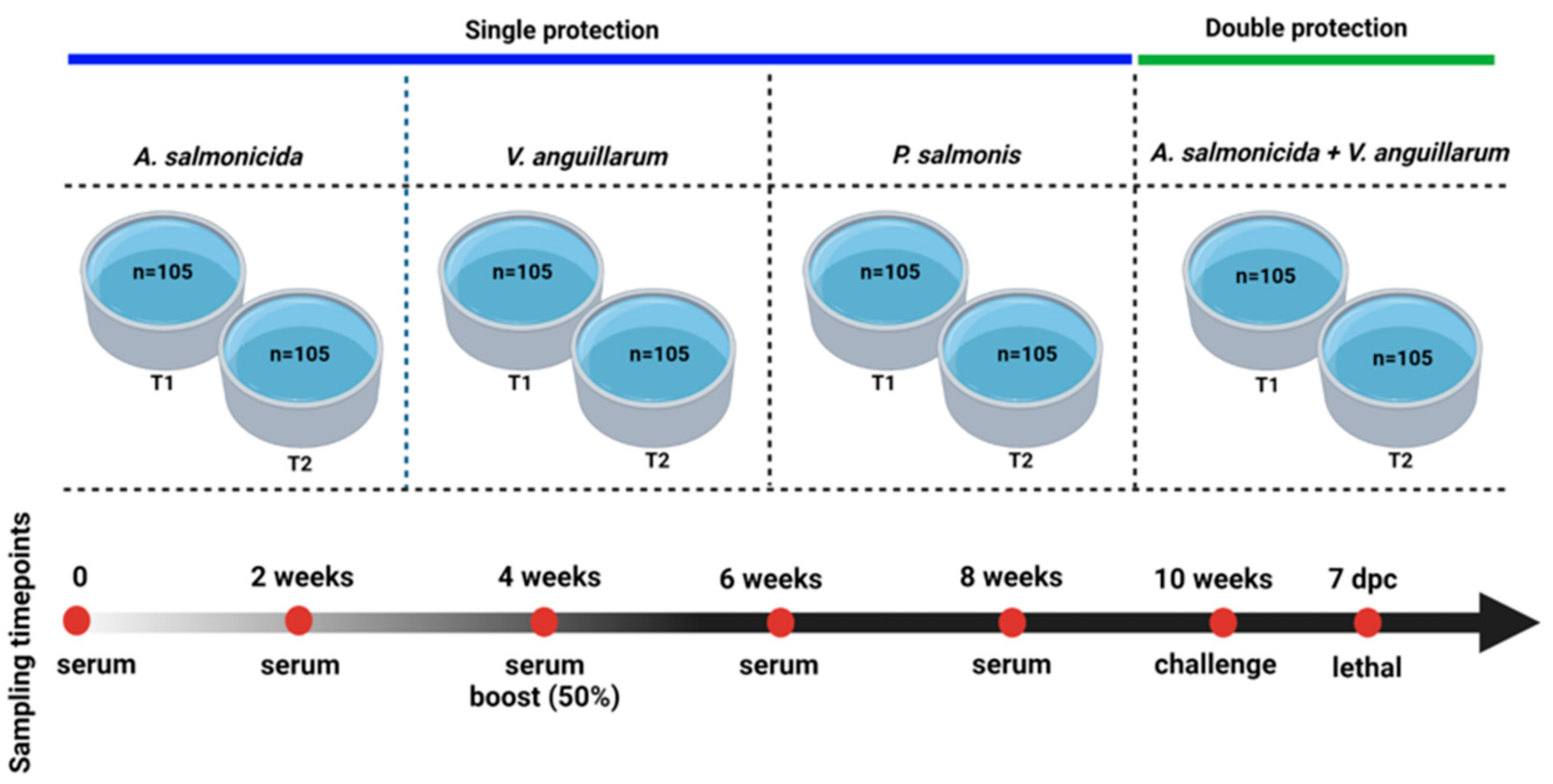

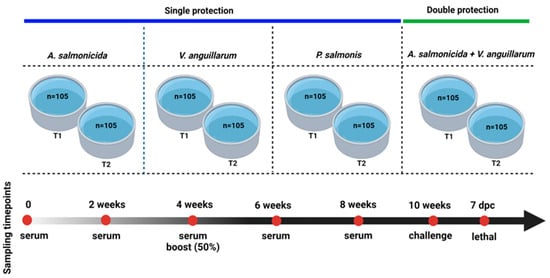

2.12. Lumpfish Experimental Design and Immunization

A common garden experiment was designed to evaluate the immunogenicity and efficacy of MCV in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus). Lumpfish were Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT)-tagged in the peritoneal cavity and acclimated for 2 weeks. A total of 315 lumpfish were randomly assigned to three experimental groups, each comprising 105 fish. The experimental group was intraperitoneally injected with 2.1–2.4 × 109 cells/100 μL of E. coli pEZ317 expressing the MCV protein, the control group was injected with E. coli cells harboring only the empty pET30+(a) vector, and the placebo control group received a PBS mixed with Carbigen adjuvant. The immunization protocol involved a primary immunization followed by a booster at 4 weeks. Fish were kept under controlled conditions with a temperature maintained at 10 °C, an ambient photoperiod, and a feeding ratio of 0.5%. The fish used in the experiments ranged in size from 15 to 20 g. Serum samples for immunogenicity assessment were collected at two-week intervals until 10 weeks post-immunization (wpi).

2.13. Lumpfish Challenge and Sampling

At 10 wpi, the immunized lumpfish were subjected to pathogen challenge tests to evaluate the MCV efficacy against three individual bacterial pathogens, V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, and P. salmonis. Also, an additional co-infection challenge with V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida was conducted. The challenge dose was 104 CFU/100 μL via i.p. injection for P. salmonis and bath challenge for V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida. Survival was monitored daily for up to 30 days post-challenge for all groups and 90 days post-challenge for the group challenged with P. salmonis. The relative percentage survival (RPS) was calculated according to the formula: 1 − (% mortalities of vaccinated fish/% control mortalities) × 100 [69].

2.14. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

To evaluate the humoral immune response elicited by the MCV, serum IgM titers were measured using an antigen-specific ELISA. Blood samples were collected from lumpfish in the first vaccination trial at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks post-vaccination (wpv) using 1 mL syringes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) fitted with 26 G, 23 G, or 21 G needles depending on fish size (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Approximately 500 µL of blood was drawn from each fish (n = 6 per time point) into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and immediately placed on ice.

Blood samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (9600× g) for 5 min, after which the serum phase was carefully collected. The precipitated blood cells were discarded, and serum samples were stored at –80 °C until further processing. Before ELISA, serum samples were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min, followed by lipid removal using 100 µL of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 min at room temperature, following Vasquez et al., 2020b [33]. Samples were centrifuged again at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatants were transferred into fresh microcentrifuge tubes and stored at –80 °C until analysis.

For the ELISA, formalin-killed E. coli expressing the MCV was used as the antigen. Ultra-High Binding 96-well ELISA plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were coated with 106 cells/well of the antigen, a concentration optimized following standard protocols [70]. Plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C, then washed three times with PBS-T (PBS + 0.1% Tween-20). Wells were blocked with 150 µL Chondrex blocking buffer (Chondrex Inc., Woodinville, WA, USA) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C before being washed three times with PBS-T. Serum samples were serially diluted 1:2 in PBS-T, starting from 1:2 to 1:16,384, by mixing 60 µL serum with 60 µL PBS-T and continuing twofold dilutions across the plate. The first column served as a non-serum blank control. Plates containing diluted sera were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then washed five times with PBS-T. Next, 100 µL of chicken IgY anti-lumpfish IgM (Soumru, Charlottetown, PEI, Canada) diluted 1:10,000 in PBS-T was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After five washes with PBS-T, 100 µL of streptavidin-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA; 1:10,000) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were washed five times, followed by the addition of 50 µL TMB substrate (Invitrogen™, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated at room temperature (20–22 °C) for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 2 M H2SO4, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax M5e microplate reader (San Jose, CA, USA).

2.15. Statistical Analysis

Survival data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, and differences between treatment groups were assessed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. Survival outcomes were expressed as percentage survival over the challenge period. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was applied for all survival analyses.

Humoral immune response data obtained from ELISA IgM titers were analyzed using a non-parametric Friedman test followed by the Duncan multiple-comparison post hoc test to evaluate differences among treatment groups across time points. This statistical approach was selected due to the repeated-measures nature of the ELISA data and the non-normal distribution of antibody titers. Differences were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05 and highly significant at p ≤ 0.01.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated.

3. Results

3.1. Epitope Selection for the Construction of the MCV

The selection of epitopes integrated into the MCV was based on their antigenic potential and relevance to the pathogenicity of lumpfish, as identified in our previous study (Figure 1, Table 2) [50]. This strategy aimed to ensure a broad-spectrum immune recognition and response in vaccinated lumpfish. The vaccine incorporated diverse epitopes to target common outer membrane antigens of target pathogens including an 11-residue epitope from the LPS assembly protein LptD (PYYLNLAPNYD), a 7-residue epitope from the outer membrane protein assembly factor BamA (IEGLQRL), and a 14-residue epitope from the TonB-dependent siderophore receptor (EKIDVRGGAAVQYG). Additionally, epitopes from common secreted antigens, such as the flagellar hook assembly protein FlgD (9 residues, WDGNDQNGN) and the flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgG (19 residues from LLTQLAQQDP and ALQASALVG), were selected to enhance the vaccine structural representation and functionality.

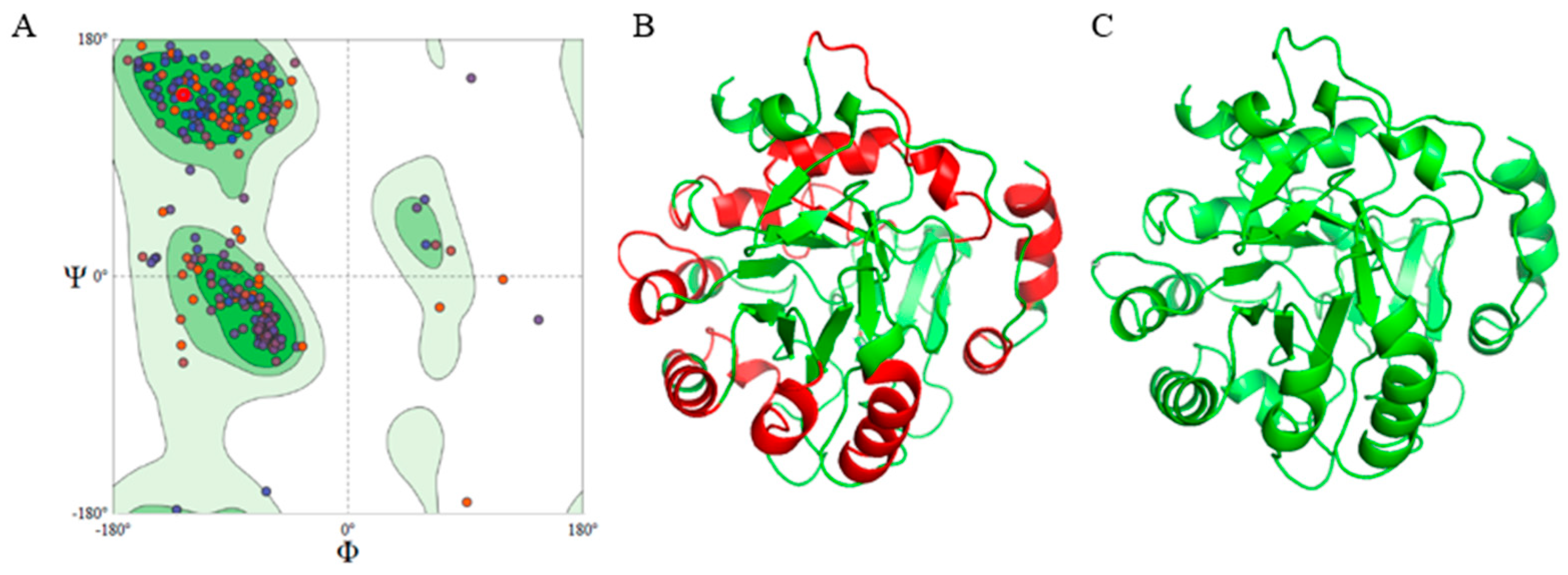

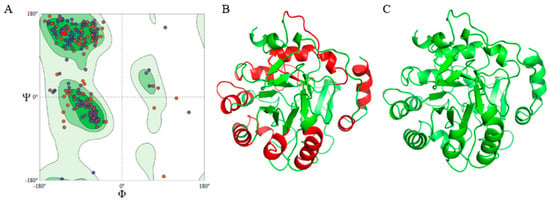

Figure 1.

Structure of Multiepitope Chimeral Vaccine (MCV). (A) Ramachandran’s plot of MCV showing 91.39% amino acids in the favored region. (B) Three-dimensional structure of MCV, red regions represent epitopes. (C) Three-dimensional structure of MCV after refinement, showing 96.7% amino acids in the favored region.

Table 2.

Epitopes used to design MCV [50].

Epitopes from toxins and virulence factors specific to each bacterial pathogen were also incorporated, including the hemolysin from V. anguillarum (DGVYNYDTGLLFTYD), the siderophore amonabactin from A. salmonicida (LQPGVFRLNPILLSL), the heme acquisition hemophore HasA from Y. ruckeri (SSAMIIDGTLHYSYF), and epitopes from the M23 family metallopeptidase of M. viscosa (HSKLFNIYFLIFSLI) and the M4 family metallopeptidase from P. salmonis (GSGVFNKAFYLLSQQ).

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of the MCV

The MCV was designed to integrate eleven immunogenic epitopes within a stable protein scaffold DHODH (Table 3). The MCV comprised 340 amino acids, forming a protein with a molecular weight of 36,478.27 Da. This size is within the typical range for similar therapeutic proteins, facilitating effective biochemical functionality and potential immunogenicity [71,72].

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of Multiepitope Chimeral Vaccine (MCV). The red color indicated the selected epitope sequences.

The antigenic probability of the MCV was 0.6139, which is above the VaxiJen threshold of 0.4 for antigenic protein (Table 2). This score suggests a significant potential for the MCV to elicit an immune response, highlighting its potential as an effective vaccine candidate. The theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the MCV was determined to be 5.67 (Table 3), which suggests that the vaccine will exhibit optimal stability and solubility under slightly acidic conditions, typical of many biological fluids [73,74].

The estimated half-life of the MCV varied across different biological systems, being highest in mammalian reticulocytes with 30 h, 20 h in yeast, and over 10 h in E. coli (Table 3). This suggests that the MCV is sufficiently stable for practical use in diverse biological contexts, supporting sustained immunogenic activity. The instability index (II) of the protein was computed to be 38.61 (Table 3), classifying it as stable under physiological conditions [51].

Furthermore, the grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) for the MCV was determined to be −0.013 (Table 3), indicating a balanced hydrophilic nature. Typically, hydropathicity values range from −2 to +2, with values closer to −2 suggesting higher solubility [75]. The near-neutral GRAVY value of the MCV suggests it is sufficiently hydrophilic, which is advantageous for maintaining solubility in vaccine formulations. The aliphatic index of 98.06 suggests that the protein structure is likely to be stable across a wide range of temperatures, enhancing its usability in various environmental conditions [76]. The extinction coefficient was measured at 27,850 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm, providing a baseline for quantitative protein analysis in solution.

Electrostatic analysis revealed that the MCV contains a total of 31 negatively charged residues and 26 positively charged residues. This near-balanced charge ratio contributes to the structural stability of the protein, potentially affecting its interaction with the host immune system [77]. The physicochemical properties of the MCV indicate a well-designed protein vaccine candidate with suitable stability, solubility, and immunogenic potential, making it a promising tool for protective immunization strategies in aquaculture.

3.3. Structural Modeling and Codon Optimization of MCV

The computational 3D structure of the MCV was successfully predicted using the Swiss Model server. The Ramachandran plot displays the phi (ϕ) and psi (Ψ) angles for the MCV structure, with 91.39% of amino acids in favored regions, which indicates a generally favorable conformational structure for the protein backbone (Figure 1A). Following structural modeling, the 3D structure of the MCV construct was predicted, with immunogenic epitopes localized on its surface as shown in Figure 1B. After refinement, the structural quality improved significantly, with 96.7% of amino acid residues located in the favored regions of the Ramachandran plot, indicating enhanced protein stability and potential functional efficacy (Figure 1C).

MolProbity validation confirmed the accuracy of the model, as shown by favorable Ramachandran plot statistics and a low clash score of 2.25, indicating high-quality structures with minimal steric clashes and good geometric parameters (Supplementary Materials) [78]. Detailed analysis of protein side chains and their interactions highlighted specific areas for potential refinement to further reduce clashes and optimize rotamer conformations. Outliers, representing 2.08% of residues in unfavorable conformations, were likely corrected during the refinement process, leaving 96.7% of residues within favored regions (Figure 1C).

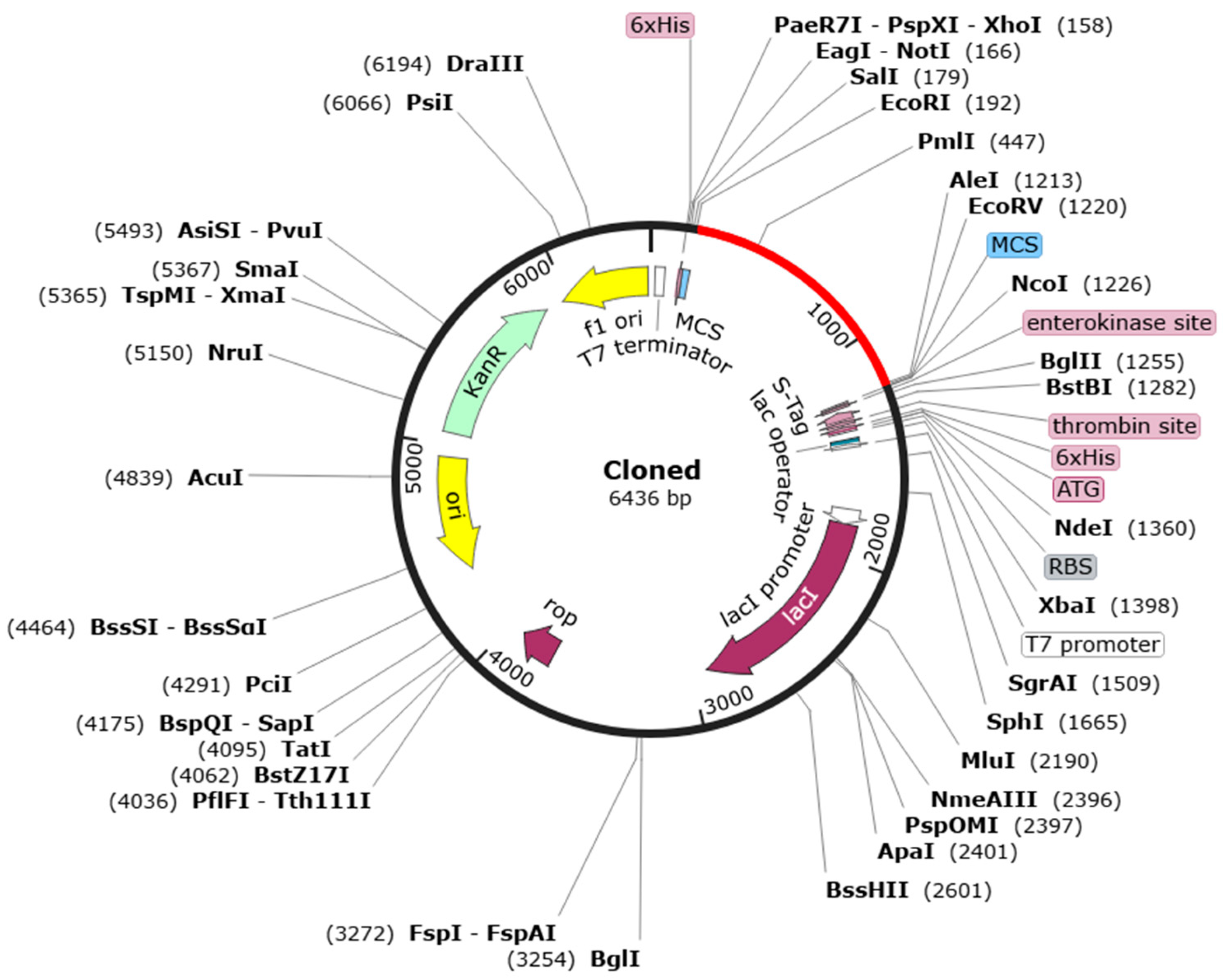

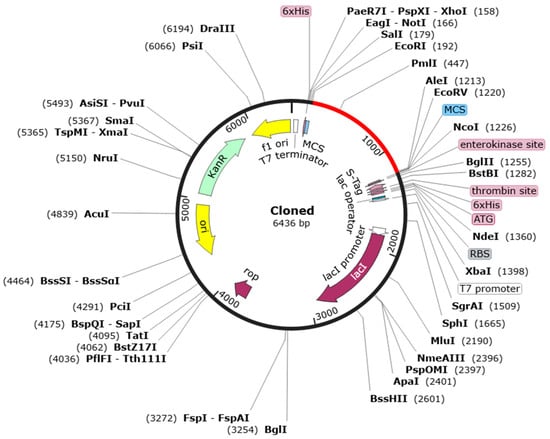

The codon optimization of the MCV sequence was conducted to enhance expression in E. coli (Table 4). The nucleotide sequence comprising 1259 bases achieved a G+C content of 54.61%, which is within the ideal range of 30% to 70% for stable DNA structure and efficient transcription and translation in microbial systems [79,80]. Furthermore, the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) was calculated to be 1, indicating optimal compatibility with the host translational machinery. This high CAI value suggests that the vaccine will likely be expressed efficiently in E. coli, maximizing protein yield and stability. The MCV gene was codon-optimized and inserted into the pET30a (+) vector, resulting in the pEZ317 vector. The corresponding plasmid map of pEZ317 highlights the location of the MCV insert (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Codon optimization of MCV. The G+C content of the optimized nucleotide sequence of MCV was well within the optimal G+C percentage range (30–70%). The Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) indicates the possibility of efficient expression of the vaccine in the host (E. coli).

Figure 2.

In silico restriction cloning design. The red portion in the vector represents the multi-epitope chimeral vaccine-pEZ317vector map inserted into the black pET30a(+) vector. Codon optimization for E. coli cell and gene synthesis, clone to pET30a using EcoRI and EcoRV.

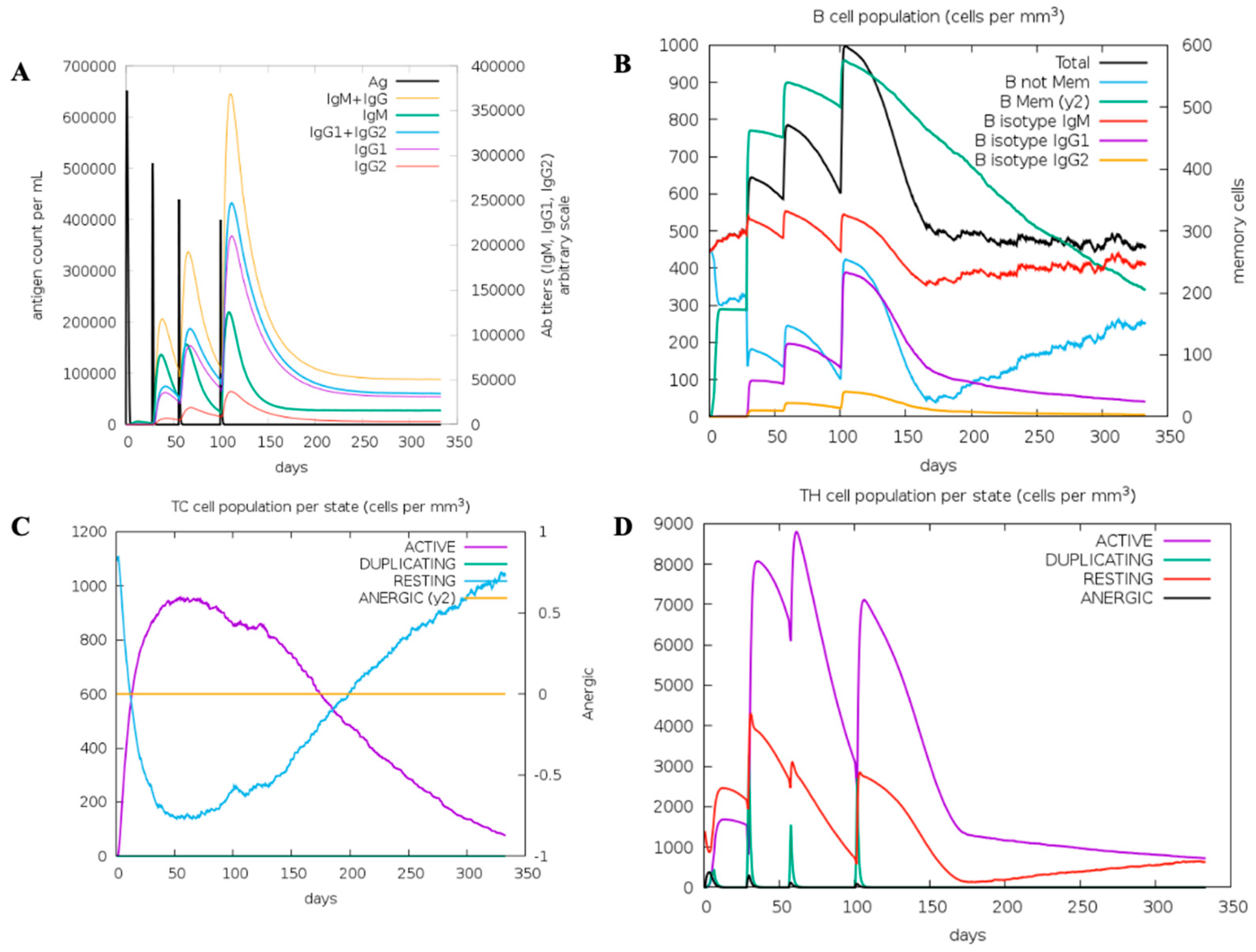

3.4. In Silico Immune Simulation of MCV

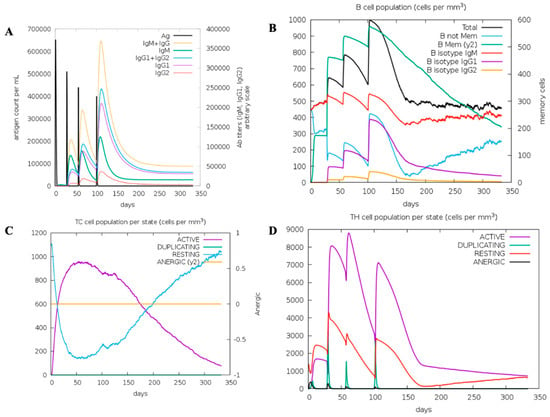

The in silico simulation conducted using the C-ImmSim server demonstrates the immune response to multiple vaccine injections. The simulation results show high initial levels of IgM, followed by significant increases in IgG1 and IgG2, with corresponding declines in antigen levels, indicating an effective immune response (Figure 3). However, C-ImmSim is a mammalian-parameterized immune simulation platform; therefore, it reports immunoglobulin classes such as IgG1 and IgG2, which do not exist in teleost fish, including lumpfish. Teleosts primarily express immunoglobulin isotypes such as IgM, IgD, and IgT/IgZ, and do not exhibit mammalian IgG subclasses. Accordingly, the IgG1/IgG2 curves shown in Figure 3 are interpreted only as model-derived proxies representing a secondary, high-affinity, memory-like humoral response within the simulation framework, rather than teleost antibody subclasses. The simulation further indicated that successive vaccine doses led to an expansion of B cell populations, including memory B cells, supporting the potential development of long-term immune memory (Figure 3B). Moreover, the dynamics of cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) and helper T cells (CD4+) in response to vaccination were also evaluated, revealing robust activation and proliferation following immunization (Figure 3C and Figure 3D, respectively). They highlight the crucial roles of T cells, showing peaks in active and duplicating states shortly after each injection. Overall, the simulation is presented as a qualitative, hypothesis-generating tool to support construct design and explore immune-response kinetics, rather than as a definitive predictor of teleost-specific immunoglobulin dynamics. This simulation demonstrates the potential benefits of a multi-dose vaccination strategy in achieving sustained immunity against bacterial pathogens.

Figure 3.

In silico immune simulation of MCV. (A) Immunoglobulin production in response to antigen injections (black vertical lines); specific subclasses are indicated as colored peaks. (B) The evolution of B-cell populations after four injections. (C) Cytotoxic T (CD8) cell populations per state after the injections. The resting state represents cells not presented with the antigen, while the anergic state represents T-cell tolerance to the antigen due to repeated exposure. (D) The evolution of Helper T (CD4) cell populations per state after the injections.

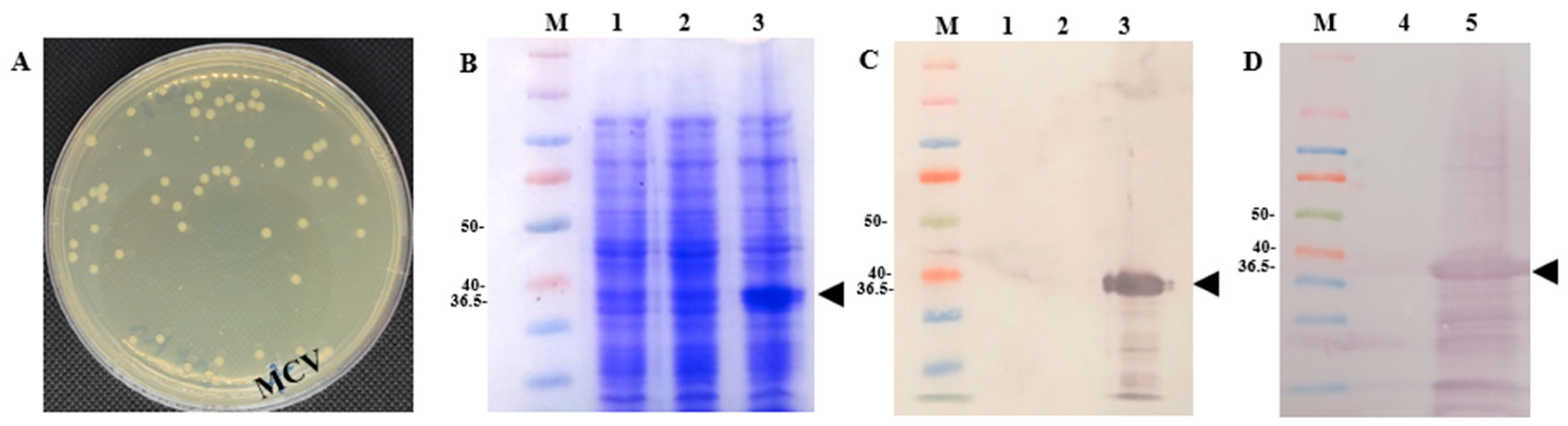

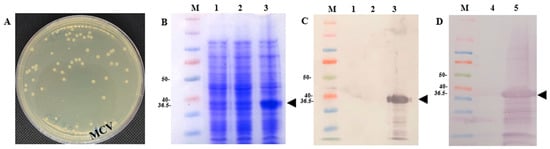

3.5. Expression of MCV Plasmids in E. coli

The expression of MCV plasmids in E. coli BL21 cells was successfully confirmed following cloning. After transformation, visible colony growth indicated successful plasmid integration (Figure 4A). Analysis by SDS-PAGE revealed the MCV protein expression in E. coli harboring the pEZ317 vector and induced with IPTG (Figure 4B,C). Further validation by Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of MCV proteins at the expected molecular weight of 36.5 kDa (Figure 4D). Specifically, a chicken IgY anti-lumpfish IgM antibody (Soumru, PEI, Canada) was used as the primary antibody at a 1:5000 dilution, and a goat anti-chicken IgY (H+L) HRP-conjugated antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used as the secondary antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Figure 4.

Expression of MCV plasmids in E. coli. (A) MCV colonies after successful cloning of the MCV plasmid into the E.coli BL21 strain, in a kanamycin-resistant plate (50 μg/L). (B) SDS page showing the expression of MCV in an E. coli colony. (C) Western blot showing the expression of MCV in an E. coli colony. (D) Western blot showing the expression of MCV in E. coli bacterin. MCV is a multiepitope chimeral protein. Control is E. coli with an empty plasmid. Anti-His tag antibody was used. The black arrowhead indicates the MCV with a molecular weight of 36.5 kDa. The molecular weight reference used in the Western blot was the Bio-Rad Precision Plus Protein™ Dual Color Standard, which provides distinct colored bands ranging from 10 to 100 kDa, with reference markers. Lane 1—Empty E. coli induced with IPTG, Lane 2—E. coli with MCV but not induced with IPTG, Lane 3—E. coli with MCV induced with IPTG, Lane 4—Control (E. coli induced with IPTG), Lane 5—MCV induced with IPTG for vaccination, Lane M—molecular protein marker.

Transmission electron microscopy showed MCV inclusion bodies in E. coli harboring the pEZ317 vector and induced with IPTG (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Transmission electron microscopy showing MCV with inclusion bodies (A) and Control (B). The black arrowhead indicates the inclusion bodies formed by the MCV inside the E. coli.

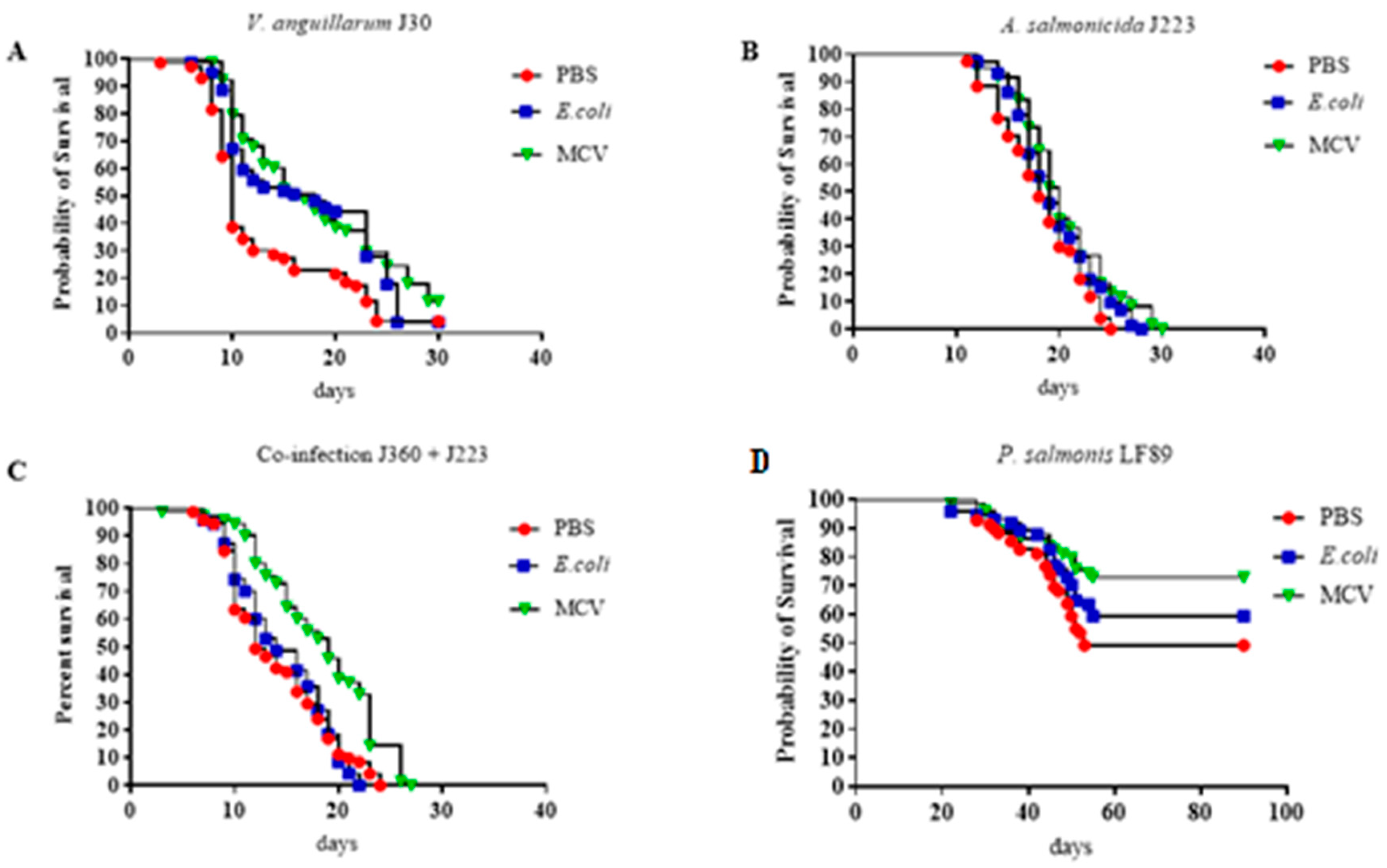

3.6. Immune Protection and Efficacy of MCV in Lumpfish

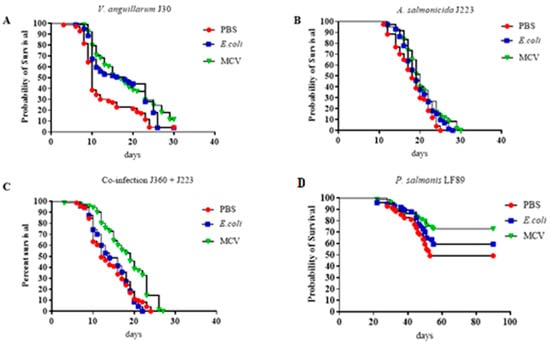

The experimental results demonstrated the protective efficacy of the multi-epitope chimeric vaccine (MCV) against multiple bacterial pathogens in lumpfish (Figure 6). Across all challenge trials, including infections with V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, P. salmonis, and a co-infection model involving V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida, fish vaccinated with the MCV consistently showed no significantly higher survival rates (p ≤ 0.05 or p ≤ 0.01) compared to those treated with PBS or E. coli (Figure 7). The calculated RPS for the MCV-treated group challenged with V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, P. salmonis, and the group coinfected with V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida is 27.8%, 21.1%, 44.4%, and 33.3%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Experimental design for evaluating the novel multiepitope chimeric vaccine (MCV) in lumpfish. This is a common garden experiment of three groups of lumpfish (n = 35) immunized with either 2.1–2.4 × 109 cells/100 μL of E. coli expressing MCV protein or a control (E. coli) and PBS mixed with carbigen adjuvant. Temperature: 10 °C. Photoperiod: ambient. Feed ratio: 0.5%. Fish size: 15–20 g.

Figure 7.

Survival curve for Multiepitope Chimeral Vaccine trials. (A) Challenged with V. anguillarum (B) Challenged with A. salmonicida (C) Challenged with Coinfection with V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida. (D) Challenged with P. salmonis LF89. The trial was conducted in duplicates with a bacterial dose of 104. The calculated RPS for the MCV-treated group challenged with V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, P. salmonis, and the group coinfected with V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida is 27.8%, 21.1%, 44.4%, and 33.3%, respectively. Survival data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves with log-rank tests to compare the differences between treated and control groups. There was no significant difference across treatments (p > 0.05).

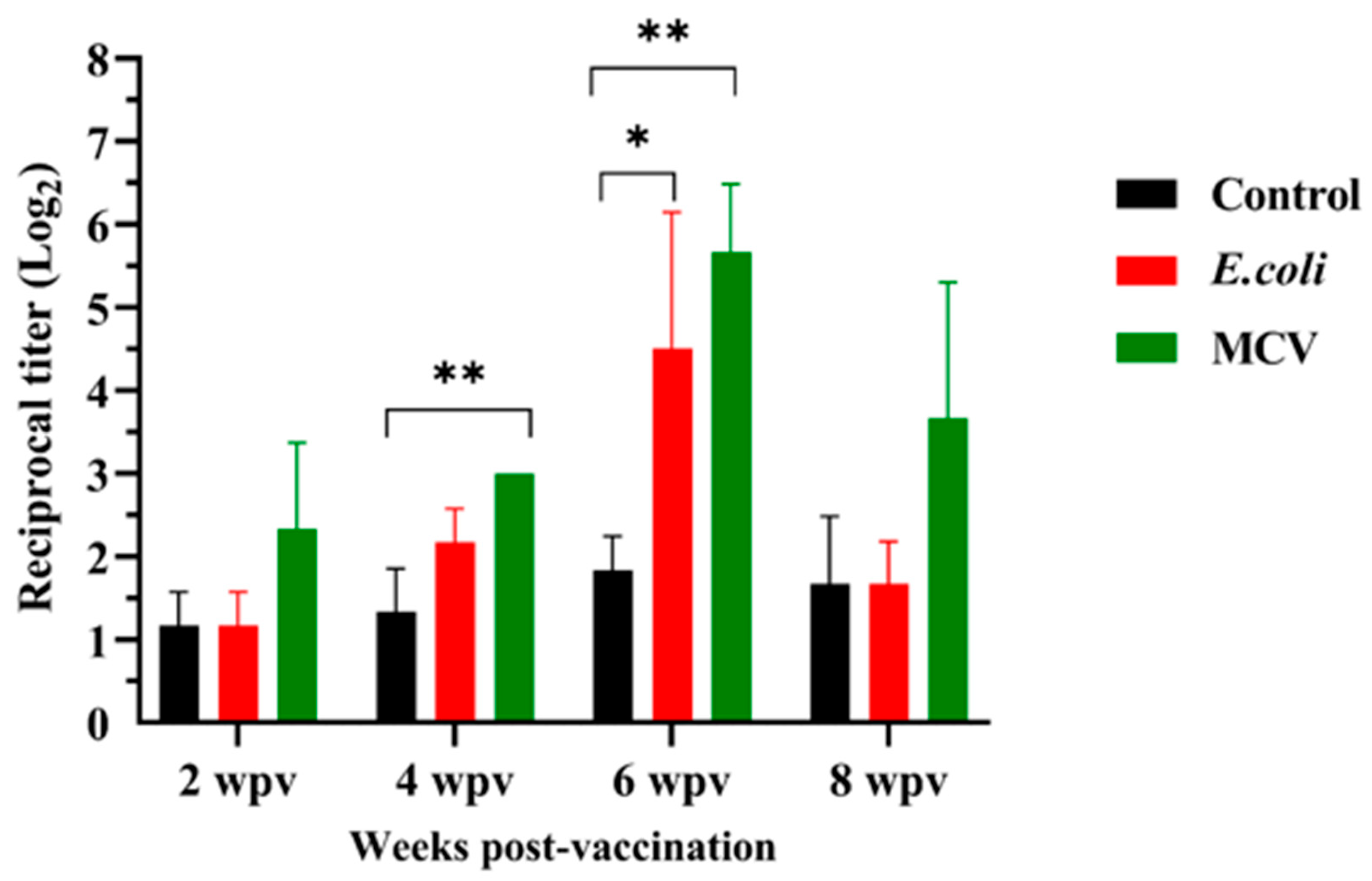

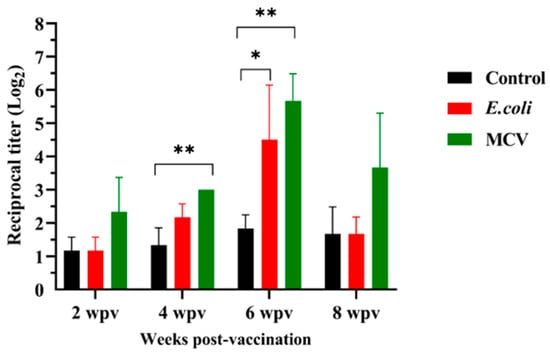

The immunogenicity of the MCV is further supported by the quantification of IgM antibody titers measured at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks post-vaccination (Figure 8). A progressive increase in antibody levels was observed in the MCV-vaccinated group, with a significantly higher response than the control and E. coli-treated groups. Notable elevations were recorded at the 4- and 6-weeks time points, with statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05, respectively). There was no significant difference between the E.coli and MCV groups. These findings confirm the vaccine’s ability to induce a robust and sustained humoral immune response, supporting its potential as an effective preventive measure against bacterial diseases in lumpfish.

Figure 8.

Immunogenic response over time post-vaccination in ELISA. This graph displays the reciprocal titer of IgM antibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in vaccinated lumpfish serum over 8 weeks post-vaccination. Data points represent mean titers with error bars indicating standard deviation. Subjects were divided into three groups: control (black), treated with E. coli (red), and vaccinated with the Multi-epitope Chimeral Vaccine (MCV) (green). Significant increases in antibody titers in the MCV group are indicated by asterisks, with * p ≤ 0.05 and ** p ≤ 0.01, showing a statistically significantly greater immune response compared to both control and E. coli treatments at 4 and 6 weeks post-vaccination. There was no significant difference between the E. coli and MCV groups. Survival data were analyzed using the Duncan multiple-Friedman multiple comparisons test for differences between treated and control groups. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 or p ≤ 0.01 was used for all statistical tests.

4. Discussion

The development of the novel MCV against pathogens affecting finfish is a pivotal advancement in aquaculture. In this study, I utilized computational design and experimental validation to develop a vaccine specifically engineered to bolster the immune defense of lumpfish against common bacterial pathogens, including P. salmonis, V. anguillarum, A. salmonicida, Y. ruckeri, and M. viscosa [50].

To engineer the MCV, the DHODH scaffold was used due to its favorable structural and biochemical properties that support protein stability, solubility, and high expression in recombinant systems [81,82,83,84]. As a member of the flavodoxin-like protein family, DHODH consists of an α/β-barrel domain containing the active site and an α-helical domain forming a tunnel-like structure that leads to the active site. This tunnel has been shown to bind small molecules such as leflunomide, a drug used to treat autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, highlighting the functional and structural versatility of the DHODH scaffold [83,84]. Flavodoxin has been utilized as a structural scaffold in the development of chimeric vaccines against S. agalactiae in Nile tilapia, where five B-cell epitopes from distinct immunogenic proteins (BAC, Rib, SPB1, Sip, and CSF) were engineered into its surface-exposed α-helices [85]. This design enabled effective antigen presentation, resulting in strong immune activation and up to 76% relative percent survival (RPS) following pathogen challenge [85]. While flavodoxin demonstrated promising protection in the fish vaccine, the structural capacity remains limited by its smaller surface area. DHODH was selected for this study because it allows the insertion of up to 11 epitopes, which is more than double the five accommodated by flavodoxin. This allows for broader antigen inclusion and structural integrity. DHODH demonstrated stable folding, high solubility, and efficient expression in both bacterial and fish cell systems, reinforcing its suitability as a scaffold for epitope-based vaccine development. In this study, vaccination with recombinant E. coli expressing the MCV construct resulted in elevated IgM antibody levels and partial protection against multiple bacterial pathogens, suggesting that DHODH may serve as a potential carrier framework for multivalent fish vaccine design.

Molecular properties, like the instability index, aliphatic index, GRAVY score, and extinction coefficient, are key to ensuring the stability of the vaccine under various conditions to induce a strong immune response [86,87]. The designed MCV showed remarkable physicochemical properties, contributing to its effectiveness as a vaccine candidate. Its optimal conformational stability and suitable molecular weight influenced the vaccine stability and immunogenicity. Several studies have indicated that optimal molecular weight (20–40 kDa) and stability of the protein enhance recognition and processing by immune cells, thereby improving the antigen presentation necessary for effective immunization strategies [88]. Experimental studies demonstrated that stabilized variants of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion (RSVF) protein elicited significantly higher neutralizing antibody titers in animal models compared to the protein in its post-fusion form. Furthermore, stabilized RSVF proteins retained their immunogenicity over extended storage periods, addressing challenges in vaccine stability and distribution [89]. Optimal stability results in high pMHC densities, favoring TH1-polarized immune responses. In contrast, proteins with excessive or insufficient stability reduce epitope availability, promoting TH2 responses, instead of TH1 or antibody responses. Extremely destabilized proteins lose conformational B-cell epitopes, while hyper-stabilized proteins resist processing and fail to induce T-cell help, leading to low immunogenicity [88,89].

Codon optimization plays a pivotal role in the development of the MCV by enhancing its expression efficiency in E. coli. This process involves modifying the nucleotide sequence to align with the codon usage preferences of the host organism without altering the resulting amino acid sequence. Such optimization improves mRNA stability and translation efficiency, thereby significantly boosting protein yield, a critical factor for scalable and cost-effective vaccine production [90,91,92]. In this study, the codon-optimized MCV sequence demonstrated a CAI of 1.0, which is considered ideal and indicates perfect alignment with the preferred codon usage of E. coli, ensuring optimal translation efficiency [93]. Additionally, the optimized sequence exhibited a G+C content of 54.61%, well within the desirable range of 30–70%, which supports stable transcription and translation processes [94]. These favorable parameters validate the successful optimization of the MCV construct for heterologous expression. The pET-30a (+) expression vector was selected to further enhance protein expression due to its strong promoter and compatibility with E. coli systems. Similar strategies of combining codon optimization with strategic vector selection have been effectively employed in the development of other multi-epitope vaccines, such as those targeting Kaposi sarcoma and onchocerciasis [95,96].

Live E. coli delivery allows continuous in vivo expression and presentation of the antigen, enhancing its immunostimulatory potential through both humoral and cellular immune pathways. Moreover, the bacterial vector serves as a natural adjuvant due to its intrinsic pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which can activate innate immune receptors and amplify immune responses without requiring additional adjuvants [96]. This approach was intentionally employed as a proof-of-concept platform to assess the intrinsic immunogenic potential of the multiepitope chimeric vaccine (MCV) within a biologically relevant bacterial delivery system commonly used in experimental fish vaccinology. We acknowledge that vaccination with purified or soluble recombinant MCV formulated with defined adjuvants could elicit a more antigen-specific immune response by minimizing background stimulation from bacterial components; however, such formulations may also result in a reduced magnitude of immune activation. In the present study, preliminary solubilization and purification trials of inclusion bodies yielded low protein recovery and partial loss of conformational epitopes critical for immunogenicity. Consequently, the live-cell E. coli–based approach provided a cost-effective and biologically relevant model for the initial in vivo assessment of the immune-protective potential of the MCV construct in lumpfish, while establishing a foundation for future optimization using purified formulations and alternative adjuvant systems.

The in silico simulation data further elucidate the immunogenic potential of the MCV. The simulations predict how the MCV interacts with the immune system, suggesting that it can effectively prime both B-cell and T-cell responses. These responses are crucial as B-cells produce antibodies that bind to and neutralize pathogens, while T-cells help in resolving infections by killing infected cells and aiding in immune regulation.

The immune simulation showed that the MCV vaccine triggers strong humoral and cellular immune responses. It increased IgM and IgG levels, boosted memory B cells, and activated both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, indicating long-term immunity and effective immune memory.

While we already noted that several computational immunology tools are trained and validated mainly on mammalian datasets, this limitation is particularly relevant to the C-ImmSim outputs shown in Figure 3. Because the platform is based on mammalian immune rules, it produces antibody subclasses (IgG1/IgG2) that are not biologically present in teleosts. Therefore, these simulated subclasses should not be interpreted as teleost isotypes or as evidence of teleost class-switching. Instead, they are treated as functional analogs reflecting antibody maturation and secondary-response behavior within the model and are used here only to indicate potential trends in antigen clearance and memory-like kinetics following repeated immunizations. Importantly, conclusions regarding humoral immunity in lumpfish are anchored in empirical, fish-relevant measurements (serum IgM ELISA) and challenge outcomes, whereas the simulation is used to guide interpretation at a comparative and qualitative level. These constraints highlight the need for further development of immune-informatics tools parameterized specifically for teleost species to improve biological fidelity.

The transition of these cells through active, duplicating, resting, and anergic states reflects a robust immune activation followed by a regulatory moderation, which prevents overactivation that could lead to immunopathology. The transitions to resting and anergic states in T-cell populations emphasize the need for further optimization of vaccine formulations and dosing schedules. Maintaining a balance between effective pathogen clearance and immune tolerance is crucial to preventing adverse reactions and ensuring long-term protection. This comprehensive approach to vaccine design highlights the advanced strategies employed in modern vaccinology, emphasizing the integration of both humoral and cellular immunity. Previous research has demonstrated that vaccines capable of inducing a broad immune response tend to offer more effective protection and longer-lasting immunity [97,98,99]. By integrating multiple epitopes that stimulate various arms of the immune system, the MCV can provide a robust platform for defending lumpfish against a spectrum of bacterial pathogens.

TEM provided an insightful visualization of the cellular architecture of E. coli cells expressing the MCV (Figure 5). The contrast between control E. coli cells and those expressing the MCV highlights the formation of distinct inclusion bodies, which are absent in the control cells. These inclusion bodies represent localized regions within the bacterial cytoplasm where the overexpressed MCV protein aggregates. The formation of inclusion bodies suggests that the target protein is expressed and becomes insoluble. Studies have shown that inclusion bodies favor vaccine immunogenicity. Inclusion bodies can enhance dendritic cell responses, facilitating T cell activation due to their particulate nature, which mimics pathogen attacks and stimulates the immune system [100]. For instance, intratumorally injected inclusion bodies of therapeutic proteins induced tumor regression [101]. In another study, cytokine-based inclusion bodies BTNFα and IBCCL4, administered intraperitoneally, conferred protection to zebrafish from a lethal infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fish treated with 300 μg of IBTNFα showed 100% relative percent survival (RPS), while a significantly lower dose of 75 μg of IBCCL4 still achieved 91% RPS, highlighting its potency even at reduced concentration [102]. Additionally, their inherent stability and high antigenic content make them excellent candidates for vaccines that require persistent antigen exposure to induce a prolonged immune response [100,103]. Also, while inclusion bodies typically contain misfolded proteins, they can still present epitopes that are effectively recognized by T cells, which is crucial for the cellular immune response against many viral and bacterial pathogens [104,105].

The immune response in lumpfish vaccinated with MCV was robust, as evidenced by significantly elevated IgM antibody titers at specific post-vaccination intervals compared to controls. Notably, while IgM levels in the MCV-vaccinated group were significantly higher than those in the PBS control group, no statistically significant difference was observed between the MCV and E. coli vector control groups. This indicates that bacterial components inherent to the E. coli delivery system likely contributed to immune stimulation. However, the relative percent survival (RPS) observed in the challenge trial revealed only partial protection, indicating a gap between immunogenicity and protective efficacy. The protective effect was pathogen-dependent, with the highest RPS recorded for P. salmonis and slightly lower RPS recorded for extracellular bacteria such as V. anguillarum and A. salmonicida. The lack of a statistically significant survival advantage of the MCV over the E. coli control further suggests that vector-associated innate immune activation may have masked differences in protective efficacy attributable solely to the MCV antigens. This differential efficacy may be attributed to a better antigenic match or stronger immune responsiveness to intracellular pathogens. Additionally, factors such as antigen design, vaccine dosage, and the antigenic complexity of the pathogens may have contributed to the variable effectiveness of the vaccine under practical conditions, despite being administered via injection.

Future research should focus on optimizing the vaccine composition and exploring alternative delivery methods that could enhance its effectiveness. Studies could also investigate the vaccine’s performance in diverse aquaculture settings and against different bacterial strains, which might exhibit varying pathogenic behaviors. Additionally, longitudinal studies to monitor the long-term immunity and health outcomes of vaccinated fish populations would provide invaluable data to refine vaccination strategies. Moreover, expanding the application of similar multiepitope chimeric vaccines to other aquaculture species could significantly impact the industry, offering a proactive approach to managing disease outbreaks. Collaborations between research institutions and industry stakeholders could facilitate the translation of laboratory findings into practical solutions, enhancing the sustainability and productivity of aquaculture operations.

5. Conclusions

This study has effectively demonstrated the potential of a novel MCV to enhance the immune defenses of lumpfish against several frequently occurring bacterial pathogens in aquaculture. We developed a vaccine that evokes a strong immune response in lumpfish and shows promise in improving survival rates under pathogen challenge conditions by utilizing a strategic integration of in silico design, molecular biology techniques, and experimental validation. The findings from this research underline the importance of epitope selection and protein stability in the design of effective vaccines. The MCV showcased here, through its robust physicochemical properties and the elicited immune response, illustrates the critical interplay between vaccine design and immune system engagement. However, despite the promising immunogenicity and elevated IgM titers observed in vaccinated fish, the actual survival rates post-challenge indicate that further optimization might be necessary to translate immunogenic potential into practical protective efficacy. Future studies should focus on refining the vaccine formulation, exploring alternative delivery methods, and extending the research to other species within aquaculture to broaden the applicability of this vaccine strategy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes11020083/s1, Figure S1: Structure Assessment of MCV on MolProbity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.C.-O. and J.S.; Methodology: J.C.-O., T.C., I.V., H.G., A.H., O.O., S.C., V.I.M. and J.S.; Investigation: J.C.-O. and J.S.; Writing—original draft: J.C.-O. and J.S.; Resources: J.S.; Writing—review and editing: J.C.-O., T.C., I.V., H.G., A.H., O.O., S.C., V.I.M. and J.S.; Visualization: J.C.-O. and J.S.; Supervision: J.S.; Funding acquisition: J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Ocean Frontier Institute through an award from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (sub-module J3), and the NSERC-Discovery grant (RGPIN-2018-05942).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This experiment was performed following the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Institutional Animal Care Committee (https://www.mun.ca/research/about/acs/acc/; accessed on 31 December 2025) (protocols #17-01-JS; #17-02-JS) and biohazard license L-01 (approval date: 17 September 2024).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCIP | 5-Bromo-4-Chloro-3-Indolyl Phosphate |

| CAI | Codon Adaptation Index |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

| CHAB | Cysteine Heart Agar with Blood |

| CHSE-214 | Chinook Salmon Embryo Cell Line (ATCC CHSE-214) |

| DHODH | Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EPON | Epoxy Resin for Embedding |

| GRAVY | Grand Average of Hydropathicity |

| Hsp | Heat Shock Protein |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| IMAC | Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography |

| IPTG | Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside |

| JBARB | Dr. Joe Brown Aquatic Research Building |

| JCat | Java Codon Adaptation Tool |

| LB | Lysogeny Broth |

| MCV | Multiepitope Chimeric Vaccine |

| MCS | Multiple Cloning Site |

| NBT | Nitro Blue Tetrazolium |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PBS-T | Phosphate-Buffered Saline with Tween-20 |

| PIT | Passive Integrated Transponder |

| PSSM | Position-Specific Scoring Matrix |

| QMEAN | Qualitative Model Energy Analysis |

| RPS | Relative Percent Survival |

| rpm | Revolutions Per Minute |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy/Microscope |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| wpi | Weeks Post-Immunization |

| pI | Isoelectric Point |

References

- Brooker, A.; Papadopoulou, A.; Gutierrez-Rabadan, C.; Rey Planellas, S.; Davie, A.; Migaud, H. Sustainable production and use of cleaner fish for the biological control of sea lice: Recent advances and current challenges. Vet. Rec. 2018, 183, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.; Treasurer, J.W.; Pooley, C.L.; Keay, A.J.; Lloyd, R.; Imsland, A.K.; Garcia de Leaniz, C. Use of lumpfish for sea-lice control in salmon farming: Challenges and opportunities. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, A.; Sugimoto, K.; Itou, D.; Kamaishi, T.; Miwa, S.; Iida, T. Atypical Aeromonas salmonicida Infection in Cultured Marbled Sole Pleuronectes yokohamae. Fish Pathol. 2006, 41, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.; Larsen, J.L. First report on outbreak of furunculosis in turbot Scophthalmus maximus caused by Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida in Denmark. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 1996, 16, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, T.V.; Ravindranath, K.; Sreeraman, P.K.; Subba Rao, M.V. Aeromonas salmonicida associated with mass mortality of Cyprinus carpio and Oreochromis mossambicus in a freshwater reservoir in Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Aquac. Trop. 1994, 9, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, R.; Smith, P.; Dalsgaard, I.; Nilsen, H.; Kongshaug, H.; Samuelsen, O. Winter ulcer disease of post-smolt Atlantic salmon: An unsuitable case for treatment? Aquaculture 2006, 253, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, R.; Samuelsen, O.; Andersen, K.; Lunestad, B.; Nilsen, H.; Dalsgaard, I.; Smith, P. Attempt to validate breakpoint MIC values estimated from pharmacokinetic data obtained during oxolinic acid therapy of winter ulcer disease in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture 2004, 238, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggero, A.; Castro, H.; Sandino, A. First isolation of Piscirickettsia salmonis from coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum), and rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), during the freshwater stage of their life cycle. J. Fish Dis. 2006, 18, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauel, M.J.; Miller, D.L.; Frazier, K.; Liggett, A.D.; Styer, L.; Montgomery-Brock, D.; Brock, J. Characterization of a piscirickettsiosis-like disease in Hawaiian tilapia. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2003, 53, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iregui, C.A.; Vasquez, G.M.; Rey, A.L.; Verjan, N. Piscirickettsia-like organisms as a cause of acute necrotic lesions in Colombian tilapia larvae. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2011, 23, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Yamada, H.; Shimizu, H.; Yuasa, K.; Kamaishi, T.; Oseko, N.; Iida, T. Characteristics and pathogenicity of brown pigment-producing Vibrio anguillarum isolated from Japanese flounder [Paralichthys olivaceus]. Fish Pathol. Jpn. 2006, 41, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guguianu, E.; Vulpe, V. Yersiniosis outbreak in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykis) at a fish farm from northern Romania. Cercet. Agron. Mold. 2009, 75–80. Available online: https://repository.iuls.ro/xmlui/handle/20.500.12811/2629 (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Rodríguez, L.A.; Castillo, A.; Gallardo, C.S.; Nieto, T.P. Outbreaks of Yersinia ruckeri in rainbow trout in north west of Spain. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 1999, 19, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu-Osazuwa, J.; Cao, T.; Vasquez, I.; Gnanagobal, H.; Hossain, A.; Dang, M.; Onireti, O.; Hall, J.R.; Santander, J. Experimental co-infection of lumpfish with sublethal doses of Aeromonas salmonicida and Vibrio anguillarum causes increased mortality. Aquaculture 2025, 609, 742952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanagobal, H.; Chakraborty, S.; Vasquez, I.; Chukwu-Osazuwa, J.; Cao, T.; Hossain, A.; Dang, M.; Valderrama, K.; Kumar, S.; Bindea, G.; et al. Transcriptome profiling of lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) head kidney to Renibacterium salmoninarum at early and chronic infection stages. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2024, 156, 105165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Gnanagobal, H.; Hossain, A.; Cao, T.; Vasquez, I.; Boyce, D.; Santander, J. Inactivated Aeromonas salmonicida impairs adaptive immunity in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus). J. Fish Dis. 2024, 47, e13944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onireti, O.B.; Cao, T.; Vasquez, I.; Chukwu-Osazuwa, J.; Gnanagobal, H.; Hossain, A.; Machimbirike, V.I.; Hernandez-Reyes, Y.; Khoury, A.; Khoury, A.; et al. Evaluation of the protective efficiency of an autogenous Vibrio anguillarum vaccine in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) under controlled and field conditions in Atlantic Canada. Front. Aquac. 2023, 2, 1306503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Hossain, A.; Cao, T.; Gnanagobal, H.; Segovia, C.; Hill, S.; Monk, J.; Porter, J.; Boyce, D.; Hall, J.R.; et al. Multi-Organ Transcriptome Response of Lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) to Aeromonas salmonicida Subspecies salmonicida Systemic Infection. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazzaoui, A.; Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Al-Allaf, F.A.; Bogari, N.M.; Al-Dehlawi, S.; Qari, S.H. Strategies for Vaccination: Conventional Vaccine Approaches Versus New-Generation Strategies in Combination with Adjuvants. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisse, M.; Vrba, S.M.; Kirk, N.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. Emerging Concepts and Technologies in Vaccine Development. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Bruce, T.J.; Jones, E.M.; Cain, K.D. A Review of Fish Vaccine Development Strategies: Conventional Methods and Modern Biotechnological Approaches. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathor, G.S.; Swain, B. Advancements in Fish Vaccination: Current Innovations and Future Horizons in Aquaculture Health Management. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oli, A.N.; Obialor, W.O.; Ifeanyichukwu, M.O.; Odimegwu, D.C.; Okoyeh, J.N.; Emechebe, G.O.; Adejumo, S.A.; Ibeanu, G.C. Immunoinformatics and Vaccine Development: An Overview. Immunotargets Ther. 2020, 9, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiman, S.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, A.A.; Alanazi, A.M.; Samad, A.; Ali, S.L.; Li, C.; Ren, Z.; Khan, A.; Khattak, S. Vaccinomics-based next-generation multi-epitope chimeric vaccine models prediction against Leishmania tropica—A hierarchical subtractive proteomics and immunoinformatics approach. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1259612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaan, S.; Shah, M.; Ullah, N.; Amjad, A.; Javed, M.S.; Nishan, U.; Mustafa, G.; Nawaz, H.; Ahmed, S.; Ojha, S.C. Multi-epitope chimeric vaccine designing and novel drug targets prioritization against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 971263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, R.C.O.; Tiwari, S.; Ferreira, L.C.G.; Oliveira, F.M.; Lopes, M.D.; Passos, M.J.F.; Maia, E.H.B.; Taranto, A.G.; Kato, R.; Azevedo, V.A.C.; et al. Immunoinformatics Design of Multi-Epitope Peptide-Based Vaccine Against Schistosoma mansoni Using Transmembrane Proteins as a Target. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 621706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, S.; Bahal, R.K.; Dhiman, R.; Singh, R. Antigen identification strategies and preclinical evaluation models for advancing tuberculosis vaccine development. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Shamkh, I.M.; Khan, M.S.; Lotfy, M.M.; Nzeyimana, J.B.; Abutayeh, R.F.; Hamdy, N.M.; Hamza, D.; Chanu, N.R.; Khanal, P.; et al. Multi-Epitope Vaccine Design against Monkeypox Virus via Reverse Vaccinology Method Exploiting Immunoinformatic and Bioinformatic Approaches. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R.M.; Fujinami, R.S. Pathogenic epitopes, heterologous immunity and vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, J.; Mahapatra, S.R.; Raj, T.K.; Kaur, T.; Jain, P.; Tiwari, A.; Patro, S.; Misra, N.; Suar, M. Designing a novel multi-epitope vaccine to evoke a robust immune response against pathogenic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacterium. Gut Pathogens 2022, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawam, A.S.; Alwethaynani, M.S. Construction of an aerolysin-based multi-epitope vaccine against Aeromonas hydrophila: An in silico machine learning and artificial intelligence-supported approach. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1369890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ismail, S. Vaccinomics to Design a Novel Single Chimeric Subunit Vaccine for Broad-Spectrum Immunological Applications targeting Nosocomial Enterobacteriaceae Pathogens. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 146, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.I.; Mahfuj, S.; Alam, M.A.; Ara, Y.; Sanjida, S.; Mou, M.J. Immunoinformatic Approaches to Identify Immune Epitopes and Design an Epitope-Based Subunit Vaccine against Emerging Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV). Aquac. J. 2022, 2, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahdari, B.; Sarkoohi, P.; Nezhad, F.G.; Shahbazi, B.; Ahmadi, K. Design of multi-epitope vaccine candidate based on OmpA, CarO and ZnuD proteins against multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, M.; Sanjida, S. In Silico-Based Vaccine Design Against Hepatopancreatic Microsporidiosis in Shrimp. Trends Sci. 2022, 19, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, F.; Cohan, R.A.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Samimi, H.; Haghpanah, V. An in-silico approach to develop of a multi-epitope vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 envelope (E) protein. Res. Sq. 2020, rs.3.rs-30374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, S.A.; Shamsir, M.S.; Ishak, N.F.; Low, C.F.; Azemin, W.A. Riding the wave of innovation: Immunoinformatics in fish disease control. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunita; Sajid, A.; Singh, Y.; Shukla, P. Computational tools for modern vaccine development. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2020, 16, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, K.; Poh, C.L. The Promising Potential of Reverse Vaccinology-Based Next-Generation Vaccine Development over Conventional Vaccines against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Li, T.; Gu, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, N. Molecular engineering tools for the development of vaccines against infectious diseases: Current status and future directions. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2023, 22, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Hu, X.; Miao, L.; Chen, J. Current status and development prospects of aquatic vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1040336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plant, K.P.; LaPatra, S.E.; Cain, K.D. Vaccination of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), with recombinant and DNA vaccines produced to Flavobacterium psychrophilum heat shock proteins 60 and 70. J. Fish Dis. 2009, 32, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marana, M.H.; Jørgensen, L.v.G.; Skov, J.; Chettri, J.K.; Holm Mattsson, A.; Dalsgaard, I.; Kania, P.W.; Buchmann, K. Subunit vaccine candidates against Aeromonas salmonicida in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.Y.; Megat Mazhar Khair, M.H.; Song, A.A.L.; Masarudin, M.J.; Loh, J.Y.; Chong, C.M.; Beardall, J.; Teo, M.Y.M.; In, L.L.A. Recombinant lactococcal-based oral vaccine for protection against Streptococcus agalactiae infections in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2024, 149, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.I.; Mou, M.J.; Sanjida, S. Application of reverse vaccinology to design a multi-epitope subunit vaccine against a new strain of Aeromonas veronii. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumchan, A.; Proespraiwong, P.; Sawatdichaikul, O.; Phurahong, T.; Hirono, I.; Unajak, S. Computational design of novel chimeric multiepitope vaccine against bacterial and viral disease in tilapia (Oreochromis sp.). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Kumar, P.; Nafidi, H.-A.; Almaary, K.S.; Wondmie, G.F.; Kumar, A.; Bourhia, M. Immunoinformatics approaches in developing a novel multi-epitope chimeric vaccine protective against Saprolegnia parasitica. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourin, M.; Tuzon, C.T.; Fisher, T.S.; Zakian, V.A. A flexible protein linker improves the function of epitope-tagged proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2007, 24, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadilah, F.; Paramita, R.I.; Erlina, L.; Istiadi, K.A.; Wuyung, P.E.; Tedjo, A. Linker optimization in breast cancer multiepitope peptide vaccine design based on molecular study. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Life Sciences and Biotechnology (ICOLIB 2021), Virtual, 15–16 November 2021; pp. 528–538. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu-Osazuwa, J.; Cao, T.; Vasquez, I.; Gnanagobal, H.; Hossain, A.; Machimbirike, V.I.; Santander, J. Comparative Reverse Vaccinology of Piscirickettsia salmonis, Aeromonas salmonicida, Yersinia ruckeri, Vibrio anguillarum and Moritella viscosa, Frequent Pathogens of Atlantic Salmon and Lumpfish Aquaculture. Vaccines 2022, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.e.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Studer, G.; Robin, X.; Bienert, S.; Tauriello, G.; Schwede, T. The structure assessment web server: For proteins, complexes and more. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W318–W323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, S.; Waterhouse, A.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Tauriello, G.; Studer, G.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository—New features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 45, D313–D319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, V.B.; Arendall, W.B., 3rd; Headd, J.J.; Keedy, D.A.; Immormino, R.M.; Kapral, G.J.; Murray, L.W.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.J.; Headd, J.J.; Moriarty, N.W.; Prisant, M.G.; Videau, L.L.; Deis, L.N.; Verma, V.; Keedy, D.A.; Hintze, B.J.; Chen, V.B.; et al. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]