Abstract

Effective fisheries management relies on accurate stock assessments to ensure sustainable exploitation and long-term ecosystem stability. Fisheries from the Nile Delta lakes of Egypt—comprising Manzala, Burullus, Edku, and Mariout—are economically critical, collectively contributing about 40% of the nation’s total capture fisheries and are facing severe anthropogenic challenges. This study assessed the stock status of 10 key fish species and two crustacean species from these four Nile Delta lakes by determining their life history parameters and exploitation levels. The analysis included estimation of the Length–Weight Relationship (LWR), von Bertalanffy Growth Function (VBGF) parameters, instantaneous mortality coefficients (Z, M, F), and the exploitation ratio (E). Asymptotic total length (L∞) varied widely, ranging from 10.47 cm for Portunus pelagicus to 86.78 cm for Clarias gariepinus (in Lake Manzala). The growth coefficient (K) spanned from 0.31 yr−1 (C. gariepinus) to 1.79 yr−1 (Metapenaeus stebbingi), reflecting diverse life history strategies. The key finding, based on the Gulland criterion, is that all commercial stocks examined in the Nile Delta lakes are currently subjected to severe overexploitation, with the exploitation ratio (E) consistently exceeding the optimal threshold of 0.5. These results underscore the urgent need for adaptive management strategies, including stricter gear regulations and improved fisheries monitoring, to ensure the sustainability of these vital resources.

Keywords:

exploitation level; fisheries management; Length–Weight Relationship; Nile Delta lakes; overfishing; Tilapia Key Contribution:

This study provides the first comprehensive, multi-lake assessment confirming that all key commercial fish and crustacean stocks in Egypt’s Nile Delta lakes are overexploited. The data highlight an urgent, ecosystem-wide need for adaptive management strategies, including the regulation of fishing effort and gear, to ensure long-term resource sustainability.

1. Introduction

Effective fisheries management is essential for maintaining the sustainability of aquatic ecosystems and ensuring long-term food security [1]. A cornerstone of sustainable management strategies is the accurate assessment of fish stock dynamics, which requires the estimation of critical parameters such as growth rates, mortality and exploitation rates, and maximum sustainable yields (MSY) [2]. Globally, aquatic ecosystems are experiencing significant alterations due to escalating human activities, resulting in biodiversity loss, and coastal ecosystems are particularly vulnerable [3,4,5,6,7]. This instability threatens not only diverse life but also essential ecosystem services like water and fishery resources [8], requiring systematic monitoring and conservation [9,10].

Fishery resources play a significant role in Egypt’s economy and food security, as fish are a vital source of protein that help bridge the national nutritional gap [11]. Furthermore, fish provide essential vitamins, minerals, and amino acids necessary for human health. Therefore, attention is needed for fisheries as a productive activity that can contribute to the development or increase the national income, and as one of the most important sources of protein that should be available in human food [11].

These nationally important resources are heavily concentrated in the coastal region. Along the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, there are five northern coastal lakes/lagoons (the four Nile Delta lakes and Bardawil lake) [12]. These lakes, extending from Bardawil lagoon to Lake Mariout, occupy separate areas totaling about 2314 km2 [12]. The Nile Delta lakes are economically the most important fishing grounds. They provide rich and vital habitat diversity for estuarine and marine fish and their regeneration, making them major areas of fish production. Consequently, these lakes produce over 40% of Egypt’s total fish catch. Moreover, they are globally recognized as important sites for birds, particularly those migrating from and to Africa and Europe [11]. However, like many global aquatic systems, these lakes are inherently vulnerable to multifaceted threats, including invasive species, eutrophication, and hydrological modifications [11].

Specifically, the Egyptian Nile Delta lakes suffer from several serious challenges, such as increased freshwater inflow, eutrophication and pollution, habitat degradation (e.g., shoreline erosion), and high population density in surrounding areas [11]. The Nile delta lakes receive large amounts of freshwater via the working irrigation system, mainly through drainage, which is caused by the expansion of agriculture and aquaculture. These lakes connect several drains to convey their effluents into the water body, often leading to the spreading of aquatic vegetation, which may reduce water exchange through the lakes. Additionally, industrial development and urbanization during the last four decades have led to an increase in serious problems within the lakes [13]. All these environmental impacts cause significant damage to the ecosystem and its living organisms. These environmental changes have reduced commercial fish species’ catch and greatly impacted the local fishery. Furthermore, addressing the sustainability of these crucial resources is further complicated by the fact that they are often characterized as small-scale fisheries (SSFs), which typically face severe data limitations. The reliance of SSFs on limited biological and catch data necessitates the use of cost-effective, data-poor assessment methods to inform management decisions.

Given these data constraints and ecological pressures, particularly overfishing and severe environmental degradation, fish are crucial ecological health indicators [5]. Therefore, this study aims to provide up-to-date scientific information on the age, growth, mortality, and exploitation levels of the key commercial fish species from the four major Nile Delta lakes, providing the specific biological parameters necessary to inform sustainable fisheries management and the conservation of biodiversity in these highly stressed aquatic ecosystems.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

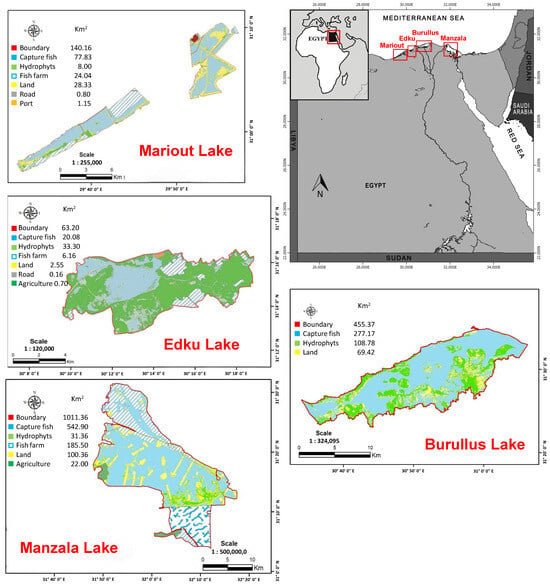

This study focuses on four of the five crucial Northern Lakes located along the Egyptian Mediterranean coast, which form the heart of the Nile Delta’s estuarine system (Figure 1). These four lakes (Nile Delta lakes) are discussed here sequentially from west to east: Lake Mariout, Lake Edku, Lake Burullus, and Lake Manzala.

Figure 1.

Location map of the four studied Nile Delta lakes (also known as Northern lakes) including, from west to east: Lake Mariout, Lake Edku, Lake Burullus, and Lake Manzala. Maps for each lake were adapted from GAFRD annual statistical books [12].

Lake Mariout is the smallest and westernmost of the four. This brackish lake, situated in northern Egypt, is noteworthy for being entirely isolated from the open Mediterranean Sea by the isthmus upon which the city of Alexandria is built. Its current area is significantly diminished to approximately 68.8 km2 (17,000 acres), having been reduced from an original 66,000 acres due to extensive reclamation projects [14,15]. With depths generally ranging from 0.6 to 2.7 m, its fisheries are dominated by Tilapia, specifically Oreochromis niloticus (contributing around 63% of the catch), followed by catfishes (Clarias lazara and C. gariepinus, accounting for about 31%). Moving eastward, Lake Edku is situated approximately 30 km east of Alexandria. This lake has also experienced severe area reduction, losing about 77% of its surface area since 1957, bringing its size down to roughly 16.8 km2 as of 2017 [16]. Its water balance is maintained by two sources: inflow from the Mediterranean Sea via the Boughaz El-Maadeya connection and substantial drainage inputs from the Edku El-Khairy, Bousaly, and Bersik drains, which introduce urban, industrial, and agricultural waters.

Further east lies Lake Burullus, the second largest of the Nile Delta Lakes, centrally located between the Rosetta and Damietta Nile branches. This lake connects directly to the Mediterranean Sea through the El-Boughaz inlet. Lake Burullus is currently recognized as the most productive Egyptian lake, yielding around 104.5 thousand tons in 2022 [12]. Its fisheries are characterized by high species diversity, including salt, brackish, and freshwater species, with the family Cichlidae being the most abundant, closely followed by Mugilidae. The lake’s hydrology is complex, receiving a mix of polluted drainage water from eight drains and supplemental fresh Nile water via the Brenbal Canal. Finally, Lake Manzala is the largest of Egypt’s Nile Delta lakes and one of the most important aquatic ecosystems in the Mediterranean basin. Situated along the northeastern coast, the lake currently spans approximately 572 km2. Despite facing severe degradation challenges [15,16], it remains a critical asset, contributing nearly 14% of Egypt’s total annual fish production [12,15].

2.2. Samples and Data Collection

Samples were collected from the commercial landings during the fishing season in the four studied lakes during the last two years (2023–2024). The sampling procedure was designed to cover the entire fishing area of each lake to adequately capture marine, brackish, and freshwater species. Given the considerable long-term aquaculture activity in these regions, the integrity of the samples was strictly maintained by collecting all specimens directly with local fishermen during standard fishing hours and limiting collection exclusively to the open areas subject to commercial fishing effort. This strict sampling protocol confirmed that all analyzed fish were part of the exploited wild stock and effectively excluded individuals originating from localized, closed aquaculture containment areas.

Collection focused on the most common fishing gears used in the Nile Delta lakes, which include trammel nets (dabba, balla, and kaffaya), basket traps (gawabi), spiral traps (tahaweet-dorra), trawl nets, hooks (sinnar), and collection by hand on foot (kaddamat) [17]. To ensure representativeness, samples were specifically gathered according to the dominant commercial gear types used for each species group: Tilapia species (O. niloticus, S. galilaeus, O. aureus, and C. zillii) were collected from surrounding nets, Clarias gariepinus was gathered from traps, Mullet species (Chelon auratus and Liza ramada) and Solea aegyptiaca were collected from trammel nets, Moronid species (D. punctatus and D. labrax) were collected from lines, while Crustacean species (P. pelagicus and M. stebbingi) were collected from traps and cast nets.

A total of ten fish species and two crustacean species were randomly collected from the studied areas and immediately transported to the laboratory in iced boxes for sorting and measuring. The species collected were: Oreochromis niloticus, Sarotherodon galilaeus, Oreochromis aureus, Coptodon zillii, Clarias garipienus, Chelon auratus, Liza ramada, Dicentrarchus punctatus, Dicentrarchus labrax, Solea aegyptiaca, Metapenaeus stebbingi, and Portunus pelagicus.

A total of 900, 730, 615, 1027, 1350, 650, 655, 830, 745, 500, 1350 and 2325 specimens of O. niloticus, S. galilaeus, O. aureus, C. zillii, C. garipienus, C. auratus, L. ramada, S. aegyptiaca, D. punctatus, D. labrax, P. pelagicus and M. stebbingi, respectively, were used in this study. In the laboratory, Total Length (TL) and Total Weight (W) were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 g, respectively, for each specimen. For subsequent age determination, hard structures were carefully removed and prepared. Otoliths were extracted, cleaned, and preserved in specialized envelopes. Scales were also removed from the left side of each fish, specifically behind the pectoral fin. These scales were placed in a 10% solution of Ammonium hydroxide, then washed with distilled water, dried using filter paper, and finally mounted between two glass slides for examination.

To estimate the relation between total length (L) and total weight (W), the power function of Le Cren (1951): W = a Lb was fitted to the data, where “a” is the intercept and “b” is the slope. The degree of association between the variables was computed by the determination of the regression coefficient r2 and 95% confidence limits of parameters a and b were estimated [18].

In addition, the annual official fish landings for the Nile Delta lakes during the period 2011–2022 were obtained from the General Authority for Fish Resources Development (GAFRD). It is acknowledged that the official recording system possesses inherent limitations, including the aggregation of multiple commercially important species into broad groups (e.g., ‘Tilapia,’ ‘Grey mullet’), and a lack of reliable data on fishing effort and catch rates. These limitations were carefully considered during the interpretation of the results.

2.3. Age, Growth, and Mortality Analysis

2.3.1. Growth Modeling and Age Determination

Growth was then modeled according to the von Bertalanffy Growth Function (VBGF) [19]: Lt = L∞ (1 − ), where Lt is the total length at age t, L∞ is the asymptotic length, K is the growth coefficient, t0 and is the theoretical age when Lt = 0.

Ages for the fish species were determined by counting the growth bands (alternating translucent and opaque bands) in sagittal otoliths and scales. The whole otoliths were immersed in glycerol and examined under reflected light using a compound microscope at magnifications between 10× and 40× against a black background. Otoliths were prioritized for analysis, and the consistency of the otolith interpretation was rigorously determined by the average percentage error (APE) index [20] and the coefficient of variance (CV). After age determination, otolith readings were used for all further analysis. The total otolith radius and the radius of each annulus were measured, and the relationship between the otolith radius (S) and the total length was fitted to estimate the necessary parameters for back calculations and to construct the age composition for the investigated fish species.

The constants L∞ and K were estimated using the plot method from [21,22]. The constant t0 was subsequently calculated using the VBGF rearrangement: ln [1 − (Lt/L∞)] = −Kt0 + Kt [19].

For the Crustacean species (P. pelagicus and M. stebbingi), growth parameters were estimated using the ELEFAN I program incorporated in the FiSAT II software. Initial values for L∞ were obtained using the Powell-Wetherall method [23,24]. This approach was adopted because these length-based methods remain the most feasible and robust tools for analyzing data from complex, multi-species, data-limited small-scale fisheries (SSFs). While acknowledged as potentially subjective, these methods provided the essential and comparable parameters necessary for the primary exploitation analysis, as the available data lacked the continuous, age-structured time series required by more statistically demanding modern approaches.

2.3.2. Mortality, Exploitation Rates and Stock Status

The total mortality coefficient (Z) was estimated using two distinct methods: the Length-Converted Catch Curve (LCCC) method (Pauly, 1983) [25] and the Hoenig method (1982, 1984) [26,27], which utilizes maximum age (tmax). The Z value reported was taken as the arithmetic mean of the two estimates, a decision made to obtain a robust, central value and to mitigate the potential statistical bias associated with relying solely on any one empirical method for a diverse, multi-stock assessment.

The natural mortality coefficient (M) was calculated as the geometric mean of three different empirical methods: Ursin’s method (1967) [28], the Rikhter and Efanov’s Empirical Model (1976) [29], and the Empirical formula of Pauly (1980) [30]. The geometric mean was selected as the final M estimate because all three approaches are purely statistical and their integration provides a more stable, normalized central tendency to better reflect natural conditions. The fishing mortality coefficient (F) was then derived by subtracting the natural mortality from the total mortality: F = Z − M.

Finally, the exploitation ratio (E) was estimated using Gulland’s formula (1971): E = F/Z. Stock status was evaluated not only by comparing E to the general 0.5 threshold, but also by comparing estimates of the fishing mortality rate (F) with target (Fopt) and limit (Flimit) Biological Reference Points (BRPs), which were defined as: Fopt = 0.5 M and Flimit = 2/3 M (Patterson, 1992) [31]. Additionally, the Z/K ratio was used to indicate the stock status in this study, where a ratio exceeding two is considered a sign of overexploitation (Etim et al., 1999) [32]. According to [33], a stock is considered optimally fished when fishing mortality (F) equals natural mortality (M), underexploited if E < 0.5, and overexploited if E > 0.5.

In addition, the dynamic nature of the Nile Delta lakes and their resident fish populations necessitates a continuous comparison of current findings with historical data to track long-term trends and environmental impacts. To facilitate this comparison, a literature review was conducted to compile previously reported Length–Weight Relationship and key Population dynamics parameters for the dominant Oreochromis species and C. gariepinus from the Egyptian northern lakes. Finally, to provide essential context for the current assessment, the estimated growth, mortality, and exploitation parameters derived from the most recent literature pertaining to the Nile Delta lakes were summarized. This comparative approach facilitates a comprehensive evaluation of long-term trends and the current stock status relative to historical and regional data.

3. Results

3.1. Annual Landings and Catch Composition

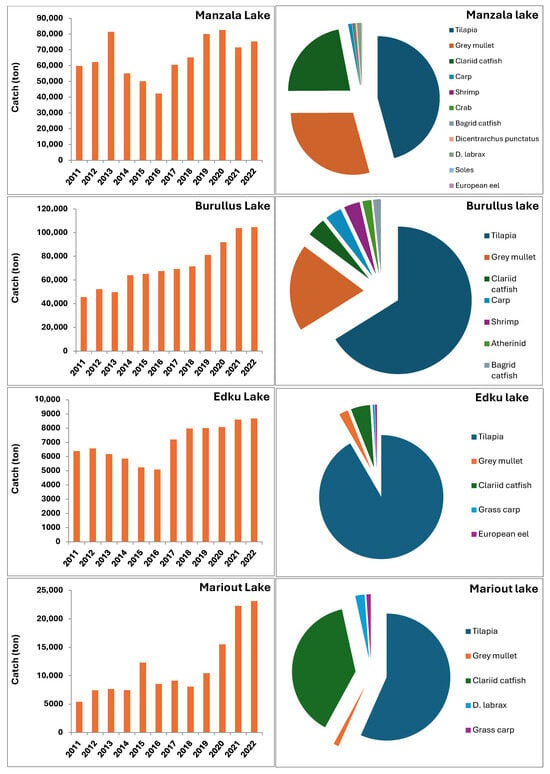

Official annual fish landings from the Nile Delta lakes showed considerable fluctuation during the period from 2011 to 2022. Figure 2 visually presents these catch fluctuations in the four Delta lakes over the 2011–2022 period, along with the average contribution of different fish groups and species to the total catch during the same time. Lake Burullus exhibited the highest variability, with annual catches fluctuating between 45.5 and 104.5 thousand tons, averaging 72.2 thousand tons. Lake Manzala followed, with landings varying between 42.3 and 82.5 thousand tons, averaging 65.2 thousand tons. The two smaller lakes showed lower overall yields: Lake Mariout averaged 11.4 thousand tons (ranging from 7.5 to 23.1 thousand tons), and Lake Edku averaged 7.0 thousand tons (ranging from 5.1 to 8.7 thousand tons).

Figure 2.

Annual total fish catch fluctuation (tons) in the four Nile Delta lakes (Manzala, Burullus, Edku, and Mariout) during the period from 2011 to 2022 (Bar Charts), and the average contribution of different fish groups and species to the total catch for each lake over the same period (Pie Charts). Data for each lake were sourced from GAFRD annual statistical books [12].

A detailed breakdown of the 2022 catch data for different fish groups and crustaceans from the four Nile Delta lakes is provided in Table 1. The results show that the catch across all lakes is overwhelmingly dominated by a few key families: Tilapias (Family Cichlidae), Mullets (Family Mugilidae), and African Catfish C. gariepinus (Family Clariidae). The combined catch percentage of these three groups is notably high, constituting 95.22% in Manzala, 81.88% in Burullus, 97.08% in Edku, and 98.81% in Mariout.

Table 1.

Annual catch composition (Catch in tons and % of total catch) for the Nile Delta Lakes of Egypt (2022), illustrating the dominance of Cichlidae (Tilapias), Mugilidae (Mullets), and Clarias gariepinus in the total landings across the four systems.

While Tilapia was the largest single group in all four lakes (contributing over 47% of the total catch in Manzala and over 55% in Burullus), the secondary species vary by location. Lake Burullus, for instance, showed the highest diversity, recording significant percentages of shrimp (2.12%), grass shrimp (6.32%), and European Seabass D. labrax (1.58%). Conversely, Lake Mariout was dominated by African Catfish C. gariepinus (39.63%), almost matching the Tilapia catch (58.18%).

3.2. Length–Weight Relationships and Somatic Growth

The study successfully sampled four cichlid species from the four lakes: Oreochromis niloticus, O. aureus, Coptodon zillii, and Sarotherodon galilaeus. Among these, O. niloticus was the most frequently encountered cichlid. The African Catfish, Clarias gariepinus, was also highly prevalent, particularly in Lakes Manzala and Burullus. In addition to these dominant freshwater species, a number of marine species were collected, inhabiting areas around the sea inlets (boughazes) of the Nile Delta lakes, highlighting the ecological diversity of these brackish systems.

The morphometric parameters and resulting growth classifications for the investigated species are summarized in Table 2. This table details the morphometric parameters, including the length and weight ranges, the LWR parameters (a and b), and the resulting growth type for the investigated species across the Nile Delta lakes. The analysis of the exponent b revealed that the growth type varied considerably among the species and, in some cases, even between lakes, reflecting adaptation to local conditions. The exponent b is key: a value of b ≈ 3.0 indicates isometric growth (uniform growth in all dimensions); b > 3.0 indicates positive allometric growth (the species becomes heavier relative to its length); and b < 3.0 indicates negative allometric growth (the species becomes more slender as it grows). For example, in Lake Manzala, most fish species, such as O. niloticus and Liza ramada, exhibited isometric growth. Conversely, Clarias gariepinus and Solea aegyptiaca showed positive allometric growth, suggesting that these species are growing disproportionately heavier, while the crustacean Portunus pelagicus displayed negative allometric growth, potentially indicating favorable feeding conditions in that system. This parameter’s primary utility lies in allowing for the conversion of length to biomass for population dynamics modeling. Similarly, in Lake Burullus, several cichlids (O. aureus and Coptodon zillii) and the catfish (C. gariepinus) showed positive allometric growth, potentially indicating favorable feeding conditions in that system.

Table 2.

Length and weight ranges, Length–Weight Relationship (LWR) parameters (a and b), and estimated growth type for the studied fish and crustacean species in the Nile Delta Lakes. CL denotes Carapace Length.

3.3. Age Determination

The maximum observed age of the ten species was given in Table 3. From the relation between the total body length and the otolith radius of different studied fish species, the back-calculated lengths at the end of the different years of life were estimated and consequently the von Bertalanffy growth parameters were estimated.

Table 3.

Estimated population parameters, mortality rates, and exploitation levels for key fish and crustacean species from the Nile Delta Lakes, where K is the growth coefficient, L∞ is asymptotic length, t0 is theoretical age at zero length, F is fishing mortality, M is natural mortality, and E is the exploitation ratio.

3.4. Population Dynamics and Exploitation Status

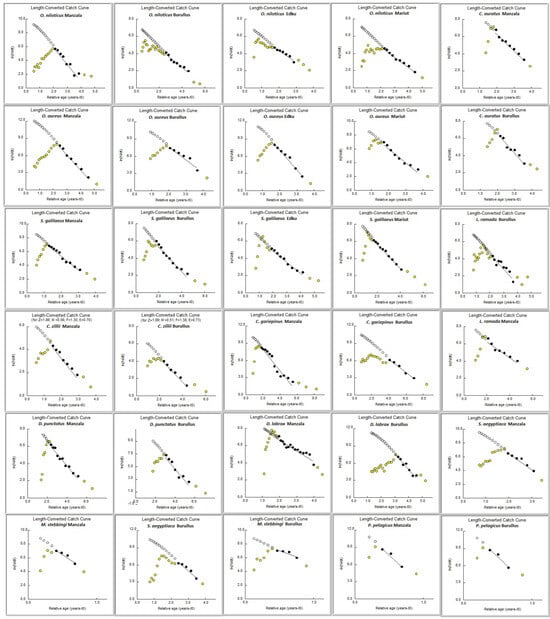

The growth parameters estimated via the VBGF varied among species and lakes, reflecting differences in life history strategies and environmental pressures. The estimated age, growth parameters (L∞, K, t0), and mortality rates (F, M, Z) derived from the analysis are summarized in Table 3. The asymptotic length (L∞), representing the theoretical maximum size, was highest for the commercially important Clarias gariepinus in both Manzala (86.78 cm) and Burullus (76.91 cm). Conversely, the growth coefficient (K), which indicates how quickly a species reaches its asymptotic length, was notably high for the crustaceans, Metapenaeus stebbingi and Portunus pelagicus, indicating rapid growth and short lifespans typical of invertebrate stocks. The total mortality rate (Z) for each species was presented by applying the Length-Converted Catch Curve (LCCC) method to the length frequency data, with the resulting linearized plots shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Length-Converted Catch Curve (LCCC) for the studied fish species in the Nile Delta lakes. The panels are organized by species, with the LCCC plot for each species identified by the scientific name and lake centered above the plot.

The exploitation ratio (E) was calculated to assess the fishing pressure on the stocks relative to the theoretical maximum sustainable yield (MSY), where a value of E > 0.5 indicates overexploitation [33]. The results clearly demonstrate a consistent and critical pattern of overexploitation across nearly all studied species in all four Nile Delta lakes. In Lake Manzala, for instance, all 12 species showed high exploitation ratios, ranging from E = 0.62 to E = 0.77, confirming an overexploited status for every stock examined. Similarly, in Lake Burullus, all 12 species were classified as overexploited with E values ranging from 0.61 to 0.80. The key cichlid species in both Lake Edku (E values between 0.60 and 0.67) and Lake Mariout (E values between 0.59 and 0.70) also consistently indicated an overexploited status. These findings, where exploitation ratios consistently lie well above the 0.5 threshold, clearly suggest that the current fishing mortality (F) significantly exceeds the natural mortality (M). This imbalance indicates that the current fishing effort is unsustainable and poses a serious threat to the long-term viability, biodiversity, and ecosystem services provided by the Nile Delta Lake fisheries.

A comparison (Table 4) of the LWR exponent b values confirms the high variability of fish condition across different locations and years, with previous studies showing ranges from 2.78 to 3.28 for O. niloticus and 2.97 to 3.09 for O. aureus, reflecting the different environmental and feeding regimes found in Lake Manzala, Lake Edku, and the Nile River itself. Crucially, the comparison of population parameters reveals a potential decreasing trend in the asymptotic length (L∞) for several Tilapia species over time, which may be indicative of either fishing pressure-induced size-selective mortality (i.e., ‘fishing down the size spectrum’) or adverse environmental changes impacting growth potential in these highly stressed ecosystems.

Table 4.

Summary of Length–Weight Relationship (LWR) parameters (a and b), alongside population dynamics parameters (Asymptotic length L∞, growth rate K, total mortality Z, natural mortality M, and length at first capture Lc) for the studied species as reported by different authors across several aquatic areas in Egypt.

The available regional data summarized in Table 4 highlights the historical scarcity of comprehensive stock assessments in the Nile Delta lakes. Specifically, while some population parameters have been previously estimated for Oreochromis species, the current parameters and stock status for the remaining species have largely been unevaluated across all four Delta lakes. Given the substantial ecological differences between the Delta lakes and other aquatic systems in Egypt (e.g., the Mediterranean, Bardawil Lagoon, Lake Qarun, and the Suez Canal), only data from the Nile Delta region were deemed appropriate for this comparative analysis.

4. Discussion

The analysis of catch statistics, population dynamics, and biological parameters across the Nile Delta lakes confirms the dual challenge facing these vital ecosystems: severe overexploitation of key commercial stocks and persistent ecological imbalance driven by anthropogenic pressures [8,46,47]. Collectively, the Nile Delta fisheries are economically vital, accounting for approximately 76% of the total catch from Egyptian lakes and contributing about 37% of the total catch from all natural resources, generating an estimated revenue of 17.6 billion EGP.

The commercial catch is overwhelmingly dominated by Tilapias (Cichlidae: mainly four species), Mullets (Mugilidae: mainly four species), and African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus), which collectively account for over 95% of landings in most lakes. While Tilapia historically represents a large percentage of landings, the continued dominance of this group, alongside the high contribution of C. gariepinus (especially in Lake Mariout, 39.63%), aligns with previous observations of a significant shift in fish species composition towards adaptable or opportunistic species [29,30]. These highly tolerant species, such as Catfish and Mullet, are known to thrive in polluted and hypoxic environments, indicating a potential biodiversity loss within the lakes and a correlation with increasing pollution levels [46,47]. Our results corroborate the ecological state described for specific lakes; for instance, the dominance of Tilapia and low landings in Lake Edku is consistent with reports of environmental stress and habitat degradation in that system [48]. Similarly, the relatively higher diversity and production in Lake Burullus, particularly the noted presence of Mullets and European Seabass, reflects its status as the current most productive lake, likely aided by recent rehabilitation efforts [49,50].

It is important to note that the official recording system in Egypt is often considered inaccurate and may not reflect the true landings from marine and inland fisheries. A significant limitation is that many commercially important species are not recorded individually but are grouped under a family name or the “Others” category. Consequently, urgent improvements are necessary for the current recording system, alongside capacity-building programs to enhance the qualifications of recorders at various landing sites. The assessment of the Length–Weight Relationship (LWR) revealed variations in somatic growth patterns, with the exponent b ranging from isometric (b ≈ 3.0) to positive or negative allometric. The occurrence of positive allometric growth (b > 3.0) in some stocks, such as C. gariepinus and certain cichlids in Lake Burullus, suggests potentially favorable feeding or environmental conditions for those specific populations [46,47]. Conversely, the presence of negative allometric growth (b < 3.0) in species like the shrimp Metapenaeus stebbingi indicates that these individuals are becoming more slender relative to their length, which can be an indicator of environmental stress or insufficient resource availability for optimal weight gain. Such variation in growth patterns across species and lakes underscores the need for lake-specific management approaches, considering the underlying mechanisms like nutrient loading and local water quality [48].

Reliable age observations are fundamental to nearly all aspects of fisheries investigations, particularly for studies concerning longevity, growth, production, and population dynamics. To ensure the accuracy of age estimates in this study, both otoliths and scales were examined to validate the aging process. Age was determined by counting the alternating opaque and translucent zones, which were considered yearly annuli. The readings obtained from the whole otoliths demonstrated good agreement with those estimated from scales (agreement ranged between 88% and 93% for the studied fish species). Furthermore, the consistency of the readings was statistically verified: the Coefficient of Variation (CV) ranged from 3.9% to 4.77%, and the Average Percentage Error (APE) ranged from 4.12% to 5.08%. Since these values are well within the acceptable limits suggested by Campana (2001) (APE ≤ 5.5% and CV ≤ 7.6%), the otolith readings were considered robust and were subsequently used for all further growth and population dynamics analysis [51].

The analysis of population dynamics provides the most critical finding for management: the calculated exploitation ratio (E) consistently exceeds the critical threshold of 0.5 [33] for virtually all 30 studied stocks across the four lakes. This high E (often exceeding 0.70) confirms a state of severe overexploitation, where fishing mortality (F) far outweighs natural mortality (M). This unsustainable fishing pressure is directly responsible for threatening the long-term viability and productivity of these resources.

Compounding this biological challenge are issues related to data reliability and fishing practices. Previous studies have highlighted the issue of data underestimation in official GAFRD statistics, particularly due to the rise of informal and amateur fishing activities [52]. The significant shift toward unregulated fishing, driven by socio-economic pressures like high unemployment, necessitates a re-evaluation of current regulatory frameworks [53]. This situation undermines the accuracy of fishing effort data (e.g., licensed boat numbers) and ultimately hinders the effective implementation of stock-based management strategies. Rehabilitation projects, while successful in increasing overall productivity in lakes like Burullus and Manzala [15,49], should be accompanied by robust enforcement and data systems to ensure that increased productivity is not immediately lost to unregulated, unsustainable fishing efforts. The findings underscore the urgency of integrating socio-economic factors and community-based co-management to achieve sustainable resource utilization.

Based on the evidence of severe overexploitation and ecological imbalance, essential management strategies are proposed to achieve long-term sustainability. It is paramount to establish and implement management policies that ensure the rational exploitation of these stocks. Continuous monitoring is required, especially when considering potential environmental fluctuations, changes in fishing effort, and the inherent multi-species nature of the ecosystem. Therefore, management should prioritize regular stock assessments, improved data collection methods, and adaptive management strategies that can quickly respond to both biological and environmental changes. Specific regulatory measures should include the regulation of mesh sizes and the control and prohibition of destructive gear types currently used in the lakes. Furthermore, efforts should also be made to optimize the water quality of these lakes. This includes regularly examining the water inflow from agricultural drainage canals and other drains to effectively control polluted water inflow into these important ecosystems. The continuous clearance and improvement of the Boughazes (sea inlets) are also crucial for enhancing water exchange and maintaining the natural brackish habitat necessary for the successful recruitment and life cycle of estuarine and marine species.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of population dynamics for the key commercial stocks across the Nile Delta lakes unequivocally demonstrated a state of severe overexploitation. The calculated exploitation rate (E) was consistently found to exceed the critical sustainability threshold of 0.5 for all 30 studied stocks, indicating that current fishing mortality far outweighs natural mortality. This unsustainable pressure was compounded by evidence of significant species composition shifts towards highly tolerant species and limitations in official fisheries data recording systems. Overall, the study provided the necessary updated biological parameters to confirm that the long-term viability and productivity of the Nile Delta fisheries are seriously threatened by the synergistic effects of overfishing and pervasive environmental degradation. A comprehensive, multi-faceted approach addressing both regulatory enforcement and environmental quality is therefore urgently required to secure the future of these economically vital ecosystems.

Author Contributions

S.F.M.: Conceptualization, Data analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. M.S.-K.: Conceptualization, Data analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific fund from public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No Live Specimens Used: Our research involved only dead fish samples. These specimens were collected from the existing catch of commercial fishermen or through standard scientific sampling methods, and no live animals were handled or subjected to experimental procedures. Local Legislation/IRB: There is currently no dedicated national Ethics Committee or IRB in Egypt mandated to review this type of purely observational fisheries research that utilizes already-caught, dead specimens. Adherence to 3Rs: The sample size used was the minimum necessary to achieve statistically robust results, adhering to the ethical principle of Reduction.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the local fishermen of the four Delta lakes for their generous help during the sampling procedure. Sincere thanks also go to our colleagues and the laboratory technician at the Fish Population Dynamics Lab, National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries (NIOF), for their valuable assistance in sample preparation and practical work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN 2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0461en (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Gallucci, V.F.; Saila, S.B.; Gustafson, D.J.; Rothschild, B.J. Stock Assessment: Quantitative Methods and Applications for Small Scale Fisheries; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; Marques, L.M.; Teixeira, C.R.; Giarrizzo, T.; Barreto, R.; Rodrigues-Filho, J.L. Digital media reveal negative impacts of ghost nets on Brazilian marine biodiversity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 172, 112821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, J.L.; Vigliola, L.; Kulbicki, M.; Labrosse, P.; Fortin, M.J.; Meekan, M.G. Human activities as a driver of spatial variation in the trophic structure of fish communities on Pacific coral reefs. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciutteri, V.; Pedà, C.; Longo, F.; Calogero, R.; Cangemi, G.; Pagano, L.; Battaglia, P.; Nannini, M.; Romeo, T.; Consoli, P. Integrated approach for marine litter pollution assessment in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea: Information from bottom-trawl fishing and plastic ingestion in deep-sea fish. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, B.; Barbier, E.B.; Beaumont, N.; Duffy, J.E.; Folke, C.; Halpern, B.S.; Jackson, J.B.; Lotze, H.K.; Micheli, F.; Palumbi, S.R.; et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science 2006, 314, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhady, A.A.; Khalil, M.M.; Ismail, E.; Mohamed, R.S.; Ali, A.; Snousy, M.G.; Fan, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, J. Potential biodiversity threats associated with metal pollution in the Nile–Delta ecosystem (Manzala lagoon, Egypt). Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.R.M.C.; Bergami, E.; Gomes, V.; Corsi, I. Occurrence and distribution of legacy and emerging pollutants including plastic debris in Antarctica: Sources, distribution, and impact on marine biodiversity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, J.; Hawkins, S.J. Habitat recovery and restoration in aquatic ecosystems: Current progress and future challenges. Aquat. Conserv. 2016, 26, 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, S.F. Egyptian Marine Fisheries and its sustainability. In Sustainable Fish Production and Processing; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAFRD. Year Book of Fishery Statistics; The General Authority of Fish Resources Development: Cairo, Egypt, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alzeny, A.; Abdel-Aziz, N.E.; El-Ghobashy, A.E.; El-Tohamy, W.S. Diet Composition and Feeding Habits of Fish Larvae of Five Species in the Burullus Lake, Egypt. Thalass. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2024, 40, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kafrawy, S.B.; Bek, M.A.; Negm, A.M. An Overview of the Egyptian Northern Coastal Lakes. In Egyptian Coastal Lakes and Wetlands: Part I—Characteristics and Hydrodynamics; Negm, A.M., Bek, M.A., El Kafrawy, S.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, S.F.; Hassan, N.H.; Koleib, Z.M.; El-Bokhty, E.B. Fish production, fishing gears, economic and social impacts of the purification and development project on Lake Manzalah fisheries, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2023, 27, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEAA. Environmental Information and Monitoring Programme; Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency: Cairo, Egypt, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bokhty, E.B. Biological and Economical Studies on Some Fishing Methods Used in Lake Manzala. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Science—Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Le Cren, E.D. The length-weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in the perch (Perca fluviatilis). J. Anim. Ecol. 1951, 20, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. A quantitative theory of organic growth. Hum. Biol. 1938, 10, 181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Beamish, R.J.; Fournier, D.A. A Method for Comparing the Precision of a Set of Age Determinations. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1981, 38, 982–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E. An account of the herring investigations conducted at Plymouth during the years from 1924 to 1933. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1933, 19, 305–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, L.A. A new graphic method of describing the growth of animals. Biol. Bull. 1946, 90, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, D.G. Estimation of mortality and growth parameters from the length-frequency in the catch. Rapp. P-V. Réun CIEM 1979, 175, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherall, J.A. A new method for estimating growth and mortality parameters from length-frequency data. Fishbyte 1986, 4, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D. Some Simple Methods for Assessment of Tropical Fish Stocks; FAO Fisheries Technical Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1983; pp. 234–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig, J.M. Estimating mortality rate from the maximum observed age. ICES CM 1982, 1982, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig, J.M. Empirical use of longevity data to estimate mortality rates. Fish. Bull. 1984, 82, 898–903. [Google Scholar]

- Ursin, E. A mathematical model of some aspects of fish growth, respiration and mortality. J. Fish. Res. Bd Can. 1967, 24, 2355–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikhter, V.A.; Efanov, V.N. On one of the approaches to the estimation of natural mortality of fish populations. ICNAF Res. Doc. 1976, 76/VI/8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D. On the interrelations between natural mortality, growth parameters and mean environmental temperature in fish stocks. J. Cons. Perm. Int. Explor. Mer. 1980, 39, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K. Fisheries for small pelagic species: An empirical approach to management targets. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 1992, 2, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, L.; Lebo, P.E.; King, R.P. The dynamics of an exploited population of a Siluroid catfish in the Cross River, Nigeria. Fish. Res. 1999, 40, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulland, J.A. The Fish Resources of the Ocean; FAO/Fishing News Books: Rome, Italy, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bokhty, E.A.; Fetouh, M.A. Some biological aspects of Oreochromis niloticus and Oreochromis aureus caught by trammel nets from El-Salam Canal, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2023, 27, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, S.F.; Desouky, M.G.; Makky, A.F. Growth, mortality, recruitment and fishery regulation of the Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus from Manzala Lake, Egypt. Iran. J. Ichthyol. 2020, 7, 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.A.; El-Kasheif, M.A. Age, growth and mortality of the cichlid fish Oreochromis niloticus (L.) from the river Nile at Beni Suef Governorate, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2013, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authman, M.M.N.; El-Kasheif, M.A.; Shalloof, K.A.S. Evaluation and management of the fisheries of Tilapia species in Damietta Branch of the River Nile, Egypt. World J. Fish. Mar. Sci. 2009, 1, 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, H.H.; Mazrouh, M.M. Biology and fisheries management of Tilapia species in Rosetta branch of the Nile River, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2008, 30, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bokhty, E.A. Assessment of family Cichlidae inhabiting Lake Manzala, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2006, 10, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhoum, S.A. Comparative reproductive biology of the Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (L.), Blue Tilapia, Oreochromis aureus (Steind.) and their hybrids in Lake Edku, Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish 2002, 6, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alla, A.; Talaat, K.M. Growth and dynamics of tilapias in Edku Lake, Egypt. Bull. Inst. Oceanogr. Fish. ARE 2000, 26, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, H.H.; Ezzat, A.A.; Ali, T.E.S.; El Samman, A. Fisheries management of cichlid fishes in Nozha Hydrodrome, Alexandria, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2013, 39, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.A. Age, Growth and Population Dynamics of Tilapia Species in the Egyptian Inland Waters, Lake Edku. Ph.D. Thesis, Sohag Faculty of Science, Assiut University, Sohag, Egypt, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hosny, C.F. Studies on Fish Populations in Lake Manzalah. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Science Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna, S.F.; Makkey, A.F.; Desouky, M.G. Growth, mortality and relative yield per recruit of sharptooth catfish Clarias gariepinus (Clariidae) in Lake Manzala, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish 2018, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy-Kamal, M.; Abdelhady, A.A. Long-term changes in fish landings and community structure in Nile Delta Lakes. Fishes 2025, 10, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhady, A.A.; Samy-Kamal, M.; Abdel-Raheem, K.H.; Ahmed, M.S.; Khalil, M.M. Changes in fish landings and biodiversity loss in Nile-Delta lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moneer, A.; Agib, N.S.; Khedawy, M. An overview of Lake Edku environment: Status, challenges, and next steps. Blue Econ. 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, S.F.; Faragallah, A.M.; Fattouh, S.A.; Haggag, S.M.; Clip, Z.M. A Comparative Economic Study Before and During the Current Purification and Development Operations in Lake Burullus. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2023, 27, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragallah, A.M.; Fattouh, S.A.; EL-Karashily, A.F.; Haggag, S.M. Impact of rehabilitation projects on fishing in Burullus Wetland. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2024, 28, 427. [Google Scholar]

- Campana, S.E. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish Biol. 2001, 59, 197–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy-Kamal, M.; Mehanna, S.F. Evolution of fishing effort and capacity in Egypt’s marine fisheries. Reg. Environ. Change 2023, 23, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalloof, K.; El-Ganiny, A.; El-Far, A.; Fetouh, M.; Aly, W.; Amin, A. Catch composition and species diversity during dredging operations of Mediterranean coastal lagoon, Lake Manzala, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2023, 49, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).