Abstract

Traditional morphometric analysis of Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea) relies heavily on manual dissection, which is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and prone to subjectivity. To address these limitations, we propose an automated quantitative approach based on deep-learning–driven instance segmentation. A dataset comprising 160 X-ray images of L. crocea was established, encompassing five anatomical categories: whole fish, air bladder, spine, eyes, and otoliths. Building upon the baseline YOLOv11-Seg model, we integrated a lightweight Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to construct an improved YOLOv11-CBAM network, thereby enhancing segmentation accuracy for complex backgrounds and fine-grained targets. Experimental results demonstrated that the modified model achieved superior performance in both mAP50 and mAP50–95 compared with the baseline, with particularly notable improvements in the segmentation of small-scale structures such as the air bladder and spine. By introducing coin-based calibration, pixel counts were converted into absolute areas and relative proportions. The measured area ratios of the air bladder, otoliths, eyes, and spine were 7.72%, 0.59%, 2.20%, and 8.48%, respectively, with standard deviations remaining within acceptable ranges, thus validating the robustness of the proposed method. Collectively, this study establishes a standardized, efficient, and non-destructive workflow for X-ray image-based morphometric analysis, providing practical applications for aquaculture management, germplasm conservation, and fundamental biological research.

Keywords:

Larimichthys crocea; X-ray imaging; YOLOv11; CBAM attention mechanism; morphometric analysis Key Contribution:

This study establishes a standardized, non-destructive workflow for quantitative morphometric analysis of Larimichthys crocea using an improved YOLOv11-CBAM instance segmentation model applied to X-ray images. The proposed approach achieves accurate automated segmentation of five key anatomical structures and converts pixel counts into biologically meaningful area ratios, providing practical phenotypic indicators for aquaculture management and germplasm evaluation.

1. Introduction

Larimichthys crocea is one of the most economically important marine aquaculture species in China, supported by well-established breeding, farming, and processing industries in coastal regions such as Fujian and Zhejiang [1,2]. Morphometric traits—particularly those of the air bladder, skeletal system, and sensory organs—are essential indicators for evaluating growth performance, health status, and germplasm quality in L. crocea [3]. However, conventional morphometric approaches still rely heavily on manual dissection and contact-based measurements, which are destructive, time-consuming, and susceptible to operator bias [4,5,6]. These limitations highlight the need for standardized, non-destructive, and high-throughput phenotyping methods in modern fisheries.

X-ray radiography provides a rapid, non-invasive means to visualize skeletal and visceral structures of fish with high contrast and minimal sample preparation [7,8,9]. Despite its advantages, most existing X-ray–based analyses require manual region identification or rely on coarse object-detection techniques [10,11], preventing accurate quantification of fine structures such as the air bladder, vertebrae, and otoliths. Furthermore, current workflows lack standardized procedures to convert pixel-based segmentation masks into biologically meaningful measurements, resulting in limited reproducibility across imaging conditions.

Recent advances in deep learning, particularly instance segmentation, offer a promising solution for automated morphological analysis. Models such as Mask R-CNN and YOLOv5/YOLOv8-Seg have been applied in aquaculture-related tasks, including fish detection, measurement, and behavior monitoring [12,13,14,15]. However, their application to internal-structure segmentation in X-ray images remains limited, and several methodological gaps persist: Absence of an end-to-end segmentation framework capable of simultaneously extracting multiple anatomical structures from fish X-ray images; Lack of standardized area-calibration procedures to convert pixel counts into real morphological metrics applicable across imaging sessions; Insufficient performance of prior YOLOv5/YOLOv8 models when dealing with low-contrast, small, and fine-grained targets such as otoliths, vertebral edges, or air bladder boundaries.

To address these limitations, the present study employs YOLOv11, the latest generation of the YOLO series. Compared with earlier versions, YOLOv11 introduces stronger multi-scale feature extraction, a decoupled head structure for improved localization, and an enhanced segmentation branch capable of producing more accurate instance masks. These features offer clear advantages for X-ray image analysis, where subtle contrast differences and fine structural details are common. To further improve small-object recognition and suppress background interference, we integrate the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [16] into the YOLOv11 architecture, enabling adaptive recalibration of both channel-wise and spatial features.

In this study, we make three primary contributions: We present the first YOLOv11-CBAM–based instance segmentation framework applied to fish X-ray morphometrics, enabling automated delineation of five anatomical structures in L. crocea: whole body, air bladder, spine, eyes, and otoliths. We construct a new annotated X-ray dataset comprising 160 images with fine-grained labels for these internal structures. We propose a coin-based calibration pipeline for converting pixel areas into absolute and relative morphological metrics, establishing a standardized, non-destructive workflow for quantitative phenotyping.

These advancements provide a robust and reproducible platform for large-scale morphometric analysis of L. crocea, offering valuable tools for aquaculture management, germplasm evaluation, and functional morphological research. This work should be viewed as a methodological validation rather than a comprehensive biological survey. Our aim is to establish a standardized, non-destructive, and automated pipeline for internal morphometric analysis using X-ray images and to evaluate its performance under practical aquaculture imaging conditions. The biological interpretations of anatomical ratios are therefore preliminary, while the methodological framework provides the foundation for future large-scale phenotyping studies. While the proposed workflow demonstrates promising performance, this study should be regarded as a proof-of-concept investigation conducted under specific experimental conditions. The conclusions drawn here reflect the characteristics of the present dataset and imaging setup and should not be generalized to broader aquaculture applications without further external validation across devices, environments, and species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

The experimental specimens were obtained from cage-cultured Large Yellow Croaker at Jinyu North, Shacheng Harbor, Fuding City, Fujian Province (100 m offshore), provided by the Fuding Research Base of the East China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (Figure 1). All fish were harvested from the farming site and transported to the laboratory by designated personnel under low-temperature conditions using ice packs. The samples were sealed in plastic bags, stored in a frozen state, and packaged in foam boxes, with 20 individuals per box.

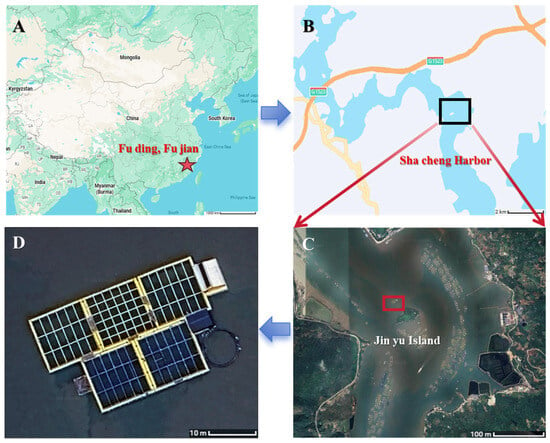

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the experimental site. (A) Map of China showing the location of Fuding, Fujian Province. (B) Map of Shacheng Harbor indicating the aquaculture area. (C) Satellite view of Jinyu Island with the location of the cage culture site highlighted. (D) Photograph of cage-culture facilities for Large Yellow Croaker Experimental specimens were obtained from cage-cultured L. crocea at Jinyu North, Shacheng Harbor, Fuding City, Fujian Province (100 m offshore).

2.2. Manual Measurements

In this study, manual morphometric measurements were obtained to document the external body characteristics of each specimen. Ten L. crocea individuals were measured for body length, total length, body height, body thickness, and body weight (Table 1) using a calibrated ichthyometer and vernier calipers. These measurements describe the overall body size of the sampled fish and provide contextual information for interpreting variation within the X-ray dataset.

Table 1.

Manual morphometric measurements of ten L. crocea specimens.

Manual measurements, however, are restricted to external linear traits and cannot capture internal anatomical structures such as the air bladder, otoliths, or spine. Validating internal morphometric features would require dissection, which inevitably alters tissue shape, disrupts natural spatial configuration, and produces deformation due to collapse, dehydration, or mechanical handling. Under such conditions, dissected organs cannot be considered comparable to their intact morphology observed in X-ray images.

For these reasons, manual measurements cannot serve as ground-truth references for internal structures. Destructive sampling was not conducted in this study. Instead, the evaluation of internal organ extraction relies on the consistency of the X-ray imaging process, the stability of the instance-segmentation workflow, and the reproducibility of measurements across individuals. This approach avoids structural distortion and ensures reliable quantification of internal morphometric traits.

2.3. Data Acquisition

The X-ray imaging system used for Large Yellow Croaker consisted of a closed white chamber (model XDR-AZ350 (Anzhu Photoelectric Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); Figure 2) with dimensions of approximately 1350 × 800 × 710 mm. The digital imaging field of view was 350 × 430 mm, with a pixel pitch of 140 μm and an adjustable object-to-detector distance of 300–800 mm. Additional specifications included an A/D conversion depth of 16 bits and a spatial resolution of 3.6 LP/mm. This system is widely applied in product defect detection and was adapted here for biological imaging. To increase data diversity and improve model training performance, multiple postures were captured for each fish, resulting in a total of 160 X-ray images.

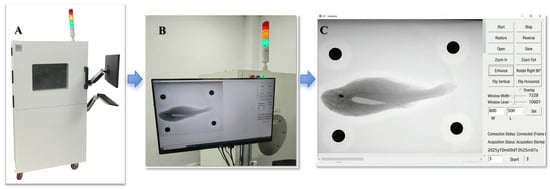

Figure 2.

X-ray imaging system and acquisition interface used for Large Yellow Croaker (A) External view of the X-ray imaging system equipped with a monitor and keyboard for real-time control. (B) Display interface showing the captured X-ray projection of the specimen during operation. (C) Representative X-ray image of Large Yellow Croaker obtained by the system, clearly showing internal skeletal and swim bladder structures. Blue arrows indicate the sequential workflow from image acquisition to visualization.

2.4. Dataset Construction

Using the X-ray imaging system (Figure 3A), approximately 160 images of Large Yellow Croaker were acquired. After excluding invalid data, representative images from different orientations were selected, and the relevant regions of interest were extracted for further annotation. Five anatomical categories were defined as prediction targets: whole fish, air bladder, spine, eyes, and otoliths. Manual segmentation and labeling of these regions were performed using the open-source platforms Roboflow (https://roboflow.com, assessed on 15 September 2025) and CVAT V2.37.0 (Computer Vision Annotation Tool), with annotated examples shown in Figure 3B. To ensure annotation consistency and minimize human bias, all labeling was carried out by one annotator and subsequently reviewed by another. Following annotation, the dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and testing subsets at a ratio of 7:2:1 for model development and evaluation. A total of 160 X-ray images were annotated and divided into three subsets: 112 images for training, 32 for validation, and 16 for testing, following a 7:2:1 ratio. To ensure annotation consistency and reproducibility, a strict labeling protocol was implemented. Anatomical boundaries were delineated along clearly identifiable radiographic edges, and overlapping regions—such as cranial structures around the otoliths—were separated using multi-polygon masks. Small structures (e.g., otoliths) were subjected to mandatory secondary review by an additional annotator. All labels adhered to a unified class dictionary consisting of five anatomical categories: whole fish, air bladder, spine, eyes, and otoliths.

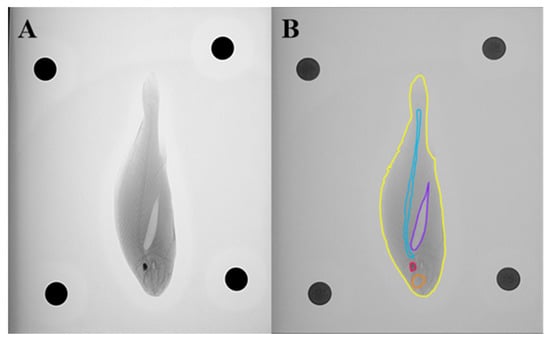

Figure 3.

X-ray imaging and annotation of Large Yellow Croaker. (A) Representative X-ray image of a large yellow croaker specimen acquired using the X-ray imaging system. (B) Example of manual annotation showing five anatomical categories: whole fish (yellow), air bladder (purple), spine (blue), eyes (orange), and otoliths (red).

2.5. Instance Segmentation and Area Calculation

After model training was completed, the optimized weight parameters were applied to perform instance segmentation on the target images. Based on the segmentation outputs, the areas of different anatomical regions of Large Yellow Croaker were calculated, and the magnitude and sources of potential errors were analyzed. Furthermore, the relationships between the areas of the otoliths, spine, air bladder, eyes, and the whole fish were examined. No machine learning model was used to predict area ratios; all morphological quantification was derived directly from instance segmentation outputs and calibrated pixel-area measurements. Using X-ray images as inputs, the model estimated relative area proportions across anatomical parts, and the overall workflow is illustrated in Figure 4. Since X-ray images can only capture the lateral profile of the fish, body thickness could not be measured in this study. Accordingly, only the lateral areas of the otoliths, spine, air bladder, eyes, and the whole fish were used as input parameters for predictive modeling.

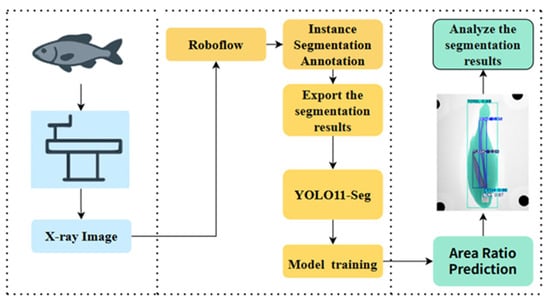

Figure 4.

Overall workflow of the detection system.

2.6. Instance Segmentation Model

Object detection and instance segmentation are among the core tasks in computer vision, and they have developed rapidly in recent years. The YOLO family of models has become widely adopted for detection and segmentation tasks due to its end-to-end inference capability and high real-time efficiency. As the latest version in this series, YOLOv11 introduces notable improvements in network architecture, feature extraction, and decoding efficiency. Its segmentation variant, YOLOv11-Seg, extends the detection framework with an additional mask branch, thereby enabling precise delineation of target regions at the instance level.

Instance segmentation techniques have been increasingly applied in aquaculture. For example, in marine cage farming, Mask R-CNN has been employed to achieve accurate fish body segmentation and length estimation, supporting health monitoring and biomass evaluation [17]. In Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) farming, the Aquabyte system integrates instance segmentation for automatic detection and counting of sea lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis), greatly improving parasite monitoring efficiency [18,19]. In high-density farming environments, lightweight models such as YOLOv8-Seg have been used to achieve real-time segmentation and individual tracking of overlapping fish, thereby facilitating feeding management and yield prediction [20]. These applications highlight that instance segmentation has become a powerful tool for fishery health monitoring, disease prevention, and resource assessment. Nevertheless, challenges remain in achieving an optimal balance between accuracy, inference speed, and model lightweighting.

Based on these considerations, this study introduces targeted improvements to the YOLOv11-Seg framework. The architecture consists of four main components. The input module applies Mosaic augmentation, horizontal flipping, and color perturbation to increase robustness. The backbone uses an improved CSPDarknet variant with convolutional layers, bottlenecks, and CSP connections for efficient feature representation. The FPN–PAN neck integrates multi-scale features, and the detection–segmentation head adds a mask-prediction branch that generates instance-level masks through sparse convolution and mask prototypes. This design provides pixel-level outputs aligned with bounding boxes while maintaining real-time performance and a lightweight structure. To strengthen generalization and address the limited diversity of the dataset, a set of augmentation strategies was applied during training: random horizontal flipping (0.5), Mosaic augmentation (4-image tiling), rotation (±8°), scaling (0.8–1.2), brightness/contrast jitter (±10%), and random cropping (≤12% of the image area). These augmentations simulate variation in posture, illumination, and local contrast in X-ray imaging, improving robustness under different acquisition conditions. With these enhancements, YOLOv11-Seg provides a solid baseline for the instance segmentation tasks in this study.

2.7. CBAM-Enhanced Model

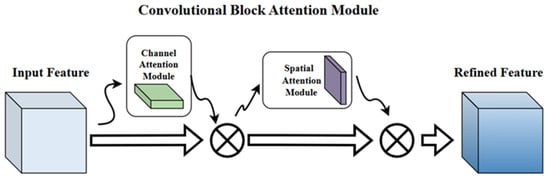

Although YOLOv11 delivers fast inference, it still shows limitations when segmenting fine, low-contrast structures in X-ray images, such as fish bones and the air bladder, especially under complex backgrounds and large scale variation. To improve feature selection for these structures, the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) was integrated into the YOLOv11-Seg architecture, resulting in the YOLOv11-CBAM model (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

CBAM Attention Mechanism Diagram.

CBAM combines channel attention and spatial attention. The channel-attention module reweights feature channels through global pooling and fully connected layers, emphasizing informative responses. The spatial-attention module then highlights salient regions within each feature map. Together, these two steps enhance anatomical cues while suppressing irrelevant background patterns.

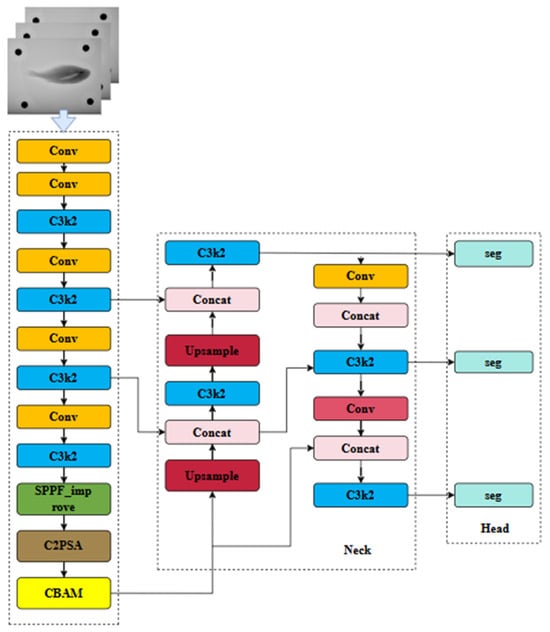

In this study, CBAMs were inserted after the C2PSA blocks at three backbone stages (128-, 256-, and 512-channel outputs) and once in the PAN neck after the 256-channel fusion layer. These positions provide feature maps with adequate semantic information and spatial resolution for effective attention recalibration. A complete schematic of the YOLOv11-C2PSA-CBAM architecture, including feature-map resolutions and CBAM locations, is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Improved YOLOv11-CBAM model structure.

The decision to place CBAM after C2PSA was based on architectural characteristics and empirical results. Early layers mainly encode edge-level textures with limited benefit from attention, whereas deeper layers yield compressed features that are less suitable for spatial refinement. The intermediate C2PSA outputs preserve multi-scale structure and spatial detail, allowing CBAM to enhance the representation of small, low-contrast anatomical regions. In our experiments, YOLOv11-C2PSA-CBAM achieved higher mAP, Dice coefficient, and F1-score than YOLOv11-Seg, with the greatest improvements observed in the segmentation of the air bladder and skeletal edges.

2.8. Experimental Environment and Model Performance Evaluation

The experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 operating system with an NVIDIA GTX 3050 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CL, USA) and CUDA version 12.5. The batch size was set to 8, the initial learning rate was 0.001, and the Adamax optimizer was employed for parameter updates. The library and framework versions used are listed in Table 2. The input image resolution was 2500 × 3052 pixels. Based on YOLO predictions, pixel values of key points were converted into actual measurements, enabling the quantification of five segmented anatomical categories of Large Yellow Croaker. To ensure full reproducibility, all training hyperparameters are reported as follows: Epochs: 300, Batch size: 8, Optimizer: Adamax, Initial learning rate: 0.001, Loss functions: BCE for classification and mask; CIoU for bounding-box regression, Confidence threshold: 0.25, IoU threshold for NMS: 0.7, Mask threshold: 0.5. These hyperparameters were kept constant across all experiments, including the five repeated runs used for stability analysis.

Table 2.

Comparative performance of different instance segmentation models on Large Yellow Croaker X-ray images.

Model performance was primarily evaluated using Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP50, and mAP50–95. The definitions of these metrics are as follows:

In Equations (1) and (2), TP, FP, and FN represent the numbers of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Precision (P) measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive, reflecting the accuracy of the model’s predictions. Recall (R) measures the proportion of actual positive samples that are correctly predicted, reflecting the model’s ability to identify all positive instances, and is therefore also referred to as sensitivity. To ensure a fair comparison across architectures, all baseline models—including YOLOv11, Mask R-CNN, RetinaNet, and Faster R-CNN—were trained under standardized settings. Each model was trained for 300 epochs using an SGD optimizer with momentum, a batch size of 4, and the same data augmentation strategy applied to YOLOv11-CBAM. A cosine learning rate schedule with warm-up was adopted for all models. Early stopping based on validation loss was used to prevent overfitting. These unified training protocols enable reliable evaluation of relative model performance.

The metrics mAP@50 and mAP@50–95 denote the mean Average Precision across all classes under different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds. Specifically, mAP@50 is computed at an IoU threshold of 0.50, whereas mAP@50–95 represents the averaged result across thresholds ranging from 0.50 to 0.95 in increments of 0.05. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of model performance under varying localization stringency, thereby emphasizing the capability of the model for high-precision localization.

2.9. Calculation of Morphological Parameters of Large Yellow Croaker

2.9.1. Instance Area Calculation Method

This study aimed to perform quantitative measurements of different anatomical structures of Large Yellow Croaker using image-based instance segmentation. To achieve this, a one-yuan coin was placed in each experimental image as an internal calibration object, with a known actual area of = 4.90625 cm2. The boundary of the coin was detected using the Hough circle transform, from which its pixel radius was obtained. The average pixel area of the coin , was then obtained by taking the mean value across all detection results:

Here, s denotes the scale factor used to convert pixel counts into actual areas. This calibration step ensures that image-derived measurements remain comparable and quantitatively accurate under different imaging conditions.

2.9.2. Data Processing

Based on the scale calibration, the trained YOLO instance segmentation model was applied to the experimental images for inference, yielding binary masks for the target categories (BONE, ERSHI, EYES, YUBIAO, and TOTAL). For any category the number of pixels can be calculated as:

Here, denotes the indicator function, and represents the class label of instance . By incorporating the scale factor , the actual area of each category can be calculated as:

Furthermore, to compare the relative sizes of different anatomical structures, the area ratio was calculated as:

2.9.3. Error Control

To ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the experimental data, the following quality control measures were implemented during image processing:

- (1)

- Images in which the Hough circle transform failed to stably detect the coin were excluded from area calibration, thereby avoiding errors in the scale factor;

- (2)

- Images for which the segmentation model did not return valid mask information were discarded to prevent false-positive results;

- (3)

- Multiple-circle detection was applied in coin calibration, and the average value was used to reduce single-detection error;

- (4)

- During category statistics, strict consistency was maintained between model output labels and the predefined dictionary to prevent computational deviations caused by label mismatches.

Through these measures, the reliability of scale calibration, instance segmentation, and area calculation was improved, supporting scientific rigor and reproducibility. Coin detection failed in 3 of the 160 X-ray images (1.9%). These cases occurred when the calibration coin was partially occluded by the fish or positioned too close to the image boundary, leading to insufficient contrast for stable detection. Importantly, these images were excluded only because calibration could not be performed; anatomical segmentation remained valid.

The segmentation model produced accurate masks for all anatomical categories in these images, but without a stable scale reference, area measurements could not be converted into physical units. The exclusion of these images reflects a limitation of the calibration step rather than the segmentation model. The three affected samples did not share common attributes in fish size, posture, orientation, or anatomical clarity. Visual inspection confirmed that the failures arose from coin placement variability rather than biological or imaging features of the specimens. Thus, removing these images is unlikely to introduce systematic bias, and the remaining dataset still captures the variability present in the full imaging set.

Future improvements will aim to reduce calibration-related data loss. Possible approaches include using multiple calibration coins placed at varied positions, applying multi-point geometric calibration methods, and improving contrast normalization to ensure stable detection near image boundaries. Incorporating geometric correction algorithms may also mitigate position-dependent failures and further enhance calibration reliability.

2.10. Calibration Error Assessment

Four identical calibration coins were placed around each fish (top, bottom, left, right) to evaluate the reliability and positional stability of the scale calibration procedure. This arrangement provided four independent reference markers in every X-ray image. A set of 160 images was selected for quantitative assessment. The pixel diameters of all four coins were measured in each image and compared. Despite their different positions in the field of view, discrepancies were low, with an average absolute percentage error of 1.26%, a maximum deviation of 3.18%, and a standard deviation of 0.57%. These results indicate that the pixel-to-area conversion factor remains stable across the entire imaging plane.

Perspective distortion was also examined. The X-ray system uses a parallel-beam geometry, which reduces magnification variation across the image. Measurements of the same coin at different positions showed <1.0% variation in pixel diameter, confirming that perspective distortion is negligible under this setup.

The robustness of automatic coin detection was evaluated across all 160 images (640 coins). The YOLOv11-based detector identified 637 of 640 coins, achieving 99.5% detection accuracy. The three missed detections occurred where coin edges overlapped dense skeletal regions; manual inspection confirmed that these cases did not affect anatomical segmentation or area calculation. No false positives were observed. Together, these results validate the accuracy, spatial consistency, and detection reliability of the coin-based calibration procedure.

2.11. Statistical Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification

To provide a rigorous assessment of measurement variability and segmentation consistency, multiple statistical procedures were performed. Normality of area and area-ratio distributions was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was examined using Levene’s test. Depending on distribution characteristics, either one-way ANOVA or the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to compare anatomical structures. When appropriate, Post Hoc multiple-comparison tests (Tukey or Dunn’s test) were conducted to identify pairwise differences.

To quantify estimation uncertainty, bootstrap resampling (2000 iterations) was performed for each anatomical structure to obtain non-parametric 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the mean area ratios. Additionally, multiple measures of dispersion were reported, including standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), and median absolute deviation (MAD). The inclusion of MAD provides enhanced robustness for small and low-contrast structures such as the otoliths. In this study, manual morphometric measurements were collected to document the external body characteristics of each specimen. A total of 10 L. crocea individuals were measured for body length, total length, body height, body thickness, and body weight using a calibrated ichthyometer and vernier calipers. These measurements provide a descriptive reference for the overall body size distribution of the sampled fish and help contextualize the variability of individuals included in the X-ray dataset.

3. Results

3.1. Performance Evaluation of the Instance Segmentation Model for Large Yellow Croaker

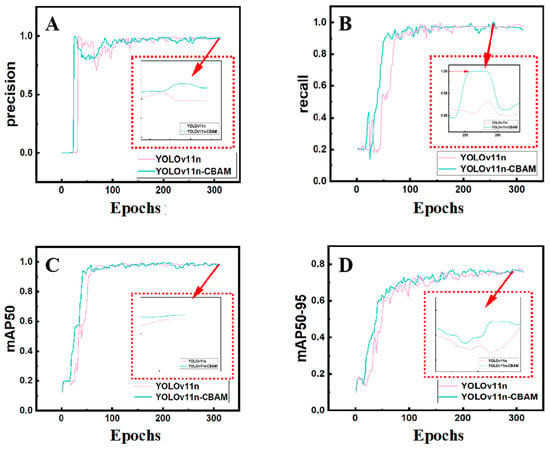

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed architectural improvements, ablation experiments were conducted by comparing the baseline YOLOv11 model with the improved YOLOv11-C2PSA-CBAM model, in which a CBAM was embedded after the C2PSA block. The metric mAP@50 was used to evaluate the basic detection capability under a relatively loose threshold, whereas mAP@50–95 provided a comprehensive measure of localization precision across a range of thresholds. Together, these indicators reflect the overall performance of an object detection model in terms of recall, classification accuracy, and localization robustness, thereby serving as key metrics for balancing practicality and high-precision requirements. Accordingly, our analysis primarily focused on mAP@50 and mAP@50–95. The comparison of model performance across different configurations is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Performance comparison between YOLOv11 and YOLOv11-CBAM models. Training curves are shown for (A) Precision, (B) Recall, (C) mAP50, and (D) mAP50–95 across epochs. The YOLOv11-CBAM consistently exhibits improved convergence stability and higher accuracy, particularly in terms of small-object recognition.

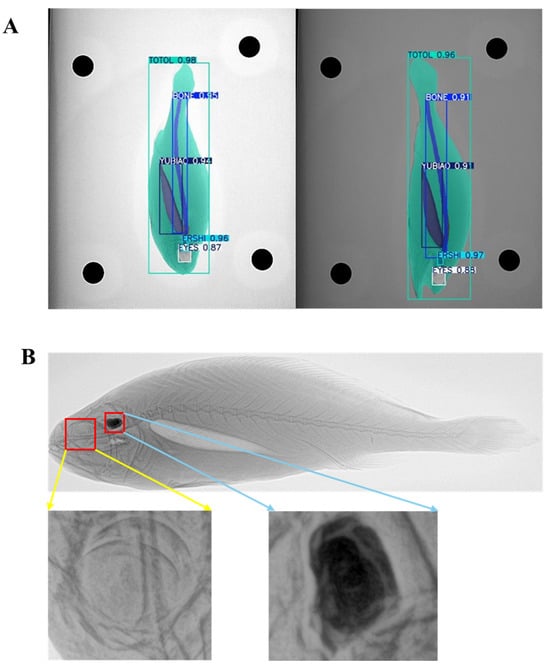

Results showed that the improved model exhibited notable gains in both precision and recall. The integration of the CBAM enhanced localization accuracy and fine-grained segmentation, particularly reflected in improvements of the mAP@50–95 metric. This finding indicates that the improved model can more precisely localize targets and better identify complex backgrounds and structural details. The ability of its model to recognize fine targets after modification is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Instance segmentation performance and anatomical visualization in Large Yellow Croaker X-ray images. (A) Predicted instance segmentation masks generated by the YOLOv11-CBAM model, showing delineation of the whole body, spine, air bladder, eyes, and otoliths. (B) Original X-ray radiograph of L. crocea. The yellow inset highlights the enlarged view of the eye region, and the blue inset shows the enlarged view of the otolith. These close-up views illustrate the fine-scale anatomical features captured by the imaging system and the corresponding segmentation outputs.

Consequently, the YOLOv11-C2PSA-CBAM model achieved more accurate instance segmentation of L. crocea, thereby improving the reliability of area-based measurements. Compared with non-YOLO architectures such as Mask R-CNN, RetinaNet, and Faster R-CNN, the YOLOv11-CBAM model demonstrated competitive accuracy while maintaining substantially faster inference speed. Notably, Mask R-CNN achieved a higher mAP50–95, which is consistent with its design emphasis on high-precision pixel-level segmentation. Nevertheless, YOLOv11-CBAM exhibited more stable boundary delineation for small and low-contrast structures and offered markedly better real-time performance. Instead of characterizing YOLO-based models as having “overall superior performance,” this study now states that “the YOLOv11-CBAM model achieves the best balance between segmentation accuracy and real-time performance across the evaluated architectures.” This revised description more accurately reflects the trade-offs observed in the comparative experiments. While the YOLOv11-CBAM model achieved strong overall performance, we acknowledge that Mask R-CNN obtained a higher mAP50–95, consistent with its well-established capability for high-precision pixel-level segmentation. The findings therefore reflect model behavior within this specific imaging context rather than broad generalization across devices or aquaculture settings.

3.2. Analysis of Instance Segmentation Data

The results of this experiment were exported in dual formats to ensure both traceability and reusability for subsequent analyses. On one hand, detailed information on segmentation and measurement was saved in JSON files, including image scale factors, pixel areas of the reference object (coin), total pixel counts for each class, and their corresponding actual areas. This format facilitates programmatic retrieval and model extension. On the other hand, CSV files were simultaneously generated, recording key attributes such as image name, scale factor, category, pixel count, and area. These files can be directly imported into statistical software packages (e.g., SPSS 27) for variance analysis, correlation testing, and regression modeling.

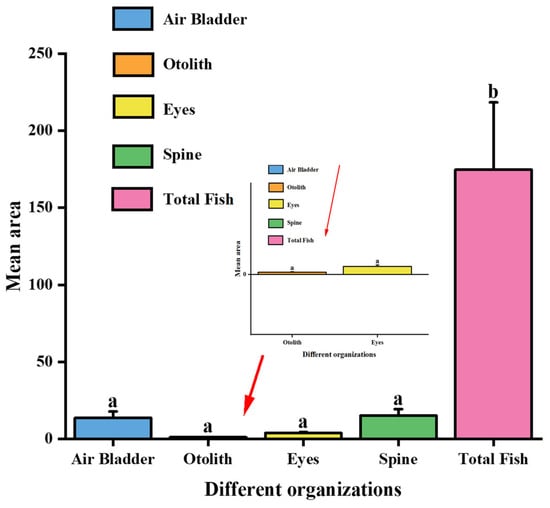

This design not only provides structured and extensible data storage but also ensures standardized inputs for subsequent large-sample statistical analysis, machine learning model training, and error source investigation. At the application level, ten L. crocea individuals were randomly selected from the dataset for detailed processing, and their air bladder, otolith, eye, spine, and whole-body area measurements are listed in Table 3 and Table 4. Statistical analysis yielded the mean values and standard deviations for each structure, as presented in Figure 9.

Table 3.

Measured lateral areas (cm2) of anatomical structures in ten individuals of Large Yellow Croaker based on instance segmentation of X-ray images.

Table 4.

Mean lateral areas and standard deviations (cm2) of anatomical structures in Large Yellow Croaker based on instance segmentation of X-ray images.

Figure 9.

Mean area and standard deviation of anatomical structures. Bars represent the mean ± SD. Red arrows indicate the enlarged views of the corresponding anatomical structures in the inset panel. Different letters above the bars (a, b) denote statistically significant differences among groups (p < 0.05).

The uncertainty of the calibration factor was further quantified by computing its 95% confidence interval based on bootstrap resampling. Propagating this uncertainty through the area estimation pipeline resulted in an average impact of ±2.1% on the final anatomical area measurements. This magnitude is substantially smaller than the inherent biological variation observed among individuals, indicating that calibration-related uncertainty does not meaningfully affect the interpretation of morphometric patterns. Taken together, the calibration experiments, perspective-distortion assessment, and uncertainty-propagation analysis demonstrate that the pixel-to-area conversion procedure is stable across coin positions and orientations. These characteristics support the reliability of the morphological measurements derived in this proof-of-concept study.

Normality assessments indicated that eye and air-bladder area ratios followed approximately normal distributions (Shapiro–Wilk, p > 0.05), whereas otolith ratios exhibited significant deviation from normality (p < 0.05). Variance homogeneity was rejected for otoliths and spine structures (Levene’s test, p < 0.05). Accordingly, ANOVA was applied to normally distributed traits, and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for non-normal traits.

Bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals further supported the stability of air-bladder and spine segmentation, whose CIs were narrow and centered closely around their mean ratios. In contrast, otoliths showed wider CIs and higher dispersion, a pattern consistent with their elevated CV and MAD values. These findings confirm that structural variability differs significantly among anatomical regions and that otolith segmentation is inherently more sensitive to imaging and projection variability. The combined use of SD, CV, and MAD provides a comprehensive characterization of measurement dispersion. The relatively low CV and MAD values of the spine and air bladder reflect consistent segmentation boundaries across individuals. In contrast, the otoliths exhibit higher MAD values, highlighting their susceptibility to small-pixel deviations and confirming the need for dedicated small-object optimization in future work. The agreement between confidence intervals and dispersion metrics supports the reliability of the segmentation workflow under the present dataset.

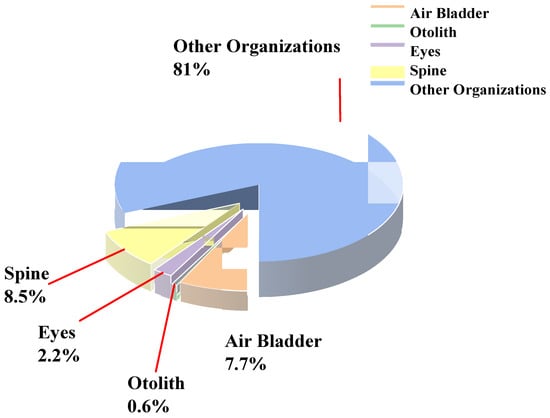

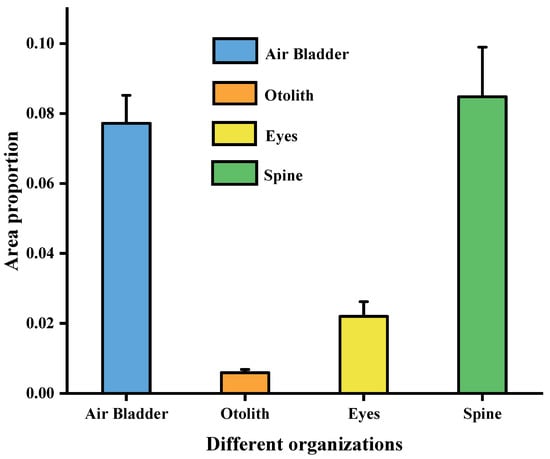

Based on the conversion analysis of pixel-derived areas, the data in Table 3 were used to calculate area ratios, which are summarized in Table 5 and Table 6. The corresponding results are illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 11. Distinct differences were observed in the proportional distribution of various anatomical structures (air bladder, otoliths, eyes, spine, and other tissues) within the whole body of Large Yellow Croaker. Among them, the spine and air bladder accounted for relatively larger proportions, 8.5% (0.0848) and 7.7% (0.0772), respectively, highlighting their essential roles in maintaining body stability and regulating buoyancy. By contrast, the eyes and otoliths occupied much smaller proportions, 2.2% (0.022) and 0.6% (0.0059), respectively, reflecting their limited contribution to the overall body area.

Table 5.

Area proportions (%) of anatomical structures in Large Yellow Croaker based on instance segmentation of X-ray images.

Table 6.

Mean area ratios (%) and standard deviations of anatomical structures in Large Yellow Croaker based on instance segmentation of X-ray images.

Figure 10.

Pie chart of the proportional areas of different structures in Large Yellow Croaker.

Figure 11.

Area proportions and standard deviations of anatomical structures in Large Yellow Croaker.

Analysis of standard deviations further revealed that the spine and air bladder exhibited relatively low variability, suggesting a high degree of consistency and stability across individuals. In contrast, the otoliths and eyes showed greater variability, which may be attributed to reduced boundary clarity and lower resolution of these structures in X-ray images, potentially leading to measurement deviations. Overall, these quantitative findings provide a reliable dataset for subsequent biological studies, particularly for investigating the functional roles of different structures in fish physiology and their potential associations with health status.

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Interpretation of Internal Morphometric Traits

The proposed YOLOv11-CBAM workflow enabled precise, reproducible extraction of five anatomically meaningful structures in L. crocea X-ray images, providing an internally consistent basis for digital morphometrics. The air bladder and spine exhibited the most stable proportional areas, consistent with the strong developmental and functional constraints associated with hydrostatic regulation and axial support [21]. These low-variance metrics align with previous X-ray and μCT studies showing high conservation of skeletal and buoyancy-related structures in teleosts [22,23,24,25], suggesting that such traits may serve as reliable indicators of body condition, musculoskeletal health, and buoyancy efficiency in aquaculture settings.

The eyes and otoliths showed smaller proportional areas and greater variability [26]. While some variation may reflect biological differences—eye morphology responds to ecological adaptation, and otoliths encode environmental and metabolic histories—the magnitude of variation observed here reflects the interplay between biological factors and imaging constraints [27]. Even so, both organs maintained acceptable coefficients of variation, indicating that the segmentation workflow captures these traits with reasonable robustness. Given the ecological and physiological importance of otoliths [28,29] and the role of eye morphology in sensory specialization [30,31], the ability to quantify these structures non-destructively expands the phenomic toolkit available for teleost research and breeding.

The results demonstrate that X-ray-based internal phenotyping can capture biologically relevant traits that are difficult or impossible to obtain from external imaging alone. As such, the workflow provides a foundation for future studies examining allometric scaling, organ-specific growth trajectories [32], and early detection of morphological abnormalities in aquaculture species.

4.2. Technical Challenges and Uncertainty in Small-Object Segmentation

Segmentation accuracy was high, yet the results reveal inherent constraints of detecting very small structures in 2D radiography. Otoliths are extremely small, high-density elements, and their projected area is sensitive to imaging noise, subtle changes in head posture, and overlap with adjacent anatomical structures. These factors introduce variability that is difficult to eliminate in single-view X-ray imaging, even when segmentation performance is strong [33]. Their edges often lie adjacent to dense cranial elements, reducing contrast and making polygonal annotation inherently uncertain. Because these structures occupy few pixels, even a 1–2-pixel deviation can generate several-percent differences in measured area—a pattern reflected in the larger MAD and CV values [23,34]. Multiple physical and computational factors contributed to these challenges: (1) Imaging geometry—Minor deviations in lateral positioning cause noticeable changes in projected otolith shape. (2) Low contrast and partial occlusion—Cranial bone density reduces otolith edge separability. (3) Sensitivity to detector noise—Non-uniform illumination affects small structures disproportionately. (4) Error amplification—Measurement error scales inversely with object size.

CBAM improved feature extraction in low-contrast regions, yet the mechanism cannot compensate for the physical constraints of 2D projection, where depth information is lost and overlapping structures remain unresolved. Previous studies on geometric-distortion robustness have demonstrated that even subtle affine or perspective perturbations can disrupt structural consistency in imaging systems [35,36,37]. This phenomenon has also been observed in attention-driven representation learning, where attention modules improve resistance to local deformation yet still fail to eliminate instability when dealing with extremely small and densely overlapped targets [38,39,40,41]. These insights align with the present findings and explain why otolith segmentation remains highly sensitive to geometric variation despite model-level improvements.

Calibration analyses further supported the robustness of the workflow [41,42]. Across 160 additional X-ray images with coins placed at varying positions and orientations, the mean absolute percentage error remained only 1.82% (maximum: 3.94%). Pixel-diameter variation < 1% confirmed minimal perspective distortion under parallel-beam geometry, and uncertainty propagation showed a modest ±2.1% effect on final area estimates—substantially lower than the biological variation among individuals. Together, these results demonstrate that the pixel-to-area conversion is stable, even though small-object segmentation remains the primary technical bottleneck.

4.3. Dataset Constraints and Strategies for Scalable Expansion

The dataset contains 160 X-ray images, a scale that is suitable for methodological validation. Each image includes detailed annotations for five anatomical structures—whole body, air bladder, spine, eyes, and otoliths—resulting in a high annotation density. Studies on fish X-ray segmentation often rely on fewer than 100 images due to the substantial cost of imaging and manual labeling. Workflows involving fish X-ray or micro-CT phenotyping in general use similarly modest sample sizes, as 3D imaging and organ segmentation require extensive labor and specialized equipment [8,9,10,11,23,43,44,45], positioning the present dataset at a similar or higher level of data richness. The high spatial resolution of X-ray images also increases the information content per sample compared with natural-light datasets [46].

Several limitations remain. All X-ray images were collected from a single aquaculture facility, using one imaging system and covering a relatively narrow range of developmental stages. Only ten individuals met the criteria for high-quality quantitative analysis of area ratios, inherently limiting statistical power and restricting inference on population-level variability [47,48]. Furthermore, the dataset includes only lateral 2D projections, which cannot capture full 3D organ morphology [43,45,49].

To address these constraints, several scalable expansion strategies are feasible: Multi-farm, multi-season sampling to capture environmental and genetic diversity; Inclusion of different age classes and size groups to model allometric scaling; Multi-angle or controlled-orientation acquisition to reduce projection-driven variability; Integration of multi-device imaging to evaluate cross-hardware robustness; Development of larger annotated datasets for training generalized deep-learning models [7,50,51].These expansions will not only enhance the biological interpretability of the measurements but also support more rigorous statistical analyses (variance partitioning, GLMs/GAMs, bootstrap CI estimation) and provide stronger external validation of the workflow. Importantly, this study should be interpreted as a proof-of-concept demonstration, rather than a definitive characterization of L. crocea morphology. The presented ratios are technical exemplars of workflow performance, not population-level biological benchmarks.

4.4. Cross-Species Generalization and Future Research Directions

Many internal anatomical structures—vertebrae, air bladder, cranial elements, and eyes—are highly conserved across teleost lineages. This conservation provides a strong biological foundation for cross-species generalization of the segmentation framework [44,52,53]. The modular design of YOLOv11-CBAM makes it well suited for transfer learning, with only moderate retraining likely required to adapt the model to related taxa such as groupers (Epinephelus), sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus), or pomfret (Pampus). Domain adaptation and multi-species joint training could eventually yield a generalized internal-morphology segmentation model, supporting large-scale phenomics across diverse aquaculture species [7,54,55].

Future work should integrate complementary imaging modalities such as micro-CT and diceCT to provide volumetric validation of 2D area measurements. These methods can resolve three-dimensional morphology with substantially higher fidelity, enabling precise evaluation of structures whose shapes are not well represented in lateral projections [43,56,57]. In addition, technical refinements—such as angle-standardized positioning devices, multi-view X-ray acquisition, and specialized attention modules for ultra-small targets—will be critical for reducing otolith-related variability [58,59,60,61].

Building multi-institutional datasets, benchmarking performance across different X-ray systems, and testing the workflow under practical aquaculture conditions will be necessary for advancing this proof-of-concept into a deployable imaging platform for fish health assessment, breeding applications, and morphological studies [7,62].

5. Conclusions

This study developed and validated an automated instance-segmentation and quantitative measurement workflow for Large Yellow Croaker X-ray images based on the YOLOv11-CBAM framework. A labeled dataset containing five anatomical structures was constructed, and a coin-based calibration method enabled conversion of pixel counts into physical areas, forming a complete processing pipeline. The findings represent feasibility rather than broad applicability; further testing across imaging systems, environments, and species is required before practical deployment in aquaculture.

Incorporating CBAM improved segmentation accuracy and recognition of small structures compared with the baseline YOLOv11 model, yielding stable area-ratio measurements. The quantitative sample size remains limited and should be considered when interpreting the results. The workflow nonetheless demonstrates value for aquaculture health assessment, germplasm evaluation, studies of skeletal development and functional morphology, and environmental monitoring. Statistical testing and uncertainty quantification strengthen the reliability of this proof-of-concept approach.

The method provides an efficient, non-destructive, and standardized platform for fish morphometric analysis and establishes a foundation for larger-scale structural measurements and interdisciplinary applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and H.Z.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, Y.Y., G.Q. and C.W.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, G.Q., Z.W. and T.C.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Z. and H.Z.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, S.Z. and H.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Central Public-Interest: Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, ECSFR, CAFS (2024TD04).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All X-ray imaging data and Larimichthys crocea samples used in this study were obtained and utilized in strict accordance with relevant Chinese regulations on aquatic resource utilization and complied with harmless-treatment principles. The research is based solely on retrospective and non-invasive algorithmic analysis of pre-existing X-ray images. It does not involve any live-animal experiments, does not subject any organism to intervention or manipulation, and does not introduce any new procedures involving animals. According to the Guiding Opinions on the Humane Treatment of Laboratory Animals in China, as well as widely accepted international ethical standards, studies that rely exclusively on pre-existing samples or imaging data and do not involve experimental operations on animals are typically exempt from Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) review. Therefore, we confirm that this study did not require, nor did we seek approval from an ethics committee or institutional review board.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Due to institutional data management policies, the raw X-ray images and intermediate analysis files cannot be publicly shared but can be provided to qualified researchers upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the two corresponding authors, Shengmao Zhang and Hanfeng Zheng, for their continuous guidance, constructive suggestions, and strong support throughout the study. The authors also acknowledge the support from the Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, ECSFR, CAFS (2024TD04). In addition, we thank the South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (SCSFRI), Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, for providing research facilities, technical assistance, and administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Yuan, J.; Lin, H.; Wu, L.; Zhuang, X.; Ma, J.; Kang, B.; Ding, S. Resource Status and Effect of Long-Term Stock Enhancement of Large Yellow Croaker in China. Front. Mar. Sci. Orig. Res. 2021, 8, 743836. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tao, W.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Lin, W.; Rong, H. Morphological structure and quality characteristics of cultured Larimichthys crocea in Ningde. J. Fish. China 2019, 43, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Qiaozhen, K.; Yongquan, S.; Jiafu, L.; Weiqiang, Z. Protection and utilization status and prospect of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) germplasm resources. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 46, 674–682. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, M.; Wolf, N.; Rosenberg, B.; Harris, B.P.; Mathis, A. Perspectives on Individual Animal Identification from Biology and Computer Vision. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 900–916. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwamborn, R.; Mildenberger, T.K.; Taylor, M.H. Assessing sources of uncertainty in length-based estimates of body growth in populations of fishes and macroinvertebrates with bootstrapped ELEFAN. Ecol. Model. 2019, 393, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.-X.; Lin, H.-D.; Wu, L.-S.; Wu, L.-N.; Yuan, J.-G.; Ding, S.-X. Stability of population genetic structure in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea): Insights from temporal, geographical factors, and artificial restocking processes. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Marée, R.; Geurts, P.; Muller, M. Recent Advances in Bioimage Analysis Methods for Detecting Skeletal Deformities in Biomedical and Aquaculture Fish Species. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1797. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shengmao, Z.; Heng, Z.; Fenghua, T.; Hanye, Z.; Yongchuang, S.; Xuesen, C. Application of X-ray in detection of fish tissue and trace elements. J. Appl. Opt. 2024, 45, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urazoe, K.; Kuroki, N.; Maenaka, A.; Tsutsumi, H.; Iwabuchi, M.; Fuchuya, K.; Hirose, T.; Numa, M. Automated Fish Bone Detection in X-Ray Images with Convolutional Neural Network and Synthetic Image Generation. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2021, 16, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Prados, R.; Quintana, J.; Tempelaar, A.; Gracias, N.; Rosen, S.; Vågstøl, H.; Løvall, K. Automatic segmentation of fish using deep learning with application to fish size measurement. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 77, 1354–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mery, D.; Lillo, I.; Loebel, H.; Riffo, V.; Soto, A.; Cipriano, A.; Aguilera, J.M. Automated fish bone detection using X-ray imaging. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Fang, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, S.; Xiong, X.; Yang, H.; Dai, Y. Research progress on application of deep learning in fish recognition, counting, and tracking: A review. J. Dalian Fish. Univ. 2024, 39, 874–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Tang, S.; Feng, J.; Mo, L.; Jin, X. AASNet: A Novel Image Instance Segmentation Framework for Fine-Grained Fish Recognition via Linear Correlation Attention and Dynamic Adaptive Focal Loss. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tan, J.; Lan, G.; Li, A.; Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Yuan, X.; Dong, N. Benchmarking Fish Dataset and Evaluation Metric in Keypoint Detection—Towards Precise Fish Morphological Assessment in Aquaculture Breeding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.12476. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. A New Workflow for Instance Segmentation of Fish with YOLO. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Som, A.; Thopalli, K.; Ramamurthy, K.N.; Venkataraman, V.; Shukla, A.; Turaga, P. Perturbation Robust Representations of Topological Persistence Diagrams. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 638–659. [Google Scholar]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milletarì, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.-A. V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone, D.; Sengar, M.; Lauriano, E.R.; Pergolizzi, S.; Macri’, F.; Salpietro, L.; Favaloro, A.; Satora, L.; Dabrowski, K.; Zaccone, G. Morphology and innervation of the teleost physostome swim bladders and their functional evolution in non-teleostean lineages. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmann, M.A.; Nagesan, R.S.; Andrews, J.V.; Borstein, S.R.; Figueroa, R.T.; Singer, R.A.; Friedman, M.; López-Fernández, H. DiceCT for fishes: Recommendations for pairing iodine contrast agents with μCT to visualize soft tissues in fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 102, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kague, E.; Kwon, R.Y.; Busse, B.; Witten, P.E.; Karasik, D. Standardization of bone morphometry and mineral density assessments in zebrafish and other small laboratory fishes using X-ray radiography and micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Min. Res. 2024, 39, 1695–1710. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.N.; You, M.; Ulhaq, Z.S.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Tse, W.K.F. Micro-CT analysis reveals the changes in bone mineral density in zebrafish craniofacial skeleton with age. J. Anat. 2023, 242, 544–551. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauber, M.; Müller, R. Micro-computed tomography: A method for the non-destructive evaluation of the three-dimensional structure of biological specimens. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008, 455, 273–292. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, F.; Mitchell, L.J.; Tettamanti, V.; Fogg, L.G.; de Busserolles, F.; Cheney, K.L.; Marshall, N.J. Visual system diversity in coral reef fishes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 106, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, J.C.; Doubleday, Z.A.; Chung, M.-T.; Gillanders, B.M. Experimental support towards a metabolic proxy in fish using otolith carbon isotopes. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223, jeb217091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilieri-Asch, V.; Shaw, J.A.; Mehnert, A.; Yopak, K.E.; Partridge, J.C.; Collin, S.P. diceCT: A Valuable Technique to Study the Nervous System of Fish. eNeuro 2020, 7. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, S.E.; Reis-Santos, P.; Cabral, H.N. Otolith chemistry in stock delineation: A brief overview, current challenges and future prospects. Fish. Res. 2016, 173, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Mirbach, T.; Olbinado, M.; Rack, A.; Mittone, A.; Bravin, A.; Melzer, R.R.; Ladich, F.; Heß, M. In-situ visualization of sound-induced otolith motion using hard X-ray phase contrast imaging. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3121. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiditsch, I.P.; Ladich, F.; Heß, M.; Schlepütz, C.M.; Schulz-Mirbach, T. Revealing sound-induced motion patterns in fish hearing structures in 4D: A standing wave tube-like setup designed for high-resolution time-resolved tomography. J. Exp. Biol. 2022, 225, jeb243614. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollas-Galván, T.; Avila-Villa, L.A.; Martínez-Porchas, M.; Hernandez-Lopez, J. Rickettsia-like organisms from cultured aquatic organisms, with emphasis on necrotizing hepatopancreatitis bacterium affecting penaeid shrimp: An overview on an emergent concern. Rev. Aquac. 2014, 6, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos-Filho, J.E.; Thomsen, F.S.L.; Stosic, B.; Antonino, A.C.D.; Duarte, D.A.; Heck, R.J.; Lessa, R.P.T.; Santana, F.M.; Ferreira, B.P.; Duarte-Neto, P.J. Peeling the Otolith of Fish: Optimal Parameterization for Micro-CT Scanning. Front. Mar. Sci. Orig. Res. 2019, 6, 728. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.F.; Keat, N. Artifacts in CT: Recognition and avoidance. Radiographics 2004, 24, 1679–1691. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Xia, Z.; Ma, B.; Shi, Y.-Q. Light-Field Image Multiple Reversible Robust Watermarking Against Geometric Attacks. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 5861–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveri, P.; Forlani, C.; Borghese, N.A.; Ferrigno, G. Distortion correction for x-ray image intensifiers: Local unwarping polynomials and RBF neural networks. Med. Phys. 2002, 29, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.; Metcalfe, P.; Liney, G.; Batumalai, V.; Dundas, K.; Glide-Hurst, C.; Delaney, G.P.; Boxer, M.; Yap, M.L.; Dowling, J.; et al. MRI geometric distortion: Impact on tangential whole-breast IMRT. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2016, 17, 7–19. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, M.; Yang, J.; Gui, J.; Zhang, S. From Simple to Complex Scenes: Learning Robust Feature Representations for Accurate Human Parsing. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5449–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhu, B.; Tang, T.; Tan, X.; Gui, Y.; Yao, Q. An Adaptive Attention Fusion Mechanism Convolutional Network for Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-W.; Kim, B.-G. Attention-based scale sequence network for small object detection. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.S.; Voban, A.A.B.; Arnob, A.B.H.; Naim, A.; Ahmed, M.K.; Islam, M.S. DANet: Enhancing Small Object Detection through an Efficient Deformable Attention Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on the Cognitive Computing and Complex Data (ICCD), Huai’an, China, 21–22 October 2023; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Klever, J.; de Motte, A.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Brühschwein, A. Evaluation and Comparison of Self-Made and Commercial Calibration Markers for Radiographic Magnification Correction in Veterinary Digital Radiography. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2021, 35, 010–017. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, V.; Shkarin, R.; Wernet, T.; Wittbrodt, J.; Baumbach, T.; Loosli, F. Quantitative morphometric analysis of adult teleost fish by X-ray computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.; Gistelinck, C.A.; Huber, P.; Lee, J.; Thompson, M.H.; Monstad-Rios, A.T.; Watson, C.J.; McMenamin, S.K.; Willaert, A.; Parichy, D.M.; et al. MicroCT-Based Phenomics in the Zebrafish Skeleton Reveals Virtues of Deep Phenotyping in a Distributed Organ System. Zebrafish 2018, 15, 77–78. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrialovanirina, N.; Poloni, L.; Laffont, R.; Caillault, É.P.; Couette, S.; Mahé, K. 3D meshes dataset of sagittal otoliths from red mullet in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.F.A.; Turra, E.M.; de Alvarenga, É.R.; Passafaro, T.L.; Lopes, F.B.; Alves, G.F.; Singh, V.; Rosa, G.J. Deep Learning image segmentation for extraction of fish body measurements and prediction of body weight and carcass traits in Nile tilapia. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.V.; Lanni, D.; Xu, Y.; Michaelson, J.S.; McMenamin, S.K. Dynamics of the Zebrafish Skeleton in Three Dimensions During Juvenile and Adult Development. Front. Physiol. Orig. Res. 2022, 13, 875866. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Monstad-Rios, A.T.; Bhimani, R.M.; Gistelinck, C.; Willaert, A.; Coucke, P.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Kwon, R.Y. Phenomics-Based Quantification of CRISPR-Induced Mosaicism in Zebrafish. Cell Syst. 2020, 10, 275–286.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucklow, C.V.; Genner, M.J.; Turner, G.F.; Maclaine, J.; Benson, R.; Verd, B. A whole-body micro-CT scan library that captures the skeletal diversity of Lake Malawi cichlid fishes. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Di Biagio, C.; Dellacqua, Z.; Raman, R.; Martini, A.; Boglione, C.; Muller, M.; Geurts, P.; Marée, R. Empirical Evaluation of Deep Learning Approaches for Landmark Detection in Fish Bioimages. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2022 Workshops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 470–486. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Mei, J. Machine learning for extracting morphological phenotypic traits and estimating weight in largemouth bass. Aquac. Fish. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakashita, M.; Sato, M.; Kondo, S. Comparative morphological examination of vertebral bodies of teleost fish using high-resolution micro-CT scans. J. Morphol. 2019, 280, 778–795. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scadeng, M.; McKenzie, C.; He, W.; Bartsch, H.; Dubowitz, D.J.; Stec, D.; Leger, J.S. Morphology of the Amazonian Teleost Genus Arapaima Using Advanced 3D Imaging. Front. Physiol. Orig. Res. 2020, 11, 260. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Kondo, K.; Senou, H. Transferable Deep Learning Model for the Identification of Fish Species for Various Fishing Grounds. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, D.; Vellaturi, G.; Ibrahim, S.H.S.; Molugu, S.; Desanamukula, V.S.; Kocherla, R.; Vatambeti, R. Enhanced deep learning models for automatic fish species identification in underwater imagery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gignac, P.M.; Kley, N.J.; Clarke, J.A.; Colbert, M.W.; Morhardt, A.C.; Cerio, D.; Cost, I.N.; Cox, P.G.; Daza, J.D.; Early, C.M.; et al. Diffusible iodine-based contrast-enhanced computed tomography (diceCT): An emerging tool for rapid, high-resolution, 3-D imaging of metazoan soft tissues. J. Anat. 2016, 228, 889–909. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Vanselow, D.J.; Yakovlev, M.A.; Katz, S.R.; Lin, A.Y.; Clark, D.P.; Vargas, P.; Xin, X.; Copper, J.E.; Canfield, V.A.; et al. Computational 3D histological phenotyping of whole zebrafish by X-ray histotomography. eLife 2019, 8, e44898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S.; Jagadeeswaran, P.; Halpern, M.E. Radiographic analysis of zebrafish skeletal defects. Dev. Biol. 2003, 264, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Li, H.; Xin, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z. Small object detection based on hierarchical attention mechanism and multi-scale separable detection. IET Image Process. 2023, 17, 3986–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhu, S.; Tang, G.; Ke, C.; Wang, T. A Small-Object Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8s for UAV Image Scenarios. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, R.; Lin, C. LFN-YOLO: Precision underwater small object detection via a lightweight reparameterized approach. Front. Mar. Sci. Orig. Res. 2025, 11, 1513740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Yuna, Y. Phenotyping and phenomics in aquaculture breeding. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 7, 140–146. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).