Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) in the Gulf of America

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Processing Otoliths for Ageing

2.3. Ageing Otoliths

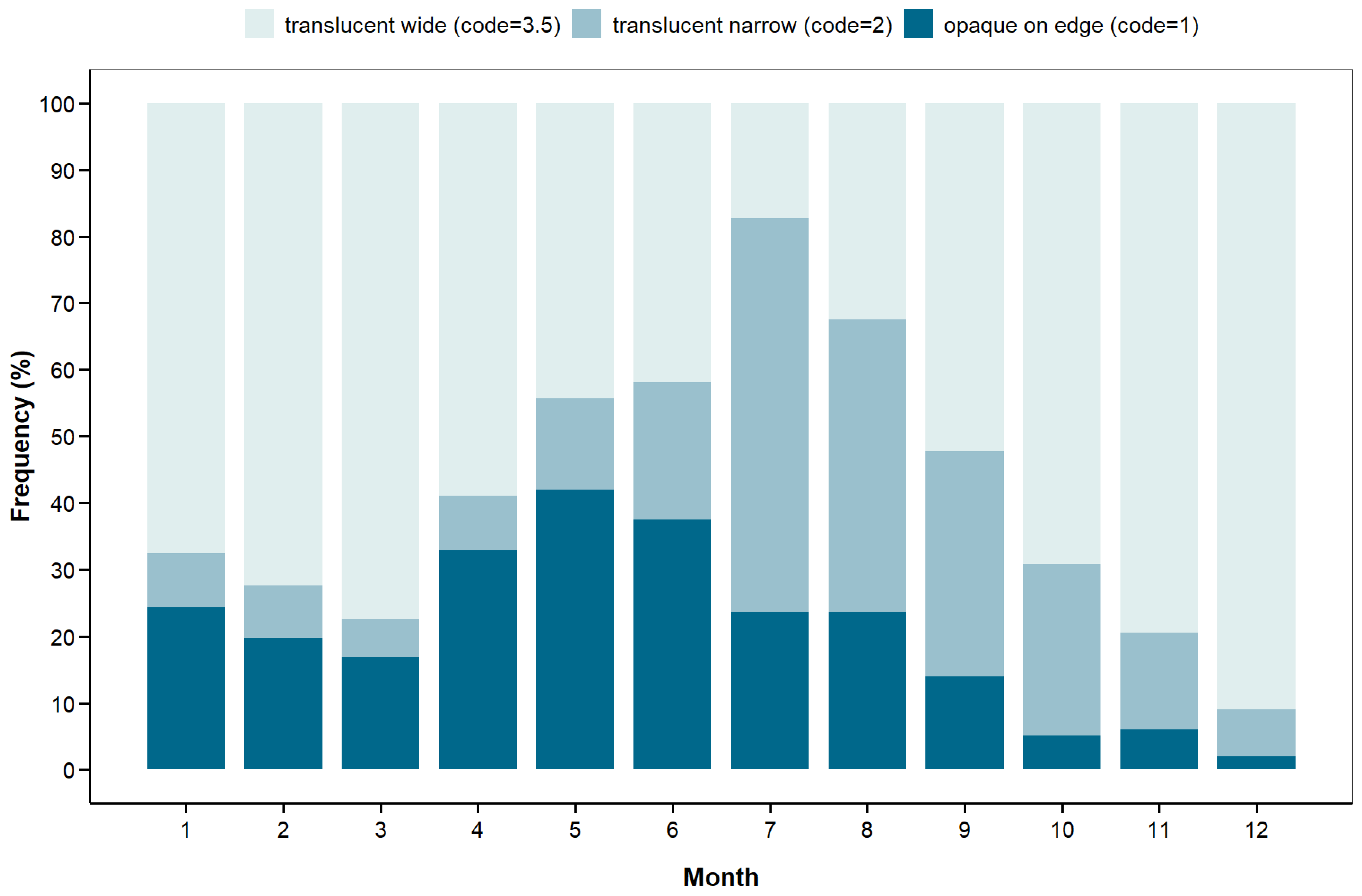

2.4. Indirect Validation of Otolith Ageing Method

2.5. Growth Models

3. Results

3.1. Fish Samples

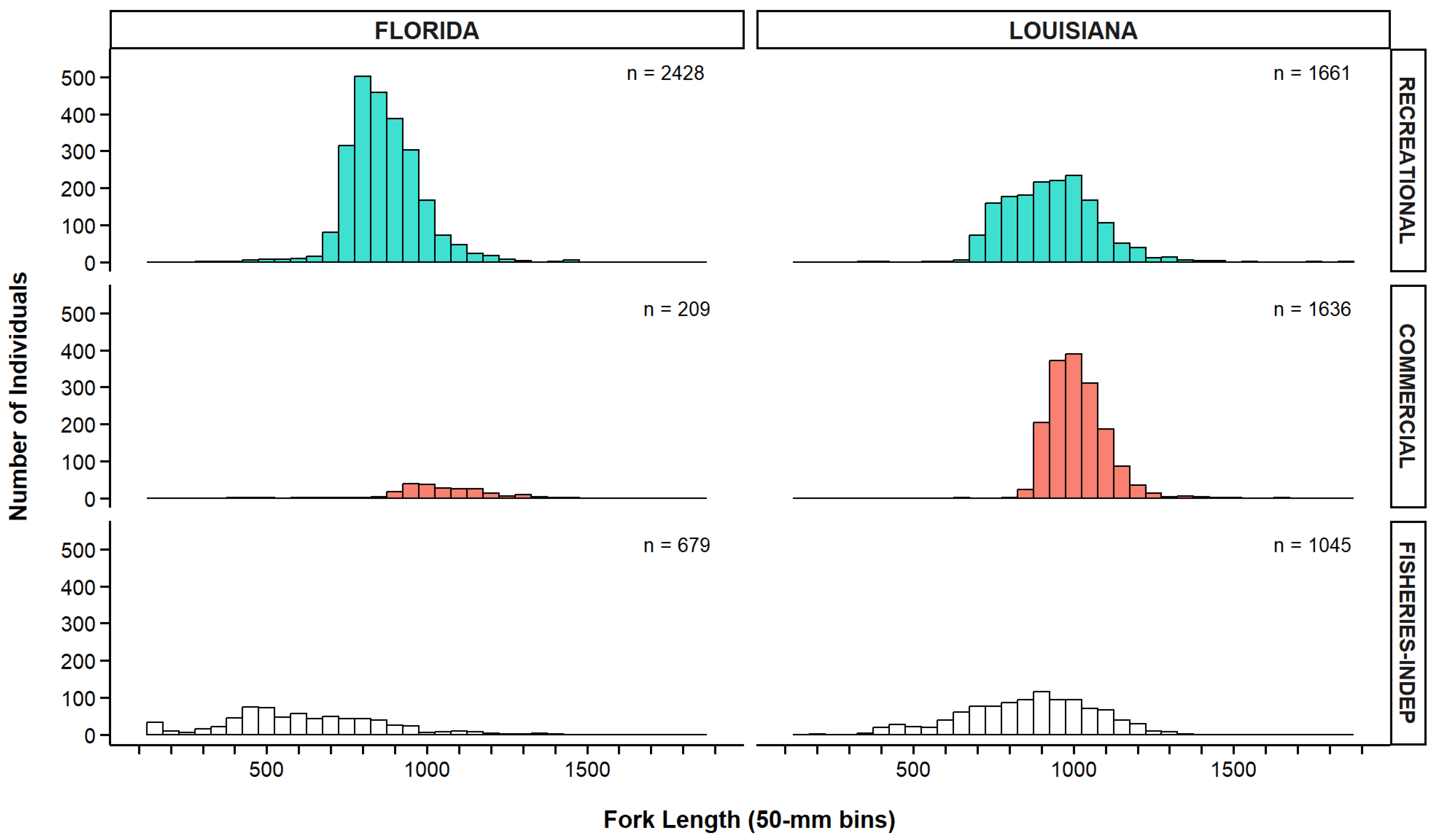

3.2. Length Distributions of Greater Amberjack

3.3. Length–Weight Relationships

3.4. Indirect Validation of Otolith Ageing Method

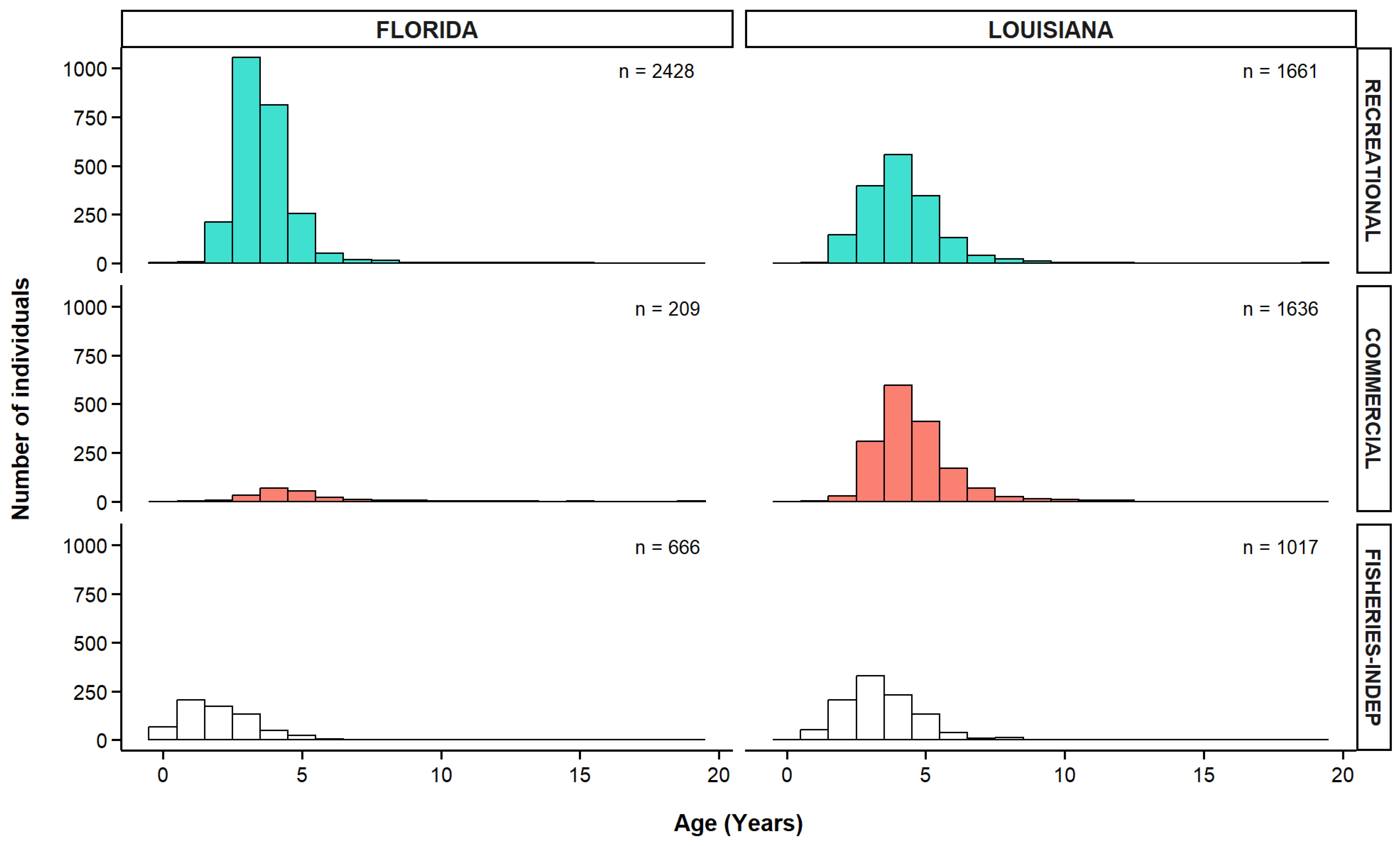

3.5. Age Distribution of Greater Amberjack

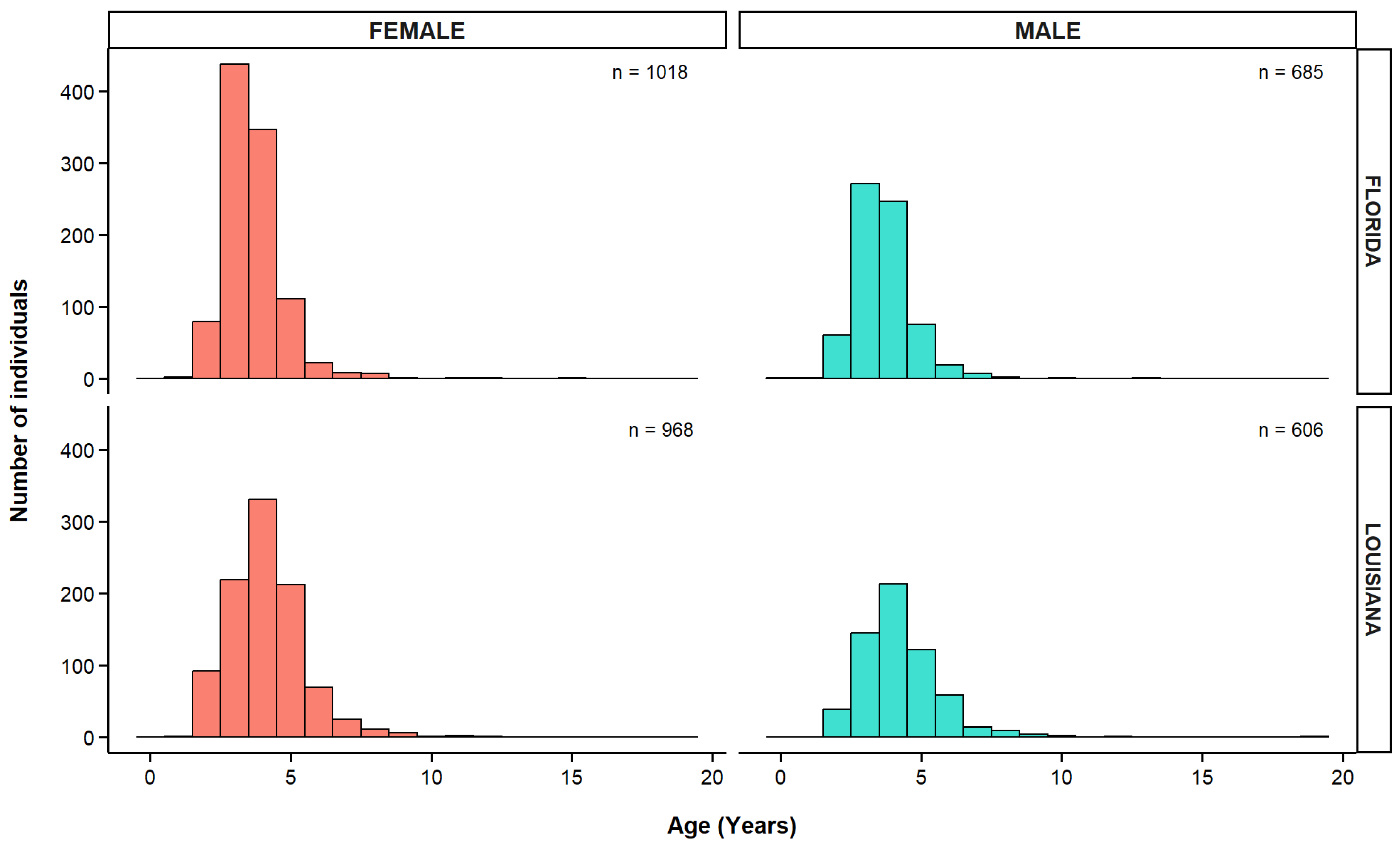

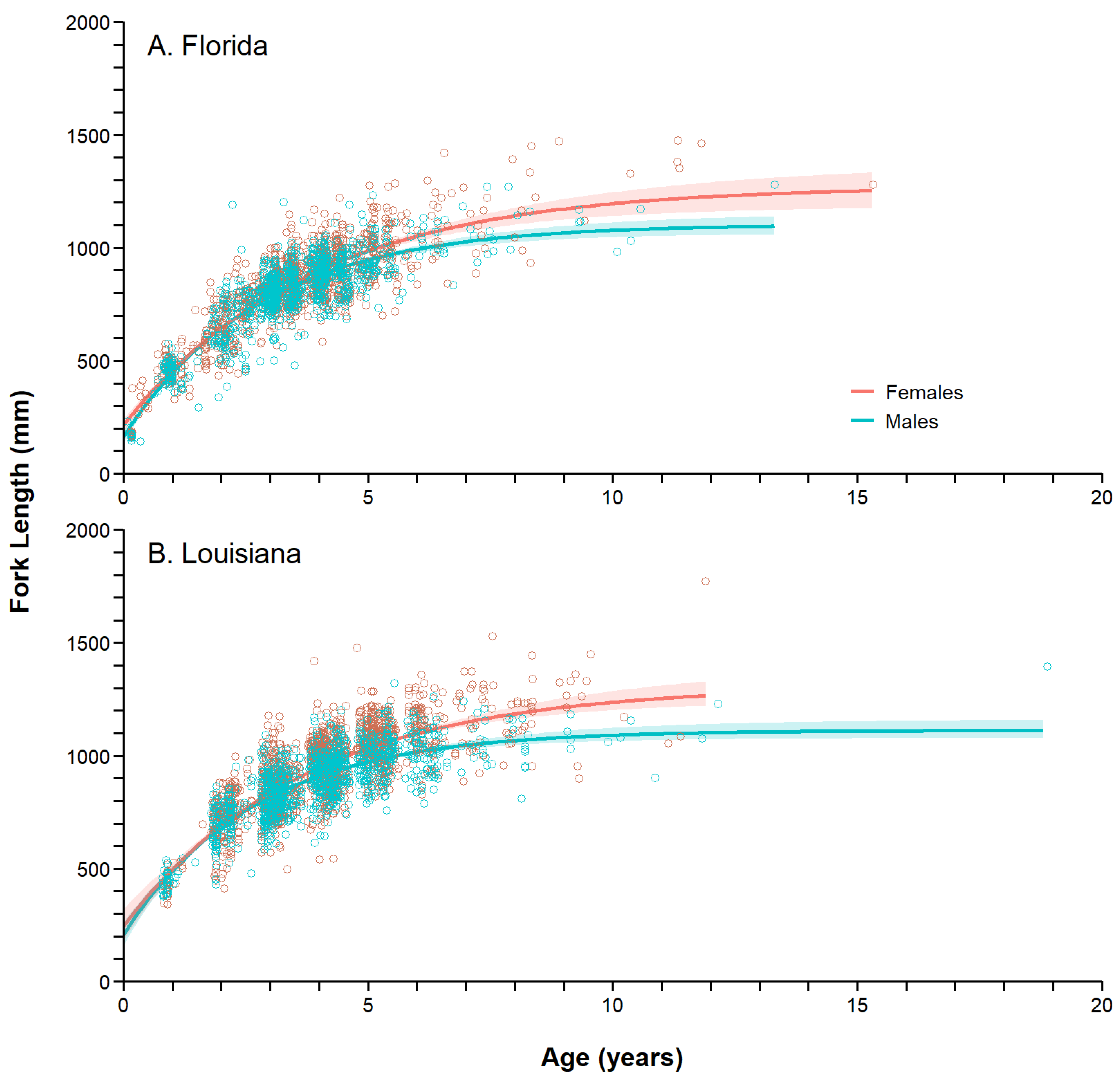

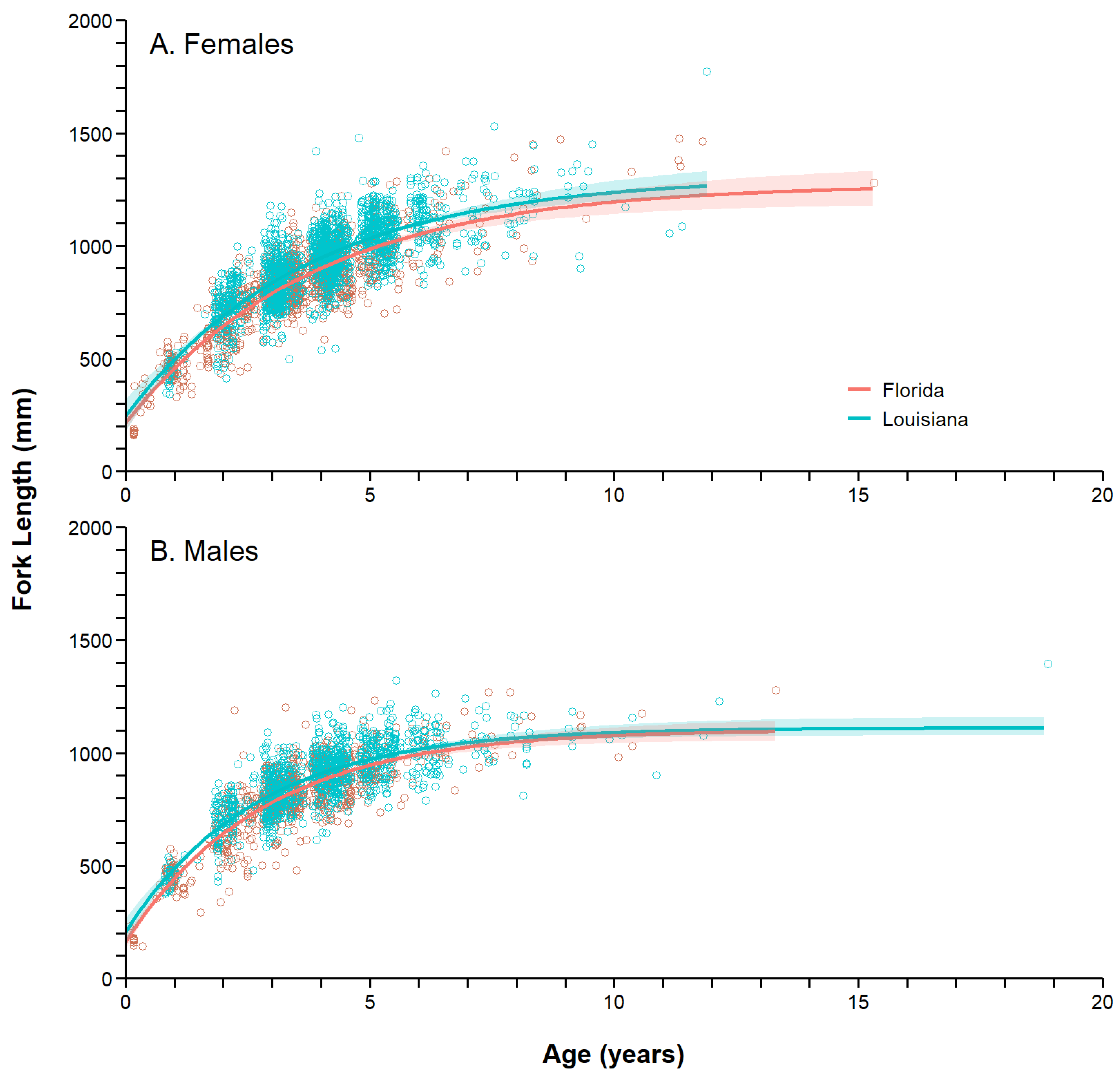

3.6. Growth Models

| Model | K | AICc | ΔAICc | AICc Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Von Bertalanffy | 4 | 92,028.29 | 0 | 1 |

| Gompertz | 4 | 92,133.10 | 104.81 | 0 |

| Logistic | 4 | 92,262.23 | 233.94 | 0 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SEDAR. SEDAR 70 Stock Assessement Report, Gulf of Mexico Greater Amberjack, Section I: Introduction; SEDAR (Southeast Data, Assessment, and Review): North Charleston, SC, USA, 2020; 33p.

- SEDAR. SEDAR 70 Stock Assessment Report, Gulf of Mexico Greater Amberjack, Section II: Assessment Report; SEDAR (Southeast Data, Assessment, and Review): North Charleston, SC, USA, 2020; 152p.

- NOAA. Recreational Fisheries Statistics Queries, U.S. Department of Commerce. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/data-tools/recreational-fisheries-statistics-queries (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Manooch, C.S.; Potts, J.C. Age, growth, and mortality of greater amberjack, Seriola dumerili, from the U.S. Gulf of Mexico headboat fishery. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1997, 61, 671–683. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B.A.; Beasley, M.; Wilson, C.A. Age distribution and growth of greater amberjack, Seriola dumerili, from the north-central Gulf of Mexico. Fish. Bull. 1999, 97, 362–371. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, M. Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack, Seriola dumerili, from the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Master’s Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Murie, D.J.; Parkyn, D.C. Age, Growth and Sexual Maturity of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) in the Gulf of Mexico; MARFIN Final Report (NA05NMF4331071); University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2008; 39p. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, E. Comparative Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) from Charterboat and Headboast Fisheries of West Florida and Alabama, Gulf of Mexico. Master’s Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Murie, D.J.; Parkyn, D.C.; Smith, G.H.; Allman, R.; Pacicco, A.; Carroll, J.; Smith, N. Gulf of Mexico Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) Growth Model for SEDAR 70 Operational Assessment; Southeast Data Assessment and Review (SEDAR): North Charleston, SC, USA, 2020; p. 18.

- Burch, R.K. The Greater Amberjack, Seriola dumerili: Its Biology and Fishery off Southeastern Florida. Master’s Thesis, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Manooch, C.S.; Potts, J.C. Age, growth and mortality of greater amberjack from the southeastern United States. Fish. Res. 1997, 30, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.J.; Wyanski, D.M.; White, D.B.; Mikell, P.P.; Eyo, P.B. Age, growth, and reproduction of greater amberjack off the southeastern U.S. Atlantic coast. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2007, 136, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamish, R.J.; McFarlane, G. Current trends in age determination methodology. In Age and Growth of Fish; Summerfelt, R.C., Hall, G.E., Eds.; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1987; pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, R.L. Carangidae: Greater amberjack. In Fishery Atlas of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands; Uchida, R.N., Uchiyama, J.H., Eds.; NOAA Technical Report NMFS 38; U. S. Department of Commerce: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1986; pp. 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Jover, M.; García-Gómez, A.; Tomás, A.; De la Gándara, F.; Pérez, L. Growth of Mediterranean yellowtail (Seriola dumerilii) fed extruded diets containing different levels of protein and lipid. Aquaculture 1999, 179, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicuro, B.; Luzzana, U. The state of Seriola spp. other than yellowtail (S. quinqueradiata) farming in the world. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2016, 24, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaloro, F.; Potoschi, A.; Porrello, S. Contribution to the knowledge or growth of greater amberjack, Seriola dumerili (Civ., 1817) in the Sicilian Channel (Mediterranean Sea). In Proceedings of the CIESM Congress, Trieste, Italy, 12–16 October 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kožul; Skaramuca; Kraljević; Dulčić; Glamuzina. Age, growth and mortality of the Mediterranean amberjack Seriola dumerili (Risso 1810) from the south-eastern Adriatic Sea. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2001, 17, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.J.; Chin, A.; Tobin, A.J.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Multimodel approaches in shark and ray growth studies: Strengths, weaknesses and the future. Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 955–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinn, S.A.; Midway, S.R. Trends in growth modeling in fisheries science. Fishes 2021, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA Fisheries Southeast Regional Office. History of Management of Gulf of America Red Snapper. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/sustainable-fisheries/history-management-gulf-america-red-snapper (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Pacicco, A.E.; Allman, R.J.; Lang, E.T.; Murie, D.J.; Falterman, B.J.; Ahrens, R.; Walter, J.F. Age and growth of yellowfin tuna in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2021, 13, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murie, D.J.; Parkyn, D.C.; Fischer, A. Is the BOFFF (Big Old Fat Fecund Females) Hypothesis Applicable to Gulf of Mexico Greater Amberjack? MARFIN Final Report (NA15NMF4330154); University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA; 44p.

- SEDAR. SEDAR 33 Gulf of Mexico Greater Amberjack Stock Assessment Report; SEDAR: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2014; 409p.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- VanderKooy, S.; Carroll, J.; Elzey, S.; Gilmore, J.; Kipp, J. (Eds.) A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes, 3rd ed.; Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission; the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission: Ocean Springs, MS, USA, 2020.

- Beamish, R.J.; Fournier, D.A. A method for comparing the precision of a set of age determinations. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1981, 38, 982–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.J. AquaticLifeHistory: Fisheries Life History Analysis Using Contemporary Methods. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/jonathansmart/AquaticLifeHistory (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Akaike, H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In International Symposium on Information Theory; Petrov, B.N., Csaki, F., Eds.; Akademiai Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1973; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mazerolle, M.J. AICcmodavg: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference Based on (Q)AIC(c), R Package Version 2.3.2. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=AICcmodavg (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.J.; Farley, J.H.; Hoyle, S.D.; Davies, C.R.; Nicol, S.J. Spatial and sex-specific variation in growth of albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga) across the South Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, E.M.; Lang, E.T.; Lovell, M.S.; Lang, J.; Falterman, B.J.; Midway, S.R.; Dance, M.A. Age, growth, and mortality of Blackfin Tuna in the Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2024, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.H.; Murie, D.J.; Parkyn, D.C. Nonlethal sex determination of the greater amberjack, with direct application to sex ratio analysis of the Gulf of Mexico stock. Mar. Coast. Fish. Dyn. Manag. Ecosyst. Sci. 2014, 6, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.H.; Murie, D.J.; Parkyn, D.C. Effects of sex-specific fishing mortality on sex ratio and population dynamics of Gulf of Mexico greater amberjack. Fish. Res. 2018, 208, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish Biol. 2001, 59, 197–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fishery | Fishing Mode | Gear | Florida | Louisiana | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Commercial | All | All | 209 | 6.3 | 1636 | 37.7 | 1845 | 24.1 |

| Hook and Line | 142 | 4.3 | 1436 | 33.1 | 1578 | 20.6 | ||

| Longline | 58 | 1.7 | 38 | 0.9 | 96 | 1.3 | ||

| Spear | 9 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.1 | ||||

| Trawl | 2 | 2 | <0.1 | |||||

| Unknown | 160 | 3.7 | 160 | 2.1 | ||||

| Fisheries-Independent | All | All | 679 | 20.5 | 1045 | 24.1 | 1724 | 22.5 |

| Hook and Line 1 | 648 | 19.5 | 1029 | 23.7 | 1677 | 21.7 | ||

| Longline | 1 | <0.1 | 14 | 0.3 | 15 | 0.2 | ||

| Spear 1 | 24 | 0.7 | 24 | 0.3 | ||||

| Trawl | 6 | 0.2 | 2 | <0.1 | 8 | 0.1 | ||

| Recreational | All | All | 2428 | 73.2 | 1661 | 38.3 | 4089 | 53.4 |

| Charter boat | Total | 1592 | 48.0 | 1225 | 28.2 | 2817 | 36.8 | |

| Charter boat | Hook and Line | 1591 | 48.0 | 1225 | 28.2 | 2816 | 36.8 | |

| Charter boat | Spear | 1 | <0.1 | 1 | <0.1 | |||

| Head boat | Hook and Line | 715 | 21.6 | 66 | 1.5 | 781 | 10.2 | |

| Private | Total | 121 | 3.7 | 370 | 8.5 | 491 | 6.4 | |

| Private | Hook and Line | 92 | 2.8 | 368 | 8.5 | 460 | 6.0 | |

| Private | Spear | 25 | 0.8 | 2 | 27 | 0.4 | ||

| Private | Unknown | 4 | 0.1 | 4 | <0.1 | |||

| TOTAL | Grand total | 3316 | 4342 | 7658 | ||||

| Model | n | Parameters of the Length–Weight Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | r2 | p-Value | ||

| Florida all | 1547 | 0.0000673 (0.0000625–0.0000725) | 2.762 (2.751–2.773) | 0.993 | <0.0001 |

| Louisiana all | 1067 | 0.0000452 (0.0000391–0.0000523) | 2.829 (2.807–2.851) | 0.984 | <0.0001 |

| All | 2614 | 0.0000545 (0.0000624–0.0000723) | 2.797 (2.751–2.773) | 0.990 | <0.0001 |

| State | Sex | n | AICc | ∑AICc | ΔAICc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | Females | 1411 | 16,659.03 | 27,736.49 | 42.39 |

| Males | 941 | 11,077.46 | |||

| Pooled | 2352 | 27,778.88 | |||

| Louisiana | Females | 1673 | 20,306.99 | 32,670.89 | 171.47 |

| Males | 1042 | 12,363.90 | |||

| Pooled | 2715 | 32,842.36 | |||

| Florida | Females | 1411 | 16,659.03 | 36,966.02 | 193.48 |

| Louisiana | Females | 1673 | 20,306.99 | ||

| Both | Females | 3084 | 37,159.50 | ||

| Florida | Males | 941 | 11,077.46 | 23,441.36 | 61.12 |

| Louisiana | Males | 1042 | 12,363.90 | ||

| Both | Males | 1983 | 23,502.48 |

| State | Sex | n | L∞ (mm) | k (year−1) | L0 (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | Females | 1411 | 1272.92 (25.96) | 0.261 (0.013) | 213.97 (13.05) |

| Males | 941 | 1103.94 (19.54) | 0.357 (0.020) | 161.83 (17.76) | |

| Pooled | 3303 | 1213.50 (13.62) | 0.294 (0.009) | 191.63 (9.90) | |

| Louisiana | Females | 1673 | 1308.28 (27.98) | 0.271 (0.020) | 244.44 (29.92) |

| Males | 1042 | 1112.74 (16.62) | 0.374 (0.024) | 206.22 (31.87) | |

| Pooled | 4315 | 1142.24 (7.70) | 0.423 (0.014) | 136.08 (24.24) | |

| Both | Females | 3084 | 1312.29 (18.48) | 0.262 (0.010) | 214.30 (12.90) |

| Males | 1983 | 1111.84 (12.11) | 0.368 (0.014) | 169.28 (15.85) | |

| Pooled | 7617 | 1180.26 (7.10) | 0.352 (0.008) | 161.69 (10.05) |

| Stock | Source | n | Ageing Method | Maximum Age (Years) | Length Type 1 | L∞ (mm) | k (Year−1) | t0 (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean | Andaloro et al. [17] | 1140 | Scales | 9 | SL | 1670 | 0.185 | −0.770 |

| Kožul et al. [18] | 298 | Scales | 10 | TL | 1746 | 0.190 | −0.314 | |

| U.S. South Atlantic | Burch [10] | 432 | Scales | 10 | FL | 1643 | 0.174 | −0.653 |

| Manooch and Potts [11] | 323 | Otoliths | 17 | FL | 1514 | 0.115 | −1.178 | |

| Manooch and Potts [11] | 323 | Otoliths | 17 | TL | 1648 | 0.119 | −1.230 | |

| Harris et al. [12] | 1985 | Otoliths | 13 | FL | 1241 | 0.28 | −1.56 | |

| Gulf of America | Manooch and Potts [4] | 340 | Otoliths | 15 | FL | 1109 | 0.227 | −0.720 |

| Manooch and Potts [4] | 340 | Otoliths | 15 | TL | 1272 | 0.227 | −0.793 | |

| Thompson et al. [5] | 597 | Otoliths | 15 | FL | 1389 | 0.25 | −0.79 | |

| Murie and Parkyn [7] | 1835 | Otoliths | 15 | FL | 1240 | 0.28 | −1.01 | |

| Murie et al. [9] 2 | 6801 | Otoliths | 19 | FL | 1179 | 0.343 | −0.49 | |

| This study 3 | 7617 | Otoliths | 19 | FL | 1180 | 0.352 | 161.69 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murie, D.J.; Parkyn, D.C.; Smith, G.H., Jr.; Leonard, E.; Croteau, A.; Allman, R.; Pacicco, A.; Carroll, J.L.; Falterman, B.J.; Smith, N. Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) in the Gulf of America. Fishes 2025, 10, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120620

Murie DJ, Parkyn DC, Smith GH Jr., Leonard E, Croteau A, Allman R, Pacicco A, Carroll JL, Falterman BJ, Smith N. Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) in the Gulf of America. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):620. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120620

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurie, Debra J., Daryl C. Parkyn, Geoffrey H. Smith, Jr., Edward Leonard, Amanda Croteau, Robert Allman, Ashley Pacicco, Jessica L. Carroll, Brett J. Falterman, and Nicole Smith. 2025. "Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) in the Gulf of America" Fishes 10, no. 12: 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120620

APA StyleMurie, D. J., Parkyn, D. C., Smith, G. H., Jr., Leonard, E., Croteau, A., Allman, R., Pacicco, A., Carroll, J. L., Falterman, B. J., & Smith, N. (2025). Age and Growth of Greater Amberjack (Seriola dumerili) in the Gulf of America. Fishes, 10(12), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120620