Abstract

Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture, a cornerstone of China’s marine industry under the Rural Revitalization Strategy, contributes over 70% of national output but faces escalating marine disasters that expose systemic barriers to resilience. This study develops a diagnostic multidimensional framework for post-disaster resilience using a Grounded Theory design. We conducted 32 semi-structured interviews with participants from five key enterprises and cooperatives in the core Leizhou production region. Interview transcripts were analyzed in NVivo through open, axial, and selective coding with constant comparison. Open coding generated 136 initial concepts, axial coding consolidated them into 25 categories, and selective coding integrated these into four core dimensions: technological adaptation gaps, institutional trust deficits, human-resource succession ruptures, and ecological path dependence. These dimensions constitute the core phenomenon, termed the four-dimensional synergistic dilemma. Building on this empirically grounded diagnosis, we propose a multidimensional collaborative recovery framework that links each dimension to actionable levers, including stress-tolerant breeding and ecological aquaculture models, targeted policy instruments and adaptive insurance, industry-education pipelines to preserve craftsmanship, and spatial planning with coordinated pollution control. The study provides a theoretically informed and empirically validated model for enhancing industrial resilience, offering actionable insights for the sustainable revitalization of coastal specialty industries.

Keywords:

rural revitalization; industrial resilience; post-disaster recovery; Guangdong south-pearl; resilience theory; grounded theory Key Contribution:

Based on grounded theory, this study pioneers a multidimensional framework that diagnoses the synergistic barriers to post-disaster recovery in pearl aquaculture and proposes integrated pathways to transform resilience theory into actionable strategies for sustainable industry revitalization.

1. Introduction

The Rural Revitalization Strategy is a key national policy aimed at modernizing rural areas in China, focusing on enhancing economic, social, cultural, and ecological systems [1]. Within this framework, building resilience in rural industries has become a central objective. The theory of “Resilience” provides a robust analytical framework for understanding and addressing this challenge. Originally developed in ecology, resilience theory has evolved into a key perspective for studying social-ecological systems (SES), with two dominant paradigms: engineering resilience, focusing on return time to equilibrium after disturbance, and ecological resilience, emphasizing system persistence through adaptation and transformation in the face of change [2]. This perspective has been extended to complex adaptive systems (CAS), where resilience involves the capacity of systems to self-organize, learn, and maintain functions amid uncertainty [3]. In social-ecological system studies, it emphasizes a system’s capacity to maintain core functions when confronting external disturbances and to adapt and transform through learning and reorganization [4,5,6]. For the south-pearl aquaculture industry, resilience refers to its integrated capacity to withstand environmental and economic disruptions and to achieve sustainable recovery and transformation. Thus, the Rural Revitalization Strategy provides systematic institutional support for building industrial resilience through its top-level design, while the construction of such resilience constitutes both a practical implementation and an effectiveness measure of rural revitalization within the distinctive industry sector. This research is conceptually anchored at the intersection of these two theoretical frameworks.

Guangdong Province serves as the core production base for China’s seawater pearl (namely south-pearl) industry, demonstrating significant productive capacity and influence. As a nationally certified geographical indication product, Guangdong south-pearl functions as a dual vehicle for regional economic development and marine cultural heritage. Statistical data indicate that in 2024, seawater pearl aquaculture production in Guangdong province, China, accounted for over 79% of the national total [7], highlighting its dominant position in the industry. However, the industry’s sustainability faces severe threats from frequent marine disasters, including storm surges, waves, marine heatwaves, and harmful algal blooms, which pose substantial challenges to its industrial resilience. For instance, during the summer of 2019, persistently high temperatures over one month in Liusha Bay, China, resulted in pearl oyster mortality rates reaching 90% in the surrounding areas [8]. Furthermore, when Super Typhoon “Yagi” struck the Zhanjiang production area in 2024, field surveys, involving interviews with multiple production entities and cross-verified by the stationed research team at the National-Level Leizhou South-Pearl Science and Technology Backyard, indicated pearl oyster mortality rates approaching 40%. Traditional post-disaster recovery models confront systemic limitations in technological adaptability, policy coordination, human resource capacity, and ecological resilience. Consequently, establishing a scientifically grounded and coordinated mechanism for disaster prevention, mitigation, and post-disaster recovery to systematically enhance industrial resilience has become an urgent imperative for achieving the sustainable development of the south-pearl industry and fulfilling the strategic objectives of rural revitalization.

From a global perspective, the international community places significant importance on the pearl aquaculture industry, both for its economic significance to remote communities [9,10] and because its primary production zones are frequently affected by disasters, which has stimulated extensive research on industrial resilience and sustainable management [11]. However, much of this research applies resilience theory in a fragmented manner, often overlooking theoretical tensions between social and ecological dimensions, such as the incommensurability of system ontologies or the normative pitfalls of unifying frameworks [12]. Current research on disaster recovery in pearl cultivation demonstrates advancements across multiple dimensions. Technologically, research has advanced pearl cultivation techniques through optimization of oyster age [13], sex [14], and mantle tissue selection [15]. Concurrently, several new aquaculture varieties (lines) have been developed using conventional selective breeding, while genomic selection breeding has demonstrated potential for enhancing stress tolerance in pearl oysters [16]. However, advanced technology (e.g., gene editing) remains non-operational [17], and the application of intelligent aquaculture equipment for water quality monitoring and automated larval feeding remains underdeveloped. Institutional frameworks show varied approaches: Japan has systematically strengthened supply chain stability through legislation such as the Pearl Industry Promotion Act, the South Pacific’s cooperative shareholding mechanism facilitates fisher involvement in decision-making [9], Fiji’s community-based spat collection model provides sustainable livelihoods [10], and French Polynesia’s integrated risk governance framework offers reorganization paradigms for industry decline [18]. In contrast, China’s policy framework for the industry requires further refinement, particularly in establishing long-term mechanisms for risk diversification and ecological compensation. Regarding human resources, while initial efforts in knowledge transfer have been made by both industry and educational institutions, substantial deficiencies remain in training for intelligent equipment operation, cultivating high-skilled professionals, and modernizing the preservation of traditional craftsmanship. Ecologically, the pearl aquaculture industry faces escalating and compounding challenges. These range from persistent harmful algal blooms in Japanese waters and coastal pollution in the Leizhou Peninsula, China, to microplastic contamination in French Polynesia [19] and the metabolic dysfunctions in pearl oysters induced by increasing global marine heatwaves [20]. The very capacity for pearl formation hinges on delicate biological processes, as evidenced by the sequential and highly coordinated biomineralization mechanism of the outer shell layer in Pinctada margaritifera [21]. Compounding these issues, long-term monitoring reveals alarming trends of climate-driven stock depletion, as seen in French Polynesia, where natural pearl oyster densities plummeted by factors of 2.35 to 8.87 over a decade, with elevated temperatures identified as the primary suspect [22]. Population genomics further reveals that such environmental pressures can lead to significant genetic differentiation and reduced connectivity among pearl oyster stocks, threatening their long-term resilience [23]. These collective environmental stressors pose significant threats to the industry’s sustainable development. In this context, green development models like integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA)—which combines bivalves, macroalgae, and fish—show considerable application potential [24,25], as they contribute to optimizing aquaculture ecosystems and mitigating environmental pressures, such as nutrient loading. Collectively, these international examples conceptually validate that resilience challenges in pearl aquaculture are inherently multidimensional, spanning technology, institutions, human resources, and ecology.

While existing research provides valuable insights, it exhibits systematic inadequacies. Predominantly, studies focus on disaster impacts or conventional management through single-dimensional approaches (e.g., solely technological or policy perspectives), with macro-level methodologies lacking micro-scale empirical validation. This gap aligns with broader critiques in resilience literature, where social-ecological interactions are often oversimplified, and the multidimensional nature of resilience (e.g., as seen in CAS principles) is underexplored in practical contexts [3]. More critically, there is an absence of systematic analysis through the theoretical lens of industrial resilience concerning the synergistic and impeditive mechanisms among multidimensional factors in disaster recovery. Given the exploratory nature of investigating these complex interdependencies, a methodology capable of generating theory from empirical data was required. Therefore, to bridge this gap, this research utilizes multiple methods, including literature analysis, statistical data analysis, policy document analysis, and expert interviews, employing grounded theory as the primary methodology to conduct in-depth interviews and three-stage coding with south-pearl aquaculture enterprises and cooperatives in the Leizhou Peninsula core production region. The study aims to (1) systematically identify the core categories influencing disaster recovery through the lens of resilience theory, particularly focusing on adaptive and transformative capacities; (2) construct a four-dimensional analytical framework of “technology-institution-human resources-ecology” that reflects the complex adaptive nature of social-ecological systems; and (3) reveal the intrinsic logic through which these multiple challenges interweave to create systematic impediments at micro-practice levels. The principal conclusion points to a “four-dimensional synergistic dilemma” as the core barrier to recovery. Theoretically, this research develops a resilience analytical framework integrating macro-structures and micro-actions, thereby enriching the empirical foundation for rural industrial resilience studies. Practically, it proposes collaborative pathways encompassing stress-resistant breeding, dynamic insurance mechanisms, craftsman academies, and ecological aquaculture practices, while critically referencing international experiences to provide operational policy recommendations for effectively integrating Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture industry recovery with the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Accordingly, this study addresses the following research question: What are the core challenges and influencing factors affecting post-disaster recovery and resilience in Guangdong’s south-pearl aquaculture industry, and how do these factors interrelate to collectively shape the recovery process?

2. Research Design and Methodology: A Grounded Theory Approach

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Methodological Approach and Case Selection

To systematically elucidate the intricate mechanisms of post-disaster recovery in Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture and overcome the limitations of macro-statistical approaches, this study employs grounded theory as its primary qualitative research methodology. Grounded theory is particularly suited for theory development directly from empirical data and is especially adept at analyzing complex, systemic concepts like “industrial resilience,” which involve multifaceted interactions and underlying mechanisms. The post-disaster recovery process in south-pearl aquaculture entails complex interplay among technological, institutional, human, and ecological dimensions, making it an ideal context for grounded theory application. This approach facilitates the bottom-up construction of a theoretical framework that accurately reflects the practical challenges and inherent logic of resilience in this industry.

For case selection, this research adhered to the principle of theoretical sampling, identifying Liusha Bay, Zhanjiang, China, as the primary study area. This region represents both the historical birthplace and contemporary core production zone of south-pearl aquaculture. The farming entities in this area have accumulated substantial recovery experience through long-term adaptation to frequent disasters, including typhoons and heatwaves, while simultaneously exhibiting common industry challenges such as germplasm degradation, technological gaps, and marine pollution. Consequently, it provides an exemplary setting for observing and analyzing deficiencies in industrial resilience and their root causes. The study ultimately selected five enterprises and cooperatives as research samples through theoretical sampling. This sample size is consistent with common practice in in-depth qualitative studies aiming for theoretical saturation, where the priority is conceptual depth and diversity rather than statistical representativeness. The sampling criteria were designed to incorporate diverse perspectives across three key dimensions to ensure theoretical richness and variation: first, variation in operational scale, including large integrated enterprises, medium-sized cooperatives, and small household farms; second, coverage of essential industry chain segments, encompassing hatchery, cultivation, nucleus implantation, and processing; third, recent experience with significant disaster impacts, particularly typhoons and extreme temperatures. This approach ensured our data collection would yield insights into the core resilience challenges across the industry’s ecosystem. The key characteristics of the five selected cases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected enterprise and cooperative samples.

2.1.2. Data Collection

Data for this study were collected from both primary interview sources and secondary policy documents to enable methodological triangulation. Primary data were collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted by the research team in December 2024. A total of 32 interviews were completed with managers (including business owners and executives) and senior technical staff (such as hatchery operators, nucleus implanters, and tissue processors) from the five sample organizations, supplemented by interviews with domain experts in south-pearl aquaculture (See Table 2). All interviews followed the semi-structured protocol detailed in Appendix B, which was structured around key thematic dimensions: disaster impacts, recovery practices, encountered challenges (resilience gaps), and policy expectations. Each interview lasted between 30 and 60 min, ensuring comprehensive coverage of topics while maintaining participant engagement. All interviews were audio-recorded following informed consent (using the form provided in Appendix A), transcribed verbatim, and compiled into a comprehensive textual database comprising approximately 127,000 words.

Table 2.

Profile of interview participants (N = 32).

Secondary data were primarily utilized to supplement and verify interview findings, while also clarifying the institutional context of industry development. We systematically gathered policy documents relevant to the south-pearl industry issued by provincial, municipal, and county governments (as detailed in the subsequent Results section). These materials served to supplement and cross-validate the institutional context and resilience support environment referenced in interviews, thereby enhancing both the objectivity and depth of the subsequent four-dimensional analysis.

2.2. Data Coding and Category Refinement

2.2.1. Open Coding

Open coding involves the systematic process of breaking down, scrutinizing, comparing, and conceptualizing qualitative data. In this study, we conducted a line-by-line analysis of interview transcripts to extract initial concepts, which were subsequently developed into coherent categories. Using NVivo 15 software, the open coding process yielded 136 initial concepts and 25 initial categories. This analytical procedure effectively distilled the key empirical evidence constituting the core challenges to industrial resilience. Selected examples of this coding process are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Examples of open coding process.

2.2.2. Axial Coding

Axial coding aims to identify and establish logical relationships among categories. Through continuous comparative analysis of the 25 initial categories, we derived 9 sub-categories, which were subsequently refined into 4 core categories. These four core categories-technological adaptation gap, institutional trust deficiency, rupture in human resource inheritance community, and ecological dependency path lock-in-collectively constitute the four fundamental dimensions influencing industrial resilience. The results of the axial coding process are systematically presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of axial coding. This table illustrates the derivation of the four core dimensions from the initial categories, with each row representing a distinct pathway in the analytical process of axial coding.

2.2.3. Selective Coding

Selective coding aims to identify a core category from the principal categories and systematically establish its relationships with all other categories, thereby constructing an integrated theoretical framework through a compelling narrative. The core category emerging from this study is identified as the “Four-Dimensional Synergistic Dilemma: The Systemic Impediment to Post-Disaster Recovery.” This central narrative can be articulated as follows: The post-disaster recovery of Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture industry is fundamentally constrained by a four-dimensional synergistic dilemma comprising technological adaptation gaps, institutional trust deficiencies, disruption of the human resource inheritance community, and ecological dependency path lock-in. These four critical dimensions are intricately interconnected and mutually reinforcing, systematically undermining industrial resilience across technological, institutional, social, and ecological domains, ultimately resulting in structural deficiencies in recovery capacity. For instance, institutional trust deficiencies (manifested through insurance system failures) amplify disaster impacts and exacerbate the economic vulnerability of enterprises and cooperatives, leaving them financially incapable of investing in ecological restoration technologies and intelligent equipment. Concurrently, the breakdown in human resource inheritance communities creates a dissemination gap for advanced stress-resistant breeding technologies while diminishing cooperatives’ agency in marine spatial planning and governance. Furthermore, ecological dependency path lock-in, through progressively deteriorating farming environments, directly compromises the effectiveness of technological applications and workforce stability, thereby establishing a self-perpetuating vicious cycle that systematically impedes recovery efforts.

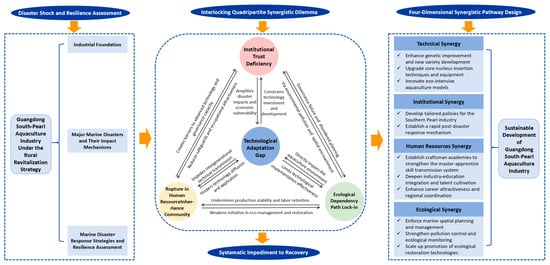

2.3. Theoretical Model Development: The Four-Dimensional Synergistic Dilemma Framework

Building upon this core narrative, we have developed the “Four-Dimensional Synergistic Dilemma” theoretical model to conceptualize post-disaster recovery challenges in Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture industry (Figure 1). This framework graphically illustrates the interlocking relationships among the four core categories and provides a coherent representation of how the industrial resilience system becomes trapped in recovery impediment due to its inherent multi-dimensional deficiencies. More importantly, our grounded theory analysis reveals that these four dimensions are not isolated but deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing, forming a synergistic dilemma where challenges in one dimension exacerbate problems in others.

Figure 1.

The theoretical model of the four-dimensional synergistic dilemma and the corresponding multidimensional synergistic recovery framework. The central dilemma was derived from the grounded theory analysis, visualizing the four interconnected core categories. The recovery framework was subsequently designed to provide integrated solutions addressing this specific dilemma. Arrows indicate the direction of influence or the logical flow between components.

This understanding of the four-dimensional synergistic dilemma establishes the foundational logic for designing the multidimensional collaborative recovery framework presented in Section 5. The framework’s construction was guided by two explicit design criteria: first, it must provide integrated solutions that simultaneously address all four dimensions of the dilemma, recognizing their interconnected nature; second, the formulation of specific recovery pathways must be guided by the core principles of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, ensuring practical relevance and policy alignment. The model effectively demonstrates how these dimensions interact to create systemic barriers that constrain the industry’s adaptive capacity and sustainable development.

2.4. Verification of Theoretical Saturation and Practical Applicability

To ensure the reliability and validity of this study, we conducted a systematic verification of theoretical saturation and coding consistency. Methodological literature indicates that data saturation in qualitative research typically occurs within 15–20 interviews [26,27,28,29]; our study substantially exceeded this benchmark with 32 interviews. Theoretical saturation was operationally defined as the point where analysis of new data yields no new concepts or categories, serving only to confirm, refine, or add variation to the properties of existing categories within the theoretical model. Our verification process was guided by this operational definition. The judgment was based on two primary indicators: (1) new interviews ceased to yield new initial concepts or categories, and only provided further confirmation and variation for existing ones; and (2) the relationships between categories in our theoretical model became stable and logically coherent.

To add rigor to this judgment, we implemented a multi-step verification procedure: We employed a “withheld data” method, reserving approximately 25% of the interview transcripts (8 interviews) from the initial coding and framework development phase. Analysis of this withheld dataset confirmed the absence of new concepts, providing objective evidence for saturation. Furthermore, to ensure the reliability of the coding structure, an inter-coder reliability check was performed. An independent researcher, unfamiliar with the emerging theory, coded a sample of transcripts (the same 8 interviews reserved for saturation testing). The coding achieved a high percentage agreement of 92% with the primary coding, indicating strong consistency. Additionally, domain experts were consulted to review the coding procedures, analytical outcomes, and theoretical framework, providing critical external validation. Based on this comprehensive process, we concluded that the “Four-Dimensional Synergistic Dilemma” model had reached theoretical saturation.

Beyond establishing theoretical saturation, we further addressed the practical applicability of our findings through three additional validation strategies: (1) Member checking-preliminary findings and interpretations were shared with selected interviewees to confirm their accuracy and resonance with practical experience; (2) Expert validation-domain experts reviewed the framework’s coherence with industry realities and provided critical insights throughout the research process; (3) Policy-practice alignment check—we systematically examined how the identified challenges and proposed solutions correspond to existing policy mechanisms and documented industry practices, ensuring the framework’s relevance to real-world contexts.

Through this rigorous grounded theory analysis, we have systematically identified and extracted four critical dimensions that constitute the core challenges-specifically, the resilience vulnerabilities-in the post-disaster recovery of Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture industry from micro-level empirical data. Furthermore, this investigation has elucidated the complex synergistic mechanisms through which these dimensions interact. The subsequent sections will build upon this theoretical framework to conduct an in-depth examination of the specific manifestations and underlying causal mechanisms associated with each of these four dimensions.

3. Results Part I: Disaster Impacts and Industrial Resilience Assessment

3.1. Industrial Foundation of Guangdong South-Pearl Aquaculture

3.1.1. Geographical Distribution and Cluster Characteristics

Guangdong Province serves as both the origin and primary production region for seawater pearl aquaculture in China. The industry is highly concentrated in the Leizhou Peninsula, forming a “one core, multiple points” spatial pattern centered around Liusha Village in Tandou Town of Leizhou City, with radiating extensions to Xuwen and Yangjiang, China. As aquaculture operations in Nan’ao and Daya Bay, China (eastern Guangdong), have diminished or relocated, this high degree of geographical concentration enhances efficiency through industrial chain collaboration but also significantly amplifies the impact intensity and recovery difficulty of regional disaster risks. Currently, pearl aquaculture in this maritime zone extends across several towns, including Tandou, Wushi, and Qishui. However, interview evidence indicates that this cluster lacks coordinated planning, and its potential risk-resilience efficiency remains untapped. Practitioners noted that “there are no specific sea zones for pearl farming here,” operations are “generally near the shore, not far out,” and are intermingled with fish and scallop farming “all mixed together” (a18, a19). This spatial disorder and polyculture directly corroborate the core category of “Disordered Marine Spatial Planning and Management” (A7) to be analyzed in depth later, serving as a key spatial manifestation of the industry’s systemic vulnerability.

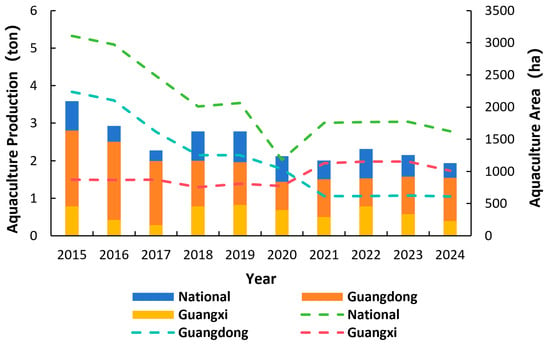

3.1.2. Production Scale and Output Volatility

The south-pearl aquaculture industry in Guangdong Province demonstrates notably fluctuating production characteristics. During 2015–2020, influenced by environmental regulations, disease outbreaks, and typhoon impacts, the provincial south-pearl production declined from 2.85 tons to 1.44 tons, with the aquaculture area contracting by nearly 50% (Figure 2). After 2020, propelled by policy support, the industry witnessed a recovery from its lowest point, with Zhanjiang’s south-pearl processing volume reaching 2.86 tons in 2023, constituting 85% of the provincial total. In 2024, Guangdong’s production reached approximately 1.54 tons, representing 81% of China’s total production, and has maintained a consistent share above 70% over the past decade, thus serving as a decisive pillar for national output. The severe volatility revealed by macro-statistics strongly interplays with the perceived industrial vulnerability expressed in interviews. The declining trajectory in production data is interpreted at the micro-level as the outcome of multiple resilience failures: high disaster-induced mortality was attributed to “deficient stress resistance of breeds” (a12, indicating the technological gap), while catastrophic losses were exacerbated by the “absence of insurance safeguards” (a91) and the “irreversible loss of biological assets” (a102, indicating institutional trust deficiency). Therefore, Figure 2 illustrates not merely output fluctuations but also a quantitative projection of the industry’s multidimensional vulnerabilities in technology, institutions, and beyond.

Figure 2.

Statistics on marine pearl cultivation production and cultivation area in National, Guangdong, and Guangxi, China from 2015 to 2024. Source: Data on aquaculture area and production compiled from the China Fisheries Statistical Yearbook (2016–2025 editions), National Bureau of Statistics.

3.1.3. Technological Status and Innovation Capacity

Guangdong holds 227 patents in pearl aquaculture (representing 23% of China’s total), significantly surpassing Guangxi’s 144 patents (Table 5). These patents span the entire production chain, including artificial breeding, nucleus implantation, pearl cultivation, and processing. However, this considerable advantage in “technological stock” starkly contradicts the “technology application gap” identified through grounded interviews. Respondents commonly pointed out a lack of smart equipment and the persistence of traditional methods in frontline production (a98), while many advanced technologies (e.g., gene editing) remain non-operational, and intelligent equipment applications are predominantly at the experimental stage. This reveals the core connotation of the “technological adaptation gap”: a significant disconnect between high R&D output and the accessibility and affordability for frontline production, especially for small- and medium-scale farmers.

Table 5.

Patent inquiries in the field of pearl aquaculture in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces.

In germplasm innovation, Guangdong has employed selective breeding and molecular marker-assisted breeding to develop nationally certified varieties of Pinctada fucata, including “Haixuan No. 1” and “Nanke No. 1” [8,30], supported by optimized artificial propagation techniques [31,32]. These advances directly respond to the “Deficiency in Stress-Resistant Germplasm Resources” (A5), a core challenge identified in our interview analysis. Nonetheless, interviewees still expressed the hope that “research on oyster breeds has been ongoing; better breeds would be ideal” (a15), suggesting a persisting gap between the stress-resistant performance of existing technologies and the compound environmental pressures faced by the industry. Innovations in production models (e.g., “relay culture across different geographic sites” [8]) and techniques (e.g., integrated preoperative protocols [33,34,35]), while providing solutions to enhance survival rates and efficiency, their widespread application is still constrained by the aforementioned cost and diffusion barriers. Consequently, the innovative potential reflected in patent data has not yet been fully translated into widespread technological capacity that underpins industrial resilience.

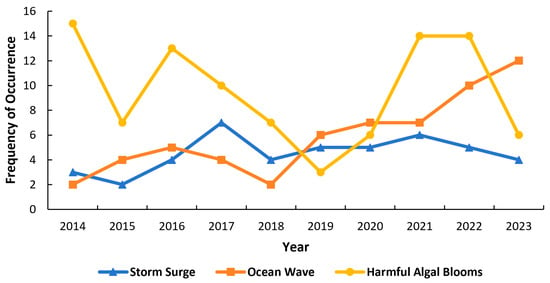

3.2. Principal Marine Disasters and Their Impact Mechanisms

Guangdong Province, adjacent to the South China Sea, is a region in China characterized by high frequency and severity of marine disasters. From 2014 to 2023, the region experienced 45 storm surges, 59 destructive wave events (with significant wave height ≥ 4.0 m), and 95 harmful algal blooms (see Figure 3), cumulatively resulting in substantial aquaculture losses. The high frequency of disaster events persistently challenges the buffering and absorption capacities of the south-pearl industry system. This study synthesizes mechanistic insights from the literature with empirical evidence from field interviews to analyze disaster impacts: statistical data reveal the macro-scale pressures, while interviews with frontline practitioners concretize how these pressures translate into industrial vulnerabilities. The disaster types most frequently reported by interviewees closely align with those documented in the literature, thereby supporting the systematic identification of impact pathways on pearl cultivation.

Figure 3.

Statistics on the occurrence frequency of major marine disasters in Guangdong Province from 2014 to 2023. Source: Data on the frequency of marine disaster occurrences compiled from the Guangdong Marine Disaster Bulletin, Department of Natural Resources of Guangdong Province.

Storm surges and destructive waves not only directly submerge facilities and damage installations but also indirectly harm pearl oysters by triggering ecological shocks, including substantial freshwater influx causing abrupt salinity drops, sediment resuspension increasing water turbidity, and fluctuations in water temperature and salinity inducing pronounced stress responses. Research demonstrates that post-typhoon, Pinctada fucata exhibits upregulated oxidative stress gene expression, diminished disease resistance, reduced growth rates, and even mass mortality [36]. This indicates that marine disasters inflict both immediate physical damage and chronic physiological stress on organisms, thereby continuously eroding ecological resilience. This dual “physical-physiological” assault is vividly captured in interview statements such as, “When a typhoon strikes, the ropes suspending pearl cages are broken, the cages sink to the seabed, and (the oysters) basically drown, resulting in very low survival rates. ” (a7).

Simultaneously, marine heatwaves constitute another significant threat. Although recurrent thermal exposure may enhance survival rates, this adaptation occurs at the expense of suppressed metabolic performance [20,37,38]. Summer water temperatures in Liusha Bay frequently exceed the optimal upper thermal limit of 30 °C for Pinctada fucata, confirming elevated temperature as a major stressor. This finding corroborates with field observations from interviews “When the weather is hot, the oysters die easily. During the high temperatures of April, May, and June, pearl spats cannot withstand the heat and die. “ (a11). Furthermore, pearl aquaculture persistently faces threats from harmful algal blooms, which induce aquatic hypoxia that impairs pearl oyster growth, compromises immune competence, and potentially causes mortality. Toxins from certain algal species can poison pearl oysters through trophic transfer, ultimately degrading pearl quality [39].

Notably, interviews expose a critical gap in the risk protection system for non-typhoon disasters: losses from events like high temperatures are often excluded, as they “didn’t meet the typhoon level (insurance coverage) ” (a96). Without tailored safeguards (e.g., high-temperature insurance), these ecological risks cannot be pooled, leaving practitioners to bear the full burden. This nexus between unmet ecological risks and institutional gaps exemplifies the interdependent reinforcement of dimensions that constitutes the study’s core “four-dimensional synergistic dilemma”.

3.3. Current Response Strategies and the Identified “Resilience Gap”

Under the Rural Revitalization Strategy, Guangdong has established a multidimensional policy system integrating scientific support, policy safeguards, and financial guidance (Table 6), providing relatively comprehensive institutional backing for industrial resilience at the policy document level. However, field surveys and interview data reveal a significant gap in the grassroots penetration and implementation efficacy of this system. For instance, respondents noted that losses due to high temperatures often receive no compensation because they “didn’t meet the typhoon level (insurance coverage)” (a96), reflecting a mismatch between policy protection and the actual risk profile of the industry. Concurrently, the subsidy distribution process is perceived as “cumbersome” with “uncertain outcomes” (a84, a112), and the belief that policy resources “all go to big companies” (a112) further undermines institutional credibility and incentive effects. These micro-level evidences indicate a persistent “resilience gap” between policy rhetoric and on-the-ground implementation. This gap manifests not only in insurance failures but also in technology adoption and financial accessibility, resulting in a long-term lag of the industry’s actual resilience behind the targets set in policy planning.

Table 6.

Policy toolkit for post-disaster recovery of Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture industry under the Rural Revitalization Strategy.

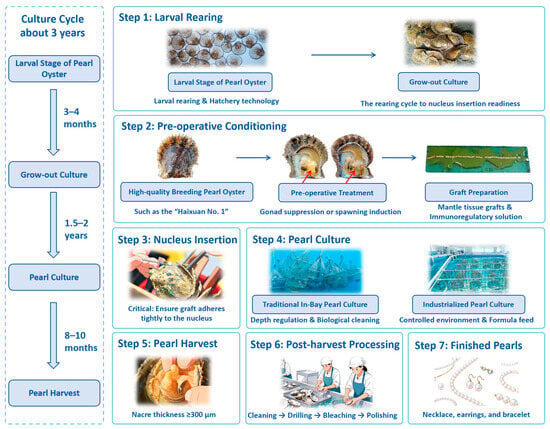

4. Results Part II: A Four-Dimensional Diagnostic Framework of Resilience Challenges

The cultivation of south-pearls involves a complex production cycle spanning approximately three years, encompassing multiple stages, including spat propagation, adult oyster rearing, nucleus implantation, pearl nurturing, harvesting, and processing, all requiring specific marine environmental conditions (see Figure 4). Initial investments in oyster spat and nucleus implantation constitute over two-thirds of the total production costs, making post-disaster recovery both financially demanding and time-consuming, with losses being largely irrecoverable. The concurrence of the critical nucleus implantation window (April–June) with the peak occurrence period of typhoons and elevated sea temperatures (July–September) substantially elevates operational risks and production costs, thereby exerting significant pressure on the industry’s sustainability. These inherent production characteristics necessitate a strong reliance on systemic resilience, yet the industry currently confronts multidimensional challenges in resilience capacity across various operational dimensions.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture process. The diagram was created by the authors using original photographs taken by the research team. The diagram represents an original synthesis of the production workflow based on field research and consultations with pearl aquaculture experts.

4.1. Vulnerabilities in Techno-Ecological Resilience: Adaptive Gaps and Lagging Stress-Tolerant Technologies

The grounded analysis in this study identifies the “technological adaptation gap” as the primary constraint on post-disaster recovery, fundamentally reflecting deficiencies in “techno-ecological resilience”—the industrial technological system’s inability to adapt to disaster conditions while maintaining core functionalities. This adaptation gap manifests most prominently across three critical dimensions: germplasm resources, core cultivation techniques, and intelligent equipment systems.

A primary challenge in germplasm development is the slow progress in breeding stress-tolerant varieties, primarily due to inadequate R&D investment. Although low-salinity-tolerant strains such as “Haixuan No. 1” and “Haixuan No. 2” have been developed, interview responses indicate persistent limitations in stress resistance, as evidenced by one participant’s observation: “Research on oyster breeds has been continuous; better breeds would be ideal—for instance, those with higher survival rates, heat tolerance, or lower disease incidence. Guangdong Ocean University has been consistently conducting breeding research.” (a16). The industry remains predominantly dependent on a single species, Pinctada fucata, characterized by limited genetic diversity and small broodstock size, which consequently yields pearls of modest diameter and commercial value. Current technical constraints limit nucleus implantation to only two nuclei per Pinctada fucata individual [40]. Furthermore, the inability to achieve breakthroughs in large-scale hatchery production of Pinctada maxima and Pinctada margaritifera, along with underdeveloped free-pearl cultivation techniques for Pteria penguin, continues to hinder the production of high-value, large-diameter pearls. While advanced technologies like CRISPR-based gene editing have seen preliminary laboratory application, the development and field implementation of cold-tolerant and heat-resistant varieties have progressed slowly.

Secondary challenges concern core cultivation processes, where both pearl yield and survival rates remain critically low at 40–45%. Significant technological barriers persist in several areas: the effective application of mantle tissue explants, the development of associated chemical treatments, and advanced anti-fouling culture cages. Additionally, the inability to monitor nucleus retention in implanted oysters during the cultivation period fundamentally undermines production stability.

Finally, the implementation gap in ecological sustainability principles is evident in technological applications. Despite policy support, the high costs of technological adoption prevent small- and medium-scale farmers from transitioning to smart aquaculture systems. This economic barrier impedes the widespread implementation of ecological farming models like Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA), while technologies, including automated feeding systems and real-time water quality monitoring, remain “predominantly at the experimental stage” [41,42]. As multiple interviewees emphasized, “We still lack relatively accurate early warning systems for these natural disasters” (a4, a5), revealing fundamental disparities between existing technological capabilities and the practical requirements of disaster management, thereby substantially compromising the industry’s preventive and restorative capacities.

This technological adaptation gap does not exist in isolation but actively erodes resilience in other dimensions. The high mortality rates and production instability directly lead to severe economic losses for enterprises and cooperatives. These losses, in turn, diminish their financial capacity to pay for insurance premiums, undermining the economic viability of risk-pooling mechanisms and exacerbating institutional trust deficiencies. Furthermore, the industry’s low and unstable returns, partly attributable to technological shortcomings, significantly reduce its occupational appeal, thereby accelerating the rupture in human resource inheritance. Finally, the lack of cost-effective, eco-friendly technologies (e.g., affordable IMTA systems) directly impedes the transition away from polluting practices, reinforcing the ecological path dependency.

4.2. Disconnect in Institutional Governance Resilience: Trust Deficits and Protection Gaps

Grounded theory analysis identifies deficient institutional trust as a fundamental barrier to post-disaster recovery, reflecting a disconnect in institutional governance resilience wherein policy and governance systems inadequately respond to disruptions and provide reliable protection.

Within the policy framework, the central problem lies in the inadequate implementation of effective governance principles, with policy designs mismatched to the long production cycles and high capital investment requirements characteristic of pearl farming. Current financial instruments, characterized by short repayment terms and inflexible collateral conditions, are ill-suited to the industry’s cash flow patterns. Interview responses consistently underscore these financial constraints, with participants noting that “initial investment costs are quite high” (a40) and “the oysters they raise cannot be monetized quickly” (a62). Business expansion is similarly hampered by capital constraints, as one manager explained: “The company cannot scale up entirely using this model, as it demands significant financial backing” (a51), while another emphasized that “every aspect of this operation requires capital investment” (a121). Policy support exhibits structural imbalances, disproportionately focused on downstream segments while providing insufficient backing for critical upstream activities such as germplasm research and eco-friendly farming practices. The absence of oyster-specific technical guidance following disasters, coupled with funding allocation cycles that significantly outlast the critical recovery period for pearl oysters, further diminishes policy efficacy. Post-disaster management predominantly depends on self-help measures, as described by one farmer: “After the typhoon, our immediate action is to locate and repair damaged infrastructure, such as broken wooden poles, and recover the oysters” (a100). The economic reality remains stark—“dead oysters represent total loss” (a102) and “dead shellfish have minimal economic value” (a103)—underscoring the crucial role of prompt recovery in mitigating losses. Furthermore, regional disparities in support create perceived policy support disparities (A22). Interviewees observed that “searching academic literature and documents online reveals greater focus on Guangxi and Pu pearls—their government prioritizes it more” (a78), noting that “Beihai established a dedicated south-pearl office” (a81) and is “committing billions to revitalize the south-pearl industry” (a82). In contrast, local stakeholders “perceive policy support as limited with few projects” (a87).

Regarding risk protection mechanisms, limited coverage range and high activation thresholds undermine the risk pooling function. Government-backed insurance products like “Deep-Water Cage Typhoon Index Insurance” only activate for typhoons above Force 10, failing to cover frequent risk factors, including harmful algal blooms, temperature extremes, and marine heatwaves. Farmer experiences demonstrate the disconnect between catastrophic losses and indemnification: one participant recounted how in 2019, “my oyster stock completely died, causing over 10 million RMB in losses. The insurance company coordinated and paid some compensation—just over one million, barely one-tenth of the actual loss” (a94). Another emphasized that “it wasn’t covered by the policy, as the mortality was caused by high temperatures, not meeting the typhoon criteria” (a96), resulting in the current situation where “there simply is no insurance available now” (a91). Despite substantial provincial government subsidy rates, regional disparities and co-payment requirements cause some farmers to forgo coverage, while complicated claims procedures further diminish enrollment incentives and trust in the insurance system.

The deficiency in institutional governance, particularly the failure of risk protection mechanisms, creates a cascading effect that locks the industry into a vulnerable state. Without reliable financial safeguards, disasters cause direct capital depletion, leaving firms without the funds to invest in stress-resistant germplasm, intelligent equipment, or ecological remediation technologies, thus perpetuating the technological adaptation gap. This financial precarity also depresses wages and job security, making it impossible to attract and retain a skilled workforce, which intensifies the human resource crisis. Moreover, the lack of compensation for losses reduces the economic incentive for farmers to adhere to spatial planning and environmental regulations, as short-term survival often trumps long-term sustainability, thereby worsening ecological spatial disorder.

4.3. Disruption of Community Human Resource Resilience: Succession Crisis and Industry-Education Misalignment

The disruption of community human resource resilience fundamentally threatens the sustainable development of Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture industry, evident in critical breakdowns in knowledge transmission and systemic failures in human capital reproduction.

Primary challenges emerge in technical knowledge succession, where field surveys at Liusha Bay reveal an aging workforce structure: nucleus implantation technicians average over 50 years old, with female workers constituting more than 70% of the workforce and youth participation remaining below 15%. These demographic patterns are corroborated by interview responses describing how “the current nucleus implanting staff are predominantly in their 50 s” (a27) and “most trained young workers cannot be retained” (a29). The specialized nature of nucleus implantation techniques demands extensive experiential knowledge, typically requiring 2–3 years to develop proficiency, yet systematic knowledge transfer mechanisms and financial incentives for master-apprentice relationships remain underdeveloped. Compounding these challenges, strong seasonal employment patterns (approximately six productive months annually), income instability, and limited working environments further diminish youth recruitment and retention. The training-retention disconnect presents particularly acute concerns. Enterprises report persistent difficulties in maintaining trained personnel, noting that “although technical training for nucleus implantation is conducted annually, retention remains challenging” (a25), with one representative case showing that “of eight trained tissue section workers, only one remained after achieving proficiency, while seven departed” (a30). These patterns reflect fundamental inefficiencies in human capital investment (A10) within the industry.

Furthermore, significant disconnects exist between talent development systems and industry requirements. Severe brain drain occurs as skilled workers frequently seek opportunities elsewhere, with interviewees observing that “once trained, workers secure jobs elsewhere and depart” (a26), typically finding “employment in urban centers like Zhanjiang or Guangzhou” (a31). This “training-induced outflow” phenomenon underscores the limited attractiveness of local industry careers. Academic programs demonstrate insufficient alignment with practical production needs, resulting in inadequate student competencies and professional identity development, while integrated education models combining theoretical and practical training achieve only limited implementation. In contrast, institutional models such as Zhejiang’s “China Pearl College” demonstrate superior coordination effectiveness, producing over 120 specialized graduates annually through its integrated “theory-enterprise practicum” approach.

Ultimately, systemic deficiencies in career appeal and reactive employment strategies (A12/A13) perpetuate these challenges. Non-competitive compensation structures—with daily wages of approximately 200 RMB generating monthly incomes around 6000 RMB even at full capacity—combined with perceived limitations in rural living standards directly drive workforce outflow. Interview responses highlight how workers compare “urban employment opportunities in Guangzhou” where “living conditions surpass local standards” (a32, a33), with regional development disparities exacerbating retention difficulties. In response, companies increasingly resort to reactive adaptation strategies targeting demographic groups with limited mobility, particularly “married women in their 30 s with children in local schools” (a34, a35), while implementing flexible daily wage systems (a37) and predominantly employing female workers (“females constitute 80–90% of the workforce,” a36). However, such employment models leveraging family commitments and flexible scheduling provide only temporary production stability, failing to address fundamental technical succession gaps in core processes. Compounding these challenges, multiple systemic factors reinforce the industry’s recruitment difficulties: seasonal work patterns, underdeveloped career progression pathways and certification systems, persistent perception of traditional farming as “low-skilled labor,” and significant risk exposure from frequent tropical storms combined with inadequate insurance protection. These elements collectively accentuate the industry’s characteristic challenges of “extended production cycles, high operational risks, and limited financial returns.” The comparative economics further exacerbate human resource scarcity—while fish (∼6 months) and scallops (7–8 months) offer shorter culture periods, pearl oysters demand minimum 12-month production cycles, driving some operators toward alternative species and thereby intensifying human capital constraints within pearl farming specifically.

The rupture in the human resource community acts as a critical bottleneck that stifles progress in other dimensions. The scarcity and aging of skilled technicians, such as nucleus implanters, create a dissemination barrier that slows down or prevents the adoption of new, stress-resistant breeding technologies, nullifying potential technological advances. A weakened and disengaged workforce also undermines the collective action needed for effective marine spatial governance and the adoption of best practices, thus sustaining ecological path dependency. Furthermore, the high costs and efforts associated with continuous training and high staff turnover consume capital that could otherwise be invested in technological upgrades or serve as a basis for insurance co-payments, indirectly sustaining institutional trust deficits.

4.4. Path Dependency in Ecological Spatial Resilience: Planning Disarray and Cumulative Pollution Effects

The path dependency in ecological spatial resilience constitutes a fundamental constraint to industry recovery, demonstrating both ecological function degradation in mariculture zones and spatial management disarray, indicating inadequate synergy between ecological sustainability and governance efficacy.

Primary concerns involve disordered marine spatial planning and extensive management practices. Despite clear delineation of prohibited, restricted, and permitted aquaculture zones in provincial and municipal planning documents, along with stipulated reductions in conventional cage and scallop farming, implementation remains inadequate, undermining the principle of “designated sea area for specific uses.” Interview data reveals that “the government provides no specific zoning for pearl cultivation versus scallop or fish farming” (a22), with “no dedicated marine areas... resulting in mixed cultivation of Pinctada fucata, scallops, and fish” (a18, a19), causing operational conflicts and mutual interference. Limited availability of “sheltered inner waters during risk periods” (a6) combined with “substantial maritime management costs” (a52) directly elevates production expenses. Widespread illegal occupation, unlicensed operations, and polyculture practices prevail, with core zones like Liusha Bay increasingly occupied by non-pearl species, diminishing suitable farming space, compromising water quality, and affecting production outputs. Regulatory designations of protected areas have substantially reduced traditional fishing grounds, with 189,000 hectares (11.63% of municipal waters) designated as restricted zones, while recent inclusions of pearl farming areas in Leizhou Bay into coral reef protection areas have further diminished available maritime space.

Furthermore, ecological consequences of past disaster events continue to manifest. Interviewees recount how “previous typhoons devastated pearl farming infrastructure” (a54) and “destroyed essential equipment during recent extreme events” (a99), with permanent stock losses (“dead oysters are irrecoverable,” a102) creating persistent vulnerabilities in production systems and ecological support functions (A20).

Additionally, compounding effects emerge from integrated aquaculture and industrial pollution. Nutrient enrichment from intensive fish farming, combined with industrial effluent from coastal installations, including Zhanjiang Donghai Island, creates persistent water quality challenges in key zones like Zhanjiang Port and Leizhou Bay, as documented in the 2024 Zhanjiang Ecological Environment Quality Report. Combined pollution sources expose core production zones to elevated ecological risks, jeopardizing oyster health and production outcomes.

Ultimately, adoption of ecological remediation technologies remains limited. Despite proposed integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) approaches, implementation barriers, including standardization challenges, cost constraints, and adoption resistance, prevent widespread application, maintaining conventional monoculture dominance. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where disasters exacerbate pollution, triggering secondary impacts, thereby locking ecological spatial resilience into vulnerable pathways and constraining the industry’s adaptive capacity.

The degraded and disordered ecological space directly undermines the effectiveness of interventions in all other dimensions. Pollution and spatial conflicts increase the physiological stress on oysters, rendering them more susceptible to diseases and extreme weather, which diminishes the practical effectiveness of existing stress-resistant germplasm and widens the technological adaptation gap. Frequent disasters in a degraded environment lead to more frequent and severe losses, which strain and expose the inadequacies of insurance schemes, further depleting institutional trust. Perhaps most critically, a polluted and high-risk working environment significantly diminishes the quality of life and perceived career prospects, making it profoundly difficult to attract a new generation of skilled workers, thereby cementing the human resource crisis.

5. Discussion: Toward a Multidimensional Collaborative Recovery Framework Through the Lens of Rural Revitalization

This section presents a multidimensional collaborative framework derived directly from the “four-dimensional synergistic dilemma”. The framework is designed to address the interconnected nature of the dilemma while aligning its pathways with the overarching objectives of the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Our analysis, grounded in the preceding empirical findings, indicates that an integrated approach is necessary. International evidence further underscores that singular solutions are often inadequate against systemic threats [22,43]. Consequently, the following pathways are formulated as targeted interventions to mitigate the specific resilience gaps—technological, institutional, human, and ecological—identified in this study.

5.1. Rebuilding Techno-Ecological Resilience: Developing Stress-Tolerant Varieties and Advancing Ecological Models

This pathway addresses the core categories of the “technological adaptation gap” and “ecological dependency path lock-in” by targeting their specific manifestations. First, to tackle the “Deficiency in Stress-Resistant Germplasm Resources” (A5) and the persistent desire for better breeds (a16), germplasm innovation must prioritize bridging the gap between R&D and application. This involves leveraging advanced genetic techniques [44] and accelerating the commercialization and dissemination of stress-tolerant varieties through platforms like the Leizhou Liusha Bay Pearl Industrial Park, directly confronting the “technology application gap” identified by farmers (a98).

Second, to ameliorate low survival rates linked to the “Limitations of Disaster Coping Strategies” (A1), core process innovation is required, focusing on standardizing and improving techniques like nucleus implantation. This includes refining and standardizing nucleus implantation techniques and developing automated systems and innovative anti-fouling cages to enhance production stability, quality, and efficiency.

Finally, to counter the trend of “Persistent Deterioration of Farming Environment Quality” (A9), ecological transition should prioritize models like Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). Such models can improve water quality, while their supporting infrastructure (e.g., large floating platforms, storm-resistant deep-water cages) directly enhances physical disaster resilience. A key to implementation is policy and financial support to lower adoption barriers for small- and medium-scale farmers, which directly addresses the cost-related obstacle at the heart of the “technological adaptation gap.” Supporting real-time environmental monitoring and AI-driven management systems can provide the precise information needed for these technological applications.

5.2. Consolidating Institutional Governance Resilience

This pathway confronts the core issue of “institutional trust deficiency,” aiming to rebuild institutional credibility and responsiveness through policies tailored to industry characteristics and redesigned risk-sharing mechanisms. First, responding to the industry’s long production cycles, high capital intensity, and the financing constraints voiced by interviewees (“initial investment costs are quite high,” a40; “everything...requires investment,” a121), customized policy instruments are required (see Table 7). These should include dedicated funding mechanisms for upstream activities like germplasm R&D and financial products with durations matching production cycles, accepting flexible collateral. Second, the redesign of the risk protection framework is a necessary response to the “Absence of Historical Experience and Current Insurance Safeguards” (A23). Addressing the problems of narrow coverage (a96) and inadequate compensation (a94) revealed in interviews, a “comprehensive pearl farming insurance” product should be developed. This involves incorporating frequent risk factors like high temperatures and algal blooms into coverage and developing parametric insurance products based on meteorological-oceanic indices to improve settlement objectivity and efficiency. Multi-level government co-financing of premiums can help establish an effective risk-pooling safety net, thereby stabilizing business expectations and reinforcing economic resilience.

Table 7.

Secondary policies for post-disaster recovery of Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture under rural revitalization.

5.3. Restoring Community Human Resource Resilience: Craftsman Skill Transmission and Enhanced Industry-Education Integration

Evidence from South Pacific nations suggests pearl farming can support multi-tiered livelihoods and community stability [6]. This pathway addresses the critical challenges of the “Rupture in Human Resource Inheritance Community”, specifically the “Risk of Discontinuity in Technical Knowledge Transmission” (A11), “Severe Aging of Core Technical Staff” (a27), and difficulty in replenishing young technicians (a29). The focus is on reconstructing skill transmission systems to secure essential human capital.

First, to counter the high attrition rate after training (a30) and the reliance on master-apprentice experience (a74), institutionalizing skill transfer is key. Establishing a “South-Pearl Craftsman Academy” within industrial parks, employing a combined theoretical-practical mentorship model supported by stipends, could help standardize techniques (e.g., nucleus implantation) and create a sustainable pipeline for skilled workers.

Second, mitigating the “Inefficiency in Human Capital Investment” (A10) and “Brain Drain” (a31) requires enhanced industry-education alignment. Partnerships between universities and industrial parks to offer specialized programs and “joint training” models are potential avenues to bridge the gap between training outcomes and industry needs, thereby improving the return on human capital investment.

Finally, improving the “Weak Overall Occupational Appeal” (A12) is fundamental for attracting and retaining talent. This could involve enhancing the social recognition and professional pride associated with pearl craftsmanship through cultural branding, alongside improving job security. Developing financial instruments like weather index insurance to cover technicians’ disaster-induced income interruptions could mitigate a key source of livelihood instability (a32, a34), addressing one aspect of the industry’s perceived risk and low attractiveness.

5.4. Strengthening Ecological Spatial Resilience: Integrated Spatial Planning and Pollution Governance

Global ESG assessment frameworks highlight the importance of integrated management for resilience [11]. This pathway tackles the intertwined issues of “Disordered Marine Spatial Planning and Management” (A7) and “Persistent Deterioration of Farming Environment Quality” (A9), aiming to shift the ecosystem away from its vulnerable trajectory.

First, to address the noted lack of marine functional zoning and spatial conflicts (a18, a19, a22), enhanced and enforced maritime spatial planning is critical. Based on existing provincial and municipal plans, this involves strict enforcement against illegal operations and unregulated polyculture in key zones like Liusha Bay. Establishing special protection regimes and resolving conflicts with prohibited zones through mechanisms like ecological compensation funds are necessary steps toward realizing “designated sea areas for specific uses”. Second, countering compound pollution from integrated aquaculture and industrial sources requires advancing integrated pollution control. This entails enforcing stricter standards for adjacent industries, enhancing discharge monitoring, and promoting clean production technologies among farming operations to control pollutant inputs at the source. Finally, breaking the “Ecological Dependency Path Lock-in” requires accelerating the adoption of ecological restoration technologies. Establishing demonstration sites for models like Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA), supported by financial and technical packages, can lower transition barriers. Integrating ecological engineering (e.g., artificial reefs) can further enhance habitat stability and recovery capacity, facilitating a shift toward more sustainable and resilient systems.

6. Conclusions

This grounded theory study, analyzing in-depth interviews with Guangdong south-pearl aquaculture stakeholders and contextualizing the findings within macro-statistical trends (e.g., output volatility, disaster frequency, patent counts), reveals that post-disaster recovery is critically constrained by four interconnected resilience challenges: technological, institutional, human, and ecological. These challenges constitute fundamental system vulnerabilities, manifesting as deficient techno-ecological capacity, fragmented institutional governance, disrupted human resource continuity, and path-dependent ecological spatial constraints. The interplay of these vulnerabilities reflects a core tension in resilience thinking [2] and exemplifies the complex adaptive nature of the social-ecological system, where nonlinear interactions produce emergent recovery challenges [3].

Comparative analysis with international cases further validates the multidimensional and systemic nature of these resilience challenges. For instance, the post-cyclone introduction of commercial shrimp aquaculture in Odisha, India [45], echoes how institutional trust deficits can exacerbate vulnerability, as observed in Guangdong. Similarly, the application of the Pressure and Release (PAR) model in Caribbean fisheries [46] parallels the institutional and human-resource challenges identified here. The emphasis on local leadership and community reorganization in Kesennuma Bay, Japan [47], underscores the critical role of human capital and collective action highlighted in our findings. Meanwhile, the integrated environmental and social safeguards proposed for bivalve aquaculture under marine heatwaves [48] support the necessity of techno-ecological and institutional integration advocated in this framework. These cross-case comparisons not only affirm the multidimensional character of resilience challenges but also accentuate the uniqueness of Guangdong’s context—where the national Rural Revitalization Strategy intersects with localized industrial path dependencies.

Grounding the discussion in the empirical logic of the “four-dimensional synergistic dilemma”, this study proposes an integrated recovery framework that translates core rural revitalization principles into targeted interventions addressing the identified resilience gaps. The framework is a direct response to the specific dilemma: stress-resistant breeding tackles the technological adaptation gap (A5); customized insurance instruments address the absence of institutional safeguards (A23); craftsman-academy models aim to repair the rupture in human-resource inheritance (A11); and enhanced spatial planning and pollution governance seek to break the ecological path dependency (A7, A9). Theoretically, the research contributes an integrated “rural revitalization–industrial resilience” analytical framework, illustrating how macro-level strategy micro-levelly shapes local industry resilience and adding empirical depth to social-ecological systems research by foregrounding the centrality of adaptability [4]. For policy, the findings indicate that transitioning from short-term recovery to sustainable resilience building requires institutional designs tailored to documented vulnerabilities, refined marine spatial legislation, and innovative human-capital mechanisms.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The findings are based on a specific regional context and a limited number of case studies, which may affect their generalizability to other regions. Potential biases, such as recall bias in interviews and reliance on self-reported data, should be considered, alongside operational challenges encountered in verifying some stakeholder claims. While this qualitative grounded theory study provides deep conceptual insights, the practical applicability of the proposed framework requires further empirical validation. Future research should therefore expand the geographical scope to enable cross-regional comparisons—specifically, comparative studies with other pearl-producing regions (e.g., French Polynesia, Japan, or Fiji) and broader aquaculture systems (e.g., shrimp, bivalves) facing similar climate challenges would help elucidate context-specific versus universal resilience factors—and employ longitudinal designs to track resilience over time. Integrating mixed-methods approaches, including quantitative measures to statistically validate the relationships between the four dimensions and resilience indicators, would be particularly valuable. Further exploration of context-specific trade-offs and synergies between different resilience paradigms would also help refine the framework’s application across diverse settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z., Q.W. and J.D.; Methodology, T.Z. and J.D.; Validation, T.Z., R.X. and J.D.; Formal analysis, T.Z. and J.D.; Investigation, T.Z., R.X. and Y.L.; Resources, Q.W. and J.D.; Data curation, T.Z., R.X. and Y.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, T.Z., R.X. and Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, T.Z., Q.W. and J.D.; Visualization, R.X., Q.W. and T.Z.; Supervision, Q.W. and J.D.; Project administration, Q.W. and J.D.; Funding acquisition, Q.W. and J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shellfish and Algae Industry Innovation Team of Guangdong Modern Agricultural Technology System (2024CXTD23), Research on Breeding Technology of Candidate Species for Guangdong Modern Marine Ranching (2025-MRB-00-001), National Shellfish Industry Technology System (CARS-49), and the Major Project of the National Social Science Fund of China (22&ZD126).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not available.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interview participants in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original interview data are not publicly available to protect participant confidentiality. Supporting anonymized data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the managers and technicians from the pearl aquaculture enterprises and cooperatives in Zhanjiang who generously shared their time and insights for this research. We also thank the domain experts who provided valuable comments during the interview design and data analysis phases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. (Redacted Version)

Interview Informed Consent Form (Sample)

Dear Mr./Ms. ________________:

We are a research team from the College of Fisheries and the School of Management at Guangdong Ocean University, working on the project “Post-Disaster Recovery of Guangdong South-Pearl Aquaculture”. To gain an in-depth understanding of the recovery status of Guangdong’s south-pearl aquaculture industry following disasters such as typhoons, harmful algal blooms, and heatwaves, we sincerely invite you to participate in this academic interview. Your extensive industry experience will provide valuable insights for this research, which is of great significance for promoting the sustainable development of the industry.

This study will strictly adhere to academic ethical standards. It will be conducted anonymously, and all interview content will be used solely for academic research. We commit to maintaining strict confidentiality of your personal information and the discussion content.

- Research Content

This research primarily explores the response measures, recovery processes, and challenges faced by Guangdong’s south-pearl aquaculture industry following disaster impacts, aiming to provide a reference for industrial policy formulation.

- 2.

- Participation Details

The interview will last approximately 30–60 min, with the exact duration adjustable according to your schedule.

The interview process will be audio-recorded and later transcribed into text.

All data will be anonymized to ensure the security of your privacy.

- 3.

- Potential Impacts

Discussing disaster experiences may cause discomfort. You have the right to skip any questions at any time.

Your participation will provide crucial practical references for our study and contribute to promoting the sustainable development of the industry.

- 4.

- Your Rights

Participation is entirely voluntary, and you have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Your personal information will be strictly protected.

- 5.

- Data Use Authorization

I confirm that I understand and agree: The research team may use the anonymized data from this interview for academic research and related publications.

- 6.

- Consent Confirmation

I have fully understood the above information and voluntarily agree to participate in this study.

___________________________ ___________________________

Participant Signature Date: Year Month Day

___________________________ ___________________________

Researcher Signature Date: Year Month Day

Research Team Contact: [Redacted for publication]

Telephone: [Redacted for publication]

Email: [Redacted for publication]

We sincerely thank you for your support and participation!

[Note: The original form included here contained the institutional contact information of the research team for participants. This has been redacted for publication to protect privacy. The full version was used in the field.]

Appendix B

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- What specific disaster events has your operation experienced in recent years, and what were the immediate impacts?

- What were your most critical response measures following these disasters?

- How has the recovery process progressed over time, and what factors influenced this progression?

- What have been the most significant challenges throughout the response and recovery phases?

- What types of support were most and least effective in facilitating recovery?

- Based on your experiences, what should be prioritized to improve future disaster resilience?

References

- Kuang, Y.P.; Peng, Y.; Li, S.S. The Multiple Logics, Basic Characteristics, and Realization Paths of China’s Agricultural and Rural Modernization in the New Era. Chin. Rur. Econ. 2024, 40, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakos, V.; Kéfi, S. Ecological resilience: What to measure and how. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 043003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, R.; Biggs, R.; De Vos, A.; Folke, C. Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: Organizing principles for advancing research methods and approaches. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience (Republished). Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Dong, Y.X.; Liu, Z.H. A review of social-ecological system resilience: Mechanism, assessment and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisheries and Fishery Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; National Fisheries Technology Extension Center; China Society of Fisheries. China Fishery Statistical Yearbook 2025; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2025; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, L.H.; Yao, Z.H.; Liao, Y.S.; Deng, Y.W.; Wang, Q.H. Comparison of production traits between the black shell color breeding line F5 and the control population of Pinctada fucata martensii. J. Fish. Sci. China 2023, 30, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, W.; Hine, D.; Southgate, P.C. Overview of the Development and Modern Landscape of Marine Pearl Culture in the South Pacific. J. Shellfish Res. 2019, 38, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.; Kishore, P.; Vuibeqa, G.B.; Hine, D.; Southgate, P.C. Economic assessment of community-based pearl oyster spat collection and mabé pearl production in the western Pacific. Aquaculture 2020, 514, 734505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleway, H. An Environmental, Social, and Governance Assessment of Marine Pearl Farming. Gems Gemol. 2023, 59, 404–405. [Google Scholar]