Abstract

The European squid Loligo vulgaris inhabits the continental shelf of the North and Central Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea, with significant socio-economic value for the associated fisheries. Globally, the stock appears to be maintained at levels close to the optimal sustainable yield, but capture statistics indicate high fluctuations in fisheries production, and some regions might be affected by overexploitation. In this study, we used the mitochondrial marker mtCOI to investigate temporal and spatial genetic structure and variability in the European squid in the eastern part of the Adriatic Sea and put it into context with its Mediterranean and Atlantic conspecifics using data from public databases. High haplotype and low nuclear diversity of mtCOI were detected, with no significant genetic differentiation, suggesting one panmictic homogeneous population in the North and Central Adriatic Sea. The Adriatic cluster appears to diverge from its Mediterranean–Atlantic conspecifics; however, this pattern should be considered preliminary due to the limited and uneven geographic sampling available in public databases. The current dataset lacks comprehensive coverage of several Mediterranean sub-basins, which restricts the resolution of connectivity patterns and may mask subtle population structure. Despite these limitations, our results provide an important baseline for understanding the L. vulgaris Adriatic stock and for developing joint management policies among all countries that exploit this shared resource.

Keywords:

cephalopods; European squid; Loligo vulgaris; COI; population structure; genetic diversity; Adriatic Sea; Mediterranean Sea Key Contribution:

This study provides the first multi-year population genetic analysis of 121 Loligo vulgaris individuals from the north and central coasts of the Eastern Adriatic Sea, showing high haplotype and low nucleotide diversity. The absence of spatial and temporal genetic structure indicates a single, panmictic population. Significant genetic divergence between the Adriatic and other Mediterranean populations suggests regional structuring, emphasizing the need for broader genomic analysis to clarify connectivity and local adaptation across the Mediterranean.

1. Introduction

Loligo vulgaris Lamarck 1798 (family Loliginidae), commonly known as the European squid, represents an ecologically and economically significant cephalopod species in Mediterranean and North Atlantic waters. As an important component of marine trophic webs and a valuable resource in commercial fisheries, understanding its distribution, population dynamics, and connectivity is essential for effective stock management and conservation [1]. Beyond its fishery importance, L. vulgaris has emerging biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, owing to the bioactive properties of its collagen-rich skin and ink, which exhibit antimicrobial, antioxidative, and anti-inflammatory characteristics [1].

The European squid exhibits a broad geographic distribution from the North Sea and the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean, across the entire Mediterranean Sea, particularly the Adriatic, Ionian, Aegean, and the Levantine Basin, to the north African coast [2,3]. It occupies coastal and semi-pelagic habitats, primarily between depths of 20 and 250 m [4], and performs both vertical and horizontal migrations driven by environmental factors, food availability, and its reproductive cycle. In the northeastern Atlantic, L. vulgaris populations overwinter in the deeper waters and migrate to shallower areas (20–80 m) of the North Sea to spawn between May and June, subsequently moving southward during autumn. In contrast, Mediterranean populations exhibit more continuous spawning activity, with regional differences in peak spawning periods, typically between early summer and autumn [3]. In the central Adriatic Sea, mature individuals are present year-round, with spawning peaks occurring between January and May [4].

Given their short lifespan, rapid growth, and sensitivity to environmental fluctuations, squid respond rapidly to oceanographic and climatic changes, making them valuable indicators of ecosystem variability [5]. Although L. vulgaris stocks are globally maintained near optimal sustainable levels, regional declines and signs of overexploitation have been documented [1].

In Croatian waters, L. vulgaris is a highly valued cephalopod species, exploited through small-scale commercial and recreational fisheries, as well as in whole-year-long multispecies trawl operations [6]. Reported catches in 2023 amounted to 145 tonnes [7], with interannual fluctuations observed in the past decade. While the Mediterranean basin has shown a general decline in European squid landings from 2019 to 2022 (2381 to 1381 tonnes live weight), the opposite trend has been recorded in the Northeast Atlantic (1490 to 3120 tonnes) [8]. These contrasting trends highlight the necessity of regionally adaptive and ecologically informed management practices.

Genetic analyses provide fundamental insights into population structure, diversity, and connectivity, enabling the delineation of management units and the assessment of resilience to environmental and anthropogenic pressures [9]. Among mitochondrial markers, cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) is widely used in population genetic and phylogeographic studies of marine organisms, including cephalopods [9,10,11,12,13,14,15], and constitutes a core marker in the global DNA barcoding system for animal identification [16,17].

Most previous population genetic studies of L. vulgaris have been conducted in the northeastern Atlantic, while information from the Mediterranean remains scarce. Olmos-Pérez et al. [10] applied DNA barcoding and morphometric analysis to loliginid paralarvae from the NE Atlantic, revealing high mitochondrial diversity but minimal population differentiation. Along the Galician coast (NW Spain), García-Mayoral et al. [13] analyzed paralarval samples and found high haplotype diversity but no significant spatial differentiation between northern and southern areas, indicating extensive gene flow at regional scales. Recently, García-Mayoral et al. [14], using a combined mitochondrial and genome-wide SNP approach, reported high genetic diversity and overall homogeneity along the western Iberian Peninsula, though adaptive SNPs revealed a subtle latitudinal gradient of differentiation potentially associated with environmental variation. In the Mediterranean, Pertesi et al. [18] examined mtCOI sequences and detected several geographically restricted haplotypes and significant differentiation between eastern and western basins, suggesting limited connectivity and possible historical isolation of the eastern Mediterranean population. The only investigation of L. vulgaris genetic structure in the Adriatic Sea, conducted by Garoia et al. [19], employed nuclear microsatellites along the Italian coast (western Adriatic) and included a single sample from the southeastern Adriatic near Albania. Although some evidence of local differentiation was detected depending on the marker and descriptor used, the authors concluded that L. vulgaris in the Adriatic Sea represented a genetically homogeneous stock.

Despite the ecological and economic significance of L. vulgaris in the Adriatic Sea, there remains a paucity of data regarding its fine-scale genetic structure and temporal variability within this semi-enclosed basin, as well as its connectivity with Mediterranean and Atlantic conspecifics. Addressing this knowledge gap is critical for understanding the evolutionary and ecological processes shaping L. vulgaris populations and for defining biologically meaningful management units in shared marine resources.

In the present study, we used the mitochondrial COI marker to investigate the spatial and temporal genetic structure and variability in L. vulgaris populations in the eastern Adriatic Sea and to contextualize these findings within the broader Mediterranean and Northeast Atlantic distribution of the species using publicly available sequence data. We hypothesized that L. vulgaris populations within the Adriatic exhibit unconstrained gene flow due to their dispersal potential; however, the gene flow between the Adriatic and other Mediterranean populations might be constrained by regional oceanographic and ecological barriers. Testing this hypothesis will provide insights of broad relevance to the study of population connectivity, local adaptation, and the impact of environmental variability on the genetic structure of widely distributed cephalopods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

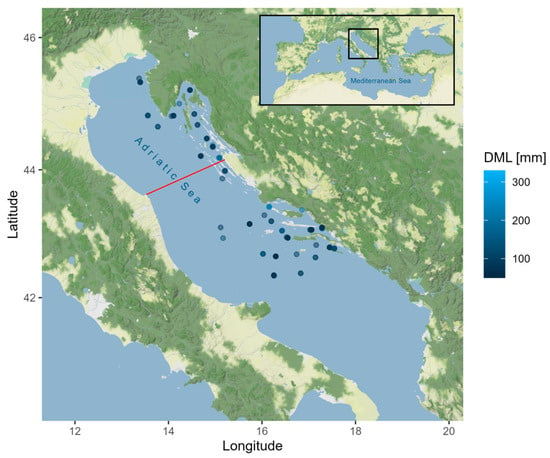

A total of 121 European squid Loligo vulgaris were analyzed in this study, comprising 28 females, 29 males, and 64 unsexed individuals. These specimens were collected during three bottom-trawl MEDITS surveys conducted in July 2019 (n = 47), 2020 (n = 37), and 2021 (n = 37) from the continental shelf and slope of the eastern Northern and Central Adriatic Sea (GSA 17) (Figure 1). The squids were caught at depths ranging from 28 to 170 m using a bottom trawl net (GOC 73) with a 20 mm mesh size codend that was towed for 30 min at a speed of 2.8–3.0 knots [20]. The dorsal mantle length (DML) of the sampled individuals ranged from 50 to 330 mm (mean 108.70 ± 48.66 SD) and the body weight (BW) from 6 to 595 g (mean 64.91 ± 84.24 SD). On board, a small piece of fresh mantle tissue from each individual was preserved in 96% ethanol and stored at +4 °C for further molecular analysis.

Figure 1.

Map of Loligo vulgaris sampling stations within MEDITS surveys in June 2019, 2020, and 2021 in the Eastern Adriatic Sea (DML—dorsal mantle length). The red line represents the Ancona–Zadar line dividing the North and Central Adriatic sub-basins. The maps were produced using the ggmap package v4.0.0 [21] for R and tiles by © Stadia Maps (https://stadiamaps.com/), © Stamen Design (https://stamen.com/), © OpenMapTiles (https://openmaptiles.org/), and © OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=5/39.723/19.314 (accessed on 28 January 2025)) contributors. This figure is not covered by the CC BY license and is subject to copyright.

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

The genomic DNA extraction followed a modified protocol from Martínez et al. [22]. Briefly, cell lysis buffer (0.2% SDS, 0.01 M TrisBase, 0.01 M EDTA, 0.15 M NaCl) containing 0.2 mg/mL proteinase K was used to dissolve tissue overnight at 55 °C. After a 10 min centrifugation at 13,000 rpm to precipitate the debris, proteins were salted out from the supernatant in 2.2 M NaCl, kept on ice for 10 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. After cold isopropanol precipitation, the DNA was washed in 75% ethanol, dried at 37 °C, and resuspended in TE buffer (0.01 M Tris-HCL, 0.0125 M EDTA, pH = 8).

A region of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI; 710 bp) was amplified using primer pair LCO1490: 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and HCO2198: 5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′ [23]. Each PCR reaction was performed in a final volume of 25 µL containing 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP, 0.4 µM of each primer, 1 U of GoTaq® G2 Hot Start Polymerase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), 50 ng of DNA template, and DNAse/RNAse-free water. The PCR conditions were as follows: denaturing for 2 min at 95 °C; 5 cycles of denaturing at 1 min at 95 °C; annealing at 1 min at 45 °C and extension during 1 min at 72 °C plus 30 cycles of 1 min at 95 °C, 1 min at 50 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, with the final extension for 5 min at 72 °C. Negative controls (water instead of DNA template) were run along each batch of samples to control for contaminant amplification, and they all failed to produce positive reactions. All PCR products were inspected using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and sent to the Macrogen Europe sequencing laboratory (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Amplicons were sequenced using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) in the forward direction using the LCO1490 primer.

2.3. Population Genetic Analyses

The mtCOI gene sequences were imported into MEGA 11 [24] and aligned using the Muscle algorithm. Low-quality sequence tails were trimmed off, and the sequences were re-aligned. The mtCOI gene electropherograms were all inspected carefully to ensure accuracy, and the sequences were manually corrected where electropherogram peaks did not support automatic base calls. BLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 8 July 2024)) was used to compare all sequences against the NCBI Nucleotide collection (nr/nt), and all were identified as L. vulgaris (average identity 99.2%). The generated sequences were deposited into GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank (accessed on 28 January 2025)) under Accession numbers PV023191-PV023311. To analyze potential differences among the three consecutive collection years (2019, 2020, and 2021) and the sampled areas (North Adriatic vs. Central Adriatic, taking the Ancona–Zadar line as a point of reference), all temporal and spatial groups were mutually compared in a crossed design using AMOVA. As both temporal and spatial comparisons displayed similar genetic characteristics and no differentiation, the data were subsequently aggregated either by year of sampling or location to facilitate observations of broader temporal and spatial trends in the Adriatic dataset.

Additionally, to examine genetic differentiation across various regions of the species’ distribution range, mtCOI gene sequences for Loligo vulgaris were downloaded from the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (accessed on 16 September 2024)) and the Barcode of Life Data System (https://v4.boldsystems.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2024)) (Accession numbers given in Table S1). Based on geographic origin, all sequences were compiled into a global dataset and categorized as follows: Adriatic (n = 121), Mediterranean (FAO 37, n = 13), Turkey (n = 24), Cyprus (Levantine Basin, n = 3), Northeast Atlantic (n = 35), Central Eastern Atlantic (n = 7), and Central Western Atlantic (n = 6). We kept these groups separate to ensure analytical accuracy and avoid misleading conclusions. The 13 Mediterranean sequences originated from commercial seafood products, labeled only FAO 37—Mediterranean and Black Sea fishing area, without precise locality information; thus, pooling them with spatially defined samples could artificially inflate or obscure regional genetic patterns. The samples from Turkey and Cyprus represent geographically distinct sampling areas, and a previous study by García-Mayoral et al. [14] showed that Turkish haplotypes form an atypical and potentially divergent cluster.

Genetic variability was analyzed using the DnaSP program v6.12.03 [25] by calculating the number of haplotypes (H), haplotype diversity (Hd), polymorphic sites (S), nucleotide diversity (π) [26], and average number of nucleotide differences (k) [27]. To visualize haplotype relationships, a median-joining haplotype network was constructed using PopART v1.7 software [28]. Changes in demographic history and deviations from neutral evolution were analyzed using Tajima’s D [27] and Fu’s Fs [29] statistics. The mismatch distribution under the demographic expansion model, Raggedness (r) index [30], and expansion factor tau (τ) with a 95% confidence interval were also calculated using ARLEQUIN v3.5.2.2 [31]. To reveal possible nested genetic population structures and verify the haplotype network configuration, we used the fastbaps algorithm implemented in the R package fastbaps (v1.0.8). It is a computationally efficient implementation of hierarchical Bayesian analysis of population structure [32,33]. We applied the fastbaps pipeline using the default Dirichlet prior with the optimise.baps option and performed hierarchical clustering at two levels to explore possible substructures within major clusters. The sensitivity and stability of the clusters were inspected with 1000 bootstrap replicates, and the resulting co-occurrence count matrix was visualized as a heatmap.

Pairwise genetic divergence between populations was estimated using the fixation index ΦST in ARLEQUIN v3.5.2.2 2 [31], employing the Tamura and Nei distance matrix without gamma correction. The significance of the pairwise ΦST values was assessed with the Exact test of population differentiation (No. of steps in Markov chain = 100,000), and Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the statistical significance of the indices among populations.

A phylogenetic tree of all haplotypes was reconstructed in Geneious Prime v2023.4 software using the Bayesian inference method, with the HKY+F+I evolutionary model. The best-fit evolutionary model was selected based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) calculated using the IQ-TREE web server with auto model selection [34,35,36,37]. Loligo forbesii (OK135754) was selected as the outgroup sibling species. The phylogenetic tree was visualized and processed graphically using FigTree v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree (accessed on 10 February 2025); Edinburgh, UK).

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity and Haplotype Network

The alignment of the 121 analyzed mtCOI sequences from Adriatic Loligo vulgaris was 548 bp long. A total of 30 haplotypes (H) and 20 variable polymorphic sites (S) were identified, including 8 singleton variable and 12 parsimony informative sites. The Adriatic dataset exhibited high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.824), indicating substantial genetic variation with many singleton sequences present in the population. Conversely, the low nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00249) suggested minimal nucleotide differences among individuals. The genetic diversity of Adriatic squids, by each sampling year and geographic region, is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genetic diversity estimates for mtCOI sequences of Loligo vulgaris from the Eastern Adriatic Sea.

The haplotype network analysis of the Adriatic samples regarding both spatial (North vs. Central) and temporal patterns (2019, 2020, and 2021) revealed a star-shaped pattern, characterized by three main haplotypes (H1, H2, and H3) shared by 68.60% of all Adriatic specimens, along with a high number of unique haplotypes separated by a single mutation (Table S2; Figures S1 and S2).

The global dataset alignment included 209 sequences (121 from the Adriatic, 13 from the Mediterranean, 3 from Cyprus, 24 from Turkey, 35 from the Northeast Atlantic, 7 from the Central Eastern Atlantic, and 6 from the Central Western Atlantic) with a length of 454 bp. It contained 40 variable polymorphic sites (S), including 16 singleton variable and 24 parsimony-informative sites. A total of 49 haplotypes (H) were identified, exhibiting high overall haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.836) and moderate nucleotide diversity (π = 0.01549). Haplotype diversity ranged from 0.524 (CE Atlantic) to 0.949 (Mediterranean), while nucleotide diversity varied from 0.00147 (Cyprus) to 0.01305 (NE Atlantic) (Table 2). The average number of nucleotide differences between haplotypes was lowest for Cyprus and the Adriatic (k < 1) and highest for the Mediterranean and NE Atlantic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic diversity estimates for mtCOI sequences of Loligo vulgaris populations from different geographic regions.

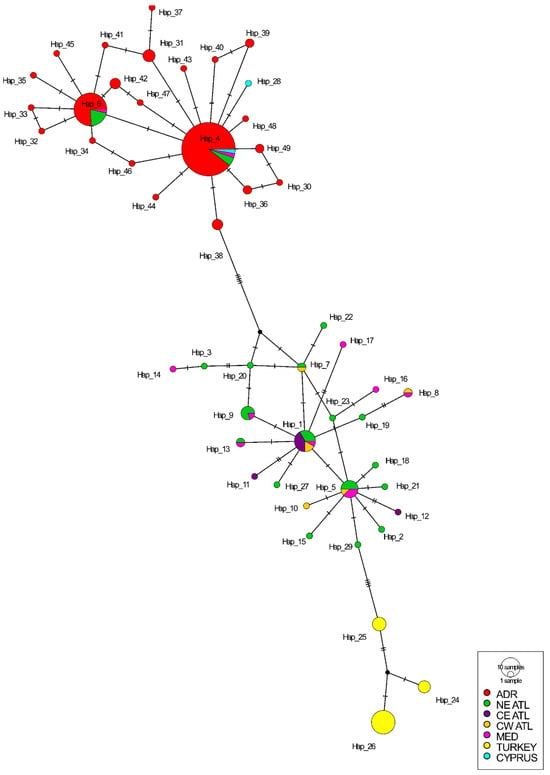

The median-joining haplotype network revealed three well-defined haplotype clusters across the seven geographical groups (Figure 2). The first cluster contained all major Adriatic haplotypes along with the few shared sequences from Cyprus, the Mediterranean, and the NE Atlantic, forming a cohesive Adriatic-centered group. Within this cluster, Adriatic individuals (n = 91) predominantly belonged to two high-frequency haplotypes (Hap 4 and Hap 6), which were also shared with a small number of Mediterranean samples (n = 3), two individuals from Cyprus, and ten individuals from the NE Atlantic. A second, clearly separated cluster comprised haplotypes shared among the Mediterranean, NE Atlantic, CE Atlantic, and CW Atlantic groups, but it notably excluded sequences from the Adriatic, Cyprus, and Turkey. These two main clusters were divided by five mutational steps, indicating a marked genetic discontinuity between Adriatic-associated haplotypes and the broader Mediterranean–Atlantic assemblage. The Turkish haplotypes formed a third distinct cluster branching from the Mediterranean–Atlantic group.

Figure 2.

Median-joining haplotype network of Loligo vulgaris mtCOI sequences from different geographic areas. The network displays the frequency of individual gene haplotypes. The size of each circle corresponds to the number of individuals belonging to a particular haplotype. Bars on branches indicate the number of mutations. Black dots indicate missing haplotypes (ADR—Adriatic, NE ATL—Northeast Atlantic, CE ATL—Central Eastern Atlantic, CW—Central Western Atlantic, MED—Mediterranean).

This topology was further confirmed with Bayesian hierarchical clustering analysis, which inferred three major primary clusters: one consisting of only Turkish sequences; a large cluster containing all Adriatic samples together with Cyprus sequences and a subset of Mediterranean and NE Atlantic sequences; and a third cluster formed by the remaining Mediterranean–Atlantic haplotypes. On a second level, no substructure was detected within the Adriatic cluster, but the other two showed some heterogeneity associated with individual haplotypes (Figure S3). These primary clusters were stable across 1000 bootstrap replicates, indicating strong support for the inferred structure (Figure S4).

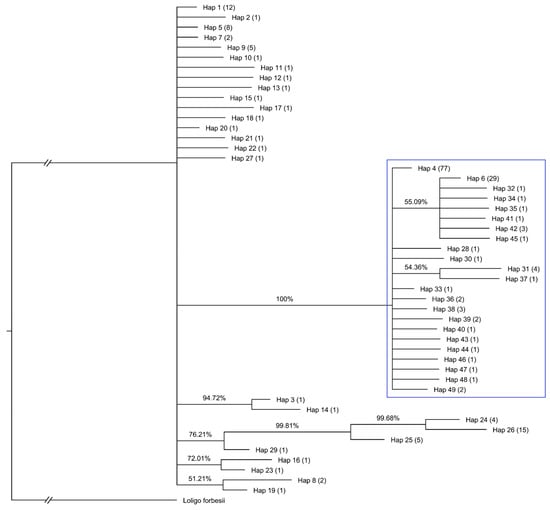

The Bayesian phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3) also showed that all Adriatic sequences cluster together in a distinct, well-supported group (posterior probability = 100%), indicating a coherent Adriatic cluster relative to other Mediterranean and Atlantic populations. The haplotypes corresponding to this topology are listed in Table S3, which provides the shared and unique haplotypes for each region based on the mtCOI global dataset.

Figure 3.

Bayesian inference (BI) tree based on mtCOI haplotypes of Loligo vulgaris from the global dataset, including sequences generated in this study and those retrieved from GenBank. The node values indicate BI posterior probabilities (%). The blue square highlights all Adriatic sequences sampled in this study. The numbers in parentheses following each haplotype (Hap) represent the number of individual sequences grouped under that haplotype. Haplotypes 4 and 6 are shared with sequences from the Mediterranean, Cyprus, and NE Atlantic: Hap 4 includes sequences from the Mediterranean (n = 2), Cyprus (n = 2), and NE Atlantic (n = 4), whereas Hap 6 includes sequences from the Mediterranean (n = 1) and NE Atlantic (n = 6). All 24 sequences from Turkey cluster within haplotypes 24, 25, and 26.

For the overall global dataset, neutrality statistics and mismatch-distribution parameters revealed pronounced regional differences in the demographic history of L. vulgaris across its range (Table 3). The Adriatic population showed significantly negative Tajima’s D (−1.7421, p = 0.014) and Fu’s Fs (−24.3391, p = 0.001), indicating the rejection of the null hypothesis of neutral evolution and possible population expansion. It is also the only group with a substantial sample size. The sum of squares of deviations (SSD) of the mismatch distribution was non-significant, but the raggedness index was, suggesting deviations from the expected model of sudden expansion (Table 3). No signs of recent demographic growth were detected in the Mediterranean group, which exhibited non-significant neutrality values and mismatch statistics. In the NE Atlantic, significantly negative Fu’s Fs indicated population growth, while the CE Atlantic showed conflicting signals, with negative Tajima’s D and poor SSD fit, likely due to the small sample size. The CW Atlantic group displayed significantly negative Fu’s Fs and mismatch parameters, consistent with recent moderate expansion. The Turkish samples showed no significant neutrality and a poor fit to an expansion model.

Table 3.

Neutrality test statistics and mismatch distribution analysis for the mtCOI sequences of Loligo vulgaris across different geographical regions.

3.2. Population Genetic Structure

In the Adriatic dataset, the results of the Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) indicated no significant genetic differentiation between the two analyzed regions, the North and Central Adriatic, with a ΦST value of 0.00983 (p = 0.446). Consequently, the data were pooled for temporal analysis, which revealed that 100% of the genetic variation occurred within populations. The overall ΦST index across sampling years was −0.00433 (p = 0.708).

For the global dataset, the AMOVA analysis revealed geographically structured genetic differentiation among L. vulgaris populations across the Adriatic, Mediterranean, and Atlantic regions (Table 4). The overall pairwise ΦST was 0.7662, indicating a high level of genetic differentiation, with 76.62% of the genetic variation occurring among populations. Within the analyzed populations, the Adriatic showed very high and significant differentiation from all Atlantic groups (ΦST = 0.68–0.90, p < 0.001) and from the Mediterranean group (ΦST = 0.77, p < 0.001) but little differentiation from Cyprus (ΦST = 0.033, p = 0.376). The Atlantic populations were generally weakly structured, with low ΦST values between the NE, CE, and CW Atlantic groups (ΦST ≤ 0.12). The Turkish samples showed consistently high and significant separation from all other regions (ΦST = 0.67–0.93, p < 0.001). Overall, the ΦST matrix indicates a distinct Adriatic cluster, high connectivity within the Atlantic, and a strongly divergent Turkish population.

Table 4.

Population pairwise ΦST values based on the mtCOI gene region for Loligo vulgaris populations from different geographic areas.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate high genetic variability in the European squid Loligo vulgaris along the northern and central parts of the eastern Adriatic coast, characterized by high haplotype and low nucleotide diversity, as evidenced by MEDITS sampling in 2019, 2020, and 2021. No temporal or spatial shifts in the genetic structure were found, suggesting a single panmictic population, consistent with the findings of Garoia et al. [19] for the western Adriatic. This pattern is in accordance with the species’ life history traits and the oceanographic characteristics of the Adriatic basin. Squids migrate inshore in winter for mating and reproduction [4], and after hatching, paralarvae exhibit a planktonic lifestyle for up to two to three months, resulting in high dispersal potential that can sustain high genetic flow between distant demes [3,38]. The general surface circulation of the Adriatic Sea further supports this connectivity, characterized by a large-scale counterclockwise cyclonic meander with a north-westward flow along the eastern coast, more pronounced in winter, and a return south-eastward flow along the western coast [39]. Additionally, L. vulgaris undertakes daily vertical migrations while foraging, moving toward the surface after sunset, a behavior already present in paralarvae and juveniles. This vertical movement enhances alongshore dispersal, while fluctuations in prey availability may trigger stronger offshore migrations, thereby broadening the species’ distribution [3,40].

A web-like haplotype network with multiple centers was observed for the investigated Adriatic L. vulgaris population. Most individuals shared two to three haplotypes, while others were singletons. This network structure, along with low nucleotide and large haplotype diversity, is consistent with the presence of many closely related sequences that may indicate population growth after a period of reduced effective population size or a historical bottleneck [41]. The demographic expansion of L. vulgaris in the Adriatic Sea is supported by significantly negative values of Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs, indicating an excess of rare haplotypes consistent with recent population growth [30,42]. The significant raggedness index, however, implies slight deviations from the smooth unimodal distribution expected under a simple expansion model, possibly due to local structure or incomplete mixing. Overall, these patterns indicate a relatively recent demographic expansion in the Adriatic population, although finer-scale and currently undetected population subdivision or migration could also influence these statistics. Neutrality tests and mismatch distribution analyses across all tested regions support this interpretation and reveal pronounced spatial heterogeneity in L. vulgaris demographic histories. The Mediterranean and NE Atlantic populations appear to reflect older or more gradual expansions, the CE Atlantic shows inconclusive patterns likely due to small sample sizes, and the CW Atlantic indicates a more recent expansion. This regional variability likely reflects differences in postglacial recolonization dynamics, hydrographic barriers, and historical population sizes [43]. However, these comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as the Adriatic dataset is substantially larger and thus provides greater statistical power than those from other regions.

Currently, it is not possible to properly assess the genetic connectivity of L. vulgaris across the Mediterranean because most sequences deposited in public databases were generated primarily for species identification and DNA barcoding rather than population genetic analyses [44,45]. As a result, these data often lack comprehensive geographic coverage and a consistent sampling design. For example, Maggioni et al. [45] collected L. vulgaris samples from seafood products and assigned their geographic origin based on a traceability label as FAO fishing zones, with the entire Mediterranean grouped under zone 37. Similarly, Keskin and Atar [44] deposited 24 L. vulgaris sequences from Yumurtalık in Turkey, gathered as bycatch from local trawlers or fish markets. However, they used only three in their analyses, representing just three haplotypes. When comparing our eastern Adriatic sample of L. vulgaris to other Mediterranean and Atlantic groups (limited sample size), we observed significant genetic differentiation, largely driven by the pronounced separation between the Adriatic population and the highly divergent Turkish population. This was also depicted in the haplotype networks, where none of the Adriatic haplotypes were shared with the Mediterranean–Atlantic group, while the Turkish samples formed a distinct haplotype cluster. García-Mayoral et al. [14] also reported the unusual differentiation of Turkish haplotypes and suggested that the existence of a sibling species/subspecies, editing errors in sequences, or the presence of nuclear copies of the mtCOI gene (numts) [17] may explain this pattern. The differentiation of three Cyprus haplotypes from geographically proximate Turkish ones further supports the irregular nature of these data. Although rare demographic events, such as genetic drift combined with selection sweep or accidental sampling of related individuals [46], could also contribute to this signal, these explanations appear unlikely given the life history traits and dispersal potential of L. vulgaris. Introduction of distant haplotypes through anthropogenic vectors also cannot be ruled out [47]. It is therefore important to acknowledge that the incorporation of publicly available sequences introduces potential sources of bias that can affect phylogeographic interpretation. Uneven sampling intensity, uncertain sequence origin, and sequence quality control among studies may produce artefactual haplotypes or omit rare variants, thereby distorting haplotype frequency spectra used in neutrality tests and mismatch analyses. Consequently, the Mediterranean–Atlantic dataset should be regarded as an approximation of regional trends rather than a definitive depiction of population structure. Nevertheless, the major patterns observed here, i.e., high Adriatic haplotype diversity, presence of unique Adriatic haplotypes, and limited haplotype sharing with the wider Mediterranean, are unlikely to arise solely from database artefacts because the Adriatic sample was generated under consistent conditions and analyzed together with all available comparative sequences.

The sequences from Cyprus (Levantine basin) also raise questions regarding the existence of a distinct Adriatic cluster with respect to the broader Mediterranean–Atlantic group. Although the Cyprus sample is too small to draw definitive conclusions, its partial overlap with the Adriatic haplotypes suggests some historical gene flow. This is further supported by the fact that Garoia et al. [19] did not find a genetic break of L. vulgaris between the North, Central, and South Adriatic, where the deep South Adriatic Pit with steep continental slopes might present a barrier to gene flow [48]. It remains to be seen whether the Otranto Strait, a narrow and deep passage connecting the Adriatic and Ionian Seas, plays a role in the creation of the Adriatic cluster and to what extent. Although the strait allows inflow of surface Ionian waters and outflow of deeper Adriatic waters, its hydrodynamic regime and frontal structures can intermittently limit the exchange of pelagic paralarvae and reproductive adults. The Otranto Strait may act as a semi-permeable biogeographic barrier, thus restricting but not completely preventing genetic exchange between Adriatic and Ionian populations.

In the case of a sibling congeneric species, the veneid squid Loligo forbesii, the Adriatic, Ionian, and Aegean Seas form a connected region characterized by Mediterranean clade-specific haplotypes that gradually transition into Eastern Atlantic lineages across the admixed Sardinian waters and the Gulf of Cadiz [12]. Although L. forbesii exhibits considerable gene flow across its entire geographic range, its population structure is influenced by geographic, hydrographic, and hydrodynamic barriers, such as deep-sea zones, the Strait of Gibraltar, and the Italian peninsula. In addition, the sub-structuring of L. forbesii has been observed around the offshore Azores, Rockall, and Faroe Banks [12,49,50]. A similar pattern is evident in another cephalopod, the European cuttlefish Sepia officinalis, which displays a distinctive eastern Mediterranean cluster and a transitional zone of high haplotype diversity in Sardinian waters [11,43]. The divergence of Aegean–Ionian haplotypes of S. officinalis has been attributed to radical hydrological changes during the Pleistocene glaciations that initially isolated this lineage and were later reinforced by a quasi-circular anticyclonic front southwest of the Peloponnese [43]. The more admixed separation observed between the eastern and western Mediterranean populations of L. forbesii may reflect similar historical processes, combined with the species’ high dispersal capability and repeated recolonialization of the Mediterranean from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar following the last glacial period [12]. Considering the similar life trait characteristics of L. forbesii and L. vulgaris, it is reasonable to assume that L. vulgaris populations were, and continue to be, shaped by the same historical and geo-oceanographic events. However, further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis. Much lower haplotype diversity of mtCOI has been noted for L. forbesii than L. vulgaris [12,14], which may affect the comparative resolution of this marker. Molluscs are generally characterized by a relatively high evolutionary rate for mtCOI, with cephalopods showing particularly high within-group variability [17].

Similar to the eastern Adriatic L. vulgaris, populations along the Galician coast of Spain in the northeastern Atlantic also exhibited high haplotype diversity and no evident phylogeographic segregation [10,13,14]. These Atlantic populations generally showed a higher level of nucleotide diversity and patterns consistent with neutral evolution. By using nuclear single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which provide genome-wide resolution and greater sensitivity to recent demographic processes, García-Mayoral et al. [14] detected a slight, though non-significant, gradient of genetic differentiation from north to south along the western Iberian Peninsula, especially when considering adaptive candidate SNPs. In contrast, Pertesi et al. [18] reported low haplotype diversity in L. vulgaris from eastern Mediterranean populations, indicating relative isolation probably due to ecological and historical factors, such as the Aegean region being a hotspot of endemism or past population fragmentation. However, it is important to note that Pertesi et al. analyzed a relatively short fragment of the mtCOI gene, only 213 bp in length, which may have influenced their findings. Other loliginid squids display variable phylogeographical patterns but consistently show high levels of gene flow across broad geographic scales. For example, the market squid Doryteuthis (Loligo) opalescens shows no large-scale population structure off the coast of California, with only fine-scale temporal micro-cohorts observed with a low level of genetic differentiation [51]; Loligo reynaudii and Doryteuthis pealeii show no differentiation between different spawning aggregations off the coast of South Africa [52]; the Patagonian squid Doryteuthis gahi displays distinct spatial structure and demographic contrasts between Chilean and Peruvian coasts [53]; and Sepioteuthis lessoniana populations show marked differentiation between the Japanese, East China, and South China Seas [54].

Our results indicate high connectivity and genetic homogeneity within the North and Central Eastern Adriatic L. vulgaris populations, suggesting panmixia across these regions. However, because our sampling did not include the Southern Adriatic, these conclusions should be regarded as geographically limited to the northern and central parts of the basin. The deep South Adriatic Pit and associated hydrographic fronts may influence gene flow and population structure, and further sampling from this region is required to confirm whether panmixia extends throughout the entire Adriatic Sea. Given that high haplotype diversity is characteristic of this species, a large and more geographically comprehensive sampling, particularly across the eastern and western Mediterranean, will be necessary to accurately represent the full population.

Furthermore, while mtCOI proved effective for identifying broad-scale patterns of diversity and historical demography [9,11,12,14,53], reliance on a single mitochondrial marker imposes certain limitations. As a maternally inherited locus, mtCOI may not capture recent gene flow, sex-biased dispersal, or fine-scale population structure. Consequently, subtle or cryptic differentiation among L. vulgaris populations could remain undetected. Future studies should integrate multiple genetic markers, including nuclear markers such as microsatellites or genome-wide SNPs, to better resolve fine-scale differentiation and delineate the boundaries of L. vulgaris genetic connectivity.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first comprehensive multi-year genetic assessment of the European squid Loligo vulgaris along the north and central eastern Adriatic coast, revealing an absence of spatial and temporal genetic structuring. The lack of detectable differentiation among Adriatic populations supports our hypothesis of unconstrained gene flow within this region, consistent with the species’ dispersal potential. In contrast, preliminary comparative analyses incorporating Mediterranean and Atlantic datasets indicate significant genetic divergence of Adriatic individuals, suggesting the influence of regional oceanographic barriers to gene flow or potential cryptic lineages. These findings highlight the importance of broader-scale sampling and multilocus approaches to further resolve population connectivity across the species’ distribution range.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10120612/s1: Figure S1: Median-joining haplotype network of Loligo vulgaris mtCOI sequences from the Eastern Adriatic Sea according to the sampled area; Figure S2: Median-joining haplotype network of Loligo vulgaris mtCOI sequences from the Eastern Adriatic Sea according to the sampled year; Figure S3: Graphical visualization of individual best assignment to genetic hierarchical clusters of mtCOI inferred by the fastbaps package for R; Figure S4: Heatmap vizualization of the co-occurence count matrix resulting after 1000 bootstrap replicates of the mtCOI Loligo vulgaris dataset; Table S1: List of GenBank and BOLD Accession Numbers of Loligo vulgaris COI sequences used in the present study; Table S2: Adriatic Loligo vulgaris accession numbers from the present study and their haplotypes, as presented in the phylogenetic tree in Figure 3; Table S3. Shared and unique haplotypes for each analyzed region. References [10,44,45,55,56,57,58,59,60] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and Ž.T.; methodology, M.P., D.Š., H.U., I.I. and Ž.T.; validation, M.P. and Ž.T.; formal analysis, M.P., D.Š. and Ž.T.; investigation, M.P., H.U., I.I. and Ž.T.; resources, H.U., I.I., B.A., A.S. and M.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., D.Š. and Ž.T.; writing—review and editing, M.P., D.Š., B.A., A.S., M.Š. and Ž.T.; visualization, M.P. and Ž.T.; supervision, M.P. and Ž.T.; project administration, M.P. and Ž.T.; funding acquisition, B.A., A.S. and M.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the MEDITS surveys that are co-funded by the European Union through the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) within the National Program for the collection, management, and use of data in the fisheries sector and support for scientific advice regarding the Common Fisheries Policy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Loligo vulgaris individuals were collected within the framework of the MEDITS Programme, applying a standardized sampling protocol. All specimens were dead at the moment of sampling the muscle tissue for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The molecular data presented in this study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the GenBank Accession numbers PV023191-PV023311.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and valuable suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lishchenko, F.; Perales-Raya, C.; Barrett, C.; Oesterwind, D.; Power, A.M.; Larivain, A.; Laptikhovsky, V.; Karatza, A.; Badouvas, N.; Lishchenko, A.; et al. A Review of Recent Studies on the Life History and Ecology of European Cephalopods with Emphasis on Species with the Greatest Commercial Fishery and Culture Potential. Fish. Res. 2021, 236, 105847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.; Rocha, F. The Life History of Loligo vulgaris and Loligo forbesi (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae) in Galician Waters (NW Spain). Fish. Res. 1994, 21, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Lefkaditou, E.; Robin, J.P.; Pereira, J.; González, A.F.; Seixas, S.; Villanueva, R.; Pierce, G.J.; Allcock, A.L.; Jereb, P. Loligo vulgaris. In Cephalopod Biology and Fisheries in Europe: II. Species Accounts; Jereb, P., Allcock, A.L., Lefkaditou, E., Piatkowski, U., Hastie, L., Pierce, G., Eds.; ICES Cooperative Research Report No. 325; International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; pp. 115–134. ISBN 978-87-7482-155-7. [Google Scholar]

- Krstulović Šifner, S.; Vrgoč, N. Population Structure, Maturation and Reproduction of the European Squid, Loligo vulgaris, in the Central Adriatic Sea. Fish. Res. 2004, 69, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, G.J.; Valavanis, V.D.; Guerra, A.; Jereb, P.; Orsi-Relini, L.; Bellido, J.M.; Katara, I.; Piatkowski, U.; Pereira, J.; Balguerias, E.; et al. A Review of Cephalopod—Environment Interactions in European Seas. In Essential Fish Habitat Mapping in the Mediterranean; Valavanis, V.D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 49–70. ISBN 978-1-4020-9140-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vrgoč, N.; Arnen, E.; Jukić-Peladić, S.; Krstulović Šifner, S.; Mannini, P.; Marčeta, B.; Osmani, K.; Piccinetti, C.; Ungaro, N. Review of Current Knowledge on Shared Demersal Stocks of the Adriatic Sea. FAO-MiPAF Scientific Cooperation to Support Nephrops Fisheries in European Waters. Responsible Fisheries in the Adriatic Sea. GCP/RER/010/ITA/TD. Adria Med. Tech. 2004, 12, 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Croatia—Statistical Data of Fisheries and Aquaculture for the Year 2023; Ministry of Agriculture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2024. Available online: https://podaci.ribarstvo.hr/statistika/statisticki-podaci-ribarstva-i-akvakulture-skupni-godisnji-izvjestaji/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, R.; Vacca, L.; Cuccu, D.; Mereu, M.; Cau, A.; Follesa, M.C.; Cannas, R. Genetic Population Structure and Phylogeny of the Common Octopus Octopus vulgaris Cuvier, 1797 in the Western Mediterranean Sea through Nuclear and Mitochondrial Markers. Hydrobiologia 2018, 807, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Pérez, L.; Pierce, G.J.; Roura, Á.; González, Á.F. Barcoding and Morphometry to Identify and Assess Genetic Population Differentiation and Size Variability in Loliginid Squid Paralarvae from NE Atlantic (Spain). Mar. Biol. 2018, 165, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drábková, M.; Jachníková, N.; Tyml, T.; Sehadová, H.; Ditrich, O.; Myšková, E.; Hypša, V.; Štefka, J. Population Co-Divergence in Common Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) and Its Dicyemid Parasite in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göpel, A.; Oesterwind, D.; Barrett, C.; Cannas, R.; Caparro, L.S.; Carbonara, P.; Donnaloia, M.; Follesa, M.C.; Larivain, A.; Laptikhovsky, V.; et al. Phylogeography of the Veined Squid, Loligo forbesii, in European Waters. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mayoral, E.; Roura, Á.; Ramilo, A.; González, Á.F. Spatial Distribution and Genetic Structure of Loliginid Paralarvae along the Galician Coast (NW Spain). Fish. Res. 2020, 222, 105406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mayoral, E.; Silva, C.N.S.; Ramilo, A.; Roura, Á.; Moreno, A.; Strugnell, J.M.; González, Á.F. Population Connectivity of the European Squid Loligo vulgaris along the West Iberian Peninsula Coast: Comparing mtDNA and SNPs. Mar. Biol. 2024, 171, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, L.N.; Bich, T.T.; Van Ket, N.; Van Long, N. Genetic Diversity, Variation, and Structure of Two Populations of Bigfin Reef Squid (Sepioteuthis lessoniana d’Orbigny) in Con Dao and Phu Quoc Islands, Vietnam. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; deWaard, J.R. Biological Identifications through DNA Barcodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strugnell, J.M.; Lindgren, A.R. A Barcode of Life Database for the Cephalopoda? Considerations and Concerns. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2007, 17, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertesi, V.; Sarantopoulou, J.; Exadactylos, A.; Vafidis, D.; Gkafas, G.A. Genetic Structuring and Connectivity of European Squid Populations in the Mediterranean Sea Based on Mitochondrial COI Data. Fishes 2025, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoia, F.; Guarniero, I.; Ramšak, A.; Ungaro, N.; Landi, M.; Piccinetti, C.; Mannini, P.; Tinti, F. Microsatellite DNA Variation Reveals High Gene Flow and Panmictic Populations in the Adriatic Shared Stocks of the European Squid and Cuttlefish (Cephalopoda). Heredity 2004, 93, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, J.A.; Gil De Sola, L.; Papaconstantinou, C.; Relini, G.; Souplet, A. The General Specifications of the MEDITS Surveys. Sci. Mar. 2002, 66, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, D.; Wickham, H. Ggmap: Spatial Visualization Withggplot2. R J. 2013, 5/1, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, G.; Shaw, E.M.; Carrillo, M.; Zanuy, S. Protein Salting-Out Method Applied to Genomic DNA Isolation from Fish Whole Blood. BioTechniques 1998, 24, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA Primers for Amplification of Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I from Diverse Metazoan Invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-231-88671-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F. Statistical Method for Testing the Neutral Mutation Hypothesis by DNA Polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. POPART: Full-feature Software for Haplotype Network Construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-X. Statistical Tests of Neutrality of Mutations Against Population Growth, Hitchhiking and Background Selection. Genetics 1997, 147, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.; Harpeding, H. Population Growth Makes Waves in the Distribution of Pairwise Genetic Differences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992, 9, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin Suite Ver 3.5: A New Series of Programs to Perform Population Genetics Analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Connor, T.R.; Siren, J.; Aanensen, D.M.; Corander, J. Hierarchical and Spatially Explicit Clustering of DNA Sequences with BAPS Software. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonkin-Hill, G.; Lees, J.A.; Bentley, S.D.; Frost, S.D.W.; Corander, J. Fast Hierarchical Bayesian Analysis of Population Structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5539–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.-T.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A Fast Online Phylogenetic Tool for Maximum Likelihood Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailleul, D.; Mackenzie, A.; Sacchi, O.; Poisson, F.; Bierne, N.; Arnaud-Haond, S. Large-scale Genetic Panmixia in the Blue Shark (Prionace glauca): A Single Worldwide Population, or a Genetic Lag-time Effect of the “Grey Zone” of Differentiation? Evol. Appl. 2018, 11, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlić, M.; Gačić, M.; LaViolette, P.E. The Currents and Circulation of the Adriatic Sea. Oceanol. Acta 1992, 15, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanellas-Reboredo, M.; Alós, J.; Palmer, M.; March, D.; O’Dor, R. Movement Patterns of the European Squid Loligo vulgaris during the Inshore Spawning Season. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 466, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.A.S.; Bowen, B.W. Shallow Population Histories in Deep Evolutionary Lineages of Marine Fishes: Insights from Sardines and Anchovies and Lessons for Conservation. J. Hered. 1998, 89, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.-C.; Kuo, D.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Ho, K.-C.; Lin, T.-P.; Hwang, S.-Y. Historical Spatial Range Expansion and a Very Recent Bottleneck of Cinnamomum kanehirae Hay. (Lauraceae) in Taiwan Inferred from Nuclear Genes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Losada, M.; Nolte, M.J.; Crandall, K.A.; Shaw, P.W. Testing Hypotheses of Population Structuring in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea Using the Common Cuttlefish Sepia officinalis. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 2667–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, E.; Atar, H.H. DNA Barcoding Commercially Important Aquatic Invertebrates of Turkey. Mitochondrial DNA 2013, 24, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, D.; Tatulli, G.; Montalbetti, E.; Tommasi, N.; Galli, P.; Labra, M.; Pompa, P.P.; Galimberti, A. From DNA Barcoding to Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Testing: A New Frontier in Cephalopod Authentication. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldon, B.; Riquet, F.; Yearsley, J.; Jollivet, D.; Broquet, T. Current Hypotheses to Explain Genetic Chaos under the Sea. Curr. Zool. 2016, 62, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.A.; Loveday, B.R. The Role of Cryptic Dispersal in Shaping Connectivity Patterns of Marine Populations in a Changing World. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2018, 98, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matić-Skoko, S.; Šegvić-Bubić, T.; Mandić, I.; Izquierdo-Gomez, D.; Arneri, E.; Carbonara, P.; Grati, F.; Ikica, Z.; Kolitari, J.; Milone, N.; et al. Evidence of Subtle Genetic Structure in the Sympatric Species Mullus barbatus and Mullus surmuletus (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.W.; Pierce, G.J.; Boyle, P. Subtle Population Structuring within a Highly Vagile Marine Invertebrate, the Veined Squid Loligo forbesi, Demonstrated with Microsatellite DNA Markers. Mol. Ecol. 1999, 8, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerin, E.; Barnwall, L.; Abad, E.; Larivain, A.; Oesterwind, D.; Petroni, M.; Perales-Raya, C.; Robin, J.-P.; Sobrino, I.; Valeiras, J.; et al. Multi-Method Approach Shows Stock Structure in Loligo forbesii Squid. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 79, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Gold, M.; Rodriguez, N.; Barber, P.H. Genome-Wide SNPs Reveal Complex Fine Scale Population Structure in the California Market Squid Fishery (Doryteuthis opalescens). Conserv. Genet. 2021, 22, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Hendrickson, L.; McKeown, N.; Stonier, T.; Naud, M.; Sauer, W. Discrete Spawning Aggregations of Loliginid Squid Do Not Represent Genetically Distinct Populations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 408, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, C.M.; Argüelles, J.; Yamashiro, C.; Adasme, L.; Céspedes, R.; Poulin, E. Spatial Genetic Structure and Demographic Inference of the Patagonian Squid Doryteuthis gahi in the South-Eastern Pacific Ocean. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2012, 92, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M.; Imai, H.; Naruse, T.; Ikeda, Y. Low Genetic Diversity of Oval Squid, Sepioteuthis cf. lessoniana (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae), in Japanese Waters Inferred from a Mitochondrial DNA Non-Coding Region. Pac. Sci. 2008, 62, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, A.; Ramilo-Fernández, G.; Sotelo, C.G. A Real-Time PCR Method for the Authentication of Common Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) in Food Products. Foods 2020, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.E. Phylogeny and Historical Biogeography of the Loliginid Squids (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) Based on Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2000, 15, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, K.; Knebelsberger, T. Identification of Cephalopod Species from the North and Baltic Seas Using Morphology, COI and 18S rDNA Sequences. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2015, 69, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, J.; Costa, P.M.; Teixeira, M.A.; Ferreira, M.S.; Costa, M.H.; Costa, F.O. Enhanced Primers for Amplification of DNA Barcodes from a Broad Range of Marine Metazoans. BMC Ecol. 2013, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laptikhovsky, V.; Cooke, G.; Barrett, C.; Lozach, S.; MacLeod, E.; Oesterwind, D.; Sheerin, E.; Petroni, M.; Barnwall, L.; Robin, J.-P.; et al. Identification of Benthic Egg Masses and Spawning Grounds in Commercial Squid in the English Channel and Celtic Sea: Loligo vulgaris vs L. forbesii. Fish. Res. 2021, 241, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, J.B.D.L.; Rodrigues-Filho, L.F.D.S.; Ferreira, Y.D.S.; Carneiro, J.; Asp, N.E.; Shaw, P.W.; Haimovici, M.; Markaida, U.; Ready, J.; Schneider, H.; et al. Divergence of Cryptic Species of Doryteuthis plei Blainville, 1823 (Loliginidae, Cephalopoda) in the Western Atlantic Ocean Is Associated with the Formation of the Caribbean Sea. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017, 106, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).