Abstract

Glucocorticoids are key regulators of vertebrate physiology, orchestrating metabolic, immune, and developmental processes that enable adaptation to stress. In teleosts, cortisol is the primary glucocorticoid, acting through classical genomic pathways and rapid non-genomic mechanisms. Although genomic signaling has been widely characterized, non-genomic actions remain poorly understood in skeletal muscle, a tissue of both biological and economic importance. In this study, we examined the effects of cortisol and its membrane-impermeable analog, cortisol-BSA, on rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) skeletal muscle under in vivo and in vitro conditions. Transcript analysis demonstrated that cortisol and cortisol-BSA rapidly induced pax3 (2.28 ± 0.22- and 2.48 ± 0.45-fold change, respectively) and myf5 expression (3.03 ± 0.47- and 2.31 ± 0.29-fold change, respectively) at 1 h, whereas prolonged cortisol and cortisol-BSA exposure resulted in their downregulation (0.34 ± 0.07- and 0.38 ± 0.14-fold change, respectively). In cultured myotubes, cortisol-BSA activated protein kinase A (PKA) (2.24 ± 0.25-fold change) and enhanced phosphorylation of its downstream target CREB (3.2 ± 0.21-fold change) in a time-dependent manner; these effects were abolished by the PKA inhibitor H89. Moreover, inhibition of PKA signaling suppressed cortisol-BSA–induced pax3 and myf5 expression (1.31 ± 0.28-fold change and 1.89 ± 0.28-fold change, respectively). Together, these findings provide the first mechanistic evidence that non-genomic cortisol signaling regulates the PKA–CREB axis in fish skeletal muscle, promoting the early transcriptional activation of promyogenic factors. This work underscores the complementary role of rapid cortisol actions in fine-tuning myogenic responses under acute stress, offering new perspectives on muscle plasticity in teleosts.

Key Contribution:

This study provides the first mechanistic evidence that non-genomic cortisol signaling regulates the PKA–CREB pathway in rainbow trout skeletal muscle, leading to the rapid expression of promyogenic transcription factor genes pax3 and myf5.

1. Introduction

Fishes exhibit a remarkable capacity for continuous muscle growth throughout their lifespan, a phenomenon attributed to their indeterminate growth strategy [1]. The process of myogenesis involves both the formation of new muscle fibers (hyperplasia) and the enlargement of existing fibers (hypertrophy), making skeletal muscle a highly dynamic tissue in teleosts [2]. Myogenesis originates during embryogenesis with the formation of somites from the mesoderm, which give rise to myogenic precursor cells (MPCs) [3]. These MPCs remain as a reservoir of satellite cells in adult muscle, where they can be reactivated to sustain growth and regeneration [3]. Central to the regulation of myogenesis are the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), a family of transcription factors that orchestrate the sequential activation, proliferation, and differentiation of MPCs in vertebrate [4,5]. Among these, myf5 and pax3 play pivotal roles [6]. myf5 acts as one of the earliest determinants of myogenic lineage commitment, directing satellite cells toward the myogenic fate and promoting their proliferation and differentiation into myoblasts [7,8]. Conversely, pax3 is essential for maintaining satellite cell identity and self-renewal [9,10]. Together, the coordinated actions of myf5 and pax3 exemplify the balance between preserving the stem-cell pool and committing cells to differentiation, a balance that underpins muscle plasticity in fish [11].

Cortisol, the main glucocorticoid in teleost fishes, plays a central role in regulating skeletal muscle growth, particularly under stress conditions [12]. As the final effector of the hypothalamic–pituitary–interrenal (HPI) axis, cortisol integrates physiological responses to environmental challenges such as crowding, hypoxia, and temperature fluctuations [13]. Its actions are primarily mediated through the genomic pathway, in which cortisol binds to the intracellular glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [14]. Once bound, the hormone–receptor complexes translocate to the nucleus and interact with glucocorticoid response elements (GREs), directly modulating the transcription of genes critical for cell cycle regulation, metabolism, and myogenic differentiation [15]. Beyond this classical mechanism, a non-genomic cortisol signaling pathway has also been described, involving the activation of membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptors capable of rapidly modulating early intracellular signaling events [16]. Although both genomic and non-genomic effects of cortisol have been investigated in various teleost species and tissues, their specific roles in skeletal muscle and implications for growth remain poorly understood.

In vivo and in vitro studies from our research group have shed light on the early effects of cortisol through non-genomic mechanisms in teleost skeletal muscle. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses revealed that cortisol, acting via non-genomic pathways, rapidly enhances the expression of genes involved in anabolic processes such as focal adhesion, cell cycle control, and ribosomal biogenesis [17,18], while repressing the expression of catabolic genes including murf-1 and atrogin-1 [19]. Moreover, these rapid actions appear to influence the regulation of genes associated with energy balance through the transcription factor CREB [20,21]. In contrast, cortisol acting via genomic mechanisms positively regulates the expression of proteolytic and apoptotic genes, including those related to protein ubiquitination, autophagy, and calpains [17,22]. Collectively, these findings suggest that cortisol exerts dual, temporally distinct effects on muscle physiology, an early anabolic phase mediated by non-genomic signaling and a delayed catabolic phase driven by genomic regulation. This dual dynamic underscores the complexity of cortisol signaling in fish skeletal muscle, integrating both rapid non-genomic and sustained genomic mechanisms to balance growth and stress responses [18]. In the present study, we evaluated the mRNA levels of pax3 and myf5 in the skeletal muscle of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) administered cortisol or cortisol–BSA, as well as in cultured rainbow trout myotubes, to assess the contribution of the non-genomic cortisol signaling pathway. Notably, our experiments revealed that the membrane-initiated action of cortisol rapidly activated the PKA–CREB signaling pathway, and that modulation was directly associated with changes in the expression of the myogenic genes pax3 and myf5. Taken together, this work provides novel evidence that cortisol, beyond its classical genomic pathway, can rapidly influence intracellular signaling cascades to modulate the transcriptional dynamics of key myogenic regulators in fish skeletal muscle.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vivo Assay of Cortisol and Cortisol-BSA Administration in Rainbow Trout

The study adhered to animal welfare procedures and was approved by the bioethics committees of the Universidad Andres Bello and the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research of the Chilean government, approval code 012/2023 and approval date 14 April 2023. The experimental protocol employed for fish sampling and in vivo trials has been previously reported [17]. Briefly, juvenile rainbow trout (O. mykiss) (9.7 ± 0.26 g) were obtained from Pisciculture Río Blanco (V Region, Chile). The fish were held under natural environmental conditions, with water temperature maintained at 14 ± 1 °C and a 12:12 h light–dark photoperiod, and were fed commercial pellets daily, except on the day prior to the in vivo trial. To suppress endogenous cortisol production, fish were anesthetized with benzocaine (25 mg/L) and intraperitoneally injected with metyrapone (1 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) one hour before treatments. Metyrapone is an inhibitor of the enzyme 11-β-hydroxylase, which results in the blockade of cortisol synthesis [23]. Ninety-six trout were then randomly assigned to four tanks and administered either cortisol (10 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; n = 24 trout) or cortisol–bovine serum albumin (BSA 10 mg/kg; US Biological, Salem, MA, USA; n = 24 trout). Control groups received either a vehicle solution (DMSO, 1× PBS, and 0.1% NP-40: n = 24 trout) or BSA alone (0.3 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; n = 24 trout). Eight fish were randomly sampled and euthanized at 1, 3, and 9 h post-treatment using a benzocaine overdose (300 mg/L). White myotomal skeletal muscle was dissected from the epaxial region, preserved in RNAlater (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.2. Treatment of Rainbow Trout Myotubes with Cortisol and Cortisol-BSA

Primary culture of rainbow trout myotubes was previously described [20]. Briefly, juvenile rainbow trout (12.0 ± 1.2 g) were euthanized using an overdose of benzocaine solution (10 mg/mL). Myotomal muscle was then subjected to mechanical and enzymatic dissociation with 0.1% collagenase and 0.1% trypsin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) prepared in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM). The resulting cell suspension was sequentially filtered through 100-μm and 40-μm strainers, after which satellite cell precursors (myoblasts) were seeded onto poly-L-lysine/laminin-coated culture plates. Myoblasts were allowed to proliferate and differentiate for ten days in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Scientific, Hanover Park, IL, USA) until myotubes were obtained. Cultures were then exposed to physiological concentrations of cortisol (276 nM; Sigma) or its membrane-impermeable analog cortisol–BSA (276 nM; US Biological, Salem, MA, USA). These concentrations are equivalent to plasma cortisol levels reported in juvenile rainbow trout under acute stress conditions [19]. The control group received either the vehicle (DMSO, 1× PBS, and 0.1% NP-40) or BSA alone (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples for myf5 and pax3 expression analyses were collected at 1 and 6 h post-treatment. In a second set of experiments, myotubes were pre-incubated with the PKA inhibitor H89 (1 μM) for 30 min prior to stimulation with BSA or cortisol–BSA (276 nM), and samples for PKA and CREB phosphorylation analyses were obtained at 15, 30, and 60 min. In the third experiment, myotubes were pretreated with H89 under the same conditions, and pax3 and myf5 expression were assessed 1 h after stimulation. For each analyzed time point, experiments were conducted using three biological replicates (n = 3) in three independent experiments for both Western blot and qPCR assays. No technical replicates were performed, except for qPCR analyses, which included two technical replicates per biological sample.

2.3. PKA and CREB Immunoblot Analysis

Following treatment, myotubes were placed on ice, rinsed twice with PBS, and lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 5 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA). Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and maintained on ice. Protein concentrations were quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Hanover Park, IL, USA). Equal protein amounts were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% non-fat dry milk. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, washed, and subsequently exposed to horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein detection was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK), and band intensities were quantified by densitometric analysis with ImageJ software 1.54 [24]. Primary antibodies against pCREB (Cell Signaling #9198; 1:1000 dilution), CREB (Cell Signaling #9104; 1:1000 dilution), PKA phosphorylated substrate (Cell Signaling #9621; 1:1000 dilution), H2B (Abcam #1790; 1:2000 dilution) and HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit. Antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) and Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

2.4. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and Real-Time PCR

RNA was isolated from skeletal muscle and cultured myotubes using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Concentration and purity were determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA), and RNA integrity was verified on a 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gel. Residual genomic DNA was removed using the gDNA Wipeout Buffer provided in the cDNA synthesis kit (Qiagen, Austin, TX, USA). A total of 100 ng of RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA for 30 min at 42 °C following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was carried out on Stratagene MX3000P system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Each 20 μL reaction contained 7.5 μL of 2× Brilliant® II SYBR® Green master mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), 6 μL of 20-fold diluted cDNA, and 250 nM of each primer. Primer sequences for pax3, myf5, and fau are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences.

Amplifications were run in triplicate under the following conditions: initial activation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C (denaturation), 30 s at 58–67 °C (annealing), and 30 s at 72 °C (extension). To verify amplification specificity, melting curve analysis was performed. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with the vehicle-treated group serving as control [25]. The 40S ribosomal protein (fau) was used as housekeeping gene.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances. When assumptions were met, differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Results are expressed as mean (n = 6) ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of pax3 and myf5 Expression in Rainbow Trout Skeletal Muscle and Myotubes Induced by Cortisol and Cortisol-BSA

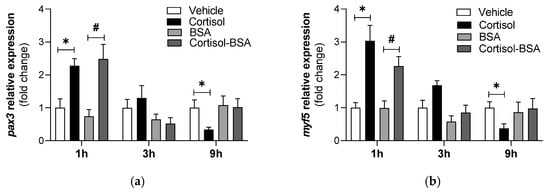

Given that a previous RNA-seq study demonstrated that cortisol, via a non-genomic mechanism, increases the expression of the promyogenic transcription factors pax3 and myf5 [17], we sought to validate this observation using RT-qPCR. Our results showed that rainbow trout exposed in vivo to cortisol or cortisol-BSA displayed a significant increase in pax3 mRNA levels at 1 h (2.28 ± 0.22-fold change; 2.48 ± 0.45-fold change, respectively). However, by 9 h, only cortisol treatment produced a marked decrease (0.34 ± 0.07-fold change), while no changes were observed under cortisol-BSA treatment (Figure 1a). A similar trend was observed for myf5 expression, with both cortisol and cortisol-BSA treatments inducing an increase at 1 h (3.03 ± 0.47-fold change; 2.31 ± 0.29-fold change, respectively), followed by a decrease at 9 h in the cortisol-treated group (0.38 ± 0.14-fold change) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Expression of pax3 (a) and myf5 (b) in rainbow trout treated in vivo with cortisol or cortisol-BSA. Relative expression was normalized against the expression of fau as reference gene. The results are expressed as a means ± SEM (n = 6). * Indicates significant differences (p-value < 0.05) between vehicle and cortisol group. # Indicates significant differences (p-value < 0.05) between BSA and Cortisol-BSA group. Differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

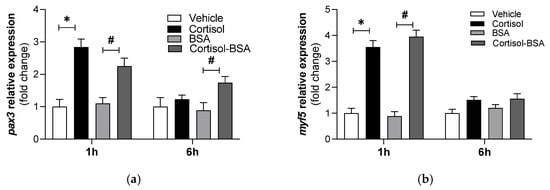

To further assess cortisol-mediated regulation of pax3 and myf5, in vitro rainbow trout myotubes were stimulated with cortisol or cortisol-BSA for 1 and 6 h. Consistent with the in vivo results, pax3 mRNA levels were elevated after 1 h of treatment with either cortisol (2.84 ± 0.25-fold change) or cortisol-BSA (2.25 ± 0.24-fold change) (Figure 2a). A similar trend was observed for myf5 expression, with both cortisol and cortisol-BSA treatments inducing an increase at 1 h (3.55 ± 0.25-fold change; 3.95 ± 0.26-fold change, respectively). Notably, a significant increase in pax3 expression was also observed at 6 h in myotubes treated with cortisol-BSA (1.74 ± 0.19-fold change) (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Expression of pax3 (a) and myf5 (b) in myotubes stimulated with cortisol or cortisol-BSA. pax3 and myf5 expression values were normalized against the expression of fau as reference gene. The results are expressed as a means ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 3) in three independent experiments. * Indicates significant differences (p-value < 0.05) between vehicle and cortisol group. # Indicates significant differences (p-value < 0.05) between BSA and Cortisol-BSA group. Differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

3.2. Assessment of PKA-CREB Pathway Activation in Rainbow Trout Myotubes Induced by Cortisol-BSA

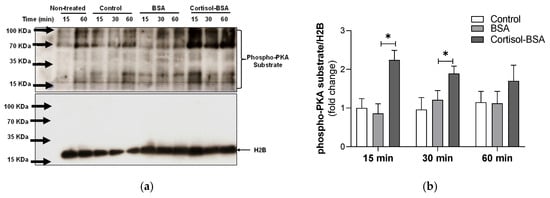

To assess the early activation of protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB mediated by a non-genomic cortisol mechanism, myotubes were stimulated with cortisol-BSA for 15, 30, and 60 min in the presence or absence of H89, a specific PKA inhibitor. Western blot analysis showed that cortisol-BSA induced rapid phosphorylation of PKA substrates at 15 and 30 min after treatment (2.24 ± 0.25-fold change; 1.89 ± 0.19-fold change, respectively) (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

PKA activation in rainbow trout myotubes induced by cortisol-BSA at 15, 30, or 60 min after treatment. (a) Western blot of phospho-PKA substrate and H2B. (b) Densitometric analysis of the Western blot showing a phospho-PKA substrate/H2B ratio. The results are expressed as a means ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 3) in three independent experiments. Non-treated group is internal control and is not considered in densitometric analysis. * Indicates significant differences (p-value < 0.05) compared with the BSA group. Differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

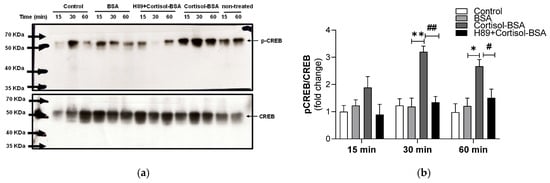

Moreover, CREB phosphorylation increased at 30 and 60 min following cortisol-BSA stimulation (3.2 ± 0.21-fold change; 2.67 ± 0.25-fold change, respectively), and this effect was reduced in the presence of H89 (1.34 ± 0.22-fold change; 1.51 ± 0.32-fold change, respectively) (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

CREB phosphorylation in rainbow trout myotubes induced by cortisol-BSA at 15, 30, and 60 min after treatment. (a) Western blot of p-CREB and CREB. (b) Densitometric analysis of the Western blot showing p-CREB/CREB ratio. The results are expressed as a means ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 3) in three independent experiments. Non-treated group is internal control and is not considered in densitometric analysis. Differences between BSA and Cortisol-BSA groups are shown in * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01. Differences between cortisol-BSA and H89 + cortisol-BSA groups are shown in # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01. Differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

3.3. Assessment of pax3 and myf5 Expression in Rainbow Trout Myotubes Induced by Cortisol-BSA and Mediated by PKA-CREB Pathway

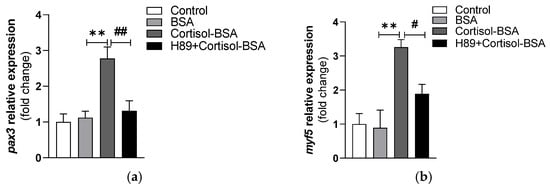

Since the maximum effects on pax3 and myf5 expression mediated by the non-genomic cortisol pathway were observed 1 h post-treatment, we evaluated the impact of inhibiting the PKA–CREB pathway on the expression of these myogenic factors at that time point. Notably, pretreatment of myotubes with H89 abolished the pax3 expression (1.31 ± 0.28-fold change) (Figure 5a) and reduced myf5 expression (1.89 ± 0.28-fold change) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Expression of pax3 (a) and myf5 (b) in myotubes stimulated with cortisol-BSA in the presence or absence of H89. pax3 and myf5 expression values were normalized against the expression of fau as reference gene. The results are expressed as a means ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 3) in three independent experiments. Differences between BSA and Cortisol-BSA groups are shown in ** p < 0.01. Differences between H89 + Cortisol-BSA and Cortisol-BSA groups are shown in # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01. Differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

4. Discussion

This study provides new mechanistic evidence that cortisol, acting through a non-genomic pathway, can rapidly activate intracellular signaling cascades in rainbow trout skeletal muscle, leading to the early induction of promyogenic transcription factors. Specifically, we demonstrate that membrane-initiated cortisol actions stimulate the PKA–CREB signaling pathway, which in turn regulates the expression of pax3 and myf5. These results broaden the current understanding of cortisol signaling in fish muscle, which has historically been attributed mainly to genomic mechanisms [26] and, more recently, to epigenomic regulation [27]. The transient upregulation of pax3 and myf5 observed one hour after cortisol or cortisol–BSA exposure suggests that membrane-initiated cortisol signaling contributes to the rapid activation of satellite cells and the early programming of myogenesis. In this context, Pax3 functions as a key regulator of muscle progenitor maintenance and activation [28], whereas myf5 is critical for lineage commitment and myoblast proliferation [29]. Comparable transient transcriptional responses have also been described in mammalian systems, where glucocorticoids elicit early stimulatory effects that are later followed by gene repression through genomic feedback [30].

Our research group has previously shown that cortisol can modulate early anabolic processes in teleost skeletal muscle through non-genomic mechanisms. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses revealed that cortisol–BSA upregulates the expression of genes associated with focal adhesion, cell cycle progression, and ribosomal biogenesis [17,18] while repressing catabolic markers such as murf-1 and atrogin-1 [19]. Moreover, early non-genomic cortisol effects appear to influence the expression of genes associated with energy balance [21,31]. These findings, together with the present results, reinforce the idea that cortisol exerts temporally distinct effects in skeletal muscle, an initial anabolic phase mediated by rapid membrane signaling, followed by a delayed catabolic response driven by genomic regulation. Despite this growing body of evidence, the molecular identity of the receptor(s) mediating these rapid effects remains unresolved. Several hypotheses have been proposed: (i) cortisol may alter membrane fluidity, thereby activating intracellular signaling pathways [32,33]; (ii) a distinct membrane receptor, possibly a member of the GPCR family, as described for non-genomic sex steroid signaling in fish, may initiate downstream signaling [34,35]; (iii) intracellular GRs may translocate to or interact with the plasma membrane, acting as mediators of rapid signaling [20,36]; and (iv) cortisol may modulate plasma membrane Ca2+ channels, leading to changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations independently of membrane receptors [37]. Indeed, elevated cytosolic Ca2+ has been identified as a crucial second messenger in rapid glucocorticoid signaling in vertebrates [38]. The current results are consistent with these possibilities and suggest that multiple receptor types or molecular mechanisms may coexist in fish muscle.

Our findings further demonstrate that the PKA–CREB pathway acts as a central mediator of cortisol’s membrane-initiated signaling. In mammalian cells, activation of PKA and subsequent phosphorylation of CREB regulate mitochondrial biogenesis through the upregulation of PGC1α, a master regulator of energy metabolism [39]. Similarly, PKA activity has been linked to the suppression of proteolysis in skeletal muscle by activating CREB and elevating cAMP levels [40]. In this study, phosphorylation of PKA substrates and CREB following cortisol-BSA treatment, together with their inhibition by the PKA blocker H89, confirmed that this pathway is required for the transcriptional activation of pax3 and myf5. These results are consistent with the findings of Roy and Rai [16], who reported that PKA activation underlies the non-genomic effects of cortisol in phagocyte cultures, as both adenylate cyclase and PKA inhibitors abolished the rapid inhibitory action of cortisol-BSA [16]. Likewise, our observations align with those of Dindia et al. [41], who demonstrated increased phosphorylation of PKA substrates in rainbow trout liver, supporting rapid activation mediated by non-genomic cortisol signaling [41]. Furthermore, evidence from mammalian systems indicates that hippocampal GRs can participate in CREB activation through non-genomic mechanisms [42], highlighting the evolutionary conservation of this signaling pathway.

This mechanistic connection highlights the role of kinase signaling in linking membrane-initiated cortisol actions to nuclear transcriptional responses. CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) is a key regulator of myogenesis, controlling the transcription of genes involved in muscle cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival [43]. Its phosphorylation activates downstream pro-myogenic pathways, thereby integrating upstream signaling events with muscle-specific gene expression [44]. Notably, PKA has been identified as the principal kinase responsible for CREB phosphorylation, as demonstrated in murine skeletal muscle cells exposed to the synthetic cortisol analog dexamethasone [45]. In addition, PKA–CREB signaling has been shown to regulate myogenesis in mouse embryos cultured ex vivo [46]. Conversely, chronic exposure to cortisol in mammalian myoblasts downregulates pax3, pax7, myf5, and myoD expression, indicating a genomic, inhibitory effect at later stages [47]. The present study adds to this understanding by demonstrating that cortisol’s membrane actions can rapidly enhance pax3 and myf5 expression in fish muscle, suggesting a conserved function of non-genomic glucocorticoid signaling in the early phases of myogenesis [48].

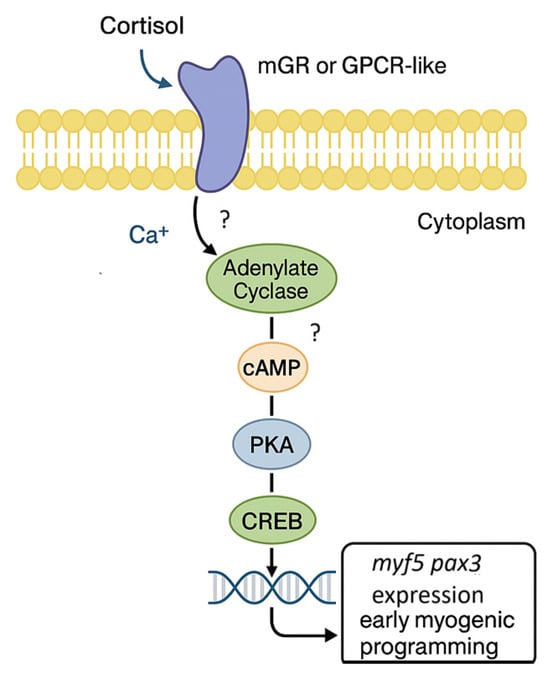

Taken together, our findings support a model in which cortisol binds to a membrane-associated receptor, potentially a membrane glucocorticoid receptor (mGR) or a GPCR-like protein, promoting a putative Ca2+ influx and the adenylate cyclase activation. These events elevate intracellular cAMP levels, activating PKA and leading to CREB phosphorylation, which in turn induces the early transcription of pax3 and myf5 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed model of non-genomic cortisol signaling in rainbow trout skeletal muscle. Cortisol binds to a putative membrane receptor (mGR or GPCR-like) located on the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle cells, triggering a putative Ca2+ influx and activation of adenylate cyclase. The resulting increase in intracellular cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates the transcription factor CREB. Phosphorylated CREB translocates to the nucleus, where it promotes the transcription of pax3 and myf5, leading to early myogenic programming.

This PKA–CREB interface may represent a key regulatory node linking non-genomic cortisol actions to gene transcription, as reported in other vertebrates. From a physiological standpoint, such rapid signaling likely contributes to adaptive responses during acute stress, promoting the activation of myogenic progenitors and facilitating tissue remodeling. The functional relevance of these findings lies in the potential role of non-genomic cortisol signaling as an adaptive mechanism during acute stress, where conditions such as crowding, hypoxia, or handling may trigger a rapid activation of myogenic programs that support muscle plasticity and repair, thereby buffering against stress-induced damage [49]. Conversely, chronic cortisol exposure is known to impair muscle growth through sustained genomic and catabolic pathways [22]. The complementary action of non-genomic signaling may therefore fine-tune the balance between proliferation and differentiation, optimizing muscle function in fluctuating environments. This duality highlights the complexity of corticosteroid regulation in teleosts and has implications for aquaculture, where stress management is critical for growth performance and welfare.

5. Conclusions

This study provides mechanistic evidence that cortisol, through a non-genomic pathway, rapidly activates the PKA–CREB signaling cascade in rainbow trout skeletal muscle, leading to the early and transient upregulation of pax3 and myf5. These findings expand the classical view of cortisol action by revealing its capacity to fine-tune myogenic responses beyond genomic and epigenomic regulation. The results highlight the importance of rapid cortisol signaling as a potential adaptive mechanism during acute stress, supporting satellite cell activation and early myogenic programming. This work opens new perspectives for understanding muscle plasticity and stress resilience in fishes, with possible applications in aquaculture to optimize growth and welfare under fluctuating environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.V. and A.M.; methodology, C.F. and J.E.A.; software, R.Z.; validation, J.A.V., R.Z. and C.F.; formal analysis, C.F.; investigation, R.Z.; resources, J.A.V.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.V. and G.D.U.; writing—review and editing, J.A.V. and G.D.U.; visualization, A.M. and P.D.; supervision, J.A.V. and P.D.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, J.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT) under grant numbers 1201498 and 1230794 (to Juan Antonio Valdés), 11230153 (to Phillip Dettleff); the Concurso de Apoyo a Centros de Excelencia en Investigación FONDAP 2023 1522A0004 and 2024 1523A0007 grants (to Alfredo Molina and Juan Antonio Valdés). Rodrigo Zuloaga also acknowledges the support received from ANID-Subdirección de Capital Humano Doctorado Nacional 2023 (Ph.D. scholarship 21230070) and Concurso de Iniciación a la Investigación de la Universidad Andres Bello 2024 (INI UNAB 2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the bioethics committee of the Andrés Bello University and the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research of the Chilean government (protocol code 012/2023, approval date: 14 April 2023) and adhered to animal welfare procedures and the approved protocol.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT 4.0 (https://chat.openai.com/) (accessed on 21 September 2025) to edit English orthography, grammar, and redaction in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HPI axis | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Interrenal axis |

| MRFs | Myogenic Regulatory Factors |

| myf5 | Myogenic factor 5 |

| pax3 | Paired box gene 3 |

| GRE | Glucocorticoid Response Elements |

| GR | Glucocorticoid Receptor |

| MR | Mineralocorticoid Receptor |

| CREB | cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

References

- Johnston, I.A.; Bower, N.I.; Macqueen, D.J. Growth and the Regulation of Myotomal Muscle Mass in Teleost Fish. J. Exp. Biol. 2011, 214, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Messina, G. Comparative Myogenesis in Teleosts and Mammals. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 3081–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manneken, J.D.; Dauer, M.V.P.; Currie, P.D. Dynamics of Muscle Growth and Regeneration: Lessons from the Teleost. Exp. Cell Res. 2022, 411, 112991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescan, P.Y. Regulation and Functions of Myogenic Regulatory Factors in Lower Vertebrates. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 130, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhan, Z.P.; Cho, Y.; Hossen, S.; Cho, D.H.; Kho, K.H. Molecular Characterization, Expression Analysis, and CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Gene Disruption of Myogenic Regulatory Factor 4 (MRF4) in Nile Tilapia. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 13725–13745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, J.M.; Galt, N.J.; Charging, M.J.; Meyer, B.M.; Biga, P.R. In Vitro Indeterminate Teleost Myogenesis Appears to Be Dependent on Pax3. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2013, 49, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Hernández, J.M.; García-González, E.G.; Brun, C.E.; Rudnicki, M.A. The Myogenic Regulatory Factors, Determinants of Muscle Development, Cell Identity and Regeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Tsai, H.J. Myogenic Regulatory Factors Myf5 and Mrf4 of Fish: Current Status and Perspective. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 73, 1872–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.; Relaix, F. PAX3 and PAX7 as Upstream Regulators of Myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 44, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akolkar, D.B.; Asaduzzaman, M.d.; Kinoshita, S.; Asakawa, S.; Watabe, S. Characterization of Pax3 and Pax7 Genes and Their Expression Patterns during Different Development and Growth Stages of Japanese Pufferfish Takifugu rubripes. Gene 2016, 575, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, C.L.; Hinits, Y.; Osborn, D.P.S.; Minchin, J.E.N.; Tettamanti, G.; Hughes, S.M. Signals and Myogenic Regulatory Factors Restrict Pax3 and Pax7 Expression to Dermomyotome-like Tissue in Zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2007, 302, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, S.; You, J.; Liu, R.; Xu, D.; Huang, Q.; Ma, H.; Yin, T. A Comprehensive Review of the Mechanisms on Fish Stress Affecting Muscle Qualities: Nutrition, Physical Properties, and Flavor. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2024, 23, e13336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, L.; Angarica, L.; Hauser-Davis, R.; Quinete, N. Cortisol as a Stress Indicator in Fish: Sampling Methods, Analytical Techniques, and Organic Pollutant Exposure Assessments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluru, N.; Vijayan, M.M. Stress Transcriptomics in Fish: A Role for Genomic Cortisol Signaling. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2009, 164, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoul, B.; Vijayan, M.M. Stress and Growth. In Fish Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 167–205. ISBN 978-0-12-802728-8. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B.; Rai, U. Genomic and Non-Genomic Effect of Cortisol on Phagocytosis in Freshwater Teleost Channa punctatus: An in Vitro Study. Steroids 2009, 74, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aedo, J.E.; Zuloaga, R.; Bastías-Molina, M.; Meneses, C.; Boltaña, S.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Early Transcriptomic Responses Associated with the Membrane-Initiated Action of Cortisol in the Skeletal Muscle of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Physiol. Genom. 2019, 51, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aedo, J.E.; Fuentes-Valenzuela, M.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Quantitative Proteomics Analysis of Membrane Glucocorticoid Receptor Activation in Rainbow Trout Skeletal Muscle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2019, 32, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena-Canales, D.; Aedo, J.E.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Regulation of the Early Expression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 through Membrane-Initiated Cortisol Action in the Skeletal Muscle of Rainbow Trout. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 253, 110565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, M.B.; Aedo, J.E.; Zuloaga, R.; Valenzuela, C.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Cortisol Induces Reactive Oxygen Species Through a Membrane Glucocorticoid Receptor in Rainbow Trout Myotubes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aedo, J.E.; Zuloaga, R.; Boltaña, S.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Membrane-Initiated Cortisol Action Modulates Early Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 2 (Pdk2) Expression in Fish Skeletal Muscle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2019, 233, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, C.A.; Ponce, C.; Zuloaga, R.; González, P.; Avendaño-Herrera, R.; Valdés, J.A.; Molina, A. Effects of Crowding on the Three Main Proteolytic Mechanisms of Skeletal Muscle in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.A. Metyrapone: Basic and Clinical Studies. In Encyclopedia of Stress; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 730–733. ISBN 978-0-12-373947-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faught, E.; Aluru, N.; Vijayan, M.M. The Molecular Stress Response. In Fish Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 113–166. ISBN 978-0-12-802728-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zuloaga, R.; Garrido, C.; Ahumada-Langer, L.; Galaz, J.L.; Ugarte, G.D.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Cortisol-Induced Chromatin Remodeling and Gene Expression in Skeletal Muscle of Rainbow Trout: Integrative ATAC-Seq and RNA-Seq Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relaix, F.; Zoglio, V.; Chebouti, S.; De Lima, J.E.; Lafuste, P. Regulation and Function of Pax3 in Muscle Stem Cell Heterogeneity and Stress Response. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, T.; Toyono, T.; Inoue, A.; Matsubara, T.; Kawamoto, T.; Kokabu, S. Factors Regulating or Regulated by Myogenic Regulatory Factors in Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadmiel, M.; Cidlowski, J.A. Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling in Health and Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aedo, J.E.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; Martínez-Rodríguez, G.; Boltaña, S.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A.; Mancera, J.M. Contribution of Non-Canonical Cortisol Actions in the Early Modulation of Glucose Metabolism of Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata). Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindia, L.; Murray, J.; Faught, E.; Davis, T.L.; Leonenko, Z.; Vijayan, M.M. Novel Nongenomic Signaling by Glucocorticoid May Involve Changes to Liver Membrane Order in Rainbow Trout. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, K.P.; Restall, C.J.; Brain, P.F. Steroid Hormone-Induced Effects on Membrane Fluidity and Their Potential Roles in Non-Genomic Mechanisms. Life Sci. 2000, 67, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borski, R.J.; Hyde, G.N.; Fruchtman, S.; Tsai, W.S. Cortisol Suppresses Prolactin Release through a Non-Genomic Mechanism Involving Interactions with the Plasma Membrane. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 129, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lösel, R.; Feuring, M.; Wehling, M. Non-Genomic Aldosterone Action: From the Cell Membrane to Human Physiology. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 83, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeneweg, F.L.; Karst, H.; De Kloet, E.R.; Joëls, M. Rapid Non-Genomic Effects of Corticosteroids and Their Role in the Central Stress Response. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 209, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.; Rout, M.K.; Wildering, W.C.; Vijayan, M.M. Cortisol Modulates Calcium Release-Activated Calcium Channel Gating in Fish Hepatocytes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.; Faught, E.; Vijayan, M.M. Cortisol Rapidly Stimulates Calcium Waves in the Developing Trunk Muscle of Zebrafish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 520, 111067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray Hamidie, R.D.; Yamada, T.; Ishizawa, R.; Saito, Y.; Masuda, K. Curcumin Treatment Enhances the Effect of Exercise on Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle by Increasing cAMP Levels. Metabolism 2015, 64, 1334–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, W.A.; Gonçalves, D.A.; Graça, F.A.; Andrade-Lopes, A.L.; Bergantin, L.B.; Zanon, N.M.; Godinho, R.O.; Kettelhut, I.C.; Navegantes, L.C.C. Activating cAMP/PKA Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Suppresses the Ubiquitin-Proteasome-Dependent Proteolysis: Implications for Sympathetic Regulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 117, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindia, L.; Faught, E.; Leonenko, Z.; Thomas, R.; Vijayan, M.M. Rapid Cortisol Signaling in Response to Acute Stress Involves Changes in Plasma Membrane Order in Rainbow Trout Liver. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E1157–E1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Bambah-Mukku, D.; Pollonini, G.; Alberini, C.M. Glucocorticoid Receptors Recruit the CaMKIIα-BDNF-CREB Pathways to Mediate Memory Consolidation. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Tabebordbar, M.; Iovino, S.; Ciarlo, C.; Liu, J.; Castiglioni, A.; Price, E.; Liu, M.; Barton, E.R.; Kahn, C.R.; et al. A Zebrafish Embryo Culture System Defines Factors That Promote Vertebrate Myogenesis across Species. Cell 2013, 155, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeaux, R.; Hutchins, C. Anabolic and Pro-Metabolic Functions of CREB-CRTC in Skeletal Muscle: Advantages and Obstacles for Type 2 Diabetes and Cancer Cachexia. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Perry, B.D.; Espinoza, D.; Zhang, P.; Price, S.R. Glucocorticoid-Induced CREB Activation and Myostatin Expression in C2C12 Myotubes Involves Phosphodiesterase-3/4 Signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.E.; Ginty, D.D.; Fan, C.-M. Protein Kinase A Signalling via CREB Controls Myogenesis Induced by Wnt Proteins. Nature 2005, 433, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandurangan, M.; Moorthy, H.; Sambandam, R.; Jeyaraman, V.; Irisappan, G.; Kothandam, R. Effects of Stress Hormone Cortisol on the mRNA Expression of Myogenenin, MyoD, Myf5, PAX3 and PAX7. Cytotechnology 2014, 66, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, C.; Thraya, M.; Vijayan, M.M. Nongenomic Cortisol Signaling in Fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2018, 265, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravena-Canales, D.; Valenzuela-Muñoz, V.; Gallardo-Escarate, C.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Responses to Cortisol-Mediated Stress in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).