Abstract

Understanding the feeding mechanisms and interspecific coexistence of sharks is crucial for effective conservation. This study conducted stable isotope analysis on muscle and liver samples from 449 individuals of eight common bycatch shark species collected via bottom trawling in the northern South China Sea (NSCS). Results revealed significant differences in δ13C and δ15N values among species and tissue types. Scoliodon laticaudus exhibited the highest trophic position (TPmuscle = 4.60 ± 0.33; TPliver = 4.53 ± 0.29), while Apristurus platyrhynchus had the lowest (TPmuscle = 2.97 ± 0.44; TPliver = 2.75 ± 0.53). Muscle and liver isotopic signals were consistent, but δ13C differences indicated distinct carbon sources, with Carcharhinus sorrah linked to deep-sea organic matter and S. laticaudus to coastal inputs. Significant correlations between δ13C/δ15N and body length in A. platyrhynchus and Cephaloscyllium fasciatum suggest ontogenetic shifts in diet and habitat toward deeper waters. Trophic niche analysis using corrected standard ellipse area (SEAc) showed Halaelurus burgeri with the widest trophic niche (SEAc > 1.7‰2), reflecting a broad diet, while C. fasciatum had the narrowest (SEAc < 0.3‰2), indicating specialized feeding. Additionally, H. burgeri and C. sarawakensis exhibited significant niche differentiation, reducing interspecific competition, whereas C. fasciatum and Squalus megalops showed high niche overlap, suggesting intense resource competition. The narrower liver niche of C. sarawakensis may reflect recent habitat constriction due to bottom trawling. This study elucidates the feeding ecology and habitat resource utilization of NSCS sharks, providing a scientific basis for effective conservation strategies for shark populations in the region.

Keywords:

stable isotopes; bycatch shark species; multi-tissue; feeding ecology; niche differentiation; northern South China Sea Key Contribution:

This study provides the first comparative analysis of the feeding ecology of small-size sharks from the coastal South China Sea using multi-tissue stable isotopes. The results reveal relatively minor interspecific variations and stable feeding patterns, while niche differentiation among species plays a crucial role in mitigating trophic competition.

1. Introduction

Stable isotope analysis is one of the most widely used methods to characterize the trophic ecology of organisms [1,2,3] and has been extensively used to study the feeding ecology of marine species. The stable isotope ratios of organisms represent an integrated outcome of growth metabolism, feeding preferences, and protein composition [2,4]. Among these, diet acts as the exogenous pathway supplying stable isotopes and is the main factor affecting carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) values [5]. δ13C is commonly used to trace food sources [6,7], while δ15N indicates trophic position (TP) along the food web [8]. During photosynthesis, primary producers preferentially utilize 12C while enriching 13C. This isotopic discrimination leads to higher δ13C in regions with elevated productivity [9]. In addition, δ13C is influenced by factors such as the size, species, and fractionation rate of primary producers. As these values are transferred along food chains, they are ultimately reflected in predators [10,11]. Complementarily, during trophic transfers, δ15N values typically increase by 2–4‰ per trophic level due to isotopic fractionation, where consumers preferentially excrete lighter 14N, leading to enriched 15N in their tissues [12,13]. This stepwise enrichment makes δ15N a robust marker for determining an organism’s position in the food chain, with higher δ15N values corresponding to higher trophic levels, such as predators [13,14]. Additionally, δ15N reflects variations in nitrogen sources at the base of the food web, influenced by processes like nitrogen fixation, denitrification, or anthropogenic inputs, which also introduce spatial and temporal variability in baseline δ15N values [15]. As these baseline signatures propagate through the food web, δ13C and δ15N in consumers provide critical insights into both their trophic ecology and the biogeochemical processes shaping their habitat.

Trophic niches constructed from isotope ratios represent an important dimension of niche theory and are widely used to examine trophic relationships among species [16]. After stable isotopes enter organisms through the food web, their isotope fractionation effects and turnover rates show significant differences in different tissues due to differences in metabolic activities [16,17]. Metabolically active tissues, such as liver and plasma, respond rapidly to dietary shifts, whereas tissues with lower metabolic rates, such as muscle, blood cells, or vertebral cartilage, integrate feeding information over longer time scales. Previous studies in feeding ecology have mostly focused on muscle tissues to infer diet and habitat shifts, but they have also demonstrated that isotopic turnover varies considerably among tissues, leading to temporal differences in dietary information [4]. Because sharks are typical K-selected species with slow growth and long lifespans, their muscle tissues may be less sensitive to short-term dietary changes [18]. In contrast, liver tissues capture dietary signals on the scale of weeks to months, providing important insights into short-term trophic dynamics. Thus, multi-tissue isotope analysis offers a valuable approach to obtain feeding information across multiple temporal dimensions [19,20].

Sharks belong to the class Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii, comprising 9 orders, 34 families, and about 536 species worldwide [21]. Chinese waters are one of the richest areas for marine shark species, with a total of 21 families and 146 species recorded [22]. Due to their slow growth, late maturity, and low fecundity, sharks are highly vulnerable to overfishing and have increasingly become a focus of conservation biology [23,24]. As apex or near-apex predators, they exert strong top-down control on food web structure and prey populations [25], playing a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem stability and biodiversity [26]. However, research on coastal shark species in China remains limited and has primarily focused on reproductive biology [27,28,29], while studies on trophic ecology, feeding mechanisms, and the temporal dynamics of interspecific interactions are comparatively scarce. In the NSCS, particularly in the Beibu Gulf and adjacent coastal areas, bottom trawl fisheries target a wide range of demersal and small pelagic fishes, which also constitute important prey for coastal sharks. The major trawl-caught fish species include Decapterus maruadsi, Trachurus japonicus, Trichiurus lepturus, Nemipterus virgatus, and Evynnis cardinalis, which together account for a substantial proportion of total catches (e.g., E. cardinalis contributes over 20% of the total catch) and have exhibited declining body sizes due to overfishing [30]. The distribution of these species largely overlaps with the foraging grounds of sharks, providing them with abundant prey resources such as small teleosts and cephalopods [31]. Previous surveys have also indicated that species such as Carcharhinus sorrah and Scoliodon laticaudus are frequently bycaught in trawl fisheries, for example, off New South Wales, and are increasingly at risk of overexploitation [32,33]. These findings underscore the importance of integrating ecological and trophic-level data to better understand shark population dynamics and to provide a scientific basis for future conservation and management strategies for shark species in the region.

This study targets eight typical bycatch shark species inhabiting the northern South China Sea (NSCS). Through the measurement of nitrogen and carbon stable isotopes in both muscle and liver tissues, we seek to explore their feeding characteristics and the mechanisms underlying trophic niche differentiation. This research advances our understanding of the life history processes of coastal sharks and establishes a theoretical foundation for conservation biology and evidence-based resource management in the NSCS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Processing

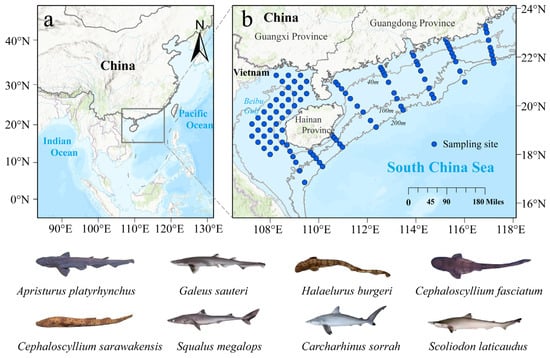

The samples for this study were obtained from a bottom trawl fishery resource survey conducted in the NSCS between 2019 and 2021 (Figure 1). This study selected the eight most typical shark species in the survey area as research subjects, including Borneo catshark (Apristurus platyrhynchus), Blacktip sawtail catshark (Galeus sauteri), Blackspotted catshark (Halaelurus burgeri), Reticulated swellshark (Cephaloscyllium fasciatum), Sarawak pygmy swell shark (Cephaloscyllium sarawakensis), Shortnose spurdog (Squalus megalops), Spot-tail shark (Carcharhinus sorrah), and Spadenose shark (Scoliodon laticaudus). The distribution of each shark species is shown in Figure S1. Additionally, C. sorrah samples were considered supplemental and were collected in June 2019 by the “Nanfeng” fisheries research vessel during a bottom trawl survey off the mouth of the Beibu Gulf. Total length was measured upon return to the laboratory. Basic biological information is provided in Table 1. Muscle samples from all sharks were taken from the muscle below the first dorsal fin, and liver samples were taken from the anterior part of any lobe, then immediately frozen and preserved for later laboratory analysis.

Figure 1.

Bottom trawl survey stations in northern South China Sea (a). Regional context of the study area within the northwestern Pacific (b). Survey station in northern South China Sea.

Table 1.

Total length and stable isotope values of the main bycatch shark species sampled in the China South Sea (rang and mean).

2.2. Stable Isotope Analysis

The muscle samples were first repeatedly rinsed with deionized water to remove urea. Since lipids undergo δ13C fractionation during synthesis, causing differences in δ13C values between lipids and other components, lipid extraction was subsequently performed on the muscle and liver samples [34]. For lipid extraction, 1–3 mg of the sample was weighed into a 15 mL centrifuge tube, 12 mL of dichloromethane-methanol solution (2/1, v/v) (Macklin, Shanghai, China) was added, and after standing for 20 h, the mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The remaining sediment was dried at 60 °C in an oven to remove residual organic solvent. The dichloromethane–methanol system is widely used and has been validated in numerous stable isotope studies of fish tissues. It is worth noting that Kim and Koch [35] suggested petroleum ether as a gentler alternative for elasmobranch muscle tissues, as it may cause less alteration to biochemical composition. However, to maintain methodological consistency across all samples and facilitate comparison, the dichloromethane–methanol mixture was used in this study.

After drying, muscle and liver samples were ground into powder using a ball mill (Dingrui, Guangzhou, China). Approximately 1.0 mg of each sample was weighed using an analytical balance, wrapped in tin foil, and sent to the Stable Isotope Laboratory of Shanghai Ocean University. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios were measured using a stable isotope mass spectrometer (IsoPrime 100, Isoprimer Ltd., Cheadle, UK) and an elemental analyzer (vario ISOTOPE cube, Langenselbold, Germany), with the results expressed as δ values. The calculation formulas for δ13C and δ15N values are as follows:

where X represents 13C or 15N; Rsample and Rstandard represent the isotope ratios 13C/12C or 15N/14N, respectively. The international standard for δ13C is the American Peedee Belemnite (vPDB) produced by the Vienna International Atomic Energy Agency, and the international standard for δ15N is atmospheric N2. Every 15 samples, three laboratory standards (protein: δ13C = −26.98‰, δ15N = 5.96‰) were inserted to calibrate the isotope data. The analysis precision for δ13C and δ15N was 0.05‰ and 0.06‰, respectively.

δX = [(Rsample/Rstandard) − 1] × 1000‰,

2.3. Trophic Position

The trophic position (TP) was estimated using the 15N discrimination value Δ15N between trophic levels, as shown in the following formula:

where δ15Nbase and TPbase are the δ15N value and TP of the baseline organisms in the ecosystem, respectively. When δ15Nbase is the producer, λ = 1; when δ15Nbase is the primary consumer, λ = 2. In this study, the baseline organism was the zooplankton (δ15N = 6.26‰) in the China’s offshore waters [36]. Although species-specific trophic discrimination factors for elasmobranch soft tissues are available [37], we elected to use Δδ15N = 3.4‰ because this value has been widely adopted across aquatic consumer studies [38], and enable consistent comparisons across shark species in our dataset.

TP = (δ15Nshark − δ15Nbase)/Δδ15N + TPbase

2.4. Trophic Niche Estimation

Stable isotope ratios reflect feeding during the synthesis of biological tissue and represent the accumulation of long-term trophic processes in the organism, providing an effective tool for quantifying ecological niches. The standard ellipse area (SEA) provides an estimation of the bivariate (δ13C and δ15N) niche width, covering the distribution within the 40% confidence interval of δ13C and δ15N data, which represents the core niche of a species [39]. This typically requires a sample size of more than 30 individuals. For species with small sample sizes, the corrected standard ellipse area (SEAc) can be used to measure the trophic niche, with a minimum sample size of 3, and it can provide suitable correction for all samples. Therefore, in this study, the SIAR package in R (version 4.1.0) was used to create trophic niche plots for the stable isotope ratios of two tissues from eight shark species, and only used SEAc to calculate the trophic niche width and overlap percentage [40].

2.5. Data Analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to test for significant differences in δ13C and δ15N values among species. Paired tests (paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test, depending on data normality) were applied to compare δ13C and δ15N values between muscle and liver tissues within the same species. Linear regression analysis was conducted to explore whether the difference in δ13C and δ15N values between muscle and liver was significantly related to total length (TL). All statistical analyses and plotting were performed using Origin 2023, SPSS 22.0, and R 4.1.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Multi-Tissue Stable Isotope Analysis

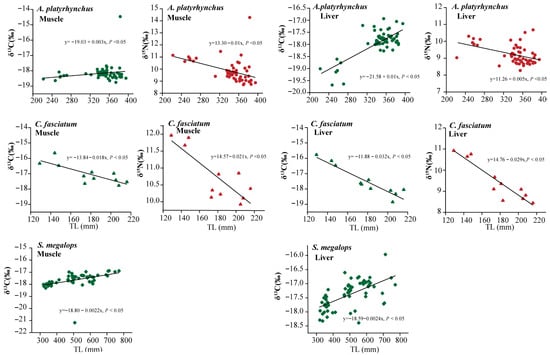

Table 1 lists the δ13C and δ15N values of muscle and liver tissues from 449 individuals of eight shark species primarily caught as bycatch in the NSCS. Among species, significant differences in carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios were observed in all shark muscle and liver tissues (p < 0.05). C. sorrah had lower δ13C values in both tissues, while S. laticaudus had higher δ13C values. No significant differences in δ13C were observed in the other shark species. The δ15N values also showed relative consistency between the two tissues (Table 1), with the highest δ15N values in S. laticaudus and the lowest in A. platyrhynchus. Within species, only δ13C and δ15N values for A. platyrhynchus and C. fasciatum, as well as δ13C values for S. megalops, showed significant linear correlations with TL (p < 0.05), while no linear relationships were found in other species (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relationships between δ13C and δ15N values and total length in muscle and liver tissues of A. platyrhynchus, C. fasciatum, and S. megalops from the northern South China Sea.

3.2. Trophic Position Comparison

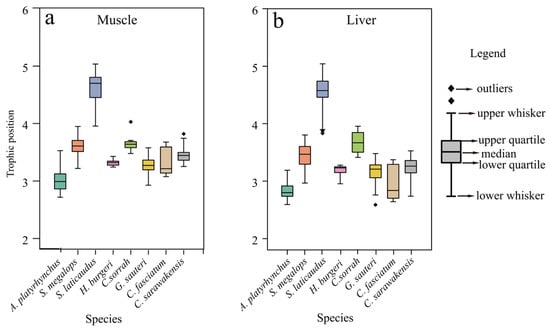

The TP results of the main bycatch shark species in the NSCS are shown in Figure 3. No significant differences in TP values were found between muscle and liver tissues within the same shark species (p > 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Among them, S. laticaudus had the highest TP (TPmuscle = 4.60 ± 0.33; TPliver = 4.53 ± 0.29), and A. platyrhynchus had the lowest TP (TPmuscle = 2.97 ± 0.44; TPliver = 2.75 ± 0.53). The TP of C. fasciatum showed a difference between tissues (TPmuscle = 3.32 ± 0.22; TPliver = 2.94 ± 0.27, p < 0.05), while the TP of the other five shark species ranged between 3 and 4. No significant difference was found between the muscle and liver calculation results (p > 0.05). In addition, one-way ANOVA indicated significant differences in TP values of both muscle and liver among different shark species (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Trophic position in muscle (a) and liver (b) of dominant bycatch shark species in the northern South China Sea.

3.3. Trophic Niche Analysis

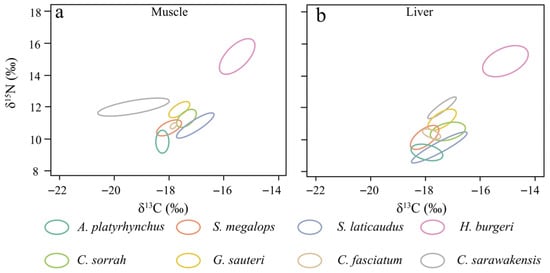

In the stable isotope–based ecological niche analysis of muscle and liver tissues, H. burgeri exhibited the widest trophic niche width (muscle, SEAc = 1.76‰2; liver, SEAc = 2.32‰2), whereas C. fasciatum showed the narrowest (muscle, SEAc = 0.06‰2; liver, SEAc = 0.26‰2). The trophic niche widths of H. burgeri in muscle and liver tissues were 1.7‰2 and 2.96‰2 greater, respectively, than those of C. fasciatum. Notably, C. sarawakensis displayed a broader trophic niche in muscle tissue (SEAc = 1.77‰2) but a narrower one in liver tissue, while S. laticaudus showed the opposite pattern, with a smaller niche width in muscle (SEAc = 0.57‰2) and a larger one in liver (SEAc = 0.98‰2). The remaining four shark species exhibited comparable trophic niche widths between muscle and liver tissues (Table 2).

Table 2.

Corrected standard ellipse area and isotopic niche overlap values for muscle and liver of major bycaught shark species in the northern South China Sea. Note: Niche overlap values are presented to two decimal places. Values < 0.005 are shown as 0.00. Overlap ratios are expressed as percentages (overlap × 100%).

In this study, isotopic niche overlap values < 0.30, 0.30–0.60, and >0.60 were interpreted as slight, moderate, and high overlap, respectively. The isotopic niche of H. burgeri was noticeably separated from the other seven shark species for both muscle and liver tissues. C. fasciatum and S. megalops showed high niche overlap (muscle = 0.95; liver = 0.87), whereas C. sorrah showed slight overlap with G. sauteri and S. laticaudus (muscle < 0.01, liver < 0.01). A. platyrhynchus and S. megalops also exhibited slight overlap (muscle = 0.16; liver = 0.14). In contrast, C. sarawakensis showed clear separation in muscle tissue but slight overlap (0.02) with G. sauteri in liver tissue. Furthermore, A. platyrhynchus and C. sorrah exhibited moderate overlap in both muscle and liver tissues (0.46), indicating partial ecological niche convergence between the two species (Figure 4, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Trophic niche in muscle (a) and liver (b) of the dominant bycatch shark species in the northern South China Sea. The ellipses represent the SEAc of the 40% trophic niche of the eight shark species.

4. Discussion

4.1. δ13C and δ15N Ratios

In the NSCS, most juvenile or subadult shark species exhibit distinct but overlapping ecological patterns shaped by depth preference and trophic habits. A. platyrhynchus generally inhabits continental slope regions at depths of 100–400 m, showing limited horizontal movement and a preference for muddy substrates where benthic crustaceans, polychaetes, and small demersal fishes are abundant [21,41,42]. S. megalops mainly occurs along the outer shelf and upper slope, preying largely on deep-sea shrimps, crabs, small squids, and mesopelagic fishes [43,44]. This species is known to undertake moderate diel vertical migrations, likely following the vertical movements of its prey, and its muscle tissue exhibits a relatively wide carbon source range (4.31‰). In contrast, C. fasciatum primarily inhabits shallow coastal waters during the juvenile stage, feeding on small benthic fishes and crustaceans [41]. Its muscle and liver tissues show lower δ15N values and a narrower δ13C range (2.12–3.08‰). As it matures, it gradually shifts to deeper habitats and preys on larger demersal organisms [45]. This ontogenetic variation in habitat and prey composition is similar to the life history patterns of juvenile or subadult sharks observed in this study. In this study, the δ13C values of A. platyrhynchus, C. fasciatum, and S. megalops were positively correlated with total length, suggesting an ontogenetic shift in their trophic and/or spatial niche. This correlation likely reflects changes in diet (e.g., consumption of prey with different carbon sources) or foraging habitat (e.g., movement to areas with distinct baseline δ13C values) as these sharks grow, influencing their isotopic baselines and feeding ecology. These species are opportunistic feeders, adjusting prey choice based on availability and relying on accessible resources within their habitats.

At the interspecific level, δ13C values of C. sorrah were significantly lower than those of other species, whereas S. laticaudus showed higher δ13C values. The remaining species had similar δ13C values, suggesting comparable carbon sources, distinct from those of C. sorrah and S. laticaudus. C. sorrah mainly inhabits deeper offshore waters, where its carbon sources may be more influenced by deep-sea organic matter. However, as a relatively large and highly mobile pelagic species, C. sorrah may also prey upon organisms from more productive nearshore or mid-water zones, partially explaining its relatively higher δ13C. S. laticaudus, in contrast, typically occurs in shallow nearshore habitats and relies more on carbon inputs from coastal macroalgae and riverine organic matter. This pattern is consistent with findings from studies conducted in surrounding NSCS waters [46,47,48,49,50]. It should be noted that these species were collected from different geographic locations within the NSCS, which likely vary in baseline δ13C values due to spatial heterogeneity in primary production and organic matter sources. Therefore, geographic variation may also contribute to the observed interspecific differences in δ13C, in addition to habitat depth and trophic behavior. Such spatial isotopic gradients are common in coastal and shelf ecosystems [46,51,52]. Other shark species inhabit the mid-water continental shelf, showing general spatial overlap and similar carbon sources. However, interspecific competition may be reduced through niche partitioning at finer scales, such as prey size selection, microhabitat differentiation along the vertical or horizontal axis, temporal segregation of foraging activity, and differences in body size and hunting capabilities. These subtle ecological differences allow co-occurring species to exploit shared food resources without direct competition, resulting in significant dietary differentiation [53,54,55].

The enrichment of δ15N within tissues primarily originates from diet and accumulates across trophic levels, making it a common indicator of trophic position [56,57]. In this study, stable isotope analysis combined with historical stomach content data was employed to elucidate the relationship between trophic level and dietary composition in sharks [51,58]. The study showed a significant correlation between δ15N values and total length in A. platyrhynchus and C. fasciatum (p < 0.01), suggesting that dietary changes may occur throughout individual development. The differing δ13C–TL relationships between muscle and liver in A. platyrhynchus likely reflect tissue-specific turnover rates, with liver responding to short-term dietary shifts while muscle represents longer-term assimilation (Figure 2). In contrast, δ15N–TL patterns remain consistent because δ15N primarily reflects trophic level rather than short-term habitat changes [20]. As individuals grow, both A. platyrhynchus and C. fasciatum tend to migrate to deeper waters, resulting in a shift in their diet from small crustaceans to higher trophic level prey, such as small and medium-sized fish, leading to a gradual enrichment of δ15N [7,41,56]. At the interspecific level, S. laticaudus exhibited the highest δ15N values and a wide trophic span (muscle: 9.80–16.58‰; liver: 11.71–16.59‰), indicating its role as a top predator within the coastal food web of the NSCS. In contrast, A. platyrhynchus showed the lowest δ15N values (muscle: 8.70–14.28‰; liver: 8.27–10.67‰) with a low trophic position and a relatively narrow trophic range (TPmuscle = 2.97; TPliver = 2.75). A stomach content study of S. laticaudus from the Arabian Sea revealed that teleost fishes constituted approximately 72% of its diet, with minor contributions from crustaceans and cephalopods [59]. Similarly, Garima Bora’s research on S. laticaudus in the Indian Ocean demonstrated an ontogenetic dietary shift, where individuals transitioned from feeding primarily on invertebrate-rich diets to piscivory as they grew [60]. In contrast, A. platyrhynchus, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae, primarily feeds on benthic invertebrates, occasionally consuming small benthic fishes and cephalopods. In this study, it exhibited the lowest trophic position, consistent with other scyliorhinid sharks, which generally occupy lower trophic levels compared to other shark species, likely due to their benthic feeding habits [61,62,63]. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that while stable isotope analysis provides valuable insight into the long-term trophic structure, the absence of direct stomach content data limits the precise identification of prey composition and trophic interactions. Future research should integrate stable isotope and stomach content analyses to more comprehensively elucidate shark food-web structures and their ecological roles across trophic hierarchies.

4.2. Isotopic Trophic Niche

The trophic niche width reflects the diversity and evenness of food resources available to organisms [2]. In this study, H. burgeri showed a wide range of trophic niches in both muscle and liver tissues (1.76‰2 and 2.32‰2), indicating that the species feeds on a wide range of prey and exhibits strong ecological adaptability. H. burgeri is widely distributed in the northwest Pacific, with its southern limit extending to areas below 1° north latitude [64]. Field surveys conducted in the southwest shelf of the South China Sea showed that H. burgeri is an omnivorous, broad-feeding animal with a flexible feeding strategy, feeding on invertebrates, cephalopods, and zooplankton [64]. Although a detailed stomach content analysis was not conducted in this study, simple microscopic stomach inspections revealed that a few individuals contained human food residues (e.g., Chinese cabbage and red chili pepper) in their stomachs, suggesting a broad diet breadth and a potential use of human-derived organic inputs. Similar opportunistic feeding behavior has been documented in congeners such as Lamna nasus, whose diet mainly consists of teleosts and cephalopods but also varies seasonally and spatially in response to prey availability [65,66]. These qualitative observations, together with the isotopic evidence, further suggest that the examined species may exhibit opportunistic feeding and maintain a broad trophic niche influenced by both natural prey and human-derived organic inputs. H. burgeri showed significant differences in isotopic composition from the other seven shark species. The observed differences may reflect the unique foraging habitat and baseline isotopic characteristics of H. burgeri. The specimens analyzed in this study were mature individuals with strong foraging capabilities (TL > 40 cm; Table 2), mainly distributed on the continental shelf at sublittoral depths of approximately 80–100 m and occasionally captured by near-bottom longline fisheries (FishBase, https://www.fishbase.se, accessed on 25 August 2025). In these environments, baseline δ13C and δ15N values are generally elevated due to terrestrial organic inputs and anthropogenic nutrient enrichment [15,67]. Consequently, this habitat use may result in isotopic values that differ from those of nearshore or benthic shark species that primarily rely on marine carbon sources. Furthermore, ingestion of anthropogenic food residues or detrital material may further alter their isotopic composition, reinforcing their unique position in isotopic niche space. C. sarawakensis exhibited a larger trophic niche width in muscle (1.77‰2) than in liver (0.44‰2), implying recent habitat changes. The reduction in trophic niche width in the liver may reflect potential short-term habitat stress or a decline in resource diversity, although it does not directly demonstrate population decline. However, such trophic niche contraction may indicate ecosystem changes that pose potential risks to the population stability of C. sarawakensis. This species is widely distributed in nearshore waters at depths of 100–200 m in the NSCS; its habitat strongly overlaps with bottom-trawl fishing grounds, where it is commonly caught as bycatch [33,45]. Based on this potential risk, this study recommends strengthening long-term ecological and population monitoring, integrating environmental and fishery survey data, and reducing anthropogenic disturbances (e.g., bottom trawling and seabed destruction) to provide a scientific basis for future conservation and management efforts.

Niche overlap can be used to reflect the similarity in resource use and potential competitive relationships among species [68]. Species with highly similar niches may reduce intermediate competition by altering feeding habits or differentiating habitats [69,70]. In this study, significant trophic niche segregation was observed between H. burgeri and C. sarawakensis and the other bycatch shark species, indicating a certain degree of dietary isolation and relatively low interspecific competition. In contrast, varying levels of niche overlap were found among other bycatch sharks, suggesting the existence of potential competition. Evidence shows that the degree of trophic niche overlap reflects the similarity of resource utilization and potential competitive pressures among these shark species [71,72]. The observed niche overlap among other bycatch sharks suggests they may share similar food resources, especially when habitat and prey types overlap extensively. Such competitive interactions could profoundly influence population dynamics and resource allocation [73]. However, the significant trophic niche segregation of H. burgeri and C. sarawakensis from other species indicates that they avoid direct competition through differences in feeding habits or habitat use. H. burgeri, with its broad diet and diverse food sources, can exploit alternative prey when food competition arises, while the marked niche segregation of C. sarawakensis enables it to circumvent direct competition with other sharks, contributing to higher resource abundance and wide distribution in this region. Moreover, such niche segregation may also be related to the spatiotemporal variability of environmental conditions and resource availability [74,75]. Seasonal or spatial heterogeneity in food resources in the study area may drive species to partition niches, thereby adapting to environmental changes and alleviating competitive pressure [71]. High niche overlap among species generally indicates similar resource utilization or substantial habitat overlap, which may theoretically lead to resource competition and affect population structure and distribution patterns [74,75,76]. However, in the present study area, long-term fishing pressure may have resulted in a decline in overall shark populations, which could to some extent alleviate the intensity of interspecific competition [32]. Nevertheless, trophic niche overlap still reflects potential resource dependencies and ecological interaction patterns, providing important insights into the coexistence mechanisms of different species in disturbed ecosystems.

Moreover, numerous studies have shown that many coastal shark species exhibit distinct seasonal movement patterns (e.g., Sphyrna lewini, Carcharhinus melanopterus, Negaprion acutidens, Sphyrna zygaena) [77], which can influence their diet and lead to differences in isotopic signals between muscle and liver tissues. For example, Carcharhinus limbatus is known for its coastal–offshore migrations, typically moving to warmer waters in winter to follow prey [78]. These seasonal movements can cause short-term dietary changes, affecting the isotopic composition of liver tissue, which has a relatively fast turnover rate (typically weeks to months), whereas muscle tissue, with a slower turnover rate (months to years), reflects longer-term dietary averages [79]. Similarly, in the central California region, two Scyliorhinidae species (corresponding to A. platyrhynchus, G. sauteri, H. burgeri, C. fasciatum, and C. sarawakensis in this study) exhibited seasonal variations in both stomach contents and stable isotope values, further contributing to isotopic differences between tissues [61]. However, studies on the seasonal movement patterns of the shark species examined in this study are currently limited. Overall, the trophic niche profiles of the main bycatch shark species in this study showed general similarity between the two tissues, indicating minimal interspecific variation and relatively stable feeding habits.

The findings of this study highlight the significance of niche differentiation among shark species. Such differentiation not only effectively reduces interspecific competition but also plays a key role in maintaining ecosystem stability and diversity [80,81]. Future research should further explore several aspects: first, seasonal and spatial variations in the trophic niches of mature shark species should be examined to reveal the dynamic patterns of resource use across the life cycle.; second, investigate the driving effects of environmental factors (e.g., temperature, salinity, and food resource distribution) on niche differentiation, clarifying how environmental changes influence species distribution and niche adaptation [82,83,84,85]; and finally, integrate population dynamics to assess the long–term impacts of niche overlap on interspecific competition and resource allocation, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the role of niche differentiation in population dynamics and ecosystem functioning. To improve the statistical reliability of the inferences and the robustness of ecological interpretations, future studies should further increase sample size and strengthen sampling and monitoring across multiple spatial and temporal scales. These studies will provide a more scientific basis for the conservation and management of shark populations.

5. Conclusions

This study provides new insights into the trophic ecology of eight bycatch shark species in the NSCS through multi-tissue stable isotope analysis of muscle and liver.

δ13C and δ15N values varied significantly among shark species, highlighting differences in their feeding strategies and habitat use. S. laticaudus exhibited the highest TP, while A. platyrhynchus occupied the lowest, reflecting their distinct TP in the food web. H. burgeri exhibited the broadest trophic niche, whereas C. sarawakensis occupied the narrowest, and both showed marked niche separation from other sharks, indicating flexible feeding strategies and reduced interspecific competition. In contrast, C. sarawakensis showed tissue-specific niche shifts, potentially linked to environmental change and fishing pressure. Moreover, stable isotope results between muscle and liver tissues did not differ significantly in shark feeding characteristics; however, interspecific differences in δ13C reflected varied carbon sources, with C. sorrah associated with deep-sea organic matter and S. laticaudus with coastal inputs. Significant correlations between δ15N and total length in A. platyrhynchus and C. fasciatum further suggest ontogenetic shifts in diet and habitat.

Overall, trophic niche partitioning among shark species reduces direct competition and contributes to the stability and diversity of coastal ecosystems. These findings underscore the ecological importance of niche differentiation for sustaining predator coexistence. Future research should integrate seasonal and spatial dynamics, environmental drivers, and population monitoring to better understand how niche overlap influences species interactions and to develop targeted conservation strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10110583/s1, Figure S1. Distribution of sampling stations where target shark species were captured in the northern South China Sea.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z. and Y.X.; methodology, Y.X.; software, K.Z.; validation, K.Z. and Y.X.; formal analysis, K.Z.; investigation, Y.X.; resources, Z.C.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z.; writing—review and editing, P.X. and Y.X.; visualization, P.X.; supervision, Y.X. and Z.C.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, K.Z., Z.C. and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFD2400605), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025A1515011979), the Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund of the South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, CAFS (2025RC01), and the Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund of the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (2023TD05).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute Animal welfare committee (Ethical approval number. SCSFRI document No. 28/2023 and approval date: 17 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the entire crew of the “Zhongyuke 301” and “Nanfeng” fisheries research vessel for their participation in the sampling. We thank Yuyan Gong and Yutao Yang for their collaboration on the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NSCS | Northern South China Sea |

| TP | Trophic Position |

| SEA | Standard Ellipse Area |

| SEAc | the Corrected Standard Ellipse Area |

| TL | Total Length |

References

- Kechang, N.; Yining, L.; Zehao, S.; Fangliang, H.E.; Jingyun, F. Community assembly: The relative importance of neutral theory and niche theory. Biodivers. Sci. 2009, 17, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecklen, W.J.; Yarnes, C.T.; Cook, B.A.; James, A.C. On the use of stable isotopes in trophic ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 42, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, O.N.; Brooks, E.J.; Madigan, D.J.; Sweeting, C.J.; Dean Grubbs, R. Stable isotope analysis in deep-sea chondrichthyans: Recent challenges, ecological insights, and future directions. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2017, 27, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, M.A.; Skomal, G.B.; Fisk, A.T. Stable isotopes from multiple tissues reveal diet switching in sharks. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 302, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñán-Montaño, C.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Sánchez-González, A.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; Delgado-Huertas, A.; Páez-Rosas, D. Dietary ontogeny of the blue shark, Prionace glauca, based on the analysis of δ13C and δ15N in vertebrae. Mar. Biol. 2019, 166, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounick, J.S.; Winterbourn, M.J. Stable carbon isotopes and carbon flow in ecosystems. BioScience 1986, 36, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.J.; Joung, S.J.; Hsu, H.H.; Liu, K.M.; Yamaguchi, A. Stable Isotope Analysis of Two Filter-Feeding Sharks in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. Fishes 2025, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.A.; Piatt, J.F.; Pitocchelli, J. Using stable isotopes to determine seabird trophic relationships. J. Anim. Ecol. 1994, 63, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Ma, M. Stable carbon isotopes in seagrasses: Variability in ratios and use in ecological studies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 140, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzini, S.; Mazzola, A. Seasonal variations in the stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios (13C/12C and 15N/14N) of primary producers and consumers in a western Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Mar. Biol. 2003, 142, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianen, M.J.A.; Middelburg, J.J.; Holthuijsen, S.J.; Jouta, J.; Compton, T.J.; van der Heide, T.; Piersma, T.; Sinninghe Damsté, J.S.; van der Veer, H.W.; Schouten, S. Benthic primary producers are key to sustain the Wadden Sea food web: Stable carbon isotope analysis at landscape scale. Ecology 2017, 98, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; McClelland, J.W.; Mente, E.; Montoya, J.P.; Atkinson, A.; Voss, M. Trophic-level interpretation based on δ15N values: Implications of tissue-specific fractionation and amino acid composition. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 266, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.B.; Shipley, O.N.; Moll, R.J. Meta-analysis and critical review of trophic discrimination factors (Δ13C and Δ15N): Importance of tissue, trophic level and diet source. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 2535–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethybridge, H.; Choy, C.A.; Logan, J.M.; Allain, V.; Lorrain, A.; Bodin, N.; Somes, C.J.; Young, J.; Ménard, F.; Langlais, C. A global meta-analysis of marine predator nitrogen stable isotopes: Relationships between trophic structure and environmental conditions. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, C.; Elliott, E.M.; Wankel, S.D. Tracing anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen to ecosystems. In Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 375–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearhop, S.; Adams, C.E.; Waldron, S.; Fuller, R.A.; Macleod, H. Determining trophic niche width: A novel approach using stable isotope analysis. J. Anim. Ecol. 2004, 73, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, R.H.; Kaufman, L. Stable isotope ratios as tracers in marine food webs: An update. In Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 238–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, D.; Macdonald, C.; Gainsbury, A.; Green, M.L.; Cassill, D.L. Maternal risk-management elucidates the evolution of reproductive adaptations in sharks by means of natural selection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niella, Y.; Raoult, V.; Gaston, T.; Peddemors, V.M.; Harcourt, R.; Smoothey, A.F. Overcoming multi-year impacts of maternal isotope signatures using multi-tracers and fast turnover tissues in juvenile sharks. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 129393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, K.B.; Yurkowski, D.J.; Wintner, S.P.; Cliff, G.; Dicken, M.L.; Hussey, N.E. Determining the appropriate pretreatment procedures and the utility of liver tissue for bulk stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) studies in sharks. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 98, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.A.; Dando, M.; Fowler, S. Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, S. Species, geography distribution and resource of chondrichthian fishes of China. J. Xiamen Univ. Nat. Sci. 2005, 44, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Davidson, L.N.K.; Fordham, S.V.; Bräutigam, A.; Sant, G.; Welch, D.J. Challenges and Priorities in Shark and Ray Conservation. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R565–R572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcher, I.F.; Darvell, B.W. Shark fishing vs. conservation: Analysis and synthesis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, L.G.; Barner, A.K.; Bittleston, L.S.; Teufel, A.I. Quantifying the relative importance of variation in predation and the environment for species coexistence. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A.J.; Shiffman, D.S.; Byrnes, E.E.; Hammerschlag-Peyer, C.M.; Hammerschlag, N. Patterns of resource use and isotopic niche overlap among three species of sharks occurring within a protected subtropical estuary. Aquat. Ecol. 2017, 51, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.K.; Liu, K.M. Reproductive biology of whitespotted bamboo shark Chiloscyllium plagiosum in northern waters off Taiwan. Fish. Sci. 2006, 72, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ju, P.; Xiao, J.; Chen, M. Reproductive biology of the Pacific spadenose shark Scoliodon macrorhynchos, a heavily exploited species in the Southern Taiwan Strait. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2022, 14, e210216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming-ru, C.; Shu-yuan, Q.I.U.; Sheng-yun, Y. The reproductive biology of the Spadenose Shark, Scoliodon laticaudus, from southern Fujian coastal waters. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2001, 23, 92–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Su, L.; Chen, Z.Z.; Qiu, Y.S. An extensive assessment of exploitation indicators for multispecies fisheries in the South China Sea to inform more practical and precise management in China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Azri, A. Diversity, occurrence and conservation of sharks in the southern South China Sea. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ding, L.; Su, S.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Loh, K.-H.; Yang, S.; Chen, M.; Roeroe, K.A.; Songploy, S. Setting conservation priorities for marine sharks in China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) seas: What are the benefits of a 30% conservation target? Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 933291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dai, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, K. Stock Assessment of Four Dominant Shark Bycatch Species in Bottom Trawl Fisheries in the Northern South China Sea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M.; Layman, C.A.; Arrington, D.A.; Takimoto, G.; Quattrochi, J.; Montana, C.G. Getting to the fat of the matter: Models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 2007, 152, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Koch, P.L. Methods to collect, preserve, and prepare elasmobranch tissues for stable isotope analysis. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2012, 95, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Dong, J.Y.; Sun, X.; Zhan, Q.P.; Wang, L.L.; Zhang, X.M. Trophic Structure of Fishery Assemblage in Surrounding Waters of Lingshan Island Based on Stable Isotope Analysis. Period. Ocean Univ. China 2022, 52, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Casper, D.R.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Ochoa-Díaz, R.; Hernández-Aguilar, S.B.; Koch, P.L. Carbon and nitrogen discrimination factors for elasmobranch soft tissues based on a long-term controlled feeding study. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2012, 95, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 2002, 83, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, C.A.; Arrington, D.A.; Montaa, C.G.; Post, D.M. Can stable isotope ratios provide for community-wide measures of trophic structure? Ecology 2007, 88, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.L.; Inger, R.; Parnell, A.C.; Bearhop, S. Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER–Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011, 80, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagno, L.J.V. FAO Species Catalogue Vol. 4. Sharks of the World. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Part 2. Carcharhiniformes; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1984; pp. 251–655. [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya, K.; Sato, K. Taxonomic review of Apristurus platyrhynchus and related species from the Pacific Ocean (Chondrichthyes, Carcharhiniformes, Scyliorhinidae). Ichthyol. Res. 2000, 47, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, T.; Ohshimo, S.; Sakai, T.; Yoda, M. Filling gaps in the biology and habitat use of two spurdog sharks (Squalus japonicus and Squalus brevirostris) in the East China Sea. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2020, 71, 1719–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, J.M.; Gillanders, B.M.; Walker, T.I. Sources of variation in the feeding ecology of the piked spurdog (Squalus megalops): Implications for inferring predator–prey interactions from overall dietary composition. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2005, 62, 1076–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, K.; Kawauchi, J. A review of the genus Apristurus (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhiniformes: Scyliorhinidae) from Taiwanese waters. Zootaxa 2013, 3752, 130–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, A.; Li, X.; Xu, Q. δ13C and δ15N stable isotopes demonstrate seasonal changes in the food web of coral reefs at the Wuzhizhou Island of the South China sea. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenbo, Z.; Honghui, H.; Chunhou, L.I.; Yong, L.I.U.; Zhanhui, Q.I.; Shannan, X.U.; Huaxue, L.I.U. Study on carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes of main fishery species in typical gulf, southern China. South China Fish. Sci. 2019, 15, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanru, Z.; Qingxia, L.; Honghui, H.; Xiaoqing, Q.; Jiajun, L.; Jianhua, C. Study on stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen of main fishery organisms in the southwestern waters of Daya Bay, South China Sea in winter 2020. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2022, 41, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Kang, Z.; Song, X.; Liu, Y. Food web structure and trophic diversity for the fishes of four islands in the Pearl River Estuary, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingyu, Q.; Qingxia, L.; Zuozhi, C.; Yancong, C.; Shouhui, D.; Honghui, H. The trophic structure of main fishery organisms in the southwestern continental shelf of the Nansha Islands in spring. J. Fish. Sci. China 2024, 31, 1524–1538. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Rosado, M.A.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Torres-Rojas, Y.E.; Delgado-Huertas, A.; Aguiñiga-García, S. Use of δ15N and δ13C in reconstructing the ontogenetic feeding habits of silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis): Reassessing their trophic role in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2023, 106, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherel, Y.; Hobson, K.A. Geographical variation in carbon stable isotope signatures of marine predators: A tool to investigate their foraging areas in the Southern Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 329, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, D. Age, growth, reproduction and feeding of the spurdog (Squalus acanthias Linnaeus, 1758) in the South-eastern Black Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2001, 52, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia, A.F.; Mejía-Falla, P.A.; Giraldo, A. Feeding ecology of elasmobranch fishes in coastal waters of the Colombian Eastern Tropical Pacific. BMC Ecol. 2007, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.C.; Then, A.Y.-H.; Loh, K.-H. Feeding ecology and reproductive biology of small coastal sharks in Malaysian waters. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Dai, X.; Zhu, J. Trophic ecology of sharks in the mid-east Pacific ocean inferred from stable isotopes. J. Ocean Univ. China 2014, 13, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderklift, M.A.; Ponsard, S. Sources of variation in consumer-diet δ15N enrichment: A meta-analysis. Oecologia 2003, 136, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiffman, D.S.; Frazier, B.S.; Kucklick, J.R.; Abel, D.; Brandes, J.; Sancho, G. Feeding Ecology of the Sandbar Shark in South Carolina Estuaries Revealed through δ13C and δ15N Stable Isotope Analysis. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2014, 6, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Purushottama, G.B.; Nataraja, G.D.; Kizhakudan, S.J. Fishery and biological characteristics of the spadenose shark Scoliodon laticaudus Müller & Henle, 1838 from the Eastern Arabian Sea. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 34, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, G.; Dsouza, S.; Shanker, K. Diet composition and variation in four commonly landed and threatened shark species in Maharashtra, India. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 74, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, M. Evaluating the Trophic Habits and Dietary Overlap of Two Deep-Sea Catsharks (Apristurus brunneus and Parmaturus xaniurus) in Central California, USA. 2021. Available online: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/1116 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Laptikhovsky, V.V.; Arkhipkin, A.I.; Henderson, A.C. Feeding habits and dietary overlap in spiny dogfish Squalus acanthias (Squalidae) and narrowmouth catshark Schroederichthys bivius (Scyliorhinidae). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2001, 81, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; Zapata-Hernández, G.; Bustamante, C.; Sellanes, J.; Meléndez, R. Trophic ecology of the dusky catshark Bythaelurus canescens (Günther, 1878)(Chondrychthyes: Scyliorhinidae) in the southeast Pacific Ocean. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2013, 29, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagno, L.J.V. Hemigaleidae. Halaelurus burgeri. In Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes; The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Volume 2. Cephalopods, Crustaceans, Holothurians and Sharks; Carpenter, K.E., Niem, V.H., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; pp. 1305–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Belleggia, M.; Colonello, J.; Cortés, F.; Figueroa, D.E. Eating catch of the day: The diet of porbeagle shark Lamna nasus (Bonnaterre 1788) based on stomach content analysis, and the interaction with trawl fisheries in the south-western Atlantic (52° S–56° S). J. Fish Biol. 2021, 99, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.N.; Campana, S.E.; Natanson, L.J.; Kohler, N.E.; Pratt, H.L., Jr.; Jensen, C.F. Analysis of stomach contents of the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus Bonnaterre) in the northwest Atlantic. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2002, 59, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edje, B.O.; Ishaque, A.B.; Chigbu, P. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of δ13C and δ15N of Suspended Particulate Organic Matter in Maryland Coastal Bays, USA. Water 2020, 12, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.I.; Barabás, G.; Bimler, M.D.; Mayfield, M.M.; Miller, T.E. The evolution of niche overlap and competitive differences. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelage, L.; Lucena-Frédou, F.; Eduardo, L.N.; Le Loc’h, F.; Bertrand, A.; Lira, A.S.; Frédou, T. Competing with each other: Fish isotopic niche in two resource availability contexts. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 975091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurs, G.; Nieuwenhuis, B.O.; Zuidewind, T.J.; Hijner, N.; Olff, H.; Govers, L.L. Where land meets sea: Intertidal areas as key-habitats for sharks and rays. Fish Fish. 2023, 24, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weideli, O.C.; Daly, R.; Peel, L.R.; Heithaus, M.R.; Shivji, M.S.; Planes, S.; Papastamatiou, Y.P. Elucidating the role of competition in driving spatial and trophic niche patterns in sympatric juvenile sharks. Oecologia 2023, 201, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priester, C.R.; Dierking, J.; Hansen, T.; Abecasis, D.; Fontes, J.M.; Afonso, P. Trophic ecology and coastal niche partitioning of two sympatric shark species in the Azores (mid-Atlantic). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2024, 726, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Echevarría, L.M.; Tamburin, E.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; Marmolejo-Rodríguez, A.J.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Tripp-Valdez, A.; Lara, A.; Jonathan, M.P.; Sujitha, S.B.; Delgado-Huertas, A.; et al. How to stay together? Habitat use by three sympatric sharks in the western coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 61685–61697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.D.; Jenkins, A.; Perry, S.L.; Perkins, S.E.; Cable, J. Temporal niche partitioning as a potential mechanism for coexistence in two sympatric mesopredator sharks. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1443357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimley, A.P.; Ketchum, J.T.; Lara-Lizardi, F.; Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Hoyos-Padilla, E.M. Evidence for spatial and temporal resource partitioning of sharks at Roca Partida, an isolated pinnacle in the eastern Pacific. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2022, 105, 1963–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, P.; Jensen, C.C.; Matich, P.; Rooker, J.R.; Wells, R.J.D. Predicting habitat suitability for the co-occurrence of an estuarine mesopredator and two top predatory fishes. Front. Fish Sci. 2024, 2, 1443923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, C.W.; Field, I.C.; Meekan, M.G.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Complexities of coastal shark movements and their implications for management. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 408, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiura, S.M.; Tellman, S.L. Quantification of massive seasonal aggregations of blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus) in Southeast Florida. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curnick, D.J.; Carlisle, A.B.; Gollock, M.J.; Schallert, R.J.; Hussey, N.E. Evidence for dynamic resource partitioning between two sympatric reef shark species within the British Indian Ocean Territory. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaudo, J.J.; Heithaus, M.R. Dietary niche overlap in a nearshore elasmobranch mesopredator community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 425, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F.; Worm, B.; Britten, G.L.; Heithaus, M.R.; Lotze, H.K. Patterns and ecosystem consequences of shark declines in the ocean. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.M.; Arthur, R.H.M. Niche Overlap as a Function of Environmental Variability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1972, 69, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengal, K.; Zhang, X. Intraspecific variations in climatic niche of sharks and their relatives: Patterns, drivers, and molecular mechanisms. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, R.G.; Campbell, H.A.; Cramp, R.L.; Burke, C.L.; Micheli-Campbell, M.A.; Pillans, R.D.; Lyon, B.J.; Franklin, C.E. Niche partitioning between river shark species is driven by seasonal fluctuations in environmental salinity. Funct. Ecol. 2020, 34, 2170–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broennimann, O.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Pearman, P.B.; Petitpierre, B.; Pellissier, L.; Yoccoz, N.G.; Thuiller, W.; Fortin, M.J.; Randin, C.; Zimmermann, N.E. Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).