Emergence of Atlantic Salmon Fry in Relation to Redd Sediment Infiltration and Dissolved Oxygen in Small Coastal Streams

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

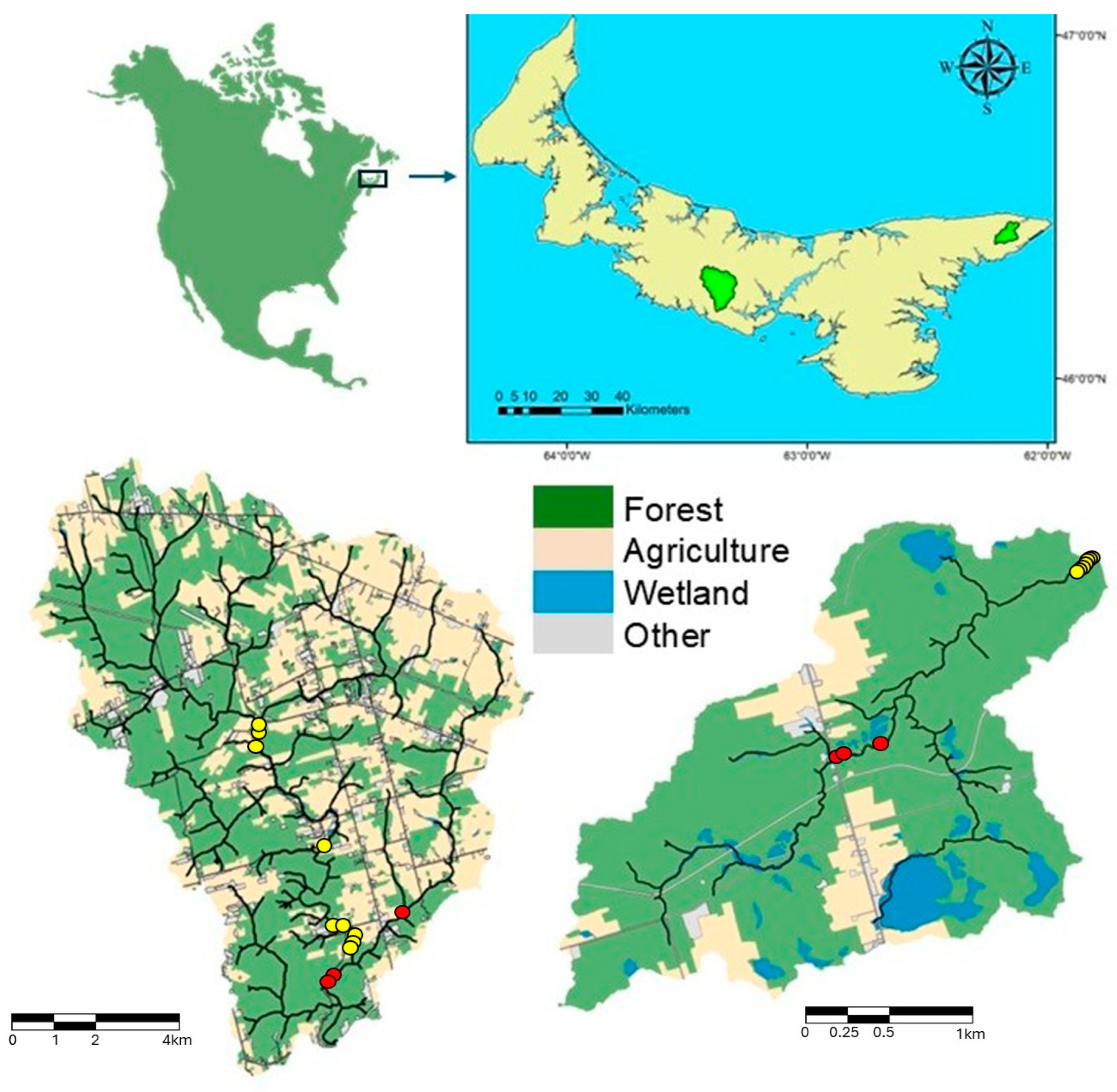

2.2. Study Sites

2.3. Redd Selection

2.4. Environmental Variables

2.4.1. Dissolved Oxygen

2.4.2. Water Temperature

2.4.3. Water Level and Flow Velocity

2.4.4. Redd Substrate and Stream Suspended Solids Characterization

2.5. Emergence Trapping

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Redd Environmental Variables

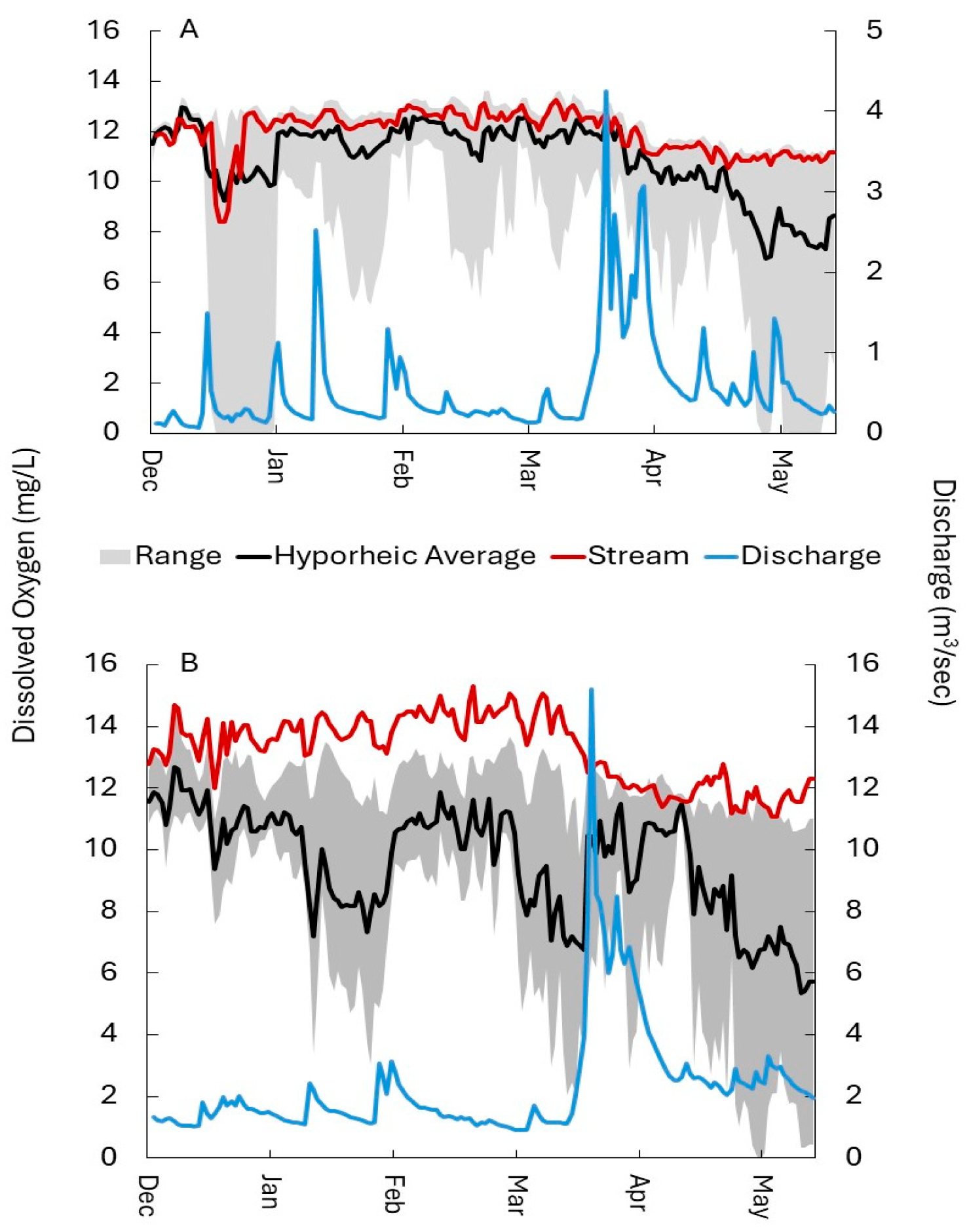

3.1.1. Dissolved Oxygen

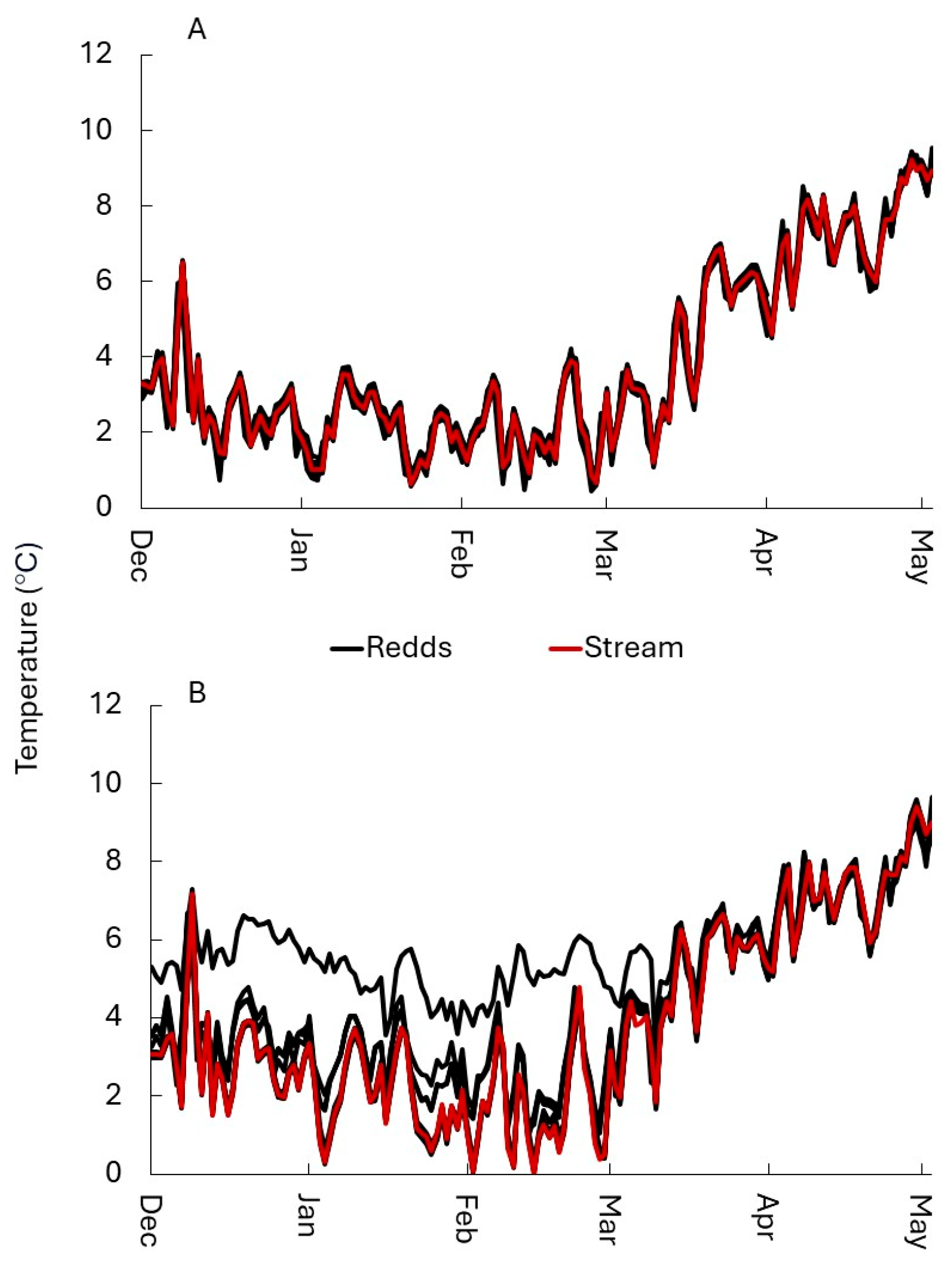

3.1.2. Temperature

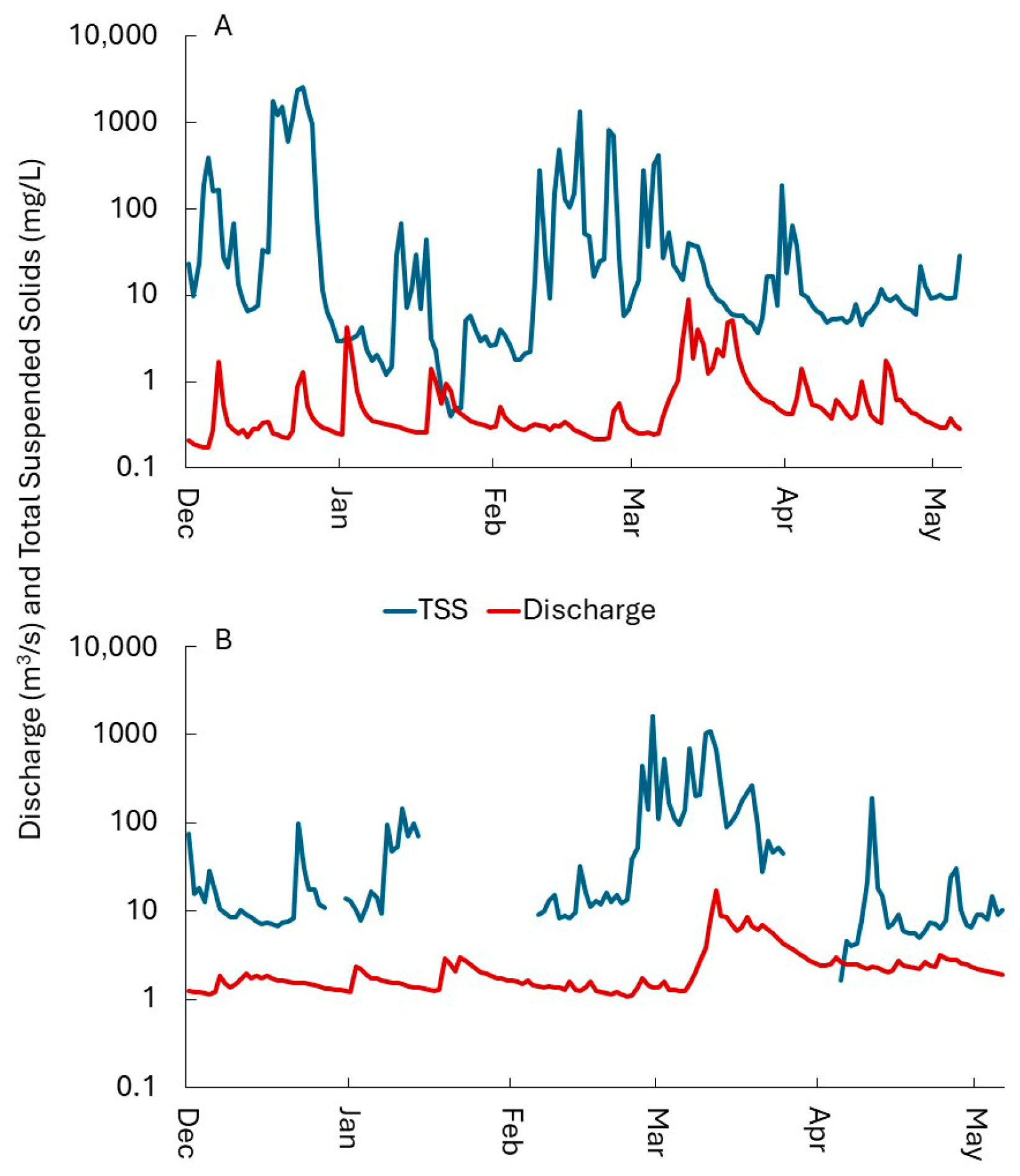

3.1.3. Substrate, Sediment Infiltration, Velocity and Total Suspended Solids

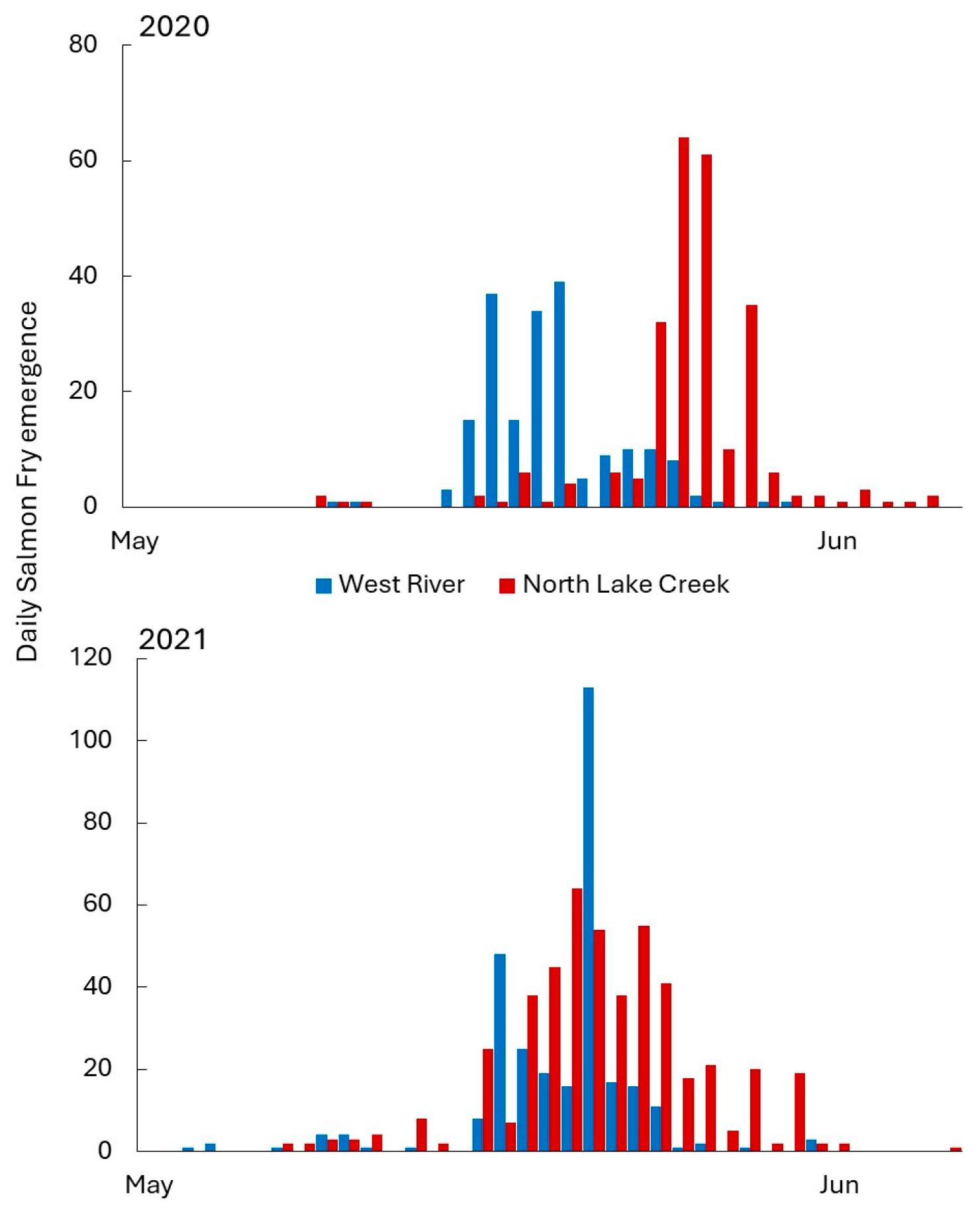

3.2. Egg Size and Atlantic Salmon Fry Emergence

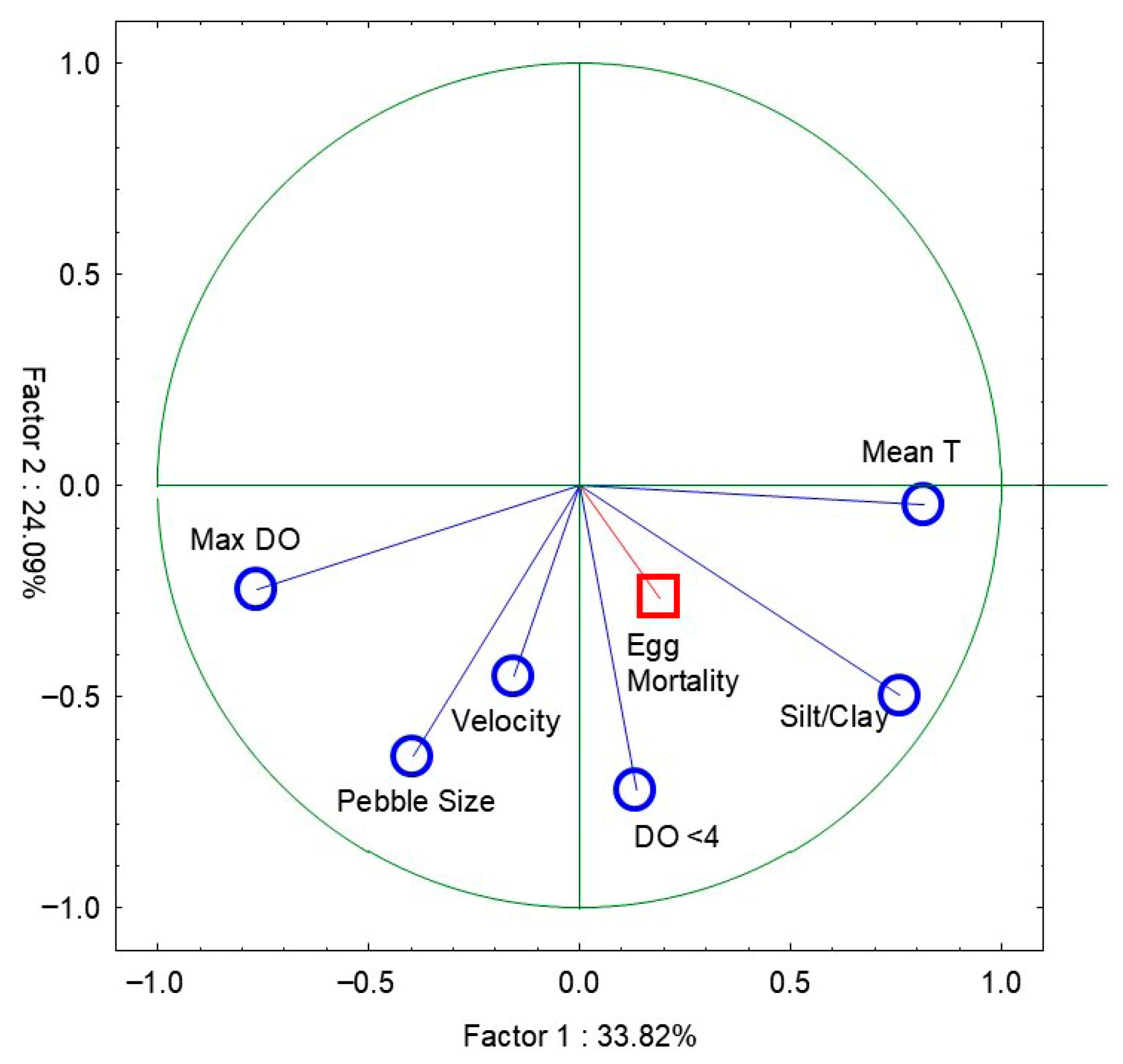

3.3. Emergence and Mortality Related to Environmental Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PEI | Prince Edward Island |

| DFO | The Department of Fisheries and Oceans |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CDD | Cumulative Degree Days |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

References

- Moss, B.; Hering, D.; Green, A.J.; Aidoud, A.; Becares, E.; Beklioglu, M.; Bennion, H.; Boix, D.; Brucet, S.; Carvalho, L.; et al. Climate change and the future of freshwater biodiversity in Europe: A primer for policy-makers. Freshw. Rev. 2009, 2, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Logez, M.; Xu, J.; Tao, S.; Villéger, S.; Brosse, S. Human impacts on global freshwater fish biodiversity. Science 2021, 371, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, G. Overview of the status of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in the North Atlantic and trends in marine mortality. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSPAR Commission. Case Reports for the OSPAR List of Threatened and/or Declining Species and Habitats; Ospar Commission: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://oap.ospar.org/en/ospar-assessments/committee-assessments/biodiversity-committee/status-assesments/atlantic-salmon (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Pardo, S.A.; Hutchings, J.A. Estimating marine survival of Atlantic salmon using an inverse matrix approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICES. Atlantic salmon from North America. In Report of the ICES Advisory Committee; ICES Advice; ICES: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, N.B.; Thorpe, J.E. Determinants of geographical variation in the age of seaward-migrating salmon, Salmo salar. J. Anim. Ecol. 1990, 59, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.F.; Bowlby, H.D.; Sam, D.L.; Amiro, P.G. Review of DFO Science Information for Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) Populations in the Southern Upland Region of Nova Scotia; Res. Doc. 2009/081; DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (Secrétariat Canadien de Consultation Scientifique): Ottawa, Canada, 2010; Volume VI, 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, J.J.; Beirne, M.M.; Larsen, K.; Barry, D.; Stenberg, K.; McHenry, M.L. Aquatic ecology of the Elwha River estuary prior to dam removal. In Coastal Habitats of the Elwha River, Washington—Biological and Physical Patterns and Processes Prior to Dam Removal; Scientific Investigations Report 2011-5120-7. Chapter 7; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roloson, S.D.; Knysh, K.M.; Coffin, M.R.S.; Gormley, K.L.; Pater, C.C.; van den Heuvel, M.R. Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) habitat overlap with wild Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) in natural streams: Do habitat and landscape factors override competitive interactions? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 75, 1949–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, H.P.; Bergeron, N.E. Effect of fine sediment infiltration during the incubation period on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) embryo survival. Hydrobiologia 2006, 563, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, B.K.; Huff, D.D.; Quinn, T.P.; Santora, J.A.; Gomes, D.G.E.; Vasbinder, K.; Barnas, K.A.; Burke, B.J.; Courtney, M.B.; Crozier, L.G.; et al. When, where, and why salmon become vulnerable to predation. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2025, 82, fsaf162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, S.; Diserud, O.H.; Fiske, P.; Hindar, K. Widespread genetic introgression of escaped farmed Atlantic salmon in wild salmon populations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016, 73, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhun, A.S.; Karlsbakk, E.; Skaala, Ø.; Solberg, M.F.; Wennevik, V.; Harvey, A.; Meier, S.; Fjeldheim, P.T.; Andersen, K.C.; Glover, K.A. Most of the escaped farmed salmon entering a river during a 5-year period were infected with one or more viruses. J. Fish Dis. 2024, 47, e13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, C.M.; Roloson, S.D.; Knysh, K.M.; Pavey, S.A.; Cairns, D.K.; Gilmour, R.F.; van den Heuvel, M.R. Population Genetics of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.-S.; Bourret, V.; Dionne, M.; Bradbury, I.; O’Reilly, P.; Kent, M.; Chaput, G.; Bernatchez, L. Conservation genomics of anadromous Atlantic salmon across its North American range: Outlier loci identify the same patterns of population structure as neutral loci. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 5680–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairns, D.K.; MacFarlane, R.E. The Status of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) on Prince Edward Island (SFA 17) in 2013; Res. Doc. 2015/019; DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (Secrétariat Canadien de Consultation Scientifique): Ottawa, Canada, 2015; Volume IV, 25p. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, A.; St-Hilaire, A.; Courtenay, S.C.; van den Heuvel, M.R. Monitoring stream sediment loads in response to agriculture in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirabahenda, Z.; St-Hilaire, A.; Courtenay, S.C.; Alberto, A.; van den Heuvel, M.R. A modelling approach for estimating suspended sediment concentrations for multiple rivers influenced by agriculture. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 2209–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugden, G.; Jiang, Y.; van den Heuvel, M.R.; Vandermeulen, H.; MacQuarrie, K.T.B.; Crane, C.J.; Raymond, B.G. Nitrogen Loading Criteria for Estuaries in Prince Edward Island; Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Pêches et Océans Canada): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014; Volume VII, 43p. [Google Scholar]

- Roloson, S.D.; Knysh, K.M.; Landsman, S.J.; James, T.L.; Hicks, B.J.; van den Heuvel, M.R. The lifetime migratory history of anadromous brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis): Insights and risks from pesticide-induced fish kills. Fishes 2022, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Heuvel, M.R. Forest Contribution to Ecosystem Services Provided by PEI Streams; Report provided to the PEI Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate Change; Muskego Environmental: Charlottetown, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cunjak, R.A.; Cairns, D.K.; Guignion, D.L.; Angus, R.B.; MarFarlane, R.A. Survival of eggs and alevins of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) in relation to fine sediment deposition. Effects of land use practices on fish, shellfish, and their habitats on Prince Edward Island. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 2408, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, A.; Courtenay, S.C.; St-Hilaire, A.; van den Heuvel, M.R. Factors Influencing Brook Trout (Salvelinus frontalis) Egg Survival and Development in Streams Influenced by Agriculture. J. FisheriesSciences.com 2017, 11, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- DFO. Update of Stock Status Indicators of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) in DFO Gulf Region Salmon Fishing Areas 15–18 for 2022; Sci. Resp. 2023/035; DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (Secrétariat Canadien de Consultation Scientifique): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, J.; McNeill, A. Fecundity and Sexual Maturity in Select Nova Scotia Trout Populations; Unpublished Report; Inland Fisheries Division, Nova Scotia Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture: Pictou, NS, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J.E.; Chaput, G. Spawning history influence on fecundity, egg size, and egg survival of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) from the Miramichi River, New Brunswick, Canada. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolman, G.M. A method of sampling coarse river-bed material. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1954, 35, 951–956. [Google Scholar]

- Newbury, R.W. Dynamics of flow. In Methods in Stream Ecology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley, J.J.; Shepard, B.B.; Graham, P.R. Emergence of salmonids from incubation boxes and natural redds: Techniques and observations. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1986, 6, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, S.; Sear, D.; Carling, P. A field-based assessment of oxygen supply to incubating Atlantic salmon embryos. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 3087–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, J.M.; Cunjak, R.A. The influence of abiotic incubation conditions on the winter mortality of wild salmonid embryos. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 1098–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirabahenda, Z.; St-Hilaire, A.; Courtenay, S.C.; van den Heuvel, M.R. Assessment of the effective width of riparian buffer strips to reduce suspended sediment in an agricultural landscape using ANFIS and SWAT models. CATENA 2020, 195, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, M.F.; Bergeron, N.E.; Bérubé, F.; Pouliot, M.-A.; Johnston, P. Interactive effects of substrate sand and silt contents, redd-scale hydraulic gradients, and interstitial velocities on egg-to-emergence survival of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2004, 61, 2271–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Bergeron, N.E.; Lapointe, M.F.; Bérubé, F. Effects of silt and very fine sand dynamics in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) redds on embryo hatching success. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 63, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, D.A.; Jones, J.I.; Collins, A.L.; Hulin, A.; Burke, N.; Bateman, S.; Pattison, I.; Naden, P.S. Does fine sediment source as well as quantity affect salmonid embryo mortality and development? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, D.A.; Pattison, I.; Collins, A.L.; Newson, M.D.; Jones, J.I.; Naden, P.S.; Carling, P.A. Factors controlling the temporal variability in dissolved oxygen regime of salmon spawning gravels. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.E.; Lapointe, M. Intergranular flow velocity through salmonid redds: Sensitivity to fines infiltration from low intensity sediment transport events. River Res. Appl. 2005, 21, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, G.H.; Refstie, T.; Gjerde, B. Evaluation of milt quality of Atlantic salmon. Aquaculture 1991, 95, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, S.E.; Einum, S.; Fleming, I.A.; Holt, W.V.; Gage, M.J.G. Assessing risks of invasion through gamete performance: Farm Atlantic salmon sperm and eggs show equivalence in function, fertility, compatibility and competitiveness to wild Atlantic salmon. Evol. Appl. 2014, 7, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCrimmon, H.R.; Gots, B.L. Laboratory observations on emergent patterns of juvenile Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, relative to sediment loadings of test substrate. Can. J. Zool. 1986, 64, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.T.; Clark, T.D.; Elliott, N.G.; Frappell, P.B.; Andrewartha, S.J. Physiological effects of dissolved oxygen are stage-specific in incubating Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). J. Comp. Physiol. 2019, 189, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, G.L. Survival of eggs and alevins of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in relation to the chemistry of interstitial water in redds in some acidic streams of Atlantic Canada. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1985, 42, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngson, A.; Malcolm, I.; Thorley, J.; Bacon, P.; Soulsby, C. Long-residence groundwater effects on incubating salmonid eggs: Low hyporheic oxygen impairs embryo development. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2004, 61, 2278–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, J.; Blais, C.; Lapointe, M.; Bérubé, F.; Bergeron, N.; Magnan, P. Asphyxiation and entombment mechanisms in fines rich spawning substrates: Experimental evidence with brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) embryos. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2012, 69, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.J.; Johnsen, B.O. The functional relationship between peak spring floods and survival and growth of juvenile Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) and Brown Trout (Salmo trutta). Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.M.; Proulx, C.L.; Veilleux, M.A.N.; Levert, C.; Bliss, S.; André, M.-E.; Lapointe, N.W.R.; Cooke, S.J. Clear as mud: A meta-analysis on the effects of sedimentation on freshwater fish and the effectiveness of sediment-control measures. Water Res. 2014, 56, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 9 December to 18 April | 19 April to 20 May | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Lake Creek | West River | North Lake Creek | West River | |

| Range of Individual Means (mg/L) | 9.9 to 12.6 | 9.3 to 11.3 | 3.6 to 11.3 | 3.0 to 11.2 |

| Mean (SD, n, mg/L) | 11.5 (1.7, 6) | 10.6 (2.0, 6) | 8.6 (1.6, 5) | 8.3 (1.9, 6) |

| Above 6 mg/L | 87 to 100% | 81 to 100% | 34 to 100% | 13 to 100% |

| Below 6 mg/L | 0 to 13% | 0 to 19% | 0 to 66% | 0 to 87% |

| Below 4 mg/L | 0 to 13% | 0 to 19% | 0 to 55% | 0 to 87% |

| Below 2 mg/L | 0 to 12% | 0 to 1% | 0 to 51% | 0 to 48% |

| Days | 130 | 130 | 32 | 32 |

| Substrate Category | North Lake Creek | West River |

|---|---|---|

| Pebble (>4 mm) | 54.9 (1.69) | 57.7 (3.27) |

| Granule (2.1–4 mm) | 6.70 (0.49) | 6.45 (0.61) |

| Coarse sand (501 µm–2 mm) | 14.8 (1.45) | 9.73 (1.29) * |

| Medium sand (251–500 µm) | 13.1 (0.62) | 12.5 (1.82) |

| Fine sand (126–250 µm) | 7.36 (0.65) | 8.56 (1.20) |

| Very fine sand (64–125 µm) | 2.16 (0.22) | 3.22 (0.49) * |

| Silt (39–63 µm) | 0.46 (0.05) | 0.90 (0.15) * |

| Clay (<39 µm) | 0.52 (0.13) | 0.98 (0.18) * |

| Wobble Pebble Count | 35.3 (6.11) | 44.8 (2.29) |

| Velocity (f/s) at 0 cm | 1.45 (0.89) | 1.59 (1.05) |

| Velocity (f/s) at 5 cm | 2.01 (1.54) | 2.08 (1.61) |

| North Lake Creek | West River | |

|---|---|---|

| Total eggs laid (m2) | 501 (14–2189) | 353 (41–951) |

| Total fry emergence (m2) | 301 (7–2176) | 159 (0–795) |

| Detected egg mortality (%) | 50 (0.3–91) | 60 (9–100) |

| Detected alevin mortality (%) | 0 (0–0.3) | 2 (0–13) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Condon, J.D.; Roloson, S.D.; van den Heuvel, M.R. Emergence of Atlantic Salmon Fry in Relation to Redd Sediment Infiltration and Dissolved Oxygen in Small Coastal Streams. Fishes 2026, 11, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020082

Condon JD, Roloson SD, van den Heuvel MR. Emergence of Atlantic Salmon Fry in Relation to Redd Sediment Infiltration and Dissolved Oxygen in Small Coastal Streams. Fishes. 2026; 11(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020082

Chicago/Turabian StyleCondon, Jordan D., Scott D. Roloson, and Michael R. van den Heuvel. 2026. "Emergence of Atlantic Salmon Fry in Relation to Redd Sediment Infiltration and Dissolved Oxygen in Small Coastal Streams" Fishes 11, no. 2: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020082

APA StyleCondon, J. D., Roloson, S. D., & van den Heuvel, M. R. (2026). Emergence of Atlantic Salmon Fry in Relation to Redd Sediment Infiltration and Dissolved Oxygen in Small Coastal Streams. Fishes, 11(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020082