Abstract

White croaker (Pennahia argentata) is an ecologically and economically relevant fish species targeted by demersal trawls using diamond-mesh codends at fishing grounds in China, Japan, and Korea. However, the stock has been overexploited, and the capture of undersized individuals is of concern. Further, diamond-mesh codends are known to have varying mesh shape due to the fact that the opening angle in them varies along the codend and during the fishing process. Therefore, to fully understand the effect of mesh size and opening angle on the size selectivity of white croaker, experimental fishing trials and fall-through trials were conducted. By combining the results from these trials, a model was constructed to predict the effect of mesh size and mesh opening angle on size selectivity of white croaker. The predicted size selectivity results for white croaker fitted well with those from the sea trial experiments, which enabled us to use the model established to predict the size selectivity of diamond-mesh codends with a mesh size ranging from 15 to 90 mm and the effect on the exploitation pattern of the species in the fishery by changing the codend mesh size.

Key Contribution:

A comprehensive model was constructed to predict the size selectivity of diamond-mesh codends for white croaker. Our study will be beneficial in fishery management in the studied area.

1. Introduction

China is the largest contributor of marine capture fisheries. In 2024, 9.6 million tons of wild fish was reported in China [1]. Of these, white croaker (Pennahia argentata) is one of the most important species, and it is mostly captured with demersal trawls with diamond-mesh codends [2]. As a national target species of demersal trawl fisheries in China, the total catch volume of white croaker was 98,061 t, of which 29,730 t was from the South China Sea (SCS), in 2024 [1]. This figure, however, has been declining from 109,471 t a decade ago, in 2014 [3]. In addition to the decline in annual catch production, some studies demonstrated that the stock of white croaker had been overexploited [4,5,6]. The overexploitation of stocks could be attributed to many factors. Of these, poor exploitation patterns in the fishing gear used could be the most important one, since the retention of undersized white croaker was reported to be high [7,8].

To address the issue of overexploitation of fish stock, some management regulations have been formulated in China. For instance, two relevant policies, the mesh size of fishing gears and minimum landing size (MLS) at 15.0 cm total length for white croaker, have been established to protect its resources in demersal trawl fisheries. Specifically, the minimum mesh size (MMS) in the codend is 25 mm for trawls targeting shrimp, for those whose target species are fish of 40 mm in the SCS and 54 mm in other fishing areas, such as the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea. These regulations have been in force for more than a decade; however, their effectiveness has sometimes been questioned or criticized due to low compliance and poor understanding of size selectivity [8,9,10]. One problem is that the size selectivity in a diamond-mesh codend is not well-defined because it is made of flexible netting, leading to the shape of the codend meshes varying during the fishing process and along the codend [11,12,13,14]. Specifically, it is the mesh opening angle (OA) that varies in value and affects the shape of the diamond mesh. Moreover, the mesh size and its OA determine the sizes of fish that can escape through it [15]. The mesh OA is affected by several factors that make it vary along the codend and during the trawling process. It has been found that the OA of a diamond-mesh codend depends on the force distribution over the netting and the resistance of the netting to either close or open the meshes [16,17]. As the catch builds up the meshes in the codend, it tends to stretch along the codend, reducing the total number of meshes available for escape [12]. In front of the catch, the twines in the meshes will be subjected to forces in multiple directions and make the meshes open more. There are a few rows of open meshes just in front of the bulbous-shaped catch accumulation, where the majority of the fish in the codend tend to escape [11,12,18]. The position and OAs of the meshes naturally vary in response to a catch build-up [14]. As demonstrated above, to fully understand the size selectivity of a species in diamond-mesh codends, it is essential to understand and quantify the effect of mesh OA on it.

However, few research works have been conducted to evaluate the effect of codend mesh size on size selectivity of white croaker, and none address the effect of mesh OA. Only two studies have been found to investigate the size selectivity of trawl codends for this species in the SCS. In the first one, Yang et al. [19] tested six diamond-mesh codends with a mesh size from 25 to 54 mm and found that the size selectivity was poor for all codends tested and the discard ratio was more than 97%. In the second, Yang et al. [20] compared the size selectivity of two diamond-mesh codends with T90 codends (diamond-mesh turned by 90°) with mesh sizes of 30 and 35 mm, respectively. Their results showed that using the T90 codends would improve size selectivity for white croaker with a length less than 8.5 cm but had little effect for individuals whose length ranged between 10 and 15 cm.

Therefore, this study aimed to (i) understand and predict the effect of mesh size and mesh OA on the mesh release potential of white croaker; (ii) understand and predict codend size selectivity for white croaker dependent on codend mesh size.

2. Materials and Methods

To fulfil the aim of the study, two methods were used and combined: (i) experimental fishing trials with different codends to obtain their size selectivity for white croaker; (ii) fall-through experiments with fresh white croaker individuals to test their ability to pass through diamond-mesh templates with different mesh sizes and mesh OAs.

Experimental data were collected for white croaker over three cruises onboard the commercial trawler ‘Guibeiyu 96899’ (38 m long and 280 kW). On the first cruise, size selectivity data of six diamond-mesh codends were collected in October 2019, while on the second cruise, which was conducted in November 2020, selective data of two diamond-mesh and two T90 codends were collected. On the third cruise, a fall-through experiment was carried out in November 2020. On these three cruises, the fishing experiments were restricted to the same fishing grounds in the Beibu Gulf of the northern SCS, N 20°50′–21°11′, E 108°33′–109°31′, in which the water depth ranged from 12 to 34 m.

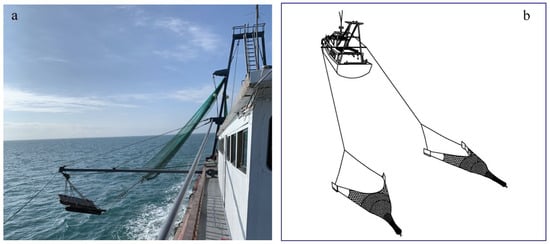

The fishing gears used were the out-rigged trawls, in which two identical trawls were towed simultaneously through the ends of out-rigger derricks (Figure 1). These trawls were spread horizontally with two sets of otter boards, which were made of wood with a rectangular shape. The fishing circle of the trawl used was constructed by 860 diamond meshes, with a mesh size of 45 mm, while the length of the footrope and headline was 36 m and 28 m, respectively. During normal commercial fishing, the headline height of the trawl net would be ~1.5 m and the wingspread was about 15 m. More detailed information about the fishing gears could be found in Yang et al. [19] and Yang et al. [20].

Figure 1.

Fishing gears and fishing vessel in the sea trials. (a) is the trawl rigged in the starboard derrick while (b) shows the whole trawling operation.

2.1. Data Collecting and Analysis for Size Selectivity Experiments

Taking advantage of the out-rigged trawling system, size selectivity experiments were conducted in two consecutive years. Following the protocol of Wileman et al. [18], we used the covered codend method to test the codends. The experimental codends were termed according to their mesh shapes and mesh sizes. Of these, D25, D30, D35, D40, D45, and D54 were diamond-mesh codends with a mesh size ranging from 25 to 54 mm (Table 1). T0-30 and T0-35 were also diamond-mesh codends with different mesh sizes of 30 and 35 mm, respectively, while T90-30 and T90-35 were T90 codends with the same mesh size (Table 1). Specifically, T0 indicates the traditional diamond-mesh codend, while T90 represents the diamond-mesh codends turned by 90 degrees. All the experimental codends were made from the same netting material and had similar twine diameters (Table 1).

Table 1.

Specification of the experimental codends, with mesh opening (MO), twine diameter (TD), mesh number in circumference (MNC), and mesh number in length (MNL). SD represents standard deviation.

Two experimental codends were tested simultaneously in each fishing haul. For instance, D25 and D30 codends were tested at the same time, while T0-30 and T90-30 codends were tested in a similar manner. During each haul, the catches of white croaker from both the tested codend and the covers were separately handled. For some hauls, in which the catch number was huge, we needed to sub-sample. All catches were frozen and taken back for length and weight measurement on land.

The selectivity data could be treated as binomial, since for a given individual of white croaker, it would be either captured by the codend tested or by the cover. For each codend tested, the selectivity data from all hauls were pooled together to estimate the average retention probability (rcodend(l)) for the target species. This retention probability was estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation method, which is analogous to the one used by Yang et al. [19] and Yang et al. [20]. We chose the Logit model to represent rcodend(l, vcodend) as the following equation:

in which L50 is the 50% retention length, while SR represents the selection range, and SR = L75 − L25. The ability of the Logit model to represent the size selectivity data can be judged by the p-values [18]. To account for uncertainties from both within- and between-haul variations, we applied a double-bootstrapping technique, in which 1000 replicates of bootstrap were carried out to estimate the Efron percentile 95% [21] confidence intervals (CIs) of the size selectivity for each codend tested [19,20,22,23].

2.2. Data Collecting and Analysis for Fall-Through Experiment

To fully understand and supplement the selectivity results of the sea trials, a fall-through experiment was conducted under the theoretical framework of FISHSELECT [15]. A sample of white croaker, whose length was distributed over the widest possible range on the third cruise, was collected for this experiment. To minimize the effect of dehydration, rigor mortis, and other related processes that might affect the mesh penetration, five to ten freshly captured white croaker individuals were collected in each fishing haul.

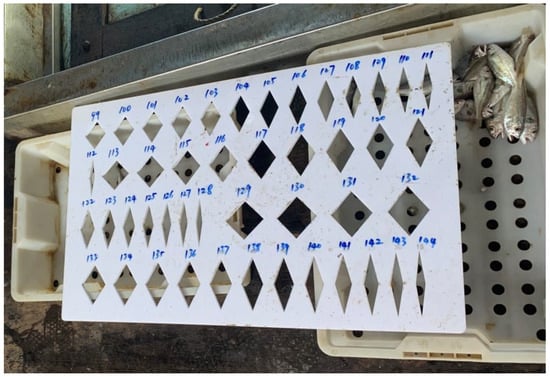

Once the fish was collected, the length of each one was measured to the nearest millimeter before the fall-through experiments. A total of 256 rigid diamond-mesh templates, which were perforated in solid nylon plates, were used. The mesh size (MS) increased from 15 mm to 90 mm with an increment of 5 mm. The opening angles (OAs) ranged from 15 to 90 in increments of 5° (Figure 2). All white croakers were presented at an optimal orientation for penetration through each of the meshes in the templates. The results of penetration (Yes) or retention (No) for each fish were recorded. More details about the procedure of fall-through experiments can be found in Herrmann et al. [15].

Figure 2.

Mesh templates and some white croaker individuals.

The data of fall-through experiments can be treated as covered codend data [18]. We analyzed the data following the procedure described by Herrmann et al. [24] and Bak-Georgsen et al. [25]. Firstly, the Logit model (Equation (1)) was fitted to each mesh template to obtain selectivity parameters. Second, the selective parameters, L50 and SR, their covariance matrix, and the associated values of mesh size (MS) and open angle (OA) were all used to construct the predictive size selectivity model:

in which α1, α2, α3, and α4, and β1, β2, β3, and β4 are model coefficients that need to be estimated. This equation serves the full model, and simpler models can be obtained by leaving out one or more terms in it following the procedure described by Sala et al. [26] and Brčić et al. [27]. Of all the models, the one with the lowest AIC value [28] was selected as the best one to predict the size selectivity.

L50 = α1 × MS × OA + α2 × MS × OA2 + α3 × MS × OA3 + α4 × MS × OA4

SR = β1 × MS × OA + β2 × MS × OA2 + β3 × MS × OA3 + β4 × MS × OA4

SR = β1 × MS × OA + β2 × MS × OA2 + β3 × MS × OA3 + β4 × MS × OA4

2.3. Calibrate the Results of Fall-Through Experiment with the Ones from the Sea Trials

Combining the results from previous sections, we can determine whether the predictive model could be used to reproduce and explain the selectivity results from the sea trial experiments. Considering that the size selectivity from experimental fishing only focused on mesh size, the variations in mesh OAs were unknown. This, however, can be fully addressed by the results of fall-through experiments. We calibrated the results from the fall-through experiments using the selectivity of ten codends, tested via the method described by Herrmann et al. [24,29]. The working principle of this method is to combine single size selectivity curves with different OAs to calculate the contribution of each OA by minimizing a penalty function, which quantified the sum of squares of the deviations [24,30]. For instance, to reproduce the size selectivity of the D25 codend, we first produce a set of size selectivity curves, a total of sixteen, with a mesh size of 25.91 mm and OAs ranging from 15 to 90. Then, we combine these size selectivity curves to quantify the contribution of each OA. Specifically, the contribution of different OAs was estimated through minimizing a penalty function, which quantified the sum square of deviation between the selectivity from the experimental fishing and the one from the fall-through experiment. For more detailed information about this procedure, please refer to Herrmann et al. [24], Krag et al. [30], and Bak-Georgsen et al. [25].

2.4. Predict the Size Selectivity of Diamond-Mesh Codends with Different Mesh Sizes and Mesh OAs

Once the predictive model is found to be able to explain the size selectivity from the sea trials, we can use it to predict the size selectivity of diamond-mesh codends with a larger range of meshes and OAs. The process is analogous to the one described by Herrmann et al. [29] and Krag et al. [25].

2.5. Predicting Exploitation Pattern Indicators of Diamond-Mesh Codends with Different Mesh Size and Mesh OA

Using the predictive size selectivity in the previous section, together with the population structure of white croaker from two sea trials, we can quantify the exploitation pattern indicators of diamond-mesh codends with different mesh sizes and OAs. Here, we focus on two indicators, the catch efficiency of target-sized white croaker (nP+), and discard ratio of undersized individuals (dnRatios). More details about this procedure can be found in Yang et al. [19] and Yang et al. [20].

The data from sea trials and fall-through experiments were analyzed using the SELNET and FISHSELECT software [15,23,24]. R [31] was applied to build the plots using the ggplot2 package [32].

3. Results

3.1. Size Selectivity from the Sea Trials

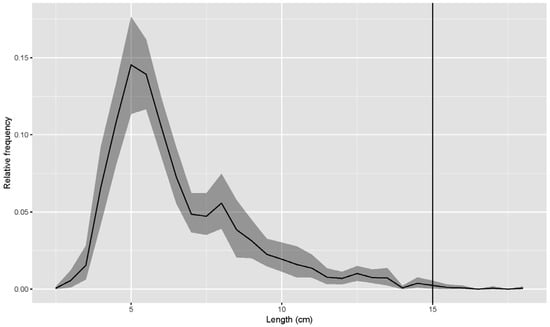

A total of 81 valid hauls were conducted in the sea trials. In the first trial, seven hauls were carried out for the D25, D45, and D54 codends, and eight hauls were carried out for the rest of the codends. In the second trial, nine hauls were replicated for each codend tested. These replicate hauls provided us with a sufficient number of white croakers for further selectivity analysis. In total, 1720 individuals of white croaker were included to estimate the size selectivity of the codends tested. By pooling the length data of the sampled fish, we obtained an averaged size structure of this species. The length of the sampled individuals ranged from 2.5 to 18 cm, with two mode lengths, one at 5 cm and the other at 8 cm (Figure 3). Considering the MLS value, most of the individuals retained were juvenile, at more than 99%.

Figure 3.

Averaged size structure of white croaker based on the experimental data from the sea trials. Shaded areas represent the confidence intervals while the vertical black line is the MLS of white croaker.

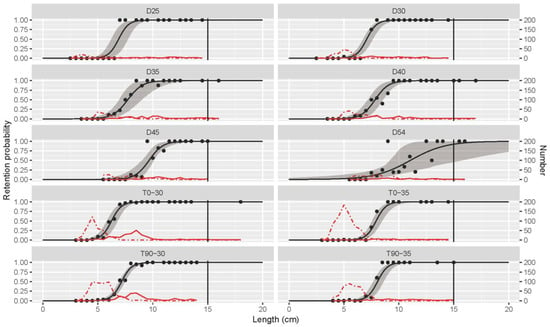

Based on the experimental data from the sea trials, we estimated the size selectivity parameters using the Logit model, which presented a good fit to the data as high p-values were obtained for all codends except the D54 codend (Table 2). As the size selectivity and its confidence intervals fitted well with the experimental retention probability (Figure 4), we concluded that this low p-value of the D54 codend was due to over-dispersion in the experimental data.

Table 2.

Model fits and selectivity parameters estimated from the sea trials. Values in the bracket are 95% confidence intervals. DOF represents degree of freedom.

Figure 4.

Size selectivity curves for each codend tested in the sea trials. Black curves are the size selectivity, while the shaded areas are confidence intervals. Black dots are the experimental retention probability. Red dashed lines are the length of fish retained by the cover, while the red lines are the length of fish retained by the codends. Vertical black lines represent the MLS of white croaker.

In general, the selectivity parameters, both L50 and SR, would increase as the mesh sizes of codends enlarge. For instance, for the D25 codend, L50 and SR were 6.89 and 1.00 cm, while the relative value increased to 11.05 and 3.51 cm, respectively, for the D54 codend. The L50 values of the D45 and D54 codend were significantly larger than those for the codends with smaller mesh sizes. The confidence intervals of L50 and SR for the D54 codend, however, were relatively wider, which indicates uncertainties in the size selectivity. Compared with the diamond-mesh codends, the T90 codends would yield larger L50 values. However, only the difference between the T90-30 and T0-30 codend was statistically significant. The patterns of size selectivity are also presented through the selectivity curves (Figure 4).

3.2. Size Selectivity from the Fall-Through Experiments

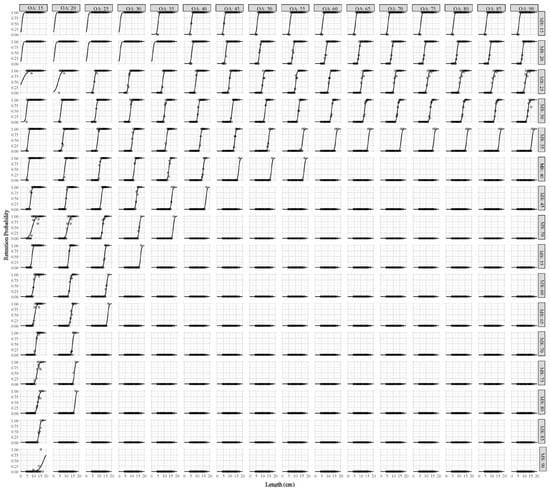

A total of 113 white croaker individuals were included in the fall-through experiments. The length of these fish ranged from 4.5 to 17.5 cm. Multiplying the mesh template with varying mesh sizes and opening angles, we obtained a total of 28,928 fall-through data. Applying the Logit model, the basic selectivity parameters could be estimated (Figure 5). Using these selectivity parameters, L50 and SR, a predictive model was constructed to simulate the size selectivity of white croaker dependent on the mesh size and mesh opening of the codends used. Based on the full model, a total of 256 models were tested, and finally the best model was selected as follows (Table 3):

L50 = α1 × MS × OA + α3 × MS × OA3 + α4 × MS × OA4

SR = β1 × MS × OA + β2 × MS × OA2 + β3 × MS × OA3 + β4 × MS × OA4

Figure 5.

The size selectivity curves from fall-through experiments for white croaker. The circles represent the retention probability while the fitted lines are the size selectivity. MS is the mesh size (in mm), and OA is the mesh opening (in degrees).

Table 3.

Results of fitting the best model for the data from fall-through experiments; 95% C.I.: 95% confidence intervals.

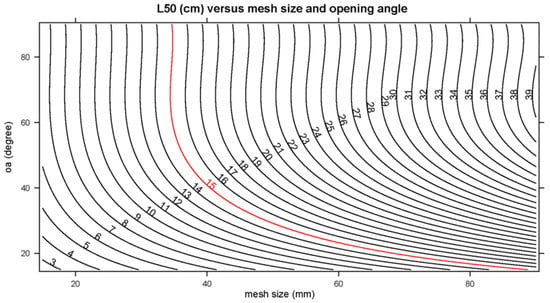

Based on the best model, design guides of iso-curves of L50 were established to present the effect of mesh size and mesh opening on the size selectivity of the codends used (Figure 6). These curves showed that the predicted values of L50 depend on both the mesh size and mesh opening. When the mesh opening is low, increasing the mesh size has little effect on the value of L50. A maximum value of L50 would be reached at ~39 cm when the mesh opening equals to 62°. Above this specific mesh opening value, increasing the value of OA has little effect on further improving the value of L50.

Figure 6.

Design guides predicting the iso-curves of L50 based on the mesh sizes and mesh opening. The red line represents the specific mesh sizes and mesh opening required to obtain an L50 value equal to the MLS of the target species (15.0 cm).

3.3. Ability of the Fall-Through Size Selectivity to Explain the Results from the Sea Trials

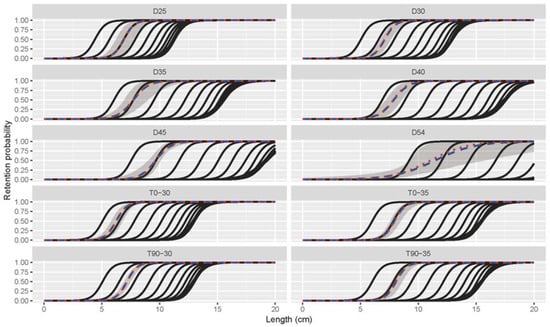

By combining the simulated selectivity curves with mesh opening from 15 to 90 degrees, it is possible to reproduce the size selectivity curves for all codends tested in the sea trials (Figure 7). The combination of different mesh opening angles (OAs) shows that the largest contribution to the size selectivity was provided by meshes with OAs between 15 and 30 degrees for both diamond-mesh and T90 codends (Table 4). These three OAs contributed more than 84% of all codends tested. For the six diamond-mesh codends tested in the first sea trials, OAs larger than 30 degrees showed a low contribution to size selectivity, except that the OA of 90 degrees accounted for 8.76% of the D54 codend. Specifically, the OA of 25 degrees accounted for more than 69%, while the OA of 20 degrees contributed over 60% for the D30, D35, and D45 codend, respectively. For the D40 and D54 codend, the OAs of 15 and 20 degrees shared more than 44% of the contribution. In the second sea trial, the contribution of OAs dominated at 20 and 25 degrees for the T90 tested (Table 4). For the T0-30, T0-35, and T90-35 codend, the OA of 20 degrees contributed more than 68%, while the OA of 20 and 25 degrees showed a contribution higher than 48% (Table 4).

Figure 7.

Simulated and experimental selectivity curves for the codends tested in the sea trials. The back curves represent the simulated selectivity based on mesh opening (OA) from 15 to 90 degrees. The red dotted lines represent the selectivity from the sea trials while the shaded areas are their confidence intervals. The blue dashed curves are the size selectivity based on contributions of different OAs.

Table 4.

Weighted contribution of the simulated selectivity curves for codends tested with a mesh opening angle (OA) from 15 to 90.

By accounting for the contributions of different OAs, we can reproduce the size selectivity for the sea trial data (Figure 7). The simulated selectivity curves were overlapping with, or very close to, the ones from the experimental data. These curves enable us to explain the results from the sea trials in a better way.

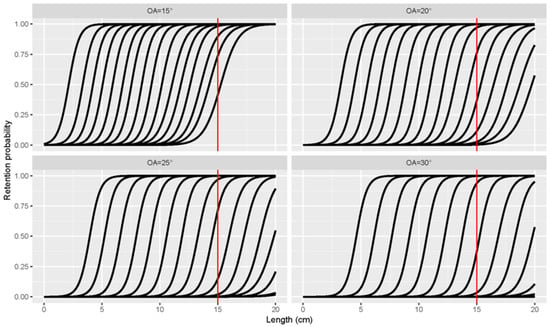

3.4. Predicting the Effect of Mesh Size and Mesh Opening on the Size Selectivity of White Croaker

Based on the results in the previous section, it was found that the contribution of OA was mainly dominated by 15, 20, 25, and 30 degrees, respectively, to reproduce the size selectivity of experimental data from the sea trials. Using the best predicted model, size selectivity of mesh size ranging from 15 to 90 mm could be predicted under four scenarios of different OA contributions (Table 5 and Figure 8). In general, the size selectivity parameters, both L50 and SR, would increase as the mesh size enlarges, while larger OAs would have bigger selectivity parameters.

Table 5.

Predicted selectivity parameters, L50 and SR in cm, for mesh sizes (MSs) ranging from 15 to 90 mm under four OA scenarios, from 15 to 30 degrees.

Figure 8.

Predicting size selectivity for codends with mesh sizes ranging from 15 to 90 mm under four different mesh opening (OAs): 15, 20, 25, and 30 degrees. Vertical red lines represent the MLS of white croaker.

3.5. Predicting the Effect of Mesh Size and Mesh Opening on the Exploitation Pattern of White Croaker

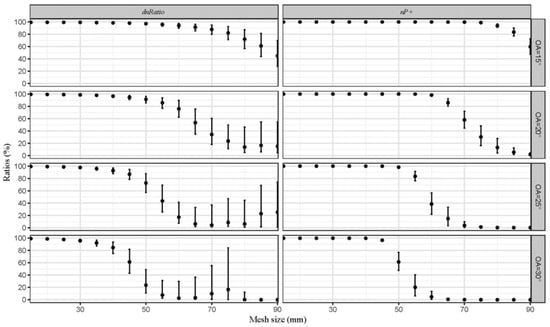

Both exploitation pattern indicators, dnRatio and nP+, reduce when the mesh sizes of codends increase under four mesh openings (OAs). For individuals above MLS, full retention was observed for codends with mesh sizes less than 50 mm, which then reduced with mesh size. A similar trend was observed for the catch efficiency of individuals under MLS, while their confidence intervals were wider, indicating larger uncertainties (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Exploitation pattern indicators predicted for codends with mesh sizes ranging from 15 to 90 mm, with mesh openings (OAs) of 15, 20, 25, and 30 degrees, respectively.

4. Discussion

Using the framework of FISHSELECT, an indirect method is established to quantify the effect of mesh size and opening angle on the size selectivity of white croaker for demersal trawl fisheries for the first time. This method enables us to understand the selective properties of codends previously tested in the sea trials and provides comprehensive design guides and exploitation pattern indicators for the species investigated. Our prediction of size selectivity curves fitted well with the ones experimentally obtained from the sea trials. These results further demonstrated the robustness of the FISHSELECT framework to predict the size selectivity of trawl in a simple way. The FISHSELECT method has been widely used to conduct selectivity studies for many fish species [15,23,33,34,35], crustaceans [27,36,37], and crab species [24]. These studies, however, are limited mainly to some European countries. Our study demonstrates the application of FISHSELECT method for white croaker in China and shows good results for size selectivity study.

Despite its relevance and wide distribution, the selectivity study for white croaker is still limited. Only three formal studies are found in the literature for this species in China, one conducted by Tang et al. [38] with a stow net and the other two for demersal trawl fisheries by Yang et al. [19] and Yang et al. [20]. The research priority of these three studies is common. They all focused on how the mesh sizes used in the codends would affect the size selectivity of white croaker. Our study moves forward by investigating the effect of the mesh opening angle. The contribution of OAs to size selectivity can enable us to understand the differences in selective properties between the codends tested. For instance, the retention probability of the D54 codend was significantly lower than any other diamond-mesh codends, according to the study of Yang et al. [19]. This can be partly explained by the contribution of OA of 90 degrees, which was ~9% in the D54 codend compared with other codends. Another comparison made by Yang et al. [20] showed that the T90-30 codend had significantly lower retention probability for some individuals in a specific length range, while the difference between the T90-35 and T0-35 codend was insignificant. This can also be explained by the contribution of OA in the present study, as the T90-30 codend had a significantly larger contribution with an OA of 25 degrees than the T0-30 codend, while the difference in contribution of OAs between T0-35 and T90-35 was insignificant (Table 4). For all the codends tested, why the contribution of OAs to selectivity is mainly constrained to 15 to 30 degrees is a question that still needs further investigation.

The experimental data from sea trials were analyzed by Yang et al. [19] and Yang et al. [20], using four candidate models, Logit, Probit, Gompertz, and Richards, respectively. The Logit model was only chosen as the best model for two codends tested, T0-30 and T90-30. From completeness, consistency, and simplicity viewpoints, we selected the Logit model for both the experimental and simulation data. By comparing with the previous studies, our analysis also provided a good model fit for the experimental data. For one thing, the size selectivity fitted close to the experimental retention probability; for the other, the selectivity parameters, both L50 and SR, and p-values were very close to those found by Yang et al. [19] and Yang et al. [20]. For instance, for the D35 codend, Yang et al. [19] chose the Gompertz as the best model and obtained L50 and SR as 7.52 (CI: 6.78–8.84) cm and 1.65 (CI: 0.84–2.87) cm; in the present study, the relative values were 7.72 (CI: 6.95–9.01) cm and 1.47 (CI: 1.00–2.42) cm. In addition, our method made it better to reproduce the size selectivity of sea trials by using the simulation of fall-through experiments.

In general, the best way to optimize the size selectivity for trawl fisheries is to modify the value of L50 to MLS and sharpen the size selectivity by reducing the value of SR for the target species [39]. Our study will shed light on how to improve the size selectivity of a demersal fishery for white croaker. For one thing, when the mesh opening angle is low, for instance, 15 or 20 degrees, the mesh size needs to be as large as 90 or 70 mm to obtain an L50 close to the MLS. In comparison, only a mesh size of 50 mm could achieve an L50 larger than the MLS when the mesh opening is 30 degrees (Table 5). For the other, our study showed that when the mesh size and/or mesh opening increase, the value of SR will increase. Especially, when the mesh size is larger than 50 mm, confidence intervals of selectivity parameters were relatively larger, indicating uncertainties. Thus, our study demonstrated that manipulating the minimum mesh size in the codend is not enough. The effect of mesh opening should be taken into account both in scientific research and regulatory action.

Our study has some implications for the MMS regulation for trawl fisheries in China. For shrimp trawl fisheries, the retention risk of white croaker will be high if it is a by-catch species due to the fact that only 25 mm of MMS is required. For demersal fisheries targeting fish species, the MMS needs to be 40 mm in the South China Sea and 54 mm in the East and Yellow Sea. Considering that the mesh opening angle may be limited to between 15 to 30 degrees, values of L50 for codends with a mesh size of 40 mm are still smaller than 15.0 cm. In comparison, if the mesh size increases to 50 or 55 mm and mesh opening is kept to 30 degrees, the codends used will show values of L50 larger than 15.0 cm. Some experts in China suggest that the MMS regulation of 40 mm for trawl fisheries targeting fish should be revised to 54 mm. This comes from some personal communications. Based on the prediction of our study, a codend with a mesh size of 54 mm will have a value of L50 larger than 15.0 cm only when the mesh opening is kept constant at 30 degrees. The problem facing the scientific community is how to manufacture such a codend. Fortunately, there are some studies presenting good examples of achieving this. For instance, Bak-Jensen et al. [40,41] have successfully kept the OAs of diamond-mesh codends larger than 30 degrees. These examples will provide direction for future selectivity studies in China.

Our study also demonstrates the flexibility of FISHSELECT to establish predictive models of size selectivity for fish species. Some relevant factors, however, have not been taken into account in this model. For instance, the effect of contacting mode and ability to squeeze in the process of mesh penetration should be taken seriously [15]. In addition, though white croaker is an economic species for demersal trawl fisheries in all coastal areas in China, a selectivity study for this species from both sea trial and simulation perspectives, has not been conducted other than in the South China Sea. To address this, more comprehensive research work should be conducted.

5. Conclusions

We established a method to quantify the effect of mesh size and opening angle on the size selectivity of white croaker for demersal trawl fisheries. The predicted size selectivity results of white croaker fitted well with those from the sea trials experiments, which enabled us to use the model established to predict the size selectivity of diamond-mesh codends with mesh sizes ranging from 15 to 90 mm and the effect on the exploitation pattern of the species in a fishery by changing the codend mesh size.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y.; methodology, B.Y. and B.H.; software, B.H.; validation, B.Y.; formal analysis, B.Y. and B.H.; investigation, B.Y.; resources, B.Y.; data curation, B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y.; writing—review and editing, B.Y. and B.H.; visualization, B.Y. and B.H.; supervision, B.H.; project administration, B.Y.; funding acquisition, B.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD2400702) and financial support from Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs ‘Standard and management regime of fishing gears in the South China Sea’.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (protocol code 48/2020 and approval date: 10 September 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lei Yan, Jie Li, Teng Wang, and Yongguang Tan for their help with the sea cruises and length measurement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MLS | minimum landing size |

| MMS | minimum mesh size |

| MS | mesh size |

| OA | opening angle |

| D25 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 25 mm |

| D30 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 30 mm |

| D35 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 35 mm |

| D40 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 40 mm |

| D45 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 45 mm |

| D54 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 54 mm |

| T0-30 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 30 mm |

| T0-35 | the diamond mesh codend with a mesh size of 35 mm |

| T90-30 | the T90 codend with a mesh size of 30 mm |

| T-90-35 | the T90 codend with a mesh size of 35 mm |

References

- MARA. Chinese Fishery Yearbook 2025; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2025. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wu, H. A Study on the Classification of the Sciaenoid Fishes of China, with Description of New Genera and Species; Shanghai Science Technology Publication: Shanghai, China, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- MARA. Chinese Fishery Yearbook 2015; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Kume, G.; Higuchi, T.; Takita, T. Geographic variation in the growth of white croaker, Pennahia argentata, off the coast of northwest Kyushu. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2004, 71, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Haung, Z. Estimation of growth and mortality parameters of Argyrosomus argentatus in northern South China Sea. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2005, 16, 712–716. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Liu, M.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Han, C.; Chen, S. Fisheries in Chinese seas: What can we learn from controversial official fisheries statistics? Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2018, 28, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, P. Analysis of the catch composition of small shrimp-beam-trawl net in shallow waters of Pearl River Estuary, China. South China Fish. Sci. 2008, 4, 70–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, M.; Sadovy de Mitcheson, Y.; Cao, L.; Leadbitter, D.; Newton, R.; Little, D.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Fishing for feed in China: Facts, impacts and implications. Fish Fish. 2020, 21, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Pauly, D. Growth and mortality of exploited fishes in China’s coastal seas and their uses for yield-per-recruit analyses. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2017, 33, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y.; Hansons, A.; Huang, B.; Leadbitter, D.; Little, D.; Pikitch, E.; Qiu, Y.; Sadovy de Mitcheson, Y.; et al. Opportunity for marine fisheries reform in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B. Effect of catch size and shape on the selectivity of diamond mesh cod-ends: I. model development. Fish. Res. 2005, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B. Effect of catch size and shape on the selectivity of diamond mesh cod-ends II. Theoretical study of haddock selection. Fish. Res. 2005, 71, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.; O’Neill, F.G. Theoretical study of the between-haul variation of haddock selectivity in a diamond mesh cod-end. Fish. Res. 2005, 74, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, F.G.; Herrmann, B. PRESEMO—A predictive model of codend selectivity—A tool for fishery managers. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2007, 64, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B.; Krag, L.; Frandsen, R.; Madsen, N.; Lundgren, B.; Stæhr, K. Prediction of selectivity from morphological conditions: Methodology and a case study on cod (Gadus morhua). Fish. Res. 2009, 97, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B.; Priour, D.; Krag, L.A. Simulation-based study of the combined effect on cod-end size selection of turning meshes by 90° and reducing the number of meshes in the circumference for round fish. Fish. Res. 2007, 84, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priour, D. Introduction of mesh resistance to opening in a triangular element for calculation of nets by the finite element method. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2001, 17, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wileman, D.; Ferro, R.S.T.; Fonteyne, R.; Millar, R.B. Manual of Methods of Measuring the Selectivity of Towed Fishing Gear. ICES Coop. Res. Rep. 1996, 215, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Herrmann, B.; Yan, L.; Li, J.; Wang, T. Effects of six diamond codend meshes on the size selection of juvenile white croaker (Pennahia argentata) in the demersal trawl fishery of the South China Sea. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253723. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Herrmann, B.; Wan, R. Comparing the size selectivity and exploitation patterns of two T0 codends with T90 codends in demersal trawl fishery targeting white croaker (Pennahia argentata) of the northern South China Sea. J. Sea Res. 2024, 199, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. The Jackknife, the Bootstrap and Other Resampling Plans; SIAM Monograph No. 38; CBSM-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, R.B. Incorporation of between-haul variation using bootstrapping and nonparametric estimation of selection curves. Fish. Bull. 1993, 91, 564–572. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, B.; Sistiaga, M.; Nielsen, K.; Larsen, R. Understanding the Size Selectivity of Redfish (Sebastes spp.) in North Atlantic Trawl Codends. J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 2012, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B.; Grimaldo, E.; Brčić, J.; Cerbule, K. Modelling the effect of mesh size and opening angle on size selection and capture pattern in a snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) pot fishery. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 201, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak-Georgsen, Z.; Herrmann, B.; Melli, V.; Santos, J.; Feekings, J. Understanding and predicting codend size selection for flatfish species. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2025, 35, 1445–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.; Herrmann, B.; De Carlo, F.; Lucchetti, A.; Brčić, J. Effect of codend circumference on the size selection of square-mesh codends in trawl fisheries. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brčić, J.; Herrmann, B.; Mašanović, M.; Šifnera, S.; Škeljoa, F. CREELSELECT—A method for determining the optimal creel mesh: Case study on Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus) fishery in the Mediterranean Sea. Fish. Res. 2018, 204, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B.; Krag, L.; Feekings, J.; Noack, T. Understanding and Predicting Size Selection in Diamond-Mesh Cod Ends for Danish Seining: A Study Based on Sea Trials and Computer Simulations. Mar. Coast. Fish. Dyn. Manag. Ecosyst. Sci. 2016, 8, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krag, L.; Herrmann, B.; Frandsen, R. Effect of codend mesh size on size selectivity and catch efficiency of common sole (Solea solea). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 89, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krag, L.; Herrmann, B.; Madsen, N.; Frandsen, R. Size selection of haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) in square mesh codends: A study based on assessment of decisive morphology for mesh penetration. Fish. Res. 2011, 110, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokaç, A.; Herrmann, B.; Gökhan, G.; Krag, L.; Nezhad, D.; Lök, A.; Kaykac, H.; Aydın, C.; Ulas, A. Understanding the size selectivity of red mullet (Mullus barbatus) in Mediterranean trawl codends: A study based on fish morphology. Fish. Res. 2016, 174, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkhof, J.; Sistiaga, M.; Herrmann, B.; Bak-Jensn, Z.; Jacques, N. Understanding and predicting size selectivity of saithe (Pollachius virens) in trawl codends. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2025, 35, 1383–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, R.; Herrmann, B.; Madsen, N. A simulation-based attempt to quantify the morphological component of size selection of Nephrops norvegicus in trawl codends. Fish. Res. 2010, 101, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krag, L.; Herrmann, B.; Iversen, S.; Engas, A.; Nordrum, S.; Krafft, B. Size Selection of Antarctic Krill (Euphausia superba) in Trawls. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yang, B.; Sun, G.; Huang, L.; Liang, Z. Selectivity of codend mesh of double stake stow net in Qingdao offshore, Yellow Sea. J. Fish. Sci. China 2010, 17, 1327–1333. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Graham, N. Technical measures to reduce bycatch and discards in trawl fisheries. In Behaviour of Marine Fishes: Capture Processes and Conservation Challenges; He, P., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2010; pp. 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bak-Jensen, Z.; Herrmann, B.; Santos, J.; Jacques, N.; Melli, V.; Feekings, J. Fixed mesh shape reduces variability in codend size. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 79, 1820–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak-Jensen, Z.; Herrmann, B.; Santos, J.; Jacques, N.; Melli, V.; Feekings, J. The capability of square-meshes and fixed-shape meshes to control codend size selection. Fish. Res. 2023, 264, 106704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).