Abstract

Fish communities undergo climate-induced shifts; it is crucial to study the trophic interactions of various fish species in order to understand the extent to which fish trophic niches overlap and the degree of competition between them. We investigated the food web structure, feeding habits, and trophic positions of common fish in the subarctic Lake Imandra. Two methods were used: SCA (stomach content analysis) and SIA (stable isotope analysis). Perch (Perca fluviatilis) and whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus, large sparsely rakered morph) had similar trophic positions (TP = 3.69 ± 0.55 and 3.67 ± 0.55, respectively; p > 0.05); both species were generalists. The diet similarity (the index of relative importance of food items in stomach contents) of perch and whitefish was 48%, with aquatic insects (Trichoptera) being common items in both fish. According to carbon isotope values (δ13C), vendace (Coregonus albula), smelt (Osmerus eperlanus), and burbot (Lota lota) were more closely related with pelagic food sources (δ13C ranged from −27 to −25‰), whereas perch, whitefish, and ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernua) were more fuelled by benthic food web compartments (δ13C ranged from −24 to −21‰). The highest average nitrogen values (δ15N) were found in smelt and ruffe, 15.0 ± 0.7‰ and 14.2 ± 1.9‰, respectively. Perch and whitefish overlap significantly in their isotopic composition (δ13C and δ15N), demonstrating 36% overlap in the combined 40% ellipses (according to Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R) of the isotopic space. This study confirms the existence of distinct food competition between these two species in a subarctic lake.

Key Contribution:

Stomach content revealed high dietary similarity between whitefish and perch, while the stable isotope analyses found substantial overlap in their isotopic niches. The study confirms food competition between whitefish and perch in an Arctic lake.

1. Introduction

Global warming has a profound impact on freshwater ecosystems, leading to changes in fish distribution areas. Percidae and Salmonidae are the most common fish families in the northern region [1]. European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus), European vendace (C. albula), and other coregonids prefer cold-water lakes in northern regions. European perch (Perca fluviatilis) and ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernua) are more widespread and can be found in more temperate regions of Europe and Northern Asia [2]. Climate change impacts lakes in high latitudes by increasing water temperatures, increasing productivity, decreasing dissolved oxygen, and prolonging the warm season [3]. These changes favour temperate-adapted species over cold-water-adapted native fish species. Many studies predict that these climate changes lead to increased water temperatures beyond the optimal range for coregonids, resulting in a local decrease in their distribution range [4,5,6]. First of all, this phenomenon is due to the fact that cold-water stenotherms (coregonids) spawn in mid-to-late autumn, and the warming and shortening of the ice-covered period negatively affect the survival of their embryos and larvae [7]. In recent decades, the distribution of percid species such as P. fluviatilis and G. cernuus has expanded northward into the subarctic regions, with a potential range of about 70 degrees north latitude [8,9]. These percids were on the edge of their range in the northern areas last century, occurring in small numbers, but as the environment warmed, they spread to Arctic lakes. Climate warming has facilitated their increased population growth rates, earlier sexual maturity, higher survival rates for recruitment, and increased overall reproductive population potential [3]. Perch and ruffe are not alien species, although they might be categorised as local invaders, extending their native range due to favourable climatic conditions. In reality, a process of fish community reorganisation in subarctic lakes is going on, with Arctic species being replaced by species with a more boreal distribution in response to climatic warming, known as borealization [10].

The large-sized forms of European whitefish, C. lavaretus (hereafter whitefish), which feed on both pelagic and benthic prey, inhabit most of the Fennoscandian lakes [11,12]. In some large, deep lakes, whitefish demonstrate wide phenotypic polymorphism with pronounced trophic specialisation of morphs, inhabiting different lake zones and utilising various food resources [11,12,13]. Whitefish morphs differ in the number of gill rakers, which is commonly correlated to trophic ecology and habitat use in each of the sympatric whitefish morphs—pelagic morphs are typically fusiform with a higher number of gill rakers, whereas benthic morphs have a more robust body shape and a lower number of gill rakers [11,12]. Another coregonid fish, vendace (C. albula), and small-sized forms of whitefish are believed to feed as a rule on zooplankton; thus, they exhibit low food competition for food resources with benthivorous fish (P. fluviatilis and G. cernua).

Simultaneously, in high-latitude lakes characterised by low plankton production, benthic production serves as the principal energy source for the majority of fish species, including planktivorous vendace [14,15,16,17,18]. Perch, as an ecological generalist, has ontogenetic dietary shifts from zooplankton to benthic macroinvertebrates before finally becoming piscivorous [19,20]. Ruffe, on the other hand, is a benthic specialist whose diet consists primarily of chironomid larvae, with a preference for preying on fish eggs [21]. It may prey on whitefish eggs and vendace adults, reducing population abundances [22]. Furthermore, as an effective benthivore, ruffe can promote trophic shifts in other generalists like perch [23].

Whitefish and perch have been observed feeding on the same food sources in various North Karelia lakes [24]. Simultaneously, the adaptive possibility of successful coexistence between these populations remains questionable. It is uncertain whether these fish species live in separate trophic niches or compete for food. As a result, examining trophic linkages and relationships between coregonids and percids will aid in our understanding of the reasons for coregonid population decline. To assess the trophic relationships of fish living together in the lake, two methods were used in combination: SCA (stomach contents analysis) and SIA (stable isotope analysis). Both methods have advantages and disadvantages, but they complement each other when used together [25]. One advantage of SCA is that it provides information on the taxonomic identity of prey items, which is missing from SIA [26]. Analysis of stable isotopes (SIA) of carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) can reveal trophic niches of species and determine consumer-predator relationships [27]. SIA provides integrated data on primary carbon sources and food web position over longer time scales than stomach content analysis [28]. A methodological approach using stable isotopes was used before to determine the degree of omnivorousness in two coexisting predators [29].

A hypothesis has been proposed for the existence of interspecific food competition between coexisting percid and coregonid fish species in subarctic lakes. Using the example of the subarctic Lake Imandra, we aim to understand the extent to which percids’ and coregonids’ trophic niches overlap and the degree of competition between them. We studied and compared the food spectrum of perch and whitefish based on the analysis of stomach contents (SCA) and considered the structure of food webs by analysing stable isotopes (SIA) to trace the flow of energy from the producer (phytoplankton) to higher-order consumers (fish) and to detect trophic positions of different fish species and other consumers in the food web. Based on the obtained results, isotopic niche width and overlap among fish species will be quantified.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

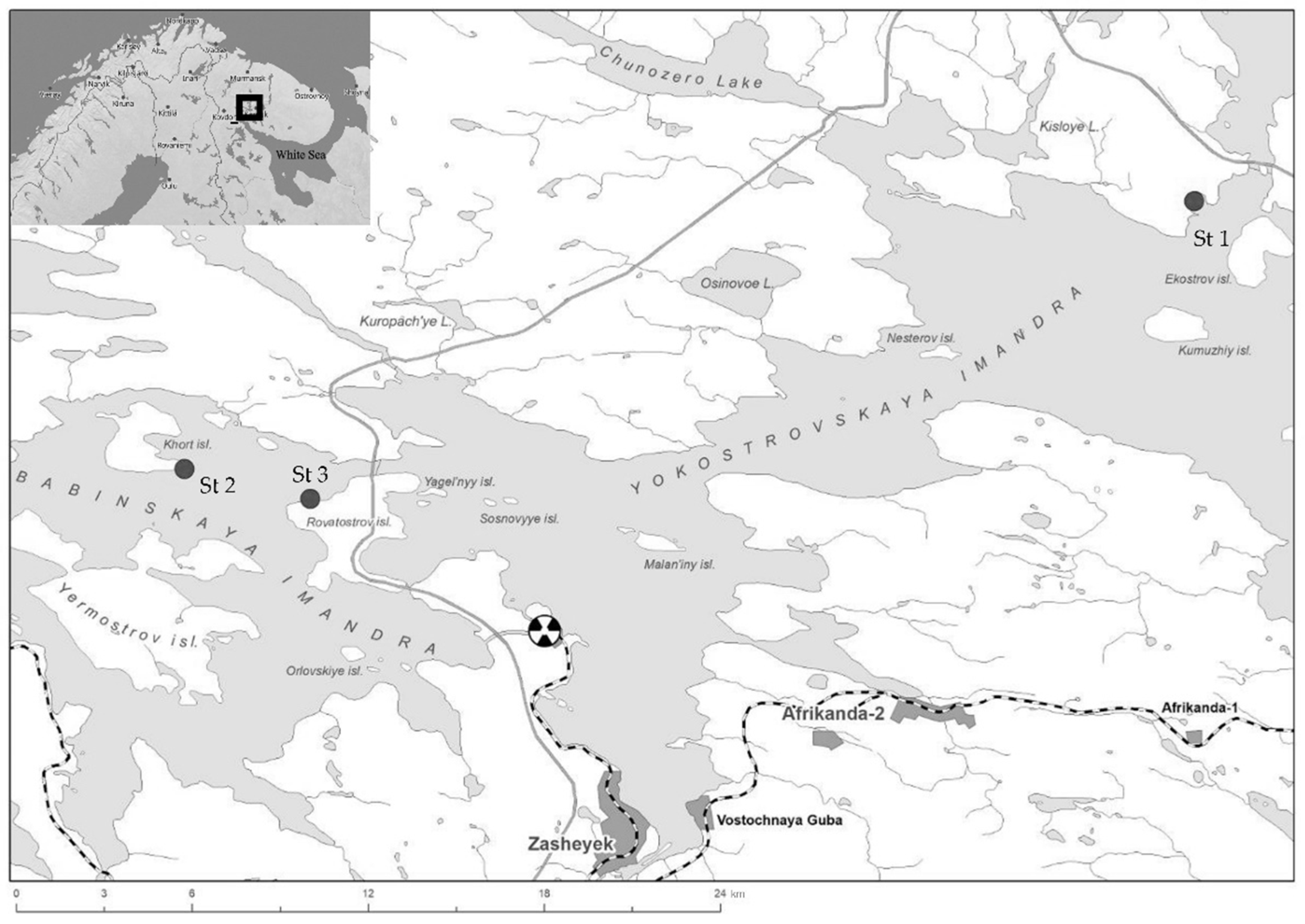

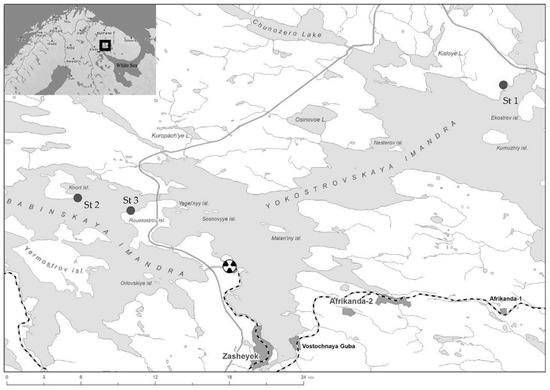

Lake Imandra is the largest lake in the Murmansk region (a region with a subarctic climate), with a complex morphology and a vast drainage area. Lake Imandra consists of three distinct stretches: Bolshaya Imandra (327.5 km2, max depth 67 m), Yokostrovskaya Imandra (361.9 km2, 42 m), and Babinskaya Imandra (191 km2, 43.5 m) connected by narrow straits. The lake is vulnerable to airborne pollution from industrial operations like mining, nonferrous metallurgy, energy, and transportation. According to recent assessments, Bolshaya Imandra is characterised as having a eutrophic-mesotrophic status, while Yokostrovskaya Imandra is classified as mesotrophic. In contrast, Babinskaya Imandra is approaching an oligotrophic state [30]. The northern reach of the Bolshaya Imandra is the most polluted part of the lake, receiving wastewater from the Olkon, Severonikel, and Apatity mining and metallurgical plants, as well as domestic wastewater from coastal cities (Monchegorsk, Kirovsk, and Apatity). Therefore, in this study, we focused primarily on areas of the lake without notable anthropogenic impact, i.e., those located in the Yokostovskaya and Babinskaya Imandra (Figure 1). The main hydrological and production parameters for the studied stations (St. 1, St. 2, and St. 3) in Lake Imandra are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic map of Lake Imandra with marked sites of sample collection. St 1—Biostation KSC RAS, St. 2—Island Khort, St. 3—Shirokaya Salma, Rovatostrov.

Table 1.

Some physical and chemical characteristics of study stations. TP is total phosphorus; TN is total nitrogen and Chl a is Chlorophyll a.

2.2. Sample Collection

Planktonic, benthic, and fish samples were collected from late June to September 2024 at sample stations. Planktonic crustaceans were gathered using a Juday net from the lake surface (0–5 m). Benthic animals and macroalgae were collected with a bottom grab and a hand net (in a shallow zone). Fish were caught in the littoral and profundal zones of the lake. Catches were carried out by a standard set of gill nets, 30 m long and 1.8 m high, with mesh sizes of 20, 25, 35, 40, 45, and 50 mm, made of nylon monofilament. Each net was fixed separately from the other in the littoral zone and in the profundal zone, up to 10 nets in one series. The nets were set up at two to three locations at each station for several hours. All measurements of fish were performed according to standard procedures described in detail previously [13]. The identification of ecological morphs of whitefish was carried out using the number of gill rakers on the first branchial arch. The number of gill rakers ranges from 16 to 30 for the sparsely rakered form, from 31 to 42 for the medium form whitefish, and from 43 to 65 for the densely rakered form [13]. The ages of the fish were identified by different bone structures—scales in coregonid and osmerid fishes and gill covers and cranial vertebrae in percid fishes [13].

2.3. Stomach Content Analysis

Stomach content analysis (SCA) can help describe the composition of a fish diet [31]. We collected fish stomach samples immediately after euthanising and measuring the fish and processing them under the stereomicroscope MBS-10 (LOMO, St. Petersburg, Russia). We assess prey abundance (quantity of prey in stomachs, N) and frequency of occurrence (F), or the proportion of fish carrying a certain prey item in their stomachs. Planktonic creatures have a substantially lower stomach volume than benthic organisms and fish, and so can be overstated by counting the number of prey pieces. Furthermore, because food items such as macrophytes and fish tissues are difficult to quantify, the relative mass (M) percentage (relative volume of food items [31], %) was used to describe the food spectrum of fish (Table S1).

2.4. Trophic Web Analysis

We collected muscle tissue of fish for stable isotope analysis (SIA) for each species, at least from three individuals (Table 2), from each study station in the lake. Using a scalpel, we removed a small fragment of dorsal muscle from the left side of the fish, anterior to the dorsal fin. Whole bodies of small fish (<40 mm in length) without guts were used. We also collected primary producers—filamentous algae (benthos, periphyton) and particulate organic matter (phytoplankton)—as well as consumers—zooplankton, mysids, amphipods, molluscs, hirudineans, and insect larvae. Fish muscle fragments and invertebrates were frozen at −20 °C until further processing in the laboratory.Before being frozen, invertebrates were kept for 10 h in clean water to evacuate their gut of food. The samples were then dried at 60 °C for at least 48 h. Samples of animals with carbonate carapaces were decarbonised using 10% HCl before being thoroughly rinsed with deionised water. The prepared samples were kept at −20 °C prior to weighing for SIA.

Table 2.

Size characteristics of fish (fork length (FL) ± 0.1 cm, mass ± 1 g); sample size for analyses of the stomach content analysis (SCA), stable isotope analysis (SIA), and trophic positions (TP) of fish in catches from Lake Imandra.

The isotopic composition was determined using a Flash 1112 Elemental Analyzer and a Thermo Delta V Plus isotope mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at the Joint Usage Centre “Instrumental Methods in Ecology” of the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution (Moscow, Russia) according to the method described previously [18]. Around 300 μg of animal material and 1000 μg of plant material were wrapped in tin foil and weighed using a Mettler Toledo MX5 (Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA).

The nitrogen and carbon isotopic compositions were expressed as thousands of the deviation from the international standard δ (‰) as follows:

where X is the element (nitrogen or carbon), and R is the molar ratio of heavy to light isotopes in the analysed sample and the standard. For nitrogen, the standard is atmospheric N2, and for carbon, the “Vienna” equivalent of belemnite from the PeeDee Formation (VPDB). The standard deviations of δ15N and δ13C values in laboratory standards (casein B2155) were <0.15‰. δ13C values for consumers with a C:N ratio >3.5 were adjusted according to [32].

δX (‰) = [(Rsample–Rstandard)/Rstandard] × 1000

2.5. Data Analyses

All data were presented as arithmetic means with standard deviations (SD) or standard errors (SE). Coefficient variation was calculated as the ratio of SD to mean values, expressed in %. Similarity between fish was analysed with the Bray–Curtis index. Linear regression was analysed between FL (body length of fish) and isotopic composition of nitrogen (δ15N).

Determination of fish dietary status (generalist or specialist) was conducted using a similar approach to that proposed earlier by [33] and later in [34]. We displayed data as graphs of prey abundance vs. frequency of occurrence, i.e., the fraction of fish carrying a certain prey item in their stomachs. Diet plots indicate a generalised diet and high individual variability when the dots fall in the lower portion of the plot. Fish food specialisation is represented at the top of the plot, with individuals specialising in a specific prey in the upper left corner and populations in the upper right corner. When all dots lie along or below the diagonal from the upper left to the lower right corner, the species has a wide trophic niche width.

To characterise the diet of fish (vendace, perch, and ruffe) quantitatively, a modified index of relative significance (IR) was used [35]:

where F is the frequency of occurrence of each food item, M is the proportion by mass, and the value of i varies from 1 to n (n is the number of food items). We calculated the index based on data combined for all study sites to compare the similarity of the food base between fish.

IR = (FiMi/ ∑ FiMi) × 100%

The heavy isotopes (15N and 13C) are enriched in the food chains compared to the lighter isotopes (14N and 12C) by 3–5‰ (for δ15N) and 0–1‰ per trophic level (for δ13C, [36]). The trophic position of fish was determined by comparing their δ15N values with those of herbivores (basal consumers) in the case where a trophic link was established between them [36]. We used the following formula:

where δ15Nc is the ratio of nitrogen isotopes in predacious consumers (the taxon in question), Δ15N is the trophic enrichment factor (fractionation per trophic level; it was 3.4 according to [36]); and δ15Nb and TPb are the average nitrogen isotope and trophic position of baseline, with corresponding constants of TPb = 2 (corresponds to trophic level 2). The dietary status of consumers was detected on the TP values using the following criteria [18]:

TPc = (δ15Nc − δ15Nb) / Δ15N + TPb

TP values vary from 2 to 2.5; the consumer is herbivorous.

TP more than 2.5 and less than 3: it has a mixed plant-animal diet (omnivores).

TP more than 3 to 4: it belongs to first-order predators (Predator I).

TP more than 4: the consumer is a second-order predator (Predator II).

Differences in studied variables between fish were analysed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney paired comparison in the software package PAST (https://past.en.lo4d.com/windows; accessed on 5 November 2025).

Core isotopic niche width and overlap among fish species were quantified in bivariate δ13C–δ15N space using the SIBER (Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R) package (https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01806.x) in R (R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria (2020). For each species, we estimated 40% maximum-likelihood standard ellipses (i.e., core isotopic niches) based on the bivariate normal distribution of δ13C and δ15N values. Pairwise overlap of these 40% core ellipses was then calculated using the maxLikOverlap function. For each species pair, we expressed overlap both as an absolute area and as relative indices, including the proportion of the summed niche area and the proportion of the smaller ellipse that was overlapped. Ellipses were visualised using the ggplot2 package (https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.147).

3. Results

3.1. Composition of Fish in Catches

Lake Imandra is rich in fish, including whitefish, vendace, pike, ide, burbot, perch, lake trout, grayling, and others. The catches in the study periods (late June and late September) included the most common species. Altogether, seven species of fish were included in this study (Table 2). The catches included the most common species, altogether seven species of fish (Figure S1, Table 2). The dominant species (>20% of catches) included perch, whitefish, and ruffe, together accounting for up to 90% of catches. Whitefish was represented by a single ecological morph—the large, sparsely rakered whitefish. The number of gill rakers on the first branchial arch varied from 16 to 27 rakers. In the Yokostrovskaya Imandra (St. 1), whitefish were aged 1 + to 9 + years, with the modal age being 4 + years. In the Babinskaya Imandra (St. 2 and St. 2), individuals aged 6 + to 9 + years, with the most common age groups being 6 + and 8 + years, represented whitefish. In the Yokostrovskaya Imandra, perch were represented by five age groups ranging from 3 + to 7 + years; the modal age was 3 + and 5 + years. In the Babinskaya Imandra, perch ranged from 2 + to 10 + years, and the modal age was 6 + years. Smelt were represented by ten age groups (from 1+ to 10 + years), and vendace by seven age groups (from 0 + to 6 +).

3.2. Stomach Content Analysis

Table S1 presents the main quantitative characteristics of food items in the fish diet studied at all stations. Although we found negligible differences in food item composition and quantity between study stations for the same species, the dietary patterns and dominant groups were rather similar. Planktonic crustaceans (including Bythotrephes sp. and Bosmina sp.), benthic amphipods, and chironomids were found in the stomachs of whitefish >20 cm in length. As the whitefish size increased, the proportion of benthic organisms in its stomach contents increased, primarily molluscs (genera Lymnaea, Sphaerium, and Valvata) and trichopteran larvae (Phryganea bipunctata). In specimens >30 cm of FL, only representatives of these two groups were found in the stomach contents. Previously, in the same areas of the lake, some stomachs of whitefish (FL = 20.0–29.9 cm) contained sticklebacks (P. pungitius), and fish eggs were found in 50% of whitefish (although we did not observe fish in the stomachs of the catches of 2024).

The perch had a more diverse diet than the whitefish. Fish were essential in the diet of perch, including vendace, ruffe, and stickleback. Larvae of trichopterans (P. bipunctata) were the perch’s second most important source of food. A small number of mysids (Mysis sp.), amphipods (Monoporeia affinis), chironomids, and gastropods (Lymnaea sp.) were also found in their stomachs. The perch had a characteristic age-related change in diet composition, moving from a benthivorous stage to a piscivorous one. Perch (FL up to 19 cm, aged 2 + to 4 + years) consumed primarily benthic invertebrates—trichopterans, mysids, and chironomids. Fish appeared in the diet of perch at its total length above 19 cm at the ages of 3 + −10 + years, but even at this age and a total length of up to 30 cm, approximately 40% of perch continued to feed on benthic invertebrates.

The diet of the ruffe was dominated by chironomids (>60%) and amphipods (M. affinis), and, to a lesser degree, large larvae and imago of ephemeropterans (E. vulgata) and trichopterans (P. bipunctata). The number of individuals of the other fish species (vendace C. albula, smelt O. eperlanus, stickleback P. pungutius, and burbot L. lota) was insufficient in catches (Table 2) for a detailed dietary analysis, but we conducted a preliminary evaluation of stomach content composition. The stomachs of vendace (FL up to 10 cm) contained cladocerans Bosmina sp. primarily; those of larger fish (FL up to 20 cm) consisted of large cladocerans Bythotrephes sp., copepods Cyclops sp., chironomid larvae and pupae, emerged imago (trichopterans), as well as benthic organisms—gastropods (Valvata spp.) and bivalve molluscs (Sphaeriidae). The diet of smelt (FL 110–150 mm) contained Bosmina sp., trichopteran imago, and fish (vendace and stickleback). The nine-spined stickleback fed primarily on larvae of chironomids. The stomachs of burbot contained only fish, up to 7 individuals per stomach (mainly vendace and, to a lesser degree, ruffe).

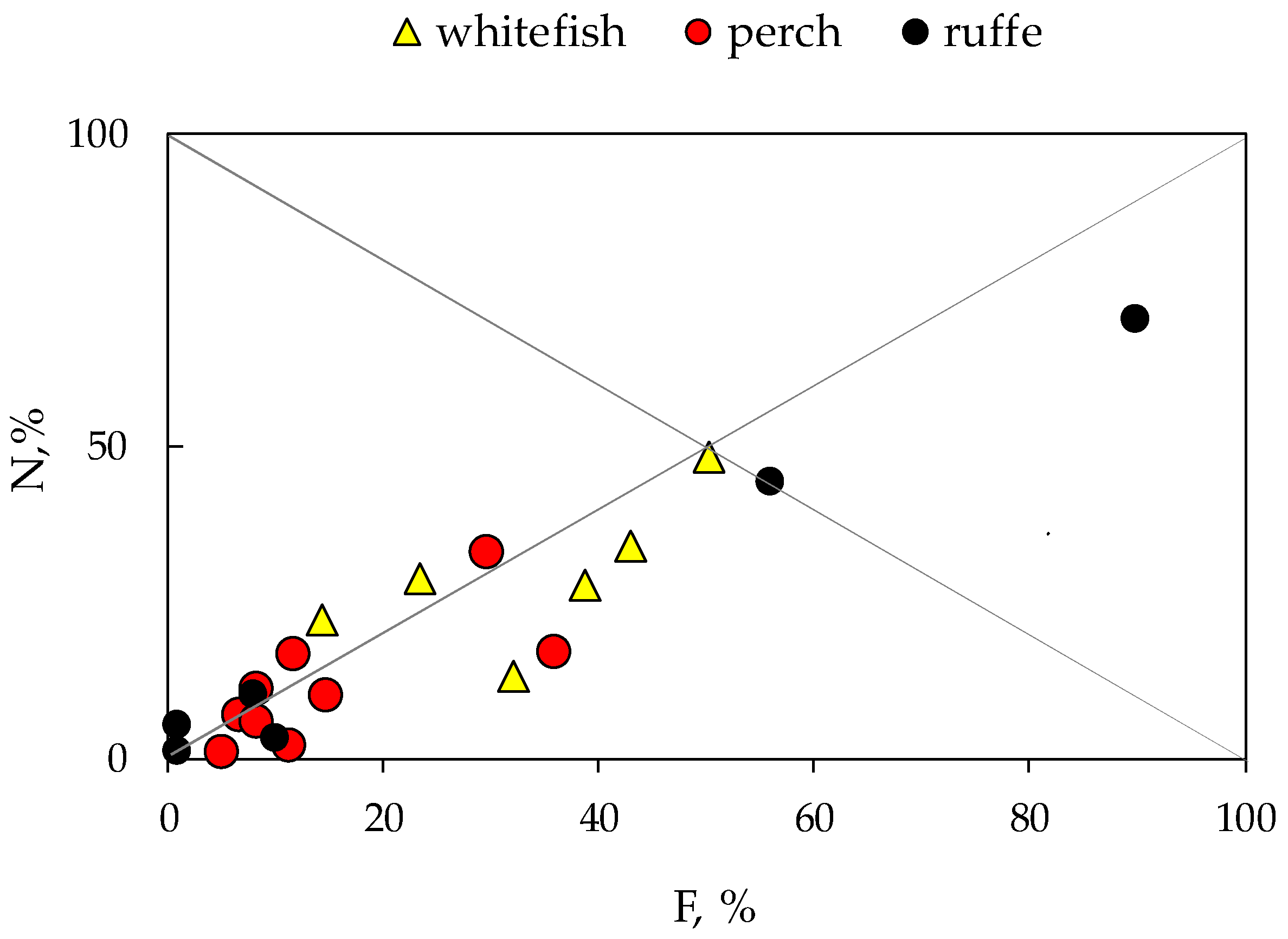

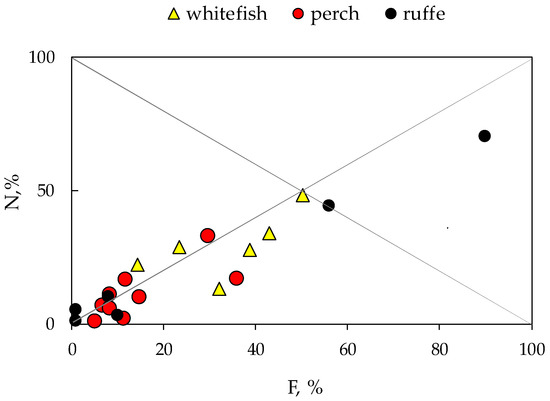

Diet plots (Figure 2) indicate a generalised diet of perch and whitefish with high individual variability in the food spectrum.

Figure 2.

Diet plot of prey abundance (N,%) vs. frequency of occurrence (F, %) in the stomach content of fish: European whitefish Coregonus lavaretus (whitefish); European perch Perca fluviatilis (perch); and Eurasian ruffe Gymnocephalus cernua from Lake Imandra.

Most dots are in the lower portion of the plot below the diagonal from the upper left to the lower right corner; therefore, both perch and whitefish had generalist status. Ruffe shows population specialisation, preferring larvae of chironomids (Chironomus sp.). At the same time, all fish are characterised by wide trophic niches, using mixed feeding strategies.

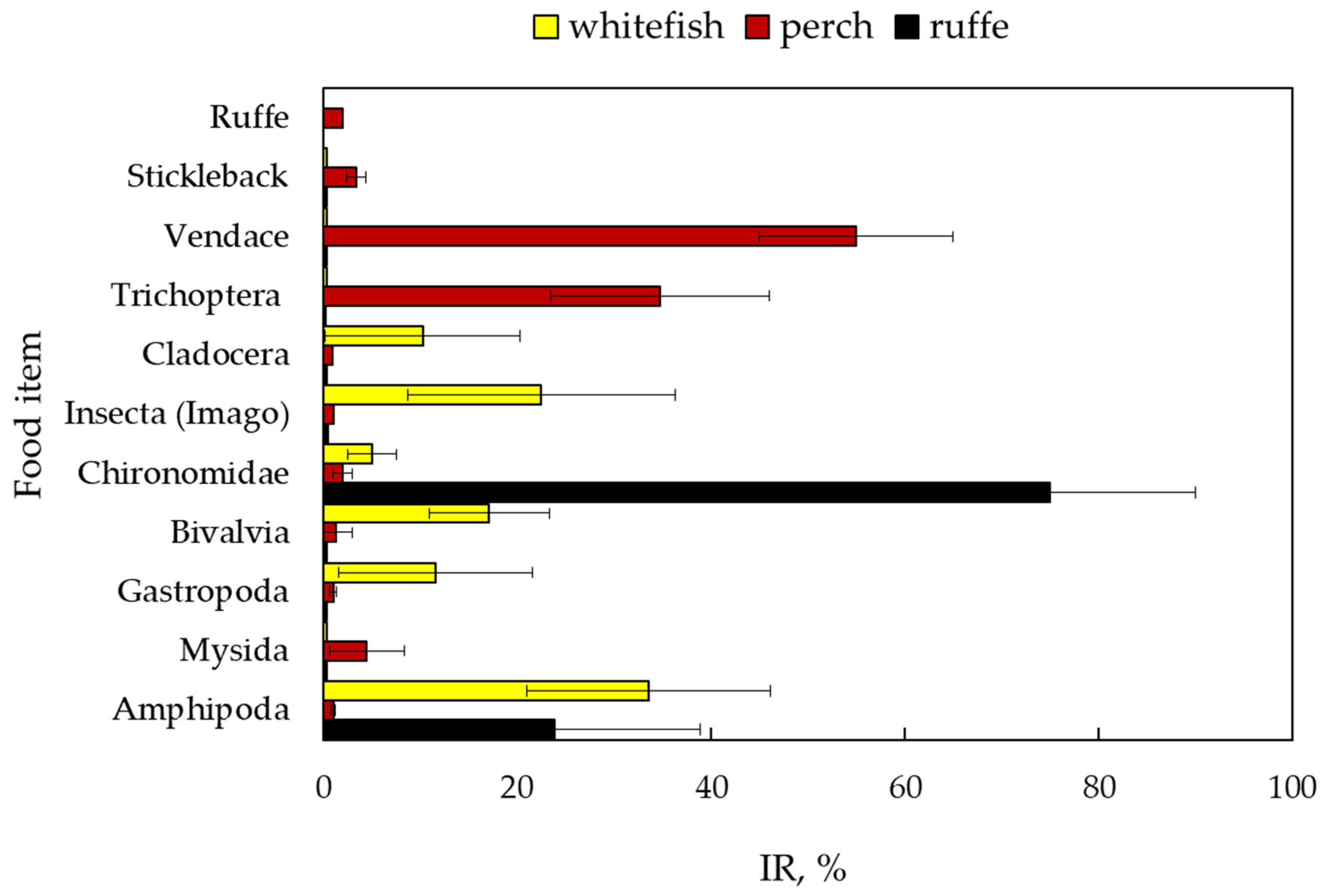

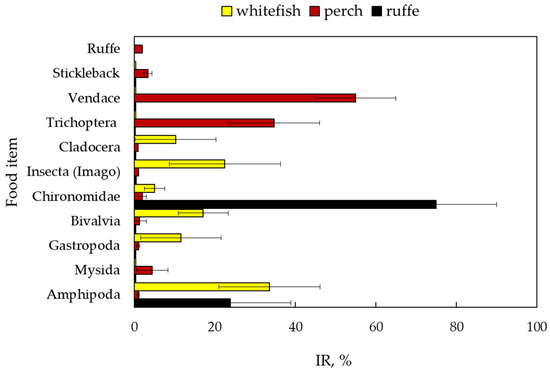

The relative importance (IR) of different prey items in the diet varied for all fish (Figure 3). The most important components of the perch diet were vendace (IR–55%) and trichopteran larvae (34.7% of all components and 77% of invertebrates). Trichopteran imago, emerging from the lake, accounted for 22.5% of the importance of the whitefish diet. Amphipods (33.6%) and molluscs (11.5% for gastropods and 17.1% for bivalves) were also the dominant components in the whitefish diet.

Figure 3.

Percentage IR (mean±SE) in % of various food items in the stomach content of fish: European whitefish Coregonus lavaretus (whitefish); European perch Perca fluviatilis (perch); and ruffe Gymnocephalus cernua from Lake Imandra.

Since the perch diet consisted primarily of fish, comparisons of dietary similarity were made for the invertebrate-feeding group of perch, excluding perch at the piscivory stage. Diet similarity for the three fish species was calculated as 30% (Bray–Curtis similarity index) for pairs of ruffe and whitefish and perch and whitefish, while for perch and ruffe, it was less than 15%. Larvae and adult aquatic insects emerging from the lake (trichopterans and ephemeropterans), presenting the same food source, made a significant contribution to the diet of both perch and whitefish. When combining larvae, pupae, and adults into one group, “aquatic insects”, the Bray–Curtis index for dietary similarity between perch and whitefish reached 48%, indicating moderate food competition between these species.

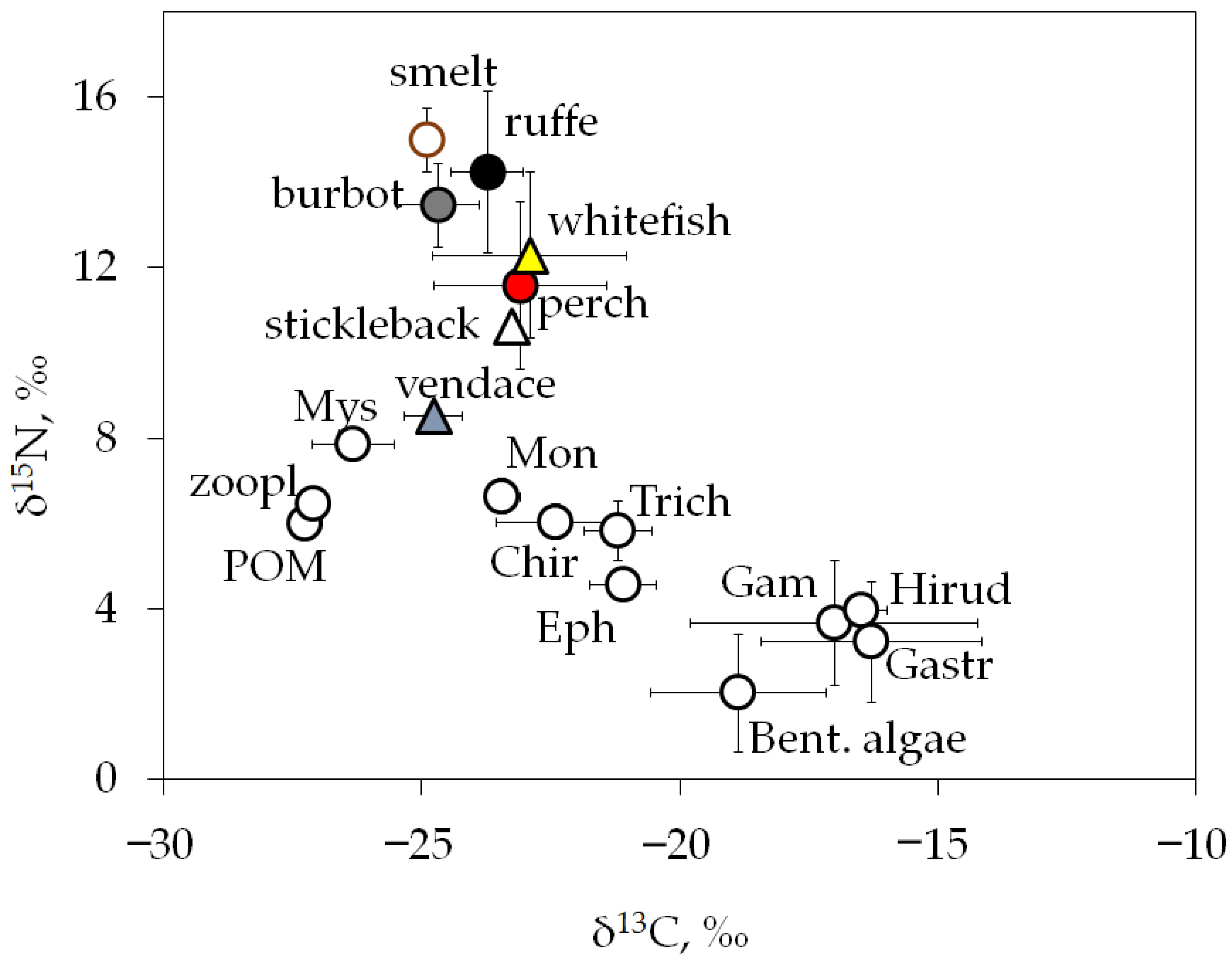

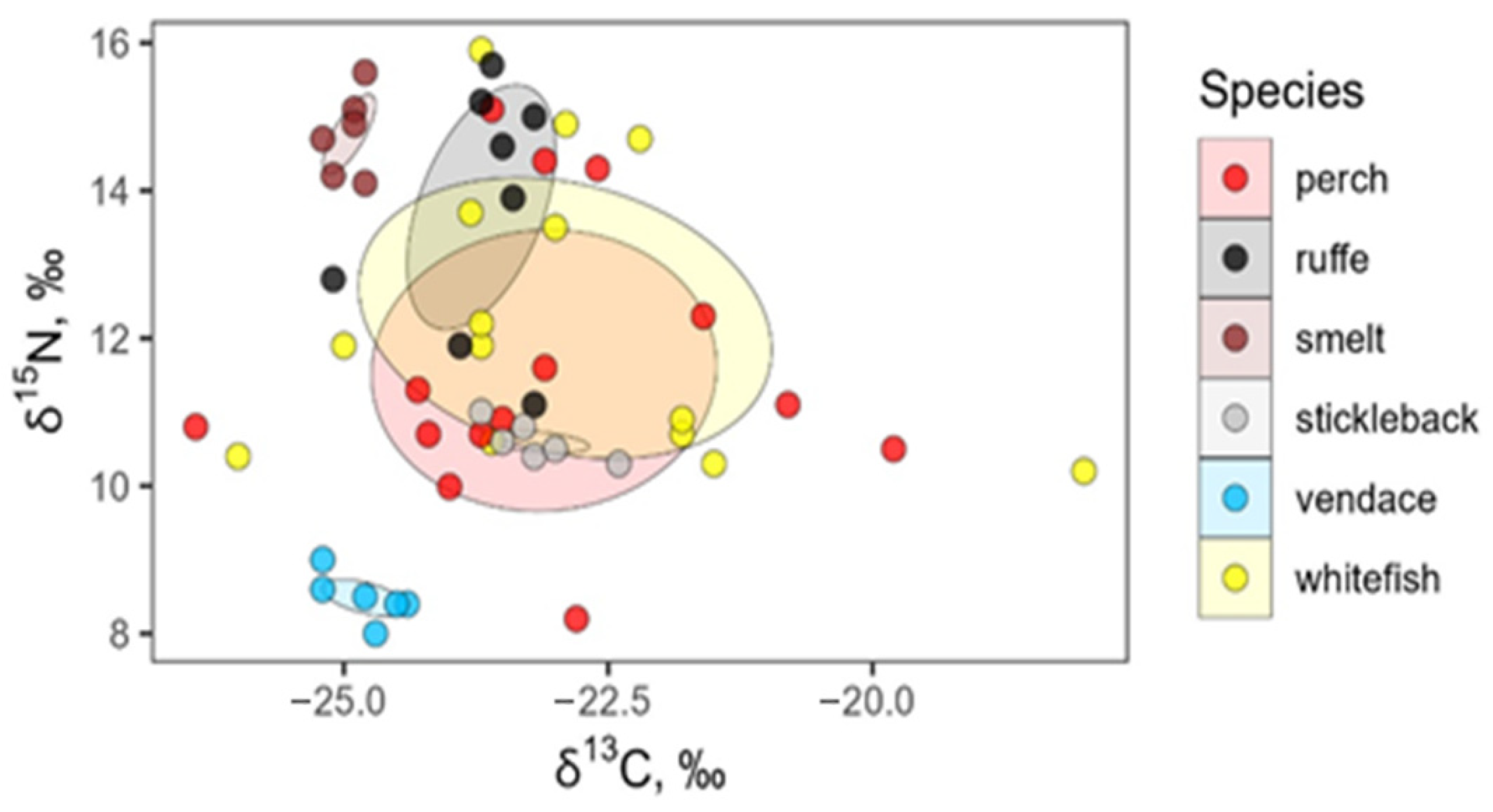

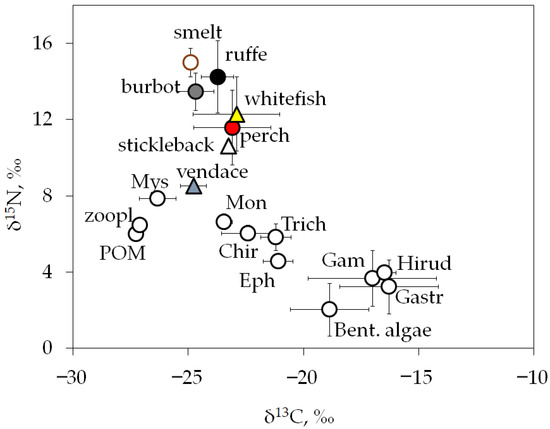

3.3. Stable Isotope Analysis

The lake’s food web had average δ13C values from −27.3 ± 0.0‰ to −16.3 ± 2.1‰, indicating a diverse range of basal carbon sources and a diversified diet for most fish species (Figure 4). According to carbon isotope values, vendace, smelt, and burbot were most closely related to pelagic sources (δ13C values ranged from −27 to −25‰), whereas perch, whitefish, and ruffe were more fed by benthic food web compartments (δ13C values ranged from −24 to −21‰). The amphipod Gammarus lacustris, gastropods Lymnaea stagnalis, and hirudineans Erpobdella octoculata were closely related to littoral producers (filamentous algae and periphyton communities on hard substrates) with δ13C values in the range from −17 to −16‰ (Figure 4). Whitefish and perch showed wide carbon isotopic niches (δ13C values −22.9 ± 1.9‰ and −23.1 ± 1.7‰, respectively), indicating a mixed diet and possible notable overlap in carbon sources.

Figure 4.

Biplots of mean values (± SD) of isotopic compositions, δ13C and δ15N (‰), for lake food web producers, consumers, and fish, combined values for three study sites. Designations: POM—particulate organic matter; zoopl—mesozooplankton (mix of species); Bent. Algae include periphyton community; developed on hard substrates; Mys—mysids Mysis sp.; Mon—Monoporeia affinis; Trich—trichopterans Phryganea bipunctata; Chir—chironomid larvae (mix of species with dominant Chironomus sp.); Eph—ephemeropteran Ephemera vulgata; Gam—amphipod Gammarus lacustris; Hirud—hirudinean Erpobdella octoculata; Gastr—gastropod Lymnaea stagnalis. Fish species: perch, Perca fluviatilis; ruffe, Gymnocephalus cernua; smelt, Osmerus eperlanus; stickleback, Pungitius pungitius; vendace, Coregonus albula; and whitefish, Coregonus lavaretus.

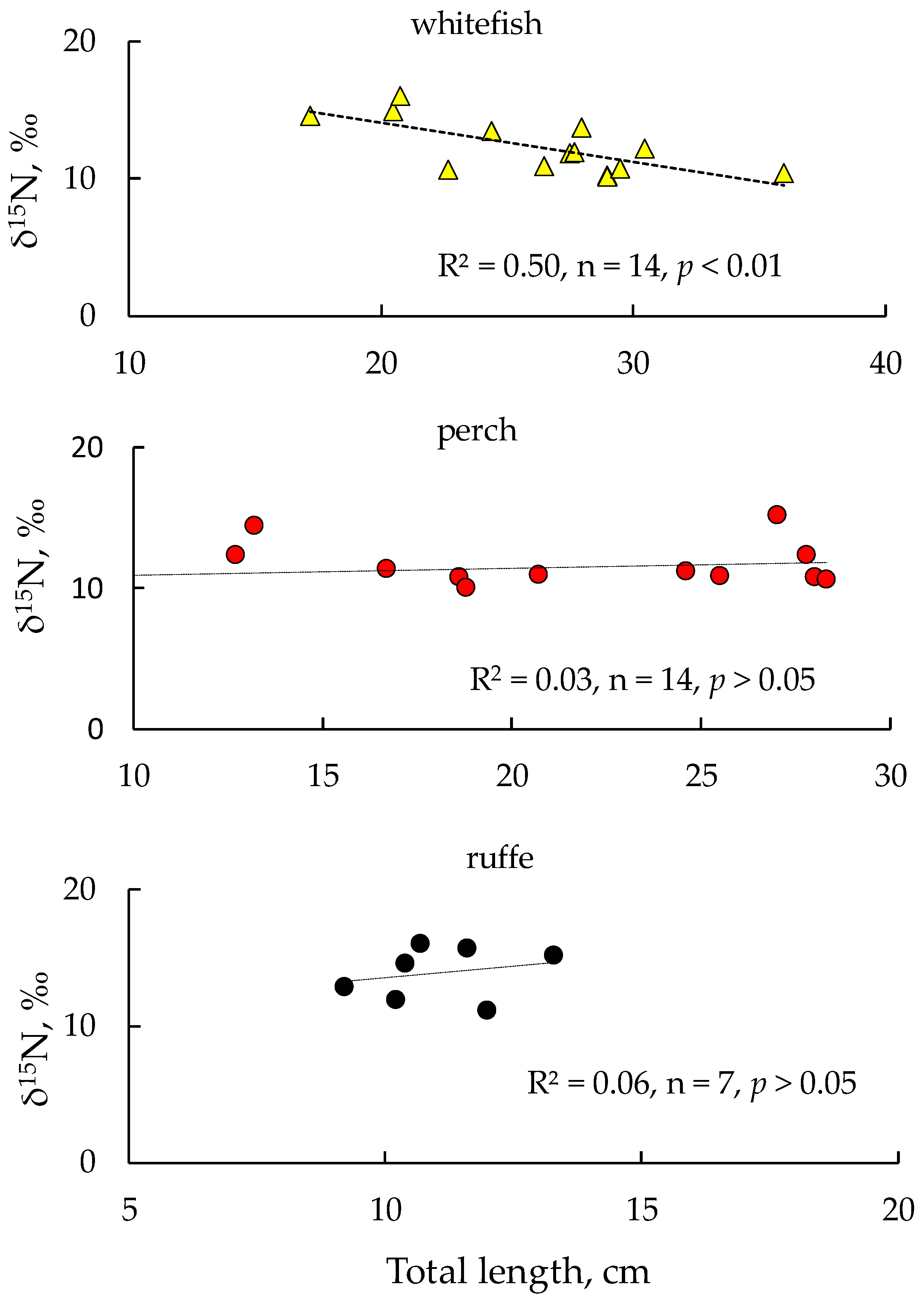

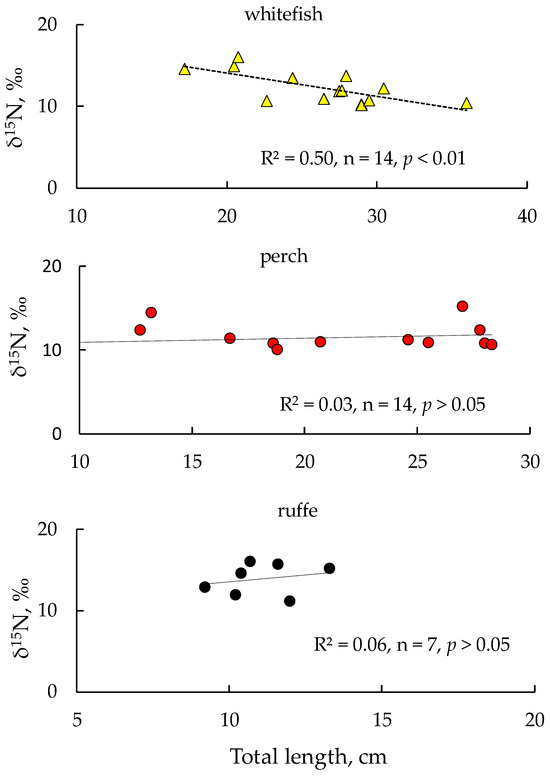

The highest average δ15N values were found in smelt and ruffe (15.0 ± 0.7‰ and 14.2 ± 1.9‰, respectively). We did not find any significant differences in δ15N values between perch and whitefish (p > 0.05). We examined the data for correlations between fish length and δ15N values for each species and found significant relationships between the total length of whitefish and δ15N values in their tissues. This is mediated by a change in the food preferences as whitefish increase in body size, when the diet, instead of planktonic cladocerans and benthic amphipod crustaceans (Monoporeia affinis), becomes dominated by large molluscs (Lymnaea), which have significantly lower nitrogen isotope signatures than crustaceans (Figure 5). Unlike whitefish, no significant relationships were found between δ15N values and fish length in the case of perch and ruffe (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dependence of δ15N values on body size of fish: European whitefish Coregonus lavaretus (whitefish); European perch Perca fluviatilis (perch); and ruffe Gymnocephalus cernua from Lake Imandra.

Bray–Curtis similarities for δ13C and δ15N values between perch and whitefish were determined to be 100% and 89.5%, respectively. At the same time, the isotopic composition values of these fish species differ significantly from those of stickleback, vendace, and smelt. The differences in δ15N values between vendace, stickleback, and smelt were significant (Kruskal–Wallis test, Mann–Whitney post hoc comparison, all p < 0.05, Table S2). However, vendace and smelt have no significant differences in the δ13C values (Mann–Whitney, p = 0.52); they had energy sources in the same locations, but the higher δ15N values of smelt indicate their predation on vendace.

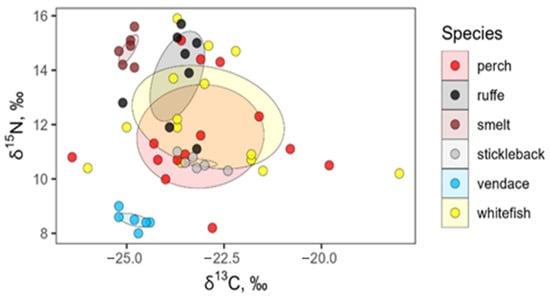

Using 40% standard ellipses in δ13C–δ15N space, we found pronounced differences in core isotopic niche width and degree of niche overlap among fish species. Figure 6 shows significant overlap in the δ13C and δ15N values of whitefish and perch that had the broadest core niches (12.3 and 10.6‰2, respectively). Ruffe showed an intermediate niche area (3.8‰2), while vendace, smelt, and stickleback had very small core niches (<0.4‰2).

Figure 6.

Overlap in isotopic composition (δ13C and δ15N) among six fish species: perch, Perca fluviatilis; ruffe, Gymnocephalus cernua; smelt, Osmerus eperlanus; stickleback, Pungitius pungitius; vendace, Coregonus albula; and whitefish, Coregonus lavaretus. Points represent individual fish, and shaded polygons show 40% maximum-likelihood standard ellipses for each species.

The 40% core ellipses of whitefish and perch overlapped substantially (8.3‰2), corresponding to 36% of their combined area. Ruffe’s core niche overlapped moderately with those of whitefish and perch (2.5 and 1.3‰2; 20–35% of the ruffe core ellipse), whereas vendace and smelt showed no core overlap with any other species. The core niche of stickleback was almost entirely nested within that of whitefish and completely nested within that of perch, but its core area was only 0.3‰2 (Table S3, Figure 6).

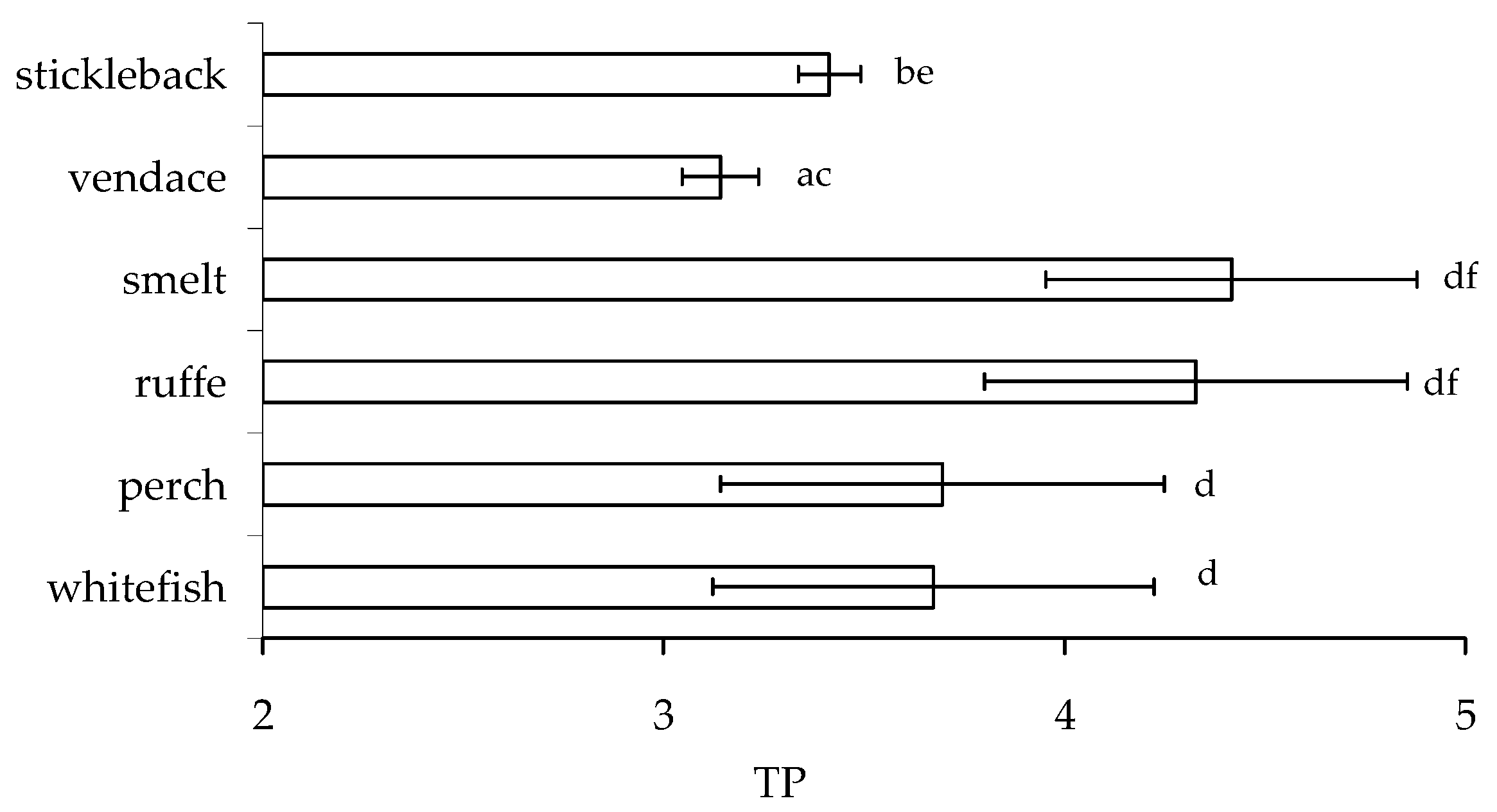

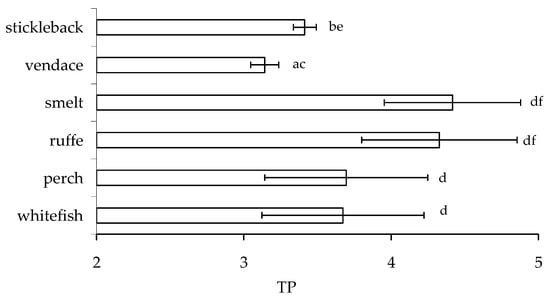

The significant differences in δ15N and trophic positions (TP) of smelt, ruffe, and other species of fish were found (Figure 7). The trophic position of stickleback and smelt differed significantly from other fish (p < 0.05), with the lowest TP in vendace. Higher δ15N values in the same omnivorous fish species indicate greater mixing of food resources, as well as potentially greater predation. There were no significant differences in trophic position between whitefish and perch, as well as ruffe and smelt (Figure 7, Mann–Whitney comparisons, p > 0.05).

Figure 7.

Trophic position (mean ± SD) of studied fish: European whitefish, Coregonus lavaretus; European perch, Perca fluviatilis; ruffe, Gymnocephalus cernua; European smelt, Osmerus eperlanus; European vendace, Coregonus albula; and nine-spined stickleback, Pungutius pungutius in the food web of Lake Imandra. Different pairs of letters, a-b,c-d, e-f… show significant differences (at p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The use of two methods (SCA and SIA) to study the trophic relationships of coregonid and percid fish in a subarctic lake ecosystem allowed us to identify features of the food web structure and the position of fish in relation to food sources. A similar approach has previously been used in a number of studies to visualise fish trophic relationships and examine the ontogenetic shift in fish within a trophic niche [25,37,38]. Both methods indicate a strong overlap in diet composition and isotopic niches between the whitefish and perch. Perch and whitefish were found as generalists and apparently fed at multiple trophic levels. The niches of ruffe also overlapped moderately with the niches of whitefish and perch. Stickleback shares the central isotopic space with both whitefish and perch. At the same time, segregation of the small pelagic species (vendace and smelt) from them was found.

High levels of omnivory and a mixed diet were found in all fish (excluding ruffe). We have previously confirmed this omnivorous trait in fish (vendace, perch, and whitefish) for this and other subarctic lakes [13,17,18]. The omnivory of fish is an adaptive ability to survive in the conditions of Arctic lakes with a deficit of pelagic resources due to additional nutrition in the benthic and coastal compartments of the food web. A recent review of predator omnivory [39] found that high levels of omnivory in fish and aquatic organisms are characteristic features of freshwater food webs [40,41,42]. Furthermore, productivity in Arctic lakes may vary within a single system, accompanied by fluctuations in the quantity and quality of organic sources, causing a shift in the trophic position of fish in the food web [43].

Based on carbon isotope values, vendace, smelt, and burbot were most closely related to pelagic sources (zooplankton and mysids), whereas perch, whitefish, and ruffe were more fed by benthic food web compartments. A close relationship between pelagic components (zooplankton and mysids) and vendace, and then the fish that consume vendace (burbot and smelt), was revealed. Although vendace has previously been noted to consume benthos [17,18,44,45] in conditions of scarcity of planktonic crustaceans, in the long term, it prefers pelagic food sources [46]. It has a pronounced seasonal dietary pattern and, when choosing food sources in the autumn and winter, prefers planktonic copepods and cladocerans, while in the warm summer period, it may obtain energy from benthic crustaceans. In the case of the studied lake, its close relationship in δ13C values with mysids is evident, which may be an important component of its diet. A preferential feeding of vendace on mysids has also been noted in other lakes [45]. Mysids were consumed selectively by vendace during seasons when their abundance in the pelagic zone was high, and mesozooplankton availability was low [45]. Vendace populations are characterised by high seasonal variability in feeding and the contribution of various groups of benthos and plankton to their diet [17]. For example, in a small subarctic lake (Northern Karelia), benthic amphipods (Gammarus lacustris and Monoporeia affinis) were the main predicted food items in the summer diet of vendace, contributing up to 67–75%, while planktonic crustaceans and insect larvae were important (37–54% and 24–42%, respectively) in its diet in autumn and winter [17,18]. Other fish were close to carbon sources originating from aquatic insects (trichnopteran and ephemeroptean larvae, as well as their emerging imago) and amphipods (M. affinis).

In the case of whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus), we did not obtain isotopic evidence of its adequate plankton intake, although we did detect large cladocerans (Bythotrephes) in perch stomachs. The benthic diet of whitefish is likely related to the insufficient pelagic sources and possible competition for them with vendace, which also supplemented the lack of planktonic crustaceans with emerging imago of aquatic insects. Competition for plankton has been observed between whitefish (C. lavaretus) and vendace (C. albula) in the subarctic Pasvik River system in northern Norway and Russia, which share almost identical diets [47]. Therefore, the presence of vendace, a specialised planktivore, may reduce the availability of zooplankton as prey for the more generalist whitefish. In addition to this reason, our study presents a sparsely rakered morph of whitefish, which, as noted earlier, feeds mainly on zoobenthos, in contrast, for example, to the densely rakered morph, whose diet is usually dominated by zooplankton and other pelagic species [48].

By examining the relationship between size characteristics and δ15N values, a size-related change in whitefish prey was revealed, namely, a transition from feeding on crustaceans to molluscs (especially large gastropods, Lymnaea stagnalis) with increasing body size of whitefish. As an organism grows, its energy requirements increase and its food preferences change. A change in prey also leads to an ontogenetic shift in the food niche [49]. Previously, it was shown that whitefish can exploit a variety of prey items, feeding on alternative prey if the abundance of primary prey declines (for example, amphipods Diporeia in the case of the Great Lakes; see [50]). The switch from the preferred food, such as amphipods (M. affinis) in smaller whitefish to items, such as aquatic insects and molluscs, in larger whitefish also shows a trend towards lower δ15N values in whitefish (corresponding to the lower values in molluscs compared to amphipods and aquatic insects). Thus, a change in the whitefish’s diet with increasing size was reflected in its isotopic signature, displaying a large, stable isotopic niche space.

The discovery of bivalves of the family Sphaeriidae and gastropods (Lymnaeidae) in the diet of whitefish was surprising. At the same time, some studies [24,51] named these molluscs among the most characteristic prey of whitefish. Ephemeroptera and Trichoptera were found as the most frequent prey category used by whitefish at the population and individual levels [52]. The preference of whitefish for emerging imago of trichopterans and of perch for larvae of trichopterans was noted in our study and in other lakes (Lake Padashulkajärvi, northern Karelia [24]). The authors of the latter study [24] interpret these feeding habits as a spatial separation of trophic niches between coexisting whitefish and perch, causing competition reduction. However, it is worth noting that both larvae and emerging trichopterans originated from the same lake resource (Phryganea bipunctata). The use of trichopterans as the main food source by both fish species, in fact, creates competition for this resource, as evidenced by the higher index of dietary similarity (up to 50%) and the almost complete overlap of the isotopic niches of whitefish and perch in the studied lake. The same high degree of competition (53.6%) between whitefish and perch was observed in Karelian lakes (Sundozero), where species competed for four food sources—zooplankton, ephemeropterans, trichopterans, and molluscs [53]. Trophic niche overlap depends on the body size of coexisting fish and is also linked to seasonal changes in resource availability, peaking in summer when prey is abundant and small and gradually declining over time as prey becomes rarer and/or larger [40]. Encounter rates in time (prey and predator mobility) and space (habitat use), as well as foraging method, also influenced prey vulnerability and niche overlap but were secondary to the effect of body size [40].

Perch are known for exhibiting distinct ontogenetic niche shifts in their use of food resources, from a predominance of zooplankton to a predation on zoobenthos and fish [20,54]. The switch from perch to predatory feeding was uneven, with part of the population remaining to feed on the benthos at age 3 + and at a body size typical for piscivorous perch. In other lakes, perch also showed slow ontogenetic shifts in their diet due to the wide range of prey used [17,55]. In terms of diet, 3 + –4+ perch in subarctic lakes were characterised by a high proportion of benthic invertebrates (insect larvae and crustaceans) and a low proportion of fish in their diet during all the year, including in the winter [55]. Perch are known to begin to feed on fish predators at a length of 8–10 cm [56,57]. In lakes of northern Karelia, fish were found in the perch diet at a total body length of 16 cm. Thus, the transition to active feeding of perch in northern lakes can occur significantly later (at ages 7–8+) [55] than in other lakes [56,57]. The onset of the piscivorous stage in perch feeding depends on the density and size characteristics of other fish and is apparently associated with an insufficient number of prey of a suitable size.

It is possible that several ecological groups of perch (Perca fluviatilis) exist in this lake, as has been demonstrated for other large lakes. For example, in Volga reservoirs, perch populations are divided into two ecological groups—coastal and pelagic—which are confined to different biotopes and may be characterised by differences in diet composition [58]. In the pelagic zone of Lake Vesijärvi, small perch (<155 mm) fed mainly on the cladoceran Leptodora kindtii; larger perch were piscivorous (fed on smelt). In the littoral zone, small perch foraged on zooplankton and benthic chironomid larvae, and larger perch on chironomids and small perch [59]. In addition, seasonality may have played a role, as variability in the diet of perch has been previously demonstrated, with the summer period (studied by us) being characterised by the highest degree of benthophagy compared to spring and autumn [20]. The availability of resources in the ecosystem is an important factor regulating the transition of perch [59].

The type of feeding of the studied fish (planktivorous, benthophagous, or piscivorous) significantly influences the ratio of stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in the biomass of fish [60]. Ruffe in the study lake fed primarily on chironomid larvae and amphipods. It is known (example from Lake Balaton) that during early developmental stages, this species is planktivorous, while larger ruffe feed primarily on benthic chironomids throughout the year [61]. The higher positions of ruffe compared to perch and whitefish indicate not only their piscivorous nature but also their greater omnivorous nature, possibly due to their ability to consume the fish eggs [62]. In addition, higher values may be associated with the rate of growth and turnover time of organic matter, and shorter-cycle species (such as ruffe) have higher nitrogen ratios than long-cycle species.

This study confirms significant overlap of trophic niches and the presence of food competition between adult perch and whitefish in the study lake. Furthermore, the reported predation of perch on whitefish embryos and juveniles, as well as adult vendace, may contribute to the negative factors affecting whitefish populations. Perch, thanks to favourable climate warming and its food flexibility, will benefit from population growth compared to whitefish. The interactions of juvenile whitefish with other fish were not considered in this study; however, it should be understood that this aspect also requires further investigation, as food competition with whitefish apparently affects a larger number of fish species and may be more intense at early stages of development than in the adult fish studied here. At early stages of life, whitefish can compete for plankton not only with vendace, smelt, and small perch, but also with stickleback. For example, it has been shown that the feeding intensity of three-spined stickleback 0 + was similar to that of whitefish 0+ and larger individuals [63].

5. Conclusions

The study revealed a high degree of similarity in diet and overlap in trophic niches between whitefish and perch. Vendace was a significant component in the diets of piscivorous fish, such as burbot, smelt, and perch. Whitefish, which are represented by a sparsely rakered morph, primarily obtained energy from benthic invertebrates. Meanwhile, perch delays the transition from the benthophagous to the piscivorous stage, competing with whitefish for food items such as aquatic insects and other benthic organisms. Depleted food sources in subarctic lakes and higher dietary flexibility of perch species can facilitate a decrease in population abundance of coregonid species. Significant omnivorousness of other fish (ruffe and stickleback) was also revealed, and although the study did not show their competition with adult whitefish, further studies at earlier stages may be useful to resolve this issue. This finding contributes to the understanding of energy flows and food web interactions in the Arctic region and to predicting future responses of aquatic ecosystems to global climate change.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10120644/s1. Table S1: Main characteristics of the diet: number of food items (N), mass of items (M), and frequency of occurrence of items (F), in % of European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus), European perch (Perca fluviatilis), and ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernua) at sampling stations. Table S2: Significance test for differences in mean isotopic compositions (δ13C; δ15N values) between perch and whitefish. Table S3. The areas of their 40% ellipses (SEAc) in isotopic space (δ13C–δ15N) in ‰ and the overlaps of isotopic niches for pairs of studied fish species. Figure S1: General view of some fish from Lake Imandra. 1—brown trout Salmo trutta; 2 and 4—whitefish Coregonus lavaretus; 3—burbot Lota lota; 5—perch Perca fluviatilis; 6—ruffe Gymnocephalus cernua; 7—smelt Osmerus eperlanus. Photo by Elena M. Zubova.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.B. and P.M.T.; methodology, E.M.Z. and S.M.T.; software, N.A.B.; validation, E.M.Z. and P.M.T.; formal analysis, N.A.B. and S.M.T.; investigation, N.A.B., P.M.T., and E.M.Z.; resources, S.M.T.; data curation, P.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.B.; writing—review and editing, E.M.Z., P.M.T., and S.M.T.; visualisation, P.M.T. and E.M.Z.; funding acquisition, N.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Education of the Russian Federation within state assignments N 125012800888-5 (N.B.); 1024081300010-8 (P.T.) and 124020100060-8 (E.Z.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences I (Permission No. 1-5/19-02-2024; date: 19 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We cordially thank Zakhar I. Slukovskyi and Andrey N. Sharov for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lehtonen, H.; Rask, M.; Pakkasmaa, S.; Hesthagen, T. Freshwater fishes, their biodiversity, habitats and fisheries in the Nordic countries. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2008, 11, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orban, E.; Nevigato, T.; Masci, M.; Di Lena, G.; Casini, I.; Caproni, R.; Gambelli, L.; De Angelis, P.; Rampacci, M. Nutritional quality and safety of European perch (Perca fluviatilis) from three lakes of Central Italy. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalås, A.; Primicerio, R.; Kahilainen, K.K.; Terentyev, P.M.; Kashulin, N.A.; Zubova, E.M.; Amundsen, P.-A. Increased importance of cool-water fish at high latitudes emerges from individual-level responses to warming. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reist, J.D.; Wrona, F.J.; Prowse, T.D.; Power, M.; Dempson, J.B.; Beamish, R.J.; King, J.R.; Carmichael, T.J.; Sawatzky, C.D. General effects of climate change on arctic fishes and fish populations. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2006, 35, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, M.P.; Zimmerman, C.E. Physiological and ecological effects of increasing temperature on fish production in lakes of Arctic Alaska. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 1981–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laske, S.; Rosenberger, A.; Wipfli, M.; Zimmerman, C. Generalist feeding strategies in Arctic freshwater fish: A mechanism for dealing with extreme environments. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2018, 27, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.J.; Chucholl, C.; Brinker, A. Coldwater, stenothermic fish seem bound to suffer under the spectre of future warming. J. Great Lakes Res. 2024, 50, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Mehner, T.; Winfield, I.J.; Kangur, K.; Sarvala, J.; Gerdeaux, D.; Rask, M.; Malmquist, H.J.; Holmgren, K.; Volta, P.; et al. Impacts of climate warming on the long-term dynamics of key fish species in 24 European lakes. Hydrobiologia 2012, 694, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, B.; Myllykangas, J.P.; Rolls, R.J.; Kahilainen, K.K. Climate and productivity shape fish and invertebrate community structure in subarctic lakes. Freshwat. Biol. 2017, 62, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Biela, V.R.; Laske, S.M.; Stanek, A.E.; Brown, R.J.; Dunton, K.H. Borealization of nearshore fishes on an interior Arctic shelf over multiple decades. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 1822–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahilainen, K.K.; Østbye, K. Morphological differentiation and resource polymorphism in three sympatric whitefish Coregonus lavaretus (L.) forms in a subarctic lake. J. Fish Biol. 2006, 68, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrod, C.; Mallela, J.; Kahilainen, K.K. Phenotype-environment correlations in a putative whitefish adaptive radiation. J. Anim. Ecol. 2010, 79, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubova, E.M.; Kashulin, N.A.; Terentyev, P.M. Modern biological characteristics of whitewash Coregonus lavaretus, european vendace C. albula and european smelt Osmerus eperlanus of Lake Imandra. Bull. Perm Univ. Ser. Biol. 2020, 3, 210–226. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalko, N.A.; Tereshchenko, L.I.; Malina, Y.I.; Bazarov, M.I. Seasonal and Interannual changes in the feeding spectrum of vendace (Coregonus albula L.) in Lake Pleshcheyevo. Inland Water Biol. 2019, 12, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloranta, A.P.; Kahilainen, K.K.; Amundsen, P.-A.; Knudsen, R.; Harrod, C.; Jones, R.I. Lake size and fish diversity determine resource use and trophic position of a top predator in high-latitude lakes. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, B.; Holopainen, T.; Amundsen, P.-A.; Eloranta, A.P.; Knudsen, R.; Præbel, K.; Kahilainen, K.K. Interactions between invading benthivorous fish and native whitefish in subarctic lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2013, 58, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezina, N.A.; Strelnikova, A.P.; Maximov, A.A. The benthos as the basis if vendace Coregonus albula and perch Perca fluviatilis diet in an oligotrophic sub-Arctic Lake. Polar Biol. 2018, 41, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezina, N.A.; Terentev, P.M.; Zubova, E.; Tsurikov, S.M.; Maximov, A.A.; Sharov, A.N. Seasonal diet changes and trophic links of cold-water fish (Coregonus albula) within a northern lake ecosystem. Animals 2024, 14, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, N.; Barlow, C.; Baumgartner, L.J.; Bretzel, J.B.; Doyle, K.E.; Duffy, D.; Price, A.; Vu, A.V. A global review of the biology and ecology of the European perch, Perca fluviatilis. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2025, 35, 587–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, P.-A.; Bøhn, T.; Popova, O.A.; Staldvik, F.J.; Reshetnikov, Y.S.; Kashulin, N.A.; Lukin, A.A. Ontogenetic niche shifts and resource partitioning in a subarctic piscivore fish guild. Hydrobiologia 2003, 497, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, D.H.; Selgeby, J.H.; Newman, R.M.; Henry, M.G. Diet and feeding periodicity of ruffe in the St. Louis River Estuary, Lake Superior. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1995, 124, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.E.; Maitland, P.S. The ruffe population of Loch Lomond, Scotland: Its introduction, population expansion, and interaction with native species. J. Great Lakes Res. 1998, 24, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E.; Greenberg, L.A. Competition between a planktivore, a benthivore, and a species with ontogenetic diet shifts. Ecology 1994, 75, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesonen, M.A.; Gorbach, V.V.; Shustov, Y.A. Feeding relationships between the common whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus) and the river perch (Perca fluviatilis) in a small forest lake. Princ. Ecol. 2017, 4, 37–45. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacioglu, O.; Zubrod, J.P.; Schulz, R.; Jones, J.I.; Pârvulescu, L. Two is better than one: Combining gut content and stable isotope analyses to infer trophic interactions between native and invasive species. Hydrobiologia 2019, 839, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, C.A.; Arrington, D.A.; Montaña, C.G.; Post, D.M. Can stable isotope ratios provide for community-wide measures of trophic structure? Ecology 2007, 88, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, M.; Mariash, H.; Forsström, L. Seasonal shifts between autochthonous and allochthonous carbon contributions to zooplankton diets in a subarctic lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011, 56, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B.J.; Fry, B. Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1987, 18, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimp, G.M.; Murphy, S.M.; Lewis, D.; Douglas, M.R.; Ambikapathi, R.; Van-Tull, L.A.; Gratton, C.; Denno, R.F. Predator hunting mode influences patterns of prey use from grazing and epigeic food webs. Oecologia 2013, 171, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terentyeva, I.A.; Kashulin, N.A.; Denisov, D.B. Assessment of the trophic status of the subarctic Lake Imandra. Bull. Murm. State Tech. Univ. 2017, 20, 197–204. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, E.J. Stomach contents analysis—A review of methods and their application. J. Fish Biol. 1980, 17, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M.; Layman, C.A.; Arrington, D.A. Getting to the fat of the matter: Models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 2007, 152, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, P.-A.; Gabler, H.-M.; Staldvik, F.J. A new approach to graphical analysis of feeding strategy from stomach content data—Modification of the Costello (1990) method. J. Fish Biol. 1996, 48, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipps, S.R.; Garvey, J.E. Assessment of diets and feeding patterns. In Analysis and Interpretation of Freshwater Fisheries Data; Guy, C.S., Brown, M.L., Eds.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 473–514. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, O.A.; Reshetnikov, Y.S. On complex indices in the study of fish nutrition. J. Ichthyol. 2011, 51, 712–717. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 2002, 83, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.L.; Sorell, J.M.; Laiz-Carrión, R.; Baro, I.; Uriarte, A.; Macías, D.; Medina, A. Stomach content and stable isotope analyses reveal resource partitioning between juvenile bluefin tuna and Atlantic bonito in Alboran (SW Mediterranean). Fish. Res. 2019, 215, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.; Blanchette, M.L.; Pusey, B.J.; Jardine, T.D.; Pearson, R.G. Gut content and stable isotope analyses provide complementary understanding of ontogenetic dietary shifts and trophic relationships among fishes in a tropical river. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 2156–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, K.L. Omnivory and stability in freshwater habitats: Does theory match reality? Freshw. Biol. 2017, 62, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, G.; Hildrew, A.G. Body-size determinants of niche overlap and intraguild predation within a complex food web. J. Animal Ecol. 2002, 71, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.M.; Dunne, J.; Woodward, G. Freshwater food webs: Towards a more fundamental understanding of biodiversity and community dynamics. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, A.M.; Tiunov, A.V.; Scheu, S.; Brose, U. Trophic position of consumers and size structure of food webs across aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Am. Nat. 2019, 194, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lee, G.H.; Arie Vonk, J.; Verdonschot, R.C.; Kraak, M.H.; Verdonschot, P.F.; Huisman, J. Eutrophication induces shifts in the trophic position of invertebrates in aquatic food webs. Ecology 2021, 102, e03275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liso, S.; Gjelland, K.Ø.; Reshetnikov, Y.S.; Amundsen, P.A. A planktivorous specialist turns rapacious: Piscivory in invading vendace Coregonus albula. J. Fish Biol. 2011, 78, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, J.; Krappe, M.; Koschel, R.; Waterstraat, A. Feeding of European cisco (Coregonus albula and C. lucinensis) on the glacial relict crustacean Mysis relicta in Lake Breiter Luzin (Germany). Limnologica 2008, 38, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljanen, M. Food and food selection of cisco (Coregonus albula L.) in a dysoligotrophic lake. Hydrobiologia 1983, 101, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøhn, T.; Amundsen, P.A. The competitive edge of an invading specialist. Ecology 2001, 82, 2150–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, P.A.; Knudsen, R.; Klemetsen, A.; Kristoffersen, R. Resource competition and interactive segregation between sympatric whitefish morphs. Ann. Zool. Fennici 2004, 41, 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.; Kim, W.-S.; Ji, C.W.; Kim, M.-S.; Kwak, I.-S. Application of combined analyses of stable isotopes and stomach contents for understanding ontogenetic niche shifts in silver croaker (Pennahia argentata). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, K.-A.; Koops, M.A.; Arts, M.T.; Sutton, T.M.; Power, M. Lake Whitefish Feeding habits and condition in Lake Michigan. Adv. Limnol. 2012, 63, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, V.B.; Kuzmenkin, D.V. The role of freshwater mollusks in feeding of humpback whitefish Coregonus lavaretus (Linnaeus) in Sorulukol Lake (Mountain Altai). J. Altai State Univ. 2013, 15, 76–79. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.L.; Lance, M.J.; Albertson, L.K.; Briggs, M.A.; Dutton, A.J.; Zale, A.V. Diet composition and resource overlap of sympatric native and introduced salmonids across neighboring streams during a peak discharge event. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shustov, Y.A.; Lesonen, M.A.; Gorbach, V.V. Food Competition between river perch and european whitefish in the water bodies of the Republic of Karelia. Hydrobiol. J. 2022, 58, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, J.; Persson, L.; Christensen, B. Growth, morphological variation and ontogenetic niche shifts in perch (Perca fluviatilis) in relation to resource availability. Oecologia 2000, 122, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terentjev, P.M.; Berezina, N.A. Ecological and morphological characteristics and feeding of perch (Perca fluviatilus) in the autumn–winter period in dystrophic and oligotrophic lakes of Northern Karelia (Russia). Inland Water Biol. 2022, 15, 916–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakana, H.; Huuskonen, H.; Karjalainen, J. Predation of perch on vendace larvae: Diet composition in an oligotrophic lake and digestion time of the larvae. J. Fish Biol. 2007, 70, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcıoğlu, O.; Yılmaz, S.; Yazıcı, R.; Erbaşaran, M.; Polat, N. Feeding ecology and prey selection of European perch Perca fluviatilis inhabiting a eutrophic lake in northern Turkey. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2016, 31, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolbunov, I.A.; Pavlov, D.D. Behavioral differences of various ecological groups of roach Rutilus rutilus and perch Perca fluviatilis. J. Ichthyol. 2006, 46, S213–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horppila, J.; Ruuhijärvi, J.; Rask, M.; Karppinen, C.; Nyberg, K.; Olin, M. Seasonal changes in the diets and relative abundances of perch and roach in the littoral and pelagic zones of a large lake. J. Fish Biol. 2000, 56, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, M.I.; Sushchik, N.N.; Glushchenko, L.A.; Zadelenov, V.A.; Rudchenko, A.E.; Dgebuadze, Y.Y. Fatty acid composition of fish species with different feeding habits from an Arctic Lake. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 474, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezsu, E.T.; Specziár, A. Ontogenetic diet profiles and size-dependent diet partitioning of ruffe Gymnocephalus cernuus, perch Perca fluviatilis and pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus in Lake Balaton. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2006, 15, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleuter, D.; Eckmann, R. Generalist versus specialist: The performances of perch and ruffe in a lake of low productivity. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2008, 17, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogorelec, Ž.; Straile, D.; Rudstam, L.G. Can young-of-the-year invasive fish keep up with young-of-the-year native fish? A comparison of feeding rates between invasive sticklebacks and whitefish. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).