Abstract

The transplanting of juvenile and adult mussels onto soft sediments is an emerging technique for the ecological restoration of the biogenic habitat formed by mussels. While these habitats are often found within estuarine systems, the spatial suitability of these environments for restoration is poorly described. The dynamic and variable environmental conditions characteristic of estuaries could represent challenges to the persistence of restored mussel beds. To assess whether there are spatial differences in mussel responses to transplantation within an estuarine environment, six experimental mussel beds of adult green-lipped mussels (Perna canaliculus) were established along an environmental gradient in a small estuarine harbour in northern New Zealand. Transplanted mussel beds were sampled immediately after installation and again at 3 and 9 months later. Minor differences in the density, length and condition index of mussels were identified among the six sites over the course of the study; however, their responses were typically similar across sites. These results suggest that these mussels have the capacity to establish themselves within estuarine environments and that their subsequent performance once transplanted onto the seafloor appears to be determined by other site-specific factors, such as the presence of predators and the degree of exposure to storm waves.

Key Contribution:

Adult green-lipped mussels can be successfully restored to the seafloor within a wide range of estuarine environments; however, their subsequent persistence is highly site specific and does not relate to differences in substrate sediment.

1. Introduction

Selecting appropriate sites for restoration of marine biogenic habitat is critical to the success of such initiatives. Indeed, one of the leading causes of low survivorship and failure of restoration initiatives in coral reefs, seagrass, mangroves, and oyster restoration is the use of unsuitable sites from the outset [1]. These mechanisms of failure are typically species-specific and include factors such as high sedimentation, excessive wave energy, inappropriate substrate, and high sedimentation (see [1] for a more comprehensive list of reported causes of restoration failures). Site selection for restoration should incorporate, where possible, the historic distribution of the habitat and the environmental conditions that are conducive to the survival of the targeted species, as well as the logistical feasibility of employing restoration procedures [2]. By incorporating these criteria, in particular habitat suitability, restoration initiatives are more likely to select sites where either transplanted adults and juveniles or natural recruits arriving onto enhanced settlement substrate are most likely to survive and thus lead to greater success among initiatives [3,4,5].

Restoration of marine mussels typically involves the transplanting of juvenile or adult mussels directly to the soft-sediment seafloor. Despite only a relatively small number of initiatives around the world, this practice has been used for aquaculture purposes in the Dutch Wadden Sea and other parts of Europe for over half a century [6,7]. With increasing interest in the ecological restoration of mussels globally, the body of research contributing to this field has similarly grown in the past decade. Much of this research has focused on methods of deployment to enhance persistence of transplanted mussels, examining such factors as provision of attachment substrate [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], spatial configuration of transplants [16,17], integration of artificial fences to reduce hydrodynamically induced dislodgement [18,19], deployment of different life stages and different mussel stocks [20,21], and the timing of deployments [22]. However, there are fewer initiatives examining the suitability of current environmental conditions across potential study sites that might help inform the selection of sites that are most likely to maximise the persistence of mussels and therefore increase the chances of successfully restoring mussel populations. A few available examples include examination of the effects of hydrodynamic forcing and ice scouring [23,24] and hydrodynamic forcing and tidal emergence [25,26].

A single study used small deployments of mussels to the seafloor to assess site suitability for further restoration, but only across a narrow range of coastal conditions and not including estuarine environmental conditions [27]. This study was part of more extensive efforts to restore degraded beds of the endemic kūtai, or green-lipped mussels (Perna canaliculus), in New Zealand by transplanting cultured adult mussels directly to the soft-sediment sea floor to establish mussel beds [26,27,28,29]. One of the largest of these efforts involved the deployment of 77 t of adult mussels, sourced from aquaculture and deployed in 2013 and 2014 to a single embayment of Rotoroa Island in the Hauraki Gulf (within an approximate total area of 10 ha) [11,28]. Of the numerous beds deployed at this time, many persisted for over 8 years (Shaun Lee, Revive Our Gulf Trust, Auckland, New Zealand, pers. comm.); however, there were clear spatial differences observed in the persistence of mussels amongst the individually deployed mussel beds. While both a lack of recruitment [29,30] and predation [31] are considered to have contributed to the decline of these transplanted populations within the site, their relative contribution to the spatial differences in the decline is unknown. Complete and partial burial of mussels with sediment, as evidenced by video transect surveys [32], appears to be one of the drivers of the spatial differences in persistence. Factors such as sedimentation rate, bedload transport rate, and subsidence of mussels into the sediment may therefore be important considerations when selecting sites. Indeed, the seafloor across the deployment area within the embayment at Rotoroa Island consisted of varied soft-sediment substrates [33]. Therefore, it is possible that substrate characteristics, such as sediment grain size, will influence the performance of mussels once they are deployed to restoration sites; however, it remains untested. Such gaps in our understanding of the suitable environmental conditions within which to re-establish mussel populations need to be resolved to ensure the persistence of mussels restored to the seafloor.

Estuaries are highly productive environments, within which bivalve reefs are frequently an important biogenic feature. Many of the remnant populations of green-lipped mussels within New Zealand can be found in such environments (e.g., Weiti River, Ōhiwa Harbour), while historic information on green-lipped mussel distribution indicates it extended to many estuarine habitats [34,35,36,37]. The varied nature of estuarine environments potentially represents a number of challenges to site selection for mussel restoration, with environmental conditions varying both laterally and especially longitudinally along the watercourse and into the ocean, most often presenting as clear longitudinal environmental gradients [38]. For example, there is a strong and well-described association between the composition of benthic marine soft-sediment animal communities and gradation in the particle composition of the sediment they inhabit [38,39,40]. The impact of these environmental factors, especially salinity, suspended sediment, temperature, and tidal currents, on the persistence of mussels transplanted into estuaries is not well understood. Prior research would suggest green-lipped mussels are physiologically and behaviourally tolerant of a relatively wide range of salinity [41,42], temperature [41,43], benthic substrate [27,41], water quality, including suspended sediment [44,45]. Despite the historic and current distribution of remnant green-lipped mussels within estuaries, extensive land development combined with poor catchment management has also resulted in extensive deposition of fine sediment to benthic environments throughout New Zealand [46,47,48,49,50], and thus contemporary estuaries may not all represent similar quality habitat for mussels as they may have historically. While a good number of studies have documented the results of restoring green-lipped mussels in coastal locations [11,14,20,21,22,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], only a very small subset of these studies have focused on estuarine conditions, and where they have, they have typically followed the fate of a single set of restored mussels [20,21,22,33,35,36]. Therefore, to better inform restoration site selection and improve restoration success, greater information on spatial differences in the persistence of transplanted mussels along the environmental gradients present in estuaries is needed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine if there were any differential responses of green-lipped mussels to transplantation into sites along an estuarine environmental gradient within a coastal estuary in the outer Hauraki Gulf that might inform site selection for future experiments into restoration practices and restoration efforts in other estuarine habitats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

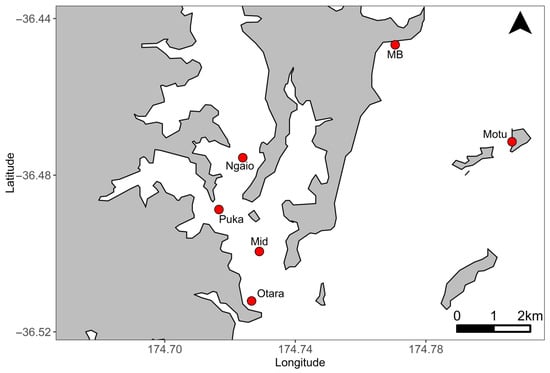

To examine potential spatial differences in restoration success within estuarine ecosystem, six sites were established along an estuarine environmental gradient from the inner Mahurangi Harbour in the Hauraki Gulf to the outer channel (Figure 1). The Mahurangi Harbour is a small estuary (25 km2), consisting of a drowned river valley system that is relatively sheltered from ocean swells due to the orientation of the harbour entrance, with additional protection provided by coastal islands at the entrance to the harbour [46,47,50,51,52,53,54,55]. The estuary is one of the most studied estuarine ecosystems in New Zealand with clear estuarine environmental gradients in shelter, sedimentation and salinity from its source in the Mahurangi River to its entrance out into the Hauraki Gulf [46,47,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Four of the study sites were located within the harbour, with those sites increasingly closer to the harbour entrance decreasing in benthic fine sediment and turbidity [46,47,50,53,54,55]. The remaining two sites were established on the coastline beyond the harbour entrance and continued the trend of decreasing benthic fine sediment in the series of sites running up the harbour. The sea floor topography at each site consisted of a flat or gently sloping substrate at depths of 5 m below mean low water (tidal fluctuations of approximately 2 m) and within 200 m of the low tide mark of the adjacent shoreline. While depth was relatively constant among sites, variability in environmental conditions within this span of the estuary has been documented historically for salinity (31–35 ppt), peak surface water velocity (during ebb tides of 0.15 to 0.5 m s−1), and turbidity (approximately 0 to 6 NTU with greater turbidity within the estuary) [50,53,54].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area in the Mahurangi Harbour, in the outer Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand, indicating the positions of each of the six study sites running along a gradient of increasing sediment grain size seaward. Ngaio = Ngaio Bay, Puka = Pukapuka, Mid = mid-Mahurangi, Otara = Otarawao Bay, MB = Martins Bay, Motu = Motuketekete.

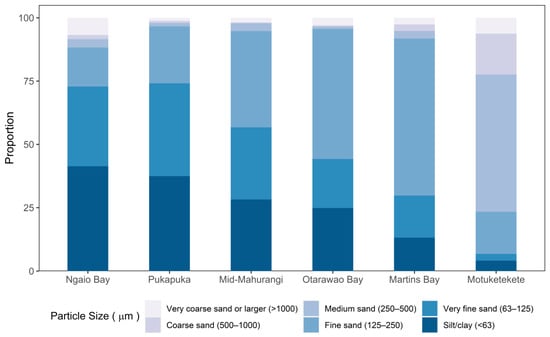

These gradations in sedimentary conditions were confirmed by sediment grain size analyses from each of the six study sites, as determined by core samples taken to a depth of 50 mm during the initial survey. Three haphazardly placed core samples were collected within 2 m of the bed centre and later pooled to provide a representative sample of the benthic sediment. In the laboratory, the samples were homogenised using a stirrer (IKA-Werke GmbH & Co, Staufen, Germany) and then a 100 mL sub-sample treated with 50 mL of 6% H2O2 solution to digest organic matter for 48 h. Following the addition of 50 mL of 5% Calgon solution (dispersant), samples were sieved (1 mm, 500 μm, 250 μm, 125 μm, and 63 μm, and a catch basin for <63 μm), and each fraction dried at 60 °C, and weighed (±0.001 g). The outer harbour sites were characterised by predominantly fine (125 to 250 μm) to medium (250 to 500 μm) sand while the inner sites characterised by a greater proportion of very fine (63–125 μm) sand (Figure 2). The substrate at the mid-Mahurangi exhibited an intermediate composition of predominantly very fine- and fine-grained sand. The differences in the distribution of the grain size of benthic sediments among the six sites reflected the environmental gradient of increasing fine sediment and turbidity up the harbour toward the riverine source of sediment.

Figure 2.

Sediment grain size distribution for the six study sites running along a gradient of increasing sediment grain size in the Mahurangi Harbour. Samples were collected upon the initial sampling date following deployment of the mussel beds.

2.2. Bed Deployments

Adult mussels of 70–100 mm in shell length (SL) were sourced from a single suspended mussel aquaculture operation in the Firth of Thames, in the Hauraki Gulf, where they were double-washed and transported to the Mahurangi Harbour in bulk handling bags that hold 800–1000 kg of live mussels. Each bag was filled to the same level to ensure that the same quantity of mussels was deployed to each experimental site. Mussels in the bags were then transported by barge on 28 October 2016 to each of the study sites, where the mussels were released from a single bag overboard to produce a single concentrated patch (approximately 25 m2) consisting of approximately 800–1000 kg of adult mussels at each site. It is difficult to tightly control the density of the resulting patch of mussels on the seafloor using this deployment method; however, there are no easy alternatives to this method, as moving this large quantity of live mussels by a diver would have been logistically difficult.

2.3. Sampling Design

Each site was sampled by SCUBA divers two weeks (22–23 November 2016; hereafter referred to as initial), 3 months (23 February–1 March 2017), and 9 months after deployment (24 August–4 September 2017). Qualitative observations on bed area, presence of predators, and burial of mussels (greater than 10% of valve surface area below the sediment–water interface) were made at each sampling period. Ten quadrats (0.25 m2) were deployed haphazardly at each site by a diver dropping the quadrats from a height of 5 m onto the mussel bed and ensuring they were greater than 10 cm apart, whereupon all mussels within each quadrat were counted to estimate density without disturbing the mussels. Mussel SL was measured (±1 mm) from mussels collected using an additional five quadrats (0.125 m2) placed haphazardly across the bed to ensure a broad selection of mussels from across the bed and to disperse the disturbance of the mussel bed from the removal of mussels to facilitate their measurement. From those collected mussels, a random subsample (RANDBETWEEN function in MSXcel) of 20 mussels from each site was selected to determine mussel condition. In the laboratory, the sampled mussels were cleaned of biofouling, rinsed with seawater, and then frozen at −70 °C until they could be processed. Dry weight condition index (CI), which avoids variation associated with wet weight measures due to fluctuating moisture content, was measured as the ratio of dried flesh weight to dry shell weight [56,57]. The SL of each mussel was measured, the flesh separated from the shell, and dried at 60 °C for 48 h, at which time they no longer showed a change in weight with further drying time.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were confirmed by visual inspection of quantile-quantile plots and plots of residual versus fitted values (respectively) for all models prior to running analyses. Visual inspection of these plots is a preferred method for assessment when dealing with a larger sample size [58]. Mussel density, SL, and CI of transplanted mussels were fitted to linear models (stats package in R version 2025.05.1+513) and tested for differences using two-way ANOVA with site and sampling date as fixed effects and their interaction. Due to the uneven sampling of sites between 3 and 9 months sampling as a result of lost beds, two sets of linear models were tested for each response variable using all sites for comparisons of initial and 3 month data, and a second set of models to assess differences at 9 months using only those sites for which data were available. These second analyses, while limited to a smaller sample size and restricted geographic coverage, provide some indication of whether patterns in mussel response persisted among those remaining sites. Any differences for significant factors were further examined using post hoc pairwise t-tests (predictmeans function of predictmeans package in R) and adjusted using false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

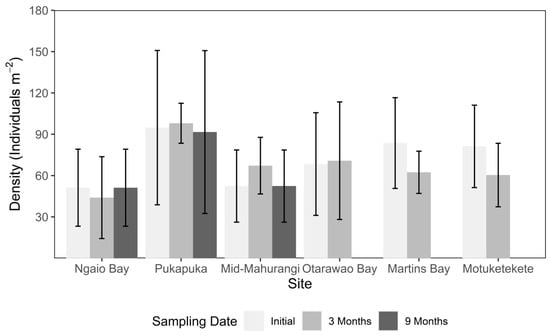

The mean density of mussels varied significantly by site when comparing up to the 3 month sampling (F = 5.21, df = 5, p < 0.001, Table 1, Figure 3), with pairwise comparisons revealing Pukapuka to have significantly greater density than all other sites, and Ngaio Bay to have significantly lower density than Motuketekete and Martins Bay North. There were no significant effects of either date of sampling (F = 0.69, df = 1, p = 0.409, Table 1) or the interaction term (F = 1.02, df = 5, p = 0.407, Table 1). The same pattern of difference was observed when comparing density up to the 9 month sampling date for three of the sites (mid-Mahurangi, Ngaio, Pukapuka, Table 2, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Results of two-way ANOVA comparisons for the measured variables from the six study locations in the Mahurangi Harbour, where mussels were deployed to the seafloor: substrate penetration depth, mussel density, mussel condition index, and mussel SL. Significance was determined at an α of 0.05.

Figure 3.

Mean density (±S.D.) of mussels for the six study sites running along a gradient of increasing sediment grain size in the Mahurangi Harbour at deployment (initial) and at 3 and 9 months post-deployment.

Table 2.

Results of two-way ANOVA comparisons for the measured variables from the available data from sampling at 9 months from the study locations in the Mahurangi Harbour, where mussels were deployed to the seafloor: mussel density, mussel condition index, and mussel SL. Significance was determined at an α of 0.05.

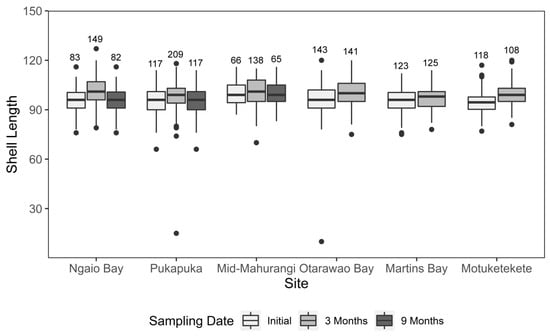

There was a significant interaction between site and sampling date when comparing mussel SL up to the 3 month sampling (F = 2.32, df = 5, p = 0.041, Table 1, Figure 4). Pairwise comparisons revealed that initially there were no significant differences in SL between sites except at mid-Mahurangi, where the mean SL was 3.14 mm larger than any other site (Figure 3). Comparisons of mean SL at 3 months indicated no significant changes in SL for mid-Mahurangi and Martins Bay compared to their initial size, while all other sites exhibited significant increases in SL of 2.95–5.28 mm over that sampling date. The analysis using only those sites that could be sampled at 9 months (mid-Mahurangi, Ngaio, Pukapuka) exhibited no interaction between experimental factors (F = 1.74, df = 4, p = 0.140, Table 2) and significant effects of both site and sampling date (F = 15.31, df = 2, p < 0.001 and F = 21.36, df = 2, p < 0.001, Table 2). Pairwise comparisons revealed that for those three sites, while the mean SL of mussels varied at 3 months from the initial size, there were no significant differences in SL between 9 months and the initial sampling (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Median shell length of mussels for the six study sites running along a gradient of increasing sediment grain size in the Mahurangi Harbour at deployment (initial) and at 3 and 9 months post-deployment. Boxes depict the upper and lower quartiles, while whiskers represent the spread of the data. Points represent outliers, identified as values outside 1.5 times the interquartile range.

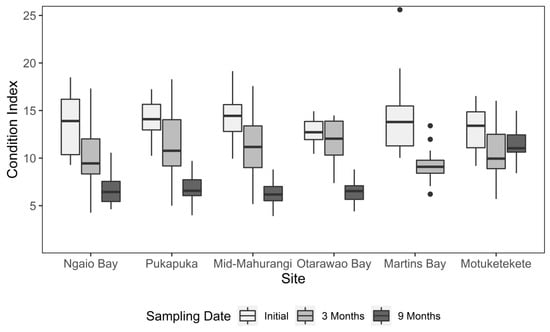

For both analyses of mussel CI (comparing up to 3 months and up to 9 months separately, Table 1 and Table 2, respectively, Figure 5), there were significant interactions between site and sampling date (F = 2.25, df = 5, p = 0.049 and F = 7.88, df = 8, p < 0.001, respectively). Pairwise comparisons revealed that initially, the mean CI of mussels exhibited no difference between sites (Figure 5). After 3 months, the mean condition of mussels decreased significantly across all sites except for Otarawao Bay, which exhibited no difference from the initial condition. At 9 months, the sampled sites all showed further significant declines in condition, with the exception of mussels at the Motuketekete site, which exhibited no significant differences in CI compared to either the initial or 3 month sampling dates.

Figure 5.

Median condition index of mussels for the six study sites running along a gradient of increasing sediment grain size in the Mahurangi Harbour at deployment (initial) and at 3 and 9 months post-deployment. Boxes depict the upper and lower quartiles, while whiskers represent the spread of the data. Points represent outliers, identified as values outside 1.5 times the interquartile range.

4. Discussion

The persistence of the experimental mussel beds was broadly consistent among five of the experimental sites for up to 9 months, indicating that mussels are capable of surviving within the range of environmental conditions experienced along the upper to lower estuary. The sixth restored mussel bed was located at one of the more exposed outer coastal sites (Martins Bay) and was dispersed by waves during a significant easterly storm event after the second sampling date. Although not directly quantified in this study, extensive previous studies have shown a marked change in environmental conditions along a gradient from the inner Mahurangi, through the Harbour, to the outer sites, including such variables as suspended sediments, turbidity, salinity, and flow velocity [46,47,50,51,52,53,54,55] which typically characterise environmental gradients present in shallow coastal estuarine ecosystems and play a major role in determining the distribution of other benthic fauna [38,39,40]. Despite these pronounced environmental estuarine gradients present among the study sites, including a very marked gradation in the grain size of the substrate, there was no clear gradation in the response of mussels for all three metrics assessed (SL, CI, density) among the study sites, indicating mussels responded in a similar manner for these sites. Hence, it appears that the environmental gradients present in this estuarine environment, including the differences in substrate, did not strongly influence the performance of the mussels following their deployment to the seafloor.

Mussel density showed some difference by site initially, most likely due to a combination of differences in the density of the deployed mussels at each site due to variation in the amounts of individual mussels distributed beyond the desired deployment site as a result of the surface deployment from a vessel, coupled with variation in water currents. However, mussel density for individual sites did not differ among any sampling dates, which, combined with qualitative observations of reducing bed area across successive sampling, suggests that mortality or disturbance was likely to be greatest at the margins of the mussel bed rather than uniform throughout the bed. These observations are, however, in contrast with a previous subtidal study, which found bed area to be relatively similar across sampling dates while mussel density declined over time [28]. This difference between the present study and this previous study [28] may be due to greater hydrodynamic forces from estuarine tidal flux, similar to that observed for intertidal beds by de Paoli et al. [9] or may be due to a different suite of predators in the Mahurangi Harbour location that may preferentially select mussels at the margin of the restored mussel beds [20,21,22] compared to those at Rotoroa Island in Wilcox et al. [28].

Measures of SL indicated growth of mussels at some sites after 3 months; however, by 9 months, the average size of mussels showed no statistical differences from the initial average. While the cause is not known, this pattern of differences in mussel SL among sampling dates could be due to size-dependent predation pressures or some process that leads to reduced survival after transplant for larger-sized mussels, which warrants further investigation.

Unlike growth and density measures, the mussel condition index exhibited clear differences between sites and sampling dates. Most notable was the Motuketekete site, where the condition index after 9 months was similar to initial levels, while all other sites had declined significantly from the initial condition. Environmental conditions, such as food supply, water flow, temperature, and salinity, which are known to impact the condition index of bivalves [56,57,59,60], may have been more favourable to somatic growth and gonad development than sites within the estuary. It might also be due to inter-site differences in the onset of seasonal gonad development. The marked and consistent decline in condition index across the remaining sites could also be due to localised differences in environmental conditions between the restoration site and the suspended aquaculture conditions from where they were sourced. Mussels grown in suspended cultures are known to have higher condition than those grown on the seafloor [61,62], which is likely due to improved food supply in the water column compared to mussels at the seafloor, for which food availability is more likely to be constrained by the benthic boundary layer. It is also possible that mussels at those sites within the harbour spend less time feeding and/or expend more energy as a result of processing higher loads of suspended sediment. Green-lipped mussels are known to maintain energetically expensive and high filtering rates even when suspended sediment concentrations are high in an apparent effort to maintain food intake [44,63,64]. High suspended sediment has also been found to result in damage to the gill microstructure used for feeding in the green mussel, Perna viridis [65], while valve closure and mucous production required to package and reject unwanted suspended sediment particles as pseudofaeces have been found to incur significant energetic costs in other bivalve species [66,67]. The blue mussel, Mytilus edulis, does exhibit high levels of plasticity in gill structure following transplantation, which can overcome higher levels of seston [68]; however, it is unknown whether the green-lipped mussel exhibits similar levels of adaptability following transplantation. Previous research indicates that green-lipped mussels are similar to some other bivalve species in having a capacity to ingest and utilise the nutrients from the organic material associated with suspended sediment, and in this way may increase their overall tolerance of high suspended sediment conditions [44,45,69,70].

Although sea stars were observed by divers to be present at all sites prior to deployment (during site selection surveys; personal observation of Peter Van Kampen) and across all mussel beds by the 3 month sampling period, mussels placed at two of the six sites, Martins Bay and Otarawao Bay, were observed to attract considerably higher densities of eleven-armed sea stars, Coscinasterias muricata; the predatory activities of which subsequently diminished the mussel populations greatly. At 9 months, sea stars continued to be prevalent in all mussel beds, and the Otarawao Bay site had been greatly reduced in extent, most likely due to intense predation by the sea stars. The reasons for the appearance of these predatory sea stars at some sites and not others are uncertain, as similar discontinuities in spatial and temporal abundance of this sea star species have been identified at a number of shallow coastal locations in New Zealand and are possibly due to fluctuations in natural recruitment of this species [27,71,72]. Similar impacts from this species of predatory sea star on mussel populations in New Zealand have been recorded previously [27,31,35,71,72], and more widely, sea star predation is recognised as important in modulating the abundance of prey species in benthic communities [73,74,75]. Previously, the predatory activities of eleven-armed sea stars were estimated to have contributed 40% to the observed mortality across 4 t of green-lipped mussels restored into a shallow coastal bay at Rotoroa Island, in the Hauraki Gulf [31] and impacted the viability of small experimental plots of mussels in the Marlborough Sounds in southern New Zealand [14,27]. Although this sea star is associated with natural mussel beds [71,72], reducing its impact on restored mussel beds could increase the chances of successful restoration. This could involve selecting sites with lower abundances of sea stars or potentially timing deployments to periods when sea star abundance may be lower, as has been reported for predation on restored mussels by fish species during colder months [22].

A second limitation to the persistence of restored mussels was the destruction of mussel aggregations and widespread dispersal and burial of mussels at the Martins Bay site by wave energy during a storm event. The wave height and direction observed during this storm were sufficient to cause sufficient benthic hydrodynamic forces to dislodge and disperse mussels at this relatively shallow depth [76,77]. A similar loss of mussel beds due to wave energy during a storm event was previously reported for mussels deployed at Rotoroa Island [31]. While hydrodynamic forces can aid in the dispersal and establishment of new mussel beds when clumps become dislodged [78], those dispersed individuals no longer receive benefits such as the reduced predation rate observed for mussels within dense aggregations [79,80] and are therefore likely at a greater chance of mortality through predation. The issue of physical displacement when establishing mussel beds is common, given that natural sites being restored are often highly dynamic areas for water flow. For example, the establishment of blue mussels on restoration plots in the intertidal zone was impeded after they were flushed away by successive tidal flow and wave action, regardless of available attachment substrate [8]. Similarly, the installation of a low-relief structure that reduces hydrologically induced dislodgement of mussels has been shown to improve young mussel retention after transplantation [18,19].

The results of the present study demonstrate that green-lipped mussels can persist if transplanted within an estuarine environment with a wide range of benthic sediment substrates in the Hauraki Gulf. However, further research is required to confirm the environmental conditions that are most suitable for the survival and reproduction of mussels, characteristics that are critical to the long-term success of mussel restoration. This includes improving our understanding of sea star predatory interactions, particularly which factors may influence attraction, and considering exposure to physical forcing to minimise the chances of dispersal of experimental beds. With a greater understanding of the individual conditions that contribute positively to the suitability of habitat for restoration, practitioners will be better informed when selecting potential donor habitats for mussel restoration and thus improve the success of restoration initiatives.

5. Conclusions

Prior assessment of site suitability for the deployment of adult mussels to soft sediment substrates in shallow coastal waters should consider localised predator pressure and risk of benthic disturbance from wave energy during storm events. In contrast, the benthic sediment composition, including elevated levels of fine sediment, does not appear to be a primary determinant of site suitability for restoration for this mussel species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.v.K., A.J. and S.K.; methodology, P.v.K., A.J. and S.K.; formal analysis P.v.K., A.J., S.K. and M.W.; investigation, P.v.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W., P.v.K. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, M.W., P.v.K. and A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge the Mussel Reef Restoration Trust for their funding support. The Nature Conservancy was instrumental in providing funding support for the deployment of the mussels. North Island Mussels Ltd. and Biomarine Ltd. provided mussels and logistical support for the mussel deployments. Thank you also to the Māori Vice-Chancellor’s office at The University of Auckland, in particular Jim Peters, who facilitated resources to support this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Under New Zealand’s Animal Welfare Act 1999, mussels, as used in this study, are not considered to be sentient animals and are therefore exempt from the animals in research provisions of this legislation. Therefore, there was no need to seek specific animal welfare approvals for this work.

Data Availability Statement

Research data from this study are available upon request from the contributing author.

Acknowledgments

“Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini”—translates as “Success is not the work of an individual, but the work of many.” The authors would like to (mihi) acknowledge Ngāti Manuhiri and Ngāi Tai ki Tamaki as mana whenua for their respective rohe (areas) that this study was conducted at within Tikapa Moana, Te Moananui o Toi. We would like to thank Peter Browne, Errol Murray, Brady Doak, Lucy van Oosterom, Peter Schlegal, Boyd Taylor, and the many students who helped with field work and logistics of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shane Kelly was employed by the company Coast and Catchment. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from North Island Mussels Ltd. and Biomarine Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Bayraktorov, E.; Saunders, M.I.; Abdullah, S.; Mills, M.; Beher, J.; Possingham, H.P.; Mumby, P.J.; Lovelock, C.E. The cost and feasibility of marine coastal restoration. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 1055–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoda, B.; Merk, V.; Colsoul, B.; Hausen, T.; Peter, C.; Pesch, R.; Kramer, M.; Jaklin, S.; Holler, P.; Bartholomä, A.; et al. Site selection for biogenic reef restoration in offshore environments: The Natura 2000 area Borkum Reef Ground as a case study for native oyster restoration. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2020, 30, 2163–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotaling-Hagan, A.; Swett, R.; Ellis, L.R.; Frazer, T.K. A spatial model to improve site selection for seagrass restoration in shallow boating environments. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 186, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schill, S.R.; Asner, G.P.; McNulty, V.P.; Pollock, F.J.; Croquer, A.; Vaughn, N.R.; Escovar-Fadul, X.; Raber, G.; Shaver, E. Site selection for coral reef restoration using airborne imaging spectroscopy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 698004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumbaugh, R.D.; Coen, L.D. Contemporary approaches for small-scale oyster reef restoration to address substrate versus recruitment limitation: A review and comments relevant for the Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida Carpenter 1864. J. Shellfish Res. 2009, 28, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankers, N.; Zuidema, D.R. The role of the mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) and mussel culture in the Dutch Wadden Sea. Estuaries 1995, 18, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J.; Smaal, A.; van der Reijden, K.; Nehls, G. Fisheries. In Wadden Sea Quality Status Report; Kloepper, S., Meise, K., Eds.; Common Wadden Sea Secretariat: Wilhelmshaven, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fariñas-Franco, J.M.; Allcock, L.; Smyth, D.; Roberts, D. Community convergence and recruitment of keystone species as performance indicators of artificial reefs. J. Sea Res. 2013, 78, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paoli, H.; van de Koppel, J.; van der Zee, E.; Kangeri, A.; van Belzen, J.; Holthuijsen, S.; van den Berg, A.; Herman, P.; Olff, H.; van der Heide, T. Processes limiting mussel bed restoration in the Wadden-Sea. J. Sea Res. 2015, 103, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, C.; Montgomery, W.I.; O’Connor, N.E. Habitat with small inter-structural spaces promotes mussel survival and reef generation. Mar. Biol. 2018, 165, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.; Jeffs, A. Is attachment substrate a prerequisite for mussels to establish on soft-sediment substrate? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2017, 495, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle, J.J.; Leuchter, L.; de Wit, M.; Hartog, E.; Bouma, T.J. Creating a window of opportunity for establishing ecosystem engineers by adding substratum: A case study on mussels. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, K.; Christie, H.; Didderen, K.; Fagerli, C.W.; Govers, L.L.; Gräfnings, M.L.E.; Heusinkveld, J.H.T.; Kaljurand, K.; Legnkeek, W.; Martin, G.; et al. Incorporating facilitative interactions into small-scale eelgrass restoration—Challenges and opportunities. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.D.; Hillman, J.R.; Handley, S.J.; Toone, T.A.; Jeffs, A. The effectiveness of providing shell substrate for the restoration of adult mussel reefs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bogaart, L.A.; Schotanus, J.; Capelle, J.J.; Bouma, T.J. Using a biodegradable substrate to increase transplantation success: Effect of density and sediment on aggregation behaviour of mussels. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 196, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle, J.J.; Wijsman, J.W.M.; Schellekens, T.; van Stralen, M.R.; Herman, P.M.J.; Smaal, A.C. Spatial organisation and biomass development after relaying of mussel seed. J. Sea Res. 2014, 85, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, C.; Geraldi, N.R.; Montgomery, W.I.; O’Connor, N.E. Substratum type and conspecific density as drivers of mussel patch formation. J. Sea Res. 2017, 121, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotanus, J.; Walles, B.; Capelle, J.J.; van Belzen, J.; van de Koppel, J.; Bouma, T.J. Promoting self-facilitating feedback processes in coastal ecosystem engineers to increase restoration success: Testing engineering measures. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotanus, J.; Capelle, J.J.; Paree, E.; Favish, G.S.; van de Koppel, J.; Bouma, T.J. Restoring mussel beds in highly dynamic environments by lowering environmental stressors. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, A.; Jeffs, A.; Hillman, J.R. Considering the use of subadult and juvenile mussels for mussel reef restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 29, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, A.; Jeffs, A.; Hillman, J.R. The importance of stock selection for improving transplantation efficiency. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 30, e13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, A.; Jeffs, A.; Hillman, J.R. Timing mussel deployments to improve reintroduction success and restoration efficiency. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2022, 698, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, J.J.A.; van der Vegt, M.; Hoekstra, P. Wave forcing over an intertidal mussel bed. J. Sea Res. 2013, 82, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, J.J.A.; van der Vegt, M.; Hoekstra, P. Erosion of an intertidal mussel by ice- and wave-action. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 106, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotanus, J.; Capelle, J.J.; Leuchter, L.; van de Koppel, J.; Bouma, T.J. Mussel seed is highly plastic to settling conditions: The influence of waves versus tidal emergence. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 624, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.D.; Toone, T.A.; Hillman, J.R.; Handley, S.J.; Jeffs, A. Aerial exposure and critical temperatures limit the survival of restored intertidal mussels. Restor. Ecol. 2024, 32, e14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.D.; Handley, S.J.; Jeffs, A.; Olsen, L.; Toone, T.A.; Hillman, J.R. Testing habitat suitability for shellfish restoration with small-scale pilot experiments. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2023, 5, e12878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.; Kelly, S.; Jeffs, A. Ecological restoration of mussel beds onto soft-sediment using transplanted adults. Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim-Smith, C.; Kelly, S. Rotoroa Mussel Bed Monitoring: January 2016a Progress. In Report for Revive Our Gulf; Coast and Catchment Ltd.: Auckland, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, M.; Kelly, S.; Jeffs, A. Patterns of settlement within a restored mussel bed site. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.; Jeffs, A. Impacts of sea star predation on mussel bed restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim-Smith, C.; Kelly, S. Rotoroa Mussel Bed Monitoring: November 2016b Progress. In Report for Revive Our Gulf; Coast and Catchment Ltd.: Auckland, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen, P.H.G. Characterising the Ideal Habitat for Subtidal Benthic Re-Seeding of the Green-Lipped Mussel Perna canaliculus. Master’s Thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, L.J. A history of the Firth of Thames dredge fishery for mussels: Use and abuse of a coastal resource. In New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 94; NIWA: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Burke, K.; Burke, J.; Bluett, C.; Senior, T. Using Māori knowledge to assist understandings and management of shellfish populations in Ōhiwa Harbour, Aotearoa New Zealand. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 52, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul-Burke, K.; Ngarimu-Cameron, R.; Burke, J.; Bulmer, R.; Cameron, K.; O’Brien, T.; Bluett, C.; Ranapia, M. Taura kuku: Prioritising Māori knowledge and resources to create biodegradable mussel spat settlement lines for shellfish restoration in Ōhiwa Harbour. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2022, 56, 570–584. [Google Scholar]

- Toone, T.A.; Benjamin, E.D.; Hillman, J.R.; Handley, S.; Jeffs, A. Multidisciplinary baselines quantify a drastic decline of mussel reefs and reveal an absence of natural recovery. Ecosphere 2022, 14, e4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, A.J. Broad-scale environmental gradients among estuarine benthic macrofaunal assemblages of south-eastern Australia: Implications for monitoring estuaries. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2004, 55, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.S. Animal–sediment relationships. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 1974, 12, 223–261. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. Animal–sediment relationships re-visited: Characterising species’ distributions along an environmental gradient using canonical analysis and quantile regression splines. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008, 366, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffs, A.G.; Holland, R.C.; Hooker, S.H.; Hayden, B.J. Overview and bibliography of research on the greenshell mussel, Perna canaliculus, from New Zealand waters. J. Shellfish Res. 1999, 18, 347–360. [Google Scholar]

- Copedo, J.S.; Webb, S.C.; Ragg, N.L.C.; Alfaro, A.C. Implications of flooding events for the green-lipped mussels (Perna canaliculus): An aquatic health perspective. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2025, 59, 1640–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, J.A.; Venter, L.; Copedo, J.S.; Nguyen, V.T.; Alfaro, A.C.; Ragg, N.L.C. Chronic heat stress as a predisposing factor in summer mortality of mussels, Perna canaliculus. Aquaculture 2023, 564, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, S.; Hayden, B.J.; James, M.R. The effects of food concentration and quality on the feeding rates of three size classes of the Greenshell™ mussel, Perna canaliculus. Hydrobiologia 2005, 548, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggar, B.S.; Jeffs, A.G.; Hillman, J.R. Effects of suspended sediment on survival, growth, and nutritional condition of green-lipped mussel spat (Perna canaliculus, Gmelin, 1791). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2025, 582, 152074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, V.J.; Thrush, S.F.; Pridmore, R.D.; Hewitt, J.E. Mahurangi Harbour Soft-Sediment Communities: Predicting and Assessing the Effects of Harbour and Catchment Development; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research for Auckland Regional Council; Auckland Regional Council, Technical Report # TR2009/040; NIWA: Auckland, New Zealand, 1994.

- Gibbs, M. Sediment Source Mapping in Mahurangi Harbour; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research for Auckland Regional Council; Auckland Regional Council, Technical Report # TP321-2009/040; NIWA: Auckland, New Zealand, 2006.

- Handley, S.; Gibbs, M.; Swales, A.; Olsen, G.; Ovenden, R.; Bradley, A. A 1000 Year History of Seabed Change in Pelorus Sound/Te Hoiere; Nelson, New Zealand; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Client Report Prepared for Marlborough District Council, Report # 2016119NE; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research: Nelson, New Zealand, 2017.

- Hunt, S. Summary of Historic Estuarine Sedimentation Measurements in the Waikato Region and Formulation of a Historic Baseline Sedimentation Rate; Waikato Regional Council Technical Report # 2019/08; NIWA: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2019.

- Harris, T.F.W. Hauraki Gulf Tideways: Elements of Their Natural Sciences; Leigh Laboratory Bulletin No. 29; University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 1993; 107p. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.O.; Hewitt, J.E.; Thrush, S.F. Seabed drag coefficient over natural beds of horse mussels (Atrina zelandica). J. Mar. Res. 1998, 56, 613–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Juan, S.; Hewitt, J. Spatial and temporal variability in species richness in a temperate intertidal community. Ecography 2014, 37, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies-Colley, R.J.; Nagels, J.W. Optical Water Quality of the Mahurangi Estuarine System; Prepared NIWA for Auckland Regional Council; Auckland Regional Council Technical Report 2009/057; NIWA: Auckland, New Zealand, 1995.

- Oldman, J.W.; Black, K.P. Mahurangi Estuary Numerical Modelling; NIWA report prepared for Auckland Regional Council, technical report # ARC60208/1; NIWA: Auckland, New Zealand, 1997.

- Cummings, V.J.; Halliday, J.; Thrush, S.F.; Hancock, N.; Funnell, G.A. Mahurangi Estuary Ecological Monitoring Programme–Report on Data Collected from July 1994 to January 2005; NIWA Client Report for the Auckland Regional Council, HAM2005–057; NIWA: Auckland, New Zealand, 2005.

- Hickman, R.W.; Illingworth, J. Condition cycle of the green-lipped mussel Perna canaliculus in New Zealand. Mar. Biol. 1980, 60, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Beninger, P.G. The use of physiological condition indices in marine bivalve aquaculture. Aquaculture 1985, 44, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Keough, M.J. Experimental Design and Data Analysis for Biologists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, I.D.; Weatherhead, M.A. Shore-level induced variations in condition and feeding of the mussel Perna canaliculus from the east coast of the South Island, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1999, 33, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Cummings, V.; Hewitt, J.; Thrush, S.; Norkko, A. Determining effects of suspended sediment on condition of a suspension feeding bivalve (Atrina zelandica): Results of a survey, a laboratory experiment and a field transplant experiment. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2002, 267, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolley, S.G.; Volety, A.K.; Savarese, M. Influence of salinity on the habitat use of oyster reefs in three southwest Florida estuaries. J. Shellfish Res. 2005, 24, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, J.C.; Crowley, M. Condition and variability in Mytilus edulis (L.) from different habitats in Ireland. Aquaculture 1986, 52, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, I.M. Green-Lipped Mussels, Perna canaliculus, in Soft-Sediment Systems in Northeastern New Zealand. Master’s Thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teaioro, I. The Effects of Turbidity on Suspension Feeding Bivalves. Master’s Thesis, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Luesiri, M.; Boonsanit, P.; Lirdwitayaprasit, T.; Pairohakul, S. Filtration rates of the green-lipped mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) exposed to high concentration of suspended particles. Sci. Asia 2022, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, E.A.M.; Thomas, R.; Adams, C.E.; Stephen, A. Behavioural and metabolic responses of Unionida mussels to stress. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 3184–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumon, R.; Cataldo, D.; Boltovskoy, D. Effects of suspended inorganic matter on filtration and grazing rates of the invasive mussel Limnoperna fortunei (Bivalvia: Mytiloidea). J. Molluscan Stud. 2016, 82, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Capelle, J.J.; Hartog, E.; van den Bogaart, L.; Jansen, H.M.; Wijsman, J.W.M. Adaptation of gill-palp ratio by mussels after transplantation to culture plots with different seston conditions. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiørboe, T.; Møhlenberg, F.; Nøhr, O. Effect of suspended bottom material on growth and energetics in Mytilus edulis. Mar. Biol. 1981, 61, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilovic, A.; Jug-Dujakovic, J.; Bonacic, A.M.; Conides, A.; Bonacic, K.; Ljubicic, A.; Van Gorder, S. The influence of environmental parameters on the growth and meat quality of the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2011, 4, 573–583. [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Burke, K.; Burke, J. Monitoring Assessment of Kūtai (Perna canaliculus) Green-Lipped Mussel and Pātangaroa (Coscinasterias muricata) Seastar Populations in the Western Side of Ōhiwa Harbour 2013: Technical Report; Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Awa: Whakatāne, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Burke, K.; Ngarimu-Cameron, R.; Paul, W.; Burke, J.; Cameron, K.; O’Brien, T.; Bluett, C. Nga tohu o te taiao: Observing signs of the natural world to identify seastar over-abundance as a detriment to shellfish survival in Ohiwa Harbour, Aotearoa/New Zealand. N. Z. Sociol. 2022, 37, 186–210. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, R.T. Food web complexity and species diversity. Am. Nat. 1966, 100, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, R.T. Intertidal community structure. Experimental studies on the relationship between a dominant competitor and its principal predator. Oecologia 1974, 15, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, B.A.; Berlow, E.L.; Blanchette, C.A.; Navarrete, S.A.; Yamada, S.B. The keystone species concept: Variation in interaction strength in a rocky intertidal habitat. Ecol. Monogr. 1994, 64, 249–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Ridd, P.V.; Mayocchi, C.L.; Heron, M.L. Wave-induced benthic velocity variations in shallow waters. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1996, 42, 787–802. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, R.G. Intercomparison of near-bottom kinematics by several wave theories and field and laboratory data. Coast. Eng. 1986, 9, 399–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commito, J.A.; Dankers, N.M.J.A. Dynamics of spatial and temporal complexity in European and North American soft-bottom mussel beds. In Ecological Comparisons of Sedimentary Shores; Reise, K., Ed.; Ecological Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 151, pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Okamura, B. Group living and the effects of spatial position in aggregations of Mytilus edulis. Oecologia 1986, 69, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svane, I.; Ompi, M. Patch dynamics in beds of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis L.: Effects of site, patch size, and position within a patch. Ophelia 1993, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).